#I used to write in the little caption/image description sections to talk about them all individually but at some point tumblr broke that

Text

Baby boy brother birthday photos from last year that I just realized I never uploaded!

#cats#also hopefully it's not weird to still post photos of George (the brown cat) even after his death a little while ago. I just have so many#beautiful old pictures of him that I still love but just never had the time to sort through or upload (my cat photos folder on my#computer had like 450 pictures in it or something lol... SO many). I feel like it's kind of just honoring or appreciating him#and not actually strange or anything. like what am I supposed to do. delete them?? I want to share them still because he is beautiful and#perfect ! idk. aNYWAY. Also this is their 2022 birthday when they turned 14 years old. (even though I think when I posted#their 2021 bday I might have said they were 14 then too. I was off by a year lol). 2023 when they turned 15 I unfortunately#was feeling kind of sick at the time and didn't really have the energy to do the decorations like I usually do. So they just got a few#treats and stuff. But I didn't know that would be george's last birthday lol. :/#They also do not really know or care though. they're cats who cannot process it or know the concept of birthdays so. eh#I still have no idea how these got lost on the computer though. Like I had them fully edited ready to post but just sitting in a folder??#Since MARCH 2022 lol... ??? the folder was in another folder of pictures so maybe that's how I overlooked it#But it's my 'once every 4 months computer organizing and clean out time' so I was going tghrough looking for pictures#I could drafts posts out of or sort or etc.#They got lots more treats for this birthday because one of my friends actually game me a few gifts for them#elderly boys.!!!!#I used to write in the little caption/image description sections to talk about them all individually but at some point tumblr broke that#feature and for so long they never saved or weren't visible so I stopped doing them and just ramble a bunch in the tags instead#but I kind of miss them. Thinking about old posts of the cats where I commented on each photo individually too lol.. the good ole days

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remember Longcat, Jane? I remember Longcat. Fuck the picture on this page, I want to talk about Longcat. Memes were simpler back then, in 2006. They stood for something. And that something was nothing. Memes just were. “Longcat is long.” An undeniably true, self-reflexive statement. Water is wet, fire is hot, Longcat is long. Memes were floating signifiers without signifieds, meaningful in their meaninglessness. Nobody made memes, they just arose through spontaneous generation; Athena being birthed, fully formed, from her own skull.

You could talk about them around the proverbial water cooler, taking comfort in their absurdity. “Hey, Johnston, have you seen the picture of that cat? They call it Longcat because it’s long!” “Ha ha, sounds like good fun, Stevenson! That reminds me, I need to show you this webpage I found the other day; it contains numerous animated dancing hamsters. It’s called — you’ll never believe this — hamsterdance!” And then Johnston and Stevenson went on to have a wonderful friendship based on the comfortable banality of self-evident digitized animals.

But then 2007 came, and along with it came I Can Has, and everything was forever ruined. It was hubris, Jane. We did it to ourselves. The minute we added written language beyond the reflexive, it all went to shit. Suddenly memes had an excess of information to be parsed. It wasn’t just a picture of a cat, perhaps with a simple description appended to it; now the cat spoke to us via a written caption on the picture itself. It referred to an item of food that existed in our world but not in the world of the meme, rupturing the boundary between the two. The cat wanted something. Which forced us to recognize that what it wanted was us, was our attention. WE are the cheezburger, Jane, and we always were. But by the time we realized this, it was too late. We were slaves to the very memes that we had created. We toiled to earn the privilege of being distracted by them. They fiddled while Rome burned, and we threw ourselves into the fire so that we might listen to the music. The memes had us. Or, rather, they could has us.

And it just got worse from there. Soon the cats had invisible bicycles and played keyboards. They gained complex identities, and so we hollowed out our own identities to accommodate them. We prayed to return to the simple days when we would admire a cat for its exceptional length alone, the days when the cat itself was the meme and not merely a vehicle for the complex memetic text. And the fact that this text was so sparse, informal, and broken ironically made it even more demanding. The intentional grammatical and syntactical flaws drew attention to themselves, making the meme even more about the captioning words and less about the pictures. Words, words, words. Wurds werds wordz. Stumbling through a crooked, dead-end hallway of a mangled clause describing a simple feline sentiment was a torture that we inflicted on ourselves daily. Let’s not forget where the word “caption” itself comes from: capio, Latin for both “I understand” and “I capture.” We thought that by captioning the memes, we were understanding them. Instead, our captions allowed them to capture us. The memes that had once been a cure for our cultural ills were now the illness itself.

It goes right back to the Phaedrus, really. Think about it. Back in the innocent days of 2006, we naïvely thought that the grapheme had subjugated the phoneme, that the belief in the primacy of the spoken word was an ancient and backwards folly on par with burning witches or practicing phrenology or thinking that Smash Mouth was good. Fucking Smash Mouth. But we were wrong. About the phoneme, I mean. Theuth came to us again, this time in the guise of a grinning grey cat. The cat hungered, and so did Theuth. He offered us an updated choice, and we greedily took it, oblivious to the consequences. To borrow the parlance of a contemporary meme, he baked us a pharmakon, and we eated it.

Pharmakon, φάρμακον, the Greek word that means both “poison” and “cure,” but, because of the

limitations of the English language, can only be translated one way or the other depending on the context and the translator’s whims. No possible translation can capture the full implications of a Greek text including this word. In the Phaedrus, writing is the pharmakon that the trickster god Theuth offers, the toxin and remedy in one. With writing, man will no longer forget; but he will also no longer think. A double-edged (s)word, if you will. But the new iteration of the pharmakon is the meme. Specifically, the post-I-Can-Has memescape of 2007 onward. And it was the language that did it, Jane. The addition of written language twisted the remedy into a poison, flipped the pharmakon on its invisible axis.

In retrospect, it was in front of our eyes all along. Meme. The noxious word was given to us by who else but those wily ancient Greeks themselves. μίμημα, or mīmēma. Defined as an imitation, a copy. The exact thing Plato warned us against in the Republic. Remember? The simulacrum that is two steps removed from the perfection of the original by the process of — note the root of the word — mimesis. The Platonic ideal of an object is the source: the father, the sun, the ghostly whole. The corporeal manifestation of the object is one step removed from perfection. The image of the object (be it in letters or in pigments) is two steps removed. The author is inferior to the craftsman is inferior to God.

Fuck, out of space. Okay, the illustration on page 46 is fucking useless; I’ll see you there.

(21)

But we’ll go farther than Plato. Longcat, a photograph, is a textbook example of a second-degree mimesis. (We might promote it to the third degree since the image on the internet is a digital copy of the original photograph of the physical cat which is itself a copy of Platonic ideal of a cat (the Godcat, if you will); but this line of thought doesn’t change anything in the argument.) The text-supplemented meme, on the other hand, the captioned cat, is at an infinite remove from the Godcat, the ultimate mimesis, copying the copy of itself eternally, the written language and the image echoing off each other, until it finally loops back around to the truth by virtue of being so far from it. It becomes its own truth, the fidelity of the eternal copy. It becomes a God.

Writing itself is the archetypical pharmakon and the archetypical copy, if you’ll come back with me to the Phaedrus (if we ever really left it). Speech is the real deal, Socrates says, with a smug little wink to his (written) dialogic buddy. Speech is alive, it can defend itself, it can adapt and change. Writing is its bastard son, the mimic, the dead, rigid simulacrum. Writing is a copy, a mīmēma, of truth in speech. To return to our analogous issue: the image of the cheezburger cat, the copy of the picture-copy-copy, is so much closer to the original Platonic ideal than the written language that accompanies it. (“Pharmakon” can also mean “paint.” Think about it, Jane. Just think about it.) The image is still fake, but it’s the caption on the cat that is the downfall of the republic, the real fakeness, which is both realer and faker than whatever original it is that it represents. Men and gods abhor the lie, Plato says in sections 382 a and b of the Republic.

οὐκ οἶσθα, ἦν δ᾽ ἐγώ, ὅτι τό γε ὡς ἀληθῶς ψεῦδος, εἰ οἷόν τε τοῦτο εἰπεῖν, πάντες θεοί τε καὶ ἄνθρωποι μισοῦσιν;

πῶς, ἔφη, λέγεις;

οὕτως, ἦν δ᾽ ἐγώ, ὅτι τῷ κυριωτάτῳ που ἑαυτῶν ψεύδεσθαι καὶ περὶ τὰ κυριώτατα οὐδεὶς ἑκὼν ἐθέλει, ἀλλὰ πάντων μάλιστα φοβεῖται ἐκεῖ αὐτὸ κεκτῆσθαι.

“Don’t you know,” said I, “that the veritable lie, if the expression is permissible, is a thing that all gods and men abhor?”

“What do you mean?” he said.

“This,” said I, “that falsehood in the most vital part of themselves, and about their most vital concerns, is something that no one willingly accepts, but it is there above all that everyone fears it.”

Man’s worst fear is that he will hold existential falsehood within himself. And the verbal lies that he tells are a copy of this feared dishonesty in the soul.

Plato goes on to elaborate: “the falsehood in words is a copy of the affection in the soul, an after-rising image of it and not an altogether unmixed falsehood.” A copy of man’s false internal copy of truth. And what word does Plato use for “copy” in this sentence? That’s fucking right, μίμημα. Mīmēma. Mimesis. Meme. The new meme is a lie, manifested in (written) words, that reflects the lack of truth, the emptiness, within the very soul of a human. The meme is now not only an inferior copy, it is a deceptive copy.

But just wait, it gets better. Plato continues in the very next section of the Republic, 382 c. Sometimes, he says, the lie, the meme, is appropriate, even moral. It is not abhorrent to lie to your enemy, or to your friend in order to keep him from harm. “Does it [the lie] not then become useful to avert the evil—as a medicine?” You get one fucking guess for what Greek word is being translated as “medicine” in this passage. Ding ding motherfucking ding, you got it, φάρμακον, pharmakon. The μίμημα is a φάρμακον, the lie is a medicine/poison, the meme is a pharmakon.

But I’m sure that by now you’ve realized the (intentional) mistake in my argument that brought us to this point. I said earlier that the addition of written language to the meme flipped the pharmakon on its axis. But the pharmakon didn’t flip, it doesn’t have an axis. It was always both remedy and poison. The fact that this isn’t obvious to us from the very beginning of the discussion is the fault of, you guessed it, language. The initial lie (writing) clouds our vision and keeps us from realizing how false the second-order lie (the meme) is.

The very structure of the lying meme mirrors the structure of the written word that defines and corrupts it. Once you try to identify an “outside” in order to reveal the lie, the whole framework turns itself inside-out so that you can never escape it. The cat wants the cheezburger that exists outside the meme, but only through the meme do we become aware of the presumed existence of the cheezburger — we can’t point out the absurdity of the world of the meme without also indicting our own world. We can’t talk about language without language, we can’t meme without mimesis. Memes didn’t change between ‘06 and ‘07, it was us who changed. Or rather, our understanding of what we had always been changed. The lie became truth, the remedy became the poison, the outside became the inside. Which is to say that the truth became lie, the pharmakon was always the remedy and the poison, and the inside retreated further inside. It all came full circle. Because here’s the secret, Jane. Language ruined the meme, yes. But language itself had already been ruined. By that initial poisonous, lying copy. Writing.

The First Meme.

Language didn’t attack the meme in 2007 out of spite. It attacked it to get revenge.

Longcat is long. Language is language. Pharmakon is pharmakon. The phoneme topples the grapheme, witches ride through the night, our skulls hide secret messages on their surfaces, Smash Mouth is good after all. Hey now, you’re an all-star. Get your game on.

Go play.

262 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remember Longcat, Jane? I remember Longcat. Fuck the picture on this page, I want to talk about Longcat. Memes were simpler back then, in 2006. They stood for something. And that something was nothing. Memes just were. “Longcat is long.” An undeniably true, self-reflexive statement. Water is wet, fire is hot, Longcat is long. Memes were floating signifiers without signifieds, meaningful in their meaninglessness. Nobody made memes, they just arose through spontaneous generation; Athena being birthed, fully formed, from her own skull.

You could talk about them around the proverbial water cooler, taking comfort in their absurdity. “Hey, Johnston, have you seen the picture of that cat? They call it Longcat because it’s long!” “Ha ha, sounds like good fun, Stevenson! That reminds me, I need to show you this webpage I found the other day; it contains numerous animated dancing hamsters. It’s called — you’ll never believe this — hamsterdance!” And then Johnston and Stevenson went on to have a wonderful friendship based on the comfortable banality of self-evident digitized animals.

But then 2007 came, and along with it came I Can Has, and everything was forever ruined. It was hubris, Jane. We did it to ourselves. The minute we added written language beyond the reflexive, it all went to shit. Suddenly memes had an excess of information to be parsed. It wasn’t just a picture of a cat, perhaps with a simple description appended to it; now the cat spoke to us via a written caption on the picture itself. It referred to an item of food that existed in our world but not in the world of the meme, rupturing the boundary between the two. The cat wanted something. Which forced us to recognize that what it wanted was us, was our attention. WE are the cheezburger, Jane, and we always were. But by the time we realized this, it was too late. We were slaves to the very memes that we had created. We toiled to earn the privilege of being distracted by them. They fiddled while Rome burned, and we threw ourselves into the fire so that we might listen to the music. The memes had us. Or, rather, they could has us.

And it just got worse from there. Soon the cats had invisible bicycles and played keyboards. They gained complex identities, and so we hollowed out our own identities to accommodate them. We prayed to return to the simple days when we would admire a cat for its exceptional length alone, the days when the cat itself was the meme and not merely a vehicle for the complex memetic text. And the fact that this text was so sparse, informal, and broken ironically made it even more demanding. The intentional grammatical and syntactical flaws drew attention to themselves, making the meme even more about the captioning words and less about the pictures. Words, words, words. Wurds werds wordz. Stumbling through a crooked, dead-end hallway of a mangled clause describing a simple feline sentiment was a torture that we inflicted on ourselves daily. Let’s not forget where the word “caption” itself comes from: capio, Latin for both “I understand” and “I capture.” We thought that by captioning the memes, we were understanding them. Instead, our captions allowed them to capture us. The memes that had once been a cure for our cultural ills were now the illness itself.

It goes right back to the Phaedrus, really. Think about it. Back in the innocent days of 2006, we naïvely thought that the grapheme had subjugated the phoneme, that the belief in the primacy of the spoken word was an ancient and backwards folly on par with burning witches or practicing phrenology or thinking that Smash Mouth was good. Fucking Smash Mouth. But we were wrong. About the phoneme, I mean. Theuth came to us again, this time in the guise of a grinning grey cat. The cat hungered, and so did Theuth. He offered us an updated choice, and we greedily took it, oblivious to the consequences. To borrow the parlance of a contemporary meme, he baked us a pharmakon, and we eated it.

Pharmakon, φάρμακον, the Greek word that means both “poison” and “cure,” but, because of the limitations of the English language, can only be translated one way or the other depending on the context and the translator’s whims. No possible translation can capture the full implications of a Greek text including this word. In the Phaedrus, writing is the pharmakon that the trickster god Theuth offers, the toxin and remedy in one. With writing, man will no longer forget; but he will also no longer think. A double-edged (s)word, if you will. But the new iteration of the pharmakon is the meme. Specifically, the post-I-Can-Has memescape of 2007 onward. And it was the language that did it, Jane. The addition of written language twisted the remedy into a poison, flipped the pharmakon on its invisible axis.

In retrospect, it was in front of our eyes all along. Meme. The noxious word was given to us by who else but those wily ancient Greeks themselves. μίμημα, or mīmēma. Defined as an imitation, a copy. The exact thing Plato warned us against in the Republic. Remember? The simulacrum that is two steps removed from the perfection of the original by the process of — note the root of the word — mimesis. The Platonic ideal of an object is the source: the father, the sun, the ghostly whole. The corporeal manifestation of the object is one step removed from perfection. The image of the object (be it in letters or in pigments) is two steps removed. The author is inferior to the craftsman is inferior to God.

Fuck, out of space. Okay, the illustration on page 46 is fucking useless; I’ll see you there.

But we’ll go farther than Plato. Longcat, a photograph, is a textbook example of a second-degree mimesis. (We might promote it to the third degree since the image on the internet is a digital copy of the original photograph of the physical cat which is itself a copy of Platonic ideal of a cat (the Godcat, if you will); but this line of thought doesn’t change anything in the argument.) The text-supplemented meme, on the other hand, the captioned cat, is at an infinite remove from the Godcat, the ultimate mimesis, copying the copy of itself eternally, the written language and the image echoing off each other, until it finally loops back around to the truth by virtue of being so far from it. It becomes its own truth, the fidelity of the eternal copy. It becomes a God.

Writing itself is the archetypical pharmakon and the archetypical copy, if you’ll come back with me to the Phaedrus (if we ever really left it). Speech is the real deal, Socrates says, with a smug little wink to his (written) dialogic buddy. Speech is alive, it can defend itself, it can adapt and change. Writing is its bastard son, the mimic, the dead, rigid simulacrum. Writing is a copy, a mīmēma, of truth in speech. To return to our analogous issue: the image of the cheezburger cat, the copy of the picture-copy-copy, is so much closer to the original Platonic ideal than the written language that accompanies it. (“Pharmakon” can also mean “paint.” Think about it, Jane. Just think about it.) The image is still fake, but it’s the caption on the cat that is the downfall of the republic, the real fakeness, which is both realer and faker than whatever original it is that it represents. Men and gods abhor the lie, Plato says in sections 382 a and b of the Republic.

οὐκ οἶσθα, ἦν δ᾽ ἐγώ, ὅτι τό γε ὡς ἀληθῶς ψεῦδος, εἰ οἷόν τε τοῦτο εἰπεῖν, πάντες θεοί τε καὶ ἄνθρωποι μισοῦσιν;

πῶς, ἔφη, λέγεις;

οὕτως, ἦν δ᾽ ἐγώ, ὅτι τῷ κυριωτάτῳ που ἑαυτῶν ψεύδεσθαι καὶ περὶ τὰ κυριώτατα οὐδεὶς ἑκὼν ἐθέλει, ἀλλὰ πάντων μάλιστα φοβεῖται ἐκεῖ αὐτὸ κεκτῆσθαι.

“Don’t you know,” said I, “that the veritable lie, if the expression is permissible, is a thing that all gods and men abhor?”

“What do you mean?” he said.

“This,” said I, “that falsehood in the most vital part of themselves, and about their most vital concerns, is something that no one willingly accepts, but it is there above all that everyone fears it.”

Man’s worst fear is that he will hold existential falsehood within himself. And the verbal lies that he tells are a copy of this feared dishonesty in the soul. Plato goes on to elaborate: “the falsehood in words is a copy of the affection in the soul, an after-rising image of it and not an altogether unmixed falsehood.” A copy of man’s false internal copy of truth. And what word does Plato use for “copy” in this sentence? That’s fucking right, μίμημα. Mīmēma. Mimesis. Meme. The new meme is a lie, manifested in (written) words, that reflects the lack of truth, the emptiness, within the very soul of a human. The meme is now not only an inferior copy, it is a deceptive copy.

But just wait, it gets better. Plato continues in the very next section of the Republic, 382 c. Sometimes, he says, the lie, the meme, is appropriate, even moral. It is not abhorrent to lie to your enemy, or to your friend in order to keep him from harm. “Does it [the lie] not then become useful to avert the evil—as a medicine?” You get one fucking guess for what Greek word is being translated as “medicine” in this passage. Ding ding motherfucking ding, you got it, φάρμακον, pharmakon. The μίμημα is a φάρμακον, the lie is a medicine/poison, the meme is a pharmakon.

But I’m sure that by now you’ve realized the (intentional) mistake in my argument that brought us to this point. I said earlier that the addition of written language to the meme flipped the pharmakon on its axis. But the pharmakon didn’t flip, it doesn’t have an axis. It was always both remedy and poison. The fact that this isn’t obvious to us from the very beginning of the discussion is the fault of, you guessed it, language. The initial lie (writing) clouds our vision and keeps us from realizing how false the second-order lie (the meme) is.

The very structure of the lying meme mirrors the structure of the written word that defines and corrupts it. Once you try to identify an “outside” in order to reveal the lie, the whole framework turns itself inside-out so that you can never escape it. The cat wants the cheezburger that exists outside the meme, but only through the meme do we become aware of the presumed existence of the cheezburger — we can’t point out the absurdity of the world of the meme without also indicting our own world. We can’t talk about language without language, we can’t meme without mimesis. Memes didn’t change between ‘06 and ‘07, it was us who changed. Or rather, our understanding of what we had always been changed. The lie became truth, the remedy became the poison, the outside became the inside. Which is to say that the truth became lie, the pharmakon was always the remedy and the poison, and the inside retreated further inside. It all came full circle. Because here’s the secret, Jane. Language ruined the meme, yes. But language itself had already been ruined. By that initial poisonous, lying copy. Writing.

The First Meme.

Language didn’t attack the meme in 2007 out of spite. It attacked it to get revenge.

Longcat is long. Language is language. Pharmakon is pharmakon. The phoneme topples the grapheme, witches ride through the night, our skulls hide secret messages on their surfaces, Smash Mouth is good after all. Hey now, you’re an all-star. Get your game on.

Go play.

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

So you have to know Rosemary isn't coming back. Not in Pesterquest, not in Candy, not in Meat. It's done. It's over. You let yourself get queerbaited because you're a moron.

Remember Longcat, Jane? I remember Longcat. Fuck the picture on this page, I want to talk about Longcat. Memes were simpler back then, in 2006. They stood for something. And that something was nothing. Memes just were. “Longcat is long.” An undeniably true, self-reflexive statement. Water is wet, fire is hot, Longcat is long. Memes were floating signifiers without signifieds, meaningful in their meaninglessness. Nobody made memes, they just arose through spontaneous generation; Athena being birthed, fully formed, from her own skull.

You could talk about them around the proverbial water cooler, taking comfort in their absurdity. “Hey, Johnston, have you seen the picture of that cat? They call it Longcat because it’s long!” “Ha ha, sounds like good fun, Stevenson! That reminds me, I need to show you this webpage I found the other day; it contains numerous animated dancing hamsters. It’s called — you’ll never believe this — hamsterdance!” And then Johnston and Stevenson went on to have a wonderful friendship based on the comfortable banality of self-evident digitized animals.

But then 2007 came, and along with it came I Can Has, and everything was forever ruined. It was hubris, Jane. We did it to ourselves. The minute we added written language, it all went to shit. Suddenly memes had an excess of information to be parsed. It wasn’t just a picture of a cat, perhaps with a simple description appended to it; now the cat spoke to us via a written caption on the picture itself. It referred to an item of food that existed in our world but not in the world of the meme, rupturing the boundary between the two. The cat wanted something. Which forced us to recognize that what it wanted was us, was our attention. WE are the cheezburger, Jane, and we always were. But by the time we realized this, it was too late. We were slaves to the very memes that we had created. We toiled to earn the privilege of being distracted by them. They fiddled while Rome burned, and we threw ourselves into the fire so that we might listen to the music. The memes had us. Or, rather, they could has us.

And it just got worse from there. Soon the cats had invisible bicycles and played keyboards. They gained complex identities, and so we hollowed out our own identities to accommodate them. We prayed to return to the simple days when we would admire a cat for its exceptional length alone, the days when the cat itself was the meme and not merely a vehicle for the complex memetic text. And the fact that this text was so sparse, informal, and broken ironically made it even more demanding. The intentional grammatical and syntactical flaws drew attention to themselves, making the meme even more about the captioning words and less about the pictures. Words, words, words. Wurds werds wordz. Stumbling through a crooked, dead-end hallway of a mangled clause describing a simple feline sentiment was a torture that we inflicted on ourselves daily. Let’s not forget where the word “caption” itself comes from: capio, Latin for both “I understand” and “I capture.” We thought that by captioning the memes, we were understanding them. Instead, our captions allowed them to capture us. The memes that had once been a cure for our cultural ills were now the illness itself.

It goes right back to Phaedrus, really. The Plato dialogue. (You read that, right?) Back in the innocent days of 2006, we naïvely thought that the grapheme had subjugated the phoneme, that the belief in the primacy of the spoken word was an ancient and backwards folly on par with burning witches or practicing phrenology or thinking that Smash Mouth was good. Fucking Smash Mouth. But we were wrong. About the phoneme, I mean. The trickster god Theuth came to us again, this time in the guise of a grinning grey cat. The cat hungered, and so did Theuth. We’d already taken writing from him, so this time he offered us a new choice disguised as a gift. And we greedily took it, again oblivious to the consequences. To borrow the parlance of a contemporary meme, he made us a pharmakon, and we eated it.

Pharmakon, φάρμακον, the Greek word that means both “poison” and “cure,” but, because of the limitations of the English language, can only be translated one way or the other depending on the context and the translator’s whims. No possible translation can capture the full implications of a Greek text including this word. In the Phaedrus, writing is the pharmakon that the trickster god Theuth offers, the toxin and remedy in one. With writing, man will no longer forget; but he will also no longer think. A double-edged (s)word, if you will. But the new iteration of the pharmakon is the meme. Specifically, the post-I-Can-Has memescape of 2007 onward. And it was the language that did it, Jane. The addition of written language twisted the remedy into a poison, flipped the pharmakon on its invisible axis.

In retrospect, it was in front of our eyes all along. Meme. The noxious word was given to us by who else but those wily ancient Greeks themselves. μίμημα, or mīmēma. Defined as an imitation, a copy. The exact thing Plato warned us against in the Republic. Remember? The simulacrum that is two steps removed from the perfection of the original by the process of — note the root of the word — mimesis. The Platonic ideal of an object is the source: the father, the sun, the ghostly whole. The corporeal manifestation of the object is one step removed from perfection. The image of the object (be it in letters or in pigments) is two steps removed. The author is inferior to the craftsman is inferior to God.

But we’ll go farther than Plato. Longcat, a photograph, is a textbook example of a second-degree mimesis. (We might promote it to the third degree since the image on the internet is a digital copy of the original photograph of the physical cat which is itself a copy of Platonic ideal of a cat (the Godcat, if you will); but this line of thought doesn’t change anything in the argument.) The text-supplemented meme, on the other hand, the captioned cat, is at an infinite remove from the Godcat; it is the ultimate mimesis, copying the copy of itself eternally, the written language and the image echoing off each other, until it finally loops back around to the truth by virtue of being so far from it. It becomes its own truth, the fidelity of the eternal copy. It becomes a God.

Writing itself is the archetypical pharmakon and the archetypical copy, if you’ll come back with me to the Phaedrus (if we ever really left it). Speech is the real deal, Socrates says, with a smug little wink to his (written) dialogic buddy. Speech is alive, it can defend itself, it can adapt and change. Writing is its bastard son, the mimic, the dead, rigid simulacrum. Writing is a copy, a mīmēma, of truth in speech. To return to our analogous issue: the image of the cat that wants the cheezburger, the copy of the picture-copy-copy, is so much closer to its original Platonic ideal (Godcat) than the written language that accompanies it is to its own (speech). (“Pharmakon” can also mean “paint.” Think about it, Jane. Just think about it.) The image is still fake, but it’s the caption on the cat that is the downfall of the republic, the real fakeness, which is both realer and faker than whatever original it is that it represents.

Men and gods abhor the lie, Plato says in sections 382 a and b of the Republic.

#long post#i didn't read this message i just wanted you to remember longcat :)#rosemary hate anon#that one guy

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

What she says: I'm fine

What she means: Remember Longcat, Jane? I remember Longcat. Fuck the picture on this page, I want to talk about Longcat. Memes were simpler back then, in 2006. They stood for something. And that something was nothing. Memes just were. “Longcat is long.” An undeniably true, self-reflexive statement. Water is wet, fire is hot, Longcat is long. Memes were floating signifiers without signifieds, meaningful in their meaninglessness. Nobody made memes, they just arose through spontaneous generation; Athena being birthed, fully formed, from her own skull.

You could talk about them around the proverbial water cooler, taking comfort in their absurdity. “Hey, Johnston, have you seen the picture of that cat? They call it Longcat because it’s long!” “Ha ha, sounds like good fun, Stevenson! That reminds me, I need to show you this webpage I found the other day; it contains numerous animated dancing hamsters. It’s called — you’ll never believe this — hamsterdance!” And then Johnston and Stevenson went on to have a wonderful friendship based on the comfortable banality of self-evident digitized animals.

But then 2007 came, and along with it came I Can Has, and everything was forever ruined. It was hubris, Jane. We did it to ourselves. The minute we added written language, it all went to shit. Suddenly memes had an excess of information to be parsed. It wasn’t just a picture of a cat, perhaps with a simple description appended to it; now the cat spoke to us via a written caption on the picture itself. It referred to an item of food that existed in our world but not in the world of the meme, rupturing the boundary between the two. The cat wanted something. Which forced us to recognize that what it wanted was us, was our attention. WE are the cheezburger, Jane, and we always were. But by the time we realized this, it was too late. We were slaves to the very memes that we had created. We toiled to earn the privilege of being distracted by them. They fiddled while Rome burned, and we threw ourselves into the fire so that we might listen to the music. The memes had us. Or, rather, they could has us.

And it just got worse from there. Soon the cats had invisible bicycles and played keyboards. They gained complex identities, and so we hollowed out our own identities to accommodate them. We prayed to return to the simple days when we would admire a cat for its exceptional length alone, the days when the cat itself was the meme and not merely a vehicle for the complex memetic text. And the fact that this text was so sparse, informal, and broken ironically made it even more demanding. The intentional grammatical and syntactical flaws drew attention to themselves, making the meme even more about the captioning words and less about the pictures. Words, words, words. Wurds werds wordz. Stumbling through a crooked, dead-end hallway of a mangled clause describing a simple feline sentiment was a torture that we inflicted on ourselves daily. Let’s not forget where the word “caption” itself comes from: capio, Latin for both “I understand” and “I capture.” We thought that by captioning the memes, we were understanding them. Instead, our captions allowed them to capture us. The memes that had once been a cure for our cultural ills were now the illness itself.

It goes right back to Phaedrus, really. The Plato dialogue. (You read that, right?) Back in the innocent days of 2006, we naïvely thought that the grapheme had subjugated the phoneme, that the belief in the primacy of the spoken word was an ancient and backwards folly on par with burning witches or practicing phrenology or thinking that Smash Mouth was good. Fucking Smash Mouth. But we were wrong. About the phoneme, I mean. The trickster god Theuth came to us again, this time in the guise of a grinning grey cat. The cat hungered, and so did Theuth. We’d already taken writing from him, so this time he offered us a new choice disguised as a gift. And we greedily took it, again oblivious to the consequences. To borrow the parlance of a contemporary meme, he made us a pharmakon, and we eated it.

Pharmakon, φάρμακον, the Greek word that means both “poison” and “cure,” but, because of the limitations of the English language, can only be translated one way or the other depending on the context and the translator’s whims. No possible translation can capture the full implications of a Greek text including this word. In the Phaedrus, writing is the pharmakon that the trickster god Theuth offers, the toxin and remedy in one. With writing, man will no longer forget; but he will also no longer think. A double-edged (s)word, if you will. But the new iteration of the pharmakon is the meme. Specifically, the post-I-Can-Has memescape of 2007 onward. And it was the language that did it, Jane. The addition of written language twisted the remedy into a poison, flipped the pharmakon on its invisible axis.

In retrospect, it was in front of our eyes all along. Meme. The noxious word was given to us by who else but those wily ancient Greeks themselves. μίμημα, or mīmēma. Defined as an imitation, a copy. The exact thing Plato warned us against in the Republic. Remember? The simulacrum that is two steps removed from the perfection of the original by the process of — note the root of the word — mimesis. The Platonic ideal of an object is the source: the father, the sun, the ghostly whole. The corporeal manifestation of the object is one step removed from perfection. The image of the object (be it in letters or in pigments) is two steps removed. The author is inferior to the craftsman is inferior to God.

But we’ll go farther than Plato. Longcat, a photograph, is a textbook example of a second-degree mimesis. (We might promote it to the third degree since the image on the internet is a digital copy of the original photograph of the physical cat which is itself a copy of Platonic ideal of a cat (the Godcat, if you will); but this line of thought doesn’t change anything in the argument.) The text-supplemented meme, on the other hand, the captioned cat, is at an infinite remove from the Godcat; it is the ultimate mimesis, copying the copy of itself eternally, the written language and the image echoing off each other, until it finally loops back around to the truth by virtue of being so far from it. It becomes its own truth, the fidelity of the eternal copy. It becomes a God.

Writing itself is the archetypical pharmakon and the archetypical copy, if you’ll come back with me to the Phaedrus (if we ever really left it). Speech is the real deal, Socrates says, with a smug little wink to his (written) dialogic buddy. Speech is alive, it can defend itself, it can adapt and change. Writing is its bastard son, the mimic, the dead, rigid simulacrum. Writing is a copy, a mīmēma, of truth in speech. To return to our analogous issue: the image of the cat that wants the cheezburger, the copy of the picture-copy-copy, is so much closer to its original Platonic ideal (Godcat) than the written language that accompanies it is to its own (speech). (“Pharmakon” can also mean “paint.” Think about it, Jane. Just think about it.) The image is still fake, but it’s the caption on the cat that is the downfall of the republic, the real fakeness, which is both realer and faker than whatever original it is that it represents.

Men and gods abhor the lie, Plato says in sections 382 a and b of the Republic.

οὐκ οἶσθα, ἦν δ᾽ ἐγώ, ὅτι τό γε ὡς ἀληθῶς ψεῦδος, εἰ οἷόν τε τοῦτο εἰπεῖν, πάντες θεοί τε καὶ ἄνθρωποι μισοῦσιν; πῶς, ἔφη, λέγεις; οὕτως, ἦν δ᾽ ἐγώ, ὅτι τῷ κυριωτάτῳ που ἑαυτῶν ψεύδεσθαι καὶ περὶ τὰ κυριώτατα οὐδεὶς ἑκὼν ἐθέλει, ἀλλὰ πάντων μάλιστα φοβεῖται ἐκεῖ αὐτὸ κεκτῆσθαι.

“Don't you know,” said I, “that the veritable lie, if the expression is permissible, is a thing that all gods and men abhor?” “What do you mean?” he said. “This,” said I, “that falsehood in the most vital part of themselves, and about their most vital concerns, is something that no one willingly accepts, but it is there above all that everyone fears it.” Man’s worst fear is that he will hold existential falsehood within himself. And the verbal lies that he tells are an incarnation of this fear; Plato elaborates: “the falsehood in words is a copy of the affection in the soul, an after-rising image of it and not an altogether unmixed falsehood.” A copy of man’s flawed internal copy of truth. And what word does Plato use for “copy” in this sentence? That’s fucking right, μίμημα. Mīmēma. Mimesis. Meme. The new meme is a lie, manifested in (written) words, that reflects the lack of truth, the emptiness, within the very soul of a human. The meme is now not only an inferior copy, it is a deceptive copy.

But just wait, it gets better. Plato continues in the very next section of the Republic, 382 c. Sometimes, he says, the lie, the meme, is appropriate, even moral. It is not abhorrent to lie to your enemy, or to your friend in order to keep him from harm. “Does it [the lie] not then become useful to avert the evil—as a medicine?” You get one fucking guess for what Greek word is being translated as “medicine” here. Ding ding goddamn ding, you got it, φάρμακον, pharmakon. The μίμημα is a φάρμακον, the lie is a medicine/poison, the meme is a pharmakon.

But I’m sure that by now you’ve realized the (intentional) mistake in my argument that brought us to this point. I said earlier that the addition of written language to the meme flipped the pharmakon on its axis. But the pharmakon didn’t flip, it doesn’t have an axis. It was always both remedy and poison. The fact that this isn’t obvious to us from the very beginning of the discussion is the fault of, you guessed it, language. The initial lie (writing) clouds our vision and keeps us from realizing how false the second-order lie (the meme) is.

The very structure of the lying meme mirrors the structure of the written word that defines and corrupts it. Once you try to identify an “outside” in order to reveal the lie, the whole framework turns itself inside-out so that you can never escape it. The cat wants the cheezburger that exists outside the meme, but only through the meme do we become aware of the presumed existence of the cheezburger — we can’t point out the absurdity of the world of the meme without also indicting our own world. We can’t talk about language without language, we can’t interpret memes without mimesis. Memes didn’t change between ’06 and ’07, it was us who changed. Or rather, our understanding of what we had always been changed. The lie became truth, the remedy became the poison, the outside became the inside. Which is to say that the truth became lie, the pharmakon was always the remedy and the poison, and the inside retreated further inside. It all came full circle. Because here’s the secret, Jane. Language ruined the meme, yes. But language itself had already been ruined. By that initial poisonous, lying copy. Writing. The First Pharmakon. The First Meme.

Language didn’t attack the meme in 2007 out of spite. It attacked it to get revenge.

Longcat is long. Language is language. Pharmakon is pharmakon. The phoneme topples the grapheme, witches ride through the night, our skulls hide secret messages on their surfaces, Smash Mouth is good after all. Hey now, you’re an all-star. Get your game on.

Go play.

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

This week I had the opportunity to visit Fishbourne Roman Palace, and was very excited to see how they portray a Roman site to the public and engage their visitors. I went with my grandma, who I remember a few years ago saying to me “I don’t like museums”, although she seems to enjoy them much more now when we go together, especially if there’s something pretty to see and take photos of. We had an amazing experience there and I’ve picked out a few of the things that stood out to me to talk about; the museum area, the walk across the mosaics and the gardens. I will be writing about the “hands on” area in my next article, and following this I’ll be summing up my thoughts about how they have portrayed their site and how -theoretically- we could portray Malton Roman Fort (where my department have been excavating) to visitors if it were to be an attraction and museum in a similar way.

A picture of me standing in front of banners showing different types of artefacts

Content warning: images of and discussion of human skeletons

(And yes, I’m wearing a Pokemon T-shirt in the featured image, I had to stick an awkward photo of me in here somewhere)

My grandma looking at a model of a Roman bathhouse

History of the Site

Fishbourne Palace, located in West Sussex, is the largest surviving Roman building in Britain and dates to about 75AD. Most of the palace was excavated in 1960 by Sir Barry Cunliffe after it was accidentally discovered by a water company laying a new line over the site. The palace is so big that a museum has been built over the site to try and preserve as much of the building in situ as possible.

In size, it is approximately equivalent to Nero’s Golden palace in Rome and in plan it closely mirrors the emperor Domitian’s palace (the Domus Flavia) completed in AD 92 on the Palatine Hill in Rome. Fishbourne is by far the largest Roman residence known north of the Alps. At about 150 square metres, it has a larger footprint than Buckingham Palace.

Museum

The museum is the first part you will see on your visit, it is laid out with information on walls in a numbered sequence which gives a background to the Roman occupation of England and the context of the site. These exhibits are very text heavy, and are balanced by the display of artefacts and images & diagrams.

Panel 1 was about the discovery of the site

Panel 2 explained stratigraphy and the display demonstrated this.

Panel 3 was about the site

Panel 4 explained the Roman invasion with diagrams

As well as these more factual exhibits there are interactive activities such as building a Roman road and identifying gods by matching pictures together on a low table. The scale model of the site in the first room attracted my Grandma, allowing for a more tactile experience than viewing a local map.

A scale model map of the area. On the glass there is a diagram indicating where the modern road is.

There were also a lot of kids when I went who were all fascinated by the example weaving activity, the scale model map and the bust of Vespasian, shouting “That’s what he looks like!!”. It is so important to have such tangible links for people to be able to relate to people in the past and see even emperors as “human”.

A bust of Vespasian

The curators of the exhibition have clearly put a lot of thought into weaving multiple themes into one, for example the “imported elegance” panel, which displays wall plaster from Fishbourne, explaining how the elaborate finishes would have been done by a skilled craftsman probably from Italy, and displaying two images of wall paintings found in Italy which compare to the evidence from Fishbourne.

Panel 24: Imported elegance. The display shows wall plaster from the site, and shows wall paintings from other sites which are similar.

The final parts of an exhibition are just as important as the introduction and can leave a lasting impact on the audience, and at Fishbourne the final space has three panels, “Disaster”, “Burials”, and “The Jigsaw”.

The disaster panel explains how between 270 and 280 AD the palace was destroyed by a fire, and how it cannot be certain if the fire was accidental or deliberate, but notes that pirates were raiding the south coast at that time, a neat way of painting a picture and explaining a narrative whilst not asserting facts we don’t know, a lot of archaeologists I know would say that if we’re not sure on the facts we shouldn’t tell stories, which are vital to public engagement and understanding.

The accompanying display is a show of the destruction, with puddles of melted lead, buckled window glass and broken and discoloured pottery which has been repaired and reconstructed for the exhibit. Personally my eyes are drawn to the reconstructed pots more than the disarticulated glass. On the top shelf by comparison, there are lots and glass from the late third century that survived the fire, it’s a massive shame that my photographs didn’t survive however.

The human remains in the museum lie in a glass case.

The burials section is in association with the human remains that lie in the centre of the room which is captioned with “a pagan burial, oriented on a north-south line and discovered in the demolished ruins of the Roman Palace”, which is on the opposite side of the room to the rest if the information. This is probably due to issues to do with space, but it did confuse me having the information, remains and the explanation all in different places.

The panel explains how the ruin was salvaged after it burnt down and that people would take things of value before further demolishing the building. They say that later, probably towards the end of the Roman period, shallow burials were made in the rubble, and one grave was in the north wing which was much deeper and is still there now.

Human remains in a grave cut into the floor

The ethics of displaying human remains in museums is contentious, and I won’t go into full details here. I think it is a lovely gesture to have left the skeleton in the north wing in its final resting place. The sign accompanying the burial simply says that there was no dating evidence in the form of grave goods, but we know that the graves were cut after the palace was destroyed. I was left feeling a little bit frustrated about the lack of information about the burials, although I’m aware that specific information is missing from our records as archaeologists, even more general information about human remains and osteology would benefit visitors. All in all I felt like this lack of information translated to a lack of “respect” for these people as individuals, and that they were seen as artefacts only.

Panel 34: The jigsaw

(Sorry for the image with me in the background.. I guess we can say I’m a treasure?)

The final panel is a neat conclusion to the exhibit, displaying modern and medieval artefacts which were found in the excavation such as coins and pottery which got there through ploughing, and captions this with the story of how the site was uncovered by workmen in 1960. Finally the last image of the exhibition is comprised of images of trenches, finds, archaeologists and analysis overlaid with a jigsaw which is a beautiful and emotive image. This choice to focus on archaeology and archaeologists as well as Roman history is masterfully played out, integrating the modern process of excavation neatly with the archaeology itself.

Image with a jigsaw overlay of archaeologists working on different aspects of the Fishbourne excavations

The Mosaics

Cupid on a dolphin mosaic

Walking around the bridges to see the mosaic floor was by far my favourite part. It was amazing to see the beautiful mosaics, each one different, laid out as though in the villa. The open layout of the room gave an immense sense of space and a feeling of awe, which is a key part of engagement at any heritage site. It is also almost entirely flat or ramped sections, making the exhibit one continuous experience.

My grandma looking at the mosaics

Practically, each mosaic is separated and labelled in a numbered sequence, meaning that you can walk around the room in a loop following the trail and and back at the start, although the route is not necessarily fixed. Each information board is located where you can see both it and the mosaic at the same time, with a description of the art style or purpose of the room and a reconstructed diagram of the art. Of course, at a basic level it is very important to be able to see both the information & diagrams and the mosaic at the same time to be able to understand and compare the information to reality and encourage learning and critical thought.

A shell mosaic

Something which I only spotted on my second visit was “the digital palace”, an amazing model which lets the user explore a reconstructed villa, clicking to walk into different rooms and looking around in 3d using the mouse. This was on understated computer desk in the middle of the exhibition which the user had to sit down to use, hopefully the museum will be able to find a way to make this technology easier to access for everybody to see and enjoy on a bigger screen!

The computer desk with “the digital palace” on the screen

Computer screen showing a digital model of a roman room, it says “Room N1, Hypocaust Room

Information and instructions about The Digital Palace; a representation of the North Wing made by Anthony Crew.

At the far end of the room there is a viewing platform displaying a slideshow of old and funny images of the archaeological process, and the options of three films called “1960s excavations”, “New Discoveries” and “Mosaic Care”. The use of audio and video technology allows a different way of presenting the archaeology than in the rest of the exhibit which gives the audience a different way to learn that appeals to them most, not to mention being very valuable for visually impaired or hearing impaired visitors. My only concern was that there were no chairs, meaning that visitors must stand to watch the films, which can be difficult or offputting- I also found the soundscapes coming from the viewing platform to be a bit odd.

The Hadley Trust viewing platform showing Barry Cunliffe working on the Medusa mosaic

Garden

The garden didn’t engage me as much but my grandmother loved it; she said she enjoyed the “colourful part with flowers and the pretty green shaped hedges”. It can be difficult for people without an interest in history to engage with museums, but the way the garden was portrayed clearly made an impact on her and she said that she would be happy to revisit based on that. It was designed to look like the grand garden of a Roman villa, with a beautiful scented lavender bed funded by the friends of Fishbourne Roman palace.

View of the gardens; a big grassy space surrounded by hedges laid out in angular patters.

The best part of the garden for me was the themed Roman flower beds. I thought it was an incredibly creative idea, with each flower bed representing a different theme, including medicine, herbs, beauty and all sorts. It smelled and looked incredible and that sensory experience made all the difference to me in enjoying the garden. I’m not sure if my grandma noticed the themes but she loved the flower beds in the same way as I did, noticing the strong scents and bright colours.

A flowerbed with a panel which says “medicinal plants”

Collections Discovery Centre

This building is separate to the museum, opened by Tony Robinson on Time Team in 2007, allows visitors to see artefacts in a more peaceful and very well lit modern area separate to the main museum. There are interactive drawers where visitors can open them to see collections of pottery, glass, bone and more and curated displays behind windows. Visitors are able to look through the window displays and see the store room and scientific research room, adding a new depth to the museum which isn’t just about the Roman history but also the archaeological process and storage of artefacts, which Fishbourne highlights very well.

A window into the conservation laboratory

Artefacts in drawers which visitors can open.

Artefacts in drawers which visitors can open.

A window into the conservation laboratory

The Sensitive Store is behind a window display, which displays a variety of artefacts

All in all our visit to Fishbourne was very enjoyable, and I was inspired by the way in which they portrayed Roman history and culture to a modern audience. I’ll be posting soon about their “hands on” area, which was an incredible way of engaging all ages and types of audience in hands on activities related to archaeologists and archaeology. Following that I’ll be using this research to construct a theoretical plan of how we could portray Malton as a site if we were to have a visitor centre or museum, so stay in touch and make sure you subscribe to email notifications!

Let me know what you think in the comments or tweet me @EdgyTrowel!

This article was written by myself with help from Chloe Rushworth, you can check out her heritage blog and posts about the Malton dig here: https://archloology.wordpress.com/. Photos by myself and my Grandmother.

I visited Fishbourne Roman Palace: Here's my review on how they engage their audience... This week I had the opportunity to visit Fishbourne Roman Palace, and was very excited to see how they portray a Roman site to the public and engage their visitors.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yokai Watch News: Yokai Watch 4 & Forever Friends

The official websites have updated with new information again, and Corocoro has been released for this month as well.

So, as always I will translate and summarize the most notable news that have come out from this.

Beware of spoilers, naturally!

--

This time around we got news about:

Yokai Watch 4

5th Yokai Watch Movie - Forever Friends

Merchandise

New Yokai for Puni Puni and World

This time around there won’t be much of Corocoro because for the most part the websites either updated with the same information, or there isn’t much new info to begin with.

--

Yokai Watch 4 News:

Corocoro has released information about Yokai Watch 4, and the official website of the game has updated as well.

For the most part both of these just go over information that is evident from simply watching the trailer and the demo footage, both of which I have translated already.

That of course being showing off the new battle system and graphics, as well as the fact that yokai who appeared in the Shadowside anime will also appear in the game. All of these I feel are better understood by just watching the footage.

But the website does have this bit on changing playable characters that they spell out more clearly:

操作キャラクターをチェンジ!

Change Playable Characters!

プレイヤーが操作するキャラクターを

ナツメから途中でトウマにチェンジ!

操作キャラクターを变使することで、

入る場所や使えるウォッチが変わる!?

The playable character changed

from Natsume to Touma along the way!

When you switch between playable characters,

the places you can enter and the Watch you use change!?

操作可能なキャラクターは

複数。

遊びの幅がグングン広がりそう!

There are multiple playable characters.

The scale of the game keeps expanding!

To me, this doesn’t make it completely clear if you can change characters by choice, or if there is pre-determined instances when the switching occurs.

But based on the fact that it seems that there’s places exclusive to certain characters, and how changing characters worked in 3, I’m assuming you can change between available characters whenever you want? But you might need to be certain characters to advance the plot at points.

--

Yokai Watch Movie 5 News:

This month’s Corocoro has a section on Forever Friends, but it’s fairly short, and for the most part just goes over old information. For example, all the little descriptions next to the characters are just repeats from older issues, essentially.

These are the only truly new pieces of information out of it:

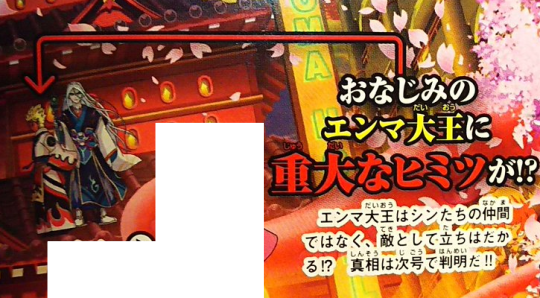

おなじみのエンマ大王に

重大なヒミツが!?

The Enma we're familiar with

has an important secret?!

エンマ大王はシンたちの仲間ではなく、 敵として立ちはだかる!? 真相は次号で判明だ!!

The Great King Enma stands before Shin and his friends, not as an ally, but as an enemy?! The truth will be revealed next issue!!

妖魔界を揺るがす戦い、そして-

エンマ大王誕生の物語!!

A battle that shakes the Yōmakai, and -

The Story of how the Great King Enma came to be!!

シンたちは妖魔界で次代のエンマ大王を決めるため開催される「エンマ武闘会」に参戦!!

ここで世界を支配しようと企む悪の妖怪と対決することに。

猫又たちの大暴れを見逃すな!!

In the Yōmakai, Shin and his friends participate in the "Enma Butōkai", which is held to determine the next Great King Enma!!

There they confront evil yokai who plot to take over the world.

Don't miss the great rampage of Nekomata and the others!!

-

Note that Cocoro also currently features the manga adaptation of this upcoming movie, though from what I hear it’s like the previous one, so it will be a fairly condensed, shortened version of the story.

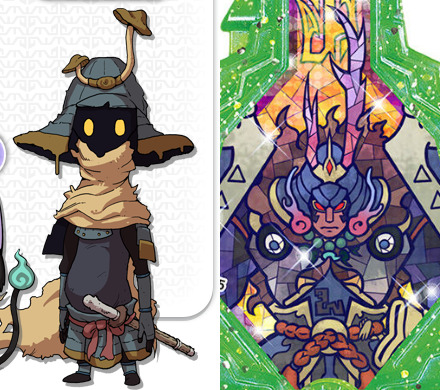

I’ve not seen anyone post full scans of the manga chapters, which is understandable, but this image has been making the rounds, featuring a new character who could presumably show up on the full movie as well:

His name is 紫炎/Shien, which is written with the kanji for “purple” and “blaze”, and the caption informs us that he is a candidate for becoming the next Great King Enma.

Now, while this isn’t much info, the new merchandise I am about to go over is all tied to the movie as well.

--

Yokai Watch Merchandise News:

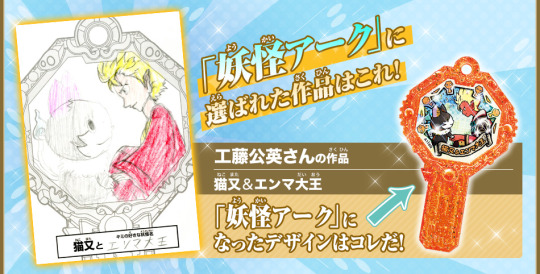

First of all, the official website for the 5th movie has updated to feature the winner of the Yokai Ark Design Contest, where children where supposed to draw an Ark design, featuring their favorite yokai together with Nekomata.

And the winning design is the one that will be turned into an actual Ark:

However, there is various lesser prices as well, which I have gone over before, and various magazines will gradually reveal the rest of the winners.

-

Next up, the b-boys website has updated with two more toy sets that are coming up.

First is the “DX Yokai Watch Elda Zero & Jin Power-up Kit”.

This entire kit will be released in December and will cost 2400 Yen.

It comes with two new covers one can attach to their Yokai Watch Elda (sold seperately) to give it either the “Zero” or “Jin” look:

Adding to that, this banner here talks about how one will be able to download update data for the Yokai Watch Elda, to get it up to speed:

The URL listed there will supposedly provide additional information on how to update the Elda, but as of right now it doesn’t seem to go anywhere.

Also, this kit will come with a new Yokai Ark, the first Ultimate Rare Rank, which had previously been listed as the rarest possible rank. (Though I wouldn’t wonder if they introduce better ones eventually.)

The yokai on this Ark is called “Ame no Murakumo”, which seems to be derived from ”Ame-no-Murakumo-no-Tsurugi”, the original name of the legendary sword Kusanagi.

I also want to point out that Ame no Murakumo seems to bear more than a passing resemblance to Sū-san, who was also suspiciously not given a “Godside” form in last month’s issue of Corocoro, leading me to believe the two are the same character, but that is just me speculating.

I dunno, what do you think?

-

Next is a new toy set called the “DX Enma Rod”, though note that “Enma” here is written with the kanji 炎/En (”blaze”), rather than the 閻/En from Enma’s name.

This set will be released in November and cost 4800 yen.

It’s this toy weapon:

The light in its center, called an “Oni Face” here, is said to be able to glow in 7 colors, though they only show five here:

The set also includes a special “Ryūtō Yokai Ark” that can be used with the toy:

“Ryūtō“ would literally translate to “dragon light”, and from what I gather, it refers to mysterious lights, similar to will-o'-wisps, that can sometimes be seen at sea. It’s also written with the exact same kanji as the Chinese word “lóngdēng”, which refers to dragon-shaped lanters.

The two sides are called “龍燈羅雪” and “龍燈紅華”, but I don’t know what the correct pronounciation of them is. I’m going with “Ryūtō Rasetsu” and “Ryūtō Kōka” right now, but they could be wrong.

EDIT: “Ryūtō Rasetsu” is correct, but “Ryūtō Kōka” is wrong, it should be “Ryūtō Benibana” .

This graphic depicts the different play functions:

The first, labelled with “1″, shows the way you’re supposed to summon the “dragons of fire and ice”, so, the dragon depicted on the Ark.

It’s as simple as turning the Ark to the left for the ice dragon, and to the right for the fire dragon. After turning the Ark, the toy will play a different tune depending on the dragon, and then pushing the trigger will “summon” the dragon of your choice.

The second, labelled with “2″ is the fact that the light will turn into different colors and play different sounds depending on how long and often you push the trigger.

What’s interesting is this part:

This part mentions that you can use other Arks too, who have a different sound, but it also mentions a “Yasha Enma”, without explaining who or what that actually is.

It’s also said that the Ryūtō Yokai Arks can be used with the Yokai Watch Elda, too.

-

And one last merchcandise thing, Corocoro teases that in their next issue they will reveal/talk about a “Yokai Ark Movie Special Pack”, which based on its name I am just going to assume will be a Yokai Ark pack with Arks specifically based on yokai from the movie?

--

Yokai Watch Mobile Games News:

This is going to be brief, since it’s just new yokai that were announced.

First off, Yokai Watch Puni Puni has a new event, which has already started as of the writing of this post, I believe.

It celebrates the game’s 3rd Anniversary, and adds new crossover characters with other notable franchises of Level-5, as well as Shadowside Hi no Shin/Hinozall:

-

And finally, Corocoro has shown off various Halloween-themed yokai variants that are coming to Yokai Watch World.

They’re Majokko Fubuki-hime, Trick Hikikōmori, 8-tōjin Hallowhis, Horror Orochi, Vampire Kyūbi, and Halloween Jibanyan.

The event will start on the 22nd, but of course this game can only be played in Japan.

--

And that’s it for the notable news from this month so far, I hope you found this helpful and/or interesting!

--

#yokai watch#youkai watch#yo kai watch#yokai watch 4#yokai watch movie 5#yokai watch translations#my translations#corocoro leaks#website updates

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Remember Longcat, Jane? I remember Longcat. Fuck the picture on this page, I want to talk about Longcat. Memes were simpler back then, in 2006. They stood for something. And that something was nothing. Memes just were. “Longcat is long.” An undeniably true, self-reflexive statement. Water is wet, fire is hot, Longcat is long. Memes were floating signifiers without signifieds, meaningful in their meaninglessness. Nobody made memes, they just arose through spontaneous generation; Athena being birthed, fully formed, from her own skull.

You could talk about them around the proverbial water cooler, taking comfort in their absurdity. “Hey, Johnston, have you seen the picture of that cat? They call it Longcat because it’s long!” “Ha ha, sounds like good fun, Stevenson! That reminds me, I need to show you this webpage I found the other day; it contains numerous animated dancing hamsters. It’s called — you’ll never believe this — hamsterdance!” And then Johnston and Stevenson went on to have a wonderful friendship based on the comfortable banality of self-evident digitized animals.

But then 2007 came, and along with it came I Can Has, and everything was forever ruined. It was hubris, Jane. We did it to ourselves. The minute we added written language beyond the reflexive, it all went to shit. Suddenly memes had an excess of information to be parsed. It wasn’t just a picture of a cat, perhaps with a simple description appended to it; now the cat spoke to us via a written caption on the picture itself. It referred to an item of food that existed in our world but not in the world of the meme, rupturing the boundary between the two. The cat wanted something. Which forced us to recognize that what it wanted was us, was our attention. WE are the cheezburger, Jane, and we always were. But by the time we realized this, it was too late. We were slaves to the very memes that we had created. We toiled to earn the privilege of being distracted by them. They fiddled while Rome burned, and we threw ourselves into the fire so that we might listen to the music. The memes had us. Or, rather, they could has us.

And it just got worse from there. Soon the cats had invisible bicycles and played keyboards. They gained complex identities, and so we hollowed out our own identities to accommodate them. We prayed to return to the simple days when we would admire a cat for its exceptional length alone, the days when the cat itself was the meme and not merely a vehicle for the complex memetic text. And the fact that this text was so sparse, informal, and broken ironically made it even more demanding. The intentional grammatical and syntactical flaws drew attention to themselves, making the meme even more about the captioning words and less about the pictures. Words, words, words. Wurds werds wordz. Stumbling through a crooked, dead-end hallway of a mangled clause describing a simple feline sentiment was a torture that we inflicted on ourselves daily. Let’s not forget where the word “caption” itself comes from: capio, Latin for both “I understand” and “I capture.” We thought that by captioning the memes, we were understanding them. Instead, our captions allowed them to capture us. The memes that had once been a cure for our cultural ills were now the illness itself.

It goes right back to the Phaedrus, really. Think about it. Back in the innocent days of 2006, we naïvely thought that the grapheme had subjugated the phoneme, that the belief in the primacy of the spoken word was an ancient and backwards folly on par with burning witches or practicing phrenology or thinking that Smash Mouth was good. Fucking Smash Mouth. But we were wrong. About the phoneme, I mean. Theuth came to us again, this time in the guise of a grinning grey cat. The cat hungered, and so did Theuth. He offered us an updated choice, and we greedily took it, oblivious to the consequences. To borrow the parlance of a contemporary meme, he baked us a pharmakon, and we eated it.

Pharmakon, φάρμακον, the Greek word that means both “poison” and “cure,” but, because of the limitations of the English language, can only be translated one way or the other depending on the context and the translator’s whims. No possible translation can capture the full implications of a Greek text including this word. In the Phaedrus, writing is the pharmakon that the trickster god Theuth offers, the toxin and remedy in one. With writing, man will no longer forget; but he will also no longer think. A double-edged (s)word, if you will. But the new iteration of the pharmakon is the meme. Specifically, the post-I-Can-Has memescape of 2007 onward. And it was the language that did it, Jane. The addition of written language twisted the remedy into a poison, flipped the pharmakon on its invisible axis.

In retrospect, it was in front of our eyes all along. Meme. The noxious word was given to us by who else but those wily ancient Greeks themselves. μίμημα, or mīmēma. Defined as an imitation, a copy. The exact thing Plato warned us against in the Republic. Remember? The simulacrum that is two steps removed from the perfection of the original by the process of — note the root of the word — mimesis. The Platonic ideal of an object is the source: the father, the sun, the ghostly whole. The corporeal manifestation of the object is one step removed from perfection. The image of the object (be it in letters or in pigments) is two steps removed. The author is inferior to the craftsman is inferior to God.

Fuck, out of space. Okay, the illustration on page 46 is fucking useless; I’ll see you there.

But we’ll go farther than Plato. Longcat, a photograph, is a textbook example of a second-degree mimesis. (We might promote it to the third degree since the image on the internet is a digital copy of the original photograph of the physical cat which is itself a copy of Platonic ideal of a cat (the Godcat, if you will); but this line of thought doesn’t change anything in the argument.) The text-supplemented meme, on the other hand, the captioned cat, is at an infinite remove from the Godcat, the ultimate mimesis, copying the copy of itself eternally, the written language and the image echoing off each other, until it finally loops back around to the truth by virtue of being so far from it. It becomes its own truth, the fidelity of the eternal copy. It becomes a God.

Writing itself is the archetypical pharmakon and the archetypical copy, if you’ll come back with me to the Phaedrus (if we ever really left it). Speech is the real deal, Socrates says, with a smug little wink to his (written) dialogic buddy. Speech is alive, it can defend itself, it can adapt and change. Writing is its bastard son, the mimic, the dead, rigid simulacrum. Writing is a copy, a mīmēma, of truth in speech. To return to our analogous issue: the image of the cheezburger cat, the copy of the picture-copy-copy, is so much closer to the original Platonic ideal than the written language that accompanies it. (“Pharmakon” can also mean “paint.” Think about it, Jane. Just think about it.) The image is still fake, but it’s the caption on the cat that is the downfall of the republic, the real fakeness, which is both realer and faker than whatever original it is that it represents. Men and gods abhor the lie, Plato says in sections 382 a and b of the Republic.

οὐκ οἶσθα, ἦν δ᾽ ἐγώ, ὅτι τό γε ὡς ἀληθῶς ψεῦδος, εἰ οἷόν τε τοῦτο εἰπεῖν, πάντες θεοί τε καὶ ἄνθρωποι μισοῦσιν;

πῶς, ἔφη, λέγεις;

οὕτως, ἦν δ᾽ ἐγώ, ὅτι τῷ κυριωτάτῳ που ἑαυτῶν ψεύδεσθαι καὶ περὶ τὰ κυριώτατα οὐδεὶς ἑκὼν ἐθέλει, ἀλλὰ πάντων μάλιστα φοβεῖται ἐκεῖ αὐτὸ κεκτῆσθαι.

“Don’t you know,” said I, “that the veritable lie, if the expression is permissible, is a thing that all gods and men abhor?”

“What do you mean?” he said.

“This,” said I, “that falsehood in the most vital part of themselves, and about their most vital concerns, is something that no one willingly accepts, but it is there above all that everyone fears it.”

Man’s worst fear is that he will hold existential falsehood within himself. And the verbal lies that he tells are a copy of this feared dishonesty in the soul. Plato goes on to elaborate: “the falsehood in words is a copy of the affection in the soul, an after-rising image of it and not an altogether unmixed falsehood.” A copy of man’s false internal copy of truth. And what word does Plato use for “copy” in this sentence? That’s fucking right, μίμημα. Mīmēma. Mimesis. Meme. The new meme is a lie, manifested in (written) words, that reflects the lack of truth, the emptiness, within the very soul of a human. The meme is now not only an inferior copy, it is a deceptive copy.

But just wait, it gets better. Plato continues in the very next section of the Republic, 382 c. Sometimes, he says, the lie, the meme, is appropriate, even moral. It is not abhorrent to lie to your enemy, or to your friend in order to keep him from harm. “Does it [the lie] not then become useful to avert the evil—as a medicine?” You get one fucking guess for what Greek word is being translated as “medicine” in this passage. Ding ding motherfucking ding, you got it, φάρμακον, pharmakon. The μίμημα is a φάρμακον, the lie is a medicine/poison, the meme is a pharmakon.

But I’m sure that by now you’ve realized the (intentional) mistake in my argument that brought us to this point. I said earlier that the addition of written language to the meme flipped the pharmakon on its axis. But the pharmakon didn’t flip, it doesn’t have an axis. It was always both remedy and poison. The fact that this isn’t obvious to us from the very beginning of the discussion is the fault of, you guessed it, language. The initial lie (writing) clouds our vision and keeps us from realizing how false the second-order lie (the meme) is.

The very structure of the lying meme mirrors the structure of the written word that defines and corrupts it. Once you try to identify an “outside” in order to reveal the lie, the whole framework turns itself inside-out so that you can never escape it. The cat wants the cheezburger that exists outside the meme, but only through the meme do we become aware of the presumed existence of the cheezburger — we can’t point out the absurdity of the world of the meme without also indicting our own world. We can’t talk about language without language, we can’t meme without mimesis. Memes didn’t change between ‘06 and ‘07, it was us who changed. Or rather, our understanding of what we had always been changed. The lie became truth, the remedy became the poison, the outside became the inside. Which is to say that the truth became lie, the pharmakon was always the remedy and the poison, and the inside retreated further inside. It all came full circle. Because here’s the secret, Jane. Language ruined the meme, yes. But language itself had already been ruined. By that initial poisonous, lying copy. Writing.

The First Meme.

Language didn’t attack the meme in 2007 out of spite. It attacked it to get revenge.

Longcat is long. Language is language. Pharmakon is pharmakon. The phoneme topples the grapheme, witches ride through the night, our skulls hide secret messages on their surfaces, Smash Mouth is good after all. Hey now, you’re an all-star. Get your game on.

Go play.”

#by every god that ever was my dude#holy shit#save#this is the best existential crisis i've ever had#yall seem to think my writing is pretty okay but i can only dream of meeting this author#in a hypothetical dream of the future in which we are peers#for my mortal life#i will have to sustain myself by learning from their teachings#and bettering my understanding of their nigh-divine unholy wisdom#submission

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

A thesis on memes by reddit user cosmic daddy_ (WARNING: Long Post is Long)

...