#Graball Landing

Text

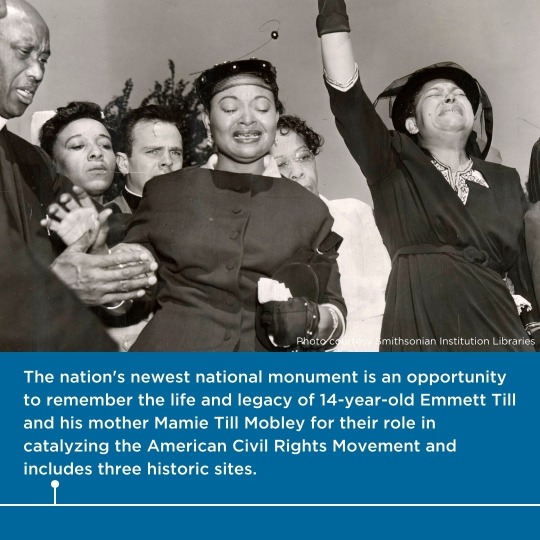

U.S. President Joe Biden on Tuesday will honor Emmett Till, the Black teenager whose 1955 killing helped galvanize the Civil Rights movement, and his mother with a national monument across two states.

Till, 14 and visiting from Chicago, was beaten, shot and mutilated in Money, Mississippi, on Aug. 28, 1955, four days after a 21-year-old white woman accused him of whistling at her. His body was dumped in a river.

The violent killing put a spotlight on the U.S. civil rights cause after his mother, Mamie Till-Bradley, held an open-casket funeral and a photo of her son's badly disfigured body appeared in Black media.

The national monument designation across 5.7 acres (2.3 hectares) and three sites marks a forceful new effort by the President to memorialize the country's bloody racial history even as Republicans in some states push limits on how that past is taught.

"America is changing, America is making progress," said the Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr., 84, a cousin of Till's who was with the boy on the night he was abducted at gunpoint from the relatives' house they were staying at in Mississippi.

"I've seen a lot of changes over the years and I try to tell young people that they happen, but they happen very slow," Parker said on Monday in a telephone interview as he traveled from Chicago to Washington to attend the signing ceremony at the White House as one of approximately 60 guests.

Tuesday marks the 82nd anniversary of Till's birth in 1941. One of the monument sites is the Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ in Chicago, where Till's funeral took place.

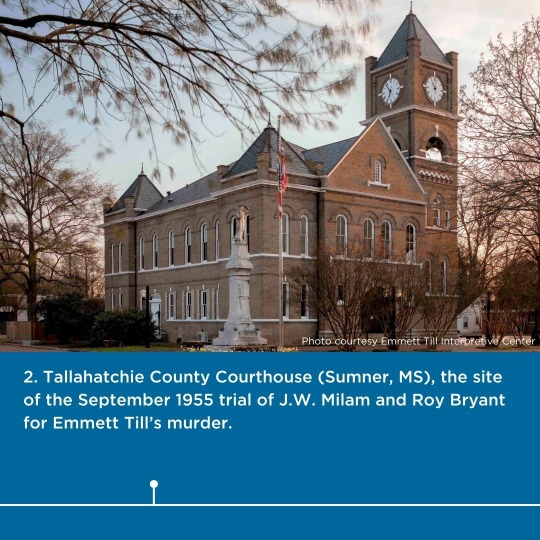

The other selected sites are in Mississippi: Graball Landing, close to where Till's body is believed to be have been recovered; and Tallahatchie County Second District Courthouse, where two white men who later confessed to Till's killing were acquitted by an all-white jury.

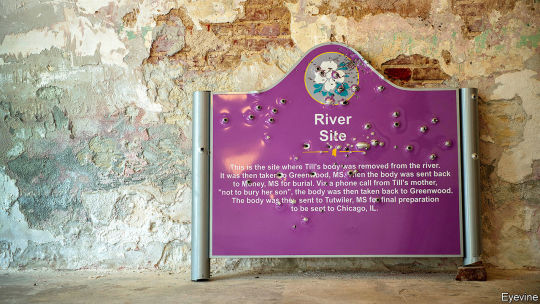

Signs erected at Graball Landing since 2008 to commemorate Till's killing have been repeatedly defaced by gunfire.

Now that site and the others will be considered federal property, receiving about $180,000 a year in funding from the National Park Service. Any future vandalism would be investigated by federal law enforcement rather than local police, according to Patrick Weems, executive director of the Emmett Till Interpretive Center in Sumner, Mississippi.

Other such monuments include the Grand Canyon, Statue of Liberty and the laboratory of inventor Thomas Edison.

Biden, an 80-year-old Democrat, will likely need strong support from Black voters to secure a second term in the 2024 presidential election.

He screened a film recounting the lynching, "Till," at the White House in February. Last March, he signed into law a bipartisan bill named for Till that for the first time made lynching a federal hate crime.

A Republican field led by former President Donald Trump has made conservative views on race and other contentious issues of history a part of their platform, including banning books and fighting efforts to teach school children accounts of the country's past that they regard as ideologically inflected or unpatriotic.

"This is an amazing, teachable moment to talk about the importance of this story as an American story that everybody can share in now, particularly at a time when people are trying to rewrite history," said Christopher Benson, president of the non-profit organization the Emmett Till & Mamie Till-Mobley Institute in Summit, Illinois.

“We have a memorial now that is not erasable. It can't be banned and it can't be censored, and we think that's a very important thing.”

#us politics#news#reuters#2023#biden administration#president joe biden#Emmett Till#national monuments#Mississippi#Illinois#Mamie Till-Bradley#civil rights movement#Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr.#Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ#Graball Landing#Tallahatchie County Second District Courthouse#Patrick Weems#Emmett Till Interpretive Center#Christopher Benson#Emmett Till & Mamie Till-Mobley Institute#racism#white supremacists#white supremacy#lynching

579 notes

·

View notes

Text

"When President Joe Biden signed a proclamation Tuesday establishing a national monument honoring Emmett Till and his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, it marked the fulfillment of a promise Till’s relatives made after his death 68 years ago.

The Black teenager from Chicago, whose abduction, torture and killing in Mississippi in 1955 helped propel the Civil Rights Movement, is now an American story, not just a civil rights story, said Till’s cousin the Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr.

“It has been quite a journey for me from the darkness to the light,” Parker said during a proclamation signing ceremony at the White House attended by dozens, including other family members, members of Congress and civil rights leaders.

“Back then in the darkness, I could never imagine the moment like this, standing in the light of wisdom, grace and deliverance,” he said.

With the stroke of Biden’s pen, the Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley National Monument, located across three sites in two states, became federally-protected places. Before signing the proclamation, the president said he marvels at the courage of the Till family to “find faith and purpose in pain.”

“Today, on what would have been Emmett’s 82nd birthday, we add another chapter in the story of remembrance and healing,” Biden said...

On Tuesday, reaction poured in from other elected officials and from the civil rights organizing community. The Rev. Al Sharpton said the Till national monument designation tells him “that out of pain comes power.”

House Democratic Leader Hakeem Jefferies said the monument “places the life and legacy of Emmett Till among our nation’s most treasured memorials.”

“Black history is American history,” he said in a written statement...

Till-Mobley demanded that Emmett’s mutilated remains be taken back to Chicago for a public, open casket funeral that was attended by tens of thousands of people. Graphic images taken of Emmett’s remains, sanctioned by his mother, were published by Jet magazine and fueled the Civil Rights Movement...

Altogether, the Till national monument will include 5.7 acres (2.3 hectares) of land and two historic buildings. The Mississippi sites are Graball Landing, the spot where Emmett’s body was pulled from the Tallahatchie River just outside of Glendora, Mississippi, and the Tallahatchie County Second District Courthouse in Sumner, Mississippi, where Emmett’s killers were tried...

The Illinois site is Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ in Chicago, where Emmett’s funeral was held in September 1955...

Mississippi state Sen. David Jordan, 90, was a freshman at Mississippi Valley State College in 1955 when he attended part of the trial of the two men charged with killing Emmett. As a state senator for the past 30 years, Jordan, who is Black, spearheaded fundraising for a statue of Emmett Till that was dedicated last year in Greenwood, Mississippi, a few miles from where the teenager was abducted.

On Tuesday, Jordan praised Biden for creating the Till national monument.

“It’s one of the greatest honors that a president could pay to a person, 14, who lost his life in Mississippi that’s created a movement that changed America,” Jordan told the AP."

-via AP, July 25, 2023

#black lives matter#civil rights#civil rights movement#emmett till#lynching#illinois#chicago#mississippi#united states#us politics#us history#american history#black history#african america history#joe biden#democrats#hakeem jeffries#national monument#national parks#national parks service#racism#cw murder#anti blackness#jim crow#cw lynching#cw torture#cw mutilation#hope

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

⚖️#ArtIsAWeapon

#NeverForget

#EmmettTill #MamieTillMobley

Today (July 25, 2023), on what would have been Emmett Till’s 82nd birthday, President Joe Biden signed a proclamation to establish the Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley National Monument honoring Till and his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley. In 1955, Emmett was 14 when he was kidnapped, tortured and murdered because a white woman accused him of “inappropriately interacting" with her.

Reposted from @savingplaces Meet our nation’s newest national monument, the Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley National Monument... which includes:

- Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ (Chicago, Illinois), founded in 1916. Following Mamie Till Mobley’s decision to “let the world see what I’ve seen,” an estimated 100,000 people filed past Emmett’s casket over three days in September 1955.

- Tallahatchie County Courthouse (Sumner, Mississippi), the site of the September 1955 trial of J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant for Emmett Till’s murder. The building was restored to its 1955 condition and the Emmett Till Interpretive Center opened across the street to provide interpretation.

- Graball Landing on the banks of the Tallahatchie River in Mississippi, the site where Emmett Till’s body was found.

This new national monument is an opportunity for the nation to remember the life and legacy of 14-year-old Emmett Till and his mother, Mamie Till Mobley, for catalyzing the American #CivilRightsMovement.

“Imbued in these now permanently protected buildings and landscapes are the unspeakable crimes of racial violence, and the tireless strength of Mamie Till Mobley who harnessed her grief in pursuit of #socialjustice. Through historic preservation, this multiracial coalition of partners will continue its work to uplift this new national monument and secure the resources and investment needed to ensure the site's future.”

- Brent Leggs, Executive Director, African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund

Swipe to learn about how the National Trust's Action Fund has supported sites related to this important history.

#TellTheFullStory #SavingPlaces #AACHAF @tillnationalpark @npcapics

#AmericanHistory #whiteSupremacy

0 notes

Link

From the Emmett Till Interpretive Center:

Official statement July 25, 2019

Over ten years ago, the Emmett Till Memorial Commission began putting up signs to commemorate the murder of Emmett Till. This was the first effort of its kind in Mississippi. Local citizens raised private funds to begin our own truth telling process after issuing an official apology to the Till family for our community’s role in the tragedy and injustice.

Our aim is to use the history of the murder to spark conversations about the corrosive effects of racism, past and present. Although the perpetrators of Till’s murder have never faced justice, the commission is using Till’s story to pursue racial reconciliation in the twenty-first century. While retributive justice may be elusive, restorative justice is still possible.

The efforts of the Commission have been severely hampered by vandalism. Our signs and ones like them have been stolen, thrown in the river, replaced, shot, replaced again, shot again, defaced with acid and have had KKK spray painted on them. The vandalism has been targeted and it has been persistent. Occasionally, the national news has picked up the story. More often, these acts have gone unnoticed and been the responsibility of our community to maintain.

We ask that you join us in our effort and consider helping the Commission continue the work of seeking racial justice in one of the poorest counties in the country.

The Commission is pursuing five current initiatives:

First, the Commission is developing Graball Landing, the site on the Tallahatchie River where Till’s body was pulled from the water. It is also the site of the most egregious vandalism and, for this reason, a powerful site at which to teach reconciliation. We have recently entered into a contract with a local land owner to establish permanent access to the site. Working with different stakeholders, we will create a forum for development of the site and begin work to create a site of conscience. This site will provide public access and ensure safety moving forward by including a gate and security cameras.

Second, the Commission is installing a fourth sign at Graball Landing—a bullet proof sign. Unlike the first three signs, this sign calls attention to the vandalism itself. We believe it is important to keep a sign at this historic site, but we don’t want to hide the legacy of racism by constantly replacing broken signs. The commission hopes this sign will endure, and that it will continue to spark conversations about Till, history, and racial justice.

Third, the Commission is developing a website and mobile application to take users to the most vandalized and most important sites in Till’s story. Created in partnership with the Till family and a range of scholars, the Emmett Till Memory Project (website and app) will be live in the fall of 2019. Although we have secured funding to build the project, we need increased support to maintain it and expand the range of stories it tells.

Fourth, the Commission is conducting a capital campaign. As a nonprofit in a region defined by poverty, the Commission depends on contributions from across the country. Please consider taking a look at our campaign and making a monthly donation below.

Fifth, we are currently in the process to become a National Park. Thanks to efforts by Senator Thad Cochran and the Mississippi Delegation, a bill was passed to study Mississippi Civil Rights Sites. This has been our highest hope since our organization was founded. In 1955 the federal government refused to get involved in the Till case. We believe it is now the responsibility of Congress and the President to ensure this story is told for generations to come. Please sign up for our newsletter at the bottom of the page to find out ways you can reach out to Congress to ensure that a Mamie and Emmett Till National Park is created in the coming years.

Today is the 64th anniversary of Emmett Till’s murder. If you’ve reblogged other posts about him at any point, please consider also sharing this.

As stated above, the historical marker where Emmett’s body was found has been vandalized multiple times since it was put up and this campaign is to replace the sign with after fraternity members from Ole Miss posted pictures posing in front of the sign covered in bullet holes while holding guns. This happened this year, 2019.

Replacing the sign with a bulletproof alternative would not only protect Emmett’s memory, but I'm sure also give his surviving family and other black and brown members of the community some peace of mind.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Memories of Emmett Till

ON THE MORNING of November 2nd, six white men and two women, dressed in uniforms of dark tops and khaki trousers, gathered on the east bank of the Tallahatchie river in the Mississippi Delta. One carried the flag of a group called the League of the South, which advocates for “Anglo-Celtic” supremacy. Its founder, Michael Hill, said: “We are here at the Emmett Till monument that represents the civil-rights movement for blacks. What we want to know is: when are all of the white people over the last 50 years that have been murdered, assaulted and raped by blacks going to be memorialised?”

This is not the first time that the spot, which is near the point where, in 1955, the mutilated body of an African-American boy named Emmett Till was pulled from the waters, has attracted racist protests. The monument is the fourth marker on the riverbank. The others have been stolen, thrown in the river, replaced, riddled with bullet holes, cut down, replaced again, shot up again and replaced for a third time. Because of the vandalism, the new memorial, erected two weeks before the protest, weighs 500 pounds and is made of reinforced steel covered in bulletproof glass. It is also surrounded by security cameras. When the cameras picked up the protest and triggered an alarm, the protesters ran away. The event was widely reported as showing that racism still bedevils the commemoration of civil rights in the Deep South. That is true. But there is more to the story than that.

Get our daily newsletter

Upgrade your inbox and get our Daily Dispatch and Editor's Picks.

Within a 20-mile radius of the memorial at Graball Landing (named after a dock for unloading goods) are over two dozen places associated with Emmett Till’s final days. They include a museum, two restored buildings, a park and nature trail (now overgrown) and a community centre. Poverty, denial, indifference, local rivalries and greed, as well as racist violence, have all beset these commemorations of Emmett Till, and muted the racial reconciliation that public acts of remembrance are intended to bring about.

Twenty miles downstream from Graball Landing stands Bryant’s Grocery and Meat Market, a shop in the village of Money. It was here, on the evening of August 24th 1955, that Till, a 14-year-old from Chicago who was visiting his uncle, wolf-whistled at a white shop assistant, Carolyn Bryant. She claimed in court that he had propositioned and assaulted her, though many years later she said that was untrue. Outside the shop stands a roadside sign which says Bryant’s Grocery marks the first step in a sequence of events that was to lead to Till’s torture, murder and the American civil-rights movement itself.

Paradoxically, putting up the sign contradicts the stance taken by lawyers acting for the Till family at the time. In court, they tried to suppress the episode at the grocery, fearing (rightly, it turned out) that Mrs Bryant’s story would be taken by the all-white jury as evidence that Till had broken one of the sexual taboos of the south.

The condition of the building is testimony to a continuing reluctance to confront that historic racism. Bryant’s is a ruin. Hurricane Katrina tore the roof off in 2005. The shop front and rafters had collapsed by 2010. A “disgrace” to the local community, said one visitor who offered to buy the site.

Its neglect stands in sharp contrast to the building next door: Ben Roy’s gas (petrol) station. Whereas Bryant’s has been left to rot, the gas station has been lovingly restored with a grant from the state of Mississippi to something like its condition in the 1950s. The garage has no connection with the events of Emmett Till’s murder but restoration was justified on the specious grounds that people may have sat on the porch discussing it (which is unlikely: locals ignored the story for decades). The contrast between Bryant’s and Ben Roy’s, argues Dave Tell of the University of Kansas and author of a new book, “Remembering Emmett Till”, shows that, in the Delta, it is easier to commemorate the charm of rural nostalgia than the ugly facts of lynching.

Both buildings and the village of Money have been bought by the Tribble family, descendants of one of the jurors who acquitted Emmett Till’s killers. Over the years, they have rejected a stream of offers to restore Bryant’s. At the moment, according to Jerry Mitchell of the Clarion-Ledger, a Mississippi newspaper, they are trying to get the National Park Service to buy the ruin for $4m, but that is many times its value and the park service rarely buys properties. In 2018, surveying the wreck, a relative of Emmett Till said of the Tribble family “they just want history to die.”

They are not the only ones. The state of Mississippi has done little to keep Till’s history alive. Commemoration has been left to a local group, the Emmett Till Memorial Commission (ETMC), founded in 2006 with the aim of using commemoration to promote racial reconciliation; it has nine black and nine white board members. Lacking money or statewide influence, it has had to raise cash however it can. In practice, that has meant accommodating historical accuracy to other requirements.

Emmett Till was killed by Mrs Bryant’s husband, Roy, two half-brothers, J.W. and Leslie Milam, a brother-in-law, Melvin Campbell, and at least three other men. They beat the 14-year-old literally to a pulp before gouging out one eye with a penknife and shooting him. The photograph of his mutilated face turned the killing into a cause célèbre in Chicago, where the picture was published. Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam were arrested and acquitted at a trial in Sumner, 30 miles north of Money. To add insult to barbarity, they admitted they had killed Till in a magazine, Look; they were paid $3,150 for the story.

Contested connections

In 2006 the courthouse where their trial took place was dilapidated and its restoration became the first test of the ETMC’s ability to use other aims to advance its goals of commemoration and racial reconciliation. These mixed aims caused problems from the start. “All of the blacks”, said one commissioner, “focus on how horrible the crime was, and the need for acceptance of responsibility.” A white member said “we see this Till thing as a way to get funds to restore the courthouse.” The building has been beautifully restored and is still working. The ETMC offered an apology to the Till family on behalf of the county. But the interpretative centre, which was supposed to teach about the murder and reconciliation, is a dusty shell, itself in need of restoration.

It is a similar story at Glendora, a small town 16 miles south, which has by far the largest collection of memorials, including an Emmett Till museum. They reflect the efforts of the long-serving mayor, Johnny B. Thomas, to bring business to his poverty-stricken town. Glendora is one of the poorest towns in the impoverished Delta (“our Haiti,” says one local). There is even an NGO, Partners in Development, devoted to combating poverty in Haiti, Guatemala, Peru—and Glendora. In 2009 the Mississippi Development Authority sent a team of economists to the town. After describing it as a place with “no hope”, they said its only viable asset was civil-rights tourism. Mr Thomas enthusiastically set about providing sites for the hoped-for visitors.

The Till museum was financed using money from the US Department of Agriculture meant for rural broadband services in rural areas. The redirection of funds may perhaps be justified: Glendora has no broadband but the museum is still going. The trouble is that the town has so little to do with Till’s history. One of the murderers lived there, but his house disappeared decades ago. The town’s other claimed connections—that Till’s body was thrown into the river there, weighed down by a chunk of farm machinery from a local factory tied round his neck with barbed wire—have not withstood scrutiny. Efforts to enroll Glendora’s museum on America’s National Register of Historic Places have been rejected. To judge by the number of memorials, Glendora was the birthplace of the civil-rights movement. In reality, these sites reflect Mr Thomas’s efforts to combat the poverty of his town.

The lynching of Emmett Till did help launch the civil-rights movement in America. A later black leader, the Rev Jesse Jackson, said Rosa Parks, the first lady of civil rights, had told him that she refused to give up her bus seat to a white man, precipitating the first large protests against segregation, because “I thought of Emmett Till and couldn’t go back”. To reflect this national significance, Patrick Weems, the executive director of the ETMC, wants the National Park Service to take over the sites. Local efforts have run up against multiple problems. But they testify to the refusal of Emmett Till to go away.■

https://ift.tt/34U8Ntg

0 notes

Text

Bulletproof Emmett Till Memorial Unveiled After Repeated Vandalism

TALLAHATCHIE COUNTY, Miss. ― Despite vandals’ repeated attempts to erase the memory of Emmett Till from this community, a new memorial has been erected in honor of the civil rights martyr. And this time, it’s stronger than ever.

Members of Till’s family gathered Saturday at Graball Landing, the spot where the 14-year-old’s brutalized body was pulled from the Tallahatchie River after his murder in 1955. Encircled by a vast cotton field and quintessential Mississippi flora, they watched as a new Till memorial was unveiled, this one 10 times heavier than the last, and made of bulletproof steel.

Till’s lynching, which occurred after a white woman accused him of harassing her outside of a Mississippi grocery store, is largely seen as the catalyst for the Civil Rights Movement.

“This marker answers the question as to what we do with our history,” said Reverend Willie Williams, co-director of the Emmett Till Memorial Commission, which advocated for the new marker. “Do we learn from it? Do we use it to help our society have greater respect for humanity? This answers that.”

Members of Till’s family, including his cousins Rev. Wheeler Parker — the last living witness of Till’s kidnapping ― and Ollie Gordon and her daughter Airickca Gordon-Taylor, were in attendance to christen the new marker. Unlike previous markers placed near the location, the new metallic, commemorative sign will be behind a gate and placed under the watch of surveillance cameras, according to the memorial commission.

In July, a photo circulated online showed three Ole Miss students cheerfully posing with rifles beside a bullet-riddled Emmett Till memorial. That sign and others drawing attention to Till’s killing have been frequent, literal targets for vandals wanting to obscure and destroy his legacy.

Courtesy ProPublica and the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting

From left to right, Ole Miss students Ben LeClere, John Howe, and Howell Logan posing with guns by the bullet-ridden plaque marking the place where the body of murdered civil rights icon Emmett Till was pulled from the Tallahatchie River. The photo was posted to LeClere’s Instagram account in March.

Jessie Jaynes-Diming, a civil rights tour guide and board member on the Emmett Till Memorial Commission, said the vandalism is an attempt by Mississippians to distance themselves from the state’s wretched, racist history and alleviate themselves of guilt.

“To desecrate the commemoration ― not only of a Black person, but of a 14-year-old boy ― is heartless,” she said. “And it’s their way of saying, ‘So what? I didn’t have anything to do with it. Why are y’all dredging this up?’”

In 1955, a white shopkeeper, Carolyn Bryant, accused Till of catcalling her and grabbing her outside of Bryant’s Grocery and Meat Market in Money, Mississippi. Days later, witnesses say Bryant’s husband, Roy, and his half-brother J.W. Milam kidnapped Till from his uncle’s home, then beat him, shot him in the head and threw his weighted body into the Tallahatchie River. A jury acquitted the two men that year after minutes of deliberation. Carolyn Bryant admitted decades later that her initial claims that Till harassed her were lies.

After Till’s swollen body was recovered from the river, his mother, Mamie, famously demanded an open-coffin wake at her son’s funeral to publicly show the brutality of racism in the United States.

RELATED COVERAGE

Outrage At Ole Miss Over White Students Posing With Bullet-Riddled Emmett Till Sign

New Emmett Till Memorial Will Be Made Bulletproof, Group Says

3 Mississippi Students Face Investigation After Posing With Guns At Emmett Till Sign

Download

.st0{display:none;} .st1{display:inline;} .st2{fill:#FFFFFF;} .st3{fill:#0DBE98;}

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

Join HuffPost Plus

Original Article : HERE ;

Bulletproof Emmett Till Memorial Unveiled After Repeated Vandalism was originally posted by MetNews

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Due to Repeated Vandalism, Emmett Till Memorial to Be Replaced with Bulletproof Sign

https://sciencespies.com/history/due-to-repeated-vandalism-emmett-till-memorial-to-be-replaced-with-bulletproof-sign/

Due to Repeated Vandalism, Emmett Till Memorial to Be Replaced with Bulletproof Sign

In 2007, a sign was erected along the Tallahatchie River in Mississippi, marking the spot where the body of Emmett Till was pulled from the water in 1955. The murder of Till, a 14-year-old African-American boy who was brutally killed by two white men, became a galvanizing incident of the Civil Rights Movement. But over the years, the memorial commemorating his death has been repeatedly vandalized—first stolen, then shot at, then shot at again, according to Nicole Chavez, Martin Savidge and Devon M. Sayers of CNN. Now, the Emmett Till Memorial Commission is planning to replace the damaged memorial with a bulletproof sign.

This will be the fourth sign that the commission has placed at the site. The first was swiped in 2008, and no arrests were ever made in connection with the incident. The replacement marker was vandalized with bullets, more than 100 rounds over the course of several years. Just 35 days after it was erected in 2018, the third sign was shot at as well.

The third memorial made headlines recently when Jerry Mitchell of the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, in conjunction with ProPublica, revealed that three University of Mississippi students had been suspended from their fraternity house after posing in front of the sign with guns, in a photo that was posted to the private Instagram account of one of the students. The Justice Department is reportedly investigating the incident.

The sign has now been taken down, and a new one is “on its way,” Patrick Weems, executive director of the Emmett Till Memorial Commission, said last week, according to CBS News. Chavez, Savidge and Sayers of CNN report that the replacement memorial will weigh 600 pounds and be made of reinforced steel. It is expected to go up by the Tallahatchie River in October.

“Unlike the first three signs, this sign calls attention to the vandalism itself,” the commission noted. “We believe it is important to keep a sign at this historic site, but we don’t want to hide the legacy of racism by constantly replacing broken signs. The commission hopes this sign will endure, and that it will continue to spark conversations about Till, history, and racial justice.”

Till, a native of Chicago, was visiting relatives in Mississippi when he had a fateful encounter with a white woman named Carolyn Bryant, who claimed the teenager had flirted with her. The woman’s husband and brother subsequently kidnapped Till, beat him viciously, shot him in the head and threw him into the Tallahatchie River. His body was so disfigured that when it was found three days later, it could only be identified by Till’s signet ring. At Till’s funeral, his mother decided to leave the casket open, bearing witness to the brutal racism that had killed her son. Photos of Till’s mangled body, published in Jet magazine, gave rise to a generation of Civil Rights activists.

The men who killed Till, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam, were put on trial for the crime. They were found not guilty by an all-white jury.

As part of its efforts to keep Till’s story ever-present in the public consciousness, the Emmett Till Memorial Commission is planning a number of initiatives. The group is, for instance, working with a local landowner to develop Graball Landing, the riverside location where Till’s body was recovered, into a “site of conscience”—with a security gate and cameras. A website and mobile app that will let users explore important sites in Till’s story are also in the works. The team is additionally lobbying for the establishment of a “Mamie and Emmett Till National Park.”

But a pressing priority is to get a reinforced Till memorial back up along the Tallahatchie River.

“We won’t stop. There will be another sign up,” Reverend Willie Williams, the commission’s treasurer, tells CNN. “This particular area will go forward in the long run. Because this legacy and this story, it’s much bigger than any of us.”

Like this article?

SIGN UP for our newsletter

#History

0 notes