#Emmett Till & Mamie Till-Mobley Institute

Text

U.S. President Joe Biden on Tuesday will honor Emmett Till, the Black teenager whose 1955 killing helped galvanize the Civil Rights movement, and his mother with a national monument across two states.

Till, 14 and visiting from Chicago, was beaten, shot and mutilated in Money, Mississippi, on Aug. 28, 1955, four days after a 21-year-old white woman accused him of whistling at her. His body was dumped in a river.

The violent killing put a spotlight on the U.S. civil rights cause after his mother, Mamie Till-Bradley, held an open-casket funeral and a photo of her son's badly disfigured body appeared in Black media.

The national monument designation across 5.7 acres (2.3 hectares) and three sites marks a forceful new effort by the President to memorialize the country's bloody racial history even as Republicans in some states push limits on how that past is taught.

"America is changing, America is making progress," said the Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr., 84, a cousin of Till's who was with the boy on the night he was abducted at gunpoint from the relatives' house they were staying at in Mississippi.

"I've seen a lot of changes over the years and I try to tell young people that they happen, but they happen very slow," Parker said on Monday in a telephone interview as he traveled from Chicago to Washington to attend the signing ceremony at the White House as one of approximately 60 guests.

Tuesday marks the 82nd anniversary of Till's birth in 1941. One of the monument sites is the Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ in Chicago, where Till's funeral took place.

The other selected sites are in Mississippi: Graball Landing, close to where Till's body is believed to be have been recovered; and Tallahatchie County Second District Courthouse, where two white men who later confessed to Till's killing were acquitted by an all-white jury.

Signs erected at Graball Landing since 2008 to commemorate Till's killing have been repeatedly defaced by gunfire.

Now that site and the others will be considered federal property, receiving about $180,000 a year in funding from the National Park Service. Any future vandalism would be investigated by federal law enforcement rather than local police, according to Patrick Weems, executive director of the Emmett Till Interpretive Center in Sumner, Mississippi.

Other such monuments include the Grand Canyon, Statue of Liberty and the laboratory of inventor Thomas Edison.

Biden, an 80-year-old Democrat, will likely need strong support from Black voters to secure a second term in the 2024 presidential election.

He screened a film recounting the lynching, "Till," at the White House in February. Last March, he signed into law a bipartisan bill named for Till that for the first time made lynching a federal hate crime.

A Republican field led by former President Donald Trump has made conservative views on race and other contentious issues of history a part of their platform, including banning books and fighting efforts to teach school children accounts of the country's past that they regard as ideologically inflected or unpatriotic.

"This is an amazing, teachable moment to talk about the importance of this story as an American story that everybody can share in now, particularly at a time when people are trying to rewrite history," said Christopher Benson, president of the non-profit organization the Emmett Till & Mamie Till-Mobley Institute in Summit, Illinois.

“We have a memorial now that is not erasable. It can't be banned and it can't be censored, and we think that's a very important thing.”

#us politics#news#reuters#2023#biden administration#president joe biden#Emmett Till#national monuments#Mississippi#Illinois#Mamie Till-Bradley#civil rights movement#Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr.#Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ#Graball Landing#Tallahatchie County Second District Courthouse#Patrick Weems#Emmett Till Interpretive Center#Christopher Benson#Emmett Till & Mamie Till-Mobley Institute#racism#white supremacists#white supremacy#lynching

579 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Daily Don

* * * *

President Biden to name national monument for Emmet Till and his mother.

The brutal torture and murder of Emmett Till followed by his mother’s decision to hold an “open casket” funeral changed America. In 1955, a young Black teenager, Emmett Till, was abducted and killed because a white woman accused Till of “whistling” at her and grabbing her wrist. (The woman later recanted the accusations during an interview for a book.) Till’s nearly unrecognizable body was pulled from a river, where it was weighted with a 75-pound cotton gin fan secured to his neck by barbed wire. Nearly 250,000 people walked past his casket, and hundreds of thousands more saw photos of Till’s mutilated body in his casket.

Two white men were charged with the murder and acquitted by an all-white jury. The defendants confessed to the crime a few months later in an interview given to Look Magazine—for which they were paid $4,000, a hefty sum in 1956. Having been previously acquitted, they could not be tried again for murder because of the Constitution’s double jeopardy prohibition.

Emmett Till’s murder and his mother’s bravery in holding an open-casket funeral galvanized the nascent civil rights movement and helped to inspire a generation of civil rights leaders, including Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King. On Monday, President Biden announced that he is declaring three sites as a national monument to Emmett Till and his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley. See NYTimes, Biden to Name National Monument for Emmett Till and His Mother. (This article is accessible to all.)

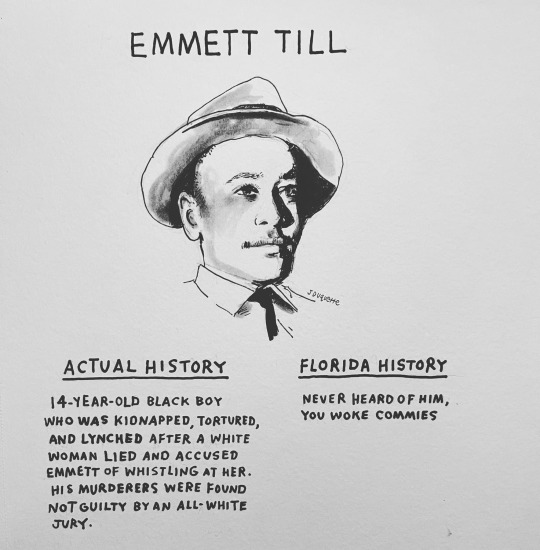

President Biden’s actions come at a moment of renewed overt racism in America. Florida’s new history curriculum includes prompts asking students to consider ways in which slavery “benefitted” enslaved persons by giving them skills they could use after emancipation. See Florida’s State Academic Standards—Social Studies, 2023. The linked document includes the following “benchmark” standard (on page 6):

Benchmark Clarifications:

Clarification 1: Instruction includes how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.

The proposed “benchmark clarification” is a stunning revision to an institution where white owners profited from forced labor by enslaved persons. To suggest that any part of that forced labor was “beneficial” is a cruel and dishonest whitewashing of a vile institution. But Ron DeSantis nonetheless defended a “pro-slavery” curriculum that his culture war unleashed in Florida. See The Independent, DeSantis defends Florida curriculum that suggests slaves benefited from forced labor.

But the Academic Standards linked above are far worse than the media portrays. The issue is not a single snippet—the language quoted above—it is the entire approach to teaching the history of slavery in the United States. I invite you to review pages 5 through 10 of the Academic Standards, and you will discover that much of the curriculum is devoted to describing slavery in Africa, Europe, and Asia—apparently to make the disgusting point that “everyone else was doing it.” For example, the “benchmark clarifications” on page 9 include the following:

Benchmark Clarifications:

Clarification 1: Instruction includes how trading in slaves developed in African lands (e.g., Benin, Dahomey).

Clarification 2: Instruction includes the practice of the Barbary Pirates in kidnapping Europeans and selling them into slavery in Muslim countries (i.e., Muslim slave markets in North Africa, West Africa, Swahili Coast, Horn of Africa, Arabian Peninsula, Indian Ocean slave trade).

Clarification 3: Instruction includes how slavery was utilized in Asian cultures (e.g., Sumerian law code, Indian caste system).

Clarification 4: Instruction includes the similarities between serfdom and slavery and emergence of the term “slave” in the experience of Slavs.

Clarification 5: Instruction includes how slavery among indigenous peoples of the Americas was utilized prior to and after European colonization.

All of the above smacks of a white-racist defense of slavery in the US. Thankfully, Joe Biden is resisting the effort by the right to erase America’s shameful history of slavery and Jim Crow laws that enforced a system of apartheid for nearly a century after the Civil War.

[Robert B. Hubbell Newsletter]

#Emmett Till#The Daily Don#Robert B. Hubbell#Robert B. Hubbell Newsletter#racism#Benchmark Clarifications#Academic Standards#monuments

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

#ArtIsAWeapon #OnThisDay in history, August 28:

▪︎In 1955, 14-year old #EmmettTill was abducted and murdered in by white supremacists;

▪︎In 1963 (60 years ago), Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his iconic "I Have A Dream" speech, which white supremacists often take out of context/misquote to "justify" their racism, bigotry and inhumanity;

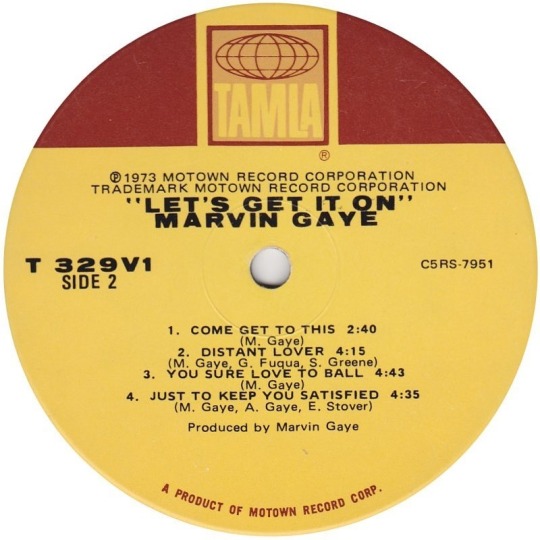

▪︎In 1973 (50 years ago), Marvin Gaye released his Soul/RnB classic album "Let's Get It On"

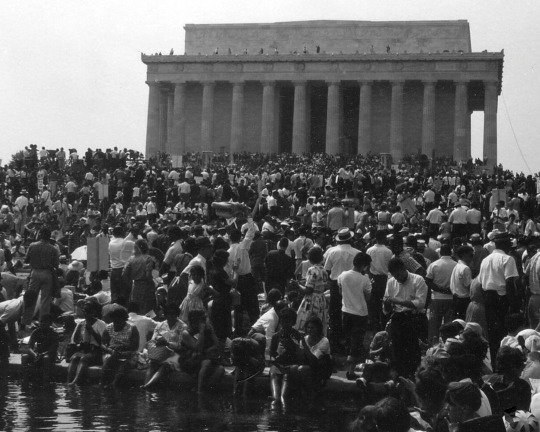

Reposted from @nmaahc #OnThisDay 60 years ago, the #MarchonWashington for Jobs and Freedom brought nearly 250,000 people to the nation’s capital to protest #racialdiscrimination and show support for #civilrights legislation pending in Congress.

For its resolute battle towards #racialunity, #socialequity, and spiritual reckoning, The March on Washington, formed Black America’s greatest love note to the world. Precipitated by increased racial hostilities in the wake of desegregation legislation and the murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till, the March on Washington sought equal access to the rights and protections guaranteed under citizenship. Identifying the Black community’s commitment to remain “wed” to the nation by upholding its mores and values, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom demanded the legitimacy of connubial ties through full citizenship. On the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington – its Diamond anniversary – the Museum examines the impassioned words of its organizers, supporters, and speakers, which made “love” the lyrical refrain and petition of their chorus for human rights.

Follow the link in our bio to immerse yourself in our museum’s resources, stories, collection items and video interviews surrounding the history of the March on Washington and the unique political and cultural impact it had on organizers, participants, and the nation. #MOW60

#OnThisDay in 1955, a murder took place in Money, Mississippi. 14-year-old Emmett Till was kidnapped in the middle of the night by two white men, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam. They tortured, beat and shot the teenager, casting his body into the Tallahatchie River tied to a cotton gin fan.

For African Americans, the murder of Till was evidence of the decades-old codes of violence exacted upon Black men and women for breaking the rules of white supremacy in the Deep South. Particularly for Black men, who, like Till, found themselves under threat of attack or death for sexual advances towards white women – which often were fabricated claims. As recently as June of this year, an arrest warrant was uncovered in Mississippi for Carolyn Bryant Donham, the White woman whose false claim instigated Till’s attack. Till’s brutal murder, and his mother Mamie’s call to display his open casket to the world, reverberated a need for immediate change.

In an effort to provide a space for history, truth, reconciliation and healing, the museum acquired Emmett Till’s original casket. The powerful object not only helps tell the difficult history of racial violence and the Civil Rights movement, but it also gives pause to visitors and makes them reflect in the same way his mother encouraged the public to do so in 1955. #APeoplesJourney #ANationsStory

📸 1. Courtesy of Bettmann/Getty Images 2. 3. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Kitty Kelley and the Estate of Stanley Tretick, © Smithsonian Institution 4. Photograph of Emmett Till with his mother, Mamie Till Mobley. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of the Mamie Till Mobley family

0 notes

Text

The Top 15 Black Films of 2022

Image: courtesy of Apple TV.

Each year, we look forward to watching films showcasing African American talent. In 2022, there were a variety of movies that spoke to our community, and even impacted our culture. Check out this round-up of some of the best films starring Black leads that came out this year.

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever

Wakanda Forever beautifully continues the legacy of the Black Panther while paying tribute to the late Chadwick Boseman.

Emancipation

Inspired by the personal account of a slave named Peter, Emancipation follows a man's quest for freedom while keeping a strong sense of self in the midst of brutality.

Till

Till gives color to the unjust murder of Emmett Till and his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley's, dedication to upholding his memory and fighting for justice.

Honk For Jesus, Save Your Soul

Peering into the life of a pastor and his first lady as they work to move past a major scandal, Honk For Jesus, Save your Soul is a deep portrayal of how far one's faith will take them to protect a legacy while balancing the shadow of public opinion.

Devotion

Devotion follows Jesse Brown as he makes history as the U.S. Navy's first Black aviator. Brown is able to accomplish his dreams through the support of the love of his wife and his friends.

The Woman King

Inspired by true events, The Woman King exemplifies just how strong and passionate Black woman and gives us insight into the fierce Dahomey kingdom.

A Jazzman's Blues

Tyler Perry's latest Netflix film A Jazzman's Blues highlights the bounds of forbidden love in the Jim Crow south.

Nope

The latest thriller film in the Jordan Peele universe, Nopefollows two siblings as they strive to understand the extra-terrestrial presence above their family's ranch in the clouds.

Black Adam

Dwayne "The Rock" John stars in the titular role as a demigod who strives to prove his power and status as a superhero after being dormant for 5000 years.

Alice

Alice is an enslaved woman who escapes from the brutality of her enslavers only to find that she is living in the year 1973, which is long after the abolition of slavery. She is then rescued by a pro-Black activist who opens her eyes to the lies she has been told about herself.

Breaking

Tired of the lack of respect and assistance he has been dealt, Marine veteran Brian Brown-Easley holds several individuals hostage inside a bank leading to a tense confrontation with law enforcement. Breaking is the late actor Michael K. William's last film.

Master

At a prestigious predominately white institution in New England, a newly appointed Black professor and student discover an evil presence oppressing Black folks on the campus.

Wendell & Wild

13-year old rebel Kat would do anything to see her parents again including selling her soul to two wily demons named Wendell and Wild. Kat quickly learns that her wish is not as simple as it seems, and discovers a scheme to devastate her home town.

Nanny

A foreign woman works hard to support herself and her child only for her dreams and reality to become burdened by a violent, supernatural entity.

Fantasy Football

A daughter learns that she has the power to up her father's game on the football field through a video game console.

Highlights of the 2022 Afro Nation Festival

Sent from my iPhone

0 notes

Text

ABC NEWS ANNOUNCES NEW PODCAST SERIES CHRONICLING THE LIFE AND LEGACY OF MAMIE TILL-MOBLEY

First Episode of ‘Reclaimed: The Story of Mamie Till-Mobley' Debuts Wednesday, June 1

*ABC News

Today, ABC News released the trailer for its new three-part podcast series, “Reclaimed: The Story of Mamie Till-Mobley.” Hosted by historian and ABC News contributor Leah Wright-Rigueur, the new series chronicles the life and legacy of Mamie Till-Mobley, whose fight for justice after her son’s brutal murder helped spark the civil rights movement. The first episode of “Reclaimed: The Story of Mamie Till-Mobley" debuts Wednesday, June 1, with new episodes posting weekly. The podcast promotes and updates ABC News’ limited docuseries “Let The World See,” streaming now on Hulu.

In 1955, Mamie Till-Mobley’s 14-year-old son, Emmett Till, was accused of offending a white woman in a Mississippi grocery store. Shortly after, a group of men kidnapped Emmett from a relative’s home and a local fisherman discovered his tortured body in the Tallahatchie River. Using Till-Mobley’s own words, as well as interviews from family members and other eyewitnesses, “Reclaimed” tells the story of a woman, mother and activist who made the courageous decision to let the world see the injustice and brutality her son faced.

The podcast series details Till-Mobley’s early upbringing in the Chicago area as well as the pivotal moments in her life, including her defiant and consequential choice to hold an open-casket funeral for Emmett, which shocked the world and inspired many heroes of the civil rights movement. It also includes lesser-known details about the 1945 death of her husband, Louis Till, who the U.S. military executed in France during World War II.

Drawing from the ABC News limited docuseries, “Let the World See,” and over 40 hours of interviews, the podcast features reflections from former First Lady Michelle Obama, who discusses the social and political environment in Chicago in the 1950s and her connection to the city. The series also features interviews with Emmett Till’s cousin Rev. Wheeler Parker, who witnessed Emmett’s kidnapping; individuals who attended the trial of the men charged with Emmett’s murder; as well as historical and legal experts who provide context to these events and Till-Mobley’s impact on American history.

The series is part of ABC Audio’s newly rebranded “Reclaimed” podcast feed, which launched in 2021 with the release of “Soul of a Nation: Tulsa’s Buried Truth.” The new “Reclaimed” feed focuses on the people, events and moments that have rested on the periphery of history. Each season seeks to uncover the hidden truths in familiar stories by shedding light on those who have been overlooked.

“Reclaimed: The Story of Mamie Till-Mobley” is available for free on major listening platforms, including Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music, Google Podcasts, iHeartRadio, Stitcher, TuneIn, Audacy and the ABC News app. “Reclaimed” is the latest addition to the free “ABC News” channel on Apple Podcasts, one of the top-ranked channels in 2021.

“Reclaimed” is produced by ABC Audio. Liz Alesse is vice president of ABC Audio and executive producer of this podcast.

About Leah Wright-Rigueur:

Leah Wright-Rigueur is a political historian, award-winning researcher, author and ABC News contributor. She is an expert in 20th century American political and social history, modern African American history, race, civil rights, politics and more. Rigueur is a SNF Agora Institute associate professor of history at Johns Hopkins University, and a faculty fellow at the Ash Institute for Democratic Governance and Innovation at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, The New Yorker, as well as on PBS, The History Channel, HBO and more.

About ABC Audio:

With distribution to over 1,900 radio stations and digital distributors, ABC Audio is the premier source for audio news, entertainment and music format services in the United States. ABC Audio syndicates ABC News Radio, where more Americans get their radio news than any other commercial broadcaster. ABC Audio includes Air Power, station services with format-specific music content, entertainment and news; ABC Digital, publisher of news, entertainment, lifestyle and music format-specific stories updated 24/7; and syndicated music and talk programming brands. ABC Audio also produces world-class on-demand content, including ABC News’ flagship daily podcast “Start Here” and the international chart-topping hit “The Dropout.”

*COPYRIGHT ©2022 American Broadcasting Companies, Inc. All photography is copyrighted material and is for editorial use only. Images are not to be archived, altered, duplicated, resold, retransmitted or used for any other purposes without written permission of ABC. Images are distributed to the press in order to publicize current programming. Any other usage must be licensed. Photos posted for Web use must be at the low resolution of 72dpi, no larger than 2x3 in size.

– ABC –

For more information follow ABC News PR on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

0 notes

Text

Black Voters Matter Statement on the Ahmaud Arbery Murder Trial Verdict

Today, all three defendants in the trial of the murder of Ahmaud Arbery, were found guilty of felony murder. All three men will now face hate-crime charges in federal court in February. Cliff Albright and LaTosha Brown, co-founders of Black Voters Matter, who supported local protests with the Transformative Justice Coalition and organizers on-the-ground, issued the following statement in response to the verdict:

“Every now and again our justice system gets it right. In the case of three white men who racially profiled, hunted and murdered 25 year old, Ahmaud Arbery, a jury of 11 white men and women, and one Black man, handed down a guilty verdict for slaughtering a man who was jogging while Black in his South Georgia neighborhood. This outcome is due in large part to the Arbery family whose relentless desire to seek justice for their son propelled the case forward.

“In fact, just as Mamie Till-Mobley insisted that the media publish photos of her murdered son, Emmett Till, 65 years ago to raise awareness and support for a trial, so did the Arbery family through their insistence on releasing the video of their son being murdered to the public. It was that act of transparency that really made this trial possible.

“However, much like the trial of George Floyd’s murderer, where the state attorney had to step in to prosecute the case, it’s very telling that the only way to get justice for Arbery — in a community that is 55% Black — was to take it out of the hands of local prosecutors, who had already demonstrated their refusal to prosecute the case fairly. A clear reminder that local elections continue to play an important role in the lives of Black voters.

“Furthermore, the defense’s case, fueled by racially-charged language, was deplorable, seeking to dehumanize Arbery at every step. Part of the ongoing demand for justice should include holding these attorneys accountable for their actions.

“But with all this said, we know that Wanda Cooper-Jones and Marcus Arbery will never get back their son.

“BVM stands in solidarity with Arbery’s family and the Brunswick community who supported them. We know this verdict is an indicator of how strong the will of the people is and how we can bring about change when we work together in pursuit of justice.”

Black Voters Matter, a 501c4, and Capacity Building Institute, a 501c3, are dedicated to expanding Black voter engagement and increasing progressive power through movement-building and engagement. Working with grassroots organizations, specifically in key states in the South, BVM seeks to increase voter registration and turnout, advocate for policies to expand voting rights/access, and help develop infrastructure where little or none exists to support a power-building movement that keeps Black voters and their issues at the forefront of our election process. For more information, please visit https://www.blackvotersmatterfund.org/

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emmett Till’s Murder, and How America Remembers Its Darkest Moments

Emmett Till’s Murder, and How America Remembers Its Darkest Moments

https://ift.tt/2SeMIif

We're using augmented reality, a new approach to digital storytelling. Read about how to use it on your phone or tablet here. If you want to skip it for now, you can view an alternate immersive experience instead.

MONEY, Miss. — Along the edge of Money Road, across from the railroad tracks, an old grocery store rots.

In August 1955, a 14-year-old black boy visiting from Chicago walked in to buy candy. After being accused of whistling at the white woman behind the counter, he was later kidnapped, tortured, lynched and dumped in the Tallahatchie River.

The murder of Emmett Till is remembered as one of the most hideous hate crimes of the 20th century, a brutal episode in American history that helped kindle the civil rights movement. And the place where it all began, Bryant’s Grocery & Meat Market, is still standing. Barely.

Today, the store is crumbling, roofless and covered in vines. On several occasions, preservationists, politicians and business leaders — even the State of Mississippi — have tried to save its remaining four walls. But no consensus has been reached.

Some residents in the area have looked on the store as a stain on the community that should be razed and forgotten. Others have said it should be restored as a tribute to Emmett and a reminder of the hate that took his life.

As the debate has played out over the decades, the store has continued to deteriorate and collapse, even amid frequent cultural and racial reckonings across the nation on the fate of Confederate monuments. At stake in Money and other communities across the country is the question of how Americans choose to acknowledge the country’s past.

“It’s part of this bigger story, part of a history that we can learn from,” said the Rev. Wheeler Parker, 79, a pastor in suburban Chicago and a cousin of Emmett’s who went with him to Bryant’s Grocery that day. “The store should be one of the places we share Emmett’s story.”

(The Justice Department quietly reopened the Emmett Till case last year after Carolyn Bryant Donham, the white shopkeeper, recanted parts of her story.)

In and around the Delta, the memory of Emmett’s murder lingers.

The cotton gin from which the 75-pound fan that was tethered to his neck with barbed wire was stolen is now a small museum. There are informal tours of the abandoned bridge where his body was likely tossed into the river. The barn where he was brutally beaten is unmarked, but its owner allows the occasional visitor.

Emmett Till with his mother, Mamie Till Mobley, circa 1950. Everett Collection, via Alamy

And, on a larger stage, his story is the subject of upcoming feature films and books.

But not everybody sees the memorials the same way. Several historical markers put up to commemorate Emmett have repeatedly been vandalized, shot down and replaced.

To nurture racial reconciliation in the area, the Emmett Till Memorial Commission was founded in 2006. It restored the courtroom in Sumner where Emmett’s killers — Roy Bryant, the owner of the store in the 1950s, and his half brother, J.W. Milam — were acquitted. Outside, a marker commemorating Emmett stands steps from a monument honoring Confederate soldiers.

Ray Tribble, who sat on the jury of all-white men who acquitted Mr. Bryant and Mr. Milam, purchased the building that was once Bryant’s Grocery in the 1980s. He died in 1998. The store has been in the Tribble family ever since.

The family has all but refused to restore or sell the property. And it continues to wither away.

Drag image to explore

The remnants of Bryant’s Grocery & Meat Market, in Money, Miss.

‘Tear Off the Scab’

Willie Williams and Donna Spell grew up about eight miles from each other in the Delta. They are 10 years apart in age. He learned about Emmett Till as a child. She learned about him as an adult. Mr. Williams is black. Ms. Spell is white.

Mr. Williams said his parents told him about Emmett’s story “as a way of being careful.” Ms. Spell said Emmett’s horrific death was not a story “my parents would have told their children.”

The two first met at a church event. Today, they both sit on the Emmett Till Memorial Commission, where they have since become friends.

“I did a lot of listening. And what I heard was a lot of pain,” said Ms. Spell, a longtime English teacher. “To move forward we’ve got to tell the story. We’ve got to tear off the scab and keep telling it.”

In 2006, the Emmett Till Memorial Highway was dedicated along a 32-mile stretch of U.S. 49 East. A year later, the commission presented an official apology to the Till family in the courthouse where the killers were acquitted.

Drag image to explore

The Emmett Till Memorial Commission restored the courtroom in Sumner where Emmett’s killers were acquitted. The courtroom was segregated during the trial in 1955.

“Our community had been running from this since 1955,” said Patrick Weems, co-founder of the Emmett Till Interpretive Center, a museum across from the courthouse that was started by the group.

The commission has since placed 11 historical markers at sites related to Emmett’s murder. One of them sits on a lonely dirt road next to rows and rows of cotton fields near Glendora, Miss. It’s a purple sign marking the nearby riverbank where Emmett’s body was recovered.

The sign has had to be replaced three times because of bullet holes and vandalism. Other civil rights markers in Mississippi have also been targeted — two years ago, vandals scraped the words and text off the Bryant’s Grocery marker, and “KKK” was once scrawled across the highway sign.

Several historical markers have been erected to honor Emmett. One of them, a purple sign marking the nearby riverbank where his body was recovered, has been repeatedly vandalized.

On a recent afternoon, one of the commission’s damaged signs rested on the floor of the museum. Mr. Weems leaned over it as he ran his fingers across the jagged holes.

“It’s been a struggle to keep those signs up,“ Mr. Weems said, “but we think it’s part of the front line of this tug of war between memory and how we negotiate our past and future.”

[For more coverage of race, sign up here to have our Race/Related newsletter delivered weekly to your inbox.]

Drag image to explore

The riverbank where Emmett’s body was recovered.

Confronting History

Susan Glisson has worked with a half-dozen Mississippi towns on racial healing, including in Sumner with the Emmett Till Memorial Commission. After she retired as director of the University of Mississippi’s William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation, she founded Sustainable Equity, a consulting firm focused on facilitating racial dialogue at universities, police departments, corporations and municipalities.

“When it works, we are able to get past the perspective of ‘I didn’t do it, I don’t know anybody that did it,’ and find the ways to honor the victims,” Ms. Glisson said.

When it doesn’t work, she went on, the resistance is stark: communities fracture, landmarks are neglected, significant events are lost or forgotten. These moments of tension and reckoning have buckled across America as small towns confront their racist histories.

In northwest Florida, an all-black town was wiped off the map by racial violence during the Rosewood massacre in 1923. The one house that survived — where black residents hid to escape the slaughter — is now owned by an 85-year-old Japanese widow, Fujiko Scoggins. Her daughter and son-in-law, both real estate agents, are selling the home.

A small heritage group wants to convert it into a Rosewood museum and garden, but hasn’t secured funding. Neighbors warned Ms. Scoggins’s son-in-law not to sell the house to black buyers, presumably to stop any commemoration of the massacre.

The historical marker and road sign have been repeatedly vandalized. “The message is they don’t want Rosewood or the massacre to be remembered,” said Sherry Dupree, founder of the Rosewood Heritage Foundation and a tour guide.

In Monroe, Ga., a racially violent chapter is commemorated annually. Two African-American married couples were murdered by a white mob near the Moore’s Ford Bridge, after a dispute with a farmer in 1946.

Since 2005, a group of actors and activists have gathered each year to re-enact what happened that July night. “The people in town pretty much ignore it now every year,” said Cassandra Greene, who directs the performances. “But it’s important to keep doing it as a reminder of racial injustices.”

Memorials have the power to invite meaningful race conversations, Ms. Glisson added, but the key is addressing stubborn attitudes, stereotypes and assumptions that have been hardened and passed down over generations. The difficulty is getting beyond feelings of recrimination and guilt.

‘Remembering Emmett Till: The Legacy of a Lynching’ in Virtual Reality

‘It’s Been Complicated’

The price of Bryant’s Grocery & Meat Market, according to one Mississippi newspaper, is $4 million, but it’s hard to know more because the family has largely refused to talk publicly about it. Numerous messages and emails sent to the Tribbles for this story went unreturned.

In 2011, the family was awarded a $206,000 state civil rights grant to restore a gas station next to the store. At the time, the project’s architect described the store restoration as the next phase. Since 2015, Mr. Weems has negotiated with family members, to no avail.

There’s talk in town of a replica being built on state property across the street by one of the production companies filming movies about the Emmett Till case. That may be the only solution.

“It’s been complicated working with the family,” Mr. Weems said. “We have had off and on discussions with the Tribbles for about three years and it seems as if every time we get close, they move the goal post.

“And I still don’t know what they want,” he added. “I don’t know if it’s money or they want control of the story that’s told, which has direct legacy implications for their father. I am hopeful that one day they can see a positive legacy by reclaiming the past.”

Today, fewer than 100 people live in Money and most of the property, including the old Bryant’s Grocery store, is owned by the children of Ray Tribble.

Drag image to explore

The barn where Emmett was brutally beaten is unmarked, but the owner allows the occasional visitor.

As early as 2004, local business and civic leaders reached out to the Tribble family in hopes of turning the store into a museum dedicated to Emmett or civil rights, or both, even in its current state of disrepair.

That same year, the roof caved in. Then Hurricane Katrina rumbled through in 2005, destroying much of what remained. Back then, the Tribble family agreed to work to rebuild the store. “We want to restore it,” Mr. Tribble’s son, Harold Ray Jr., told The Clarion Ledger in 2007. “It’s a part of history and it’s about to fall down.”

Nothing has been done. And every day, the store slips closer toward oblivion.

“Here is this ruin that a storm could blow over, and yet it’s still here,” said Dave Tell, an author and professor working on a new book about the Emmett Till case.

“The store is this great analogy to the story of Emmett Till, both long neglected, but both refuse to go away.”

CREDITS

Written by Audra D.S. Burch.

Produced by Veda Shastri.

Drone Video and Photos by Tim Chaffee.

Archival Images: Everett Collection via Alamy, Ed Clark/Time & Life Pictures via Getty Images, Associated Press

Graphics and Design by Nicole Fineman, Jon Huang, and Karthik Patanjali.

Research by Susan C. Beachy

Senior Producer: Maureen Towey

Executive Producers: Lauretta Charlton, Marcelle Hopkins and Graham Roberts

A Grocery, a Barn, a Bridge: Returning to the Scenes of a Hate Crime

Emmett Till’s Murder: What Really Happened That Day in the Store?

In Texas, a Decades-Old Hate Crime, Forgiven but Never Forgotten

Talking to a Man Named Mr. Cotton About Slavery and Confederate Monuments

Veda Shastri contributed reporting, andSusan C. Beachy contributed research.

Advertisement

https://ift.tt/301mY0P

via The New York Times

September 15, 2019 at 06:51PM

0 notes

Text

Funny How The Second Amendment Is Absolute And All Encompassing, But The Fourteenth Amendment Can Be Basically Line-Item Vetoed

“You’re gonna need congressional approval and you don’t have the votes / Such a blunder sometimes it makes me wonder why I even bring the thunder.” — Lin-Manual Miranda, “Cabinet Battle #1” (Hamilton)

As I was driving through Mississippi on Devil’s Night, Maureen Corrigan’s book review of Let the People See The Emmett Till Story, by Elliott Gorn, broadcasted over the local National Public Radio (NPR) station. It was a haunting reminder of the legacies we have all inherited. As I was passing through the endless night horizon of Mississippi, Corrigan’s chillingly narrative bled through my car speakers:

‘Let the people see what they did to my boy.’ Those were the words spoken by Emmet Till’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, after viewing the brutalized body of her son.

During his night of torture near the Delta town of Money, Mississippi, 14-year-old Till’s right eye had been dislodged from its socket, his tongue choked out of his mouth, the back of his skull crushed and his head penetrated by a bullet.

Shortly after Corrigan’s Fresh Air segment, NPR commentators and their guests spoke about the Tree of Life synagogue massacre, yet another act of domestic terrorism in a seemingly endless string of mass shootings our country has witnessed this decade. With a sense of foreboding, the on-air commentators and their guests were not only concerned about Robert Bowers’s 11 executions via his AR-15 rifle and three handguns on October 27, but the broader, recent rise and empowerment of white nationalism throughout our country.

In 2015, prior to the most recent presidential election, I warned:

Maybe it’s hard for me to stomach the recently renewed attack on the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because I fear the root cause of these sentiments. As Mark Twain supposedly said, ‘History may not repeat itself, but it does rhyme.’

The strong anti-foreigner feelings of past generations are being revived as a rationale to make our country great again. At what cost?

I fear America’s deep legacy of anti-Asian racism will continue to haunt our future generations. Now the anti-immigrant rhetoric — of ‘sanctuary cities,’ ‘border walls,’ and ‘anchor babies’ — is bringing xenophobia to the front of our country’s consciousness once again.

In the seminal Citizenship Clause case involving Wong Kim Ark, the Supreme Court stated: ‘We are entirely ready to accept the provision proposed in the constitutional amendment, that the children born here of Mongolian parents shall be declared by the Constitution of the United States to be entitled to civil rights and to equal protection before the law with others.’

Back then, some politicians argued that the Chinese were so different in so many ways that they could never assimilate into American culture, and they represented a threat to the country’s principles and institutions.

Just last year, I documented the death of Aylan Kurdi and the refugee crisis:

Since the conflict in Syria began in 2011, until the photography date of Aylan Kurdi’s [three-year old] lifeless body, the United States had taken in only about 1,500 Syrian refugees. That is not a typo: 1,500 Syrian refugees total. When Obama raised the Syrian ceiling to 10,000 — a more reasonable number I suppose, but still an unbearably low moral figure, he faced a massive outcry from conservatives. Last week, many politicians paid tribute to Holocaust Memorial Day and the millions of innocent lives lost, and these politicians pledged, ‘Never again.’ Yet they turn a blind-eye to our current refugee crisis….

Whereas Canada has accepted almost 40,000 refugees to much celebration by its citizens, Obama’s 10,000 target has now become, under Donald Trump, a complete and total shutdown of Syrian and Muslim refugees.

The current refugee crisis is the issue of our lifetime and we have met it with little to no fanfare. America was once viewed as a beacon of hope. Lady Liberty represented freedom and opportunity. But now we have plans to build a much vaunted wall while we permit our most at-risk communities to drown in lead-contaminated water.

We pledge to never let millions of innocent lives suffer again or deprive our communities of their most basic needs. But how easily we forget. Humanity washed along the shore, and we walked by. We are witnessing so many refugee hands reach out, but we refrain from reaching back. For the first time in my life, I don’t recognize this country.

Shortly after Kurdi’s death, his relatives were admitted into Canada as refugees. At least, in Canada, Aylan Kurdi did not die in vain.

Now, with only days until the midterms, the Trump administration is continuing to amplify its dog-whistle propaganda campaign on immigration and crime, to dehumanize migrants and others and arrest asylum seekers. Meanwhile, acts of domestic terrorism receive much less consternation. For too many of our country’s leaders, it’s always “too early to talk about gun control regulation” and “too soon to react, politically or otherwise, to the latest mass murder.”

They deem the Second Amendment to be absolute and interpret its words — “[a] well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed” — to mean that citizens have every right to tote around AR-15s. Surely many would protest, one hand on the heart and the other on a trigger, if any president stated he could change this interpretation and the law with an executive order.

Yet the Fourteenth Amendment is much less sacred to those same people who pledge such loyalty to the Constitution. Its words — “[a]ll persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside” — have been interpreted the same way for the past 150 years. With one fell swoop of the pen, Trump believes he can change this. And so do many of his loyal followers.

This would be funny, if it weren’t so sad… and scary as shit.

My ATL colleague Elie Mystal opined on the subject recently in his column Post Runs White Nationalist Propaganda Masquerading As Law-Talkin’:

WHERE IS THE MISINTERPRETATION? These white assholes keep saying that we’re misreading the Fourteenth Amendment. HOW? The writers of the Fourteenth Amendment wanted to do a thing. They did it in the only way they could. THEY WROTE IT DOWN. Where’s the freaking confusion?

If you pin one of these jerks down, they’ll start talking about Native Americans. The Fourteenth Amendment didn’t confer citizenship to Native Americans, who were clearly born here, and thus, they argue, citizenship wasn’t meant to be a birthright. I have little patience for people who use our racism towards the First Americans to justify racism towards New Americans, but there you go. If you think that our treatments towards Native Americans was a feature instead of a bug, that’s your argument.

This excerpt doesn’t do Mystal’s piece justice. I highly suggest you check out his full article to see how he systematically breaks down the entire misinterpretation argument. If you are a legal nerd, you will thoroughly enjoy it.

In June, for World Refugee Day, I wrote about the harrowing historical acts of the current administration:

We are directly violating Article 31 of the Refugee Convention. Instead of addressing this issue, the Trump administration is aiming to amplify its wanton and reckless ignorance of historical precedent. The Department of Justice now plans to send Judge Advocate General’s Corps (JAG) Officers to our southern border to prosecute migrants. Maybe this administration should do better to understand the rule of law before it deploys JAG Officers, who specialize in military justice and military law, to interpret and enforce immigration laws.

The vaunted wall that the Trump administration so desperately plots to build is already being constructed brick by brick. Even if we refuse to admit it to ourselves. A separation of families’ strategy was executed on our borders, while the separation of society continues to happen within them.

Our country’s withdrawal from the United Nations Human Rights Council isn’t a bug, it’s a feature of the current administration. I’ve spoken to so many others who also feel within and without. When did we get here… while America slept?

The United States Constitution may be color blind, but our leaders certainly are not. The vast majority of the murders in our country are done with the accomplice of the Second Amendment, not the Fourteenth Amendment.

If we’re talking about how we have misinterpreted an amendment the wrong way for quite some time, let’s focus on the one that has been such a god-awful enabler of mass murders in our country.

People can talk all day about their Second Amendment rights, but we need to begin the discussion about our responsibilities. How many more mass shootings in schools, synagogues, and churches can we endure before we accept some responsibility?

Reminder: The 2018 mid-term elections will be held on Tuesday, November 6, 2018. Make sure to vote!

Renwei Chung is the Diversity Columnist at Above the Law. You can contact Renwei by email at [email protected], follow him on Twitter (@renweichung), or connect with him on LinkedIn.

0 notes

Text

Funny How The Second Amendment Is Absolute And All-Encompassing, But The Fourteenth Amendment Can Be Basically Line-Item Vetoed

“You’re gonna need congressional approval and you don’t have the votes / Such a blunder sometimes it makes me wonder why I even bring the thunder.” — Lin-Manual Miranda, “Cabinet Battle #1” (Hamilton)

As I was driving through Mississippi on Devil’s Night, Maureen Corrigan’s book review of Let the People See The Emmett Till Story, by Elliott Gorn, broadcasted over the local National Public Radio (NPR) station. It was a haunting reminder of the legacies we have all inherited. As I was passing through Mississippi’s endless-night horizon, Corrigan’s bone-chilling narrative bled through my car speakers:

‘Let the people see what they did to my boy.’ Those were the words spoken by Emmet Till’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, after viewing the brutalized body of her son.

During his night of torture near the Delta town of Money, Mississippi, 14-year-old Till’s right eye had been dislodged from its socket, his tongue choked out of his mouth, the back of his skull crushed and his head penetrated by a bullet.

Shortly after Corrigan’s Fresh Air segment, NPR commentators and their guests spoke about the Tree of Life synagogue massacre, yet another act of domestic terrorism in a seemingly endless string of mass shootings our country has witnessed this decade. With a sense of foreboding, the on-air commentators and their guests were not only concerned about Robert Bowers’s 11 executions via his AR-15 rifle and three handguns on October 27, but the broader, recent rise and empowerment of white nationalism throughout our country.

In 2015, prior to the most recent presidential election, I warned:

Maybe it’s hard for me to stomach the recently renewed attack on the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because I fear the root cause of these sentiments. As Mark Twain supposedly said, ‘History may not repeat itself, but it does rhyme.’

The strong anti-foreigner feelings of past generations are being revived as a rationale to make our country great again. At what cost?

I fear America’s deep legacy of anti-Asian racism will continue to haunt our future generations. Now the anti-immigrant rhetoric — of ‘sanctuary cities,’ ‘border walls,’ and ‘anchor babies’ — is bringing xenophobia to the front of our country’s consciousness once again.

In the seminal Citizenship Clause case involving Wong Kim Ark, the Supreme Court stated: ‘We are entirely ready to accept the provision proposed in the constitutional amendment, that the children born here of Mongolian parents shall be declared by the Constitution of the United States to be entitled to civil rights and to equal protection before the law with others.’

Back then, some politicians argued that the Chinese were so different in so many ways that they could never assimilate into American culture, and they represented a threat to the country’s principles and institutions.

Just last year, I documented the harrowing death of Aylan Kurdi and the refugee crisis:

Since the conflict in Syria began in 2011, until the photography date of Aylan Kurdi’s [three-year old] lifeless body, the United States had taken in only about 1,500 Syrian refugees. That is not a typo: 1,500 Syrian refugees total. When Obama raised the Syrian ceiling to 10,000 — a more reasonable number I suppose, but still an unbearably low moral figure, he faced a massive outcry from conservatives. Last week, many politicians paid tribute to Holocaust Memorial Day and the millions of innocent lives lost, and these politicians pledged, ‘Never again.’ Yet they turn a blind-eye to our current refugee crisis….

Whereas Canada has accepted almost 40,000 refugees to much celebration by its citizens, Obama’s 10,000 target has now become, under Donald Trump, a complete and total shutdown of Syrian and Muslim refugees.

The current refugee crisis is the issue of our lifetime and we have met it with little to no fanfare. America was once viewed as a beacon of hope. Lady Liberty represented freedom and opportunity. But now we have plans to build a much vaunted wall while we permit our most at-risk communities to drown in lead-contaminated water.

We pledge to never let millions of innocent lives suffer again or deprive our communities of their most basic needs. But how easily we forget. Humanity washed along the shore, and we walked by. We are witnessing so many refugee hands reach out, but we refrain from reaching back. For the first time in my life, I don’t recognize this country.

Shortly after Kurdi’s death, his relatives were admitted into Canada as refugees. At least, in Canada, Aylan Kurdi did not die in vain.

Now, with only days until the midterms, the Trump administration is continuing to amplify its dog-whistle propaganda campaign on immigration and crime, to dehumanize migrants and others and arrest asylum seekers. Meanwhile, acts of domestic terrorism receive much less consternation. For too many of our country’s leaders, it’s always “too early to talk about gun control regulation” and “too soon to react, politically or otherwise, to the latest mass murder.”

They deem the Second Amendment to be absolute and interpret its words — “[a] well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed” — to mean that citizens have every right to tote around AR-15s. Surely many would protest, one hand on the heart and the other hand’s finger on a trigger, if any president declared he alone could change this interpretation and the law with an executive order.

Yet the Fourteenth Amendment is much less sacred to those same people who pledge such loyalty to the Constitution. Its words — “[a]ll persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside” — have been interpreted the same way for the past 150 years. With one fell swoop of the pen, Trump believes he alone can change this. And so do many of his loyal followers.

This would be funny, if it weren’t so sad… and scary as hell.

My ATL colleague Elie Mystal opined on the subject recently in his column Post Runs White Nationalist Propaganda Masquerading As Law-Talkin’:

WHERE IS THE MISINTERPRETATION? These white assholes keep saying that we’re misreading the Fourteenth Amendment. HOW? The writers of the Fourteenth Amendment wanted to do a thing. They did it in the only way they could. THEY WROTE IT DOWN. Where’s the freaking confusion?

If you pin one of these jerks down, they’ll start talking about Native Americans. The Fourteenth Amendment didn’t confer citizenship to Native Americans, who were clearly born here, and thus, they argue, citizenship wasn’t meant to be a birthright. I have little patience for people who use our racism towards the First Americans to justify racism towards New Americans, but there you go. If you think that our treatments towards Native Americans was a feature instead of a bug, that’s your argument.

This excerpt doesn’t do Mystal’s piece justice. I highly suggest you check out his full article to see how he systematically breaks down the entire misinterpretation argument. If you are a legal nerd, you will thoroughly enjoy it.

In June, for World Refugee Day, I wrote about the harrowing historical acts of the current administration:

We are directly violating Article 31 of the Refugee Convention. Instead of addressing this issue, the Trump administration is aiming to amplify its wanton and reckless ignorance of historical precedent. The Department of Justice now plans to send Judge Advocate General’s Corps (JAG) Officers to our southern border to prosecute migrants. Maybe this administration should do better to understand the rule of law before it deploys JAG Officers, who specialize in military justice and military law, to interpret and enforce immigration laws.

The vaunted wall that the Trump administration so desperately plots to build is already being constructed brick by brick. Even if we refuse to admit it to ourselves. A separation of families’ strategy was executed on our borders, while the separation of society continues to happen within them.

Our country’s withdrawal from the United Nations Human Rights Council isn’t a bug, it’s a feature of the current administration. I’ve spoken to so many others who also feel within and without. When did we get here… while America slept?

The United States Constitution may be color blind, but our leaders certainly are not. The vast majority of the murders in our country are done with the accomplice of the Second Amendment, not the Fourteenth Amendment.

If we’re talking about how we have misinterpreted an amendment the wrong way for quite some time, let’s focus on the one that has been such a god-awful enabler of mass murders in our country.

People can talk all day about their Second Amendment rights, but we need to begin the discussion about our responsibilities. How many more mass shootings in schools, synagogues, and churches can we endure before we accept some responsibility?

Reminder: The 2018 mid-term elections will be held on Tuesday, November 6, 2018. Make sure to vote!

Renwei Chung is the Diversity Columnist at Above the Law. You can contact Renwei by email at [email protected], follow him on Twitter (@renweichung), or connect with him on LinkedIn.

Source link

The post Funny How The Second Amendment Is Absolute And All-Encompassing, But The Fourteenth Amendment Can Be Basically Line-Item Vetoed appeared first on Divorce Your Ring.

source https://divorceyourring.com/top-posts/funny-how-the-second-amendment-is-absolute-and-all-encompassing-but-the-fourteenth-amendment-can-be-basically-line-item-vetoed/

0 notes

Text

Emmett Till's Open Casket Funeral Reignited the Civil Rights Movement

Terry Westbrook-Lienert originally shared:

---

Mamie Till Mobley's decision for her slain son's ceremony was a major moment in Civil Rights history.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/emmett-tills-open-casket-funeral-reignited-the-civil-rights-movement-180956483/

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: The Possibilities and Failures of the Racial Imagination

Claudia Rankine introducing the April 9 event at the Whitney Museum (photo by Jillian Steinhauer/Hyperallergic)

Over the past few weeks, the conversation and controversy surrounding Dana Schutz’s painting of a photograph of the lynched Emmett Till, “Open Casket” — currently on view in the Whitney Biennial — has engulfed the art world. The Whitney Museum presented a public response on Sunday night, April 9, co-hosted by the writer Claudia Rankine’s Racial Imaginary Institute. For the event, 14 speakers, including the two curators of the biennial, Christopher Y. Lew and Mia Locks, were invited to give brief meditations on anything related to the topic at hand — Schutz’s painting, Emmett Till and his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, white supremacy, institutional responsibility. The three of us attended, and we found it, by turns, intriguing, depressing, boring, and exhilarating. We left wanting to talk more about this idea of the racial imagination and, in the case of the Schutz debacle, its failure.

* * *

Chloë Bass: This conversation is situated around the idea of the imaginary: The Whitney event was hosted by the Racial Imaginary Institute, which claims to operate in the service of recognizing race as a powerful construct. It addressed the imagination of an artist, Dana Schutz, which has been tagged in this case as a “failure of empathy,” and folded together the ruptures of imagination that have accompanied responses to her painting. (One clear example is the dangerous comparison of Hannah Black’s call for destruction to censorship perpetuated by the state. This is a powerful idea that we know for a fact to be false, yet it continues to circulate.)

I wanted to ask the panelists, but didn’t, what imaginaries they hope to perpetuate or produce through the execution of an exhibit. What imaginaries are perpetuated or produced through the formulation and maintenance of an institution like a museum? What are the limits or hopes of our own imaginations in response to this controversy and its outcomes?

I also want to talk about economic imaginaries: so much of the outcry around this work is, I think, a product of our ideas of value and the seemingly “neutral” value that the museum provides for a work. This neutral value is, of course, both not neutral at all — we know that museum exhibits are funded in large part by commercial galleries and private collectors so as to add a sense of intellectual worth to works already owned and up for sale — and also highly monetized. Dana Schutz stating that her painting is not for sale misses the point entirely: transactions of worth are built on imaginaries, just as the continued non-abstract violence that happens to Black bodies is built on a certain kind of imaginary. Both can be made real in a single instance (the sale of a painting, the destruction of a body) that sets a precedent for a longer-term operation of the same function (the worth of Schutz’s work going forward, the continued murder of many Black bodies). Nothing in this conversation exists in a single instance.

At the Whitney, a protest against Dana Schutz' painting of Emmett Till: "She has nothing to say to the Black community about Black trauma." http://pic.twitter.com/C6x1JcbwRa

— Scott W. H. Young (@hei_scott) March 17, 2017

Seph Rodney: Having read Chloë’s start to our conversation, I realized that I wasn’t sure what an “imaginary” actually is. I ran to a dictionary for the intellectual comfort of leaning on an authoritative text. Apparently, an imaginary is simply the product of the imagination, that which is unreal. The definitive article “the” in this definition gets to me. I think it’s not necessarily my imagination, because, as Chloë says, “Nothing in this conversation exists in a single instance”; the imaginary is suite of shared, circulating ideas. There are many of these: familial, religious, the tandem series of speculations and fantasies that I share with someone I love. There are the imaginaries I’ve inherited, of which James Baldwin recently reminded me, via director Raoul Peck’s documentary I Am Not Your Negro. Baldwin convincingly argued that the shared, productive imagination that generated the idea of a “nigger” (in which many of us trade) is completely damning: it damns the people (and their progeny, genetic and intellectual) to never grow up or become full people; it damns the future of this nation; it damns me in ways that should be fairly obvious by now. It damned Emmett Till.

I wonder what good it does to point out the failure of the imaginaries already present when I walk into a room. I mean, I know there is an ethical and emotional catharsis when I fire up my engines of indignation and let fly. I remember, as an MFA student at UC Irvine, listening to Daniel J. Martinez on one of his magnificently polemical diatribes, asking a group of seminar students why it was that, despite sustained critique by several generations of artists, the system for production of art seemed to nevertheless be increasingly shaped by a neoliberal worldview. It just came out of me, unexpectedly: “that’s because of the poverty of your imagination.” I think I meant his generation, or the UCI fine arts faculty and students, which at the time maintained a kind of smug criticality.

So I recall this and think of the dry, emaciated joy that I can get from pointing to a failure, especially a public one. There are so many ways our collective imaginary constructs have let us down that become more visible in this Whitney debacle. Chloë has indicated some in the above, and I agree with her that the painter paid insufficient attention to the primacy of her work’s content over her own practiced, formalist approach, and that Hannah Black failed to recognize that her call to destroy the work was far too self-serving, opposing what she structures as a weak and apologist position against one that is tyrannical and vindictive. There are other failures: On Sunday, Christopher Lew couldn’t or wouldn’t find a way to say something that sounded genuine, rather than a PR-vetted statement that served as institutional deflection in the guise of championing an open exchange of ideas and art’s willingness to be controversial. His colleague, Mia Locks, was a little better, though she offered only the meager opportunity to reach out and talk with her about the exhibition. Then, there is the failure of the Whitney to have meaningfully dealt with issues of representation in its exhibitions since, as Lyle Ashton Harris and Lorraine O’Grady pointed out, the 1994 Black Male show, which seemed at that bright moment to add a new paragraph to the script of crucially important museum shows.

Fred Wilson’s “Guarded View” (1991) was included in the Whitney’s 1994 Black Male exhibition. It’s shown here in the museum’s inaugural exhibition in its new home in 2015, America Is Hard to See. (photo by Jillian Steinhauer/Hyperallergic)

There is also a generational failure: those artists and teachers who believed that sustained critique allied to aesthetic production could point the way out of a racist, classist, misogynist, homophobic wilderness. They didn’t imagine that destabilizing notions of authoritative history and throwing institutions and even the notion of truth into question would not prevent angry, organized conservatives from grasping power in government and civic institutions and using that power to ratify white supremacy. They didn’t anticipate critique’s failure to prevent aesthetic production from being colonized by the market, which conditions our relations to be competitive and instrumentalist. So many failures. My throat gets thicker as I write this, because I am truly exhausted by our collective failures, and my own failure to somehow see beyond the mountains of debris around me.

Does it help that I can still envision what success would look like: an art production system uncoupled from the need to buy and sell and from the urgency to satisfy one’s ego, and a robust and genuinely respectful civic arena for public conversation, where we prioritize actually seeing and recognizing each other? It feels like a kilo of salt on my tongue as I try to articulate the term “imaginary” and wonder why we fail even in our thoughts (where we might be most free).

Jillian Steinhauer: First off, I want to say that both of you are extremely smart, and I am humbled to be having this conversation with you.

Probably because I’m white, what has struck me the most in almost every aspect of the Schutz debacle — from creation of painting to display to protest to aftermath — has been the failure of the white imagination. As Ryan Wong wrote in his brilliant piece for Hyperallergic, “Why do white artists think the only way you can discuss race is through the suffering of people of color?” It’s not just artists, but the vast majority of white people — we are able only to conceive of race as something that belongs or happens to people of color (I mean, look at the term “people of color”). Because we are taught, by white supremacy, that we are raceless, or post-race. So, you get someone like Schutz, but also many others before her, who think that the only way to engage with racial issues is to try to empathize with the position of a person of color — not to try to understand her own position as a white person. That’s the failure that is so crucial to me: not recognizing that white supremacy renders whiteness invisible, and that undoing white supremacy means intervening in that quiet, nefarious process by naming whiteness — by recognizing and pointing out how it works and our own relationship to it.

Others have said this in different ways, and I agree and want to restate it here: what if, instead of painting Emmett Till, Dana Schutz had painted Carolyn Bryant, the white woman who knowingly, falsely accused Till of grabbing and threatening her? Is there some kind of constructive work a painting like that could do?

Dana Schutz’s “Open Casket” (2016) (photo by Benjamin Sutton/Hyperallergic)

The other glaring failure of the white imagination that I see here — both in Schutz and in the Whitney, which is, at the end of the day, a white institution, despite having enlisted two Asian Americans to curate the biennial — is the complete inability to foresee how Black viewers might respond to that painting. This failure is so absurd, honestly, that I find myself coming to the appalling conclusion that it might never have even occurred to Schutz or the higher-ups at the Whitney that Black viewers would see the painting. Because the presumed art audience is white. As you said, Chloë, we need to stop operating in the myth that museums are neutral spaces. “Neutral” usually means “white,” and white is a dangerous power construct.

To borrow Lyle Ashton Harris’s words from Sunday night, I have no interest in having a “kumbaya moment” here, but I’m curious if either of you sees any of the failures here as potentially productive or somehow offering a clue about how to move forward.

CB: I’ve said before, and am happy to say again here, that I don’t think the job of the artist is to invoke realities neither we nor our intended audience can imagine, and then expect to change the world. I don’t know for sure, but maybe that’s what Dana Schutz was hoping to do: take something that wasn’t hers (as opposed to the Carolyn Bryant story, which was definitely up for her grabs) and give it, through curators whose story this also wasn’t, to an institution that didn’t get it, to viewers that the institution assumed wouldn’t notice (and here I draw directly from your point about assuming there’s no Black audience, Jillian). All of these failed imaginings result in the continuation of a system that we know to fall short in dramatic and ongoing ways.

So this is where I want to add something new with regards to the question of responsibility: I don’t think this is about the Whitney at all. Neither do I think it’s about Dana Schutz, Hannah Black, or any of the other cast of characters who have spoken on this topic. I can imagine a world without all of these institutions and individuals. If I’m really being honest, the only person I can’t imagine the world without is myself (although it’s an interesting thought exercise). What this indicates to me is that responsibility starts with me. I see disavowing, or somehow unseeing, my own subject position as the beginning of a chain of wild inaccuracies. I might want a world where I ask other people to position themselves in the same way. I think many people do this, but it’s also an thing easy to forget when we’re working at the scale of tackling an entire system.

Seph and Jillian, you both make clear that wild white imaginations result in controlled death. I guess what I want to ask, or optimistically point to, as a first condition of improving our imaginations and their results, is where we permit violence in our own lives. How can we let go of the desperation and scarcity mentality that force us to keep relying on the Whitney, or any other institution, even when they fail us time and time again? Who are we hoping to please? I’m asking for a world where we give ourselves permission to move beyond these pale beliefs. I still believe in institutional accountability, but I also think we can do more than just exhaust ourselves with constant call-outs of a system that has built up centuries of defense against active listening. (Defenses, I might add, that we now mimic as individuals.)

Here’s one positive suggestion: what if white artists and institutions, instead of capitalizing on and re-airing Black pain, created space to celebrate Black joy (without capitalizing on it)? It doesn’t seem so hard to do this. I think we could all really be happy there. Black joy is expansive and resilient. If you think there’s no way to do this without capitalizing on it, then maybe the answers we’re looking for just aren’t able to exist in the places we’re looking.

SR: I am truly grateful to have this conversation with two women who are woke and who I can trust. Please know I appreciate that you are rare human beings. Most people I wouldn’t even broach this conversation with.

Two things come to mind in response to Chloë’s suggestion of responsibility beginning with the self, and her question as to why we continue to rely on consistently disappointing institutions. The first is: I disagree. I think responsibility precedes me. I enter into a culture where a set of politics already exists that encourages most people (even those who look like me) to dehumanize each other, to mistake each other for the sign of something else. I know that I am responsible for wringing whatever joy I can from the fruits I can reach, but damned if the orchard isn’t structured to make it hard to get to them.

The second is that I think we still need institutions, especially civic ones, because they allow private experience to rub up against public judgment. That’s how we lead lives where we are not so alone, either ensconced in the semi-private enclaves of the family or the culture of the place of employment. Civic space is crucial to allow us to grow.

Jillian’s suggestion (which was made by an audience member on Sunday as well) that the arts community think about dealing with perpetrators of violence rather than its victims is a good one. It’s about time we start doing that. Chloë might be suggesting that we form new institutions, ones that are responsive and meaningfully accountable — which is also a worthy goal, though I find that somewhat entrepreneurial spirit to not be where I am right now.

Right now, I don’t want to rush off to try to make it better. Right now I just want to sit with an acknowledgment of our failures and look at them, really look at them, and then perhaps be able to understand them.

JS: Seph, I admire your patience. Chloë, I admire your readiness to take yourself to task. I could stand to improve in both of those areas. I do agree with Seph that we need institutions, for better or for worse — and I think I see it as both: I believe in personal responsibility, but I also think holding institutions accountable is a key part of that. It’s important for me to work to understand my own shortcomings, failures, whiteness, privilege, but it’s equally important for me to take what I learn in that process and extend it out into the world. Sometimes I think I’m being hopelessly mainstream and naïve when I continually insist that we must work to challenge the system; other times I think it’s the only real shot we have. It’s interesting to note, in relation to this event, that Claudia Rankine did decide to start her own, alternative institution — the Racial Imaginary Institute — but for her first event, she chose to collaborate with a pre-existing institution, the Whitney Museum. That collaboration may have resulted in an event that was less incisive, less rigorous than it could have been without the Whitney’s involvement. But one could also argue that it was important to have such an event at the Whitney, because it gave the critiques leveled there (especially those against the museum itself) added weight.

Black Women Artists for Black Lives Matter at the New Museum (photo by Madeleine Hunt Ehrlich)

Chloë, when you mentioned Black joy, I immediately thought of the Black Women Artists for Black Lives Matter event at the New Museum last year. Seeing a white institutional space given over to Black joy left a deep, lasting impression and really opened up a space of imagination within me. It seems relevant to note that the event came about because the artist Simone Leigh, who had her own show at the New Museum, took the initiative of proposing it — she was willing to cede some of her personal limelight to a larger cause. Maybe that’s the place where personal responsibility intersects with the institutional. An artist must think about not just what they paint, but also the ethical implications of how they interact with the world. (This is perhaps why I loved Ajay Kurian’s contribution on Sunday night — he’s an artist in the Whitney Biennial who is not afraid to criticize the show or the institution that’s hosting him.) In doing so, they may be able to think more imaginatively about the possibilities of that interaction.

I keep thinking that it feels unfair to lay all of this at the feet of individual artists (and writers, curators, etc). At the end of the day, we’re all trying to make a creative living (which is next to impossible) within the confines of the system we’ve been given. But the problem, of course, is that the system will never imagine anything beyond itself — and the system is, ultimately, comprised of people. So maybe the ideas that this comes down to personal vs. institutional responsibility are not actually opposed — maybe they’re one and the same … or at least, they’re related.

CB: One of the speakers last Sunday mentioned not confusing David with Goliath. That is essential here as well. While I think the format of institutional responsibility and personal responsibility can (or should?) be the same, the former is a greater, more aggregated, and more powerful form of the latter. The scales are not comparable.

I also just want to say, as we close out, that I appreciate very much that we’re not in total agreement. That feels important to me. I want to provide and be a part of more atmospheres where nuanced non-agreement can take place. For me, that celebration of the potential of real imagination, and the resulting dialogue, is the most important step towards any true change.

JS: Agreed wholeheartedly — I think a lot of the Schutz fallout has been the product of non-nuanced non-agreement, to use a double negative. I keep finding myself unsatisfied with such an inconclusive ending to our conversation, but it probably helps to remember that we are only three of the many people who’ve had and will continue to have it. If these questions were resolved, we wouldn’t need to keep asking them.

SR: Yes. I’m with both of you in spirit and in truth. We don’t need to fully agree — as long as we can create collaborations of productive tension (institutions might want to consider this, if they haven’t yet). In this season of real, demonstrable threat to our imaginations and lives, it feels right to end this conversation inconclusively but with the conviction that we are going to argue while still holding each other’s hands.

The 2017 Whitney Biennial continues at the Whitney Museum of American Art (99 Gansevoort Street, Meatpacking District, Manhattan) through June 11.

The post The Possibilities and Failures of the Racial Imagination appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2pw5uHt

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: “What Does It Mean to Be Black and Look at This?” A Scholar Reflects on the Dana Schutz Controversy

At the Whitney, a protest against Dana Schutz' painting of Emmett Till: "She has nothing to say to the Black community about Black trauma." http://pic.twitter.com/C6x1JcbwRa

— Scott W. H. Young (@hei_scott) March 17, 2017

“Open Casket,” a painting by Dana Schutz on view in this year’s Whitney Biennial, is derived from a photograph of the mangled body of Emmett Till in its casket in 1955, after white men in Mississippi tortured and murdered the 12-year-old boy from Chicago. Since the exhibition opened a week ago, the work has sparked furious debate. Protesters have stood vigil, partly obscuring its view. Artist Hannah Black wrote an open letter, signed by dozens of others, demanding not only its removal but also its destruction. Schutz, who is white, has defended the work, and the biennial’s curators, Christopher Y. Lew and Mia Locks, have called its inclusion consistent with the show’s search for “empathetic connections in an especially divisive time.” They added: “By exhibiting the painting we wanted to acknowledge the importance of this extremely consequential and solemn image in American and African American history and the history of race relations in this country.”