#Father of the Soviet Symphony

Text

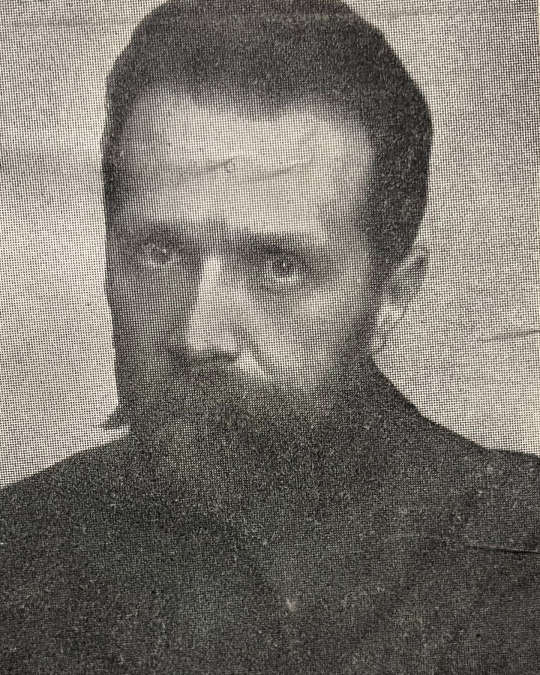

OTD in Music History: Russian-Soviet composer Nikolai Myaskovsky (1881 - 1950) is born near Modlin Fortress (present-day Poland) in what was then the Russian Empire.

Sometimes referred to as the "Father of the Soviet Symphony,” Myaskosvky was highly acclaimed in his own day. While he was awarded the Soviet Union’s highest honor – the “Stalin Prize” – five times, however, Myaskovsky always remained a rather distant and enigmatic figure. Fundamentally a conservative artist, Myaskovsky nevertheless enjoyed flirting with “modernism” from time to time; possessed of a markedly individualistic spirit, he flourished even within the decidedly collectivist atmosphere of the Stalin-Era Soviet Union.

After enrolling at the St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1906 (at the age of 25), Myaskovsky studied with Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844 - 1908) and Anatol Lyadov (1855 – 1914) and befriended the young Sergei Prokofiev (1891 - 1953), who was ten years his junior. In his third year at the Conservatory, Myaskovsky composed his Symphony No. 1 – which won him a scholarship that paid for the remainder of his schooling. After graduating in 1911, he initially supported himself by teaching private lessons before eventually securing a position at the Moscow Conservatory.

Myaskovsky rose to international prominence as a composer in the mid-1920s, and throughout the 1930s-40s he continued to churn out a long series of symphonies, piano sonatas, and string quartets. He also notably taught both Aram Khachaturian (1903 - 1978) and Dmitri Kabalevsky (1904 - 1987).

PICTURED: A small photo showing the middle-aged Myaskovsky, which he signed and dated in Moscow in 1936.

#Nikolai Myaskovsky#Myaskovsky#Mikołaj Miąskowski#classical music#music history#classical composer#composer#Father of the Soviet Symphony#classical musician#musician#music#symphony#orchestra#symphonic poem#Overture#Violin Concerto#Concerto#Concert#Dramatic Overture#Cello Concerto#Choral music#Cantata#Nocturne#Sonata#Chamber music#Piano music#Songs

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ivan Sollertinsky (Research so far)

Ivan Ivanovich Sollertinsky, born December 3rd 1902, Vitebsk, Belarus, was a Soviet Polymath. Sollertinsky was an expert in theatre and languages but he is best known for his musical accomplishments: work in music field as a critic and musicologist. He was a professor at the Leningrad Conservatory and the Artistic director of the Leningrad Philharmonic. During these times he was an enthusiast and advocated Mahler’s music in the USSR. Sollertinsky had exceptional memory according to his coetaneous’; he was able to speak 32 languages, some of which were dialects.

After moving from Vitebsk to Leningrad, he graduated from Leningrad University with a degree in Romano-Germanic philology. In 1927, he became close friends with Shostakovich, and is known for introducing him to the works of Mahler that greatly impacted his style of composing and some of his compositions. Examples being his opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk and his 4th symphony. Shostakovich wrote letters to Sollertinsky; letters date from early 1927- the 4 few days following Sollertinsky’s premature death in Novosibirsk.

In 1936, Shostakovich faced his first denunciation for the opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk. Pravda launched a series of attacks calling it “Muddle instead of Music.” Sollertinsky greatly supported the opera and even wrote that it was an “enormous contribution to Soviet musical culture” in 1934 for a review in “Workers and Theatres”. However, in Pravda, he was termed as “The troubadour of formalism”. After the denunciation, criticism grew on the opera which resulted in accumulating pressure on Sollertinsky to withdraw his previous statements. However, he did not do so until Shostakovich told him to, fearing for the safety of Sollertinsky.

Sollertinsky contracted diphtheria in 1938 which temporarily paralysed his arms, legs and jaw. During this time, he married his third wife Olga Pantaleimonovna. He fathered a son with her, whom he named Dmitri Ivanovich, after Shostakovich: this broke the generation-long tradition where the son would have their first name as Ivan. During the 4 months in which he was hospitalised, Sollertinsky studied Hungarian.

Soon after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, Sollertinsky evacuated from Leningrad to Novosibirsk. In Novosibirsk, he engaged himself in a number of creative works, give lectures and speeches and to attend other cultural/artistic events. Even though him and Shostakovich didn’t see each other frequently during the war years, the Soviet composer, Vissarion Shebalin arranged for Sollertinsky to teach a course of music history at Moscow Conservatory. This was where Shostakovich was living at the time. Sollertinsky stayed in Moscow briefly to give a speech upon the death of Tchaikovsky in 1934. After, he moved back to Novosibirsk in the same year, there he gave a speech upon the premiere of Shostakovich’s Eighth Symphony. This would be the last speech he would give before his death.

Doubts over the cause of Sollertinsky’s death persist to this day: according to a Wikipedia article, “On the night of February 10, 1944, Sollertinsky, feeling unwell, stayed at the house of the conductor A.P. Novikov. He died in his sleep at the age of 41”. The Russian newspapers say he died of a heart illness but rumours spoke of his having been murdered by the NKVD. Shostakovich expressed a heartfelt and touching message portraying his feelings for his dear friend:

“I cannot express in words all the grief I felt when I received the news of the death of Ivan Ivanovich. Ivan Ivanovich was my closest and dearest friend. I owe all my education to him. It will be unbelievably hard for me to live without him.”

Shostakovich dedicated his Second Piano Trio to the memory of Sollertinsky. He started this in 1943 and completed it within the following year in August. It was premiered on 14th November 1944. Sollertinsky’s death greatly impacted Shostakovich, he struggled with composing and fell into depression in the following months. One time the composer said that “It seems to me that I will never be able to compose another note again.” He was awarded the Stalin prize for the trio.

The relationship between Shostakovich and Sollertinsky was exceptional and heart warming. The two were inseparable and were always there for each other in times of need and to comfort one another. Sollertinsky was indeed an important and influential aspect of Shostakovich’s life.

-Sources: DCSH Journal, Wikipedia

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tumblr's Guide to Shostakovich: part 3- Artistic Beginnings, Ideological Formation, and the Conservatory Years

Hello and welcome back to Tumblr's Guide to Shostakovich, the weekly series where I discuss the life of Soviet composer Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich! In this installment, I'll be talking about events throughout Shostakovich's adolescence, including his family hardships, his time at the conservatory, and his First Symphony. The sources I'll be drawing from are Pauline Fairclough's Critical Lives: Dmitri Shostakovich, Elizabeth Wilson's Shostakovich: A Life Remembered, Laurel Fay's Shostakovich: A Life, and various articles of correspondence posted on the DSCH Publishers website, where I will also be sourcing much of my photographs.

At the age of thirteen, in 1919, Shostakovich left a general education at the School of Labour no. 108 to study music at the Petrograd Conservatory, directed by Aleksandr Glazunov, himself a famous composer in his own right (and friend of the late Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky). Shostakovich studied composition under composer Maximillian Osseyevich Steinberg, and wrote his first numbered works, such as the Scherzo in F# Minor (Op. 1) and the Three Fantastic Dances (Op. 5). Shostakovich was an eager student who took inspiration from many contemporary composers of the time; while his early student works show traces of Tchaikovsky and even some Debussy, his later inspirations would include Bartok, Stravinsky, Hindemith, and Schoenberg, although he was also frequently influenced by Mussorgsky. His musical talents were noticed by his classmates and teachers, as this anecdote from Valerian Bogdanov-Berezovsky, his friend and classmate states:

"Shostakovich undoubtedly outstripped everyone in this art [music], as well as in aural dictation. One could already compare his hearing in its refinement and precision to a perfect acoustical mechanism (which he later was to develop still further), and his musical memory created the impression of an apparatus which made a photographic record of everything he heard."

Shostakovich (top left) with Steinberg's (center) composition class, 1920s.

Hardship would rock the Shostakovich family when, in 1922, Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich, the composer's father and main breadwinner of the family, died of pneumonia. Shostakovich would write his Suite for Two Pianos (Op. 6) in his father's memory, the first of many pieces he would write that would bear dedications to deceased loved ones. It was premiered by Shostakovich and his sister, Mariya.

After the death of her husband, Sofiya Vasiliyevna worked a variety of low-paying jobs, while her children also sought work to help support the family, with Mariya teaching piano lessons and Mitya finding work as a cinema pianist for silent film theaters. Shostakovich worked at three cinemas during this period- the Bright Reel, Splended Palace, and Piccadilly Theater. He resented cinema work; the pay was low, the managers dishonest, and his creative abilities stifled by both the insipid music he was required to play and the work taking time from his studies. (Reportedly, he was once thought to be drunk while attempting to imitate bird noises on the piano to accompany a film called Water Birds of Sweden. Amusingly, scholar Laurel Fay notes that "far from being stung by the criticism, Shostakovich expressed his pride in having distracted their attention from the film.") However, as much as Shostakovich hated cinema work, it provided him with stylistic inspiration, as shown in his Piano Trio no. 1 (Op. 8), as well as the opera and film scores he would write later on in his career.

While he worked tirelessly to support himself and his family, after the death of his father, a toll was being taken on Shostakovich's physical health. His godmother, Klavdia Lukashevich, noted that Shostakovich was given a "talented" ration" by the conservatory consisting of of "two spoons of sugar and half a pound of pork every fortnight," although this was not enough to sustain him. While Glazunov, reserving high hopes for his student, provided him with a stipend, a group of students had attempted to have it suspended. Likely due to malnutrition, in 1923, Shostakovich fell ill with tuberculosis and was sent to a sanatorium in the Crimea to recover. (He also met his first girlfriend and the dedicatee of Trio no. 1, Tatiana Glivenko, there, but the hot mess that relationship turned out to be deserves its own post.)

Maximillian Steinberg, Shostakovich's composition teacher.

In the wider political and social sphere, Shostakovich would gain both musical and ideological influences due to the advent of Lenin's New Economic Policy (NEP), a response to the failed economic policies of the Russian Civil War (1917-1923). The NEP, introduced in 1921 and later dissolved by Stalin in 1928, included a small capitalist sector to the economy, which was intended to be gradually phased out in a less aggressive approach to communism. While this period was far from utopian- censorship, corrupt business practices, and political unrest still abounded- the economic relief that the NEP provided led to a period of social progressivism that would later be reversed by the 1930s. During the NEP era, a wave of social reforms took place- in the sphere of sexuality and relationships, abortion and homosexuality were decriminalized, divorce was made easier (although this led to an increase in broken families, as men often readily divorced their wives after impregnating them), and "free love" movements took place. Meanwhile, in terms of social issues, the "Indigenization" movement sought to uplift the cultures of ethnic minorities in the Soviet Union (although it should be said this movement put Jews in a bizarre position; the banning of religion meant that while synagogues were desecrated and the Hebrew language banned, other aspects of Soviet Jewish culture, like Klezmer music, were promoted), and feminist ideals largely took hold, most notably spread by activists like Aleksandra Kollontai. And in the arts, the NEP resulted in a variety of works that blended avant-garde experimentation (also popular in the west at the time) with newly-forming Soviet ideals, such as Mayakovsky's play The Bedbug (which Shostakovich provided music for), Vsevolod Meyerhold's theatrical productions, and Aleksandr Mosolov's futurist musical compositions, most notably Iron Foundry. As Shostakovich worked with many artists of the NEP era and artistically "came of age" around this time, both social and artistic ideas would find a permanent place in his life and work, most notably the feminist themes of Lady Macbeth, his liberal attitudes towards sex and marriage (he himself would later enter an open marriage), and the avant-garde and oftentimes grotesque techniques he would employ in his music. A letter to his mother from his stay in the Crimea in 1923 highlights many of these views:

If, for instance, a wife stops loving her husband and gives herself to another man she has fallen in love with and in spite of social prejudice they start living together, there is nothing wrong about that. On the contrary, it’s even good that Love should be really free. Vows made in front of the altar [...] are the most terrible part of religion. Love cannot last for a long time. The best thing one could imagine is the complete abolition of marriage, namely of all the chains and duties that accompany love. This of course is a Utopia. If there is no marriage, there will be no family. That of course, would be very bad. One thing can be said for certain though - love is not free. Mamma dear, I must warn you that if I do fall in love one day I may well not try to tie myself down through marriage. Yet if I do marry and my wife falls in love with someone else, I shall not say pure word. If she wants a divorce, I shall give it to her and take the blame on myself. [...] Yet at the same time, there is the noble vocation of parenthood. When you start thinking about all this, your head is ready to explode. In any case, Love should be free!

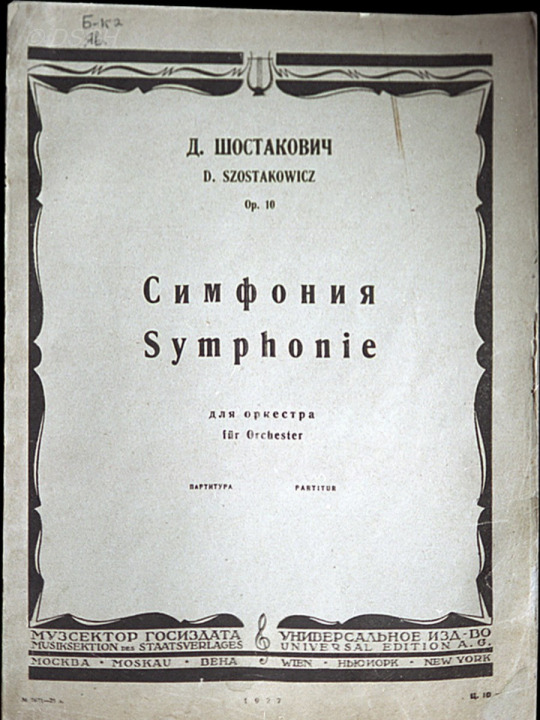

In 1925, Shostakovich completed his First Symphony at the age of nineteen, as his graduation piece. It was premiered by his teacher, the conductor Nikolai Malko, who Shostakovich regarded as a "rather ungifted person" (his early letters show no small amount of arrogance!), but Malko nonetheless found the symphony impressive. It was premiered on May 12th, 1926, and received a largely positive reception that would cement Shostakovich as a promising composer, receiving praise from the likes of not only Soviet musicians, but prominent western ones such as Bruno Walter. While many accounts detail nothing but praise on the event of the symphony's premiere, Shostakovich held a much different opinion, detailing in lengthy letters to both his mother and his friend, Boleslav Yavorsky, the poor acoustics of the venue, blunders on behalf of the musicians, and even a nearby dog drowning out the music with a prolonged barking session. Despite how mortified he was at what he perceived to be the premiere's failure, Shostakovich would celebrate its anniversary for the rest of his life, later considering it his "second birth."

A first-edition score of Shostakovich's First Symphony. 1927.

Thank you for reading! In the next entries, I'll cover some events in Shostakovich's personal life and his operas The Nose and Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District- as well as the consequences that would follow.

#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#tumblr's guide to shostakovich#composer#classical music#music history#russian history#soviet history#music#classical music history

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

film reviews: War and Peace (1966-7)

In the 1960s Mosfilm adapted Leo Tolstoy’s sweeping epic novel War and Peace into a four-part feature film series, directed by Sergei Bondarchuk and released throughout 1966-67. The films together comprise roughly seven hours of screentime, allowing the gargantuan novel time to unfold in full without being condensed or rushed (much). As Soviet films are, at least those that get known in the West, frequently of high cinematic and storytelling quality, I had high hopes for this film series, and I was not disappointed. The films are gorgeously shot, like a symphony of sight and sound, as all of them have at least one musical number, and several classical music pastiches in the soundtrack, which adds an entertaining dramatic element to this tale about human beings. The production values are immense, with the films costing 60-70 million USD in today’s money to produce, and featuring thousands of extras in the military scenes. The Russian government financed the films, and the Russian military lent over ten thousand personnel for the battle scenes and hundreds of horses, and the films are great spectacle, yet also intelligent and philosophically deep, which is a very rare combination in cinema.

I have not read the original novel, so I don’t know how closely the films follow the plot, but the films are critically well-regarded and I believe they are mostly faithful to the novel, although certain sections were excised or condensed. The dialogue is always intelligent, and often poetic and philosophical, in Soviet cinema tradition, which is wonderfully intellectually stimulating, and I enjoyed it immensely. In one scene in the second film, the character Natasha Rostov is pining for her fiancee, who hasn’t visited her in a while, and she muses to herself “If only he would come soon, I’m afraid he never will! The worst of it is I’m growing old. I’ll lose my charm. Perhaps he’ll come today, this very minute! Perhaps he came yesterday, and I’ve simply forgotten.” War and Peace is great cinema, grand cinema of the highest degree, and I heartily recommend watching it.

The four films are on YouTube in full for free, on the Mosfilm official YouTube channel, which has dozens of Soviet films available for watching.

War and Peace, Part One

War and Peace, Part Two

War and Peace, Part Three

War and Peace, Part Four

Plot overviews of the four films beneath the cut:

Part One covers 1805, and introduces the main characters of the story, including Pierre, a feckless but goodhearted man and illegitimate son of a count who unexpectedly inherits his father’s fortune after he disowns his legitimate sons. Pierre is friends with Prince Andrei Volkonsky, a nobleman who acts as mentor and philosophical sparring partner, who departs Russia to fight in the Napoleonic wars, leaving his pregnant young wife in the care of his own father. After Pierre becomes rich and thus socially desirable, he is encouraged to marry a beautiful woman named Helene Kuragin by mutual acquaintances, but they are ill-matched and Helene grows bored and becomes unfaithful to him, becoming lovers with a man named Dolokhov, whom Pierre later challenges to a duel, and wounds but does not kill, after being publicly humiliated by him at a party. Also introduced is Natasha, an intelligent, playful child and daughter of the noble Rostov family, who enjoys a charmed family life full of music and dancing.

Part Two covers 1807-1812, and concerns the emotional maturation of Natasha Rostov, who is proposed to by Andrei Volkonsky when she is 15 after they dance at a ball. Volkonsky realizes she is too young to become a wife and insists they wait a year before marrying and not make the engagement public, leaving her socially free to back out of the engagement if she later changes her mind about him, knowing that she still has some maturing to do. Volkonsky tells Natasha that, if she ever finds herself in need, to turn to his friend Pierre for help, who is a goodhearted man. Natasha feels abandoned, and later falls in love with Helene Kuragin’s brother, who seduces her at a party and tries to elope with her, despite already being married to another. Pierre appears little in this film.

Part Three centers on the Battle of Borodino, a prelude to the burning of Moscow during the Napoleonic War of 1812. 100,000 Russians meet 100,000 French on the battlefield, resulting in carnage and heavy losses on both sides. The French won the battle but it was Pyrrhic victory, and the film claims that the Russians won a moral victory over the battle. The film is an hour and twenty minutes of nonstop battle scenes, but it’s quickly paced and doesn’t drag in the least. I’m not interested in war films but I remained interested throughout the film and watched without boredom.

Part 4 concerns the burning of Moscow and its aftermath. Volkonsky is among the wounded soldiers evacuated from Moscow, and ends up in the Rostovs’ carriage by coincidence, leading to an emotional reunion between Andrei and Natasha. After witnessing the destruction of Moscow, Pierre tries to get an audience with Napoleon to assassinate him but is arrested and nearly executed, but instead becomes a prisoner for months during the French retreat through Russia, and braves the winter in peasant’s clothes, before finally being rescued by Russian partisans. The French army, defeated by starvation and disease, abandons its campaign against Russia and retreats, with soldiers dropping like flies on the long march through the winter. A band of bedraggled French soldiers happens upon a contingent of Russian soldiers, who take pity and feed the French, who gratefully teach them the French royalist tune Vivre Henri VI in repayment. This fourth film drags toward the end, and offers a bleak end for several of the characters, but offers a neat ending to the story, although I feel it’s the weakest of the four films.

#film reviews#film recs#movie reviews#movie recs#films#movies#cinema#Soviet cinema#War and Peace#Soviet films#personal

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 4.7

451 – Attila the Hun captures Metz in France, killing most of its inhabitants and burning the town.

529 – First Corpus Juris Civilis, a fundamental work in jurisprudence, is issued by Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian I.

1141 – Empress Matilda becomes the first female ruler of England, adopting the title "Lady of the English".

1348 – Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV charters Prague University.

1449 – Felix V abdicates his claim to the papacy, ending the reign of the final Antipope.

1521 – Ferdinand Magellan arrives at Cebu.

1541 – Francis Xavier leaves Lisbon on a mission to the Portuguese East Indies.

1724 – Premiere performance of Johann Sebastian Bach's St John Passion, BWV 245, at St. Nicholas Church, Leipzig.

1767 – End of Burmese–Siamese War (1765–67).

1788 – Settlers establish Marietta, Ohio, the first permanent settlement created by U.S. citizens in the recently organized Northwest Territory.

1795 – The French First Republic adopts the kilogram and gram as its primary unit of mass.

1790 – Greek War of Independence: Greek revolutionary Lambros Katsonis loses three of his ships in the Battle of Andros.

1798 – The Mississippi Territory is organized from disputed territory claimed by both the United States and the Spanish Empire. It is expanded in 1804 and again in 1812.

1805 – Lewis and Clark Expedition: The Corps of Discovery breaks camp among the Mandan tribe and resumes its journey West along the Missouri River.

1805 – German composer Ludwig van Beethoven premieres his Third Symphony, at the Theater an der Wien in Vienna.

1831 – Pedro II becomes Emperor of Empire of Brazil.

1862 – American Civil War: The Union's Army of the Tennessee and the Army of the Ohio defeat the Confederate Army of Mississippi near Shiloh, Tennessee.

1868 – Thomas D'Arcy McGee, one of the Canadian Fathers of Confederation, is assassinated by a Fenian activist.

1906 – Mount Vesuvius erupts and devastates Naples.

1906 – The Algeciras Conference gives France and Spain control over Morocco.

1922 – Teapot Dome scandal: United States Secretary of the Interior Albert B. Fall leases federal petroleum reserves to private oil companies on excessively generous terms.

1926 – Violet Gibson attempts to assassinate Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini.

1927 – AT&T engineer Herbert Ives transmits the first long-distance public television broadcast (from Washington, D.C., to New York City, displaying the image of Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover).

1933 – Prohibition in the United States is repealed for beer of no more than 3.2% alcohol by weight, eight months before the ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment to the United States Constitution. (Now celebrated as National Beer Day in the United States.)

1933 – Nazi Germany issues the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service banning Jews and political dissidents from civil service posts.

1939 – Benito Mussolini declares an Italian protectorate over Albania and forces King Zog I into exile.

1940 – Booker T. Washington becomes the first African American to be depicted on a United States postage stamp.

1943 – The Holocaust in Ukraine: In Terebovlia, Germans order 1,100 Jews to undress and march through the city to the nearby village of Plebanivka, where they are shot and buried in ditches.

1943 – Ioannis Rallis becomes collaborationist Prime Minister of Greece during the Axis Occupation.

1943 – The National Football League makes helmets mandatory.

1945 – World War II: The Imperial Japanese Navy battleship Yamato, one of the two largest ever constructed, is sunk by United States Navy aircraft during Operation Ten-Go.

1946 – The Soviet Union annexes East Prussia as the Kaliningrad Oblast of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.

1948 – The World Health Organization is established by the United Nations.

1954 – United States President Dwight D. Eisenhower gives his "domino theory" speech during a news conference.

1955 – Winston Churchill resigns as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom amid indications of failing health.

1956 – Francoist Spain agrees to surrender its protectorate in Morocco.

1964 – IBM announces the System/360.

1965 – Representatives of the National Congress of American Indians testify before members of the US Senate in Washington, D.C. against the termination of the Colville tribe.

1968 – Two-time Formula One British World Champion Jim Clark dies in an accident during a Formula Two race in Hockenheim.

1969 – The Internet's symbolic birth date: Publication of RFC 1.

1971 – Vietnam War: President Richard Nixon announces his decision to quicken the pace of Vietnamization.

1972 – Vietnam War: Communist forces overrun the South Vietnamese town of Loc Ninh.

1976 – Member of Parliament and suspected spy John Stonehouse resigns from the Labour Party after being arrested for faking his own death.

1977 – German Federal prosecutor Siegfried Buback and his driver are shot by two Red Army Faction members while waiting at a red light.

1978 – Development of the neutron bomb is canceled by President Jimmy Carter.

1980 – During the Iran hostage crisis, the United States severs relations with Iran.

1982 – Iranian Foreign Affairs Minister Sadegh Ghotbzadeh is arrested.

1983 – During STS-6, astronauts Story Musgrave and Don Peterson perform the first Space Shuttle spacewalk.

1988 – Soviet Defense Minister Dmitry Yazov orders the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan.

1989 – Soviet submarine Komsomolets sinks in the Barents Sea off the coast of Norway, killing 42 sailors.

1990 – A fire breaks out on the passenger ferry Scandinavian Star, killing 159 people.

1990 – John Poindexter is convicted for his role in the Iran–Contra affair.[25] In 1991 the convictions are reversed on appeal.

1994 – Rwandan genocide: Massacres of Tutsis begin in Kigali, Rwanda, and soldiers kill the civilian Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana.

1994 – Auburn Calloway attempts to destroy Federal Express Flight 705 in order to allow his family to benefit from his life insurance policy.

1995 – First Chechen War: Russian paramilitary troops begin a massacre of civilians in Samashki, Chechnya.

1999 – Turkish Airlines Flight 5904 crashes near Ceyhan in southern Turkey, killing six people.

2001 – NASA launches the 2001 Mars Odyssey orbiter.

2003 – Iraq War: U.S. troops capture Baghdad; Saddam Hussein's Ba'athist regime falls two days later.

2009 – Former Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori is sentenced to 25 years in prison for ordering killings and kidnappings by security forces.

2009 – Mass protests begin across Moldova under the belief that results from the parliamentary election are fraudulent.

2011 – The Israel Defense Forces use their Iron Dome missile system to successfully intercept a BM-21 Grad launched from Gaza, marking the first short-range missile intercept ever.

2017 – A man deliberately drives a hijacked truck into a crowd of people in Stockholm, Sweden, killing five people and injuring fifteen others.

2017 – U.S. President Donald Trump orders the 2017 Shayrat missile strike against Syria in retaliation for the Khan Shaykhun chemical attack.

2018 – Former Brazilian president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, is arrested for corruption by determination of Judge Sérgio Moro, from the “Car-Wash Operation”. Lula stayed imprisoned for 580 days, after being released by the Brazilian Supreme Court.

2018 – Syria launches the Douma chemical attack during the Eastern Ghouta offensive of the Syrian Civil War.

2020 – COVID-19 pandemic: China ends its lockdown in Wuhan.

2020 – COVID-19 pandemic: Acting Secretary of the Navy Thomas Modly resigns for his handling of the COVID-19 pandemic on USS Theodore Roosevelt and the dismissal of Brett Crozier.

2021 – COVID-19 pandemic: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announces that the SARS-CoV-2 Alpha variant has become the dominant strain of COVID-19 in the United States.

2022 – Ketanji Brown Jackson is confirmed for the Supreme Court of the United States, becoming the first black female justice.

1 note

·

View note

Text

History

March 31

March 31, 1933 - The Civilian Conservation Corps, the CCC, was founded. Unemployed men and youths were organized into quasi-military formations and worked outdoors in national parks and forests.

March 31, 1968 - President Lyndon Johnson made a surprise announcement that he would not seek re-election as a result of the Vietnam conflict.

March 31, 1991 - The Soviet Republic of Georgia, birthplace of Josef Stalin, voted to declare its independence from Soviet Russia, after similar votes by Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia. Following the vote in Georgia, Russian troops were dispatched from Moscow under a state of emergency.

Birthday - Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) was born in Rohrau, Austria. Considered the father of the symphony and the string quartet, his works include 107 symphonies, 50 divertimenti, 84 string quartets, 58 piano sonatas, and 13 masses. Based in Vienna, Mozart was his friend and Beethoven was a pupil.

Birthday - Boxing champion Jack Johnson (1878-1946) was born in Galveston, Texas. He was the first African American to win the heavyweight boxing title.

0 notes

Text

'“Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to man. For this he was chained to a rock and tortured for eternity”. In the very first moments of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, these words fade slowly onto the screen, against a searing backdrop of gargantuan flames and the seat-shaking echoes of a nuclear explosion. The Promethean story is certainly a neat cultural shorthand for the darker side of human ingenuity embodied in the figure of J. Robert Oppenheimer, that age-old question of whether, even in the event that we can do something, it need always follow that we should do it.

But, it also bears remembering – before Prometheus brought fire, he also bestowed upon man the very gift of life itself. Fitting, then, that Oppenheimer is itself a creation myth, a nightmarish premonition of the so-called ‘American century’, in all its destructive potential. “What they need to understand”, one character warns, “is that we’re not just creating a new weapon. We’re creating a new world”. That new world may not be a pretty one, and Oppenheimer is certainly far from a pretty film – but, if one thing’s for certain, it’s that this is Christopher Nolan operating at the absolute height of his powers.

Cillian Murphy stars as the titular nuclear physicist, the self-proclaimed ‘destroyer of worlds’ destined to be remembered by history as the ‘father of the atomic bomb’. Although its imposingly dense literary source material (all of 721 pages, courtesy of historians Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin) tracks Oppenheimer’s entire life, the film opts to focus mainly upon a snapshot of his most crucial years; his role as director of the Manhattan Project, which culminated in the decimation of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, and his subsequent blacklisting the following decade by the Eisenhower administration, for suspected Soviet sympathies.

In characteristic achronological style (Oppenheimer’s subjective experiences are shot in colour, whilst an ‘objective’ retelling of certain events is imagined in a noirish monochrome), Nolan reckons with one of the twentieth century’s most bitterly contested personal legacies with a clear-eyed confidence and careful attention to detail that can’t help but feel like the glorious culmination of his directorial career up until this point. All the expected technical wizardry is on display; but, unlike Nolan’s weakest work (see the endlessly ambitious and equally frustrating Tenet), it’s consistently in service of some of his most gripping and formidably cinematic storytelling.

Regular Nolan collaborator, cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema lends a bleak vastness to the desert landscapes of Los Alamos, whilst editor Jennifer Tame manages to inject into Senate hearings and physics lectures a sense of nail-biting tension to rival any action sequence. Both are aided by Ludwig Göransson’s magnificent score, an anxious series of electronic fits and bursts, pulsing amidst a symphony of agonised strings.

All this makes for a viewing experience that feels suitably cosmic – but it’s also paired with a striking sense of intimacy, as Nolan’s starry ensemble collectively unearth the personal stories that lie behind the politics. Florence Pugh and Emily Blunt deliver performances of quiet frustration as Oppenheimer’s young lover and wife respectively, and Robert Downey Jr. is given a long-overdue opportunity to showcase his dramatic chops in a brilliant turn as the calculating chair of the Atomic Energy Commission, Lewis Strauss. But, it’s Murphy who impresses most, in what is undoubtedly the performance of his career; his Oppenheimer is a figure of wiry unease, his piercing blue eyes at once alight with the thrill of new discovery and, it seems, hauntingly cognizant of the devastating human cost of his own genius.

Although Jewish by birth, Oppenheimer had a well-documented fascination with mystical religions; indeed, many of the film’s most trenchant sequences are imbued with a strange sense of paranormality. Oppenheimer addresses a jingoistic crowd of his employees, as they celebrate the success of the ‘Trinity’ test, the bomb’s first detonation; but before too long, the walls around him begin to quake. The triumphant rhythms of his audience’s stomping feet start to imitate the ominous rumblings of a distant eruption. A man walks by outside, vomit streaming from his lips. One too many celebratory glasses of champagne, perhaps? Or, worse still, a body as poisoned with nuclear radiation as Oppenheimer’s mind seems to be by his own guilt?

The jury’s out on quite to what extent the real Oppenheimer may have come to regret his most famous accomplishment. Certainly, in Nolan’s version of events, the remorse could hardly be more palpable, compounded by the physicist’s subsequent inability to control how his research would go on to be used and built upon, to ever more ruinous effects (“No one cares about who created the bomb”, he’s told by the powers that be, “They care about who drops it”). Is this Nolan’s parable of American exceptionalism? Hardly– when all’s said and done, Oppenheimer plays far more like a tragedy.'

#Oppenheimer#Christopher Nolan#Cillian Murphy#Kai Bird#Martin J. Sherwin#Florence Pugh#Emily Blunt#Robert Downey Jr.#Lewis Strauss#Kitty#Jean Tatlock#Hoyte van Hoytema#Ludwig Goransson#Jennifer Lame

1 note

·

View note

Text

Shostakovich, Piano Concerto No. 2 (complete) for solo piano (sheet music, Noten)

Shostakovich, Piano Concerto No. 2 (complete) for solo piano (sheet music, Noten)

ShostakovichOrigins and early years

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.Beginning of his career

Please, subscribe to our Library. Thank you!

Shostakovich, Piano Concerto No. 2 (complete) for solo piano (sheet music, Noten)

https://rumble.com/embed/v2n4p04/?pub=14hjof

Shostakovich

Origins and early years

Dmitri Shostakovich (Russian: Дми́трий Дми́триевич Шостако́вич) ( Saint Petersburg , September 12 , 1906 (Julia) - Moscow , August 9 , 1975 ), full name with patronymic Dmitri Dmitrievitch Shostakovich , was a composer and pianist Russian of the Soviet period .

He started on the piano of his mother's hand.

Later, from 1919 to 1925, he studied piano and composition at the Petrograd Conservatory.

He composed his first symphony in 1925, premiered on May 5, 1926 in Berlin .

The Soviet government of the time commissioned the second symphony for the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution .

From 1925 to 1935 he wrote several avant-garde compositions. His operas El Nas in 1930 and Ledi Màkbet Mtsènskogo Uiezda in 1934 stood out. The latter caused a scandal in New York City and strong criticism from the Stalinist government, which banned it.

Over time, Shostakovich regained favor with the Soviet government, notably with his Fifth Symphony in 1937.

During World War II he wrote about the heroism of the Soviet people. His seventh symphony was written during the siege of Leningrad .

After the war, from 1948, he suffered the persecution of Andrei Zhdanov and could not write freely until the death of Stalin in 1953.

He died on August 9, 1975, leaving a legacy of fifteen symphonies, fifteen concertos, two operas, three dozen film pieces and many works of chamber music, including fifteen string quartets, and many others minor works and songs.

Born on Podolskaya Street in Saint Petersburg ( Russian Empire ), Shostakovich was the second of three children of Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich and Sofiya Vasílievna Kokoúlina. Shostakovich's paternal grandfather, originally surnamed Szostakowicz, was of Catholic Polish descent (his family roots go back to the region of the city of Vileyka in present-day Belarus ), but his immediate ancestors came from Siberia .

A Polish revolutionary in the January Uprising of 1863–1864, Bolesław Szostakowicz went into exile in Narym (near Tomsk ) in 1866 during the repression that followed Dmitri Karakózov's assassination attempt on the Tsar Alexander II .

When his period of exile ended, Szostakowicz decided to remain in Siberia , where he became a successful banker in Irkutsk and raised a large family. His son, Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich, the composer's father, was born in exile in Narym in 1875, studied physics and mathematics at St. Petersburg University and graduated in 1899. He then went to work as an engineer with Dmitri Mendeleyev at the Bureau of Weights and Measures in St. Petersburg. In 1903, he married Sofiya Vasílievna Kokoúlina, one of six children born to a Siberian who also immigrated to the capital.

House in which Shostakovich was born (now School no. 267), with a commemorative plaque on the left.

Her son, Dmitri Dmitrievich Shostakovich, showed great musical talent after he began taking piano lessons with his mother at the age of nine. On several occasions, he showed a remarkable ability to remember what his mother had played in the previous lesson and was "caught in the act" of playing music from the previous lesson while pretending to read different music placed in front of him.

In 1918, he wrote a funeral march in memory of two leaders of the Russian Constitutional Democratic Party murdered by Bolshevik sailors.

In 1919, at the age of 13, Shostakovich was admitted to the Petrograd Conservatory, then directed by Aleksandr Glazunov , who closely monitored his progress and supported him.

He studied piano with Leonid Nikoláiev after a year in the class of Elena Rózanova, composition with Maximilián Steinberg and counterpoint and fugue with Nikolái Sokolov, of whom he became a friend.

He also attended the musical history classes of Aleksandr Ossovski. Steinberg tried to guide it in the way of the great Russian composers, but was disappointed to see him "wasting" his talent imitating Igor Stravinsky and Sergei Prokófiev .

Shostakovich also suffered from his apparent lack of political zeal, and initially failed his Marxist methodology exam in 1926. His first major musical achievement was the First Symphony (premiered in 1926), written as his graduation piece in the age of 19 years. This work attracted the attention of Mijaíl Tujachevski , who helped him find accommodation and work in Moscow , and sent a driver in "a very elegant car" to take him to a concert.

Beginning of his career

After graduation, Shostakovich initially embarked on a dual career as a concert pianist and composer, but his dry playing style was often unappreciated (his American biographer, Llorer Fay, comments on his "emotional restraint » and «fascinating rhythmic impulse». He won an 'honorable mention' at the first Frédéric Chopin International Piano Competition in Warsaw in 1927 and attributed the disappointing result to suffering from appendicitis and the all-Polish jury. He had his appendix removed in April this year.

After the competition, Shostakovich met the conductor Bruno Walter , who was so impressed with his First Symphony that he conducted it at its premiere in Berlin that same year. Leopold Stokowski was equally impressed and directed the play in its premiere in the United States the following year in Philadelphia . Stokowski also made the first recording.

Shostakovich concentrated on composition thereafter, and soon limited his performances mainly to his own works. In 1927, he wrote his Second Symphony (subtitled October ), a patriotic piece with a pro-Soviet choral ending. Due to its experimental nature , as with the later Third Symphony , it was not acclaimed by critics with the enthusiasm received in the First .

This year also marked the beginning of Shostakovich's relationship with Iván Sollertinsky , who remained his closest friend until the latter's death in 1944. Sollertinsky introduced the composer to the music of Gustav Mahler , which had a strong influence on him from his Fourth Symphony onwards.

While writing the Second Symphony , Shostakovich also began work on his satirical opera The Nose , based on the story of the same name by Nikolai Gogol . In June 1929, against the composer's wishes, the opera was performed and fiercely attacked by the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians (RAPM).

Its stage premiere on 18 January 1930 opened to generally poor reviews and widespread misunderstanding among musicians.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Shostakovich worked at TRAM, a proletarian youth theater . Although he did little work on this publication, it protected him from ideological attack. Much of this period was spent writing her opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk , which was first performed in 1934. It was an immediate success, both popularly and officially. It was described as "the result of the general success of socialist construction, of correct party politics", and as an opera that "could only have been written by a Soviet composer educated in the best tradition of Soviet culture".

Shostakovich married his first wife, Nina Varzar, in 1932. Difficulties led to divorce in 1935, but the couple soon remarried when Nina became pregnant with their first daughter, Galina.

Between October 1950 and March 1951 he composed the 24 Preludes and Fugues op. 87, dedicated to the pianist Tatiana Petrovna Nikolaieva . During the period that Shostakovich was composing these pieces, Nikolayeva called him every day and went to her house to watch him play what he had re-composed.

In 1952, the complete 24 preludes and fugues were performed for the first time, in the city of Leningrad, by Nikolayeva.

Read the full article

0 notes

Photo

Nadezhda Markina in Elena (Andrey Zvyagintsev, 2011)

Cast: Nadezhda Markina, Andrey Smirnov, Elena Lyadova, Aleksey Rozin,

Evgeniya Konushkina, Igor Ogurtsov, Vasiliy Michkov, Aleksey Maslodudov. Screenplay: Oleg Negin, Andrey Zvyagintsev. Cinematography: Mikhail Krichman. Production design: Vassili Gritskov, Andrey Ponkratov, Zhukov. Film editing: Anna Mass. Music: Philip Glass.

Like Andrey Zvyagintsev's 2014 Oscar-nominated Leviathan, Elena is a scathing portrait of contemporary Russia. But where Leviathan was rough and boisterous, Elena is quiet, austere, and slow. Perhaps too slow for some tastes: The film begins with a long take of the balcony of an apartment house seen through the branches of a tree. For a long time, nothing happens. We hear only the bark of a dog and some street noises. Then we gradually become aware that we are watching the sun rise, reflected in the windows of an apartment. It's the sleek, modern home of the wealthy retired businessman Vladimir (Andrey Smirnov) and his wife, Elena (Nadezhda Markina). A couple in late middle age, they have been married for ten years, having met when he was hospitalized for peritonitis and she was his nurse. It's the second marriage for both, and each has a child from the previous marriage: he a daughter, Katya (Elena Lyadova), she a son, Sergey (Aleksey Rozin). But Elena resents the fact that Vladimir dotes on the spoiled playgirl Katya, complaining that she gets in touch with her father only when she wants money. And Vladimir disapproves when Elena gives the money from her own pension to support the unemployed Sergey, his wife, and their two children, 17-year-old Sasha (Igor Ogurtsov) and an infant, who live in a cramped Soviet-era apartment house with a view of the cooling towers of a nuclear plant. Elena wants Sasha to go to university -- otherwise, he'll be drafted into the army -- and appeals to Vladimir for financial help. He refuses: Sergey should get a job and support his own family, besides, the army will be good for Sasha. Then Vladimir suffers a heart attack, and while recovering decides that he should make a will, leaving his estate to Katya and an annuity to support Elena. Before he can see a lawyer, however, Elena slips a couple of Viagra -- knowing that they are contraindicated for heart attack patients -- in with his other meds. After the funeral, the lawyer tells Elena and Katya that the estate will have to be divided between them. The story, by Zvyagintsev and Oleg Negin, moves with the inexorable melancholy of the excerpts from Philip Glass's Symphony No. 3 that sometimes accompany it on the soundtrack. Zvyagintsev's refusal to urge along the story and instead to concentrate on the measured pace of Elena's life, gives the film a grounding in actuality, reinforced by Markina's subtle underplaying of her role. It's a chilly film in many ways, but in its depiction of a society defined by the extremes of new rich and old underclass, it has a decided impact.

0 notes

Quote

As a grand send-off to Russian week, I wanted to share this monumental work by Nikolai Myaskovsky. The Symphony no.6 in eb minor is the most ambitious of all his symphonies (a rare case of a 20th century prolific symphonist, he wrote 27 in total), and is written in the scale of late Romanic symphonists (especially Mahler). It is an interesting mix of Post-Romanticism and Soviet Modernism, where textures and colors can get brutal and murky, or more lyrical and luscious. The intensity of emotions in the work is likely the composer’s response to increasing political hostility, and the death of his father and other family members to post-war famines. This symphony is like a large-scale memorial to the victims of WWI, and the Revolution and Civil wars, the darkest times happening immediately after each other. The first movement is a large-scale sonata form that is full of restless pulsations. The second as whirlwinds surrounding a calmer section based on Dies Irae. The third revises the main melody of the first movement into something more glorious, before falling apart and dissipating into despair. Despite the general gloominess, solemnity, and violence that happens in the music, the ending includes a chorus singing an old Russian hymn “How Soul Left the Body”, and the orchestra drifts off in a peaceful air, maybe hoping for a better future, or maybe looking back at better times.

Thank you for joining us this week! – Nick O, guest editor @mikrokosmos

musicainextenso: As a grand send-off to Russian week, I wanted to share this monumental work by Nikolai Myaskovsky. The Symphony no.6 in eb minor is the most ambitious of all his symphonies (a rare case of a 20th century prolific symphonist, he wrote 27 in total), and is written in the scale of late Romanic…

0 notes

Quote

As a grand send-off to Russian week, I wanted to share this monumental work by Nikolai Myaskovsky. The Symphony no.6 in eb minor is the most ambitious of all his symphonies (a rare case of a 20th century prolific symphonist, he wrote 27 in total), and is written in the scale of late Romanic symphonists (especially Mahler). It is an interesting mix of Post-Romanticism and Soviet Modernism, where textures and colors can get brutal and murky, or more lyrical and luscious. The intensity of emotions in the work is likely the composer’s response to increasing political hostility, and the death of his father and other family members to post-war famines. This symphony is like a large-scale memorial to the victims of WWI, and the Revolution and Civil wars, the darkest times happening immediately after each other. The first movement is a large-scale sonata form that is full of restless pulsations. The second as whirlwinds surrounding a calmer section based on Dies Irae. The third revises the main melody of the first movement into something more glorious, before falling apart and dissipating into despair. Despite the general gloominess, solemnity, and violence that happens in the music, the ending includes a chorus singing an old Russian hymn “How Soul Left the Body”, and the orchestra drifts off in a peaceful air, maybe hoping for a better future, or maybe looking back at better times.

Thank you for joining us this week! – Nick O, guest editor @mikrokosmos

musicainextenso: As a grand send-off to Russian week, I wanted to share this monumental work by Nikolai Myaskovsky. The Symphony no.6 in eb minor is the most ambitious of all his symphonies (a rare case of a 20th century prolific symphonist, he wrote 27 in total), and is written in the scale of late Romanic…

0 notes

Text

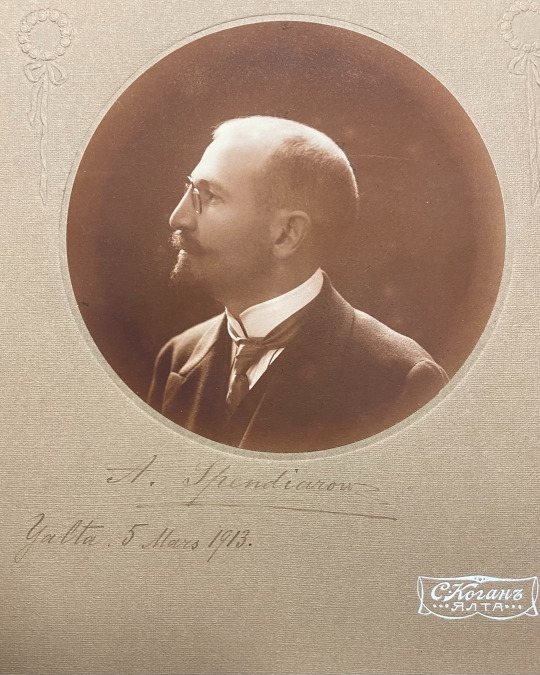

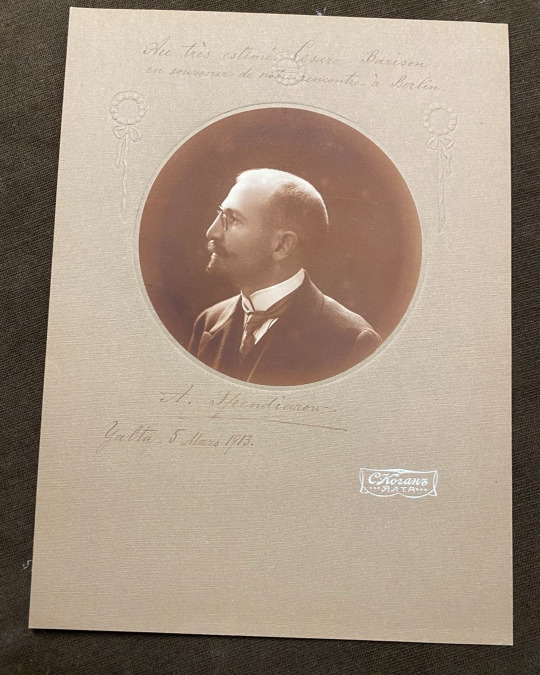

OTD in Music History: Obscure but historically important Armenian-Soviet composer, conductor, and pedagogue Alexander Afanasyevich Spendiaryan (1871 - 1928) -- who often went by "Spendiarov" -- is born in what is now modern-day Ukraine.

Spendiarov is a little-known figure today, except in Armenia, where he is still celebrated as the "Father of Armenian Symphonic Music."

After obtaining a law degree in Moscow in 1894, Spendiarov traveled to St. Petersburg to show some musical compositions that he had composed in his spare time to legendary Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844 - 1908). Rimsky-Korsakov was highly complementary, and, from 1896 to 1900, Spendiarov stayed on and studied music privately with him; according to fellow composer Alexander Glazunov (1865 - 1936), Rimsky-Korsakov always “considered [Spendiarov] to be a serious and talented composer with a great flair for composition.”

In the best works dating from his mature years, Spendiarov cultivated a type of late-Romantic Russian “orientalism” in which the elements of folk songs native to the peripheral regions of the Old Russian Empire were adroitly arranged and decked out in the colorful harmonies of the Russian "Nationalist" school of music spear-headed by Rimsky-Korsakov and his colleagues in "The Mighty Five."

Spendiarov's relocation from Crimea to Yerevan, Armenia, in in the early 1920s had a significant impact on his creative activities. In Armenia, he focused more of his time on teaching (he was one of the first significant figures to support the young Aram Khachaturian), helped to organize the first symphony orchestra ever assembled in the country, and spent a significant amount of time studying and transcribing Armenian folk music. When Spendiarov died from pneumonia in 1928, he was widely mourned as a national cultural hero.

PICTURED: A beautiful publicity photo showing the middle-aged Spendiarov, which he signed and inscribed to a friend in Yalta in 1913.

#Alexander Spendiaryan#Alexander Spendiarov#waltz#Concert Prelude#Concert Waltz#Oh Rose#composer#conductor#pedagogue#Russian Music#Classical Music#Music#History#music history#folk music#Armenian#Yerevan#ethnomusicology#sepia photography#studio photography#vintage photography#photography

10 notes

·

View notes

Quote

As a grand send-off to Russian week, I wanted to share this monumental work by Nikolai Myaskovsky. The Symphony no.6 in eb minor is the most ambitious of all his symphonies (a rare case of a 20th century prolific symphonist, he wrote 27 in total), and is written in the scale of late Romanic symphonists (especially Mahler). It is an interesting mix of Post-Romanticism and Soviet Modernism, where textures and colors can get brutal and murky, or more lyrical and luscious. The intensity of emotions in the work is likely the composer’s response to increasing political hostility, and the death of his father and other family members to post-war famines. This symphony is like a large-scale memorial to the victims of WWI, and the Revolution and Civil wars, the darkest times happening immediately after each other. The first movement is a large-scale sonata form that is full of restless pulsations. The second as whirlwinds surrounding a calmer section based on Dies Irae. The third revises the main melody of the first movement into something more glorious, before falling apart and dissipating into despair. Despite the general gloominess, solemnity, and violence that happens in the music, the ending includes a chorus singing an old Russian hymn “How Soul Left the Body”, and the orchestra drifts off in a peaceful air, maybe hoping for a better future, or maybe looking back at better times.

Thank you for joining us this week! – Nick O, guest editor @mikrokosmos

musicainextenso: As a grand send-off to Russian week, I wanted to share this monumental work by Nikolai Myaskovsky. The Symphony no.6 in eb minor is the most ambitious of all his symphonies (a rare case of a 20th century prolific symphonist, he wrote 27 in total), and is written in the scale of late Romanic…

0 notes

Quote

As a grand send-off to Russian week, I wanted to share this monumental work by Nikolai Myaskovsky. The Symphony no.6 in eb minor is the most ambitious of all his symphonies (a rare case of a 20th century prolific symphonist, he wrote 27 in total), and is written in the scale of late Romanic symphonists (especially Mahler). It is an interesting mix of Post-Romanticism and Soviet Modernism, where textures and colors can get brutal and murky, or more lyrical and luscious. The intensity of emotions in the work is likely the composer’s response to increasing political hostility, and the death of his father and other family members to post-war famines. This symphony is like a large-scale memorial to the victims of WWI, and the Revolution and Civil wars, the darkest times happening immediately after each other. The first movement is a large-scale sonata form that is full of restless pulsations. The second as whirlwinds surrounding a calmer section based on Dies Irae. The third revises the main melody of the first movement into something more glorious, before falling apart and dissipating into despair. Despite the general gloominess, solemnity, and violence that happens in the music, the ending includes a chorus singing an old Russian hymn “How Soul Left the Body”, and the orchestra drifts off in a peaceful air, maybe hoping for a better future, or maybe looking back at better times.

Thank you for joining us this week! – Nick O, guest editor @mikrokosmos

musicainextenso: As a grand send-off to Russian week, I wanted to share this monumental work by Nikolai Myaskovsky. The Symphony no.6 in eb minor is the most ambitious of all his symphonies (a rare case of a 20th century prolific symphonist, he wrote 27 in total), and is written in the scale of late Romanic…

0 notes

Text

Gruß aus dem Urlaub

LePenseur:»von LePenseur ... diesmal ganz speziell an den geschätzten Kollegen Lechner, dem die Symphonie No. 6 in es-moll, op. 23 von Nikolai Mjaskowski, komponiert in den Jahren 1921-23, (vermutlich/hoffentlich!) gefallen wird:

1. Poco largamente, ma allegro - Allegro feroce 2. Presto tenebroso - Andante moderato - Presto (22:30) 3. Andante appassionato - Molto più appassionato e rubato - Ancora più animato - Andante sostenuto, con tenerezza e gran espressione (31:26) 4. Allegro molto vivace (46:32)

Youtube liefert eine m.E. recht gute Bescheibung des Werkes (das in dieser Aufnahme durch das Göte-borg Symphonieorchester unter Neeme Järvi erklingt):

The Symphony No. 6 in E-flat minor, Op. 23 was composed between 1921 and 1923. It is the largest and most ambitious of his 27 symphonies, planned on a Mahlerian scale, and uses a chorus in the finale. It has been described as 'probably the most significant Russian symphony between Tchaikovsky's Pathétique and the Fourth Symphony of Shostakovich'. (Myaskovsky in fact wrote part of the work in Klin, where Tchaikovsky wrote the Pathétique.) The premiere took place at the Bolshoi Theatre, Moscow on 4 May 1924, conducted by Nikolai Golovanov and was a notable success.

Soviet commentators used to describe the work as an attempt to portray the develop-ment and early struggles of the Soviet state, but it is now known that its roots were more personal. The harsh, emphatically descending chordal theme with which the symphony begins apparently arose in the composer's mind at a mass rally in which he heard the Soviet Procurator Nikolai Krylenko conclude his speech with the call "Death, death to the enemies of the revolution!"

Myaskovsky had been affected by the deaths of his father, his close friend Alexander Revidzev and his aunt Yelikonida Konstantinovna Myaskovskaya, and especially by seeing his aunt’s body in a bleak, empty Petrograd flat during the winter of 1920. In 1919 the painter Lopatinsky, who had been living in Paris, sang Myaskovsky some French Revolutionary songs which were still current among Parisian workers: these would find their way into the symphony's finale. He was also influenced by Les Aubes (The Dawns), a verse drama by the Belgian writer Emile Verhaeren, which enacted the death of a revolutionary hero and his funeral

The scherzo is apparently inspired by the winter winds blowing outside the house where the composer's aunt lay dead, with an Andante moderato trio that loosely references the simpleton's Lament in Mussorgsky's Boris Godonuv, Act IV, Scene II, ("Tears, bitter tears must fall, Our holy people must weep ... Woe, woe unto Russia! Weep, weep Russian folk, Hungry folk") The episodic finale begins with a bright E flat major fantasia on the French revolu-tionary songs Ah! ça ira and Carmagnole then turning to a dark C minor with the Dies Irae. A clarinet introduces the melody of a Russian Orthodox burial hymn, 'How the Soul Parted from the Body' (Shto mui vidyeli? – 'What did we see? A miraculous wonder, a dead body ...'). The chorus enters with wailing cries that punctuate a setting of the hymn. In the coda the main theme of the third movement returns as the basis of a peaceful epilogue.Das Werk ist mit seiner Dauer von über einer Stunde Mjaskowskis längste Symphonie und sticht auch durch seine große Orchesterbesetzung (so bspw. dreifaches Holz, 6 Hörner, zahlreiches Schlagwerk, Harfe, Celesta und Chor) aus dem übrigen Symphonie-Korpus des Komponisten hervor.

Ein großes Werk, dessen musikalisches Format m.E. die eingesetzten Mittel mehr als rechtfertigt — ein auch ein Jahrhundert nach seiner Entstehung frisch und lebendig anzuhörendes Meisterwerk! http://dlvr.it/STR547 «

0 notes

Text

Events 12.22 (before 1950)

AD 69 – Vespasian is proclaimed Emperor of Rome; his predecessor, Vitellius, attempts to abdicate but is captured and killed at the Gemonian stairs.

401 – Pope Innocent I is elected, the only pope to succeed his father in the office.

856 – Damghan earthquake: An earthquake near the Persian city of Damghan kills an estimated 200,000 people, the sixth deadliest earthquake in recorded history.

880 – Luoyang, eastern capital of the Tang dynasty, is captured by rebel leader Huang Chao during the reign of Emperor Xizong.

1135 – Three weeks after the death of King Henry I of England, Stephen of Blois claims the throne and is privately crowned King of England, beginning the English Anarchy.

1216 – Pope Honorius III approves the Dominican Order through the papal bull of confirmation Religiosam vitam.

1489 – The forces of the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, take control of Almería from the Nasrid ruler of Granada, Muhammad XIII.

1769 – Sino-Burmese War: The war ends with the Qing dynasty withdrawing from Burma forever.

1788 – Nguyễn Huệ proclaims himself Emperor Quang Trung, in effect abolishing on his own the Lê dynasty.

1790 – The Turkish fortress of Izmail is stormed and captured by Alexander Suvorov and his Russian armies.

1807 – The Embargo Act, forbidding trade with all foreign countries, is passed by the U.S. Congress at the urging of President Thomas Jefferson.

1808 – Ludwig van Beethoven conducts and performs in concert at the Theater an der Wien, Vienna, with the premiere of his Fifth Symphony, Sixth Symphony, Fourth Piano Concerto and Choral Fantasy.

1851 – India's first freight train is operated in Roorkee, to transport material for the construction of the Ganges Canal.

1851 – The Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., burns.

1864 – American Civil War: Savannah, Georgia, falls to the Union's Army of the Tennessee, and General Sherman tells President Abraham Lincoln: "I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the city of Savannah".

1885 – It�� Hirobumi, a samurai, becomes the first Prime Minister of Japan.

1888 – The Christmas Meeting of 1888, considered to be the official start of the Faroese independence movement.

1890 – Cornwallis Valley Railway begins operation between Kentville and Kingsport, Nova Scotia.

1891 – Asteroid 323 Brucia becomes the first asteroid discovered using photography.

1894 – The Dreyfus affair begins in France, when Alfred Dreyfus is wrongly convicted of treason.

1906 – An Mw 7.9 earthquake strikes Xinjiang, China, killing at least 280.

1920 – The GOELRO economic development plan is adopted by the 8th Congress of Soviets of the Russian SFSR.

1921 – Opening of Visva-Bharati College, also known as Santiniketan College, now Visva Bharati University, India.

1937 – The Lincoln Tunnel opens to traffic in New York City.

1939 – Indian Muslims observe a "Day of Deliverance" to celebrate the resignations of members of the Indian National Congress over their not having been consulted over the decision to enter World War II with the United Kingdom.

1940 – World War II: Himara is captured by the Greek army.

1942 – World War II: Adolf Hitler signs the order to develop the V-2 rocket as a weapon.

1944 – World War II: Battle of the Bulge: German troops demand the surrender of United States troops at Bastogne, Belgium, prompting the famous one word reply by General Anthony McAuliffe: "Nuts!"

1944 – World War II: The People's Army of Vietnam is formed to resist Japanese occupation of Indochina, now Vietnam.

1945 – U.S. President Harry S. Truman issues an executive order giving World War II refugees precedence in visa applications under U.S. immigration quotas.

1948 – Sjafruddin Prawiranegara established the Emergency Government of the Republic of Indonesia (Pemerintah Darurat Republik Indonesia, PDRI) in West Sumatra.

0 notes