#Depicting: Nintendo Entertainment System

Text

Super Smash Bros. Melee - Part 1

FDrom https://www.spriters-resource.com/gamecube/ssbm/

From https://tcrf.net/Super_Smash_Bros._Melee/Version_Differences

#Super Smash Bros. Melee#Depicted by: Nintendo GameCube#Depicting: Nintendo GameCube Controller#Depicting: Nintendo Entertainment System#Depicting: Game Boy#Depicting: Super Smash Bros. Nintendo 64 Game Box#Depicting: Nintendo 64#Depicting: Super Smash Bros. Nintendo 64 Game Pak#Depicting: Nintendo 64 Controller#Depicting: Nintendo GameCube#Depicting: Game Boy Advance#Depicting: Game Boy Pocket#Depicting: Super Nintendo Entertainment System#Depicting: Virtual Boy#Depicting: Famicom#Depicting: Golf Famicom Cartridge#Depicting: Dai Rantō Smash Brothers Nintendo 64 Game Box#Depicting: Dai Rantō Smash Brothers Nintendo 64 Game Pak#Depicting: Super Famicom#Depicting: Super Famicom Controller

1 note

·

View note

Text

Dimentio Analysis

My thoughts on this Dimentio post, recently shared with me by @iukasylvie! The post: https://altermentality.wordpress.com/2016/02/10/flair-for-the-dramatic/.

! CONTAINS SPOILERS FOR SUPER PAPER MARIO !

Okay before I address the article, I should establish my own Dimentio headcanons. I see our silly jester as a sociopath, in that he can't feel love in the same way as other people. Like Bleck, he has a void inside of him, but Dimentio fills it by feeding off of others. Basically, he likes playing around and taunting people because of how emotionally reactive they are, it's how he fills himself up. Mimi's his favorite to mess around with because she's VERY reactive. As for why he wants his own world: he wants to put on a show. The whole of existence, dedicated to entertaining him. The only characters I can liken this to are the Celestial Toymaker (DW) and the Collector (TOH).

Now first off, the article references SPM in the context of "commedia dell'arte", which was a form of theater in Italy during the Renaissance. This form of theater had three types of characters: innamorati (the star-crossed lovers), vecchi (the powerful elders of society), and zanni (the clowns). The common plot of these plays? Two young lovers, hindered by the elders, who end up turning to the zanni to reach a happy ending.

Of course, Dimentio is a zanni character type. He may not help the Count reach his happy ending directly, but his actions do lead to the wedding with Tippi so, in a sense, this does fit the archetype. And of course, I don't have to tell you who the innamorati characters are. Anyone who knows a lick about Shakespeare probably already knows the love story of Blumiere and Timpani uses a pretty strong "forbidden love" trope, but it's interesting to see this somewhat supported by other forms of theater arts! To say Nintendo and Intelligent Systems had commedia dell'arte in mind when writing SPM's story would be a stretch, but it's always cool to see some elements match across different eras and types of storytelling.

Moving on, does Dimentio care about the other minions? The article eventually concludes that yes, he must, because how could you live in a castle with four other people and not grow to love them? My headcanon lines up with this pretty well--after all, Dimentio words the Count's lie about creating a new world as a "betrayal", and a betrayal facilitates caring enough to trust someone in the first place (points at Olly's entire arc with Olivia in The New Void). But Dimentio doesn't know *how* to love, and his version of "care" is different. He likes having the others around, but as players in his game, as entertainment. That's how he sees it. He fixates on them specifically for a reason he'd never care to explain.

New Void Spoilers Below.

You could say he fixates on Luigi, too, which might seem strange when they had far less time together. Shipping aside, I think canonically Dimentio fixes on Luigi because he's the key to everything, he's a highly valuable asset and Dimentio knows it. In the New Void, this isn't exactly the case. Dimentio doesn't have anything to gain by making Luigi suffer, it's just pure fun. Sure, he COULD torment some Shaydes or D-Men instead, but they're dead and they're boring. Dimentio's also been in the Underwhere for...awhile, and Luigi is a familiar face. In his own way, Dimentio's been a little lonely. It's just that, his way of acting on this feeling is to turn it into a game of psychological warfare...

New Void Spoilers End.

Overall, the strongest part of the article is the description of Dimentio's ideal world. Don't get me wrong, I'm a big fan of darkmarxsoul's Chaos Trilogy, but this depiction of Dimentio's universe might be the best I've ever seen. “Dimentio’s goal is to maximize the amount of drama in the universe…a world with the dials of mortal anguish and despair and even joy set to maximum volume, and the banishment of the mundane. A world where he pulls all the strings to ensure this happens. The Ultimate Show.” Chilling! It's like Bill Cipher's whole Weirdmageddon deal, except rather than maximizing weirdness, DImentio would be maximizing drama, flair, and theatrics. All the world's a stage, and whatnot.

I LOVE this idea for a world of his so much that it's a wonder I haven't started writing fics centered around it already! All these new people living what they think are just ordinary lives, not knowing that it's all being orchestrated by a being that craves mere entertainment. Life as a musical, maybe a comedy tomorrow, or maybe a tragedy next week--all because Dimentio wants it to be. I mean, that's absolutely horrifying when you think about it! Enough for a brief existential crisis maybe! But it's also very cool >:)

In summary: what do we think about Dimentio? I think he's a sociopath who doesn't understand love but desperately wants to be entertained. The article's description of Dimentio's ideal world is scarily accurate and also has a LOT of fanfic potential. Dimentio himself is fun and silly, but also dangerous and probably not someone you'd want to interact with in real life.

As this is my opinion/interpretation, I'm too biased to say whether or not this aligns well with canon. But what do you think? Do you think this all fits Dimentio perfectly, or do you have other thoughts?

#paper mario#super paper mario#dimentio super paper mario#dimentio spm#headcanon#fanfic ideas#character analysis

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jungle Strike (subtitled The Sequel to Desert Strike, or Desert Strike part II in Japan) is a video game developed and published by Electronic Arts in 1993 for the Sega Genesis/Mega Drive. The game was later released on several other consoles such as the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES), and an upgraded version was made for DOS computers. The Amiga conversion was the responsibility of Ocean Software while the SNES and PC DOS versions were that of Gremlin Interactive, and the portable console versions were of Black Pearl Software. It is the direct sequel to Desert Strike (a best-seller released the previous year) and is the second installment in the Strike series. The game is a helicopter-based shoot 'em up, mixing action and strategy. The plot concerns two villains intent on destroying Washington, D.C. The player must use the helicopter and occasionally other vehicles to thwart their plans.

Its game engine was carried over from a failed attempt at a flight simulator and was inspired by Matchbox toys and Choplifter. Jungle Strike retained its predecessor's core mechanics and expanded on the model with additional vehicles and settings. The game was well received by most critics upon release. Publications praised its gameplay, strategy, design, controls and graphics.

Jungle Strike features two antagonists: Ibn Kilbaba, the son of Desert Strike's antagonist, and Carlos Ortega, a notorious South American drug lord. The opening sequence depicts the two men observing a nuclear explosion on a deserted island, while discussing the delivery of "nuclear resources" and an attack on Washington D.C.; Kilbaba seeks revenge for his father's death at the hands of the US, while Ortega wishes to "teach the Yankees to stay out of my drug trade".

The player takes control of a "lone special forces" pilot. The game's first level depicts the protagonist repelling terrorist attacks on Washington, D.C., including the President's limousine. Subsequent levels depict counter-attacks on the drug lord's forces, progressing towards his "jungle fortress". In the game's penultimate level, the player pursues Kilbaba and Ortega to their respective hideouts before capturing them.

The final level takes place in Washington, D.C. again, where the two antagonists attempt to flee after escaping from prison. The player must destroy both Kilbaba and Ortega and stop four trucks carrying nuclear bombs from blowing up the White House. The PC version also extends the storyline with an extra level set in Alaska, in which the player must wipe out the remainder of Ortega's forces under the command of a Russian defector named Ptofski, who has taken control of oil tankers and is threatening to destroy the ecosystem with crude oil if his demands are not met. Once all levels are complete, the ending sequence begins and depicts the protagonist and his co-pilot in an open-topped car in front of cheering crowds.

Jungle Strike is a helicopter-based shoot 'em up, mixing action and strategy. The player's main weapon is a fictionalised Comanche attack helicopter. Additional vehicles can be commandeered: a motorbike, hovercraft and F-117. The latter in particular features variable height and unlimited ammunition, but is more vulnerable to crashes. The game features an "overhead" perspective "with a slight 3D twist". The graphics uses a 2.5D perspective which simulates the appearance of being 3D.

Levels consist of several missions, which are based around the destruction of enemy weapons and installations, as well as rescuing hostages or prisoners of war, or capturing enemy personnel. The helicopter is armed with machine guns, more powerful Hydra rockets and yet more deadly Hellfire missiles. The more powerful the weapon, the fewer can be carried: the player must choose an appropriate weapon for each situation. Enemy weapons range from armoured cars to artillery and tanks.

The player's craft has a limited amount of armour, which is depleted as the helicopter is hit by enemy fire. Should armour reach zero, the craft will be destroyed, costing the player a life. The player must outmanoeuvre enemies to avoid damage, but can replenish armour by means of power-ups or by airlifting rescued friendlies or captives to a landing zone.

Vehicles have a finite amount of fuel which is steadily depleted as the level progresses. Should the fuel run out, the vehicle will crash, again costing the player a life. The craft can refuel by collecting fuel barrels. Vehicles also carry limited ammunition, which must be replenished by means of ammo crates.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

WEEK 9: GAMING COMMUNITIES, SOCIAL GAMING AND LIVE STREAMING

1. History of video games

Video games are interactive digital games that are played on many platforms, such as smartphones, computers, or consoles. They mainly feature one or more players participating in a virtual environment, controlling characters to accomplish objectives, overcome challenges, and meet goals in the game.

The history of video games began in the 1950s - 1960s when programmers started creating basic games and simulations on early-aged minicomputers. A remarkable example of them is Spacewar!, which was designed by the students of MIT in 1962. The game depicts a simple space combat scenario, where two players control spaceships and engage the battle in a 2D space environment.

Thanks to SpaceWar! and other early-aged video games, the foundation for the industry of gaming had been laid. In 2005 and 2006, Microsoft’s Xbox 360, Sony’s PlayStation 3, and Nintendo’s Wii kicked off the modern age of high-definition gaming (Editors 2017). These days, video games are being more and more developed with modern technologies, 3D dimension environments, stunning graphics… Newer control systems and family-oriented games have made it common for many families to engage in video game play as a group. Online games have continued to develop, gaining unprecedented numbers of players (University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing 2016). The most remarkable of them are League of Legends, FC Online, Fortnite… With a huge number of players, high-resolution graphics, and competitive gameplay, they dominated most game markets in many countries and opened a new environment for gamers to show off their abilities.

2. The culture of gaming

Since the gaming industry began to develop, it also formed the culture of playing video games. It consists of the popular attitudes, behaviors, and practices that surround gamers and their communities. One of the most popular stereotypes about gamers is that they are considered to be mainly young people, white or East-Asian, and predominantly males. According to the Entertainment Software Association’s 2018 recent report, 45% of gamers in the U.S. are female. However, among core gamers, males dominate, making the female statistic somewhat misleading (Fu n.d.). Sexism and inappropriate behavior towards females are commonplace. Players appear to conform to stereotypical masculine norms and tend to maintain a male-dominant hierarchy.

Besides the dominance of males in old stereotypes about video games, the culture of nerd and geek is also another remarkable stereotype. Gamers are mainly seen as nerdy, lazy, and unattractive. They are also considered not to have stable study or job occupations, most of the time focusing on video games. The view from the society to them is mainly negative as they are seen to have no beneficial contribution to the community. However, on the other hand, those people are highly welcomed in gaming communities, who share with them many similar interests and behaviors.

3. Gaming communities

Since the birth of video games, players have always been looking to find like-minded people. From the first pixel adventures to today’s multiplayer online worlds, gaming communities have played a huge role in transforming games from mere entertainment to true cultural phenomena (Games 2023). These communities mainly take place in online games environments or social media such as Steam Community, Discord, Reddit… A number of them can also bond together by performing real-life activities. There have been gaming events which are hosted to showcase technologies and connect gamers such as Gamescom, Taipei Game Show, DreamHack… In Vietnam, these occursions are becoming more popular as they can be hosted locally with a small number of gamers in local gaming centers or huge tournaments in arenas. Communities of reputable games such as Gunny, League of Legends, and FC Online are the main contributors to the shared environment. A number of them also take part in community movements such as MixiGaming. In 2020, the group donated about 200 million VND to build bridges for a remote mountainous village in Cao Bang province and used the residue funds to give bicycles to children with difficulties traveling to their schools. These activities improved the image of gaming communities in many people, influencing them to change their thoughts about gaming culture.

4. Live-streaming in gaming culture

The donations of MixiGaming mainly come from live streaming sessions of Do Mixi, a reputable gamer in Vietnam. He conducted live videos and publicized all the received money to maintain transparency of the fund. Live-streaming is also an attractive point not only for him but also for many gamers. Video game live streaming is a kind of real-time video social media that integrates traditional broadcasting and online gaming (Li, Wang & Liu 2020). In recent years, the online broadcast industry has developed rapidly with the emergence of various live-streaming platforms, such as Twitch, YouTube, Douyu, Huya, and so on. In 2016, Twitch and YouTube Gaming had more than 470 million regular visitor members in 2016 (more than 50% of gamers in the US, Europe, and Asia Pacific). In recent years, the market for this type of gaming media has even increased more sharply, making it an ideal market for many streamers. From these live-streaming sessions, communities are formed around them as the streamer attracts several viewers. They can make a great contribution to other content of the live streaming channels, whether to give suggestions for the next video or be on stage with the streamer. The phenomenon gave birth to many communities and improved the influence of gamers, making live streaming a lucrative market and developing the gaming industry as well.

References:

1. Editors, H com 2017, Video Game History, HISTORY, viewed 21 March 2024, https://www.history.com/topics/inventions/history-of-video-games#modern-age-of-gaming.

2. Fu, D n.d., A Look at Gaming Culture and Gaming Related Problems: From a Gamer’s Perspective, viewed 21 March 2024, https://smhp.psych.ucla.edu/pdfdocs/gaming.pdf.

3. Games, BG 2023, Gaming Communities: The Rise and Impact of Gaming Communities on the World of Video Games, Medium, viewed 21 March 2024, https://bggames.medium.com/gaming-communities-the-rise-and-impact-of-gaming-communities-on-the-world-of-video-games-1fec152f649f.

4. Li, Y, Wang, C & Liu, J 2020, ‘A Systematic Review of Literature on User Behavior in Video Game Live Streaming’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 17, no. 9, p. 3328.

5. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing 2016, 10.2 The Evolution of Electronic Games, open.lib.umn.edu, University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing edition, 2016. This edition is adapted from a work originally produced in 2010 by a publisher who has requested that it not receive attribution.

0 notes

Text

"Vigilante" for the PC Engine console

Released in 1988 for the PC Engine (TurboGrafx-16 in North America), "Vigilante" represented a significant milestone in the evolution of beat 'em up games on home consoles. Originally developed by Irem as an arcade game, it was subsequently adapted for the PC Engine, showcasing the console's ability to deliver arcade-quality experiences in the home. "Vigilante" not only pushed the technological capabilities of the PC Engine but also stirred controversy with its promotional artwork, highlighting the complex interplay between video game content, marketing, and audience reception during the late 1980s.

Historical Context

During the late 1980s, the video game industry was rapidly evolving with the transition from 8-bit to 16-bit technology. The PC Engine was at the forefront of this transition in Japan, boasting superior graphical and audio capabilities compared to many of its contemporaries. "Vigilante" was released during this transformative period and was part of a broader trend of arcade games being ported to home consoles, a practice that allowed gamers to enjoy arcade hits without leaving their homes.

Gameplay and Technological Innovations

"Vigilante" continued the tradition of side-scrolling beat 'em up games, following the success of titles like "Kung-Fu Master" (also by Irem) and "Double Dragon." The game involves the player taking on the role of a vigilante who must rescue his kidnapped girlfriend from a gang known as the "Skinheads." This premise drives the player through five distinct levels, each filled with numerous enemies and a boss character.

Technologically, "Vigilante" utilized the PC Engine's advanced graphics hardware to reproduce the detailed backgrounds and character sprites seen in the arcade version. The smooth scrolling and sprite-scaling capabilities were particularly notable, demonstrating the PC Engine's ability to handle dynamic visual effects that were crucial for maintaining the fast-paced action and visual depth of arcade games.

Controversial Artwork

The artwork used in the marketing and packaging of "Vigilante" drew controversy for its depiction of violence and its potential racial undertones. The original arcade release and some versions of the game featured artwork that included aggressive imagery and characters that some interpreted as promoting racial stereotypes, particularly the portrayal of the gang members. In an era where video game content was beginning to come under closer scrutiny for its impact on younger audiences, the artwork of "Vigilante" sparked discussions about the social responsibilities of game developers and publishers.

Moreover, the depiction of vigilantism raised ethical questions about the messages video games were sending regarding justice and self-help justice. These themes, combined with the game's violent content, contributed to the ongoing debates about the regulation of video game content and the need for content rating systems, which would later result in the establishment of organizations like the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) in the United States.

Cultural Impact and Legacy

"Vigilante" contributed to the popularization of the beat 'em up genre on home consoles, proving that the PC Engine was capable of bringing the arcade experience home. Its release helped cement the PC Engine's reputation as a system capable of rivaling more established platforms like the Nintendo Famicom (NES) and the Sega Genesis in terms of game quality and variety.

The controversy surrounding its artwork also played a role in highlighting the growing influence of video games in popular culture and their potential for controversy. It underscored the need for the video game industry to consider its broader social impact, particularly in terms of content presentation and marketing.

Conclusion

"Vigilante" for the PC Engine is a noteworthy example of the complexities involved in adapting arcade games to home consoles both from a technological perspective and a cultural one. It showcases how technological advancements in gaming hardware can expand the possibilities for game design and presentation, while also illustrating the challenges developers face in responsibly managing content that resonates with and impacts a diverse audience. As such, "Vigilante" remains a significant title in the history of video games, remembered both for its gameplay innovation and its role in broader cultural discussions.

#Vigilante#PC Engine#turbografx#HuCard#irem#Game#Retro#Retro game#Retrogame#Retro gaming#Retrogaming#Pixel Crisis

0 notes

Text

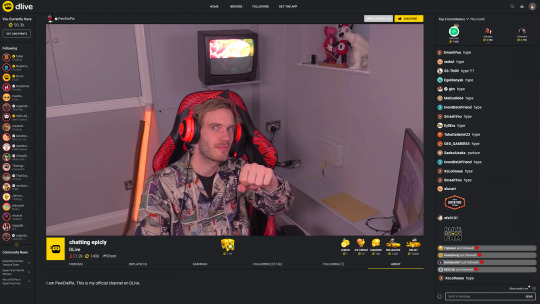

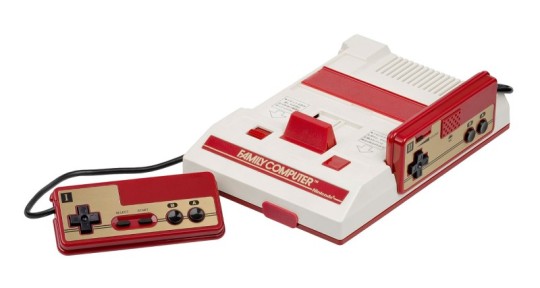

40 Years Later, Nintendo's Famicom Is Still Ahead Of Its Time

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/40-years-later-nintendos-famicom-is-still-ahead-of-its-time/

40 Years Later, Nintendo's Famicom Is Still Ahead Of Its Time

Introduction

As 1983 came into focus, the future of video games in North America looked bleak. Store shelves were crowded with poorly made games, and consumer interest waned substantially. Developers that ushered in the “golden age” of arcades and the first two generations of home consoles began to crash and burn at an alarming pace. In no time, the once billion-dollar industry was reduced to rubble.

In the summer of that same year, in Japan, gaming giant Nintendo released its first-ever home console with swappable cartridges. With its striking red and gold design, the Family Computer, better known as the Famicom, brought arcade hits like Donkey Kong and Mario Bros. into Japanese homes.

While the Famicom would go on to revitalize the North American gaming market as the VHS-inspired Nintendo Entertainment System, or NES, many of Nintendo’s quirky games and accessories were forever locked in its home country. With the Famicom’s 40th anniversary at hand, there’s never been a better time to look back on the bizarre and surprisingly innovative experiments Nintendo unleashed on Japanese players throughout the console’s celebrated run.

Famicommunication

Famicommunication

Unlike the NES, the Famicom came with its two blocky controllers wired directly to the console. While one might think this tethered design was to keep players from losing controllers, it was actually a simple cost-cutting measure – one Nintendo would soon regret as more and more players sought out replacements. Aptly anticipating a future filled with wacky accessories, Nintendo also included a 15-pin connector on the front of the Famicom, ready for anything the future might hold.

The most surprising addition to the Famicom’s original design was on the console’s second controller – a minuscule microphone, complete with a volume slider. The microphone’s inclusion was spearheaded by Nintendo Research and Development lead architect Masayuki Uemura, who felt younger players would enjoy hearing their own voices crackling out of TV speakers. Though his prediction wasn’t exactly wrong, the Famicom microphone was notoriously underutilized by developers, mostly lending itself to a handful of iconic Easter eggs in single-player games.

While a few early titles did make use of the microphone, most Japanese players wouldn’t be hollering into their second controller until 1986’s The Legend of Zelda. The 8-bit masterpiece featured a slew of unique enemies for protagonist Link to defeat on his quest, but few so wily as Pols Voice. Depicted as blobby rodents with enormous ears, the instruction manual explained that the monsters “hate loud noises.” With a deafening roar into the Famicom’s microphone, which could only be found on the second player controller, all Pols Voice on screen would be thoroughly eradicated. This was a far superior method to attacking with normal weapons, as the enemies’ nimble movements and high health made them especially annoying.

Strangely, the description of the Pols Voice hatred of loud noises was included in the manual for the English release, despite the fact developers had retooled the dungeon-dwelling baddies to now be weak to arrows. Zelda fans outside Japan wouldn’t feel the thrill of shouting an enemy to death until 2007’s Phantom Hourglass for the Nintendo DS, which allowed players to once again obliterate Pols Voice with a well-placed shriek.

Other notable examples of the Famicom microphone include Kid Icarus and the infamously difficult Takeshi’s Challenge. The former allowed players to verbally haggle down the price of items with shopkeepers by yammering on about whatever they liked, while the latter, starring comedian, actor, and director “Beat” Takeshi Kitano (Battle Royale, Violent Cop), had players using the microphone for a variety of tasks, such as bringing up a map and singing karaoke.

Famicomputing

Famicomputing

When Uemura and his team were first tasked with designing the Famicom, they envisioned a gaming device with a 16-bit CPU, a keyboard, a modem, and a floppy disk drive. With costs considered, none of these superfluous features made it far into the planning stage, each launching as their own separate accessory in the years to come. The first to resurface, released in the summer of 1984, was the boxy Family BASIC Keyboard bundle, a collaboration between Nintendo, Sharp Corporation, and Hudson Soft.

Included with a taller-than-average black cartridge and a hefty user manual, the Family BASIC Keyboard and its accompanying software were intended for the blossoming home computer crowd. At the time, BASIC (short for Beginners’ All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) was seen as the ideal programming language for novice developers and casual players alike. Family BASIC tried to make things even easier by including extra support for character sprites (including preset Mario and Donkey Kong models), backgrounds, controls, and music. Famed Mario composer Koji Kondo even got in on the action, penning a section in the user manual on how best to program chiptune melodies.

Though the bundle cost a hefty ¥14,800 at launch (the same price as the Famicom itself), the kit didn’t come with a way for players to save their creations or share them with others. For this top-of-the-line feature, Nintendo suggested purchasing the Famicom Data Recorder, a device that saved one’s game directly to a standard cassette tape – for an additional ¥9,800. Ironically, sharing games and rampant piracy of Famicom titles had become a huge issue for Nintendo by this time. The problem got so out of hand that various media associations across Japan lobbied to update the Japanese Copyright Act, essentially banning all video game rentals countrywide. The ban, which does give individual developers the ability to allow rentals of their games (though they rarely do), still exists to this day. Despite its price point, the Family BASIC bundle sold well enough to warrant an updated sequel – Family Basic V3.

Nintendo even toyed with the idea of a keyboard for the NES, to be included in a never-released collection called the Nintendo Advanced Video System. Shown off at the 1984 Consumer Electronics Show, the NES keyboard was featured alongside prototype controllers, a joystick, a cassette recorder, and a zapper that looked more like a robotic wand than a gun. Amazingly, every accessory in the Advanced Video System was wireless, connecting via infrared technology.

Famicompatible

Famicompatible

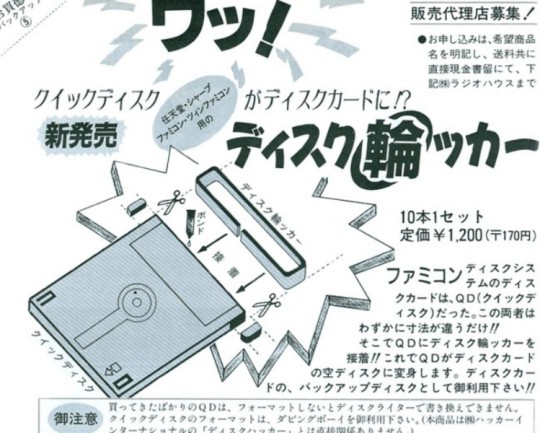

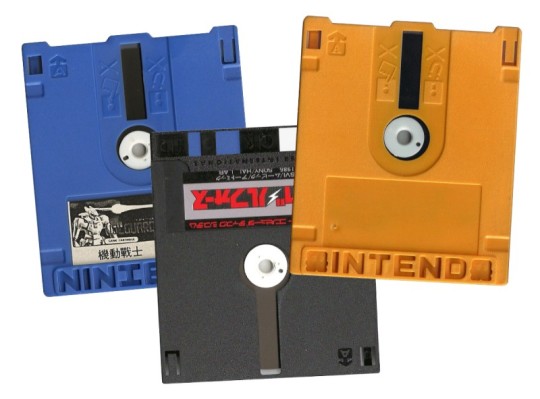

With the rental ban in full effect and piracy levels dipping, Japan’s general gaming public was feeling the sting of video game pricing. Nintendo, hearing the grumbles of its audience, researched ways of producing a cheaper option than its colorful cartridges. Enter the Famicom Disk System – a floppy disk add-on that both plugged into the top of the Famicom and sat below it. Though introducing an expensive new accessory (one that cost more than the console itself) to promote cheaper games might seem counterintuitive, Nintendo did just that in 1986.

Similar to floppy disks of the time, the games for Famicom Disk System were housed in a hard plastic shell and dubbed “Disk Cards.” Commonly produced in a brilliant yellow casing, the double-sided Disk Cards were impressed with a large NINTENDO logo at the bottom. This impression allowed Nintendo a form of physical lockout it hoped would help quell piracy. This wasn’t the case, as many clever bootleggers produced their own case molds with the proper inlays, often springing for misspellings like NINFENDO and NINIENDO to trick the Disk Drive. Regardless of their manufacturer, Disk Cards were considered too fragile by most players and poorly designed, with many prone to errors due to dust buildup.

Though games for the Disk System were cheaper, the true appeal was the ability to download new titles to endlessly-reusable Disk Cards via one of the 10,000 Famicom Disk Writer kiosks found at toy, game, and hobby shops across Japan. The process cost a paltry ¥500 (¥100 extra for an instruction sheet), or roughly a sixth the price of purchasing a new cartridge-based title. Not only could players download new games, but they could use each store’s dedicated “Disk Fax” machine to submit high scores directly to Nintendo for various tournaments. With player data in hand, Nintendo awarded tournament prizes ranging from Famicom branded stationary to gold Punch-Out!! cartridges, predating Mike Tyson’s $50,000 deal to lend his likeness to the series.

Nintendo’s hardware team was hard at work developing a different kind of add-on, one that would only work with the Disk System – 1987’s Famicom 3D System. Unlike the well-known glasses-free 3D of the 3DS, the 3D System used shutter glasses and alternate frame sequencing to create an illusion of depth. While the effect worked, the system was a substantial failure, with only six games ever produced. The most notable was Famicom Grand Prix II: 3D Hot Rally, considered by many to be the first Mario racing game and precursor to the Mario Kart series.

With Nintendo pushing all its newest first-party games to the Disk System to boost sales, the peripheral soon became the only way to play era-defining hits such as The Legend of Zelda, Castlevania, and Metroid, as well as Japan-only cult favorites like The Mysterious Murasame Castle and the Famicom Detective series. Despite their longer load times and flimsy housing, many consider Disk Card games a step above their cartridge counterparts, as the Disk System allowed for save features and a much richer audio experience. Though Nintendo would eventually return to cartridges with the Super Famicom, the Disk System was still a respectable success, with 4.4 million units sold in its four years on the market.

Famicommerce

Famicommerce

In North America, many think of the Sega Dreamcast as the first home console with online connectivity. But in Japan, every single Nintendo home console, from Famicom to Switch, had some form of internet compatibility. It all started in 1988 with the release of the infamous Famicom Modem, another clunky add-on, brimming with potential, that struggled to find a long-term audience.

The idea for the Famicom Modem came not from a desire to let players connect and play games together, but rather from something more dull – the stock market. As Famicom flourished, financial service company Nomura Securities approached Nintendo about using the system for people to check on stock prices in real-time and possibly even buy, sell, and trade stocks at home. Working closely with Nomura Securities, Uemura and his team developed a modem that worked with an online service dubbed the Famicom Network. Like the Famicom Disk System before, the Famicom Modem was plugged into the top of the console, allowing players to insert credit-card-sized cartridges for different types of transmissions. Lacking a dedicated keyboard, a special controller with a full number pad was included to help users navigate the number-centric software.

In July 1988, a test run of 1,500 prototypes produced outstanding results. With the Japanese stock bubble growing larger by the day, more and more investors were obsessed with checking market prices and making trades on the fly, an ideal situation for Nintendo. Unfortunately, this success soon evaporated when the Famicom Modem hit store shelves two months later. Nintendo was shocked to find its circuit system was unstable, leading to widespread circuit failure, and many users were less than thrilled with the modem’s cord-heavy set-up. Coupled with the inevitable burst of Japan’s stock market bubble in 1989, most were left uninterested in the add-on’s specific services – even those who owned it.

While the Famicom Modem flailed, Uemura and his team still tested the system’s gaming capabilities. Five prototype games were developed, the most prominent based on the ancient board game Go, but all were deemed failures in the end. “We were unable to realize our dream of using the modem to augment Famicom games,” Uemura told Nikkei Electronics magazine (via Glitterberri blog) in 1995. “The game would require players to be connected to the phone line for an extended period of time. If the problem of data transmission fees wasn’t enough, we were also faced with the risk of users monopolizing the phone line.”

The modem’s saving grace, outside of providing horse racing bets and results to diehard fans, was its ability to let toy and game stores share an online database. By inserting the Super Mario Club cartridge, stores could post reviews and communicate sales to one another, sharing what games were top sellers. Nintendo could also peek at this database, allowing the company to better understand the market consumer demand.

As with most of its promising technology, Nintendo toyed with releasing the Famicom Modem in the United States with a slight twist. If Japanese users could place bets on horses through the Famicom, Minneapolis-based company Control Data Corporation was confident American users could use an NES Modem to play the lottery. In 1991, with Nintendo on board, Control Data announced its plans to test a subscription model, wherein users could pay $10 a month to play all Minnesota-based lottery games via their NES. Unsurprisingly, it wasn’t long until the concept of adding unsupervised gambling to a home console aimed at children raised a few eyebrows in parent groups and the political sector – squashing dreams of an NES Modem before its initial tests ever began.

It’s easy to look back on the Famicom and focus solely on its iconic games, but looking deeper into the hardware and accessories that give it personality helps bring its influence and legacy into perspective. Like today, the Nintendo of the 1980s was willing to aim its resources towards innovative and silly concepts, striving to find the next niche in the gaming market. It stumbled from time to time, but there’s no doubt that even its failures brought a sense of wonder and joy to thousands of players along the way.

This article originally appeared in Issue 358 of Game Informer

#000#1980s#3d#add-on#America#anniversary#Article#audio#billion#Blog#board#bundle#challenge#Children#code#Collaboration#computer#connectivity#connector#consumer electronics#copyright#cpu#crash#cutting#data#Database#deal#Design#developers#development

1 note

·

View note

Text

Week 10 – Sound and Music

At last, I could get in for a more "traditional" Friday session this semester. However, (although traditional is a word that we usually wouldn't associate with something to do with one of David's classes in the context of how he runs the subject) this session was definitely more at home rather than the trips to Acmi and NGV. We opened with an excellent observation regarding the 20th-century mentality of "obsoleting" things. When the synthesizer was first made in the '60s, there was this idea that it would "replace" the piano and other keyed instruments (but the only people who had access to it were engineers; not a single composer or musician was able to use one) if you had an Atari that was now bad because the Nintendo entertainment system had now arrived. The Famicom, etc. contemporality tried to make old = bad- new =good the all-end-all equation for technology, music, Art, and many more. It is hilarious that this was the way of thinking since Westerners pride themselves on being open-minded. This mentality followed a similar suit to the Mao Zedong cultural revolution that coincidentally began in 1966. The chairman mobilized an army of students to destroy old Chinese values to further seal his fate as a dictator that stood the test of time. This mentality has carried into the 21st century, not with everyone but with some. There will be people saying, "You can't listen to your parents' music; it's old", but then other kids will say, "Maaaaannn, I was born in the wrong generation". The idea behind new technology replacing the old is a very 50s American mentality, like those popular electronic magazines trying to predict the future with pop art graphic drawings of stereotypical box-shaped robots and generic depictions of aliens. New technology doesn't necessarily replace the old; it just changes the current landscape that it exists in.

1 note

·

View note

Video

vimeo

ICONS exhibition from ◥ panGenerator on Vimeo.

ICONS

an exhibition of panGenerator

Iconic Things project by the National Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw

Icons – a set of symbols transposing the impenetrable intricacies of digital processes onto a territory accessible to our, still very much Neolithic, minds. By dragging a text file to trash, we succumb to a useful illusion. Truth be told, nothing is in transit: the trash can does not exist; even the text file does not constitute any cohesive physical entity inside any hardware. However, by performing this codified, ritual-driven dance of clicks, taps, and swipes, we conjure digital processes to bring about a happy turn of events.

Our exhibition takes a closer look at our shared cultural imaginarium of digital gestures, symbols, and artefacts, dragging them out onto a physical space, enabling audiences a direct, tactile confrontation and – also literally – a different visual perspective. We dispose of the illusive permanence of digital archives, transforming a selfie into a heap of gravel. We ask: “How much of our attention do we make an offering to tech corporations, succumbing to the ritual of ceaseless scrolling?” We perform an act of iconoclasm, deconstructing the cult, iconic Nokia 3310 – the gateway drug of our present-day smartphone intoxication. We place digital icons within baroque frames, depicting emotions associated with them. Paused by our gaze, the progress bar is our way of asking whether technological advancement goes hand in hand with the rejection of magical thinking...

As an artistic collective composed of Gen Y / millennials, we have experienced first-hand the dynamic growth of digital culture: from the soothing dial-up tones of modems to video conferencing via Zoom. This exhibition is no different: it touches upon both what is today considered vintage, such as the first Pegasus-compatible (Nintendo Entertainment System clone) video games, and what is currently trending – the up-to-the-minute impact of social media on inter-human communication.

We hope that in our exhibition the audience will find a reflection of their own digital culture experience. Even if the mirror is slightly distorting.

0 notes

Text

Wii sports resort bowling 4 players

The Mario Kart franchise is known for its fun and competitive gameplay, and Mario Kart Wii is no exception. READ ALSO » Top 10 Most Dangerous Foods in The World (2022) The latest installment in the series, Mario Kart Wii, was released in 2008 and has sold over 37 million copies worldwide, making it one of the best-selling video games of all time. The Mario Kart franchise is one of the best-selling video game franchises of all time. is still loved by many gamers today and is considered one of the best. It also had a profound impact on the video game industry, helping to popularize the side-scrolling genre and cement Nintendo as a leading video game company.ĭespite being over 30 years old, Super Mario Bros. The game was incredibly popular and spawned a number of sequels and spin-offs. is a side-scrolling platformer game that features Mario, the protagonist, as he tries to rescue Princess Toadstool from Bowser, the antagonist. The game was released in 1985 for the Nintendo Entertainment System and became an instant classic. With over 40 million copies sold, Super Mario Bros is one of the best-selling video games of all time. These classic games are as fun and addictive as ever. If you’ve never played Pokémon Red and Blue, now is the perfect time to start. They are often cited as being responsible for popularizing the role-playing game genre and inspiring a new generation of gamers. To this day, Pokémon Red and Blue remain two of the most popular video games ever made. These games were originally released in Japan in 1996 and quickly became a global phenomenon. It all started with Pokémon Red and Blue, two of the best-selling video games of all time. Today, the Pokémon franchise is worth over $50 billion dollars. If you’re looking for an adrenaline-pumping gaming experience, PUBG is definitely worth checking out. The popularity of the game has led to the release of several mobile and console versions, as well as a number of spin-offs. While the concept of battle royale games is not new, PUBG took the gaming world by storm with its immersive graphics and intense gameplay. READ ALSO » Top 10 Best Hollywood Actors in 2022 The game pits up to 100 players against each other in a last-man-standing deathmatch. PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG) is a battle royale-style video game that burst onto the scene in 2017 and quickly became one of the best-selling video games in the world. If you’re looking for a fun and easy-to-learn video game, Wii Sports is a perfect choice! 5. Wii Sports was a critical success, with many reviewers praising its graphics, gameplay, and overall fun factor. The popularity of Wii Sports can be attributed to its simple yet addictive gameplay, as well as its motion-sensing controls that allow players to physically interact with the game. Wii Sports consists of five sports games: tennis, baseball, bowling, golf, and boxing. The game was developed by Nintendo and was included in the Wii console. Since its release in 2006, Wii Sports has become one of the best-selling video games of all time. However, its popularity remains unchanged, and it is considered one of the most successful video games of all time. The game has also been controversial, due to its depiction of violence and crime. Grand Theft Auto V has been praised for its graphics, gameplay, and scale. Players can explore the open world and engage in a variety of activities, from committing crimes to pursuing businesses. The game is set in the fictional state of San Andreas and revolves around three main characters: Michael De Santa, Franklin Clinton, and Trevor Philips. The open-world action-adventure game was first released in 2013 and has since been released on several different platforms. Grand Theft Auto V is one of the best-selling video games of all time. Despite its success, the game has been criticized for its violence and for the time players can spend on it. The game has been featured in movies, television shows, and merchandise. With its popularity, Minecraft has become a cultural phenomenon. The game has been used in education and has been credited with teaching children programming and engineering concepts. READ ALSO » Old Nigerian Adverts We Will Never Forget (Top 10)

0 notes

Text

Mario kart wii custom characters hammer bro

#Mario kart wii custom characters hammer bro driver

#Mario kart wii custom characters hammer bro series

^ "Top 10 Mario Enemies More Common in Recent Games".

"Predicting Mario Kart 7's Final Characters". South San Francisco, California: Future US. Photos: The 8 most underrated videogame characters ever - CNET Reviews". "Mario-themed Spirits coming to 'Smash Ultimate' this week".

^ "Super Mario Party - Top 10 best Dice Blocks to use".

^ "Someone Did The Math On Which Dice Are The Best In Super Mario Party".

^ "Play These Cool 'Super Mario Maker 2' Levels".

"Super Mario Odyssey guide: Luncheon Kingdom all power moon locations". U Deluxe guide: Acorn Plains Star Coins".

^ Sundberg, Kelly Hudson (February 18, 2019).

^ a b "Mario 3's Angry Sun Looks Really Weird In Super Mario Maker 2".

^ Nintendo Entertainment Analysis and Development ().

^ "25 Awesome Areas In Super Mario Bros 3 Casuals Had No Idea About".

Super Mario Bros ( Nintendo Entertainment System). have been produced over the years by Nintendo this merchandise includes figures made by Jakks Pacific, Figurine, and a Plush toy. Ī variety of Mario-related merchandise depicting Hammer Bros. Whatever you do, make sure you don't underestimate these guys - when you're trapped in a room with them as small Mario without a Power-Up in sight, they can be downright frightening". counterparts throw (huge shocker!) boomerangs. were listed as second in Nintendo 3DS Daily's list of the top ten enemies more common in recent games, claiming "Super Mario World already kind of screwed them over by sticking them on winged blocks and having them appear only ever so often, but they've technically been absent from the platformers for two whole console generations!" It was also described by IGN's Audrey Drake as one of the best Mario enemies, stating that "Hammer Bros., naturally, throw hammers, while their Boomerang Bro. besides Bowser himself." The Hammer Bros. as one of the characters they wanted for the then-unreleased Mario Kart 7, saying that the "terrifying twin turtles were the most devious and dangerous foes in the original Super Mario Bros. as one of the things that they love to hate, citing the difficulty involved in defeating or avoiding them. as the fifth best Mario enemy, citing the difficulty involved in defeating them.

#Mario kart wii custom characters hammer bro series

from other enemies in the series who would merely wander aimlessly in the level. were named as one of the eight most underrated video game characters by CNET editor Nate Lanxon, who contrasted the duo in the first Super Mario Bros. usually appear in pairs and reprise their role as Bowser's minions, trying to stop Mario and Luigi. In the Mario role-playing games, the Hammer Bros. 3 television series, as well as in printed media such as Nintendo Comics System and Nintendo Adventure Books. Super Show! and The Adventures of Super Mario Bros.

#Mario kart wii custom characters hammer bro driver

Hammer Bro officially made its Mario Kart debut as a playable driver in Mario Kart Tour. Ultimate as an Assist Trophy and an Adventure Mode enemy. for Nintendo 3DS and Wii U and Super Smash Bros. appeared in most of the Mario spin-off games, such as Super Mario RPG, the Paper Mario series, the Mario & Luigi series, the Mario Party series, even as a playable character in Mario Party 8 and Super Mario Party, Dance Dance Revolution Mario Mix, the Mario sports games and Super Princess Peach. They reappeared in Super Mario Odyssey, where Mario can use their powers for the first time in 3D and on Super Mario Maker/ Super Mario Maker 2. appeared in a 3D Mario game), Super Mario 3D Land, Super Mario 3D World, New Super Mario Bros. Wii (which introduced the Ice Bro., a cold-weather counterpart to the Fire Bro.), Super Mario Galaxy 2 (the first time that the Hammer Bro. was absent again from Super Mario World, two new subspecies were added, the Amazing Flyin' Hammer Brother, and the Sumo Brother (later known as the Sumo Bro.), both of which would later appear in New Super Mario Bros., New Super Mario Bros. Suit, which granted Mario and Luigi the ability to throw hammers of their own and also conferred immunity against fire attacks while ducking. were added, including the Boomerang Bro., whose boomerangs returned to them, the Fire Bro., who spat fireballs, and the Sledge Bro., who was considerably larger and could cause an earthquake when he landed from a jump. 3, in which they behaved in the same way as they did in the original game. Although they were absent in Super Mario Bros. They later appeared in its sequel, Super Mario Bros.: The Lost Levels, where they were found more commonly. In the game, they were usually found in pairs. first appeared in Super Mario Bros., where they would jump from platforms and throw hammers at Mario or Luigi.

0 notes

Text

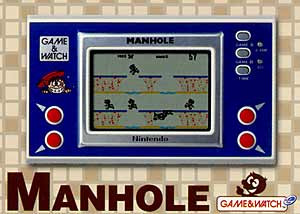

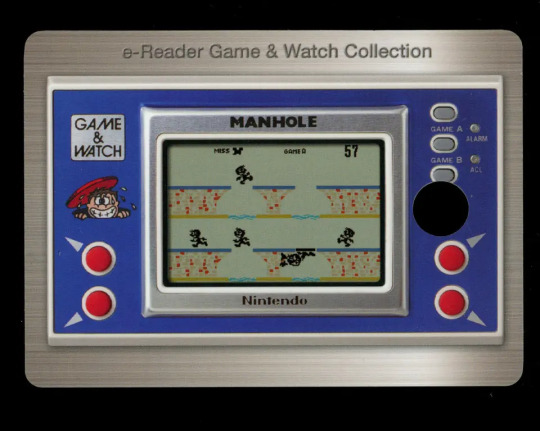

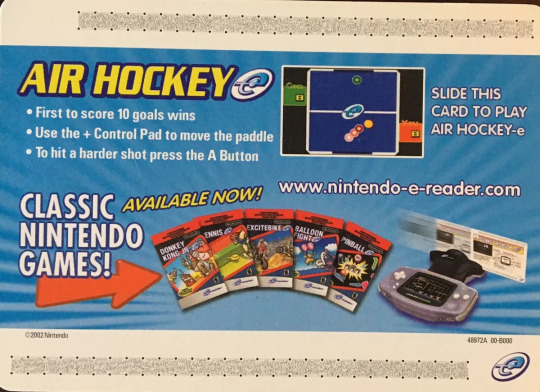

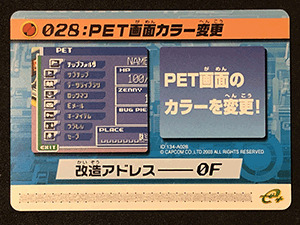

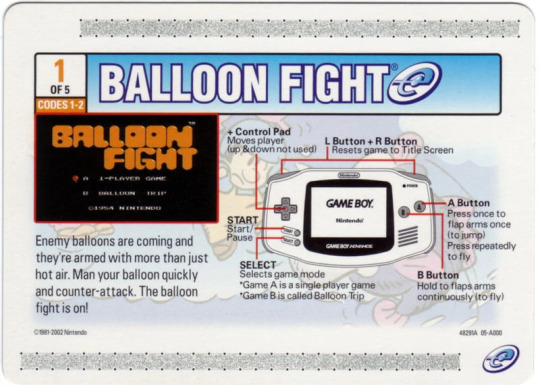

e-Reader Cards

Video game hardware on video game hardware post! I know this is kinda outside the scope of the project but I love it and this is my blog so here you go:

from https://www.pojo.com/Features/May2002/6-05-Ecard.html

From https://archive.org/details/1st-place-kirby

From https://aucview.aucfan.com/yahoo/k189211384/

From http://sunmiguere.web.fc2.com/megaman_exe4_remodeling_card_part1.html

From http://sunmiguere.web.fc2.com/megaman_exe4_remodeling_card_part3.html

Those all are screenshots of this screen which has a Game Boy Advance Game Link Cable

From https://megaman.fandom.com/wiki/Plug-in_PET

From https://nookipedia.com/wiki/E-Reader_card/Promotional_(Doubutsu_no_Mori_e%2B)

From https://balloon-fight.fandom.com/wiki/Balloon_Fight-e

All the NES ones have that GBA picture

Uncited images are from eBay (listings get deleted after a few months so no point in linking)

#Nintendo e-Reader cards#Depicted by: Nintendo e-Reader cards#Depicting: Game & Watch Manhole#Depicting: Game Boy Advance#Depicting: Nintendo e-Reader#Depicting: Nintendo e-Reader cards#Depicting: Game Boy Advance Game Link Cable#Depicting: Derivative#Derivative: Nintendo GameCube#Depicting: Nintendo Entertainment System#Depicting: Nintendo Entertainment System Controller

0 notes

Link

Much like his infamous father, the aesthetic of Alucard has changed tremendously since Castlevania’s start in the 1980s—yet certain things about him never change at all. He began as the mirror image of Dracula; a hark back to the days of masculine Hammer Horror films, Christopher Lee, and Bela Lugosi. Then his image changed dramatically into the androgynous gothic aristocrat most people know him as today. This essay will examine Alucard’s design, the certain artistic and social trends which might have influenced it, and how it has evolved into what it is now.

☽ Read the full piece here or click the read more for the text only version ☽

INTRODUCTION

Published in 2017, Carol Dyhouse’s Heartthrobs: A History of Women and Desire examines how certain cultural trends can influence what women may find attractive or stimulating in a male character. By using popular archetypes such as the Prince Charming, the bad boy, and the tall dark handsome stranger, Dyhouse seeks to explain why these particular men appeal to the largest demographic beyond mere superfluous infatuation. In one chapter titled “Dark Princes, Foreign Powers: Desert Lovers, Outsiders, and Vampires”, she touches upon the fascination most audiences have with moody and darkly seductive vampires. Dyhouse exposits that the reason for this fascination is the inherent dangerous allure of taming someone—or something—so dominating and masculine, perhaps even evil, yet hides their supposed sensitivity behind a Byronic demeanour.

This is simply one example of how the general depiction of vampires in mainstream media has evolved over time. Because the concept itself is as old as the folklore and superstitions it originates from, thus varying from culture to culture, there is no right or wrong way to represent a vampire, desirable or not. The Caribbean Soucouyant is described as a beautiful woman who sheds her skin at night and enters her victims’ bedrooms disguised as an aura of light before consuming their blood. In Ancient Roman mythology there are tales of the Strix, an owl-like creature that comes out at night to drink human blood until it can take no more. Even the Chupacabra, a popular cryptid supposedly first spotted in Puerto Rico, has been referred to as being vampiric because of the way it sucks blood out of goats, leaving behind a dried up corpse.

However, it is a rare thing to find any of these vampires in popular media. Instead, most modern audiences are shown Dyhouse’s vampire: the brooding, masculine alpha male in both appearance and personality. A viewer may wish to be with that character, or they might wish to become just like that character.

This sort of shift in regards to creating the “ideal” vampire is most evident in how the image of Dracula has been adapted, interpreted, and revamped in order to keep up with changing trends. In Bram Stoker’s original 1897 novel of the same name, Dracula is presented as the ultimate evil; an ancient, almost grotesque devil that ensnares the most unsuspecting victims and slowly corrupts their innocence until they are either subservient to him (Renfield, the three brides) or lost to their own bloodlust (Lucy Westenra). In the end, he can only be defeated through the joined actions of a steadfast if not ragtag group of self-proclaimed vampire hunters that includes a professor, a nobleman, a doctor, and a cowboy. His monstrousness in following adaptations remains, but it is often undercut by attempts to give his character far more pathos than the original source material presents him with. Dracula has become everything: a monster, a lover, a warrior, a lonely soul searching for companionship, a conquerer, a comedian, and of course, the final boss of a thirty-year-old video game franchise.

Which brings us to the topic of this essay; not Dracula per say, but his son. Even if someone has never played a single instalment of Castlevania or watched the ongoing animated Netflix series, it is still most likely that they have heard of or seen the character of Alucard through cultural osmosis thanks to social media sites such as Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, and the like. Over the thirty-plus years in which Castlevania has remained within the public’s consciousness, Alucard has become one of the most popular characters of the franchise, if not the most popular. Since his debut as a leading man in the hit game Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, he has taken his place beside other protagonists like Simon Belmont, a character who was arguably the face of Castlevania before 1997, the year in which Symphony of the Night was released. Alucard is an iconic component of the series and thanks in part to the mainstream online streaming service Netflix, he is now more present in the public eye than ever before whether through official marketing strategies or fanworks.

It is easy to see why. Alucard’s backstory and current struggles are quite similar to the defining characteristics of the Byronic hero. Being the son of the human doctor Lisa Țepeș, a symbol of goodness and martyrdom in all adaptations, and the lord of all vampires Dracula, Alucard (also referred to by his birth name Adrian Fahrenheit Țepeș) feels constantly torn between the two halves of himself. He maintains his moralistic values towards protecting humanity, despite being forced to make hard decisions, and despite parts of humanity not being kind to him in turn, yet is always tempted by his more monstrous inheritance. The idea of a hero who carries a dark burden while aspiring towards nobility is something that appeals to many audiences. We relate to their struggles, cheer for them when they triumph, and share their pain when they fail. Alucard (as most casual viewers see him) is the very personification of the Carol Dyhouse vampire: mysterious, melancholic, dominating, yet sensitive and striving for compassion. Perceived as a supposed “bad boy” on the surface by people who take him at face value, yet in reality is anything but.

Then there is Alucard’s appearance, an element that is intrinsically tied to how he has been portrayed over the decades and the focus of this essay. Much like his infamous father, the aesthetic of Alucard has changed tremendously since Castlevania’s start in the 1980s—yet certain things about him never change at all. He began as the mirror image of Dracula; a hark back to the days of masculine Hammer Horror films, Christopher Lee, and Bela Lugosi. Then his image changed dramatically into the androgynous gothic aristocrat most people know him as today. This essay will examine Alucard’s design, the certain artistic and social trends which might have influenced it, and how it has evolved into what it is now. Parts will include theoretical, analytical, and hypothetical stances, but it’s overall purpose is to be merely observational.

--

What is Castlevania?

We start this examination at the most obvious place, with the most obvious question. Like all franchises, Castlevania has had its peaks, low points, and dry spells. Developed by Konami and directed by Hitoshi Akamatsu, the first instalment was released in 1986 then distributed in North America for the Nintendo Entertainment System the following year. Its pixelated gameplay consists of jumping from platform to platform and fighting enemies across eighteen stages all to reach the final boss, Dracula himself. Much like the gameplay, the story of Castlevania is simple. You play as Simon Belmont; a legendary vampire hunter and the only one who can defeat Dracula. His arsenal includes holy water, axes, and throwing daggers among many others, but his most important weapon is a consecrated whip known as the vampire killer, another iconic staple of the Castlevania image.

Due to positive reception from critics and the public alike, Castlevania joined other titles including Super Mario Bros., The Legend of Zelda, and Mega Man as one of the most defining video games of the 1980s. As for the series itself, Castlevania started the first era known by many fans and aficionados as the “Classicvania” phase, which continued until the late 1990s. It was then followed by the “Metroidvania” era, the “3-D Vania” era during the early to mid 2000s, an reboot phase during the early 2010s, and finally a renaissance or “revival” age where a sudden boom in new or re-released Castlevania content helped boost interest and popularity in the franchise. Each of these eras detail how the games changed in terms of gameplay, design, and storytelling. The following timeline gives a general overview of the different phases along with their corresponding dates and instalments.

Classicvania refers to Castlevania games that maintain the original’s simplicity in gameplay, basic storytelling, and pixelated design. In other words, working within the console limitations of the time. They are usually side-scrolling platformers with an emphasis on finding hidden objects and defeating a variety of smaller enemies until the player faces off against the penultimate boss. Following games like Castlevania 2: Simon’s Quest and Castlevania 3: Dracula’s Curse were more ambitious than their predecessor as they both introduced new story elements that offered multiple endings and branching pathways. In Dracula’s Curse, there are four playable characters each with their own unique gameplay. However, the most basic plot of the first game is present within both of these titles . Namely, find Dracula and kill Dracula. Like with The Legend of Zelda’s Link facing off against Ganon or Mario fighting Bowser, the quest to destroy Dracula is the most fundamental aspect to Castlevania. Nearly every game had to end with his defeat. In terms of gameplay, it was all about the journey to Dracula’s castle.

As video games grew more and more complex leading into the 1990s, Castlevania’s tried and true formula began to mature as well. The series took a drastic turn with the 1997 release of Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, a game which started the Metroidvania phase. This not only refers to the stylistic and gameplay changes of the franchise itself, but also refers to an entire subgenre of video games. Combining key components from Castlevania and Nintendo’s popular science fiction action series Metroid, Metroidvania games emphasize non-linear exploration and more traditional RPG elements including a massive array of collectable weapons, power-ups, character statistics, and armor. Symphony of the Night pioneered this trend while later titles like Castlevania: Circle of the Moon, Castlevania: Harmony of Dissonance and Castlevania: Aria of Sorrow solidified it. Nowadays, Metroidvanias are common amongst independent developers while garnering critical praise. Hollow Knight, Blasphemous, and Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night are just a few examples of modern Metroidvanias that use the formula to create familiar yet still distinct gaming experiences.

Then came the early to mid 2000s and many video games were perfecting the use of 3-D modelling, free control over the camera, and detailed environments. Similar to what other long-running video game franchises were doing at the time, Castlevania began experimenting with 3-D in 1999 with Castlevania 64 and Castlevania: Legacy of Darkness, both developed for the Nintendo 64 console. 64 received moderately positive reviews while the reception for its companion was far more mixed, though with Nintendo 64’s discontinuation in 2002, both games have unfortunately fallen into obscurity.

A year later, Castlevania returned to 3-D with Castlevania: Lament of Innocence for the Playstation 2. This marked Koji Igarashi’s first foray into 3-D as well as the series’ first ever M-rated instalment. While not the most sophisticated or complex 3-D Vania (or one that manages to hold up over time in terms of graphics), Lament of Innocence was a considerable improvement over 64 and Legacy of Darkness. Other 3-D Vania titles include Castlevania: Curse of Darkness, Castlevania: Judgment, and Castlevania: The Dracula X Chronicles for the PSP, a remake of the Classicvania game Castlevania: Rondo of Blood which merged 3-D models, environments, and traditional platforming mechanics emblematic of early Castlevania. It is important to note that during this particular era, there were outliers to the changing formula that included Castlevania: Portrait of Ruin and Castlevania: Order of Ecclesia, both games which added to the Metroidvania genre.

Despite many of the aforementioned games becoming cult classics and fan favourites, this was an era in which Castlevania struggled to maintain its relevance, confused by its own identity according to most critics. Attempts to try something original usually fell flat or failed to resonate with audiences and certain callbacks to what worked in the past were met with indifference.

By the 2010s, the Castlevania brand changed yet again and stirred even more division amongst critics, fans, and casual players. This was not necessarily a dark age for the franchise but it was a strange age; the black sheep of Castlevania. In 2010, Konami released Castlevania: Lords of Shadow, a complete reboot of the series with new gameplay, new characters, and new lore unrelated to previous instalments. The few elements tying it to classic Castlevania games were recurring enemies, platforming, and the return of the iconic whip used as both a weapon and another means of getting from one area to another. Other gameplay features included puzzle-solving, exploration, and hack-and-slash combat. But what makes Lords of Shadow so divisive amongst fans is its story. The player follows Gabriel Belmont, a holy warrior on a quest to save his deceased wife’s soul from Limbo. From that basic plot point, the storyline diverges immensely from previous Castlevania titles, becoming more and more complicated until Gabriel makes the ultimate sacrifice and turns into the very monster that haunted other Belmont heroes for centuries: Dracula. While a dark plot twist and a far cry from the hopeful endings of past games, the concept of a more tortured and reluctant Dracula who was once the hero had already been introduced in older Dracula adaptations (the Francis Ford Coppola directed Dracula being a major example of this trend in media).

Despite strong opinions on how much the story of Lords of Shadow diverged from the original timeline, it was positively received by critics, garnering an overall score of 85 on Metacritic. This prompted Konami to continue with the release of Castlevania: Lords of Shadow—Mirror of Fate and Castlevania: Lords of Shadow 2. Mirror of Fate returned to the series’ platforming and side-scrolling roots with stylized 3-D models and cutscenes. It received mixed reviews, as did its successor Lords of Shadow 2. While Mirror of Fate felt more like a classic stand-alone Castlevania with Dracula back as its main antagonist, the return of Simon Belmont, and the inclusion of Alucard, Lords of Shadow 2 carried over plot elements from its two predecessors along with new additions, turning an already complicated story into something more contrived.

Finally, there came a much needed revival phase for the franchise. Netflix’s adaptation of Castlevania animated by Powerhouse Animation Studios based in Austen, Texas and directed by Samuel Deats and co-directed by Adam Deats aired its first season during July 2017 with four episodes. Season two aired in October 2018 with eight episodes followed by a ten episode third season in March 2020. Season four was announced by Netflix three weeks after the release of season three. The show combines traditional western 2-D animation with elements from Japanese anime and is a loose adaptation of Castlevania 3: Dracula’s Curse combined with plot details from Castlevania: Curse of Darkness, Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, and original story concepts. But the influx of new Castlevania content did not stop with the show. Before the release of season two, Nintendo announced that classic protagonists Simon Belmont and Richter Belmont would join the ever-growing roster of playable characters in their hit fighting game Super Smash Bros. Ultimate. With their addition also came the inclusion of iconic Castlevania environments, music, weapons, and supporting characters like Dracula and Alucard.

During the year-long gap between seasons two and three of the Netflix show, Konami released Castlevania: Grimoire of Souls, a side-scrolling platformer and gacha game for mobile devices. The appeal of Grimoire of Souls is the combination of popular Castlevania characters each from a different game in the series interacting with one another along with a near endless supply of collectable weapons, outfits, power-ups, and armor accompanied by new art. Another ongoing endeavor by Konami in partnership with Sony to bring collective awareness back to one of their flagship titles is the re-releasing of past Castlevania games. This began with Castlevania: Requiem, in which buyers received both Symphony of the Night and Rondo of Blood for the Playstation 4 in 2018. This was followed the next year with the Castlevania Anniversary Collection, a bundle that included a number of Classicvania titles for the Playstation 4, Xbox One, Steam, and Nintendo Switch.

Like Dracula, the Belmonts, and the vampire killer, one other element tying these five eras together is the presence of Alucard and his various forms in each one.

--

Masculinity in 1980s Media

When it comes to media and various forms of the liberal arts be it entertainment, fashion, music, etc., we are currently in the middle of a phenomenon known as the thirty year cycle. Patrick Metzgar of The Patterning describes this trend as a pop cultural pattern that is, in his words, “forever obsessed with a nostalgia pendulum that regularly resurfaces things from 30 years ago”. Nowadays, media seems to be fixated with a romanticized view of the 1980s from bold and flashy fashion trends, to current music that relies on the use of synthesizers, to of course visual mass media that capitalizes on pop culture icons of the 80s. This can refer to remakes, reboots, and sequels; the first cinematic chapter of Stephen King’s IT, The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance, and both Ghostbusters remakes are prime examples—but the thirty year cycle can also include original media that is heavily influenced or oversaturated with nostalgia. Netflix’s blockbuster series Stranger Things is this pattern’s biggest and most overt product.

To further explain how the thirty year cycle works with another example, Star Wars began as a nostalgia trip and emulation of vintage science fiction serials from the 1950s and 60s, the most prominent influence being Flash Gordon. This comparison is partially due to George Lucas’ original attempts to license the Flash Gordon brand before using it as prime inspiration for Star Wars: A New Hope and subsequent sequels. After Lucas sold his production company Lucasfilms to Disney, three more Star Wars films were released, borrowing many aesthetic and story elements from Lucas’ original trilogy while becoming emulations of nostalgia themselves.

The current influx of Castlevania content could be emblematic of this very same pattern in visual media, being an 80s property itself, but what do we actually remember from the 1980s? Thanks to the thirty year cycle, the general public definitely acknowledges and enjoys all the fun things about the decade. Movie theatres were dominated by the teen flicks of John Hughes, the fantasy genre found a comeback due to the resurgence of J.R.R. Tolkien’s classic works along with the tabletop role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons, and people were dancing their worries away to the songs of Michael Jackson, Whitney Houston, and Madonna. Then there were the things that most properties taking part in the thirty year cycle choose to ignore or gloss over, with some exceptions. The rise of child disappearances, prompting the term “stranger danger”, the continuation of satanic panic from the 70s which caused the shutdown and incarceration of hundreds of innocent caretakers, and the deaths of thousands due to President Reagan’s homophobia, conservatism, and inability to act upon the AIDS crisis.

The 1980s also saw a shift in masculinity and how it was represented towards the public whether through advertising, television, cinema, or music. In M.D. Kibby’s essay Real Men: Representations of Masculinity in 80s Cinema, he reveals that “television columns in the popular press argued that viewers were tired of liberated heroes and longed for the return of the macho leading man” (Kibby, 21). Yet there seemed to be a certain “splitness” to the masculine traits found within fictional characters and public personas; something that tried to deconstruct hyper-masculinity while also reviling in it, particularly when it came to white, cisgendered men. Wendy Somerson further describes this dichotomy: “The white male subject is split. On one hand, he takes up the feminized personality of the victim, but on the other hand, he enacts fantasies of hypermasculinized heroism” (Somerson, 143). Somerson explains how the media played up this juxtaposition of “soft masculinity”, where men are portrayed as victimized, helpless, and childlike. In other words, “soft men who represent a reaction against the traditional sexist ‘Fifties man’ and lack a strong male role model” (Somerson, 143). A sort of self-flagellation or masochism in response to the toxic and patriarchal gender roles of three decades previous. Yet this softening of male representation was automatically seen as traditionally “feminine” and femininity almost always equated to childlike weakness. Then in western media, there came the advent of male madness and the fetishization of violent men. Films like Scarface, Die Hard, and any of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s filmography helped to solidify the wide appeal of these hyper-masculine and “men out of control” tropes which were preceded by Martin Scorcese’s critical and cult favourite Taxi Driver.

There were exceptions to this rule; or at the very least attempted exceptions that only managed to do more harm to the concept of a feminized man while also doubling down on the standard tropes of the decade. One shallow example of this balancing act between femininity and masculinity in 80s western media was the hit crime show Miami Vice and Sonny, a character who is entirely defined by his image. In Kibby’s words, “he is a beautiful consumer image, a position usually reserved for women; and he is in continual conflict with work, that which fundamentally defines him as a man” (Kibby, 21). Therein lies the problematic elements of this characterization. Sonny’s hyper-masculine traits of violence and emotionlessness serve as a reaffirmation of his manufactured maleness towards the audience.

Returning to the subject of Schwarzenegger, his influence on 80s media that continued well into the 90s ties directly to how fantasy evolved during this decade while also drawing upon inspirations from earlier trends. The most notable example is his portrayal of Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian in the 1982 film directed by John Milius. Already a classic character from 1930s serials and later comic strips, the movie (while polarizing amongst critics who described it as a “psychopathic Star Wars, stupid and stupefying”) brought the iconic image of a muscle-bound warrior wielding a sword as half-naked women fawn at his feet back into the collective consciousness of many fantasy fans. The character and world of Conan romanticizes the use of violence, strength, and pure might in order to achieve victory. This aesthetic of hyper-masculinity, violence, and sexuality in fantasy art was arguably perfected by the works of Frank Frazetta, a frequent artist for Conan properties. The early Castlevania games drew inspiration from this exact aesthetic for its leading hero Simon Belmont and directly appropriated one of Frazetta’s pieces for the cover of the first game.

--

Hammer Horror & Gender

Conan the Barbarian, Frank Frazetta, and similar fantasy icons were just a few influences on the overall feel of 80s Castlevania. Its other major influence harks back to a much earlier and far more gothic trend in media. Castlevania director Hitoshi Akamatsu stated that while the first game was in development, they were inspired by earlier cinematic horror trends and “wanted players to feel like they were in a classic horror movie”. This specific influence forms the very backbone of the Castlevania image. Namely: gothic castles, an atmosphere of constant uncanny dread, and a range of colourful enemies from Frankenstein’s Monster, the Mummy, to of course Dracula. The massive popularity and recognizability of these three characters can be credited to the classic Universal Pictures’ monster movies of the 1930s, but there was another film studio that put its own spin on Dracula and served as another source of inspiration for future Castlevania properties.

The London-based film company Hammer Film Productions was established in 1934 then quickly filed bankruptcy a mere three years later after their films failed to earn back their budget through ticket sales. What saved them was the horror genre itself as their first official title under the ‘Hammer Horror’ brand The Curse of Frankenstein starring Hammer regular Peter Cushing was released in 1957 to enormous profit in both Britain and overseas. With one successful adaptation of a horror legend under their belt, Hammer’s next venture seemed obvious. Dracula (also known by its retitle Horror of Dracula) followed hot off the heels of Frankenstein and once again starred Peter Cushing as Professor Abraham Van Helsing, a much younger and more dashing version of his literary counterpart. Helsing faces off against the titular fanged villain, played by Christopher Lee, whose portrayal of Dracula became the face of Hammer Horror for decades to come.