#De Natura animalium

Text

Rating cows from Medieval manuscripts because I fucking love cows

I love cows and I love Medieval manuscripts. Is there something else I have to say to justify this post? I hope not.

Ashmole Bestiary. England, early 13th century.

This is a cow for sure. I love her soft lineart - the artist knew what he was doing. Her reddish coat is Accurate, but she has curly hair, for some reason. This cow doesn't seem ready for the hardships of motherhood. She looks worried that her calf misses her udder completely, chomping on something that should definitely not be chomped. I empathize with her, to some extent.

9/10

Ortus sanitatis. Germany, 15th century

A very skinny cow. She might be very young. This is probably the first time she's been milked, you can see from her face that she does not know what to expect, but she definitely does not like it. And tbh, I myself would not trust that little, lingering hand. However, I don't like that she's so skinny. Cows should be round, friendly and huggable. Her owners might be Poor, but Grass Is Free, you know? Let her eat something!

6/10 because it's not her fault.

BL Harley 4751, f. 23. England, 13th century.

A very common rendition of a cow. I have seen at least two other illustrations like this one. She is Accurate, but her horns are red too. That was lazy, my dear artist. I love her fluffy tail and her tongue too. Cows have beautiful tongues. However, she does not look soft, but very sleek. I give her an extra point for that 'vacca' in the caption - it makes everything 1000 times better. 'Vacca' is a very funny word in Italian.

8/10

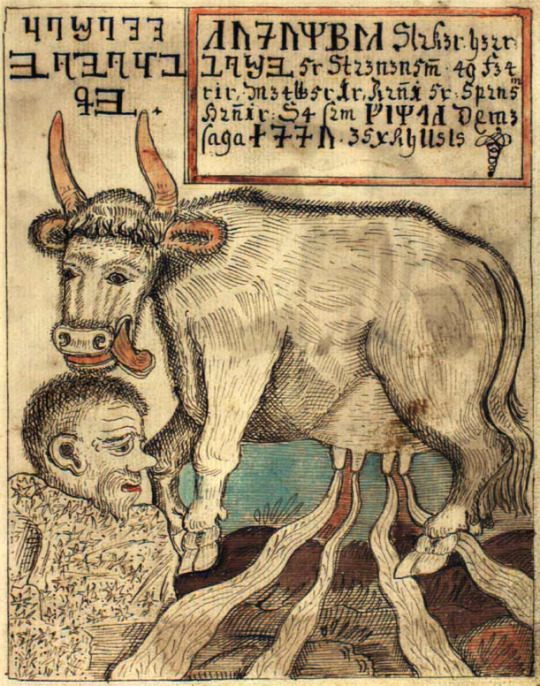

SÁM 66. Iceland, 18th century

This cow is technically not Medieval, but she gets a free pass because I know her personally. Her name is Auðumbla. I usually love Auðumbla, but here she looks like she's pulling a gigantic prank on poor Búri by spilling all her milk all over the universe, and he doesn't seem to appreciate it. Bad Auðumbla. Apart from this, she looks Soft.

6/10

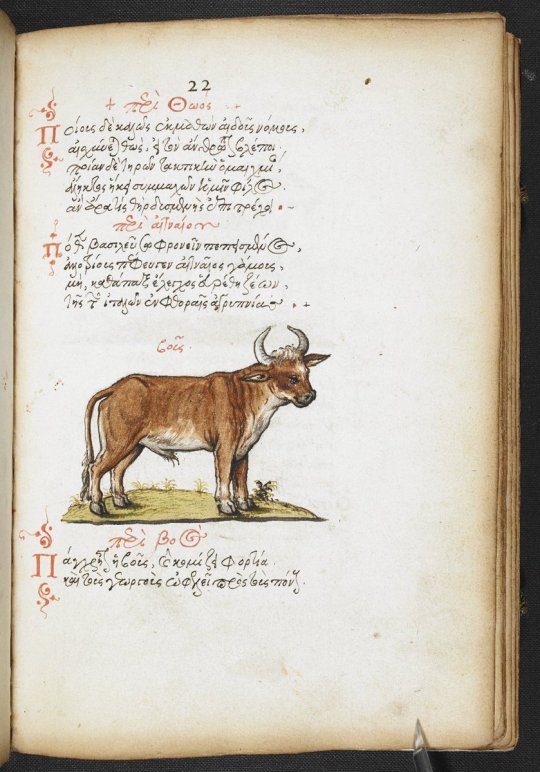

De natura animalium. Italy, 15th century.

If Auðumbla was not Medieval, this bad boy here is not a Cow. He is a Bull. However, if I was driving past a field I would still point at him and scream "Cow!!" to my mum, so he too gets a free pass. I love him. He has kind, expressive eyes. He seems very polite as if he would let you cross the street without honking at you. He also looks squishable but firm. He is probably the most beloved animal on the farm. I love you, Kind Bull.

10/10

Bohun Psalter and Hours. England, 14th century

This cow is literally me if I was a Cow. Wrapped in a blanket, with a book and flowers all around. This cow knows how to read. Cows should not be able to read, but I guess she followed her dreams and never gave up on them. Her eyes are so expressive, and kind. I cannot express the range of emotions this little Scholar Cow evokes in me. She also has a good sense of style. Good job, little Cow!

1000/10

LJS 361. Naples, 14th century

Not sure what this is supposed to be. A cow? A horse? A 'corse'? Anyway, this looks like a little push cart with a stuffed animal on top. Really doesn't look like a cow. And why is she on a leash? Or maybe it is her who's keeping that square-headed creature on a leash? Is it, perhaps, her pet? In that case, we love our independent queen. But I still have to say: I have no idea what this is. Sorry, weird-looking maybe-cow.

1/10

---

This was all for today! I hope you enjoyed my little ranking of the Medieval beauties. Let me know which one of these is your favourite, pls I'd love to know.

To be completely transparent, I was inspired to do this by @cuties-in-codices 's beautiful posts on weird creatures in manuscripts. I love your blog so much.

Ha det bra, my fellow friends!

#manuscripts#medievalism#medieval#medieval history#middle ages#cows#animals#ratings#manuscript#i fucking love cows

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

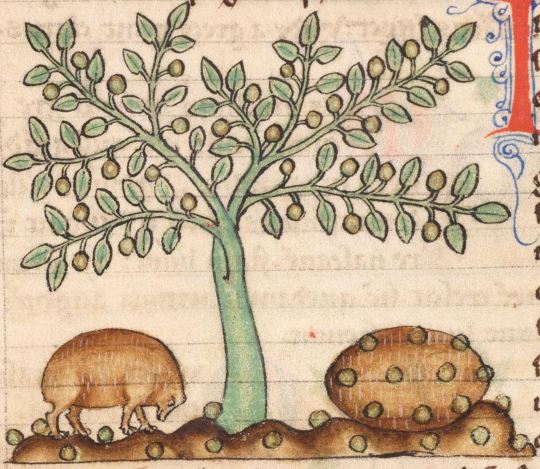

It's #HedgehogWeek! 🦔 (+ #ManuscriptMonday)

The hedgehog has a fun medieval bestiary story - it knocks down fruit then rolls around and collects them on its spines to bring home to its family. Fruit kebobs to go!

1. BM Douai MS 711 (De Natura animalium) f. 23v

2. BnF fr.14969 (Bestiaire of Guillaume le Clerc) f. 21v

3. British Library Royal MS 12 F XIII (Rochester Bestiary) f. 45r

#medieval art#European art#medieval bestiary#medieval manuscripts#illuminated manuscripts#book illustration#bestiary#medieval miniature#painting#Hedgehog Week#Hedgehog Awareness Week#animal holiday#hedgehog#hedgehogs#animals in art#Manuscript Monday

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ctesias got his information while living in Persia. Unicorns ,or more likely, winged bulls, appear in reliefs at the ancient Persian capital of Persepolis in Iran.[8] Aristotle must be following Ctesias when he mentions two one-horned animals, the oryx (a kind of antelope) and the so-called "Indian ass" (ἰνδικὸς ὄνος).[9][10] Antigonus of Carystus also wrote about the one-horned "Indian ass".[11] Strabo says that in the Caucasus there were one-horned horses with stag-like heads.[12] Pliny the Elder mentions the oryx and an Indian ox (perhaps a greater one-horned rhinoceros) as one-horned beasts, as well as "a very fierce animal called the monoceros which has the head of the stag, the feet of the elephant, and the tail of the boar, while the rest of the body is like that of the horse; it makes a deep lowing noise, and has a single black horn, which projects from the middle of its forehead, two cubits [900 mm, 35 inches] in length."[13] In On the Nature of Animals (Περὶ Ζῴων Ἰδιότητος, De natura animalium), Aelian, quoting Ctesias, adds that India produces also a one-horned horse (iii. 41; iv. 52),[14][15] and says (xvi. 20)[16] that the monoceros (μονόκερως) was sometimes called cartazonos (καρτάζωνος), which may be a form of the Arabic karkadann, meaning 'rhinoceros'.

Cosmas Indicopleustes, a merchant of Alexandria who lived in the 6th century, made a voyage to India and subsequently wrote works on cosmography. He gives a description of a unicorn based on four brass figures in the palace of the King of Ethiopia. He states, from report, that "it is impossible to take this ferocious beast alive; and that all its strength lies in its horn. When it finds itself pursued and in danger of capture, it throws itself from a precipice, and turns so aptly in falling, that it receives all the shock upon the horn, and so escapes safe and sound"

THE ONE-HORNED INDIAN. ASS.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

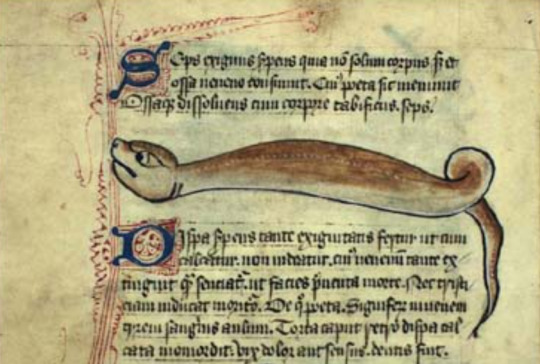

The Dipsas [Greek mythology; medieval European folklore]

Aulus of Tyrrhenia reportedly met his end when stepping on one of these creatures. The Dipsas, also called Dipsa, is an incredibly tiny snake (smaller than a common viper), meaning victims are unlikely to notice it. It is very, very venomous, in fact it is said that if you’re bitten by a Dipsas, you’ll die before you feel the bite. The serpent has a white skin, though its tail is adorned with two black stripes. It supposedly lives in Libya, where it makes its home in dry, sandy habitats.

According to Marcus Annaeus Lucanus, no visible bitemark can be seen in the skin after one of these creatures strikes. He described the symptoms as follows: the body dries out, the victim’s tongue is set aflame (presumably in the sense that the tongue hurts, not that it is literally on fire) and sweat immediately dries up. The victim desperately tries to find water, but all the water of the Nile is not enough to quench the thirst of someone bitten by a Dipsas, and the victim will drop dead.

Supposedly, this is because the venom of a Dipsa is a curious substance that quickly absorbs moisture when it is introduced into the victim’s body. This peculiar characteristic is also where the animal’s name comes from, as it translates roughly to “thirst-provoker”.

According to Aelianus, who was quoting Sophocles, the creature is connected with a myth. When the titan Prometheus stole fire from the gods, mighty Zeus was furious. He told humans that those who could identify the thief, or provide other useful information about the crime, would be rewarded with a magical drug that would prevent aging, making those who took it immortal. One person gladly accepted this reward and identified Prometheus as the one who brought fire to the humans. True to his word, Zeus bestowed onto him a chest containing the drug. Because it was heavy, the human attached the precious cargo to the back of his donkey. But it was a particularly hot summer day, and the animal was soon exhausted and thirsty, so it sought a source of water to quench its thirst. As luck would have it, there was a fresh spring close by, but it was guarded by a tiny snake, who claimed the water as its own and refused to let the donkey drink. The ass, tormented by thirst, dropped the heavy container that it was carrying, to pay for the water. And the snake accepted this exchange and became young again while the mammal was drinking. Along with the gift of youth, however, the snake also obtained the donkey’s thirst, which it passes on to those it bites.

Sources:

The Aberdeen bestiary, 12th century, which you can read here.

Pharsalia, by Marcus Lucanus, book IX, which you can read here.

De Natura Animalium, by Claudius Aelianus, book VI, chapter 51, which you can read here.

MS Bodl 764 bestiary, Bodleian Library, 13th century, which you can read here.

(image source 1: MS Bodl 764 bestiary, Bodleian Library, 13th century)

(image source 2: medieval Ann Walsh bestiary from the Kongelige Bibliotek)

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

ough this illustration of a bear and its cub is making me Feel Things....

(Bibliothèque Municipale de Douai, Ms. 711 (De Natura animalium), folio 10v)

#this is the last one I promise I just am on the verge of tears looking at this fucking bear#medievalposting#if bear not friend why friend shaped

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Life, as it exists in this corner of the universe, in the form of men, animals and plants, is to be found, let us suppose in a high form in the solar and stellar regions. Rather than think that so many stars and parts of the heavens are uninhabited and that this home celestial body of ours alone is peopled – and that with beings perhaps of an inferior type – we will suppose that in every region there are inhabitants, differing in nature by rank and all owing their origin to God, who is the center and circumference of all stellar regions… Therefore, the inhabitants of other stars — of whatever sort these inhabitants might be – bear no comparative relationship to the inhabitants of the Earth (istius mundi). That is true even if, with respect to the goal of the universe, that entire region bears to this entire region a certain comparative relationship which is hidden to us — so that in this way the inhabitants of this Earth or region bear, through the medium of the whole region, a certain mutual relationship to those other inhabitants. (By comparison, the particular parts of the fingers of a hand bear, through the medium of the hand, a comparative relationship to a food; and the particular parts of the foot bear, through the medium of the foot, a comparative relationship to a hand — so that all members are comparatively related to the whole animal.) Hence, since the entire region is unknown to us, those inhabitants remain altogether unknown.

Quare patet per hominem non esse scibile, an regio terræ sit in gradu perfectiori et ignobiliori respectu regionum stellarum aliarum, solis, lunæ et reliquarum, quoad ista. Neque etiam quoad locum; puta quod hic locus mundi sit habitatio hominum et animalium atque vegetabilium, quæ in gradu sunt ignobiliora in regione solis et aliarum stellarum habitantium. Nam etsi Deus sit centrum et circumferentia omnium regionum stellarum et ab ipso diversæ nobilitatis naturæ procedant in qualibet regione habitantes, ne tot loca cælorum et stellarum sint vacua et solum ista terra fortassis de minoribus inhabitata, tamen intellectuali natura, quæ hic in hac terra habitat et in sua regione, non videtur nobilior atque perfectior dari posse secundum hanc naturam, etiamsi alterius generis inhabitatores sint in aliis stellis. Non enim appetit homo aliam naturam, sed solum in sua perfectus esse. Improportionabiles igitur sunt illi aliarum stellarum habitatores, qualescumque illi fuerint, ad istius mundi incolas, etiamsi tota regio illa ad totam regionem istam ad finem universi quandam occultam nobis proportionem gerat, ut sic inhabitatores istius terræ seu regionis ad illos inhabitatores per medium universalis regionis hinc inde quandam ad se invicem habitudinem gestent, sicut particulares articuli digitorum manus per medium manus proportionem habent ad pedem et particulares articuli pedis per medium pedis ad manum, ut omnia ad animal integrum proportionata sint. Unde, cum tota nobis regio illa ignota sit, remanent inhabitatores illi ignoti penitus, sicut in hac terra accidit, quod animalia unius speciei quasi unam regionem specificam facientia se uniunt et mutuo propter communem regionem specificam participant ea, que eorum regionis sunt, de aliis nihil aut se impedientes aut veraciter apprehendente.

—Nicolaus Cardinal Kues, De docta ignorantia, lib ii, cap xii (1439), in: Philosophisch-theologische Werke in lateinischer und deutscher Sprache, vol 1, pp. 100–103.

[Scott Horton]

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Las pardelas son un grupo de aves pelágicas de la familia Procellariidae de tamaño medio y provistas de largas alas. Existen más de 20 especies de pardelas, las más grandes del género Calonectris y muchas especies pequeñas del género Puffinus, y del reciente género Ardenna. Las aves del género Procellaria se consideraban dentro de este grupo, pero basándose en estudios recientes se descubrió que no están tan relacionados como las aves del género Pseudobulweria y Lugensa que tomaron su lugar.1 El género Puffinus puede ser dividido en un grupo de especies pequeñas cercanas al género Calonectris y otras más grandes distantes a ambos.2

Estas aves son más comunes en aguas templadas y heladas. Son pelágicas fuera de la temporada de cría. Vuelan con largas alas planeando en el aire con el mínimo esfuerzo y recorriendo grandes distancias. Algunas especies pequeñas, como la pardela pichoneta son cruciformes en vuelo, con su ala larga sostenida directamente hacia fuera de sus cuerpos.

Pueden llegar a vivir muchos años. Una pardela sombría que anida en las islas Copeland, Irlanda del Norte, era entre 2003 y 2004 el ave más antigua en libertad del mundo: se lleva control de ella después que la anillaron, ya adulta (por lo menos tenía 5 años) en julio de 1953, y fue atrapada una segunda vez en julio de 2003, teniendo por lo menos 55 años. Las pardelas sombrías migran 10 000 km hasta Sudamérica en invierno, llegando al del sur de Brasil y a Argentina; entonces la pardela sombría de las islas Copeland ha recorrido un mínimo de 1.000.000 de kilómetros en su vida, sin contar lo que vuela en el día.

Las pardelas van a las islas y a los acantilados solamente a anidar. Tienen costumbres nocturnas para anidar, prefiriendo las noches sin luna para minimizar la depredación. Anidan en madrigueras donde ponen un solo huevo blanco.

Se alimentan de pescado, calamares y alimentos similares que el océano le otorga, aunque algunos pueden seguir a los botes pesqueros para comerse las partes de la pesca que se va por la borda. La fárdela negra muchas veces sigue a las ballenas para alimentarse de los peces que se asoman a la superficie luego de su paso.

Datos científicos demuestran, su situación crítica de conservación principalmente debido a la introducción de predadores en sus lugares de cría (por ej. ratas y gatos), la contaminación lumínica, la sobrexplotación pesquera y la interacción con pesquerías industriales.3 La contaminación marina y concretamente la ingesta de plástico es otra amenaza importante pues puede provocar el bloqueo del tubo digestivo, úlceras e incluso transferir contaminantes a los tejidos de las aves. En algunas especies se han registrado 276 piezas de plástico dentro de un polluelo de 90 días, siendo el 15% de su masa corporal. Esto traducido en términos humanos, sería al equivalente en una persona a tener alrededor de 6 u 8 kilos de plástico dentro del estómago.

Las pardelas son parte de la familia Procellariidae, que también incluye a los petreles fulmares, priones y fardelas.

La pardela ha sido declarada "Ave del Año 2013" por SEO BirdLife.

Curiosidades[editar]

Claudio Eliano incluye un pequeño relato sobre la pardela en el Libro I de su obra sobre la naturaleza de los animales (en griego: Περὶ ζῴων ἰδιότητος Perí zóon idiótitos; aunque citado a veces por su título en latín, De Natura Animalium o Historia animalium). Según cuenta, esta ave vive en la isla Diomedea o Diomedia, no ataca a los bárbaros pero se mantiene alejada de ellos, en cambio, a los helenos (o griegos) los recibe amistosamente. Eliano expresa que la especial relación entre estas aves y los helenos se debe al héroe tracio Diomedes (en griego: Διομήδης); éste las tenía por compañeras de viaje, pues según cuenta el autor, se trataban de combatientes caídos durante la guerra de Troya que aun lo acompañan pero metamorfoseados en pardelas.

En el Compendio de metamorfosis de Antonino Liberal se dice que el origen de estas aves deviene de una rebelión de los daunios. Éstos fueron ayudados por Diomedes en una guerra contra los mesapios. Tras la victoria, Daunio, rey de los daunios, en agradecimiento, casó a su hija con el héroe tracio y le concedió tierras que más tarde repartió entre sus compañeros dorios. Muerto Diomedes y muerto Daunio; los daunios, envidiosos de las tierras de los dorios, instigaron una revuelta en la que acabaron masacrándolos. Zeus en compensación por esa atrocidad, transformó a los griegos asesinados en pardelas. Esta historia sirve como explicación del motivo que también expresa Eliano: que estas aves reciben a los griegos y rehúyen a los bárbaros.

En su cuaderno de bitácora, a fecha del 4 de octubre de 1492, Cristóbal Colón se refiere al avistamiento de más de cuarenta "pardeles".

1 note

·

View note

Photo

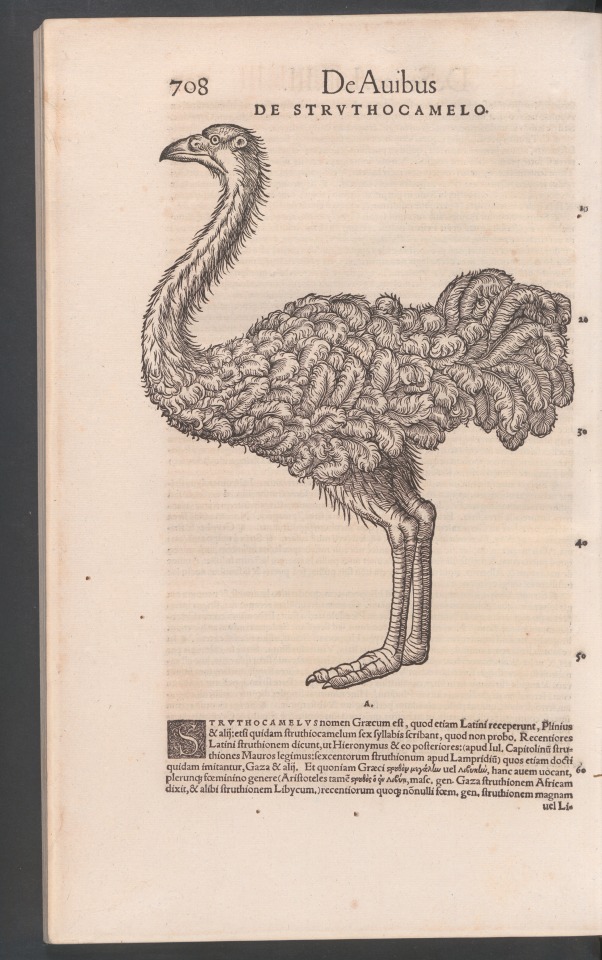

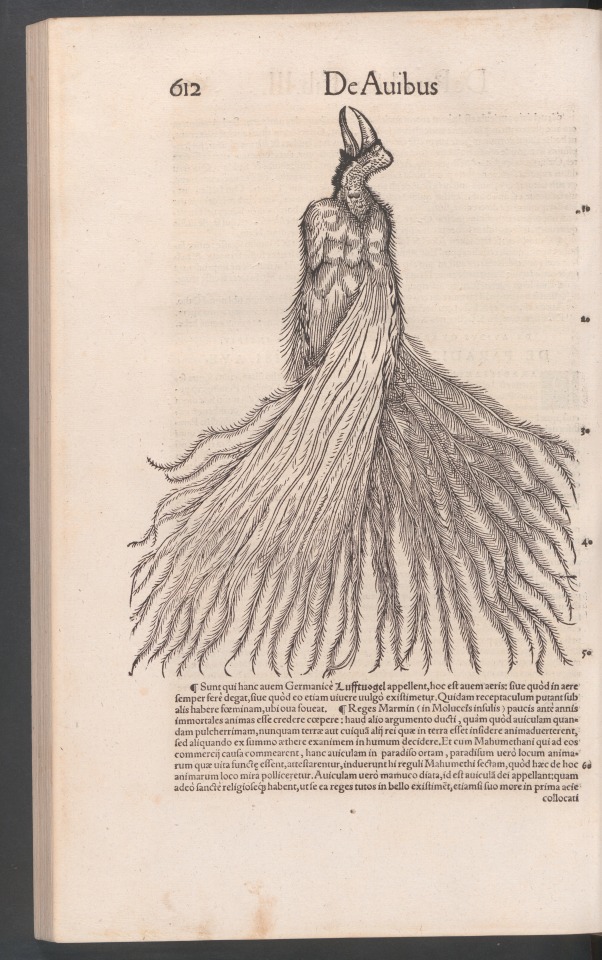

Gessner’s “Struthocamelo” and “Paradisea” in his Historiae animalium liber III., qui est de avium natura (Zurich, 1555), pp. 708 & 612.

Fun historical fact about the “Struthocamelo”: ostriches, also known as Struthio camelus (literally: sparrow camel), have according to Pliny the Elder “the marvellous property of being able to digest every substance without distinction, but their stupidity is no less remarkable; for although the rest of their body is so large, they imagine, when they have thrust their head and neck into a bush, that the whole of the body is concealed.” (Plin. Nat. 10.1)

And of course the bird-of-paradise, that curious creature “without feet.”

The bird-of-paradise can be found in Laureis van Haecht Goidtsenhoven’s Mikrokosmos, Parvus Mundus (Antwerp: 1579) where it is depicted in the print of “Fortunae Natura”: both Fortuna and the bird are are footless, always unstable and going where the wind blows.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Medieval Marginalia

Whether we like to admit it or not, we have all doodled in the margin or on a photo in a book at one time in our lives. Doodling has been a component of writing since people starting writing their thoughts on cave walls. On this Tumblr page, I am going to share some of the more weird and wacky medieval marginalia that has been found and cataloged.

Let's start off with a cuddly animal everyone loves! Bunnies!!

public domain

These are no ordinary bunnies!!! These are killer bunnies.

public domain France 13th cent. Royal 10 BL

public domain La Somme le Roy, France ca. 1290-1300. British Library, Add. 28162, fol. 12v

public domain

public domain

public domain Breviary of Renaud de Bar, Verdun, Bibliothèque municipale, MS 107, fol. 96 v .

public domain Breviary of Verdun. Image: Verdun, Bibliothéque municipale, MS 107, fol. 141v.

It looks to me like they are exacting their revenge!

Did one smart rabbit get a whiff of what what was cooking in the house?

Silly human, rabbits can't read!

Let's take a look at a few more categories of marginalia!

The cost of a book in the 12th -14th century was astronomical. Only the literate elite could afford them. Just imagine you acquire a one-of-a-kind handmade book and you open up to see in the margin, a man who farts, or find a tree of male appendages at the bottom of a page.

Which brings us to our next category:

Rear ends and appendages

This upside-down world found in the sacred texts is very perplexing. I would love to be a medieval fly on the wall when the book purchaser gets his book delivered, sits down in his very uncomfortable 13th century chair, and beholds this glorious illuminated manuscript to find butt trumpets. Many, butt trumpets.

public domain from the Rutland Psalter, c. 1260. (British Library Royal MS 62925, f. 87v.)

public domain

public domain The Vows of the Peacock c. 1350

public domain

public domain

public domain

public domain

public domain

public domain Maccesfield Psalter

Appendage elements were also prevalent in early marginalia.

public domain Arderne’s treatise. GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY MS HUNTER 251 (U.4.9)

public domain from the Roman de la Rose, c. 1325-1353. (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS. Fr. 25526, f. 106v.)

public domain Decretum Gratiani with the commentary of Bartolomeo da Brescia, Italy 1340-1345. Lyon, BM, Ms 5128, fol. 100r

Not all marginalia is grotesque, vulgar, and crude. There are many whimsical and charming examples, too!

Here are just a few random styles that do not fit into a specific category.

public domain from the Summer volume of the Breviary of Renaud and Marguerite de Bar, Metz ca. 1302-1305. (Verdun, Bibliothèque municipale, MS 107, f. 99v.)

public domain Cosmographie universelle, selon les navigateurs tant anciens que modernes / par Guillaume Le Testu, pillotte en la mer du Ponent, de la ville francoyse de Grâce (1555). Detail of ‘Mer de l’Inde orientale’ (p.64)

public domain Glasgow University Library MS Hunter 251 (u.4.9)

public domain Taymouth Hours, 14th c. The British Library ms 13, f. 142r

public domain The Gorleston Psalter, c. 1310 The British Library, ms 49622, f. 104v

public domain diurnal, France c. 1400 Avignon, Bibliothèque municipale, ms. 103, fol. 45r

public domain Paulus Kal: Fechtbuch, gewidmet dem Pfalzgrafen Ludwig - BSB Cgm 1507, [S.l.] Bayern, second half 15th century (not after 1479)

public domain book of hours, c. 1320 The British Library, Harley ms 6563, f. 78v

public domain Holy Land by Martin de Brion of Paris, France, 1540, Royal MS 20 A. iv, f. 3v

public domain Douai, Bibliothèque municipale, 0711, detail of f. 32. De natura animalium (13th century)

1 note

·

View note

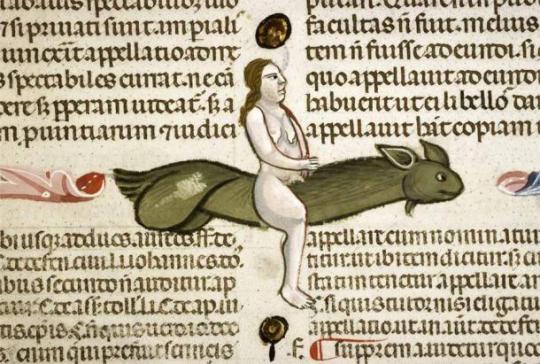

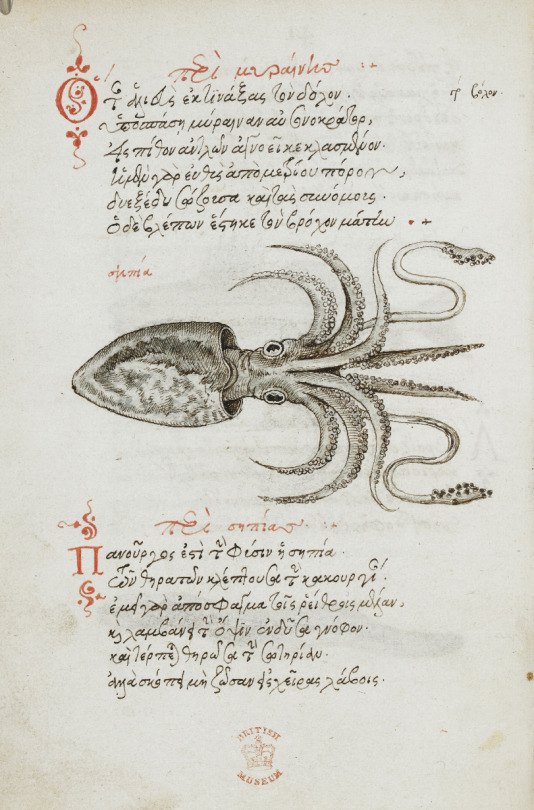

Photo

1.Miniature of a centaur, 2. Miniature of a cuttle-fish, 3. Miniature of a porcupine, 4. Miniature of a unicorn.

From “De natura animalium”, c. 1550-1569.

•

Follow for more: Instagram | Pinterest

#De natura animalium#1500s art#1500s#16th century#zoology#manuscript#illuminated manuscript#medieval illustration#renaissance art#cuttle-fish#unicorn#centaur#porcupine#animals

281 notes

·

View notes

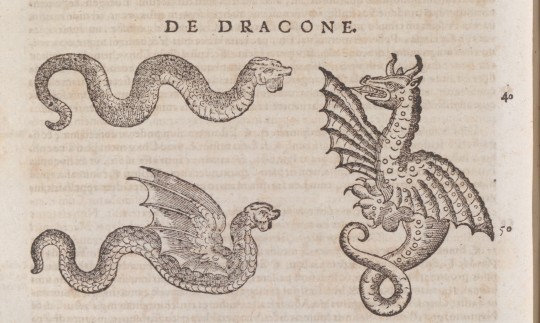

Photo

Dragons from Conrad Gessner’s Historiae animalium liber V., qui est de serpentium natura (Zürich 1587).

Source: Zentralbibliothek Zürich (Call No. NNN 43,2 , online: https://doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-5255)

422 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just had to find this book :)

Btw more ebooks here: https://romegreeceart.tumblr.com/kirjat

7 notes

·

View notes

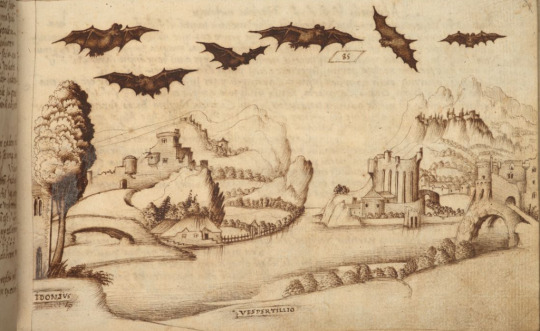

Photo

Bats ('vespertillo')

Historia Animalium, 1595

Liber Animalium, consisting of 245 pen-and-ink drawings of different species of animals and mythical creatures, each accompanied by a description, beginning 'Cui rei data est fabula ut hoc ita accidat aquile quonia cu[m] olim homo esset sospiti iniuria'. The descriptions include details of the anatomy, development and behaviour of the creatures, and are based on Aristotle, Historia animalium, Pliny the Elder, Naturalis historia, Aeliani, De historia animalium and Albertus Magnus, De natura animalibus.

Add MS 82955

#manuscript illumination#art#16th century art#illumination#bats#vespertillo#1595#historia animalium#vespertilio

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Leontophone [medieval European folklore; Roman mythology]

The leontophone – from the Greek “leontophonos” or “lion-killer” – is a mythical beast that is described in medieval bestiaries. Its most defining trait is that the creature is a primary component in a fail-proof lion trap. Supposedly, if you kill a leontophone and burn its body, you can sprinkle its ashes on a piece of meat and place the meat near a crossroad. Lions will be attracted to the bait and they will die if they eat even a tiny piece of it.

As such, lions will try to kill any leontophone they come across, but always with their claws instead of their teeth, lest they should swallow a tiny piece of the deadly creature.

The appearance of these creatures is unknown, except for the fact that they are tiny. Despite this, they are commonly depicted as large (often larger than lions) furry creatures, resembling quadrupedal mammals, usually with a tail. This is the image that caught on with artists.

Actually, there are older mentions of the ‘leontophonos’: the Roman author Aelianus wrote that lions will die if they eat it, but he did not specify what a ‘leontophonos’ is. It might not even have been an animal at all.

It probably won’t surprise you that Plinius Maior wrote an entry on these creatures as well. He also mentioned a statement that was apparently overlooked by later authors: that the urine of the leontophone is highly venomous to lions as well. In fact, a leontophone who encounters a lion will attempt to urinate on it.

Sources:

The Aberdeen bestiarium (12th century), which you can read here.

The “De Natura Animalium” by Claudius Aelianius, book 4, part 18, which you can read a translation of here.

“Naturalis Historia” by Plinius Maior, book 8, chapter 57, which you can read here.

(image source 1: FellFallow on Deviantart)

(image source 2: Behane on Deviantart)

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Monsters in sewers; Roman legends of octopus in the urban environment; myth-making about liminal space, urban landscape, edges.]

Present-day New York and the ancient Roman town of Puteoli have at least one thing in common: the sewer systems of both have been said to harbor rather unusual creatures. [...] The legend of the alligators in the sewers turned out to have older antecedents [...].

[T]he common core of the stories is the hostile intrusion of a wild beast, an octopus, into the urban environment [...].

[The legends]

The ancient legend is [...] preserved in two variants, both incroporated into the fabric of literary works on natural history. The first is included in the work of De natura animalium [...] by [...] Aelian (AD 165/170 -- 230/235), [...] of Praeneste, Italy [...]. Written in Greek [...]. The second comes from a Latin sources [...] in the voluminous Naturalis historia [...] authored by Pliny the Elder (AD 23/24 -- 79). [...] The ancient legend features a multifaceted and even contradictory animal [...]. The most basic trait is its liminality: the octopus often tends to straddle or transgress two cultural categories at once, fully belonging to neither [...]. In [...] folk belief, the octopus was regarded as simultaneously being and not being a fish [...]. The entire body of the octopus was a contradiction [...], with the numerous, fluidly flexible tentacles and a front side that was indistinguishable from the back. [...] Aelian mentions craftiness [...], the octopus was a symbol of intelligence [...]. Its ability to change color in accordance with its surroundings was interpreted to be [...] cunning (Theognis; Plutarch ...). [...]

In Aelian’s version the octopus emerged through the city sewers, whereas in Pliny’s it descends from the sky by climbing up and down a tree. [...] The octopus transgresses other categorical boundaries as well. Aelian states that the octopus “despised and disdained the food from the sea and its pasture.” Its unquenchable desire for pickled fish or fish sauce, the much-loved garum of the Romans, means that it abandons its own natural, unprocessed food for a quintessentially human gastronomic product.

[Seafood, cultural importance of Iberia, Edges of Empire, limnality of The Ocean]

Garum [...] provided the Roman diet with salt [...]. It was an important object of trade and Iberian garum was deemed to be some of the very best [...]. The Iberian merchants functioning as the human protagonists in Aelian’s variant of the legend [...] represent the archetypal garum merchants [...]. The octopus’ monstronsity [...] in Pliny’s [account] gains an added dimension because of the Roman cultural conceptions of the prodigous bounty of the Iberian waters. Many types of fish and marine animals, such as conger-eels, lampreys, trumpet-fish, purple-fish, cuttlefish, and octopuses were thought to attain giant proportions there. [...] [T]he waters around Italy had been depleted through excessive fishing at this time [...].

[T]he motif might also be related to the notion that Iberia was situated at an important geographical and conceptual boundary, which may have imbued it with liminal qualities. The Pillars of Hercules, i.e., Gibraltar, had long been considered the last stop before the vast innavigable ocean [...]. In the first century AD this idea of a boundary took on renewed relevance with the Roman conquest of large parts of the known world. Roman ambition needed a new purpose and the legendary, dangerous ocean beyond, which few had as yet penetrated [...] could provide the basis for dreams [...]. Thus, the monstrous octopus might be set to fit into the general paradigm [...] of the wonders at the edge of the known Earth. [...] In terms of social status, the benefits of producing and propagating such accounts were actually so great that Roman officials of the early Empire actively competed with each other in producing them [...]. Pliny himself captures this pervasive ambience of the marvelpous nicely when he describes the story he is about to relates as “close to the wondrous” [...].

[Sewers]

Aelian’s account exploits the notion of the intruder entering the city through the sewers [...]. The most celebrated sewer was the Cloaca Maxima [...] [T]he sewers were counted among the greatest of all Roman accomplishments [...] Some went as far as to compare the city of Rome with Babylon and Thebes -- alluded to as “the hanging cities.” Rome similarly “hung above” the torrents of its magnificent sewer system (Pliny the Elder Naturalis historia ...; Dionysius of Halicarnassus Antiquitates Romanae ...’ cf. Strabo Geographia ...). The sewers furnished the foundations on which Roman greatest rested [...]. On the other hand, turninig a sewer into a triumphal arch, as a great Roman proverb stated (Cicero Pro Placio 40.95), did not succeed in ridding the sewers of their more unpleasant connotations. [...] In terms of metaphor, the sewers were frequently associated with the less noble parts of the body: the guts (Cicero ibid; Varro ...). [...]

The fear of sewage clogging up the drain during floods and causing an intrusion of alien filth into the home is believed to have been a [...] factor in keeping private households disconnected from public sewers. [...] This anxiety about the sudden reemergence of dirt recurs in the legend narrated by Aelian [...]. The octopus strengthens its liminal position by transgressing not only conceptual boundaries between cultural categories, but also the physical boundaries between nature (the world of the sea) and culture (the sphere of the human city). By traveling between these spheres through the manmade sewers, the octopus metaphorically conquers the human domain by stealing through the underground structures of the city to the surface.

--

Text from: Camilla Asplund Ingemark. “The Octopus in the Sewers: An Ancient Legend Analogue.” Journal of Folklore Research Vol. 45 No. 2. 2008

Bolded text/headings added by me.

14 notes

·

View notes