#Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad

Text

Mud Tunnel

Here are two shots taken at Mud Tunnel on the Chesapeake & Ohio. This spot is just west of Covington, Virginia. We first see a westbound freight and then the eastbound Amtrak James Whitcomb Riley powered by a General Electric P30CH.

Update: someone on FB tells me this locomotive was destroyed later in 1977 when it struck a logging truck near Florence, SC.

Two images by Richard Koenig; taken March 23rd 1977.

#railroad history#railway history#amtrak#jameswhitcombriley#covingtonvirginia#covingtonva#covington#c&o#chesapeake & ohio

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since I made many posts on my TTTE OCs from the New York Central and Pennsylvania Railroad, I was recently thinking about expanding my roster of OCs… and these extra OCs would be from the…

Chesapeake & Ohio…

Baltimore & Ohio…

Milwaukee Road…

Burlington Route…

and…

Chicago & NorthWestern

Now since this is a recent thought, I haven’t thought about the names of the OCs from these five railroads, let alone what type of locomotives they would be. But don’t worry, when I think of it, I’ll make posts showing and going over them, so stay tuned for that, folks.

#chesapeake & ohio#baltimore & ohio#milwaukee road#burlington route#chicago & north western#thomas the tank engine#thomas and friends#ttte#ttte oc#train#trains#railroad#railroads#railway#railways#the genie team

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Several days before Christmas, Santa pays a visit to the South Branch.

Hanging Rocks, WV

December 19, 1992

#pesr#potomac eagle scenic railroad#b&o#baltimore & ohio#c&o#chesapeake & ohio#1992#trains#passenger train#history#hanging rocks#west virginia

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1941 'Be at ease gentlemen, it's Colonel Washington!' Chesapeake and Ohio Lines

Source: Time Magazine

Published at: https://propadv.com/railroad-poster-and-ad-collection/chesapeake-and-ohio-railway-poster-and-ad-collection/

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Masquerading as a C&O Kanawha, Nickel Plate Road 765 powers an excursion through Tennessee with a train of CSX Office Cars in tow.

Models and Route by: K&L Trainz, JointedRail, TrainzProRoutes, Auran, and Download Station

#Chesapeake & Ohio#Chesapeake & Ohio Railway#Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad#Nickel Plate Road#NKP#New York Chicago & St. Louis Railroad#Nickel Plate Road 765#NKP 765#Kanawha#765#2765#steam locomotive#trains#Trainz Simulator

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The C&O Shops at Peach Creek, WV (1974)

C&O Railroad Shops at #PeachCreek #WV (1974) #Appalachia #history #csx #railroad #wvhistory

From the Chesapeake and Ohio Historical Newsletter (June 1974) comes this history titled “The Shops at Peach Creek” composed by C.A. Coulter. This is Part 1 of Mr. Coulter’s account.

The railroad was first built to Logan in 1904, the first train arriving on September 9 of that year. The line was started at Barboursville, West Virginia, on the main line, and ran up the Guyan River for 65 miles to…

View On WordPress

#Appalachia#Barboursville#C.A. Coulter#Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad#Chesapeake and Ohio Historical Newsletter#coal#Empty Yard#Gay Coal and Coke Company#Guyandotte River#history#Huntington#Logan#Logan County#Mount Gay#Peach Creek#railroad#Red Onion#Slabtown#West Logan#West Virginia#World War I

0 notes

Text

the dog fosterer florist asked me about the kitten’s name. I said ‘probs gonna stick with Chessie,’ then she made some kind of reference to a middle name...?

I was like, “her middle name is Ohio.”

“oh yeah that makes sense.”

#there was. a lot of noise. idk if she asked like 'is her middle name ''System''?' or if it was perhaps a song reference or such#but. yeah no it's a railroad thing#Chessie System is the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway is CSX nowadays#meowbagbloggin#my dad thought it was funny. he knows I've always liked their logo. :B

1 note

·

View note

Text

Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad, 1935

127 notes

·

View notes

Video

Chesapeake and Ohio 1309 at the Western Maryland Scenic Railroad Depot in Cumberland, MD. 2/23 por Bryan Burton

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recent Acquisition - Photograph Collection

Original June 1953 caption: "Members of National Railway Historical Society photograph 'Old 377' the C&O's famous high-wheeled, turn of the century locomotive, which has been polished up and used to give antique flavor to civic events at Charlottesville, engine terminal of the Chesapeake & Ohio railroad."

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Died With a Hammer in His Hand: Unpacking the Myth of John Henry

“John Henry said to his captain:

‘You are nothing but a common man,

Before that steam drill shall beat me down,

I’ll die with my hammer in my hand.’”

— “John Henry, the Steel Driving Man,” recounted by W. T. Blankenship

John Henry is one of America’s most well-known mythic heroes, immortalized in song, statue, postage stamp, and multiple movies (including a 2000 Disney animated short film which I vividly remember watching in elementary school). But if you’re unfamiliar with the legend, here’s a brief summary.

John Henry was a freed slave who found himself working for a railroad company in the years following the Civil War as a steel driver. His job was to drive a steel spike into rock so that dynamite could be placed in the resulting hole, thus opening up a tunnel through the Appalachians.

John Henry was the best on his crew, and he took pride in his work—so when a white salesman brought in a steam-powered drill, claiming that it could drill better than any man, he decided to challenge that claim. Henry entered into a contest with the machine to see who could carve out the deepest hole in the mountain in a single day.

His victory cost him his life.

Henry’s wife—sometimes named Polly Ann, sometimes named Lucy, sometimes not named at all—went to visit him on his deathbed that evening. In many versions of the ballad, Henry’s last words are a request for a glass of water. In other versions, he asks his wife to be true to him when he’s dead, or to do her best to raise their son. Many accounts say that he’s buried by a railroad, where “Every locomotive come roarin’ by, / Says there lays that steel drivin’ man” (lyrics from Onah L. Spencer).

Bronze statue of John Henry near Talcott, West Virginia, sculpted by Charles Cooper.

The general consensus among historians now seems to be that the ballad of John Henry is one such legend that has its roots in historical fact, although the particulars are long obscured by the centuries that have since passed. Henry was born into slavery in the 1840s or 50s, either in North Carolina or Virginia (some accounts of the ballad lend credence to the latter claim). As for how John Henry found himself working for the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway company, University of Georgia history professor Scott Reynolds Nelson posits in his book Steel Drivin’ Man that the man was sentenced to ten years in a Virginia prison for theft at only nineteen years of age, and that he was among many prisoners leased out by the state for labor.

Did you know that the 13th Amendment makes an exception for slavery which is used “as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted”? (This practice continues to this day, and has become an industry worth tens of billions of dollars. Louisiana State Penitentiary, also known as Angola or simply “The Farm,” is a good place to begin if you’re wanting to look into chain gangs further.) John Henry the legend was a free worker who took on the backbreaking, often dangerous work of railroad labor under his own power and could demand any wage for his work, but John Henry the man may have lived and died in neoslavery.

Speaking of Henry’s death, most retellings of the myth say that he died of sheer exhaustion. Some add in the detail that it was his heart that gave out because he worked himself too hard. However, alternate theories have been proposed for how the man died. Some historians say it was a stroke that killed him, while others posit silicosis.

It’s this latter hypothesis which I find most intriguing. For those who aren’t familiar with it, the American Lung Association describes silicosis as “a lung disease caused by breathing in tiny bits of silica, a common mineral found in sand, quartz and many other types of rock.” It’s been an occupational hazard for construction workers since, well, the time of John Henry. What I find interesting are the implications for the narrative if the real Henry died of silicosis. In the folk ballad, Henry causes his own death by working himself too hard. On the other hand, the ones at fault if the man died of silicosis would be his employers—the ones responsible for the dangerous conditions he worked in.

So why would John Henry’s cause of death change during the transition from fact to legend?

The answer, as with many other fictionalized accounts of historical events, is that it simply makes for a more effective story. But not just that—a more effective message. So what might the ballad be trying to tell those who listen to it?

First, let’s think about who this song was sung by and for. The ballad of John Henry is a work song, its rhythm meant to help railroad workers stay and strike in sync, in the same way a drumbeat helps soldiers march in step. It’s been sung by railroad workers, miners, construction workers, chain gangs, and country musicians. At its core, then, the ballad is a song of and for the American working class—specifically those people doing the same sort of backbreaking physical labor as John Henry himself. Many of these laborers would have been Black, and likely former slaves—especially when it came to Southern chain gangs. (See my above note about how American slavery was only mostly abolished, and then think about why the U.S. has one of the highest incarceration rates in the world. . . but I digress.)

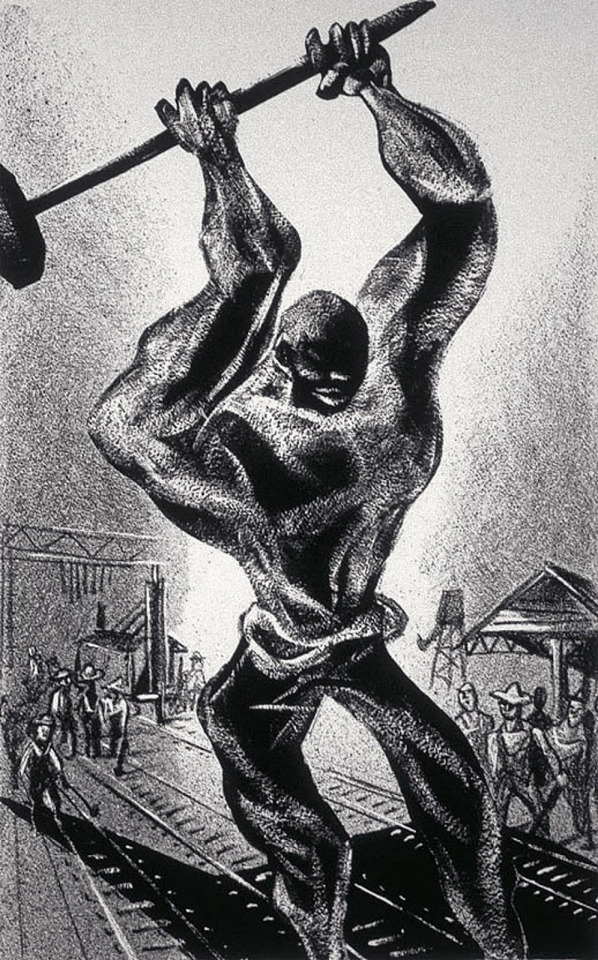

An oil painting of John Henry by Frederick Brown.

We’ve established that John Henry is a hero for working-class Americans during the time of the Second Industrial Revolution. But what sort of hero is he? Is he like Achilles, a paragon of his country’s values and an example for the audience to aspire to? Or is he an Icarus, a cautionary tale sung so the audience won’t repeat his mistakes?

The answer depends on who’s telling the story.

Onah L. Spencer is the source for one version which emerged from a Black community in Cincinnati, Ohio. When he recounted the lyrics to Guy B. Johnson for the latter’s 1929 book John Henry: Tracking Down a Negro Legend, he also stated that the song was used to motivate workers: “. . . if there was a slacker in a gang of workers it would stimulate him with its heroic masculine appeal.”

In cases such as Spencer’s crew, then, John Henry’s death is presented as glorious, and Henry is seen as admirable for working so hard that it kills him. Here, he’s a good example. Taken to the extreme, the Achillean Henry encourages fellow workers to follow in his footsteps—to keep pushing themselves harder and harder until they finally keel over.

This message doesn’t benefit the workers passing it along; it benefits the employers profiting from their labor. This, I think, is where the story blurs the line between myth and propaganda. And while the ballad of John Henry certainly isn’t singlehandedly responsible for the American tendency to overwork ourselves, it does reflect our attitudes about work in a way that’s worth unpacking. To me, this reeks of the Puritan work ethic. The belief was that you had to be working as often as you could; if you didn’t, the devil would be able to influence you. The Puritans were one of America’s foundational cultural influences—of course those values would have influenced the ballad of John Henry.

Henry is a hero because he worked himself to death. If we see him as a good example, what does this say about the effects that capitalism has had on American attitudes? About the internalized belief that our worth as humans only comes from what we can contribute to the economy? Why do we see death from exhaustion as a fitting end for a former slave?

Then again, maybe we’re not supposed to.

A lithograph of John Henry, from the series American Folk Heroes, by William Gropper.

Remember how I noted earlier that many of the laborers who first sang Henry’s ballad would themselves have been former slaves? It’s important because there’s a long history of American slaves using work songs as a tool of resistance against their oppressors, and these Black laborers—these “freed” slaves—would have carried that tradition with them into the Second Industrial Revolution.

The ballad of John Henry, then, might have been sung with the intent of helping other workers survive the brutal conditions on the railroads. Here, Henry becomes an Icarus—a warning of what happens if you push yourself too hard. One version of the ballad recorded by Edward Douglas of the Ohio State Penitentiary contains lyrics which suggest that not every Henry was meant to be emulated.

“John Henry started on the right-hand side,

And the steam drill started on the left.

He said, ‘Before I’d let that steam drill beat me down,

I’d hammer my fool self to death,

Oh, I’d hammer my fool self to death.’”

Don’t do what John Henry did, this version warns the audience. Be wiser than he was. Don’t push yourself quite so hard. Think of the people you’d be leaving behind if you’re not careful.

Perhaps even the creation of this mythos was an act of defiance in and of itself. At this point, I think it bears mentioning that I myself am not Black and can only hypothesize based on what I’ve heard from people who are, but I see something radical in the act of raising up one of your own as your hero rather than venerating the people you’ve been told are superior to you.

Remember, John Henry’s contest was versus a white man’s machine. It costs him everything, but he triumphs over the expectations of that steam drill salesman and proves his worth as a laborer and a person. John Cephas, a blues musician from Virginia who was interviewed by NPR for a report on John Henry back in 2002, had this to say of the myth:

“It was a story that was close to being true. It’s like the underdog overcoming this powerful force. I mean even into today when you hear it (it) makes you take pride. I know especially for black people, and for people from other ethnic groups, that a lot of people are for the underdog.”

Americans love underdog stories. Our own national origin myth is one! John Henry’s assertation of power and skill, the ballad’s declaration that Black people have the right to be proud of themselves too. . . no wonder this myth has resonated with so many people. No wonder it’s survived for a century and a half.

In this light, then, John Henry once again becomes a hero for us, the audience, to emulate. In the fight against oppression, endurance like Henry’s becomes key. Justice is almost never won quickly. The odds stacked against us may seem impossible, but it’s worth trying anyways, even if we have to fight to our dying breaths.

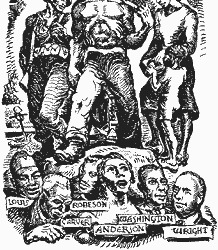

Artwork of John Henry as a defense worker by James Daugherty.

John Henry has meant and been many things to a lot of people in the past two centuries. A representative of capitalist exploitation, a cautionary tale for workers, an inspiration to oppressed people in America, even a communist icon—but I’d like to take a moment to talk about what his story means to me. It’s not something I’ve seen discussed in my research, and I think it’s worth exploring.

John Henry reflects fears of workers during the Second Industrial Revolution who saw how technology was evolving—how machines were being created that could do their jobs not just faster, but cheaper, because you don’t have to pay a machine like you would a person. They feared that they would be replaced, and that they would be left destitute while their former bosses grew richer and richer. And despite the centuries between us, this is a fear that I can understand.

Often, I feel it myself.

As an artist existing in online spaces during this new influx of AI-generated “art” and writing, I have witnessed many fears that we will be replaced by AI. Yes, there is a certain human quality to art that a generative learning model cannot replicate, but who’s to say that the much-vaunted free market will care? We can hope that art as a profession will survive, but we just don’t know.

In John Henry’s struggle, I see my own. In the steam drill salesman, I see tech bros on the platform formerly known as Twitter showing off their latest batch of beautiful, hollow, AI-generated “art.” I see John Henry’s passion, his pride, his triumph.

And I see hope.

By his life and death, the mythic John Henry reassures me that human beings aren’t so easy to replace after all. He tells me that machines can be defeated. That one day, my vindication as an artist and writer will come, and the world will see our worth.

The ballad of John Henry has endured like a mountain for a hundred and fifty years, and I hope it will survive for hundreds more—that John Henry’s hammer will continue to ring true throughout the ages. But in the midst of American mythos, it’s important not to lose sight of the historical facts behind it. Legends are interesting and inspirational and wonderful, but the real stories have something to tell us, too.

Don’t forget to listen.

Works Cited

American Lung Association - Silicosis

Ballad of America - This Old Hammer: About the Song

Constitution of the United States - Thirteenth Amendment

Encyclopedia Britannica - John Henry

Flypaper by Soundfly - The Lasting Legacy of the Slave Trade on American Music

Folk Renaissance - John Henry: Hero of American Folklore

How Stuff Works - Was There a Real John Henry?

ibiblio.org - John Henry: The Project

National Park Service - The Superpower of Singing: Music and the Struggle Against Slavery

NPR - Present at the Creation: John Henry

NPR - Talk of the Nation: The Untold History of Post-Civil War ‘Neoslavery’

PBS - Mercy Street Revealed Blog - Singing in Slavery: Songs of Survival, Songs of Freedom

Prof. Scott Reynolds Nelson - Steel Drivin’ Man: John Henry, the Untold Story of an American Legend

World Population Review - Incarceration Rates by Country 2024

#john henry#american mythology#analysis#essay#black history month#ari speaks#hi I wrote this for my english class and I felt compelled to share it here

11 notes

·

View notes

Video

C&O, Ludington, Michigan, 1982 by Center for Railroad Photography & Art

Via Flickr:

Chesapeake and Ohio Railway SS City of Midland 41 ferry in Ludington, Michigan, on February 27, 1982. Photograph by John F. Bjorklund, © 2015, Center for Railroad Photography and Art. Bjorklund-35-09-10

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here’s an updated version of my profile picture of me made greatly by @grantgfan and @hunty627. Since I have Procreate, I thought I’d expand and add different shirts and caps (and even shoes) to myself in these pictures. But the one above is the first and original profile and can be used from time to time by myself, Grant and Hunter. And this setup has a shirt that’s green on the top half and has the New York Central logo on it, and the bottom half is red and has the Pennsylvania Railroad logo on it. This shirt’s setup is a nod to the fact that NYC and PRR were fierce arch rivals during their day (before public betrayal, ICC villainy and interference, and mergers happened) over the routes between New York City and Chicago. Not to mention NYC was often dubbed the “Green Team” and PRR was dubbed the “Red Team”. As for the cap, it’s light blue’n’blue and has the Union Pacific logo, and that’s a reference to the fact that UP is the only surviving ancient American railroad.

Here’s the first new profile, and this second shirt has its top half green with the New York Central logo on it, and bottom half navy blue and has the Chesapeake and Ohio logo on it. This symbolizes the fact that during the age of steam on the railroads, the New York Central got the coal for its steam locomotives from the Chesapeake and Ohio.

Here’s the second setup in this group of setups. In this one, I have a shirt that’s navy blue on the top half and has the Chesapeake and Ohio logo, and the bottom is a lighter blue and has the Baltimore and Ohio logo. This set is a reference to the fact that C&O and B&O had a rivalry in terms of transporting people and goods across the Application Mountains.

Here’s the third setup in this group of setups. Here, I have an orange’n’red cap with the Milwaukee Road logo on it. The shirt here has a yellow’n’green top half with the Chicago and Northwestern logo on it, and the bottom half is white’n’red and has the Burlington Route logo on it. This setup is a reference to the fact that during the golden days of American railroading (before public betrayal, ICC villainy and interference, and mergers), these three railroads had a super tense rivalry with each other over the railroad routes between Chicago and Twin Cities (Minneapolis and St. Paul), with Milwaukee Road’s Twin Cities Hiawatha, Chicago and Northwestern’s Twin Cities 400 and Burlington Route’s Twin Cities Zephyr all racing against each other from Chicago to Twin Cities, and from Twin Cities to Chicago.

Here’s the fourth and final setup for this group of setups. Here, I have a red’n’white cap with the Burlington Route logo on. And the shirt here has its top half with the two shades of green of Northern Pacific and the Northern Pacific logo on it, and the bottom half of the shirt has orange and brown of Great Northern and has the Great Northern logo on it. This setup is a reference to the formation of Burlington Northern, which was formed when these three railroads merged on March 2nd, 1970.

And that’s all the setups for this batch. More are on the way, I just gotta think about what other colors and railroad logos to add and in which specific setup to serve as a reference to historical facts regarding the specific railroads.

#my oc character#my oc art#union pacific#new york central#pennsylvania railroad#chesapeake & ohio#baltimore & ohio#milwaukee road#chicago & north western#burlington route#northern pacific#great northern#the genie team#genie team

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mount Hood Railroad

To follow up on the previous post, here are some images taken of the Mount Hood Railroad, in Hood River, Oregon. It originally operated between 1906, when it was built, and 1987. At that time it was purchased and transitioned to primarily a tourist operation.

The railroad is one of the few that still utilize switch-backs. The station dates from 1911, built by the Oregon Railroad & Navigation Company, a subsidiary of the Union Pacific. The building is on the National Register of Historic Places. The GP9 seems to have been built for the Chesapeake & Ohio in 1957.

Four images by Richard Koenig; taken March 20th 2023.

28 notes

·

View notes

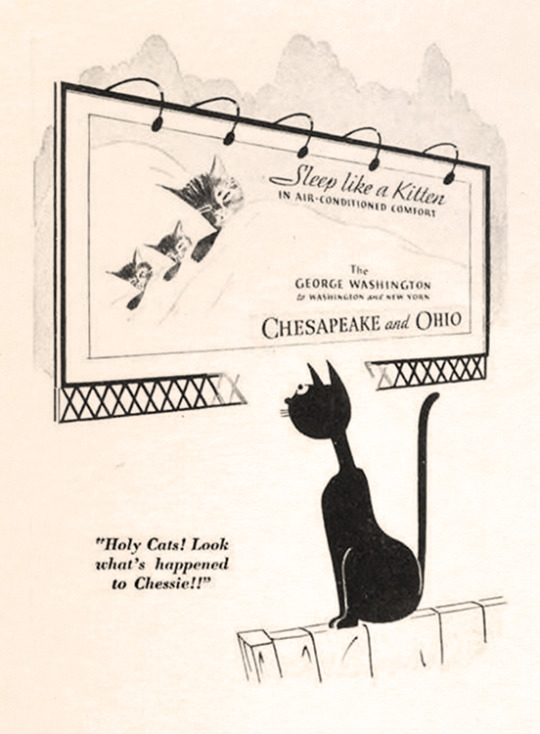

Photo

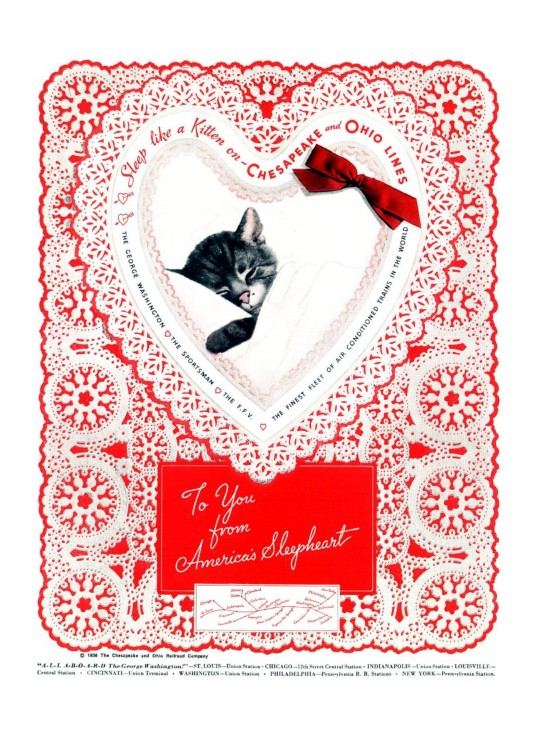

1936 Sleep like a Kitten on - Chesapeake and Ohio Lines. To You from America's Sleepheart

Source: Time Magazine

Published at: https://propadv.com/railroad-poster-and-ad-collection/chesapeake-and-ohio-railway-poster-and-ad-collection/

1 note

·

View note

Text

As we all know, the Chessie streamliner sadly never entered service for numerous reasons. But in our imaginations, we can depict about what it would be like for if the train did end up entering revenue service. Here along the New River Gorge somewhere between Prince and Hinton, West Virginia, a Chesapeake & Ohio M-1 thunders along the Hinton Division while leading the Eastbound Chessie to Washington D.C. on a peaceful Summer afternoon.

Models and Route by: Roloz Trainz, K&L Trainz, Auran, and Download Station.

#C&O#Chesapeake & Ohio#Chesapeake & Ohio Railway#Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad#Chessie#Chessie Train#Streamliner#Streamlined Trains#M-1#Chesapeake & Ohio M-1#C&O M-1#Steam Turbine Locomotive#Trains#Trainz Simulator

1 note

·

View note