#Brom and Bett v. Ashley

Photo

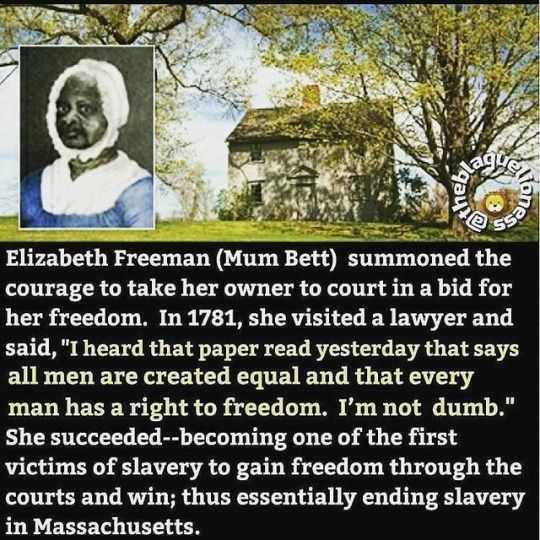

Elizabeth Freeman (c. 1744 – December 28, 1829), also known as Bet, Mum Bett, or MumBet, first Black woman released from slavery under the Massachusetts state constitution (all men are created equal), essentially ending slavery in Massachusetts circa 1781.

Freedman’s suit, Brom and Bett v. Ashley (1781), was cited in the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court appellate review of Quock Walker's freedom suit. When the court upheld Walker's freedom under the state's constitution, the ruling was considered to have implicitly ended slavery in Massachusetts.

“Any time, any time while I was a slave, if one minute's freedom had been offered to me, and I had been told I must die at the end of that minute, I would have taken it—just to stand one minute on God's airth [sic] a free woman— I would.” — Elizabeth Freeman

Freeman is buried in the Sedgwick family plot in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Freeman remains the only non-Sedgwick buried in the Sedgwick plot. They provided a tombstone, inscribed as follows:

ELIZABETH FREEMAN, also known by the name of MUMBET died Dec. 28th 1829. Her supposed age was 85 Years. She was born a slave and remained a slave for nearly thirty years; She could neither read nor write, yet in her own sphere she had no superior or equal. She neither wasted time nor property. She never violated a trust, nor failed to perform a duty. In every situation of domestic trial, she was the most efficient helper and the tenderest friend. Good mother, farewell.

Children: Bett (Betsy) "Lil Bett" Humphrey formerly Freeman, died after 1811 after about age 46 [location unknown]. She is listed under her mother's freed slave name since her father's name is unknown. Her mother took the name "Freeman" after winning her freedom and probably gave the name to her young daughter. Betsy married Jonah Humphrey, who then disappeared from the area around 1811. Betsy may have married Jack Burghardt, great grandfather of civil rights leader W. E. B. Du Bois, but this is speculation.

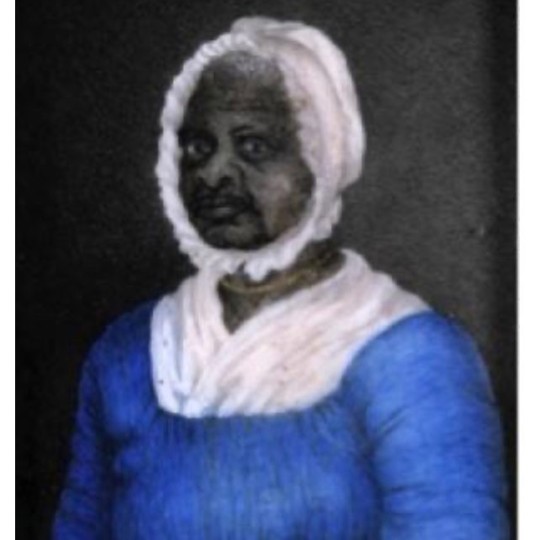

Painting of Elizabeth Freeman, aged 70. Painted by Susan Ridley Sedgwick, aged 23. Watercolor on ivory, painted circa 1812. Photo courtesy of Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston.

Sources: WikiTree, Wikipedia

Visit www.attawellsummer.com/forthosebefore to learn more about Black history.

Need a freelance graphic designer or illustrator? Send me an email.

#Elizabeth Freeman#MumBet#Mum Bett#Bet#Brom and Bett v. Ashley#Massachusetts#slavery#slavery in Massachusetts#slavery in New England#freedom#emancipation#Theodore Sedgwick#mid 1700s

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mum Bett was one of the first enslaved black American to sue for freedom and win in Massachusetts. As a free woman she took up the name Elizabeth Freeman. She was W.E.B Du Bios great grandmother. Her case served as precedent in the state that brought an end to the practice of slavery in Massachusetts. Freeman's real age was never known, but an estimate on her tombstone puts her age at about 85. She was buried in the Sedgwick family plot in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. She died in 1829. Freeman was among the first enslaved black Americans in Massachusetts to file a "freedom suit" and win in court under the 1780 constitution, with a ruling that slavery was illegal.

Her county court case, Brom and Bett v. Ashley, decided in August 1781, was cited as a precedent in the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court appeal review of Quock Walker's "freedom suit". When the state Supreme Court upheld Walker's freedom under the constitution, the ruling was considered to have informally ended slavery in the state. LIFE & TRIAL: Elizabeth Freeman was illiterate and left no written records of her life. Her early history has been pieced together from the writings of contemporaries to whom she told her story or who heard it indirectly, as well as from historical records.

Freeman was born into slavery about 1742 at the farm of Pieter Hogeboom in Claverack, New York, where she was given the name Bett. When his daughter Hannah married John Ashley of Sheffield, Massachusetts, Hogeboom gave Bett, then in her early teens, to them. She remained with them until 1781, during which time she married and had a child, Betsy. Her husband (name unknown, marriage unrecorded) never returned from service in the Revolutionary War.

Throughout her life, Bett exhibited a strong spirit and sense of self. She came into conflict with Hannah Ashley, who was raised in the strict Dutch culture of the New York colony. In 1780, Bett prevented Hannah from striking her daughter Betsy with a heated shovel, but Elizabeth shielded her daughter and received a deep wound in her arm. As the wound healed, Bett left it uncovered as evidence of her harsh treatment. Soon after the Revolutionary War, Freeman heard the constitution read at Sheffield and these words: “ All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights; among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property; in fine, that of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness." —Massachusetts Constitution, Article 1.

Bett sought the counsel of Theodore Sedgwick, a young abolition-minded lawyer, to help her sue for freedom in court. Sedgwick willingly accepted her case. He enlisted the aid of Tapping Reeve, the founder of America's first law school, located at Litchfield, Connecticut. The case of Brom and Bett vs. Ashley was heard in August 1781 before the County Court of Common Pleas in Great Barrington.

Sedgwick and Reeve asserted that the constitutional provision that "all men are born free and equal" effectively abolished slavery in the state. When the jury ruled in Bett's favor, she became the first African-American woman to be set free under the Massachusetts state constitution. The court assessed damages of thirty shillings and awarded her compensation for their labor. After the ruling, Bett took the names Elizabeth Freeman. LEGACY: The decision in the case of Elizabeth Freeman was cited as precedent when the State Supreme Judicial Court heard the appeal of Quock Walker v. Jennison. Walker's freedom was upheld. These cases set the legal precedents that ended slavery in Massachusetts. Vermont had already abolished it explicitly in its constitution.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1781, a jury in Massachusetts ruled in favor of an enslaved woman known as Bett, granting her freedom—more than 80 years before the Emancipation Proclamation. Her landmark case, Brom and Bett v. John Ashley, Esq., paved the way for the state to effectively outlaw slavery in 1783. She named herself Elizabeth Freeman to reflect her new status.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meet the women who fought in the American Revolution

(Reposted from July 2021)

Something to think about this July 4th - Independence Day

You don’t have to shoot a gun to be a revolutionary.

The U.S. has prospered in part from the contributions made by women throughout history. Let’s take a look at the Revolutionary War that was fought from 1775 to 1783.

Abigail Adams was an early supporter of women’s rights. In fact, at the start of the American Revolution, she wrote a now-famous letter to her husband, John Adams, who was in the process of working on the Declaration of Independence. Here’s an excerpt:

A member of the upper class, Abigail Adams may not have been thinking of all women. However, there were other female revolutionaries at that time who made an indelible mark.

One was Phillis Wheatley. Born in West Africa and sold into slavery at the age of 7, Wheatley worked as a domestic for a Boston family who taught her to read and write. She became an acclaimed poet, and is best known for a letter she wrote in 1776 to George Washington lauding his efforts to free people from colonial oppression. Although it was hard for her to get published as a slave, Wheatley’s poetry is taught today as some of the best this nation ever produced.

A resounding achievement for its time

Although freedom from oppression was the driving mission of the American Revolution, slavery was not addressed for another century, until the Civil War. However, one woman took this upon herself and succeeded—before the Revolutionary War even concluded. This was Elizabeth Freeman, better known as Mum Bette. Also a slave in Massachusetts, Freeman filed a law suit, Brom and Bett v. Ashley. She argued that slavery was inconsistent with the state’s newly ratified constitution. And the Massachusetts Supreme Court agreed! Her case was instrumental in ending slavery in the state. We hear a lot today about “equity.” Elizabeth Freeman made the case for this notion before the U.S. constitution was even ratified.

Going to war

Deborah Sampson was the personification of a ‘strong woman.’ Her father abandoned the family and her mother, with no resources, sent Deborah and her siblings to live with relatives. For a while, Deborah lived with an elderly aunt who taught her how to read. When that woman died, Deborah became an indentured servant. Freed to be on her own at 18, she earned a living teaching school, working in a tavern and becoming a skilled weaver. But she earned her place in history during the Revolutionary War when dressed as a man, she joined an Army unit under the name Timothy Thayer.

Here’s an interesting Wiki on Sampson: “Sampson fought in several skirmishes. During her first battle, on July 3, 1782 outside Tarrytown, New York, she took two musket balls in her thigh and sustained a cut on her forehead. She begged her fellow soldiers not to take her to a doctor out of fear her sex would be discovered, but a soldier put her on his horse and took her to a hospital. A doctor treated her head wound, but she left the hospital before he could attend to her leg. She removed one of the balls herself with a penknife and sewing needle, but the other was too deep for her to reach. She carried it in her leg for the rest of her life and her leg never fully healed.”

Other women raised money for the Continental Army, organized boycotts of British goods, served as spies, messengers, healthcare providers and more. As we approach July 4th, let’s give a special nod to the women who helped set us free.

La Jolie MLN: ”It’s our mission to give young ladies the lessons all of you can share with us. So, let’s share our experiences, strength and stories.

I cordially invite you to join a cohort of empowered women. Please send your stories to [email protected]

0 notes

Photo

Elizabeth Freeman (c.1744 – December 28, 1829), known as Bet, Mum Bett, or MumBet, was the first enslaved African American to file and win a freedom suit in MA. The MA Supreme Judicial Court ruling, in her favor, found slavery to be inconsistent with the 1780 MA State Constitution. Her suit, Brom and Bett v. Ashley (1781) was cited in the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court appellate review of Quock Walker's freedom suit. When the court upheld Walker's freedom under the state's constitution, the ruling was considered to have implicitly ended slavery in Massachusetts. Any time, any time while I was a slave if one minute's freedom had been offered to me, and I had been told I must die at the end of that minute, I would have taken it—just to stand one minute on God's airth a free woman— I would. — Elizabeth Freeman Her real age was never known, but an estimate on her tombstone puts her age at about 85. She died in December 1829 and was buried in the Sedgwick family plot in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. She remains the only non-Sedgwick buried in the Sedgwick plot. They provided a tombstone, inscribed as follows: ELIZABETH FREEMAN, also known by the name of MUMBET died Dec. 28th, 1829. Her supposed age was 85 Years. She was born a slave and remained a slave for nearly thirty years; She could neither read nor write, yet in her sphere she had no superior or equal. She neither wasted time nor property. She never violated a trust, nor failed to perform a duty. In every situation of domestic trial, she was the most efficient helper and the tenderest friend. Good mother, farewell. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence https://www.instagram.com/p/CmtfABjr7x4/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

How an Enslaved Woman Took Her Freedom to Court | Smart News

How an Enslaved Woman Took Her Freedom to Court | Smart News

2022-08-29 09:41:56

A monument of civil rights pioneer Elizabeth Freeman in Sheffield, Massachusetts

Gillian Jones / The Berkshire Eagle via AP

In 1781, a jury in Massachusetts ruled in favor of an enslaved woman known as Bett, granting her freedom—more than 80 years before the Emancipation Proclamation. Her landmark case, Brom and Bett v. John Ashley, Esq., paved the way for the state to…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Elizabeth Freeman (c.1744 – December 28, 1829), also known as Bet, Mum Bett, or MumBet, was the first enslaved African American to file and win a freedom suit in Massachusetts. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruling, in Freeman's favor, found slavery to be inconsistent with the 1780 Massachusetts State Constitution. Her suit, Brom and Bett v. Ashley (1781), was cited in the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court appellate review of Quock Walker's freedom suit. When the court upheld Walker's freedom under the state's constitution, the ruling was considered to have implicitly ended slavery in Massachusetts.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elizabeth Freeman

"Any time, any time while I was a slave, if one minute's freedom had been offered to me, and I had been told I must die at the end of that minute, I would have taken it- just to stand one minute on God's earth a free woman- I would." - Elizabeth Freeman

Elizabeth Freeman was born an enslaved woman in the mid-1700s, in approximately 1744, on the farm of Pieter Hogeboom in Claverack, New York. She was given the name Bet. Freeman was given to John Ashley, who had married Hogeboom's daughter, at seven years old. While owned by Ashley, she is said to have married, although no marriage records exist. She bore a child, called Little Bet. Her husband is said to have never returned from service in the American Revolution.

Freeman always had a strong, unbending spirit. She hated every moment of being enslaved. This clashed with her mistress, Hannah Ashley's views, as Hannah had been raised in the strict Dutch culture of New York. In 1780, Lizzie, Freeman's sister, took a small amount of dough she was using to make a meal for the family and attempted to make a small wheaten cracker for herself. Hannah called Lizzie a thief and attempted to hit her with a heated shovel. The shovel had been in the fire, and the blade of it was red from the heat. Freeman interceded, taking the blow upon her arm instead.

The blow cut to the bone, and her arm never healed exactly as it was. It was nearly useless for the rest of the winter. She never covered her wound, instead using it to embarrass her mistress. When telling the story later in life, she is quoted saying, "Madam never again laid her hand on Lizzie. I had a bad arm all winter, but Madam had the worst of it. I never covered the wound, and when people said to me, before Madam, 'Why, Betty! what ails your arm?' I only answered - 'ask missis!'"

The Ashley home was the site of many political discussions and the probable site of the singing of the Sheffield Resolves, the document from which many of the ideas used in the Declaration of Independence were drawn. Freeman, serving the men participating in these discussions, overheard much talk of freedom, liberty, and revolution.

In 1780, either at a public reading or at one of these gatherings in her master's house, she heard the newly ratified Massachusetts Constitution. Realizing that the document claimed that all men were born equal and had a right to freedom, she sought the counsel of Theodore Sedgwick, a young, abolitionist lawyer. She reportedly asked him, "I'm not a dumb critter; won't the law give me my freedom?"

Freeman wanted to sue for her freedom. After thought and deliberation, Sedgwick took her case. Brom, another person enslaved by Ashley, also wanted to sue for his freedom. Sedgwick accepted his case as well. He enlisted the aid of Tapping Reeve, who founded Litchfield Law School, one of the first law schools in the United States.

Sedgwick and Reeve were the best lawyers in Massachusetts. In their prosecution, they claimed that the words "all men are born free and equal" effectively abolished slavery within Massachusetts.

Brom and Bett v. Ashley was heard before the County Court of Common Pleas in Great Barrington in August 1781. The jury ruled in the plantiffs' favor. Brom and Freeman were awarded damages of thirty shillings and compensation for their work.

Ashley appealed the decision, but later dropped his appeal, apparently having decided that the ruling was binding.

Following the ruling, Ashley asked Freeman to return to his household, where she would be paid for her work. Freeman refused, opting instead to work for Sedgwick. She was his senior servant and the governess of the Sedgwick children until 1808, at which point she moved into her own house closer to her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. She died on December 28, 1829, assumed to be about 85 years of age.

Elizabeth Freeman was the first enslaved woman to successfully sue for her freedom in Massachusetts. Her case was used as precedent in future cases that upheld the freedom of all previously enslaved people and ended slavery in Massachusetts.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Reposted from @theshayharris - My Shero!!! @Regrann from @mediaoutrage1 - @Regrann from @theblaquelioness - Great Read 🤓: Elizabeth Freeman was probably born in 1742, to enslaved African parents in Claverack, New York. At the age of six months she was purchased, along with her sister, by John Ashley of Sheffield, Massachusetts, whom she served until she was nearly forty. By then she was known as "Mum Bett," and had a young daughter known as "Little Bett." Her husband had been killed while fighting in the Revolutionary War. ➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖ One day, the mistress angrily tried to hit Mum Bett's sister with a heated kitchen shovel. Mum Bett intervened and received the blow instead. Furious, she left the house and refused to return. When Colonel Ashley appealed to the law for her return, she called on Theodore Sedgewick, a lawyer from Stockbridge who had anti-slavery sentiments, and asked for his help to sue for her freedom. ➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖ Mum Bett had listened carefully while the wealthy men she served talked about the Bill of Rights and the new state constitution, and she decided that if all people were born free and equal, then the laws must apply to her, too. Sedgewick agreed to take the case, which was joined by another of Ashley's slaves, a man called Brom. ➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖ Brom & Bett v. Ashley was argued before a county court. The jury ruled in favor of Bett and Brom, making them the first enslaved African Americans to be freed under the Massachusetts constitution of 1780, and ordered Ashley to pay them thirty shillings and costs. This municipal case set a precedent that was affirmed by the state courts in the Quock Walker case and ultimately led to the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts. ➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖ After the ruling, despite pleas from Colonel Ashley that she return and work for him for wages, Mum Bett went to work for the Sedgewicks. She stayed with them as their housekeeper for years, eventually setting up house with her daughter. She became a much sought-after nurse and midwife. ➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖➖ #ElizabethFreeman / #MumBett #HerStory #BlackWomenInHistory #BlackHistory #History #LestWeForget #theblaquelioness - #regrann #Med https://www.instagram.com/p/Bt8h987npUb/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=clriepl2zioo

#elizabethfreeman#mumbett#herstory#blackwomeninhistory#blackhistory#history#lestweforget#theblaquelioness#regrann#med

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1781, Quock Walker ran away from “home”.

Born in 1753 an originally believed to be from Ghana, Walker was a slave, owned by Massachusetts slave owner James Caldwell of Worcester County -- just west of Boston. Caldwell promised Walker his freedom once he turned 25 years old, but Caldwell died before the promise was upheld. Nathaniel Jennison, Walker’s owner after Caldwell’s death, refused to give Walker his freedom. So, at 28, three years after the promise, Walker escaped.

Walker went to a nearby farm owned by Seth and John Caldwell, the brothers of James Caldwell. There he was promised a “safe home”. Somehow, Jennison got wind of Walker’s whereabouts, tracked him down and beat him. Walker fought back, suing Jennison for battery.

At this moment in history, the states, later to be known as the United States, were hoping to gain freedom from England. The American Revolution was in full effect. The language determining citizenship, freedom and what it meant to be “a man” in the eyes of the law were up for interpretation.

Two civil cases were heard, on top of one criminal case: Quock Walker v. Jennison. Though the suit originally circled around battery, it became a suit about the legality of slavery. Walker’s lawyers argued against the concept of slavery -- as the practice went against the Bible and the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780. The jury agreed. Walker was a freeman and awarded him 50 pounds in damages. Their decision was appealed and later tossed out, due to a failing to appear on Jennison’s case or papers were improperly filed.

The preamble of the Worcester Anti-Slavery Society (something Jennison would have been enraged to see), 1846 -- Digital Commonwealth

In September of 1781, the Attorney General of Massachusetts brought upon a case on the battery charges and the question of Walker’s freedom to the state’s Supreme Court. The results went unchanged. The Massachusetts Supreme Court found Walker a freeman, citing the Massachusetts Declaration of Rights -- “all men are born free and equal” -- as the basis of its decision. In their review, the court cited Brom and Bett v. Ashley (1781) in their reasoning for the Walker decision. That case concerned an African-American woman named Elizabeth Freeman (known as Bet or MumBet) who sued for her freedom and won -- effectively becoming the first enslaved African American to win a freedom suit in Massachusetts. Both these decisions effectively ended slavery in Massachusetts, though no new laws were put in place. A gradual disappearance of the practice happened over the news one hundred years.

In the 1790 United States census, no slaves were recorded in Massachusetts.

This decision gave Boston -- the state’s largest city and capital -- a glowing destination for runaway slaves and freed people of color. They settled in today’s Beacon Hill community, on the north-side of Boston. Its name comes a former beacon that sat upon the neighborhood’s highest point. By the mid to late 1700s, around more than 1,000 African Americans called Beacon Hill home. Throughout the 1800s and into the 20th century, Beacon Hill became the battling ground for those arguing for emancipation, citizenship, women’s rights and tons of civil rights causes.

Today, Boston’s Black Heritage Trail runs through Beacon Hill, detailing the sites and people of the city’s African-American history. From private homes to schools to meeting sites, the walk takes one on a journey through some of Boston’s (and the country’s) highest and lowest points in its history.

54th Massachusetts Regiment Memorial

The memorial that sits opposite of the Massachusetts State Capitol is a good starting point for the tour. Its depiction of the Massachusetts 54th Regiment is a fairly well-known story in American history.

The regiment was an infantry regiment that saw service during the American Civil War. It was the first African-American regiment created by a northern state during the war, where all the men enlisted were African-Americans. The officers, however, were white men: most notably Robert Gould Shaw, commander of the regiment and a patron of Boston. Shaw came from abolitionist parents and believed his men should be treated as soldiers--regardless of their skin color. He told his men to refuse pay until the government was willing to pay them equally.

Their most famous engagement came at the Second Battle of Fort Wagner in July of 1863. The 54th Massachusetts led a frontal assault on Fort Wagner and paid heavily: 20 were killed, 102 went missing and 125 were wounded. The battle was a Confederate victory, but the battle’s legacy is more important. Shaw died as he led his troops toward the fort, and his body was left in a ditch with his fallen African-American soldiers. Confederate victors thought the gesture an insult to Shaw’s honor; Shaw’s family and friends believed different. “We can imagine no holier place than that in which he lies, among his brave and devoted followers, nor wish for him better company,” Frank Shaw, the commander’s father, wrote to the surgeon of the regiment.

In 1900, William Carney, a sergeant in the 54th Massachusetts regiment, received the Medal of Freedom for his bravery during the Second Battle of Fort Wagner. During the battle, when the outlook of victory was grim, Carney grabbed hold of the regiment’s colors and is said to have shouted: “Boys, I only did my duty; the old flag never touched the ground!”

Today, the memorial sits valiantly in Boston Common. Completed in 1884 by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the 54th Massachusetts’ memory forever lives in for those who pass the impressive site. On top of its important legacy, the memorial serves as a good starting point for Boston’s Black Heritage Trail.

George Middleton House

Walking up Joy Street and two blocks north of the 54th Memorial sits the George Middleton House. Among Beacon Hill’s brick facades and streets, this building sticks out. Its gray facade is notable and it looks out-of-place, essentially squeezed from its surroundings.

The home, built in 1797, was the home of Patriot soldier George Middleton. During the American Revolution, Middleton served as a commander of the Bucks of America. They were a Boston-based military unit who were part of the Massachusetts militia. Little is known and no official records exist, but the Massachusetts Historical Society has a flag belonging to the group -- leaving some credence to their existence.

After the war, Middleton joined others in the African-American community to Beacon Hill and became one of its first residents -- building the home at 5 Pinckney Street that stands today. He championed civil rights after the war for African-Americans, organizing the African Benevolent Society in 1796. At the turn of the century, Middleton turned his attention to ending slavery throughout the country. He worked with community leaders and wrote pamphlets to help the cause gain steam. He died in 1815.

The house today is privately owned, but marks a vivid reminder for Boston’s post-colonial history.

Phillips School

Head down Pinckney Street, where Anderson Street meets Pinckney, and you wind up at the Phillips School.

Built in 1824, the school was primarily a white-only school. In 1855, Massachusetts law required schools to integrate; Phillips Schools obliged with the law. The school became one of Boston’s first integrated schools. During its segregated days between 1835 and 1855, Phillips School was considered the best for children in Boston.

The school rests only blocks away from the Abiel Smith School, Boston’s public school for African-American children (we’ll get there in a second). The African-American community of Boston fought for integration throughout the 19th century and, when integration happened in 1855, were quick to act. African-American children began attending Phillips School almost immediately.

Today, the former school is a private residence. But the box-like structure of the former school is hard to miss in Beacon Hill.

John J. Smith House

Blending in with the rest of the houses at the end of Pinckney Street, the John J. Smith House sits upon a noticeable slope. In 1820, John J. Smith was born in Richmond, Virginia. He arrived in Boston around twenty years later and became a vital figure in Boston’s African-American community.

First, Smith was a barber. But cutting hair was not the only purpose of his barbershop; he began using his barbershop to organize and meet with abolitionists throughout the city. His home at 86 Pinckney Street was a stop on the Underground Railroad, as he aided escaped slaves to freedom. He helped establish emancipation and justice for escaped slaves such as Shadrach Minkins and Lewis Heyden. Charles Sumner, the United States Senator of over twenty years during the mid-to-late-1800s, was a friend and client of Smith. According to the National Park Service, when Sumner was not found at his office or at home, he was said to be found at Smith’s.

During the 1850s, John J. Smith fought for equal rights in Boston’s public schools -- connecting him to the previously mentioned Phillips School. In the 1870s, Smith’s daughter Elizabeth became one of the first African-American teachers in Boston. Georgiana, Smith’s wife, was a notable member of the community, as well. She worked for the Freedman’s Bureau. Public service was something ingrained in this family throughout their lives.

Smith’s post-Civil War workload is equally as impressive. He served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, its third African-American member, and was appointed to serve on the Boston Common Council -- the first African-American to do so. On top of all of these achievements, he successfully worked to have the first African-Americans appointed to work for Boston’s police force.

He died in November of 1906, a glowing reminder of the importance of public service.

Charles Street Meeting House

A little detour of a couple blocks is involved to get to Charles Street, where the Charles Street Meeting House resides.

Originally, the site was the Third Baptist Church, built in 1807. Segregation practices were in force during the early run of its existence. African-Americans were allowed only in the gallery and were not permitted to take part in community events organized by the church. Those rules were not in place for long.

In 1836, Timothy Gilbert invited African-Americans to join him in the pew seating during a service. The results were unsuccessful. Gilbert was expelled from the church; the seating arrangements remained. (Gilbert helped find the Tremont Temple -- today known as the country’s first integrated church.) However, over time, the Third Baptist eventually became more lenient in its inclusion of African-Americans.

Despite the Third Baptist Church’s treatment of African-Americans in its early years of existence, members were mostly anti-slavery in mind. Noted African-American speakers such as Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass gave speeches at the church. Notable abolitionists Wendell Phillips and Charles Sumner also spoke at the Charles Street Meeting House.

After the Civil War, various churches and organizations used the church’s space. Today, it is home to various businesses as office space.

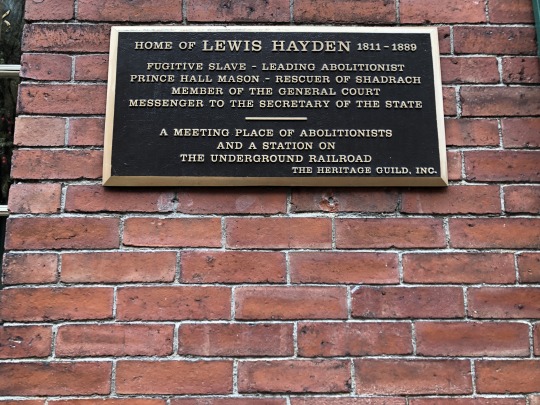

Lewis and Harriet Hayden House

Remember Lewis Hayden? He was one of the escaped slaves that John J. Smith helped in the mid-1800s. Up the street and a couple blocks over from the Charles Street Meeting House -- on Phillips Street -- sits the house of the Haydens.

Lewis was born in 1812 in Kentucky. Hayden was frequently sold in his early years. In the mid-1830s, he married Esther Harvey and had a son. They were all sold to noted United States Senator Henry Clay, who later sold Esther and their son to the Deep South. Hayden never saw them again.

In 1842, after years of learning to read and desperately fighting for his freedom, he married Harriet Bell -- an enslaved woman. Harriet had a son, who Lewis treated like his own. Fearing his family would be split up again, he began planning to escape north. I

Around 1844, Hayden met Calvin Fairbank, a Methodist minister involved with the Underground Railroad. He asked Hayden, “Why do you want your freedom?”. Hayden replied, “Because I am a man.” Fairbank was convinced.

He, along with Delia Webster, a teacher from Vermont working in Kentucky, helped Hayden and his family escape north. Fairbank and Webster were both caught after helping the Haydens escape. Webster served a two-year prison sentence; she was pardoned. Fairbank was sentenced to 15 years. He was pardoned after serving four.

Hayden ended up in Canada, then Detroit, Michigan, ultimately moving to Boston in 1846. He ran a clothing store and became a community leader. In 1850, the family moved into the house that is now part of the Black Heritage Trail. Their home became a welcoming spot for escaped slaves or anyone of color. Between 1850 and 1860, they Hayden house was always full of tenants and residents (according to the Boston Vigilance Committee); they took in anyone that needed help. Among the causes that Hayden thought his time worthy, he helped collect money for John Brown, as Brown prepared for his raid on Harper’s Ferry.

During the Civil War, Lewis Hayden helped recruit for the 54th Massachusetts and later served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives. In 1889, Lewis died. Four years later, his wife Harriet followed him to the grave. In death, the two remained a beacon for hope and good fortune to those of need: Harriett bequeathed money to Harvard Medical School, setting up a scholarship for African-American students.

John Coburn House

Continue down Phillips Street and one ends up at the John Coburn House (the darker brick one at the end).

Coburn, born in 1811, was an African-American abolitionist and became one of Boston’s wealthiest residents. He lived most of his life at the house (from 1844 to his death in 1873) that is now a part of this trail -- at 2 Phillips Street. Coburn’s money came from his ownership in a clothing store on Brattle Street in Boston. However, there is some evidence that he also took in money from running a gaming house for “wealthy Bostonians”.

In 1845, Coburn became the treasurer of the New England Freedom Association. Their goal: to aid escaped slaves and fight for their emancipation. Throughout the local papers, Coburn advertised safe lodging for those in need and advertise for his group. In 1854, he founded the Massasoit Guards, an African-American military force to help police Beacon Hill. Coburn was the company’s captain. However, the Massasoit Guards was never officially recognized by Massachusetts.

Along with Lewis Hayden, Coburn helped John Brown’s raid by recruiting volunteers. Coburn died in 1873. He married Emeline Coburn; they had one adopted son, Wendell Coburn, who was deeded all his father’s belongings after his death.

Smith Court Residences

Circle around Cambridge Street and head down Joy Street, again, until you come across a house tucked away by a dead end. This bright structure is part of the Smith Court Residences.

The structure pictured, known as the William C. Nell House, is part of the residences that sit on Smith Court. They are some of the oldest structures in the area’s African-American history. Built between 1798 and 1800, many African-American families called this building-- and those surrounding it--home. The house was a boarding house and many walked through its doors throughout its existence. 3 Smith Court (the one pictured) was home to the area’s longest resident was James Scott, who lived on the premises from 1839 to 1865, and owned the property from 1865 to his death in 1888. He was a clothing dealer and assisted escaped slaves to freedom. (He was arrested once for helping to aid the rescue of Shadrach Minkins, though was later acquitted).

During the 1850s, William Cooper Nell resided on Smith Court. Nell was Boston’s most notable proponents of school integration. He knew and worked everywhere in hopes to see African-Americans living and working side-by-side with their fellow white Americans. He became a noted writer, historian and is remembered as the country first African-American historian.

The buildings surrounding the notable 3 Smith Court structure housed many African-American families. All of which did their part in helping others find safe shelter, food and, in many times, a friend.

African Meeting House

Turn around.

Across the street from the Smith Court Residences is the African Meeting House -- almost the end of the tour.

Built in 1806, the African Meeting House was site of the first African Baptist Church of Boston. It is the oldest “extant church building in the country”, along with being known as the first African American Baptist church created north of the Mason-Dixon line. This was a church built by African-Americans and for African-Americans. The church originally had 24 members, 15 of which were women. Cato Gardner spearheaded its construction, raising $1,500, and his name is still enshrined outside the buildings walls.

The African Meeting House was Boston’s “spiritual center” for its African-American community. It served as the “chief cultural, educational and political nexus” for African-Americans living in Boston. Its speakers throughout the years showcase the church’s importance: William Lloyd Garrison, Maria Stewart, Wendell Phillips Sarah Grimke and Frederick Douglass. Among the many organizations to utilize its space was the New England Anti-Slavery Society, which was founded at the shite in 1832. Furthermore, the 54th Massachusetts used the space as a recruitment post in 1863.

Today, it is a museum and a recommended site to visit when in Boston. The pews are most of the construction is original. One can almost hear Frederick Douglass or any of its noted speakers throughout its history shout and cry for freedom.

Abiel Smith School

Alas, we come to an end.

Next to the African Meeting House is the Abiel Smith School. When Abiel Smith, a white philanthropist, left $4,000 for the African-American children of Boston in his will, community organizers used the money to help fund a school. The building was constructed in 1834 and was the first public school for African-American children -- which was aptly named after Smith. Up until 1835, African-American children went to school next door at the African Meeting House. Now, they had a building of their own.

William Cooper Nell, who later lived across the street from the school, attended and won (along with two other students) the Franklin Medal for academic achievement. They were not allowed to attend ceremonies in downtown Boston. Nell got in anyways, convincing a waiter to let him help serve the white guests. It is said it was during this ceremony that Nell said, “God helping me, I would do my best to hasten the day when the color of the skin would be no barrier to equal school rights.” Perhaps attending this school and experiencing segregation helped Nell fight so furiously for integration later in life.

At the end of the 1840s, many African-American parents took their children out of the Abiel Smith School -- in protest to help integrate Boston schools. It worked, as noted earlier. The Abiel Smith School was closed the same year Boston outlawed “separate schools”.

And, with that, we close the tour of Boston’s Black Heritage Trail. It’s beautiful walk through Boston’s Beacon Hill community and highly recommended for any visitor or resident. For those who have not made the trip, I hope this guide helped explore Boston’s African-American community and history.

(Thanks to the National Park Service and the Museum of African American History for the research, quotes and information.)

#african american history#history#boston#massachusetts#united states#african american#slavery#54th massachusetts#quock walker#frederick douglass#john coburn#lewis hayden#harriet hayden#john j smith#george middleton#writing#my writing#tour#photography

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Petitioning For Freedom: Elizabeth Freeman

Photo: Mum Bett, aka Elizabeth Freeman, aged 70. Painted by Susan Ridley Sedgwick, aged 23. Watercolor on ivory painted circa 1812. Photo courtesy of Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston.

“Any time, any time while I was a slave, if one minute's freedom had been offered to me, and I had been told I must die at the end of that minute, I would have taken it—just to stand one minute on God's earth [sic] a free woman I would.”

Elizabeth Freeman, also known as Mum Bett, was among the first black slaves in Massachusetts to file a "freedom suit" and win in court under the 1780 constitution, with a ruling that slavery was illegal. She was prompted to file suit after hearing these words following the Revolutionary War: “All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights; among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property; in fine, that of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness,” Massachusetts Constitution, Article 1.

Photo: Elizabeth Freeman statue in the historical galleries at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Her county court case, Brom and Bett v. Ashley, decided in August 1781, was cited as a precedent in the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court appeal review of Quock Walker's "freedom suit". When the state Supreme Court upheld Walker's freedom under the Constitution, the ruling was considered to have informally ended slavery in the state.

Learn more about African Americans that used the legal system to pursue their freedom: bit.ly/2vIyfEE

478 notes

·

View notes

Text

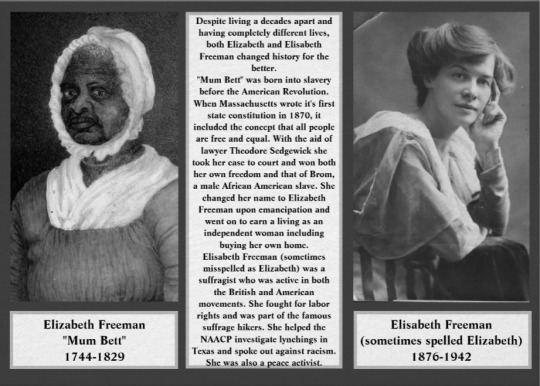

Elizabeth Freeman and Elisabeth Freeman

Elizabeth Freeman/Elisabeth Freeman

While these two women share the same name, their lives could not have been more different. However they both fought for equality and both deserve to be remembered.

Elizabeth “Mum Bett” Freeman (1744?-1829) was born into slavery in the colony of New York decades before the American Revolution. She moved to Sheffield, Massachusetts when her mistress married Colonel John Ashley. In 1773, Ashley helped draft the Sheffield Declaration which stated that “mankind in a state of nature are equal, free, and independent of each other, and have a right to the undisturbed enjoyment of their lives, their liberty and property.” Similar language was used in both the Declaration of Independence (1776) and the State Constitution of Massachusetts (1780). Bett and a male slave named Brom asked prominent lawyer Theodore Sedgwick who had also helped draft the Sheffield Declaration to help win their freedom through the courts using the Massachusetts State Constitution. It was both a challenge and a test case for Sedgwick and Ashley fought to keep Bett and Brom enslaved. In the groundbreaking case Brom and Bett v. Ashley, they legally won their freedom. She changed her name to Elizabeth Freeman. Ashley offered her work as a paid servant but she chose employment as a domestic at the Sedgwick household. She became a prominent healer, midwife, and nurse and was eventually able to buy her own home. She is the only non-Sedgwick buried in the “inner circle” of the family plot in Stockbridge, MA.

Elisabeth Freeman, also sometimes spelled Elizabeth Freeman (1876-1942) was born in England and came to America around the age of 4. She worked in both the British and the American Suffrage Movements. Most famously, she was part of General Rosalie Jones�� suffrage hikers who marched in the 1913 Suffrage Procession in Washington D.C. (Episode 62b) and famously smoked in public during a banquet as a defiant act (which was featured in a Virginia Slims “You’ve come a long way, baby” campaign). She championed worker rights. As a suffragist she included talking about women of color. She helped the NAACP investigate lynchings in Waco Texas in 1916, and spoke out against racism. She also worked as a peace advocate. Her activities were intertwined with almost every progressive movement that happened during her lifetime. Below is a link to a scrapbook of her many accomplishments.

Sources:

This is information from the National Women’s History Museum about African-American Elizabeth “Mum Bett” Freeman

https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/elizabeth-freeman

Information from the same source about white suffragist Elisabeth/Elizabeth Freeman

https://www.womenshistory.org/elisabeth-freeman

Despite the misspelling,this website is an interactive scrapbook of Elisabeth/Elizabeth, the white suffragist.

https://elizabethfreeman.org/

And this one is a website also about Elisabeth/Elizabeth the white suffragist

https://elisabethfreeman.org/

#suffragettecity100#mum bett#Elizabeth freeman#elisabeth freeman#suffragist#suffragette#slave#slavery#civil rights#racism#lynching#NAACP#suffrage hike#equal rights#equality#women's history#black history#african american history#abolition#boston history#american history#19th amendment#freedom#women's rights#human rights

0 notes

Photo

#empowering Less than one year after the adoption of the Massachusetts State Constitution, a brave enslaved woman challenged the document’s proposed principles. Motivated by the promise of liberty, Elizabeth Freeman, born as “Mum Bett,” became the first African American woman to successfully file a lawsuit for freedom in the state of Massachusetts. This case marked the beginning of a group of “freedom suits” that would ultimately lead the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court to outlaw slavery in their state. In May of 1781, Sedgwick and his team filed a document called a “writ of replevin” with the Berkshire Court of Common Pleas. This document ordered Colonel Ashley to release Bett and Brom. The Berkshire Court stated that Bett and Brom were not Colonel Ashley’s legitimate property. However, he refused to release them from his possession. By August 1781, the case went to the County Court of Common Pleas of Great Barrington in the case known as Brom and Bett v. Ashley. During the case, Sedgwick argued that the Massachusetts Constitution outlawed slavery. The jury agreed with Sedgwick and decided that Bett and Brom were not Colonel Ashley's property. Bett and Brom were set free and awarded 30 shillings and the costs of the trial. Please continue reading this POWERFUL story at: https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/elizabeth-freeman #slavery #african #powerful #foughtforfreedom #powerful #freed #first #africanamerican #woman #success #lawsuit #won #blackhistorymonth #blackhistory365 @brownstonersbedstuyhousetour https://www.instagram.com/p/B8zE_XvlYhW/?igshid=15vyxidjbdfgl

#empowering#slavery#african#powerful#foughtforfreedom#freed#first#africanamerican#woman#success#lawsuit#won#blackhistorymonth#blackhistory365

0 notes

Text

Meet the women who fought in the American Revolution

(Reposted from July 2021)

You don’t have to shoot a gun to be a revolutionary.

The U.S. has prospered in part from the contributions made by women throughout history. Let’s take a look at the Revolutionary War that was fought from 1775 to 1783.

Abigail Adams was an early supporter of women’s rights. In fact, at the start of the American Revolution, she wrote a now-famous letter to her husband, John Adams, who was in the process of working on the Declaration of Independence. Here’s an excerpt:

“I desire you would Remember the Ladies. If particular care and attention is not paid to the Ladies, we are determined to ferment a rebellion and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation.”

A member of the upper class, Abigail Adams may not have been thinking of all women. However, there were other female revolutionaries at that time who made an indelible mark.

One was Phillis Wheatley. Born in West Africa and sold into slavery at the age of 7, Wheatley worked as a domestic for a Boston family who taught her to read and write. She became an acclaimed poet, and is best known for a letter she wrote in 1776 to George Washington lauding his efforts to free people from colonial oppression. Although it was hard for her to get published as a slave, Wheatley’s poetry is taught today as some of the best this nation ever produced.

A resounding achievement for its time

Although freedom from oppression was the driving mission of the American Revolution, slavery was not addressed for another century, until the Civil War. However, one woman took this upon herself and succeeded—before the Revolutionary War even concluded. This was Elizabeth Freeman, better known as Mum Bette. Also a slave in Massachusetts, Freeman filed a law suit, Brom and Bett v. Ashley. She argued that slavery was inconsistent with the state’s newly ratified constitution. And the Massachusetts Supreme Court agreed! Her case was instrumental in ending slavery in the state. We hear a lot today about “equity.” Elizabeth Freeman made the case for this notion before the U.S. constitution was even ratified.

Going to war

Deborah Sampson was the personification of a ‘strong woman.’ Her father abandoned the family and her mother, with no resources, sent Deborah and her siblings to live with relatives. For a while, Deborah lived with an elderly aunt who taught her how to read. When that woman died, Deborah became an indentured servant. Freed to be on her own at 18, she earned a living teaching school, working in a tavern and becoming a skilled weaver. But she earned her place in history during the Revolutionary War when dressed as a man, she joined an Army unit under the name Timothy Thayer.

Here’s an interesting Wiki on Sampson: “Sampson fought in several skirmishes. During her first battle, on July 3, 1782 outside Tarrytown, New York, she took two musket balls in her thigh and sustained a cut on her forehead. She begged her fellow soldiers not to take her to a doctor out of fear her sex would be discovered, but a soldier put her on his horse and took her to a hospital. A doctor treated her head wound, but she left the hospital before he could attend to her leg. She removed one of the balls herself with a penknife and sewing needle, but the other was too deep for her to reach. She carried it in her leg for the rest of her life and her leg never fully healed.”

Other women raised money for the Continental Army, organized boycotts of British goods, served as spies, messengers, healthcare providers and more. As we approach July 4th, let’s give a special nod to the women who helped set us free.

La Jolie MLN: ”It’s our mission to give young ladies the lessons all of you can share with us. So, let’s share our experiences, strength and stories.

I cordially invite you to join a cohort of empowered women. Please send your stories to [email protected]

0 notes

Photo

Elizabeth Freeman (c.1744 – December 28, 1829), known as Bet, Mum Bett, or MumBet, was the first enslaved African American to file and win a freedom suit in MA. The MA Supreme Judicial Court ruling, in her favor, found slavery to be inconsistent with the 1780 MA State Constitution. Her suit, Brom and Bett v. Ashley(1781) was cited in the MA Supreme Judicial Court appellate review of Quock Walker's freedom suit. When the court upheld Walker's freedom under the state's constitution, the ruling was considered to have implicitly ended slavery in MA. Any time, any time while I was a slave if one minute's freedom had been offered to me, and I had been told I must die at the end of that minute, I would have taken it—just to stand one minute on God's airth a free woman— I would. — Elizabeth Freeman ELIZABETH FREEMAN, known by the name of MUMBET died on Dec. 28th, 1829. Her supposed age was 85 Years. She was born a slave and remained a slave for nearly thirty years; She could neither read nor write, yet in her sphere she had no superior or equal. She neither wasted time nor property. She never violated a trust, nor failed to perform a duty. In every situation of domestic trial, she was the most efficient helper and the tenderest friend. Good mother, farewell. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence https://www.instagram.com/p/CYBrLeGLP5EJnwlj0kCGh8WrSrDgiV9ICffSUo0/?utm_medium=tumblr

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elizabeth Freeman

With the help of Theodore Sedgwick, a Stockbridge attorney and abolitionist, she pled her case in the Court of Common Pleas in Great Barrington in August 1781. When the jury ruled in Bet’s favor, she became the first African-American woman to be set free under the Massachusetts constitution. Her case, Brom and Bett v. Ashley, served as precedent in the State Supreme Court case that brought an end to the practice of slavery in Massachusetts.

0 notes