#1971年

Text

1971

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

It’s the weekend feel me….

#truestory#moments#own your life#tupac#tupac shakur#close enough#ns/fw content#bbc bull#taurus ♉️#secure contain protect#18+ only#taurus#our characters#challengeaccepted#chaos#my generation#generation x#mine#who you really are#real life#reality shifting#realista#the best#90s#1971年#one man band#one man army#one more chapter#on the hunt#law of attraction

0 notes

Photo

Super nostalgic! I guess young people don't know... #赤電話 #新型赤電話機 #1971年 #昭和46年 #公衆電話 #電話 #publictelephone #telephone #電話機 #NTT #日本電信電話株式会社 #ガチャガチャ #カプセルトイ #ガシャポン #Gachagacha #plastic #capsuletoy #toy #ueno #上野駅 #Uenostation #日本 #Japan #東京 #Tokyo #ivvaDOTinfo #ivva (上野駅) https://www.instagram.com/p/CqX7rtQyVUd/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#赤電話#新型赤電話機#1971年#昭和46年#公衆電話#電話#publictelephone#telephone#電話機#ntt#日本電信電話株式会社#ガチャガチャ#カプセルトイ#ガシャポン#gachagacha#plastic#capsuletoy#toy#ueno#上野駅#uenostation#日本#japan#東京#tokyo#ivvadotinfo#ivva

1 note

·

View note

Text

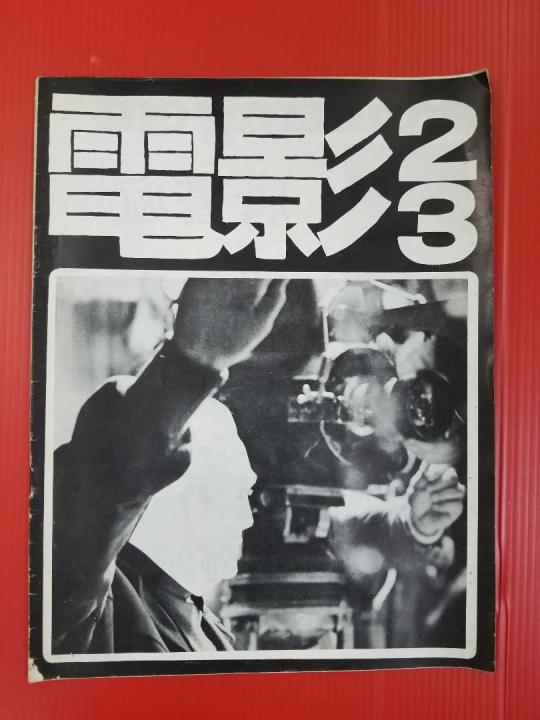

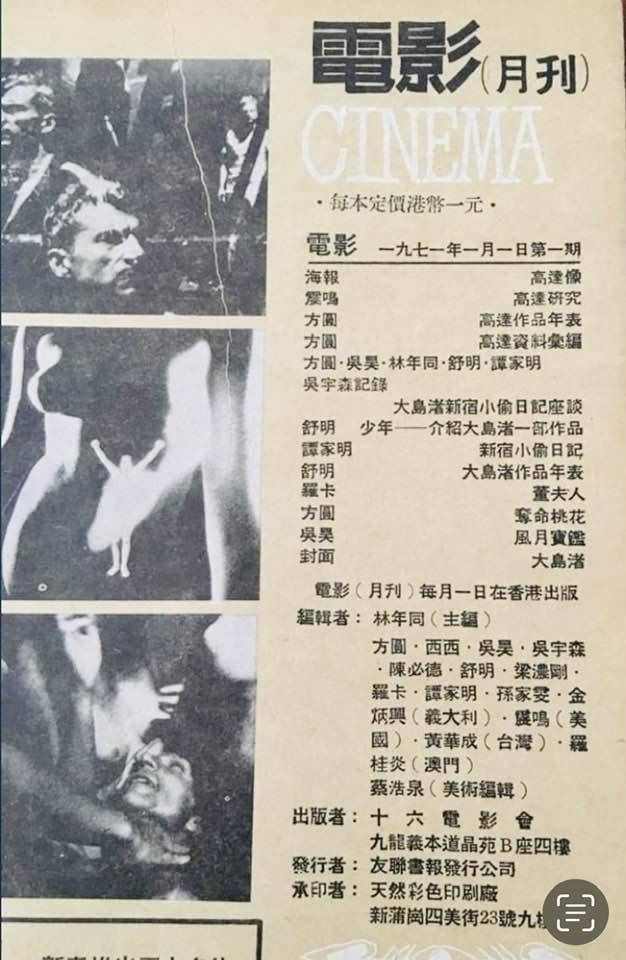

《電影》(月刊)2/3 合刊號

1971

69 notes

·

View notes

Photo

アサヒグラフ 1971年8月13日号

朝日新聞社

表紙=砂漠で出あった婦人たち(タール砂漠の入口・ジョドプール付近で)

カラー連載ルポ「インド放浪」〈1〉タール砂漠をゆく

#アサヒグラフ 1971年8月13日号#asahigraph#アサヒグラフ#thar desert#タール砂漠#great indian desert#anamon#古本屋あなもん#あなもん#book cover

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chihiro Iwasaki, Tulip and Baby, 1971.

いわさきちひろ チューリップとあかちゃん 1971年

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kayama Natsuko 加山なつこ

Debut: 1989

1971年1月31日

Height: 163cm B98(Hカップ) W60 / H93

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

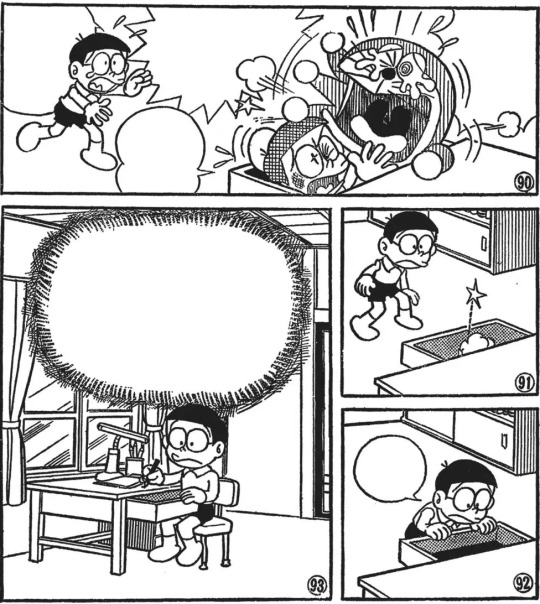

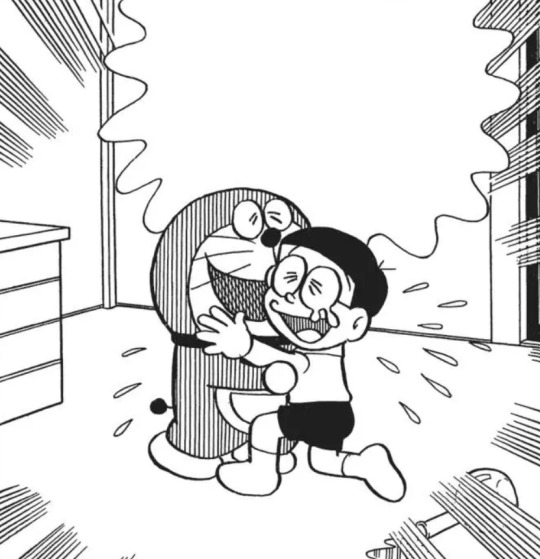

How does Doraemon end? There have been 3 different endings.

Doraemon was not yet published in the 5th-grade magazine 小学五年生 in 1971, so an ending was made for its 1970-1971 run in the 4th-grade 小学四年生.

In ドラえもん未来へ帰る, the Nobis are plagued by time travelers coming to their house, including tourists and even a wanted murderer. Because of all the trouble time travelers have made for people of the past, time traveling is banned and Doraemon is made to go back to the future.

Another ending was made for Doraemon's 1971-1972 run in 小学四年生. In ドラえもんがいなくなっちゃう!?, Doraemon worries Nobita will rely on him too much and makes the hard decision to leave, but he and Sewashi promise to cheer Nobita on from the future.

But when Doraemon started running in the 6th-grade magazine 小学六年生 in 1973, a preview undoing this ending showed Doraemon returning to Nobita.

The most famous ending is 1974's さようなら,ドラえもん ("Goodbye, Doraemon"). Doraemon's reason for leaving is not explained, but he says he has to go back to the future. He and Nobita stay up to spend their last night together, but Nobita gets into a fight with a sleepwalking Gian. Though beaten badly, Nobita makes Gian surrender by wearing him down, and Doraemon leaves the next morning, satisfied that Nobita can look out for himself.

Sometimes claimed to be the conclusion Fujiko Fuijo meant for Doraemon, but this is not confirmed. A month later, 帰ってきたドラえもん ("Doraemon Comes Back") was published. When Nobita drinks the "800-Lies Potion" (ウソ800) Doraemon saved for him and says Doraemon won't ever be back, the potion makes what he said into a lie, so Doraemon comes back.

Because all of these "endings" were invalidated by later stories, there is no official ending to Doraemon's story. All other Doraemon endings you may have seen (like Nobita growing up to be a famous roboticist after Doraemon runs out of power) are fan theories.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

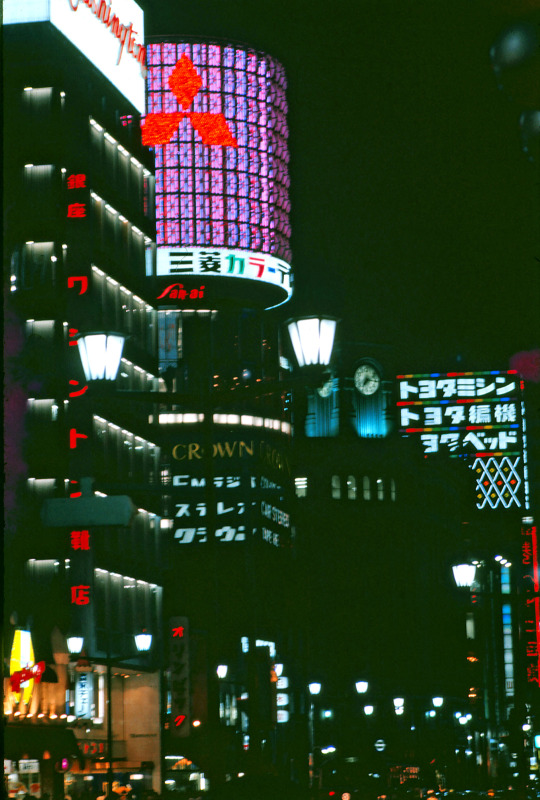

Ginza (1971)

994 notes

·

View notes

Text

Li Nezha, Protector of the Queer Youth in Taiwan. Part 1.

Hello Tumblr!

I have been hard at work assembling the first few posts for this blog, but I would like to start with something relatively lighthearted. Our topic for today is modern depictions of Li Nezha, or most specifically, Nezha as a queer icon in Taiwan.

In the interest of maintiaining a somewhat steady flow of posts, the original form of this post has been broken up. The following posts will expand on the points made here and additionally will discuss the impact of Nezha in the Taiwanese Queer Film scene and it's possible influence on Nezha (2019).

This is an unexpected angle, but one I dearly want to share. Please continue under 'keep reading' if this also interests you.

Before reading a handful of discomforting topics arise. There is mention of suicide in relation to the original myth, the concept of filial cannibalism in relation to the original myth, and discussion of the AIDS crisis.

I would first like to state that the cultural differences between Taiwan and Mainland China are not many, in several aspects they are the same - barring current geopolitical factors. Many fled Mainland China during 1949, a great deal settling in Taiwan. Naturally they brought their culture and worshipped deities with them, Nezha among the wide range of gods brought.

In more recent times the widespread popularity of Nezha in Taiwan is fascinating, though he may not have as many statues or dedicated temples, his ability to excite the younger generations is unmatched by the rest of his pantheon. Overall, Nezha ranks seventh most popular when measured by publicly available shrines or temples (1). But if we are to measure popularity based on the amount of statues that exist Nezha is only outnumbered by the earth-deity Tudi Gong (2). Thus it is understandable Nezha himself became a reflection of the interests of the youth, especially if one considers his image to be of someone unafraid to challenge authority and those that oppress you.

The idea of a queer Nezha is a fairly novel thing though. 1971 saw the publishing of 'Nezha in the Investiture of the Gods' or Fengshenbang li de Nezha (封神榜裡的哪吒) by Xi Song which served almost to fill in numerous gaps in his personality as well as add a more psychological aspect to his rebellion against his father. The novel introduces the father as extremely strict, his brothers envious of him, and a mother who loves but cannot understand him; our result is a deeply melancholic Nezha who frequently ponders the meanining of his own life (3).

Any semblance of homosexual tendency is largely absent until the end of the novel which coincides with the killing of Ao Bing in the original Canonization of the Gods. Nezha is bathing in the river here as well, except he sees Ao Bing through the water's surface. Nezha wants to reach through the water and hold him, and the two play together for a while before Nezha accidentally kills Ao Bing (4). Rather than be demanded to repent, the Nezha here punishes himself for the accident.

Many films concerning Nezha to this point focused more on martial arts spectacles rather than his temperament and personality. However 1992 saw the release of the film 'Rebels of the Neon God' by Tsai Mingliang, though not adapted from the Nezha origin story, concerns the problem of self-indulgent youth in modern society. Interestingly the Chinese title Qingshaonian Nezha (青少年哪吒), can be read two ways: Young Nezha or The Youth as Nezha.

His (Nezha's) name is mentioned three times over the course of the film. The first instance is when one of the youthful protagonist's (Xiaokang) mother is explaining to her husband their son is so misbehaved because he is the reincarnation of Nezha. The second is when two of the protagonists (Xiaokang and Ah Ze) enter a dispute, one of their motorbikes defaced with the phrase "Nezha was here". The final time is when these same protagonists are lamenting their poor luck and are instructed to worship Nezha.

Being a gay man himself it isn't surprising that the homoeroticism portrayed by Xiaokang is later elaborated upon in Mingliang's 'Vive l'amour' (1994) where the quiet Xiaokang is attracted hopelessly to the rowdy playboy character of Ah Rong, so much so that Xiaokang kisses Ah Rong without his knowledge. It concludes with Xiaokang and his father participating together in a dubious homoerotic setting together before recognizing each other in 'The River' (1997).

These films were released surrounding Tsai Mingliang's 1995 documentary about how the AIDS crisis was wracking Taiwan, and against the director's wishes, Mingliang focused heavily on the gay men the disease was affecting most in an attempt to dispel the misinformation about the disease itself and the gay men it was affecting. The previously mentioned 'Rebels of the Neon God' (1992) only featured one explicit mention of the AIDS crisis, Xiaokang vandalizes the side of Ah Ze's motorcycle in bright yellow paint "AIDS". This action is arguably an allegory of Xiaokang's repressed homosexual desires towards Ah Ze (5), the use of the HIV virus synonymous with homosexual engagement - despite it being well known in 1990's Taiwan that there were multiple modes of transmission.

Of course other interpretations of this scene exist, but for our purposes today, it is not only Xiaokang's projection of his own desires but a very literal representation of the idea of a 'contagion' - or the circumstances that draw previously unrelated individuals together. The vandalism of the motorcycle may also be seen in this light (6).

Is it worth drawing comparisons in assuming Xiaokang and all of his homoerotic tendencies is meant to be a stand-in for Nezha himself? I think so. The film (Rebels of the Neon God) presents numerous cases that enforce this idea if you are not yet convinced.

As previously mentioned Xiaokang's mother states that he is a reincarnation of Nezha, a conclusion she reached after seeing a fortune-teller and told as much. It is important to state that the original myth features a Nezha slicing his flesh open to return to his mother, and removed his bones to return them to his father. At first glance it appears to be a case of filial cannibalism (a post topic I am drafting) meant to strengthen the bond between parent and child - but the purpose within the myth is to sever that relationship completely. It can be argued this very literal severing helped bring Nezha into the hearts of the youth who were alienated.

Xiaokang's mother explains this to her husband upon arriving home, telling her husband that Nezha was said to hate his father Li Jing more than anything else, briefly mentions his surname to also be Li, and outright blames Nezha for Xiaokang's poor relationship with him. Upon overhearing this, Xiaokang pretends to be posessed by Nezha before his father launches a rice bowl at his head. The ambivalence of Nezha 'returning his flesh' seems to almost mirror the animosity Xiaokang and his father have throughout the film.

Even the English title 'Rebels of the Neon God' can be read as sharing homophonic resemblance to the name Nezha. 'Neon God' can be a rereading of 'Nezha' in that the first character of his name can also be pronounced as '-nai' which becomes an exact homophone for the Chinese term for neon, while the second character '-zha' is a suffix that plainly suggests deification.

To wrap up this post I would like to thank you for joining me on this foray of a more modern take on Nezha's significance, his overwhelming modernity carrying numerous modes of importance depending on where you are looking. He has not shed his origin myth, rather it informs how he is percieved more than ever - his severing of paternal ties no longer a case of an unfilial child but of someone standing up for themselves in the face of oppression. And it is perhaps this that makes him so attractive to both the young and old of Taiwan, all subjected to the terror and violence of the Chinese Communist Party.

Thank you once more, and I hope to see you again in part 2.

Citations:

(1) Li Fengmao, “Cong Nezha taizi dao Zhongtan yuanshuai: zhongyang-sifang siwei xiade

hujing xiangzheng,” 41–43.

(2) Tsai Wentin, “Taitzu, the Child God,” 53–55.

(3) Xi Song, “Fengshenbang li de Nezha,” 209. A translated portion of Nezha's monologue here is as follows "Oh, Master, my birth is a mistake with no reason at all. Since my childhood, I have understood that I am reared by an overbearing mother and a father with much too high expectations. They seem to have never cared about my actual existence, but intenselyrestrain me with the correct direction of their thinking."

(4) Xi Song, “Fengshenbang li de Nezha,” 217.

(5) Ji Dawei, "Wo kan gu wo zai: chengzhang dianying yu shenfen rentong," 95-105. Dawei's 1996 examination is as follows. "Perhaps Xiaokang resents the fact that Ah Ze is sleeping with a woman, or perhaps he is cursing Ah Ze as homosexual, and thereby taking the identity he himself dislikes, and displacing it onto the figure of the Other. Xiaokang is not sexually active, and therefore he despises those who are and struggles to reject sex altogether. He is terrified he might become a homosexual, and therefore he first verbally attacks others, and then projects onto them the suspicion of homosexuality."

(6) Carlos Rojas, "Nezha Was Here": Structures of Dis/placement in Tsai Ming-liang's "Rebels of the Neon God", 76.

If timestamps for cinematic moments mentioned through this post are requested, I am happy to provide them.

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

中平卓馬 《サーキュレーション―日付、場所、行為》 1971年

日曜日

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

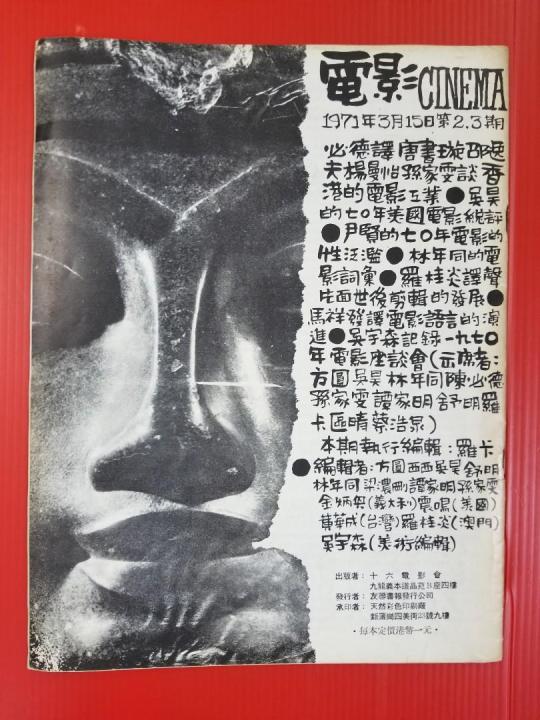

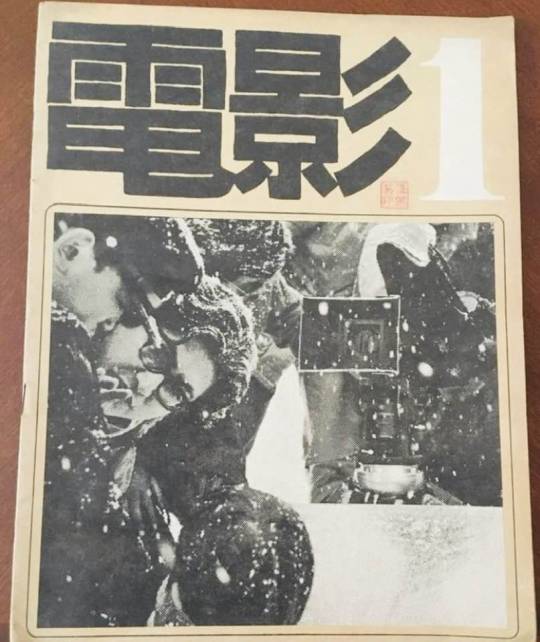

《電影》(月刊)創刊號

1971

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

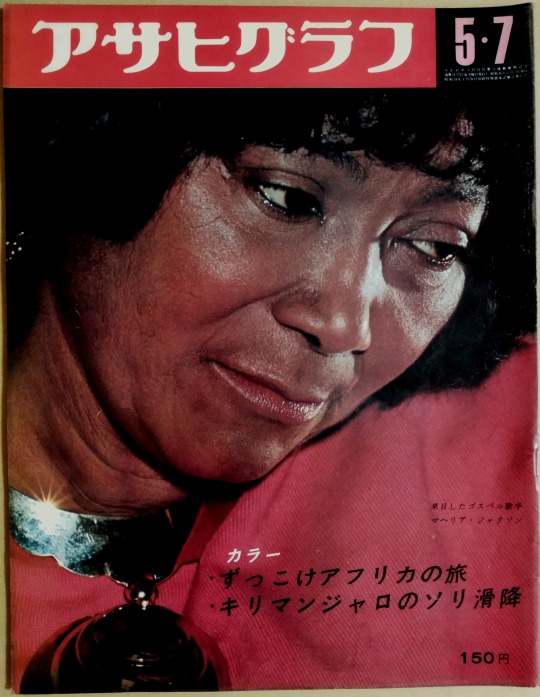

アサヒグラフ 1971年5月7日号

朝日新聞社

表紙=来日したゴスペル歌手マヘリア・ジャクソン

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chihiro Iwasaki 'Uchi no nyaa nyaa(My home's kitty)' from 'Akachan no uta' (Songs of baby), Doshinsha, 1971.

いわさきちひろ 「うちのにゃあにゃ」『あかちゃんのうた』(童心社)より 1971年

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

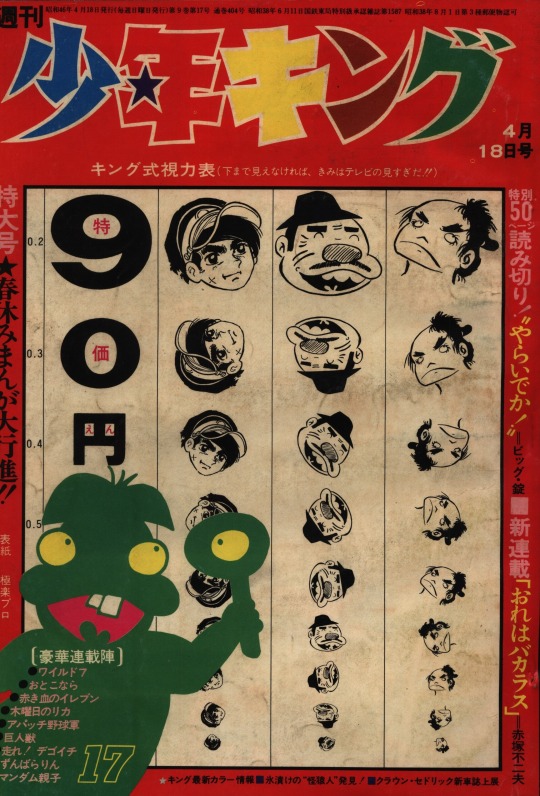

Weekly Shōnen King (週刊少年キング) / Shōnen Gahōsha (少年画報社) / 19th Apr 1971 issue

7 notes

·

View notes