Text

An In or Out Moment Is Upon Us

There’s a line in the Haggadah that seems to me especially meaningful this year. And, although my letters to you all have been getting darker and darker as the year has progressed since last October, the line in question—when read in the correct light and with the correct background information—that line contains a message of hope that I think may be just the thing for all of us as we live through our annual festival of freedom and feel, it seems with each passing week, less certain where this will all lead.

The line opens the long Magid section in which seder-meal participants fulfill the mitzvah of telling the story of the Exodus from Egypt. The setting really could not be better known. The leader uncovers the matzot, lifts the plate, and recites words we’ve all heard a thousand times. “This is the bread of affliction. Let all who are hungry come and eat…and let us gather together next year in Jerusalem.” Most seder-regulars can easily recite the words from memory. At some tables, they are sung aloud, which only makes it easier to remember them from year to year. But hiding behind the words is a riddle that will feel particularly relevant to this nightmarish year through which we have all been living since last October.

The invitation to the hungry to come and join in the feast is suggestive of the natural sense of hospitality that Jewish people bring easily to the celebration of Jewish holidays. But there is a problem here, and it has to do with the second part of that invitation, the part represented above by the three dots that separate the invitation to the hungry and the prayer that we all have seder together next year in Jerusalem. The familiar words, kol di-tz’rikh yeitei v’yifsach, are often mistranslated as “Let all who are in need come and celebrate Passover with us.” That makes it sound like a mere restatement of the opening remark: “let those who are hungry come and eat / let those who have no seder to attend feel welcome at ours.”

So that’s a nice sentiment. But that’s not precisely what the words mean. The Torah enjoins upon the Israelites the eternal obligation to celebrate Passover by offering up the sacrifice called the paschal offering or, more commonly in Hebrew as the korban pesach or the zevach pesach and then by consuming its meat on Erev Pesach, on the Eve of Passover. That being the case, a more literal translation would be something like “Let all enter who need to share our korban pesach, our paschal offering.”

And that too, of course, is a noble thought. The Torah says unequivocally at Exodus 12:8 that “you shall eat the meat [of this sacrifice] on that night; broiled in fire and with matzah and bitter herbs shall you eat it.” So what could be more natural than helping others perform the very mitzvah your own family has already gathered to undertake?

But there’s a detail that needs to be considered: the Torah specifically requires that the Israelites consume the sacrifice in chavurot, which is to say: in pre-formed groups constituted of the specific sponsors of the specific offering they will then consume together. And, indeed, this is the law. Maimonides, for example, writes unequivocally that “the paschal offering may only be slaughtered as a specific offering for its specific sponsors,” who become the people thus entitled to consume it (Hilkhot Korban Pesah 2:1). So how can the seder leader blithely invite any in need to eat the korban with his or her own family? Such people specifically cannot accept the invitation without breaking the law.

So that’s the riddle. What the “real” answer is, who knows? But what the riddle means to me, and particularly in this year of pogrom and war and surging anti-Semitism, is that sometimes you need to step around your normal practice for the sake of a greater good. Yes, the invitee—the specific person the seder leader is addressing when inviting the hungry to come eat and the needy to share in his or her family’s paschal sacrifice—that person being invited in should have signed up for his own sacrifice, should have sponsored a korban pesach in the specific way required by law. But that’s not what happened! And who can say why not? Was the invitee too poor, too shy, or too unfamiliar with the law properly to have dealt with its requirements? Was the invitee held back by physical disabilities, or by mental or emotional ones? Was the specific person being invited in a traveler, a stranger, or perhaps an alienated local who up until that very moment was certain that the very last thing he or she wanted was to do the whole Pesach thing with someone else’s family? Whatever! This person has somehow appeared at the door. The time limit for slaughtering the pesach is long past. The kohanim, the Temple priests, are all off to attend to their own seder meals with their own families. The Temple itself is shut down for the night, its nighttime security detail in place but otherwise empty. The moment has clearly passed to do this the right way. And yet, as the burden shifts from obligation to generosity, from harshness to kindness, from halakhah to aggadah, the host, accepting the situation not as it ought to be or could be but as it actually is, turns to the person standing at the door and, preferencing the real over the ideal, invites that person in to join the family inside and to participate in celebrating Passover by consuming the flesh of the sacrificial offering with which the festival shares its name. The folk genius of the Jewish people allows for things like this, for people knowingly to step occasionally around the rules for the sake of a greater good.

And that is where we are today in the wake of the Simchat Torah pogrom. What is needed, more than anything really, is for the Jewish people to set aside the political or even religious debates that divide us and to face the future united as one people possessed of one Torah and devoted to the service of the one God. As everybody knows all too well, we are a fractious people. Arguing is what we do best. (The old joke about “two Jews, three opinions” is funny and not funny at the same time.) But the bottom line is that what we need to do now is to come together. We don’t all have to agree about everything. We certainly don’t all have to like Bibi or his politics, and neither do we all have to agree whether the IDF has done all it could to free the hostages held captive in Gaza. We certainly don’t have to agree with anything our own President or Vice President have said about Israel over the last half year, both speaking so regularly out of both sides of their own mouths that we barely even notice the disconnect between today’s comment and yesterday’s and the day before’s. But what the Haggadah is saying is that we have to open the door and invite all in who are somehow still on the outside wondering if they even would be welcome at a seder without having first signed up to sponsor a korban pesach in the Temple.

What that line in the Haggadah about the korban pesach and the unsigned-up stranger at the door is there to teach us is that the pursuit of the greater good will always be the wiser choice. That thought should be our watchword as we negotiate these stormy seas on which we are all afloat this year: the key is draw into our ranks all who would seated at our table and then, united and with one voice, to face the world and demand justice—justice for the captives in Gaza, justice for the people whose own lives were ruined on October 7 or whose loved ones were murdered, justice for Israel in the international halls of justice that so frequently, almost routinely, treat Israel unfairly and unreasonably harshly. If we can’t speak as one now, then when exactly will we? And if not now, then when?

If we can manage that, we’ll have done a lot. Yes, there will be those who cannot bring themselves to stand with Israel or with the Jewish people. I regret that, but I also accept it—but I am thinking about swelling our ranks, not thinning them. And so, even with the seder meals behind us now, I invite you all to join me in opening up the doors—of our homes, of our synagogues, of our communities—to all those Jewish people (and they are legion) on the outside and inviting them in to stand with Israel and to stand with all of us who stand with Israel. And allies in the non-Jewish world whose hearts beat with Israel are welcome in my house too. There are moments in history when you have to stand up or back off, to be in or out, to declare yourself part or apart. This, I think (and, yes, fear) is one of those moments.

0 notes

Text

Pesach 2024 - Leil Shimmurim

History is filled with Rubicon moments, moments at which the course of history is altered by an event so widely understood to be of colossal importance that everything that follows feels related to that specific juncture in time, to that specific event. Pearl Harbor was that kind of moment in history. 9/11, too. So must have been also July 4, 1776. And the original Rubicon moment—when Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon River into Italy in January of 49 BCE and thus initiated the insurrection that led to the end of the Roman Republic and, eventually, to the reorganization of the nation as the Roman Empire with Caesar’s biological nephew and adopted son Augustus as its first emperor—that was (obviously) the first of them all. The famous words Caesar spoke aloud as he crossed the river into Italy, “the die is cast,” sums up the moment aptly: just as you can’t unroll dice, so did Caesar mean to say that his act of leading an army across the border into Italy could not be undone and would have to be allowed to lead wherever it went as the future unfolded in the wake of his decision. In the history of the Jewish people, Pesach itself is the original Rubicon moment. And it involved crossing a body of water as well!

Was October 7 such a moment for Israel? Was it one for Hamas? Or was it one for both, and also for diasporan Jews in all the various lands of our dispersion? I suppose those questions could conceivably all have different answers, but it doesn’t feel that way to me: as the months have passed since that horrific day last fall, things feel to me more and more as though the Simchat Torah pogrom permanently altered the course forward into the future for all directly and indirectly concerned parties. As Pesach approaches, this notion of a Rubicon moment has become the lens through which I feel myself called to think of the Simchat Torah pogrom.

The specific way in which the conflict in Gaza has poisoned the atmosphere not solely on our college campuses, but even in our nation’s high schools and elementary schools, is by now common knowledge, as is also the way that this conflict has opened the gates to the expression of overt anti-Semitism in the American work place and at other public events that feel totally unrelated to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict like the Christmas Tree lighting in Rockefeller Center last December. Nor are the halls of government immune: the fact, once unimaginable, that a member of Congress could formally decline to condemn people in her own district chanting “Death to America” at an anti-Israel rally and that that refusal be greeted by her colleagues with an almost universal shrug, is only this week’s example of how things have changed for Jewish Americans in the last half year. That people at the highest echelons of our American government could overtly—and without any sense of shame—suggest that American material support for Israel could, and possibly even should, be conditional on the elected leaders of Israel obeying the instructions of their American masters rather than those of their own constituents is just further proof that October 7 was a Rubicon movement for us all.

But history is not all Rubicon moments. Two weeks ago, I wrote to you about the slow deterioration of the Israelites’ status in ancient Egypt as year after year passed until their enslavement ensued almost naturally. Could slavery have been averted? Surely, it could have been: the Israelites had scores upon scores of years to pack up and go back to Canaan, but chose instead to remain permanently in Egypt on the assumption that their status would never change, that they would always be welcome, that no one would ever resent them as privileged foreigners living off the fat of somebody else’s land. I won’t repeat here what I wrote there, but the bottom line was (and is) that they could have saved themselves but, because there was no specific Rubicon moment, no pivot, no event that changed everything, they apparently chose to assume that nothing was changed at all. And then, just like that (or so it must have seemed), they were slaves possessed of no civil rights at all in a world in which midwives were charged not with assisting women in labor but with murdering the babies born to them.

I’ve written before about my relationship with Erna Neuhauser, my parents’ next-door neighbor. Born in 1898, Erna was in her 60s and early 70s when I was a teenager. But, long before that, she was a young married woman with a young daughter in Nazi Vienna, the city of her birth and the place in which she grew up. Some readers may recall that I’ve mentioned many times that Erna was a childhood friend of the woman later known as Miep Gies, the woman who risked her life years later to hide Anne Frank and her family in German-occupied Amsterdam. But the reason I mention her today is not related to Miep Gies’s story, but to her own. Erna was the first Shoah survivor I knew intimately. Of course, she never let anyone call her that because she was, she always insisted, not a survivor at all: she, her husband Ernst, and their daughter Liesel had been able to escape Vienna in 1938, first traveling to Sweden (where her brother had acquired residency earlier on and was able to sponsor them as refugees) and then to New York, where they settled and lived out their lives. But, also of course, she was a survivor—of the Nazification of Austria, of the intense anti-Semitism Anschluss brought in its terrible wake, of the degradation experienced daily, sometimes hourly, by the Jews of Vienna. And it was her story that framed my first effort to think seriously about the Shoah and to establish my own relationship to the events of those horrific years.

It was from Erna that I learned that the difference between Rubicon moments and non-Rubicon ones is not as clear as historians sometimes make it out to be. Yes, the moment Hitler annexed Austria—the event then as now known simply the Anschluss, the “Annexation”—was the Rubicon moment back across none could step. But it only seemed that way after the fact and what really happened was not one disastrous transformation from being welcome, respected citizens to despised Untermenschen, but the slow, step-by-step deprivation of the rights and privileges to which all had become accustomed. Jews couldn’t get their hair cut in non-Jewish barbershops. Jews could no longer ride the streetcars. Jewish children could no longer attend public schools. Some patriotic souls hung on, certain that things in their beloved homeland would soon improve. Others fled—some to America, others to the U.K. or to Sweden, still others to British Palestine. Many committed suicide in despair. I remember Erna saying that things somehow changed slowly and quickly at the same time. I’m feeling that right now in our nation, that sense that things are unfolding quickly and slowly somehow at the same time.

Wasn’t it just yesterday that Jewish parents would have been overjoyed to send a child to Harvard or to Stanford no matter what the cost? When did it feel reasonable not to wear a kippah on the subway or even on the LIRR? At what point did it feel wiser for Jewish teachers in New York City’s high schools not to mention their pro-Israeli sentiments for fear of being attacked by their own students? When did it start to feel normal for synagogues to hire armed guards to protect worshipers? When did I stop speaking in Hebrew on the phone in public places? I can’t even say that I don’t do that anymore—but I certainly don’t do it if I think someone might overhear me.

This isn’t the Weimar Republic we’re living in and it certainly isn’t Nazi Vienna. The center, at least so far, is definitely holding. Both presumed nominees in this fall’s presidential election self-present as allies of the Jewish community. The issue of anti-Semitism on campus is finally being addressed by people with the authority to effect real change. And, at least eventually, I still think reason will prevail, that people will come back to their senses and understand that Israel is not only our nation’s sole true friend in the Middle East, but also a fully reliable ally. But I am also sensitive to Pesach—now almost upon us—not solely being our annual celebration of freedom, but also our annual opportunity to obey the Haggadah’s famous injunction to think of ourselves not only as now-free people, but as once-enslaved ones…and to use that opportunity to consider how the Israelites ended up as slaves after having watched small micro-aggressive incidents become more and more overt, more difficult to endure, more suggestive of what was soon to come.

At Exodus 12:42, the Torah calls the eve of Pesach by the mysterious name leil shimmurim, a night of “keepings,” of “things kept or guarded.” What that means exactly has been a matter of debate for millennia. But for me it means: a night of holding on to history, of seeing time present through the lens of time past, of understanding our current situation as a function of what we’ve already experienced. Pesach is a hopeful holiday that celebrates the liberation of slaves from their bondage. But there is a monitory side to Pesach as well, one intended to make us think carefully about the present by focusing our gaze on stories from the past and in their light formulating our hopes for the future. Elijah comes to my seder table specifically with his intoxicating promise of redemption and survival. But Erna also comes, and her message is far more sobering than intoxicating…even after four cups of wine.

0 notes

Text

Like a Letter Left Unread

The whole eclipse thing earlier this week made a big impression on me, but not (maybe) for the reason you’d think.

It all started when I mentioned to one of my grandchildren that I hope it will be a clear, non-cloudy day when the sun goes into eclipse. This was met with the kind of equanimity only a child can muster up effortlessly: “Me too, Saba. But if it’s so cloudy you can’t see anything, the next eclipse is in just twenty years and we can see it then.” Well, okay, I thought, and just how old will I be on August 23, 2044? You see where we’re going here: I surely do hope to be somewhere in the summer of 2044 looking up through safety sunglasses at a clear, cloudless sky as the moon passes before the sun and hides it totally from view for a few minutes. But suddenly the whole discussion made me feel mortal—not fragile especially, just more aware of where I am actuarially than I generally enjoy being. Of course, it could have been way worse: she could have reminded me that Halley’s comet is due back in the summer of 2061.

How to relate to a total eclipse of the sun is a different matter entirely, however. For most moderns, it’s just a thing—something that happens every so often and creates a dramatic effect for a few minutes, then stops happening. Not good or bad, not something overly to focus on and certainly nothing to fear. But our sages in ancient times were less certain: possessed of the conviction that the Creator at least occasionally speaks through the medium of Creation itself, they sought meaning in all sorts of natural phenomena that moderns tend to wave away. Nor is this solely a rabbinic thing—the biblical story of Noah ends with God’s observation that rainbows are not just natural phenomena that sometimes occur, but signs from God that there will never again be a flood that wipes out humanity as was the case in the days of Noah and his ark. And it’s for just that reason that tradition dictates that we recite a short prayer—just a few words acknowledging the rainbow as a symbol of optimism and hope—when we see a rainbow. How often does this happen? Often enough! Joan and I saw the most beautiful rainbow in Niagara Falls, New York, just last week on our drive to Toronto. And, yes, I said the blessing.

But the rabbis were less sure about eclipses. There’s a semi-famous passage in the Talmud (at Sukkah 29a) that declares that any solar eclipse should be taken as a bad sign for the world, for example. And the text then goes on to flesh that thought out with an elucidatory parable: a solar eclipse, they taught, is God behaving roughly in the manner of an earthly king who prepares a giant banquet for all of his servants, perhaps as a way of thanking them for their loyal service. But then, suddenly, the king becomes aware of some specific way in which his servants have conspired to do him ill. So what does he do? He can’t cancel the banquet entirely—that would be (I’m guessing) bad form—but what he can do is instruct his personal valet to remove the torches that had been illuminating the banquet hall. And that, according to the parable, is what a solar eclipse is like: suddenly aware of some way in which humanity has failed to behave honorably or decorously but not quite prepared to wipe clean the slate as in Noah’s day (and which God had promised never again to do anyway), God simply darkens the sun as a way of expression divine displeasure.

Other sages, however, took a more nuanced view. Rabbi Meir, for example, agreed that both solar and lunar eclipses are bad omens, but solely for the Jewish people not for the entire world. And he too had a parable to back up his lesson. The situation that pertains during an eclipse, he taught, bodes poorly for the Jewish people only because they are m’lummadin b’makkoteihem. That’s not that easy an expression to translate, which even Rabbi Meir apparently thought might be the case. And so he too offered up a parable to make his point a bit clearer. A solar or lunar eclipse, he taught, is like when a teacher comes into the classroom and he is already holding a giant razor strop, the kind that was apparently used in Rabbi Meir’s day to punish school children for their poor behavior. Who gets the most jumpy upon noticing the strop in the teacher’s hand, Rabbi Meir asked rhetorically. And he then answered his own question: the student who is beaten with it the most often gets the most nervous—because that student supposes that the teacher is intending to beat him again. And that is what it means to be m’lummadin b’makkoteihem, as above: Jewish people are so used to suffering and being again and again beaten down, must not it be they specifically who are being prompted to fear the worst when the sun disappears and the world is plunged into darkness? (The words literally mean “well-versed in their own beatings” or something like that.)

Still other rabbis took an even more nuanced approach. Solar eclipses, they opined, are bad news for everybody, whereas eclipses of the moon are meant specifically to augur bad times for the Jewish people. And the rationale behind this approach has its own logic to it: the Gentile nations, who use a solar calendar to count off their years of their lives, are addressed through the solar event, whereas Jews, who maintain a mostly lunar calendar, God admonishes by making the moon disappear briefly from the nighttime sky. And then they go on to discuss solar eclipses, discussing the specific significance of the location of the sun in the sky when the eclipse takes place and assigning specific meaning in terms of the disaster soon to ensue to the hue the sun in eclipse takes on.

And then, as if all this weren’t enough, the Talmud goes on to quote an ancient source that lists the specific sins for which a solar eclipse may reasonably be taken as the divine response. That thought—including the peculiarly modern-sounding horror of people in an urban setting simply ignoring a woman calling out for help in fending off a would-be rapist—founders, though, on the fact that it isn’t correct: people fail to show proper respect for deceased community leaders all the time (another sin on the list) and yet the sun does not go into instant eclipse as a response!

Is there anything to any of this? We moderns understand what eclipses are and why they occur, and we also understand that they are fully naturally phenomena that are not related to, much less triggered by, the behavior of Jewish or non-Jewish terrestrials. As a result, our natural response is to turn away from tradition and make a kind of smug virtue out of feeling grateful that we know better. The Talmud, after all, is filled with ancient ideas about all sorts of things that we moderns, who understand that epilepsy is a disease and not a function of the circumstances under which the epileptic individual was conceived, can only smile at. And, indeed, the Talmud is filled with all sorts of medical observations that no one today considers even remotely to be scientific truths. So it would be more than reasonable just to wave all this away. But I have a different idea I’d like to propose, one a bit less literalist and more fanciful, but also, I think, reasonable.

In a long, fascinating passage towards the end of the talmudic tractate Berakhot, the Talmud offers up a detailed lesson regarding the correct way to interpret dreams. It’s a long passage filled with lots of theories about the meaning of dreams, but the basic principle set forward is that the importance of dreams depends fully on their interpretation. In other words, nothing in a dream means anything at all until the dream is ably interpreted by the kind of oneirocritic trained to offer up that kind of interpretation. So the dream contains solely the meaning we find embedded in it, a principle later to serve as the foundation of Freudian dream analysis. When the Talmud says that a dream left uninterpreted is like a letter left unread, it means precisely that: leaving a dream uninterpreted deprives it of the chance of having any impact on the dreamer at all, just as an unread letter has no potential to affect the person to whom it was addressed at all.

Maybe we should apply that kind of thinking to eclipses. I was in Glen Cove last Monday at 3:18 PM and, looking up at the sky through the special glasses, I saw almost all of the sun disappear behind the moon. As the sky darkened and the temperature fell, I felt the trappings of civilization falling away as I stood there under the sky and watched the sun that defines our lives here in earth darken. I felt small and fully insignificant as the planet on which I was standing and the sun it orbits and the moon that orbits it began their brief cosmic dance. My interpretation of the whole event, therefore, had to do with humility. And with resolve: more than I do usually, I felt the presence of the Earth, alive and not alive at the same time, sturdy yet fragile, immeasurably big yet also cosmically insignificant. And I felt a renewed sense of responsibility for the planet, for its climate and its ozone layer, for its air and its water, for its wellbeing and security. My interpretation of the eclipse, therefore, is that the sun and the moon teamed up to remind us that we are, at best, stewards of this world we inhabit. And that the degree to which we shuck off that feeling of insignificance that the eclipse did its best to instill in us—that will also be the degree to which we have left this rare celestial phenomenon as a letter left unread, as a dream left uninterpreted.

0 notes

Text

Israel in Egypt

Slow change is hard to notice. This, we all know from daily life: you hardly notice children growing taller if you see them every single day, whereas you are often amazed at how much those very same children have grown if you haven’t seen them in a few months. The same is true about gaining or losing weight: you can see changes easily in people you see once a year that you would hardly notice at all if you saw that same person daily. And the same is true about far more challenging aspects of life than height or weight: it’s always hard to notice incremental change.

With Pesach approaching, the story of Israel in Egypt is on my mind. There are a thousand different ways to think about that famous story, but the one that seems the most relevant—and chillingly so—to our current situation has to do with just that notion, with the concept of incremental change.

Sometimes, the Torah teaches its best lessons so subtly that it is entirely possible to miss them entirely. When Jacob comes to Egypt, he is awarded a private interview with Pharoah, something that must have been as rare and special in his day as it would be today. Their conversation is an interesting one in lots of different ways, but the most interesting part is when Jacob tells Pharaoh that he is 130 years old. It sounds a bit like a throwaway line to most: Pharaoh asks and he obviously has to answer, so he does. And yet there is a lot packed into that single number.

Jacob comes to Egypt in the second of the seven years of famine. That would make him 135 when the famine ended five years after his arrival and life in Egypt returned to normal. But the Torah makes the point later on that Jacob lived to be 147 years of age. So why, Scripture prompts us to wonder, didn’t Jacob and his clan return to Canaan once the famine ended and they needed no longer to fear starvation back at home? (Jacob would have had a full dozen years to get that all organized.) The question is unasked, so also unanswered. But then Scripture tosses some new numbers into the mix.

Joseph, who was sold into slavery at seventeen and who was thirty when he became the grand vizier of Pharaoh’s Egypt, presided over the seven years of plenty that preceded the seven years of famine. That would make him thirty-nine years of age when his father and his father’s family arrived in Egypt in the second year of famine, and forty-four years of age when, five years later, the famine ended. That being the case, he would have been fifty-six when, twelve years later, Jacob died. But the last lines of Genesis report that Joseph lived to be 110 years of age, which means that the Israelites would have been living in Egypt for something like fifty-four years when Joseph died.

Eventually, a Pharaoh came to the throne who, to quote Scripture, “knew not Joseph” and that was the Pharaoh who enslaved the Israelites. Were there Pharaohs in between the one who welcomed Jacob’s family to Egypt and the one who knew not Joseph? The Bible doesn’t say. But what it does say—albeit subtly—is that the Israelites were in Egypt for more than half a century, and possibly a lot longer than that, when their situation had finally deteriorated to the point at which they could no longer just go home and, in fact, they had no choice but to endure the misery that slavery brought them in that land not their own.

They should obviously have left when the famine ended, but they didn’t. I suppose they eventually realized that. (After the fact, everybody’s a chokhom.) But my question has to do with the years between the end of the famine and the rise of the Pharaoh who knew not Joseph.

Let’s imagine another half-century passed as things began to deteriorate for the Jews of Egypt. At first, it was small things, what moderns would call instances of extra-legal microaggression. Then as now, these kind of things were easy to shrug off: an overheard insult, a vulgar joke, an instance of being made to feel unwelcome in familiar places—in the locker room at the gym or at the pool or in the supermarket. But public opinion began slowly to shift as the Israelites were increasingly less welcome in their host country, increasingly resented, increasingly disliked. Could they have stemmed that tide by acting forcefully to make things right? There’s no answer to that question, but in my fantasy version of the long stretch of time I’m imagining between Jacob’s death and the Israelites’ eventually enslavement, things began slowly to snowball as the Israelites’ prosperity was resented, their clannish ways disliked, and their refusal to embrace the national religion of Egypt found more and more insulting.

But the Israelites failed to notice any of that. Or to take any of it too seriously. They withdrew into their communities, failing entirely to understand the depth of the antipathy they were dealing with as they circled their wagons and took pride in the degree to which they had managed to keep the world at bay while, at the same time, missing the point about the level of rage that was slowly reaching boiling point in the world in which they actually lived. In other words, they managed to make a virtue about looking inward when what they really should have been doing is looking out at the storm brewing on the horizon and working to fix things before they truly became unfixable.

Could they have returned to Israel? Was that door ever really shut? Or did the Israelites just like living in the world’s most sophisticated superpower, in a center of world culture, in one of the handful of nations never to have been conquered or subjugated by any hostile neighbor ever? Did they think of themselves as Egyptians? It’s a less silly question than it sounds at first. They must have spoken Egyptian. (How else could have communicated with the citizens of their host nation?) They surely must have had contact with Egyptian officials of various sorts. I imagine that, at least in the beginning, they did think of themselves as some version of Egyptians, perhaps some going so far as to think of themselves as Egyptians-of-Israelite-origin, something in the away the more assimilated Jews of Germany used to refer to themselves as deutsche Staatsbürger jüdischer Herkunft, as German citizens of Jewish origin. (This was only ironic after the fact, obviously.) But things got worse, not better. At first no one even noticed, not really. And by the time they all fully understood how things were, they were making bricks for Pharaoh and building his storage cities as his fully unwilling slaves.

We just came back from a few days in Canada visiting with Joan’s family. Everything seemed normal. But things have changed, almost without any of the locals noticing. The Canadian government, once a staunch defender of its citizens civil rights, has outlawed kosher slaughter. Of course, they didn’t put it that way and said instead that they were enacting a new law that would guarantee that animals be slaughtered in a way that they argued would be more humane than the way Jewish tradition requires and they simply didn’t care if that basically meant outlawing kosher slaughter. (This from a nation that sanctions as legal the clubbing of baby seals because outlawing such a barbaric practice would offend the basic right to cultural self-preservation of the Inuit nation that inhabit Canada’s Arctic. For more on that, click here.) Of course, Canada is not alone. Denmark, Belgium, Sweden, Estonia, Slovenia, and Finland have also outlawed kosher slaughter, in effect saying that Jews are tolerated in those places as long as they don’t mind abandoning their own traditions and living as others would prefer them to live. But my point today is that none of this is evident—and not even slightly—on the streets of Toronto. Everything really did feel normal. When I asked some of the people we met about the kosher meat thing, they mostly shrugged. Yes, they agreed, it’s terrible. But what can you do? We’ll just import meat from the States. So it will be a bit more expensive—it already costs a fortune so it will cost slightly more of one. It’s just the government. It’s just the Liberal Party. It's just the New Democrats. It’s just the Greens. It’s just Justin Trudeau. It’s always just something! No one said any of this to me in Egyptian, but they might as well have! (To be fair, the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs, a kind of umbrella group representing Canada’s Jews, is suing the government to force them to amend the legislation. But I don’t think anyone is especially hopeful this effort will be successful.)

And that brought me to thinking about our nation in that same light. Things have changed quickly and slowly at the same time. Some of our most prestigious college campuses have become centers of intolerance, including of the violent kind, aimed directly at Jewish students. Some of our most revered public officials—including the President, the Vice President, and the Senate Majority Leader—have spoken hostilely, even crudely, about the duly elected Prime Minister of Israel. (The President’s endless critique of Donald Trump’s refusal to accept the settled results of a fairly-held election seems only to apply to our own country, not to our allies.) Suddenly, things feel different. The bond between Israel and our nation feels less strong, less sturdy, less un-unravelable. The degree to which the Trump campaign has begun openly to mix evangelical tropes into its campaign rhetoric feels ominous, not merely exclusionary and off-putting. The subtle sense that it might be wiser not to wear a kippah on the subway, a feeling I had previously only felt strongly on the Metro in Paris, suddenly feels fully reasonable.

Everybody knows that you can boil a frog alive in an open petri dish if you only heat the water slowly enough. Whether that’s actually true or not, I have no idea. (The blogosphere is equivocal.) But the Haggadah’s famous remark that Jews are required at Pesach to think of themselves as though they personally were slaves in Egypt and were personally liberated from their bondage by God’s might hand and outstretched arm—that remark seems to me to include the parallel obligation to think about all the years that led into slavery, decades of ever-increasing signs of degeneration blithely ignored by all until it really was too late.

0 notes

Text

Purim 2024

Purim begins on Saturday night. Are we all ready? More or less, we’re ready. It feels like we’re ready.

And it also feels like we couldn’t be less ready. In normal times, Purim is fun, a riotous celebration of victory over Haman’s minions and of the truth behind Mordechai’s hopeful promise to Esther that, come what may, salvation eventually comes from somewhere. When I was much younger, I was more than slightly conflicted about Purim. That’s our plan, I thought to myself back then: to face impending genocide and to find comfort in the assumption that salvation will eventually come from somewhere? Great plan! Of course, in the Megillah, salvation actually does come from somewhere as the pieces of the intricate plot slowly fall into place. Haman’s preening megalomania makes it impossible for him not to appear at both of Esther’s banquets. Achashveirosh, confronted with the thought that Haman was personally attacking his queen in his own palace, somehow finds it in him—entirely uncharacteristically—to act forcefully and even to summon up a bit of sarcasm as he condemns Haman to death. And, of course, Esther has amazingly and completely unforeseeably ended up in precisely the right place to set the whole counterplot in motion, the one that features the Jews utterly defeating their would-be murderers instead of themselves being annihilated by those same thugs and haters.

But much-younger-me was unimpressed. The whole story in the Megillah hangs on so many unlikely details, of which the most shocking one has to be the decision of Mordechai in the first place to send Esther off for her overnight “interview” with the king to see if she can beat the gigantic odds against her and somehow become the queen of Persia. And there are lots more unlikely twists and turns in the story. That’s what makes it such a good story. But does that make it a cogent plan for the Jewish people? That was the question that younger-me pondered as, year after year, I showed up to hear the Megillah and to try to get in the mood to feel good about the one pogrom in these last 2.5 millennia that backfired and led to the bad people being defeated instead of the good people.

Eventually, much-younger-me grew up to be less-younger-me (and eventually much-less-younger-me), a working pulpit rabbi tasked with making sense of every Jewish holiday including, of course, Purim. Unexpectedly, I grew into it. Purim started to feel more reasonable to me as I read more and learned more about Jewish history. Yes, it was a mere fluke (and in twenty different ways) that it all ended up well. But the point both less-younger-me eventually grasped onto was that, in the end, it did end up well. The Jewish community survived and was able to contemplate an untroubled future. And then I began to wonder what could possibly have happened next. Did the Achashveiroshes have children? Wouldn’t those children have been Jews, the children of a Jewish mother. (And what a Jewish mother at that!) Was the next king of Persia then Jewish? Maybe salvation, less-younger-me eventually concluded, maybe salvation really does always come from somewhere.

So I was in. But not entirely. In 1943, the last Jews in the Krakow ghetto were sent to their deaths at Belzec and Auschwitz in the days leading up to Purim. That fact stayed with me for years after reading Schindler’s List (then still called Schinder’s Ark) back in the 1980s, even though I don’t think Thomas Keneally specifically made that point in the book. (I could be wrong—it was a long time ago.) And the weirdness of Purim for a post-Shoah Jew was always with me. I didn’t give into it often. Or really ever—I was a congregational rabbi and the last thing a congregation wants or needs is a rabbi displaying his own ambivalence about the traditions he is in place specifically to endorse personally and to promote. So I did Purim. As I still do. But the absurdity was always with me, always floating around like a distant cloud overhead, one that I could see but which I could also tell wasn’t likely to rain on my parade.

And that brings me to Purim 2024, the Purim that follows October 7. Something like 134 hostages are still being held in Gaza, including our own Omer Neutra, a graduate of the Schechter School of Long Island. There is no clear end to the fighting in sight. Whether the IDF enters Rafah this week or not, their eventually entry into the city seems a certainty. And where that will lead, who can say? If the strike is surgical, quick, and fully effective, it will lead to one place. But if it turns out to be long, drawn-out, and bloody, and if it ends up costing the lives of hundreds or thousands of civilians, it will be a debacle both for the Gazans and for Israel. Bibi, the elected leader, seems to have lost the confidence of a large percentage of the people who voted him into office. How the American government feels about the whole Gazan incursion seems to depend wholly on whom you ask and at what specific moment of the day. (I’ll write some other times about Senator Schumer’s unprecedented—and truly shocking—speech last week.) But while our leaders dither, we’re all feeling out of sorts, unsure, and ill at ease. And the situation on our American college campuses seems to go from bad to even worse on a weekly basis, as Jewish students face a level of anti-Semitism that would once—and by “once” I mean “last year”—been considered unimaginable.

Welcome to Purim 2024. Should we cancel the whole thing? If the Jewish world somehow observed Purim in 1944, we can surely observe it eighty years later too! But there’s more than mere obstinacy in that thought. And with that I shuck off (finally!) all prior versions of myself to speak as current-me, as who I am today.

We live on the razor’s edge, all of us of the House of Israel. And Purim is our annual homage to that thought. As I wrote last week, the story both condemns and yet also celebrates the existence of a vibrant Jewish diaspora. As it begins, the Jews, a mere century after the Babylonians sent the Jews of Judah and Jerusalem into exile, have settled into every one of the 127 provinces of Achashveirosh’s empire. They appear to be thriving too, possessed of synagogues and businesses, of wealth and a sense of belonging that makes it reasonable for them, all of whom live in the same country as the Land of Israel and could presumably relocate to there if they wished—they all seem to be fine with living abroad and seeking their fortunes in those places. Yes, Haman does present a problem. But some combination of Providence and good fortune neutralize him and lead to the destruction not of his intended victims but of his own gang of would-be murderers. It could have ended up terribly, but it didn’t. It doesn’t always not, of course. (If there had been any survivors of those final deportations from the Krakow ghetto, you could ask them.) But it also does. And in the larger picture of things, it always does: the world has doled out its worst to the Jewish people and yet here we are, still thriving, still doing our best to pass our Jewishness along to the next generation, and still observing Purim and, yes, having great fun at the same time.

Living on a razor’s edge is uncomfortable, obviously. That’s the whole concept, after all! But we really have gotten good at it over all these years. And although the world really is full of the most horrible people who wish us ill, salvation—at least in the global sense—had always come, as Mordechai said it would, from somewhere. And so shall it again come—for the hostages, for the soldiers of the IDF serving in Gaza, for their families and friends across the globe, for us all. That is the message of Purim 2024 and it is one the me that all those previous versions finally grew into—it is the one I can embrace wholeheartedly. Yes, the forecast may occasionally be grim. But salvation really does comes, at least eventually, from somewhere.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ezra and Esther

Being an ancient book, the Bible makes many of its best points using all sorts of literary techniques that are unfamiliar to modern readers. Sometimes these are subtle flourishes that only someone reading truly carefully would ever notice. But other instances are totally overt, fully visible, and noticeable by even someone just casually perusing the text. The willingness of the narrative to depict the same individual as being two different ages at the same time is a good example: to most moderns, passages that do that have a clumsy feel to them and suggest that some ancient editor must have been asleep at the switch and simply failed to see a giant discrepancy that could easily have been fixed. (To see an essay I published years ago about that specific feature of the scriptural text, click here.) But discrepancy is more wisely taken as a literary feature of the text, as a kind of riddle fully intended to teach something to those who take the time to solve it.

Also in that category is the apparent willingness of Scripture to present two versions of the same story that are essentially incompatible with each other. The most famous example of that would be in the very beginning of the biblical text, where Genesis starts off with two wholly irreconcilable accounts of the creation of humankind. Many and clever have been the attempts of countless commentators to “fix” the problem by finding a way to fit the stories together into a single, cogent narrative. But the far more interesting way to approach the problem is to understand this opening riddle as one of many places in the text of Scripture in which the same story is told in two discordant versions not to confuse or to annoy, but to invite the reader to exploit the differences between the two conflicting texts to learn a lesson that Scripture prefers for some reason to teach subtly rather than fully openly.

As Purim approaches, I’ve been thinking how that approach to mismatched texts can be applied not solely to texts within a biblical book, but also to the larger biblical corpus itself. (I have an essay about that too: click here.) In other words, taking the Bible as a book (as opposed to a collection of books) allows the reader to approach the full text of Tanakh as a single literary unit to which the interpretive rules generally brought to bear in explicating passages within specific single books can be fruitfully applied.

In the second of my two essays mentioned above, I applied this principle to a huge difference between the biblical books of Jeremiah and Daniel, one that would be simple to wave away as a mere instance of misspelling on the part of one or both authors. Today, I would like to apply that same principle to the biblical books of Esther and Ezra. And then I would like to apply the lesson that comparison suggests to our present situation as Jewish Americans.

The Book of Ezra, one of Scripture’s most understudied books, begins where Chronicles leaves off: with the surprise announcement that, as one of his first royal edicts, Cyrus, king of Persia, formally ended the exile in Babylon and told the Jews living in modern-day Iraq and Iran that they could return to Israel and re-establish Jewish life in that place. It’s a complex story. The edict of Cyrus itself appears in Scripture in several different versions. The specific relationship between the work of the Chronicler (as the anonymous author of Chronicles is chummily called by scholars) and Ezra and its own sister work, the Book of Nehemiah,is a matter of endless scholarly debate. But, for all that, the storyline itself is clear as day. In the waning days of the Kingdom of Judah (the sole remaining Jewish state in its day, the northern Kingdom of Israel having been dismantled by its Assyrian overlords more than a century earlier), the Babylonian hordes arrived at the gates of Jerusalem. There was a brief window of opportunity during which the coming debacle could have been averted. (The prophet Jeremiah was at the peak of his powers in the months leading up to said debacle and promote surrender as a means of survival.) But the king of Judah wouldn’t hear of it. And what ensued was the razing of Jerusalem’s walls, the slaughter of countless citizens, the destruction of the Temple, and the annihilation of the nation’s hopes for some sort of continued existence as an autonomous state. What ensued is known as the Babylonian Exile. Some Jews—the poorest and least educated ones—were ignored. But the rest of the nation—the royal court, the scholars, the businesspeople, the upper and middle artisan classes—were taken off into exile and forced to attempt to survive while “weeping on the shores of Babylon.”

There is endless debate about the details: how many people went into exile, how many survived, how successful they were or weren’t in retaining their ties to their own Jewish culture while in a hostile environment. But none of that alters the basic the storyline: the Babylonians exiled some or many (but not all) the Jews and then, when they were defeated in turn by Cyrus of Persia, those Jews and their descendants were permitted to go home and it is their story that the Book of Ezra tells. Nor is the moral of the story hard to suss out: Jewish life in exile is possible, but the only real hope for continued Jewish existence lies in return to the land. Yes, Cyrus’s decree specifically permits any who wish to stay behind and support the returnees financially (“with gold, silver, goods, livestock, and valuables”). But the author’s point couldn’t be clearer: exile is barely bearable and only briefly. When the opportunity presents itself to return to Zion, the people who care about their own future get going—because that is where their future lies. From there, life progressed. In the chronology put forward in Ezra, Cyrus is replaced on the throne by Darius, who is followed by—surprise!—King Achashveirosh, known to all from the Esther story. (His “real” name was Xerxes, and he was followed by his son Artaxerxes, who was on the throne in Ezra’s own day.)

Let’s go back to Achashveirosh. I love that he has two names. (I do too, as do most diasporan Jewish types.) And I love that he’s mentioned not only in the book that is so much “about” him, but also in other books: here in Ezra and also once in the Book of Daniel (whose author thought he was Darius’s father, not his grandson. Whatever.) And thus does he serve as the link between Ezra and Esther by appearing in both, albeit briefly in Ezra and at length in Esther.

The storyline of Esther is known to all who have ever been in shul on Purim. But that story contains some riddles generally left unposed, thus also unsolved.

A terrible decree goes forth calling for true genocide, for the total eradication of the Jewish people. The edict is met with astonishment by the people, who are given a full eleven months to prepare for their execution. Eventually, things end up well. But I’m focused on what happens before that happens. The people is in a panic. They appear to inhabit every one of the 127 provinces of Achashveirosh’s empire. The portrait drawn by the Chronicler and by Ezra of a people temporarily banished from its homeland and more than eager finally to abandon exile and return to Israel seems oddly out of sync with the scene depicted in Esther. Cyrus reigned for about twenty years, from 550 BCE to 530. Darius reigned for about forty years after that. And then we have Achashveirosh/Xerxes, who came to the throne in about 465 BCE and who reigned for about forty years. In Cyrus’s day, the Book of Ezra has the Jewish people returning en masse to the Jewish homeland and leaving a few stragglers behind. But, a mere century later, the Book of Esther depicts a Persian empire with Jews living in all 127 of its provinces and apparently well settled in and, until Haman, secure.

And how do the Jews in the Megillah respond to impending genocide? (This is, of course, real genocide they were facing, not the phony kind modern-day anti-Semites see whenever Israel dares defend itself forcefully against its enemies.) They weep. They fast. They daub themselves with ashes, essentially pre-sitting shiva for themselves while they still can. But no one seems to remember that Israel—then called Yehud (the Persian version of Judah)—was one of those 127 provinces. And that there was no specific reason for the Jews, instead of cowering in terror, not to return to their own ancestral homeland and there to defend themselves against their enemies. This course of action—forceful, beyond justifiable, and possible even fully successful—this seems to have occurred to no one.

The Jews seem to prefer their misery. Mordechai forbids Esther to reveal her Jewishness to the king until precisely the right moment. But surely the Jews of Shushan knew that Esther was Jewish—how could they not have? They all seem to know who Mordechai is. And Esther was his ward, an uncle’s daughter whom he had adopted and promised to raise. Surely she too would have been known to all. And yet no one seems to light upon the idea of getting Esther to beg the king for permission to return to Zion and there, in their own homeland, to resist the terror-onslaught planned by wicked Haman.

And so we have two worldviews in conflict: the one set forward in Ezra in which it goes without saying that the future of the Jewish people depends on their ability to flourish in Israel and the one in Esther that seems to think that the best hope for Jews in the diaspora is to hope that salvation from even the most extreme version of violent anti-Semitism (i.e., the kind that promotes genocide as its end goal) is to pray that salvation comes, to quote Mordechai himself, “from somewhere.”

Or do we? Could the point of Esther be to show the folly of charting a future for the Jewish people by hoping for salvation “from somewhere” or anywhere? The Jews of Persia were saved because of Esther’s daring and Mordechai’s cunning. But that their plan works at all is presented as something just short of miraculous. The Jews of Persia are depicted as powerless and foolish…and wholly unable to see that their only real hope rests in returning to Zion and there flourishing out in the open and fully in the light as proud members of the House of Israel. Ezra simply starts off by taking that for granted. Esther depicts a people gone astray a mere century later. Reading each in each other’s light is meant, I think, not to confuse, but to challenge those inclined to suppose that Jews can be safe by relying on others and hoping for the best and, to encourage them, ayin l’tziyyon tzofiah, to see where the ultimate destiny of Israel lies.

0 notes

Text

Seeking Solace in Small Things

I’m feeling the weight of it all these days. I suppose most of you are too. Israel seems to have ended up in a Vietnam-style quagmire in Gaza, one that that feels increasingly insoluble with each passing day. All 136 hostages remain hidden away in Gaza, without it even being known with certainty which or how many are still alive. The weight of world opinion, briefly with Israel in the wake of the October 7 pogrom and its bestial brutality aimed at innocents, has long since turned away; each day seems to bring reports of more world leaders promoting the idea of another lopsided “prisoner exchange” to deal with the situation, but without noting that none of the captives in Gaza is being incarcerated after having been found guilty of a crime whereas all of the Palestinians who would be released in such a deal are precisely that: terrorists sentenced to prison for having committed crimes, including murder. Each day seems to bring another reason to be distressed. The debacle connected with the storming of that convey of aid trucks in Gaza City last week that led to the deaths of 112 Palestinians is a good example: regardless of how many precisely were killed by the stampeding crowd itself, how many were run over by the trucks carrying the aid (and driven by Palestinian drivers), and how many were shot by Israeli soldiers when some in the crowd foolishly attempted to storm IDF positions set in place precisely to watch over the aid distribution, the death of hungry people attempting to procure food for themselves and their families is tragic regardless of how precisely it may have come about.

Paired with the rising tide of anti-Semitic incidents, including ones featuring violence and death threats, directed against Jewish personalities, Jewish students, and individual Jews targeted solely because of their Jewishness, it’s no wonder my mood has been grim in the course of these last few weeks. How could it not have been? In that way (and also in so many others), we’re all in the same boat.

And so I’ve found myself seeking solace in small things, in the kind of thing I would normally look past quickly without dwelling on much or even at all. It doesn’t always work, this technique. But I thought I would offer my readers this week the comfort that can come from contemplating three tiny things, each in its own way a reminder of the unbreakable link that ties the Jewish people to the Land of Israel, thus—in that peculiar Jewish way I’ve written about many times—a symbol of hope in the future rooted wholly in the past. Each is a thing of beauty. And each is a reminder that Israel has faced far worse enemies than Hamas in the past and survived.

The first is, of all things, an earring. And a tiny one at that, albeit a tiny one made of solid gold. And its story, antique though it may be, is heartening, perhaps even a bit encouraging. There was a time when Israel and its neighbor to the north, then called Phoenicia, got along famously. King Hiram of Tyre, for example, was one of King David’s closest allies: when David conquered Jerusalem and made it his capital, Hiram sent carpenters and stonemasons south to help build David’s new palace in the northern part of the city. Nor did the alliance end with David’s death: when Solomon, David’s son, built the Temple in Jerusalem, Hiram sent along cedar wood—a local specialty and still today the tree emblazoned on the Lebanese flag—to be used in the building effort and also workers (and probably thousands of them) to assist in the construction of Solomon’s new royal quarter in the Ophel, the part of the city south of the Temple Mount and north of the City of David area. Were some of those workers women? Or did the workers actually move to Israel and bring their families along with them? Or did Phoenician men wear earrings? Regardless, it’s a thing of true beauty and someone dropped it in the sand about three thousand years ago—or took it off and put it in a jewelry box that has long since disintegrated or put in the pocket of a robe when heading into the bath unaware that it would be part of the world long after the bathhouse itself would turn to dust. The world has change in countless ways since King Solomon’s time. Almost no artifacts from his day have survived. But ten years ago, an Israeli archeologist, the late Dr. Eilat Mazar, found the earring while sifting through what literally must have been tons of dust and mud in the Ophel. For a decade, the earring languished in the collection of things unearthed but not fully gone through. And then, just recently, the earring was discovered.

It's a tiny thing. It’s beautiful. Whoever lost it, assuming it was lost, must have had a fit! But this tiny golden thing survived—I speak here fancifully, but also hopefully—it survived for a reason: to remind us today, as all our spirits are flagging, that there was a time when Lebanon and Israel were close allies, friend, and trading partners. In the earliest days of the Jewish kingdom, Jerusalem was filled with workers building new things. (Some things don’t change.) And one of them, a man or a woman, a wealthy person who owned lots of golden things or someone of more modest means for whom a single pair of gold earrings (assuming the recovered one had an ancient mate) constituted a major percentage of that person’s wealth—someone lost an earring that survived to remind us that both the past (which is gone) and the future (which doesn’t exist) are mere reflections of the present. And that the troubles we experience in that present are not ours alone, but ones shared—magically but truly—with both our ancestors and our descendants. We are not in this alone, despite how we so often feel. And that is what this tiny golden thing from ancient times reminded me of, and in doing so brought me comfort and some level of relief from the ill ease I seem to be unable to shake off.

My second small thing is even tinier than the first. An off-duty IDF officer, one Erez Avrahamov, was hiking in the Lower Galilee a few weeks ago in the Nahal Tabor Nature Reserve, one of Israel’s most beautiful places. And there he stumbled across the coolest thing: a tiny scarab made of carnelian stone and probably about 2,800 years old. Where the thing came from, who can say? Probably it was made in ancient Iraq, either in Babylonia or Assyria. Featuring a beetle on one side and a winged horse on the other, the scarab was probably lost by someone in the 7th or 6th century BCE, when a visitor from the East—or possibly a citizen of Judah who had recently been in what is today called Iraq—inadvertently dropped it when preparing to enter the huge bathing facility that once stood on the spot, perhaps as a prelude to dining in one of the giant buildings than then also existed in that place.

Or perhaps it wasn’t lost at all and is simply all that is left of the person who wore it, perhaps as a pendant (the bezel is long gone, of course) or in a ring? In looking at this truly super-cool looking thing, I find comfort—in remembering that the history of Israel is charted not in centuries but in millennia, and that thousands of years ago, my 40x-great grandfather may well have been on his way home from a business trip to Assyria with a lovely present for my 40x-great grandmother when he stopped off for a much-needed bath before returning home and clumsily dropped the present on the floor of the locker room. Or in the woods. Or on the path itself that led from the east. The living of his day have long since turned to dust. But this beautiful thing, this tiny artifact, remains and has its own lesson to teach: mostly, the things of the world and its peoples are fragile, brittle things that don’t last all that long. But something always remains. All is never lost, or not fully lost. There’s always something left behind to remind future generations to look ahead by looking back. And by remembering.

And my third small thing is, of all things, a box. It’s made of limestone and isn’t itself all that tiny—but I include it today because it was made to hold small things. Found along the great commercial street leading up from the Siloam Pool to the Temple Mount directly through the City of David and the Ophel, the shop in which a shopkeeper displayed his or her wares in this specific box has been gone for millennia. So has the shopkeeper and all of his or her customers. But once that street was a major commercial thoroughfare along which pilgrims and tourists made their slow ascent to the Temple. Stopping off for refreshments or souvenirs to bring home must have been par for the course, just as it is today in the streets leading to the Kotel. And in one of those shops, this box was filled with…with what? Jewels or scarabs? Candies or nuts? “I ❤️ Jerusalem” pins? Who can say? But the thought of Jerusalem in ancient times filled with tourists, pilgrims, visitors, Jewish and non-Jewish people from all over the world, all intent on seeing for themselves the glories of the most glorious of all Jewish cities—that gives me comfort as well. I imagine myself among them too, one among many, a single man strolling along the wide avenue, wondering if Joan would like an Assyrian scarab or a Phoenician gold earring or an ““I ❤️ Jerusalem” pin, an ancient version of modern me feeling fully connected to the Land of Israel and to its eternal capital, to its citizens and to its soldiers, its kings and its priests and its prophets. When I contemplate little things like this, I remember that our present dilemmas and challenges are no different than the ones faced by our forebears or the ones our descendants too will have to face. It’s always something! And, that being the case, you can spend your days submerged beneath the weight of it all. Or you can seek comfort in small things. Will someone thousands of years from now somehow find the earring Joan lost at a wedding we attended ten years ago at the Westbury Jewish Center and find comfort in knowing we were here in this place and survived to bequeath our Jewishness to our descendants? None of us reading (or writing) this will know. But knowing that it could happen—that too brings me solace in troubled times.

0 notes

Text

Heroes

I was troubled, but also very moved, by the death of Alexei Navalny, the personality at the core of the resistance movement in Russia struggling to oppose the dictatorial and oppressive policies of the Putin regime. What exactly happened is not at all clear. At the time of his death, Navalny was imprisoned in a penal colony in Western Siberia in a place called Yamalo-Nenets near the Arctic Circle. According to the warden, he was taking a walk just two weeks ago after telling some guards that he didn’t feel at all well. And then he collapsed. The prison authorities claim to have done all they could to resuscitate him, but were, they said, regretfully unsuccessful, as result of which regretted unsuccess he was dead by mid-afternoon. His body was then held for well over a week and then finally released to his family for burial. And so ended the life of one of the world’s true heroes, a man who not only put his life on the line to stand up for his beliefs, but who personally embodied the struggle for human rights in today’s Russia. Yehi zikhro varukh. May his memory be a blessing for his co-citizens in Russia and for us all.

There’s a lot to say about Navalny, but the detail—one among many—that is particularly resonant with me has to do with his return to Russia in 2021, an act that was as noble as it was death-defying. By 2021, of course, Navalny had a long history of being a thorn—and an especially sharp one at that—in the side of Vladimir Putin. He had led countless demonstrations against the Putin government. He repeatedly accused, certainly correctly, Putin of engineering his own victories whenever he stood for re-election as Russia’s president. And he openly opposed the war against Ukraine.

Navalny tried several times to gain a foothold in the bureaucracy he so mistrusted. He ran for mayor of Moscow in 2013. And then he ran for president of Russia in 2018, a move that was in and of itself daring given that he had previously been found guilty of embezzlement, which detail would normally have disqualified him from running for elected office despite the fact that there appears to be no reason to think that the verdict was just or reasonable. But the real reason Navalny was such a problem for Putin was that he appeared to be unfazed by the forces of government, including the Russian judiciary, that were openly and brazenly arrayed against him. And so the government eventually took matters to a new level.

In 2020, on a flight to Moscow, Navalny took ill and ended up on a ventilator in the Siberian city of Omsk, where his airplane had been obliged to make an emergency landing. It didn’t take doctors long to realize that he had been poisoned. (It later came out that his clothing, including his underwear, had somehow been suffused with the Novichok nerve agent, a poison known to have been used by Russia in the past to murder dissidents abroad.) Eventually, the German government, acting unilaterally, sent an airplane to Omsk to bring Navalny to Germany. Amazingly, this actually worked. And it was in Berlin that doctors at the famous Charité Hospital determined with certainty that Navalny had been the victim of an unsuccessful attempt on his life and that he had definitely been poisoned. Remarkably, his life was saved and he recovered. And then, in January of 2021, he returned to Russia.

Because Navalny had been convicted in a 2014 trial that was almost certainly politically motivated and unjust, he had theoretically been forbidden to leave Russia even for medical treatment. And so was he arrested at the Moscow airport upon his return to Russia and imprisoned to await a judge’s decision about his future. And it was just a month after that, in February of 2021, that a Moscow judge decreed that his suspended sentence, minus time served, would be replaced with an unsuspended one and that Navalny would have to serve two and a half years in a Russian prison. He was sent to one prison, then to another. Eventually, the government determined that it did not want to face a freed Navalny in less than three years and so began new proceedings against him again, this time charging him with fraud and contempt of court. In March of 2022, just two years ago, he was found guilty of all charges and sentenced to nine years in a maximum security prison. And then, because even nine years was apparently not long enough, Navalny was put on trial again last summer and sentenced to an addition nineteen years on extremism charges. And so he ended up in the Arctic Circle prison in which he died two weeks ago at the age of forty-seven.

Navalny’s is a long, complicated story. But the one detail that stands out to me, the single part of the story that is the most resonant with me—and with my lifelong interest in the concept of heroism—has to do with Navalny’s decision in January 2021 to leave safety in Berlin and return to Russia. He had every reason to expect that he would be arrested upon return. He had no reason to suppose that any future trials to which he would be subjected would be just. He surely knew not to expect clemency or mercy from Vladimir Putin, the man behind all the juridical procedures overtly and unabashedly designed to silence him. And yet he chose to return—not specifically, I’m sure, because he wanted to die or because he wanted to participate in yet another crooked trial, but because he saw himself as a moral human being who had been granted the opportunity to inspire his co-citizens to demand justice and freedom for themselves and for their nation.

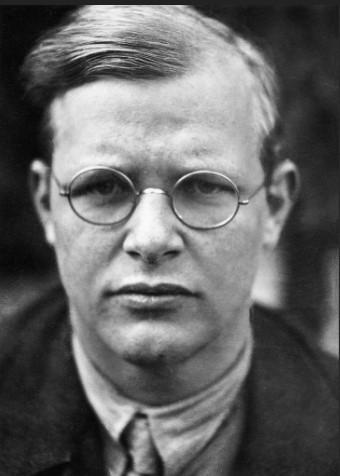

I’ve written in this space, although not too recently, about my boundless admiration for Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the German pastor who was safe and sound in New York when the Second World War broke out, but who made the noble (and eventually fatal) decision to return to Germany and there to try to inspire people to resist Nazism and to turn away from the path of ruinous and fascist barbarism down which the Nazi government was intent on leading the nation. (To revisit my comments about Bonhoeffer from 2011, click here.) Here was, in my eyes, a true hero: a man fully committed to his own ideals who made the conscious decision to leave the safe haven he had already found and to travel to a land that would probably, and which eventually did, kill him. To me, that decision to risk everything to attempt, even quixotically, to do good in the world represents the essence of heroism. It came to naught, of course. He did a lot of good for a lot of people, but, in the end, he paid the big price. On April 8, 1945, just a month before the end of the war, Bonhoeffer was tried on the single charge of treason in a court set up in the Flossenbürg concentration camp. There were no witnesses. No evidence against him was brought forward, nor was a transcript of the proceedings made. He was found guilty, apparently on Hitler’s personal order, and executed the next day in a way that was specifically intended to maximize his personal degradation and agony. (Eric Till’s 2000 movie, Bonhoeffer: Agent of Grace, is a worthy attempt to tell Bonhoeffer’s story even if the director couldn’t quite bring himself to depict the barbarism of Bonhoeffer’s final moments in any detail, let alone explicitly. For a more detailed account of his life, I recommend Eric Metaxas’s 2020 biography, Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Prophet, Martyr, Spy, which I read a few years ago and enjoyed immensely.)

So, two men who lived scores of years apart, who spoke different languages, who came from different countries. One, a political man fully engaged by the political process. The other, a man of God fully in the thrall of his own calling to preach God’s word in the world and to inspire others to seek justice and to act righteously. But both heroes in my mind—both fully safe in a place their tormentors could not reach them and yet both of whom made the decision to return to their separate homelands to seek out in those places the destiny to which each felt called. Would I have left New York in 1939 or Berlin in 2021 to risk my own life to follow the destiny I perceived to be my own? I’d like to think I would have. Who wouldn’t? But we don’t all have it in us to act that boldly, to risk everything to be ourselves fully and in the most noble way possible. To be a man in full—or a woman in full—is never quite as easy in real life as it sounds as though it should be on paper. And that is why I admire those two men, Bonhoeffer in his day and Navalny in ours—and their willingness not merely to talk the talk, but truly—and at their own mortal peril—to walk the walk. May they both rest in peace!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Jewish Wind Phone

All of us for whom prayer is part of daily life have occasionally been challenged to justify our practice—possibly even just to ourselves—by saying clearly whom we think we are actually speaking to when we pray. It’s not that easy to know how to respond. There are numerous traps to avoid when answering. Saying simply that we are talking to God seems inevitably to lead to two derivative questions, both unsettling to address: how exactly we know that and why it is we think all-knowing God needs to be told anything at all. And a third question too, equally disquieting, also surfaces regularly, the one that asks why it is, if prayer is dialogue, that God never seems to talk back in the way we would consider perfectly normal with any other interlocutor.

The problem, however, lies not in our answers but in the questions themselves: all are rooted in a simplistic understanding of what language is and the role it plays in our human lives. Yes, language is communication: you ask the nice lady in the store which aisle the paper towels are in and she tells you. But language is also self-expression, a means of ordering the world, of grappling with the unfathomable by addressing it, by naming it, by interpreting it. And it is that latter definition of language that we bring to prayer: the world feels overwhelming in the wake of disaster and, instead of withdrawing into our shells like terrified turtles, we face the darkness by naming it, by labeling its parts, by addressing it from the depths of our consciousnesses. We thus allow language to serve as a kind of bridge that connects our inmost selves to the terror just ahead…and, instead of trembling in our boots or shutting our eyes, we speak. And thus do we subdue the raging world with language, with words, and, yes, with prayer.

Almost entirely forgotten—at least by Americans—is the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami that hit Japan on March 11, 2011, a nightmarish disaster in the course of which 15,894 died almost instantly, most from drowning. More than 2,500 simply disappeared and were never seen again.

In the wake of that disaster, I remember reading about an older man named Itaru Sasaki, who lives in a place called Ootsuchi where over eight hundred people were washed out to sea in less than a single minute. His town was devastated by the tsunami, but he himself was in mourning for a cousin, someone he truly loved, when the disaster struck. And so, feeling bereft and totally alone, he came up with a very strange way to deal with his grief: he purchased on old phone booth and set it up in his garden. Then he purchased an ancient rotary phone, a black one, and put it on a table in the booth. There was no dial tone because the telephone wasn’t attached to anything. But on that phone, Mr. Sasaki would talk to his cousin and tell him about his life now that he was carrying on alone and without someone he truly loved. He called it the kaze no denwa, the “wind telephone.”

And then, the amazing part. Word spread about this thing, this crazy, unconnected, telephone in a phone booth in a garden by the sea. People started coming. In droves. From all over Japan. NPR sent a reporter to cover the story and he got permission to record some of what people were saying into the phone.

“Why only me, dad? I’m the only one left alive. People don’t realize what it’s like,” a teenage boy said to his missing father.

“Everyone’s good here. We are all trying hard,” an elderly lady told her long-time spouse, a man who disappeared when the sea overwhelmed his town.