Text

Should this Celt be blue?

An irish-dress-history game.

I've been researching the actual historical evidence behind the idea that ancient Insular Celts painted or tattooed themselves blue, and I thought it would be fun to make a game out of it. Below are various depictions of this idea along with the culture and date they are supposed to be depicting. The game is to guess whether each use of body paint or tattoos is supported by actual historical evidence. Answers are in the image descriptions.

(Note: This game is not intended to mock or criticize the artists and costume designers of any of these works. Good information on this topic is hard to find, and movie creators and artists frequently have goals other than historical accuracy. I am mocking Mel Gibson though, because f*** that guy.)

1 A 'Woad' (ie Pict) from 5th c. Britain. 2. Tattooed Irish warrior in 1170

3. A Medieval Scottish lord 4. Iceni Queen Boudica c. 60 CE

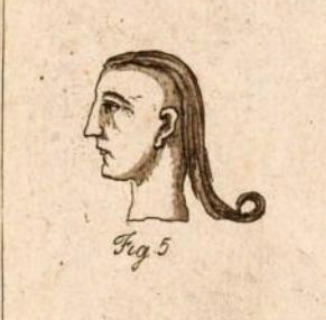

5. Ancient? Ireland 6. Britons during the time of Julius Cesar

7. Picts in 149 CE 8. Scots in 1297

Bibliography:

Hoecherl, M. (2016). Controlling Colours: Function and Meaning of Colour in the British Iron Age. Archaeopress Publishing LTD, Oxford. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Controlling_Colours/WRteEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

MacQuarrie, Charles. (1997). Insular Celtic tattooing: History, myth and metaphor. Etudes Celtiques, 33, 159-189. https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.1997.2117

#iron age#roman era#early medieval#ancient celts#celtic#pict#tattoos#body painting#medieval#insular celts#gaelic irish#Hoecherl#brittonic celts#britons#gaels#scots

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I would go to church if this was the communion

#irish history#reblog#18th century#1790s#ulster#presbyterian#why was this not my communion experience#is this why my church served grape juice instead of wine#rumbustious popular culture

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hate to break it to you, but it your definition of 'UK' includes the Republic of Ireland, the game ended in 1921.

I’m obsessed with the fact the British right wing put Sinn Féin as a ethnicity

#Ireland#Sinn Féin#uk politics#reblog#irish history#if you didn't want a bunch of british citizens with non-british ancestry maybe you shouldn't have colonized a bunch of non-british countrie

377 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’m wondering if you have any examples of Irish clothing from the early 1600s (around 1610-1615)? I haven’t been able to find much from this era so I’d appreciate any sources or museum collections that you could recommend.

Starting this out with the caveat that if you're looking for the same level of detail and precision that we have for English dress history in this period, you are going to be disappointed. The types of English primary sources we have for this period (well-dated detailed paintings, well-preserved rich-people clothing, wills, printed books, etc) just don't exist for Ireland. There also seems to be much less research interest in 16th-17th c. Irish dress history, so there isn't nearly as much for secondary sources (books, articles etc.).

You don't mention if you are interested in a specific region in Ireland. Ireland in the early 17th c. was a pretty heterogeneous place. People in Dublin and Waterford wore English-influenced styles. According to British-appointed solicitor-general Sir John Davies, by 1606 a few of the wealthier people in Connacht had started wearing English dress, but many others were still wearing Irish clothing. Ulster was a mix of Irish who were wearing Irish dress and incoming English and lowland Scots settlers.

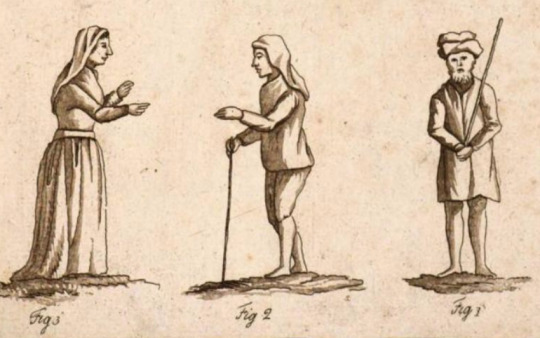

All of the extant Irish clothing I know of from the early 17th c. comes from either bogs or archaeological excavations. It looks like you've already seen my post on extant garments at the NMI. The NMI also has a couple of felt hats that might be early 17th c. This one is from Knockfola, Co. Donegal. It originally had a decorative cord or band where the pale line is:

There are also another cóta mór and brat, found on a bog body from Leigh, Co. Tipperary, which I don't think the NMI has on display. I did not bother to include them in my post, because they are so similar to the ones from Killery, Co. Sligo, but the fact that these have been found in multiple places suggests that they were common, widely-used garments.

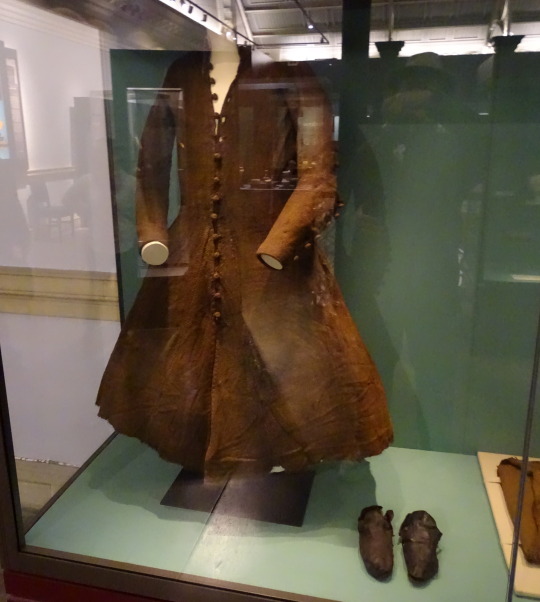

The other major garment-find from this period is the Dungiven outfit which is in the Ulster Museum. a short video The bright blue thread was added by a modern conservator; it's not original. (Side note: The identification of this outfit has gotten unfortunately politicized. Tartan trews were worn by both the Irish and the Scots during the 17th century (McClintock 1943, Dunlevy 1989). The presence of tartan should not be used to draw conclusions about the ethnicity of the wearer.) The primary publication for this outfit:

Henshall, Audrey, Seaby, Wilfred A., Lucas, A. T., Smith, A. G., and Connor, A. (1961). The Dungiven Costume. Ulster Journal of Archaeology, 24/25, 119-142. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20627382

The one other reasonably-well preserved outfit that has published on is from a child burial from Emlagh, Co. Kerry, now at University College Cork. Shee and O'Kelly give it a late 17th c date, but they largely base this date on the presence of a rather generic-looking comb. IMO the outfit could easily be early 17th c.

The Emlagh gown, photographed on a living 8-year-old child who was wearing a sweater and skirt underneath. (The 1960s was a different time.)

The bodice has a wrap-front closure with a back and button-up sleeves similar in cut to the Killery cóta mór. The skirt is a pleated rectangle with the pleats sewn in vertically, somewhat like the Shinrone gown. Publication:

Shee, E. and O'Kelly, M. (1966). A Clothed Burial from Emlagh, near Dingle. Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society, 71(213), 81-91.

There are also, frustratingly, a bunch of fragmentary clothing finds at the NMI which might be 17th c, but no one seems to care enough to do publications on them, and NMI Archaeology still does not have their collection on-line, so they are useless to us.

The typical Irish shoe for this period is known as a brogue (also called a Lucas type 5 by archaeologists). broguesandshoes.com has photos, a pattern, and construction information.

Unfortunately, the illustrations from Speed's map are the only images I know of from this specific period.

If you want details on what materials were used, I recommend Susan Flavin's dissertation. It's about the 16th c. economy, but things didn't change that much between 1599 and 1601. free download here

If you don't mind wading through early modern English and a bit of period-typical prejudice, I recommend reading A Discourse of Ireland, by Luke Gernon written in 1620. His description of Irish clothing starts halfway down p. 356.

Finally, if you can find them, Dress in Ireland by Mairead Dunlevy (1st ed. 1989) and Old Irish and Highland Dress by H. F. McClintock (1st ed. 1943, 2nd ed. 1950) are the best books I know of for this period.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Patterning a 16th c. Irish léine sleeve

Mid-16th c. images of the léine from "Drawn after the Quick" and Codice de Trajes

The léine of 16th century Ireland had huge, iconic sleeves. Sadly, we have neither surviving examples of this garment, nor detailed period documentation, so we don't know how these sleeves were made. I have seen a couple different sewing patterns purposed, but none of these match the voluminous, gathered sleeves shown in the Codice de Trajes and the costume album of Christoph von Sternsee. This is my attempt to create a sleeve pattern that better matches the surviving evidence.

The cut of léine sleeves probably varied across 16th c. Ireland, potentially impacted by factors like a person's wealth or where in Ireland they lived. It almost certainly changed over time as more of Ireland fell to English colonial conquest. The wearing of the large-sleeved léine was banned by King Henry VIII (McClintock 1943). Lucas de Heere’s circa 1575 illustrations show women with much smaller sleeves than earlier images. However, at least during the early part of the century, sleeves did not vary by gender. According to Laurent Vital, the only difference between a man's léine and a woman's léine was that the woman's had gores in the bottom it make it fuller (Vital 1518).

My goal with this project is to create a léine sleeve pattern for an early to mid-16th c. Irish person living outside of the Pale. Since none of the period images or texts are very detailed, I am combining information from several sources.

Englishman Edmund Campion who visited Ireland in 1569 gave the following derisive description of the léine: “Linnen shirts the rich doe weare for wantonnes and bravery, with wide hanging sleeves playted, thirtie yards are little enough for one of them” (Campion 1571).

Campion’s claim that the sleeves were pleated initially struck me as strange. English and continental European shirts from this period frequently had gathered sleeves (Mikhaila and Malcolm-Davies 2006, Arnold, Tiramani and Levey 2008), but pleating isn’t the same thing as gathering. However, other period writers made similar claims. Writing in 1596, Edmund Spenser mentioned "thicke foulded lynnen shirtes” as a garment worn by the Irish (Spencer 1633).

Similarly, Fynes Moryson described the léine as being made of “thirty or forty ells [of linen] in a shirt all gathered and wrinkled,” elsewhere he described it as “folded in wrinckles” (Moryson 1617).

In The Image of Irelande, John Derricke gave the following description of the léine:

Their shirtes be verie straunge,/ not reachyng paste the thie:/ With pleates on pleates thei pleated are,/ as thicke as pleates maie lye./ Whose sleves hang trailing doune/ almoste unto the Shoe (Derricke 1581)

Assuming that Derricke’s description is not just poetic license, I know of one 16th century construction method that matches the description “pleats on pleats [. . .] as thick as pleats may lie,” and that is cartridge pleating. Cartridge pleating is a technique that is more commonly used on thick fabrics like woolens, because a lot of fabric bulk is needed to keep the pleats standing properly, but extant 16th and early 17th c. neck ruffs use cartridge pleating to join massive lengths of fine linen to a neck band (Arnold, Tiramani and Levey 2008).

Cartridge pleating on a thick woolen fabric

A person unfamiliar with sewing methods and terms might well describe cartridge pleating as looking like folds, gathers, or wrinkles.

The léine sleeve patterns commonly used in modern reconstructions are completely flat, like a Japanese kimono sleeve with rounded corners. (There’s also a version which has a drawstring or gathering running along the top of the sleeve. This is a 20th c. Ren Fair invention which has no historical basis.)

The end-on views of the sleeve openings in the recently-discovered images from Codice de Trajes and the costume album of Christoph von Sternsee clearly show that this is not correct. The rounded shape they show for the sleeve end can only be achieved through gathering.

Archer from the von Sternsee costume album and the O’Brien messenger from The Image of Irelande

The best illustration of a léine in The Image of Irelande, the messenger on plate 7, also provides evidence for a gathered sleeve. The way the fabric drapes in the middle of the sleeve suggests that the sleeve is gathered at both ends. Furthermore, the way the mass of a léine sleeve centers under the wearer’s arm when the wearer holds their arm out straight, like the O’Brien messenger, but hangs down like a trumpet when the wearer lowers their arm, like on von Sternsee’s archer also suggests that the sleeve is a symmetrical shape that is gathered at both ends and not a trumpet shape that is only gathered at the wrist end.

With these elements in mind, I went looking for a pattern which would create the correct shape. I used Jean Hunnisett's 15th c. bagpipe sleeve pattern from Period Costume for Stage and Screen and the sleeve pattern from this 1630s English waistcoat (published in Seventeenth-Century Women’s Dress Patterns) as a starting point.

1630s waistcoat sleeve pattern

I replaced the curved sleeve heads in these patterns with the straight sleeve end and square underarm gusset typical of mid-16th-18th c. shirts, since the léine, like the shirt, is an unfitted linen garment, and because the straight edge is much easier to gather all the way around. I don't have any actual evidence for square gussets in 16th c. Ireland, but this pattern definitely needs an ungathered piece at the underarm. Anyone who is bothered by the lack of evidence can use a triangular gusset like the one on the 15th c. Moy gown instead.

After that, I experimented with mock-ups until I figured out how to get the correct proportions. I don't have any training in patterning or draping, so this took several tries. I used my 1/3 scale ball-jointed doll (24 inches tall) as model, because he required a lot less fabric and sewing. Since this was just a mock-up, I used random linen remnants from my stash, and I didn't bother to finish most of the edges.

Here is the final sleeve with the seams sewn together, but before doing the gathering:

This sleeve, on his right arm, is based on the gathered-wrist cuff version of the léine from Codice de Trajes, the von Sternsee album, and The Image of Irelande.

This sleeve ended up with me having to gather 31 inches of fabric into a 5-inch armscye. So yeah, cartridge pleating became necessary, because there is no way to make that kind of reduction work with regular gathering. I also had to do some smocking to get the giant mass of fabric better controlled before I could attach it to the body of the léine.

While this pattern might seem absurd, (it does call for a sleeve end wider than the wear is tall to be pleated into the armscye,) a close examination of John Michael Wright's 1680 portrait of Sir Neil O'Neill shows remarkably similar sleeves.

While this painting is from a century later than my target time period and the clothing clearly shows changes like the addition of English-style shirt sleeve ruffles, the shirt still has elements which I have seen no where else in late 17th c. fashion that are probably derived from earlier Irish dress.

The doublet worn over top prevents it from hanging down properly, but this shirt sleeve has the same bagpipe shape as the 16th c. léine. I have highlighted it in magenta to make this easier to see. The fine, regular folds near the top of the sleeve (highlighted in yellow) are probably the result of smocking or cartridge pleating, indicating that this sleeve, like my purposed pattern, has a large amount of fabric gathered or pleated to the armscye. The wrist end of the sleeve has 3 rows of smocking stitches sewn with silk thread, which shows that the sleeve cuff has a huge amount of fabric gathered into it.

Historically, silk was the thread of choice for smocking, because it is smoother and has greater tensile strength than wool, linen, or cotton. Several 16th c. sources note that the Irish used silk thread when making their léinte (Gresh 2021). Laurent Vital described Irish women as wearing, "chemises with wide sleeves, worked around the collar and in the seams with silk needlework of different colours" (1518). The presence of smocking on O'Neill's shirt combined with my experience trying to recreate this sleeve makes me think that at least some of that 16th c. silk needlework was smocking.

For the left sleeve of my mock-up, I tried to recreate the flatter sleeves from "Drawn After the Quicke". These sleeves do not have a gathered wristband.

This sleeve used basically the same pattern, but the lack of gathering at the wrist opening meant that the whole sleeve was slightly smaller, so I only had to pleat 26 in of fabric into the armscye instead of 31 in. This was just enough of a difference that I could set the sleeve without smocking it first, unlike the right sleeve. I guess this is the more budget-friendly option for your less wealthy kern.

I also made the curve at the bottom of the sleeve wider to give this one a more square shape.

Some of my failed experiments:

I would like to thank my friend Nikki for loaning me her smocking machine. This project would have been a much bigger pain if I had to do all those gathering stitches by hand.

Since this post has gotten rather long, I am putting the actual drafting instruction for this sleeve pattern in a separate post.

If anyone would like to support my work financially, I now have a ko-fi page.

Bibliography:

Arnold, Janet, Tiramani, J., & Levey, S. (2008). Patterns of Fashion 4. Macmillan, London.

Campion, Edmund. (1571). A Historie of Ireland, Written in the Yeare 1571. Dublin. https://archive.org/details/historieofirelan00campuoft/historieofirelan00campuoft/page/n5/mode/2up

Derricke, John. (1581). The Image of Irelande, with the discoverie of a Woodkarne. John Daie, London. https://archive.org/details/imageofirelandew00derr/page/n29/mode/2up?view=theater

Hunnisett, Jean. (1996). Period Costume for Stage & Screen: Patterns for Women's Dress, Medieval-1500. Players Press, Inc, Studio City.

Gresh, Robert. (2021). The Saffron Shirt, Part 1: Saffron and Silk, Urine and Grease. Wilde Irish. https://www.wildeirishe.com/post/the-saffron-shirt-part-1-saffron-and-silk-urine-and-grease

McClintock, H. F. (1943). Old Irish and Highland Dress. Dundalgan Press, Dundalk.

McGann, K. (2008). The Invention of Drawstrings and Pleated Sleeves. Reconstructing History. https://reconstructinghistory.com/blogs/irish/the-invention-of-drawstrings-and-pleated-sleeves-1

Mikhaila, Ninya, & Malcolm-Davies, Jane (2006). The Tudor Tailor. Quite Specific Media Group, Ltd, London.

Moryson, Fynes. (1617). An Itinerary Containing His Ten Yeeres Travell through the Twelve Dominions of Germany, Bohmerland, Sweitzerland, Netherland, Denmarke, Poland, Italy, Turky, France, England, Scotland & Ireland. volume 4. https://ia801307.us.archive.org/16/items/fynesmorysons04moryuoft/fynesmorysons04moryuoft.pdf

North, Susan and Jenny Tiramani, eds. (2011). Seventeenth-Century Women’s Dress Patterns, vol.1, V&A Publishing, London.

Spencer, Edmund. (1633). A View of the present State of Ireland. https://celt.ucc.ie/published/E500000-001/index.html

Vital, Laurent (1518). Archduke Ferdinand's visit to Kinsale in Ireland, an extract from Le Premier Voyage de Charles-Quint en Espagne, de 1517 à 1518. translated by Dorothy Convery. https://irish-dress-history.tumblr.com/post/721163132699131904/laurent-vitals-1518-description-of-ireland

#16th century#irish dress#dress history#leine#art#gaelic ireland#irish history#historical men's fashion#historical dress#historical women's fashion#sewing

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sometimes when you clean your wip folder you find something you made years ago in a way to deal with and at the same time educate others on something very dear to you that's been stolen by people who see stealing it as "doing you a service"

Made this last year during Seachtain na Gaeilge

Anyway. Seeing this again made me think maybe it was alright, actually

Ní dhéanfaidh mé dearmad choíche. Ná bás an tseanteanga go deo

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

1 year, 106 followers! Thank You!

When I started this tumblr a year ago, I only intended for it to be a dumping ground for my Irish dress history primary sources. I wasn't even thinking about the fact that other tumblr users might see it. When people reblogged my early, bare-bones posts and started following me, I realized that there were other people on the platform who cared about Irish dress history, and I started putting more effort into my posts.

I want to thank all of you who have followed, and reblogged, and liked, and messaged. (Especially the people who have sent asks and messages.) Not only was it gratifying to learn that there are other people who share my niche interest, but writing for other people has taught me more about Irish dress history. Describing the clothing depicted in period works of art for tumblr posts forced me to make sure I really understood what those images showed. Justifying my interpretations of those images for my posts forced me do additional research and learn more historical background. So, thank you.

In the next year, I'm planning to do some posts on reconstructing 16th c. clothing, in addition to hopefully getting around to research topics like 'Wilde is not a Social Class' part 2 and the ancient Celts blue face paint thing. (Although both of these topics ended up being waaaay bigger research subjects than I originally anticipated.)

In case you missed it, please check out my post on gilt leather shoes in 16th c. Ireland. IMO it's a neat subject, but for some reason, it has gotten less engagement than my other research posts.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Updated Intro post:

My name is Deidre (she/her). I’m an American historical costumer whose ancestry is a mix of Irish Gaelic, Scotch-Irish (aka Ulster Scots), English, Scottish, and a few other things. I have a bachelor’s degree in Anthropology and a few graduate credits in Archaeology, none of which is particularly related to Irish dress history, but it did teach me something about doing research.

I have never been to Ireland, and I do not speak Irish. (Sadly, I don’t have the money to go.) American schools are worse than useless when it comes to teaching Irish history. I am trying to teach myself the necessary vocabulary and history to understand Irish dress history; I apologize in advance if I screw up.

Racists are not welcome here.

Ko-fi page

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Hi my name is Sétanta mac Súaltaim, the Hound of Culann, and I have curly three-coloured hair with red and gold in it that stands up in rigid spikes and brilliant bright eyes with seven pupils and a lot of people tell me I look like Lug mac Ethlenn (AN: if u don’t know who he is get da hell out of here!). I’m related to literally everyone in Ulster which is great because they’re all major fucking hotties. I’m named after a dog but my teeth are straight and white. I have pale white skin. I’m also a warrior, and I fight on behalf of the Ulaid (I’m seventeen). I’m a hero (in case you couldn’t tell) and I wear mostly armour. For example today I was wearing a silk tunic with a white gold border and a hero’s battle-girdle of hard leather, twenty-seven waxed shirts, and a magic cloak from Tír Tairngire. I was wearing red lipstick, white foundation, black eyeliner and red eye shadow. I was walking past Medb’s camp. It was snowing and raining so there was no sun, which I was very happy about. A lot of the Connachta stared at me. I put up my middle finger at them.”

— Cú Chulainn

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

#reblog#18th century#1790s#society of united irishmen#i need to be able to vote for multiple of these#so i can vote for linen green items and presbyterian fundamentalism#no king but jesus#(not actually a presbyterian fundamentalist but some of my probably ancestors were)

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sorry for derailing this post, but I need to know what footnote 41 is.

There are a bunch of late 16th-early 17th c. English sources which claim that the Irish ate shamrocks, and I have been trying to figure out the origin of this nonsense. Edmund Spenser (probably the most trustworthy member of this pack of bigot garbage sources) implies that "shamrockes" were something that the Irish resorted to because they were starving rather than a normal food item. Some historians have suggested that the English were conflating seamróg with seamsóg (wood sorrel), but I'm not convinced. Charlock makes more sense, especially if people in Munster were using it as a famine food 150 years later.

I don't have words to explain how angry the repeating famines in Ireland under British colonialism makes me.

Like the worst thing about the famine of 1740-1741 for ME is not even the fact that it happened it's the fact that it all but happened again

#irish history#reblog#famine#i need someone to resurrect queen elizabeth 1 so she can be tried for war crimes

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

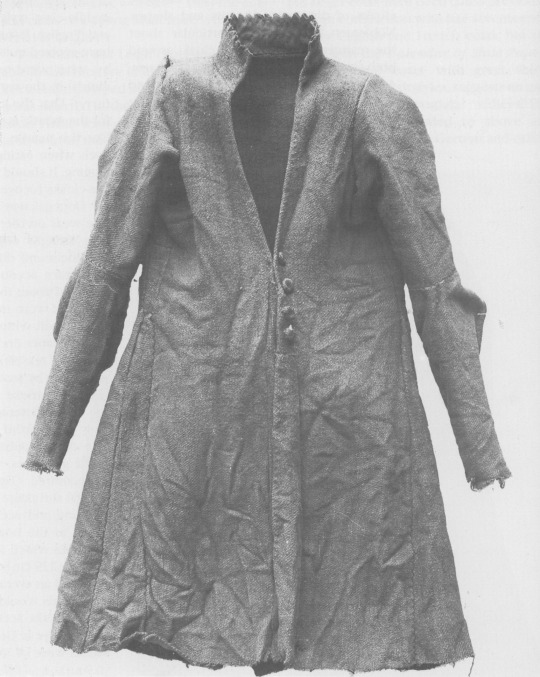

Photos of 16th-17th century Irish clothing

Extant garments in the National Museum of Ireland

Notes: The garments in this post are all bog finds which means their current color may not be their original color. Although some of these items were found with human remains, no photos of human remains are included in this post.

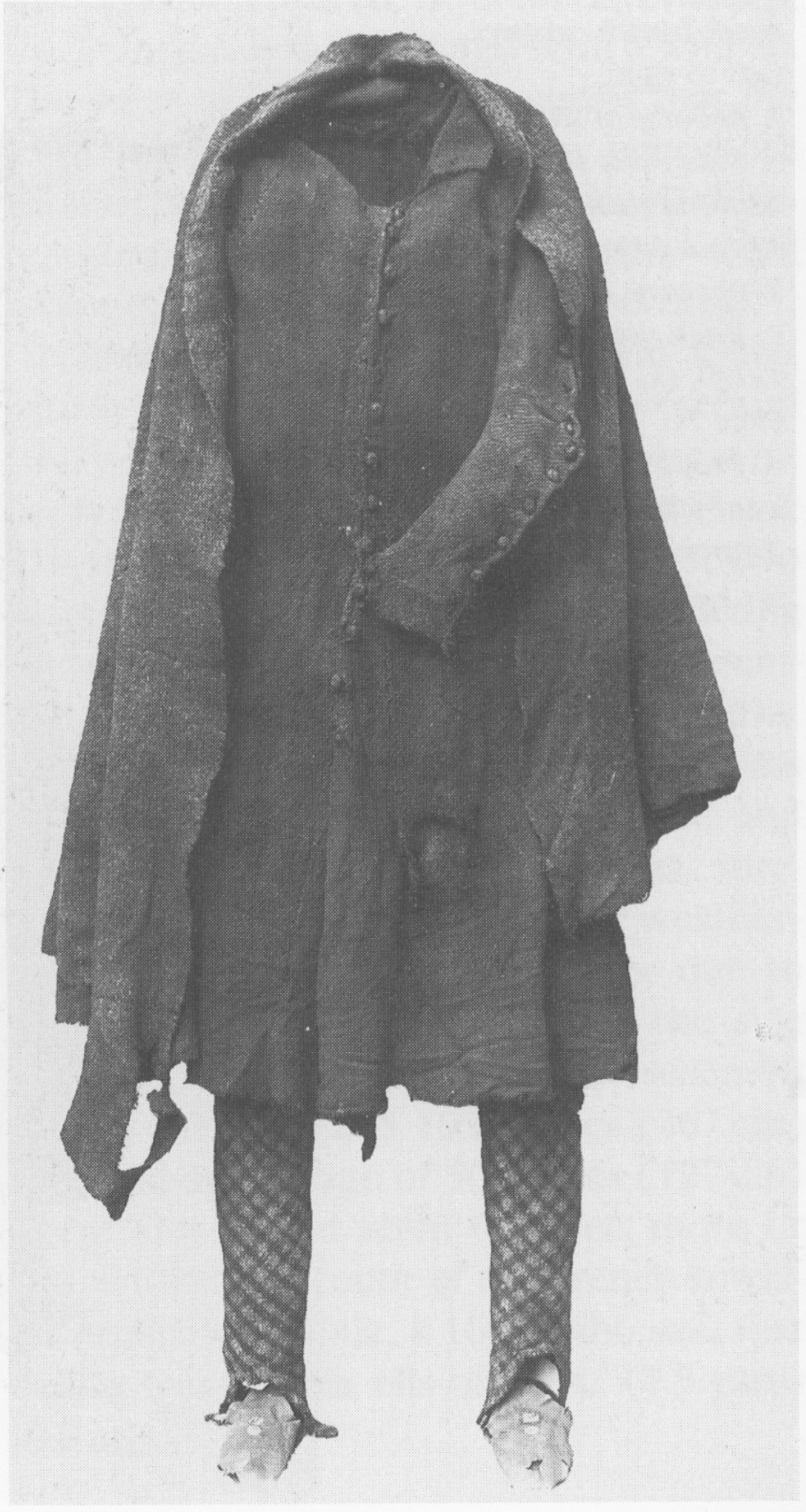

Killery Cóta Mór (great coat) and brogues:

photos by hayling billy used under non-commercial, share alike license

The Killery outfit comes from an adult male bog body found in Killerry parish, Co. Sligo in 1824. It includes a cóta mór, triús, a brat, and shoes which are on display in the museum, and a sheepskin biorraid (conical hat) which fell apart shortly after it was found (Briggs and Turner 1986).

Killery triús (trews):

photo by hayling billy

Killery outfit with and without brat:

The outfit is generally dated to the 17th c. (Dunlevy 1989). It matches Luke Gernon's 1620 description of Irish men's winter apparel:

"in winter he weares a frise cote. The trowse is along stocke of frise, close to his thighes, and drawne on almost to his waste, but very scant, and the pryde of it is, to weare it so in suspence, that the beholder may still suspecte it to be falling from his arse. It is cutt with a pouche before, which is drawne together with a string."

Additional photos of the outfit: cóta front, hem, buttons, and brat.

Shinrone gown:

photo by hayling billy

The Shinrone gown was found in a bog in 1843 in Co. Tipperary near Shinrone, Co. Offaly. Unlike the Killery outfit, there were no human remains or other items found with it (Briggs and Turner 1986). The ends of the sleeves and possibly also the bottom of the skirt are missing. The sleeves would have had wrist cuffs or ties that allowed them to be fastened around the wearer's wrists. It probably also had loops or rings along the U-shaped center-front opening for lacing. It is typically dated late 16th-early 17th c, based on its similarity to a circa 1575 illustration by Lucas DeHeere and to the dresses described by Luke Gernon in 1620 (Dunlevy 1989, McGann 2000). It could be older however, because Laurent Vital described dresses with this type of sleeve in 1518.

Copyrighted, better quality photos: left front, right front, back Additional details: side-front, front waistline

Tipperary Cóta Mór:

photos from Dunlevy 1989 and hayling billy

Another Cóta Mór. This one is from Co. Tipperary, exact find spot and date unknown. Like the Shinrone gown, it was not found with human remains or other items (Ó Floinn 1995). It is probably also from the 17th century (Dunlevy 1989).

Additional photos: front, side, front buttons, front detail, side

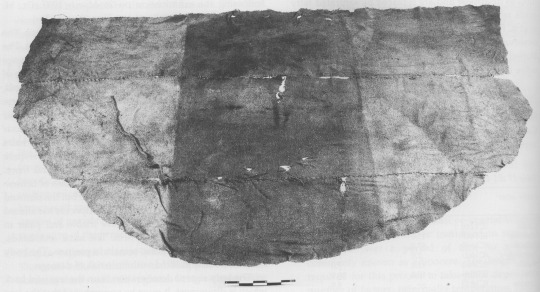

Brat and hats:

photo by hayling billy

I haven't been able to find any clear photos of the label on this display, but based on the excellent condition and the presence of the leather tie, I think this is the Meenybradden woman's brat.

Closeup of the tie:

The Meenybradden woman is a bog body found in Meenybradden bog, Co. Donegal in 1978. The brat was wrapped around her as a shroud and secured with the leather tie (Delaney and Ó Floinn 1995). No other garments or artifacts were found with her, although she may have been wearing a linen garment such as a léine when she was buried. Linen tends to not survive in bogs. The Meenybradden woman has a calibrated radiocarbon date of AD 1130-1310, but some archaeologist have suggested humic contamination from the peat may be throwing off the dating. Her brat is identical in cut to others from the 16th-17th centuries (Delaney and Ó Floinn 1995).

Meenybradden brat laid flat. (photo from Delaney and Ó Floinn 1995)

Wool hats:

Hats from Boolabaun, Co. Tipperary made of wool felt which has been cut and sewn to form the shape. They have togs of unspun wool worked into them giving them the appearance of faux fur. Dunlevy suggests a 15th-16th c date for them (Dunlevy 1989, McClintock 1943).

Wool cloak:

photo by hayling billy

The museum label says it's from Glenmalin bog, Malinmore, Co. Donegal, but I think this may be a mistake. According to Ó Floinn (1995), the artifact with accession number 1946:416 from Malinmore, Co. Donegal is a bale of linen. Ó Floinn's table also gives accession number 1946:416* for a group of clothing from Owenduff, Co. Mayo which includes a gown, a jacket, and a cloak. If the cloak in the photo is actually the one from Owenduff, it is probably from the 17th c (Dunlevy 1989). Alternatively, someone might have misidentified a wool cloak as a bale of linen. The museum label dates this as late Medieval to post-Medieval.

*Either Ó Floinn made a typo or this is a mistake in the museum records. Museums are not supposed to give the same accession number to 2 different artifacts. In the NMI's defense, 1946 was probably a messy year for everyone.

Bibliography:

Briggs, C. S. and Turner, R. C. (1986). Appendix: a gazetteer of bog burials from Britain and Ireland. In I. Stead, J. B. Bourke and D. Brothwell (eds) Lindow Man: the Body in the Bog (p. 181–95). British Museum Publications Ltd.

Delaney, M. and Ó Floinn, R. (1995). A Bog Body from Meenybradden Bog, County Donegal, Ireland. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 123–32). British Museum Press.

Dunlevy, Mairead (1989). Dress in Ireland. B. T. Batsford LTD, London.

Gernon, Luke (1620). A Discourse of Ireland. https://celt.ucc.ie/published/E620001/

McClintock, H. F. (1943). Old Irish and Highland Dress. Dundalgan Press, Dundalk.

McGann, K. (2000). What the Irish Wore/The Shinrone Gown — An Irish Dress from the Elizabethan Age. Reconstructing History. http://web.archive.org/web/20080217032749/http:/www.reconstructinghistory.com/irish/shinrone.html

O’Floinn, R. (1995). Recent research into Irish bog bodies. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 137–45). British Museum Press.

Vital, Laurent (1518). Archduke Ferdinand's visit to Kinsale in Ireland, an extract from Le Premier Voyage de Charles-Quint en Espagne, de 1517 à 1518. translated by Dorothy Convery and edited by me. https://irish-dress-history.tumblr.com/post/721163132699131904/laurent-vitals-1518-description-of-ireland

#16th century#17th century#irish dress#dress history#gaelic ireland#historical men's fashion#historical women's fashion#bog finds#irish history#historical dress#brog#bratanna#irish mantle#headwear#triús#cóta mór

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

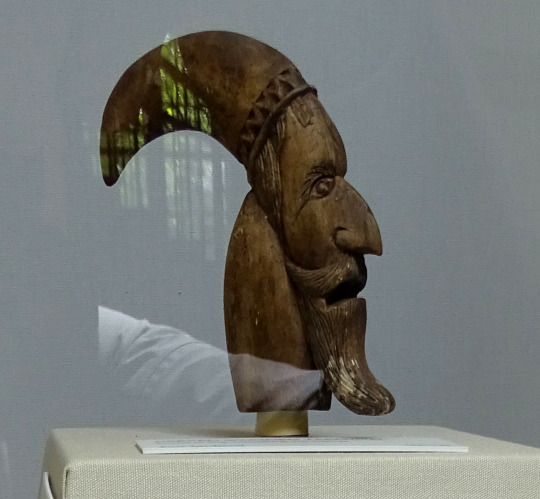

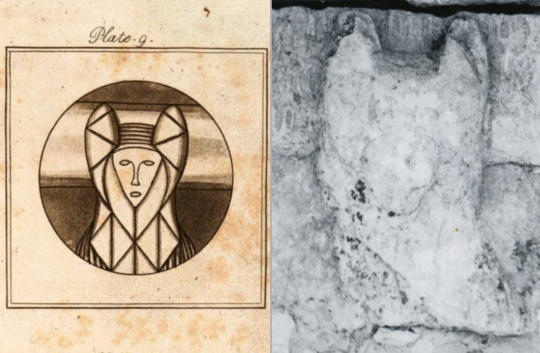

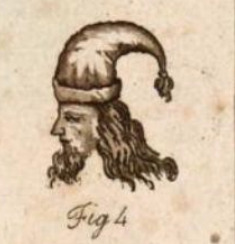

It appears I own J. C. Walker an apology. I finally found his Irish Santa Hat. It's in the National Museum of Ireland.

photo by flickr user hayling billy, used under NonCommercial-ShareAlike license

This isn't actually the same sculpture. The NMI carving came from a bog in County Galway while Walker's drawing is from County Kildare, but it's the same kind of hat, albeit without the tuft on the end. As Walker correctly identifies, this is a barread or biorraid. NMI dates the carving post-medieval.

Identifying J.C. Walker's Illustrations

An Historical Essay on the Dress of the Ancient and Modern Irish by Joseph Cooper Walker published in 1788 was the first major work published on Irish dress history. Due to a combination of the limited information known at the time, and his erroneous assumption that Irish dress didn't change for the entirety of the Middle ages, Walker got a lot of things wrong, so his writing isn't cited much anymore. Some of his illustrations, however, are still used.

Because Walker lived before the invention of photography, he used drawings of historical Irish art created by colleagues and family to illustrate his book. I decided to track down the original works of art to see how Walker's drawings compared. I am resorting these into roughly chronological order, because Walker's lack of regard for chronology makes my head hurt.

The High Crosses, 9-10th centuries:

Ireland's high crosses have unfortunately lost a lot of their detail due to erosion, making these hard to identify. Sadly, the breeches with a fitted knee-band and the skirt gathered to a waistband look more Late Medieval or Early Modern than they do Early Medieval, so I don't think these are reliable depictions of the lost detail.

Plate 1: Figure 1 (right) is supposed to be from the Clonmacnoise Cross of Scripture. At a guess, it's based off the guard on the right arresting Jesus:

Figures 2 and 3 are based off a high cross fragment at Old Kilcullen, County Kildare. Unfortunately, I don't think the original carving survived. I initially blamed its loss on the United Irishmen, but this drawing from 1889 convinced me that acid rain was the real culprit.

Plate 5 Figure 1 is supposed to be a king from Muiredach's cross. The closest image I could find on the actual cross is Cain killing Able:

Ironically, Cain and Able have more embellishment on their clothes than the "king" based off of them.

12th century:

Plate 1 Figure 5 is from the capital of an arch at St. Saviour's Priory in Glendalough, County Wicklow. The drawing gives the impression that the sides of the head were shaved and the hair was deliberately curled at the end. In the actual carving, the hair is slicked back at the sides and interlaced with adjacent design elements. These are stylistic elements of Irish Romanesque art and not intended to be a realistic depiction of an Irish hairstyle.

13th century:

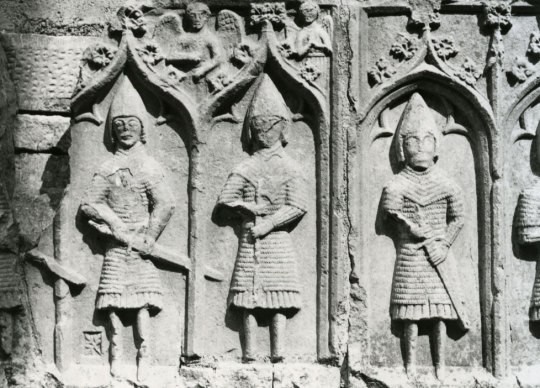

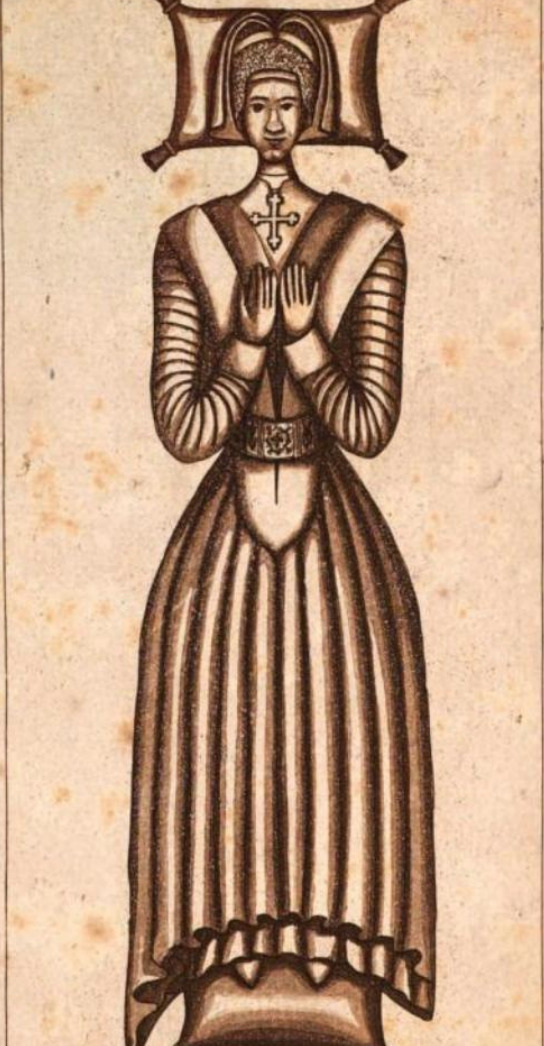

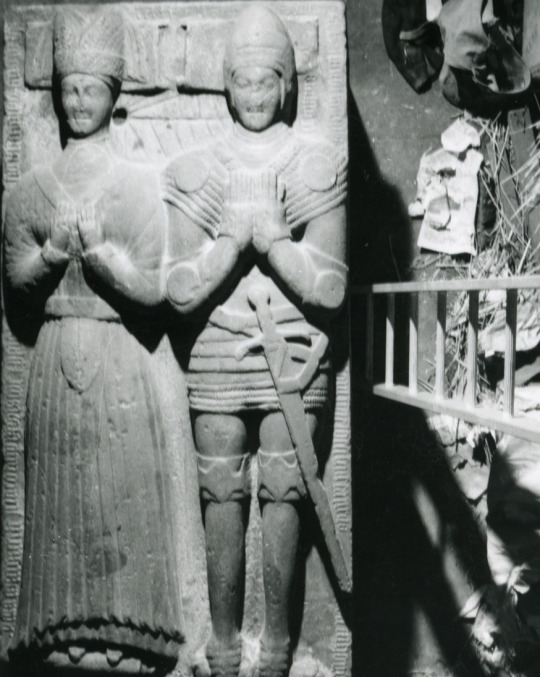

Plate 4 is the late 13th century effigy of Felim O'Connor, Dominican Priory of St. Mary, Roscommon with a frontal of gallowglasses added in the 15th c.

This drawing is pretty accurate, although the gallowglasses are lacking some details like their quilted cloth gambesons.

photos by Edwin Rae

I cannot find a good photo of Felim O'Connor's effigy, but Conor O'Brien's contemporary effigy at Corcomroe Abbey, County Clare wears the same style of clothing.

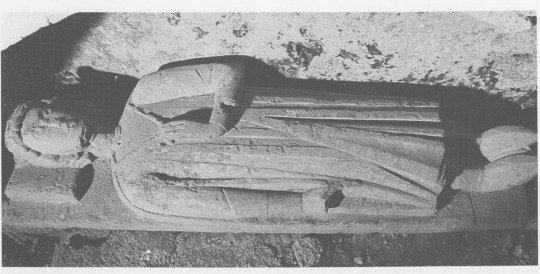

13-14th century?

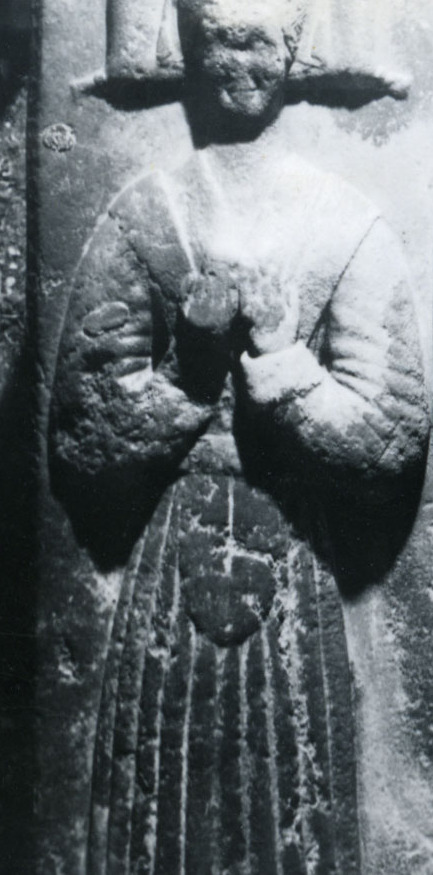

Plate 6 is based on a sculpture from Athassel Priory in County Tipperary. I can't find a solid date for this one. Athassel Priory was built c1200 and then burnt and rebuilt twice before it was dissolved in 1541. The clothing style of the carving makes me think it's from the earlier part of this time frame.

The biggest thing the drawing gets wrong is the gender. This is a man, not a woman. The "necklace pendent" on his chest might have actually been a brooch holding his cloak, but the sculpture is now too damaged to tell. The drape of fabric at his side, which Walker calls a train, is actually the edge of his cloak. The drawing also leaves out the way his become more fitted below the elbow.

15th century:

Plate 3 Figures 1-3 are based off a painting at Knockmoy Abbey.

I'm pretty sure those are houppelandes on the left and center figures. This continental fashion influence shows up elsewhere in 15th c. Ireland (Dunlevy 1989). The drawing omits the massive houppelande sleeves and shortens their hems.

The painting is now badly weather and difficult to see. This is a more accurate drawing published in 1904. Recent photograph here

Plate 5 figure 2 and plate 1 figure 6 come from a 15th c. grave at the Dominican Friary, in Strade, County Mayo.

Figure 2 is a decent representation, although it adds a center front slit to the leine which I don't think is actually there. Figure 6 gets the silhouette of the cotehardie a bit wrong and omits the hanging belt accessories, but its greatest crime is that it makes the top of the hood look like a separate object. Walker actually misidenifies it as a Scotch bonnet.

photo again by Edwin Rae

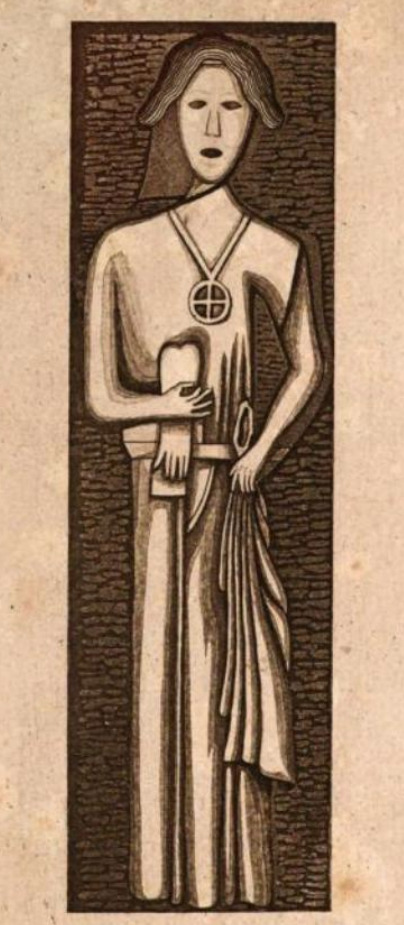

Plate 7 is Anne Plunket's effigy at St. Mary's Church, Howth, County Dublin. This drawing is decent, though the sleeves are a bit too slim. The cross necklace and belt decorations are no longer visible on the effigy.

photos by MVP Edwin Rae

Plate 8 figures 1 and 2 are both based on a late 15th c. tomb at the New Abbey in Kilcullen, County Kildare. Figure 1 is based off a carving which is probably depicting St. Brigid, which makes her headwear the wimple of an abbess, not a laywoman's kerchief Walker. The drawing, however, omits her telltale crozier. The drawing makes it look like she has cuffed sleeves, but that is actually just the folds of her brat draped over her arm. It also shows her as wearing 2 layers of skirts when she is actually wearing a single lower garment with a hem circumference so large that it puddles at her feet.

Figure 2 is based of Margaret Janico's effigy. The effigy is now too badly eroded to make out details, but it originally probably looked very similar to Margaret Janico's other effigy in St. Audoen's Church, Dublin. Unlike Anne Plunket's effigy above, the necklace and belt decorations are still faintly visible on the Dublin effigy. Figure 2 distorts the construction of the gown and headwear. This drawing makes the bodice of the gown look heavily stiffened or even boned like 17th c. stays. The houppelande on the effigy does not have stiffening in it.

effigy of Margaret Janico and husband at St. Audoen's Church, Dublin (photos, once again, by my man Edwin)

The headpiece in the drawing looks like a linen kerchief wound up to form a turban with a decorated fillet tied over it. The headpiece on the effigy is probably actually a truncated hennin with a veil pinned to it like the one in this mid-15th c Burgundian painting by Petrus Christus.

16th century:

Plate 9 is based on Katherine Molloy's early 16th c. effigy at Fertagh Church, in County Kilkenny. According to the artist's notes it was in "nearly perfect" condition at the time. I wish he had put more detail into the drawing.

(photo also by Edwin Rae)

17th century:

Plate 10 is based on The Taking of the Earl of Ormond in anno 1600. Walker's artist clearly fabricated some detail here, falsely giving the impression that triús were ankle-length. We know from extant examples from Kilcommon, Dungiven, and Killery that triús actually extended past the ankle, covering part of the wearer's foot (Dunlevy 1989, Henshall et al 1961).

Plate 11 was taken from the tomb of Sir Gerald Aylmer (died 1634) and Juliana Nugent. Sadly, it appears to have been destroyed in the early 19th c, so I have no further pictures of it. The clothing looks to me like typical 1630s English fashion with loose gowns over doublets, falling bands, and linen cuffs.

? Century

Plate 1 figure 4 is apparently from Old Kilcullen, County Kildare. I am not sure what this is based on. I haven't seen any Santa hats at Old Kilcullen. Or anywhere else in Medieval Ireland.

Bibliography:

Dunlevy, Mairead (1989). Dress in Ireland. B. T. Batsford LTD, London.

Henshall, Audrey, Seaby, Wilfred A., Lucas, A. T., Smith, A. G., and Connor, A. (1961). The Dungiven Costume. Ulster Journal of Archaeology, 24/25, 119-142. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20627382

Edwin Rae's invaluable collection of photographs of Late Medieval Irish art accessed via TARA.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gilt leather shoes in 16th c. Ireland

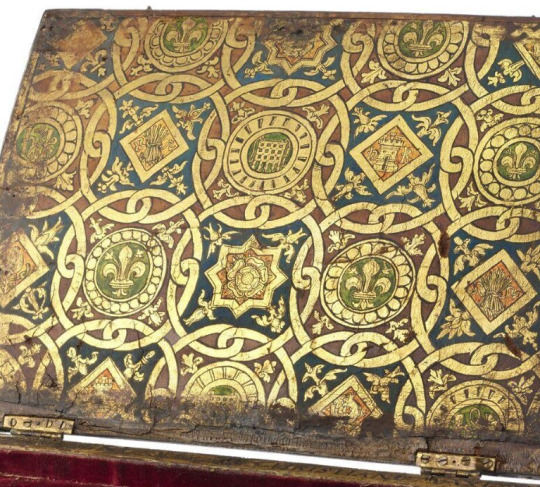

Drawing of a 16th c. Irish shoe by A. T. Lucas over a gilt leather wall hanging from the National Museum Machado de Castro in Portugal

In his 1518 description of Irish clothing, Laurent Vital says the following about shoes worn by Irish women and girls:

Elles portent petits soliers à singles semelles, bien jolys et mignotz, ouvrés pardessus d'aultres couleur de cuyr et parfois doretz de cuyr estainnet, comme s'il estoit doré, et comme j'ay veu porter les enffans parcy-devant, quant on leur achetoit des soliers de ducasse.

They wear little shoes with single soles, very pretty and cute, finely worked on top with other colors of leather and sometimes adorned with gilt leather, as if they were gilded, like the shoes which were bought for children at fairs in past times.

(translation by Dorothy Convery, edited by me)

In this post, I discuss what Laurent Vital meant by gilt leather and how it might have been used in 16th c. Irish shoes.

Sadly, we do not have any surviving examples of gilt leather shoes from medieval or early modern Ireland. This is unsurprising, because gilt leather is a fragile material which can be destroyed by excessive moisture, (Gilt Leather Society 2019) and most surviving Irish shoes have been found in damp locations like bogs, crannogs, and wells (Lucas 1956, Miller 1991, Nicholl 2023).

As Vital points out, although medieval doretz de cuyr or gilt leather looks like gilding, it is not really gold. Gilt leather was made from carefully prepared leather that was sealed with rabbit-skin glue and then had silver foil placed on top of it. The foil was then painted with a yellow varnish, giving it its golden appearance (Pereira 2012). Gilt leather could be stamped with patterns or painted with designs.

Painted gilt leather on a writing box belonging to King Henry VIII, made circa 1525 Victoria and Albert Museum collection

Learning what gilt leather actually was left me puzzled as to how the Irish made shoes out of it. Early 16th c. Irish shoes were largely made using a turnshoe or turn-welt construction. These methods involve sewing the shoe together inside out and then turning it right side out. In order to turn successfully, the shoe leather needs to be thin and flexible. Turnshoes are typically soaked in water to soften them before they are turned (Miller 1991, Nicholl 2023). I would expect that the layers of rabbit-skin glue and varnish in gilt leather would make the leather too stiff to turn. Also, as previously noted, being soaked with water is bad for gilt leather.

Although there are no surviving Irish examples of gilt leather shoes, there are a few continental European examples of episcopal sandals from the 12-13th centuries which appear to be embellished with gilt leather.

All of these shoes have a base layer of plain leather; the gilt leather is an applique which is glued or stitched on top. This method of construction is consistent with Vital's description that Irish shoes were estainnet i.e. adorned or plated*, with gilt leather. This method also explains how it was possible for Irish shoemakers to make shoes with gilt leather. Turnshoes of plain leather could be appliqued with gilt after they were turned right side out.

*estainnet: modern French étamer: to tin plate or to plate with metal

Irish shoemakers probably used gilt leather that was imported from Spain. During the Middle Ages, gilt leather was made in Spain and Portugal. It was not made elsewhere in Europe until the 17th century. (Pereira 2012). 16th c. Irish merchants imported luxury goods like silk and wine from Spain (Flavin 2011).

Neither Vital's account nor period illustrations give us any idea what kind of designs these Irish gilt shoes had on them. Rinceaux or scrolling foliage motifs like those on the sides of the 16th c. St. Brigid's shoe shrine are a likely option.

Further reading: Robert Gresh of the group Wilde Irish has written an interesting article on evidence for the use of gilt leather in 16th c. Irish armor. Download here

Bibliography:

Dictionnaire du Moyen Français 2020

Flavin, Susan (2011). Consumption and Material Culture in Sixteenth-Century Ireland. [Doctoral thesis]. University of Bristol.

The Gilt Leather Society. (2019). Conservation Challenges. https://giltleathersociety.org/conservation/conservation-challenges/

Lucas, A. T. (1956). Footwear in Ireland. Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society, 13(4), 309-394. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27728900

Miller, O. G. (1991). Archaeological Investigations at Salterstown, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland. [Doctoral thesis]. University of Pennsylvania.

Nicholl, John (2023). https://broguesandshoes.com/

Pereira, Franklin (2012). Gilt leather/guadameci in Coimbra – comments on documents of the 12th and 16th centuries. Boletim do Arquivo da Universidade de Coimbra, 15, 169-180. http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/5514

Ryan, Trisha (2022). Online Pop Up Talk: St. Brigid's Shoe Shrine. National Museum of Ireland Archaeology. https://www.museum.ie/en-IE/Museums/Archaeology/Engage-And-Learn/For-Adults/Online-Pop-Up-Talk-St-Brigid-s-Shoe-Shrine

Vital, Laurent (1518). Archduke Ferdinand's visit to Kinsale in Ireland, an extract from Le Premier Voyage de Charles-Quint en Espagne, de 1517 à 1518. http://research.ucc.ie/celt/document/T500000-001

#irish dress#dress history#16th century#gaelic ireland#historical fashion#shoes#historical women's fashion#irish history#brog#anecdotes and observations

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Glass Beads and Bracelets from Ireland dated between the 9th and 10th Centuries on display at the National Museum of Ireland-Archaeology in Dublin

The manufacture of multicoloured glass beads or bracelets, like the ones here, is known from pre-Viking times in Ireland and their continued use into the Viking Age. Some exceptional beads have pairs of perforations indicating that elaborately strung necklaces of beads were worn.

Such pieces of jewellery were worn as a symbol of status or wealth in society with the more complex the pattern the better.

Photographs taken by myself

#glass#reblog#jewelry#early medieval#9th century#irish dress#dress history#historical women's fashion#10th century#historical dress

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

The translation of the Senchus Mór Williams pulls that passage from continues with "Another version" which says:

Black, and yellowish, and gray, and blay clothes are to be worn by the sons of the Feini grades; and old clothes by the sons of the 'ogaire' chiefs, and new by the sons of the 'bo-aire' chiefs. The son of the 'aire-desa' chief wears clothes of a different colour every day, i.e. his cloak or his tunic is to be of a different colour every day, and he is to wear clothes of two different colours on Sunday; and he is to have both old clothes and new clothes.

The son of the 'aire-tuisi'-chief is to have all his clothes coloured; and is to wear clothes of two colours every day, both old and new, and to wear new clothes of two colours every Sunday. He is to have coloured clothes every day- clothes for Sunday and clothes for the festival, but each of them better than the other.*

The son of the 'aire-árd' -chief is to wear new clothes of two colours every day, and new clothes of two colours on Sunday and the festival day, but each of these clothes better than the other.*

The sons of the two inferior 'aire-forgill'-chiefs, the same as the last mentioned.

The sons of the superior 'aire-forgil'-chiefs, and the sons of the kings, are to have new coloured clothes at all times, but exceeding each other in quality (the Sunday clothes better than the weekday clothes, and those for the festival better than those for Sunday, as already specified), and all embroidered with gold and silver.

*Better than the other. Each exceeding the other in quality according to the order in which they have enumerated them.

Source: Hancock, W. N. (ed.) (1869). Ancient laws of Ireland: Senchus Mór, pt. II : law of distress (completed) (Vol. 2). Hodges, Foster, & Co., Dublin. (p. 146-149).

I assume by "another version", they mean another recension. I wish the translator specified the manuscript numbers.

This second version raises the question: "does the gold and silver embroidery count toward your total number of colors or is colors just fabric dyes?" The idea that your embroidery counts towards your color total makes sense with the Annals of the Four Masters quote. I was previously just picturing ancient Irish kings wearing a rainbow of stripes.

So I’ve been getting more into broader brehon law, not just marriage law, and is it true they had laws about how many different colors you could wear? I can’t find any sources about it but maybe I’m just not looking hard enough

That comes from one kind of famous (ish?) passage from the Annals, that reads as follows (from the O'Donovan translation):

Do I think it was something people followed? ...probably not, honestly. We don't see much reference to it elsewhere. Not to say there were NO restrictions, but it's to say that I think it's often taken 100% uncritically and you'd think we'd see more reference to it elsewhere, in the actual lawbooks, if that was the case. (Though, naturally, some of it's practical, in the sense that...would a slave be able to have more than one color? Being a slave? Very likely not.) It's the issue with all sumptuary laws, which is "to what extent were these things widely being used?"

To quote from Sparky Booker's "Moustaches, Mantles, and Saffron Shirts: What Motivated Sumptuary Law in Medieval English Ireland?": "In terms of implementation, the success of enforcement of sumptuary laws varied.11 Indeed, historians disagree about whether these laws were intended to be enforced fully, or whether they were 'primarily symbolic,' a method of 'affirm[ing] values' and even actively shaping the social world by

enshrining socio-economic divisions in law."

We know that medieval Ireland had a number of colors associated with the aristocracy: purple (like with the rest of Europe) seems to be common, white, red, like in this description from the Táin (Recension 1, O'Rahilly's translation):

"He held a light sharp spear which shimmered. He was wrapped in a purple, fringed mantle, with a silver brooch in the mantle over his breast. He wore a white hooded tunic with red insertion and carried outside his garments a golden-hilted sword."

Likewise, the famous description of Etáin in Togail Bruidne Da Derga (Stokes' translation):

"A mantle she had, curly and purple, a beautiful cloak, and in the mantle silvery fringes arranged, and a brooch of fairest gold. A kirtle she wore, long, hooded, hard-smooth, of green silk, with red embroidery of gold. Marvellous clasps of gold and silver in the kirtle on her breasts and her shoulders and spaulds on every side. The sun kept shining upon her, so that the glistening of the gold against the sun from the green silk was manifest to men."

For more on this, see Niamh Whitfield, "Aristocratic Display in Early Medieval Ireland in Fiction and in Fact: The Dazzling White Tunic and Purple Cloak", which she's generously put on Academia.

After the English colonization of Ireland, you have new sumptuary laws being put into place -- Booker discusses the earliest case we have, from 1297, when a hairstyle known as the "cúlán" was banned for Englishmen, with the enactment complaining that the Englishmen were taking it up to such an extent that they were getting killed after being mistaken for Irishmen. (I feel like there is a solution to this that does not involve banning the hairstyle, let me think...)

You had similar fines being imposed on saffron sleeves or kerchiefs for women, or wearing a mantle in general for men, as of 1466 in Dublin -- these aren't as a matter of maintaining social class so much as preserving a distinction between the English and the Irish (what's interesting, of course, is that the English had to have been adopting these fashions to some extent for the law to be needed.) And we see them routinely going back to this aversion towards saffron colors, since it was associated extensively with Ireland and Irishness, and a particularly high value one at that.

So: Eochaidh Eadghaghach -- that section in the annals provides the quote that says that this is a thing that happened -- I leave it to you to decide whether it was ever practiced or even in place in the first place. I think it might have, if only as a societal ideal, but I'm incredibly doubtful. We know that colors often ARE used as a way of marking social standing in the literature, but I don't think it was as regimented as that quote suggests. Sumptuary laws ARE better recorded in a post-Norman invasion context, usually (though not ALWAYS) as a means of marking out the Irish from the English populations (even though we know, both from this and other evidence, that these lines weren't always as firm as the authorities might have liked.)

I know that Kelly also goes into a lot of details re: colors and dyes in his "Early Irish Farming" -- if you're looking to get into the world of day to day life in Ireland, there isn't a better source.

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

So I’ve been getting more into broader brehon law, not just marriage law, and is it true they had laws about how many different colors you could wear? I can’t find any sources about it but maybe I’m just not looking hard enough

That comes from one kind of famous (ish?) passage from the Annals, that reads as follows (from the O'Donovan translation):

Do I think it was something people followed? ...probably not, honestly. We don't see much reference to it elsewhere. Not to say there were NO restrictions, but it's to say that I think it's often taken 100% uncritically and you'd think we'd see more reference to it elsewhere, in the actual lawbooks, if that was the case. (Though, naturally, some of it's practical, in the sense that...would a slave be able to have more than one color? Being a slave? Very likely not.) It's the issue with all sumptuary laws, which is "to what extent were these things widely being used?"

To quote from Sparky Booker's "Moustaches, Mantles, and Saffron Shirts: What Motivated Sumptuary Law in Medieval English Ireland?": "In terms of implementation, the success of enforcement of sumptuary laws varied.11 Indeed, historians disagree about whether these laws were intended to be enforced fully, or whether they were 'primarily symbolic,' a method of 'affirm[ing] values' and even actively shaping the social world by

enshrining socio-economic divisions in law."

We know that medieval Ireland had a number of colors associated with the aristocracy: purple (like with the rest of Europe) seems to be common, white, red, like in this description from the Táin (Recension 1, O'Rahilly's translation):

"He held a light sharp spear which shimmered. He was wrapped in a purple, fringed mantle, with a silver brooch in the mantle over his breast. He wore a white hooded tunic with red insertion and carried outside his garments a golden-hilted sword."

Likewise, the famous description of Etáin in Togail Bruidne Da Derga (Stokes' translation):

"A mantle she had, curly and purple, a beautiful cloak, and in the mantle silvery fringes arranged, and a brooch of fairest gold. A kirtle she wore, long, hooded, hard-smooth, of green silk, with red embroidery of gold. Marvellous clasps of gold and silver in the kirtle on her breasts and her shoulders and spaulds on every side. The sun kept shining upon her, so that the glistening of the gold against the sun from the green silk was manifest to men."

For more on this, see Niamh Whitfield, "Aristocratic Display in Early Medieval Ireland in Fiction and in Fact: The Dazzling White Tunic and Purple Cloak", which she's generously put on Academia.

After the English colonization of Ireland, you have new sumptuary laws being put into place -- Booker discusses the earliest case we have, from 1297, when a hairstyle known as the "cúlán" was banned for Englishmen, with the enactment complaining that the Englishmen were taking it up to such an extent that they were getting killed after being mistaken for Irishmen. (I feel like there is a solution to this that does not involve banning the hairstyle, let me think...)

You had similar fines being imposed on saffron sleeves or kerchiefs for women, or wearing a mantle in general for men, as of 1466 in Dublin -- these aren't as a matter of maintaining social class so much as preserving a distinction between the English and the Irish (what's interesting, of course, is that the English had to have been adopting these fashions to some extent for the law to be needed.) And we see them routinely going back to this aversion towards saffron colors, since it was associated extensively with Ireland and Irishness, and a particularly high value one at that.

So: Eochaidh Eadghaghach -- that section in the annals provides the quote that says that this is a thing that happened -- I leave it to you to decide whether it was ever practiced or even in place in the first place. I think it might have, if only as a societal ideal, but I'm incredibly doubtful. We know that colors often ARE used as a way of marking social standing in the literature, but I don't think it was as regimented as that quote suggests. Sumptuary laws ARE better recorded in a post-Norman invasion context, usually (though not ALWAYS) as a means of marking out the Irish from the English populations (even though we know, both from this and other evidence, that these lines weren't always as firm as the authorities might have liked.)

I know that Kelly also goes into a lot of details re: colors and dyes in his "Early Irish Farming" -- if you're looking to get into the world of day to day life in Ireland, there isn't a better source.

28 notes

·

View notes