#bratanna

Text

Photos of 16th-17th century Irish clothing

Extant garments in the National Museum of Ireland

Notes: The garments in this post are all bog finds which means their current color may not be their original color. Although some of these items were found with human remains, no photos of human remains are included in this post.

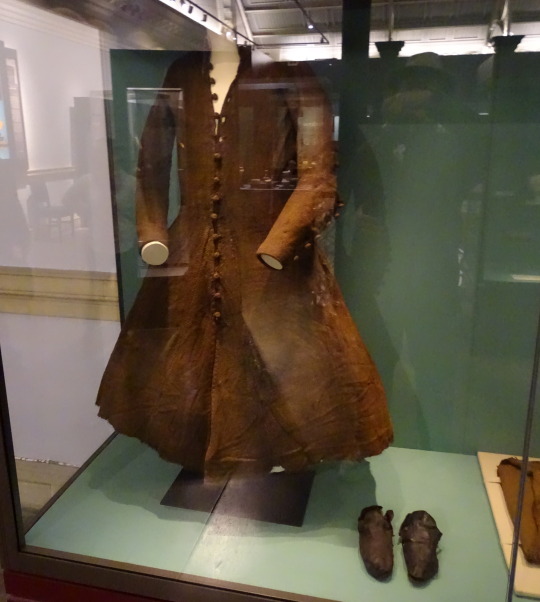

Killery Cóta Mór (great coat) and brogues:

photos by hayling billy used under non-commercial, share alike license

The Killery outfit comes from an adult male bog body found in Killerry parish, Co. Sligo in 1824. It includes a cóta mór, triús, a brat, and shoes which are on display in the museum, and a sheepskin biorraid (conical hat) which fell apart shortly after it was found (Briggs and Turner 1986).

Killery triús (trews):

photo by hayling billy

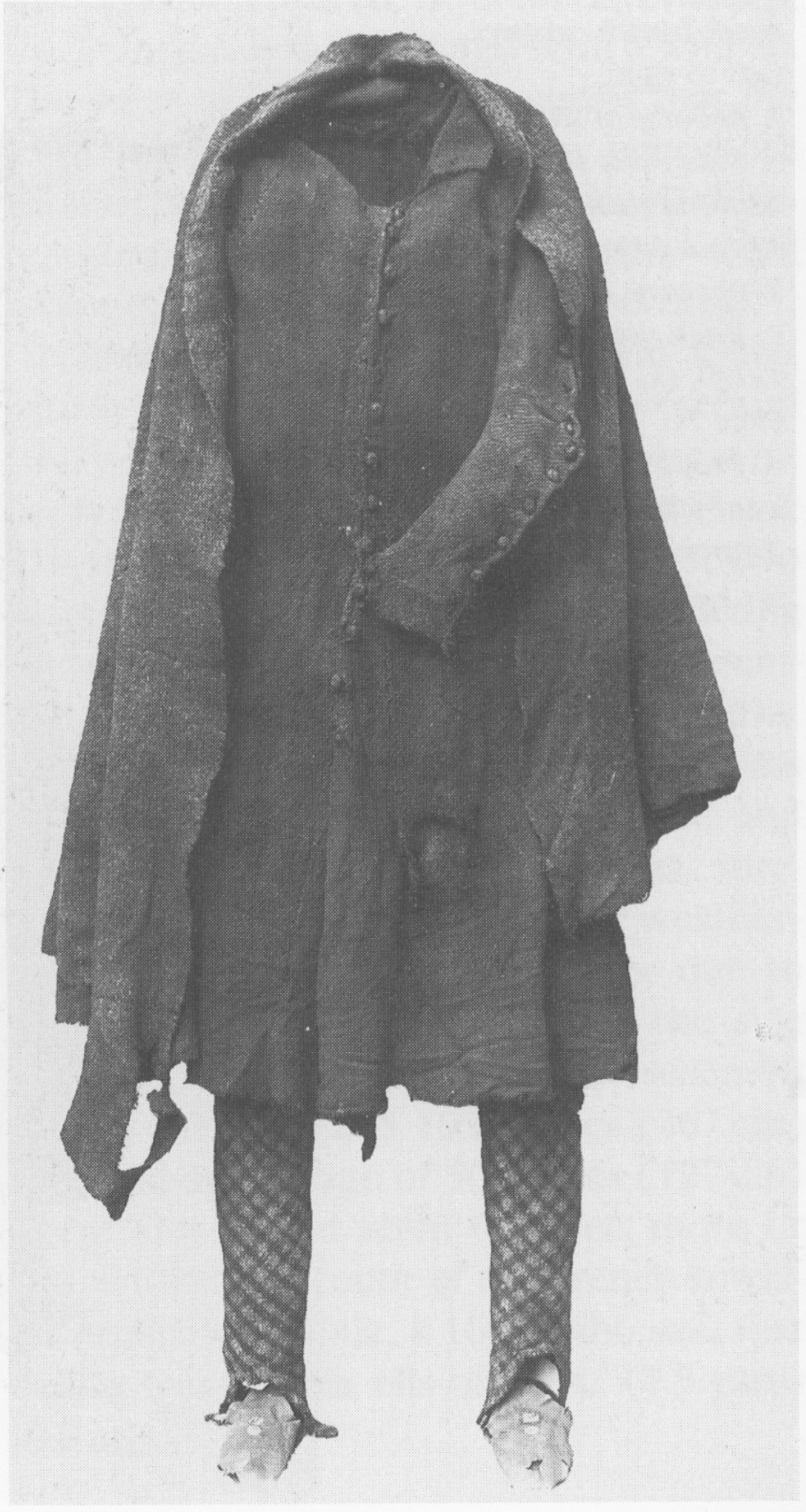

Killery outfit with and without brat:

The outfit is generally dated to the 17th c. (Dunlevy 1989). It matches Luke Gernon's 1620 description of Irish men's winter apparel:

"in winter he weares a frise cote. The trowse is along stocke of frise, close to his thighes, and drawne on almost to his waste, but very scant, and the pryde of it is, to weare it so in suspence, that the beholder may still suspecte it to be falling from his arse. It is cutt with a pouche before, which is drawne together with a string."

Additional photos of the outfit: cóta front, hem, buttons, and brat.

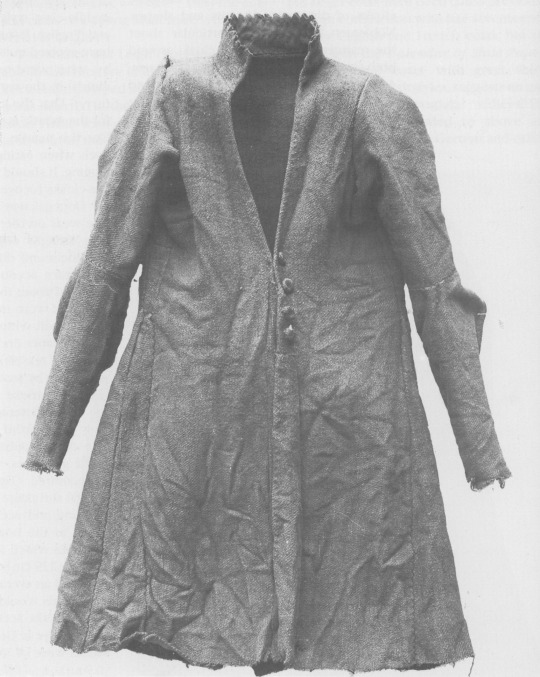

Shinrone gown:

photo by hayling billy

The Shinrone gown was found in a bog in 1843 in Co. Tipperary near Shinrone, Co. Offaly. Unlike the Killery outfit, there were no human remains or other items found with it (Briggs and Turner 1986). The ends of the sleeves and possibly also the bottom of the skirt are missing. The sleeves would have had wrist cuffs or ties that allowed them to be fastened around the wearer's wrists. It probably also had loops or rings along the U-shaped center-front opening for lacing. It is typically dated late 16th-early 17th c, based on its similarity to a circa 1575 illustration by Lucas DeHeere and to the dresses described by Luke Gernon in 1620 (Dunlevy 1989, McGann 2000). It could be older however, because Laurent Vital described dresses with this type of sleeve in 1518.

Copyrighted, better quality photos: left front, right front, back Additional details: side-front, front waistline

Tipperary Cóta Mór:

photos from Dunlevy 1989 and hayling billy

Another Cóta Mór. This one is from Co. Tipperary, exact find spot and date unknown. Like the Shinrone gown, it was not found with human remains or other items (Ó Floinn 1995). It is probably also from the 17th century (Dunlevy 1989).

Additional photos: front, side, front buttons, front detail, side

Brat and hats:

photo by hayling billy

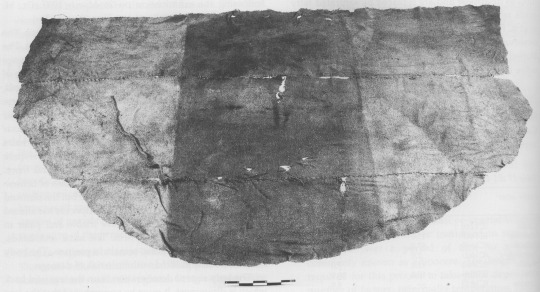

I haven't been able to find any clear photos of the label on this display, but based on the excellent condition and the presence of the leather tie, I think this is the Meenybradden woman's brat.

Closeup of the tie:

The Meenybradden woman is a bog body found in Meenybradden bog, Co. Donegal in 1978. The brat was wrapped around her as a shroud and secured with the leather tie (Delaney and Ó Floinn 1995). No other garments or artifacts were found with her, although she may have been wearing a linen garment such as a léine when she was buried. Linen tends to not survive in bogs. The Meenybradden woman has a calibrated radiocarbon date of AD 1130-1310, but some archaeologist have suggested humic contamination from the peat may be throwing off the dating. Her brat is identical in cut to others from the 16th-17th centuries (Delaney and Ó Floinn 1995).

Meenybradden brat laid flat. (photo from Delaney and Ó Floinn 1995)

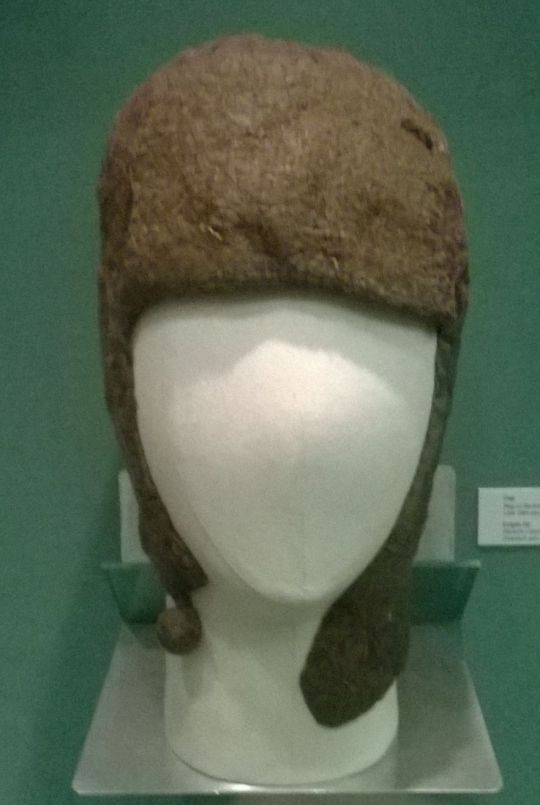

Wool hats:

Hats from Boolabaun, Co. Tipperary made of wool felt which has been cut and sewn to form the shape. They have togs of unspun wool worked into them giving them the appearance of faux fur. Dunlevy suggests a 15th-16th c date for them (Dunlevy 1989, McClintock 1943).

Wool cloak:

photo by hayling billy

The museum label says it's from Glenmalin bog, Malinmore, Co. Donegal, but I think this may be a mistake. According to Ó Floinn (1995), the artifact with accession number 1946:416 from Malinmore, Co. Donegal is a bale of linen. Ó Floinn's table also gives accession number 1946:416* for a group of clothing from Owenduff, Co. Mayo which includes a gown, a jacket, and a cloak. If the cloak in the photo is actually the one from Owenduff, it is probably from the 17th c (Dunlevy 1989). Alternatively, someone might have misidentified a wool cloak as a bale of linen. The museum label dates this as late Medieval to post-Medieval.

*Either Ó Floinn made a typo or this is a mistake in the museum records. Museums are not supposed to give the same accession number to 2 different artifacts. In the NMI's defense, 1946 was probably a messy year for everyone.

Bibliography:

Briggs, C. S. and Turner, R. C. (1986). Appendix: a gazetteer of bog burials from Britain and Ireland. In I. Stead, J. B. Bourke and D. Brothwell (eds) Lindow Man: the Body in the Bog (p. 181–95). British Museum Publications Ltd.

Delaney, M. and Ó Floinn, R. (1995). A Bog Body from Meenybradden Bog, County Donegal, Ireland. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 123–32). British Museum Press.

Dunlevy, Mairead (1989). Dress in Ireland. B. T. Batsford LTD, London.

Gernon, Luke (1620). A Discourse of Ireland. https://celt.ucc.ie/published/E620001/

McClintock, H. F. (1943). Old Irish and Highland Dress. Dundalgan Press, Dundalk.

McGann, K. (2000). What the Irish Wore/The Shinrone Gown — An Irish Dress from the Elizabethan Age. Reconstructing History. http://web.archive.org/web/20080217032749/http:/www.reconstructinghistory.com/irish/shinrone.html

O’Floinn, R. (1995). Recent research into Irish bog bodies. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 137–45). British Museum Press.

Vital, Laurent (1518). Archduke Ferdinand's visit to Kinsale in Ireland, an extract from Le Premier Voyage de Charles-Quint en Espagne, de 1517 à 1518. translated by Dorothy Convery and edited by me. https://irish-dress-history.tumblr.com/post/721163132699131904/laurent-vitals-1518-description-of-ireland

#16th century#17th century#irish dress#dress history#gaelic ireland#historical men's fashion#historical women's fashion#bog finds#irish history#historical dress#brog#bratanna#irish mantle#headwear#triús#cóta mór

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the Comics: Rebirth's Updates to Batman and Zatanna's Relationship - ComicBookWire

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Irish warriors and poor men by Albrecht Dürer -1521

Painting depicting 2 gallowglass and 3 kerns. There is no evidence that Dürer ever went to Ireland, so this painting may be based on second-hand information. It is nevertheless a nice portrayal of some elements of 16th century Irish dress.

The gallowglass on the left side of the painting wears a cotún, a type of quilted cloth armor. His square-toed shoes are probably English or continental fashion, not Irish. The kern in the center of the painting is wearing a brat (Irish mantle) that is probably trimmed with pile-woven wool. His shoes have the pointed toes and high backs that were common in historic Irish bróga. The 2 kerns to his left are both wearing a short jacket called an ionar.

All 3 of the kerns have glib haircuts. The gallowglass and 2 of the kerns have a style of mustache called a crommeal. Both glibs and the crommeal were banned by the British crown in the 16th century as part of British colonialist efforts to eliminate Irish Gaelic culture.

#gallowglass#kern#irish history#16th century#art#irish mantle#irish dress#irish hairstyle#historical fashion#gaelic ireland#historical men's fashion#ionar#cotun#bratanna#brog

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

The shrine of St Caillín of Fenagh was made in 1536. It features several figures etched into a silver frame. The figures are tiny, the silver strips that bear them are less than 1 cm wide (approx. 3/8 in).

They are nevertheless important, because they are one of the few surviving portrayals of 16th century Gaelic Irish dress created by an Irish artist.

The first figure is believed to be Margaret O'Brien who is mentioned in the inscription on the shrine. She may be wearing a gown with a split-front skirt showing an embellished petticoat or forepart underneath. Gowns of this style were worn by Anglo-Irish women like Marion Sherle, wife of Sir Christopher Barnewall, in this 1589 effigy:

Similar gowns were popular in England during the 16th century.

The other figures on the shrine are believed to represent members of the O’Ruairc clan. According to its inscription, the creation of the shrine was commissioned by Brien O'Ruairc.

They are similarly dressed in bratanna and hats, some may have veils under their hats.

One woman wears a wimple similar to the 'civil' Irish woman on John Speed's map of the kingdom of Ireland.

Information about the shrine was taken from a presentation by Paul Mullarkey of the National Museum of Ireland, accessible here: https://www.ria.ie/shrine-st-caillin-fenagh-and-its-place-irish-late-medieval-art

#16th century#art#gaelic ireland#irish mantle#bratanna#historical women's fashion#headwear#irish dress#dress history#anglo irish#irish history

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

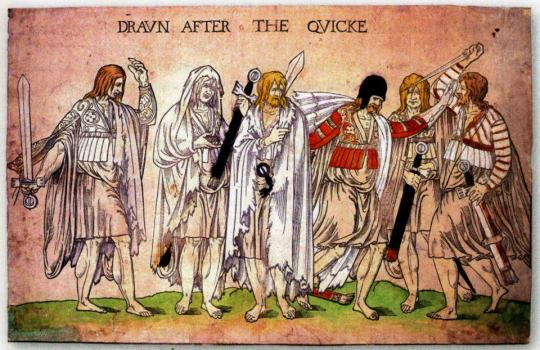

Drawn after the Quick

(ie Drawn from Life)

Colored woodcut print by an unknown English artist, generally dated to 1540-1550, possibly depicting Irish kerns who fought for King Henry VIII at the siege of Boulogne in 1544.

All 6 of the men wear a léine (linen tunic) with an ionar (short jacket) over it, and the 4 on the left have a brat (wool mantle). The men have their léinte rucked up to knee length and secured at the waist with a belt or cord. The léinte have the wide hanging sleeves that are typical of 16th c. Gaelic fashion. They also have a deep center-front opening, a feature which matches Burgundian courtier Laurent Vital's description of clothing he saw during his 1518 visit to Kinsale, Co. Cork:

"Generally the men, women, and young girls wear their shirts open to the waist. Most young women and girls have their chests naked to the waist." (translation taken from a lecture by Katherine Bond)

The ionair in this print are very similar in cut to the ionar of the Kilcommon bog outfit. The hat worn by the man in the red ionar is also similar to the hat of the Kilcommon outfit.

The floral scroll design seen on some of the ionair was a popular embroidery motif in England during the 16th-early 17th centuries. It also shows up in 16th c. Irish art like St. Brigid's shoe shrine.

4 of the ionair and all of the visible scabbards have fringe on them. Fringe was a popular embellishment in 16th c. Ireland. The use of fringe is mentioned in several 16th and early 17th c. descriptions of Irish clothing. Fringes made of wool and fringes made of silk were imported into Ireland during the 16th c.

In spite the claim that it was drawn from life, this print includes some stylistic exaggeration. The sword blades are depicted as having a bulbous tip, which actual Irish ring-pommel swords are not. Compare the swords in the print to this extant 16th c. sword from Tully Lough, Co. Roscommon in the NMI:

The print is currently in the collection of the Ashmolean Museum. https://collections.ashmolean.org/object/737327

Bibliography:

Arnold, Janet, Tiramani, J., & Levey, S. (2008). Patterns of Fashion 4. Macmillan, London.

Dunlevy, Mairead (1989). Dress in Ireland. B. T. Batsford LTD, London.

Flavin, Susan (2011). Consumption and Material Culture in Sixteenth-Century Ireland. PhD thesis.

McClintock, H. F. (1943). Old Irish and Highland Dress. Dundalgan Press, Dundalk.

Irish Ring Pommel Sword: New Insight into Use

National Museum of Ireland talk on St. Brigid's shoe shrine

Depicting and Describing Dress in Early Modern Ireland: lecture by Dr. Katherine Bond

#irish dress#gaelic ireland#irish history#irish mantle#bratanna#leine#ionar#fringe#embellishment#historical men's fashion#headwear#art#16th century#anecdotes and observations#dress history#bog finds#extant garments

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

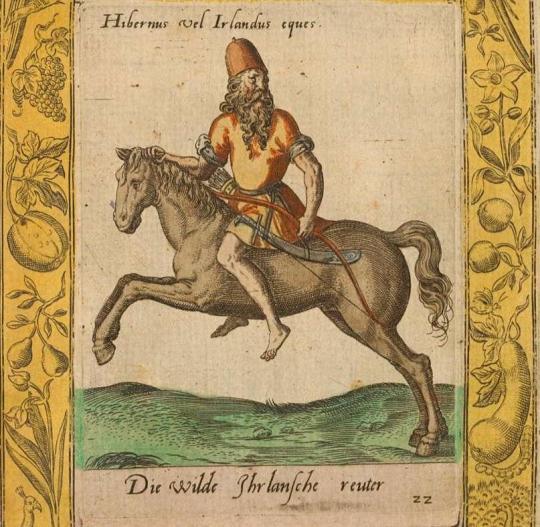

Questionable Images of Irish Horsemen

As a follow-up to my post about the problematic nature of costume books, I want discuss some of the other portrayals of the Irish that show up in them.

'A "wild" Irish rider' from Illustrations de Diversarum gentium armatura equestris by Abraham de Bruyn published c. 1578. Several copies of this book exist including one in the Bibliothèque nationale de France and one in the Wellcome Collection.

Looking at this image, I think that Abraham de Bruyn either never actually saw an Irish rider and based this off description alone, or he was intentionally mocking the Irish. There are 2 glaring issues with this portrayal which, when taken together, convince me of this.

The first issue: the Irish man is riding bareback and bridleless. He is the only rider in de Bruyn's book of equestrians shown without some kind of tack. The 16th century Irish rode with saddles and bridles. Multiple primary sources confirm this. John Derrick, even though his book was anti-Irish propaganda, still showed the Irish using saddles and bridles:

The taking of the Earl of Ormond in anno 1600 also shows Irish horses with saddles:

The text next to the horses says, "More horses unbrideled feedinge [sic]," which implies that Irish horses wore bridles when not feeding. English writers Edmund Spenser and Luke Gernon, who lived in Ireland in the late 16th and early 17th centuries respectively, both explicitly described how the Irish saddle and style of riding differed from the English.

My second issue with de Bruyn's illustration: the Irish rider is grasping the horse's left ear in his right hand while the horse is galloping. There is a partial explanation for this bizarre position. An account from an anonymous traveler who visited Ireland c1579 mentions that the Irish mounted by seizing the left ear of the horse (Maxwell 1923), but de Bruyn's rider is shown riding a galloping horse. Even if the Irish were grasping the horse's left ear in their right hand to mount, I cannot imagine that they continued doing so while riding. It would be problematic for several reasons. Horses bob their heads up and down while they are running. (If you have never ridden a horse, this video gives a decent idea what that looks like.) This bobbing would make it difficult and tiring for the rider to keep hold of the horse's ear while they are running. Furthermore, grasping the horse's opposite ear while riding would require leaning forward over the horse's neck while simultaneously leaning slightly sideways. This would incredibly awkward and probably throw off the rider's balance. (It has been 20 years since I took horseback riding lessons, but I do remember that balance is important.) Finally, horses like to move their ears around, and I think they would fight this.

However, in spite of its mistimed portrayal, the fact that de Bruyn seems to have been aware of this specific detail of Irish horsemanship, but either didn't know about or chose not to include Irish tack suggests that he was either working with incomplete information or deliberately making a mockery of the Irish. Neither of these options makes me inclined to trust this image as a depiction of Irish clothing.

Irish soldier (left) and Scottish soldier (right) from Sacri Romani Imperii Ornatus. Item Germanorum, diversarumque gentium peculiares vestitus. vol. 1 by Caspar Rutz published 1588

Caspar Rutz' book Sacri Romani Imperii Ornatus includes a very similar-looking Irish soldier. From the publication dates, I initially assumed that Rutz' soldier was based on de Bruyn's rider. With one small exception, their outfits are basically identical.

Both the rider and the soldier wear a knee-length tunic with long fitted sleeves, belted at the waist. The tunic flares out significantly at the bottom, suggesting that it has triangular gores or godets in the lower part. The tunic is a soft, unstructured garment, a clear contrast to the shaped doublet of Rutz' Scottish soldier. Doublets from this period could be heavily stiffened and shaped with interlining (Arnold 1985). The tunic is probably made of linen or light-weight wool.

The shorter length and long tight-fitting sleeves make this tunic significantly different from the typical 16th c. léine. The 16th c. léine was an ankle-length garment that could be belted up to waist length and had voluminous hanging sleeves that stopped several inches above the wrist. The tunic in Rutz' and de Bruyn's prints does look like one in Albrecht Dürer's 1521 painting of 2 gallowglass, so it may be something that the Irish wore for combat.

A typical 16th c léine (left) and Dürer's gallowglass (right)

The men in both Rutz' and de Bruyn's illustrations are wearing sugarloaf hats embellished with feathers. The sugarloaf hat was a continental fashion rather than an Irish one. Several extant examples of imported 16th-17th c. hats have been found in Ireland though (Dunlevy 1989), so some Irish people were wearing foreign styles during this period.

Both the soldier and the rider are bare-legged. The Irish riding barelegged is another detail mentioned in the c1579 anonymous traveler's account (Maxwell 1923).

Both outfits include a simple knee-length cloak which fastens at the throat, but these cloaks have a significant difference in cut. The neckline of the cloak on de Bruyn's rider has a collar with straight or concave edges and a square corner. These square-cut collars are found on English and continental cloaks in this period (Arnold 1985). The neckline of the cloak on Rutz' soldier, on the other hand, has a turnback with a convex edge and no visible corners. This is a feature of an Irish brat rather than an English cloak.

de Bruyn's rider in an English cloak vs Rutz' soldier possibly wearing an Irish brat

This subtle but culturally significant difference makes me believe Rutz' illustration is not a copy of de Bruyn's, though they may have both been copied from the same source image. de Bruyn likely either didn't know or didn't care about the difference between a cloak and a brat.

Another German book, Stammbuch des Hans Lorenz von Trautskirchen und des Hans Jörg von Elrichshausen unter Verwendung von Bruyn, Abraham de: Diversarum gentium armatura equestris, published between 1575-1615 states in its title that it uses de Bruyn's illustrations of riders. Its version of the Irish rider is slightly different though.

This version leaves off the hat decoration and the cloak completely but keeps the unrealistic ear-grasping position of the rider. The position in the image is only possible because of the unrealistic proportions of the horse. Even on a small horse like a Shetland pony, this actually wouldn't work. Grasping the horse's ear would require the rider leaning forward or at least straightening out their arm.

Rider on a Shetland pony. Note the distance between the rider's hands and the pony's ears.

Finally, there is a painting of an Irish man in Kostüme und Sittenbilder des 16. Jahrhunderts aus West- und Osteuropa, Orient, der Neuen Welt und Afrika, published c.1575-1600 which might be based off of these.

I am not sure why he appears to have just one hanging sleeve or why his triús appear to be rolled up at the ankles. The images in this book appear to be poor-quality copies of other books. I discussed the Irish woman in this book in my previous post.

Biblography:

Arnold, Janet (1985). Patterns of Fashion 3. Macmillan, London.

Derrick, John (1581). The Image of Irelande. London.

Dunlevy, Mairead (1989). Dress in Ireland. B. T. Batsford LTD, London.

Gernon, Luke (1620). A Discourse of Ireland.

Maxwell, Constantia (1923). Irish History from Contemporary Sources (1509-l610). Unwin Brothers LTD, London.

McClintock, H. F. (1943). Old Irish and Highland Dress. Dundalgan Press, Dundalk.

Wilde Irishe (2020). Horseboys: Irish Lackeys, Irish Footmanship.

#art#irish dress#irish history#dress history#16th century#historical fashion#historical men's fashion#gaelic ireland#irish mantle#headwear#bratanna

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Laurent Vital on Irish clothing in 1518

Burgundian courtier Laurent Vital visited Kinsale, Co. Cork in 1518. He wrote an account of the visit titled "Speaking a little of the country of Ireland" which included descriptions of Irish people and culture. Vital was less bigoted toward the Irish than many of the 16th c. English writers. His writing was still somewhat biased though, because his information came from a French-speaking (probably Anglo-Irish) Irishman who was prejudiced against the rural Gaelic Irish.

Vital's account was only translated into English in 2012, so it is not included in Irish dress history books, because all of them (Dress in Ireland by Mairead Dunlevy, Before the Kilt by Gerald Kelly, Bríd Mahon's books, H. F. McClintock's books) were published before 2012. This is unfortunate, because Vital's descriptions include a lot of details of Irish dress.

The 2012 translation has some flaws. I think the translator, Dorothy Convery, was not knowledgeable about 16th c. Irish dress and possibly not the most familiar with 16th c. French, because she completely misinterpreted some of the clothing descriptions. I have done my best to correct these, but I don't actually know French, so my revised version is not perfect either. If anyone has suggestions for improving it, let me know. I used Randle Cotgrave's 1611 A Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues, Dictionnaire du Moyen Français, version 2020 (DMF 2020), the University of Chicago's compilation of historical French dictionaries, Wiktionary, and honestly, google translate for this. (Google translate actually does a really good job with French, like 60% of the time.)

The original French text of Vital's account is available here. Convery's complete translation is here. Content Warning if you decide to read the Vital's complete account: It contains a description of assault with a possible forced marriage. Also, Vital was kind of obsessed with breasts. I am only including the parts describing Irish dress and hairstyles in this post. Translation footnotes are at the end of each page. I couldn't figure out a nicer way to format them on tumblr.

Excerpts from "Speaking a little of the country of Ireland" translated by Dorothy Convery and revised by Deidre

p. 285

The inhabitants [of Ireland] are very strangely and singularly costumed and would that it is so well described that you might picture how they dress just as I saw them, both the men and the women. For to see them is enough to make you laugh. Firstly married women wear their finery, and linen head coverings (1); some yellow and others white. When they are women of status, they have chemises with wide sleeves, worked around the collar and in the seams with silk needlework of different colours. Many of them had their hair cropped in front and back, except for two tresses of hair at either side, which are an ell long. They plait these like children here making hats from rushes and then secure them so they do not come undone. And with the tops of their heads so adorned, these loops of hair braided accordingly hang down in front more or less to their waists, in such a way that these women can put the ends into their kerchiefs (1), which they secure with wool tape (2). These women have their kirtles or petticoats (3) punched (4) there as they were worn alone in the past, with rings placed over (5) the bustline to support their breasts. And above their dresses they wear wide fillets (6) and big belts decorated with beautiful buckles, some of gilded silver, also of copper, metal or brass, according to their rank. Their dresses have loose sleeves, open the length of the arms, unfastened to hang (7) very nicely. Generally, the men, women and young girls wear their chemises (8) open to the waist, without any difference between them except that the women's chemises are, as they are over here, wide at the bottom, made with gores (9) with 4 seams, (10) if needed. So that most young women and girls have their chests naked to the waist; it is as common there to see or touch the breast of a girl or woman, as it is to touch her hand. And so, there are as many different fashions and customs as there are countries.

Translation notes:

coevrechief: kerchief or headcovering

patelette: Bande d'étoffe (DMF 2020) cloth tape, wool or possibly linen

cottes ou cotelettes: kirtle, or possibly coat, or frock/gown (see Cotte in Cotgrave 1611)

ponchonnées: pierced or punched, meaning eyelets made with an awl, or possibly decorative stamping

rondz eslevez: possibly metal lacing rings which were in use by the late 15th c. This whole sentence is confusing to me.

tissu: a bawdricke, ribbon, fillet, or head-band of woven stuffe (Cotgrave 1611)

lachiés à traillette: laschier: let go, release (DMF 2020) trailler: to trayle a Deere (Cotgrave 1611) to trail or to hang. I think this sentence is describing hanging sleeves like those on the Shinrone gown, but it could also be interpreted as "Their dresses have wide sleeves, open the length of the arms, loose to hang very nicely."

I am keeping the original French usage of chemise to mean both the man's and woman's garment, because Irish uses the same word, léine, for both.

ghéron: I think this word is derived from the Old French giron meaning gusset or triangular shape.

genoulx: knee, also join (ie seam in this context) (cf. genouille: full of joins (Cotgrave 1611))

p. 286

The women and girls there wear coloured stockings (1) of red and green and others that they like, better narrowed and tightened with garters than those of Castile. They wear little shoes (2) with single soles, very pretty and cute, worked over other colors of leather and sometimes gilded with tinned leather, as if it were gilded (2), like the shoes which were bought for children at fairs in past times.

The place was full of beautiful young women and also girls of marriageable age who were very charming and pleasant. Unmarried young women went bareheaded in summer time with their hair tied back in the same way as maidens over here; and they wear on their heads garlands of flowers or greenery.

Translation notes:

chausses: stockings or hose in Middle French (wiktionary.org)

solier: alternate spelling of soulier: shoe (Cotgrave 1611)

ie like with gold

p. 287-288

Having heard about the rig-out of the women and girls, listen how the men are kitted out. For sure, even more strangely than the women, and particularly the rural people and the savages; for they were shorn and shaved one palm above the ears, so that only the tops of their heads were covered with hair. But on the forehead they leave about a palm of hair to grow down to their eyebrows like a tuft of hair which one leaves hanging on horses between the two eyes. They are strangely bearded, some shave their beards just to just above the mouth and others to below the mouth. Others shave some places and let their beards grow in tufts. These men have their chemises open there, down to the belt, without having sleeves, so their arms are naked. They are belted (1) in heavy linen which goes one and a half times around them, and goes nearly from their neck to their feet, and they go with naked feet and bare legs.

[. . .skipping the part on weapons because I don't know enough about weapons. . .]

These men dress and enshroud (2) themselves in large hairy mantles, worn over their heads as the women in Brabant wear their huiks. (3) This mantle only goes halfway past the belt; and over that a long shortening (4) of linen. Thus shorn, bearded, armed and barefoot — as I said — imagine how strange this costume is to look at. I must say, I have never seen anything like this before even in a painting.

Translation notes:

chaindent: from chainture the Middle French spelling of ceinture

affubler: to cloath, clad, put on; to attire, or cover with, muffle, or enwrap in, hide, or shrowd, under clothes. (Cotgrave 1611)

huik: a type of cloak worn by women in the Low Countries. It typically had a bill-like brim to shade the wearer's face. more info

escourcoeul: probably the same origin as écourter: to shorten. I think Vital is describing the Irishmen's practice of shortening their léinte by pulling them up over their belts, but I'm not confident about the translation of this sentence.

#irish dress#irish history#16th century#headwear#historical men's fashion#historical women's fashion#dress history#historical fashion#leine#irish hairstyle#gaelic ireland#irish mantle#bratanna#brog#french translation problems#anecdotes and observations

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of chieftain Sir Neil O'Neill (Irish: Niall Mac Anrí Ua Néill) painted in 1680 by John Michael Wright. Both of the men in the painting are wearing several elements of historic Irish Gaelic dress.

#17th century#triús#saffron dye#fringe#Irish dress#biorraid#annular brooch#Irish mantle#bratanna#gaelic ireland#Irish history#dress history#art#historical men's fashion#brog

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Figures from John Speed's map 'The Kingdome of Irland' [sic], created circa 1610. The various color versions published of these images were probably colorized by someone who had never been to Ireland and are not necessarily accurate.

Note: ‘Civil’ and ‘Wilde’ ARE NOT descriptions of socioeconomic status or social class. This is a modern misunderstanding I have seen repeated a lot. In the 16th and 17th centuries, they were indicators of acculturation level. The ‘Civil’ Irish were Anglicized. They spoke English; they wore English clothing styles; they followed British laws. The ‘Wilde’ Irish still kept Gaelic Irish customs. They spoke Irish; they wore Gaelic Irish clothing; they followed Brehon law. Of course, as these prints show, the ‘Civil’ Irish and even the Anglo-Irish gentry wore some Gaelic Irish clothing in the early 17th century.

The gentleman, the gentlewoman, and the ‘civill’ man are all wearing elements of early 17th c English fashion including their doublets, their standing collars (the men) or ruff (the woman), and their felt hats (the men). The men have English-style beards and haircuts. The gentlewoman has her hair done up and decorated in English style. The men are probably wearing English-style breeches, but these are hidden by their mantles.

The gentleman, the ‘civill’ man, and the ‘civill’ woman are all probably wearing a kind of bróg or Irish shoe now know as a Lucas type 5. These bróga differed from similar English styles in that they had flat soles and were held together with a leather thong rather than thread or nails. This kind of bróg was worn in Ireland into the 19th century.

The ‘civill’ woman wears a linen wimple on her head. During the 16th century, coifs and hoods replaced wimples in English fashion, but Irish women continued to wear them.

The ‘wilde’ man and woman are both bareheaded with free-flowing hair. A 17th century English woman would never leave her house this way, but it was common in parts of Ireland. The man has long bangs known as gilbs. This hairstyle was popular in 16th century Ireland and banned under British colonial rule. The ‘wilde’ man’s lack of beard is also Irish fashion.

The ‘wilde’ man is wearing tight-fitting trúis on his legs. The groin piece being made of a different fabric is something seen on extant trúis of the Killery bog outfit. He is possibly wearing knee-high leather boots. Similar boots are shown in some 16th century costume book illustrations. The shagginess at the top might indicate that they are made of rawhide with the hair still on.

Finally, all 6 of them wear an Irish brat. These illustrations show that the brat came in a variety of lengths and materials. The thick shaggy border on the bratanna of the gentry, the ‘wilde’ woman and the ‘civill’ man is probably pile-woven wool. The ‘civill’ woman and the ‘wilde’ man have fringed edges on their bratanna.

Bibliography:

Arnold, Janet, Tiramani, J., & Levey, S. (2008). Patterns of Fashion 4. Macmillan, London.

Arnold, Janet (1985). Patterns of Fashion 3. Macmillan, London.

Dunlevy, Mairead (1989). Dress in Ireland. B. T. Batsford LTD, London.

Lucas, A. T. (1956). Footwear in Ireland. Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society, 13(4), 309-394. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27728900

McClintock, H. F. (1943). Old Irish and Highland Dress. Dundalgan Press, Dundalk.

#art#17th century#irish mantle#irish history#irish dress#gaelic ireland#bratanna#brogues#brog#anglo irish#historical men's fashion#historical women's fashion#dress history#wilde irish#triús#I will probably write a more detailed post on the 'civil' and 'wilde' thing in the future#i spent way too long on this

19 notes

·

View notes