Text

On This Chilean Island, the Whole Community Helps Move Your House

The actual building. Sometimes across water.

Moving a house on Chiloe Island, known as a minga. Francisco Negroni/Alamy

Moving house can be a real pain. But shuttling some boxes, a couch, and other detritus from point A to point B is small potatoes compared to the ordeal of moving house for the islanders of Chiloé, who physically move their homes from place to place—sometimes over water.

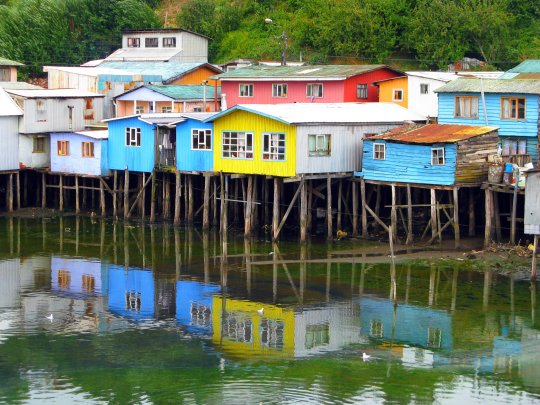

Floating off the coast of southern Chile, the misty archipelago of Chiloé is a pastoral, sheep-dotted, and drizzly, the austral equivalent to Ireland. Verdant forests fringe on undulating fields that roll down to the sea, where palafito stilt houses perch over tidal bays. The ocean provides a constant flow of fresh catches, with the promise of sighting whales, dolphins, and penguins (which are not on the menu). The snowy tips of volcanoes on the mainland pierce the skyline.

Meaning “seagull place” in the indigenous Mapuche language, Chiloé is isolated from the mainland, with no connecting bridges. The only way on or off is by boat or small airplane. This separation has birthed a distinct way of life that distinguishes Chilotes—as the archipelago’s inhabitants are known—from their onshore brethren. Ask any Chilote, and they will say that they are Chilote first, Chilean second. They are a close-knit island community of farmers, fishermen, and sheep herders. An unsinkable sense of heritage keeps them anchored to their wind- and water-battered islands.

Palafitos on Chiloe Island. Christian Cordova/CC BY 2.0

Every once in a while, due to non-arable farmland, the threat of tsunami, the danger of erosion, or the rising tides, Chilotes need to move house. And when they do, their house comes with them. It’s a real show, and it’s known as a minga.

Translating to “a meeting of neighbors and friends to do some free work for the community,” a Chilote minga can refer to a range of communal events, such as a gathering for harvest, but is most famous as a house-moving ceremony. These actions are done without payment, but with the expectation of reciprocity in the future should it be needed.

“The minga is a collective work where a community comes together to help each other, and the concepts of solidarity and brotherhood are the pillars of this action,” says Maria Teolinda Higueras, head of the Quemchi Public Library in Chiloé. “What matters is that the neighbor achieves his objective, and that payment is not necessary.”

The custom of mingas started before the Spanish arrived in Chiloé in the 1500s, and is believed to have been brought to the islands by the Huilliche tribe, who learned the practice of communal work without pay from the Incas. The minga was then adopted and used by the Spaniards.

Higueras says modern mingas originated in the 1950s, with the creation of roads on the island.

An archive photo of a Minga. It is a centuries-old tradition on Chiloe Island. Rodoluca/CC BY-SA 3.0

“Before that time, all the work of the inhabitants of the archipelago of Chile was done by sea, since there were no roads between the villages, therefore all the communities were located by the edge of the ocean. When the roads began to be built in the late 1950s, Chilotes started moving their houses to places where it would be easier to connect them to the roads … thus was created the collective work of the house-moving mingas.”

The need for farmers to gain better access to roads also opened up the possibility of relocating to more fertile ground. For low-income families surviving on the slim and volatile profits of farming or fishing, leaving behind a perfectly good house only to have to invest the time and money in building a new one elsewhere is not the most feasible option. Besides, with a whole community at their disposal to help with the move, who needs to pay general contractor fees?

For many Chilotes, the tradition is also rooted in their spiritual beliefs. Although Chiloé’s main religion is Catholic, the islands are also rich in pre-Christian pagan mythology, involving apparitions such as El Caleuche, a local ghost ship staffed by drowned fishermen. It is also believed that the “collective Chilote spirit” resides within the home, so leaving one’s home for a new one would be to abandon a vital part of their cultural identity. Many Chilotes still believe in the myths, which is why sometimes a minga’s purpose is to move a house away from haunted land.

youtube

The preparations for the minga take several days, with the family first going to their town to ask for assistance and establishing an official date for the move. The house is then prepped for departure, with furniture, windows, and doors either removed or secured in place. Sometimes, the building is reinforced with struts so it doesn’t suffer structural damage en route.

The big day arrives. After the house is blessed for the journey, it is removed from its wooden foundations and hoisted onto tree-trunk rollers. A team of oxen or bulls is hooked up, and the helpers (usually men) drive the oxen forward, with the “minga engineer” overseeing the procession. Men outside the house help direct the oxen and adjust the rollers, while men inside the house spur the oxen forward with sticks and shouts. The minga route is usually lined with other villagers and onlookers cheering them on.

Oxen are hooked up to move the house. Rafael Estefania

Moving a house overland is laborious enough, but water-crossing mingas take things up a notch.

Having been pulled to the beach, the house is deposited below the waterline at low tide to wait for the tide to come in, and buoys are attached to the underside of the structure. As Chilote houses are single-story and wooden, they are generally light enough to be towed across channels without completely submerging. Some houses can also be placed on a small raft to help them float.

Once the tide is in and the house is surrounded by water, it’s hooked up to one or more boats, and is pulled at a steady speed through the water to its destination. The house is then floated as close to shore as possible at low tide, refitted to a new team of oxen, and is pulled back onto the wooden rollers to finish the journey.

It can take several days, but when the minga is finally completed and the house safely returned to dry ground, the community celebrates. Curanto, a clambake-style meal of seafood, meat, and potatoes, is prepared by the family for the workers and community. With music and drink, everyone dances and parties as the house is, once again, blessed.

Dancing after the minga has taken place. Rafael Estefania

“Moving the house is a sensation of joy, of happiness, because we achieve the goal with the whole community,” says Higueras.

Because of their rarity and spectacle, mingas nowadays are a big attraction, drawing tourists and other locals to watch the procession and take part in the afterparty. Some, like Higueras, believe this is a slippery slope.

“The threat is that mingas will become arranged for the expectation of the tourists, without a larger objective than that … mingas should not be an instrument to develop tourism,” she says. “It is a reason to attract tourists to the area and while we do not oppose that, it would be a real shame to have mingas without having the need for their original purpose.”

Boats in Chiloe Island, Chile. Jeff Warren/CC BY-SA 2.0

With plans to finally construct a bridge connecting the island to the mainland, tourism becoming a greater economic force and incentive, and climate change a looming threat to coastal communities, change is in the winds in Chiloé.

But based on Chilotes’ proven adaptability, molding centuries-old traditions to suit modern necessities, whatever comes will be handled hand-in-hand with neighbors and communities. When houses float, anything’s possible.

0 notes

Text

North Korean Officials Had No Idea What Their Hostages Were Signaling

The story of 83 American captives and the “Digit Affair.”

The captured crew of the U.S.S. Pueblo. Bettmann/Getty Images

The men in the photos look a little bored and awkward, maybe uncomfortable or even tense. The more you know about the photos, the more you read into them. But without context, what you see is young men assembled in rows for a formal group photo, staring into the camera or glumly off to the side. It could be a group photo of colleagues or a social club—a hum-drum setup. But stare longer and it’s obvious: In each photo, one or more of them is giving the finger.

All of these men are prisoners, pawns during a politically tense time, and they’re defying their captors in one of the only ways available to them: By flipping the bird.

It was 1968 and the United States was solidly mired in the Cold War, spying on the Soviet Union and its allies and being spied upon in return. The U.S.S. Pueblo was a Navy intelligence ship whose cover was collecting oceanographic data (of the 83 crewmen there were two civilian oceanographers aboard), but its actual duty was collecting intelligence on Russia and North Korea.

On January 23, 1968—just 18 days into its first mission—the Pueblo was approached by a North Korean vessel near the port of Wonsan. The vessel asked them their nationality, and the Pueblo hoisted the American flag. They were told to slow and prepare to be boarded; the Pueblo crew responded that they were 15.8 miles from land, and thus in international waters. But the situation quickly grew dire—three more North Korean boats appeared, and fighter jets flew overhead.

The North Korean ship opened fire on the Pueblo, killing one of the crew and wounding others. The Pueblo was barely armed; rather than fight back they began to frantically burn and dump documents, smashing equipment with axes and hammers. The ship was boarded and the crew taken captive. Bedsheets were cut up into blindfolds; they were tied up, punched, kicked, and prodded with bayonets.

The U.S.S. Pueblo in October 1967. US Navy/Public Domain

“My mother’s prediction that I would die in dirty sheets was about to come true,” wrote one crew member, Stu Russell. “And to make it worse, I had my boots on.”

Soon they were being sped toward North Korea. It was the beginning of what would be a 335-day ordeal. (The crew has written extensively about their experiences, much of it collected on a website maintained by the U.S.S. Pueblo Veterans Association.)

Upon arriving in North Korea, the Pueblo crew was marched past a hostile public to buses with covered windows that ferried them to a train, also with covered windows. The train carried them to Pyongyang, where they were displayed for the waiting press before being taken to the first of two compounds where they would live for nearly a year.

The crew dubbed their first quarters “The Barn.” There they were housed in dim, cold cells, and beaten and tortured routinely by their captors. The men grew malnourished as they ate scant meals of turnips and a foul-smelling fish they derisively called “Sewer Trout.” One man’s shrapnel wounds were treated sans anesthetic; his tonsils would also be removed without pain relief.

Russell recalled a day when he and a few other men were transported to a shed out in the woods where they were told they would take a bath. Thoughts of World War II gas chambers fresh in his mind, Russell tried to come to terms with his impending death. “I had my ticket out of Korea, I was going home,” he wrote, “I could smell the pines and actually taste the cold night air, being alive was great.” Fortunately, the men had actually been taken to a rustic bathhouse.

Crew members of the U.S.S. Pueblo at a press conference in North Korea, after their ship was captured. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph/Public Domain

As the crew suffered, cut off from outside contact, the public panicked. Washington demanded the return of the ship and its crew, North Korea rebuffed such requests, insisting the boat had been in North Korean waters. U.S. officials entreated President Lyndon B. Johnson to deploy the military, if necessary, to retrieve the men. In a television appearance days after the capture, Johnson demurred that “We shall continue to use every means available to find a prompt and a peaceful solution to the problem.” (Behind the scenes, the U.S. government was considering everything from a naval blockade to a nuclear attack.)

The public bristled, they felt the men had been abandoned. The New York Timesdeclared the incident “humiliating” and the The San Diego Union began publishing a daily counter that ticked upward with every day the crew remained in captivity. A group of citizens calling themselves the Remember the Pueblo Committee gave speeches, churned out bumper stickers, and tried to keep the media interested in the captives.

Meanwhile, North Korean officials were launching a media campaign of their own. They filmed and photographed the men for propaganda—even putting them through the bizarre experience of re-enacting their own capture for North Korean cameras, to be distributed as propaganda. They were forced to participate in staged press conferences, where they performed exercise routines before an audience. They were made to sign false confessions and write letters to family declaring their support for North Korea.

Occasionally, the men were the audience. One day in June, the group was assembled to watch propaganda films. One was about the North Korean soccer team’s visit to London, another about the body of a U.S. soldier being returned to officials. In both films, something extraordinary happened: Someone flipped the cameraman off. In both instances, it seemed clear that the gesture didn’t translate; their captors didn’t realize that they were being insulted, and so the action was not edited out of the reels.

The crew of the U.S.S. Pueblo in January 1969, taken shortly after their arrival on the grounds of the Balboa Naval Hospital in San Diego. US Navy/PublicDomain

So began The Digit Affair.

“The finger became an integral part of our anti-propaganda campaign,” wrote Russell. “Any time a camera appeared, so did the fingers.”

You see it in a shot of three bored looking men, two of them casually propping their heads up by clearly extended middle fingers. In a group shot of the men seated in two rows, as if for a school photo, a man in the front looks directly into the camera, his hands folded in his lap, and his top middle finger popped out. In another, a fellow looks like he’s chewing his fingernail—on his middle finger.

If their captors ever noticed the gesture, they had a story prepared: It was a “Hawaiian Good Luck sign,” a cousin of the “Hang Loose” sign, comprised of thumb and pinky extended.

This wasn’t the only way the crew defied their captors. In fact it was just one of several methods they had for coping with their plight through jokes. The finger was part of a larger campaign that included embedding in-jokes in forced confessions and letters home, giving their captors mocking nicknames, and even a bawdy poem.

“It could be considered pretty sick humor,” said crewmember Bob Chicca in a Westword story detailing the way the Pueblo men launched a laughter offense. “It helped us survive and kept morale up. For that little period of time, we were in charge of our own lives.”

The U.S.S. Pueblo, on display in Pyongyang, North Korea. Nicor/CC BY-SA 3.0

The triumphant reign of the Hawaiian Good Luck sign came to an abrupt end when Time magazine published a photo of the men and pointed out their ruse, writing in the caption that “three of the crewmen have managed to use the medium for a message, furtively getting off the U.S. hand signal of obscene derisiveness and contempt.”

When the crew’s captors read this, they kicked off what the men would come to call “Hell Week,” beating the crewmen mercilessly for days. During this especially bleak period, the men had no way to know they were actually close to going home.

On December 23, 1968, U.S. officials finally agreed to sign a “confession” declaring that the Pueblo had trespassed in North Korean waters, although they did so only after formally stating that they didn’t believe in the statement they were signing. Satisfied, North Korea released the prisoners, who arrived back in the states on Christmas Eve.

The crew’s relief from their ordeal was brief. A weeks-long Naval inquiry was held to investigate charges that the men had surrendered without a fight and failed to destroy classified documents aboard the Pueblo. Crewmen wept during the inquiry as they testified about the abuses suffered while held captive. Finally, the navy dismissed the case. Crew members were eventually awarded medals, including 10 men who received the Purple Heart.

One thing that did not return with the crew was the U.S.S. Pueblo. It still resides in North Korea, where it’s a tourist attraction at the Victorious War Museum in Pyongyang.

0 notes

Text

Why Does the Season Before Winter Have Two Names?

A look at the history of fall and autumn.

Usage of the word “fall” first appeared in England in the mid-16th century; “autumn” pre-dates it to sometime in the late 14th century. Autumn Mott/Public Domain

There is indecision about the season that comes before winter. The plants all die, or seem to, but at the same time are at their most magnificent: they produce more fruit, turn vibrant colors. We are relieved at the end of a hot summer, and terrified of the long winter ahead. (At least those of us with seasonal affective disorder.) We cram in holidays to both celebrate these brief few weeks and also mourn the green times behind us. And we don’t even know what to call this weird time: is it autumn or fall? Why does this season have two names?

The understanding of seasons varies dramatically based on where you’re located geographically, coupled with, if applicable, which country colonized your country. In the temperate zones, the seasons are generally split up into four; in tropical zones, usually two; in South Asia, usually six. Older calendars may have five or ten or more or fewer. Countries like the US, which span multiple zones, run the gamut. The United States sticks to four seasons, even in parts of the country like South Florida and most of the Southwest, which really only have a wet season and a dry season.

London in the autumn. (Or, if you prefer, fall.) Robin Wylie/CC BY 2.0

The etymological roots of the English words for the seasons—summer, winter, spring, and autumn/fall—are all weird and fun in their own ways. As some of the most basic concepts language is required to describe, the words for the seasons are extremely old. “Over the centuries, these names change, rather dramatically sometimes, and also from community to community,” says Anatoly Liberman, a historical linguist who has written on the subject for the Oxford University Press. “Summer” originally dates back to the Proto-Indo-European root sem, which meant “half,” and possibly suggests that, in Europe, there were originally only two seasons. From Proto-Indo-European (the root of all major European languages) that root transformed into an array of similar words: sumor, sumar, somer, that kind of thing.

Winter similarly dates from Proto-Indo-European, this time from wed, which meant water, wet, or rainy. It splintered outwards from there; the English “winter” comes from the Proto-Germanic wintruz. My point with these is to note that the two extreme seasons, winter and summer, are very, very old words. The other two seasons? Not so much.

Sandro Botticelli’s 15th-century painting La Primavera, or Spring. Public Domain

Until around the 16th century, the English language did not really have distinct words for either spring or fall. A survey of language used to describe springtime in Early Modern English, from the 14th to the 16th centuries, shows a whole bunch of terms: vere, primetide, and especially lenten. “This variety of terms suggests that ‘spring’ was not fully lexicalized in the language; ‘spring’ was relatively peripheral compared to winter and summer,” writes Earl R. Anderson in his book Folk Taxonomies in Early English. Same thing for fall: it was sometimes described as the time for harvest, but “harvest” was not the name of the season; it was just what you did during the late summer or early winter.

Fall was, in fact, the very last of the four seasons to become codified with a name, or even the designation as a season on par with the others. There are mentions of winter, summer, and spring in manuscripts dating back to the 12th century; the name of spring may not have been settled upon, but the idea that it was a full season came much earlier than with fall.

The word “autumn” has French roots; in modern French the word is automne. It certainly has Latin roots, coming from the word autumnus, which in turn comes from…somewhere. These etymologies are all guesswork: there was no day when everyone stopped using one and started using another, with a nice paper trail to verify it, so this is all just assumptions based on plausibly similar older words and meanings. Liberman is not particularly wowed by any of the possible origins of autumnus.

The Corn Harvest, by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Public Domain

Autumn shows up in English first around the late 14th and early 15th centuries, though it coexisted with “harvest” as a loose description of the season for another 200 years.

Fall is different. It first shows up in the mid-16th century in England, primarily at first as “the fall of the leaf,” which was shortened to just “fall.” Like “harvest,” it is descriptive, but more evocative; not just a term coming from the most important action taking place during this time period, but a more poetic observation of what makes this season different. (The etymology of “fall” is not that interesting. You can trace it back to Middle English, Old English, Proto-Germanic, and then Proto-Indo-European, but in each era it basically looked like “fall” and meant “fall.”)

The recognition of fall/autumn as a distinct season started happening in England right around the time that the American colonies began to separate linguistically from British English. By the 17th century, with American colonies already established, more calls for what was called “spelling reform” began. Ever since the Norman conquest, English had been littered with scraps of French, and it was around this time that prominent writers like James Howell began to agitate for sensible wholesale changes to English. These changes were primarily in spelling—logique to logic, for example—but others took things further.

Fallen autumn leaves. Anthony Rossbach/Public Domain

Noah Webster, of Webster’s Dictionary, was an ardent spelling reformer, but while his work was couched in doing the sensible, logical thing, his motivations were also political. He was primarily responsible for making changes to American English spelling in words like “center” (not “centre”) and “color” (not “colour”). Webster’s work was widely adopted, which goes to show that around the time of independence, the American colonies were absolutely ready to change the way they spoke and wrote as a means to differentiate themselves from the imperialist British. By the mid-19th century, “fall” was used more often in the U.S., and “autumn” more often in Britain.

In a 1908 essay that somewhat snootily examines Americanisms, H.W. Fowler admitted that “fall” is a far superior term to “autumn,” but that “fall” is now distinctly American. Here is a very good paragraph from that essay:

In the details of divergence, they have sometimes had the better of us. Fall is better on the merits than autumn, in every way: it is short, Saxon (like the other three season names), picturesque; it reveals its derivation to every one who uses it, not to the scholar only, like autumn; and we once had as good a right to it as the Americans; but we have chosen to let the right lapse, and to use the word now is no better than larceny.

But because autumn and fall became the go-to name of the newly crowned season at around the same time, both terms are used in both the U.K. and the United States. To an American, “fall” is the more common word, with “autumn” easily understood but not the norm. In the U.K., the opposite is true.

0 notes

Text

The Plan to Prove Microdosing Makes You Smarter

Amanda Feilding has been working towards this goal for half a century.

For years now, trendy Silicon Valley bros have been sustaining a slight buzz by microdosing, claiming a few potent hits of LSD can supercharge a workday.

Until now, there hasn’t been much in the way of science to back it up, but Amanda Feilding hopes to change that.

Feilding is founder of the Beckley Foundation and a leading researcher in the field of psychedelics and consciousness. She’s got a plan to prove that microdosing LSD makes you a better problem solver. She’s throwing the established protocols for evaluating cognition and creativity out the window in favor of a much more straightforward objective: How do test subjects fare when playing the ancient Chinese game of Go?

It’s a protocol imagined from her experiences among friends as students of physiology and psychology more than 50 years ago. “We were working very, very hard,” she tells Inverse. “And as recreation in the evenings, we used to play the ancient Chinese game of Go. I found that I won more games if I was on LSD, against an opponent I knew well. And that showed me that, actually, my problem-solving, my creative thinking, was enhanced while on LSD.”

vimeo

Microdosing is the phenomenon of taking small, controlled doses of psychedelic drugs — usually just 1/20 to 1/10 of the sort of dose you would take to go on a magical hallucinatory trip. LSD is frequently the drug of choice, but psilocybin (magic mushrooms) and mescaline (peyote) are also in use. The idea is that the dose is too small to produce noticeable effects of being high but big enough to change your thought patterns and behaviors. If it works like it’s supposed to, you just function a little better than normal — happier, more productive, less full of worry. At its best, you have “A Really Good Day,” as Ayelet Waldman puts it in her recent book of that name.

The best evidence collected to date on the effects of microdosing comes from James Fadiman, a researcher with Sofia University. He’s received thousands of self-reports of people’s experiences microdosing and has recently begun collecting and analyzing more rigidly with his research partner, Sophia Korb. They presented early results of that work at Psychedelic Science 2017 in April. People reported less depression, less procrastination, more energy, and more creative thinking.

Fadiman denies the results are some incredible placebo effect, saying the proof is in the unexpected results seen across individuals who’ve never met. But drug regulators in the United States and around the world won’t take him or his study participants at their word; they require rigorous, repeatable, controlled research.

youtube

Feilding’s study, to be run through the Beckley/Imperial Research Programme, is designed to have 20 participants take a dose of LSD at 10, 20, and 50 micrograms (a typical recreational dose is 100 micrograms) and also a placebo. Each time they will complete questionnaires on their mood and other vectors, will undergo brain scans, and will play Go against a computer.

Go is a complex game, because the number of possible moves on a given turn is so large. Even the world’s fastest computers couldn’t calculate the consequences of all the possibilities, which is why beating humans at Go was such a lauded featin the world of artificial intelligence. The best moves in the five-game standoff between Google’s AlphaGo and human Go champion Lee Sedol weren’t the ones that followed the usual script, they were the ones that were so far outside of the box that no one — especially the opponent — would ever have predicted or even considered them.

“The tests of creativity, which are current, like Torrance Test, they don’t really test for creativity. They test more for intelligence, or word recognition, or whatever,” says Feilding. “They can’t test those ‘aha’ moments in putting new insights together, whereas the Go game does test for that. You suddenly see, ‘Aha! That’s the right move to enclose the space.’”

youtube

It would be a remarkable feat if Feilding can show that microdoses of LSD do indeed enhance our ability to tackle complex problems — that would be astounding. These days, it seems everyone’s looking for the magic pill to kick human brains into high gear, but a lot of promising research has come up short. The massive brain training industry, for example, has largely failed to demonstrate that its computer games, designed specifically to boost cognition, do much besides improve your skill at playing those video games.

The immediate hurdle is money. LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline aren’t patentable, which means there’s almost no incentive for pharmaceutical companies to invest in expensive clinical research trials.

Advocates have turned to philanthropy and crowdsourcing to fill the gap. A group called Fundamental is currently raising money for Feilding’s project, along with others investigating the potential of psychedelics to boost mental health. If funding comes through, the next step will be to go through ethics approvals before beginning the trials.

In the meantime, Feilding plans to clear up some of the debate over what is, and isn’t, a placebo effect. She’ll have people dose themselves and write about their experience, much like in Fadiman’s study, but the protocol will be set up so that participants could either be taking a placebo or a microdose, and they don’t know which.

The gold standard of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, large-scale trials is still a distant, expensive dream for the psychedelic activists. In the meantime, a wealth of anecdotal evidence suggests that microdosing works for a lot of people and is safe. It’s enough to convince thousands of people to try, whether it’s proven by science or not.

0 notes

Text

The Bamboo Flutes of Japan’s ‘Monks of Emptiness’

The basket-masked komusō monks used music to meditate and created a distinctive art form.

A parade of modern komusō reenactors, 松岡明芳/CC BY-SA 3.0

Those familiar with japanese history or culture might have seen some version of a komusō, or “priest of nothingness.” Instantly recognizable (and simultaneously unrecognizable) thanks to the woven baskets that they wear over their heads and the long flutes that protrude from beneath them, these Buddhist monks were unique for a number of obvious reasons. But it’s their haunting meditation melodies that may be their most enduring legacy.

The komusō, also sometimes translated as “monks of emptiness” or something similar, came to prominence around the 17th century in Japan, and formed a new class of itinerant monks, of the Fuke sect of Japanese Zen Buddhism.

They became known for their long bamboo flutes, called shakuhachi. The komusō, which only allowed in men of the samurai or ronin class, used the shakuhachi as a religious instrument, in contrast to the quietude or recited mantras that other sects used in meditation. The Fuke sect monks instead played compositions known as honkyoku to focus their minds toward enlightenment; they called it suizen, or “blowing zen.” According to the dictates of the sect, the shakuhachi was to be played only for meditation or for alms, and never with other instruments, so that listeners can focus solely on the sound of the flute. The resulting compositions are spare and haunting pieces of tonal music.

A bamboo shakuhachi flute. Akihito Fujii/CC BY-SA 2.0

The komusō also adopted their distinctive woven wicker hat or mask, called a tengai, that looks like an overturned basket with slits for the monks to see out of. Wearing one traditionally symbolized a dismissal of ego or self, though the masks also hid the identity of the wearer. Many of the komusō were ronin, or wandering samurai, looking to start a new life with the anonymity the attire provided.

From the time they banded together as the Fuke sect in the 1700s, the komusō had been given extraordinary special privileges by the ruling powers. The shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu supposedly passed a decree in the early 17th century that allowed komusō unrestricted travel in feudal Japan, when free movement across borders was highly restricted. Although this decree was most certainly forged, it was respected and added to for years.

youtube

One addition to the decree granted the monks exclusive use of the shakuhachi, which made the flute a powerful passport and status symbol. By the early 1700s some komusō began teaching laymen to play—for a fee—which opened the door for new styles of secular shakuhachi music to emerge, and dampened the novelty of the komusō over the next century.

The anonymity and freedom provided by the tengai also meant that outlaws, spies, and thugs eventually traveled under the guise of a komusō (those long bamboo flutes doubled as great clubs). This eventually made the public suspicious of anyone wearing the woven masks, and some towns banned the traveling performers altogether.

By the time that Buddhism came under attack in Japan in the 1870s, the komusō were already on the wane. And when the Fuke sect was outlawed at this time, playing the shakuhachi became a purely secular endeavor.

Their musical tradition survives today, through reenactments and shakuhachi performances. Most of the specific original compositions that still exist survive thanks to komusō Kinko Kurosawa, who composed and collected some 36 honkyoku in the early 1700s. These compositions form the basis of a type of shakuhachi performance known as the Kinko Ryū, which epitomizes the sound of period komusō flute.

Today, there are a number of surviving shakuhachi disciplines, and the indelible image of the basket-headed komusō can be found popping in popular culture, from anime to film. But while their bizarre look is hard to forget, the influence of their signature flutes is truly worth remembering.

0 notes

Text

The Revolution Was Televised, Thanks to This 25-Pound Video Rig

In the 1970s, the Portapak gave a voice to outsiders and changed media forever.

A 1970s Portapak. Affordable and portable video made it possible to democratize television. SANDRA 79/CC BY-SA 4.0

New York in 1975 was the kind of place punk-music-loving kids could really fall in love with. Patti Smith at Max’s. The Ramones at CBGB. A burgeoning culture was forming right before their eyes. There was art in the air. Raw energy, waiting to explode. This didn’t go without notice to a group of students and filmmakers working at Manhattan Cable Television’s public access department. This music-and-film-loving group knew that the punk scene was where they needed to be pointing their cameras.

“We had all this equipment lying around,” says Patricia Ivers, a former intern in the department. “We [needed to] do something with it, and [this music] was so significant.” There was an unsigned band festival coming up at CBGB and the group talked Hilly Krystal, the club’s owner, into letting them bring their equipment in to record the bands. The group, as members of the video collective Metropolis Video, went on to capture early performances from some of punk’s and new wave’s biggest bands. This also put them in the middle of a growing movement in media-making, television, and technology.

Metropolis Video member Patricia Ivers recording with a Portapak at CBGB. Edythe Brownstein/Used with permission

The department was equipped with Manhattan Cable’s Portapaks—portable, handheld cameras and recorders that used videotape, rather than film—which let them shoot and edit all with one piece of equipment. Sony had introduced the camera in 1967, giving consumers access to portable video equipment for the very first time. “This was bleeding-edge technology,” Ivers recalls. Before the invention of the Portapak, merging images with sound was a much more involved process. As the media historian and curator Deirdre Boyle explains, “At that point sound and image were disconnected. Once the film was processed you had to sync the sound, but with video you had it all at once. It was immediate. You could shoot it and play it right back. The people you shot could see it right away. You couldn’t do that with film.”

Freed from the constraints of bulky tripods and heavy studio cameras, these new, lighter cameras also put the members of Metropolis Video close to their subjects, in a way that hadn’t been possible before. That first night with the Portapaks at CBGB, Metropolis filmed the Talking Heads, Blondie, and The Heartbreakers—a new band formed by ex-Television guitarist Richard Hell and ex–New York Dolls guitarist Johnny Thunders. All of them were unsigned and poised to change the landscape of popular music. “It was exhilarating,” Metropolis’s Steve Lawrence says. “We were liberated as artists, and we wouldn’t have been engaged in the same way with our heavier equipment.”

“You could see a person’s face as you shot. We kept eye contact,” says Tom Zafian, another Metropolis member. “We were really close to the musicians, trying to get a new, intimate feel. We were part of the whole thing.”

Metropolis Video, and other groups like them, were part of a much bigger change in media-making in general. Television production was no longer just in the hands of corporations—it belonged to the people. Students, activists, and radical new media-makers were pushing the boundaries of broadcasting, and the emerging portable video technology of the time was making it possible in a way it had never been before.

At 25 pounds (the camera plus the recorder) and priced at around $1,500, the Portapak was lighter and cheaper than anything available before it. This meant it was possible for small producers, such as public access operations, to own one or more of them. Though heavy by today’s standards, its offered a portability that was essential to capturing communities on the margins. Crucially, it also allowed for what had been impossible before: live shooting and editing, right on the scene. “This was battlefield recording,” Zafian says. “You had to concentrate, mix your ass off, and see what happened.” The cameras could be hooked up to portable switchers and monitors, so whoever was serving as director on a shoot could switch between cameras. The director could also fade in and out between shots and cameras to create the visual experience she wanted. This was the TV studio reborn in the wild.

“We were really close to the musicians, trying to get a new, intimate feel. We were part of the whole thing.” Edythe Brownstein/Used with permission

Metropolis’s earliest recordings went back to Manhattan Cable and were shown as a three-part series, Rock From CBGB’s. (“Seen Saturday nights at midnight on Manhattan Cable’s Channel D,” announced a New York Times listing from 1975.) These portable cameras weren’t just making it possible to capture the rise of an underground music scene. They were something far bigger, Zafian explains. “Public access was for the people. It was the democratization of television.”

Still, it was a weird, outside medium, perfect for weirdos and outsiders.

The Portapak revolution meant that, during a tumultuous social and political time, those who were out of the mainstream—placed there by the established order, or proudly occupying the fringes—could have their voices heard on-air. “Everyone who cared was on the margins, you didn’t want to be mainstream.” Boyle says. “Most people picking up a Portapak had grown up watching network television, and [the Portapak] gave us the tools to make something uniquely our own, not tailored to the whim of the monolithic TV channels. Suddenly people had the tools to challenge TV on their own terms, showing what could be done on their own.” It also meant that video and activism became intertwined. John Hazard, another Metropolis member agrees, “There was this feeling, sort of like self-publishing, a sense of counterculture.”

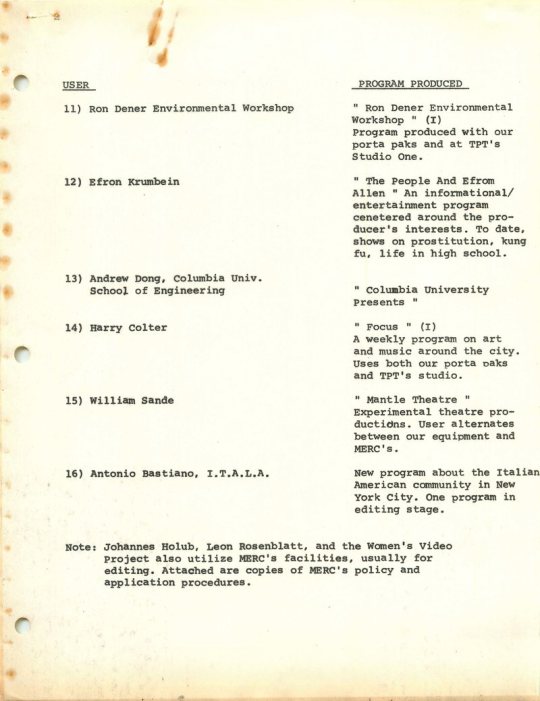

Portable video freed alternative media-makers. This is a list of some of the public access programs aired on Manhattan Cable Television in 1974. Steven Laurence/Used with permission

These radical media-makers didn’t, and maybe couldn’t, find a home on more traditional stations. “[Traditional] TV considered it sub-par,” says member Michael Owen. “And the film people had no way to project it. It was ‘bastard tech,’ and not embraced.” In addition to broadcasting, Manhattan Cable also taught anyone who wanted to learn how to operate the equipment. Along with several other video collectives and organizations of the era, Manhattan Cable can be credited with changing the way people thought about TV and media in general. The New York video collectives Raindance and Videofreex were looking at video as a means of social change, and across the country, San Francisco’s Video Free America was advancing the field of video art. Portable video freed not just the means of production, but the means of broadcasting. “All of a sudden, you could make TV by yourself, says Zafian. “It was YouTube without the internet.”

0 notes

Text

Neon Nights: Cinematic Scenes of Nocturnal New York

Daniel Soares has crafted a series of late-night snapshots that distil the city's unmistakable energy.

Daniel Soares headed out to Manhattan’s Chinatown one night and just started shooting aimlessly, not knowing where it would lead.

But over the course of many late night walks through New York’s quietest side-streets, the filmmaker and photographer found himself drawn to the similar scenes of stillness: moments where the madness would settle down and the city seemed to breathe again.

“I love New York – it has so much energy – but sometimes that same energy can be overwhelming,” says Daniel, who’s Portuguese but born and raised in Germany.

“Walking around at night is so special because it tunes out a little bit of its grittiness; you hear less honking and people screaming.”

Daniel likes to drift as far as Brooklyn and Queens, sometimes for just an hour, sometimes until the sun comes up.

What interests him mosts are the solitary figures heading out for a pack of cigarettes or going to the movies alone. The photographer likes to imagine backstories for them – a hobby that lets him reset mentally.

“I really try to give myself idle time where I just wander off exploring new things, travelling, experimenting with different techniques; where I try to shut off from all the stress of the day-to-day,” he says. “Those are the moments when interesting stuff happens from a creative point of view: when you let go.”

New York is the perfect place to do that, he says, since you can point a camera at people and no one will care.

But when Daniel tried extending the project (titled Neon Nights) to Virginia one night, shooting a bodega, it drew immediate suspicion.

“The owner came out, wanted to pick a fight and call the cops,” he says. “I explained to him that this was an art project and, after a little while, he understood… I guess. But I still felt a little bit like a creep.”

Daniel started out in photography by taking regular holidays snaps but, as he got more into graphic design, he began thinking about visual expression differently.

He gradually trained his eye, developing a signature style (and a sense of patience) before becoming a freelance art director who can balance filmmaking and photography.

“You must do it for the pleasure of it,” he says. “A lot of times we start something for the end result: recognition, fame. That should never be what makes you take it up in the first place. You have to cherish the process, with all its ups and downs.”

The key to doing that, he says, is learning to enjoy your own company: to be comfortable in any situation – especially boredom – while discovering your strengths and weaknesses.

“What are the movies, pictures, stories that only you can tell?” he says. “It has to be the type of work that, if you didn’t exist, the world would never see. That’s what I aim for, rather than success.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Search for the World’s Most Enchanting Greenhouses

Two plant-obsessed photographers are on a mission.

The Eden Project, Rainforest Biome, Saint Austell, England. Magnus Edmondson and India Hobson/Haarkon

Magnus Edmondson and India Hobson’s greenhouse quest began in Oxford, England, at the Botanic Garden, on a Sunday morning. “We were the only people there, and it was so incredibly quiet,” they write. The only sounds were “gasps of wonderment” and the “occasional sigh.” From there, Edmondson and Hobson, photographers based in Sheffield, were hooked. They began what they call “a self-initiated Greenhouse Tour of the World”—they find, explore, and photograph greenhouses, potting sheds, polytunnels, conservatories, and other indoor spaces made by humans, for plants.

For their photography company, Haarkon, Edmondson and Hobson were already traveling far and wide. Now they make it a point to seek out greenhouses on their travels and in their spare time. They might be found at the private greenhouse of an orchid grower or Belgium’s Botanic Garden Meise. Most recently they have been exploring California conservatories, the New York Botanical Garden, and the Gardens by the Bay in Singapore. They told Atlas Obscura what drives them to seek out these green spaces, where the world we usually think of as “outside” is contained within clear walls.

A sign led the photographers to this cactus nursery in North Yorkshire, England. Magnus Edmondson and India Hobson/Haarkon

What are the most surprising, hidden, or out-of-the-way greenhouses you’ve visited?

The hidden ones which are the most memorable usually belong to a private owner who has a passion for growing a particular plant. Their love for what they are doing just shines through, and it’s reflected in the care and attention they give to their plants and the buildings they’re housed in.

One that always sticks out for us is a guy in North Yorkshire with a small sign outside his long drive with the words “Cacti For Sale” written on it. We pulled down his drive on a wet winter morning and checked out his impressive cactus collection.

The Oxford Botanic Garden inspired the photographers to visit more greenhouses. Magnus Edmondson and India Hobson/Haarkon

Which have been the most flat-out wonderful—the ones you keep telling people about? What made them so amazing?

Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh is always a place which we mention whenever anybody asks us about a good glasshouse to visit; there is so much variety in the houses they have, which have been added to and adapted over the decades. It also helps that Edinburgh is one of our favorite cities in the United Kingdom to visit.

If you’re up for traveling somewhere a little more exotic, we recently visited the Cloud Forest at Gardens by the Bay in Singapore, it’s one of the best things we’ve experienced on our whole tour. The scale of the environment they have created and the journey you make through the conservatory is brilliant and well thought-out. It’s also a great escape from the heat of the city.

The Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh in Scotland is a favorite of the photographers. Magnus Edmondson and India Hobson/Haarkon

How do you find and choose the greenhouses you visit? Has your strategy changed as you’ve visited more of them?

We have the internet to thank for most of the places we find and visit. It involves lots of searching through Google and Instagram to get a glimpse of greenhouses hiding all over the world. We have learned that it’s worth making the journey on a hunch that there may be a great greenhouse to be discovered. We’ve been disappointed a few times after a long journey, but the gems we’ve found by just going for it far outweigh any less-than-successful trips.

How did you start this love affair with plants? What attracts you to them?

We started with just a couple in our house, we didn’t have a garden and so wanted to have something green indoors. Over the years our collection has built up as we found out what types of plants like to live with us and our lifestyle.

At Calke Abbey in Derbyshire, England, there are “mysterious tunnels” and “an almost-forgotten orangery.” Magnus Edmondson and India Hobson/Haarkon

Are there particular challenges or joys in creating these photos that differ from your other work?

Essentially the website and Instagram is our version of a photo album or scrapbook—it’s where we keep all of our holiday photos and all of the things that we’ve seen and liked so that we can refer to it in the future. We’re lucky because we’ve been given opportunities to travel to places we might not have thought of, and we find ourselves experiencing new things all the time. Documenting it is just part of the fun. A huge part of the enjoyment of what we do is that we get to do it all together and share it, so it becomes less work and more just a very fluid, odd, but interesting lifestyle!

Malaga Botanical Garden (Jardin Botanico de la Concepcion), Spain Magnus Edmondson and India Hobson/Haarkon

How far out of your way are you willing to go for a good greenhouse?

We have just arrived back from a week-long trip to Australia, searching out green places in the cities in the southeast of the country, so I guess we’d pretty much go anywhere. We have a long way to go before we start running out of places to visit.

0 notes

Text

Scientists Have Figured Out What Makes Wagyu Beef Smell So Delicious

One of the key molecules smells like egg whites.

Slices of wagyu rib meat. Schellack/CC by 3.0

Wagyu beef is considered by many to be the paragon of meat. The beef from four breeds of Japanese cattle is famous for its beautifully marbled fat, soft texture, and sweet aroma, which some say is reminiscent of coconut or fruit. But what makes it smell that way? A recent study, published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, found that a cocktail of molecules is responsible, including one that recalls the scent of egg whites.

Scientists have tried to determine the chemical composition of the wagyu beef odor before, but their “sample preparation did not use the optimal cooking temperature,” write the study authors—which seems like a painful disservice to the notoriously expensive steaks. The authors, scientists at Ogawa and Company, a Japanese flavor and fragrance chemical firm, were meticulous in their preparation of three kinds of beef in the study—wagyu from Matsusuka, alongside grass-fed from Australia and a sirloin from the United States, for comparison. They used sous vide, which cooks the steaks in temperature-controlled water bath. The cooked meat was then blended and subjected to a solvent that helped separate out the volatile molecules responsible for the aroma.

youtube

Chef Michael Mina shows us what $9,000 worth of Wagyu beef looks like.

Out of those slurries, the researchers found about 20 different odor-related molecules, including 10 compounds that hadn’t been associated with the smell of beef before. Eight of those are molecules that “have fatty, green, juicy odors,” write the authors. Another compound, which “had a unique egg-white note” that’s also found in chicken, is likely a big contributor to the wagyu bouquet. It is the relative proportions of these aromatic compounds that make the Japanese variety so distinctive. “The many kinds of potent odorants in each beef aroma are common,” the food scientists write, “however, the balance of their contributions is different from each other.”

0 notes

Text

How Cosmic Rays Revealed a New, Mysterious Void Inside the Great Pyramid

This tantalizing finding raises more questions than it answers.

It’s not ancient aliens. ScanPyramids

Today, the journal Nature has published a finding that sounds like the setup to a Nicholas Cage movie. A team of physicists and engineers has discovered a previously unknown “void” in the Great Pyramid at Giza in Egypt. And they did it with the help of cosmic rays created at the edge of space.

The “ScanPyramids Big Void,” as scientists are calling it, is around 98 feet long, and about 50 feet high. The investigators don’t know what’s inside this void. They also don’t know what its purpose is. Nor do they have any way to currently access it.

But it’s a huge finding. “No very big structure has not been discovered inside the Khufu pyramid since the Middle Ages,” Mehdi Tayoubi, co-founder of the nonprofit that led the research, told reporters Wednesday.

The Great Pyramid, also known as Khufu’s pyramid, was built around 2560 BC to ensure the immortality of the Pharaoh Khufu after his death. The pyramid is one of the wonders of the ancient world, and it’s one of three at the site at Giza (along with the Great Sphinx).

Khufu wasn’t just a king — he was thought to be a god. And so his death commanded something spectacular. At 455 feet, his pyramid stood as the world’s tallest man-made building until the year 1300. That’s 3,800 years. The pyramid was about as old to the ancient Romans as the Romans are to us. And throughout the rise and fall of civilizations, the pyramids have remained a fascination. Even today, they still contain mysteries. Like the newly identified void.

But archaeologists say that while it’s still hard to say how archaeologically significant the void is, it’s likely an intentional design element.

“When you’re dealing with creating a monument to house the immortal remains of an individual who bridges heaven and Earth, and whose ascendance to the stars helps assure the perpetual prosperity of Egypt, I don’t think [this void] was a cost-cutting measure,” Adam Maskevich, an archaeologist who was not an author on the paper, explains. (The New York Times explains the void could have been an engineering necessity to lessen the weight of the structure.)

And scientists suspect it’s there because of cosmic rays.

How cosmic rays found the void?

An illustration depicts where the research team thinks the void is located in the pyramid. ScanPyramids Mission

For two years, the ScanPyramids project, a collaboration between the Heritage Innovation Preservation project in Egypt, Cairo University, and the Egyptian government, has been using advanced techniques from the world of particle physics to learn more about the pyramids.

“Just because a mystery is 4,500 years old doesn’t mean it can’t be solved,” the ScanPyramids project explains.

Subtle techniques from physics are particularly helpful for exploring priceless ancient treasures like pyramids. You can’t knock out walls in the pursuit of a new discovery. So the ScanPyramids team takes a nondestructive approach.

Here’s the simplest way to describe what they did: It’s like they took an X-ray of the structure with cosmic rays.

Recall that when you go for an X-ray, radiation passes through your body. But this radiation gets partially stopped by the denser parts of your body (i.e., bones), while the soft tissue lets most of them pass on through. The X-ray machine is essentially picking up on the shadow of X-rays cast by your bones.

With the pyramid scan, the scientists didn’t use X-rays, but cosmic rays. These are sprays of high-energy subatomic particles that shower us every day.

Kyle Cranmer, a particle physicist at New York University, explains how cosmic rays form. It starts with huge energetic events like exploding stars. These events shoot jets of atomic nuclei across the universe at speeds nearing the speed of light. When these high-energy particles reach Earth, they slam into our atmosphere like shotgun pellets. “They’ll hit the nuclei of other atoms” in our atmosphere, Cranmer says.

When those atomic nuclei from space hit those atoms in our atmosphere at near the speed of light, they burst open, spilling out the subatomic particles that make up all the matter in the universe: electrons, positrons, neutrinos, muons, and so on. (This is exactly what scientists try to replicate with particle accelerators like the Large Hadron Collider.)

Some of these particles are very short-lived: They fall apart in a fraction of a second. But muons — which are a heavy version of the electron — are heavy and stable enough to reach the ground.

“They [muons] are going through us right now — thousands going through us every second,” Cranmer says. (You can actually build your own cosmic ray detector at home, and it really doesn’t seem all that hard. Even your smartphone can be turned into a cosmic ray detector.)

TelescopeArray.org

Those muons rocket down to Earth at 98 percent the speed of light — so fast they experience the time dilation predicted by Einstein’s theory of special relativity. They’re supposed to decay in just 2 microseconds, which would mean they’d barely get 2,000 feet down from the top of the atmosphere before dying. But because they’re moving so fast, relative to us, they age much more slowly. (A similar thing happens to Matthew McConaughey’s character in Interstellar.)

When they hit objects on the ground, they act exactly like X-rays. Dense objects absorb them, less dense objects let them pass through. The ScanPyramids team used photographic plates sensitive to muons. These photographic plates were placed inside the already-explored chambers of the pyramid and around the outside of the structure. The data from each plate was then combined to make a map of the void.

A muon detector set up outside the Great Pyramid. ScanPyramids

And the researchers found that the muon-pattern observed in these photographic plates looked a lot like the pattern of muons from the pyramid’s grand gallery. That makes them confident that what they are observing is truly an empty space and not just a region of less-dense rock.

The team previously had success using these techniques to map the (already known) internal structure of the Bent Pyramid, a smaller pyramid in Egypt. No new voids were found on that investigation.

Okay, so what might be the purpose of this void?

The Great Pyramid is a wonder of the ancient world built around 2400 BC; experts still don’t know exactly how it was constructed. The void is completely sealed off from the known passageways in the pyramid. There’s no way to currently get to it. And so Nature’s finding opens more questions than it provides answers.

“This is an exciting new discovery, and potentially a major contribution to our knowledge about the Great Pyramid,” Peter Manuelian, a Harvard Egyptologist not involved in the research, says in an email.

A new chamber could provide clues to how the pyramid was constructed. Or more tantalizingly: It could contain treasure. The Great Pyramid was ransacked and looted millennia ago. This void could represent the last untouched portion of the structure.

The research team setting up an augmented reality review of the Big Void. ScanPyramids Mission

But it’s too soon to say any of this. “Most people want to know about hidden chambers, grave goods, and the missing mummy of King Khufu. None of that is on the table at this point,” Manuelian says.

The ScanPyramids team currently has no concrete plan to get inside the void. And they have to do much more work to pinpoint its location in the pyramid. The muons only give a blurry, rough sketch.

“For the time being we cannot allow ourselves [to start drilling bore holes into the void],” says Hany Helal, vice president of the Heritage Innovation Preservation Institute, which runs the ScanPyramid project. “We need to continue the research with nondestructive techniques, which will allow us to have a complete picture of what is inside.”

Once there’s consensus on the exact dimensions of the void and its location, then a team can drill a small hole, and deploy a robot drone to explore it.

“We can’t allow for trial and error,” Helal says.

After all, this is the most famous building on Earth.

0 notes

Text

The Perils and Pleasures of Bartending in Antarctica

At the South Pole, the freezer is just a hole in the wall to the ice outside.

A cosy sight: the entrance to the geodesic dome where the Club 90 South bar was originally located. NOAA/ CC BY 2.0

When Philip Broughton boarded a flight to the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station in 2002, he didn’t intend to become an Antarctic bartender. Following a terrible day at work, he had decided to get away, and, after a Google search and a two-year application process, he found himself on an American research station in Antarctica, working as a cryogenics and science technician for a year and a day.

A few weeks after his arrival in the summer of 2002, Broughton walked into the local watering hole, Club 90 South. “The only seat left was the one behind the bar,” Broughton says of his initiation into the pantheon of South Pole bartenders.

Broughton sat behind the bar and put his feet up against the beer case. Inevitably, someone asked for a beer. Glaring, Broughton handed one over. “Don’t get used to that,” he said.

But then someone asked if he knew how to mix anything. Which, thanks to a Playboy cocktail guide, he did. Using his own stash of Angostura bitters, he whipped up a Manhattan.

“And there I stayed for the rest of the year,” Broughton recalls.

A toast on board the Endurance during Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1914-17. Frank Hurley, Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge/Getty Images

Explorers have always packed booze. Ferdinand Magellan never sailed without wine and sherry. During the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, Sir Ernest Shackleton stocked his ships with whisky to fight off the cold and endure voyages that could last more than three years.

Just as it was with Antarctica’s first visitors, so it is with its current residents. Every year, thousands of scientists, researchers, station staff, and even artists descend on Antarctica’s 45 research bases to live and work at the end of the world. (There are even more research stations if you include stations staffed only for the summer.) But those thousands winnow down to a persistent and hardy several hundred during the six nearly sunless winter months. (Once summer ends, planes and ships can rarely reach Antarctica due to storms and sub-zero temperatures that freeze fuel.) Their only external contact is through phones and the Internet. So the “winter-overs” come prepared … with heaps of alcohol.

Club 90 South was one of the many bars that serviced Antarctic research stations during Broughton’s winter on the continent. Broughton says that almost each of the 45 stations has a bar.

Broughton (center, holding a glass) behind the bar of the Club 90 South. Philip Broughton/Used with permission

After stepping inside from temperatures that reached -100 degrees Fahrenheit, says Broughton, Club 90 South felt like a portal back to the real world. Constructed by the Navy “Seabees” Construction Crew out of building and shipping scraps, the cozy space had the warm, smoky atmosphere of harbor-side barrooms, with chairs, couches, and a classic wooden bar scattered around a low-ceiled room.

Over the bar, empty Crown Royal bags (the drink of choice at Club 90 South) hung from strings of Christmas lights like bulbous, satin ornaments. The freezer was a hole in the wall to the frigid snow and ice outside. Entertainment consisted of poker tournaments, watching TV, listening to music, reading left-behind books, talking with family and friends back home, and experiencing the station tradition of stripping naked (except for shoes) and running from the station sauna to the South Pole marker.

Broughton at the geographic South Pole marker. It’s a station tradition to run to the marker wearing only shoes. Philip Broughton/Used with permission

No one owned Club 90 South, and no one paid. Instead, people shared supplies they brought from home (as part of the allocated 125 pounds of luggage per person) or bought from the station store. Bartenders did not earn salaries—only kudos. Broughton started tending bar Fridays and Saturdays, and soon he spent most nights after dinner mixing cocktails and pouring a “disturbing number” of Prairie Fire shots, which Broughton made with tabasco and tequila. He served absinthes from the astrophysics team, Black Seal rum from a Bermudan at McMurdo Base, and Bundaberg rum from an Australian. Mixing his research job with his side hustle, Broughton made cocktails using liquid nitrogen, bringing the haute cuisine trend of molecular mixology to the bottom of the world.

The best (and worst) part? No official last call.

Club 90 South, with its homey, pool-room decor and casual atmosphere, became a lifeline for many barflys. In a place of near-eternal darkness that lacked restaurants and movie theaters, it doubled as a station “melting pot.” The bar “bridged the gap between the ‘beakers’ and ‘support,’” says Broughton, referring to researchers on National Science Foundation grants and contractors who operated and built the stations.

“A few months in, everyone in the bar knew everyone’s stories,” he adds.

A 2006 picture of the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station during the winter. Chris Danals, National Science Foundation/Public Domain

But it wasn’t all cryogenic cocktails and sharing news from home. During the long months on a barren, isolated ice cap, drinking was often the only escape from the cold and monotony.

It’s an understandable reaction. Sink into a smooth glass of a favorite liqueur, and the cold bites a little less. The distance from loved ones feels more manageable. The time until the flight home, just a bit shorter. Some people drank to make the days go by faster. Regulars used pickaxes to clean frozen vomit off the ice outside Club 90 South.

Alcoholism can be a big issue in Antarctica. While there are no official statistics, some stations held Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, and the hearsay was troubling enough that in 2015, the Office of the Inspector General audited several American stations. Due to reports of drunkenness on the job and alcohol-fueled fights, the National Science Foundation, which supports and operates U.S. scientific interests on the continent, is considering mandatory breathalyzer tests.

But Broughton says the honor system and communal atmosphere at Club 90 South helped prevent the affliction.

“It got people to drink together, rather than alone in their rooms,” says Broughton. “While you might drink more than normal with good company, that is still healthier than unchecked drinking alone, as good company might also slow you down.”

A ski-equipped Hercules cargo plane at Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station, 2004. Public Domain

Broughton says he swapped out soda for booze when people drank too much, and he preferred to serve people so they could pass out in the bar, instead of watching them stumble out the door where, completely inebriated, they could hurt themselves or pass out in the snow.

After Broughton left the research station in 2003, Club 90 South closed during an effort to modernize Amundsen-Scott. But the legacy endures at other station bars, including Gallagher’s Pub, Southern Exposure, and the Tatty Flag. Broughton, meanwhile, is working as a radiation safety specialist at UC Berkeley, and he credits his time in Antarctica with his newfound interest in alcohol history and his appreciation for good, high-quality booze.

“I learned that if I’m going to consume alcohol, I’d better actually enjoy what I’m putting in my mouth,” he says. “Enjoyment is more than mere flavor.”

And would he go back?

“I would happily return for another winter” if my fiancée could come along, Broughton says. “I dream of Antarctica most every night. It is a haunting place.”

0 notes

Text

The Giant Frog Farms of the 1930s Were a Giant Failure

The get-rich-quick scheme couldn’t fill the world’s appetite for frogs’ legs.

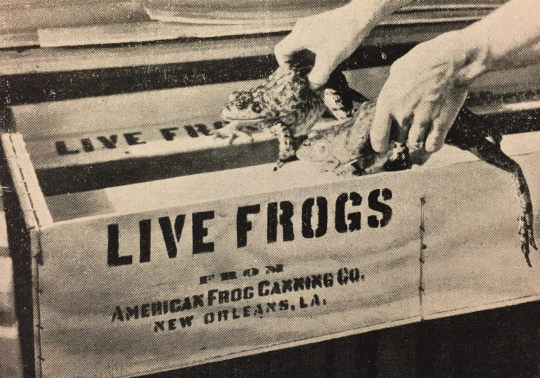

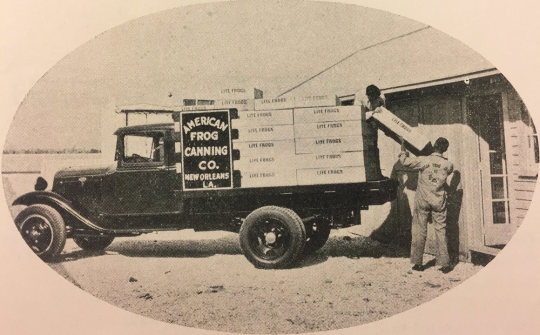

Live frogs, readied for shipment. All photos courtesy of Bonnie Broel.

The American Frog Canning Company had a pitch for people struggling to make a living in the 1930s, when jobs were scarce and money tight. The company promised a good market and a steady source of income. It was simple enough, the company promised. All you need is a small pond and a few pairs of “breeders” in order to…

Who are you to resist? American Frog Canning Company

Frog farming was “perhaps America’s most needed, yet least developed industry,” wrote Albert Broel, founder of the American Frog Canning Company and author of Frog Raising for Pleasure and Profit. With wild populations dwindling, the demand for frog meat was greater than its supply. The market for it had the potential to grow as exponentially as a new stock of frogs could.

Those few pairs of breeders, Broel explained, would produce tens of thousands of tadpoles, and it would take just this one generation to provide a frog farmer with a ready crop. At $5 a dozen (about $100 in today’s dollars), frogs could turn into a fortune. And people leapt at the opportunity. They wrote to Broel for copies of his frog-raising handbook, paid for a full course of frog-based learning, and ordered their breeders to start their own farms.

Frogs being shipped to their new home ponds.

From his base outside of New Orleans, Broel became America’s leading frog canner and promoter of frog culture. In one family portrait, he stands, stout and round-headed, on his cannery’s steps, in a well-tailored white suit. On the step below is his notably taller wife, and the couple is proudly flanked by two white statues of giant frogs, which reportedly had light-up eyes that blinked red in the night.

“I think his story is absolutely amazing,” says his daughter, Bonnie Broel, who keeps a collection of frog memorabilia in her Victorian mansion in New Orleans. “He came to this country and started a brand new business that no one had ever heard of, with nothing.”

Broel was a canny survivor, a descendant of Eastern European nobility, a practitioner of holistic medicine, a real-estate investor, and one of the few people who ever managed to make money from frogs. Because, while starting a frog farm was easy enough, raising frogs to market means fighting nature—and losing.

Bullfrogs can grow very large.

According to the story he told, Albert Broel started his frog business because of his mother. In one version, she had stomach trouble as a young woman. In another she stopped eating meat at 80, doctor’s orders. “As far back as I can remember, my mother used to say: —‘Son, if you want to make a success in life—Raise Frogs,” Broel wrote.

It wasn’t his first choice of profession. After settling in Detroit with a degree in naprapathy, a holistic wellness field focused on connective tissues, Broel opened a medical practice, married, and bought an apartment building. After being chased out of the medical profession for operating without a proper license, he followed his mother’s apocryphal advice. He started growing frogs at a large scale, on a 100-acre farm in Ohio, and experimenting with canning frog meat. With the money he made, in 1933 he moved his family to Louisiana, in search of a better climate for frog farming.

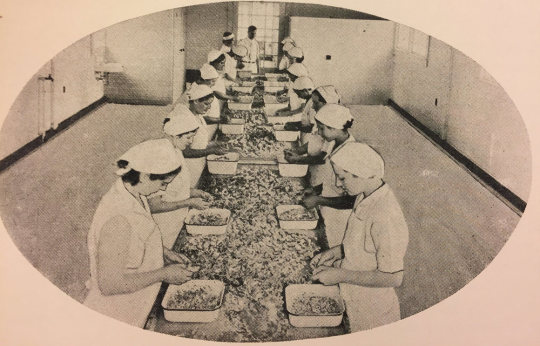

Soon, his business there was growing so rapidly that, he wrote, “my own frog farm and the supply of wild frogs brought in by hunters could not possibly keep the plant in operation.” He started running ads, like the one above, and soon frogs were being delivered to the factory from all over the country.

Broel was on the leading edge of what The New Yorker once called “the frog-farm craze of the thirties.” Newspapers across the country mentioned of the numerous letters they’d received asking for more information about raising frogs, and shared stories about frog entrepreneurs, from “society women” in Tennessee to a Japanese frog-raiser in Los Angeles. After Louisiana, Florida had perhaps the next most ambitious frog-farming operations. One, Southern Industries Inc., offered shares to northern investors in order to expand more quickly.

Among all these frog-minded people, Broel was a giant, “the nation’s largest individual producer of frog legs,” the Central Press reported, and a genius promoter of his product. He canned frog legs and “frog à la king,” and dreamed up recipes for Giant Frog Gumbo, American Giant Bullfrog Pie, Barbecued Giant Bullfrog Sandwiches, Giant Bullfrog Omelet, Giant Bullfrog Pineapple Salad, and more.

Canned frog legs could be prepared many ways, according to Broel.

As the craze grew, though, so did skepticism about the frog business. The industry, the Los Angeles Times wrote, was “somewhat ephemeral.” A Midwest paper compared it to rabbit farming, another get-rich-quick scheme meant to harness the reproductive potential of small food animals. In 1933, the USDA released a bulletin on frog farming that warned, “Within the past fifteen years the bureau has received thousands of inquiries concerning frog raising, but to the present time it has heard of only about three persons or institutions claiming any degree of success.”

That was a far cry from what Broel’s ads and other promotions promised, and in the mid-1930s, the U.S. Postal Service indicted him for mail fraud. “Frog Breeders Leap with Cash,” one newspaper gleefully reported. Broel and a partner had “hopped to New Orleans,” as another reporter put it, after cashing $15,000 worth of checks for instructional brochures.

One of the most egregious claims he’d published was that in 13 years, a man could make $360 billion growing frogs. “I assume it is needless to tell you that I made no such statement,” Broel wrote to one Ohio paper. Someone else had made the calculation, and Broel hadn’t meant to endorse its truth. It was “simply published as I publish all other things of interest to people engage in the frog business,” he wrote. “I think you will agree with me that such a statement is so ridiculous upon its face that it could not seriously influence the judgment of anyone deliberating as to whether or not he should engage in frog raising.”

But people had bought into the hype. Around the same time, one of the other frog-farm success stories, Southern Industries, was facing lawsuits from its investors, who had been promised big returns. After one year, they had still received no money, and demanded to know “why they had received no dividends on their investment in pairs of frogs.”

Frogs ready to be shipped.

One of the major points Broel made in his case for frog farming is that frogs are delicious. In the wild, “everyone” wants to eat frogs, he wrote: snakes, birds, lizards, fish, even hedgehogs. And that intense pressure from predators is the reason for their incredible rates of procreation. A single frog has to lay 10,000 to 20,000 eggs just to have a few of its offspring survive. Tadpoles are born to be disposable.

That’s one of the first problems facing a frog farmer. Most of those potentially profitable, would-be frogs die before reaching marketable size. Fungal diseases can wipe out thousands of frogs in a single season. And as the frogs grow, they have to be protected from hungry predators of all kinds—starting with their own parents. If frog farmers don’t whisk tadpoles away to separate ponds, hungry adult frogs will make meals of them.

Frogs eat a lot, and yet another challenge is keeping adult frogs fed. It takes about one pound of food to grow one-third of a pound of frog meat. Frogs have only one requirement for their meals, but it’s one that makes keeping them on farms very hard. Whatever they eat, whether insects, tiny crabs, or crawfish, has to be moving. “Production of live feed becomes a full-time activity in any frog farming operation,” one government pamphlet warns.

All this work has to go on for years before a frog farmer sees any profit. Whereas chickens, for example, can be raised and slaughtered in months, bullfrogs take two to three years to reach marketable size.

Workers picking frogs at the canning factory.

Even Broel didn’t depend on farmed frogs to feed his canning business. “We buy frogs!” announced a sign outside the company headquarters. Many of his suppliers weren’t farmers at all, but frog hunters who waded into the swamps of Louisiana, where it could be possible to catch 100 frogs in a few hours.

Frog hunting was so popular that the state’s population of wild frogs was declining, though. In his book, Broel used this as a selling point for potential frog farmers, but ultimately it proved the demise of his business. By the end of the 1930s, Louisiana had passed a law restricting the hunting of frogs in the high season, April and May. Cut off from a supply of wild frogs—a void that farming could not fill—Broel shut his canning company down.

“That’s really what put Daddy out of business,” says Bonnie Broel. “I know that he was not able to get enough frogs to maintain the business, even with the demand there was for it.”

Bonnie Broel with her father, Albert.

The American dream of frog farming didn’t die with the craze of the 1930s, though. Even after shutting down the canning factory, Broel kept selling “breeder” frogs. He didn’t grow them anymore, says Bonnie Broel, but rather worked more as a frog middleman.

“We knew if there were brown bags in the fridge, there were frogs in there,” kept in a state of hibernation, she says. “If I couldn’t take a bath, there were frogs in the bathtub, and he would be feeding them live goldfish.”

Decades later, during the 1970s and ’80s, the back-to-the-land movement bred another generation of would-be frog farmers, led by Leonard Slabaugh, owner of Missouri’s Slabaugh Frog Farms. “Supermarket chains and wholesale outlets buy ‘em in enormous quantities. Big restaurants want ‘em shipped out on ice. People come by here and pick ‘em up by the buckets full,” Slabaugh told a reporter for Mother Earth News. “Why, the market is growing continuously all the time.”

Among all the misleading hype of frog farming, this was a core truth. All over the world, people love to eat frogs, and by the end of the last decade, the international market in frog meat was worth about $40 million.