Text

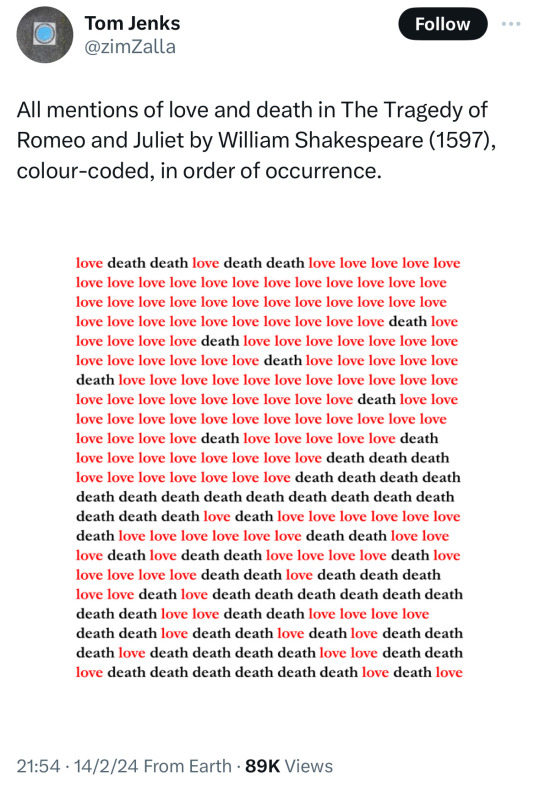

[discourse] in defiance of the author’s wishes (re: mxtx fandom)

table of contents

: context

: moral arguments

: addressing the legal side of things

: closing remarks

Context

on March 17, 2018, mxtx posted:

“As long as you don't split or reverse the top/bottom positions of the main couple, I won't mind what you ship. I myself have a lot of fun shipping couples in mainstream shows, and isn't reading all about finding joy? You can imagine freely or ship whoever you like, just don't break up or reverse the top/bottom positions of the main couple.”

(I realise that the 不拆不逆 “no splitting or reversing” rule might be implicit within the entire Chinese danmei fandom, so i do not wish to single mxtx out. for example, i know that Chinese 2ha fans also go around policing people who ship, say, chu wanning with shi mei — so this isn’t just a mxtx thing. although i do not know if other danmei authors have explicitly stated “no splitting or reversing” since i have not been a part of other danmei fandoms.)

Nevertheless, “no splitting or reversing” became the constitution in Chinese mxtx fandom. Fans parade around with the slogan “拆逆死“ which means “kill yourself if you split or reverse”. Since the pronunciation of 拆逆死 (chai-ni-si) sounds like “chinese”, some fans on the Chinese internet have been putting “chinese” in their bios to mean “kill yourself if you split or reverse”.

From now on I will be referring to split/reverse ships as cult ships, as Chinese fans like to call them.

There are two main consequences of the “no splitting or reversing” rule (on the Chinese internet):

You will receive permanent bans with no option for appeal if you post cult ship fanworks in the novel communities on Weibo

It is implicitly agreed upon that you are not allowed to use individual character tags, the novel tag, or the author tag when posting cult ship content on any platform. So, for example, if you write Wei Wuxian x Jiang Cheng, you are not allowed to use #weiwuxian #jiangcheng #mdzs #mxtx. The name given to this conduct of tagging only your cult ship is 圈地自萌, which means “enclose a piece of land and amuse oneself within it”. You are not allowed to step out of your land.

However, not everyone agrees with the practice of “don’t step out of your land” — this includes people from both sides of the debate. Some official shippers believe that cult shippers should not have any land to begin with, and purposefully leave the cult ship tag unblocked so they can police cult shippers at every opportunity. Some cult shippers believe that because their ship involves the individual characters, originate from the novel written by the author, they are in the right to use the individual character tags, the novel tag, and the author tag, and that people who dislike their ship should just use the block function.

-

Moral Arguments

There are two main types of moral arguments that Chinese official shippers make.

1. If you split the official ship, you condone cheating behaviour and that makes you a bad person.

The first argument is too trivial so I will leave the refutation as an exercise for the reader to do at home /j

2. You are not respecting the author's wishes and that makes you a bad person.

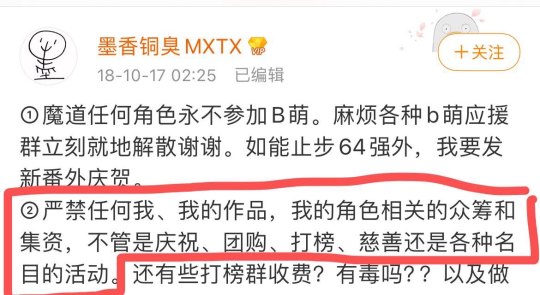

The author has wished many different things. For example:

Screenshot 1 translation:

I strictly forbid any crowdfunding or fundraising related to me, my works, or my characters, regardless of the purpose, whether it be for celebration, group buying, rankings, charity, or any other named activities.

Screenshot 2 translation:

Once again, I emphasize: No new social media pages related to my works are allowed, nor organizing readers in a roundabout way, whether it be for celebrations, group buying, rankings, charity, or any other named activities. Please also refrain from flamboyantly organizing any collective birthday events.

Screenshot 3 translation:

I've repeated many things many times and do not wish to repeat myself. Could everyone please just listen to my words occasionally.

(A brief aside before I address the second argument, something I used to say when debating Chinese fans: “I don’t think people who violate the author's wishes mean any disrespect. I don’t think they’re shipping or hosting charity events or birthday parties out of spite, but rather, it just so happens that the author prohibits a ship they enjoy or an event they organise. Just because I cult ship, for example, doesn’t mean I hate the author.” And they would respond: “if you really liked the author, you wouldn’t go against her wishes. You do not deserve to like the author. You are a mxtx anti.” And I would say, “I like my mom a lot, but I won’t listen to everything she says, simply because I don’t think everything she says is right. Plus, I don’t think the world can simply be explained by like vs. dislike. Also, Xie Lian said this: [For instance, if you admire or like someone, you won't always treat them well, no matter what happens.]” But then the most hilarious thing happened, in the revised version, a rebuttal for that scene was added:

【”For instance, if you admire or like someone, it doesn't mean you will always treat them well, regardless of what happens."

"Why not?" San Lang questioned. "If that's not possible, it only shows that this so-called 'liking' isn't anything significant."

Xie Lian shifted the conversation, asking, "Then... does it mean that aside from liking someone, the only other option is to dislike them? Are these the only two attitudes one can choose from?"

San Lang chuckled and retorted, "Why not? Right is right, wrong is wrong. To love is to love, to hate is to hate. Why can't things be clear and straightforward?”】

… ah.)

To address the second argument for real, i believe that producers retain no moral authority over the methods by which consumers engage with their products. for instance, i believe that choosing not to follow the official “twist, lick, and dunk” method when eating oreos does not constitute disrespect towards the oreo brand. Or to use another analogy, suppose a farmer selling apples insist that you peel the apples before eating them. I believe that it does not make you a bad person if you choose to eat the apples unpeeled, despite the farmer being the one who watered and harvested the apples from their trees.

I am thinking of potential counterarguments, and the strongest one I came up with is: “but products like oreos and apples are fundamentally different from intellectual property.” And I think the main issue here is that, to employ economics terminology, the content of novels like tgcf is a non-rivalrous good (not the novels themselves but the abstract content), which means that my consumption of it does not reduce availability to others. In other words, unlike Oreos or apples wherein after I purchase them, the specific items I bought are no longer physically in the hands of the vendor; after encountering characters like Shen Qingqiu, Shen Qingqiu still exists abstractly in MXTX’s head. This gives the illusion of ownership on the author’s part. I want to be very careful here because I think it’s easy to equivocate between different uses of the word “ownership”. I am not arguing that the author fails to retain ownership in negation of all the blood, sweat, and tears that went into the creative process, i.e. their copyright. Instead, I am contending that, just as I paid for my Oreos and apples, upon my purchasing of the Seven Seas version, the paperback Chinese version, and the revised uncensored version of TGCF on JJWXC, the author does not own the ways by which I choose to engage with these fictional entities. Once a work is made public, its ontology becomes independent of the author’s intent, and in all its readers’ heads exist distinct versions of the characters, in effect making them belong to all of us.

(There. As a bonus I have also resolved the issue of not being “chinese” enough. Ah, is this a bad place to make a communism joke?)

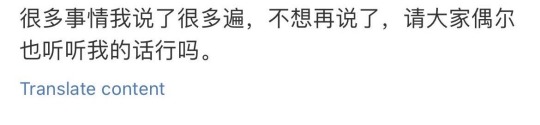

Addressing the legal side of things

In 2022 I wrote to the legal team at AO3, and here is their response:

Regarding the “moral rights”, that’s actually a thing. Upon receiving lots of spam from 12-yr-old readers that “you are breaking the law”, I did a quick Baidu search (China’s Google) concerning the legality of splitting/reversing ships. Surprisingly, the search results yield “yes, it’s illegal”, and hence the 12-yr-olds' confidence. But that is akin to getting a cancer diagnosis from searching symptoms on Google. So I dug deeper.

After reading tens of published papers and court cases, here are the key takeaways of what I found:

Given that intellectual property rights are a bit behind in China, they have largely based their laws on US copyright law. As organizations like OTW continue to fight for the rights of transformative works in the US, China probably will just follow suit.

The semantics of “distort, mutilate, or otherwise harm the integrity of their works in a way that harms the author’s reputation” is very vague and debatable. There are at least three ways to interpret it (I think one of the papers I read offered four). The first is that they only have to prove that you distorted the integrity of the work. The second is that you satisfy the condition of harming the author’s reputation. The third is that you satisfy both conditions (integrity of work and author’s reputation). It depends on the court.

None of the court cases pertained to unserious, just-for-fun fan works. Usually what happens is someone makes a film out canon, for example, and sell it for profit, or someone publishes their own novel which contains characters from another published work.

And that is for China only^ if you live outside of China, you are under another country's jurisdiction.

-

Closing remarks

I am addressing this issue because it has impacted me and my friends in many ways. "kill yourself if you split/reverse the official ship" is probably the least of our concerns, mainly because it is such a popular phrase that we've become desensitized to it. @/Eleven receives private messages on Lofter on a weekly basis of people wishing her entire family to get murdered. A hualian main friend of mine has been posted to Weibo for following me; and I had to pull a Shi Qingxuan with "hey let's not be friends anymore if being associated with me is gonna get you cancelled".

mxtx has been through a lot and i understand where she's coming from. and maybe, the people who identify as "kill yourself if you split/reverse the official ship" don't truly mean it -- maybe they're just expressing their love for the official ship.

Recently i've been seeing the sentiments I used to only witness in Chinese fandom surface on Twitter and sometimes I worry that western mxtx fandom is going to turn into Chinese mxtx fandom, with the in-group/out-group mentality -- you're either with us or against us. At the end of the day, I do like mxtx, I admire her tenacity and I think she's a brilliant author, I love her works and the characters in them. I simply do not want to be backed into the corner of "anti" due to not following every order she gives.

祝墨香和她的粉丝们平安。

#mxtx#thank you for this informative and insightful post#like I said last time 老中人骂人有的时候太毒了,动不动问候你祖宗十八代,而且国内墨香铜臭粉丝很多非常低龄心智不成熟

249 notes

·

View notes

Text

TGCF author's notes translation

@/camilikha on twitter kindly provided links to TGCF author's notes and I translated the ones I find informative and interesting. See translations below:

chapter 58 notes: The second book is all about the overconfident Xie Lian with delusions of grandeur and the tender little flower (mxtx means kid Hua Cheng) and their diaries of the downfall of Xianle. Word count is undecided, I'm never accurate at estimating word counts anyway. It's just like the xianxia I write doesn't fit into your regular xianxia, the royalty I write doesn't fit into your regular fictional depictions of royalty - just the outlandish made-up worlds and social customs in the author's imagination...

chapter 60 notes: If we put Qi Rong in a modern context, we could say that he has bipolar disorder.

chapter 72 notes: about the chapter title "To Meet You in the Mortal Realm; to Find Flowers Beneath the Rain" - eventually I feel that "To Meet You" is more romantic than "To Meet Someone". Just think about it, "meeting you" is one of the most romantic things in the world.

chapte 80 notes: Of course (HC) won't give (XL) a handjob or help him [...], but Huahua's sexual awakening starts with this incident... (XL is seriously obssessed with martial arts combat!)

chapter 88 notes: Xie Lian never gets tanned, I envy him... I finally reached this place - in a dilapidated temple, a god about to be forgotten and a believer who's still young - this is the first mental image I have about this story, which drove me to wrote the story. I'm the kind of person who'd make up a whole book just to get to write a certain passage...

chapter 119 notes: Actually Huahua is just being naughty and wants to joke around playing dead, who'd have thought...

chapter 123 notes: So Black Water made his appearance long ago, he's been hanging around before your eyes all along. Wind Master never knew the real Mingyi, it's always been the same person before him - and before you readers. (Black Water) officially recognized as Best Actor of this story! I've been holding it a secret for so long and so has he, now I can finally let it out.

chapter 141 notes: If you heat up Huahua in the kiln, he'll grow bigger~

chapter 175 notes: "Hua Cheng! Your diary! We've read it all!!!"

chapter 229 notes: Huahua low-key sucking up to the elderly to make a good impression

chapter 242 notes: Why do you like to spook yourselves? - why on earth would there be such plots as (XL) waiting for another 800 years - too long, impossible! Happy ending is around the corner!

SVSSS is my first work so it has some exceptions that I won't discuss here, but MDZS and TGCF both only have one main couple. I said this repeatedly in the author's notes when MDZS was being serialized and in other places. As for Mo Xuanyu, he is a little gay dude but he died at the beginning of the story so he doesn't count as a serious character...It's fine to have headcanons you like as long as you don't seperate the main couple. But for me personally, my taste leans towards having only one gay couple in the story, and I have no plans to write about another secondary couple. I'm stating this to avoid some unnecessary disputes.

XL is good at making pickled vegetables. Because pickled vegetables are needed with steamed bun and rice porridge, so XL became quite experienced after practicing for hundreds of years. Also you can just leave the pickled vegetable by itself most of the time and let it undergo chemical reaction. XL mostly fail because he get inventive.

XL and Mu Qing chose the same path of cultivation and are both Daoists. But Feng Xin never studied under a master at the Holy Royal Pavillion so he's not a Daoist and simply a plebeian martial god, so he doesn't need to observe the celibacy rules like XL and Mu Qing.

My passion for inventing new dishes (or rather weapons) cooked by Xie Lian is only slightly less than my passion for making Huahua change into new clothes

Huahua often turn into human forms, in which he has two eyes, so you guys can stop counting the number of his eyes.

In the setting of this story, if you want to be a god,you need to be a human hero first, which means you need to be the best of the best among humans. Only heaven officials who ascended are real heaven officials and belong in the Upper Court. How do you ascend? Firstly it depends on your personal ability, you have to be outstanding in some aspect (such as martial arts or literary talents) to enter the path of ascension. Secondly it depends on luck, if you're extremely lucky and a favourite of fate, and just picked up some rare secret guides (to ascension) or immortal pills by the roadside, that works too. Officials in the Middle Court are appointed, which means someone in the Heavenly Realm could promote you to that position. But Middle Court officials have the opportunity to become a bona fide Upper Court official too if they're capable enough.

Black Water indeed owes Hua Cheng a huge sum of money and is a very impoverished Calamity, seriously lowering the income standard of the Calamities (although there're only three of them). But his debt isn't completely due to eating too much. As for the money Black Water owes, it's an ancient debt - 40% is the cost of buying gifts for heaven officials of Upper Court and planting agents there (bribery!), 30% is maintenance fee for his territory and expenses on pet food, the rest 30% is food (for himself).

Talismans are probably the equivalent of the business cards (of heaven officials)... "Hello this is my consecrated talisman" = "hello this is my business card"

You can't get rid of ghostly essence (which XL is tainted with because he spends too much time with HC) simply by brushing your teeth with plain water...you need to use consecrated spell water (which is super bitter and weird).

The weapon forged by a heaven official is called fabao (literally "dharma treasure"); if it's a weapon forged by mortal Daoists and monks, it's called faqi (literally "dharma tool") - only after their ascension can their weapons be called fabao.

In my imagination, Xianle ia the kind of small ancient kingdom that's overall culturally Han, but has peculiar customs...although I feel like what I wrote on Xianle is mostly just peculiar hahahaha [facepalm] [beat myself up]

Not only are the forms, customs, cultures, and politics of countries in this story made-up, the kind of arcane stuff like occult sciences and philosophical values are all made-up. Although I did research but the records I consulted are too difficult to understand, so I just made things up on my own. Please bear with me If you're knowledgable in this sort of thing hahaha.

Puqi refers to water chestnut.

Look up "Blood-Soaked Fire Social" (xue she huo) if you're interested, it exists in real life and is very thrilling. What I wrote is different from the traditional festival, there're some made-up elements to make it more exciting

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

anon asking about Jun Wu - I'm busy with work atm and need to go back and reread some stuff to answer your ask, but I will answer ASAP :)

0 notes

Text

youtube

The first official promotion song for 2ha novel called "when haitang flowers fall again in the light rain" (海棠又落微雨時) came out recently, I loved it so translated the lyrics:

in past life I was the god of war sneering at the loneliness of the mortal realm

In this life I'm the Buddha fallen into the cycle of reincarnations burning in its suffering

If like trees and grass you know not the pain of love

Then why turn back and weep about both love and hate wearing thin

You sigh, saying that the falling of haitang flowers is inevitable

What can you do when it was all a good dream and never real?

Heavy snow covered the long steps and you pleaded piously

To be granted a few lifetimes of entangling your fate with his

Three thousand steps speak not

About lifetimes of being together and apart

The memories are troubled by trials and miseries - that's why it's deep, that's why I remember with all my being

Flowers bloom and I forget my sadness; flowers fall and it adds to my sorrow

Who is it that lingers in this place?

When I dispel sorrow from my heart, it only reappears on my face

The stubborness that persist through cycles of reincarnations

Has no regard for the romances and grievances of the past

All of a sudden, snow covers the world

In the light rain, when the haitang flowers fall again, there I will wait for you

See the slanting rain silently weaving my loneliness

My eyes are filled with sorrow, yet for what?

My blood-stained hands hold you tightly

To keep you by my side

When haitang flowers bloom, I recall kissing your cheek

I dreamt of walking down the corridor and the long steps, only desolation strewn across the ground

That year, the days were too long

That year, the wind was howling

Forget not the moment we embraced each other

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

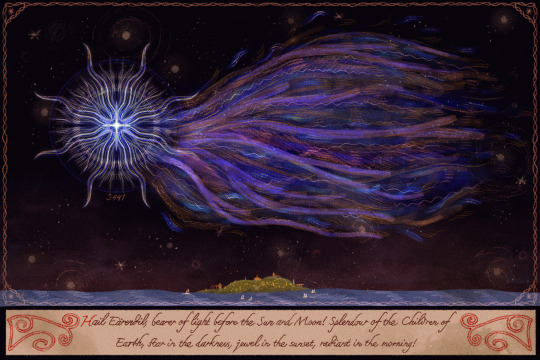

eärendil the mariner soaring over númenor in star form

inspired by the book of miracles

342 notes

·

View notes

Text

the story of how Feng Xin ended up with the name Ju Yang (big D) reminds me of the story of why Chinese people hang the character that means “blessing” (福)upside down on their doors during Chinese New Year.

one version of it is:

On the eve of the Spring Festival during the reign of Emperor Xianfeng of the Qing Dynasty, the chief steward of the Prince Gong's mansion, aiming to please his master, wrote several large "福" (blessing) characters to be posted on the storeroom and the mansion's main gate. However, one of the servants, being illiterate, accidentally posted the "福" character upside down on the main gate. This greatly annoyed the prince's consort (wife), who wanted to punish the servant with a whipping. Fortunately, the chief steward was a persuasive and eloquent speaker. Fearing the consort would blame him and affect his own standing, he quickly knelt down and explained: "I have often heard people say that Prince Gong has a long life and great fortune. Now that the '福' has 'arrived' (which is a homophone to “being upside down”), it is a sign of good luck." Upon hearing this, the prince's consort went from anger to joy, thinking: "No wonder passersby have been saying that Prince Gong's fortune has 'arrived.' A saying repeated a thousand times can bring wealth in gold and silver. An ordinary servant couldn't have thought of this!" Consequently, she rewarded both the steward and the servant with 50 taels of silver each. Later on, the custom of posting the "福" character upside down spread from the mansions of officials to the homes of ordinary people, hoping that passersby or mischievous children would chant "The fortune has arrived! The fortune has turned arrived!" for good luck.

74 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! you made a post about the newly translated extra and i was wondering where you read it :)?

Hi! I read the original Chinese on JJWXC so idk if anyone has translated the chapter, this ask contains a link to ongoing translations of revised chapters, hope this helps.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#first poll I ever made so hope it's not too bad#this is from the perspective of a Chinese person who wants to know what international fans think#danmei#tgcf#2ha

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dug up a very old paper I wrote almost 6 years ago titled "Tianyuan Feminism and Women in Contemporary China," putting it here if anyone's interested in reading this verbose thing:

Zhonghua tianyuan nüquan, which literally translates to “Chinese rural feminism,” is a term that became popular on the Chinese internet in recent years. It should be noted that the phrase nüquan, meaning “feminism,” is used ironically and negatively within the term, as the zhonghua tianyuan nüquan represents a set of beliefs contrary to feminist ideals. Also, zhonghua tianyuan, meaning “Chinese rural,” does not indicate the rural areas of China, but as is generally agreed by Internet users, refers to a breed of domestic dogs indigenous to China. Therefore, “Chinese rural” really signifies the indigeneity of the concept. The phrase tianyuan, which means “rural,” can also refer to an idyllic countryside far from the scenes of buzzling life, and its implication of utopian impracticality leads to some people’s interpretation of tianyuan as “empty talk with no practical results” (Du, “A Reinless Wild Horse in the Age of New Media”). For the sake of brevity, I will refer to zhonghua tianyuan nüquan as “tianyuan feminism” in my following analysis. I will discuss the meaning of tianyuan feminism, its indigeneity, the possible reasons for the rise of such phenomenon, and people’s usages of and responses to the term.

What is tianyuan feminism?

In a discussion board titled “what’s the definition of tianyuan feminism?” on Zhihu, one of the most popular online forums in China, a top comment that received over eight hundred likes defines tianyuan feminism as thus:

Tianyuan feminism is a freak born of the hybrid of the remnants of Chinese feudalism and Western consciousness of individual rights. These women have no idea what feminism is. They want the benefits of Western idea of equality, but neither are they willing to let go of traditional gender notions. This double standard is, in essence, a form of utilitarian selfishness and greed […] Only the unique social and cultural environment of China can give rise to such grotesque “feminists” who ask men to provide for the family like women in Japan and Korea do, but also try to get away with responsibilities by evoking the ideas of personal freedom and rights like women in Western societies[1].

While the commenter did not specify what responsibilities these women try to avoid, many of the male internet users who complain about their girlfriends or wives being “tianyuan feminists” list the shirking of economic responsibilities by the women as the primary problem. More specifically, women labeled “tianyuan feminists” would demand that their male partners pay for everything either on dates or within a marriage – which include the wedding, the house, the cars, and other daily expenses; they would push men to earn more in order to amply provide for themselves, and would chastise their male partners if they fail to do so. The underlying logic of such practice is that women are the weaker sex oppressed within the patriarchal system, therefore they should be compensated and taken care of, meaning that all responsibilities go to men. One of the main arguments used by tianyuan feminists is that women have done their essential part in marriage by giving birth to children; since they have made their main contribution through childbirth, men should take up all other responsibilities. One can see at a glance that tianyuan feminism is the opposite of what real feminism stands for: by shoving all economic responsibilities onto men, tianyuan feminists deny their own potential to excel professionally and achieve economic self-sufficiency, and by seeing their greatest value in giving birth to children, they objectify themselves and ignore their innate self-worth. It is not self-esteem, self-fulfillment, independence, or equality that they strive for, but material benefits and superior treatment from the other sex. Tianyuan feminists have internalized the idea of feminine inferiority, and instead of challenging the patriarchal system, they try to exploit it to their own advantage.

Tianyuan Feminism versus Feminism

The curious thing is perhaps that tianyuan feminism is associated with feminism at all. Unlike the principles of human rights and equality upon which feminism is built, tianyuan feminism devalues both men and women by objectifying and commodifying them, and as one commenter on Zhihu crudely but vividly describes tianyuan feminism: “the man keeps the woman like a pet, and the woman sees the man as an ATM machine” (Zhihu Journal: Women’s Rights Equals Human Rights 63).

However, tianyuan feminism is associated with feminism because, first of all, tianyuan feminists demand rights as feminists do, although they do so from the premise of accepting the patriarchal system and their gendered inferiority. While by definition tianyuan feminism is a form of “false feminism” or mockery of feminism, many Chinese internet users genuinely confuse tianyuan feminism with real feminism, and even consider tianyuan feminism to be a branch of feminism. This confusion leads to further stigmatization of feminism on the internet, adding the accusations toward tianyuan feminism such as “selfish,” “materialistic,” and “unreasonable” to the already proliferating vilifications of real feminism. It also reflects a trend of thought on the internet which conveniently attributes every objectionable behavior or mentality of women to the influence of feminism. As Chinese scholar Dong Jing notes in her article:

If women says things that are too ‘radical,’ it is at the instigation of feminism; if women ride roughshod over men, it is because of the ‘cancerous’ influence of feminism; and if women do not wish to apply themselves in work, and ask men for financial support instead, the fault is with feminism again, and such women are called ‘feminist sluts’ with double standard – it is as if women are led astray all because of feminism. (Dong, “Don’t Yell ‘Feminism is Cancer’ if You Don’t Understand Feminism”)

The confusion of tianyuan feminism with feminism stems from people’s limited and often biased understanding of feminism in China. Feminist ideas were introduced into China at the end of the nineteenth century, but as Li Yue observes, “Throughout the hundred years between its emergence and the present, feminist movement in China has always lacked theoretical explorations and guidance, and Western feminist movements have had very limited influence on feminist movement in China” (Li, “A Comparison of the Development of Western and Chinese Feminist Movements and Their Emergence”). The peripheral status of feminism in China means that issues and ideas associated with feminism have never received sufficient attention or clarification.

Feminism in China took roots during a series of social reform movements starting from the late nineteenth century, such as the Hundred Days’ Reform and May Fourth Movement, which introduced Western ideas of human rights, democracy and equality into China. During that time, women activists such as Tang Qunying and Qiu Jin actively participated in revolutionary movements and demanded political rights for women, while in the literary field, “protofeminist contestations of women’s identity” began to develop “in the writings of women like Zhang Ailing, Lu Yin, Shi Pingmei, and Ding Ling, who has been called ‘the founder of modern Chinese feminism’” (Schaffer and Song, “Unruly Spaces: Gender, Women’s Writing and Indigenous Feminism in China”). However, a fully-fledged women’s movement never took shape, either during the turbulent revolutionary times of the early twentieth century or in the following hundred years. Women like Tang Qunying and Qiu Jin were exceptions in a male-dominated political landscape, as much as is the case now in the Chinese political scene, where “no woman has ever ascended to the elite Politburo Standing Committee, the small cabinet that effectively runs the country in concert with the president,” and where “the pattern of under-representation ripples down through the entire political system” (Cunningham, “Good Girls Revolt: The Future of Feminism in China”).

Besides its peripherality, women’s movement in China never achieved independent status, but has always been seen in association with the larger social and political context. Xu Jiaqing and Li Xi comment on women’s liberation movement in China during the last century that “women’s liberation movement in China has always been led and guided by Chinese men, and is closely linked to China’s social revolutions and constructions. Men were the first to realize, on the social level, the oppression and abuse of women by the feudal tradition, and consequently put forward the slogan of ‘equality between men and women’” (Xu and Li, “Feminism in Chinese and Western Contexts”). The situation has not essentially changed in contemporary China. In their 2007 article “Unruly Spaces: Gender, Women’s Writing and Indigenous Feminism in China”, Kay Schaffer and Song Xianlin note that “the movement towards women’s equality is linked to China’s ‘carefully propagated self-image of socialist modernity at the heart of China’s drive for progress and sovereignty” (Schaffer and Song). If one visits the official website of All-China Women’s Federation (ACWF), the state sanctioned women’s rights organization, one can see that the front page is occupied by the slogan written in big red letters “Women Heroes Turn Their Hearts to the Communist Party, Making Contributions to Building the New Era.” Women’s liberation and enlightenment is linked to, and ultimately serves China’s economic progress and modernization, while women’s individual rights and self-fulfillment are attributed little importance.

The marginalization and virtually absence of women’s movement and feminist thinking obviously do not help the public to understand and sympathize with the feminist cause, and has contributed to the bizarre situation where, while terms such as nüquan zhuyi (the Chinese translation of “feminism”) and tianyuan feminism are freely and casually used, discussed, and debated on countless occasions across the internet, little action is taken in real life to promote the feminist cause or propagate women’s rights. “Feminism” as a concept seems to be emptied of its innards, or substance as it were, and cannot find a solid foothold in people’s lives or their intellectual understanding. Consequently, vague, misrepresented, or even libelous descriptions of the term “feminism” float around the internet, and become conflated with people’s criticisms of tianyuan feminism, creating a larger stigmatized image of nüquan zhuyi that is at once messy, confusing, and intimidating. As Wang Lan explains in her article “The Spread of Feminism in the New Media Environment:”

Due to the highly open and accessible nature of new media, the varied degrees of enlightenment of its users and the slow development of feminism at one time in our country, the state of unchecked spread of feminist ideas in recent years leads feminism in China to exhibit a ‘Year Zero temperament.’ Some women have rather biased misunderstandings of feminism, others try to avoid responsibilities in the name of feminism, giving rise to ‘tianyuan feminism’ which stresses personal rights but shuns obligations. Due to the spread of this erroneous ‘feminist’ thinking, many people developed an aversion to feminism even before they can get to know what feminism is truly like. (Wang, “The Spread of Feminism in the New Media Environment”)

While tianyuan feminism may have started out as ironic criticisms of beliefs and practices contrary to true feminist ideals, it has sometimes been subsumed under feminism due to people’s insufficient knowledge in and misunderstanding of both nüquan zhuyi and tianyuan feminism. Many internet users express the belief that nüquan zhuyi (or feminism), just like tianyuan feminism, possess the central tenet of exploiting men and serving women’s self-interest. This state of affairs is apparently detrimental to the development of feminism in China. As a commenter on Zhihu insightfully remarks, “considering that feminism in China has not yet taken shape, and that there aren’t so many feminists in China yet, to throw around labels such as tianyuan feminism and false feminism could strangle feminism in the cradle[2].”

Women’s condition in contemporary China

In this section I would like to explore the reasons that may have led to the rise of tianyuan feminism. While tianyuan feminists are characterized as materialistic and self-serving, one main reason for it is probably the financial and social insecurities that women in contemporary China face, as Schaffer and Song observe:

The market-driven reforms and Open Door policy have had more negative effects both materially and symbolically for women. The reforms offered men increased opportunities in education, employment and financial success. Women, however, had to face the dilemma of choosing between the demands of a career or a family. (Schaffer and Song, “Unruly Spaces: Gender, Women’s Writing and Indigenous Feminism in China”)

Workplaces are often more willing to employ men because women’s pregnancy delays work progress, and many women leave their jobs after giving birth, making them a destabilizing factor at the workplace. Besides workplace discrimination that makes it harder for women to find employment, women who give up jobs to take care of their children become financially dependent upon men.

Besides women’s financial insecurity, traditional gender discrimination against women accentuates their social insecurity. The traditional saying “a daughter that is married off is like spilled water” accurately reflects the mentality of many Chinese families who see a married woman as belonging to and subsumed under her husband’s family and dependent upon her husband, and is no longer part of her original family. This means that it is harder for women than men to gain financial and emotional support both from her parents and from her in-laws.

The economic and social vulnerability of women contributes to some women’s desperate determination to seek financial security and guarantees of material comfort from the most convenient and apparent source – their male partners (a defining trait of tianyuan feminists). While women’s financial and social independence is another route, it is not necessarily encouraged by society. After women’s liberation in the early twentieth century and the “iron-girls” of Maoist era who actively participated in socialist constructions, the present market economy, where “the collusion between capital, patriarchy and state is hardly rare” (Song, “Is Chinese Feminist Thoughts Abducted by Western Theories?”), sees a return of women to the traditional gender role of wife, mother, and beautiful object. According to Tania Angeloff and Marylène Lieber,

The move from a planned to a market economy had significant consequences on the evolution of inequalities between the sexes. While the Maoist state (1949-1976) sought – at least in official discourse and employment policy – to eradicate inequalities between men and women and their adherence to pre-communist traditions, the reform and opening policies adopted in the late 1970s were largely built on the traditional representations of women’s role in the family and in society. (Angeloff and Lieber, “Equality, Did You Say? Chinese Feminism After 30 Years of Reforms”)

All-China Women’s Federation (ACWF), which voices the state’s view on women’s rights, also tilts the public opinion toward seeing women in their traditional role – that is, within the family. An article published on the ACWF website on October 29, 2018 quotes president Xi Jinping saying “we should stress women’s unique role in promoting China’s traditional familial virtues” and “women around the country should voluntarily shoulder the responsibilities of taking care of elderly family members and educating children, as well as upholding familial virtues[3];” another article on the website, published on November 13, 2018 titled “Shao Yanlin’s Family: Good Wife Setting Positive Example by Looking After Sick Father-in-law” details the life of Shao Yanlin, who takes care of her father-in-law with laryngeal cancer, and is rewarded the title of “the good wife of Gu-lu-ben-jin Village[4].”

The aforementioned workplace discrimination and women’s internalized perception of their dependent status and essential role as wife and mother is reflected in a national survey conducted in 2010:

The Third Survey of Women’s Social Status in China in 2010 shows that almost 62% men and 55% women believe that “men belong to the public life, while women belong to the family,” with the percentages rising 7.7 and 4.4 percent compared to 2000; at the same time, wage gap is broadening. In urban areas, the average yearly income of women is only 67.3% of that of men, and the percentage is 56% in rural areas, with the percentages dropping 10.2% and 23% compared to 1990. (Liu, “‘Crazy Women:’ From Version 1.0 to 2.0”)

It is not only the governmental opinion that leads to a regressive view of women’s place in society, but the popular media as well. As Liu Jin argues,

From the images incessantly constructed by the media of women as traditional good wives and good mothers or modern ladies valued for their pretty faces, we can smell the rotten and outdated values and gender notions that should have been eliminated. Media’s portrayal of women unconsciously influences its audience’s (including female audience’s) perception of women: that women are meant to do housework and sacrifice their careers for family, and that it is in their nature to bear and raise children. This prevalent view, attitude or prejudice means that men keep their dominant social position and women’s status is weakened. (Liu, “The Construction and Subversion of Popular Internet Term ‘Straight Man Cancer’”)

The media and the consumerist market not only promote the idea of women’s retreat into traditional family roles and female objectification, but also harmfully encourage women to seek self-value in material possessions and self-objectification. Advertisements and promotional texts from companies that sell luxury and fashion products are often identified by internet users as sources of information that foster a tianyuan feminist mentality. These advertisements and texts tell women that they deserve to treat themselves better, that the products they buy reflect their own beauty and sophistication. In this way, women are encouraged to over spend, and consequently often turn to their boyfriends or husbands for money.

We can see that in contemporary China, women are still beset with gender inequalities, economic and social disadvantages and pernicious and outdated gender notions. While these factors should not justify tianyuan feminism, they do contribute to its emergence as a social phenomenon.

Usages of and Reactions to Tianyuan Feminism

I have discussed how tianyuan feminism can be mistaken as one kind of feminism by some internet users who have misunderstandings about the subject, and can serve to further stigmatize feminism. On the other hand, more enlightened internet users have tried to clarify the difference, in fact the clear opposition between tianyuan feminism and feminism, and explain that feminism does not stand for gender superiority or women’s exploitation of men, but can actually help create a win-win situation for both sexes where there is shared responsibility and mutual respect, and neither sex need to suffer gender stereotypes and their accompanying social expectations.

Due to the fact that tianyuan feminism is a popular internet term with no traceable origin and no authoritative definition, and have passed through the hands of countless internet users, it is by nature sensational and ambiguous, and have picked up a complex host of connotations, implications and associations along the way. From Du Yunfei’s definition of tianyuan feminism in his article on tianyuan feminism, one can glimpse the confusing assortment of conceptions that tianyuan feminism has come to represent:

The group identified as tianyuan feminists on media platforms usually exhibit the following immoderate qualities: firstly, they detest men and patriarchal power, and when discussing topics of gender inequality, they aim their criticisms at men under all circumstances; secondly, they want to enjoy personal rights without undertaking obligations, and consider themselves to naturally possess moral high ground in society, at work, in the family and in relationships between the two sexes due to their biological inferiority; thirdly, they hate traditional gender roles, especially those that demand self-sacrifice for the sake of marriage or family, and they disapprove docile, beautiful and family-oriented women who are perfect in the traditional sense; fourthly, they have extremist attitudes and give radical speeches, and overexaggerate the unfavorable conditions in which Chinese women live.” (Du, “A Reinless Wild Horse in the Age of New Media”)

The four definitions put together can hardly describe one single type of woman: while the woman of the second definition is passive and dependent, the woman described in the other three definitions is angry, extreme and men-hating. We can see that besides being used to refer to women who believe they have every right to leech off the patriarchal system, tianyuan feminism has also come to represent extreme and men-hating speech and behavior. On other occasions, tianyuan feminism has been used as a generic insult to women with feminist tendencies, or even used to demonize feminism. For example, some internet users believe that tianyuan feminism is feminism in its extreme and irrational form that aim to exterminate all men and establish a matriarchal society. Other times, tianyuan feminism is linked with issues of race and sexuality: some see Chinese women who prefer wealthy white men to Asian men as tianyuan feminists; others claim that tianyuan feminists have a particular hatred for straight men but leave gay men alone. When browsing the internet, it is easy to get lost among the endless arguments, assertions and heated discussions, which, nevertheless, reminds one of the connotation of the phrase tianyuan mentioned at the beginning of this paper: “empty talk with no practical results.” The enthusiastic debates about tianyuan feminism and feminism online forms an ironic and stark contrast to the silence and inaction regarding the issues of women’s rights and social conditions in real life. While discussions about feminism on the internet can help raise awareness on the subject, Chinese women and the Chinese society have a long way to go in defending women’s rights and fostering the ideas of gender equality, self-respect and self-worth in women.

[1] See Zhihu discussion board (https://www.zhihu.com/question/266449349/answer/439864556).

[2] See Zhihu discussion board (https://www.zhihu.com/question/266449349/answer/439864556).

[3] See online article (http://www.women.org.cn/art/2018/10/29/art_19_158955.html).

[4] See online article (http://www.women.org.cn/art/2018/11/13/art_19_159188.html).

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Haven't finished Yuwu yet but I'm thinking about the dark side of Gu Mang's indefatigable optimism, which could amount to denial of the prospect that he could be hurt and broken by his misfortunes, that he might not be strong enough to survive all his trials intact, that he could fail to protect those he loves and cares about. This reluctance, if not inability, to accept his weakness and failures is what makes him push himself to the brink of death again and again to accomplish his tasks, and shut Mo Xi out instead of communicating with him because he can't face having failed to protect Mo Xi. It's like a light that refuses to have shadows will be snuffed out (and "snuffed out" is what Mo Xi's name means...)

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m stuck in the 2ha and SVSSS hellhole,,, 😭

505 notes

·

View notes

Text

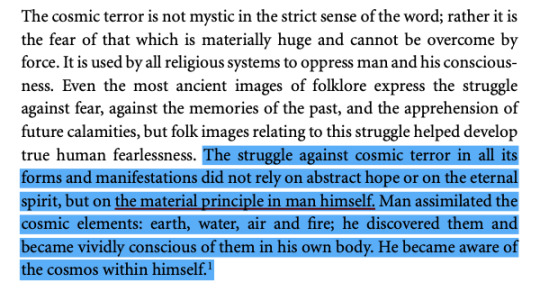

This is a few paragraphs of Bakhtin's interpretation of the relationship between the grotesque and the cosmic terror - Bakhtin believes that the grotesque's "earthy materialism of the populus" posits a challenge to the aristocratic/elitist hierarchy and ideology of the cosmic terror. I find this to be a fitting representation of the relationship between the Heavenly Court (the cosmic terror) and the Ghost Realm (the grotesque) in TGCF.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

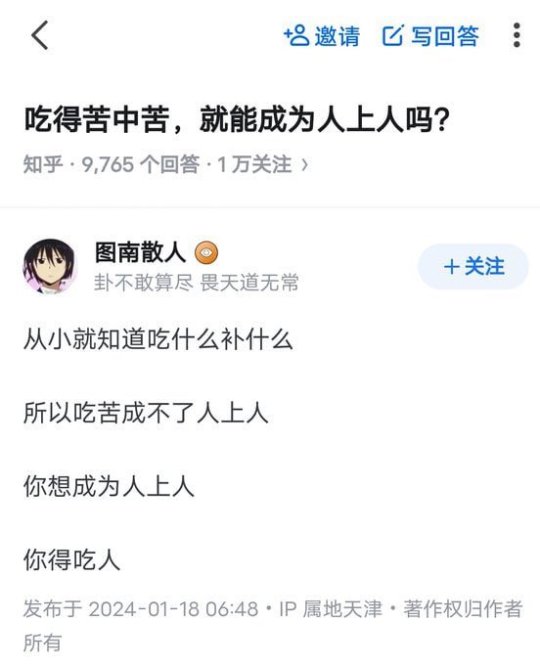

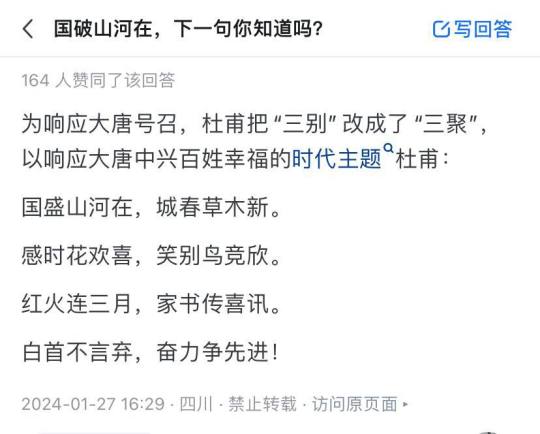

最近网上看到的一点零碎

海边的西塞罗停更微信公众号:

CCP so afraid of gays and lesbians like

中肯

鲁迅棺材板压不住了,万恶的旧社会一点没变

开左灯打右转

杜甫棺材板也压不住了

this is very eloquent

破产的改革开放

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I first started reading MDZS and reached the moment when Lan Wangji said to Wei Wuxian ‘我在’ ("I’m here.") for the first time, I was struck by how mundane yet significant this line sounded. True to form, it recurred throughout the story, much like Hua Cheng’s “Fear not, gege” or “Trust me, Dianxia.”

I'm starting to believe that it's the sentiment and mentality behind these lines that truly define the 'gong' in MDZS and TGCF. As someone who's only read three BL/danmei novels so far and obviously has no clue what she’s talking about, I appreciate how the gong/shou dynamic is less straightforward in both. I love how some fans affectionately refer to Hua Cheng as 花怂 (essentially, a wuss, but in an endearing way) and Lan Wangji is initially mistaken by some, including myself, as the shou, while both shous are every bit as powerful and strong in their own right. It's less about dominance; but about being that 'something firm and reliable' (lol) standing tall and steadfast behind their shous when the sky falls, because their shous are good, and kind, and will always want to do the right thing, and save everyone, and therefore doomed to crash, burn, suffer, fail. But that’s ok tho, because, “I’m here. Fear not.”

99 notes

·

View notes