Text

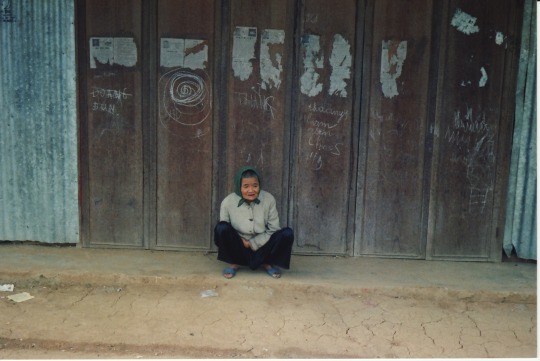

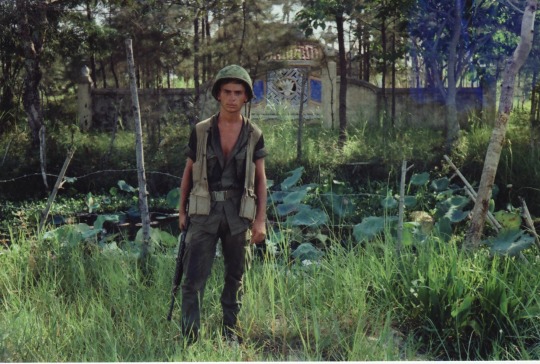

Photographs from the front lines of Vietnam (1968) taken by Oliver Stone. Part 1.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A week in the life of Oliver Stone

Sunday

I spent most of the day at home in Brentwood, Los Angeles, recovering from a heavy week spent cutting a new, three-and-a-half-hour DVD version of my film Alexander. In the evening, I drove to Hollywood to give an award to actor Michael Peña for his role in my latest film, World Trade Center. It was an easygoing event, full of fresh faces. English actress Emily Blunt made quite a splash. She seemed like a force of nature.

Monday

Up at 5am to catch a plane to New York. I used the seven-hour flight to update my diary; it’s really just a compilation of notes from memory. When I’d dropped my bags at the Mark Hotel in Manhattan, I headed to the Museum of Modern Art for a reception for World Trade Center. My mother, my ex-wives and my friends were there, along with Will and John – the real policemen who survived 9/11, on whose story we based the film – and a dozen others who’d rescued people from Ground Zero. It was a good mix.

Tuesday

After a few hours of paperwork, I went over to the Brook Club on East 54th for a lunch hosted by my old friend Chuck Pfeiffer, a real New Yorker. I chatted to PJ O’Rourke and some crazy artists, then headed out of town to Westchester for a Q-and-A to mark the 20th anniversary of my film Platoon. It was an uptown, educated crowd, with a higher level of debate than usual. Good preparation for England, I thought, as I caught the red-eye to London.

Wednesday

My wife Chong and my 11-year-old daughter Tara flew in to London from LA. We huddled together in the afternoon, walking the cold streets and shopping in Fortnum and Mason. They sat in the audience at the National Film Theatre while I was interviewed by Mark Lawson about my career. Then we popped into the British Comedy Awards, where I gave an award to Wallace and Gromit. I tried out some stand-up on stage; it felt like the audience was with me.

Thursday

At the Science Museum with Tara, I got excited about the industrial revolution. Science was my weak spot in school and I stood there, trying to understand how the steam engine worked, while Tara pressed computers and told me it really wasn’t that complicated. We dragged ourselves away so I could do a TV interview with David Frost for Al Jazeera. He really represented the swinging 1960s, and he still had that charm and lightness of touch. He’s interested in the world; the way I see it, if you can maintain that interest, you stay interesting.

‘World Trade Center’ is out on DVD on Jan 29.

-Laura Barnett, The Daily Telegraph, Jan 6 2007

#oliver stone#the daily telegraph#london#uk#world trade center#bfi#mark lawson#chong stone#tara stone#diary

1 note

·

View note

Text

Any Given Super Bowl Sunday

There are two visions of the game of football in Oliver Stone's "Any Given Sunday." In one, the game becomes a metaphor for everything that is wrong with America -- racism, wanton violence, the commercialization of just about everything. In the other, football is an almost mystical repository for everything the director seems to believe in -- tradition, courage and self-sacrifice.

With Super Bowl Sunday dead ahead, Stone talked about a lifelong love-hate relationship with the game, including his (not-so-glorious) playing days, the evils of TV timeouts and a Super Bowl bet he wishes he'd never made.

This season in the NFL was particularly brutal, on and off the field. We saw nine stars go down with serious injuries, a player pushed a referee to the ground, another was accused of murdering his pregnant girlfriend. Is this a vision of the future of the game?

I think this has been going on in the NFL all along. What's happened is the media fishbowl got too fast for them. I mean, also you might add that Cecil Collins for the Dolphins got in trouble, breaking and entering, but this has been going on for years in the NFL. When we researched [for "Any Given Sunday"] and found out about this stuff, [the NFL] got very sensitive about that issue, especially domestic abuse situations. But that is the nature of aggression. Aggression is required to play the game. Sometimes it leaks over into the rest of life -- not in everyone. Guys have been fighting with refs for years, players have fought each other. Now, if anything, it's become more civilized.

What are the two things that most irk you about the game these days?

Defensive [pass interference] calls. I think it's impossible to be a defensive back and guard against the pass. You can easily give away 40 or 50 yards for a nothing push, with just a glancing blow -- not anything that interferes with the pass receiver in any intentional way. They have been calling a lot of that over the season. I think it's appalling that you can get 40 or 50 yards on a call.

Yeah, that's what's different about the college game: You only get 15 yards.

It changes the game. That's one of the things that really annoys me. The second thing is commercial timeouts. The intrusion of commercials is bullshit. It's part of the whole commercialization of American culture. As Jim Brown was the first to point it out to me, how many times have you seen on TV a team march down the field and get to the 20 and they take a TV timeout? The whole stadium goes quiet, waiting for the television commercial to play out, stretching the game out. The team has lost its concentration, as well as its momentum. It's a shame. The game has changed.

Who was your team growing up?

Growing up in the '50s, I was a fan of the 49ers.

Where did you grow up?

New York.

So why were you a 49ers fan?

Don't ask me, it's just the Giants got so much attention. I always liked the other guys. They had that million-dollar backfield: Y.A. Tittle was the quarterback; Hugh Perry was the fullback; Hugh McElhanny was the broken-field runner; John Henry Johnson was second halfback -- he was also a pass catcher. He was a hell of player.

Did you ever play in school?

Sure, I played at Trinity. I was a left halfback. I was in the defensive backfield as well; we played both ways back then. It was really an hour game back then: back and forth. Now with all these TV commercials it's a three-hour game.

Where you any good?

Very good. But then I went from the Trinity school in the eighth grade, in the ninth grade to the Hill School in Pennsylvania. The coach there was a knucklehead who transferred me to fullback without ever giving me a tryout as a halfback. That happens to a lot of kids in sports, which is what I hate about coaches.

So at an early age the powers that be were out to get you.

Oh, yeah. They got me. They do that with a lot of kids. Bad coaching.com, it's everywhere.

Any great achievements on the field?

Not really, we mainly lost. We were not the world-shakers. We were a small team, but we were fast, and we had some talent.

What does the game do for you now that other sports don't?

I like that it's a team sport, that you have these 11 guys in the huddle all looking downfield together. It approximates the conditions of war, in a purely abstract sense of a team unified trying to gain land against another team. It has a very primeval feeling to it.

The uniforms, the helmets. I love the helmets. When I was a child they reminded me of the Greek helmets, of the Greek and Trojan wars. That's part of the thrill a young boy feels toward it. I remember putting on that helmet and feeling like a superhero as a kid.

When you were in Vietnam were you able to follow the game?

No, I pretty much lost track, the reports came in so sporadically. I missed the Namath-Unitas Super Bowl, which was too bad.

Do you have any great Super Bowl memories?

My best Super Bowl memories would have to be the Dolphins and the 49ers over time. I loved watching Miami. They were wonderful to watch, like the Niners in the '80s and the '90s. Whenever the Dolphins got the ball in those two seasons -- they had that one unbeaten season [1972], every time they got the ball the first series they scored -- they marched down the field like a machine. No one could figure out a way to stop them. They could pass, run inside, run outside. Don Shula was a genius, and he ran that team, I guess you could say, like a war machine.

So the Dolphins wiping out Minnesota in the early '70s, the 49ers beating Cincinnati with that catch [1989 Super Bowl]. I love them beating Denver, 55-10 [1990]; that was wonderful to watch. I love them beating the Chargers [1995]. And more recently, in terms of tension, the Packers being upset by Denver [1998] was exciting. I loved that game. That was the most exciting single Super Bowl I have seen in a long time.

Basically, like most people, I love the underdog thing -- that makes it happen for me.

Where were you for "The Catch" [49ers quarterback Joe Montana's last-minute touchdown pass to Dwight Clark to beat Dallas in the 1981 NFC Championship Game]?

I didn't see that. I was in Italy writing "Scarface."

What was the most exciting thing about this season?

Well, it's funny. The Niners collapsed; bad management -- really bad management. I gave up early with them. The most exciting things about this season were the Rams and the Colts, the emergence of the Titans, the Jaguars -- all the underdogs have come up this year. Especially the Rams -- Kurt Warner is amazing -- and the Colts. It's a whole new ballgame. I think Parcells turning around the Jets was great, and this kid Ray Lucas was amazing. I mean that's what happened in our movie. I have always been a fan of Charlie Batch in Detroit. I wish he could have some better luck.

I love the idea that Barry Sanders could retire this year and everyone was predicting disaster this year for the Detroit Lions, and they did all right. It goes to my point that it's the no-names that win it -- it will always be a team game.

I love Doug Flutie. I love the idea of the little guy coming off the bench.

You spent a lot of time with old-timers like Jim Brown making your film. Do you get the sense the game has changed a lot since his day?

It was a different time. These guys were out of shape; they wouldn't train in the offseason -- they'd drink. They had to work odd jobs in the offseason.

I mean, they used to play with no face guards. Bob Sinclair told me about a time he lost his front teeth. He was rushing a punter. The punter kicked his teeth out. No call. The play was over and he was down on the ground looking for his teeth, and he couldn't find them and the ref was saying, "Come on, Sinclair, you want to call a timeout?" He said no, got back behind the line and kept playing.

Sinclair told me when face guards first came out most of the guys were against them. It was this thing of honor, this macho thing. It's amazing there weren't more injuries.

Well, it might have something to do with the fact that today they are 250 pounds of pure muscle moving at 4.6-40 speed.

Yeah, it's all relative, I guess. Now they're much more specialized. Now you have these huge linemen. I wanted to do a shot at one point, a sort of "Natural Born Killers" thing, with Jamie [Foxx, who played the quarterback in "Any Given Sunday"] dropping back in the hole and a big cartoon dinosaur with a football helmet coming at him. That's what I think it must feel like.

Do you ever bet on games?

I bet a lot when I was in my 20s. When I was a struggling screenwriter doing odd jobs I gambled as much as I could. In fact, I gambled more than I could. I was borrowing money from the Beneficial Finance Company, which in those days was charging 25 percent interest on the money, a month -- that's a lot. So I was paying purses of $10,000, $12,000 to these bookies. I was losing more than I was winning. In the '70s it was more of an open gambling atmosphere, there were more of sporting bet sheets out. Even the New York papers used to run all of the lines. Then I won on the Super Bowl. I predicted Miami would slaughter Minnesota. I took the points. But being the last game of the season, the two bookies didn't show up -- they disappeared. They closed up shop. I had bet the house on it, I lost out like $15,000.

That's a nice Super Bowl memory.

I saw the bookie on the street a couple of years later, and I felt like going up to him, but he was big, and he looked like a real Mafia guy, so I didn't want to go mess with him. [Laughs.]

You have kids. Do they play?

I have two sons and a daughter. My older son learned a lot of discipline this year. He's 15 years old, offensive tackle for the junior varsity, going up to varsity. Although he played Little League quite a bit, he prefers football. It's the first team he's been on where he has felt like he's part of a team. He takes great pride in it. It's given him a sense of selflessness, as well as confidence, and courage. It takes courage to play.

-Anthony Lappi, "Any Given (Super Bowl) Sunday," Salon, Jan 29 2000

0 notes

Text

"I'm a freethinker"

Maverick American director Oliver Stone told AFP that the legal proceedings against Donald Trump are "all political" and that the ex-president was a victim of "lawfare" -- when prosecutions are used to silence political figures.

"Almost 100 indictments against the guy… it's ridiculous," said Stone.

"This is all political. They want to put him behind bars, but they're not going to be able to," he added.

However, the 77-year-old director of "JFK", "Platoon" and "Snowden" said that he would not vote for Trump in this November's US presidential election.

"Everyone's corrupt. Russia runs on corruption, so does Turkey. So does the United States. Corruption is a way of life, but they make it into a political issue now," Stone insisted.

But he said he would not be voting for incumbent President Joe Biden either.

"Never for Biden, because Biden is a warmonger," said the Vietnam veteran.

Stone spoke to AFP Tuesday during a trip to Paris to promote his documentary about nuclear energy, "Nuclear Now".

He said he has been thinking a lot about "lawfare" as he has recently completed a film about Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva.

Lula, as he is widely known, was imprisoned in 2018 on corruption and money-laundering charges after several years in power.

The charges were overthrown after an investigation found the judge was biased, and Lula was re-elected president last year.

"The concept of lawfare is all over the world, and it's been used for political reasons, weaponised," said Stone.

"And so that's what they did with Lula. They put him in jail and he got out and he won the election. It was a hell of a story… but people don't know it, except in Brazil."

Stone has often focused on Latin American leftist leaders, with no less than three documentaries about the late Cuban leader Fidel Castro, and one about his friend the Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez, who died in 2013.

Lula, Castro and Chavez were all "humanists", he said.

"They're all great. They're all original, doing the best they can for their country. I think Chavez was motivated by love of country. So it was Castro."

There is not yet a release date for his Lula film, though he has launched previous films at the Cannes Film Festival, which takes place in May.

Stone has often been denounced as a conspiracy theorist for his views on US foreign policy and the assassination of John F. Kennedy, laid out in "JFK" and a follow-up documentary.

He has a simple response for his detractors. "I'm a freethinker."

-Jordi Zamora, Agence France-Presse (AFP), March 13 2024

0 notes

Text

Museum of Modern Art entry for Platoon (1986)

A Yale dropout who worked as a teacher in Saigon and later as a merchant seaman, Oliver Stone volunteered for infantry service during the Vietnam War. He was wounded in combat and earned a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart. After the war, he studied filmmaking at New York University, where one of his instructors was Martin Scorsese, and eventually made his mark as a screenwriter, most notably on Midnight Express (Alan Parker, 1978), for which he won the Oscar for best adapted screenplay. These were the raw materials that went into the making of Platoon, Stone's fourth feature film and the one that elevated him to the first rank of filmmakers. Working from his own script, he told the story of the common American foot soldier in Vietnam, avoiding the larger geopolitical issues of the conflict to focus on what life was like for the war's hundreds of thousands of young "grunts." The film seesaws between the tedium of camp life's daily routine and the shock of sudden, vicious combat, and no other filmmaker has ever captured so viscerally the stark terror of such warfare. Platoon is often melodramatic, even pretentious—occasional traits of this filmmaker—yet here Stone earns the right to such extremes. Whatever the film may lack in narrative polish or psychological subtlety, it conveys the emotional truth of combat itself. It is a generous and openhearted film, one in which Stone keeps faith with his former comrades–in–arms by explaining without ever excusing, by forgiving without forgetting.

-Publication excerpt from In Still Moving: The Film and Media Collections of the Museum of Modern Art by Steven Higgins, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2006, p. 299.

Producer: Arnold Kopelson

Object number: W9470

Department: Film

0 notes

Text

From Oliver's official website

The following is a recent Q&A from my Facebook and Twitter pages.

Q: From Jack Forbes

Oliver, the Yellow Shirts in Thailand want to displace the current Prime Minister, Yingluck Shinawatra, and her Administration, with an unelected "People's Council" and have gone to great lengths to disrupt elections and disrupt commerce in Bangkok to achieve their goals. They demand "reforms" pertaining to elections procedures and perceived corruption, but have little to show for what reforms they wish and what corruption they suspect. The military is, so far, taking a "hands off" approach but has not ruled out a coup. Yingluck is making her case for democracy, asking the protestors to vote and to integrate into the Thai political system to resolve political differences. There seems to be no end in sight and experts believe that civil war is possible for the near future. What is your take on all of this?

Oliver:

My take is as an outsider. I’ve traveled many times to the country and admire their collective sense of harmony in all things. Makes this recent civil strife almost incomprehensible to me. I’m hardly knowledgeable about the complex interior politics of the country, but my feeling is generally ‘the majority rules’—in other words, live with it. As bad as Thaksin may have been and may be, I would imagine time has, and will, softened his impact. Things change. Do not fracture this beautiful country.

Q: From Ben Bracken

It seems everyone successful in film has a connection to some rich people or a rich dad in the film business that gets them in the door. I have neither. I have no money, just the ambition to succeed everyday in a world where 20% of American males ages 25-54 are unemployed. I'm not lazy and will never collect unemployment, so I work everyday at a shit restaurant for $4.95 an hour plus tips (that you never get anyway) and work harder than anyone you've ever met. I have self taught myself to be a DP, an actor, and barely afforded to put myself in school for screenwriting. I don't know anyone famous or anyone's rich uncle to help me get my foot in the door. So, my question to you, Mr. Stone, is a simple one. Would you please hire me? I don't care if it's shoveling the elephants shit on the set of Alexander or getting you coffee. I will still be the hardest worker you've ever seen. I humbly thank you for even reading this as I know you will probably not respond to my question as I've seen the other questions people way smarter than me have posted about you and your work. Either way you're still one of my heroes. Thanks, Ben Stiller

Oliver:

This is a tough question but I’ll try to answer it. Just to keep things clear, I had no strong connections to get me into this business. I wrote my way in, and it took many scripts and much rejection until some of them were read and gradually I was able to find more and more work.

That said, when I actually penetrated it as a writer and then moved, after a few setbacks, onto being a director. I found that many young people and outsiders were vying for jobs as assistants and interns, but that the union rules were pretty strict on this matter, and that the best way in was through the assistant directors’ department. After the union regulations were fulfilled, the producer, production managers, and assistant director would interview new people for roles as assistants and interns. Generally speaking the job is a tough one—long hours—and often takes place far off the set around the trailer camps and various messengering jobs. Often people would be frustrated that they didn’t get enough time inside or close to the set (On the other hand, being inside the set all the time can be—believe me—quite boring and I think many people would be disappointed.).

Perhaps the best way to approach this is to work on low budget films as a production assistant, where one probably gets a lot closer to the action. I worked on a soft porno back in the early 70s in NYC hauling heavy dollies up and down staircases in New York City.

When, and if, we do start up a film, we crew up like a pirate ship or whaling expedition for the journey. At that time the producer/production manager/assistant director make their choices as to whom they want to work with. Sometimes I weigh in.

Q: Ben Norbeetz

Why in many of your films do you repeat certain phrases, ideas and metaphors. "Kiss the snake with no hesitation" was in the doors and alexander and a motif in Natural Born Killers, your close up shots on a single eye was apart of both any given sunday and the doors, the "world is yours" is in scarface and alexander. is there something all of your works mean to say?

Oliver:

Each motif is different and probably for a different reason. I wasn’t aware of the similarities until you brought them up, but certainly, I think the idea of the snake in “Doors,” “Alexander,” and “Natural Born Killers” represents a sensitivity to the issue of fear. That by going through the fear, one finds a courage that was not available before. Jim Morrison was writing about the snake long before we made the film. And of course the analogies of snakes and dragons appear again and again in mythology. Although I walked among many rattle snakes in “Natural Born Killers” and lived through my share of snakes in Vietnam, I’m still not comfortable around them.

As to eyes, I’ve been shooting close ups of eyes for so many years I don’t know which exact mention you have in mind. I think it’s a striking visual. The eye is the window of the soul and often speaks an inner truth to us that is beyond the word. And people’s eyes in general, if you look closely at them, reveal much. Movie stars often have blue eyes, because I think they give more access than brown/black eyes.

As to the “World is yours,” well, that’s a subjective frame of mind, and it can well be true if you believe it.

Q: Patrick Dailey

Please give us some details about the new "Alexander : The Ultimate Cut" blu-ray/DVD. Will it have new features, new transfer, etc. Thanks!

Oliver:

I can tell you the new “Alexander” is 8 minutes shorter and has some structural changes of significance. I think it’s cleaned up. It’s a real final to me. In the 2007 version I was trying to get out all the stuff that I wasn’t able to get out in 2004. And then I was able to look at the 2007 version in various film festivals around the world (San Sebastian, Taormina, and New York.) After seeing it in public like that, I was able to go back and see some of the things that I had added were not necessary—as well as remove some of the complexity that still existed. That’s why I trimmed it. I’m very happy with this new version and it’s definitely a final one. There is no new transfer—not necessary because everything was beautifully transferred the first time.

Q: Attila Peter

Of all the empires which one would you prefer?

Oliver:

Very good question. I think as a Roman it would’ve been very dangerous to stay alive. There seems to have been a poison in the air, and in the capital too many Romans were killing each other. I think in some ways the British Empire must have been perhaps one of the best, at least if you were an Englishman! But not a native. The idea of going to Eton or Oxford, joining the military, or being a businessman when most people around you are ethnocentric, you think of yourself as superior. It’s an amazing illusion—but produced some amazing results.

We’re now living in the American Empire. So you make up your own mind. Many are happy with it and comfortable. Depends on your consciousness of our history. If interested see “Untold History.”

As to the best Empire, I’m not sure, but I think the Mongol Empire of the 13th/14th centuries makes a lot of sense. Although bloody (who wasn’t at that time), they had an amazing degree of intelligence. As tribal nomads and outsiders, they brought to the sense of empire a newness and ability to see beyond parochial concerns. And because they were a small tribe they were concerned about their universality. They truly brought a modern order to feudalism and tribalism, and their influence is still strongly felt today in the East.

I also deeply respect Alexander’s Empire because of his respect for local laws and customs—as did the Mongols—and the fact that he did not loot and rape the place, as the English and Americans, in their benign way, did. So I vote for the Mongols.

Q: Matthew McKenna

Is there a person or persons who have been a major influence on your life?

Oliver:

Huge question. We can talk in the personal sphere or artistic sphere, but let’s say we’re talking of the American political sphere. I’d say Roosevelt and JFK. And in a negative way Reagan, LBJ, Nixon, Bush (father), Bush (son), Truman, and Eisenhower. Without a doubt the U.S. has had its share of awful Presidents who’ve really destroyed what this thing could’ve been after WW2. Please see “Untold History” to understand my feelings. These are people who have directly influenced our life in a very powerful way.

Q: Mary F. Nugent

On behalf of WH Wisecarver: I was on the Capital Hill in 1991 when JFK was released. It was surprising to me the controversy and re-evaluations it provoked amongst my younger peers. In lieu of your recent post on the prohibition of being able to do your MLK movie and the rehash of contrived political thrillers in today’s films, do you see a time when real thought provoking cutting edge films can be made in Hollywood again?

Oliver:

You’re asking a bit of a rhetorical question. Films don’t necessarily have to be cutting edge to be thought provoking. For example, “The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel” (2011) was a beautiful film about older people that really had a point. It wasn’t cutting edge in the sense of what people normally think, but who cares as long as it move you and provokes your feelings and thoughts. I said earlier on another post I really was struck by “All is Lost,” I think that “Blue Jasmine” in its way make you think about people that I knew in New York. It’s a great character study. I think good movies are coming along all the time from abroad, from here, and I wouldn’t dismiss the industry for that. We filmmakers are always struggling to get something fresh and different done. Few of us succeed. But we try.

I think that the concentration on money, as with the rest of the culture, has hollowed out the business. I know that studios are just not developing dramas unless you’re a top of the line director, and they rarely do that without making you compromise. It’s hard to get things great things made in that way. If the directors stick to their guns and develop stuff they really believe in, I think it’s possible to get films made. I know that we have many more markets available to us, as well as different forms of financing, but sometimes you have to assume you’re not going to make much money making a film, and you’re going to live with whatever distribution you can get. So I think it’s a very harsh playing field—but good stuff does get turned out because people are ‘burning’ to tell a story. I sometimes feel we’re the like that medieval acting troupe in Bergman’s “Seventh Seal.”

Q: Nathan Paul

Oliver as a filmmaker myself I come across a predicament often behind the camera. Do you ever sacrifice continuity of a shot for your vision?

Oliver:

Yes, I often do. The logic of the technician is often in conflict with the heart. Especially as the sun is going down and fast decisions have to be made. Best to make those decisions early in the day.

But as you can see from my editing, it’s sometimes discontinuous, and probably far more interesting because of it.

Q: Matt Higgins

How is it that you were able to turn your horrific experience of being a combat soldier in Vietnam into something productive- producing great films that brought Vietnam into the focus of the American mainstream, instead of becoming one of the many casualties of PTSD?

Oliver:

Well, I probably did have my share of PTSD, but I didn’t know it at the time because it wasn’t called by that name. I think that terminology started in the late 70s (not sure). I think the fact that I met a good woman who helped me reintegrate, and I did gradually join back into a film school at NYU and was inspired. I think willpower played a role in it. There was much rejection. Remember, it took 10 years (‘76–‘86) from when I wrote “Platoon” to when it was actually filmed, as well as 10 years (‘79–‘89) for “Born on the Fourth of July.”

This is the point of the artistic journey isn’t it? To take the ordinary and the oppression that’s sometimes served up to us, and make of it something celebratory.

-Archived version here from Feb 13 2014

#oliver stone#official website#q&a#social media#facebook#twitter#jfk#alexander#movie business#film business#ptsd#motifs#themes#artistry#thailand

0 notes

Text

The Oliver Stone Collection

Long before the advent of DVD, the name Oliver Stone was already synonymous with the term director’s cut. Now, thanks to the wonders of digital technology, the voluble director of ”Wall Street,” ”JFK,” and ”Any Given Sunday” has found the perfect place to unload his vast cinematic attic: the ”Oliver Stone Collection,” a mammoth DVD boxed set loaded with extra scenes, supplemental research, and plenty of conspiracy theories. Recently, the natural born rabble rouser sat down with EW to look back (and to the left) on his collected works — including the mysteriously MIA ”Platoon.”

So where’s ”Platoon”?

You know, MGM stiffed [Warner] on ”Platoon” and ”Salvador.” They had a big fight. I don’t know much, I just know there was a lot of bad blood.

Kinda nice having people fight over your work, huh?

You could say I’m glad they have some library value, although a lot of people don’t remember ”Salvador.” I know this because the people at MGM said, ”What is it?” But I did a commentary for it. I think [MGM] is going to [release ”Salvador” and rerelease ”Platoon” on DVD] midyear.

Are you a big DVD fan?

Any form of preservation is good. And there are so many worthy films they can’t keep up. Museums do good work, of course, but the commercial motivation is the best motivation.

So what version of ”Natural Born Killers” [the R rated version is in the set; the unrated director’s cut is available from Trimark] — and of all your movies, for that matter — do you want the public to remember?

I’m not that picky about it. It’s an ongoing process. Think about books: Writers go back to them at various stages of their lives, so there are earlier editions, later editions. I’d never have released a film theatrically without having approved it. So I’ve never had a problem with a studio [cut]. I did have huge problems with the MPAA…. I was okay with the R cut [of ”Natural Born Killers”], but I prefer the director’s cut. I accept the theatrical cut because I made it — nobody replaced me.

Well, you certainly weren’t stingy with the supplements.

I wanted to be thorough because my films are often criticized for accuracy, and I’m trying to point out that a lot of research went into them.

So is this the last word on Oliver Stone, or do you foresee future editions?

Well, look at ”JFK.” It’s enormous [at 205 minutes]. Other people are talking, people who are very knowledgeable in [the Kennedy assassination lore], even more so than I am, and that opens up the possibility that, yeah, there ought to be [another edition]. Probably in 2010, there will be some new DNA evidence. [Pause] If they’ll let it out.

Speaking of classified information: You were a writer on the original ”Conan the Barbarian,” correct?

I wrote a very elaborate script. Paramount saw it and flipped out. It [would] have cost $50 million [to make] at that time. I wanted Ridley Scott to do it. But he chose ”Blade Runner.” And that set us back. I really always strongly felt it could have been a Bond series, 12 pictures, with a great central character if they’d kept the quality up. Ah, it was an outrageous script. I always get approached about remakes.

-Scott Brown, "EW sits down with Oliver Stone," Entertainment Weekly, Feb 9 2001

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ten Minutes with Oliver Stone

Saturday March 16. It is 1 p.m. In a little over an hour, we have a meeting with Oliver Stone. The American director kindly agreed to answer our questions. The instructions are clear: three questions maximum. At 1:40 p.m., five of us are shown to a small room filled with chairs right next to room 5 of Flagey. In an atmosphere intended to be as informal as possible, Mr. Stone spoke to us about his latest documentary, Nuclear Now, his relationship with documentaries, journalism and above all, the Original Soundtrack!

The BO: Hello Mr. Stone, thank you for agreeing to answer our questions

Oliver Stone: Hello.

In short, we are a media that deals with music and Cinema. Sometimes we try to make connections between the two. We have prepared 3 questions for you. Our first question is related to your coming to this festival, why is it important for you to be there at a festival like Millenium?

Why is it important that I'm here? Because I want to sell the idea of nuclear energy in Europe, particularly in France, Belgium and Holland. France is committed, and Holland and Belgium are favorable, but I would like to see a little more and for it to go faster. You are important countries. Small, perhaps, but you have a mind. You have a big impact on the world. It is important for the world to have nuclear energy. We don't have enough. This is really a problem. People don't think about nuclear power, they have, in a way, forgotten its existence. It's interesting, the Americans say: "Yes, nuclear power, we tried that." Saying that somehow implies that we missed. But we didn't fail, it worked. This is what I'm trying to correct: the impression that nuclear power is a failure. This is very important work, scientific work. But scientists can't do that job, so I do it, as a filmmaker, as a writer. You know, people probably don't care, a lot of people actually don't care but so what? It's important! This is what having a conscience is. If you have a conscience, sometimes you do the right things because you have to do them, right? Like going to your grandmother's funeral, for example. [Laughs] Just kidding, I loved my grandmother very much.

It's interesting that you talk to us about that, we notice that in many of your films there is this documentary aspect. What do you think is the role of documentaries? Why do them? Why are they important to you?

That's a question that would require a very long and complicated answer. I'll give you a short answer. When I make a film, I have to create everything. I have to hire actors, I have to create the set, I have to hire extras, I have to write the dialogue to some degree, light the room, shoot it, etc. Look at us now, we're talking. This is a documentary! Basically, it's much simpler. I don't have to do any of the things I mentioned. I just need to find a real person and talk to them. A documentary gets straight to the point. It goes faster. For a film, it's a minimum of a year, or even two years of time. People don't understand that.

Film critics know nothing about current events. Very few of them are aware of what is happening in the world because they never leave their cinemas! Therefore, they're stupid [laughs] when it comes to what is happening in the world. If you're doing something that requires being a little politically sensitive, they often don't understand it. They can't understand it, because they don't read anything. For example, there was a film - I won't mention the name - which came out a few years ago, which had great reviews, an Oscar nomination, everything! And it was a fraud! Everything was wrong. It was a lie from start to finish, about this certain woman. [I suspect he's referring to The Post here, Spielberg's movie about Katherine Graham].

This is something that's also true for documentaries, you know. People see 20 Days in Mariupol and say, "That must be reality." That's not how it works. That's the problem. I've never had a documentary that wasn't controversial, because I go out there and try to tell the fucking truth. It goes against the established order in my country, what we call the mass media or corporate media. Call it corporate media because corporations are the most influential. Be careful with them. You're journalists and you'll all join this type of media because that's where the money is, which I can understand. Being a freelance journalist is much harder, and even harder when you're young. So become corporate journalists for a few years. They'll try to brainwash you but don't get fooled. That's the best advice I can give you.

Finally, I've already told you a little about the concept of our site and how we deal with cinema and music. So we wanted to know what, for you, is the role of music in a film?

You asked me three good questions and they're all extremely important. They deserve very detailed answers. I could talk about this one for hours. It's a fascinating subject.

What is the role of music in films? Obviously, some directors don't want music and therefore use it minimally. Film criticism at the moment likes minimalism. People like Ken Russell come to mind. He exploded his films with music, revealing himself. Baz Luhrman too, and there are many others who like to use a lot of music. I honestly have to admit that sometimes I'm like that too.

Music is a vital part of the lives of men and women. It's really an important part of our life. I see music as another camera, a sort of secondary entry point. There's music all the time. Now that we're talking, I hear some. Although we're having a very prosaic conversation. It doesn't really seem like there is any music. Perhaps, in the third question, the idea arises: how would Beethoven have answered this question? Ta da da da da dum [laughs] Do you know what I mean? It makes a huge difference!

I can't precisely tell you how music affects a scene. Without music, of course a scene is drier, but maybe some people prefer it that way. They want it to be honest, too honest. I think a film is partly manipulation. We're trying to influence the audience to think a certain way. That's what a film is all about, influencing the audience to believe it. To achieve that, I see no problem in cheating as much as you want. I really don't see a problem there. Either way, we still cheat.

I've had the chance to work with five or six composers in my career, some of them very good. I think I was very lucky to come across them. The last one I worked with, Vangelis, was excellent. He did the music for Alexander for me and also for my latest film Nuclear Now. This is his last work, I believe. He's deceased now. It’s a very subtle soundtrack. Maybe if you see the movie, you can hear it!

While Matteo explains to Stone where the Manneken Pis is, Sam tries to speak English and Ethan greets the director's wife. So an interview ends that we won't soon forget.

-"Ten Minutes with Oliver Stone," La Bande Originale, March 25 2024 (translated from French)

0 notes

Text

My Great Movies: Platoon (1986)

A very good friend of mine once told me that “Platoon”, writer/director Oliver Stone’s Best Picture winner (1986), an intense immersion into the Vietnam War, was held back from being a great movie solely on account of Charlie Sheen’s lead performance as Pvt. Chris Taylor, the film’s protagonist, whose performance was merely average. I could not say I agreed. “Platoon” is my favorite war film which, frankly, seems wrong to type. My favorite war film? It’s like saying “The Reader” is my favorite Holocaust film, which it is, because not only could you debate the veracity of it being a "Holocaust film" but because, well, are you allowed to have a “favorite” Holocaust film? Or a “favorite” war film? Are those sins?

The late Samuel Fuller, a maverick who directed his fair share of war movies, once dismissed the majority of them as being “goddam recruiting film(s).” This is in stark contrast to that guy named Steven Spielberg who once said: “Every war movie, good or bad, is an antiwar movie.” Really, Steve? You think so? Did you know that I once knew someone who upon seeing “Saving Private Ryan” said to me (honestly): “That’s the only movie I’ve ever seen that made me want to go to war.” I wasn’t even sure how to respond. I’m still not.

I do not mean, not in any, way, shape or form, to disparage those who risk their lives in the American armed forces. God, no. Those men and women are approximately 925 million times more brave than I could hope to be in my wildest dreams and I thank every single one of them for what they choose to do every day. But I think so many war films - and this is certainly what Fuller was driving at - glorify the entire ordeal, whether they intend to or not. And “Platoon”, more than any other movie centered around war I have ever seen, was the one I have always felt most actively and effectively de-glorified the experience while still actually being a film, a superb film, not merely a slogan.

“Saving Private Ryan” has that gargantuan D-Day re-enactment near its start, sure, that is brutal and real and horrifying but that is not actually how the movie begins, remember? It begins with a shot of the American flag flapping in the wind. “Platoon”, on the other hand, opens with Sheen’s Chris arriving in “the ‘Nam” to the sight of body bags and then that creepy guy walking in the other direction staring at Chris with that creepy smile and, like it or not, the opening to a film so often establishes its true tone and the true tone of each of these films can be found right there in those two moments. Old Glory versus Creepy Guy. Tell me, which one’s anti-war?

The Charlie Sheen of then was an actor primarily of laconic disinterest. Whether or not he was always supposed to be disinterested is another matter, but that is what he tended to project. The disinterest he displays early in "Platoon" is right on the money for the character. There is that scene where Chris and Crawford (Chris Pederson) and King (Keith David) are cleaning out the latrines and only at this point do we get any kind of handle on why Chris has ended up here. Dropped out of college. Volunteered. Asked for infantry, combat, Vietnam, “I figure, why should just the poor kids go off to war and the rich kids get away with it?” But it’s Sheen’s delivery that renders this revelation so striking. His natural disposition makes it sound so insincere, so false, so “This is what I’m supposed to say.” He knows the words, not the tune. He even smiles and laughs a little - at himself. "Can you believe that?" King calls him a “crusader” but I think that we think that Chris knows better.

Famously, Oliver Stone initially wanted to cast Sheen's brother, Emilio Estevez, who turned down the part at which point Stone offered it to Sheen. It's debatable, certainly, that Sheen is doing anything much beyond playing a part squarely in his wheelhouse. Frankly, there is not much difference between Chris Taylor and that guy in the police station in "Ferris Bueller Day's Off" (another 1986 release) who flirts with Ferris's sister. Their demeanors are very much the same. Strange as it sounds, this is a good thing. He mimics the stance of an idealist but he's just fakin' it. He's tethered to nothing.

Remember when the platoon is being sent out on “ambush” into the foreboding jungle at night and Johnny Cash is ominously strumming on the soundtrack and Chris finds himself talking with Pvt. Gardner, a “lard ass”, who shows off a picture of his “Lucy Jean” back on the home front? “She’s the one for me, that Lucy Jean,” proclaims Gardner. Sheen’s reply is classic: “Real pretty. You’re a lucky guy, Gardner.” It’s the way he says it. Total disinterest. Whatever. Whoever. You know we're about to go into the jungle, right? Chris writes his grandma at home, this much we glean from his voiceover. Why not his parents? The movie never says. The movie, in fact, doesn't say much of anything movies of this sort typically say to not only drive home points but to give the audience its normal bearings. Its intention is to disorient.

Consider that opening title card: "September 1967, Bravo Company, 25th Infantry, Somewhere Near The Cambodian Border." Key word: Somewhere. We don’t really know where they are. We don’t really know what they’re doing. They don’t really know where they are. They don’t really know what they’re doing. You want guideposts and mile markers? Look elsewhere. At base camp we find Chris digging a hole and expressing this very sensation via voiceover: "I don’t even know what I’m doing." His face shows it. Gone. Disconnected. Logistics and strategy are almost irrelevant. Reason seems useless. "I don't think I can keep this up for a year, grandma. I think I made a big mistake coming here." Yeesh. That line gives me the willies, and if the actor had gone for affect on the words, it wouldn't have been as chilling.

Chris doesn't really understand what he's doing, perhaps, until the film's halfway point. This is when platoon enters an ancient village and Chris finds a kid hiding and pulls him up and out of his hole, screaming all the while, and Pvt. Francis (Corey Glover) tries to calm him down: "Be cool. They're scared, man." Chris erupts: "They're scared?! What about me?! I'm sick of this f---ing s---!" Then he really loses it, aiming his machine gun at the kid's feet, spraying bullets, ordering him to "dance". Yet, it's almost like enlightenment. He could kill this kid (and, terribly, Kevin Dillon's unhinged Bunny will do just that) but he doesn't. He walks away. It's a crucial moment. And Sheen is scary convincing in that moment. Later, he helps a village girl being mistreated, shaking his head, disbelieving, intoning to his fellow soldiers, "You just don't get it, do you?"

For much of the film Stone has presented us the simmering rivalry between Sgt. Barnes (Tom Berenger) and Sgt. Elias (Willem Dafoe) and it is here, in the village, in a sort of mini My Lai, that Stone serves up one of the intense, terrifying passages ever captured on film in which Barnes coldly, quickly, matter-of-factly makes a decision that takes the heart right out of you. Later Barnes blathers about when men don't follow orders "the machine breaks down" but, in reality, the machine breaks down right here. Elias confronts him. Afterwards, he will file a report. The movie stops paying attention to the war with the Vietnamese. That's immaterial. Now it's about Elias vs. Barnes. And Barnes will kill Elias. And Chris will kill Barnes.

Chris came to Vietnam, despite what he may have tried to claim, for no good reason. Yet his friendship with Elias, and others, helps him to figure out his reasoning and to gain ideals and so when Elias is gunned down by Barnes it is those very ideals which push Chris to retaliate and that moment between he and Barnes at the end is not one of triumph, not some cinematic precipice that has been scaled, but disillusion, all the ideals stripped away. "All the humanity goes out of you." That's what Dale Dye, an ex marine, the film's technical adviser, says at one point on the commentary track.

Perhaps "Platoon" is best summarized the morning after the last gigantic attack when Pvt. Francis finds himself alone and uninjured in a foxhole. He looks around. No one's watching. This is his chance. He takes a knife and thrusts it into his leg. When we catch up with him again he is laying on his side on a stretcher, as if it's a beach towel in St. Tropez, smoking a cigarette, calling out to the also-injured Chris across the way "We two-timers, man!" meaning that because they both have been wounded twice they get to go home. "Saving Private Ryan" ends with, again, the American flag flapping in the wind. "Platoon" ends with a guy jamming a knife into his own leg. Tell me, which one's anti-war?

I re-watched "Platoon" for the first time in many years for, I think, an obvious reason - that is, to prove to myself that this current bonkers, F-18 Charlie Sheen ("The proof's in the eyes, man!" is what Chris says of Sgt. Barnes and which might be used to describe present day Charlie Sheen) could not assuage the power of my favorite war film. He doesn't. On top of that, I still think the Charlie Sheen of then gives an above average performance and, most significantly, it still doesn't make me want to go to war.

-Nick Prigge, Cinema Romantico, Mar 14 2011

1 note

·

View note

Text

BFI Interview

Mark Lawson: Welcome to the Guardian interview with the three-time Academy Award-winning director and writer Oliver Stone. We're going to talk about his work tonight, which over the last 40 years has dealt with America's critical emergencies, from the Kennedy assassination to the Vietnam war, to Watergate and the Nixon years, to most recently, with World Trade Center, the 9/11 attacks. Welcome, please, Oliver Stone.

We'll talk about the films in a moment, but the first thing that struck me on the way here is that tomorrow, after nine years, the report into the death of Princess Diana is published in London, addressing all the conspiracy theories - was she murdered, etc. And Oliver Stone flies into London the night before? Are we supposed to believe that's a coincidence?

Oliver Stone: I believe I was told part of the revelation tomorrow. What I had to do with it you'll find out. What was more shocking to me when I arrived today was, the first thing I saw at Heathrow was a banner headline saying "Strangler loose in Ipswich". I thought, how British. Jack the Ripper, Hitchcock's Frenzy - it was kind of a throwback.

ML: I mentioned in the introduction that you've dealt with the big American political subjects from Vietnam to 9/11. There's one gap so far, which is Iraq and Bush. Probably for a lot people here, the dream next film from you would be Bush or Iraq, or both. Is it going to happen?

OS: That's a very flattering comment because I feel World Trade Center is an opening for me into this world. And I really am interested in the "post" period, the 9/12 on. I'm not sure the answer lies so much in Iraq, I think that's a result. For me the answer lies in the interim step, in Afghanistan. I think there's a lot of light to be shed on the nature of that war, how it came about militarily and politically, and also the nature of the war with Pakistan, India and Iran. It's a great subject matter. It leads to Iraq but that's the third phase. And there are already many movies about Iraq in terms of the internet and documentaries - in a sense, it's been usurped by television, as 9/11 was, to a certain degree.

ML: Before we talk about World Trade Center, do you know what the next film will be?

OS: No. It's the same thing for any film-maker who works at it. It's a period of uncertainty. We've been developing three or four things. We do a lot of work in research and development - we hire, we write screenplays or have writers write them; sometimes the screenplays take a long time, sometimes they're quicker. You need an actor, a budget, a studio. It all has to blend; it really is like an experiment. Nine out of 10 things do fail, or four out of five. So it's that period right now and it's a tough period, but we work just as hard doing nothing as when we're filming.

ML: We're going to start with the most recent thing you did, World Trade Center, the story of two men from the New York Port Authority Police Department caught in the collapsing World Trade tower.

[runs clip]

ML: I think that film surprised a number of people who've followed your career. As you know there are numerous books of conspiracy theories about 9/11: the American government did it, Israel did it, it wasn't a plane that hit the Pentagon and all the rest of it. But you've pretty much gone with the official facts of the story.

OS: We followed strictly the story of these four people - two husbands and two wives. Their story is corroborated. We also had 40-50 rescuers on the film who worked there. We're dealing with facts here, authenticity, we're dealing with what we know. Eyewitnesses would tell us, "This happened that day." I talked to John McLoughlin and Will Jimeno and their wives many times. I don't think they ever expressed to me even once any opinions about politics or Bush. It wasn't about that. In fact, John, because he'd been at the 1993 bombing at the World Trade Center, all he said was that in the confusion that day, he thought it was a truck bomb. It never occurred to him that it was a plane. And to the end, that's what they thought. There's a wonderful moment when Will Jimeno comes out of the hole and says "Where'd the buildings go?" They didn't know. If you're operating within the parameters of these 24 hours, you must adhere to what they know. This is a subjective movie - it's seen from within, from their point of view. But it's also from the point of view of their wives, from without, through the television, so it's subjective and objective. It would have been wrong to go to politics. Plus, we had a lot to do - there were three rescues, devastation, survival, life in the suburbs amid the worsening news, all this in 24 hours. You have to understand the tension - two wives at home realising that there would be no survivors. That's a great story in itself. Then there's the marine who rescued them, that's another great story. What time do you have to cut away to other things, much less want to?

ML: I understand that. You're entirely true to the story, but if I'd had to guess which aspect of 9/11 you would have chosen to dramatise, I don't think I would have chosen this. It's the one optimistic part of the story - that some people did survive it.

OS: There were times in the 90s when things were so prosperous… I mean, when Reagan was still around, I made Salvador attacking the Reagan administration in Central America. Perhaps I'm a contrarian. It seems to me 2006 is a far darker time than 2001. Those of you who remember that day would have seen how united the world was - the world was with America, had great empathy with America, and did again, maybe not as much, for the war in Afghanistan. But that has all changed. Now we have serious problems - more deaths, more terrorism, more constitutional breakdown in my own country. It's a disgrace, what's happened. And that's much more serious to me than the 2001 was-there-a-conspiracy-or-not. I don't know enough about it and I'm sure there's a lot of leaks and messy stories, but I've been through these arguments. But al-Qaida claimed they did it, over and over again. They claimed the credit, and the motive is very clear. They succeeded in creating a panic, a mental instability in the world and that had tremendous consequences because it was fuelled by George Bush's administration's reaction. So they've won. It's the opposite of the JFK killing - there you had a man, an uneducated, single guy who said, "I didn't do it. I'm a patsy." He disappears with the Dallas police for almost 48 hours, all his transcripts are destroyed, or are missing, and he's killed. It is the opposite of this story. It's a Reichstag fire kind of story. There's no motive, and who benefits? This is the key question and never gets addressed by the press. They always follow the scenery - that's what Ruby and Oswald were. I always say follow the money. Who benefited, what was the motive to get rid of John F Kennedy? I think there's a big difference. So why waste time with conspiracy theories? If you're going to politics on this issue, go now. But we don't know everything. If I'd made a movie in 2004 about the politics of the Bush war, I'd be shamefaced today because there's so much new information that we didn't have in 2004. Every month in the US there are about 10 books - [Bob] Woodward['s Bush at War, etc], The 2% Solution [by Matthew Miller], The Looming Tower [by Lawrence Wright]; every book has deepened my awareness of what really happened and it's not so simple as going after Osama bin Laden. If I make a movie - and we're not journalists, we're film-makers and dramatists, we have to look for the overall meaning and pattern of an event. That takes time.

ML: But it seems to me you are moving towards that film.

OS: Don't rush in where angels…

ML: The reason why I chose that clip from World Trade Center was that another surprise for me when I saw it was that, when I think of an Oliver Stone film, I think of the huge expansive camera movement, reminding us how wide the screen is. This was very, very different.

OS: This was a very tough picture to do, as hard as I've ever made. The lungs alone took a beating. But then you're working with two men in a hole. You have two actors - Nic Cage hasn't been this quiet in a long time. You basically have half a body and a head - it's a pickle in a jar. It's not easy. And Seamus McGarvey, our Irish-Scottish DP, lit this thing - you could see the expression on Jay Hernandez's face, but this was a very dark hole. It's basically a conversation between light and dark, because then we'd cut to the suburbs. We timed it so that you had 10 minutes in the hole the first time -very dark, very cold - then out to the suburbs where it was a really beautiful day, then back to the hole; eight holes with diminishing time periods from 10 minutes down to about two or three minutes. But our biggest problem was the third act, because once they're rescued by the marines - I don't know if you've all seen the movie…

ML: You've just given the ending away.

OS: There are three rescues in the movie - the marine, Will and John, and each one was a big number in itself. It took five hours to get Will out. People think that when you see somebody it's easy to rescue them but on the contrary, it's even more difficult; people can get killed because the spaces are so dangerous and narrow. We wanted to show the heroism of the first responders - it was their job but they went into those positions and risked their lives. And it becomes more than a story of two men, it's the story of collective effort.

ML: Let's take a look at a second clip. We're now going in chronological order, starting with Platoon.

[runs clip]

ML: I'm interested in the shape of your career because there had been work before Platoon - there were screenplays and some directing. But in 1986, when you were 40, that's when your career really seemed to begin and you became a director. Was there something that happened?

OS: Yeah, I think I got angry and fed up. I had done Midnight Express, Scarface and Conan, but I really was a director at heart, and I wanted to break through. I'd had two failures up to then, two horror films. They were similar in theme, actually, and I vowed never to do a horror film again. Jamais deux san trois. It would be a disaster for me to do a horror film - I'm not a natural born sadist, actually, and I think you have to be to do a good horror film. You have to scare the shit out of the audience, you have to really want to. I don't know if I could. 86 was a banner year.

ML: You'd served in Vietnam. Had you always known that that would be a big subject for you as a film-maker?

OS: It wasn't made, you know. It had been written 76 and turned down for 10 years. It was a bit of a stale joke. Frankly, when I got the opportunity from an English producer called John Daly… he actually read both scripts, Salvador and Platoon, and asked which one I wanted to do first. Which of course to a young film-maker is like a dream. I picked Salvador first because I was so convinced that Platoon was cursed - it had been started so many times but not got made, so I thought it was not going to happen. It was [Michael] Cimino on The Year of the Dragon, which I wrote with him, who convinced me to pull it out of the closet and go with Dino De Laurentiis, who reneged on his promise. I got another lawsuit but I got it back by the skin of my teeth. And then John Daly walked into my life. God bless the English for making those two movies - they were made illegally, almost fraudulently in Mexico. Salvador was made on a letter of credit issued to an Arnold Schwarzenegger movie - on our slate on Salvador, you can read the word Outpost, which was supposed to be the movie he was doing. Years later, of course, for other reasons, the banker was indicted, the letters of credit were questioned and so forth. But I do think you need government tax help - Britain benefited enormously from this. I don't know what's going on now…

ML: It's in the balance at the moment.

OS: You had a great system for a while.

ML: One of the subjects of Platoon and also Born On The Fourth of July is the number of people who were destroyed by the Vietnam war - the suicide rate being higher than the death rate for example. Did you ever come close to being destroyed by it?

OS: I'm very lucky that I got to make three movies about it - I think that helped enormously. I think there are a lot of successful Vietnam veterans in civilian life who are doing very well on the surface but are very bottled up inside. People who killed people, who killed civilians…Vietnam was a charnel house, there was a lot of indiscriminate killing, probably more so than in Iraq. But that's the nature of war. Platoon is fundamental, it's almost biblical. I was in three different combat platoons, and looking back I have to say there were people who were predisposed to kill anything, and other people who are predisposed to restraint, and it's not an easy equation because there are times when you are under pressure and you kill. It was a bit like a western. And of course, there are the kids who fall in the middle, like my character, the Charlie Sheen character in Platoon. Sometimes life is that way. And the kids in Iraq - who I hear are better soldiers than we were, and there are more Christian-trained and born-agains - they're all encountering this fundamental problem now. Their hatred of the enemy has reached the point where many of them hate the civilian population and they don't know the difference any more.

ML: Do you get angry when you look at people in America, from the president downwards, who got out of the war?

OS: I am beyond it. 2002 was the year I got upset. He was moving troops to the Middle East before the UN resolution. Now they're re-examining that whole period and the Colin Powell speech, but there were troop movements before Powell's speech. Once they moved there, you knew something was going to happen. And [former White House anti-terror adviser Richard] Clarke and various people have verified it, that Bush had the thing on his mind, he wanted to go to war, it was a given. It angers me greatly because when Bush went to Vietnam just four weeks ago, they asked him, "What did the Vietnam war mean to you?" And of course, this is the guy who sat out the war, draft dodged, as did Cheney, six or seven times. And he said something to the effect of, "I think it proves that if you stick in there, you'll win." That was his lesson from Vietnam.

ML: We move now to an earlier president, John F Kennedy. This clip I've chosen, it's part of a very long scene, and is my favourite Oliver Stone scene. It's a speech which I think is one of the great speeches in cinema and I want to talk to you about the writing and the directing of it. But here it is, from JFK.

[runs clip]

ML: The reason I chose that is I want to get at this business of getting what's on the page to what's on screen. It's an enormously long and complex speech, and it's exposition, which is what people always say you can't do in movies. So can you talk a bit about planning that visually?

OS: It was a 12 to 18-minute speech. I offered it to Brando, and I'm glad he didn't do it - it would have taken 30 minutes. It's actually two scenes, it was really complicated editing. Jim Garrison sees Fletcher Prouty in the middle and at the end. We ended up collapsing that in the middle. The secret, I think, to why many people have liked it is not only John Williams's music, but it's coming at the end of the first half. In Holland, there was an intermission after this scene so it gives you time to absorb this. Really, it's about Garrison going from this small, local investigation in New Orleans and jumping up another level - a quantum level leap. He never met Fletcher Prouty but he met a man similar to Prouty, who told him a similar story. But the man vanished. He's no longer operative. Fletcher was somebody I met separately. He'd written several books about it, including The Secret Team. He was chief of special ops, one of the key guys in the cold war. He was involved in at least 25 to 50 CIA missions in Tibet to Guatemala, everywhere. He supplied the hardware - the CIA didn't have the military weapons at the time. Something smelled bad to him that year and he quit, and he was discredited by the administration and by journalists, not for any correct reason. They spread the usual disinformation about him and Garrison. He told me the story from his point of view. I'll never forget that day.

ML: How carefully was it planned in advance?

OS: This was shot on the fly. We did it in two, three days. It was the last scene in the film. [Donald] Sutherland is the fastest talking actor in the world, he's very authoritative at that speed. It was a hell of a lot of dialogue, but I wanted to get it all in. Because Garrison is learning it as we learn it. And Garrison's jaw is dropping, "This is much bigger than I ever thought, how can I go on?" Garrison was the only public official who did anything. It is as a result of his beginning something that we have some records, and those records are invaluable. He also attracted the attention of the private community and they gave him a lot of help. But he could not get all the facts together. I didn't change what Prouty told me - this is based on what he said.

ML: That account in the film is very exciting. Do you believe that that account is what happened, that it's correct?

OS: I don't know who did it but I believe it was a military operation. The shooting, the autopsy, the brain, the Zapruder film - you shoot the guy coming towards you so you get the second shot, the third shot. You don't shoot him going away from you. The pressure's enormous, the sound's enormous and Oswald was not a great shot. And the [6.5mm] Mannlicher-Carcano was a piece of junk. I mean the story was just so ridiculous. The Zapruder film is evidence enough - there are two smoking guns. His head flies backwards, he was shot from the hedge. And they talk about this bullet that hits Kennedy and [Texas governor John] Connally 11 times - it's the most ridiculous bullet in the history of the world. In fact, a British audio group did a test a year ago - this is the English saying this - and said they're 99.9% sure that there were four shots. And the Americans came back a few weeks later and said, "The British are off on this." They always do that. This is a contentious thing, but bottom line: I don't know who, but I know it could not have been one man because too much went wrong at a high level. It was planned, there were a lot of red herrings and misdirections. As Prouty said himself, that whole thing about the military group is typical of a misdirected operation. All this stuff had been worked out in the 50s - you saw this time and again in assassinations in Latin America and everywhere. This is black ops. Who did it? Somebody with military capability. Why? I presented several motives in the film but I can't tell you the answer. But I would say Cuba and Vietnam and the détente with the Russians, with whom Kennedy in 1963 signed this historic agreement on nuclear weapons. That really was potentially the beginning of the end of the cold war. All this had occurred after the Cuban missile crisis of 1962. The Fog of War, as good a film as it is, never mentions why the Cubans were so paranoid about an American invasion in October 1962. Why did they have Russian missiles coming into Cuba? Because they were frightened of our 1961 invasion. There is always cause and effect. Cuba was a big issue and Kennedy was backing off. He was making this new relationship, partly with De Gaulle, with Khrushchev. The world balance was changing. He did announce that he was coming out of Vietnam, whatever contrary evidence is presented. He had no intention of running for re-election on Vietnam, he knew it was a dead duck. So out of these factors, the military-industrial complex, as described by Eisenhower at the beginning of the film, was threatened. This guy was going to win the election in 1964 and the nutcase, his brother Bobby, looked like a 68 potential. This was a serious business, to stop the Kennedys.

ML: You mention Bobby Kennedy. There's a recent book, endorsed by Gore Vidal and others, suggesting it was a mob killing because Bobby went after the mafia.

OS: I know Gore, and I've talked to him about it and we just cannot agree. The mob has no history of doing this kind of thing, except for one time, maybe, with Roosevelt. They seem to be close order killers - they do The Godfather style shootings. This was an organised thing. The mob did a lousy job in Cuba - they missed Castro how many times? The good work they did was with Lucky Luciano in the second world war, when they were called upon, with the labour unions and strikes and stuff like that. But the mafia has never been a very successful ally of the CIA, unless they have some involvement with drugs, with I don't know enough about.

ML: We move on from Kennedy, missing out Johnson, to Nixon.

[runs clip]

OS: The reason I chose that scene was because, certainly in this country when people wrote about it, the blood on the plate was seen as a metaphor that you'd imposed. But I happened to have read The Haldeman Diaries and it was there: there is a scene where Nixon tucks into his steak and he sees the blood. And most of that, those exchanges, is documented.

OS: Anthony Summers actually followed up the movie with a wonderful book [The Arrogance of Power] which never got any publicity in America. Nixon as far crazier than I thought. Anthony, who's a very sound journalist and double-sourced everything, documents these six or seven occasions when, in the middle of the night when he was loaded, he'd declare war. He'd call up Henry [Kissinger] and say, "Send the battle ships to Syria or to Lebanon. We're going to blow them up. I've had it with these people." "Yes, Mr President, they're on their way." And then around eight or nine in the morning, he'd call and say, "Did you send those ships?" And Henry would say, "Well, there was a bit of a malfunction and they're still there." In other words, they humoured him. He got really aggressive at times, especially when he'd been drinking. I'm not saying he was a big drinker but I do think he could not take drinking. But you can't underestimate the man's brilliance. His concept, or Kissinger's, whoever takes the credit, of triangular diplomacy, for instance. In 1950 the smart people knew that China and Russia had a big problem. But we persisted in my country for 20 years to believe in this China-Russia alliance that was going to destroy us, when in fact they were fighting far more amongst themselves.

symbol

00:00

03:12

Read More

ML: We've talked about the camerawork and the visuals, but that's an example of acting. Do you work closely with actors in rehearsal for a scene like that?

OS: We rehearsed it and rehearsed it - I believe in rehearsal - and then we got out. It was one of the last scenes in the movie, so we got out one night on the Potomac on a boat. I think Hopkins is great. He embodied to me the spirit of the man, the irritation. I wish the movie had been released in 2006; it would have had much more success with the Bush administration as a contrast. I think Bush makes Nixon look like St Augustine.

ML: To ears in this country, Hopkins sounded a bit Welsh for Nixon. He doesn't do an impersonation, does he, in the film?

OS: No, but it's about the spirit of the man, and I think he gets it for me. He gets the anger, the love. Nixon was a human being. People expected me to do a hatchet job - I'm not sympathetic to Nixon, I think his policies were bad for America, but I'm empathetic to him. And I feel he did suffer greatly from his inferiority complex and from his mother and father and the Kennedy thing. He was the used car salesman in this situation, and I find it very moving sometimes.

ML: One of the visual decisions you made in that movie is that you have switches of style, so that sometimes we have CCTV footage, black-and-white, etc. What was the thinking behind that?

OS: Much less so than in Natural Born Killers and JFK. I think this film was more reserved. It was a tough film to make - you're dealing with 15 white guys with bad haircuts in suits. There's not much to attract a big audience on this movie, and it didn't. It's mostly talk. To me it's one of my favourite films because it's got so much going on inside. It's a psychobiography of a man. I loved it but it was not meant to be a success. But it still holds up for me.

ML: Apart from Nixon, the modern American president most written about is Clinton. Were you ever tempted by Clinton?

OS: Was I what?

ML: Tempted. I don't mean sexually. I mean as a subject?

OS: Frankly, I think Mr [Mike] Nichols did a great job with Travolta in Primary Colors. It was a hell of a job - it doesn't tell you the whole story but it does tell you part of it. I look at the Clinton administration as a lighter leaf in the storm. I suppose the third one, if I ever did it, and if I survived it to see the pattern, would be Bush Jr. This is a true Richard II or perhaps Richard III story.

ML: But also, Bush Sr would be a good character in that. The relationship between them…

OS: I wanted to do the remake of the Manchurian Candidate. The producer did not want to because it was already under way, it was a conventional script, and it was a remake. And I'd done Scarface as a writer and I'd done it completely differently from the original, tried to anyway. I wanted to make Barbara Bush into the Meryl Streep character, when it was Angela Lansbury. Barbara Bush is the key, she runs the family, and this guy George is the Manchurian candidate. He's basically a very shallow, brainwashed person. And ideologically motivated, the most disastrous thing of all in a political leader - you might as well be Khomeini.

ML: The fifth clip we're going to show now is from Any Given Sunday.

OS: In England?

[runs clip]

ML: As you said, we have no idea what's going on in that and we couldn't tell you the score. But I chose that scene as an extreme contrast to the one I started with. What fascinated me, watching it originally and seeing it again tonight, is how you get to that? How much do you know of what it will look like before you shoot it? And how much emerges in the cutting room?

OS: That scene is what I feel like as a director when I walk out on the set. Sometimes, there's so much pressure and there's so much going on. This is a cut film, very much so. When you have huge infrastructures - you have the stadium, huge amount of extras, the football team who are beasts and have to be fed. You have two teams, you have to do this like a military operation, so you shoot a lot more footage. Platoon was a low-budget film where you picked it out, you shot as much as you could in your head and the scenes were very precise - almost minuets. There were only eight or 10 scenes in Platoon. This is the opposite. This has at least 10 characters and perhaps 50 scenes. So this is the other end of the spectrum - it's definitely an attempt to tell multilevel stories at the same time.

ML: Thousands of cuts in it.

OS: Natural Born Killers was the most I made. That was maybe 3,200 cuts, which was a record I believe. But that was prompted by the style of the movie, it wasn't imposed. This also requires a frenetic style to match the pace of football, which is a rough game and about egos, too. World Trade Center is a quiet film because it's a life and death issue, it's about those two men and how close they come to death, and what makes them survive. Why do they stay alive? Most people would die.

ML: There's one part of the equation that we haven't mentioned at all, which is critics. When you've had a bad time, which you did with Alexander, did it affect you?