Text

Full Chapter: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VWxI5aKkjpA

#asoiaf#asongoficeandfire#agameofthrones#eddardstark#nedstark#varys#georgerrmartin#audiobook#voiceacting#applesanddragons

0 notes

Text

Aegon the Unworthy, A Study in Historiography: Chapter 3 - Plumming the Depths

Previous: Chapter 2 - The World of Ice and Fire

I'll begin with the situation I referenced in chapter two as an example of a "Misrepresentation" kind of unreliable narration.

>Aegon soon filled his court with men chosen not for their nobility, honesty, or wisdom, but for their ability to amuse and flatter him. And the women of his court were largely those who did the same, letting him slake his lusts upon their bodies. On a whim, he often took from one noble house to give to another, as he did when he casually appropriated the great hills called the Teats from the Brackens and gifted them to the Blackwoods. For the sake of his desires, he gave away priceless treasures, as he did when he granted his Hand, Lord Butterwell, a dragon’s egg in return for access to all three of his daughters. He deprived men of their rightful inheritance when he desired their wealth, as rumors claim he did following the death of Lord Plumm upon his wedding day. (—Maester Yandel, TWOIAF: The Targaryen Kings: Aegon IV p95)

The last sentence is the only one I'll examine for the duration of this whole chapter.

First, I want to quickly point out that this criticism comes as part of a group. The group creates the sense that we need not bother looking into the specifics of any one particular criticism, because even if only one of them is true then Aegon IV was a very bad person, and because that general assessment of Aegon is constant with almost everything else that can be read about him. But for now, let's pluck this one accusation out of the group and see how it holds up to scrutiny.

>He deprived men of their rightful inheritance when he desired their wealth, as rumors claim he did following the death of Lord Plumm upon his wedding day. (—Maester Yandel, TWOIAF: The Targaryen Kings: Aegon IV p95)

The accusation is that, following the death of Lord Plumm upon Lord Plumm's wedding day, Aegon IV desired the wealth of men and deprived those men of their rightful inheritance. The first thing I want to find out is who those men were.

A Victimless Crime

Who were the men or man that was deprived of his rightful inheritance?

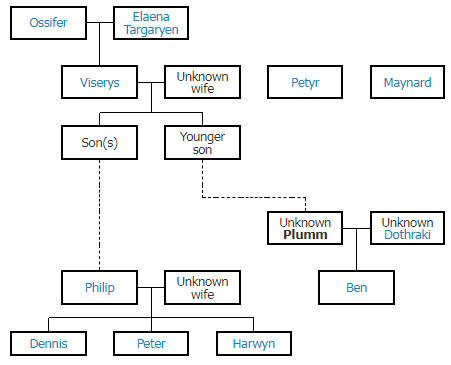

Presumably, the man who was deprived of his rightful inheritance was a son of Lord Plumm, but possibly not, so it's good to check and make sure. When I look at the House Plumm family tree on the Westeros.org wiki, I can see that the name "Lord Plumm" is referring to Ossifer Plumm, because Ossifer was the lord of House Plumm at the time. And since Ossifer is already the lord, he can't be the Plumm who was deprived of his rightful inheritance, because he already inherited the lordship. So the man who was deprived of his rightful inheritance must have been Ossifer Plumm's son, Viserys Plumm.

When I check Viserys Plumm's wiki page, I can see that Viserys Plumm became Lord Plumm next after his father Ossifer. So Viserys Plumm can't be the man who was deprived of his rightful inheritance, either.

Then who was the man or "men" who was deprived of his rightful inheritance? Ossifer Plumm didn't have any other children, and Viserys Plumm didn't have any siblings. What the heck is going on?

The next Plumm in the line of succession after a son is a brother. But Ossifer Plumm didn't have any brothers, either.

There are two Plumms on the Plumm family tree who are not connected to any other Plumms. Those are Petyr Plumm and Maynard Plumm.

When I look into Petyr Plumm, I learn that Petyr Plumm is not a real character. Nothing about him is written and he's nothing more than a drawing in a graphic novel who needed a name.

Since I've read the three Dunk and Egg books, I know that Maynard Plumm is a real character, but he's not a real Plumm. Maynard Plumm is the made up identity of Brynden Rivers, who you might know better as Bloodraven. So Maynard can't be the man who was deprived of his rightful inheritance either, because since he's not a Plumm it wouldn't have been rightful for him to inherit House Plumm.

With all the existing Plumms ruled out as the man who was deprived of his rightful inheritance, I'm feeling lost and confused.

I remember that there was a situation with Ossifer Plumm that was described in King Baelor's section, so let's turn back to page 92 and look at that.

A Scurrilous Rumor

>Elaena outlived her siblings and led a tumultuous life once freed from the Maidenvault. Following in Daena’s footsteps, she bore the bastard twins Jon and Jeyne Waters to Alyn Velaryon, Lord Oakenfist. She hoped to wed him, it is written, but a year after his disappearance at sea, she gave up hope and agreed to marry elsewhere.

>

>She was thrice wed. Her first marriage was in 176 AC, to the wealthy but aged Ossifer Plumm, who is said to have died while consummating the marriage. She conceived, however, for Lord Plumm did his duty before he died. Later, scurrilous rumors came to suggest that Lord Plumm, in fact, died at the sight of his new bride in her nakedness (this rumor was put in the lewdest terms— terms which might have amused Mushroom but which we need not repeat), and that the child she conceived that night was by her cousin Aegon—he who later became King Aegon the Unworthy. (—Maester Yandel, TWOIAF: The Targaryen Kings: Baelor I p92)

Here I encounter two conflicting versions of Ossifer Plumm's wedding night, when Viserys Plumm was conceived. The official version says that Ossifer died after impregnating Elaena, and a rumor says that Ossifer died without impregnating Elaena and that Aegon impregnated her instead.

Both versions agree that Ossifer died on his wedding night at the bedding, that Elaena was impregnated on her wedding night at the bedding, and that the baby that came from that pregnancy was the person now known as Viserys Plumm. The main point of disagreement is whether the real father of Viserys Plumm is Ossifer Plumm or Aegon Targaryen.

But there are more points of agreement than those three that I can infer from this situation. For instance, both versions seem to agree that Aegon was present at the wedding, otherwise the rumor probably would have been discredited already by the simple fact that Aegon was not there. Likewise, both versions seem to agree that Mushroom was present at the wedding, otherwise the rumor probably would have been discredited already by the simple fact that Mushroom was not there, because Mushroom is apparently the source of the rumor. With these recognitions, we can start filling in some of the surrounding information that's missing from the story, and see what we can learn from the bigger picture.

It makes sense that Aegon was present at the wedding, because the bride is his cousin. And it makes sense that Mushroom was present at the wedding, because Aegon is the king and Mushroom is the court fool, and the king could reasonably take the court fool with him to a wedding celebration.

The crucial issue is about what really happened in that bedroom. Now that you know the gist of both versions of the story, how do you imagine that scene in the bedroom played out? I call this kind of analysis Scenes That Must Have Happened. The way I do it is I hold the scene in my mind, and watch what my imagination places into the gaps. Whatever appears is probably what the history book was meant to suggest. Then I ask myself one basic question and hold onto it for the rest of the investigation: Does that suggestion make sense?

The way the scene fills out for me is that Aegon probably weaseled his way into that bedroom somehow to take advantage of the situation. Maybe he snuck in through the window or maybe when Elaena was freaking out about her dead husband Aegon went into the room with her and locked the door behind them. He would probably tell the other wedding attendees later that Elaena just needed some emotional support from her dear cousin on her big day, and that Ossifer was alive and well at the time. With Elaena's husband dead, Aegon probably saw it as an opportunity to slake his lusts upon yet another woman, with no regard for anyone but himself. Being the king, he can pretty much do whatever he wants and everybody just has to do what he says, or else pretend like they don't know what's happening.

Now that I've allowed my imagination to fill in the details, roles and tone, I can consider if the picture as a whole makes sense. It certainly makes sense with Aegon's characterization as a cruel and insatiable glutton, so let's keep this scene as it is and test how much sense it makes by seeing what it means for the original question: Who was the man or men that Aegon deprived of their rightful inheritance?

Supposing that the scene played out mostly as described above, the real father of Viserys Plumm is Aegon Targaryen. And if the real father of Viserys Plumm is Aegon Targaryen, then Viserys Plumm can't possibly be the man who was deprived of his rightful inheritance, because Viserys Plumm did inherit House Plumm.

Unless . . .

When the historian says "deprived men of their rightful inheritance", could he mean the thing that the men were deprived of was the rightfulness of the inheritance, rather than the inheritance?

>He deprived men of their rightful inheritance when he desired their wealth, as rumors claim he did following the death of Lord Plumm upon his wedding day. (—Maester Yandel, TWOIAF: The Targaryen Kings: Aegon IV p95)

In that interpretation, the historian's words still technically allow that the man who Aegon wronged did receive an inheritance, but he received it wrongfully because he's a Targaryen and not a Plumm.

After you're finished rolling on the floor laughing, let's take a moment to appreciate the art of the lie.

I finally understand why the historian used the word "men" instead of "man." At the time the historian is writing this book, there have been five generations of Plumms since the time of Viserys Plumm's birth, and every Plumm man including and after Viserys can truthfully be called a "man who was deprived of his rightful inheritance," emphasis on rightful, because Viserys Plumm's father was not really Ossifer, and all of Viserys's descendants are therefore descendants of not-Ossifer, too.

The hilariously glaring omission? Neither Viserys Plumm nor any of his descenents would exist at all if Aegon hadn't fathered Viserys, because Ossifer Plumm died on his wedding night before he could do his duty in the marriage bed.

So Aegon the Unworthy is guilty as charged. Aegon caused rightful inheritances to be deprived from many Plumm men, none of whom would have ever been born to inherit anything if Aegon had not been so darn Unworthy. That rascal!

Honesty Tooled For Dishonesty

That was a good example of how these histories are laden with unreliable narrations. In this case, the unreliability is misrepresentation. The historian is using language in a sneaky way to tell a technically true statement that, upon closer inspection, is meaningfully false, and that does a lot of work to depict Aegon IV as a depraved monster.

As if to drive home the nail, the historian ends the story with a tactically placed reminder.

>and that the child she conceived that night was by her cousin Aegon—he who later became King Aegon the Unworthy.

'Yes, this man Aegon who I just mentioned is the same Aegon you've heard about, and who you'll probably recognize better as Aegon the (officially) Unworthy.' [Ominous screech]

Through this revelation we can begin to develop an understanding of what all did really happen in this situation, and what really was the true tone of these events and characters.

Inferring Cause From Effect

Why did Maester Yandel include the rumor at all? The effect of the rumor's inclusion was that it caused me to imagine that Aegon raped Elaena. In other words, it caused me to imagine Aegon being a villain. So a simple way to infer cause from effect is to invert the effect: Maybe Aegon was really the hero in the situation. And maybe the reason the historian needs to depict him as a villain is because Aegon's heroism is problematic for the royal narrative. Then I can start imagining how Aegon being the hero in the situation could be possible.

The effectiveness with which this piece of history hides the potential for Aegon to be the hero in the situation leads me to wonder if Aegon was really the hero in the situation. If nothing else, by having sex with Elaena on her wedding night and denying it, Aegon rescued the Plumm name from extinction. House Plumm is among the oldest Houses in Westeros, tracing their history all the way back to the Age of Heroes. It would be a shame for such an ancient House to fade away just because one generation had a stroke of bad luck.

In addition to being ancient, House Plumm is also rich. Remember, Elaena's history describes Ossifer Plumm as being wealthy.

>Her first marriage was in 176 AC, to the wealthy but aged Ossifer Plumm, who is said to have died while consummating the marriage.

Come to think of it, the accusation against Aegon mentioned wealth, too.

>He deprived men of their rightful inheritance when he desired their wealth, as rumors claim he did following the death of Lord Plumm upon his wedding day. (—Maester Yandel, TWOIAF: The Targaryen Kings: Aegon IV p95)

A desire for wealth was supposedly Aegon's motivation for depriving men of their rightful inheritance. But since Viserys Plumm did inherit House Plumm, then the wealth of House Plumm didn't go to Aegon, it went to Viserys Plumm. I mean, if Aegon is not really the person who ended up with House Plumm's wealth, that should cause us to doubt whether Aegon really had his sights set on House Plumm's wealth at all, shouldn't it?

I call this kind of analysis Follow The Money. It can be a good way to discover and correctly assign motivations in situations that involve money. The way I do it is I ignore everything I'm told about what peoples' motivations are, then I look at whose control the money is moving out of and into, and then I infer peoples' motivations based on who gained and who lost money.

Before Ossifer Plumm died on his wedding night, House Plumm's gold was in the control of Ossifer Plumm. Then Ossifer Plumm died on his wedding night, and at the same time Viserys Plumm was conceived (by Aegon). Nine to ten months later, Viserys Plumm was born. But a baby can't be the lord of a House in any way but name. He'll have to wait until he's grown before he can be the acting lord.

So, who really controls House Plumm and its gold for the fourteen to seventeen years between Viserys Plumm's conception and Viserys Plumm's ascension to acting lord?

His mother, Elaena Targaryen.

The effectiveness with which this piece of history hides the potential for Elaena to be the villain in the situation leads me to wonder if Elaena was really the villain in the situation. I mean, since the person who really ended up with House Plumm's wealth is Elaena, then maybe wealth was her motivation from the very beginning, rather than Aegon's. Marrying someone for their wealth does not seem like an especially villainous thing to do, but it seems cold and calculating. But maybe that's just because I'm not a Westerosi person.

If nothing else, this answers a question that I only now just realized I would have asked from the beginning if the situation were introduced to me differently. Why did the twenty-six year old Elaena Targaryen marry the "aged" and apparently frail of health Ossifer Plumm? To get the Plumm fortune.

Rhyme As Witness

But even that is the wrong question. Because you see, in context of Westerosi norms, Elaena's marriage to Ossifer does not demand as much explanation as does Ossifer's marriage to Elaena. Being the lord of a rich and ancient House with no heirs to speak of and few years left to live, Lord Ossifer Plumm was the juiciest plum in the seven kingdoms.

>"This old Plumm was a lord, though, must have been a famous fellow in his day, the talk of all the land. The thing was, begging your royal pardon, he had himself a cock six foot long.” (—Brown Ben Plumm, ASOS Daenerys V)

And not because of his giant cock. We'll arrive at that later.

This next mode of analysis I call Complete The Rhyme (taken from George R. R. Martin’s quote that History doesn’t always repeat but it does rhyme.). The way I do it is when I find a situation in the present day characters that mirrors (or rhymes with) the historical characters, or vice versa, I let knowns from one era fill in unknowns from the other era. In this case, Elaena Targaryen’s marriage to Ossifer Plumm rhymes with Lysa Arryn’s marriage to Jon Arryn. That is, young noble princess marries rich old lord who desperately needs an heir before he dies.

In Elaena's situation, we've arrived at a conflict of interpretation. Some readers will argue that Elaena was the bigger prize in the marriage, and other readers will argue that Ossifer was the bigger prize in the marriage. To fill in this unknown in the past, I can refer to Lysa's situation nearer to the present, and try to get a sense of the actual opinion of Westerosi people and nobles. Then I will have good grounding to suppose that the opinion in the past would have been the same as the opinion in the present.

>Catelyn rose, threw on a robe, and descended the steps to the darkened solar to stand over her father. A sense of helpless dread filled her. "Father," she said, "Father, I know what you did." She was no longer an innocent bride with a head full of dreams. She was a widow, a traitor, a grieving mother, and wise, wise in the ways of the world. "You made him take her," she whispered. "Lysa was the price Jon Arryn had to pay for the swords and spears of House Tully."

>

>Small wonder her sister's marriage had been so loveless. The Arryns were proud, and prickly of their honor. Lord Jon might wed Lysa to bind the Tullys to the cause of the rebellion, and in hopes of a son, but it would have been hard for him to love a woman who came to his bed soiled and unwilling. He would have been kind, no doubt; dutiful, yes; but Lysa needed warmth. (—Catelyn Stark, ASOS 2 Catelyn I)

As Catelyn's thoughts indicate, the general attitude of Westerosi nobles about Jon Arryn's marriage to Lysa Tully is that Jon Arryn is the bigger prize, with one reason being that Lysa's maidenhead is soiled. Westerosi people do not weigh passion as heavily nor wealth as lightly as we do in the real world where, under capitalism for instance, fortunes rarely last for hundreds of years, but are most often made and lost within the space of a few generations.

Not so unlike Elaena Targaryen, Jon Arryn, Lysa Arryn and Hoster Tully, Ossifer Plumm is not as concerned with love, compatibility or desire in the marriage as he is with the socio-political needs of his House. House Plumm desperately needs an heir, and fast, or else House Plumm will fall into disarray and ruin or disappear forever with the death of Ossifer Plumm. Every great House in the kingdom would know that, because lines of succession are integral to the political machinery of Westeros. And that's why Ossifer Plumm was "a famous fellow in his day, the talk of all the land." Elaena Targaryen would know about House Plumm's situation, too.

Additionally, just like Lysa's soiling made her a perfect candidate for marriage to an heirless old lord who can't afford the risk of marrying an infertile bride, so did Elaena's soiling.

>Elaena outlived her siblings and led a tumultuous life once freed from the Maidenvault. Following in Daena’s footsteps, she bore the bastard twins Jon and Jeyne Waters to Alyn Velaryon, Lord Oakenfist. She hoped to wed him, it is written, but a year after his disappearance at sea, she gave up hope and agreed to marry elsewhere.

So when Ossifer Plumm died on his wedding night before conceiving an heir, Elaena knew that without a Plumm heir to show for it she could assume no claim to House Plumm's wealth.

At the end of the Plumm puzzle, a whole different picture of the bedroom scene is beginning to take shape. It was not Aegon who seized upon the tragedy to slake his lusts upon Elaena, it was Elaena who urged Aegon to slake his lusts upon her, helping her to prevent her own tragedy of failing to secure House Plumm's wealth for herself.

I can almost write Elaena's lines in the bedroom scene myself.

The kings of old practiced the First Night, this is no different.

The Targaryens have wed brother to sister for hundreds of years.

No one will ever know.

We can save the old man's memory from humiliation.

Everywhere that Ossifer Plumm's name is mentioned in the main series, there can be found a Complete The Rhyme clue. Let's find Ossifer Plumm's name in a Cersei chapter in A Feast for Crows.

>To break her fast the queen sent to the kitchens for two boiled eggs, a loaf of bread, and a pot of honey. But when she cracked the first egg and found a bloody half-formed chick inside, her stomach roiled. “Take this away and bring me hot spiced wine,” she told Senelle. The chill in the air was settling in her bones, and she had a long nasty day ahead of her.

>

>Nor did Jaime help her mood when he turned up all in white and still unshaven, to tell her how he meant to keep her son from being poisoned. “I will have men in the kitchens watching as each dish is prepared,” he said. “Ser Addam’s gold cloaks will escort the servants as they bring the food to table, to make certain no tampering takes place along the way. Ser Boros will be tasting every course before Tommen puts a bite into his mouth. And if all that should fail, Maester Ballabar will be seated in the back of the hall, with purges and antidotes for twenty common poisons on his person. Tommen will be safe, I promise you.”

>

>“Safe.” The word tasted bitter on her tongue. Jaime did not understand. No one understood. Only Melara had been in the tent to hear the old hag’s croaking threats, and Melara was long dead. “Tyrion will not kill the same way twice. He is too cunning for that. He could be under the floor even now, listening to every word we say and making plans to open Tommen’s throat.”

>

>“Suppose he was,” said Jaime. “Whatever plans he makes, he will still be small and stunted. Tommen will be surrounded by the finest knights in Westeros. The Kingsguard will protect him.”

>

>Cersei glanced at where the sleeve of her brother’s white silk tunic had been pinned up over his stump. “I remember how well they guarded Joffrey, these splendid knights of yours. I want you to remain with Tommen all night, is that understood?”

>

>“I will have a guardsman outside his door.”

>

>She seized his arm. “Not a guardsman. You. And inside his bedchamber.”

>

>“In case Tyrion crawls out of the hearth? He won’t.”

>

>“So you say. Will you tell me that you found all the hidden tunnels in these walls?” They both knew better. “I will not have Tommen alone with Margaery, not for so much as half a heartbeat.”

>

>“They will not be alone. Her cousins will be with them.”

>

>“As will you. I command it, in the king’s name.” Cersei had not wanted Tommen and his wife to share a bed at all, but the Tyrells had insisted. “Husband and wife should sleep together,” the Queen of Thorns had said, “even if they do no more than sleep. His Grace’s bed is big enough for two, surely.” Lady Alerie had echoed her good-mother. “Let the children warm each other in the night. It will bring them closer. Margaery oft shares her blankets with her cousins. They sing and play games and whisper secrets to each other when the candles are snuffed out.”

>

>“How delightful,” Cersei had said. “Let them continue, by all means. In the Maidenvault.”

>

>“I am sure Her Grace knows best,” Lady Olenna had said to Lady Alerie. “She is the boy’s own mother, after all, of that we are all sure. And surely we can agree about the wedding night? A man should not sleep apart from his wife on the night of their wedding. It is ill luck for their marriage if they do.”

>

>Someday I will teach you the meaning of “ill luck,” the queen had vowed. “Margaery may share Tommen’s bedchamber for that one night,” she had been forced to say. “No longer.”

>

>“Your Grace is so gracious,” the Queen of Thorns had replied, and everyone had exchanged smiles.

>

>Cersei’s fingers were digging into Jaime’s arm hard enough to leave bruises. “I need eyes inside that room,” she said.

>

>“To see what?” he said. “There can be no danger of a consummation. Tommen is much too young.”

>

>“And Ossifer Plumm was much too dead, but that did not stop him fathering a child, did it?”

>

>Her brother looked lost. “Who was Ossifer Plumm? Was he Lord Philip’s father, or … who?”

>

>He is near as ignorant as Robert. All his wits were in his sword hand. “Forget Plumm, just remember what I told you. Swear to me that you will stay by Tommen’s side until the sun comes up.” (AFFC 12 Cersei III)

In this passage, Cersei references Ossifer Plumm as an example from history of a dynasty being hereditarily usurped, because any pregnancy conceived on the bride during or near her wedding night will be assumed the child of the husband. The baby will go on carrying the dynasty name without a drop of the blood in his veins.

Jaime doesn't know this bit of history, so he doesn't understand the reference. He guesses that Ossifer was the father of Lord Philip Plumm, who is the current Lord of House Plumm at the time of Jaime and Cersei's conversation. Jaime's guess shows me that the history-ness of the reference is definitely the reason Jaime doesn't know it. He was more interested in swordfighting than history.

As if to settle the debate about whose idea it was — between Aegon IV and Elaena Targaryen — to pass off Aegon's baby as Ossifer's baby, A Song of Ice and Fire chooses a side by showing me that the same idea occurred first to our present day woman, and not at all to our present day man.

By traveling from one era to the other along the dimension of gender, this instance of Complete The Rhyme points to the differences between men and women as somehow containing the explanation for why such an idea occurs to Elaena and Cersei before Aegon and Jaime. The idea for pregnancy sneakiness would reasonably occur sooner to a person who is capable of pregnancy than to a person who is not.

History Written With The Sword

Let's take another moment to appreciate the art of the lie. In order to completely reverse the hero and villain roles of this part of history, the historian had to do little more than lift the villain's motivation from off the villain and place it onto the hero. "He deprived men of their rightful inheritance when he desired their wealth, (...)"

When a House goes extinct, all of its land, wealth, property and titles are returned to the king. The king can then do with them as he likes. Far from a desire for House Plumm's wealth, by making a baby with Elaena, Aegon prevented himself from receiving House Plumm's wealth and enabled Elaena to receive it instead.

Aegon knew that because he was king at the time and that he would likely remain king for many years to come, House Plumm's extinction would remain a secret, allowing its name to live on. Few are the people who would dare to publicly accuse the *king* of lying about such a thing. Far from abusing his kingly power to gratify himself free from criticism, Aegon managed to put his kingly freedom from criticism to work toward a selfless and sentimental result.

With the historian's reconfiguration, the memory of Elaena enjoys an undeserved boon, and the memory of Aegon suffers an undeserved curse. Why? Because history is written by the victors, and the victor of history was Daeron II Targaryen.

After Aegon's death, Elaena became Daeron's highly capable master of coin during his reign as king.

>Her second marriage was at the behest of Aegon the Unworthy’s successor, King Daeron the Good. Daeron wed her to his master of coin, and this union led to four more children … and to Elaena becoming known to be the true master of coin, for her husband was said to be a good and noble lord but one without a great facility for numbers. She swiftly grew influential, and was trusted by King Daeron in all things as she labored on his behalf and on that of the realm. (—Maester Yandel, TWOIAF: The Targaryen Kings: Baelor I p92)

Calculating, indeed. How did Elaena get so much practice with numbers, anyway?

The quality of a king's court reflects the quality of the king, and since Elaena was a key member of King Daeron's trusted court, her villainy was an annoyance to historians. So whenever Daeron and his descendants conscripted a history book, the historian found better use of Elaena by hiding her unflattering motivations and deeds and instead allowing suggestion to grant her the role of victim. Therein lies much of the historian's reason for including Mushroom's version of the story.

If Mushroom's version had been left out, the passage would not have conjured in my mind that awful bedroom scene of Aegon the Unworthy's unworthiness. As references to Ossifer Plumm in the main series indicate, it's an open secret that Aegon IV rather than Ossifer Plumm fathered Viserys Plumm. The "cock" in Brown Ben Plumm's "he had a cock six foot long" quote is, of course, referring to the "length" (height) of King Aegon IV, implying that Aegon rather than Ossifer impregnated Elaena, and with double entendre where "cock" also works as an insult to Aegon.

Indeed, it would seem that evoking the image of Aegon forcing or insisting himself upon Elaena in the in-story reader's mind was the historians' only reason for including Mushroom's version at all. It's the specifically sexual and self-gratifying kind of villainy that history has branded Aegon with to great effect in the public consciousness. Thus concludes our game of Scenes That Must Have Happened. In light of everything we've learned, the scene that the histories evoke through suggestion does not make sense with the facts.

At the same time, we should be careful not to underestimate the historians. Like Maester Yandel, a person generally doesn't come to write history without having in his heart a genuine love and commitment to true knowledge. While it's true that, in the context of the "Unworthy" theme of Aegon the Unworthy, the inclusion of Mushroom's version of this piece of history will predictably cause an in-story reader to imagine the bedroom rape scene, it's also true that without the inclusion of Mushroom's version, it would not have been possible for we sleuthing readers or maesters to have researched and reasoned our way to the true history. The "rumor" that Viserys Plumm was really sired by Aegon rather than Ossifer is what enabled us to discover everything else. Without it, there wouldn't have been two competing accounts, and we would have gone on believing the official one that Viserys was sired by Ossifer. So it's conceivable that Maester Yandel was counting on smart readers to be unsatisfied with the uncertainty and to dig out the true version.

A Memory Accursed

On the topic of public consciousness, let's look at another Complete The Rhyme from the present day characters.

>Viserion spread his pale white wings and flapped lazily at his head. One of the wings buffeted the sellsword in his face. The white dragon landed awkwardly with one foot on the man’s head and one on his shoulder, shrieked, and flew off again. “He likes you, Ben,” said Dany.

>

>“And well he might.” Brown Ben laughed. “I have me a drop of the dragon blood myself, you know.”

>

>“You?” Dany was startled. Plumm was a creature of the free companies, an amiable mongrel. He had a broad brown face with a broken nose and a head of nappy grey hair, and his Dothraki mother had bequeathed him large, dark, almond-shaped eyes. He claimed to be part Braavosi, part Summer Islander, part Ibbenese, part Qohorik, part Dothraki, part Dornish, and part Westerosi, but this was the first she had heard of Targaryen blood. She gave him a searching look and said, “How could that be?”

>

>“Well,” said Brown Ben, “there was some old Plumm in the Sunset Kingdoms who wed a dragon princess. My grandmama told me the tale. He lived in King Aegon’s day.”

>

>“Which King Aegon?” Dany asked. “Five Aegons have ruled in Westeros.” Her brother’s son would have been the sixth, but the Usurper’s men had dashed his head against a wall.

>

>“Five, were there? Well, that’s a confusion. I could not give you a number, my queen. This old Plumm was a lord, though, must have been a famous fellow in his day, the talk of all the land. The thing was, begging your royal pardon, he had himself a cock six foot long.”

>

>The three bells in Dany’s braid tinkled when she laughed. “You mean inches, I think.”

>

>“Feet,” Brown Ben said firmly. “If it was inches, who’d want to talk about it, now? Your Grace.”

>

>Dany giggled like a little girl. “Did your grandmother claim she’d actually seen this prodigy?”

>

>“That the old crone never did. She was half-Ibbenese and half-Qohorik, never been to Westeros, my grandfather must have told her. Some Dothraki killed him before I was born.”

>

>“And where did your grandfather’s knowledge come from?”

>

>“One of them tales told at the teat, I’d guess.” Brown Ben shrugged. “That’s all I know about Aegon the Unnumbered or old Lord Plumm’s mighty manhood, I fear. I best see to my Sons.”

>

>“Go do that,” Dany told him. (ASOS Daenerys V)

In this passage, Daenerys's dragons show a liking for Brown Ben Plumm, suggesting that Mushroom's version of the Ossifer Plumm story is true, and contradicting the recurring insistences from Maester Yandel and other historians that Mushroom's versions of history are probably wrong.

Brown Ben Plumm claims to have a little bit of Targaryen in his heritage, referring to the same rumor we heard from Mushroom and Cersei that King Aegon IV the Unworthy was the biological father of Viserys Plumm.

Dany can see that Brown Ben has none of the traditional Targaryen features — not the silver hair, purple eyes, or pale skin. But since dragons are magical sorts of animals and animals have ways of sensing things that humans can't sense, I'm left with the impression that the behavior of the dragons is a more reliable test than Brown Ben's appearance.

I can be sure that the "old Plumm who lived in the Sunset kingdoms," "wed a dragon princess" and "lived in Aegon's day" is Ossifer Plumm, because Ossifer Plumm is the only Plumm who matches all of those descriptions.

Brown Ben credits his "drop of Targaryen blood" to a Targaryen princess, who I know was Elaena Targaryen. Both the official and rumor versions of history agree that Viserys Plumm's mother was Elaena Targaryen. But Brown Ben is more right than he knows, because Viserys Plumm's father was a Targaryen, too, none other than the king Aegon. Comically, Brown Ben takes his grandmama's story too literally, not understanding that Ossifer Plumm's "cock six foot long" is referring to Aegon the man rather than to Ossifer's literal endowment.

In the Ossifer Plumm situation from history, there is some disagreement in the interpretation. Some readers will say that the history is not really lying that a deprivation occurred, because Aegon did in fact deprive Plumm men of their rightful ineritances, meaning their inheritances being rightful, and that those Plumm men would prefer it if they were real Plumms so that they don't have to live a lie. And some readers will say that the Plumms would feel bad about being a descendent of such an Unworthy king, saying that House Plumm lost more than it gained when it was hereditarily usurped by House Targaryen.

As if to settle those disagreements, A Song of Ice and Fire chooses a side by showing me in this passage that the Plumm family themselves preserved the knowledge of Aegon's contribution to the Plumm line in a funny and memorable story, passing it down through the Plumm generations to arrive to us and Daenerys in the present day.

As wealthy as House Plumm may be, House Targaryen is wealthier and more powerful. And as desirable a position as Lord of House Plumm may be, it struggles to compare to the positions that are possible as a Targaryen descendent of a king— Heir Apparent, Crown Prince, King. For the noble Houses of Westeros, royalty is the last and most elusive rung to climb on the socio-economic ladder. Once your family gets into the Targaryen club, it's a permanent member. The more your family gets into the Targaryen family, the more chances your family has of being the lucky spot on the Targaryen lineage tree where the royal succession lands.

This passage further demonstrates that maester historians rely upon the "Aegon the Unworthy" narrative to do most of the work of misleading the in-story audience from the truth. Likewise, George R. R. Martin relies upon it to do most of the work of misleading us from the truth. Had I done a better job of leaving my real world attitudes at the door and adopting in-story attitudes, I would have noticed sooner that, far from deprivation of their rightful inheritance, it's better to be a real Targaryen Prince disguised as a real Plumm than to be simply a real Plumm. As simply a real Plumm you get House Plumm, but as a real Targaryen Prince disguised as a real Plumm you get all the same things as a real Plumm plus the chance of winning the Kinghood by the ever-unfolding lottery of unpredictable events. In this way, the Aegon the Unworthy narrative is symbolic of our tendency to slide into our real world attitudes, inappropriately abandoning the in-story attitudes in which the attraction of moving one's family into the line of royal succession far outweighs the repulsion of being associated with a king who has a bad reputation.

With the purple fruits of our labor in hand, let's carry all that we've learned about the Plumm situation in this chapter on to the next chapter, where we'll dive into another sentence from that original paragraph in The World of Ice and Fire.

Next: Chapter 4 - Butterwell and Eggs

applesanddragons

#asoiaf#asongoficeandfire#a song of ice and fire#applesanddragons#aegon the unworthy#aegon iv targaryen#the world of ice and fire#elaena targaryen#ossifer plumm#agameofthrones#aclashofkings#astormofswords#adancewithdragons#georgerrmartin#literaryanalysis

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forest Love and Forest Lass - Chapter 3 - The Knight of the Laughing Tree, A Rose in a Wasteland

Meera Reed's telling of the Tourney at Harrenhal is a chunk of text that makes up the bulk of the chapter Bran II, filling out no less than six pages in my paperback copy of A Storm of Swords (p279 if you want to reread it or follow along).

For readers who have visited the Knight of the Laughing Tree mystery many times, we often feel as though we've said everything there is to say. Without a doubt, in the dozens of Knight of the Laughing Tree discussions I've read over the years, a small handful of details such as the "booming voice" and ones pertaining to jousting ability received the greatest share of attention. We have a tendency to rapidly hone-in on the parts of the mystery that are debated the most hotly, perhaps sensing that, in some way or another, those debates are the point.

u/AlanCrowkiller

2 points 2014

You don't have to like it but you're going to have to suck it up and accept it that Martin is fine with his world being a place where a fourteen year old girl can joust with grown men. [1]

Since attention and time are limited, it's a smart way to approach the mystery. As a consequence, however, there may be much to learn by tilting at parts that receive less attention and approaching the Tourney at Harrenhal in different ways or with different questions.

This time, let's approach Meera's story as a story, and do our best to forget about the real identities of the characters. For example, we won't think of the crannogman as Howland Reed, we'll just think of him as the crannogman. The wolf maid won't be Lyanna, she'll be the wolf maid, no less and no more. We'll leave behind everything we know about their real identities, and instead use only the information that Meera's story provides. I'll call this way of interpreting the story 'story-mode' interpretation.

What is the story about? The story is about a heroic knight. Three squires beat up the crannogman, and then he was rescued by the she-wolf. That night, the crannogman left the quiet wolf's tent to say a prayer beside the lake. The next day, the mystery knight appeared in the jousting tournament and defeated all three of the offending squires' knights, to the cheering of the crowd, winning ownership of their horses and armor. When the knights came to the mystery knight to ransom (buy back) their horses and armor, the mystery knight said:

"(...) ‘Teach your squires honor, that shall be ransom enough.’ Once the defeated knights chastised their squires sharply, their horses and armor were returned. And so the little crannogman’s prayer was answered … by the green men, or the old gods, or the children of the forest, who can say?” (—Meera Reed, ASOS Bran II)

As of A Dance with Dragons, this act of heroism is the clearest and cleanest instance of heroism in the entire series of A Song of Ice and Fire. In a story where no character's hands ever stay perfectly clean, the Knight of the Laughing Tree stands out like a rose in a frozen wasteland. He or she is the one character that potentially belies A Song of Ice and Fire's apparent thousands-page-long proposition that maybe genuine heroes only exist in naive fictional stories. It's no wonder, then, why readers are ravenous to know the knight's true identity, and why we're eager to propose our most beloved characters as the knight.

But if we ever do learn the mystery knight's true identity, and if it's a character we already know, we would then be able to know his other deeds in life, too. Without a doubt, his hands would have some dirt on them like everyone else's do, because nobody can be perfect. So it's possible and perhaps likely that the Knight of the Laughing Tree's heroism is merely a consequence of information about him being so limited, it being confined to this one event. In that way, the story would demonstrate that genuine heroes really do only exist in fictional stories, and that the only way to convince us otherwise was to keep us naive about his other deeds.

As a result, the thematic stakes of the Knight of the Laughing Tree's identity could not be higher. 'Who was A Song of Ice and Fire's only true hero? And was he really a hero? And was he really a he?'

So what is it, exactly, that makes the Knight of the Laughing Tree seem so heroic? It's selflessness. At every crossroad he encounters, he chooses the most selfless path.

He could have ignored the needs of the crannogman, the prayer, or whatever it was that compelled him to defeat the three knights. Doing nothing would have been easier than doing all that.

He could have kept the horses and armor for himself, having already achieved a symbolic justice for the crannogman by defeating the offending squires' knights.

He could have given the horses and armors to the crannogman, transferring wealth from the offending party to the offended party and thereby punishing the knights for neglecting to teach their squires honor and simultaneously compensating the crannogman for the damage he suffered to his body and pride.

I can even see how the Knight of the Laughing Tree rescued the crannogman from the crannogman himself. The crannogman wanted revenge against the squires, but he didn't know how to joust in order to get it by jousting. There's no telling which ugly alternative he might have resorted to if the Knight of the Laughing Tree had not been there to alleviate the injustice of the situation.

The Knight of the Laughing Tree could have revealed his own identity after winning the jousts. Doing so would have pleased the lustful audience and transferred the love and renown that was earned for his fake identity to his real identity.

As it happens, when I look at all of the mystery knights that have been mentioned in A Song of Ice and Fire (as of A Dance with Dragons) the Knight of the Laughing Tree is the only one whose identity remains unknown.

The Knight of Tears was Aemon Targaryen

The mystery knight at Blackhaven was Barristan Selmy

The mystery knight at King's Landing was Barristan Selmy

The mystery knight at Storm's End was Simon Toyne

Blackshield was the Bastard of Uplands

The Gallows Knight was Ser Duncan the Tall

John the Fiddler was Daemon II Blackfyre

The Serpent in Scarlet was Jonquil Darke

The Silver Fool was Baelon Targaryen

The Knight of the Laughing Tree was ...

Even among heroes, the Knight of the Laughing Tree's selflessness stands out from all the rest.

If the hero was apparently not interested in wealth, revenge or renown, the question remains: Just what the bloody hell was motivating the Knight of the Laughing Tree?

Justice is a good answer. He achieved symbolic justice for the crannogman and literal justice for the squires, who will benefit long-term from learning honor and having their knights reminded of their duties to them. But that does not seem like a description of the Knight of Laughing Tree's heroism that goes far enough, because the benefits to the squires will extend to their own squires in the future, and theirs after them.

Undoubtedly, much of the reason that the three knights have neglected to teach their squires enough honor so as to prevent them from beating up someone for being different can be traced back to the time when the knights were squires themselves. Their own knights must have done a poor job of teaching them honor, too, or else they wouldn't have become negligent knights, or wouldn't have been knighted at all. After all, only a knight can make another knight.

"Any knight can make a knight, and every man you see before you has felt a sword upon his shoulder." (—Beric Dondarrion to Sandor Clegane, ASOS Arya VI)

It required a knight to make a knight, and if something should go awry tonight, dawn might find him dead or in a dungeon. (—Thoughts of Barristan, ADWD The Kingbreaker)

Similarly, if the Knight of the Laughing Tree had given the winnings to the crannogman rather than leveraging the winnings to compel the knights to teach their squires honor, there can be small doubt that the squires, if knighted, would have grown up to become negligent knights themselves, who would go on to produce worse squires who become even worse knights. These recognitions portray an institution of knighthood and a Westerosi tradition that are in a state of decline.

The Knight of the Laughing Tree was able to look beyond the bruised body and pride of the crannogman, the wrongdoings of the squires and the shortcomings of the knights, and see how each of those problems reaches back into history and forward into the future so as to partly implicate and exonerate every individual person and grouping of people involved. Indeed, these are problems that have mostly built up slowly over generations, one ordinary and understandable shortcoming at a time. Who can honestly say that he has never been guilty of neglecting his duties, of laziness, complacency, forgetfulness or of going too easy on the young people who depend upon him to enforce firm enough boundaries? Scarcer, still, is a person who is unable to see the seeds of his own shortcomings in the imperfections and unheroism of the people he once depended upon.

Having accounted for the sympathetic viewpoints of everyone involved in the past, present, and future, the Knight of the Laughing Tree was now able to see that there are no mustache-twirling villains in the situation, there are only ordinary people with ordinary flaws. With a mission to correct for this long history of ordinary flaws, he took the burden upon himself to rearrange costs and incentives in such a way as to motivate the three knights to do their duty to their squires, their society and ultimately their Westerosi tradition of knighthood. And he did it at risk to himself, by using his own body, skills, courage, and the imperfect institutions and traditions at hand.

Yet still... yet still... that does not seem like a description of the Knight of the Laughing Tree's heroism that goes far enough.

What does the mystery knight represent with his identity unknown, compared to with his identity exposed? With his identity unknown, the mystery knight is just a knight — a symbol of knighthood itself. If I don't know who he is, then I don't know what's wrong with him. More than that, I can never find out what's wrong with him. I will never know how he might be failing to live up to the knightly ideal as much as I am or more.

Isn't that the first thing everybody tries to do after we're caught falling short of our ideals? Especially when we're caught publicly? Instead of taking stock of myself, I tend instead to attack the ideal.

So a predictable reaction that the negligent knights and their squires might have after being publicly defeated and criticized is to find things that are wrong with the mystery knight. It's a way to alleviate themselves of the unpleasant conscientious responsibility to admit to themselves that they're not truly striving to be as good as they know they can be.

“I’ve never lain with any woman but Cersei. In my own way, I have been truer than your Ned ever was. Poor old dead Ned. So who has shit for honor now, I ask you? What was the name of that bastard he fathered?”

Catelyn took a step backward. “Brienne.”

“No, that wasn’t it.” Jaime Lannister upended the flagon. A trickle ran down onto his face, bright as blood. “Snow, that was the one. Such a white name . . . like the pretty cloaks they give us in the Kingsguard when we swear our pretty oaths.” (—Catelyn and Jaime, ACOK Catelyn VII)

In the dungeons of Riverrun, Jaime seized upon his knowledge of a dishonorable moment in Ned's past to attack the ideal of honor itself, as though Ned's dishonor somehow excuse's Jaime's dishonor, or as though to suggest that honor is a mostly unworthy thing to strive for at all. Even the ambiguity between those two suggestions expedites the same purpose by hiding the rationale in the fog. This sort of thing happens in the minds of POV characters all throughout A Song of Ice and Fire, and it shows me much of what it means for a human heart to be in conflict with itself.

With the mystery knight's identity forever concealed, knowledge of his imperfections and past mistakes is forever unavailable to the three knights and their squires. Being deprived of information that they might likely use in their defeated state to assault the ideal that the mystery knight represents in their own consciences, the negligent knights and dishonorable squires cannot psychologically escape judgement from their own ideal, and are forced to admit to themselves that they were wrong, lest they be haunted by their consciences ever after.

The Knight of the Laughing Tree knew that revealing his identity would risk sabotaging their chances of development. He was protecting the knights and squires from themselves even as he was reprimanding them. And therein lies the proof of his motivation and heroism. The Knight of the Laughing Tree story is not about a knight merely avenging a crannogman, rescuing a crannogman's pride, or even righting wrongs between contemporary people. With the heroism rooted in the knight's motivation and with his motivation proven by his anonymity, it is a story about a knight rescuing the institution of knighthood.

I think that's why the Knight of the Laughing Tree is the fullest and truest hero in A Song of Ice and Fire to date. If there be one righteous knight in Westeros, peradventure mankind and existence are still worth loving.

To unmask the Knight of the Laughing Tree is to destroy his anonymity. To destroy the Knight of the Laughing Tree's anonymity is to destroy the proof of his heroism. To say "the only way to convince me that genuine heroes really exist is to keep me naive about his other deeds" is to set a standard of proof of heroism that requires the destruction of the proof of the Knight of the Laughing Tree's heroism. In this way, the true motivations behind such an attitude are exposed. For the parts of myself that agree with it, the destruction of heroism is the point. I am already engaged in an assault against my own ideal.

After Bran hears the story, he offers critiques and suggests changes that he thinks would be improvements to the story.

“That was a good story. But it should have been the three bad knights who hurt him, not their squires. Then the little crannogman could have killed them all. The part about the ransoms was stupid. And the mystery knight should win the tourney, defeating every challenger, and name the wolf maid the queen of love and beauty.” (—Bran, ASOS Bran II)

These lines from Bran show me that Bran is missing the deeper meanings of the story just like I was for so long. He thinks the story would be better if the squires were removed entirely, making the knights more villainous and more straightforwardly villains. Then, once the knights are made into one-dimensional villains, Bran thinks the knights should all be killed by the hero. Not merely defeated in the tournament, but killed! Then as reward, he wants the hero to win everything at the end, both the tourney and the girl, too.

Bran doesn't seem to notice how these changes would destroy the story's deeper meanings. He doesn't notice that the Knight of the Laughing Tree is trying to fix society rather than simply avenging a crannogman and sticking it to the bad guys.

So the theme of Bran's comments is that 'Bran is missing the deeper meanings of the story.'

"And the mystery knight should win the tourney, defeating every challenger, and name the wolf maid the queen of love and beauty.”

“She was,” said Meera, “but that’s a sadder story.” (ASOS Bran II)

Meera doesn't bother to tell Bran that he's missing the deeper meanings of the story. As the storyteller, Meera represents George R. R. Martin. As Meera's audience, Bran represents the reader.

With Meera's final comment, the mystery of The Relationship Between The Two Mysteries stirs beneath A Song of Ice and Fire's surface. In relationship to the theme of Bran's comments, Meera's line is the quietest whisper of suggestion that A Song of Ice and Fire is hiding an association between 'missing the deeper meanings of the story' and 'the dragon prince naming the wolf maid the queen of love and beauty.'

Me: https://applesanddragons.home.blog/2022/04/03/forest-love-and-forest-lass/

#asoiaf#asongoficeandfire#literature#literaryanalysis#theknightofthelaughingtree#howlandreed#lyannastark#nedstark#meerareed#jojen reed#agameofthrones#georgerrmartin#thetourneyatharrenhal#rhaegartargaryen#R+L=J#jonsnow

0 notes

Text

Forest Love and Forest Lass - Chapter 2 - The Tourney at Harrenhal

To recount every joust and jape is far outside our purpose here. That task we gladly leave to the singers. Two incidents must not be passed over, however, for they would prove to have grave consequences. (—Maester Yandel, TWOIAF)

Who was the Knight of the Laughing Tree? And why did Rhaegar crown Lyanna the queen of love and beauty?

The Tourney at Harrenhal is one event that contains two mysteries. These two mysteries are inescapably entangled throughout the story. It seems that the nearer a topic is to one or both of these questions, the more it is characterized by missing information. Cryptic memories like "Promise me, Ned" and Ned's dream about the Tower of Joy are two such topics.

This fog surrounding the two mysteries is a pattern that alludes to the existence of some unknown connection between the two mysteries that, when it becomes known, should illuminate the full truth of them both. To many readers, this connection and the story's subtle but persistent suggestion of its existence has long seemed to be the real mystery at hand.

u/Jaomi

2 points 2018

What happened between those two is the single most critical piece of backstory, because without it, none of the rest of the tale happens. The Targs don't go into exile and Dany doesn't hatch the dragons. Cat marries Brandon, so the Stark kids as we know them never exist. Jon is never born. So much of the plot hinges on their relationship, that one has to believe GRRM had a fair idea of how it happened before he wrote it all out for us to read. [1]

Whatever the answer or answers to the two Tourney at Harrenhal questions, the in-story reminders of their cohabitation within the same event (such as the opening quote from Maester Yandel) suggest that there's a relationship between them, and that the nature of the relationship is the cream of both mysteries. I call this relationship 'The Relationship Between The Two Mysteries.' That is the topic of Forest Love and Forest Lass moreso than either one of the two mysteries.

Identifying that there is a mystery regarding the relationship between the two mysteries is no species of master key to unlocking ASOIAF's secrets, nor is it a license to circumvent the original two mysteries. I knew that if I wanted to have any chance of gleaning The Relationship Between The Two Mysteries, I needed to develop an intimate understanding of the two mysteries themselves as separate things. So I began where they happened, at the Tourney at Harrenhal.

The events of the Tourney at Harrenhal are provided by three different sources. Foremost of those sources is Meera Reed in the chapter ASOS Bran II. Her account is the longest and most detailed account of them all, however much the truth of the events and people that interest us might be obscured by their translation to mythology and symbols, such as "lake" for God's Eye and "wolf pup" for Benjen.

“There was one knight,” said Meera, “in the year of the false spring. The Knight of the Laughing Tree, they called him. He might have been a crannogman, that one.” (—Meera Reed, ASOS Bran II)

Next is Maester Yandel in The World of Ice and Fire. Yandel's account is the second longest account, however unreliable of a narrator he may or may not be.

As warm winds blew from the south, lords and knights from throughout the Seven Kingdoms made their way toward Harrenhal to compete in Lord Whent’s great tournament on the shore of the Gods Eye, which promised to be the largest and most magnificent competition since the time of Aegon the Unlikely. (—Maester Yandel, TWOIAF: The Year of the False Spring)

Next is everybody else. This is a category of sources rather than a source in and of itself, but it's a useful category for my purpose of explaining things. Every off-handed mention, reference or allusion throughout ASOIAF of the events of, surrounding or related to the Tourney at Harrenhal by characters such as Ned, Barristan, Daenerys and Robert falls into this third category.

"And Rhaegar . . . how many times do you think he raped your sister? How many hundreds of times?” (—Robert Baratheon to Ned, AGOT Eddard II)

Meera Reed's account sings with such thematic resonance, narrative wonder and A Song of Ice and Fire style that I have returned to pore over it more than any other text in the series. All of the characters in it are represented in symbolic terms like their House sigils, heritages, affiliations and nicknames — stylistic patterns so pervasive throughout the series that translations like "dragon" to "Targaryen" and "wolf" to "Stark" have become second-nature to the readers.

The crannogman = Howland Reed

The lake = God's Eye

The castle = Harrenhal

The host = Walter Whent

The King = Aerys Targaryen

The dragon prince = Rhaegar Targaryen

The white swords = Aerys's Kingsguard

The storm lord = Robert Baratheon

The rose lord = Mace Tyrell

The great lion of the rock = Tywin Lannister

The daughter of the castle / fair maid = Walter Whent's daughter

Her four brothers = Walter Whent's sons

Her uncle a white knight of the Kingsguard = Oswell Whent

Wife of the dragon prince = Elia Martell

A dozen of her lady companions = Including Ashara

The porcupine knight = A knight of House Blount

The pitchfork knight = A knight of House Haigh

The knight of the two/twin towers = A knight of House Frey

The she-wolf / wolf maid = Lyanna Stark

The wild wolf = Brandon Stark

The quiet wolf = Eddard Stark

The wolf pup = Benjen Stark

The knight of skulls and kisses = Richard Lonmouth

A maid with laughing purple eyes = Ashara Dayne

A white sword = Barristan Selmy

A red snake = Oberyn Martell

The lord of griffins = Jon Connington

With dozens of characters populating Meera's story this way, and combined with the series' baked-in emphasis that perspective is everything, A Song of Ice and Fire sounds its warcry loud and clear:

'The Tourney At Harrenhal Is My Ultimate Challenge. Test Your Knowledge Of Me Here, If You Dare!'

The Tourney at Harrenhal has always seemed to me to be the soulful centerpiece of A Song of Ice and Fire's deepest secrets, and it's where I begin our dig into the fine (and familiar) details of the story. As it happens, the translation of events to mythology both obscures and reveals the truth of them.

Me: https://applesanddragons.home.blog/2022/04/03/forest-love-and-forest-lass/

#forestloveandforestlass#asongoficeandfire#asoiaf#literature#literaryanalysis#knightofthelaughingtree#kotlt#lyannastark#nedstark#R+L=J#harrenhal#rhaegartargaryen#jonsnow#thetourneyatharrenhal

0 notes

Text

Forest Love and Forest Lass - Chapter 1 - The Maiden of the Tree

At a small castle in the Riverlands called Acorn Hall, Arya Stark and Gendry have just returned to the main hall after a bit of playful rough-housing in the smithy. As they enter the hall together looking disheveled, a man named Tom of Sevenstreams sings this song.

My featherbed is deep and soft,

and there I'll lay you down,

I'll dress you all in yellow silk,

and on your head a crown.

For you shall be my lady love,

and I shall be your lord.

I'll always keep you warm and safe,

and guard you with my sword.

And how she smiled and how she laughed,

the maiden of the tree.

She spun away and said to him,

no featherbed for me.

I'll wear a gown of golden leaves,

and bind my hair with grass,

But you can be my forest love,

and me your forest lass. (ASOS Arya IV)

Tom of Sevenstreams no doubt can see as clearly as the readers can that the narrative seeds of a young-love romance between Arya and Gendry are planted in these scenes. In the context of Arya and Gendry reappearing together, the song is meant to relate to them — certainly through the eyes of Tom, but perhaps also through the thematic lens of the story itself. It is this lens that I focus my attention upon.

First I asked myself, what is the song itself about? What does it seem to mean when I remove the context of Arya, Gendry and Tom, and view it in isolation, as a work of art that has its own inherent characteristics and internal logic separate from these specific people, this specific place and time?

The song begins with the voice of a man. The man is offering a woman some things such as a featherbed, a crown, a romance and safety. All of these things together constitute a marriage, and so the offers constitute a marriage proposal. And I think he's trying to be persuasive about it.

The second half of the song is the woman responding to the man. She's being lighthearted about his offerings, but ultimately she's rejecting them. She proposes all of the same sort of things in response, except in the more casual, affordable and temporary forms of forest debris. The woman's suggestions contrast the man's suggestions in a way that suggests that she does want the romance he offers, and perhaps sex, too, but she wants them informally and outside of the cultural norms of society.

A possible implication in the song is that the man believes his offerings somehow entitle him to the woman's affection, as if material things, status and protection are what the woman necessarily needs or wants in a romance, and as if her personal preferences do not weigh or weigh much in the matter. But maybe the man didn't mean it that way.

The man offers the titles "lady love" and "lord." The woman changes them to "forest love" and "forest lass." Notice that now the man is the "love" rather than the woman.

The word "love" can mean affection, or it can mean sex, as in "lover" and "lovemaking." So by moving the "love" title to the man, another possible implication in the song is that the woman received "lady love" to mean something offensive to her, perhaps approximating "lady for sex" or "sexual plaything." In her new framing, she may be casting the man as her sexual plaything instead. Turning the tables, so to speak. But maybe the woman was not offended and is not returning insult in this way.

The titles of "lord" and "lady" are part of Westerosi culture, so they represent Westerosi culture. The title of "forest" depicts a physical change of venue from civilization to the wilderness. In this song, the forest and forestry are symbolic of a rejection of and removal from civilization, tradition and culture, as well as an embracement of nature — both the nature of the earth and the nature within themselves that compels them to have sex regardless of the cultural norms and expectations that might prevent them from doing it.

So I think all of that is what the song itself is about. Simply put, a man offers a woman a traditional pairing and the woman counter-offers by accepting the pairing but rejecting the traditions.

Characters who buck tradition are featured prominently in A Song of Ice and Fire, and little Arya Stark is one of them. So it's no wonder how the song relates to Arya and why it features in her chapter, even if marriage, romance and sex are still years to come for Arya, or never to come at all. Her incompatibility with the traditional womanly roles of Westeros is portrayed from the very beginning of the story when she flees from her sewing class and watches her brothers train at swords in the yard. The name that Arya chooses for her sword Needle is symbolic of this incompatibility. Plainly, Arya does not want the marriage-and-motherhood lifestyle that her father presents to her.

Arya cocked her head to one side. "Can I be a king's councillor and build castles and become the High Septon?"

"You," Ned said, kissing her lightly on the brow, "will marry a king and rule his castle, and your sons will be knights and princes and lords and, yes, perhaps even a High Septon."

Arya screwed up her face. "No," she said, "that's Sansa." She folded up her right leg and resumed her balancing. Ned sighed and left her there. (AGOT Eddard V)

The Maiden of the Tree song's placement in Arya's scene highlights that Arya and the Maiden of the Tree are somehow similar, if only according to Tom.

While I won't go into great depth about the character Arya in Forest Love and Forest Lass, (though she is my favorite character!) she and the Maiden of the Tree seem to be echoes of one another through the ages, and that makes the song a cool foresty symbol for an essay about a story in which so much of its mystery resides in its history. Thankfully, however, I'll need to revisit Arya later. Arya plays an important role as our present-day set of eyes upon some important places in Westeros.

Me: https://applesanddragons.home.blog/2022/04/03/forest-love-and-forest-lass/

#asoiaf#literature#asongoficeandfire#forestloveandforestlass#applesanddragons#literaryanalysis#aryastark#nedstark#gendry#fantasy#fiction#agameofthrones#astormofswords#george rr martin

0 notes

Text

Tyrion Shows Us How To Prove Unreliable Narration

A proof of unreliable narration requires three things.

Narration

Narration that contradicts the narration in 1

You must have an explanation for why one narration is more credible than the other.

A fourth and final test is how well the more credible narration matches with the story as a whole, its themes, style, and self-evident character.

In ADWD, Tyrion has just joined the traveling party of Griff.

“No doubt. Well, Hugor Hill, answer me this. How did Serwyn of the Mirror Shield slay the dragon Urrax?”

“He approached behind his shield. Urrax saw only his own reflection until Serwyn had plunged his spear through his eye.”

Haldon was unimpressed. “Even Duck knows that tale. Can you tell me the name of the knight who tried the same ploy with Vhagar during the Dance of the dragons?”

Tyrion grinned. “Ser Byron Swann. He was roasted for his trouble … only the dragon was Syrax, not Vhagar.”

“I fear that you’re mistaken. In The Dance of the Dragons, A True Telling, Maester Munkun writes—”

“—that it was Vhagar. Grand Maester Munkun errs. Ser Byron’s squire saw his master die, and wrote his daughter of the manner of it. His account says it was Syrax, Rhaenyra’s she-dragon, which makes more sense than Munken’s version. Swann was the son of a marcher lord, and Storm’s End was for Aegon. Vhagar was ridden by Prince Aemond, Aegon’s brother. Why should Swann want to slay her?”

Haldon pursed his lips. “Try not to tumble off the horse. If you do, best waddle back to Pentos. Our shy maid will not wait for man nor dwarf.” (ADWD Tyrion III)

Haldon Halfmaester doesn’t like Tyrion. Since Haldon is from Westeros himself and an educated man, being a Maester, he recognizes Tyrion’s name Hugor Hill to be a lie immediately. Haldon improvises a little pop quiz about Westerosi mythology, apparently in an attempt to expose the falseness of Tyrion’s name.

Tyrion answers the first question correctly, thwarting Haldon’s reveal, which causes Haldon to challenge him again with a harder question.

“Can you tell me the name of the knight who tried the same ploy with Vhagar during the Dance of the dragons?”

Tyrion answers with the name Ser Byron Swann, which Haldon apparently agrees with, because Haldon doesn’t object to the Byron part of Tyrion’s answer.

Then Tyrion corrects Haldon on the identity of the dragon that roasted Byron.

Haldon corrects Tyrion back, citing the book The Dance of the Dragons, A True Telling by Maester Munkun.

Tyrion rejects Haldon’s counter-correction, citing the writings of Ser Byron Swann’s squire. The squire was eye-witness to the event in question, and he wrote a letter to his daughter in which he named Syrax, rather than Vhagar, as the dragon that killed Byron.

This little duel of knowledge between Tyrion and Haldon is the story’s way of showing the reader how the reader should handle suspect unreliable narration.

First, there is some narration: Ser Byron Swann was killed by Vhagar in The Dance of the dragons.

Second, there is some narration contradictory to the other narration: Ser Byron Swann was killed by Syrax in The Dance of the dragons.

Third, Tyrion and the reader are left to deliberate the truth of the situation.

The first thing we can do is weigh the credibility of the sources. Who is a more credible source regarding the identity of the dragon that killed Ser Byron Swann? Maester Munkun or Ser Byron’s squire?

Maester Munkun’s account is a third-hand account, while the squire’s account is a first-hand eye-witness account. So based on that, the squire is the more credible source.

It’s possible that some unusual circumstance could cast the squire in a more- or less-credible light. For example, perhaps somewhere in the story canon there exists a comment that Ser Byron’s squire was an infamous liar, that the squire never had a daughter, or that he didn’t know how to write at all. Likewise, it’s possible that some unusual circumstance could cast Maester Munkun in a more- or less-credible light. Perhaps somewhere in the story canon there exists a comment that Maester Munkun had a bad memory when it came to the names of dragons.

However, I have no grounds to assert that an unusual circumstance like that exists until and unless one has been found in the story. So the squire wins the battle of credibility by a large margin by having an in-person perspective on the event.

The next test for unreliable narration is to check how well each competing narration fits with the story canon as a whole.

Haldon pursed his lips. “Try not to tumble off the horse. If you do, best waddle back to Pentos. Our shy maid will not wait for man nor dwarf.”

Haldon responds to Tyrion’s counter-counter-correction with body language and a reply that both suggest that he’s not happy about losing their contentious little duel of knowledge. It suggests that Haldon knows that Tyrion is correct about Storm’s End and by extension Ser Byron Swann siding with Aegon in the war. This is apparently knowledge common and certain enough that Haldon can’t refute it, despite wanting to best Tyrion very badly.

And when I think about it, it wouldn’t make a lot of sense if Storm’s End siding with Aegon was not common knowledge among everybody who has studied The Dance of the dragons even a little bit. Storm’s End is one of only a dozen or so major castles in Westeros, and The Dance of the dragons was one of the most significant wars in Westerosi history.

Since the squire’s account that Syrax killed Byron matches with the overarching “story” of The Dance of the dragons, and since Maester Munkun’s account that Vhagar killed Byron contradicts it, it suddenly becomes incredibly obvious which account is the truth.

Byron was fighting on the side of Aegon, and Vhagar was Aemond’s dragon, and Aemond was Aegon’s brother, and Aemond sided with Aegon, so it doesn’t make sense to suppose that Vhagar was the dragon Byron confronted. Coming at it from the other angle, Byron was fighting against Rhaenyra, and Syrax was Rhaenyra’s dragon, so it makes sense to suppose that Syrax was the dragon Byron confronted.

In this way, unreliable narration rewards the reader (symbolized by Tyrion in this scene) for challenging its narrative (symbolized by Haldon’s narrative) by thinking critically about character motivations, loyalties, behaviors, and taking the time to allow easy-to-gloss-over details like the names of dragons and their riders to unfold and breathe in his imagination, experiencing the world vicariously and more like the characters experience it, and thereby allowing him to remember and notice things better.

For a spice of irony, the author even had Maester Munkun name his book “A True Telling”, as if naming a falsehood true can make it so. The irony paints Maester Munkun as incompetent, arrogant, perhaps desperate for acclaim, or perhaps nefarious. And it paints Haldon and readers who defended the unreliable narration as inattentive or gullible.

To the extent that I’m made by the story to appear gullible, the story’s critique of me is tongue-in-cheek, because, after all, the presupposition that the reader can trust the story to tell him the truth about its narrative is implicit in the story’s very existence, because it’s implicit in the very act of telling a story. ‘Why would a storyteller tell a story at all if he were going to falsify the narrative?’

Well, as if it wasn’t clear enough already, A Song of Ice and Fire is unusual fare among stories. This one is teaching us how to think.

Main blog: applesanddragons.home.blog

#asoiaf#asongoficeandfire#tyrion lannister#literature#literary analysis#george rr martin#adancewithdragons#unreliable narration#fantasy#fiction

0 notes

Text

Dothraki Superstition: Strength Right

Excerpt from the essay Dothraki Superstition by Apples and Dragons

Strength Right

The fundamental attitude at the heart of Dothraki society is one I will call Strength Right. It’s the attitude that the strong have the right to rule and take from the weak.

“They took Khal Drogo’s herds, Khaleesi,” Rakharo said. “We were too few to stop them. It is the right of the strong to take from the weak. They took many slaves as well, the khal‘s and yours, yet they left some few.” (AGOT Daenerys IX)

The primacy of strength can be seen all throughout Dothraki beliefs and behaviors, such as in their propensity for conquest and enslavement. Strength Right can be seen influencing Dothraki society in subtler ways, too. For example, the growth of a trade economy is stunted due to the Dothraki attitude that trading is unmanly.

For us, however, the only true importance of Vaes Dothrak is the trading that takes place there. The Dothraki themselves will neither buy nor sell, deeming it unmanly, but in their sacred city, by leave of the dosh khaleen, merchants and traders from beyond the Bones and the Free Cities come together, to haggle and exchange goods and gold. (TWOIAF: Beyond the Free Cities, The Grasslands)

Though manliness and strength aren’t exactly the same thing, they’re particularly indistinguishable in everyday Dothraki life.

However, wherever manliness is an inadequate description of strength, I find Dothraki society beginning to break down.

They want a glimpse of dragons to tell their children of, and their children’s children. (ASOS Daenerys III)

To own baby dragons, for example, affords the owner much influence and power, but it isn’t a kind of power or influence that the word “strength” describes quite as well as it describes more traditional kinds of strength, such as physicality.

Wealth is another kind of power that doesn’t fit neatly into this masculine concept of strength. Trade is a system of wealth creation that doesn’t directly involve physicality, so it’s an area where Dothraki society encounters its limitation, unable to accommodate the innovation of trading at large scale due to the mismatch between “masculine strength” and “power,” or “masculine strength” and “influence.”