Text

The Effect of Cubicles an essay about my chemical romances song cubicles:

My Chemical Romance released I Brought You My Bullets, You Brought Me Your Love in 2002. It’s a messy yet passionate start to kick off their catalog of concept albums. Lyrically, Bullets reads like an anthology. Telling tales of two lovers, addicted and infected, by pills and vampires, until death do them part when they are shot dead. It has a variety of stories and goes through many different moods. All set in a punk rock, basement recorded world.

Because of its variety, it’s not uncommon to hear any of the songs off it as someone’s favorite My Chemical Romance song. Though one song always sparks controversy- “Cubicles.” It has a polarizing reputation, with one side loving its embrace of loneliness and the path to get there. The other side only hearing overdone emo whining.

The album begins with “Romance,” an acoustic guitar intro. From there, the second song builds with sharp distorted electric guitar and classic punk drumming, taking us into the terrorized, angry heart of the album. The records A-side follows two lovers fighting to stay alive in a world of vampires while learning to trust each other. “Drowning Lessons” shows these lovers as one kills the other time and time again. When we reach the end of the A-side we get the first song solely about this rough sketch of a main character, “Headfirst for Halos.”

Set with high pace anger and poignant quiet sections, the album has a consistent drama. Even though most songs are different in how they express that drama, the whole picture stays cohesive with its intensity. Two songs, “Early Sunsets Over Monroeville’’ and “Demolition Lovers,” travel through crescendos that build slowly throughout the entire song. While others like “Our Lady of Sorrows” and “Headfirst for Halos” stay at an in-your-face tempo. The individual stories in each song are fully committed to. That consistent intensity is what makes Bullets work so well.

When the listener reaches the B-side, they find not another short story, but “Skylines and Turnstiles.” It’s about 9/11. It’s an offering of consolation with depictions of what singer, Gerard Way, saw that day. It’s the only other song set unarguably in the real world. Yet it still fits it nicely into the album by staying with the drama. Additionally, its placement as the first B-side recognizes how different the story being told is compared to the others. It’s a thematic break, a checkpoint. The listener has to manually flip over the record and replace the needle to get to it.

After two more fiction-based songs, we now reach “Cubicles.” Placed right after one of the most genuinely happy songs, and right before on the most storybook intense songs. It’s the second to last song on the album. “Cubicles” is about the unnoticed writer and his crush. Detailing an office romance that never was, as the love interest switched jobs before the character has the courage to make a move. Its stakes are shockingly low as Way details photocopying and sterile views. Similar to the other two crescendoing songs, it too builds into a declaration of wanting to die alone.

“Cubicles” presents the listener with another tonal shift. It disrupts the onslaught of fantasy to show a dull reality. “Cubicles” romance is already on a small scale and when compared to the other songs, it’s almost comical. After it establishes itself as being lower stakes, the statement piece kicks in, “I think I’m gonna die alone.” It inflates itself by claiming that it is as big as the others. The other crescendoing songs had the stakes to pull this off, “Cubicles” doesn’t. It values this feeling, this longing and awkward pain, on the same level as loss and addiction. But maybe that’s part of the point.

The character realizes at the end of the song that these little life moments can be pieced together to be this overwhelming thing that takes over his life. He’s not just speaking about the one crush, it’s the many others that have also been replaced. While a lot of the verse lyrics focus on the daydreams of the writer, the chorus emphasizes what took away the love interest. It’s a short chorus with a subtle message about their non-stop corporate workplace. The three-by-four workers are constantly being replaced creating this emotional hole. “It happens all the time.” As Alice Maney puts it,

“Like to the system, everyone is just a cog in the machine, but for the people working in the system it matters who’s next to them, they create social connections that get ripped away and replaced.”

This gives the song more depth. It’s not just about insignificant crushes, it’s about the overarching nature of his workplace. It’s able to take something small and see the connections to the rest of his life.

Let’s look at Bullets without Cubicles for a minute. This makes nearly every song have a fictional or life threatening story to them. All of the songs are so saturated in theatrics that at some point it can become a blur. The intensity solidifies its identity but it also makes this high point of tension flat line.. There’s nothing to shock the listener back.

“Cubicles” shatters that and makes it bigger. Theatrical and down to earth. It’s the only honest song about a boring life. Where the romances aren’t star-crossed, they’re watercooler. Where they don’t end with being shot in the desert, they’re constantly ending when people quit and are replaced. It makes the album theatrical and down to earth.

“[It’s like] wanting romance and a real connection but everyone sucks and nothing ever works out so you just kill that dream but doing so you kill a large part of yourself and living doesn’t feel worth it anymore- and then it kicks into “Demolition Lovers”.”

Says Summer Johnson.

And yet these huge revelations about the character can be born out of his mundane job. Only then does the song aggregate into a complicated tragedy. We see a normal man descend into loneliness. This carries us into the grand finale of the album, a six minute epic where the lovers are murdered once again. “Cubicles” amplifies the climax creating a certain kind of finality to the deaths that can’t be achieved without it. It breaks the cycle to prepare the listener for this instead of just having the last song glaze over.

“Cubicles” is a break from all of the fiction to hear about the guy who might as well be daydreaming the whole album. In comparison it might feel whiny but it breaks up the album to re-engage the listener before sending them off to the last song. It’s not the most well-crafted My Chemical Romance song but it doesn’t have to be for its place on Bullets to be undeniable.

—

a/n: thank you for reading! quotes by me friendz <33

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

spent all day on this and the draft is DONEE! ANL!!!

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

LINKS: download (free, print + web) | flip through

I ♥ MCR. this zine is my love letter to the band. joined by 8 other amazing writers (some who designed pages), i wrote about my two favorite things: this band and cinema. i started this project in the latter half of 2023, but finished the majority of it this month. i love it. i hope to make more issues in this series. for now, enjoy ALL NIGHT LONG #1. follow @allnightlongzine where i reblog all ANL news and an occasional essay about mcr.

tagging contributors: @torotits @/cd_suitcase @catgirl-vampireboy @sapphicdude @alien-romantic @georgiabread

224 notes

·

View notes

Text

“How I Discovered My Chemical Romance 15 Years After the Rest of the World”

May 25, 2020 | Scott Raymer | concertcrap.com

To obsess or not to obsess. That is the question. My apologies to Shakespeare. I tend to lack focus in many aspects of my life. Bouncing back and forth between learning a foreign language, playing guitar, photography, and many other endeavors. However, when it comes to music I can become obsessed and fixated on a single artist, song, or album. I mostly ignore radio and have a habit of listening to a single artist for months or sometimes years while ignoring others. I have gone from the Beatles to Olivia Newton-John to Duran Duran to Green Day to Amy Grant to Sum 41 to the Sick Puppies back to Green Day. The result is that I miss out on a lot of great music unless I manage to catch something on TV, due to not paying attention.

Sometimes it can take me years to discover a band. This happened recently. Around six months ago I started seeing all this chatter on Facebook about this band called My Chemical Romance. My Chemical Who? The name triggered some deep memories making me think that maybe I had heard the name before. A quick search of Apple Music displayed a long list of songs by the band. The first song on the list was “Welcome to The Black Parade”. I clicked on the song title and began listening to see why people were so excited about this band. It started off with a slow piano intro, followed by some mellow vocals by Gerard Way, which gradually increased in intensity. I was rapidly losing interest and the finger was just getting ready to swipe the app closed when at 1:48 into the song, Ray Toro and Frank Iero’s guitars kicked in. My finger instantly pulled away from my phone. I started listening intently and by the time Way got to “And through it all, the rise and fall, The Bodies in the streets” I was hooked.

Moving down the list brought songs like “Teenagers”, “Helena”, and “I’m Not OK”. Even though I am long past my teenage years and missed the Emo movement by a couple of decades, these are all songs that I can still relate to and which take me back to life as a depressed, harassed, bullied, suicidal tempted teenager. Some of us never truly become OK. When I got to “Famous Last Words”, I was totally blown away and my obsession began.

One of the things I find interesting about the great bands is how they transform and evolve. I saw this in both of my favorite bands, the Beatles and Green Day. The Beatles first US album Meet The Beatles was raw and packed full of energy, but with musicianship which was somewhat lackluster. As they progressed from album to album, you could hear the music getting more and more polished; the lyrics getting more complex; culminating in their concept album Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Green Day displayed a similar evolution going from Kerplunk to Dookie to their rock opera American Idiot, with Billie Joe Armstrong transforming his guitar abilities all along the way.

I feel My Chemical Romance’s evolution was more dramatic than either The Beatles or Green Day. It’s relatively easy to classify both the latter band’s music without much debate. However, there is no consensus on My Chemical Romance. Each of their four studio albums, I Brought You My Bullets, You Brought Me Your Love, Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge, The Black Parade, and Danger Days: The True Lives of the Fabulous Killjoys are each unique and show Way and the band transitioning from punk to emo/post-hardcore to pop-punk with a half-dozen other genres thrown in the mix. It was as if the band purposely hit the reset button attempting to reinvent themselves with each album.

Not only did the band reinvent themselves with their music, but also with their look. Way changed his appearance throughout the band’s dash through the first decade of the new millennium. Going from a dark emo goth in Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge, to a Sgt Pepperish platinum blonde look for The Black Parade, to pop punkish red hair for Danger Days. This change symbolizes what I admire most about the band; a constant changing flux of identity. It is hard to get bored with a band that is always striving to do something different. A band not content with where they are now but being in constant pursuit of what they can become.

It’s been seven years since we last saw the band. I can’t wait to see want the next evolution will bring. This is no longer a band of restless youths. It is a band now composed of husbands and fathers, hitting middle age in a new decade. How will this influence the direction of the music? We will have to wait and see. All I know is that of my litany of musical obsessions, this one may be the hardest one to overcome. Ten years from now I may still be listening to the band, looking back, and wondering what happened in the rest of the music world.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Eternal March of the Black Parade

Twenty years after their debut album and more than a decade after the critics dismissed them, My Chemical Romance stands as one of the greatest rock bands of the 21st century. How did we end up here?

Rob Harvilla | Jul 26, 2022 | theringer.com

Illustration by Brent Schoonover

My Chemical Romance is touring again, Paramore and Jimmy Eat World are headlining a major festival this fall, and there’s a skinny, tattooed white dude with a guitar dominating the charts. In case you haven’t heard, emo is back, baby! In honor of its return to prominence—plus the 20th anniversary of the first MCR album—The Ringer is following Emo Wendy’s lead and tapping into that nostalgia. Welcome to Emo Week, where we’ll explore the scene’s roots, its evolution to the modern-day Fifth Wave, and some of the ephemera around the genre. Grab your Telecasters and Manic Panic and join us in the Black Parade.

Our story starts in New York City on September 11, 2001. It just does. Suspend your disbelief; respect his audacity. But is it really so hard to believe, and is it really so audacious, that Gerard Way—then a 24-year-old New Jersey native, NYC art school graduate, and creatively stifled Cartoon Network intern—would choose that awful, vulnerable, crushingly human moment to reimagine himself as something immortal, someone superheroic? “That felt like the end of the world,” he told Newsweek in 2019. “It felt like the apocalypse. I was surrounded by hundreds of people on a dock on the Hudson River, and we watched the buildings go down, and there was this wave of human anguish that I’ve never felt before. Since then, I’ve continued to think about what we would do at the end of the world if we knew we only had a little time left.”

Standing on that dock, what Gerard decided he would do was channel his shock and grief and newfound sense of immediacy into the ultimate rock-star origin story. “Something just clicked in my head that morning,” he told Spin magazine in 2005. “I literally said to myself, ‘Fuck art. I’ve gotta get out of the basement. I’ve gotta see the world. I’ve gotta make a difference!’” So he hooked up with a drummer friend from high school named Matt Pelissier (the first of several drummers, alas) and wrote an anguished, furious, and yet startlingly tender pop-punk song called “Skylines and Turnstiles.” It starts like this.

You’re not in this alone

Let me break this awkward silence

Let me go, go on record

Be the first to say I’m sorry

Hear me out

Gerard sang and played guitar, though he struggled to do both at once. (It’s harder than it looks.) Slowly, he found other bandmates: Ray Toro and Frank Iero on guitars, plus his own younger brother Mikey Way on bass. Thanks to his gig working at Barnes & Noble, Mikey also contributed a band name: My Chemical Romance, an improvement on the title of an Irvine Welsh book. The band signed with a tiny label called Eyeball Records and released, on July 23, 2002, their debut album, called I Brought You My Bullets, You Brought Me Your Love, produced by New Jersey punk deity and Thursday frontman Geoff Rickly, who’d already mastered the dark art of combining the rawest possible materials into something impossibly gargantuan.

This broken city sky

Like butane on my skin

Stolen from my eyes

Hello angel, tell me

Where are you?

Tell me where we go from here

“Skylines and Turnstiles” is not, by a long shot, the highlight of MCR’s least-great album. The raw materials are there, of course: the scabrous and shimmering guitars, the breathless downhill-sprint propulsion, the throat-shredding screams to bolster the chorus and punctuate Gerard’s unguarded and brutal horror-flick lyricism. But your first song is never your best. Here, the one called “Honey, This Mirror Isn’t Big Enough for the Two of Us” is better. And the one called “Vampires Will Never Hurt You,” and the one called “Demolition Lovers,” and the one called “Drowning Lessons,” and even the one called “Cubicles.” But as an opening salvo, as the gritty first panel in a dense and ludicrously ambitious comic-book-punk saga, as an achingly sincere attempt to break the awkward silence and roll back the wave of human anguish, as a macabre but heartfelt attempt at genuine connection, Gerard Way’s first song got him where he needed to go, which was firmly on the road to leading everyone where they needed to go.

And after seeing what we saw

Can we still reclaim our innocence?

And if the world needs something better

Let’s give them one more reason, now

It’s the rousing, heartbreaking vocal harmony on the words the world needs something better that shows you what Gerard and his vampiric cohort is really about. Look beyond the eyeliner, the hair dye, the ghostly pallor, the extra-macabre marching band outfits, the wholesale mall-goth hijacking of this band’s whole look, its whole ethos. Don’t flinch at the lyrics no matter how gnarly and nihilistic they seem to get; don’t get too wrapped up in the surreal sensationalism of their flames-and-chaos music videos. Buy the album tie-in comic book or don’t. Just never forget that the closer we get to the end of the world, the tighter Gerard Way means to hold us, to make however much time we have left just that much more bearable.

I Brought You My Bullets, You Brought Me Your Love just celebrated its 20th birthday, and inspired some very excellent anniversary pieces despite being, well, MCR’s least-great album. Their next record was a gleaming and snarling major-label-debut colossus that crowned the fellas as Warped Tour royalty; the record after that was a hilariously overblown rock-opera funeral march and consensus masterpiece that now stands among the greatest emo albums ever born, any era, any wave; the record after that is my personal favorite. Then MCR broke up in 2013, to appropriately operatic dismay, going out as close to On Top as a youngish rock band possibly can.

There was no explicit tabloid-roiling catalyst, no real drama, except no drama is not exactly this band’s vibe. Gerard’s farewell letter, posted to Twitter three days after the news broke and titled A Vigil, On Birds and Glass, is my personal favorite Rock Band Breakup Explanation Letter, any subgenre, any era, precisely because it captures this band’s precise and fantastic combination of galactically overwrought and unabashedly intimate.

We were spectacular.

Every show I knew this, every show I felt it with or without external confirmation.

There were some clunkers, sometimes our secondhand gear broke, sometimes I had no voice- we were still great. It is this belief that made us who we were, but also many other things, all of them vital-

And all of the things that made us great were the very things that were going to end us-

Fiction. Friction. Creation. Destruction. Opposition. Aggression. Ambition. Heart. Hate. Courage. Spite. Beauty. Desperation. LOVE. Fear. Glamour. Weakness. Hope.

Fatalism.

And then he expands on the fatalism part as a way of explaining why, exactly, this band broke up after only 11 years and four albums.

That last one is very important. My Chemical Romance had, built within its core, a fail-safe. A doomsday device, should certain events occur or cease occurring, would detonate. I shared knowledge of this “flaw” within weeks of its inception.

Personally, I embraced it because, again, it made us perfect. A perfect machine, beautiful, yet self aware of its system. Under directive to terminate before it becomes compromised. To protect the idea- at all costs. This probably sounds like something ripped from the pages of a four-color comic book, and that’s the point.

No compromise. No surrender. No fucking shit.

To me that’s rock and roll. And I believe in rock and roll.

He goes on at great length. It’s wild, it’s lovely, it’s absurd, it’s genuinely moving. The fellas found stuff to keep them busy post-breakup, and Gerard most prominently, of course: the solo album, the ongoing and relentlessly off-kilter Netflix series based on his comic book. And then, inevitably, MCR reunited—tentatively in late 2019, and full-throatedly here in 2022, headlining giant festivals and packing arenas as what certainly feels like the first rock-band reunion that anybody’s actually given a shit about in years. Put it this way: If you are a remotely young person who, like Way himself, still believes in rock and roll, My Chemical Romance is very likely why, and it’s worth ruminating on how, exactly, this profoundly strange and desperately necessary band has inspired such belief. Anybody who listened to I Brought You My Bullets in 2002 couldn’t have predicted any of this. But the guys who made it did.

Emo is back, baby! In honor of its return to prominence—plus the 20th anniversary of the first MCR album—we’re diving deep into all things emo.

Grab your Telecasters and Manic Panic and join us for Emo Week.

The most striking song on I Brought You My Bullets—the most Gerard song, the most MCR song, The Most in general—is called “Early Sunsets Over Monroeville.” It begins as a woozy but deceptively gentle waltz but darkens by ominous degrees, and soon Gerard is wailing the line “If I had the guts / To put this to your head,” and maybe you worry for a second that this is the 200,000th uncouth and unnervingly violent post-breakup emo song. And then you find out that Monroeville is in Pennsylvania, and parts of George Romero’s 1978 zombie-flick classic Dawn of the Dead were shot there, and oh, wow, suddenly you realize this is actually a very grim, very romantic song about an inconsolable man realizing he has to kill his no-longer-human wife:

And there’s no room in this hell

There’s no room in the next

And our memories defeat us

And I’ll end this duress

Not the best song, but the most. My Chemical Romance would get truly dangerous, and truly great, when their best and their most intertwined. They signed to a major label; all the coolest kids do. Deal with it. Deal with this, while you’re at it.

“You like D&D, Audrey Hepburn, Fangoria, Harry Houdini, and croquet,” Ray Toro informs Gerard Way at the onset of “I’m Not Okay (I Promise),” one of several monster singles from their 2004 Reprise Records debut, Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge. “You can’t swim, you can’t dance, and you don’t know karate. Face it: You’re never gonna make it.” Cue the high-school-outcast histrionics, the cuddly arena-punk viciousness, Gerard’s destabilizing magnetism as he practically screams in your face, the vintage airbrushed-van metalhead radness of Ray’s guitar solo, and, before the final bone-crushing chorus, a truly bonkers Gerard buildup/breakdown for the ages:

But you really need to listen to me

Because I’m telling you the truth

I mean this

I’m okay

(Trust me)

And, boom. There are days when this is the best song ever written. And there are other days when it’s not even the best song on Three Cheers: “Helena” has a majestic Mötley Crüe meets the Misfits chorus, the power chords ascending a stairway to hell, an infinite legion of demons pumping their fists along to every word: So long and good night / So long and good night. Or maybe the power-ballad pyrotechnics of “The Ghost of You” do it for you, the classic quiet-verse-loud-chorus dynamics, Gerard’s unapologetic controlled-screaming melodrama (“At the top of my lungs in my arms / SHE DIES”), the extra-luxe video that recreates D-Day down to the puking soldiers landing on the beach. Tell me these guys aren’t spectacular, and not driven by friction, ambition, LOVE, glamour, and fatalism.

By 2005 MCR are headlining the good ol’ Warped Tour alongside Fall Out Boy, and early-2000s third-wave emo—undaunted in its embrace of pop-punk, of the mall, of teenagers both actual and perpetual—has its very own Queen, and/or Led Zeppelin, and/or Pink Floyd. Suspend your disbelief; respect their audacity. “The main thing that we’ve always wanted to do was to save people’s lives,” Gerard informed the magazine Alternative Press in 2004. “That sounds Mother Teresa–ish and outlandish, but it really does happen. It does make a huge difference. We’ve seen it in action.”

Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge, by the way, is a semi-derailed concept album involving two lovers, a man and a woman, who both seemingly die in a gunfight: The man goes to hell, is informed by the Devil that the woman is still alive, and agrees to kill 1,000 evil men in exchange for the chance to reunite with her. I say semi-derailed because during the writing process Gerard and Mikey’s beloved grandmother died—“Helena” is about her—and Gerard considered scrapping the whole thing. “When that happened, I was like, ‘Fuck. Oh, God. How am I going to deal with this story? Does it even matter anymore? Is it just fucking pretentious? Is it bullshit?’” he told Alternative Press. “And then I came to grips with it and said, ‘Fuck it. I’m going to write the songs that I want.’” Even the song called “You Know What They Do to Guys Like Us in Prison” has a certain funereal poignancy to it.

Even for a band already operating at this scale in terms of both ungodly rock-star bombast and naked emotional intimacy—Gerard has gotten increasingly forthright in interviews about his struggles with mental health and substance misuse in this era—My Chemical Romance’s third and biggest and most extravagantly beloved album, 2006’s The Black Parade, struck like a thunderbolt from a clear blue sky. There is an awful lot to absorb here; the marching-band outfits are as good a place to start as any.

The Black Parade is a classic leveling-up record, the fairly conventional tale of a young, ferocious rock band hitting its commercial peak (the album debuted at no. 2 on the Billboard album chart, behind a Hannah Montana soundtrack) with the help of some new big-shot collaborators. It was produced by Rob Cavallo, who probably also produced your favorite Green Day album; the screaming-and-fire video for “Famous Last Words” was directed by Samuel Bayer, who also directed your favorite Nirvana video. (I’m just assuming your favorite Nirvana video is “Smells Like Teen Spirit.”) Several members of the band got severely injured while shooting this, by the way, and somehow you can just tell.

The Black Parade is also an unprecedented and not-at-all-conventional narrative flex credibly described by The New York Times as “a stricken tour de force about coming of age in the post-9/11 era.” It’s a not-at-all-derailed concept album about a man (“The Patient”) dying of cancer while wracked by fear and regret; Gerard decided to add to the verisimilitude by cutting his hair short and dying it a stark silver. (“I wanted to appear white and deathlike and gaunt and sick-looking,” he cheerfully told the NYT.) Liza Minnelli (“I love those guys”) drops by to portray a grieving mother; musically, the klezmer parts somehow hit harder than the heavy metal parts. Influences range from David Bowie to KISS to the Beatles; there is also, as the marching-band uniforms might suggest, a marching band. The scale of this, in every sense, is nearly overwhelming, so if you’re new to it all maybe start out by just putting the caustically hilarious goth-blues anthem “Teenagers” on repeat for six hours.

They said, “All teenagers scare the livin’ shit out of me”

They could care less as long as someone’ll bleed

So darken your clothes, or strike a violent pose

Maybe they’ll leave you alone, but not me

Even five years ago, this record was an easy fan favorite but not necessarily an agreed-upon, era-defining masterwork. “The Black Parade, though well-reviewed at the time, hasn’t accrued the same reputation as other classic albums,” the critic Jeremy Gordon wrote in 2016 in a 10th-anniversary piece for Spin. “It was almost entirely ignored in lists of the best albums of the ’00s run by tastemakers and canon-formers like Rolling Stone, Pitchfork, Stereogum, Billboard, Paste, Complex, NME, and, yes, Spin.” By this record’s 20th anniversary, however, it might be universally hailed as the pop-punk Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band: In 2020, when Rolling Stone unveiled its updated list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time, there was The Black Parade at no. 361, not quite as good as Funkadelic’s One Nation Under a Groove, but just a little better than Luther Vandross’s Never Too Much.

You could argue that rock critics ruin everything. You could regard The Black Parade’s steady ascent on lists like this as proof that something essential—a life-affirming secret shared only between MCR and their Day One fans—is being lost. As a Late Pass–holder myself, out of respect/trepidation, I have decided not to argue that the band’s fourth and last album, 2010’s Danger Days: The True Lives of the Fabulous Killjoys, is actually their best album, even though I love it profoundly for both the reliable audacity of its concept (now MCR are Mad Max–esque rebels battling an evil corporation in postapocalyptic California, with the Gerard-penned comic book to prove it) and the chaotic scope of the songs themselves. Get acclimated by putting the song “Na Na Na (Na Na Na Na Na Na Na Na Na)” on repeat this time.

Danger Days probably includes one too many songs that blatantly reach for Coldplay-style arena-rock uplifting grandeur, but what I will say is that this record’s final attempt at volcanic sentimentality, “The Kids From Yesterday,” totally works, and the album ends with an extra-caustic and extra-hilarious trashing punk tirade called “Vampire Money,” in which Gerard politely declines to contribute a song to the soundtrack of a Twilight movie.

(Come on!) When you wanna be a movie star

(Come on!) Play the game and take the band real far

(Come on!) Play it right and drive a Volvo car

Pick a fight at an airport bar

The kids don’t care if you’re alright, honey

Pills don’t help, but it sure is funny

Give me give me some of that vampire money, come on!

“Originally, what we did was take goth and put it with punk and turn it into something dangerous and sexy,” Gerard explained to the NME. “Back then nobody in the normal punk world was wearing black clothes and eyeliner. We did it because we had one mission: to polarize, to irritate, to contaminate. But then that image gets romanticized and then it gets commoditized.”

This is all delightfully but decidedly rude: There’s an excellent argument that the Twilight universe is every bit as vital and inclusive and life-affirming as any of the rock bands it attempted to romanticize and/or commoditize. But I will laugh at the line Pick a fight at an airport bar forever.

As for MCR’s breakup, and the failsafe doomsday device that triggered it, within a few years Gerard was opening up about it: In 2014 he told the NME that he’d relapsed into alcoholism after Danger Days, and worried that his daughter would grow up without a father; the choice, he concluded, was “Break the band or break me.”

The band first reunited for a single show in 2019 in Los Angeles: “That was definitely the most fun I’ve ever had playing on stage with My Chemical Romance, for sure,” Gerard told the NME, adding that “to me, the new version of My Chemical Romance and the way I want to go about it is exercising less control.” (The NME loves this guy.) The band’s festival-headliner status now is in part a reflection of pop-punk’s bizarrely ascending reputation in the past five years as both a commercial and critical proposition, from Olivia Rodrigo to Machine Gun Kelly to Juice WRLD. But however many sonic and stylistic precedents there might be, there has never been a rock band quite this courageous, spiteful, beautiful, desperate, glamorous, hopeful.

I believe Gerard when he says that this band’s original mission was “to polarize, to irritate, to contaminate,” but that was never their only mission. MCR was born in an apocalypse, and designed to help us all survive it. Us meaning actual teenagers, not critics, but we caught on eventually. We are all bandwagoners on the Black Parade now. Meanwhile, the apocalypse is closer than ever, but at least we can all huddle together in the glow.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Poet Hanif Abdurraqib Can’t Live Without | Feb 12, 2021 | nymag.com

5. “We’ve All Seen Helena” by Lip Manegio (shop link)

Lip is a great poet. This book is one that I kind of wish I wrote at the time when I was first in love with My Chemical Romance and emo and the goth exterior that I kind of still carry. The book is a real complex and varied love letter to a group, to a song, to an album. It’s a brave meditation and turns a passion and excitement around as many times as possible until you get to the bottom of it. That’s kind of what I try to do in my work, but I don’t always succeed. And this book feels like a real success in that vein. This person loves something in a similar way that I love it.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Join The Black Parade: My Chemical Romance And The Politics Of Taste

Daoud Tyler-Ameen | OCTOBER 21, 2016 | npr.org

Sunday is the 10th anniversary of My Chemical Romance's The Black Parade, a defining album for both the band and a generation of pop-punk fans. A decade later, NPR's Daoud Tyler-Ameen is still processing what it means to love this record, and what its impact says about the culture around it.

Click the audio link for his roundtable discussion with Tracy Clayton, host of the Buzzfeed podcast Another Round, and Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib, poet and MTV News columnist — or find it in the All Songs Considered podcast feed. For more on how their conversation came to be, read on.

Common wisdom suggests that the culture you're exposed to in your teens and early 20s ends up informing your taste for the rest of your life. For most people, those years are where the very notion of taste begins. Books, movies, music, fashion, friends: You realize you have options, and you reject the ones that don't match your idea of who you are. The stuff that does stick — be it posters on a wall, patches on a jacket, a dog-eared paperback stuffed in a back pocket — you add to your coat of arms, self-definition by way of curation. What you like informs your understanding of what you are like, and vice-versa.

But every so often, taste leads you somewhere complicated. Sometimes you love a piece of art, but not what that love says about you — and the self-portrait you've so rigorously composed threatens to flake away. This is where I was 10 years ago, when My Chemical Romance released its third album and crowning achievement, The Black Parade.

In 2006, amid the rising tide buoying the fates of Fall Out Boy, Paramore and Panic! At The Disco, My Chemical Romance was as just about as big as it got. This was a boom era for the kind of band whose LPs are stocked at Hot Topic, but the Jersey quintet had always seemed to aim beyond its base. MCR had come out of nowhere with 2004's Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge, an album born of hardcore but ringed with enough melody and melancholy that all stripes of emo and pop-punk buffs could find themselves in it, too, resulting in sales that zoomed past Warner Music's 300,000-unit target on the road to platinum status. The record had hits, it had hooks, and it had reach, especially once the cinematic visuals for "Helena" and "The Ghost of You" found their way to MTV. Crucially, it also had a sense of humor — see the video for "I'm Not Okay (I Promise)," in which freaks-versus-jocks teen comedies are skewered with note-perfect precision — which meant I couldn't dismiss the band as some self-serious Marilyn Manson hangover, even if singer Gerard Way did favor eyeshadow and funeral garb. Three Cheers was really, really good, and that was a problem for me.

Emo had found me in 10th grade, when a two-month relationship left me with a bruised heart and a taped copy of The Get Up Kids' Red Letter Day EP, and had followed me to Yale, where I hipped my freshman roommate to Dashboard Confessional. My Chemical Romance's music was not itself the issue — rather, it was the scale of the thing. This band was so popular, so grandiose — and thus, it was also a punching bag, derided as "mall punk" by the same people who had a few years earlier indicted Britney and *NSYNC as signs of the apocalypse. At a moment when mannered indie-pop and roughshod garage-rock were infiltrating the mainstream, MCR was earnest, dramatic and unapologetically massive, in a way that made it conspicuously uncool. And for me — a gawky black kid at a fancy white university, feeling very much stuck between identities — uncool seemed like the worst possible thing to be.

Writer Carvell Wallace has described the struggle this way: "Having black skin but liking white things is a little like walking on a tightrope ... You have white friends with whom you can never talk about race but you avoid groups of black people because you fear they will hear what's in your headphones and call you out as a traitor." Those words come from a Pitchfork Review profile of TV on the Radio frontman Tunde Adebimpe, with whom Wallace had overlapped years before as an NYU undergrad, and identified as a kindred square peg — the kind of black kid who might not take great care of his sneakers but would agonize over which ratty band T-shirt to wear to a party. That's the needle I was threading when MCR arrived in my life: wrapping myself in thrift-store accessories, loudly claiming bands like TV on the Radio as my heroes, positioning myself as the kind of black bohemian (Pharrell and Basquiat come to mind) who can move between cultural groups by dint of the fascination he inspires.

This version of me wasn't a lie, just a selective presentation of the truth. But committing to My Chemical Romance, which in spite of its success was scorned far and wide as mass-market histrionics for sad teens, threatened to shake the myth apart. So I kept my love of Three Cheers to myself. And when The Black Parade arrived, heralded by an orchestral lead single whose video employed period costume, gothic sets and scores of extras, I was mortified — and pushed the band out of my life altogether. I was out of school by then, playing in bands of my own, working office jobs and learning to carry myself as an adult. Even closeted fandom seemed like a bad habit in need of shedding. The inner emo kid, I thought, had to go.

This summer, a cryptic teaser posted to My Chemical Romance's YouTube channel briefly lit up the social web, stoking fevered rumors among those who'd been missing the group since it disbanded in 2013. A day later came the letdown: There was no new album, no reunion tour — just a 10th-anniversary reissue of the record that had come to define the band's career.

Fans took to Twitter to voice their disappointment. Two voices in particular jumped out at me: Tracy Clayton, co-host of the Buzzfeed podcast Another Round with Heben and Tracy, and Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib, a music writer and the author of a remarkable book of poetry called The Crown Ain't Worth Much. Both of them are friends of friends, part of an extended media family that platforms like Twitter have helped to illuminate. Both of them create work rooted in blackness, Tracy in searching interviews that sound unlike any in her field, Hanif in poems that read more like cultural essays, refracting issues like gentrification and police violence through the grammar of hip-hop and pop culture at large. Both of them were legitimately upset that My Chemical Romance was not getting back together. I knew I had to talk to them.

It isn't just that I've come around to The Black Parade in the past year, though that helps: When I finally allowed myself to listen to it all the way through, when I researched its underlying narrative about a cancer patient's journey to the beyond, when I stumbled on live videos of the band dressed in marching gear and corpse paint, the weight of it all hit me over and over and over. The record is a monument, as moving a statement about death as has ever been made. Twenty-two year-old me would have loved it, and loved talking about it. But it may well have taken the media environment of 2016 to show me how to have that conversation — in public, no less.

I don't know how much of this revelation comes from a change in the industry, and how much is just my own senses becoming more finely attuned, but the sheer plurality of black voices that move through my social timelines and podcast feeds these days is such a rich, resplendent comfort. When you can follow the work of not just a handful of black writers and commentators, but dozens upon dozens, running on their own or within enshrined institutions, you stop focusing on how different their perspectives are from the rest of the world — and begin to take notice of the many differences among them. You witness their minor debates, and pick sides. You see and hear them making guest appearances in one another's territory. "Rep sweats" fade from the picture; instead, you take as a given that people of color do and make and like all kinds of things.

And so, to toast the 10th birthday of The Black Parade, I called up two black writers whose work I adore and whose taste I admire, to have the exchange of ideas I wish I'd known how to have way back when. Here's hoping it reaches a few brown kids still learning how to trust themselves.

Andrew Limbong and Brent Baughman provided production support for this story.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life & Death: My Chemical Romance And 10 Years Of 'The Black Parade'

Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib on shared grief, heroism, and survival

Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib | September 8, 2016 | mtv.com

So fake your death

Or it’s your blame

And leave the lights on

When you stay

— My Chemical Romance, “Fake Your Death”

ACT I

In the fall of 2006, I was in the midst of typical early-20s purgatory. Having struck out during my initial pass at adulthood, and cloaked in a sadness that felt directionless, I moved back in with my father — back into my childhood bedroom. This is one of the more romantic failures, the one that takes you back to the place where you started and allows you to stare directly into the memories of a time when you were younger, with endless potential. Above my bed still hung my soccer jersey from my senior year of high school. In one of the nightstand drawers, there were still letters from high school friends, papers I’d written, pictures from the summer before college — the last summer of complete freedom that I would ever know. In this way, I was given a type of distance from the life I felt I couldn’t succeed in. I wasn’t a child again, but I was, certainly, re-living another life through new eyes.

A total stereotype of early-20s apathy, I spent my time working a shit job at a dollar store in the neighborhood where I grew up, mostly because I could walk there and walk home with something in my headphones. When I got to the store, I would slump over the cash register, playing a CD of often inappropriate shopping music over the store’s speakers.

In the middle of this, My Chemical Romance’s The Black Parade arrived. A dark, deliciously overblown, theatrical concept album about that which carries us into an imaginary afterlife. It was a massive album, in both sound and scope. I first loved it because of how the actual sounds of it filled headphones or a room. On a day off from the dollar store, with my father away at work, I would throw the album on and turn up the surround-sound stereo, letting the chunky guitars chew at the framed and rattling photos on the wall. I insisted on falling for the music first, having never had an immense interest in concept albums, particularly ones that came out of the emo/punk scenes, so many of which were filled with sprawl for the sake of sprawl, sacrificing narrative for hard-to-track, excessively emotional lyrics. I thought even My Chemical Romance’s previous album, Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge, failed in its pursuit of concept while succeeding in the pursuit of music. Still, I believed in The Black Parade more than any other My Chemical Romance project before it because I believed in their willingness to be entirely certain of their mission at a time when I was without a mission, and also without certainty. They were, always, a bit outside of the scene. They played at the typical emo festivals and were covered by all the typical alternative music magazines, but they were a little surer of the emotional dark spaces they were navigating than their peers. Even at their most performative — which The Black Parade definitely is — there was something about My Chemical Romance’s vision that felt comfortable, touchable, genuine. It was easy to be confident on The Black Parade, an album that unpacks a complete certainty: that we are all going to die, and none of us know what comes next.

ACT II

I am not afraid to keep on living

I am not afraid to walk this world alone

Today, in 2016, death is a low-hovering cloud that is always present. We know the dead and how they have died. We can sometimes watch the dead be killed. We can sometimes watch the best moments of their lives be replayed after they are gone — a reminder that they were once something other than buried. In this way, we can come to know the dead more efficiently than we know some of the living who occupy the same spaces we do. Yet even with all of this, exploring the interior of death’s endless rooms is a far less virtuous endeavor than continually and somberly reacting to the endless river of graves.

The Black Parade, in concept, is about a single character, “The Patient,” who is suffering from cancer and facing down an inevitable death. More than simply honing in on the patient’s decay, My Chemical Romance frontman Gerard Way presents an operatic theme that revolves around the patient’s slow passing into a life after death, carried by a parade. The idea is death coming to you in the form of your first and most fond memory: a flower opening slow in your front yard, a bright and colorful sunrise, or a slow-marching parade of musicians and merry-makers walking with you to the gates in their darkest regalia.

In retrospect, The Black Parade isn’t as large of a leap for My Chemical Romance as it was billed as in 2006. It feels instead like a natural progression, the album where the band finally figured out their formula and how to cash in on it. It still has all of the musical, lyrical, and visual dramatic and aesthetic of a My Chemical Romance album; it’s just turned up to a higher level. Where the sharpest growth exists is in their idea of “concept.” They are a band of storytellers who simply needed to dial in on a single small story and pull the narrative along, instead of falling into the trap of trying to connect too many threads at once. The Black Parade doesn’t insist on resolution because it doesn’t deal in the resolute. Death, yes, is inevitable. But that which we see before it arrives, the things that happen after the lights go out, is pure imagination. The work of The Black Parade was simply to bring it to life.

And musically, visually, the life is a glorious one: the tinkling piano on “Welcome to the Black Parade” giving way to a shower of guitars ripped straight from late-’70s arena rock, Gerard Way half-growling, half-singing the same tense lyrics that dance along the lines of loneliness and desire. The video for the album’s proper final song, “Famous Last Words,” is perhaps the album’s finest moment, where the band, so committed to putting a bow on the album’s immense mission, thrash and wail in front of a wall of fire. The parade float is burning at their backs, their marching outfits are worn out and covered in dirt, and the parade itself is gone. It is only them, alone, fighting to survive. They have, on their journey, become The Patient and his fight. It is a dark video, one that speaks to sacrifice, both metaphorically and very literally: Drummer Bob Bryar sustained third-degree burns on the back of his legs while filming, Gerard Way tore muscles in his foot and leg, and lead guitarist Ray Toro fractured his fingers, which were already blistered from the heat. Watching the video is as fascinating as it is agonizing. Toward the end there’s a shot of rhythm guitarist Frank Iero on his knees. He lets his guitar slip out of his hands and breathes heavily while the fire rages at his back. His exhaustion, in that moment, feels real. It is brief, but it pushes through the screen and sinks into you. Even in the face of a spectacular album, this single video served as proof of a single band’s commitment to something daring, as well as the cost of that commitment. To push so deep into the imagination of death that it becomes you.

ACT III

Well, I think I'm gonna burn in Hell,

Everybody burn the house right down.

What I don’t know, friends, is whether or not I believe in a life after this one that I’ve rattled around in for this brief and sometimes beautiful bunch of years. I know that I have thought about dying, like many of you likely have. When I have buried people I love and wondered if we would ever again sit across from each other at a table and laugh at an old joke. The uncertainty of an afterlife has also kept some of us here: At my youngest, most reckless and uncertain, I had moments where I thought life was done with me and I thought myself done with it. And, perhaps like some of you, I have remained here because of my comfort with the darkness I know and my fear of the darkness I do not.

The afterlife is, most times, talked about as an achievement as opposed to a full-bodied existence. A place some of us “get” to enjoy, while the rest of us languish in a more terrifying place. I imagine the afterlife, and what carries you there, like Gerard Way does. I imagine my fondest memories gathering me in their palms and taking me to a place where I can join a discussion already in progress with all my pals in a room with an endless jukebox.

ACT IV

To un-explain the unforgivable,

Drain all the blood and give the kids a show

Around my kitchen table this past Sunday night, in the company of some of my poet friends, we were having a stereotypical conversation, the type that people most likely imagine poets having, about what people are “owed” from our work. Who is owed our grief, and discussions of our grief, or how to carry everyone’s grief within our own. If I tell a sad story, and then you, reader, tell me a sad story, and then your friend tells me a sad story, how do I take that with me and try to make something better out of it?

As the conversation wore on, my friend Nora turned to the table and said, “Why do we think of grief as a collection of individual experiences anyway? Why don’t we just instead talk about grief as a thing that we’re all carrying and all trying to come to terms with?”

And I know, I know that may seem like what all of our missions may be, but I tell stories of the sadness of an individual death first and the complete sadness of loss second. I have, in a lot of ways, convinced myself that more people will feel whatever I am asking them to feel if there is a name or a history to go with the body. If I can unfold a row of photos and stories and name a life worthwhile to a stranger, they might connect better with what I’m saying. And that might be true in some cases, but what I’m learning more and more as I go on is that my grief isn’t special beyond the fact that it’s mine, that I know the inner workings of it more than I know yours. I imagine The Black Parade as a conversation about grief ahead of its time, dealing in the same tensions that I find myself wrestling with at a table with poets 10 years after its release. The Patient is only The Patient. We arrive at his story as it ends and get only the details we need. He is forever nameless, without major signifiers. It is telling that by the end, by the visuals for “Famous Last Words,” The Patient is projected onto the band themselves. The message of a universal grief, yours and mine, that we can acknowledge together and briefly make lighter for each other, is in that moment. That which does not kill you may certainly kill someone else. That which does not kill you may form a fresh layer of sadness on the shoulders of someone you do not know, but who still may need to press their ear to the same thing that told you everything was going to be all right when you didn’t feel like everything was going to be all right. The Black Parade doesn’t treat the recesses of grief as a members-only party, where we show up to the door with pictures of all our dead friends and watch the gates open. It assumes, instead, that we’ve all seen the interior, and offers a small fantasy where the other side is promising.

ACT V

Mama, we’re all gonna die.

Mama, we’re all gonna die.

The My Chemical Romance song that I return to the most is “Fake Your Death.” It’s not on The Black Parade; it’s a random track that showed up as the opener on their 2014 greatest hits album May Death Never Stop You. It’s a good song, sitting firmly in the Danger Days canon of My Chemical Romance history. Gone are the echoing and heavy guitars and the stadium howl of Gerard Way — it’s a simple tune, only piano and percussion, taking on a bit of a pep-rally feel. I not only like it as a song but as a companion piece to The Black Parade. It’s a good signifier of the band’s end, equal parts heroic and reflective. On it, they sound both proud and defeated. I think, often, about what that album must’ve taken out of them. Gerard Way, in recent years, has said that he imagined the band being done after they finished The Black Parade tour. In between The Black Parade and the aforementioned Danger Days: The True Lives of the Fabulous Killjoys, released in 2010, an entire album was recorded and scrapped. Danger Days is a fine album — it’s a bit scattered thematically, not as focused or inspired, but it’s a good collection of songs that I have grown to enjoy as much as any other My Chemical Romance album.

The Black Parade celebrates its 10th anniversary with a boxset in two weeks. Demos, remastered songs, the works. The album still lives, but the conclusion of it remains: The Patient is gone by the end of The Black Parade. We know this, and still, I think of The Patient as I would a full, breathing character in a film. He drives the way I think about the band that was My Chemical Romance, even before they inserted him into their music. I wonder how long he was living in Gerard Way’s head before he lived through the brief and glorious burst of an album that was The Black Parade. And I wonder, always, how art can immortalize even the imaginary lives.

Even though “Fake Your Death” signaled the end of the band, I think its message for an audience is one about what you can come back from. This, relying on the other definition of death, the one that does not take you from here but makes you feel like there is something weighing on you that you can’t lift off. The song is, through that lens, about shedding old skin and stepping into a newer, lighter version of oneself. I listen to it now, on repeat, and I think of myself at 22, saddled with doubt in a room filled with my childhood memories, not knowing what to make of a life that hadn’t gone as I’d planned. And I get it. Even if Gerard and the boys don’t ever come back again, I get it all. I’m better for it. And I’m still here.

0 notes

Text

From The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business is Selling Less of More by Chris Anderson (2006)

Reprise found a perfect example of just that kind of fan base with a

punk-pop fivesome from New Jersey called My Chemical Romance.

Although the band’s album Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge came out around the same time as McKee’s, it was their second album. The

first, on an independent label, had sold 10,000 copies, which suggested a small but strong core following. So five months before the second album’s launch in May 2004, Reprise started giving tracks to Web sites focused on that core, such as Shoutweb.com and

AbsolutePunk.net, to get the buzz going among the faithful in hopes

that it would spread.

The label also pushed the band on PureVolume.com and MySpace.com, two relatively new (at the time) music-heavy socialnetworking sites with an exploding user base. It gave exclusive live tracks to PureVolume for promotions and premiered an Internet-only video for the band’s first single, “I’m Not Okay (I Promise).”

Once the tracks were out there, Reprise could watch how they did.

Using BigChampagne file-trading data, the label could see growing interest in “Not Okay,” but also heavy trading and searching on the track “Helena.” On the basis of that, it made “Helena” the next single, and, helped by requests from the band’s core fans, the song got airplay. By the end of the summer, “Helena” had become the band’s biggest radio single by far.

As the band went on tour in September, Reprise extended the promotions to Yahoo! Music and AOL, including audio, video, and a heavily promoted live performance from Yahoo!’s studios. Meanwhile, fans flocked to the band’s Web site and MySpace page. My Chemical Romance now has Warner’s largest email list.

The album went on to sell 1.4 million units, making it one of the

biggest hits of the year. Most of that came after radio and MTV embraced the band and brought it to a larger audience, but it all started online, where the band’s core audience had cemented its credibility.

What was the difference between My Chemical Romance and

Bonnie McKee? Talent differences aside, My Chemical Romance had the advantage of an existing base of fans, both of its first album and its live shows. There were thousands of people already hungry for more from the band, and when the label gave them what they wanted, in the form of early online content, they returned the favor with strong word of mouth, including radio requests. And that, in turn, got the band the airplay that took it to the next level of popularity, acquiring a new, larger, set of fans.

McKee, by contrast, was a relatively unknown artist, who had

rarely played live. Although people liked what they heard on Yahoo!, it wasn’t enough to trigger real fan behavior. They didn’t buy the album, and they didn’t clamor for more. On MySpace today, My Chemical

Romance has more than 1 million “friends”; McKee has 12,000. Word

of mouth makes all the difference.

10 notes

·

View notes

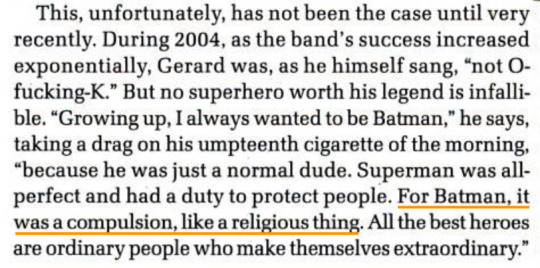

Photo

even when it’s about batman it’s about joan of arc

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

i’ve been thinking a lot about gerard’s character they developed in the last leg of this tour and the way i believe it really solidified what we might have coming for us in the future.

it’s really sweet, if you look in the comments of some of the videos from brisbane and osaka, you can see people who’ve obviously been my chem fans for at least 15 years saying things like ‘i’ve watched every video from this tour and this is the first show where i really saw the spark come back’ and ‘that’s the gerard way i remember’ and other cheesy shit like that. and the thing is they’re totally right!

this whole tour developed more fluidly in intensity and meaning than in any of their previous gigs. mcr has always been a band to change with their time and creative drive, but this was a different type of transition to me. you could see as characters started to be built, from gerard DIY’ing his own costumes in europe to increasingly meaningful outfits with whole backstories in the USA all the way to one consistent character with a uniquely terrifying stage presence in the last leg.

that last character, at least to me, is totally gripping. she’s unexplained, she’s scary as hell, she’s near-undead, she has this commanding presence gerard hasn’t really done since early-mid black parade. in every single performance they’re so in-character and it’s such a BLAST

importantly, this character also showed up in the shortest, least-publicized part of the tour. imo she wasn’t meant for cameras, really.

to me it’s so clear that she’s a result of gerard earnestly solidifying where they might want their next artistic endeavors to go - that kind of serious direction, maybe even that character specifically.

he’s talked about how he always has stage characters that reflect his music and, broadly, things they’re working through in their life. the revenge stage character was a mix of both demo lovers which can have a ton of different interpretations, the patient was a joan-esque personification of grief and existentialism, party poison was a pop-art way of dealing with your own artistic/literal death. it makes me wonder why this character, the only truly consistent character this whole tour, came about, and if it’s related to gerard’s nightly diatribes on war and later-tour statements on (presumably) queer/trans rights.

it also makes me think that we have a lot coming in the future. a character that solid and a direction so suddenly bottlenecked into such a specific concept, such a mychemicalromance concept, especially out of a tour that was originally supposed to be a casual celebration of music, i think points towards something new.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

My foundations of decay annotations. In some of the notes I might say “the man” or “Gerard”. In reality a lot of these lyrics were probably a group effort from all the members :) also just my interpretations not scripture!

221 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Chemical Romance Dissolves Its Bond

ANDY GREENWALD | March 25, 2013 | grantland.com

The first time I met Gerard Way was February 2003 in Chicago. I was fleeing a blizzard on the East Coast and profiling the Used, an up-and-coming screamo band from Utah whose singer, the maniacally disheveled Bert McCracken, was in the news for dating, then dumping, Kelly Osbourne. Gerard’s band, My Chemical Romance, was opening for the Used at the time and he and McCracken were well on their way to forming a chemical-based bromance of their own. One night the two kept me in the room with them until dawn as they drained the minibar, sent the concierge out for smokes, and made increasingly frequent trips to the bathroom. (Gerard later told me that bender was the inspiration for a song called “You Know What They Do to Guys Like Us in Prison,” which featured the lyric “do you have the keys to the hotel? / ’cause I’m gonna string this motherfucker on fire.”) Onstage, assuming they were able to stumble up to it, the pair were complementary as well: two stringy suburban weirdos peddling punk uplift bruised and blackened with mascara and talk of murder.

There were differences, though, too, and these were key to everything that followed. Flicking boogers and cackling like a banshee, Bert wore fame like a leather jacket. He flashed and strutted, naturally assuming the role of dangerous front man whether he had a mic in his hand or not. Gerard — a scared and sensitive wannabe comic-book artist who formed a band out of either depression or desperation in the wake of 9/11 — wore a leather jacket like a suit of armor. When I interviewed him in Brooklyn, a year later, for the release of what would turn out to be My Chem’s breakthrough album, Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge, he refused to remove the stinking, sweat-stained garment despite the rising temperatures and the concerned looks of the yuppie clientele surrounding us at the coffee shop. It was what he needed to become a rock star, he said, or at least to not feel like a fraud.

It was his costume, the first of many to follow, and it instantly set him apart from the schlocky flock of adenoidal whiners that flooded the charts — and kept me eating! — during the emo boomlet of the last decade. Where other bands bleated about their breakups, My Chemical Romance snarled. Gerard, his kid brother Mikey, along with guitarists Ray Toro and Frank Iero, refused to wallow in self-serving grief. How could they when they so clearly weren’t “o-fucking-kay”? They were misfits and dungeon masters, drama nerds and otakus. Most of all, they were performers, using light humor and heavy makeup to celebrate the majesty and ridiculousness of first feelings: love, death, the pain of piercings both literal and otherwise. They ganked attitude and artifice from Bowie and Queen, stole moves from the ’70s campfest Phantom of the Paradise, and dueted with Liza Minnelli. In the video for “Helena,” a Catholic funeral explodes into a goth Busby Berkeley review. It wasn’t a sing-along, it was a rallying cry. Plenty of bands had angst. My Chemical Romance had style.

Rock critics have long fallen back on superhero mythology to describe musicians; it’s a handy way to add grandeur to what tend to be fairly rote backstories, bending boring arcs of rehab and redemption into the Hero’s Journey, all in a quest to avoid quoting the drummer. But My Chemical Romance was the first group I covered that actually used that mythology for themselves. Gerard called his band “an idea,” labeled his fans an army. From album to album and show to show, MCR reinvented themselves across a multiverse of possibilities: They were soul-reaving vampires exacting revenge, the ghosts of a marching band returned to serenade you home, a gang of outlaw futurists using lasers and jazz hands to free the world from monochrome mediocrity. They had artistic ambition in a rock era that actively discouraged it, and they pursued it passionately without even a dash of irony. In that, they were just part of a great tradition of hardworking, self-made dreamers to emerge from the swamps of New Jersey, a wallet chain that stretches from Springsteen to Snooki. “We’re all about being the escape artists, throwing the fuckin’ straitjackets on, covering ourselves with chains and having somebody push us in the river. And then trying to get out of that,” a bleached-blond, clean-and-sober Gerard told me in 2006. We were sitting on a balcony overlooking Milan at the time, because the music industry was absurd back then and would fly you to places like that to interview people like him. “I think the world is ready for spectacle, for something big,” he said excitedly. “They’re ready for heroes, for something to believe in.”

Parts of the world were, anyway. The ravenous MCRmy spanned the globe, from Mexico City to Manila, a polyglot, multilingual militia that took solace in the band’s underdog triumphalism — and sometimes even took to the streets. I’ve never witnessed such intense fandom, before or since. Still, the resolutely black-clad supporters seemed skeptical of their beloved band’s slow progression into the light. 2010’s Danger Days was, to my ears, a glorious glitter-bomb of panic and disco, effortlessly mixing Detroit boogie with Weimar cabaret, summertime pop radio with Euroclub stomp. Gerard’s hair was a vibrant red — more Kool-Aid Man than arterial blood — and his new stage style was loose and breezy. The album eked out a platinum plaque, but its reception felt culturally inert, as if My Chemical Romance’s creative maturation had somehow skipped the groove of fight-or-flight survivalism that once grounded their fantastic excess. Gerard truly believed he was saving rock and roll by running around in the desert with a ray gun, but it was doubtful he could save his band from suffocation at the hands of a dying industry or the smothering embrace of fan expectation. He still believed in rock stars, but he also very much believed in Batman.

The last time I saw Gerard Way was in October at a comic-book convention in Las Vegas. His hair was its natural black but his mood was bright. He was in his element, there to celebrate his idol turned pal Scottish surrealist Grant Morrison. The event felt like a coming-out party for everything My Chemical Romance had screamed and bled about; it was a peaceful gathering of light-sensitive weirdos held in the shadows of the most garish place on earth. He and Mikey both talked animatedly about the sessions for their upcoming fifth album, which were well under way. But it did strike me that the larger battle had already finished. Gerard has a successful second career writing comics and movies and a pleasant life in Los Angeles with his wife and daughter. He’s free to doodle and daydream without worrying about the vagaries of record-label drama, the vast machinery required for global touring, or the fragile egos of increasingly far-flung co-conspirators. It turns out Gerard Way was the hero in his own story after all, and, unlike the “Patient” he played in the Black Parade, he wrote himself a happy ending.

He couldn’t quite manage the same for his band. My Chemical Romance announced their breakup on Friday night. They didn’t die in a gunfight or explode with the intensity of a million suns. Instead they just posted a note on their blog and called it a day. There’s talk of intramural squabbling and adultery scandals — feel free to Google; I’ve no interest in spreading the muck — but to me it feels more natural than reactive. What villains were left to face? What demons left to conquer? My Chemical Romance always aimed for the top, but the top no longer exists; all that remains is a vast, niche-y middle. Rock bands don’t want to be big anymore. Hell, if they’re smart they don’t want to be rock bands at all. In that, My Chemical Romance really were “The Kids From Yesterday,” the more or less last song on their more or less best record. “We’ll find you when the sun goes black,” Gerard sang, but I hope it doesn’t take that long for him to reboot. The thing is, I think the music industry needs a skyscraping fabulist like Gerard Way a lot more than he needs the music industry. For now, all I can do is take comfort in the fact that even Batman died once.

1 note

·

View note

Text

My Chemical Romance's 'Kids From Yesterday': Death Of Danger

Fan-made video for 'The Kids From Yesterday' looks back at the band's rise to fame.

James Montgomery (@positivnegativ) | Jan 17 2012 | mtv.com

Really, My Chemical Romance's Danger Days: The True Lives of the Fabulous Killjoys deserved better. A big, bold re-invention of their sound and swagger, it was, by the band's own admission, a "missile" aimed at destroying the staid state of rock and roll, and perhaps because of that fact, it failed to catch on here in the states.

You could practically track its decline based on the videos MCR released off the album, starting with the big-budget "Na Na Na" and the equally flashy follow-up, "Sing," in which they offed the titular Killjoys (who seemingly will never be heard of again). Their next single, "Planetary (Go!)" came coupled with a live video, and, to the best of my knowledge, a clip for "Bulletproof Heart" never materialized at all.

My Chem actually seemed to address the matter in an interview with MTV News last year, in which frontman Gerard Way lamented that the band had "gone through so many things" over the course of the Danger Days cycle, and hinted that, if there were to be any more videos off the album, they'd have to be financed by MCR themselves.

So it's somewhat fitting that, on Monday, they unveiled the final clip from Danger Days: a fan-made video for "The Kids From Yesterday" that documents the band's decade-long climb from Neo-Goth New Jersey rockers to interplanetary conceptual quartet. Like the song itself, the clip is a bittersweet thing, recounting MCR's many triumphs (a pastiche of memorable live moments, it culminates with their headlining slots at Reading and Leeds this past summer), while leaving those who love to read between the lines to wonder if perhaps the band's latest era also represents the end ... not necessarily of My Chem themselves, but of a moment in rock that now seems to have all but disappeared. Truly, MCR were the last bastions of the heady heyday of mid-aughts MySpace punk, and now, well, who knows what's next?

Of course, much of the message behind Danger Days seems to be one of self-empowerment, of inspiring fans to take matters into their own hands and shaking up the status quo. That's yet another reason why "Kids" is such a fitting sendoff; it was made in collaboration with a fan named Emily Eisemann, who had culled through live footage and initially created a clip of her own. There's a reason why the video ends with the phrase "Art is the Weapon," after all: it's been the band's clarion call this entire time.

It's also something Way touched on during Danger Days' release, when he told MTV News that the album was not a conceptual piece, but rather "a complete allegory" for smashing the system and placing the power directly in the hands of their fans. And "Kids" is proof that MCR's message was heard loud and clear, perhaps not by a majority of the record-buying public, but definitely — and most appropriately — by their fans. Sometimes, sales aren't the only measure of a band's success, and Danger Days is a testament to that fact. "Kids" may bring one chapter of their career to a close, but wherever My Chemical Romance go next, you know they'll do so boldly; that's what makes great bands truly great after all: the willingness to push the boundaries, to purvey inspiration, to shake things up ... sometimes even at their own expense.

0 notes

Text

Shyness Is Nice, but Not When Reaching for Grandeur

Kelefa Sanneh | Oct. 26, 2006 | nytmes.com

Who says it has been a dull year for rock ’n’ roll? Why, only a few months ago, Angels and Airwaves, the new band led by the former Blink-182 member Tom DeLonge, released a CD that generated “album of this decade” hype. More recently, the Killers created “one of the best albums in the past 20 years.” And even before the new album from My Chemical Romance arrived in shops, there was a sense that “something big” was afoot. All those quotes come from the lead singers, not critics. But that’s a start. And at least one of those lead singers happens to be right. It was Gerard Way, from My Chemical Romance, who told MTV how excited he was about his band’s new album, “The Black Parade” (Reprise/Warner). He said there was “a sense of something big is going to happen and it’s potentially terrifying.” And on Tuesday he was proved right twice. In the morning, that CD hit shops; it’s brilliant. And that night, his band played a thrilling set at Webster Hall. It certainly felt like the start of something big.

It can’t possibly be a coincidence. Now that rock ’n’ roll seems more than ever like a niche genre, a handful of bands are reaching for grandeur. In an age of weightless mp3’s, they want to make weighty albums (whatever that means). Conscious of a rock ’n’ roll power vacuum, these bands are trying to fill it.

Mr. DeLonge’s campaign is perhaps the most surprising. His old band, Blink-182, was known for fizzy pop-punk songs, not grand statements. After the trio split up, he formed Angels and Airwaves, telling MTV, “I want to come out with an album that people will refer to 20 years from now as the album of this decade.” Later, he said his band, which owes a notable debt to U2, was “on the edge of doing something extremely powerful and massive in music.”

Brandon Flowers, from the Killers, has been just as immodest. He has belittled the competition, from Fall Out Boy to Green Day. And he told the British weekly NME that the new Killers album, “Sam’s Town” (Island Def Jam), is “one of the best albums in the past 20 years.” Even better: Mr. DeLonge took offense, hinting that Mr. Flowers had stolen his “20 years” rhetoric.

All three of these bands come from genres known more for youthful energy than for gravitas. Mr. DeLonge’s grand proclamations might be a delayed reaction to the years he spent in Blink-182, a pop-punk band that once released an album (a really good one, too) called, “Enema of the State.” Similarly, the Killers’ debut, “Hot Fuss,” was full of propulsive, vaguely new-wavey singles; now Mr. Flowers is telling interviewers how much he loves Bruce Springsteen. And Mr. Way has talked about wanting to escape the emo scene that nurtured his band; songs on “The Black Parade” nod at influences ranging from Queen to cabaret (thanks to a brief but much-discussed cameo from Liza Minnelli).

This is partly a story about money, too. At a time when lots of major-

label bands are learning how to be content with low six-figure sales, these bands want to keep selling millions of CD’s and filling big rooms. If anything, the industry slump has made bands less shameless about aiming for mainstream success; it’s hard to rail against arena rock when there are hardly any new arena-size bands to rail against. This obsession with bigness is, in part, a small rebellion against a world in which bands shrink themselves to fit MySpace and YouTube. These bands want to make albums that are actually worth $18.98. (A special edition of “The Black Parade,” in an oversized box, has a list price of $44.98.)

Finally, this is partly a story about America. In Britain, where rock ’n’ roll never shrank, strutting major-label bands are a dime a dozen. Not coincidentally, Britain’s biggest and most important band is Arctic Monkeys, a group that followed its small-sounding debut album, “Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not” (Domino), with a couple of mini-CD’s (the second, a charming 10-minute disc called “Leave Before the Lights Come On,” was released on Tuesday) and a distinct lack of pomp or theater. The lead Monkey, Alex Turner, is a shrugger, not a boaster.

But back to America, and to reality. It turned out that the Angels and Airwaves album, “We Don’t Need to Whisper” (Suretone/Geffen), was charming but lightweight; it has sold fewer than half a million copies, according to Nielsen SoundScan. The Killers album sold an impressive 315,000 copies in its first week, but it has a long way to go before it matches “Hot Fuss,” which sold over three million copies. The My Chemical Romance album certainly deserves to be a smash, and first-week sales are sure to be huge. But even that doesn’t make it a sure thing.