Photo

Image: The Guide Istanbul

Here’s the original text from my balik ekmek article for The Guide Istanbul:

Balık ekmek is a ubiquitous “must-eat” food in any tourist-oriented feature on Istanbul. Even for the casual visitor glancing at a guidebook, the “fish sandwich” is nearly impossible to overlook. Simply constructed of grilled whitefish with raw onions and lettuce sandwiched between a half-loaf of standard white bread, it’s typically identified as unmissable not just for its supposedly superior flavor, but as a cultural experience specific to the city of Istanbul. Visitors are called to take a leisurely stroll along the Bosphorous shorefront, stopping on the way for a taste of “authentic” Turkish street food culture in the form of balık ekmek.

So-called “heritage tourism” is a growing and generally positive trend in the contemporary tourist industry. Many travelers grown weary of generic, sun-saturated beach vacations instead seek to authentically connect with the unique local culture and character of a place. This can be seen in the proliferation of UNESCO World Heritage Sites, the quest for “off the beaten track” destinations, the growth of eco-tourism, and the popularity of sampling local cuisines. Food is one of the most immediate and enjoyable ways for visitors to consume – to literally taste – the heritage of a place, and Istanbul prides itself on both its seafood and street food cultures as shining examples of its historical culinary heritage.

Among Istanbul’s heritage foods, balık ekmek is arguably the most celebrated and iconic, and it does indeed have historic roots in the city. Freshly-grilled fish served on thick hunks of bread has been sold on the Bosphorous and Haliç waterfronts since the mid-19th century. When catch sizes were particularly abundant, fishermen set up makeshift grills on the decks of their boats to sell directly to hungry Istanbullus. It was not a primary form of income generation, but a way for fishermen to earn extra money from generous catches.

This practice could be seen in Istanbul into the 1990s in Eminönü, Karaköy, and Bosphorus neighborhoods (themselves former fishing villages). In fact, the now-famous Adem Baba fish restaurant in Arnavutköy got its start as a modestly-sized boat docked in Bebek, serving simply-prepared fish at a single 10-seater table on the boat deck, before expanding its business to a brick and mortar restaurant.

Since the late 1950s, Istanbul’s fish stocks and fishing industry have been impacted by a host of changes, including environmental damage resulting from urbanization, industrialization, and coastal development, the growth of large-scale industrial fisheries contributing to overfishing, and an urban population explosion leading to increased demand for food. These factors have had a striking effect on fish stocks and the overall health of the city’s waterways. One result is that small-scale fishermen have increasing difficulty in making a living from fishing due to plummeting fish stocks – no longer are abundant catches grilled and sold shoreside as fishermen struggle to make ends meet.

On top of considerable environmental challenges, municipal regulations have also increased in recent years. In 2004 the Istanbul Preservation Board (Korumu Kurulu) banned balık ekmek boats from operating in Eminönü. The government’s stated reasoning for the ban was to prevent visual pollution, and to protect the historical and natural texture of the Bosphorus – a curious justification given the municipality’s history of landfilling large swathes of urban coastline. In 2007 the Municipality (Istanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi) granted limited “tekne yeri” (boat location) tenders specifically for balık ekmek boats at an annual rent rate of 52,000-55,000 liras. In order to participate in the auction, bidders were required to be members of the Istanbul Balık Satıcıları Esnaf Odası (Istanbul Bureau of Fish Sellers), and to have at least five years experience selling balık ekmek. That year only seven people were part of the Bureau and eligible to bid, just four of them placed bids for boat rentals, and three rentals were granted by the municipality. These are the three elaborately-decorated “Ottoman-style” boats which now dock at the Eminönü waterfront.

Outside of Eminönü, balık ekmek vendors (of varying degrees of legality) can today be found operating in Kumkapı, Sirkeci, and Kabataş. It is hardly a secret these days that in all areas of the city, the slabs of whitefish on vendors’ grills are not pulled fresh from the Bosphorus or even from Aegean fish farms, but imported on ice from Scandinavia and sold in bulk at Istanbul’s wholesale fish market. As fish stocks have plummeted, prices for local fish have gone up, while at the same time the increased popularity of balık ekmek with tourists puts pressure on vendors to keep up with demand while maintaining a low bottom line. While it is marketed as an authentic expression of Istanbul’s culinary heritage, the fish used in today’s balık ekmek is not local, and is often neither flavorful nor particularly fresh. There is an undeniable contradiction as this dish popularized to use excess fish in a time of abundance has now become so scarce as to require the use of foreign imports. It raises the question of whether balık ekmek can still be considered an authentic Istanbul street food.

The shift to a highly regulated balık ekmek industry has clear benefits, foremost being improved health and safety regulations for the benefit of consumers. At the time of the boats’ initial removal in 2004, many speculated that the ban was an effort to accommodate EU sanitation regulations. Others appreciated that the removal of private boats which had previously been operating without licenses (though most did have docking permits) both cleared up public shorefront access and generated income for the city in the form of permit fees.

For some, the elimination of independent balık ekmek boats and the concentration of select numbers of licensed vendors in the highly touristic area of Eminönü demonstrates a monopolization and capitalization of traditional street food traditions, and is damaging to the cultural heritage of the waterfront – in exact contradiction to the Municipality’s goal of protecting the city’s historical integrity. Not only that, but it deprives Istanbul residents, especially lower income ones, of an inexpensive meal option if they are not living or working in the vicinity of Galata. What was one a low-cost meal for local people which could be purchased in many waterfront areas has become a tourist attraction.

Looking at today’s balık ekmek from a cultural heritage perspective, we can also see a manipulation of history. While in one sense it represents a continuity with earlier periods, there is also a co-opting of the modest, workaday roots of the balık ekmek trade, as a simple food sold by fishermen directly to local working people is replaced with a nostalgic, fantasy version of the past in the form of imaginatively-decorated “Ottoman-style” boats in Eminönü presenting themselves as historic. There is evidence that the kitchens in Topkapı may indeed have purchased fish for the palace table directly from fishermen, but the sultan certainly never set up business plying sandwiches to civilians from gilded boats.

Some modern chefs have underlined balık ekmek’s role in Istanbul’s cultural heritage by reinterpreting it for contemporary diners. Celebrity chef Maksut Aşkar (now of Neolokal) featured a gourmet version of balık ekmek – grilled seabass with arugula pesto and sweet red onion chutney on whole-wheat sourdough – on the menu during his tenure at SekizIstanbul. At chef Mehmet Gürs’s Mikla, where the seven-course tasting menu is priced at 265 TL as of Winter 2015, “balık ekmek” appears in the form of a single piece of hamsi embedded in thinly-sliced olive oil bread and served inside a warm Black Sea stone. The popularity of balık ekmek is evidence that Istanbul’s local seafood and culinary history has the potential to spark tourist interest, but the way it currently operates is in some ways problematic. The challenge will be to develop a form of heritage tourism which benefits local small-scale fisheries while also encouraging the revitalization of Istanbul’s seafood culture. While issues of “authenticity” are worth questioning, it is undeniable that balık ekmek is a tangible part of the city’s history and heritage, one whose sustainability is worth fighting for.

Karaköy

Until last year, a handful of popular balık ekmek stands could be found west of the Galata Bridge near the Karaköy fish market. In 2014 I spoke with several of these vendors, who explained that the six stands were owned and operated by two individuals, who worked their own carts alongside hired workers. Both owners and workers had come to Istanbul from eastern Turkey, and in some cases worked seasonally, returning to their hometowns in Diyarbakır and Erzurum after earning money in Istanbul. When asked about the demographics of people buying sandwiches, they explained that “all kinds” of people come, tourists and Turks alike, including Istanbullus on their lunch breaks. In the early morning of July 22, 2015, an Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality demolition team, accompanied by riot police with water canons, bulldozed all of the fish restaurants, tea gardens, and balık ekmek stands in Karaköy, leaving mounds of rubble in their wake. According to the Municipality, all were illegal constructions erected without permits, and vendors had been ordered to evacuate less than 48 hours before demolition began. Some defended the actions of the Municipality, viewing it as an effort to “clean up” illegal businesses, while others suggested that it was politically motivated. Some suspect that this will pave the way for the proposed Galata Port project, in keep with the Municipality’s claims that the Karaköy shorefront will be converted to a public park. While the Karaköy fish market has subsequently been renovated, the area left by the balık ekmek vendors remains vacant.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Here's a little article I wrote a while back about balik ekmek as a component of Istanbul's cultural heritage. It's been heavily edited (cutting some of the more critical - "too negative" - components of the discussion), but it's good to have the chance to get the conversation started.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Eaters Magazine: Want. Now, how?

1 note

·

View note

Link

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Love books like The Oyster War about fisheries, the people who work at them, and the seafood that we eat?

We’ve got a pile of recommended reads.

45 notes

·

View notes

Link

A must-read from NPR about bycatch in the fishing industry. "Unless you study the fishing industry for a living, it's tough for a consumer to avoid these fisheries when shopping for seafood. Nonetheless, groups like Oceana, the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Monterey Bay Aquarium have been trying to educate consumers about the bycatch issue through seafood buying guides and other campaigns. "As a concept, people get what bycatch is and they don't like it," says Sheila Bowman, with the Monterey Bay Aquarium's Seafood Watch. "But the data is often too hard for shoppers to put into context and act on.""

1 note

·

View note

Photo

From my book blog, fish crossover :)

Photo: Cara Nicoletti for Yummy Books

One of my absolute favorite blogs is Yummy Books, in which New York-based writer and butcher Cara Nicoletti combines two of my great loves - food and literature - as she prepares meals based on books. She’s a shimmeringly excellent writer and photographer, and I can’t wait to read her new book, Voracious, which follows the same concept as the blog.

Her post, “Eating Fish Alone,” based on a line from a Lydia Davis essay by the same name about rituals surrounding eating and the act of dining solo, is a thing of beauty. I also love Nicoletti’s homage to Irish poet Seamus Heaney’s “Oysters.” Seafood is kind of a big part of my life, so I may be biased, but see for yourself.

#voracious#viafish#readingcities#lydia davis#cara nicoletti#yummy books#seamus heaney#eating fish alone#fish

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Interesting article from Lucky Peach about the Japanese fish-killing method of ike jime, which is thought to both be more humane and to result in better tasting fish.

Photo: Gabriele Stabile for Lucky Peach

1 note

·

View note

Link

a very recent article from the new yorker about the potential for raising the culinary status and popularity of small forager fish (herring, sardines, mackerel) as a sustainable alternative to the consumption of stressed populations of larger predatory fish (tuna, swordfish, etc.).

#butterfish#ecology#ferran adrià#fish#grant achatz#herring#mackerel#sardines#anchovy#fishing#sustainable seafood#paul greenberg#united states

1 note

·

View note

Photo

I am listening to Istanbul (Orhan Veli Kanık)

I am listening to Istanbul, intent, my eyes closed:

At first there is a gentle breeze

And the leaves on the trees

Softly sway;

Out there, far away,

The bells of water-carriers unceasingly ring;

I am listening to Istanbul, intent, my eyes closed.

I am listening to Istanbul, intent, my eyes closed;

Then suddenly birds fly by,

Flocks of birds, high up, with a hue and cry,

While the nets are drawn in the fishing grounds

And a woman's feet begin to dabble in the water.

I am listening to Istanbul, intent, my eyes closed.

I am listening to Istanbul, intent, my eyes closed.

The Grand Bazaar's serene and cool,

An uproar at the hub of the Market,

Mosque yards are full of pigeons.

While hammers bang and clang at the docks

Spring winds bear the smell of sweat;

I am listening to Istanbul, intent, my eyes closed.

I am listening to Istanbul, intent, my eyes closed;

Still giddy from the revelries of the past,

A seaside mansion with dingy boathouses is fast asleep.

Amid the din and drone of southern winds, reposed,

I am listening to Istanbul, intent, my eyes closed.

I am listening to Istanbul, intent, my eyes closed.

A pretty girl walks by on the sidewalk:

Four-letter words, whistles and songs, rude remarks;

Something falls out of her hand -

It is a rose, I guess.

I am listening to Istanbul, intent, my eyes closed.

I am listening to Istanbul, intent, my eyes closed.

A bird flutters round your skirt;

On your brow, is there sweat? Or not ? I know.

Are your lips wet? Or not? I know.

A silver moon rises beyond the pine trees:

I can sense it all in your heart's throbbing.

I am listening to Istanbul.

İstanbul’u Dinliyorum

İstanbul’u dinliyorum, gözlerim kapalı

Önce hafiften bir rüzgar esiyor;

Yavaş yavaş sallanıyor

Yapraklar, ağaçlarda;

Uzaklarda, çok uzaklarda,

Sucuların hiç durmayan çıngırakları

İstanbul’u dinliyorum, gözlerim kapalı.

İstanbul’u dinliyorum, gözlerim kapalı;

Kuşlar geçiyor, derken;

Yükseklerden, sürü sürü, çığlık çığlık.

Ağlar çekiliyor dalyanlarda;

Bir kadının suya değiyor ayakları;

İstanbul’u dinliyorum, gözlerim kapalı.

İstanbul’u dinliyorum, gözlerim kapalı;

Serin serin Kapalıçarşı

Cıvıl cıvıl Mahmutpaşa

Güvercin dolu avlular

Çekiç sesleri geliyor doklardan

Güzelim bahar rüzgarında ter kokuları;

İstanbul’u dinliyorum, gözlerim kapalı.

İstanbul’u dinliyorum, gözlerim kapalı;

Bir yosma geçiyor kaldırımdan;

Küfürler, şarkılar, türküler, laf atmalar.

Birşey düşüyor elinden yere;

Bir gül olmalı;

İstanbul’u dinliyorum, gözlerim kapalı.

İstanbul’u dinliyorum, gözlerim kapalı;

Bir kuş çırpınıyor eteklerinde;

Alnın sıcak mı, değil mi, biliyorum;

Dudakların ıslak mı, değil mi, biliyorum;

Beyaz bir ay doğuyor fıstıkların arkasından

Kalbinin vuruşundan anlıyorum;

İstanbul’u dinliyorum.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Google Doodles today celebrating Halikarnas Balıkçısı, or the Fisherman of Halicarnassus, Cevat Şakir Kabaağaçlı, a 19th-century writer and son of an Ottoman diplomat who was exiled to Bodrum for the crime of “seditious writing,” and ended up spending the next 30 years in residence there, becoming an important figure in the “Blue Anatolia” (Mavi Anadolu) literary movement (the Mavicılar, or “Blueists” believed that all civilizations in Anatolian history formed a cultural continuum).

#mavicilar#blueists#mavi anadolu#bodrum#halicarnassus#Halikarnas Balıkçısı#fisherman of halicarnassus#cevat sakir kabaagacli#ottoman#blue anatolia#anatolia#history#ottoman history#google doodle#viafish

1 note

·

View note

Video

vimeo

The prologue to our new, 10-part series, “Big, Bent Ears: A Serial in Documentary Uncertainty.” Stay tuned next week for Chapter One, “There Are No Words” featuring Joseph Mitchell, Jonny Greenwood, and Big Ears.

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Boston University's Center for East Asian Archaeology and Cultural History has made available online some of the photos from its archive, including those from geologist Charles Samz's 1971 trip to Istanbul. They're basic vacation photos, snaps of markets and monuments, providing a wonderful glimpse into the color and movement of the city over forty years ago. The Bosphorus looks especially romantic in these saturated old film photos. It's also amazing to see boys and girls swimming together on the waterfront, something I don't see much of these days.

#bosphorus#boğaziçi#viafish#boston university#charles samz#1971#film#film photo#swimming#istanbul#fish#fishing#waterfront#seaside#turkiye#türkiye#turkey

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

If you're so inclined, check out the 1972 Turkish film Balıkçı Osman (Osman the Fisherman), a fun(ny) example of Yeşilçam-era cinema - the so-called golden era of Turkish filmmaking.

#yeşilçam#yesilcam#istanbul#turkey#türkiye#viafish#fishing#fish#bosphorus#boğaziçi#balık#balıkçılık#balıkçı

0 notes

Photo

Amateur fishermen on the Istanbul waterfront, twilight.

Istanbul - October 2013

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

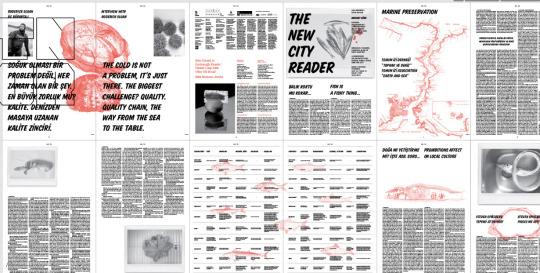

Image: The New City Reader

In a recent post I mentioned the New City Reader, a multi-series publication printed (in Turkish and English) in conjunction with the 2012 Istanbul Design Biennale.

The fish edition was edited by the legendary Istanbul chef, Mehmet Gürs, of Mikla fame, and features essays by food anthropologist Tangör Tan, environmental activist Olcay Bingöl, Scottish sea urchin harvester Roderick Sloan, and Gürs himself.

Go here to read the essays online (and if you know anyone who can get me a print edition let me know!)

#new city reader#tangör tan#mehmet gürs#mikla#fish#fishing#balık#balıkçılık#fish issue#istanbul#design biennale#istanbul design biennial#olcay bingöl#sea urchin#deniz kestanesi#roderick sloan#viafish#2012#turkish cuisine#food#seafood

0 notes

Video

vimeo

Trailer for a documentary about lüfer (bluefish) in the Bosphorus. A lot of connections here with what I am attempting to undertake in the oral history component of my project - nice to see others exploring this importent topic.

0 notes