Text

Allies and Tone Policing

In a previous post, I wrote about civility and bigotry. I still believe in what I wrote, to an extent -- mainly that we should try to assume a person is just ignorant, not malicious.

Some background on what prompted me to write that article...

A liberal Facebook page I liked shared a Tweet aimed at trans allies, saying that we were promoting lies by saying things like “gender and sex are not the same thing.” I was confused because, well, gender and sex aren’t the same thing. (Are they?) Several of us followers asked for clarification. Why was this wrong? If it really is wrong, then what is correct instead?

But rather than helping us understand our mistake (I still don’t think there was one), the page owner and several of their rabid followers accused us of being bigots. We were baffled. We tried to explain that no, we are not at all anti-trans, we’re allies trying to understand so we don’t inadvertently do harm.

The OP had suggested reading/following trans authors. We were asking how to find them. You can find the autistic community by searching for #actuallyautistic. Was there a trans equivalent?

The response was nothing but mockery and derision. “We’re not going to hold your hand, figure it out yourself,” and “Oh look, this one wants a cookie for being such a good ally.”

I unfollowed that page. I felt very confused and frustrated.

Meanwhile, a discussion about allyship was happening in a Facebook group for librarians. The group had tens of thousands of members and was very liberal. I figured if I could get reliable information anywhere, it’d be here.

So, in a discussion about allyship, I asked for a starting point to hear the authentic voice of trans folks, so I could be a better ally. I was shocked to get even more vicious dogpiling response than I had gotten from the other page.

I couldn’t believe the bullying I was seeing. I would never treat a sincere ally this way. If someone asked, “Where can I read things written by autistic people?” I would be thrilled to tell them about the #actuallyautistic tag, not mock and insult them for daring to ask!

I expressed this to the group. I told them I’m also LGBTQ+, disabled, and autistic. It made zero positive difference. If anything, they used it as fodder for further attacks. A group admin even joined in on the attacks and punished me by removing the Conversation Starter badge I had earned.

Sometimes Google is just too broad and you want to make sure you’re not getting bad info, but... what do you do? About a year later, I still don’t know how to find #ownvoices for trans people. And I am too afraid to ask anywhere.

So yes, I still stand behind my previous post about this. Sometimes allies do get bullied. This is an ugly truth we need to stop pretending doesn’t happen.

After the above situation, I saw people in other groups educating allies about self-education. They explained that marginalized folks are already exhausted from the daily battles they face in life (don’t I know it!) and that having to educate every single person they meet is further exhausting. They wished allies would attempt some research of their own first, and then ask for clarification if needed, rather than expecting the marginalized person to do all the heavy work for them.

That made complete sense to me and was certainly more helpful than “lol ally wants a cookie”! I understand that it takes a lot of emotional energy to educate, but the ROI is much better than mocking and insulting your allies.

My personal policy

If someone is being blatantly bigoted and hateful, I report the comment as hate speech and then keep scrolling. Trolls are not worth my precious limited energy.

However, what if someone seems to be ignorant or misguided but well-intentioned rather than hateful?

If I have enough energy, I educate them.

If I have less energy, I ask for help from others to educate them (e.g., “I don’t have the spoons for this right now, can someone please explain to this person?”).

If I have zero energy, I just keep scrolling without responding in any way at all. Because it’s not my job to educate the world. My primary job is to take care of my own health. Someone else can take on the burden for today.

That’s the beauty of a healthy community and allyship. We help each other. It’s a relay race, not a single-person marathon. If you don’t have the ability to control your emotions or educate people today, that’s fine! Walk away and take care of yourself. Not everything requires a response.

Having been on both sides of the matter, I really believe it’s better to give no response than to give a nasty one.

Now, on the flip side...

There are times when marginalized people are not bullying their allies, and yet are accused of doing that -- when the marginalized person’s justified distress is used as an excuse for allies not to listen to them.

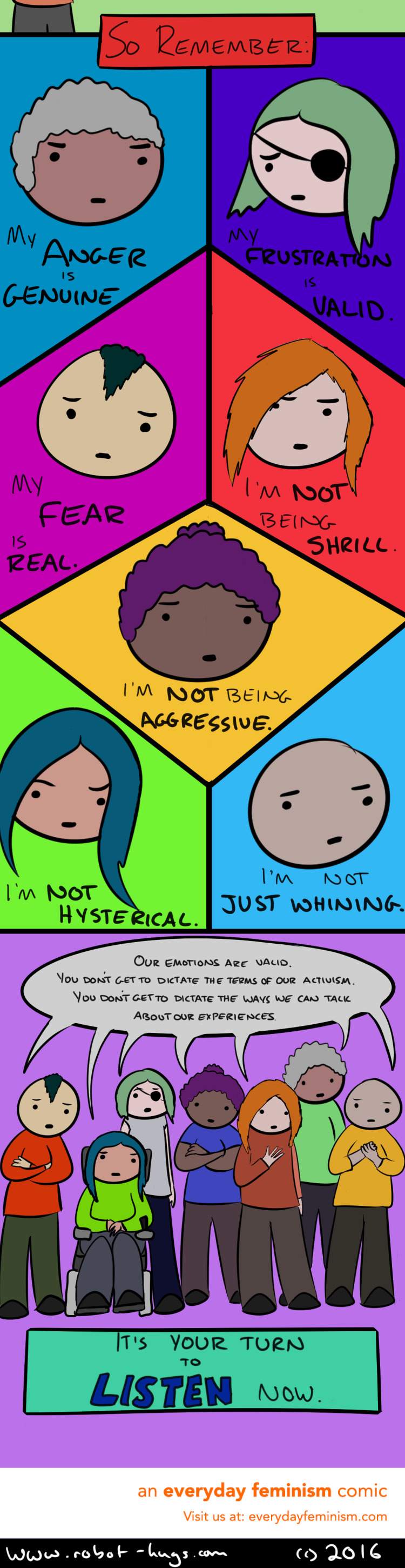

That’s where tone policing comes in. I found this comic strip to be fantastically informative. I hope you find it helpful, too. (If it’s too small to read, try this link. Tumblr doesn’t seem to play nice with these image dimensions.)

1 note

·

View note

Text

What the Spectrum Really Means

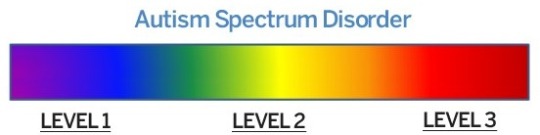

The following image is from a site explaining the DSM's entry for Autism. The levels indicate the amount of support a person needs in order to thrive.

Unfortunately, most people think the scale and levels indicate how "severe" a person's autism is, and they treat the person according to their perceived level of functioning, which is determined after the briefest of interactions with, or knowledge about, the person.

Consider the following examples. Note that these are real people whose names have been changed.

Nathan is part-owner of a successful international company. He lives independently. He drives and travels. He has friends and he loves to cook.

But Nathan has poor hygiene. He struggles to maintain eye contact. He paces and sways when anxious. He sometimes struggles to get words out. His friends, while very supportive and sincere, are mostly online, where these traits are not a factor. He can't judge distance very well, so he often backs into parked cars and has, so far, barely avoided serious road accidents.

On paper, Nathan seems to be high-functioning and “successful.” But people who meet him in person usually judge him as "barely functioning at all" and don't take his abilities seriously.

Julie is talkative and articulate. She's friendly and makes eye contact. She doesn't stim noticeably in public. She lives alone. She drives very well and enjoys it. She can focus for hours on a single task and has a strong work ethic. She has several acquaintances.

But Julie has no actual friends. Financially, she barely gets by on Social Security Disability. She burns out if she works more than a few hours a week in a traditional setting and has been terminated from jobs for not fitting in with their "culture" or for making innocent mistakes because of communication differences. She can't cook or keep her apartment clean on her own (she has even failed apartment inspections as a result). She needs hours of silent solitude to recover from just one hour of noisy socializing.

On paper, Julie seems to be low-functioning, and yet in brief public settings, she masks so well that people think she's not even autistic at all and don't take her needs seriously.

High-functioning means your needs are ignored. Low-functioning means your strengths are ignored.

The reality is that we all have strengths and weaknesses, just like neurotypical people, except maybe our peaks and troughs are more pronounced. So the spectrum really looks more like this:

#actuallyautistic#autism spectrum disorder#autistic spectrum#autism#functioning labels#high-functioning#low-functioning

14 notes

·

View notes

Link

Are you autistic? Do you go to concerts? This #ActuallyAutistic researcher is looking for your input on how to make concerts more accessible to our community!

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Respond to Autistic Critics: A Guide for Well-Meaning Neurotypicals

Let’s say you’re a neurotypical person who cares about an autistic person in your life (probably your child). An autistic adult approaches you with some concerns, criticisms, or information from another perspective. You feel attacked. How do you respond?

Don’t

Respond right away.

Do

Take time to calm down.

If the interaction is asynchronous (online, text message, etc), walk away and come back when you’re calm.

If the interaction is in-person or otherwise demands an immediate response, say something like, “Thank you for sharing this with me. I need time to process it. I promise I will give it a proper response as soon as I can.” This shows the person that you are taking them seriously. And as autistic people, we’re used to needing time to process complex things, so we will definitely appreciate this.

Don’t

Take it personally

Assume we’re saying you’re a bad parent/person

Treat it as a personal attack

Do

Remember that it’s not all about you.

This is especially hard for parents because nobody likes their parenting to be questioned. But none of us is perfect, and you’ll only ever grow if you’re open-minded. Unless the person is flat out saying, “You are a terrible parent,” then they are not saying that.

Remember that autistic people can generally be taken at face value because we tend to say what we mean and mean what we say -- nothing more. If we say, “I’m concerned when you say abc because xyz,” then we are saying we’re concerned about that one thing. Period. Don’t make it more than that.

Don’t

Tone police

Attribute their anxiety or perceived negativity to a personality trait (e.g., “You are just a negative, critical person”)

Do

Have compassion.

Remember that most autistic people have been through hell their whole lives because of the way the neurotypical world has treated them.

Most of us have at least some level of depression, anxiety, or even PTSD because of these interactions. It’s unrealistic to expect these repeated experiences not to colour our discussions about autism with neurotypicals.

You wouldn’t expect a woman who survived domestic violence not to get emotional when talking to a man who, while not violent himself, makes red-flag statements and reminds them of their abuser. It’s dangerous territory for us; of course we have feelings about it. We’re not robots.

Don’t

Condescend

Gaslight

Do

Take us seriously and treat us with respect and dignity.

Our feelings are valid, even if they’re not the same feelings you would have. Maybe we’ve taken the time to consider things you haven’t. That doesn’t mean we’re “overthinking” or “overreacting.” It means there might be something you can learn from us.

Just because our perspective differs from your own doesn’t mean it’s wrong. Take the time to consider it. Put yourself in our shoes, remember that our experiences have been different from yours, and give us the benefit of the doubt.

Don’t

Use our autistic traits against us (e.g., calling us naive, pressuring us to respond faster than we’re able)

Do

Respect our differences.

Yes, we are often naive. Many of us see that as a positive thing; it means we’re honest. Using it as an insult makes us insecure about aspects of ourselves that should be celebrated instead.

Yes, we take longer to respond properly. This means we’re giving the matter a lot of consideration. Isn’t that a good thing?

Think about how you’d want someone to talk to your child. How would you feel if they mocked your child’s naiveté? If you wouldn’t want your autistic loved one to be bullied, don’t bully other autistic people!

Don’t

Tell us it’s not our business

Dismiss us (e.g., “You’re entitled to your opinion,” “You are not my child’s advocate”)

Do

Be grateful someone cares enough about your child to speak up for them.

If you’re not going to be your child’s advocate, someone should. Having lived for decades as an undiagnosed, unsupported autistic individual, I would be pretty heartless if I didn’t feel some connection and obligation to other people going through similar things. Maybe you feel like other people’s trials should never affect you, but some of us are more caring than that.

Don’t

Say we are not like your child (implying we have no right to speak up for them)

Do

Remember that we are more like your child than you can ever understand.

We might have jobs and relationships. We might be verbal. We might not rock back and forth. We might make what looks like eye contact. We might have above-average IQ. And your child might not have/do those things. That doesn’t mean we aren’t like them.

The neurotypical world seems to think that outward behaviours (e.g., stimming, being verbal) and societal markers of “success” (e.g., job, relationships) is what makes one person more or less autistic than another. First of all, there really is no such thing as “more” or “less” autistic. We’re autistic, period. We might need more or less support, but that doesn’t mean we’re not still autistic.

The idea that these outward behaviours are what make a person autistic is the reason I didn’t get diagnosed until I was 36. You know how I realised I was autistic? I came across the blog of a woman who was actually autistic. I finally read the thoughts and feelings of an autistic person, and it felt like she was in my head. Once I started looking under the surface, the self-discovery was life-changing.

It turns out, I do stim. I just don’t do it as much in front of other people, and when I do, it looks like nervous fidgeting (picking my nails instead of, say, flapping my hands), which is more socially acceptable and camouflages my autism from others -- and even from myself, for over 3 decades.

It turns out, I do struggle with eye contact. I always thought I was “making eye contact” when really I was looking at the person’s mouth -- if I look at their face at all. But if I force myself to look into their actual eyes? I feel like I’m being attacked and my brain stops processing what the person is saying.

Again, perceived outward behaviour doesn’t always match the inside.

I “pass” as neurotypical. When colleagues find out I’m autistic, they invariably have the same response: “I would never have known.” Yeah, well, that’s because you probably wouldn’t be working with me if I didn’t mask my true self to the point of exhaustion, because neurotypical bosses wouldn’t hire me.

Do NOT mistake my successful masking (which is extremely bad for my health, by the way, so I use the word “successful” with a heavy dose of irony) for lack of autism. They are not the same thing.

Yes, I am like your child. Listen to me when I advocate for her. I know what she’s going through because I’ve been there. Maybe not exactly the same (we are all different), but almost certainly more than you.

In 2018, a study was conducted at the University of Edinburgh. It was groundbreaking because it didn’t assume neurotypicality was the correct way. It gave equal footing to both neurotypes. And it found what autistic people have always known: that our way of communicating, socialising, and experiencing the world is not pathological or ineffective; it truly is just different.

When the autistic participants were tasked with communicating information to one another, they were just as effective as neurotypical people tasked with communicating information to other neurotypicals. Ineffective communication only happened in groups of mixed neurotypes.

This explains why, when I’m around other autistic people, I can take the mask off and safely be myself. We get each other.

In other words, autism is like a different language and culture. So instead of dismissing me because I have learned to speak your language to a greater degree than your child has, maybe you could see me as a valuable asset because I can be a translator for your child. Instead of treating me as a threat, treat me as an ally. Because that’s what I want to be.

0 notes

Text

Civility and Bigotry

There’s a lot of talk about how marginalized people should not have to be nice or calm, and how it’s not our job to educate ignorant people. Here are my thoughts on the matter (and yes, I am a marginalized person -- disabled, LGBT+, low-income, female, and neurodivergent).

I wish people could assume best intentions more often. I wish that when someone expresses a sincere desire to support us, to learn and do better, we could say, "I appreciate your intentions, but you seem to have gotten some bad information. Try reading this author, or searching for this hashtag." It's not always that easy, but it often is -- more often than you'd think. It doesn't always have to be exhausting (or exhaustive). Just a small nudge in the right direction can be enough. Because we all have blind spots, things we don't realize we're ignorant about.

For example, I'm autistic, and there's a LOT of misinformation about autism out there. Unfortunately, it's the info that dominates the public conversation. It's the "light it up blue" campaign and "autism awareness month" people participate in, thinking they're helping us, when in fact it actually does harm. When I talk to a person about autism, I have a few go-to books, articles, and hashtags to refer them to.

If they're truly interested in learning, they will check those things out. I'm not going to bring the items to them on a silver platter. I'm not going to spend all day educating them. I'm just pointing them in the right direction and letting them decide whether they care enough to take the steps to educate themselves.

Not all of them do. Some of them are more interested in virtue signalling than in real growth and allyship. But it doesn't cost much time and effort for me to give those tips, and if it means some people DO end up learning and growing, and then going on to educate others... it's worth it to me to have spent those few seconds orienting them toward good info.

I understand that some people really are only interested in being a bigot, and those people aren’t worth your time. But I still think we're more effective when we assume best intentions until we know for sure otherwise, and when we don't purposely escalate already-tense interactions. Even if the direct recipient isn't listening right now, you might plant a seed that grows long after you're gone. You can also model positive interactions for others observing the dialogue, or open their eyes to knowledge they didn't know they lacked.

I understand being exhausted by this stuff (every April, I have to do a lot of self-care to get through all the anti-autism crap), and I absolutely don't think it's our job to hand-hold ignorant people. However, I'm also pretty tired of people using this stance as an excuse to be an outright a-hole themselves. Just because someone else is being ignorant, doesn't mean it's a good thing for us to be petty and cruel ourselves. Like, why do we have to go from one extreme to another? If you don't have the energy or desire to offer even the smallest tip to such people, that’s fine, but why choose to escalate conflict? Why not just walk away and live your life? One of my favourite quotes these days is: "You don't have to attend every fight you're invited to."

0 notes

Link

So, this piece on ABA is written by a dog trainer with a degree in psychology and it’s one of the most devastating take-downs I’ve ever read.

Choice quotes:

Quite commonly on Twitter, I’ve seen people call ABA “dog training for children.”

When I see that, I tend to go on Twitter rants in reply to it, because from everything I have read and seen of ABA, it is NOT “dog training” for children.

…I would never treat a dog that way.

The founder of ABA as it exists today, Ivar Lovaas, who is also the father of gay conversion therapy, derived the principles of his therapies from radical behaviourism.

Radical Behaviourism is considered out-of-date by modern psychologists.

I can understand why Applied Behaviour Analysts decided to rename it as “Behaviour analysis,” but a rose by any other name is still radical behaviourism.

In any case, very few dog trainers use the radical behaviourism that’s employed in ABA.

Most of the dog trainers I know mix and match behaviourism with other cognitive science research and other methods to create a more holistic approach to training their dogs. This is because dog trainers understand the limits of behaviourism on canines, because it doesn’t address the whole dog.

One of the reasons parents and ABA professionals get so upset when autistic people call ABA “abusive” is the fact that they care deeply. They genuinely want to improve these children’s lives. Yet the vast majority of autistic people when polled (typically 97%) oppose ABA including and especially those who went through it as children.

Why is there such a disconnect?

Some of it has to do with a breakdown in the way autism is perceived. Non-autistic people believe that “normalcy” is a fundamental need; indeed, a stated goal of ABA is to make the autistic child “indistinguishable from [neurotypical] peers.”

They think a child who blends into the crowd is a happy child.

When parents see their child engaging in unusual behaviours such as flapping, or ignoring other children, they see a child who is ill or damaged.

When they see that child talking and working well at their desk and playing with other children, they see a child who has been healed. Helped. Saved.

Flapping and echolalia (repeating words or phrases), similarly, are expressions and often play an important emotional role as well as a developmental role. Echolalic speech helps autistics, many of whom process language in a different part of the brain, to process the language they have heard and understand the meaning of the words.

Yet, ABA seeks to “extinguish” these things.

A good dog trainer doesn’t extinguish behaviours which improve the dog’s mental health and happiness. But an ABA practitioner may not think twice before doing this to a human child.

Like all certifying bodies, the Behavior Analyst Certification Board has a professional code of ethics which its certificants must abide by to remain in good standing.

You can read them here.

I was amazed when I read it, because while it goes into great detail regarding what certificants may do with regard to the business aspect of things, right down to detailed guidelines on what you can do and say in the media, there is virtually nothing about the welfare of the therapy’s recipients.

The Certification Council of Professional Dog Trainers (CCPDT), by contrast, dedicates almost the entirety of its code of conduct to what, when, and how you interact with the animal. While it also covers ethical business practices, its primary concern is the well-being of the “learner”.

The BACB says nothing about inflicting pain. There’s nothing in the BACB ethics code says you can’t use electric shock. In fact, it doesn’t say anything at all about what type of “aversives” are acceptable.

As long as the aversive procedure is effective and accompanied with training and supervision, under the ABA model you could hypothetically do anything.

Dog trainers understand that dogs need to chew and bark and dig, but ABA therapists don’t understand that autistic children need to repeat words and sentences, flap their hands, and sit quietly rocking in a corner when things get too much.

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Deficit or Difference?

Supposed deficits in communication and socialization are major staples of “clinical autism”; that is, autism as defined by the neurotypicals who write about us in diagnostic manuals, publish books and scholarly papers about us, and run “awareness” campaigns about us.

Certainly, some autistics do struggle to communicate verbally. And some struggle with putting names on their feelings (alexithymia). But overall, autistics feel like we’re able to communicate just as well as the average neurotypical, if not better.

We are much more direct, for one thing. A neurotypical person will dress up their point in flowery “diplomatic” speech. They’ll say one thing and mean another, expecting you to “read between the lines.” By contrast, an autistic person will usually say exactly what they mean and mean what they say.

Ironically, instead of seeing this as good, clear communication, neurotypicals tend to conclude that we are too blunt, or even rude. They think that, because we can’t play their read-between-the-lines game very well, then we must have a deficit in the ability to communicate. Meanwhile, we think they struggle with communication since they can never simply say what they mean.

They like to use their tone of voice, facial expression, and eye contact as methods of communication. For us, staring into each other’s eyes is not only super uncomfortable, but actually impedes the ability to stay focused on what’s being said. We’re more focused on the actual words (this is one reason we often prefer text to in-person discussions).

Could it be that autistics and neurotypicals simply have different, but equally valid, communication styles?

In September of 2018, the University of Edinburgh conducted a study to answer this very question. The results have not yet been published or peer-reviewed, but the team shared their preliminary results with the autistic community directly.

The results are not surprising to those of us who have lived our whole lives as autistics in a neurotypical world. But for neurotypicals, this news will be earth-shattering.

Before we dive into the results, I just want to take a moment to acknowledge the significance of this study even existing. It means that someone took the autistic perspective seriously. That in itself is huge, as it’s not often our perspective is considered legitimate.

Additionally, half of the team members are actually autistic themselves. And when the data started coming in, the team shared it directly with the autistic community. Their website says:

“Best practice in autism research features equal partnerships between academics and autistic community representatives. This is reflected in our research approach.”

This is how it should be -- nothing about us without us. But it rarely is that way. So this study is remarkable simply for breaking that mold.

The study consisted of a number of experiments involving three groups: autistics, neurotypicals, and mixed (both autistics and neurotypicals).

In one experiment, participants played the classic game of telephone.

When the participants were all the same neurotype (all autistic or all neurotypical), the story got diluted at the same rate, no matter what the neurotype was. It was only with the mixed-neurotype group that the communication noticeably broke down.

Think of an English person and a Chinese person who learn each other’s language as adults. No matter how fluent they become, they will always feel more comfortable speaking their native tongue with other natives. And there will always be aspects of the second language that feel foreign, cultural nuances that will always be elusive, and so on.

But we wouldn’t say, “Chinese people have a language deficit,” would we? Well, maybe we would, actually... if we were living hundreds of years ago when the English considered everyone else “savages.” But we’ve become so much more enlightened since then! Now we know that different doesn’t mean inferior.

. . . Or do we?

Another experiment in the study measured perceived comfort or awkwardness when socializing one-on-one. When the pair was of a matching neurotype, their comfort levels were pretty much the same, no matter what the neurotype was. It was only when the pair was of a mixed neurotype (one autistic and the other neurotypical) that they felt really uncomfortable. This discomfort was noticeable to both participants, and even to a third-party observer.

So again, it’s not that autistic people are inherently awkward or unsociable. It’s just that our social language is different from that of neurotypicals. We feel about as much at ease around each other as neurotypicals do around their own kind. It’s only when you mix us up that we feel awkward. Probably because we know we’re expected to speak the neurotypical’s language, and we know we’ll never do it “right.”

What this study finally shows -- and what autistic people have always known -- is that the neurotypical way is not the only right way. We have a way of doing things that’s just as valid as yours.

It’s not a deficit; it’s just a difference.

You can read more about this fantastic study here.

0 notes

Text

Paradox of Age

I didn’t seem to fit in with my peers growing up. In elementary school, I could usually find a kid or three to be friends with, but when I moved from the American south to the north at age 10, that all changed. Not only did I have culture shock to deal with, but also the growing complexities of incipient adolescence.

My female peers spent their free time looking through tween magazines and giggling together about celebrity heartthrobs. I spent my free time walking through the woods and excitedly showing my aunt some fascinating piece of nature I had discovered.

This aunt was my godmother and mentor. She was an artist, like me. A dreamer. Someone who saw the world a little differently than most people. Someone who understood me more than anyone else.

Sometime between age 10 and 12, I confided in her about my social struggles. Rather matter-of-factly, she explained that I was both more mature than my peers and less mature.

I immediately, instinctively knew this was true, though at the time I didn’t know why. Now, through the autistic lens, it makes sense. It’s actually quite common among autistic people, perhaps especially females (our society lets men act like boys all their lives, but women are expected to be the real grownups).

As a child, I tended to gravitate toward adults. They usually didn’t mock me or make me feel excluded. They tended to understand intellectual thinking and encourage an inquisitive mind rather than belittle it. I felt safe around adults. In these ways, my peers would say I was “boring,” or an “old lady,” or a “teacher’s pet.”

I also tended to gravitate toward kids younger than myself. They tended to like similar activities (I was into colouring books and cartoons long after my peers moved on to more “age-appropriate” recreation). Younger kids weren’t into the drama of middle school yet. They were still naive enough to be themselves authentically instead of being self-conscious and contrived.

My peers would call my childlike traits “childish” or even babyish. Simple. Unsophisticated. “Dumb.”

Now, I think if I had to choose a few traits from the child column and a few from the adult column, mine would be the best combination. I don’t say that from conceit but from objective observation. Think about the alternatives.

From the “mature” side, you could be cynical, fake, and manipulative.

And from the “immature” side, you could be petty, thoughtless, and selfish.

We see that combination all too often in people. But we don’t say they’re “out of sync with their peers” or “maladaptive.” We might call them jerks, but nobody says they’re psychologically “abnormal.”

So if an autistic person has positive traits from each column -- with the innocence of a child and the thoughtfulness of an adult -- why pathologise them? Instead, we should try to do as my aunt did: celebrate and nurture them as they are.

1 note

·

View note