#yoshika miyako

Text

yoshiii

753 notes

·

View notes

Text

China

543 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's this year's annual birthday illustration!!!

I think this one is my favorite one so far, happy shared birthday Miss Crown Prince! Spare me some of your long lifespan... 🥂🎂🎉

(+stupid silly discord interaction doodle featuring improvised funny touhousonas under the cut)

#touhou#touhou project#2/7#toyosatomimi no miko#miko day#mononobe no futo#seiga kaku#soga no tojiko#yoshika miyako#me art#artists on tumblr#I am no longer the funny song age. welcome sweet terrible 24#I love celebrating my birthday by ignoring myself and focusing on fictional characters who share it w me instead. very fun would recommend#I based my friends oni sona on their design of their fusona!!! they are @candybaphomet here and they are very funny as you can tell

554 notes

·

View notes

Text

touhou doodle log

#touhou#satori komeiji#chiyari tenkajin#sanae kochiya#yoshika miyako#takane yamashiro#my art#yippeeee

543 notes

·

View notes

Text

doki-doki waku-waku 💜

334 notes

·

View notes

Text

Akatsuki Records stickers now available!

Water resistant, metallic stickers are up on my store! Each sticker was inspired by the touhou promotional video of their origin.

For those who haven’t heard:

Chupacable?

Coooonsultant!

HANIPAGANDA

Necromantic

#touhou#東方#akatsuki records#暁records#chiyari tenkajin#tsukasa kudamaki#mayumi joutouguu#seiga kaku#yoshika miyako#touhou project#my art#coooonsultant#hanipaganda#necromantic#Chupacable

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

touhou sketches

#digital#fanart#touhou#touhou project#touhou fanart#seiga kaku#yoshika miyako#miyako yoshika#mamizou futatsuiwa#marisa kirisame

374 notes

·

View notes

Text

digital fan art of yoshika miyako

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

round two of these

last post | next post

#touhou#reisen udongein inaba#youmu konpaku#marisa kirisame#reimu hakurei#sanae kochiya#seiga kaku#yoshika miyako#satori komeiji#rin kaenbyou#yukari yakumo#chen#saki kurokoma#suwako moriya#kanako yasaka#fujiwara no mokou#keine kamishirasawa#text posts#incorrect quotes#my edits#wough these have so many tags#also the sickness mentioned before turned out to be covid but i'm getting better 👍

690 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Roaming into immortality”: Ten Desires and the history of Taoist immortals

As promised last month, following the freshly established tradition I have another Touhou research post to offer. This time, we’ll be looking into the literary traditions focused on Taoist immortals (or, following the Touhou convention, “hermits”, though this is a less suitable translation) and how they influenced Ten Desires. Due to space constraints and thematic coherence, note that only Seiga, Miko and Yoshika will be covered.

Before you'll begin, I need to stress that one of the sections requires a content warning. While all images are safe for viewing, there's a description of a potentially unpleasant episode involving unwanted advances, and various events leading to that; I highlighted that before the relevant paragraphs too just in case.

“Hermit”, “immortal”, “transcendent”

A post about Ten Desires must start with an introduction of the term sen, the Japanese reading of 仙, Chinese xian. Touhou specifically uses its less common derivative 仙人, sennin, though that's just a synonym. Touhou-related sources basically invariably translate this term as “hermit”. While this option can be found elsewhere too, it is not exactly optimal.

“Immortal” is actually the standard translation for both sen/xian and sennin, as far as I am aware. I did a quick survey of recent publications on Brill’s and De Gruyter’s sites and the results were fairly unambiguous, especially for books and articles published after 2000, with “hermit”, “wizard” and other alternatives being quite uncommon. The trend is not new, with sennin already translated as “immortal” in the 1960s.

When it comes to xian/sen, in a few cases arguments were made that “transcendent” or “ascendent” would be a more suitable option as it better illustrates the position of these beings, though this is a relatively recent trend, for now limited to Sinology. The idea behind it is that immortality is just one of multiple characteristics attributed to the xian, and it is ultimately the transcendence to a higher level of existence that’s the key element. I personally think the argument is sound, but not all translators have embraced it, and for now the choice is really a matter of preference. Since “immortal” is more widespread, and most of the sources in the bibliography use it, that’s what I will employ in the rest of the article, save for direct quotes from Touhou, where "hermit" will be used.

Early history of immortality in Chinese sources

Feathered immortals worshiping Xi Wangmu (from Betwixt and Between: Depictions of Immortals in Eastern Han Dynasty Tomb Reliefs by Leslie Wallace; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

The notion of pursuit of immortality, or at least longevity, is first attested in Chinese sources in the eighth century BCE, when the first bronze inscriptions revealing their authors wished to avoid death altogether appear in the archaeological record. However, the ideas which directly lead to the development of the concept of immortals as discussed here only started to develop in the fourth BCE. Initially they were associated with so-called fangshi, a class of multi-purpose esoteric specialists who often served for example as court diviners.

These ideas developed before the unification of China by Qin Shi Huang, but their importance grew after this event, as many of their proponents were warmly received in the courts of Qin and Han emperors. Some of them, like Wu of Han, even sent expeditions in search of distant lands where immortals purportedly lived, of which Penglai is the most famous.

As a curiosity it’s worth mentioning here that the reception of these pursuits was actually mixed in Chinese historiography. Some of the rationalist Eastern Han authors such as Wang Chong evaluated it critically, basically describing it as a waste of time and resources leading to poor governance.

We know relatively little about the development of beliefs focused on immortality outside of the imperial court in the Han period, though it is evident that they gained considerable prominence, and it’s even possible to speak of “immortality cults” among the general populace. That’s for example seemingly how the worship of Xi Wangmu, arguably one of the most famous Chinese deities, became widespread. Tomb paintings showing blissful immortals also appear in this period.

In art immortals were initially depicted as winged, feathered beings. The origin of this tradition remains unclear, though it has been noted that various similar bird-like beings are also listed in the Classic of Mountains and Seas, attesting to this being a widespread motif in early Chinese tradition. You might be familiar with portraying immortals as wizened sages instead. This convention only developed when the image of the immortal merged with that of the ascetic hermit in the Eastern Jin period - more on that later.

Immortals in Ge Hong’s Baopuzi

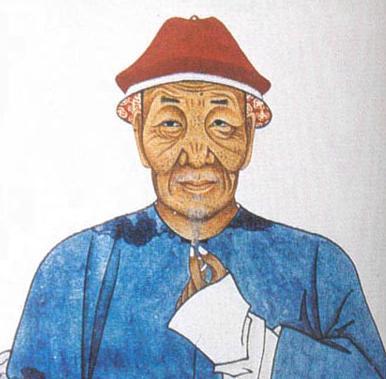

A 20th century illustration of Ge Hong (wikimedia commons)

The first formalized instructions for the pursuit of immortality were compiled during the reign of the Eastern Han. Some of them were rooted in the early Taoist tradition, which at the time was also being partially formalized under the Way of the Celestial Masters. Seemingly many Taoist works dealing with these matters were compiled, but most of them are only known from references in Ge Hong’s Baopuzi, one of the most important texts for the study of the history of ideas about immortality.

Ge Hong states that immortality can be obtained through personal virtue and specific practices, including exercise, following strict dietary restrictions and, most importantly, through engaging in alchemy, which he hails as the most effective. All the means to obtaining immortality were unified by one principle: cultivating qi, both by maintaining one’s own and by absorbing it from the right kinds of plants and minerals. Grains were held to be inappropriate food for those pursuing immortality, as it was believed they nourished the so-called “three worms”. The final goal was to be able to use morning dew or light for sustenance. The easiest way to move towards that goal was believed to be consumption of alchemical elixirs, said to possess a more potent, refined form of qi of all their carefully selected ingredients.

Needless to say, many of such magical concoctions were highly poisonous thanks to the inclusion of mercury, cinnabar and other similarly exciting substances. Ten Desires describes the consequences pretty accurately: Miko “turned to the use of various unusual materials, such as cinnabar” which “ruined her body”; as a result she “destroyed her health because of the very Taoism that was meant to grant her immortality”. Such a fate is not historically unparalleled, and there is even a strong case to be made that the notoriously erratic behavior of some of the particularly immortality-obsessed emperors was the result of alchemically induced heavy metal poisoning.

Cinnabar cocktails aside, a further important piece of information from Baopuzi is the reference to three classes of immortals, celestial (天仙), earthbound (地仙) and corpse-liberated (尸解仙). What separated these three groups was the degree to which they perfected their state before formally attaining the rank of immortal. The most refined were basically invited into heaven, with the best of the best taken there on the back of a dragon. Those who despite their efforts lacked something had to put in some additional effort themselves instead.

While the "celestial" and "earthbound" immortals are largely self-explanatory (we'll go back to them later, though), the label of “corpse-liberated” warrants a more detailed explanation. It refers to those who settled for faking own death. This act is called shijie (尸解), and involves substituting the body for an object, which is to be buried as if it was a person. Of course, immortality obtained this way was effectively second rate, though it was not impossible to become a proper celestial immortal later on. As you can probably notice, this is precisely the path to immortality ZUN has chosen for characters in Ten Desires. The term shikaisen used multiple times in the game is in fact simply the Japanese reading of 尸解仙.

Immortals in secular literature

Four Immortals Saluting Longevity by Shang Xi (wikimedia commons)

The importance of the search for immortality grew during the Six Dynasties period. Seemingly in all strata of society a common reaction to frequent political turmoil was to seek solutions in Taoism and still relatively new Buddhism. This in turn left a huge impact on Chinese culture of this era as a whole.

What is of particular relevance for this article is less the straightforward religious dimension of immortality, and more its reflection in literature. Works about immortals were already being written in the Western Han period, with the oldest surviving example being Liexian Zhuan (列仙傳) attributed to Liu Xiang, who lived in the first century BCE. Their importance only grew with time due to the aforementioned process, and they became a well established part of both poetry and prose. For example, a sixth century treatise on literary genres, Xiao Tong’s Selections of Refined Literature (文選; Wenxuan), pretty much the main source to fall back on in the study of pre-Tang literature, recognizes youxian (遊仙), literally “roaming into immortality”, as a distinct type of lyrical poetry. There’s a considerably degree of nuance to this term, since 遊 has the implications of leisurely, playful activity, but these lexical considerations are beyond the scope of this article.

While in some cases the tales of immortals focused on figures primarily known for other reasons, like the Yellow Emperor, Chang'e or Laozi, many document the lives of historical pursuers of immortality instead. Well attested fangshi and Taoist masters appear in such a context, for instance Anqi Sheng or Liu An (according to a legend he ascended to heaven with his entire household, including dogs and other animals).

The literary biographies, or rather hagiographies, of immortals often highlighted their personal eccentricities, tied to their detachment from society. The archetypal eccentric immortals are obviously the members of the group popularly known as the Eight Immortals, though this is a much later development, and the genre conventions formed centuries earlier.

Literature about immortals is interesting from a modern perspective because at least in part it was arguably a secular pursuit. As secular as something could be prior to the rise of the modern notion of secularism, that is (see Mark Teeuwen’s article on Edo period secularism for some arguments against seeing secularism as an entirely modern phenomenon). This is not merely the modern perception, for clarity - the earliest statements to that effect can be found in works of literary criticism from the second century or so. The writers were chiefly scholars, courtiers and officials, not clergy, and naturally their works are not recognized as “canonical” Taoist literature.

Some of these authors took the topic of immortals into rather peculiar directions. According to Xiaofei Kang, during the Six Dynasties period amorous encounters with female immortals (仙女, xiannü) were a “fashionable topic among literati”, while in the subsequent Tang period some authors compared courtesans they sometimes were actually involved with to immortals metaphorically. She notes that they effectively created a genre of works focused on immortals which was no longer really describing the pursuit of immortality, but rather “encounters with enchanting beauties, both real and imagined”.

Needless to say, the literature about immortals remained relevant in later periods, and new stories continued to be written under the reign of subsequent dynasties. Many can be found in Pu Songling’s famous Liaozhai (Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio). This collection was written in the Qing period and remains in wide circulation today as a literary classic.

Pu Songling’s tale of Qing’e: the origin of Seiga

Pu Songling (wikimedia commons)

It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss all of Pu Songling’s tales about immortals, but there is one which necessitates further discussion, namely Qing’e, which is very obviously the basis for Seiga’s character. This makes her somewhat unusual among Touhou characters - while the story she is based on deals with religious themes, and fiction can shape religious views at times (as evidenced by the popularity of Sun Wukong or the image of hell in Divine Comedy), I found no indication Qing’e was ever views as anything but a literary character.

Like the rest of Liaozhai, the Qing’e tale has been translated into English in the 2000s. Songling’s works have an older and more famous translation too, but it’s just a selection, and it has many issues, which you can read about here. You can read parts of the more modern translation on Google Books. Obviously it can also be found easily in other places. I will also summarize the story of Qing’e below for convenience.

This is where the content warning I mentioned applies: the story is not very explicit, but there are is a scene of what I think counts as attempted sexual assault and other generally unsavory moments of that sort, so if that bothers you, skip ahead to the next section.

The beginning of the story introduces a certain Huo Huan (霍桓) from Shanxi, a sheltered young man of unspecified age (he’s older than 13 but “ignorant of adult desire”, which is pretty vague). He lives in the same neighborhood as the eponymous Qing’e (青娥), a teenage daughter of a certain mr. Wu (武), who was apparently a devout Taoist. Qing’e secretly read through her father’s personal collection, developing an admiration for He Xiangu in the process. When mr. Wu left for the mountains to become an immortal, his daughter declared she will never marry. Her decision is presumably meant to mirror one of the versions of the tale of He Xiangnu, who reportedly attained immortality by remaining celibate and consuming mineral powders (granted, you can also find versions where her immortal career started when she was seduced by Lü Dongbin, but that does not match the story here).

He Xiangnu by Zhang Lu (wikimedia commons)

Huan sees Qing’e outside at some point and, without really talking to her, decides she has to marry her and asks his mother to send someone to arrange that. she doesn’t think it’s a good idea, but eventually caves in. Lo and behold, it doesn’t work and the Wu family is not interested in the proposal. Huan then meets an unrelated Taoist, who offers him a magical tiny spade (one chi long) used to dig up Taoist-preferred herbs (a key component of the immortality keto diet), which can quite literally hack through stone. This convenient deus ex machina gives Huo the idea to hack through the walls of the Wu residence to see Qing’e. Note that the narrator does not approve of this plan, and calls it an “illegal act”. Alas, it comes to pass anyway,

With this newfound power Huan watches Qing’e undress before she goes to bed and then listens to her breathing while she is asleep, as one does with women they saw exactly once before. Eventually he falls asleep himself on her bed. Needless to say, when Qing’e wakes up she is less than thrilled and summons her servants. They assume Huan is a thief, but he tries to explain himself. He’s set free, but the magical tool is confiscated.

Since Huan does not know when to quit, he arranges for a second round of matchmaking afterwards. While apparently Qing’e is cautiously optimistic about it this time, her mother is less than thrilled after learning there are now holes in their residence’s walls. She insults the matchmakers, Huan and Huan’s mother. This in turn makes Huan’s mother angry. She apparently concludes that Huan and Qing’e had sex, and declares that instead of damaging her good name someone should’ve just killed them both on the spot. Qing’e is genuinely sad about this and sends a messenger to smooth things over. However, ultimately nothing really comes out of it.

Some time later, Huan starts a career as a helper of his town’s magistrate, Ou. The latter is surprised to learn he is not married yet, and after hearing about his unsuccessful endeavors intervenes himself. With the help of other local officials he secures the permission of Qing’e’s mother, and the marriage is officially arranged.

A year later, Qing’e arrived at Huan's home. She brings the magical tool with her, and declares that it is no longer needed. However, Huan decides to carry it with him as a good luck charm, pointing out acquiring it was what led to their marriage. Some time later newlyweds have a son, Mengxian, but Qing’e is not interested in raising him and entrusts that entirely to a nurse. After some more time, in the eighth year of their marriage, she announces to Huan that their time together is coming to a close, and there is nothing to be done about this. Shortly after that, she seemingly dies, and Huan and his mother bury her - or so they think, at least.

In the aftermath of this event Huan’s mother falls sick, and inexplicably develops a craving for fish soup, which is hard to obtain in the area the story takes place according to the narrator. Huan, as a staunch believer in filial piety, decides to embark on a journey to procure some. He is initially unsuccessful, but he manages to get some from Wang, an old man he encountered in the mountains. The latter also offers to introduce him to a beautiful woman, but Huan is focused on the quest for fish soup and declines.

Contemporary Chinese fish soup (wikimedia commons)

With the power of fish soup Huan’s mother’s health is restored, and when it becomes clear she’s going to be fine he decides to seek Wang again. He does not find him, but after a long trek in the mountains he instead stumbles upon an unusual cave. Unusual because there’s a house inside it. a house which, as it turns out, is inhabited by Qing’e.

Qing’e is surprised to see Huan. She explains that she faked her death and in reality a bamboo cane was buried in her place. She concludes that if Huan found her, they are presumably fated to be together as immortals. He is then taken to her father, who as established earlier also became an immortal. The initial reception is positive, but Huan makes a scene demanding that Qing’e have sex with him and keeps clutching her arm when she declines. Qinge’s father intervenes, and kicks him out for attempted sacrilege in his hermitage.

Alas, Huan can’t get a clue as already established. He cannot see the house anymore because due to a trick there’s only a cliff in front of him after the doors close, but that’s not really enough to stop him, as he suddenly remembers he has the magical tool with him. He starts digging, and despite insults hurled at him from behind the rocks eventually makes a sizable hole in the cliff. At this point someone, presumably Qing’e’s father, gets fed up, and throws Qing’e out through the hole to get him to leave.

Qing’e, to put it lightly, is not very keen on this turn of events. She nonetheless returns with Huan to his house. Shortly after that they moved elsewhere, to Yidu, where they lived for eighteen years. Qing’e at some point gave birth to a second child, a nameless daughter, who doesn’t really factor into the story. All we hear about her is that she married into a local family.

Eventually Hano’s mother dies. Qing’e picks an auspicious location for her resting place, and tasks Huan and Mengxian with preparing the burial. A month later, she and Huan disappear, leaving the new adult Mengxian alone.

In the final scene of the story, Megxian, who apparently spent the first twenty or so years of his adult life unsuccessfully attempting to pass the imperial examination, meets a certain Zhongxian, and is amazed to learn they bear the same surname. The two quickly realize they’re brothers, and decide to meet with their parents, but they fail to accomplish that since they left Zhongxian’s house in the meanwhile.

The narrator comments that while Huan’s actions were “foolish” and “crazy”, everything he had striven for was granted to him as a reward for his filial piety, and then marvels why nobody stopped him and Qing’e from having more inevitably abandoned children. “That’s really strange,” he remarks.

Seiga’s character between ZUN’s innovations and Taoist tradition

Seiga explaining the powers of a hermit; if only there was a term which makes this explanation even more straightforward... (WaHH chapter 12.1)

As you’ve probably noticed, Seiga’s bio in the Ten Desires omake is remarkably faithful to the adapted source. Even her name is just a Japanese reading of the combination of Qing’e’s given name with the family name of her husband. It does not seem that everything unfolded identically in Touhou, though. There is no indication in the bio, or anywhere else for that matter, that Seiga went back after faking her death, and we instead learn that she decided to travel to Japan, since Taoist “hermits” were uncommon there. Additionally, Seiga presumably kept the confiscated chisel, since her ability, which she eagerly demonstrates in Wild and Horned Hermit, is rather obviously a direct reference to the tale of Qing’e. I will admit that while I do not question Pu Songling’s talent and enjoyed many of his tales, I think ZUN’s version is more satisfying than the original, perhaps because from a modern perspective Qing’e is arguably a more compelling protagonist than her husband, and Touhou effectively treats her as the main character in this story.

Something that I believe is relatively well known is that Seiga’s entire character is a bit of an anachronism: to encounter Miko, she would need to be alive through the end of the Six Dynasties period already. However, since ZUN adapted much of the tale of Qing’e directly, like her forerunner she idolizes He Xiangnu, who according to legends about her was only born in the Tang period, and attained the status of an immortal in the early eighth century, during the reign of emperor Zhongzong - nearly a century after Miko’s semi-historical counterpart passed away. I do not think this mistake is meaningful. Save for the references to He Xiangnu and imperial examinations, the tale of Qing’e is set in a largely timeless world. I would presume it’s just a small mistake on ZUN’s part, and he didn’t check the chronology while summarizing the part of the story he wanted to use in Seiga’s bio. There is no need to ponder if Seiga’s power lets her travel in time, as the wiki (which, as we all know, prides itself in maintaining “neutrality” and enforcing correct exegesis of the source material, especially Hisami’s bio) does.

There is a further aspect of Seiga’s character which might evoke works about immortals, though I am not sure if this was intentional. As we learn from her entry in Symposium of Post-Mysticism, she “cannot become a celestial due to her personality, but that does not seem to bother her”. The term dixian which I already brought up before designated immortals who were not interested in ascension to heaven. According to Ge Hong, there were actually many benefits to such a fate, and while nominally a dixian ranked below a tianxian (in Touhou terms, a celestial), they had much more freedom. He states that the archetypal immortal Peng Zu, who spent over 800 years on earth, did so because the upper echelons of the heavenly hierarchy are occupied by well established deities, and any immortal joining their ranks would be burdened with tiresome tasks and obliged to act as servants, making their life less enjoyable than it would be on earth.

Peng Zu (wikimedia commons)

Poetry describing the earthbound immortals originally developed in the third and fourth centuries. Parallels can be drawn between their protagonists who reject the celestial bureaucracy with a different class of literary characters popular at the same period - non-conformist recluses who did not care about the mundane, earthly administration. The dixian is essentially a merge between the classical supernatural immortal and the archetypal hermit. This sort of immortality was a metaphor for unrestrained freedom first and foremost.

I will stress again that I have doubts about whether ZUN was aware of this when he came up with Seiga, but it certainly does fit her well. Also, more recently, in Who’s Who of Humans and Yokai in Gensokyo he actually says that “she may be the most hermit-ish character here”. I’d hazard that even if he was not aware of this idea before, he probably is now, in some capacity at least. It’s not like Seiga’s status as a “wicked hermit” was ever tied to lack of interest in heaven, as opposed to necromancy, so this does not contradict anything established.

Reception of Chinese tales about immortals in Japan

Obviously, ZUN is not the first person in Japan to adapt literature about immortals.Something that needs to be stressed before delving deeper into the topic is that transfer of beliefs, and especially tales, pertaining to immortals to Japan did not constitute the spread of Taoism as an organized religion. It is instead simply an aspect of the widespread adoption of elements of Chinese culture. While Taoist ideas were an aspect of this phenomenon, we know relatively little about how they were transmitted to Japan, though there was clearly no effort to introduce the religion itself in a formal manner the way Buddhism was. This topic ultimately can’t be explored here in detail due to space constraints. but most likely what occurred was gradual introduction of certain elements in informal contexts: through art, Buddhist borrowings or poorly documented individual ventures.

The earliest recorded example of reception of motifs related to immortals in Japan is likely the tale of Tajimamori from the Nihon Shoki, which involves a quest for items granting immortality. The much better known tale of Urashima Taro, also preserved in this source, is another candidate, and as a matter of fact was recognized as an example of literature about immortals in the Heian period already.

Ōe no Masafusa (wikimedia commons)

However, our main source of the early Japanese perception of immortals are not the early “national chronicles”, but rather Honchō Shinsenden (本朝神仙伝). Its author was Ōe no Masafusa (1041-1111), an official and scholar from the Heian period. His career culminated when he was appointed to the prestigious position of the governor of Kyushu, though he eventually abdicated to dedicate himself to writing. His work is classified as an example of setsuwa. At the same time it is also firmly tied to the already discussed tradition of Chinese secular immortal literature, and can effectively be considered an attempt at creating a Japanese equivalent of collections of biographies of immortals. Obviously it has its own unique peculiarities to offer too.

Masafusa’s work presents an interesting case of fusion of the Taoist-influenced Chinese notion of immortality with Buddhist ideas: the immortals are compared to hijiri (Buddhist “holy men”) and “living Buddhas” (ikibotoke). This is not entirely a novelty, as while Buddhists are absent from Chinese compilations of biographies of immortals, Laozi’s ascent to immortality was nonetheless at times described in similar terms as Buddhist Nirvana, at least in sources from the fifth century. There was also a preexisting Buddhist tradition of legendary long-lived patriarchs awaiting the coming of Maitreya or simply extending their lifespans to save more beings. Therefore, while innovative, this combination of Taoist and Buddhist elements was hardly something unparalleled or contradictory.

The selection of figures described as immortals in Honchō Shinsenden is also a bit different than in its Chinese forerunners. Legendary heroes and historical statesmen do show up, as expected. However, alchemists and members of Taoist clergy are missing, since they were not exactly common in Japan. Buddhist monks effectively replace them as the main social group among immortals, though it does not seem religious devotion is the deciding factor. Ultimately there is no clear pattern, not even that of virtuous life: Masafusa’s immortals as a group are not meant to be moral examples, even though some of them are portrayed as paragons of virtue.

It seems ultimately what Masafusa wanted to do is present stories he personally found interesting or awe-inspiring, and there was no religious aim behind his work. Some of his choices were actually criticized as inappropriate by his contemporaries, in particular the inclusions of Zenchū and Zensan, who according to polemics were not immortals, but merely devout Buddhists taken into a Pure Land (a heavenly realm created by and inhabited by a Buddha) in their current forms, without reincarnation. This argument follows the well established aspect of esoteric Buddhist doctrine, which enabled the possibility of achieving enlightenment in one’s current incarnation.

A total of thirty seven tales formed the original manuscript, though not all of them survive. They range from long, grandiose narratives about figures like Yamato Takeru and En no Gyoja to brief, almost comedic accounts of the tribulations of anonymous figures such as the “stick-beaten immortal” (who learned how to levitate, but only up to the height of one shaku, which meant that he could not even escape children hitting him with sticks) or the “old seller of white chopsticks” (whose title tells you a lot about his economic situation). Only two are ultimately important here, though: those of the semi-historical prince Shotoku, and the firmly historical poet, historian and eccentric Miyako no Yoshika.

Simply put, I believe Honchō Shinsenden is responsible both for the portrayal of Shotoku as a Taoist immortal and for the inclusion of a character (vaguely) based on Miyako no Yoshika in Ten Desires.

Honchō Shinsenden’s Shotoku and Toyosatomimi no Miko

The image of prince Shotoku through the ages

Prince Shotoku (聖徳太子) is one of the highest profile figures to ever be portrayed in Touhou, and as such arguably requires no lengthy introduction. He purportedly lived from February 7, 574 to April 8, 622, and served as a regent on behalf of his aunt, empress Suiko. He is traditionally credited with spreading Buddhism in Japan, ordaining numerous monks, writing commentaries on sutras, vanquishing rivals such as Mononobe no Moriya with the help of the Soga clan, and so on. He might have not existed at all, or perhaps he did, but played nowhere near as major of a role in Japanese history as traditionally assumed. The academic debate started a few decades ago, and remains ongoing. Its outcome isn’t really important here, since regardless of Shotoku’s disputed historicity, he came to be well established both as a religious figure and as a literary character. At various points in time and for various people, Shotoku was, in no particular order, the ideal statesman, a manifestation of Kannon, a peerless military commander, a yaoi protagonist and, most importantly, an immortal.

In Honchō Shinsenden, Shotoku is referred to as “prince Jōgu” (上宮), though we do get the mandatory Shotoku namedrop indirectly when his virtue (聖徳) is highlighted.. He is actually one of the two only of the listed immortals who can be classified at least vaguely as “statesmen”, the other being Yamato Takeru. For unknown reasons, Masafusa got some details wrong: according to him Shotoku’s father was Bidatsu. This view is unparalleled, and there is no real reason to doubt the conventional genealogy, which firmly positions him as a son of Yomei and his half-sister Anahobe no Hashihito. We learn that his birth was foretold by a dream in which his mother saw a golden figure who entrusted her with a child who will spread the dharma. This is in itself a combination of Taoist and Buddhist elements, seemingly an attempt at imitating a legend about the birth of Laozi, which in turn depended on a legend about the birth of the historical Buddha.

Naturally, Shotoku already displayed supernatural abilities as a child. Masafusa reports that whoever touched him was imbued with a “lasting fragrance”. A variant of the well known tale which his Touhou counterpart’s name and ability reference is presented here too, though a key detail differs - Shotoku can listen to eight, rather than ten, people according to Masafusa. This is not unparalleled, and therefore probably isn’t a mistake unlike the unexpected genealogical change mentioned before.

A major event from Shotoku’s life relayed by Honchō Shinsenden is an alleged meeting between him and Illa (Nichira), a Korean monk living in Japan. The historicity of this episode is debatable, as Illa died when Shotoku (if he was real in the first place, of course) was only eleven years old. He identifies the prince as the bodhisattva Kannon, and pays respect to him as such. In response Shotoku emitted a beam of light from between his eyebrows, which reflects both Taoist and Buddhist traditions about manifesting supernatural powers.

Illa's alter ego Atago Gongen (wikimedia commons)

Interestingly, Illa responds by doing the same, thus revealing his own supernatural character. We know from other sources that Illa could be identified as the true identity of Atago Gongen, the tengu-like deity of Mount Atago. Bernard Faure notes parallels can be drawn between his portrayals as a foreign supernatural ally of Shotoku and as the human alter ego of a deity with the traditions pertaining to Hata no Kawakatsu. There is also an “immortal of Mount Atago” in Honchō Shinsenden, but his identity is left unspecified. It's worth noting that in Symposium of Post-Mysticism Byakuren and Marisa at one point discuss the existence of “hermit-like tengu”. Illa truthers… we can make it happen if we believe strong enough… Jokes aside, I’m actually cautiously optimistic that Illa might some day end up being the first Korean character in Touhou, at least implicitly. Given the inclusion of references to Hata no Kawakatsu, odds are decent ZUN knows about him too.

In another anecdote, we are introduced to another member of Shotoku’s supernatural supporting cast, the black steed of Kai. This horse is credited with being able to travel the distance of a thousand ri in a single move. This is seemingly an adaptation of a Taoist motif too, as immortals were believed to favor traveling on supernaturally fast steeds, or in cloud chariots drawn by such animals, or to move instantaneously through other means. The fabulous distance of 1000 (or even 10000) ri is conventional, too.

Shotoku traveling through the sky on his supernatural horse (Smithsonian Institution; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Of course, the black steed (kurokoma) is also the very same horse that served as the basis for Saki. While allusions to this connection is probably the second most common genre of fanart of her, it surprisingly took ZUN four whole years to acknowledge it outside of a track title, specifically through two lines in the vs mode of Unlimited Dream of All Living Ghost. Time will tell if anything will come out of it, I’m personally skeptical seeing as we have yet to see a canon work do anything with the connection between Okina and Hata no Kawakatsu even though it was acknowledged in an interview. I hope I am wrong, though.

Shotoku’s various accomplishments are not described in detail, though Masafusa does bring up his famous seventeen articles constitution and the establishment of Shitenno-ji, and additionally states that teachings linked to the Yuezhi people from Central Asia were associated with it (unique opportunity to justify bringing Central Asian deities like Nana and Weshparkar into Touhou).

The final and most important part of Shotoku’s biography, the circumstances of his death - or rather his acquisition of immortality - is only partially preserved. According to Masafusa, one day he simply informed his wife (presumably Kawashide no Iratsume, as opposed to one of the other three wives) that he cannot exist anymore in a “defiled” world and “transformed” himself. It is actually not explained how he even mastered the techniques allowing that, presumably because we are meant to attribute this miraculous feat to his status as a saintly Buddhist. The authors behind the most recent English translation, Christoph Kleine and Livia Kohn, suggest that in the lost final sentence(s) Masafusa might have combined the Taoist take on immortality with Amida’s pure land, but this is ultimately speculative.

ZUN actually went for something closer to the Chinese model with Miko - she was explicitly taught by Seiga. The notion of immortals mentoring those they deem worthy to pursue the same path is a widespread motif, and even some of the Eight Immortals gained their status this way. This idea is absent altogether from Honchō Shinsenden, perhaps since it was tied to formal transfer of Taoist teachings. While this is an innovation, I would argue it’s still true to Shotoku legends, considering they are already filled with miracle-working visitors from distant lands, from Illa and Hata no Kawakatsu to considerably more famous Bodhidharma.

From eccentric to immortal: the literary afterlife of Miyako no Yoshika

Miyako no Yoshika (wikimedia commons)

As I already said, the second tale from Honchō Shinsenden relevant to Ten Desires is that focused on Miyako no Yoshika. He obviously shares no direct connection with prince Shotoku. Or with Qing’e, for that matter. Unlike prince Shotoku, he left a solid paper trail behind, and there’s no doubt that despite having quite a career as a legendary figure, he was originally a historical person. He lived from 834 to 879, in the Heian period. He was a calligrapher, a poet, an imperial official and for a brief time even an assistant to the envoy to Bohai (Balhae). The inclusion of a character based on him in Ten Desires might seem puzzling at first glance, since none of this seems particularly relevant to the game, and Yoshika’s omake bio doesn’t say much that helps here, beyond calling her a “corpse from ancient Japan”. However, I believe Honchō Shinsenden sheds some light on this mystery.

In Honchō Shinsenden, Miyako no Yoshika belongs to the small category of literati pursuing immortality, a status he only shares with Tachibana no Masamichi. There are a number of other immortals listed who are neither monks nor statesmen, and can be broadly classified as laypeople, though none of them seem to have much to do with those two. In contrast with figures like prince Shotoku, described as pious sages, the fictionalized take on Yoshika is meant to highlight extreme eccentricity instead. This is an element common in accounts of Chinese immortals’ lives too, as I highlighted before. You might also remember this topic from the Zanmu article from last month.

As we learn, Yoshika, who was originally known as Kuwahara (misread by Masafusa as Haraaka, an actually unattested surname) no Kotomichi but changed first his family name (for unknown reasons) and then also his given name because of a poem he liked, decided to become an immortal under rather unusual circumstances. In the very beginning of his career, after spending a night with the concubine of an official from the Bureau of Examination who was meant to examine him the next day, Yoshika decided that his goal in life should be to become an “eccentric immortal”. He passed his official exam without any trouble, with an unparalleled score. Graffiti in the academy he attended proclaimed him the “world’s greatest maniac” (so he comes prepackaged with a Touhou-appropriate title). He attained widespread acclaim for his wit and poetic skill. In his free time, he engages in celebrated literati pastimes such as drinking and sleeping with courtesans (Masafusa does not specify if he wrote about that, like his Tang counterparts did).

Sugawara no Michizane, Yoshika's apparent nemesis (wikimedia commons)

Alas, Yoshika’s career ultimately did not go entirely according to his whims. The beginning of the end was the day when he acted as the examiner of a new rising star, Sugawa no Michizane. The latter has proven himself to be even more skilled than him, and eventually rose to a higher rank than Yoshika. The latter could not bear this perceived offense against him and one day left his life behind to return to the pursuit of immortality. He aimed at the mountains, hoping to find immortals there to learn their techniques. Masafusa does not provide much detail about his further life, but states that after many journeys he evidently accomplished his goal, as he was purportedly seen alive and well a century after his alleged death.

It’s worth pointing out here that this course of events follows a Taoist motif: becoming disillusioned with one's own career, or with earthly affairs in general, is a common catalyst for search of the Taoist way in literature. A point can actually be made that of all the immortals in the Honchō Shinsenden is the most quintessentially Taoist one (despite not actually being a Taoist), the most direct example of the Chinese model being adapted for a Japanese historical figure, with no addition of the Buddhist components. He even resembles the typical image of a Tang scholar-bureaucrat invested in search for immortality just as much as in amorous adventures. This arguably makes him the perfect basis for a character in a game centered on Taoist immortals in Japan, though truth to be told I feel that in contrast with Seiga and Miko, ZUN’s Yoshika does not live up to her forerunner.

Legends about Miyako no Yoshika in other sources, or the remarkable poetic career of Ibaraki-doji

The oni of Rashomon and Miyako no Yoshika, as depicted by Ginko Adachi (Yokohama Art Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Some of you might wonder where Ibaraki-doji fits into this, considering the pretty direct reference to Yoshika's poetry in Wild and Horned Hermit. Masafusa, as a matter of fact, does allude to one more legend while highlighting Yoshika’s poetic talent, though he doesn’t go into detail. There’s no direct supernatural encounter - a nameless demonic inhabitant of Kyoto’s gate only hears a poem from passersby marveling at it and becomes “deeply moved”, but that’s it. The name Ibaraki-doji doesn’t show up at all, and there’s no mention of the oni finishing the poem, which is a mainstay of later versions.

Another of Masafusa’s works, Gōdansho (江談抄), also doesn’t use the name Ibaraki-dōji, or mention an actual encounter between Yoshika and the oni - he merely hears an unnamed passerby hum the poem and comments on it, calling it touching. However, the Kamakura period collection Jikkinshō already presents the version which gained the most traction in the long run, with the poem being a collaboration between Miyako no Yoshika and an oni. He later recites the full composition to Sugawara no Michizane, who is correctly able to point out only some of it is Yoshika’s own work, while the rest was added by an oni. However, once again, the name Ibaraki-doji is nowhere to be found.

On the other hand, while the story of Ibaraki-doji can be found in Taiheiki and other similar sources, it takes place far away from the capital in these early versions. The location was changed in noh adaptations of the legend to Rashomon, presumably due to its preexisting associations with supernatural creatures. By the time Toriyama Sekien published one if his famous bestiaries, Konjaku Hyakki Shūi, it seems the idea that the oni inhabiting this gate who was encountered by Yoshika and Watanabe no Tsuna’s nemesis Ibaraki-doji, who fought him there, were one and the same was already well established. Note that Sekien’s description of the oni of Rashomon actually doesn’t use the name Ibaraki-doji, though we do know he was aware of it.

It’s worth noting that the oni of Rashomon seemingly had a broader interest in fine arts, since there is also a legend in which he meets the famous biwa player Minamoto no Hiromasa and shows him his own skills with this instrument. However, this is ultimately not directly relevant to Yoshika, so you will have to wait until the next article, which will cover Shuten-doji and Ibaraki-doji in detail, to learn more.

The oni of Rashomon, as depicted by Toriyama Sekien (wikimedia commons)

Bibliography

Bernard Faure, From Bodhidharma to Daruma : The Hidden Life of a Zen Patriarch

Xiaofei Kang, The Cult of the Fox: Power, Gender, and Popular Religion in Late Imperial and Modern China

Zornica Kirkova, Roaming into the Beyond: Representations of Xian Immortality in Early Medieval Chinese Verse

Christoph Kleine & Livia Kohn, Daoist Immortality and Buddhist Holiness: A Study and Translation of the Honchō shinsen-den

Michelle Osterfeld Li, Ambiguous Bodies. Reading the Grotesque in Japanese Setsuwa Tales

Masato Mori, "Konjaku Monogatari-shū": Supernatural Creatures and Order

Masuo Shin'ichirō, Daoism in Japan (published in Brill’s Daoism Handbook)

Leslie Wallace, Betwixt and Between: Depictions of Immortals in Eastern Han Dynasty Tomb Reliefs

287 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yoshika Miyako and Seiga Kaku from Touhou Project

please excuse the atrocious anatomy, this took me a long time to finish

#doki doki waku waku#i have been working on this since october#my art#digital art#digital fanart#fanart#touhou#touhou fanart#touhou project#2hu#yoshika miyako#seiga kaku#seiyoshi

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doodles ⭐

#touhou#touhou fanart#touhou project#digital art#my art#art#ms paint#chiyari tenkajin#yoshika miyako#minoriko aki#utsuho reiuji

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

unholy 6am foreshortening study

#i didnt even spell seiga right#seiga kaku#yoshika miyako#traditional#my art#doodle#cicisillyposting#touhou#touhou fanart

253 notes

·

View notes

Text

Desert Years

#touhou#seiga kaku#yoshika miyako#oooo you wanna go listen to retro future girls by shibayanrecords ooo

302 notes

·

View notes

Text

Halloween ko-fi requests open!

Y'all know the drill at this point - $30 or more nets you a drawing like this one. Feel free to suggest a specific Halloween costume for the character of else let me come up with one on my own!

My ko-fi: https://ko-fi.com/udomyon

#darkstalkers#Capcom#vampire savior#hsien ko#Hsien-ko#lei lei#Touhou#yoshika miyako#Halloween costume#ko fi#requests open#artists on tumblr

173 notes

·

View notes