#with some ugly commentaries and actions on her part. like its your (supposed) best friend's birthday at least try to hide your disgust 👍

Text

i have a headache but also i dont want to go to sleep just yet dkjnfjds i want me-time

(warning: as i was writing the tags of this post this turned into another kinda-heavy rant about the situation my group of friends and i are. so keep that in mind)

#things were weird today when She(tm) was there but when she left things were normal again#but these hours were kinda stressful rip or more like... there was an inherent discomfort and tension in the air#with some ugly commentaries and actions on her part. like its your (supposed) best friend's birthday at least try to hide your disgust 👍#birthday you ~apparently~ forgot until it the day before. also you didnt had a single penny to spend on the gift for him#but you sure as hell had it to go eat with your college friends to expensive places! girl at least dont post about it on insta#and just in case; this wasnt a '*goes to expensive places before* -oh i dont have money sowwy :(('#this was a '-oh i dont have money sowwy :(( *goes to expensive places after it*'#what we were asking for collaboration was way less than what she spent on those places. it was AT THE VERY LEAST 3000 ars per food#and you know what she wanted to give for the gift? 500 ars!!! you cant buy shit with it; let alone if we only collaborated with 500 each#like she wanted. we're 4; genuine question what kinda shit can you buy for $2000. maybe a good quality cup but we already gave him that#but even then the point is not the money; the thing is the attitude. you cant spend more than $500 on us#but you can spend at least $6000 on your other friends; given you went to eat with them two days in a row. priorities i guess?#OH! and talking about it!! can you fucking believe she INVESTIGATED the phone of our ~new~ friend (the one shes jealous of)#and DEADASS said 'oh i see. my mom has an A51'. our friend has an A20 if im not wrong; which might not be an A51 but its. still expensive??#also your mom has an A51 but you have an iPhone 5 since you were on high school. but hey; apple i am right?? inherently better than an A20#sorry i have less than that; i have an A10s (that i got on the start of 2020). can i still breathe the same air as you and your mom /s#once again the problem is not the money or the phone or WHATEVER. its the fucking attitude shes having. you want to pretend you have money#and act like youre superior to people who 'dont'; when in reality YOU ARE MIDDLE CLASS. YOU ARENT UPPER CLASS; NOT EVEN UPPER-MIDDLE CLASS#YOURE MIDDLE CLASS. MIDDLE CLASS LIKE THE REST OF US; NOT LIKE YOUR COLLEGE FRIENDS YOU LOVE SO MUCH AND WANT TO IMPRESS#YOU SPEND MONEY YOU DEFINITELY DONT HAVE BECAUSE YOU WANT TO APPEAR UPPER-MIDDLE AT THE VERY LEAST. but thats a lie#a lie that if these beloved friends bothered to ACTUALLY know even the slightest about you; like we do; would fall apart. but they wouldnt!#because they dont care about you as much as we care(d). do you think they will tolerate this fucking attitude youre having towards us?#no they wouldnt. trust me; they WOULDNT. they will tell you to fuck off and leave you completely alone. go cry a river.#god fucking dammit why are you like this. WHY you turned like this. or rather; why we were SO GODDAMN blind we didnt noticed this before#negative

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Death of Aeris

Before Aeris died, I'd never really experienced anything in media that, in retrospect, actually felt like a death feels.

I was in seventh grade when Final Fantasy VII came out. I'm not sure if people my age still talk about how it felt to play Final Fantasy VII in 1997 (I imagine there's probably a cottage industry of retrospectives, but I haven't looked). But at my school, at least, nothing compared to it in terms of its unique form of media reception until maybe the advent of season-length binge-watching. It's a mode in which everyone follows along at their own pace across a long-form media object over days and weeks, checking in to see how far ahead or behind they are from their friends, taunting when ahead, despairing when too far behind.

I imagine some book crazes are like this, but I never really experienced any of them firsthand. And certainly I can't think of any non-print media with that kind of long-term conversational oomph -- the subject of intense debate for weeks and even months -- that is at the same time very careful and tentative with some thoughtfulness put into other people's progress. We had the so-called "water cooler" shows that everyone was expected to have seen last night, but the sussing out of where everyone was a week or a month into gameplay was much different. It created a throughline of reporting and speculation that felt a bit more like gossip, or some shared conspiracy whose web was still hidden in its entirety.

I bring up that context because a few elements in how I reacted to Aeris's death, about a third of the way or so through Final Fantasy VII, might have been impossible had they not happened at that time and in that way. Perhaps the most important element in that regard was simply that I heard whisperings of that sort of event being possible, without experiencing the kind of full-on spoiler that is now a ubiquitous landmine in trying to figure out what different media are "about" without ruining the surprises.

Instead there was a sense of unease, an occasionally remarked upon twist that was coming up, and lots of conversation about whether one could tell it was coming or not, an almost vindictive knowingness from those who already experienced it -- "oh, you'll see." Because this conversation was only among my friends, it didn't take on the feeling being a microcosm of a fandom. We didn't really know anything about fandoms, not being particularly savvy online (in 7th grade I mostly trolled strangers in chat rooms and then giddily ran away, like a prank call, before looking up recipes for banana pancakes).

So the environment was not exactly like ruining a plot twist in a movie; it was more a sense that something was coming, maybe tonight, maybe the next night, maybe next week, and that when it happened, you'd know, and you'd never really see it coming, unless maybe you did (there were a few claims from friends further along in the game that they saw it coming, a claim I find hard to believe). And it would change everything.

It's that contemporaneous commentary on the ongoing action while also being inscrutably aware of something far off in the future that I think is very difficult to replicate now. There's too much information everywhere, too many ways to cut off or clarify that odd game of telephone that non-internet-based media fandom lent itself to in an era with lots of media in it but few ways to reliably learn about it without some prior knowledge. A bit like how other media -- horror movies, The Wire -- had to transform in the mid-2000's when the ubiquity of cell phone communication dried up older storytelling tropes that built suspense through patchy connections.

Because I was so persistently, if only mildly, ill at ease in the first half of the game, and because I had such a strong sense that something bad would happen, the cut scene in which Aeris is finally murdered had the kind of protracted, crystallized impact of a trauma, a sense that you're seeing something that was fated to happen and will always recur (in memory), and that, at this very moment, your brain is encoding a loop that will keep its jagged little hooks in you forever. I see Aeris in a pink dress, bent, seemingly in prayer, maybe a slight smile, and I see her being run through. I see my dad, defeated, on the side of the bed, and my sister is crying before he even has to say anything. (How did he put it?)

YouTube breaks my memory's imperfect telephone-game chain, and I see, watching the clip again for the first time in what must be a dozen or more years, that the animation itself is not nearly as crisp or as subtle as it is in my memory; the characters are chunky, polygonal, little better than the little moving sausages in the normal gameplay by today's CGI standards. In my mind, Aeris is remarkably well-rendered, the scene -- the slicing -- more grisly. But I'm also surprised at how much fidelity parts of the scene have retained, the blocking of the characters, the ambiguous facial expressions, the stillness of it.

I was wild with questions after Aeris died, or, more accurately, with a demand for answers. I remember finally going to a text walk-through I'd avoided to see if there was any way to have prevented this outcome. If there was any glitch to make Aeris come back into the party, a zombie compromise. Not that I could tell. She was just gone from the game, and with so much left to finish.

I was a completist -- if there was some marginal character that one might conceivably miss (Yuffie, say), I would beat the game again just to have the satisfaction of having the full set, as it were. So there was the basic functional disappointment of having an eternally unfinished collection. I don't want to underplay this feeling -- for god's sake, it was just a video game.

But I'm returning to it now because Aeris's death had a subtle psychological impact on my sense of what Final Fantasy VII actually was, in a way that makes me remember it so fondly and so sadly, and with remarkable frequency given I'm a good decade past a point where I've even more than glanced at a video game. Final Fantasy VII was different -- it wasn't just a game where you do everything you're supposed to do and finish it, maybe cheating a little along the way, maybe not. It's a game with an ugly little hole in its center, and you muddle through as best you can, knowing that it will never and can never be truly "won," and hence can never really be over. Not all the way. You finish as much as you can finish; there's a scar.

Even my own behaviors with Final Fantasy VII after beating the game once have echoes in my experience with the actual ugly little holes that I imagine most of us build our lives around. I vividly remember finishing Final Fantasy VII on a subsequent attempt after unlocking Aeris's final limit break -- the special, "final" move that can only be accessed after many more hours of gameplay than Aeris is realistically given, unless for whatever reason you are obsessed enough to do it anyway. The upshot was days and maybe weeks of sitting in my parents' basement, drinking diet soda, running around some remote little forest or peninsula, killing monsters in a mind-numbing sequence of auto-pilot maneuvers to slowly build up Aeris's experience. In my mind the limit break itself was anticlimactic -- but how could it not be? It didn't matter. She had to die.

The key resonance for me in Aeris's death is not just the death itself, its shock or, alternatively, those post-hoc rationalizations that it could be predicted; it is the way that the process of experiencing that death, that way of carrying it with you, forever stains the whole experience, dampens it with futility but somehow inflames a compulsion to retrace the steps anyway. You fight the same monsters, hoping that maybe just once the screen will darken and the skies will open up and something will change.

16 notes

·

View notes

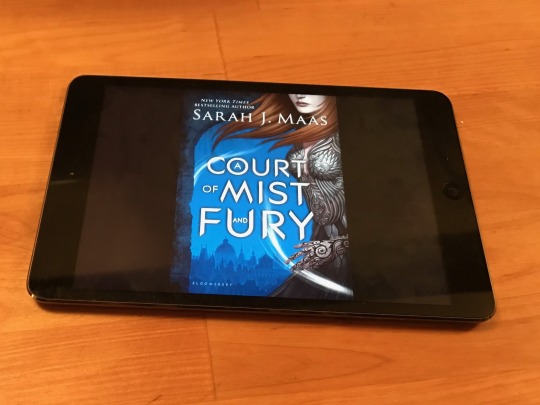

Photo

Look, publishing community. We need to talk.

About ten years ago, you let the Twilight series take over the world, and with it, naive young girls’ belief that overly protective stalker boyfriends were something to strive for. Since the series’ completion, readers and moviegoers alike have vowed to do better. We hoped to put these toxic ideals behind us with every conversation we had about the problematic nature of Stephenie Meyer’s books. We hoped in doing so, we could finally move forward to read and support more wholesome, meaningful content.

Yet somehow, you chose to invest your money in Sarah J. Maas, and unleashed a whole new, far worse beast upon the world.

Why are we still letting toxic romances dominate the YA genre? Have we learned nothing from the likes of Meyer at all?

Let’s take a step back for a moment. As with her first series, Throne of Glass, Sarah J. Maas set out to write another fairy tale retelling in her latest A Court of Thorns and Roses series. By the time Mist and Fury begins, we’ve all but cast the Beauty and the Beast pretence to the wind. In perhaps the most dull first third of any novel, Feyre is suffering extreme depression and PTSD following the trauma incurred at Amarantha’s wrath. I am wholeheartedly here for portrayals of PTSD in YA. In fact, I encourage it. And given how much of a non-entity it is in Throne of Glass following Celaena’s pre-series traumas, this almost seems like an improvement on Maas’ part. But not when it goes on and on and on for 200 pages. Reading about any protagonist moping in self-pity is a 50-page deal at most. I get we’re supposed to see Feyre’s lack of self-worth at the start of this novel. I get that her trajectory is clearly one of her realising her value and gaining empowerment. Fine. But you can tell that story in 150 less pages. Believe me, as someone who has opened a novel with significant scenes of abuse and trauma, I know what it means to cut back. It pays to trust your reader and rein it in sometimes.

Which comes to one of the most blatant transgressions Maas commits: her lack of editing. Sure, at this point, she’s kind of well-known for her signature long sequels. But larger word counts do not good writing make. This novel could have easily been a solid 400 pages without the faffing about she does in the beginning.

There are some books that really excel in being split into distinct acts. Separating segments via setting or plot shifts can really solidify the narrative, but Maas’ acts can be separated out according to isolated moments sliding along a scale of boring, great, horrifying, and dire. Which is not what you want out of a narrative arc.

I actually thoroughly enjoyed the middle of this novel. For 200 pages, it seems like Maas has begun to atone for all her grievous harm done in her previous works. She introduces some interesting female characters for Feyre to befriend. The friend dynamic of Rhysand’s council is easily one of the strengths of the series and I wish she could have introduced them by the end of the first book. Amren in particular is a fascinating character, who, for a hot second, seems like she might kick some ass in a dark, ruthless, gory kind of way. She and Feyre have a great scene where they’re given permission to go out on a mission and be badass. I was excited to see where this would go and I looked forward to seeing these new battle sisters doing some serious damage together. Unfortunately, there are once more, long interludes where Amren keeps herself locked up, decoding things while the others go out and do the exciting stuff. Until the climax of the novel, the best, most dynamic addition to the cast has been shafted. As are all of the female characters in this series.

Here’s the thing.

For the most part, I like the girls in this book. At face value, they’re great. Nesta, Amren, Mor, and Feyre could all hold their own in battle as easily as they could all have a slumber-party style ki-ki over wine together. But the patriarchal world they’re placed in does no favours for them. Maas’ faerie world is build up by patriarchal traditions, where the men are led by their territorial, violent animal instincts:

“What’s normal?” I said.

… “The … frenzy … When a couple accepts the mating bond, it’s … overwhelming. Again, harkening back to the beasts we once were. Probably something about ensuring the female is impregnated. … Some couples don’t leave the house for a week. Males get so volatile that it can be dangerous for them to be in public, anyway. I’ve seen males of reason and education shatter a room because another male looked too long in their mate’s direction too soon after they’ve been mated.”

This hyper-masculine tradition also happens to heavily feature treating women like commodities they can use and throw away whenever they like. Rhysand, a character Maas tries so hard to pass off as a celebrated feminist, even tells Feyre in the heat of passion that, “I want you splayed out on the table like my own personal feast”. Every single one of Maas’ male characters, including, and especially Rhys, is a product of this tradition. But instead of engaging with commentary about how toxic such a worldview is, Maas just lets her characters carry on in this reality without consequence, self-awareness, or rebellion against it, as can be seen by Rhys’ explanation of women’s place in the kitchen, and Feyre’s subsequent acquiescence to that role as Rhys' partner:

“It’s an … important moment when a female offers her mate food. It goes back to whatever beasts we were a long, long time ago. But it still matters. The first time matters. Some mated pairs will make an occasion of it– throwing a party just so the female can formally offer her mate food … But it means that the female … accepts the bond.”

This old-fashioned, dare I say, archaic misogynistic ideal is just treated as the norm, effectively cementing every other male fantasy writer’s depiction of patriarchal societies as the ultimate world-building feature of the genre.

I don’t know what Maas is thinking, but whatever it is, it’s not cute.

Why are we still putting fantasies set in patriarchal worlds on such a high pedestal? It’s fantasy! What’s more, it’s 2017! You can’t tell me it’s more realistic to write a patriarchal society than literally any other kind in a fantasy world. When Maas, a woman writer creating her own world from scratch, has the chance to do whatever she wants, this is what she gives us?

One of the most horrifying scenes in A Court of Thorns and Roses (which is also shockingly overlooked) is Rhysand drugging Feyre and turning her into his slave whore without her consent. Maas sweeps this under the rug with a quick explanation that is all justified to a.) save Rhys’ fearsome reputation among the other realms, and b.) protect Feyre from the horrors of Amarantha’s kingdom. Just when I thought this particular plot was given its much needed closure (shut it down, Sarah. Shut it down right now!), the slave whore plot rears its ugly head again:

“I had heard the rumours, and I didn’t quite believe him.” [Keir’s] gaze settled on me, on my breasts, peaked through the folds of my dress, of my legs, spread wider than they’d been minutes before, and Rhys’ hand in dangerous territory. “But it seems true: Tamlin’s pet is now owned by another master.”

“You should see how I make her beg,” Rhys murmured, nudging my neck with his nose.

Keir clasped his hands behind his back. “I assume you brought her to make a statement.”

“You know everything I do is a statement.”

The only difference is, Feyre’s aware and consenting this time. Still, the skimpy dress and incredibly graphic touching on Rhys’ part all in the name of creating a diversion isn’t good enough to justify his actions. Rhysand’s created a thinly-veiled excuse to once again, objectify Feyre, touch her inappropriately in front of everyone, and lay claim to her when she’s not his to claim:

“Try not to let it go to your head.”

…I … said with midnight smoothness, “What?”

Rhys’ breath caressed my ear, the twin to the breath he’d brushed against it merely an hour ago in the skies. “That every male in here is contemplating what they’d be willing to give up in order to get that pretty, red mouth of yours on them.”

…His hand slid higher up my thigh, the proprietary touch of a male who knew he owned someone body and soul.

His eyes on the Steward, Rhys made vague nods every now and then. While his fingers continued their slow, steady stroking on my thighs, rising higher with every pass.

People were watching. Even as they drank and ate, even as some danced in small circles, people were watching. I was sitting in his lap, his own personal plaything, his every touch visible to them.

This isn’t romantic, this isn’t sexy, and it’s straight up not okay!

At what point did this series just turn into a horrific Princes Leia/Jabba the Hut smutfic? I know the only ones imagining what it might’ve been like had Leia been chained to Sexy McSexMachine instead of a giant blob are usually the pervy weirdos. Meaning no one in their right minds would want that mental image. Absolutely no one. In fact, the moment that image popped into my head, the final implosion of Rhys and Feyre’s sexual tension was made all the more cringe-worthy. There’s a reason Carrie Fisher spoke so strongly against Jabba and the gold bikini. She knew what it meant to be objectified, something Maas does not succeed in exploiting with Rhys’ choice to put Feyre in these skimpy outfits not once, but twice in this series. While yes, putting her in these outfits is ultimately a con-game, why should he be lauded for still playing by patriarchal rules in the first place? Shouldn’t the correct course of action be to break down those gender barriers?

All I have left to say about that is, I’m sorry, Sarah. You wrote that Leia/Jabba fanfiction. You made your bed. Now lie in it.

I suppose it’s about time to address the elephant in the room: Rhys. Oh boy… I don’t know how someone can pull together a character’s development so offensively, but Maas somehow wins the prize. He spends the entire first book as a lackey to the villain, doing the best he can to humiliate and emotionally manipulate Feyre. Now, we’re expected to believe he’s not only Feyre’s true love (oh, sorry… mate), but a feminist icon? I’m sorry. No. Did we already forget that he drugged her and made her dance for him in Leia’s gold bikini? It happened. I’m not about to let people forget it…

Readers fall all over themselves over him for coming to Feyre’s rescue when she begs to be saved from her wedding to Tamlin. On the surface, he’s set up to directly juxtapose Tamlin’s controlling over-protectiveness by letting Feyre do whatever she likes. Yet there’s still an unhealthy amount of Rhys manipulating situations in order to do what he feels is best for her. Not what Feyre thinks is best for herself, but what he thinks is best. Every single decision Feyre makes is based on Rhys’ influence. Nothing she does is for herself. By making Rhysand’s word law, Maas effectively strips Feyre of her agency, ironically, the one thing Rhys has attempted to help her regain in the first place.

What’s more, I don’t know who any of these characters are outside of their relation to Rhysand. They all revolve around him, because in Maas’ paraphrased words, he’s the most beautiful, powerful, strongest male in the kingdom. I honestly don’t need this overcompensation to make up for how toxic he is as a person. Not to mention, his male friends are nothing but carbon copies of him. Cassian and Azriel share his colouring and Ilyrian wings. I’ve seen plenty of fanart out there depicting the full cast of characters and I can never tell one male character from the another, nor one female character from another. The men (Azriel, Cassian, and Rhysand) are handsome and dark haired, the women (Feyre, Nesta, Elain, and Mor), beautiful and blonde. Again, the only stand-out is Amren, who is woefully underrepresented and poorly used in the novel. When you have a white cookie cutter template for every character in your patriarchal world, you’ve gotta step outside your box to deliver some diversity at some point. Otherwise, everything’s just vanilla with a side of racism.

If you think Rhys is the only male character abusing women in this novel, you would be dead wrong. Every single female character in this series has an honestly triggering backstory involving rape, whether emotional or physical. This novel is undoubtedly the sort of thing that should come with a warning. I’ve seen copies with warnings that the series is not suitable for young readers on the back cover, but it’s both irresponsible to then market it as YA, and not discuss rape and abuse responsibly. In fact, given how frequently Maas uses the rape card and how non-existent any discourse concerning the consequences is, I’d say this is a dire case of romanticising rape. And I’m tired of seeing readers obsessing over series like these en masse. It's doing nothing but perpetuating rape culture.

Mor in particular has a brutal rape backstory. This is made all the more upsetting by how eager her father is to sell her off to the highest bidder, and her desperation to lose her virginity on her own terms:

“I wanted Cassian to be the one who did it. I wanted to choose … Rhys came back the next morning, and when he learned what had happened … He and Cassian … I’ve never seen them fight like that. Hopefully I never will again.I know Rhys wasn’t pissed about my virginity, but rather the danger that losing it had put me in. Azriel was even angrier about it–though he let Rhys do the walloping. They knew what my family would do for debasing myself.”

“I wanted my first time to be with one of the legendary Illyrian warriors. I wanted to lie with the greatest of Illyrian warriors, actually. And I’d taken one look at Cassian and known. … He just wants what he can’t have, and it’s irritated him for centuries that I walked away and never looked back.”

“Oh, it drives him insane,” Rhys said from behind me.

What’s worrying here is that while the men are praised for playing the patriarchal system to protect their women, female characters like Mor aren’t shown the same respect for protecting themselves. Mor’s entire character arc is punishment for her female sexuality, kept completely out of her control. Not once does a female character speak out against her sexual abuse, nor do they seek justice for it.

In a recent interview, Maas has stated that she only writes sex scenes if they further the plot. When literally everyone’s backstory hinges on sex, whether consensual or otherwise, I find that doubtful. If there’s one positive thing i’ll say about Maas, it’s that i’m glad she’s leading the charge for sex-positive female characters. But empowering are these characters really, when they’re defined by their desirability to men and their past sexual traumas? Sure, Feyre has sexual agency, but what else does she have? Especially in a patriarchal world where this is expected of her, and she doesn’t even use this “power” to her advantage…

Look, I’m glad Feyre’s getting pleasured the way she wants it, when she wants it, and the detailed depiction of her sexual stimulation might help girls become more aware of their own bodies and sexuality. But when this is the highest profile series featuring female sexuality in the YA market right now, what kind of example are we really setting here?

Feminism doesn’t begin and end with sexual expression. It’s more than that and Maas’ characters have to join that fight. Especially given it’s one of the highest selling fantasy series in the market right now. Sarah J. Maas is not the feminist role model we need for this generation of girls.

We need more than this.

In short, I’m absolutely shocked and appalled that so many people blindly gave this book 4 and 5 stars. Even those who acknowledge how problematic Maas’ writing is. Is it really worth overlooking blatant normalised rape culture to call something your favourite series? As I said from the outset, we’ve already been there with Twilight. An entire generation of girls fell head over heels for Edward Cullen, a 100+ year old stalker who dictated Bella Swan’s ever action and motivation. Now, here we are again, encouraging a new generation of teens to swoon over this sexy, emotionally manipulative product of rape culture, without any acknowledgement of the consequences.

We need to do better. Starting with readers. Starting with authors. Starting with publishers.

It’s time to hold ourselves accountable for the content we praise and allow kids to read. Because toxic masculinity and rape culture are not values to uphold. We live in a world where the President of the United States can brag about grabbing women by the pussy without recourse. Where old, white men are constantly dictating women’s reproductive rights. Where women are catcalled in the streets and victim blamed for the clothes they wear. Where girls can’t even go out at night on their own without the threat of sexual assault.

Is this really what we want to teach our daughters, sisters, students, friends? That it’s okay, to allow passing men to objectify us, just because they have power over us?

Listen, girls. This is the thing: men have power over us so long as we give it to them. So long as we keep laying down and accepting that we’re weak and in need of defending, they’ll keep doing it. And people like Sarah J. Maas will keep holding to those gender expectations. They’ll keep defining romantic ideals based on hyper-masculine overprotective, possessive men.

It’s up to us to redefine romantic ideals. To tear down toxic masculinity and uplift healthy, equal relationships based on mutual respect.

Because you’re worth so much more than that. You deserve better than Rhysand. Align yourself with people who value you for who you are and not just your body. Listen to them when they praise you for your talents. Accept their recommendations when they stumble across media showcasing aspirational women rising above the status quo. You are more than just an object holding a man’s attention. You are yourself and you deserve the world.

Look beyond the smokescreen of Sarah J. Maas’ works and aspire to be something more.

#sarah j. maas#acotar#acomaf#anti-acotar#anti-maas#fantasy#feminism#YA#young adult#toxic masculinity#female sexuality#rape culture

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

INGMAR BERGMAN’S ‘A LESSON IN LOVE’ “What do you do?”

© 2020 by James Clark

The film we’re about to come to grips with, namely, Ingmar Bergman’s, A Lesson in Love (1954), has by all and sundry, maintained that its action amounts to be a “comedy”—a whimsical romance confirming a matrimonial imperative. That would be a validation of mainstream life. Where, pray, comes the idea that Bergman strives for such an outcome? I think I know.

A Hollywood film, from 1940, namely, His Girl Friday, under the auspices of Howard Hawks, a figure nearly as talented as Bergman (though nowhere near as profound), became a “screwball classic” for an era needing some laughs. It had to do with an ex-wife still tangled up with her newspaper editor, being so adept and delighted with the work as to be indispensable. Notwithstanding, she’s about to remarry and leave the job, a prospect the boss can’t contemplate. The ensuing skirmishing, between the incomparable, Cary Grant, and likewise, Rosalind Russell, are an epiphany of old-time, rapid-wit and cynicism. With their barrels of charm, they end up staying together, and the customers applaud with gusto.

Had the customers, of Bergman’s film here, taken a look at the three preceding Bergman films, they might have curbed their zeal about A Lesson in Love being an effort to live up to Hawks’ His Girl Friday. The newshounds are already in their heaven of advantage. Hawks was as flush an adjusted giant as Bergman was as flush a maladjusted giant. (A bit closer, though, to our helmsman, was Howard Hughes!) Though Hawks was, in addition, a daring sportsman, for sure, he would not have wanted any part of the rigors which Bergman faced all his life. As such, Bergman assembles an action with many formal aspects of the 1940 film, but only to display how very different such domestic conflict can careen into long-term emptiness. Gunner Bjornstrand and Eva Dahlbeck, though handsome enough, are not built for swooning, but instead for bloodless self-mutilation. Once in a while a bit of mirth escapes, but only to emphasize the loss of real sustenance. (This seems to be the moment to take to heart how badly served the commentary of Bergman films through the years have been left. A few ridiculously overrated pundits have managed to disfigure the work beyond recognition, to be followed by the quick and the dead. One of the more egregious and destructive faux pas along this slope is the daft reflex to the assumption that early works [like the one here] are minor and dispensable. Bergman was ready to shoot out all the lights from the outset. A Lesson in Love is as brilliant and indispensable as Wild Strawberries, The Seventh Seal and Persona.)

This is a vehicle with many flashbacks during a train ride to Copenhagen, where Marianne, telling David, for the umpteenth time, “I’m not for you, my man,” induces in both of them a reverie of 15 years before and the irony of their wedding there. (We begin here—about the mid-point of the narrative—to absorb the harsh measures being promulgated, measures that strikingly distance the Hawks’ comedy.) Pushing off, one of them brags, “We were like The Three Musketeers… [rich killers with an excuse]. From that fanfare, the missing of Marianne on her wedding day (to sculptor, Carl-Adam) leads out to a stream of casual contempt. At the wedding ceremony underway, Carl-Adam tasks David with finding the bride. Finding, as he knew where she would be, namely still in bed, David becomes a lightning rod to the young girl’s faulty decisiveness. The groom had prefaced the confusion with, “She needs to reflect, analyze the past, say good bye to virginity” [all laughing about that, even the pastor]. Adam chugged down something strong—“You’re supposed to be calming me down”—and turned to David with, “My only friend, can you pick up the car and console her if she needs? I know you exert a tranquillizing influence.” (Behind the two searchers, one of the revelers wore a black and white dress with chevron patterns which no one knew what to do with.) On waking Marianne at Adam’s pad, David discovers that she’d rather marry him. The seriality of the handrails up to the door had not created the sensation it could have. Nor did the Hollywood wind motif, up to the door. But entering, he saw a noose hanging from a light fixture, which gave him a start. When the patrician youngsters are eye-to-eye, Marianne’s eyes are crying. Between there and the feeble bid to use the noose, she deflects David’s scorn—“ What are you saying? The wedding has already begun!”—with , “I wanna die… If you’re going to scold me, you better go.” Followed by, “Can’t I be tired of him, the buffalo?” She cites how handsome David looked on blushing when he saw Adam using her as a nude model. And she adds, “Carl-Adam, the buffalo, laughed and said, ‘He’s [David’s] going to be a gynecologist!’” And finally, she crafts an intimate history of his tracking down an ant in her pants, eliciting from the budding gynecologist, “I’m still ashamed to think of that… ant.” And when she can’t seem to swing David along with her, she pulls down the plaster, saying, “I’d rather hang myself.”

But eventually they do see themselves becoming married (an early Millennial marriage), and rush off to announce the eleventh-hour nuptials. (Not before, however, her declaring, “I’ve loved you for over two years!” And not before David’s deadpan, “We need to talk with Carl-Adam…” [in one of their patented seepage of manufacturing “important information”]. Now, for a bit of spice, she adds, “He’s gonna kill you!” And he adds, “Rightly so. We’re best friends.” And this becomes the origin of a 15-year marriage, with two children. (A few years later, Bergman will return to discern more rotten rich pussies, in his Scenes from a Marriage [1974], replete with another Marianne.) David resists her wanting to make love at this moment, and she praises, “What a strong personality!”—the ways of subterfuge spinning crazily.

Entering the reception to cheers, here screwball shows us something far darker than the resources of Howard Hawks. It involves an effete fraternity. David pipes up, “Dear Carl-Adam, I can’t tell you how annoying it is coming here to spoil your wedding. It’s doubly painful that we are best friends…” Marianne, cutting to the chase, looks for bloody tidings, with, “But we love each other… David and me.” Adam, burly, but far from proletarian, having embarked on an invisible cash-flow and an endless supply of alcohol, laughs a zany laugh, as if someone else has been stiffed (or, as if the contretemps has shot up an instable disinterestedness). The moment provides the once-groom handing over a fine beverage to the traitors. “Let’s toast the new bride and groom! My sincere congratulations!” (This angers Marianne, who had been born to be a princess, never to be fast food, nor to be less than a centre of the universe, carrying a world-wide anxiety about those not endlessly in awe of her supposed prestige and power.) A laugh comes from the artiste. Then, to David, “You’re afraid, you dog!”/ “I can’t deny it,” is the new family man’s response. The sometimes-ugly drunk chooses, “A healthy little man, very surprised…” His smile—now a stage smile—clicks into a murderous register, and he smashes David into unconsciousness. The aggrieved tells her, “Witch!” But Marianne, who in another era would be a leader of a counter-revolution, easily avoids his haymaker. She tells him, being a paragon of convenient correctness, “Are you going to hit a woman?” Adam, perhaps having some class-time at a law-school (the other Marianne follows in her daddy’s footsteps as a lawyer), tells her, “I’ll get you what you deserve, you bastard!” (One of his savage sculptures is in view for the festivity.) She smacks him in the face. The pastor says, “Peace, my friends, peace.” The born lawyer emotes, “Who was wronged? [Who has the advantage?]. On what side is justice? In my innocence! No?” Marianne objects, “What innocence?” she addresses the divine. “And the sluts he uses as models, vertically and horizontally… like a dirty goat!” “I was going to marry this bitch, pastor! I am a man of peace…” She jumps up on a chair and pulls up her dress to expose a thigh. “Kisses me where the sun does not shine. Can anyone see the bite mark? I told people I got it when I climbed up a tree!” The pastor cries out, “Peace, in the name of God!” Adam rushes to the dock. “I protest! Deceptive propaganda!” She retorts, “You protest? I’ll kick you in the ass! That’s right, your pigs dumpling! … Sorry, pastor…I’ve been a maid to this pretentious genius for three years! ‘Marianne do this, Marianne do that… Sew my socks… This food is bad, make some coffee, kiss me… It is an honor for you to serve me, the greatest sculptor in the world! I talk to Michelangelo…’” When he protests, “I never said that,” she comes back with, “You were drunk! You’ve always been drunk. And on our wedding, too!” He protests, “I was sober when the wedding started—was I not, my friends?” Marianne sneers, “You and your friends have never been sober…” (The friends denounce her.) “I’ve passed your threshold for the last time… And I let you draw my breasts, also for the last time…” (She brandishes her fist in Adam’s face.) “And I shit on your art, your immortality, your ostentatiousness and your unbearable and idiotic virility!” She underlines her oration by smashing a cup. Adam tells, “I am very angry with your imprecation… who took you out of the gutter, who will become famous from his unique art… Lick my… Pardon, pastor… the soles of my boots… I gave you a home, food and drink! I was like a father, all these years! [Clichés to the max.] Marianne, you repay me badly. The world is an ungrateful place…”

She, momentarily, and dysfunctionally ashamed, says, “I created a snake in my chest.” David has recovered, given another chance to find equilibrium. “Actually two damn snakes,” Adam perseveres. He loses his balance and falls. Marianne’s self-criticism now out the door, she sheiks in vicious laughter. David does not laugh, nor anyone else. A glimpse of viral derangement. On regaining his footing, he finds a gesture to regain some dignity: “Get out of here or I’ll kill you and that good-for-nothing friend of yours!” And he pushes over the piano for high effect, which belies his commitment to dignity. Then Marianne, seemingly taking a course in self-destruction by way of virulent advantage, declares, “I’ll take everything that’s mine.” She races around the centre, grabbing bits of décor, while the other guests regard her as terminally shabby. Adam does nothing helpful in the way of poise, by smashing all her dishes. “I won’t forget that,” she didn’t have to tell us, “you fucking camel!” She equips herself with a club-like utensil and smashes down one of his larger works. Adam begins to overturn a table; but he manages a second thought. He grabs David, but then pushes him away, before any more assault. He approaches Marianne, with hate in his eyes, while her club is on the ready. He spits in her face, and charges… But then he calls out, “A woman, my friends! What a woman!… The party goes on… Hell! The bottles are empty!” David lifts Marianne! She’s beaming, and so is he! She commands, “Don’t just stand there! Come on, pastor…” Marianne lights a candle, and the guests feel they’ve seen the heart of creative depth. (This being, among other rejoinders, Bergman’s challenge to Hawks’ famous expressive vigor.)

Going into this fascinating, early and far from minor film, we are on the hook to discern how Marianne and David (as we rejoin them on the rails for that supposed date with destiny, in the form of Marianne—once again—about to tie the knot with bemusing Adam) fool themselves that theirs has been and will continue to be a rich relationship. Along with this scrutiny of the protagonists, however, there is hovering over it all the question if anyone surpasses their chaos; and, if so, what it looks like. The narrative transpires in one day, as mentioned, with a flurry of flashbacks exposing both of them as self-indulgent mediocrities.

However, laced within their nausea, there is, as always with Bergman, a motherlode of apparitions piercing, somewhat, the thick-skinned perversity. With the first image, being a music box with a mechanized scenario of a rococo, Era of Reason coquette flitting between two rich men, we are ensnared by essentially obsolete players remaining dominant. This minuet is suddenly shattered by a brief lightning flash, followed by David, having become the gynecologist of his dreams, and being told in his office by an attractive woman patient, “You’re a bastard! You’re spoiled, coarse and technical. And you’ve never understood a woman… You’re extremely naïve…” After feeding her with, “The conjugal bed means the death of love” (wit from the 18th century), he races off to catch that train, having a chauffeur allowing him to doze off and dream about that flirtation he was trying to put in the past. (One very odd vision in that medical facility is his lab-coat—more a trench-coat than an indoor apparel. Then there is the chauffeur, Sam, speaking along lines of Hollywood detective, Sam Spade. Does the “technical” worthy need a supplement of something else? Another of David’s epigrams is, “Perhaps repentance and painful conscience are only Siamese twins” [another nod to something missing]. The impatient woman patient is seen in a chair involving a pattern of delicate parallel lines, hoping for sensation. Try to keep in mind this surprising bid of ragged poetry, from the supposed “technical,” because one of the highlights of this film shows him, very briefly and near the end, to be truly distinguished.)

The dance of Sam’s windshield wipers lulls him to sleep; but it could also, given the right outlook, be a shot in the arm. “You have nice hands and a very beautiful neck,” David praises. He continues, “I have certain principles with regard to marriage and faithfulness… I have an extremely attractive wife that I sincerely love. I’ve never been unfaithful…” (This after his reminiscence of his kissing another woman in the moonlight, after his wife went to bed.) The mistress, Susanne, tells him, “You have an uncontrollable will to kiss me and that’s not all…” His retort is, “I prefer my life with you to be one of small joys and hassles. I prefer my slippers and the indifferent fire from the fireplace, to a perfumed body, and a completely different fire that is dangerous and suffocates everything we call home, children and decency. And gains absolutely nothing.” (Little does he recognize that the fireplace is not indifferent!) A dream being more candid, he veers into, “I don’t love you, but I have come to touch you and erase my apathy by fire. Let me overcome the garbage in my brain… This was banal, stupid, silly and ridiculous.” She, seeing him making her point, calmly says, “Don’t talk any more, just kiss me.” He begins to kiss her, and then backs off… rattling on, “My cogency is indispensable, however boring.” She smiles, “Think of it as a diversion…” He tells her, “I’m crazy with desire, who wouldn’t agree to it?”/ “I’m still waiting,” the more coherent of the two tells him. “Your wife doesn’t trust you. Fidelity exists if you are faithful… Infidelity is the invention of moralists and gossips.” He seems to need more talk: “If I’m going to hell, you’re the best company.”/ “Men need reasons for everything,” she triumphs. “I dreamed about you at night,” he blurts out. Going farther, he says, “You were like our own child!” Her response? “He’s turning into a poet…” And—of course—they kiss passionately.

In a coda to that romp, David doses off again during Sam’s trusty navigation—this time elicited by a ripple of light from the highway. (These occurrences, however, could be part of an agency of incisiveness.) This time bodies, not talk, take over, due to a lovely archipelago just beyond Stockholm, also seen in Bergman’s sensual films, Summer Interlude (1951) and Summer with Monika (1953). David and Susanne (the “patient”) drift in his sailboat. “The delicate memories remain. Yes, that summer…” A shimmer from the seas passes over her face (like the “glitches,” in the 1951 film, eliciting mystery and joy). His refusing to go swimming stings her, in her journey toward disinterestedness. “I see, one, two, three, four… stars,” he avers, prosaically, not on the same page. They both admit to be tired. She takes his pipe out of his mouth, and puts it in her mouth. He feels “satiated.” She’s “insatiable.” He declares, “Men cannot vegetate.”/ “You can’t just be,” she complains. “I want to do some research,” he posits. (But research is a wide-ranging notion. A test for both of them.) Her slur, “That’s so minor,” finds her at her worse. He trots out a slur, himself: “Eat, eat, satisfy.” And then she waits for the product, “Hate.” Once again, a shimmer of light from the sea passes over her face and body. Instead of a progression, there is an impasse. “You’re tired of me,” she declares. His, “I didn’t mean that,” is met by, “Yes, that was exactly what you did mean. Don’t try to dodge that.”/ “I could spit! But you’re under my skin… at the tips of my fingers…” She counters with, “I’m a kind of poison…”/ “Call it what you want. Stop smoking my pipe… You leave it filthy.” (She could have turned the tables by saying, “You leave it pedantic.”) She grabs his throat. “I could cut your throat!”/ In a flash, he chirps up, “I’ll show you the quickest way! Put my head on your desk, and use a lamp [emitting no light] to smash me between the eyes.”

Catching the train was easy. Using the train was not. Such a vehicle happens to be one of Bergman’s means of offering the gifts of dynamics to a sluggish constituency. No longer wearing his eccentric lab coat, David, like a gumshoe, plies the first-class relaxation until he finds Marianne. And here comes one of the film’s “whacky,” “screwball,” and let’s face it, “cynical,” initiatives, face-to-face with His Girl Friday. Seeming to be encountering someone he’d never met before, the droll Carry Grant wannabe obsequiously addresses his wife, “Is that place occupied?”/ “No, it’s unoccupied,” she reports, not really surprised befalling complicating from an agency who had driven her to the portal of divorce. The supposed classic, harmless pedant, begs her to spare his frail constitution, by moving over to the window seat. “I don’t like the wind in my face.” In the maneuvering there, he pretends to accidentally sit on her purse. (The ambiguity of David’s powers is a major hot spot to consider.) After the arrangements are finished, the other occupant of the deluxe room, a gregarious gentleman, making a point of never taking a train due to being an avid car driver—whose car is needing repairs—sizes up David as a rather meek intellectual. (The little home away from home, however, is provided with headrests in the form of patterns of two wings spread out, and a central figure therewith of oblique nature. There is something engaging about the pattern, to be sure; but there is also a fascist, military thrust.) The genuine stranger also sizes up Marianne, as one of his type, sophisticated and promiscuous. He fibs being delighted here, without his expensive chariot, telling his audience, “We can meet nice people… and beautiful ladies…” Cut to Marianne, who smiles warmly and then opens a book she was reading before David messed things up. The latter opens his valise and begins to read a formidable-looking book. That brings from the mixer, “A black-cover book, huh. Probably modern literature. Can I ask its title?” It reads, “Introductory Study of the Arterial Circulation and Sexual Glands.” Marianne rolls her eyes in boredom, seeing in the stranger a soulmate. She asks for a light (David’s incursion being more annoying than she realizes). And, Hollywood Lite, the people guy immediately lights her cigarette while David’s lighter refuses to perform. (Like a TV ad. This motif takes off in earnest, in Bergman’s punchy rendition of The Magic Flute [1975].)

The couple whose wedding was unusual might have been understood, by those not present at the reception, as merely eccentric. But we have Howard Hawks’ Hildy and Walter, from the era of real screwball, never departing from the aegis of savvy skepticism. They enjoy the cuddle of a virtually universal escapism. With Marianne and David, however, there is an intensity far abrogating even the quirky normal. Their sham of being strangers is actually a truth. She’ll go out of the chic little cabin (regarding David with disdain), to visit the washroom, whereupon the critic of modern literature proposes to the supposed easy mark a bet that she’ll happily kiss him before the trip is over. “What a woman!” he exclaims (the very words that Adam used during that up-and-down wedding). “What posture, what way of walking, what breasts…” David is almost serene, having, in the course of rushing to save their marriage, a strange disinterestedness. Here the dynamics of the ride, seen out the window, show up. “Won’t you be sad left alone?” the rambling gambler asks./ “On the contrary!” David enthuses. Then they both laugh uproariously, for different reasons. The conductor comes in, and by this time David covers his eyes. That visit done, he opens his book, but he doesn’t read. He stares into space. The book falls on the floor. A lesson in love. (The carpet shows a pattern of binary forms, with a gap.) Two photos fall out of the pages, and he’s in a mood to relive, by reverie, an episode pertaining to his daughter, Nix, played by Harriet Andersson, who—talk about “nix”—had only a few months before portrayed the savvy skeptic, Monika, in Bergman’s film, Summer with Monika (1953).

Of course, the gambler gets his face slapped—a slap coinciding with David’s resumption of trying to make pearl out of swine. (He bets the kissing loser that he, the supposed nerd and nothing else, can kiss the chick. And he wins, though winning with Marianne is hardly winning.) Thus, begins a pell-mell race of our bemusing protagonists performing yet another blind alley. (Nix takes over the memory, with her crusade to never marry, to stay masculine and to resent her parents’ going separate ways. “It’s not healthy for a woman living without a man… [more incoherence]… It’s so disgusting! I pity all women.” They visit an uncle/ potter (everywhere they turn there are estates and the idle rich); but Axel, the artisan, does carry some gentle, if quietist, traction. Moreover, Nix’s noisy rebellion does sustain some sense. “It means that Mom also plays the ‘love game.’” (In a show of ambiguity, she also declares to David, “If you have a new lover, let Mommy have hers.”) Seemingly a level-headed, classical rationalist, the dad advises (with something up his sleeve), “The best of life seems to be a collaboration.” Nix sums up the day, “And you’re a baboon!” After a pause, he replies, “Yes, maybe I am.” She adds, “You despise yourself, Daddy!”/ “Yes, Nix. I despise myself. I see everything being infinitely incoherent…” How lacking in acuity, comes in the follow-up: Nix, unsparing, “So you see Mom, and Pelle [Nix’s brother] and me to be incoherent?”/ “No!” [of course], he rushes to assert. “They’re the only thing I care about!”

Now that the voyager finds herself needing more substance and far less fantasy—Marianne, beginning with feigning a bit of grit in her eye (grit being in short supply) which David attends to with some body contact—attempts to fabricate some validity for her folly of linking to an alcoholic idiot. How far had David slipped from the momentary reflection of his past moment with Nix? He tells Marianne, “I’m known for my delicate touch…” She thinks to be on solid grounds by musing, “I’ve always thought of the huge powers that a gynecologist has over our hearts and our confidences.” He brags, “You can lose your head. Sometimes it’s relaxing.”/ “Does his wife also find it relaxing?” she asks. And he snipes back, “She seizes the opportunity to lose her head.” After much more mutual steeling, David shifts to self-criticism. “Aside from reproduction, man is an insignificant player in the world of women… I admit my inferiority without grudge. I just cannot babble…” [a means of surrender including being tops, anyway].

Babbling and embarrassing seem endless, coming from blast-furnace experts of advantage. Let’s see the rare moments of vision, as the action subsides to spineless retreat. Adam, that easy target, drives Marianne to the epigram, “A grown man is rare, Dear David.” But she spoils it with the loopy arrogance, “A woman chooses the man-child whom she fits best.” He musters, “In the beginning, it was just you and me… A company with a future. [But seeing yourself as cash-flow, therewith, is in fact a form of bankruptcy; however, a ‘company’ may be quite a different action from that.] Our painful experiences can be our start-up capital.”[Painful experiences may veer for good; they may also veer for collapse.] David, bidding for a prolongation of what was already too long, enlists the wrong powers, powers of bathos: “Give me again your heart, and I will treat you like a sacred reliquary.” (His winning kiss is far less than it might seem.)

As Marianne drifts for the second time to leave Adam in the lurch on account of an extended family too big to fail, they, nearing Copenhagen, bring us along in shaky celebration to the birthday of David’s father, only a year before real time. By this time, Marianne routinely puts down booby-traps to spoil, for instance, David’s morning at the palatial homestead. (And, before that, he rudely slaps her ass as a wake-up call.) The grandma, barging into their temporary bedroom and ignoring Marianne, wants it known that the birthday boy—forever the pedant—got up at 3 a.m. to change for the party. But the day does put out some magic. Sam, turning out to be the oldsters’ chauffeur, can’t persuade the ancient limousine to start, and they take their two horses and a cart to attempt to make the day shine. A flute passage jumps up, and the woods are everything the household isn’t. They arrive at a cliff on the seashore, and they scatter at will. The protagonists invade a pristine swatch of saplings touched by a bright sun. Their cigarette smoke-clouds predate vapers. “Do you still love me,” she asks. “That’s a stupid question,” is all she gets. “Imagine that it ends one day…” she continues. “No one’s beautiful like you,” he asserts. And in response, she says, “I’m serious…” The subject of his mistress hovers like bugs. And she, hardly a paragon of stability, emotes, “When you are far from me, only for a day or so, I feel I have become small and sad. And as if everything died around me. Is that weird?” Her jist comes down to, “Let nothing change,” and let’s have another baby… (“Imagine its smell,” she brandishes… “Imagine holding that life… I get creepy talking about it…” All of this futility occurs in close-up, with them reclining in the grass.)

Still in reverie, but productive on the basis of hard-wired outlooks, earlier on that day, while waiting for the car to behave, grandma demands that grandpa return to the house and put on one of his best vests. Nix is ordered to accompany him, and a conversation takes place, a conversation, opened by Nix, which David and Marianne would regard to be “small and sad.” The candid granddaughter asks, “Grampa, are you afraid to die?” His response is, first of all, “No, not at all, I believe in God Almighty. I believe in the next life and all kinds of life… Death is just a little part of life…” He mentions that life forever would be a bore. [Coherence be damned!] “It’s understandable that a child be afraid and worry. Only an old man like me can begin to solve the meaning of life… Everything has a beginning, a middle and an end… Maybe this life is just the beginning…” Nearly everyone subscribes to that pattern; but the dramas sustaining the work of Ingmar Bergman don’t.

The train conductor snaps them out of that. They meet Adam at the station (the host seemingly and unbelievably forgetting who David was) and the less than fully welcome third proposes going to a hot club. (Before that, at a café for a bite, Adam salivates, “What a wonderful idea! The woman, the lover and the husband!” From there they take a ferry to the heart of Copenhagen [a craft resembling the boat in Bergman’s Summer Interlude]. On this interlude, Adam—perhaps stung by David’s congratulation, “Marianne said you were sober for several days”—maintains, “Women are realists. They choose the strongest. I have big muscles…” David mocks him that his works will be known 2000 years from now; and the artist reports, “You’re being ironic, but you’re right… Women love the great artists…” A flurry, in close-up, of a tray delivering their drinks, comes and goes without attention.)

Back to David’s last-ditch hope at a hot club, Marianne moots, “Maybe another drink won’t hurt.” He, looking for a miracle, jazzes up the fanfare, “Promise me that we’re going to hell! [hold that thought]. I want to see something exciting. Slightly immoral. Something shocking!” There’s a jazz trio, far from shocking; a woman swirling, sort of like Rita Hayworth in, Gilda, and, to Adam’s annoyance, David and Marianne enjoying a dance together, cheek-to-cheek. In that moment of solitude for Adam, the budding family man, he notices a close friend, a hooker, in fact, and he prevails upon her to get David into single-guy mode. For good measure, he arranges by way of his close-buddy-bartender, to induce David to drink a notoriously unhealthy stimulant. (On entry, Adam calls out, “Marianne is an independent woman. She isn’t bourgeois [like you]. There is no such thing as purity. Only impotent men are faithful. Wives betray you without delay.”) Lise, the supposed distraction, complaining, “Business is bad,” tells Adam, “He’s very attractive” [and though he steps on Marianne’s toes, his renegade gambit shows him at his best]. Marianne knowing something’s that wasn’t there before, asks, “Are you crazy? What’s wrong with you?” (David’s explanation is not quite right—“This dance made me excited!”) She glares and marches away toward Adam, where she grabs the bottle out of his mouth, his equities plummeting, while the blur of the takeover could have been gold. Lise catches up the seldom-dancer, and declares, “David, you didn’t see me?” He smiles within his rare roll. “Give a kiss to Lise!” (Marianne sees this affection, and becomes even more angry. Adam remarks, “It’s nice that David found a girl.”) The new lovers come to the designated bartender. While waiting for the complex mixture, he asks her, “What do you do?” In a flash, she comes up with, “I’m a teacher,” adding, mysteriously, “You want a deal?”/ “What do you teach?” he continues. “My love, of course… What did you think?” And she exposes a shoulder and chest. David has a moment of nonplussed (“Where’s Marianne?”) ; and recovers with laughing out loud, “I’m an idiot, Lise… Hello!” (The ebb and flow of this tonal frontier being never surpassed in Bergman’s many delights.) Then he drinks some of the preparation (the bartender alarmed). He drains the glass (the bartender sticking out his tongue in empathy). “A love potion,” he says. Lise the critic says, “Yeah, good!” The bartender—right out of Depression Era Hollywood—fears the worst. “Can you give me the ingredients?” David asks. “It goes down to the knees… Now I’ve lost my muscles. Why did I do this?” he asks. And he’s glad he’s become (perhaps not for long) someone he’s never been. He orders a second wave of seemingly out of this world, and Bergman’s perfect pitch shows no more reaction from the front line. “There’s a kink in my neck,” the crasher observes; and his glasses fall off. “You look better without glasses,” Lise enthuses. He then treads another step toward dangerous and necessary territory. “Lise, my girl, you’re so beautiful one could die for. But you shouldn’t tie up your hair. You must be loose and free! Like rapids!…” (Cut to the farther range of the bar, with Adam smug and Marianne morose.) “Let’s dance!” the hidden talent calls out./ “Yes!” Lise winks to him. (All smiles.) On the crowded dance floor, Lise says, with more than professional delivery, “Kiss me, David!” He remembers he hasn’t had his second drink. On completing that, he says, “Now, I’m going to kiss the most beautiful girl in Denmark! Not even the King could disapprove!” He, tiger-like, tells the crowd, “Get out of the way, I need space!” He backs into Marianne, produces a rude gesture toward her, and pivots away. Adam laughs uproariously. David kisses Lise passionately. The room applauds. Marianne grabs Adam’s drink and drinks it down. David kisses Lise once more, as if he’d made a discovery needing more details. Unfortunately, impetuous and violent Marianne rushes into the caress; and chaos ensues. Recalling 15 years before and the seriously questionable embrace there, Marianne reverts to advantage at any cost. “Let me go! I’ll make mixed meat out of her!” Lise rushes to find David, but he has left the building, and left forever not only his moment in the sun, but hers’. She does find Adam, once again failing to find some kind of marriage. “I want to scream!” she tells him, far more a lady than what David had pulled out the stops for.

The denouement, winding up in a 5-star Copenhagen hotel and its bridal suite, with a card strung on the door handle ordering, “Do Not Disturb,” is one of the saddest celebrations you could ever imagine. Cutting from the bar, we have David and Marianne at twilight, along a canal as seen from the other side. She is shrieking like a complete fool, and marching toward him with a panzer attack, while he silently back-peddles. “How could you kiss that filthy and vulgar slut? And right in front of me! Your promises are worthless… I want to fuck you!” David, still slightly in a moment of vision that Marianne will never for a moment savor, has what he wanted, and he might as well be dead. The advantage-pro dips into the world of entitlement and rococo: “I’m sad, cold and depressed. If there’s water here, I’m going to drown myself… I’m going to pummel you first!” David, shrinking by the minute, manages to say, “My beloved Marianne. What a day, what a night!” Sam, the fixer with the fixed limousine, had handled all the arrangements for a night of, if not love, victory. On being driven to the appropriate address, the princess exclaims, “David, you slut! You were so sure!” Masters of ceremonies. Midgets, forever! Once again, that 18th century music box confirming endless nothings.

0 notes