#trc analysis

Text

THREES THREES THREES:

Oh hello. I want to talk about the stylistic/textual role of Threes in The Raven Cycle.

Threes – as a general concept and as a number – are a major symbol and motif in the series. Maggie tells us that threes are important from the very first book: from Maura’s favorite saying being “good things come in threes” to Persephone telling Adam that “things are always growing to three or shrinking to three,” threes are discussed at length in the text of the narrative. Maggie also shows us that threes are important as a motif/symbol for important aspects of the story: three Raven Boys, three Fox Way women, three Lynch brothers, three main ley lines, three sleepers, etc. Threes are, textually, incredibly significant in The Raven Cycle, and we know this because we are shown AND told it throughout the entirety of the books.

We all know the significance that is given to threes in the story itself, but what I want to talk about is the usage of a thrice-repeated word or short phrase (going forward I’m referring to this as “Threes” or “a Three”) as one of Maggie’s writing signatures (across the series, there are 65 Threes). This creates a meta level to threes being an important aspect of The Raven Cycle universe. A classic example of a Three (one of my favorites, in fact) is from The Dream Thieves:

“As they walked, a sudden rush of wind hurled low across the grass, bringing with it the scent of moving water and rocks hidden in the shadows, and Blue thrilled again and again with the knowledge that magic was real, magic was real, magic was real.” (TDT, 12)

In a way, the Threes join the intradiegetic (what is happening within the narrative itself) with the extradiegetic (what the narration is communicating solely to the reader). The reader and characters are told explicitly that the number three is significant, important, notable, and powerful. In using Threes as a writing signature after giving the reader that information, the Threes are designed to signal to the reader that this line, this moment, is important.

So the question is: What Are The Threes Trying to Tell the Reader???

Amazing question.

In my recent TRC reread, I was already keeping track of Threes, because I was curious to see how many times they appeared. And then my sister, who was also rereading, said something interesting (after reading this Three from The Raven Boys):

“He was full of so many wants, too many to prioritize, and so they all felt desperate. To not have to work so many hours, to get into a good college, to look right in a tie, to not still be hungry after eating the thin sandwich he’d brought to work, to drive the shiny Audi that Gansey had stopped to look at with him once after school, to go home, to have hit his father himself, to own an apartment with granite countertops and a television bigger than Gansey’s desk, to belong somewhere, to go home, to go home, to go home.” (TRB, 370)

My sister said: “Adam’s like Dorothy.” And then she said: “Wait. Do you think the Threes are like a spell? Or… a wish?”

Which was……. Interesting.

What I have determined, after completing my reread and spending way too much time analyzing this, is that a Three is either a wish, a hope, a longing, a prayer – or, alternately, a warning, a curse, a negative promise.

In either sense, Threes are a foreshadowing of what is to come – whether it be good or bad. Threes exist to signal to the reader that they should be paying close attention to whatever is being said or observed.

Threes in….. Everything Else:

Before we get too far into TRC Threes, let’s talk about the precedent for three being an important number in art, math, storytelling, etc. I found some interesting information about how three is a satisfying number for the brain:

Grouping things in threes leverages the power of repetition to aid memory; denote emotional intensity or importance; and ease persuasion (research by Shu & Carlson (2014) found that three positive claims is the most effective for persuasion).

Three is the smallest number that the brain can still recognize as a pattern, and the brain loves pattern and repetition. This is true in visual art – having three main compositional figures to create a pleasing image – and also in storytelling and narrative. Using threes for repetition in storytelling is a very common occurrence.

Some classic examples of repetitive threes are Shakespeare’s “tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” or Lincoln's “a government of the people, by the people, for the people.” In each of these examples, a repetition of three is used to create pleasing auditory rhythm. There is something inherently memorable about literary Threes.

Perhaps the most interesting information I found while digging into the precedent for threes is about the rule of threes in folktales. This information happens to come from Wikipedia (side note: Wikipedia is a modern tool of collective consciousness and we should utilize it more). This page describes how in its most basic form, the rule of threes in storytelling is just beginning, middle, and end. Because this is such a common convention, writers tend to “create triplets or structures in three parts.” It then talks more directly about the use of threes in folktales:

“Vladimir Propp in his Morphology of the Folk Tale, concluded that any of the elements in a folktale could be negated twice so that it would repeat thrice.”

This is especially interesting to me. The idea that an element of a folktale “could be negated twice so that it would repeat thrice” shows up prominently in the plot of The Raven Cycle – a book that is heavily influenced by folktale motifs – but also in so many of the folktales/fairytales we all know. A classic example of this would be Goldilocks and the Three Bears – Goldilocks must try porridge that is too hot, too cold, and then, finally, just right. The journey of these three actions is satisfying to the brain because it is a complete pattern: the third and final result of “just right” porridge is only satisfying because of the two “not right” porridges that preceded it.

Getting back to Stiefvater Threes:

For anyone who’s seen The West Wing (and even those who haven’t), here’s a good way to explain what I think the Threes are doing. You know that thing they do during a The West Wing “walk and talk” where two characters will be throwing information and little quips back and forth at each other rapid-fire, and then suddenly, they will both stop walking, and the camera will stop moving, and they’ll say a line that contains really important information that you need to know to understand the storyline of that episode? That’s what Maggie’s Threes are doing for the reader. That’s what 6:21 is doing for the characters. It’s intentional: the writers/directors/actors/camera operators on The West Wing know that they’re throwing a lot of information at you, and know that they need to get you to pay attention to the most important parts somehow, so they do it by forcing the viewer to lean in and listen. It changes the focus and energy of the scene from something with momentum to something that pauses, and therefore makes you pause.

The Threes compel the reader to pause and consider the information being delivered as more important than they might consider it if it was not written as a Three. “Maura’s expression was dark” does not read the same as “Maura’s expression was dark, dark, dark.” And in a text where characters directly state the magical importance of threes, compounded by three as an overarching motif, there is clear intention and meaning behind these written Threes.

In the context of TRC, Threes act as a fourth-wall break.

They are essentially a way to poke the reader and say: “Are you paying attention? Because you should be.”

These Threes use a symbolic motif – the rule of three – that is already heavily discussed in the text – to get the reader to pick up on the internal motivations of the character who is “wishing” their Three or the narration which is using a Three to foreshadow some important aspect of the plot.

The Threes are like the literary equivalent of a record scratch. It stops you in your tracks, breaking the established rhythm and making you take notice of what is being said in a new way.

Let’s Look at Some More Threes (but just a few don’t worry)!

1. We get a classic Three, and a very Gansey Three, right after the group comes out of Cabeswater:

“‘What about that thing in the tree?’ Blue asked. ‘Was that a hallucination? A dream?’

Glendower. It was Glendower. Glendower. Glendower” (TRB, 231).

Finding Glendower is one of Gansey’s core wishes, one of his core longings. Although this line is a literal answer to Blue’s question – he saw Glendower in the tree – in making it a Three, Maggie has given it added weight and meaning. It is prayer-like in its intention. It is almost an incantation: by saying it in Three, Gansey wishes it into being.

2. In The Raven Boys, after Gansey has bribed Pinter to keep Ronan at Aglionby and has learned that Noah has been dead the whole time they’ve known him, we are given this Three:

“The Pig exploded off the line. Damn Ronan. Gansey punched his way through the gears, fast, fast, fast” (TRB, 311).

This moment foreshadows what directly follows: a distinct lack of fast as the Camaro breaks down and Gansey is held at gunpoint by Whelk. This Three is not a prayer, but a warning, and an indicator to the reader that something important is about to happen. Had Gansey not been trying to go so “fast fast fast,” the car might not have broken down; because the Three incanted it, disaster follows.

3. To return to a Three I have already mentioned, but follows the typical Three structure:

“...to go home, to go home, to go home” (TRB, 370).

In this scene, Adam’s wish is less about actually wanting to return to his literal home, because his house was never really a home for him. Adam’s wish/longing is for a home that he could return to, that he would want to return to. He is longing for a place/feeling/experience that does not exist for him. The Three in this sentence comes after a string of active wishes/longings, and by ending with this Three, it casts a spell of sorts, honing in on the truest underlying wish that Adam has. In using the phrase “to go home” three times, the narrative is making sure you, the reader, know that this want, this need, this wish, is the most Important to Adam, and will drive his actions for the rest of his story.

Most of the Threes feel like this. They are often tacked on at the end of a sentence or embedded in a sentence. They’re an addendum to the action of the story. They’re like casting a spell – once to manifest, twice to charge, three to cast.

…..And Some Other Types of Threes:

Then there are the Threes that don't follow the typical pattern of the same word repeated three times one right after the other, but are still a Three in a different way.

There are short phrases/sentences that are repeated three times throughout a page or chapter. In the prologue of The Raven King, we get this:

“He was a king…

He was a king…

He was a king.

This was the year he was going to die.” (TRK, 1-3)

In this case, the Three acts as a promise of Gansey’s kinghood, but in ending the sequence with “this was the year he was going to die,” the promise of the three is given a condition: it is not going to be a joyful kinghood, but instead a kinghood intertwined with the death we’ve known is fated for Gansey.

One of Adam’s Threes from Blue Lily, Lily Blue, uniquely breaks the mold of Threes in a format that does not appear anywhere else in the four books:

“It was his father.

He opened the door.

It was his father.

He opened the door.

It was his father” (BLLB, 242).

❋ (We’ll talk about this one more in-depth later.)

There are also a few “unfinished” Threes:

In The Raven King when Ronan is having a nightmare (infected by the demon) about Matthew and the mask, he has this Three:

“Ronan’s throat was raw. I’ll do anything! I’ll do anything! I’ll do anythi

It was unmaking everything Ronan loved.

Please” (TRK, 96).

With the uncompleted Three, there is an uncast wish. Ronan’s wish is about Matthew, yes of course, but also about being willing to do anything to keep those he loves (ie. Adam, Gansey, Blue, his brothers) out of the reach of the “unmaking.” This unfinished Three serves to foreshadow the harm that does ultimately befall first Adam and then Gansey as a result of the unmaking of Cabeswater by the demon: without the Three spell completed, his wish is not fulfilled.

*This is Not all the uncommon/mold-breaking Threes, just a few that are interesting!

Do All Threes Come to Fruition???

The short answer is: No. Or at least not in that way.

Once again looking at the text of The Raven Cycle, we are given an answer of sorts. In discussing Gansey’s predicted death, Maura says:

“First of all, the corpse road is a promise, not a guarantee” (TRB, 155).

This seems to apply to Threes as well. Threes are not a guarantee. They are a promise. Not all Threes come to fruition the way one might expect – or at all, for that matter. The important part of Threes is not that they will definitely come true, it’s that they could come true, because the Three gives them the potential to come true.

Structure, Structure, Structure:

The main Threes structures are:

Three of the same word separated by commas:

“magic, magic, magic” (TRK, 59).

A short phrase/sentence separated by periods:

“My father. My father. My father” (TDT, 369).

A short sentence that is repeated three times throughout a page/paragraph:

“Gansey did not breathe…

Gansey did not breathe…

Gansey did not breathe” (TRK, 209).

A word that is repeated three times and is connected by “and”:

“Round and round and round!” (BLLB, 224)

Italics vs. Non Italics:

Italics in The Raven Cycle are often used for character’s inner thoughts/anxieties. This continues to be true in the context of Threes. A Three that is not written in italics indicates a promise, or some foreshadowing of a plot point being foretold through the Three – it is typically more “real” – whereas a Three that is written in Italics seems to indicate a wish/hope/longing that is unattainable in some way. Italics almost always indicate a Three that may never come to fruition, or at least not in the way the character hopes it will.

An example of this distinction can be found in chapter three (hah) (I don’t believe in coincidences and neither does Gansey) of The Raven King:

First we are met with Ronan wishing/hoping to return home:

“That morning, Ronan Lynch had woken early, without any alarm, thinking home, home, home” (TRK, 24).

This home, home, home, is in reference to the idea of home rather than the reality. Ronan is wishing to return to a home that does exist physically, but is not the same as in his memory – he wants to be at the Barns as it was in his childhood.

Then, in the very same chapter, Ronan actually returns home and we are given this Three:

“Slowly his memories of before — everything this place had been to him when it had held the entire Lynch family — were being overlapped with memories and hopes of after — every minute that the Barns had been his, all of the time he’d spent here alone or with Adam, dreaming and scheming.

Home, home, home” (TRK, 27).

This second home, home, home, is about the actual reality of being in his childhood home – the good and bad that has existed in the years since the childhood he longs for.

The Addition of AND:

The most notable use of “and” is in Noah’s very last chapter:

“Sometimes he got caught in this moment instead. Gansey’s death. Watching Gansey die, again and again and again” (TRK, 416).

When “and” is added into a Three, it becomes circular, cyclical. The “and” gives the Three a sense of infinity, or creates a loop of sorts.

This Three operates in the same way “tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” does in Macbeth – it is meant to convey the endlessness of time, a relentless cycle of tomorrows.

❋ While there are not many of these Threes with “ands” in The Raven Cycle, there are other examples of Threes or Three-like occurrences that fulfill the same purpose as the “and.” For example, remember this Three:

“It was his father.

He opened the door.

It was his father.

He opened the door.

It was his father.” (BLLB, 242).

In this case, instead of the word “and,” the Three (It was his father) is connected by “he opened the door.” This Three is accomplishing the same feeling as “again and again and again” – the feeling of being caught in an endless loop.

Another example of an (implied) “and” in The Raven Cycle is: Gansey’s life. Gansey starts out alive and then dies as a child only to be reborn, and then killed again through his sacrifice, and then reborn for a final time. Gansey is Alive, Dead, Alive, Dead, Alive. And so Gansey’s life is a cycle of Three.

As with the Threes that contain “and,” Gansey starts where he ends: alive.

Other Ways Threes Show up in The Raven Cycle:

I will state the obvious once again: there are three Raven Boys, three Lynch brothers, three Fox Way women, three sleepers, three main ley lines (the lines that “seem to matter” to Glendower’s story), Gansey the Third (Gansey Three, Dick Three).

There are also the more obscure: the “three kinds of secrets” in The Dream Thieves prologue and epilogue; each Lynch brother inheriting three million dollars from Niall Lynch; the three figures with Blue’s face on the tapestry and later as a vision in Cabeswater; Adam and Gansey going to DC for three days; the shield pulled from the lake having three ravens embossed onto it; Ronan having dreamt Matthew at the age of three; the door to the Demon’s room needing “three to open” it; Aurora Lynch staying awake for three days after Niall died.

And of course, we have the ley line symbol/chapter header:

And then there are the 300 (three hundred!) Fox Way “villain” readings. (This was something that was particularly interesting to me.)

The first antagonist we meet is Whelk. When he comes for a reading at 300 Fox Way, he first pulls the Three of Swords.

When the women all draw cards together, they pull identical cards for Whelk: three of the Knight of Pentacles, then three of the Page of Cups. After drawing, essentially, three threes (the Three of Swords, then two sets of three matching cards) in this reading, the first Three of the entire series appears:

“Maura’s expression was dark, dark, dark” (TRB, 124).

The second “antagonist” we meet is the Gray Man, who comes to 300 Fox Way in The Dream Thieves to “observe.” Maura, Calla, and Persephone are predicting which card is on the top and bottom of the stack and the first card, predicted by Calla, is the Three of Cups off the top of the deck that Mr. Gray is holding (a remarkably happy card in stark contrast to Whelk’s Three of Swords).

When the third antagonist, Greenmantle, comes for his 300 Fox Way Reading he also draws the Three of Swords. The fact that each of the three antagonists come for a reading is in itself a sort of Three, but to further the importance of these moments, each of them draws some sort of three-related card.

All of the examples I have touched on have been more symbolic references to Three as a motif of the books as a whole. However, Threes also show up in the literal number of times important quotes are said/written.

I was tracking some of the most well-loved TRC lines to compile them, and noticed that the lines “don’t throw it away” and “safe as life” happen to appear exactly three times throughout the series. This was honestly pretty surprising based on the importance of those quotes – I would have assumed they showed up far more. Actually, they both appear twice in The Raven Boys and once in The Raven King. Threes, and the importance of Threes, is embedded so strongly into the narrative of The Raven Cycle that even the quotes we all think of as the most beloved of the series follow this rule of Threes.

Now, could you chalk some of these up to coincidence? I guess. But Gansey doesn’t believe in coincidences so I don’t either. So what’s the point of all these Threes?

Conclusion???

In a literal, literary way, Threes are a fourth wall break to make the importance of a moment obvious, but I’m not sure what the larger “point” of Threes is. My best analysis comes from the idea of The Raven Cycle being all about time and Threes playing into the importance of time as a sort of record scratch or loop. The Threes, as a stylistic, written motif, seem to connect the time-based cycle the characters experience to the time-based cycles the reader experiences by reading the books.

But my conclusion feels incomplete and so I would like to rely on the collective for this one – just about the most Raven Cycle thing you can do. So I’m asking you, the collective you, what conclusion would you draw? What do you think?

What I do know for sure is that Threes are magic, magic, magic.

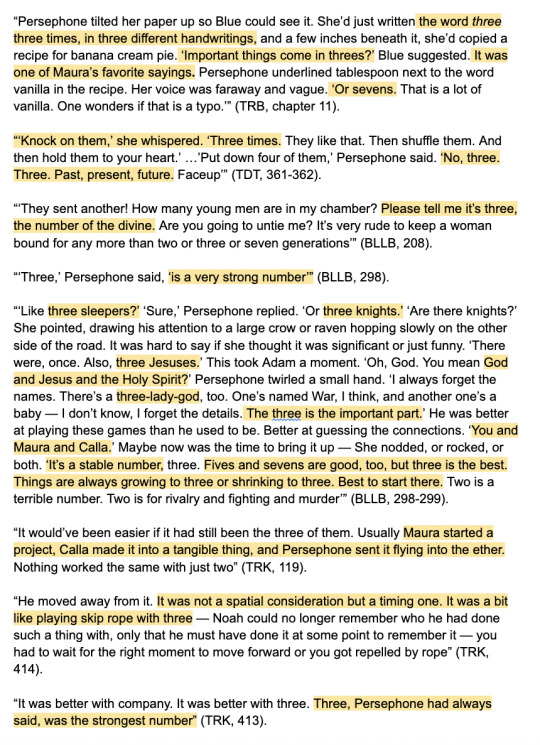

For Your Convenience: Here is the textual significance given to threes within the books (chronologically):

And here are the Threes, Threes, Threes (compiled):

(If you made it to the end of all this, I love you. Have a gold star and a hug <3)

#sorry for the aggressive caps lock i wrote this in google docs#wow this is embarrassing#i'm okay with it#i spent my break writing a 16 page paper#the ganseyism of it all#some people asked for an essay so blame them not me#trc#trc analysis#maggie stiefvater#the raven cycle#the raven boys#the dream thieves#blue lily lily blue#the raven king#the gangsey#blue sargent#richard campbell gansey iii#ronan lynch#adam parrish#noah czerny#gangsey#mine

174 notes

·

View notes

Text

thinking about how one of the main themes of tdt is the price of being yourself. like literally every character is facing choices and dilemmas dealing with facing the risk of what it takes to become oneself vs becoming the self you think you’re supposed to be. like:

declan: the price of staying safe and invisible vs the price of being seen.

ronan: the price of fitting in to a world not designed for him vs the price of owning his power.

matthew: the price of being the perfect golden child he’s always thought himself to be vs the price of discovering what he really is.

hennessy: the price of continuing to run and hide from trauma vs the price of facing herself.

jordan: the price of living on the sidelines as just another part of hennessy vs the price of becoming her own person.

carmen: the price of following what she’s been taught to believe is right vs the price of listening to her internal conscience.

adam: the price of being liked for a fantasy vs the price of being known for his true strenghts and vulnerabilities.

even the visionaries as a metaphor for the terror of becoming. they literally oscilate between ages and can either create explosions with their changes or pay the price of letting themselves slowly die for the sake of keeping others safe and comfortable. and the main “villain” of the lace not being a villain but an amorphous thing that is literally just a metaphor for trauma and the things you fear about yourself. bryde simultaneously being someone ronan desperately wants to be and completely fears. like. I could go on and on. It makes me so fucking FERAL

#tdt#the dreamer trilogy#maggie stiefvater#jordan hennessy#declan lynch#ronan lynch#matthew lynch#adam parrish#carmen farooq lane#jordeclan#pynch#cdth#mister impossible#call down the hawk#greywaren#original#trc#the raven cycle#trc analysis

884 notes

·

View notes

Text

Declan is described as looking like a combination of Ronan and a polished tailored guy like Gansey or Greenmantle, which in theory makes him like the pinnacle of the type of guys Adam is attracted too. Just don’t tell that to Adam Declan Ronan or Gansey it won’t go over well.

#s speaks#this is important meta analysis not self indulgent at all. it’s not my fault ya’ll don’t read between the lines#adam parrish#decladam#declan lynch#richard gansey#adansey#pynch#ronan lynch#trc#tdt#inspired by that post about how Ianthe is Gideon’s exact type but she’s in denial about it#The Raven cycle#the dreamer trilogy#colin greenmantle

194 notes

·

View notes

Text

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

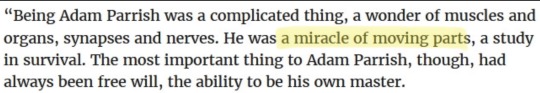

the raven boys / the dream thieves

they’d all forgotten that adam was an animal. love this parallel because

1. being his own master w/ the devil/lucifer’s estrangement from heaven + animal autonomy

2. adam (sometimes) believes he is intrinsically bad but this is only (partially) because he was ‘cast out’ by a higher power!

4. many people’s assumptions about adam are wrong. their pitiful “drawings” of him don’t contain his true complexities, and/or at least he thinks they never can.

3. ronan wants to fuck the devil. okay!

4. coca-cola t-shirt 🥺 the archetype of “adam” in red…

#original#trc#the raven cycle#analysis#the raven boys#the dream thieves#adam parrish#ronan lynch#pynch#maggie stiefvater

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

no because unguibus et rostro. yes it is literally “claws and beak” but it can also be interpreted very loosely as “tooth and nail”. i’m losing my fucking mind over it because it has so many layers. like yes adam and ronan both fought hard individually to be where they were in life, but they had to fight to be together too. but beyond that!! they are the tooth and nail. ronan is the tooth. he’s always associated with fanged animals and imagery (the snake, the shark-nosed bmw). he’s sharp edges, but in the way that broken pottery is. shattered, almost. there’s also a lot of focus on his mouth in other contexts. his smirks, him taking the pills with kavinsky, even just the words that come out of his mouth are all bite. meanwhile adam is the nail. yes everybody in the entirety of henrietta is in love with him, but what’s really fixated on by everyone is his hands. to the point where ronan literally breaks into adam’s car to give him something to make his hands feel better. (ronan’s love languages are something i could talk forever about too, but i’ll save that for a later date.) adam clawed his way to the life that he had in the books, and i think nails are a really good representation of that. yes he’s a little torn up. he’s chipped and bleeding. and in the exact same way that you get dirt under your nails, adam worries about being tainted by henrietta, and that his identity as someone from the rural south needs to be cleaned away before he can be someone of value. in the beginning of the series, he seems to really want to erase his history, and clipping broken fingernails feels like a really good analogy for that. additionally, the whole thing with ronan kissing/sucking adam’s fingers really seals the deal for me. healing each other. ronan’s mouth on adam’s hands. tooth and nail. unguibus et rostro. i’m going insane

#trc meta#the raven cycle#trc#the raven boys#trb#the dream thieves#tdt#blue lily lily blue#bllb#the raven king#trk#pynch#ronan lynch#adam parrish#joseph kavinsky#unguibus et rostro#book meta#meta#book analysis#books#literature#writing#maggie stiefvater#analysis#theory#trc analysis#trc theory#mine#hall of shame

444 notes

·

View notes

Text

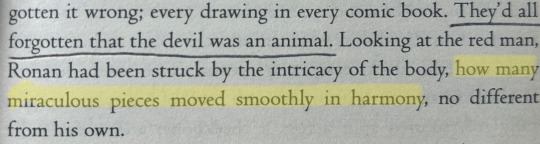

this barbie is quantifying mundane information from a young adult fiction series

#rchl#very fun to run blorbos thru one-way ANOVA w multiple comparisons#if you have an idea for a trc themed spreadsheet or quantitative analysis but don't want to do it. i will lol#trc#trb#the raven cycle#the raven boys#trc data

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

i’m so normal about ronan lynch (he consumes my every waking thought)

#not in a crush way tho#more in a character analysis way#like i want to know everything about him#his story is gutwrenching#ronan lynch#pynch#adam parrish#the raven cycle#trc

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

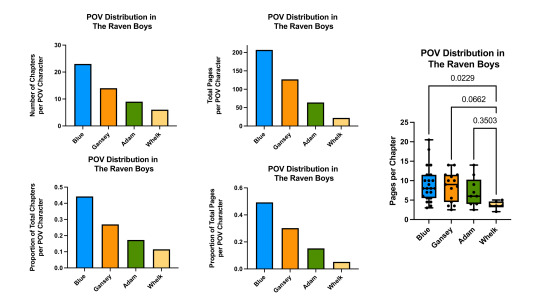

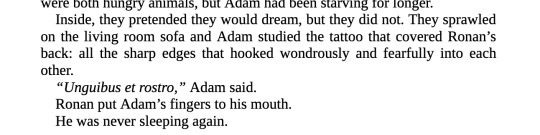

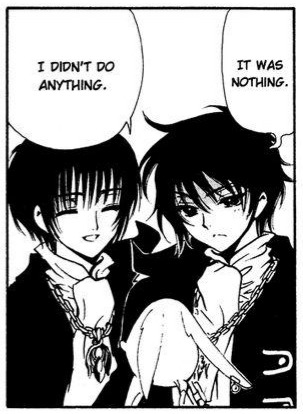

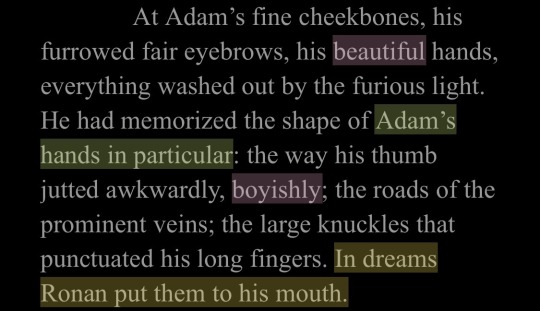

Okay so basically I got to do a presentation about chapter 30 from The Dream Thieves in my Creative Writing class and I got way to carried away writing a full analysis so I thought I'd post it here

I think this passage is so great because it's packed with symbols that completely encapsulate the character of Ronan Lynch. Firstly, we have Ronan’s tattoo, which holds a lot of significance in terms of its literal purpose and what it figuratively represents. We learn here that the literal purpose of the tattoo is to instill fear and intimidation among others. Ronan is a very damaged person, and uses his physical appearance as a warning sign for others to steer clear of him after his father dies. He has a shaved head, a permanent scowl, and most intimidating of all: a tattoo which stretches from the back of his neck all the way down to his waist. His tattoo has a lot of grotesque, frightening imagery in it, which is interesting considering its design is made up of “things from his head.” The fact that the dark imagery portrayed in his tattoo is from his head reveals the struggles and dark things that come out of his own mind. His tattoo is a literal manifestation of Ronan’s inner self portrayed in a scene on his back. He’s quite literally wearing his heart on his sleeve (or on his back rather). It’s also mentioned that Ronan has never been able to see the tattoo fully, because it’s on his back. It can only be seen by others standing behind him, and also, when he’s naked (which is something I’ll come back to later). I think that the placement of his tattoo specifically is a really important metaphor alongside the idea that Ronan’s tattoo represents his whole character and inner self. The fact that Ronan cannot see the whole picture of himself and only “bits and pieces” seems like a large indicator that Ronan doesn’t know fully who he is. In the prologue of The Dream Thieves, it’s stated that Ronan has three secrets, all of different natures; the nature of the second secret being one you keep even from yourself. So essentially, Ronan has a part of himself which he doesn't even truly understand, and I think that this is really accentuated by the fact that he can't see his whole tattoo (his inner self) because it's always behind him. However, others also can’t see the whole tattoo unless he takes his shirt off to show them. (BIG THING FOR LATER!)

In the epilogue of TDT you find out (along with Ronan himself) that he’s in love with one of his best friends, Adam. During this chapter, the reader hasn’t been told yet that Ronan is in love with Adam; mostly because the book follows his point of view, and he doesn’t actually know this about himself yet either. It’s made into a plot twist of sorts in the epilogue, and many readers said that they weren’t aware that it was coming at all. A lot of people felt that Ronan’s crush on Adam came out of nowhere. But if you’re me and love to look WAY too deep into every single line of a book, you’ll know that this isn’t the case at all. This dream is a dead giveaway of Ronan’s feelings. First of all, dreams–especially the way that they’re portrayed in this book–are a look into one’s inner conscience. Your dreams are able to display your deepest feelings and desires, even if you’re not consciously aware of them in real life. Ronan especially is a character who has walls built up, and doesn't verbally communicate how he feels to any other character. He doesn’t even allow himself to examine his own feelings/desires, and has a lack of self-vulnerability and personal emotional intelligence. So in his dreams, his most inner part of himself comes to the forefront of his mind and shows him things he didn’t even know he wanted. To validate this idea, we have the fact that Ronan can fully see his whole tattoo in this dream. His tattoo represents his inner self, and he is finally able to see this part of himself within his dream. The dream begins with Dream Adam tracing his tattoo, and in Latin (which I’ll unpack later) he says,“Scio quid hoc est” which roughly translates to “I know what this is.” Once again, returning to the idea that Ronan’s tattoo is a manifestation of himself, we have Adam physically touching it and telling Ronan he knows what the tattoo means. He understands its whole purpose; why Ronan got it, what it’s really depicting. Dream Adam isn’t intimidated by the tattoo like most people because of its gruesome imagery, but instead he knows that it’s really made up of things from Ronan’s conscience, that it’s a representation of who he is inside. What’s really being portrayed in this scene is Ronan’s desire to be truly known by someone, which is a common theme in the series. The fact that the person shown “knowing” Ronan in his dream is Adam specifically is really important as well. Up until this point, we know that Adam and Ronan are friends, their relationship is shown to be tense and is characterized by squabbles which are resolved by the end of the day. We don’t really know exactly how they feel about each other yet based on their surface level interactions. Therefore, this chapter is extremely important in developing their relationship. We now know partly about how Ronan truly feels about Adam. Not necessarily what their relationship currently is, but what he subconsciously wants it to be. Ronan wants to be known by Adam and believes that he has this capability, since it’s Adam who fills this role in his dream.

In the dream, Dream Adam then transforms into Kavinsky, who’s the antagonist in this installment. Kavinsky is an adrenaline junky who’s presented to have an infatuation with Ronan. He gets him to do crazy things: dangerously drag race in the streets, take questionable dreamt-pills, and throw molotov cocktails at white Mitsubishis. He’s infatuated with Ronan mainly because of Ronan’s outward reputation and appearance, his mutual love for perilous activities, and the fact that they share the supernatural ability to take things out of their dreams. Kavinsky wants someone to enable him; who he can be an enabler to. Kavinsky thinks that they’re one in the same, and that Ronan is an exemplary candidate for a self-destructive partner. In Ronan’s dream, when Adam turns into Kavinsky, Ronan disappears entirely. He becomes only his tattoo, which gets smaller and smaller until it's simply a tiny Celtic knot. The notion that Ronan disappears and that his tattoo (all that’s left of him, a manifestation of his conscience) gets smaller when Kavinsky appears, shows that he literally feels small when he’s with him. Kavinsky belittles Ronan. He misunderstands who he is, and boils him down to his wildness and rash spontaneousness. He quite literally swallows Ronan whole in the dream; he destroys all that he is. Dream Kavinsky tells Ronan in Latin, “Scio quid estis vos'', which roughly translates to “I know what you are.” WOOOOOF. OH, IT'S SO GOOD. I GOT CHILLS. This could have SO many meanings. “I know what you are” could mean that Kavinsky knows that Ronan is a dreamer, just like himself, or it could also mean that he knows Ronan is gay (if we’re revisiting that idea of this dream bringing to the forefront parts of Ronan that he doesn’t know about himself yet). Adam and Kavinsky are complete opposites in Ronan’s dream, and furthermore, his life. The dream versions of the two represent what he wants, versus what he’s settled with. Currently, Ronan doesn’t think that he’s worthy of someone who truly knows and loves him. Instead, he’s resigned himself to a homoerotic unlabeled relationship with Kavinsky—who doesn't actually care about who he is, and only wants someone who he can destroy his life with. The exact phrasing of the things Dream Adam and Kavinsky separately say to Ronan are SO significant. Essentially they’re telling him the same thing: what they think they know about him. It's the words which they use to say this which makes these statements wildly different. Dream Adam says “I know what this is” about Ronan’s tattoo, meaning that he knows Ronan’s inner self. He knows this thing which he can’t normally see all of himself display of terrible things from his own mind. Dream Kavinsky says “I know what you are” which displays his assumption of Ronan’s outer character. It’s a bold assumption and an incorrect one. The difference between Adam and Kavinsky to Ronan, is that Ronan wants Adam because he’s different from himself, and doesn’t want Kavinsky because he’s too similar to him. To an extent, I think Ronan fears Kavinsky because he’s who Ronan would be if he didn’t have Gansey or Adam in his life to keep him sane. Initially, Ronan does like to have someone to let off steam with, but he eventually realizes doesn't want an enabler to ruin his life with. He wants someone like Adam–his polar opposite–to know him, to ground him. He wants to feel alive, and awake.

Another interesting element to this chapter is that Ronan’s dream seems to be erotic in nature; it’s a wet-dream. This is a little jarring for a YA novel, but I personally think eroticsm and sex used in literature as metaphors for conveying relationships and character vulnerability is really beautiful and clever. The significance of it being a sex dream is the fact that Ronan, as previously stated, isn’t someone who verbalizes his love for people. He shows it through physical intimacy and acts of service. Intercourse is literally as close as one can be with another person, and Ronan is completely vulnerable and laid bare in this moment. In it Ronan is naked, which we know because the dream begins with Adam tracing the tattoo all the way down his bare back. Remember, Ronan’s tattoo can only be seen fully when he’s naked, which adds another layer to this. Here it’s assumed that he had allowed Dream Adam to see his tattoo, because he had to have taken off his shirt to see it. Circling back Ronan’s tattoo placement, it’s something that not only can’t be fully seen by himself, but also can’t be fully seen by others unless he decides to strip naked for them. Here he allows Adam to see it and even trace the lines of it down his back. He felt comfortable enough to be vulnerable with Adam like that, and to inspect his whole being. The fact that Kavinsky then appears and the tattoo becomes smaller represents Ronan's uncomfortability with Kavinsky. He didn’t mean for him to see that part of himself and shrinks away in shame until Kavinsky devours the tattoo without permission. It really enforces the idea that Ronan wants and chooses Adam, but Kavinsky forces himself into his life and takes from Ronan without asking. Finally, Ronan awakes from his wet dream “euphoric and ashamed.” This could either be about the fact that it was a sex dream with not one, but other boys, or the confrontation of his true desires. He’s ashamed to admit what he really wants, and doesn’t allow himself to fully comprehend what this dream means. Ronan even thinks that he never wants to sleep again, which really means that he doesn't want his dreams to confront him with his true feelings again. This can tie into the metaphor about Ronan’s sexuality in terms of the fact that he got off to Adam and then Kavinsky, or that he doesn’t want to let his guard down and admit what he truly wants.

It’s now finally time to unpack the use of Latin! Hooray! Throughout the series, we’re shown that Ronan is really flippant about school. He’s constantly on the brink of expulsion from Aglionby because he doesn’t go to any of his classes or do any of the work. However, the one class he has consistent attendance in as well as the highest overall grade is Latin—second to his proficiency in the language is Adam. They’re both in the same class, and are said to be able to almost fully understand and speak perfect Latin. The use of this dead language is a common theme in the series, and almost all of Ronan’s dreams are in latin. There’s an underlying meaning in that alone. A fun tidbit if we’re looking into the meaning of latin phrases we have the imagery of “claws and beak” described about the imagery of Ronan’s tattoo. The latin phrase “Unguibus et rostro” translates to “claws and beak” and is an expression about fighting with everything you have for something you want. It’s idiomatically comparable to phrases like “heart and soul” and “with all one’s strength” (thanks to ravenclawsandbeak on tumblr for sharing this finding with the fans). In the final book in the series, there’s a short chapter which is essentially a call-back to this chapter, and follows the format in which it’s written pretty clearly. However, Ronan is awake this time rather than dreaming.

This chapter is more or less a sex scene between Ronan and Adam, and is essentially the exact opposite to Ronan’s wet dream in TDT. Here, Ronan’s desires are no longer a fantasy that came to him in a dream, he finally has exactly what he’s wanted all along. in which they admit their feelings for each other, which is done indirectly and not through words. The fact that it's through a sex scene is significant because it's showing their intimacy. Intercourse between people is literally as close as two people can get. As a couple, Adam and Ronan rarely verbalize their feelings about each other, and so this intimate act is really them letting down their walls and allowing themselves to be completely vulnerable to each other. Here, we have Adam studying Ronan's tattoo in real life this time, just like in his dream (Something he’s only able to do because Ronan allowed him). He sees all the fine details in its design, and interestingly enough, speaks aloud this latin phrase “Unguibus et rostro” (This also begins a common theme of Ronan and Adam speaking in cryptic latin phrases rather than just actually telling the other of how they feel about each other, but that's a story for another time). This, as everything else does, has multiple meanings; it shows that not only Adam correctly interprets the imagery on tattoo, showing that now he does truly know and understand Ronan’s inner self. But also it reiterates the meaning of this phrase: that Ronan has appropriately fought with all he had for what he wants. He was able to reject Kavinsky and stay true to himself and his principles, and he realized his feelings for Adam, and was able to let his guard down enough to reach out to Adam and let him know how he actually felt about him. And similarly, he allowed Adam to love him back.

So why did Maggie Stiefvater include the chapter in TDT? It completely breaks the flow of the main story, interrupts two other character’s POVs, and comes seemingly out of nowhere. It's not described where Ronan is, who he came to sleep, when it’s happening. It feels as if the placement of this chapter didn’t matter; it could appear anywhere and still have the same effect. My theory? I think that Stiefvater specifically placed this chapter here because she thought it was an appropriate time to learn more about Ronan, and she wanted the chapter to stick out due to shock value. Because it’s at such a seemingly random moment, and its content is brief and strange, it’s a stark outlier from the rest of the chapters. For me, this strategy totally worked. When I think back to this book, this chapter is by far the most memorable one. I remember it almost immediately when I think about any specific line/chapter from this book. Even though the dream seems random and complex, it has so much meaning packed into it about Ronan’s inner conscience and character. Stiefvater wants to reveal all of these things about Ronan previously analyzed without directly telling us.

#trc#the raven cycle#the dream thieves#the raven king#ronan lynch#adam parrish#joseph kavinsky#ronan's dreams are weird and i love them#literary analysis#lit analysis is my passion and so is this book

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

“be dangerous.” BE DANGEROUS??? be dangerous. be. dangerous. be dangerous be dangerous be dangerous be dangerous be dangerous be dangerous be dangerous be dangerous be dangerous be dangerous be dangerous be dangerou-

#does anyone care for an analysis??#my thoughts since reading that one thing maggie posted#I AM INASE#absolutely feral about this line !!!!#ronan lynch#declan lynch#trc#greywaren#tdt#adam parrish#call down the hawk#mister impossible#the raven cycle#blue sargent#richard campbell gansey iii#adam and ronan#the raven boys#blue lily lily blue#henry cheng#pynch#the dream thieves#gangsey#the gangsey#blusey#matthew lynch

256 notes

·

View notes

Text

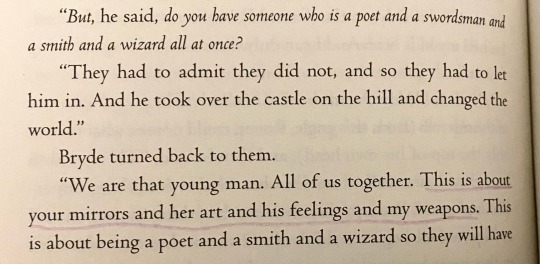

something about this passage. not just bryde’s assertion of feelings as ronan’s dream power, (and art as hennessy’s, despite her thinking she’s worthless at dreaming), but the combination of these specific things, mirrors plus feelings plus art plus weapons. bryde is obsessed with this idea of re-defining reality (possibly to cope with the fact that he himself is not real but that’s another post), and these dream niches he’s listed could all be thought of as the ways each of the dreamer’s chosen method of reality creation, and how that reflects what they want and how they see the world.

rhiannon sees the good in everyone and wants a world where everyone is kind to themselves, so she dreams mirrors that show you the kindest version of reality.

ronan’s reality is created based on feelings - he dreamt matthew because he wanted a brother who showed him the love declan couldn’t, all of his weirdest and worst dreams fuck with feelings in some way, like the dreamt security system, the fact that he’s willing to go through it every day, the dreamt tamquam wheels and how he’s obsessed with adam not texting back, I think deep down what he wants is a world where people are honest about how they feel (even if he would never admit that to himself).

hennessy sees the world through the eyes of an artist, seeing the essence of everything, the story beyond the picture, incorporating emotional truths with physical truths so that through art reality becomes more of itself, and by doing so reaches its potential so that it is also better than its orginal self, and the fact that when she looked in rhiannon’s mirrors she saw jordan, who she believes is the better version of herself, and the lace being associated with feelings that represent what she thinks is the worst of herself, and the worst thing that the lace can do being to see her… it’s like all she wants is a world where being seen is not equated with being bad.

and bryde…. dreams weapons, because his chosen form of creation is destruction. he is a product of the fury in ronan and the fury of nature and the dying ley lines, the collective fury of a world drained of magic. he wants justice, anarchy, a world restored to natural purity, and represents the part of ronan that will do anything to create a world he can belong in. and also wants, probably, a little revenge.

what do all of these have in common? there’s a deep longing for realness, authenticity, belonging. mirrors show you a version of what reality is; art shows you reality’s potential. feelings show you truths you can’t admit to yourself and weapons force you to face them. there’s a constant reckoning between what is vs what is wanted vs what is possible vs what can be made possible by wanting. hope is not just a feeling, it’s a weapon and a paintbrush and a mirror. it destroys and it creates and it reveals.

#I’m sorry it’s been so long since I’ve written an english essay and I miss it. CAN YOU TELL#tdt#trc#the dreamer trilogy#call down the hawk#mister impossible#greywaren#tdt analysis#trc analysis#ronan lynch#jordan hennessy#bryde

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

trc did do nice job at tying in the dog motif to make the gansey family status a bit dehumanizing

“…he had been told he was destined for greatness.

He was bred for it; nobility and purpose coded in both sides of his pedigree.” (raven king prologue)

compared to the barking always mentioned at the trailer park & dog-walking being one of blue's multiple jobs. ronans violence gets lotsa dog imagery, even in-universe.

#i guess trc stands out from other YA because analysis isnt just expected its rewarding. ykwim?#probablyrambles#trc#dog motif#gansey#the raven cycle#the raven king

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

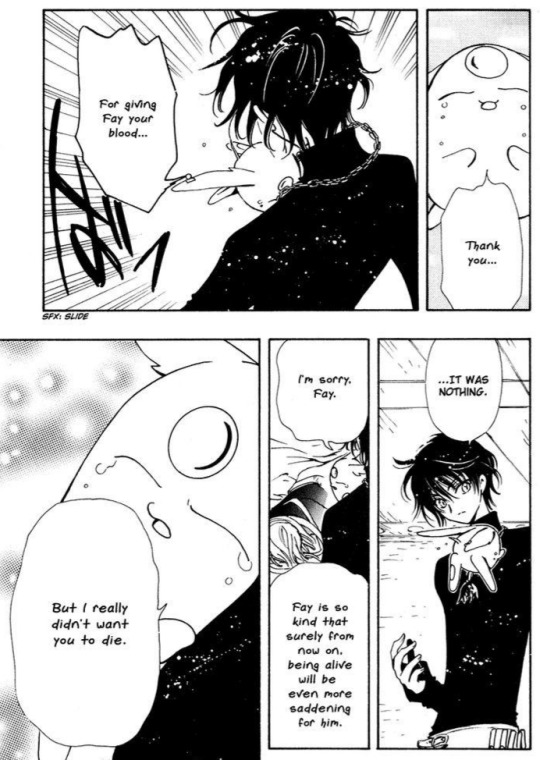

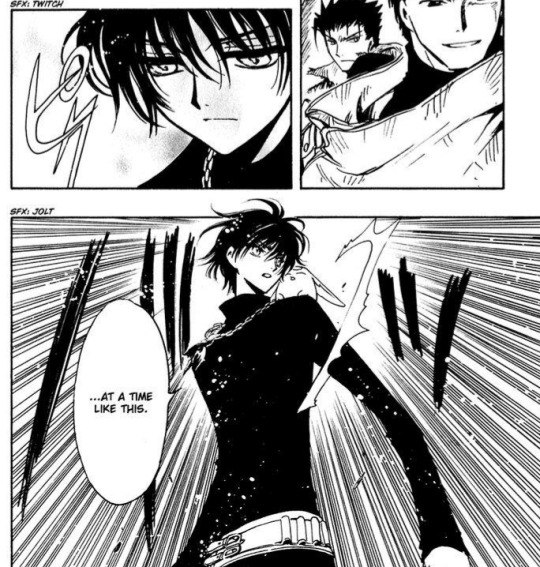

Here I present you canon evidence how TRC Kamui became domesticated:

At first he was moody, feisty and down for the fight. He just wanted his brother back and was scared for their safety probably, but lashed out as result. I mean:

RIP Sayoran, meeting Seishirou was a grave sin of yours since Kamui doesn't vibe with anything that reminds him of that bastard man with fake priest degree. Yes, even if it's fighting style. Very protective, very impolite, very over top. At least he's serving looks while going feral from time to time.

Then everything that can go wrong for main crew goes wrong. Not in Kamui's case howeve, since after 2.5 years Subaru managed to wake up from his princess sleep. About time Subaru, you probably wouldn't need sleep for a year at least now.

Kamui: *is the leader people in acid tokyo universe rely on*

Kamui: Subaru is back let's leave this world RIGHT NOW

You'd think being reunited with his twin would calm Kamui down but nope. He remained sassy.

Yuuko: *explains elaborate plan how to save Fai's life by giving him vampire blood*

Kamui:

Subaru manages to convince him to give in and Fai is saved. And then:

Kamui doesn't know how to react to Mokona's cuteness. He begins loosing some of edginess. He's thrown of loop.

Mokona the therapist broke Kamui out of his casual angst. Everyone could have little bit of Mokona in their lives, it heals. And domesticates. I mean look at Kurogane, first chap he was laughing manically surrounded with ninjas he just killed and bam 5 chaps later he's a father with 2 and half children and soon-to-be magical wizard husband. Ofc Mokona played the role in that.

You'd think Mokona would be on Subaru's shoulder instead since he's an epitome of kindness and gentleness but nope. Mokona knows who needs her domesticating calming powers.

Two things: 1) where did Kamui keep his vamp outfit all this time? Did Kusanagi see bunch black goth clothing at any point and was like "the hell is this??" and Kakyou walked behind and was like "oh, that's Kamui's vampire costume don't touch that, he becomes moody otherwise. What - why? He think he looks cool in it. And yes, shoes have slight heels " 2) I was about to say what good did Fuuma do but then I remembered he gave Sakura a gun. Good for her, she should have a gun more often.

Picture is worth thousand of words and it's all how Kamui transformed from feisty aggressive vamp to this fluffy tsun fruit bat. Thank you Mokona for your hard work and positive healing vibes. We all see that slight blush Kamui.

In conclusion:

#300% serious analysis#how Kamui in trc went from early X Kamui to later X chaps Kamui in merely few chaps#tsubasa chronicle#kamui shirou#mokona modoki#clamp

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

do you get it. do you even understand

cloud cuckoo land, anthony doerr // the raven king, maggie steifvater

#web weaving#the raven cycle#trc#ronan lynch#adam parrish#pynch#cloud cuckoo land#book analysis#the raven king#trk#ccl x trc#trc x ccl#mine

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

i've revised my trb chapter 36 notes and they've somehow expanded to ~15 pages. you can read them here (i've also pasted the text into this post under the cut). the notes don't constitute an essay or produce a coherent thesis but they're a pretty comprehensive list of observations and interpretations i drew from the chapter.

TRB chapter 36 notes (content warning for abuse)

Last updated: 230610

“’The buck stops here,’ Ronan said, pulling up the hand brake. ‘Home shit home.’” This is the first chapter where Adam and Ronan are the only main characters present- their first scene entirely alone, set in the BMW before Adam gets out. I’m thinking about a few things: how differently Ronan and Gansey talk about Adam’s trailer, his parents, his poverty, etc.; how Ronan’s flippant insults and nonchalant offers of help (despite genuine concern) are less alienating to Adam than Gansey’s more openly heartfelt concern, since it’s paired with criticism of Adam’s pride and a tendency to command rather than suggest (full disclosure- I love Gansey and understand his point of view, but it’s clear why his approach upsets Adam more, and I think Ronan, having felt smothered by Declan, is more capable of empathizing with Adam on the matter of refusing help moving out); the recurring theme of cars being a place of refuge and solace for Ronan and how he wishes Adam would stay inside the BMW (even though he knows he won’t). I didn’t verify what I’m about to say so if I remembered incorrectly please let me know, but I’m pretty sure that we see Ronan drive Adam in the BMW to the trailer park twice (in this chapter, and in TRK when Adam scries while Ronan drives [the “wrong devil” scene]). Nobody else drives Adam home (although Gansey repeatedly stops by to pick him up). Gansey is constantly bringing Adam away from the trailer, for good reason (and practical reason too- sometimes they’re just going to class). Ronan brings him back, setting Adam up to confront his life and make decisions to change it. I know someone else has written a tumblr post about Ronan putting Adam in these types of situations and it’s very insightful and I’d love to cite it here (so if you wrote it or know who did, please tell me!). But ultimately this sets up an arc that ends with Adam driving the BMW alone for a final conversation with his parents, in which he can come and go from the trailer independently and in control of his interactions with his parents- the effects of the abuse are not erased, but his character arc has such a trajectory that he’s able to get some closure on his own terms via his hard-won autonomy and healing (the BMW/Ronan has played a key role in establishing both).

“In the dark, the Parrish family’s double-wide was a dreary gray box, two windows illuminated.” The description of the double-wide has gone from pale blue in daytime to an absence of color- things are even more grim. No love, no liveliness. A strong contrast to the home from which they’ve just driven (300 Fox Way, which has a bright blue exterior). The illuminated windows seem like omens or warnings rather than beacons. “Box” implies simplicity, a lack of architecture, a constraining place, a place in which one might be trapped. I’m thinking about how the flat ceiling of a box-like trailer also contrasts with the multi-sloped attic of 300 Fox Way, perhaps symbolizing Blue’s family’s proclamation of Blue’s potential versus Adam’s family’s stifling of his talents, needs, wants, etc.

“It was a comfortable enough arrangement; Adam and Ronan weren’t in a fight at the moment, and both of them were too startled by the day’s events to start a new one.” Not that they don’t get genuinely upset with each other on page (things get heated in BLLB as the development of their relationship becomes more prominent/less subtextual), but I feel like we get told that Adam and Ronan don’t get along but they…usually…do, from our vantage point. When they do have conflict in the first book, it doesn’t seem as heavy/personally directed as when Adam and Gansey fight. I get the sense that a lot of their bickering is routine and low stakes, especially since the passage tells us that the day’s chaos and threat to Gansey’s safety has jostled them out of their typical (mundane?) arguing.

“Adam reached in the back for his messenger bag, the one gift he’d ever permitted Gansey to give him, and only because he didn’t need it.” I remember this sentence being critical to my understanding of Adam’s character the first time I read this series. Adam accepts the one gift he doesn’t need because he could get rid of it and suffer no dire consequences if the friendship ended. He wouldn’t have to rearrange his carefully made plans over a messenger bag if he wanted or needed to give it up at all. There’s no desperate gratitude or a gnawing need to pay back a debt- it’s superficial, not connected to his precarious survival, no implied reliance. There’s also something in here about a bag being used to carry things (burdens?) that I’m trying to tease out into words but haven’t yet. whoreshoecrab also made the brilliant observation that a messenger bag is more of an academic, white collar (and relatively impractical) choice of bag which I think plays into Adam’s willingness to accept something since it doesn’t highlight his desperate need for the bare necessities.

“Another silhouette, distinctly Adam’s father, had joined the first at the window. Adam’s stomach curdled.” We don’t get much information about the relationship between Mr. and Mrs. Parrish (although Adam’s later concern about leaving his father’s gun behind implies that Robert also abuses his wife), but here there’s an implication of a united front against Adam. His stomach going sour is a visceral description of his fear- how terrible to go home to danger rather than safety. This sentence reminds me of one from TDT in one of the Gray Man’s chapters: “The Gray Man’s stomach wrung itself out… His brother had never intended for him to pick up; he merely wanted this: the Gray Man stopping the car, wondering if he was supposed to return the call. Wondering if his brother was going to call back. Untangling the wired threads in his gut.” (TDT, chapter 7), both serving as descriptions of a particularly physiological, visceral fear stemming from abuse.

“He tightened his fingers around the strap of his bag, but he didn’t get out.” Tightening -> builds tension in the narration as Adam braces himself for a confrontation. I mentioned this already, but cars often serve as places of refuge in the series. Ronan goes to wait in the Camaro after his brawl with Declan in TRB chapter 7 and after Calla goes for his neck in TRB chapter 15; Adam lingers in the BMW to delay having to go home in this chapter. Adam joins Ronan in the BMW in TRK in silent solidarity as Ronan grieves.

“’Man, you don’t have to get out here,’ Ronan said. Adam didn’t comment on that; it wasn’t helpful. Instead he asked, ‘Don’t you have homework to do?’ But Ronan, as the inventor of sly remarks, was impervious to them. His smile was ruthless in the glow from the dash. ‘Yes, Parrish. I believe I do.”’ A suggestion, not an order (i.e.. You don’t have to get out here vs. don’t get out here). Adam’s arguments with Gansey are often about how Gansey views/treats Adam; Adam’s arguments with Ronan are often about how Ronan wastes the time he has, the time he could be using for school work, the time Adam wishes he had. He’s genuinely frustrated that Ronan wastes such a precious resource, but the frustration is with a behavior that doesn’t have anything to do with himself (if he doesn’t compare himself to Ronan, which is another can of worms). Adam ignores Ronan’s comment- would he have ignored such a statement from Gansey, or started to argue? Would Gansey have ever phrased it like that? We get more insight into how they interact/communicate; Adam avoids arguing over serious circumstances but is comfortable resorting to banter since he knows there’s no risk of actual offense. There’s also a microscopic bit of dramatic irony here if you’re re-reading since the outcome of the events in this chapter directly lead to Ronan doing his homework in earnest.

“He didn’t like the agitation of his father’s silhouette. But, it was unwise to loiter in the car — especially this car, an undeniably Aglionby car — flaunting his friendships.” This chapter obviously shows Adam’s father’s physically abusive nature but also demonstrates how absolute his effect on Adam is, whether or not he’s actively enacting the abuse. Adam is constantly tuned to his father’s posture and follows a set of rules designed to minimize conflict and harm to himself. For someone running so low on time and sleep, this perpetual monitoring must add an additional layer of exhaustion. There’s no place to hide- to stay safe in the BMW is to potentially worsen his father’s mood, and to go home is to put himself in the path of danger anyway. Re: it being unwise to flaunt friendships: this was also crucial to me understanding Adam and his independence/lonesomeness; because the Parrishes are poor and Adam’s friends are wealthy, and mentioning his friends (which is criticized as flaunting) threatens his father’s insecurity about their poverty, Adam is conditioned to see connection and community as shameful, as a betrayal to his roots (which he is also taught to see as shameful- there is no winning). In the context of his family, he is safer on his own (but in the context of the world, he cannot move forward alone, and this is a lesson he must learn).

“If he shows up for class,” Adam replied, “I think that the reading will be the least of his concerns.” Subtle threat/hint at Adam having zero remorse for Whelk in future chapters

“There was quiet, and then Ronan said, ‘I better go feed the bird.’ But he looked down at the gearshift instead, eyes unfocused. He said, ‘I keep thinking about what would’ve happened if Whelk had shot Gansey today.’ Adam hadn’t let himself dwell on that possibility. Every time his thoughts came close to touching on the near miss, it opened up something dark and sharp edged inside him.” Like Ronan calling Adam “man” and “Parrish,” referring to Chainsaw as “the bird” serves as an example of Ronan keeping his emotional distance, maybe as a way of giving Adam space in a tense situation, maybe to disguise Ronan’s intense emotions. Ronan engages with his concern for Gansey by obsessing over the worst case hypothetical outcomes; Adam (who is typically concerned with planning for all the possible futures) chooses to avoid thinking about such fears at all. As explained in the remainder of the passage (next section), Adam cannot fathom a life without Gansey. This is a clear reminder that Whelk is Adam’s foil, not someone on a parallel path- for Adam, harming Gansey/Gansey’s mortality is too heavy to even think about, much less plot out. Something dark and sharp edged- a hole, a grave? In BLLB when Adam figures out that Gansey is on the St. Mark’s Eve death list, the narration says, “his heart was a grave” (ough). A place to bury impending grief? Or, if you’ve read TD3, this sounds a lot like the Lace, which is to say it sounds a lot like fear and insecurity and terror and being seen and the infinite and abandonment and grief and a lot of other things I haven’t processed yet.

“It was hard to remember what life at Aglionby had been like before Gansey. The distant memories seemed difficult, lonely, more populated with late nights where Adam sat on the steps of the double-wide, blinking tears out of his eyes and wondering why he bothered. He’d been younger then, only a little more than a year ago.” Not only is Adam currently repressing the thought of a life without Gansey, he recurringly prevents himself from crying. Adam alone at Aglionby, struggling to adapt and feeling like a fraud, with no one to believe in him but himself, is incomprehensibly sad. “Lonely” followed by “populated with” makes it seem like the late nights themselves were Adam’s only company.

“His hand worked on the steering wheel; something was frustrating him, but with Ronan, there was no telling if it was still Whelk or something else entirely. “No problem, man. See you tomorrow.” This assessment of Ronan (aside from an incidence of Ronan in motion/his kinetic way of processing emotion), in my opinion, serves to illustrate Adam’s self-perception and paradoxically egocentric and unselfish thought process (he’s self-centered in the sense that he has to prioritize his own needs to survive and is constantly worried about how he acts and feels and interacts with others and looks and on and on but is unselfish in the sense that he doesn’t consider the possibility that Ronan might be frustrated and worried about Adam himself). Ronan is reeling from grieving Noah, worrying about Gansey almost getting killed (which was a pre-existing fear, as we know from chapter 16 and the wasp encounter). And while we’re on the topic of chapter 16 and the aftermath of chapter 33, I hadn’t realized until now that Gansey’s “dual vision” when death is imminent (“Two narratives coexisted in his head. One was the real image: the wasp climbing up the wood, oblivious to his presence. The other was a false image, a possibility: the wasp whirring into the air, finding Gansey’s skin, dipping the stinger into him, Gansey’s allergy making it a deadly weapon.” And “Gansey had that same, detached feeling that he’d had in Monmouth Manufacturing, looking at the wasp. At once he saw the reality: a gun pressed against the skin above his eyebrows, so cold as to feel sharp — and also the possibility: Whelk’s finger pulling back, a bullet burrowing into his skull, death instead of finding a way to get back to Henrietta.”) is perhaps an effect of him living two lives at once, at both dying and surviving twice (but sort of at the same point at the time loop because both deaths and rebirths are temporally linked to Noah’s favor, powered by Cabeswater and the ley line). ????????????????

“With a sigh, Adam climbed out. He knocked on the top of the BMW, and Ronan pulled slowly away. Above him, the stars were brutal and clear.” Who else notably sighs? Noah, another target of physical violence. Ronan is slow, reluctant to leave. Over the next few pages (as Robert berates Adam and accuses him of lying) Ronan continues to slowly leave the driveway because Adam can still see his break lights (antithetical to a stereotypical Ronan response- speeding off recklessly). The brutal and clear stars- perhaps an acceptance of the inevitable cruelty he is walking into? Adam feels destined or cursed to suffer, maybe as if fate, is cold and uncaring. (but does he believe in fate? Evidence in TDT chapter 8 says yes, if not literal fate but a general doomed-by-your-origin/bloodline sentiment, although he also persistently rewrites his narrative and seeks autonomy in his own life, so I don’t think there’s a clear answer. If anything, if he does believe in fate, he sees it as mutable and probably something not named fate at all). I think it’s also notable that the stars are a source of calming comfort to Blue, rather than harsh and distant observers of her struggles. “The stars were brutal and clear” always reminds me of Javert’s Suicide from Les Miserables: I am reaching but I fall/ And the stars are black and cold/ As I stare into the void/ Of a world that cannot hold.

“Hi, Dad,” Adam said. “Don’t ‘hi, dad’ me,” his father replied. He was already revved up. He smelled like cigarettes, although he didn’t smoke. “Come home at midnight. Trying to hide from your lies?” Adam graciously attempts civility; Robert eschews all pretense of acting like any sort of father at all. He’s already agitated, by Adam breaking curfew (which he’s broken for good reason, though Robert doesn’t and can’t know this) or by anything else in the world- his anger is out of Adam’s control. We’ve recently learned Adam does not like to be accused of lying from his encounter with Declan (TRB, 31). The cigarette smell on an adult non-smoker is probably indicative of the company they keep- co-workers? Friends, if he has them? An affair if Adam’s mom doesn’t smoke? The midnight curfew is surely a measure of control rather than care, and is relevant to interpretation of Adam’s constant meticulously meted out aliquots of time (for school, for work, for friends, for sleep) and deep envy for/resentment of those that have time and waste it- not even his own time exists outside the shadow of his father’s fist.

“Adam’s knees were slowly liquefying. He did his best to keep most of his Aglionby life hidden from his father, and he could think of several things about himself and his life that wouldn’t please Robert Parrish. The fact that he didn’t know precisely what had been found was agonizing. He couldn’t meet his father’s eyes.” Emphasizes Adam’s need to always be hiding, keeping secrets, protecting the truth. Ronan is also familiar with the burden of keeping secrets in the name of safety. More description of the physical impact of abuse on Adam (in addition to the actual physical abuse- here I’m referencing the physical manifestations of fear and dread). I’m really interested in Adam’s relationship to his body throughout the series (and I’d have to dig up some other notes to elaborate but his POV chapters often pay acute detail to physical sensations, he dissociates on a number of occasions, his sacrifice of his hands and eyes and ongoing struggle for autonomy on physical and psychological levels especially as the unmaker/demon gains access to his hands and eyes, his healing occurring metaphorically via ley line work/outside of his own body, being alive because he bleeds, perhaps positing his awakening in BLLB as a reintegration of his mind and body after that pivotal scrying scene, etc. I would LOVE to discuss this more but I think I to collect my thoughts or the input from someone else on which to reflect- but this is probably the foundation of a legitimate essay imo). The liquifying sensation intimates a dissolution of the body, or the loss of restrained solidity and form, an unwilling spilling out of his tightly rehearsed outward projections. And finally, not knowing what his father found = lack of control = lack of strategy to defuse the conflict and protect himself.

“Robert Parrish grabbed Adam’s collar, forcing his chin up.” This is a repeated gesture in this chapter: a proprietary, controlling action, forcing Adam to make eye contact he’s trying to evade.

“Think fast, Adam. What does he need to hear?” Adam ends up carrying the burden of resolving the abuse inflicted on him, as if it’s his responsibility and not just a deescalating survival tactic. In TRB chapter 32, Blue muses that Adam isn’t often lost for words- but here, he’s scrabbling for words (he’s too panicked for his words/intellect to cooperate). This is another example of Adam’s solution oriented nature (the mechanic, the scientist)- here is a problem; how do I solve it?

“His father drew Adam’s face a bare inch from his, so that Adam could feel the words as well as hear them. ‘You lied to your mother about how much you made.’ ‘I didn’t lie.’ “Do not look in my face and lie to me!’ his father shouted.” This is one of the more visceral, tactile chapters in the book, with the narration appealing to sensation to convey the intensity of the conflict. The physical nature of the scene also highlights the running theme of Adam’s relationship to his body- how it’s integral to his survival but also how he bargains it away and how it betrays him, the duality of mind and body, etc. I’m remembering that in chapter 31, Adam is highly displeased to be accused by Declan of lying. And not that it really matters, but I wonder if Robert not originally realizing how much money Adam has to accumulate in order to cover the remainder of his tuition is due to a) a lie by omission or b) him simply not listening to Adam’s needs in the first place. Robert also keeps invoking Adam’s mother as she stands idly by, perhaps to emphasize that everyone is against Adam, as if Adam alone is in the wrong here. It’s also interesting that the yelling here is italicized rather than capitalized. I don’t think the books are entirely consistent about this, but I believe we see capitalized yelling from Maura, Neeve, and Jesse, at least. Because the characters’ internal monologues are also italicized, we get a visual representation of how Adam’s parents’ cruel statements worm their way into his own self-talk and therefore self-esteem, self-perception, and reflexive victim blaming (Adam later muses that he has some sort of Stockholm syndrome). The italics in external dialogue and internal monologue collectively simulate abuse survivors’ internalization of abusive rhetoric against themselves. It’s also a little impressive how quickly a knot forms in my stomach at hearing a father say the phrase “your mother.” Has anything good ever followed that phrase?

“When his father’s hand hit his cheek, it was more sound than feeling: a pop like a distant hammer hitting a nail. Adam scrambled for balance, but his foot missed the edge of the stair and his father let him fall.” I’m thinking about hands as tools used as weapons (recurring knife motif in the books, especially in TDT, and how Adam works with his hands, offers up his hands to Cabeswater and in the process the demon uses his hands to nearly kill Ronan). Previously, sound and feeling converged; here, they diverge; Adam is possibly dissociated from the violence to some extent (like a distant hammer, more sound than feeling, etc. … a hammer is also a tool that could be used as a weapon). Adam is literally scrambling for balance here (but also does so figuratively at all times and is often quite successful at maintaining his tightly orchestrated and exhausting equilibrium). The precise nature of Adam’s fall here is brutal- the hit doesn’t make him fall, but it knocks him off balance and the subsequent misstep makes him fall, which his father makes no effort to prevent- the abuse not only aggression but neglect, which is to say control in both positive and negative (not good and bad, but additive and subtractive/maliciously neutral) ways.

“When the side of Adam’s head hit the railing, it was a catastrophe of light. He was aware in a single, exploded moment of how many colors combined to make white.” The prose... The pain is absolute, infinite, world-ending. A railing is a safety feature; a parent is obligated to prioritize their child’s safety. Adam’s injury involving the railing is a testament to his parents’ failure to consider his safety at all. When Adam comes to on the ground, his face, especially his mouth, is “caked with dust” (which frequently appears when Adam expresses shame about his roots); I take the dust as a symbol for a dearth of love given that water repeatedly stands in for love and longing. It’s also a reference to Adam from the Bible being made of the earth. I think his mouth being mentioned in particular references his usual ability to talk his way out of scrutiny and concern or hold his own in arguments, but in the trailer park, his words don’t work as weapons.

“Adam had to put together the mechanics of breathing, of opening his eyes, of breathing again.” A bit of a symbolic rebirth moment, coming back to life. Similar sentiment: “a miracle of moving parts, a study in survival.” My original notes for this chapter said, “I do think this could have been revised though- ‘breathing’ is repeated but not rhythmically or frequently enough (in my opinion) to actually simulate the act of deliberately inhaling and exhaling to self-regulate.” But as I’m re-reading, I understand the choice better. It emphasizes that to live, you must breathe, and breathe again, (and this is relentless), which in turn emphasizes the labor Adam puts in to take yet another breath, to keep going (but the effort to breathe is so great that it’s impossible to consider anything past this breath and the next). Maybe it’s not meant to be a cycle but a Sisyphean climb. Adam has to choose his path forward over and over again.

In Adam’s head: “Just go, Ronan.” He thinks this as he’s rising to his feet after his head hits the railing and sees Ronan’s brake lights go on. The light (Adam indirectly associates Ronan with light multiple times in the text) should be a symbol of hope, but Adam is both too proud and too ashamed to want to hope/accept Ronan stepping in on his behalf. Is this the first time someone not-Parrish has observed the abuse first hand and not just lingering evidence of it? Ronan becoming a direct witness is a line they can’t uncross, a truth Ronan can’t un-know.

“’You’re not playing that game!’ Robert Parrish snapped. ‘I’m not going to stop talking about this just because you threw yourself on the ground. I know when you’re faking, Adam. I’m not a fool. I can’t believe you’d make this kind of money and throw it away on that damn school! All of those times you’ve heard us talking about the power bill, the phone?’” There’s just so much awful here- the victim blaming, the immediate trivialization of Adam’s injury, the devaluation of Adam’s education and opportunity for freedom, and the guilt-tripping over financial burdens a child shouldn’t have to cover, the implication that Adam is running some sort of con, etc.

“His father was far from done. Adam could see it in the way he pushed off his feet with every step down the stairs, from the coil in his body. Adam drew his elbows into his body, ducking his head, willing his ears to clear. What he needed to do was put himself in his father’s head, to imagine what he had to say to defuse this situation.” Keen observation of body language, pattern recognition, (and conscious use of empathy – understanding his father’s thoughts to protect himself). We see these behaviors from Adam in a variety of contexts outside his household; his survival tactics have become ingrained, and while they keep him safe and probably make him a better student too, what is the cost? Exhaustion, mistrust, hypervigilance, repression, isolation. Defusing the situation is what Gansey references back in chapter 7- Adam keeping things quiet.

“But he couldn’t think. His thoughts crashed explosively across the dirt in front of him, in time with the rhythm of his heart. His left ear screamed at him. It was so hot that it felt wet.” Re: previous discussion of mind/body duality, dissociation, etc. his thoughts feeling like they’re outside his body in a dynamic/describable way, the distinction between his ear and himself and the pain transmitted between them, etc. An inability to think as a critical loss given his reliance on his perceptive and intelligent nature.