#tatenokai

Photo

#yukio mishima#japanese author#japanese literature#mishima yukio#literature#author#tatenokai#shield society

103 notes

·

View notes

Photo

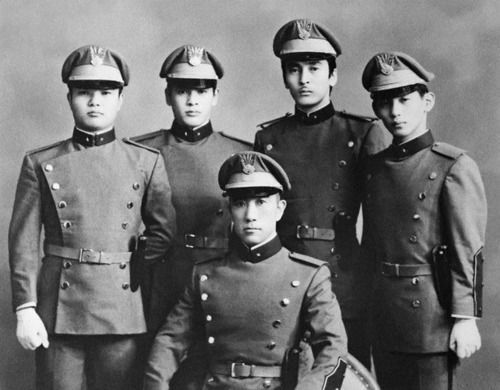

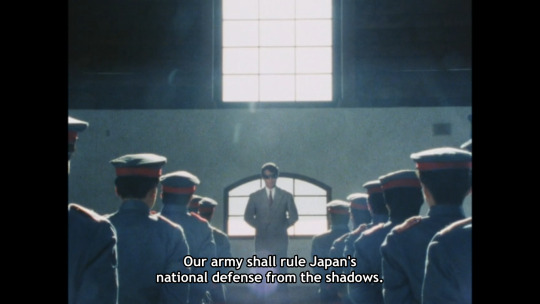

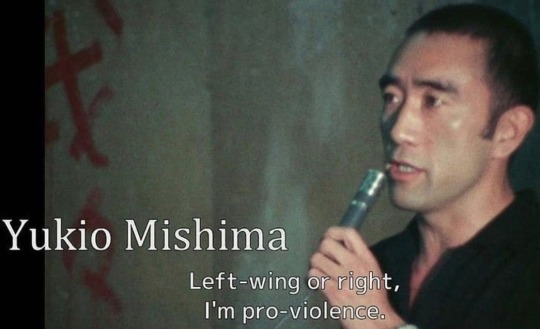

11.25 Jiketsu no Hi: Mishima Yukio to Wakamonotachi (2012)

#film photography#movie photography#cinematography#yukio mishima#mishima#tatenokai#shield society#japan#uniform#nationalism

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kimitake Hiraoka was the sacrificed and the character he invented and lived in, Yukio Mishima, was the sacrificer. The moment the sword entered the belly, the two became one and the beheading is the sacrifice that was required by Bataille’s Acéphale.

“The Victim, Sacred and Cursed

The victim is a surplus taken from the mass of useful wealth. And he can only be withdrawn from it in order to be consumed profitlessly, and therefore utterly destroyed. Once chosen, he is the accursed share, destined for violent consumption. But the curse tears him away from the order of things; it gives him a recognizable figure, which now radiates intimacy, anguish, the profundity of living beings.

Nothing is more striking than the attention that is lavished on him. Being a thing, he cannot truly be withdrawn from the real order, which binds him, unless destruction rids him of his "thinghood," eliminating his usefulness once and for all. As soon as he is consecrated and during the time between the consecration and death, he enters into the closeness of the sacrificers and participates in their consumptions: He is one of their own and in the festival in which he will perish, he sings, dances and enjoys all the pleasures with them. There is no more servility in him; he can even receive arms and fight. He is lost in the immense confusion of the festival. And that is precisely his undoing.

The victim will be the only one in fact to leave the real order entirely, for he alone is carried along to the end by the movement of the festival. The sacrificer is divine only with reservations. The future is heavily reserved in him; the future is the weight that he bears as a thing. The official theologians whose tradition Sahagún collected were well aware of this, for they placed the voluntary sacrifice of Nanauatzin above the others, praised warriors for being consumed by the gods, and gave divinity the meaning of consump-tion. We cannot know to what extent the victims of Mexico accepted their fate. It may be that in a sense certain of them "considered it an honor" to be offered to the gods. But their immolation was not voluntary. Moreover, it is clear that, from the time of Sahagún's informants, these death orgies were tolerated because they impressed foreigners. The Mexicans immolated children that were chosen from among their own. But severe penalties had to be decreed against those who walked away from their procession when they went up to the altars. Sacrifice comprises a mixture of anguish and frenzy. The frenzy is more powerful than the anguish, but only providing its effects are diverted to the exterior, onto a foreign prisoner. It suffices for the sacrificer to give up the wealth that the victim could have been for him.

This understandable lack of rigor does not, however, change the meaning of the ritual. The only valid excess was one that went beyond the bounds, and one whose consumption appeared worthy of the gods. This was the price men paid to escape their downfall and remove the weight introduced in them by the avarice and cold calculation of the real order.” - Georges Bataille, ‘The Accursed Share: An Essay on General Economy’ (1949) [p. 59 - 61]

#bataille#georges bataille#mishima#yukio mishima#sacrifice#accursed share#acephale#acéphale#tatenokai#general economy#general economics#aztecs

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

"And them kendo boys? That's my motherfucking set, boy"

~ Yukio Mishima

Photo: Yukio Mishima posing with his private militia of twinks

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I THINK THEY ARE TATENOKAI REFENCE frfrfr

(Fake Tatenokai in Shoujo Commando Izumi)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Los últimos minutos de Mishima antes de hacerse el 'harakiri' en directo: «Espere y verá lo que hago»

Ahora están atrincherados en el despacho del Estado Mayor. Parece que han hecho prisionero al general Kanetoshi Mashita».

Pocos minutos después, las cámaras de televisión enfocan el gran patio del palacio rodeado de cuarteles. Se ven soldados que corren de un lado a otro y se oyen órdenes gritadas con rabia. En el cielo aparecen los helicópteros de la Policía y de los medios de comunicación. «Atenazados por la sorpresa, millones de japoneses se preguntan qué va a ocurrir, pues todos conocen la Tatenokai, formada por hombres que todavía no se han resignado a la pérdida de los valores tradicionales tras la derrota de Japón en la Segunda Guerra Mundial», informaba ABC poco después, en un artículo titulado ‘El harakiri como protesta y desengaño’.

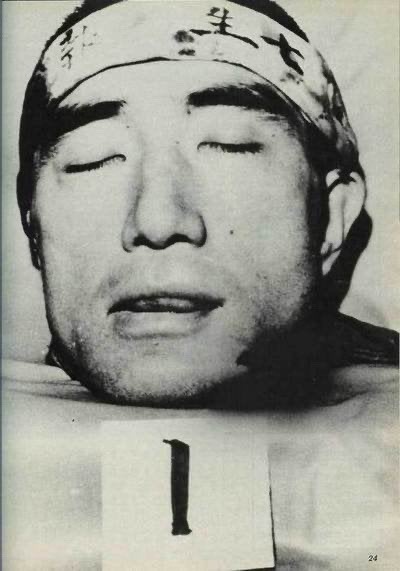

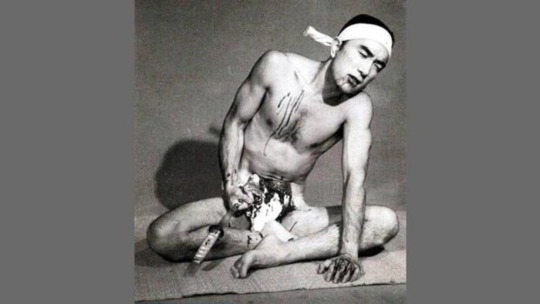

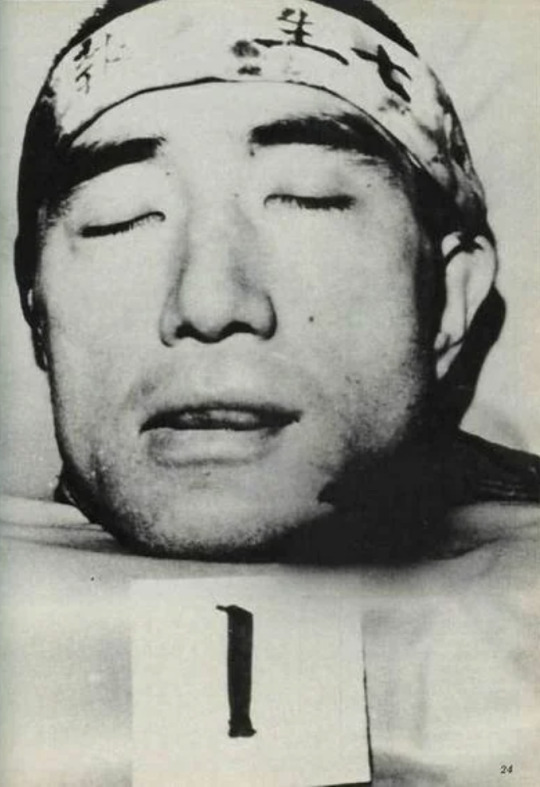

Mishima, simulando su muerte por 'harakiri', en una película.

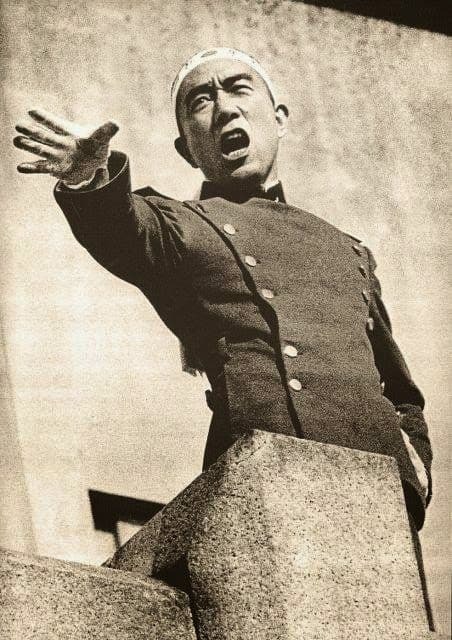

Pero, ¿qué quería ese día? Mishima cercó con barricadas el despacho y ató al comandante a su silla. Con un manifiesto preparado y pancartas que enumeraban sus peticiones, el escritor salió al balcón para dirigirse a los soldados reunidos en el patio. Viste el uniforme escarlata que la Tatenokai solía usar para los desfiles y la banda blanca de la meditación y el sacrificio en la cabeza. Su discurso pretendía inspirarlos para que dieran un golpe de Estado y restituyeran al emperador, pero no logró hacerse oír y desapareció.

El relato que hizo este diario de lo que ocurrió a continuación es escalofriante:

«La terraza permanece desierta. El helicóptero del diario ‘Asahi-Shinbun’ baja en picado hacia el patio en una acrobacia y un fotógrafo apunta con el teleobjetivo. Dentro de pocas horas, en las ediciones especiales de los periódicos se sabrá que Mishima ha firmado su protesta con sangre. Se ha vuelto frente al general prisionero, se ha arrodillado y se ha quitado la chaqueta, quedando con el dorso desnudo. El lugarteniente Masakatsu Morita le ha presentado la más corta de sus espadas. Mishima ha elevado los ojos al cielo durante un instante, se ha clavado la hoja en el vientre, desgarrándolo de abajo arriba, con una frialdad alucinante».

#Los últimos minutos de Mishima antes de hacerse el 'harakiri' en directo: «Espere y verá lo que hago»#¿Esta es la imagen y algunos datos (O no) la “Historia” la pones tú? ¡La tuya! ¿Lo harás...?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bunuh Diri

25 November 1970. Markas besar militer, Ichigaya, Tokyo. Yukio Mishima, pengarang sohor itu, menyiapkan ritual yang menurutnya -dan pengikutnya- heroik. Bunuh diri.

Dibungkus seragam Tatenokai, ormas paramiliter yang dia dirikan, wajahnya tenang menghadapi menit-menit terakhir hidupnya. Segelintir pengikut taatnya berdiri bersamanya di balkon. Kecuali Mishima, mungkin napas pengikutnya yang rata-rata masih muda memburu. Campur aduk antara adrenalin yang buncah dan pertanyaan apakah yang akan terjadi dalam hitungan menit ke depan sesuatu yang perlu.

Bagi Mishima, bunuh dirinya adalah puncak literasi. Kata-kata tidak lagi cukup untuk menggambarkan dekadensi Jepang pasca perang. Dorongan untuk kembali pada masa kejayaan kekaiasaran hanya dapat disiarkan dengan laku. Laku bunuh diri.

Di balkon, Mishima menyampaikan pidato terakhirnya dengan berapi-api. Dia mengolok-olok Jepang pasca perang dunia yang, meskipun terasa sejahtera secara ekonomi, sejatinya telah berjarak dengan nilai-nilai paling fundamentalnya. Kemunafikan merajalela. Politik tidak lebih dari arena kaum munafik yang memamerkan kontradiksi ujaran dan laku. Mimpi kejayaan sebuah bangsa yang dipatri ratusan tahun direduksi sikap membebek terhadap bangsa lain.

Di lapangan Ichigaya, ratusan tentara berpangkat rendah menyaksikan Mishima menyemburkan kata-kata. Kebanyakan dari mereka memandang sinis dan sesekali terkekeh sambil ditingkahi cibiran. Tentu mereka kebanyakan tidak peduli bahkan paham maksud Mishima. Tentara-tentara yang disinggung dalam pidatonya hanya sekadar "tentara bayaran" Amerika.

Menyelesaikan pidatonya, dari balkon, Mishima menarik diri ke ruangan komandan. Seorang jenderal telah disekap olehnya dan pengikutnya. Ini adalah suaka terakhirnya dari hiruk-pikuk kerendahan peradaban Jepang sebagai bangsa pecundang yang dikangkangi bangsa lain setelah kalah perang.

Dengan tenang dia menanggalkan seragamnya. Tubuhnya adalah kanvas disiplin bushido bertahun-tahun tentang olah tubuh dan luka hasil pergulatan intens yang nyata dan fiktif. Hari itu, dia persembahkan penuh tubuhnya sebagai altar dewa-dewa dan kelangsungan tradisi kehormatan kuno.

Digenggamnya tanto, pedang pendek yang hanya boleh dimiliki kelas samurai dan bangsawan itu. Kilatan tanto terefleksi dalam kedua lensa matanya yang kini ujung dan perutnya telah bertemu. Dalam sebuah gerakan nan anggun, tanto tadi berubah menjadi alat untuk mengoyak perutnya. Sebuah kilmaks dari sandiwara yang begitu tekun dipersiapkannya sejak lama.

Masakatsu Morita, salah satu murid ideologisnya, maju untuk membantu Mishima memastikan laku penghabisannya tak bercela. Morita mengayunkan pedang, mengarah ke batang leher Mishima. Perut yang koyak dan kepala yang tercerabut adalah pasase terakhir dari karya terbaik yang dengan gamblang terus tepatri dalam otak sang pengarang.

Selesai. Tubuh tak bernyawa dan kepala yang cerai, teronggok di tatami yang berlumuran darah. Sebuah epilog dari karya terakhir Mishima yang mungkin hingga saat ini tetap dianggap deklarasi heroisme terbaik bagi pengikutnya. Barangkali tidak seheroik itu. Mishima, seperti kebanyakan mereka yang bunuh diri, sama-sama menyerah. Mishima menyerah pada kejahilan yang mencemari peradaban tanah air yang begitu dicintainya dengan buta. Yang lain dengan alasan yang begitu personalnya.

0 notes

Text

I'm kind of used to seeing odd things here, but I was not prepared to see an erotic photographic depiction of the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian —

— where the model was Yukio Mishima, Japanese novelist and playwright.

I mean, I'm not criticizing erotic photographic depictions of the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian! It's just the fact that the other part of Mishima's bio is that he founded and led a right-wing militia, the Tatenokai, which in 1970 tried to end democracy in Japan by triggering a military coup. (It didn't do it very well; Mishima basically took a JSDF commandant hostage, made a speech, got laughed at, and killed himself, but I don't think we have to only look askance at successful fascists.)

0 notes

Text

#yukio mishima#japan#tatenokai#nobel prize#confessions of a mask#traditionalism#samurai#kokutai#seppuku#emperor#japanese empire

110 notes

·

View notes

Photo

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Il 25 novembre 1970, presso il quartier generale della guarnigione militare di Ichigaya, nel cuore di Tokio, Yukio Mishima compie l’atto finale della sua esistenza terrena. Dopo aver “regolato” […] ogni pendenza umana […] Mishima si incontra davanti alla sua residenza con quattro membri della “Società degli Scudi” (”Tatenokai”), appositamente prescelti per partecipare all’evento.

Il gruppo viene ricevuto dal generale Masuda Kanetoshi, comandante dell’Armata Orientale, al quale a un certo punto Mishima si offre di mostrare la spada che porta con sé, un raro oggetto di valore opera di un rinomato maestro spadaio. Il generale constata con disappunto che la lama, contrariamente a quanto prevede la legge, è regolarmente affilata e funzionante, ma viene subito immobilizzato e legato ad una sedia, mentre le porte di accesso al suo ufficio vengono bloccate. E’ richiesta, sotto la minaccia della vita dell’ostaggio, l’adunata entro mezzogiorno di tutte le reclute nel cortile della caserma, a cui si aggiungeranno anche una quarantina di membri della “Società degli Scudi” […]. Il programma prevede un discorso di Mishima della durata di circa mezzora, che i soldati dovranno ascoltare in silenzio, a cui seguirà una tregua di quaranta minuti circa durante la quale non si tenterà nessuna azione ostile contro il gruppo. Con la fronte fasciata dalla “hackimaki”, per contenere il mentale e favorire la concentrazione, Mishima dovrebbe dare lettura del manifesto della Società degli Scudi […]. Ma, di fatto, egli riesce a parlare per soli cinque minuti, fra il frastuono degli elicotteri che volteggiano sul posto e l’urlo delle sirene. Mentre gli ottocento uomini appositamente radunati, invece di ascoltarlo lo deridono e lo insultano. Mishima, preso atto della situazione, si ritira negli uffici del generale Masuda e, dopo avere augurato “Lunga vita alla Maestà Imperiale”, dà inizio al suicidio rituale per sventramento e decapitazione.

[…]

Lo scrittore giapponese sembrava aver’ curato ogni minimo dettaglio del suo gesto, senza lasciare nulla al caso […]. Ma, ciò nonostante, ha dovuto fare i conti con la realtà esterna, incapace di seguirlo sul sentiero dei valori e degli alti ideali che avrebbero potuto ridare dignità e significato all’esistenza del Sol Levante, devastata dal cancro democratico.

Quel male incurabile […] coi suoi cataclismi economici e finanziari, con le sue devastazioni psichiche e spirituali, con i suoi colossali fallimenti politici e con la sua definitiva caratterizzazione come ottusa dittatura del pensiero unico. Quella religione democratica che, come ogni religione che si rispetti, ha un suo decalogo (i diritti dell’uomo), hai i suoi officianti (le pseudo autorità morali che decidono cos’è bene e cos’è male), le sue liturgie (cortei e manifestazioni al posto delle processioni), i suoi peccati capitali (razzismo, intolleranza, discriminazione), un suo Verbo (nessuna libertà per i nemici della libertà). Quel paradiso realizzato in terra che ha prodotto l’individualismo totalitario, la cultura della morte, la tirannia consumistica e la polizia del pensiero, e per diffondere il quale le orde democratiche sono passate come un acido corrosivo, sradicando ogni traccia di società organica e lasciando sul terreno le macerie di un mondo distrutto e ridotto a poltiglia informe ed invivibile.” (”Heliodromos”, n.20-21, 2008)

#Yukio Mishima#Mishima#tradizionalismo#frasi#pensieri#tradizione#Giappone#frasi tumblr#Tatenokai#Società degli scudi

5 notes

·

View notes

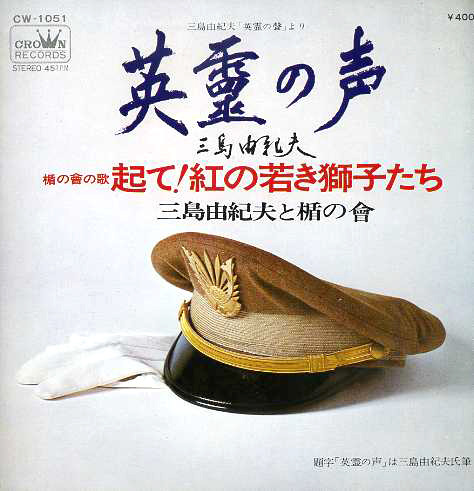

Photo

#yukio mishima#tatenokai#shield society#楯の会#ARISE YOUNG LIONS#he and his little army even released a soundtrack lmao#dai nippon gothic#dainippongothic

291 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yukio Mishima in winter Tatenokai uniform

403 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

“However, in what may be a truly occult and hidden sub-current of mystical theory and practice are mysticisms of radical Embodiment, anti-extasis. Mysticisms which reject the flight of the soul to some ‘eternal unity’. The dejection of the physicality as somehow lesser-than and the search for the Absolute elsewhere, anywhere, other than the pure corporality of flesh, muscle, and bone.

One of the most radical articulations of such a mystical encounter with the Absolute through pure embodiment was articulated by one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century, Yukio Mishima. In his 1968 essay, Sun & Steel (Taiyō to Tetsu), Mishima would expound on this encounter with the Absolute through the careful cultivation of his physical body through weight lifting, its fruition in the tragic ideal of communal, erotic suffering, and the necessity of death as the culmination of the height of this aesthetic, mystical experience.

Of course, viewing his own essay in light of his death through ritual suicide following a failed coup attempt only two years after the publication of the essay only further deepens and reveals its profound gravity as a statement of Mishima’s commitments to those very ideals. Ideals which remain controversial, even shocking, today, over fifty years later.

(…)

Sun & Steel is a work of mysticism I would argue. A mysticism very nearly unique in the history of mysticism itself. A mysticism which not only rejects words and thoughts (which many mysticisms do. That’s just apophatic mysticism), but it’s what he embraces. It’s one that embraces radical physicality as cultivated by tremendous focus on the cultivation of the muscular physique. It’s a true mysticism of flesh.

Mishima’s experience in the upper air, while profoundly recorded in Sun & Steel, were clearly…clearly not enough for him, however. Even such a limit experience was not and could not be the culmination of pure Solar embodiment. Mishima transformed himself into a work of art, his physical body became a work of art, and like all works of art they must be curated to be properly exhibited and thus appreciated. But this work of art was to prove truly ephemeral because, remember, on Mishima’s reasoning it must come to its aesthetic apex precisely in annihilation.

Like many others, I suspect that Mishima’s attempted coup with members of his militia, the Tatenokai or Shield Society, was him simply and very finely curating that very annihilation, that heroic death that he had searched out. Thus, sun and night, steel and words, culminated in a final day whereby Yukio Mishima, having neatly concluded the Nocturnal words of his Sea of Fertility tetralogy, transformed himself into a Solar, headless god and a Cephalus. That despite the sounds of jeering soldiers and, frankly, botched attempt at seppuku. Reality just always impedes upon even the most careful curation in the end.

As I said, Mishima’s Sun & Steel is a fascinating and, frankly, at times terrifying glimpse into not only the development of one of the most important literary figures of the twentieth century, but also an insight into a radical, self-described anti-Platonic mysticism, whereby the Absolute is experienced precisely and only through the development of Embodiment and not just through Embodiment, but the deliberate cultivation of the Embodiment through years of difficult and painful training, only to have it culminate in its intentional annihilation as pure aesthesis.

Now, I’m certainly not arguing that we should in any way emulate Mishima, but as he is appreciated in the world of literature, I think Sun & Steel must come to be appreciated equally as a work of philosophy and as a work of mysticism. In fact, a work of mysticism that has very little in the way of parallels. And in that way, it’s certainly worthy of attention by scholars and practitioners of mysticism.”

“The opposition between the categories of sacred and profane shapes Bataille’s thought, and in his treatment of any subject, associations are readily found that link each new pair to these constellations of sacred and profane things.

The reason Bataille’s philosophy is only ever almost systematic is that while some of the binary pairs he thinks about seem to stand fast, each part of the pair remaining perfectly distinct from its opposite, there are other pairs in which the two parts appear to fuse together, switch places, or flicker in and out of one another.

Contradictory meetings and simultaneities pervade Bataille’s work, apparently irreconcilable ideas are rendered indistinguishable; death and birth become one and the same, the life-giving sun becomes an outpouring of effluence, and rampant growth becomes explosive destruction.

The sacred is, loosely speaking, the realm of things that approach the impossible. It consists of extremity, rapture, and experiences that strain at the boundaries of human consciousness, even momentarily stretching beyond them. Inner Experience ties this world of near-impossible experiences to the mystical tradition: the accounts of religious experiences that defy ordinary categorization and description – that evade assimilation into the profane world of the everyday (Bataille places particular emphasis on the writings of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite).

For Bataille, the mystical experience aspires towards an impossible state: identification with ‘everything’. For the Christian mystic this ‘everything’ is God, but the aspiration is impossible, Bataille writes: ‘We have in fact only two certainties in this world-that we are not everything and that we will die.’ (Inner Experience, 1943)

Here, however, a characteristic twisting together of opposites occurs. Though Bataille links this impossible continuity with the ‘entirety of being’ to the sacred, he describes another kind of mystical experience that results when we recognize the impossibility of our desire for continuity at the same time as we acknowledge our mortality. This experience diverges the mystical tradition, which Bataille begins Inner Experience by critiquing, in that it is not ‘confessional’: it does not lay claim to being an experience of something, or of God, but rather to pure experience, alive, where the sentence ‘I saw God’ is deadening.

(…)

The resultant experience, that which attends the realization the impossibility of continuity with all the world, is discontinuous (that is, personal, or ‘inner’), but is nonetheless communicable. The experience of necessary discontinuity tends, paradoxically, back towards continuity, in its state of simultaneous extremes: despair and rapture.

(…)

The titles Bataille gave to his three works are appropriate to the paradoxical (or ‘impossible’) structure of his thought: Inner Experience (1943), Guilty (1944), and On Nietzsche (1945) – the Summa Atheologica (La Somme athéologique). The relation of these three texts to religion remain ambivalent throughout, and the apparent opposition between their title’s referent (Thomas Aquinas’s Summa Theologica [1485]) and their atheism never resolves itself into a straightforward distinction.

Bataille is both dismissive of and fascinated by religion. He frequently treats Christian dogma as laughable and pernicious, while returning compulsively to depictions of religious ecstasy, mystical tracts, and the ritualized sacrifices common to both modern and ancient religions.

Bataille shares with Nietzsche this decidedly theological approach to atheism, which is at least as concerned with the generation of new rituals and deities as with the dismissal of old ones. Religion is, after all, counted among Bataille’s principle modes of ecstatic expenditure. Bataille describes its proximity to death and eros; its capacity to produce moments of bliss approaching the impossible, and to make believers forget their profane, quotidian lives of material accumulation. Religion, therefore, is an object of contradictions, dual impulses straining in opposite directions.

(…)

For Bataille, the death of Christ is only a partial sacrifice, insofar as God survives and recuperates the demise of Christ’s body. This recuperation, for Bataille, is essentially profane in character, and thwarts the sacred expenditure of the sacrifice proper. The immortality of God, and Christ’s resurrection, exemplifies for Bataille the underlying profanity of Christianity (and religion at large): its reliance on the crutch of postponement and recuperation in heaven – it sullies the ecstatic expenditure of the sacrifice by expecting to get something back.

(…)

In particular, and this is a motif that recurs in almost every work Bataille ever wrote, Bataille saw the sacrifice in its various forms as the most exemplary sacred thing: an event mingling death, eros, spectacular waste, and bridging the gulf between the private selves of its spectators. Where profane life cannot tolerate the logic of the sacrifice, preferring to always invest resources and life profitably, to postpone consumption in favour of productive growth, the sacrifice expends life, food, and precious resources unproductively, now.

Bataille identifies consciousness with discontinuity. By inhabiting one’s own conscious mind, one is cut off from other minds: the precise conditions of life are those of discontinuity with others. Conscious human life is defined by the boundaries that separate self from other. Before and after life, however, continuity reigns. Both before birth and at the moment of death, these boundaries dissolve.

Bataille identifies a universal nostalgia for continuity, a hunger sated in moments of expenditure, mystical bliss, and erotic throes. The hunger for continuity approaches the desire for death, but is staved off from this target by the fear of losing one’s discontinuous self forever, requiring proxies for the experience of continuity, which nonetheless always tends towards the grave.

Chief among these, the sacrifice allows a moment of nearness to the continuity of death, without having to undergo its irremediable operation. For the sacrificed person or object, meanwhile, the sacrifice is an elevation to the domain of sacred things.

Bataille writes at length in The Accursed Share about the structure and purpose of Aztec sacrifices, dedicating an entire chapter to this phenomenon. He identifies the purpose of the Aztec sacrifice as being one of restoration: the sacrifice renders sacred again something or someone that has been made profane – has slipped into the logic of utility, production, and function. Thus, the sacrifice of slaves was deemed a restoration of the human to the world of sacred things, where the living being had been transformed into a tool of production.”

#mishima#yukio mishima#esoterica#justin sledge#mysticism#philosophy#sun & steel#seppuku#suicide#annihilation#flesh#bataille#georges bataille#sacrifice#sacred#profane#acephale#acéphale

14 notes

·

View notes

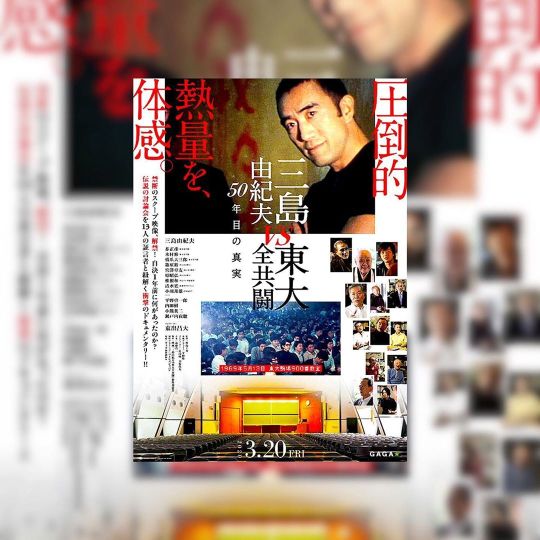

Photo

・ ・ #東京アラート発動中 #socialdistancing #tohoシネマズ日比谷 #復活 ・ 【今日の本命】 三島由紀夫vs東大全共闘〜50年目の真実〜漸く観れた。 非常に観て良かった! ・ お互いに元々は反米愛国主義で、ある意味“尊王攘夷”。幕末の薩摩と長州ではないですか! 楯の会と全共闘が共闘していたら、三島は龍馬にでもなり得たのか? 歴史にタラレバはない。だから、三島は共闘しなかった。右でも左でも勝てない事を知っていたのかなあ、三島は。 三島の自決から今年50年になる。早めに配信して冷めた日本人の熱量をアゲた方が良いと思いますが。 ・ #三島由紀夫vs東大全共闘50年目の真実 #mishimathelastdebate #豊島圭介 #東出昌大 ・ #三島由紀夫 #yukiomishima #楯の会 #tatenokai #芥正彦 #masahikoakuta #東大全共闘 #zenkyoto #小川邦雄 #tbs #瀬戸内寂聴 #jakuchosetouchi ・ #圧倒的熱量を体感 ・ #映画 #movie #cinema #ビバムビ #ınstagood #instamovie #instapic #moviestagram (TOHO Cinemas 日比谷) https://www.instagram.com/p/CBDQ_DQABAV/?igshid=wzv1j7rep7d

#東京アラート発動中#socialdistancing#tohoシネマズ日比谷#復活#三島由紀夫vs東大全共闘50年目の真実#mishimathelastdebate#豊島圭介#東出昌大#三島由紀夫#yukiomishima#楯の会#tatenokai#芥正彦#masahikoakuta#東大全共闘#zenkyoto#小川邦雄#tbs#瀬戸内寂聴#jakuchosetouchi#圧倒的熱量を体感#映画#movie#cinema#ビバムビ#ınstagood#instamovie#instapic#moviestagram

0 notes

Link

Kimitake Hiraoka (平岡 公威 Hiraoka Kimitake, January 14, 1925 – November 25, 1970), known also under the pen name Yukio Mishima (三島 由紀夫 Mishima Yukio), was a Japanese author, poet, playwright, actor, model, film director, nationalist, and founder of the Tatenokai. Mishima is considered one of the most important Japanese authors of the 20th century. He was considered for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1968, but the award went to his countryman Yasunari Kawabata. His works include the novels Confessions of a Mask and The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, and the autobiographical essay Sun and Steel. Mishima's work is characterized by its luxurious vocabulary and decadent metaphors, its fusion of traditional Japanese and modern Western literary styles, and its obsessive assertions of the unity of beauty, eroticism and death.

Ideologically a right wing nationalist, Mishima formed the Tatenokai, an unarmed civilian militia, for the avowed purpose of restoring power to the Japanese Emperor. On November 25, 1970, Mishima and four members of his militia entered a military base in central Tokyo, took the commandant hostage, and attempted to inspire the Japan Self-Defense Forces to overturn Japan's 1947 Constitution. When this was unsuccessful, Mishima committed seppuku.

#yukio mishima#hiraoka kimitake#三島 由紀夫#wikipedia#japan#writer#actor#model#film director#seppuku#tatenokai

1 note

·

View note