#specifically the wives and CHILDREN of the sailors or soldiers

Text

me: okay im pretty tired so im just gonna find something light to watch

video about the rms laconia: exists

me: oh hey, i know that one pretty well, i wont end up angry crying about it this time. clicks on video

an hour later

me: is angry crying about it this time

#kai rambles#...listen#ive said like ten thousand times that im a ship person but not a warship person#but i know about a fairly decent amount of them#mostly because a lot of liners got requisitioned on ww1 or ww2#or were secretly helping the war effort like lusitania#so like i know about lusitania or the captain or hood or sydney etc.#olympics dazzle paint for the war effort is actually a really cool topic#but like#obviously a lot of warship stories are very tragic like the uss indianapolis#and the laconia#but the laconia is just like being punched over and over and over again#because even before the disaster youve got italians pows on board who were being treated awfully and someone having to stand up and stop it#them youve alsl got her being unaccompanied on her route despite being a target and needing it because the navy just didnt have the boats#which led to some officers and civilian passengers feeling overconfident because ''we dont need an escort'' and oh yeah there were civilian#specifically the wives and CHILDREN of the sailors or soldiers#and to make it worse shes over 20 years old and needs new boilers and anywhere she goes a giant black cloud of smoke follows from her funne#so shes an easy target which led to her a u-boat torpedoing her and her sinking which also had this thing where they tried to trap the pows#in the ship so everyone else could get off which fuck that and also it was listing so not all the lifeboats could be launched and most were#overcrowded and also there were sharks atfacking them#and then the u-boat is coming nearer but when the captain realises who were on board HE STARTS A RESCUE EFFORT#and he lies to base and manages to organise a rescue with other u-boats (preventing an attack actually) but then hitler gets wind of it and#he cancels that and tells them to leave the survivors to their fates SO THIS GUY DISOBEYS HITLER AND MAKES A DESPERATE CALL IN ENGLISH TO#THE ALLIES ASKING FOR RESCUE PROMISING NOT TO ATTACK IF THEY DONT ATTACK AND GIVING HIS POSITION TO THEM#and they don't even believe it for two days straight but eventually a few more u-boats arrive to help with promises from italy france &#britain to help and like theyve got a 1000 people mostly in lifeboats tied to the u-boats flying the red cross. and in the night the u-boat#on scene get separated and an american bomber arrives on scene and the survivors think rescues coming but then the bomber gets orders#TO SINK THE U-BOAT SO THEY FIRE OFF THREE ATTACKS WITH ONE JUST LANDING WITHIN THE LIFEBOATS KILLING PEOPLE#and the u-boat guy ends up having to leave the scene because hes fearful for his crew now understandably and the survivors just have to wai#for rescue which does come. but wanna know what happened to the bomber and the guy who gave the order? NOTHING. NOT EVEN AN INVESTIGATION

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Unexpectedly and quite by accident, I’ve fallen down a rabbit hole researching the historical Charles Frederick Des Voeux.

I’ve learned a lot about the Franklin Expedition and its members lately through the brilliant efforts of the Terror fandom... But it occurred to me that I’ve seen barely any mention whatsoever of the real Des Voeux! Possibly this is simply because I’ve missed it, in which case, my bad; possibly this is because no one’s interested, in which case I’ve wasted a lot of time. But I got curious. So I started digging, and I found...

...not a ton, I’m afraid. Not in great detail. As Sir Francis McClintock noted, Des Voeux was young. His career was still just starting, and he simply hadn’t had much time yet to leave his mark. Yet he’d already been noted for his “intelligence, gallantry, and zeal.” He’d already traveled widely, served in multiple wars, and was recommended to the Erebus by none other than Fitzjames, who described him as “a most unexceptionable, clever, agreeable, light-hearted, obliging young fellow, and a great favourite of Hodgson’s, which is much in his favour besides.”

So here’s everything I’ve got on the real Charles Frederick, as best I could stitch together from naval records, histories, and more. Also featuring some thoughts on his portrayal in the TV series; Goodsir “in ecstacies”; a bit about Hodgson; and quite a lot of Fitzjames.

A quick note on accuracy. I’m not a historian. I tried my best. Most of the info here about Des Voeux’s naval career comes from sources that seem credible and that often back each other up. The bit I’m more cautious about, though, is his ancestry and early life, because the only source I could find claiming any knowledge of that was Burke’s Peerage, and Burke’s has been known to be... wrong. For lack of any info to the contrary, I’m going to give y’all Burke’s version of events for now, but for more on my findings and reservations, see the Sources section at the end of this post. And if you have more info on ol’ C. Freddie or spot any mistakes, feel free to let me know!

Edit, 11/9/18: Good news! @francienolan was kind enough to send me a newspaper clipping from The Colonies and India, May 25, 1895, featuring a statement from colonial governor George William Des Voeux supporting Burke’s claims. I’ve updated bits of this post accordingly and have added G. William’s statement to the Sources section at the end, but I’ve also left my original discussion of Burke’s information intact.

Early Life

According to Burke’s Peerage, Charles Frederick was the second son of Reverend Henry Des Voeux, himself the third son of Sir Charles Des Voeux, 1st Baronet of Indiaville, in the Queen’s County, Ireland (now County Laois). Ireland? But Des Voeux is a French name, right? Yes! It was also not the family’s original name, but yes, their origins were French. Marin Anthony Vinchon de Bacquencourt picked “Des Voeux” as his new surname after having a falling-out with Catholicism, which resulted in a falling-out with his family, which resulted in his emigrating from Normandy to Ireland. De Bacquencourt’s son, the aforementioned grandpa Sir Charles, was born in Ireland, got rich in India, repped Carlow Borough and Carlingford in the Irish House of Commons, and was created baronet in 1787. Fittingly for a house whose founder chose the name voeux (which can be translated as “wishes”), the official family motto was Altiora in votis: “Greater things are the objects of my wishes.”

Burke’s doesn’t bother listing Charles Frederick’s year or place of birth, because that would make my life too easy. But we can make some guesses. We know that his big bro (Henry Dalrymple) was born in either 1822 or 1824 and that his immediately younger bro (Charles Champagne) was born in 1827. (1827 also marks the death of Rev. Henry’s first wife, Frances Dalrymple of Barrow, County Derby, married December 1, 1812. Assuming C. F. was legitimate, which I’ve found no reason not to assume, Frances would have been his mother.) Thus, assuming at least a year between children, we can estimate that Charles Frederick was born no earlier than 1823 and no later than 1826.

As for where... The baronetcy was in Ireland, yes, but Henry Dalrymple was born in England — specifically, in Carlton, Nottinghamshire, which is also where Rev. Henry married his second wife, Frances (Fanny) Elizabeth Hutton, in 1828. If Rev. Henry’s family was in Carlton in both 1822/24 and 1828, it seems possible they were there when Charles Frederick was born, too. The genealogies I’ve found have had wildly different opinions about Rev. Henry’s total number of children, but according to Burke’s, at least, between his father’s three wives, Charles Frederick had eight full or half siblings: five brothers and three sisters. Some sources list fewer; some list even more! Who knows!

Alas: that’s all I’ve got on his early life, and it frustrates me that so much of it is based in reading between the lines. I do want to note the baronetcy’s coat of arms, which I found intriguingly squirrel-centric. Pictured up top, they consisted of a red field with a gold vertical stripe containing a squirrel above a Maure, with another purple squirrel as the crest. I mention this for one reason and one reason only: I now cannot stop thinking of Sebastian Armesto’s snarky, moody Mr. Des Voeux as a grumpy squirrel.

The Second Syrian War (1840)

Fast forward to 1840, when, happily, our information becomes much more specific. This year marks the first record I’ve found of Des Voeux’s naval career, when, according to McClintock, he served in the Second Syrian War (the Second Egyptian–Ottoman War) under Commodore Sir Charles John Napier, captain of the Powerful.

Des Voeux would now have been between the ages of 14 and 17. He definitely was not yet a mate, but I couldn’t find his exact rank at the time or any other particulars of his service in this conflict.

I know this post is supposed to be about Des Voeux, but I’d be remiss not to mention that another familiar face was also in the area: our good buddy James Fitzjames! He’d been a gunnery lieutenant aboard the Ganges (under Captain Barrington Reynolds) since October 17, 1838, and when the war began, his ship headed for the Mediterranean alongside the Powerful and the Implacable. James made himself rather notorious here by undertaking the tricky (and highly perilous) task of sneaking into Beirut one night, distributing a proclamation by Napier to the Egyptian soldiers camped there, and sneaking out again, which pissed off Egyptian commander Soliman Pasha al-Faransawi so much he put a price on Fitzjames’s head. Normal Tuesday night for James Fitzjames, really.

Whether Des Voeux and Fitzjames ever crossed paths in the Mediterranean, I don’t know. But they definitely did during...

The First Opium War (1841–42)

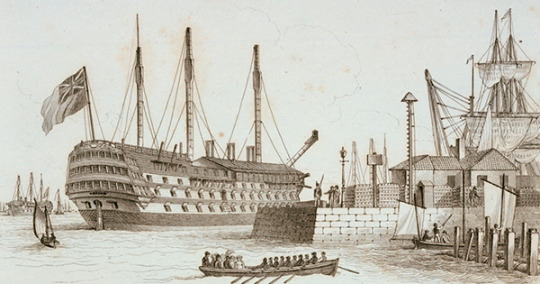

All aboard the Cornwallis! Pictured above, this 74-gun third-rate ship of the line hosted treaty negotiations following China’s defeat in 1842, and during the war itself, it served as home to Des Voeux as well as at least three other future members of the lost Franklin Expedition.

You can probably guess that Fitzjames was one of them; this war was, after all, “the time he got shot by the Chinese.” He’d caught the attention of Sir William Parker during the Syrian War and, after getting home and serving just a few weeks aboard the Excellent at Portsmouth, was appointed to the Cornwallis, Parker’s flagship, in April or May of 1841.

Fitzjames recalls that Des Voeux was “a mere boy” at this time (he would’ve now been between 15 and 18) and that he was en route to join the Endymion, commanded by Sir Frederick Grey. Des Voeux did indeed transfer to the Endymion at some point during the war, though I’m not sure where or when. The Cornwallis departed from Plymouth July 3, 1841, and reached Chusan on January 12, 1842; the Endymion departed Plymouth February 2, 1841, but had to refit its mainmast at the Cape of Good Hope and its hull at Aden, and THEN spent some time in the East Indies, so it didn’t reach Chusan till July 5, 1842. I’m not sure whether Des Voeux stayed on the Cornwallis all the way to China or whether he joined the Endymion at some port en route. Somewhere in the midst of all this, he also found time to serve as a naval aide-de-camp to General Sir Hugh Gough, the British commander-in-chief.

Another future Erebite to serve on the Cornwallis in China was Stephan Stanley, though Fitzjames tells us his time on board was brief, and I don’t know that it overlapped with Des Voeux’s. And, last but not least: George Henry Hodgson. At this time a mate, he was appointed to the Cornwallis on June 5, 1841, and distinguished himself in his service, particularly at Chinkiang (Zhenjiang) — so much so that he was rewarded with a lieutenant’s commission on December 23, 1842, shortly after the end of the war. He would probably love to tell his fellow officers about his role at Chinkiang over dinner sometime, I reckon, if even the slightest mention of that battle didn’t make Fitzjames launch into his whole bullet-wound saga again.

Perhaps the Cornwallis is where Hodgson’s particular fondness for Charles got its start. At any rate, the acquaintance with Fitzjames would prove fateful (and indirectly fatal) for Des Voeux.

Officer’s Examinations and Training (1844)

The next mention I’ve found of Charles Freddie comes from May 1, 1844, when he passed the examinations required for lieutenant rank and was promoted to mate / sub-lieutenant. Congrats!

Shortly after, in June, he was appointed to the Excellent (formerly the Boyne, above) at Portsmouth. I previously mentioned Fitzjames being employed on the Excellent also, as was Hodgson at various times. It was, in fact, a training ship — a gunnery school anchored north of Portsmouth Dockyard where sailors trained in such skills as artillery and mathematics by, say, firing big guns into the creek. Fitzjames served here in 1838 from January 19 to October 17, and then again for a few weeks in the spring of 1841. Hodgson served for some time starting in October 1840 and then again starting November 27, 1844; and Des Voeux served for “several months” starting in June 1844. Captain Sir Thomas Hastings was commander throughout all these years.

And now, at last, we reach 1845.

The Franklin Expedition (1845–??)

Des Voeux joined the crew of the Erebus on March 4, 1845, on the recommendation of James Fitzjames, who selected him based on their service together aboard the Cornwallis. He was now no older than 22 and no younger than 19.

We all know how this ends, even if we don’t know exactly when or how Des Voeux died. The National Maritime Museum’s collection contains a scrap of a wool shirt trimmed with cotton, cream colored, that was found by Inuit of Repulse Bay at a campsite near the mouth of the Back River and obtained from them by John Rae. A group of men from the expedition had starved to death at this camp. Near the left edge of the fragment, in line with the buttonholes, is inked “F:D:V: 1845.”

I suppose that’s not necessarily proof Des Voeux died at that camp; another man could have appropriated the shirt before or after Des Voeux’s death. But we know Des Voeux was at least still alive by May 28, 1847, when he and Graham Gore signed the record left in the cairn at Victory Point:

“28th of May, 1847. H.M. ships ‘Erebus’ and ‘Terror’ wintered in the ice in lat. 70° 05′ N., long. 98° 23′ W.

Having wintered in 1846–47 [sic; it was actually the winter of ’45–46] at Beechey Island, in lat. 74° 43′ 28′′ N., long. 91° 39′ 15′′ W., after having ascended Wellington Channel to lat. 77°, and returned by the west side of Cornwallis Island. Sir John Franklin commanding the expedition. All well. Party consisting of 2 officers and 6 men left the ships on Monday, 24th May, 1847.

Gm. Gore, Lieut.

Chas. F. Des Voeux, Mate.”

Funnily enough, Des Voeux was technically not, by this time, a mate. One of the things that started me down this research rabbit-hole in the first place is that I came across a source referring to him as a lieutenant. That took me rather aback! The TV show never refers to him that way. As it turns out, though, Her Majesty did indeed promote Des Voeux, by brevet, to lieutenant on November 9, 1846. This was announced in a November 10 supplement to the London Gazette, which printed his new rank amid a long list of other officers whose various commissions were all to be dated to the 9th. Of course, by this time, the expedition had been gone more than a year already, the ships were already icebound off the coast of King William Land. Neither Des Voeux nor any of his shipmates could ever have learned of this. (The other mates — Sargent, Couch, Hornby, and Thomas — all received their commissions during the expedition, too.) As such, a lot of sources do refer to Des Voeux by his official rank of lieutenant, but for the purposes of the expedition itself, as far as we know, he continued to function as a mate.

Side note: It just so happens that I’m posting this on November 9, 2018. So... Happy 172nd anniversary of that promotion you never knew about, dude.

Tragedy is unavoidable with the Franklin Expedition, but I want to end this little history on a happier note. The following anecdote comes from a journal Fitzjames kept from June 8, 1845, a couple weeks after the expedition left Greenhithe, to July 11, the day before they continued onward from their stop at the Whalefish Islands in Greenland’s Disko Bay. Here they left the last of their letters ever to reach home. On Wednesday, June 25, 1845, Fitzjames recorded this pleasant scene of Des Voeux helping Goodsir collect specimens:

“I am now writing, 11 P.M., lat. 63°, near about a place marked on the chart as Lichtenfels. The sea, as the sun set half an hour ago, was of the most delicate blue in the shadows; perfectly calm — so calm that the Terror’s mast-heads are reflected close alongside, though she is half a mile off. The air is delightfully cool and bracing, and everybody is in good humour, either with himself or his neighbours. I have been on deck all day, taking observations. Goodsir is catching the most extraordinary animals in a net, and is in ecstacies. Gore and Des Voeux are over the side, poking with nets and long poles, with cigars in their mouths, and Osmar laughing.”

I think this a sweet way to remember them all: happy in each other’s company, laughing, on a beautiful summer’s eve. And wow, you can really tell it’s summer in the Arctic when the sun’s just set at 11 p.m., huh?

Thoughts on Des Voeux in The Terror (2018)

It’s been a bit surreal getting an idea of the real Des Voeux after only knowing him from The Terror. I haven’t read the novel, so I can’t speak to Dan Simmons’s depiction; as for the TV series, on my first watch-through I barely noticed him at all. By my second watch, I’d since taken notice of Sebastian Armesto in general, and I made a special point of recording every sign of Des Voeux in every episode: what he says, what he does, his personality, etc.

The show’s version of Charles Frederick is not terribly likable. He’s condescending to Goodsir and hostile to the Inuit. He’s sardonic at the best of times and, at worst, a mutineer, a cannibal, the killer of Tom Hartnell, a pathetic figure last seen begging Silna, whom he always disparaged, for help. He does not, in short, much resemble the friendly, good-humored boy who caught sea creatures for Goodsir and was so well-liked by Hodgson and Fitzjames.

But even on the show, he’s also portrayed as a highly capable officer — highly trusted, even, right up till the mutiny. Heck, part of the reason the mutiny succeeds is because he’s so trusted: in 1.08, when Crozier says they need a mate to guard the armory, Fitzjames immediately suggests Des Voeux, unaware that he’s already under Hickey’s sway. In 1.04, too, Fitzjames entrusts him with guarding Silna on her first night aboard the ship. It’s an echo (perhaps an unintentional one) of the real Fitzjames’s regard for the real Des Voeux — a regard which inadvertently doomed the younger man by securing his spot on the expedition in the first place, and which, in the show’s version of events, is all the more bittersweet in light of his eventual betrayal.

There’s an echo, too, of Des Voeux’s training aboard the Excellent that shows in his facility with artillery, maths, and calculations. In 1.02, he leads the party to the cairn so accurately that Gore says he deserves a prize for his orienteering, and in 1.05, we see him performing calculations to determine atmospheric pressure based on the speed of sound. He’s put in charge of armed parties multiple times throughout the series, suggesting he’s capable with a rifle, if tragically twitchy-fingered at times. There’s even an echo of his service in China in the East Asian–esque shirt he wears as a costume at Carnivale.

I don’t know whether the writers had the real Des Voeux’s background in mind when coming up with ANY of this; for all I know, I’m reading too deep into coincidence. But it’s interesting all the same. And though I really don’t mind that the show decided to make Des Voeux rather unpleasant — that version is an interesting character in his own right — I can’t help but feel a new and surprisingly deep attachment to him now that I’ve spent so much time trying to get to know the real guy, who left so few traces other than his name on some papers and a fragment of shirt.

Sources

Edit, 11/9/18: In the original version of this post, I expressed a lot of concerns about whether Charles Frederick was truly of the Indiaville family of Des Voeuxes, as I couldn’t find any source other than Burke’s to verify it. Happily, it turns out that Sir George William Des Voeux, a governor of Fiji, Newfoundland, and Hong Kong, wrote the following to The Colonies and India on May 25, 1895:

“Being, to my great regret, unable to attend the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the departure of the Franklin Expedition, I venture to ask of your courtesy the permission to make known through your columns the fact that injustice has been done to the memory of one of the officers of that expedition by the misspelling of his name upon the memorial column in Waterloo Place. The officer in question was my brother, Charles Frederick Des Voeux, mate (subsequently promoted to lieutenant) in the Erebus, Sir John Franklin’s ship.”

G. William was definitely the son of Rev. Henry Des Voeux and a descendant of de Bacquencourt, and thus, despite all my reservations, it appears that Burke’s genealogy is indeed... correct! I’ve left my original discussion of Burke’s Peerage intact below, though, for anyone interested.

Original version of this section:

Most of the info in this post comes from one or more of the following:

The Voyage of the ‘Fox’ in Arctic Seas (Sir Francis Leopold McClintock, 1859)

A Naval Biographical Dictionary (William Richard O’Byrne, 1849)

Papers and Despatches Relating to the Arctic Searching Expeditions of 1850 (James Mangles, 1852)

The National Maritime Museum

The Royal Navy Lists

These sources corroborate each other sufficiently that I feel pretty OK about the info gleaned from them, which primarily pertains to Des Voeux’s naval career. As mentioned up top, though, the only source I could find on Des Voeux’s ancestry and early life was Burke’s Peerage. At least four editions (of the editions I could find scans of) explicitly identify Rev. Henry Des Voeux’s second son as our Des Voeux. “Charles-Frederick, R.N., lieut. on board one of the ships of Sir John Franklin’s ill fated expedition” appears in the 1898, 1910, and 1914 editions; the 1907 edition reads “Charles Frederick, R.N. lost in Sir John Franklin's expedition.”

Burke’s isn’t necessarily wrong, but it’s definitely been known to make mistakes, and I really wanted to find another source verifying that our Charles Frederick was, indeed, of the Indiaville family, in case he could possibly have come from some other family also called Des Voeux. Basically, my concern has been: What if Burke’s just plain wrong? What if the idea that this lost member of an infamous expedition belonged to the Des Voeuxes of Indiaville was an invention erroneously conjured up later, simply because they happened to share a name?

Unfortunately, the genealogies and peerage lists I found were contradictory and/or glaringly incomplete. Even the ship’s musters from the Cornwallis, Endymion, etc., could have been immensely helpful here, as they sometimes list ages and even place of birth (though the Erebus’s manifest doesn’t list either for Des Voeux), but the National Archives hasn’t yet digitized the records from the relevant ships and years.

Another frustration is an inconsistency — or, rather, a lack of detail — in Burke’s itself. While some editions explicitly link him to the expedition, many earlier ones (such as 1845, ’48, ’50, ’58, ’60, ’61, ’65, and ’68) refer to Rev. Henry’s second son simply as... “Frederick, R.N.” No “Charles”; no further detail. I’d feel much more secure if a full “Charles-Frederick” had appeared in editions printed before the Franklin Expedition became so infamous. Even these earlier editions, though, all at least note that “Frederick Des Voeux” was Royal Navy — R.N. — and they shorten his siblings’ names as well. Henry Dalrymple is listed simply as “Henry”; Charles Champagne is just “Charles.” So “Frederick” could, conceivably, likewise be standing in for two given names, e.g. Charles Frederick. And something must have happened to Frederick by 1894 to render him dead, missing, or otherwise ineligible for a title, as the baronetcy skips straight from Henry Dalrymple (5th Baronet) to Charles Champagne (6th).

In the end... Who knows. I can’t prove he was of the Des Voeuxes of Indiaville; I can’t prove he wasn’t. For what it’s worth, though, I can tell you that like 50% of the guys in the Indiaville family were apparently named Charles and/or Frederick. If nothing else, our boy would fit right in.

#charles frederick des voeux#franklin expedition#the terror#sebastian armesto#james fitzjames#george hodgson#des voeux#the longest post nobody asked for#my meta#history#meta#op#stephan stanley#dr stanley#charles des voeux

364 notes

·

View notes