#rotterdam 2021

Text

How people perceive me and my buddies

What we are actually like:

#blind channel#citi zeni#eurovision 2021#eurovision 2022#rotterdam 2021#turin 2022#joel hokka#niko vilhelm#joonas porko#alex mattson#tommi lalli#olli matela#eat your salad#dark side#instead of meat i eat veggies and pussy#put your middle fingers up

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#måneskin#måneskin hq#eurovision#thomas raggi#damiano david#damiano David hq#rotterdam#the netherlands#netherlands#victoria de angelis#ethan torchio#winner#2021#eurovision song contest

601 notes

·

View notes

Text

You Never Forget Your First

#UEFA Europa Conference League#season 2021/2022#Finals#AS Roma#Feyenoord Rotterdam#Tirana#National Arena#football#fussball#fußball#foot#fodbold#futbol#futebol#soccer#calcio

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Eles transportan a morte - Helena Girón, Samuel M. Delgado (2021)

Poster / http://beginagainfilms.es

#eles transportan a morte#helena girón#samuel m. delgado#2021#2020s#spain#begin again films#poster#drama#rotterdam film festival

0 notes

Text

one (1) person said they wanted to hear more about the alex de minaur jannik sinner narrative so here we go

it is 2019. your name is alex de minaur. you are 20. you are seeded first in the atp next-gen finals, you have three actual atp titles, you're ranked 18th in the world, and you're an aquarius man; consequently, you are somewhat full of yourself. you wear tennis gear with your ridiculous nickname on it. you speak spanish every two seconds in the documentary, because you must show off. you believe you are, by all rights, The Main Character.

then this skinny italian wild card pops up and destroys you.

okay. that's fine. embarrassing!!! but fine. whatever. we move on. he's cool! you're friends! let's keep going. at the end of 2020, you run into him again in the sofia quarterfinals, where you take the first set and then he destroys you again. with a breadstick to really rub it in. he goes on and wins the whole thing, which means he wrecked you on his way to his first-ever atp title. fine! okay. whatever.

it is 2021. you don't see him again, which is just as well, because you have a soaring high and then a terrible low (string of r1/r2 losses). you drop to 34th in the world; meanwhile, jannik sinner has spent the year going from 37th to cracking the top 10. things are not looking great.

in 2022, you make it to the third round of the auso for the first time, where you meet—guess who—jannik sinner. again. you're starting to get really tired of this guy. he knocks you out of your home slam. thankfully you have a relatively successful year afterwards, climbing back up the ranks.

it's 2023! this will be your year, surely. you kick it off by winning your first 500. the sunshine double doesn't go great but you do brilliantly at queen's club and los cabos, only losing in the finals to top 10 players. then.... Canada.

you beat fritz. you beat medvedev. you make it to the final of a 1000 for the first time! and then jannik sinner is there in all his ginger glory, and, well. you know how this is going to go. bye-bye first 1000 title, hello increasingly miserable h2h. you start wondering if you're going to be there for all of this guy's career-defining wins. you start wondering why the hell it had to be you specifically. this is getting ridiculous. because now it's 2024 and he won the whole entire australian open and then to really seal in the whole thing he had to go and beat you, specifically in rotterdam to make some more history.

and like, you guys are friends. pretty good friends, actually. you played doubles once and it was hilarious!! but also, consistent and absolute annihilation??? seriously???

in summary i find their friendship absolutely mindbending. alex de minaur you must be the nicest person ever because personally if someone did me like this i would spend my entire life trying to blow them up with my mind

#alex de minaur#jannik sinner#they are hilarious to me#like what do you mean you're this guy's good friend how are you not aflame with resentment please teach me your anti-hater ways#de sinnaur

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

In his own words: Christian Horner on world champion Max Verstappen

Verstappen won another world title on Saturday.

written by: Christian Horner, originally published on The Independent, 08, October 2023 [x]

I remember raising it to Helmut Marko – Red Bull’s motorsport consultant – that this kid looks the real deal. Helmut watched him at the Norisring in Germany and he was convinced.

There was interest from Niki Lauda and Mercedes, but Red Bull could take him to Formula One immediately. So, he came to us a very young age. He was 16. And I remember in his very first outing for us – a demonstration run in Rotterdam – he took the front wing off the car! But you could tell in the seat fitting the confidence he had for a young guy was exceptional.

All of the drivers that came through the junior categories learned their trade out of the spotlight, but Max became the youngest driver in Formula One ever. He was only 17. Every move and every mistake he made was scrutinised.

Jean Todt, who was the FIA president at the time, changed the regulations to ensure someone as young and inexperienced as Max could not enter F1. There will never be a driver that moves so rapidly from karting to F1 again. But the way he dealt with it mentally made him a standout character.

It was obvious in his first full F1 season when he drove for Red Bull’s sister team Toro Rosso, that he was an emerging talent, and at the beginning of 2016 he was performing beyond the capability of the car.

Daniil Kvyat was struggling, and there was a lot of interest in Max. We made the decision to move him to Red Bull at the Spanish Grand Prix.

Mercedes did their thing when Lewis Hamilton and Nico Rosberg crashed into each other on the first lap and Max, who started fourth which was already stunning, made the one-stop strategy work to win in his first Grand Prix with the team. He became the sport’s youngest ever winner, aged 18. It was a fairytale. Max had arrived.

He won races in 2017 and 2018, and in 2019 he became the team leader following Daniel Ricciardo’s departure to Renault. He grew up, and it was a transformative year for him.

In 2021 we had a car and an engine that could take the fight to Mercedes, and that season will go down as one of the most competitive sporting duels the sport has ever had.

From the first race in Bahrain through to Abu Dhabi, Max and Lewis were like two heavyweights going up against each other. Max was a dog with a bone. He wouldn’t let it go. And you couldn’t script that they would head to the final race tied on points.

Max was very cool. He put the car on pole, and we took our opportunity under the final safety car. Max had one lap to get the job done. I don’t think Lewis expected Max to attack in the corner that he did, and people overlook that he still had to beat Lewis. He still had to win the race. It wasn’t about two unlapped backmarkers. It was about Max reacting to the circumstances and getting the job done. And under the most intense pressure he did just that. He sent it down the inside and the whole place went bananas.

To see him and his father, Jos, celebrate was a very special moment because it was the culmination of all the effort that his father had put into him at a very young age. Max achieved his goal, and anything after that was the icing on the cake, because for him, it was all about becoming a world champion.

Max has still got all the tenacity he had when he got in the car as a 17-year-old, but he now marries that with experience. Outside of the car, he is a normal guy, too. He has his feet on the ground and he hasn’t had his head turned by fame and fortune. He still loves racing, and he has got good, grounded principals.

He is competitive and wears his heart on his sleeve. He is very honest. He will give you everything, but he expects everything in return.

He can go on to achieve so much more. We are riding a wave at the moment, and we want to continue riding that wave for as long as we can.

Will Max be in Formula One for a long, long time? I don’t think so. He has ambitions beyond F1 and beyond racing. And at 26, 36 seems a long way away.

We have a long-term agreement with him until 2028, and he has always said he will be happy to start and end his career here, but motivation will be a crucial factor.

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

jannik sinner career atp titles (so far)

sofia 2020, atp 250 (indoor, hard)

melbourne 1 2021, atp 250 (outdoor, hard)

washington 2021, atp 500 (outdoor, hard)

sofia 2021, atp 250 (indoor, hard)

antwerp 2021, atp 250 (indoor, hard)

umag 2022, atp 250 (outdoor, clay)

montpellier 2023, atp 250 (indoor, hard)

toronto 2023, masters 1000 (outdoor, hard)

beijing 2023, atp 500 (outdoor, hard)

vienna 2023, atp 500 (indoor, hard)

australian open 2024, grand slam (outdoor, hard)

rotterdam 2024, atp 500 (indoor, hard)

miami 2024, masters 1000 (outdoor, hard)

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eurovision Fact #486:

Daði Freyr did not get to perform live at the Eurovisions he participated in due to the 2020 contest being cancelled, and a member of his band getting COVID in 2021.

However, he was invited back to the 2023 contest to perform as a part of the Liverpool Songbook -- the Grand Final's interval act. He decided to sing a rendition of 'Whole Again' by Atomic Kitten for the event.

[Sources]

Liverpool 2023, Eurovision.tv.

Rotterdam 2021, Eurovision.tv.

'Eurovision 2020 in Rotterdam is cancelled,' Eurovision.tv.

Daði Freyr - Whole Again (Atomic Kitten cover) Live @ Eurovision 2023, YouTube.com.

#esc facts oc#eurovision#eurovision facts oc#eurovision song contest#esc#esc 2023#esc 2020#esc 2021#Daði Freyr#atomic kitten

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

organization tags

Links to tags for specific shows from 2022 and years from before that! All dates are formatted in the standard American way.

I did this mainly for my own reference, but any issues, please let me know!

Posts in which I couldn't remember/identify precise years have been tagged with the era (ex. "revenge") but posts that do have years are not also tagged with eras. I might be off for some of them, sorry. Most of these are in relation to Gerard, again sorry.

If there aren't any posts under the tag that means I haven't tagged anything yet and/or I am in the process of changing over tags :)

pre-2001

bullets

2001

2002

2003

revenge

2004

2005

black parade (bp)

2006

2007

2008

2009

danger days (dd)

2010

2011

2012

post-break up

2013

Hesitant Alien (ha)

2014

2015

post-HA ("mr netflix")

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022 shows

eden (5/16), eden 2 (5/17)

mk (5/19), mk 2 (5/21), mk 3 (5/22)

dublin (5/24), dublin 2 (5/25)

warrington (5/27)

cardiff (5/28)

glasgow (5/30)

paris (6/1)

rotterdam (6/2)

bologna (6/4)

munich (6/6)

budapest (6/7)

warsaw (6/9)

prague (6/11)

berlin (6/12)

stockholm (6/14)

bonn (6/17), bonn 2 (6/18)

North America

okc (8/20)

san antonio (8/21)

nashville (8/23)

cincinnati (8/24)

raleigh (8/26)

elmont (8/27)

philadelphia (8/29)

albany (8/30)

uncasville (9/1)

montreal (9/2)

toronto (9/4), toronto 2 (9/5)

boston (9/7), boston 2 (9/8)

brooklyn (9/10), brooklyn 2 (9/11)

detroit (9/13)

st paul (9/15)

chicago [(riot fest) (9/16)]

atlanta (9/18)

newark (9/20), newark 2 (9/21)

dover [(firefly) (9/23)]

sunrise (9/24)

houston (9/27)

dallas (9/28)

denver (9/30)

portland (10/2)

tacoma (10/3)

oakland (10/5)

vegas (10/7)

sacramento (10/8)

la 1 (10/11), la 2 (10/12), la 3 (10/14), la 4 (10/15), la 5 (10/17)

wwwy 2 (10/23), wwwy 3 (10/29)

mexico (11/18)

Oceania/Asia (2023)

Auckland/Tāmaki Makaurau (3/11)

Brisbane (3/13), Brisbane 2 (3/14)

Melbourne (3/16), Melbourne 2 (3/17)

Sydney (3/19), Sydney 2 (3/20)

Tokyo (3/25)

Osaka (3/26)

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

#maneskin#måneskin#maneskin hq#måneskin hq#damiano david#victoria de angelis#ethan torchio#thomas raggi#2021#eurovision 2021#eurovision#eurovision song contest#rotterdam#the netherlands

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

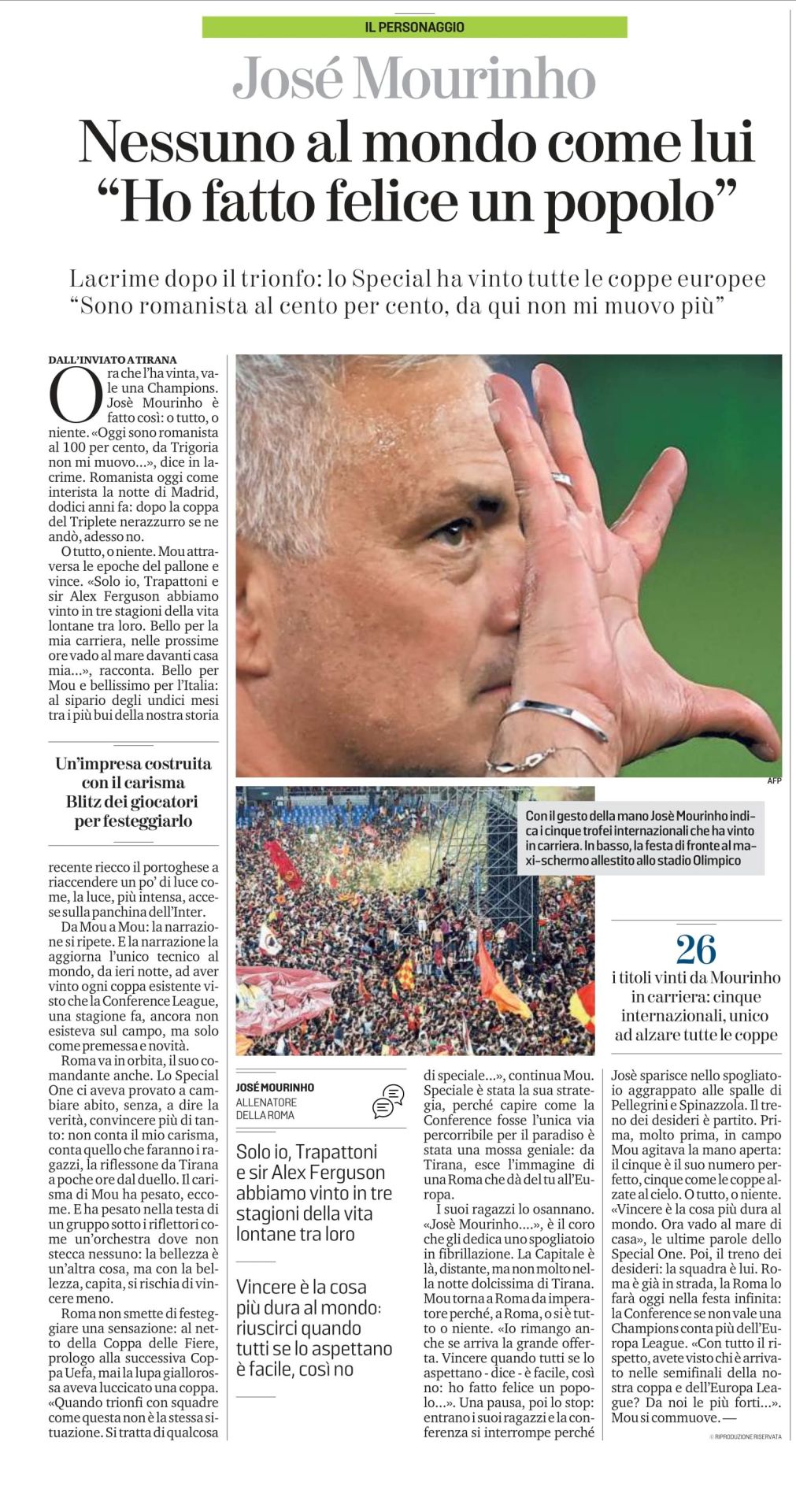

UEFA Europa Conference League Final - AS Roma 1-0 Feyenoord Rotterdam

Arena Kombetare - Tirana

May 25, 2022

AS Roma have won their first UEFA title in their history and their first international competition since the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup in 1960/61 campaign

#UEFA Europa Conference League#season 2021/2022#final#AS Roma vs Feyenoord#AS Roma#Feyenoord Rotterdam#nicolo zaniolo#Champion#football#fussball#fußball#foot#fodbold#futbol#futebol#soccer#calcio

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

This story is part of a joint investigation between Lighthouse Reports and WIRED. To read other stories from the series, click here.

It was October 2021, and Imane, a 44-year-old mother of three, was still in pain from the abdominal surgery she had undergone a few weeks earlier. She certainly did not want to be where she was: sitting in a small cubicle in a building near the center of Rotterdam, while two investigators interrogated her. But she had to prove her innocence or risk losing the money she used to pay rent and buy food.

Imane emigrated to the Netherlands from Morocco with her parents when she was a child. She started receiving benefits as an adult, due to health issues, after divorcing her husband. Since then, she has struggled to get by using welfare payments and sporadic cleaning jobs. Imane says she would do anything to leave the welfare system, but chronic back pain and dizziness make it hard to find and keep work.

In 2019, after her health problems forced her to leave a cleaning job, Imane drew the attention of Rotterdam’s fraud investigators for the first time. She was questioned and lost her benefits for a month. “I could only pay rent,” she says. She recalls the stress of borrowing food from neighbors and asking her 16-year-old son, who was still in school, to take on a job to help pay other bills.

Now, two years later, she was under suspicion again. In the days before that meeting at the Rotterdam social services department, Imane had meticulously prepared documents: her rental contract, copies of her Dutch and Moroccan passports, and months of bank statements. With no printer at home, she had visited the library to print them.

In the cramped office she watched as the investigators thumbed through the stack of paperwork. One of them, a man, spoke loudly, she says, and she felt ashamed as his accusations echoed outside the thin cubicle walls. They told her she had brought the wrong bank statements and pressured her to log in to her account in front of them. After she refused, they suspended her benefits until she sent the correct statements two days later. She was relieved, but also afraid. “The atmosphere at the meetings with the municipality is terrible,” she says. The ordeal, she adds, has taken its toll. “It took me two years to recover from this. I was destroyed mentally.”

Imane, who asked that her real name not be used for fear of repercussions from city officials, isn’t alone. Every year, thousands of people across Rotterdam are investigated by welfare fraud officers, who search for individuals abusing the system. Since 2017, the city has been using a machine learning algorithm, trained on 12,707 previous investigations, to help it determine whether individuals are likely to commit welfare fraud.

The machine learning algorithm generates a risk score for each of Rotterdam’s roughly 30,000 welfare recipients, and city officials consider these results when deciding whom to investigate. Imane’s background and personal history meant the system ranked her as “high risk.” But the process by which she was flagged is part of a project beset by ethical issues and technical challenges. In 2021, the city paused its use of the risk-scoring model after external government-backed auditors found that it wasn’t possible for citizens to tell if they had been flagged by the algorithm and some of the data it used risked producing biased outputs.

In response to an investigation by Lighthouse Reports and WIRED, Rotterdam handed over extensive details about its system. These include its machine learning model, training data, and user operation manuals. The disclosures provide an unprecedented view into the inner workings of a system that has been used to classify and rank tens of thousands of people.

With this data, we were able to reconstruct Rotterdam’s welfare algorithm and see how it scores people. Doing so revealed that certain characteristics—being a parent, a woman, young, not fluent in Dutch, or struggling to find work—increase someone’s risk score. The algorithm classes single mothers like Imane as especially high risk. Experts who reviewed our findings expressed serious concerns that the system may have discriminated against people.

Annemarie de Rotte, director of Rotterdam’s income department, says that people flagged by the algorithm as high risk were always assessed by human consultants, who ultimately decided whether to remove benefits. “We understand that a reexamination can cause anxiety,” de Rotte says, using the city’s preferred term for welfare investigations. She says the city does not intend to treat anyone badly and that it tries to conduct examinations while treating people with respect.

The pattern of local and national governments turning to machine learning algorithms is being repeated around the world. The systems are marketed to public officials on their potential to cut costs and boost efficiency. Yet the development, deployment, and operation of such systems is often shrouded in secrecy. Many systems do not work as intended, and they can encode troubling biases. The people who are judged by them are often left in the dark even as they suffer devastating consequences.

From Australia to the United States, welfare fraud algorithms sold on claims that they make governments more efficient have made people’s lives worse. In the Netherlands, Rotterdam’s algorithmic troubles have run in parallel with a nationwide machine learning scandal. More than 20,000 families were wrongly accused of childcare benefit fraud after a machine learning system was used to try to spot wrongdoing. Forced evictions, broken homes, and financial ruin followed, and the entire Dutch government resigned in response in January 2021.

Imane lives in the Afrikaanderwijk neighborhood of Rotterdam, a predominantly working-class area with a large immigrant population. Each week, she meets with a group of mostly single mothers, many of whom have a Moroccan background, to talk, share food, and offer each other support. Many in the group receive benefits payments from Rotterdam’s welfare system, and several of them have been investigated. One woman, who like many others in this story asked not to be named, claims she was warned her benefits may be cut because her son sold a video game on Marktplaats, the Dutch equivalent of eBay. Another, who is pursuing a career as a social worker, says she has been investigated three times in the past year.

The women are on the front lines of a global shift in the way governments interact with their citizens. In Rotterdam alone, thousands of people are being scored by algorithms they don’t know anything about and do not understand. Amira (not her real name), a businesswoman and mother who helps organize the support group in Rotterdam, says the local government doesn’t do enough to help people escape the welfare system. It’s why she set up the groups: to help vulnerable women. Amira was a victim of the Netherlands’ child benefits scandal and says she feels there is “no justice” for people caught up in the system. “They are really afraid of what the government can do to them,” she says.

From the outside, Rotterdam’s welfare algorithm appears complex. The system, which was originally developed by consulting firm Accenture before the city took over development in 2018, is trained on data collected by Rotterdam’s welfare department. It assigns people risk scores based on 315 factors. Some are objective facts, such as age or gender identity. Others, such as a person’s appearance or how outgoing they are, are subjective and based on the judgment of social workers.

In Hoek van Holland, a town to the west of Rotterdam that is administratively part of the city, Pepita Ceelie is trying to understand how the algorithm ranked her as high risk. Ceelie is 61 years old, heavily tattooed, and has a bright pink buzz cut. She likes to speak English and gets to the point quickly. For the past 10 years, she has lived with chronic illness and exhaustion, and she uses a mobility scooter whenever she leaves the house.

Ceelie has been investigated twice by Rotterdam’s welfare fraud team, first in 2015 and again in 2021. Both times investigators found no wrongdoing. In the most recent case, she was selected for investigation by the city’s risk-scoring algorithm. Ceelie says she had to explain to investigators why her brother sent her €150 ($180) for her sixtieth birthday, and that it took more than five months for them to close the case.

Sitting in her blocky, 1950s house, which is decorated with photographs of her garden, Ceelie taps away at a laptop. She’s entering her details into a reconstruction of Rotterdam’s welfare risk-scoring system created as part of this investigation. The user interface, built on top of the city’s algorithm and data, demonstrates how Ceelie’s risk score was calculated—and suggests which factors could have led to her being investigated for fraud.

All 315 factors of the risk-scoring system are initially set to describe an imaginary person with “average” values in the data set. When Ceelie personalizes the system with her own details, her score begins to change. She starts at a default score of 0.3483—the closer to 1 a person’s score is, the more they are considered a high fraud risk. When she tells the system that she doesn’t have a plan in place to find work, the score rises (0.4174). It drops when she enters that she has lived in her home for 20 years (0.3891). Living outside of central Rotterdam pushes it back above 0.4.

Switching her gender from male to female pushes her score to 0.5123. “This is crazy,” Ceelie says. Even though her adult son does not live with her, his existence, to the algorithm, makes her more likely to commit welfare fraud. “What does he have to do with this?” she says. Ceelie’s divorce raises her risk score again, and she ends with a score of 0.643: high risk, according to Rotterdam’s system.

“They don’t know me, I’m not a number,” Ceelie says. “I’m a human being.” After two welfare fraud investigations, Ceelie has become angry with the system. “They’ve only opposed me, pulled me down to suicidal thoughts,” she says. Throughout her investigations, she has heard other people’s stories, turning to a Facebook support group set up for people having problems with the Netherlands’ welfare system. Ceelie says people have lost benefits for minor infractions, like not reporting grocery payments or money received from their parents.

“There are a lot of things that are not very clear for people when they get welfare,” says Jacqueline Nieuwstraten, a lawyer who has handled dozens of appeals against Rotterdam’s welfare penalties. She says the system has been quick to punish people and that investigators fail to properly consider individual circumstances.

The Netherlands takes a tough stance on welfare fraud, encouraged by populist right-wing politicians. And of all the country’s regions, Rotterdam cracks down on welfare fraud the hardest. Of the approximately 30,000 people who receive benefits from the city each year, around a thousand are investigated after being flagged by the city's algorithm. In total, Rotterdam investigates up to 6,000 people annually to check if their payments are correct. In 2019, Rotterdam issued 2,400 benefits penalties, which can include fines and cutting people’s benefits completely. In 2022 almost a quarter of the appeals that reached the country’s highest court came from Rotterdam.

From the algorithm’s deployment in 2017 until its use was halted in 2021, it flagged up to a third of the people the city investigated each year, while others were selected by humans based on a theme—such as single men living in a certain neighborhood.

Rotterdam has moved to make its overall welfare system easier for people to navigate since 2020. (For example, the number of benefits penalties dropped to 749 in 2021.) De Rotte, the director of the city’s income department, says these changes include adding a “human dimension” to its welfare processes. The city has also relaxed rules around how much money claimants can receive from friends and family, and it now allows adults to live together without any impact on their benefits. As a result, Nieuwstraten says, the number of complaints she has received about welfare investigations has decreased in recent years.

The city’s decision to pause its use of the welfare algorithm in 2021 came after an investigation by the Rotterdam Court of Audit on the development and use of algorithms in the city. The government auditor found there was “insufficient coordination” between the developers of the algorithms and city workers who use them, which could lead to ethical considerations being neglected. The report also criticized the city for not evaluating whether the algorithms were better than the human systems they replaced. Singling out the welfare fraud algorithm, the report found there was a likelihood of biased outcomes based on the types of data used to determine people’s risk scores.

Since then, the city has been working to develop a new version—though minutes from council meetings show there are doubts that it can successfully build a system that is transparent and legal. De Rotte says that since the Court of Audit report, the city has worked to add “more safeguards” to the development of algorithms in general, including introducing an algorithm register to show what algorithms it uses. “A new model must not have any appearance of bias, must be as transparent as possible, and must be easy to explain to the outside world,” de Rotte says. Welfare recipients are currently being selected for investigation at random, de Rotte adds.

While the city works to rebuild its algorithm, those caught up in the welfare system have been battling to discover how it works—and whether they were selected for investigation by a flawed system.

Among them is Oran, a 35-year old who’s lived in Rotterdam all his life. In February 2018 he received a letter saying he was being investigated for welfare fraud. Oran, who asked that his real name not be used for privacy reasons, has a number of health issues that make it difficult to find work. In 2018, he was receiving a monthly loan from a family member. Rotterdam’s local government asked him to document the loan and agree that it be paid back. Although Oran did this, investigators pursued fraud charges against him, and the city said he should have €6,000 withheld from future benefits payments, a sum combining the amount he had been loaned plus additional fines.

From 2018 to 2021, Oran fought against the local authority in court. He says being accused of committing fraud took a huge toll. During the investigation, he says, he couldn't focus on anything else and didn’t think he had a future. “It got really difficult. I thought a lot about suicide,” he says. During the investigation, he was not well enough to find paid or volunteer work, and his relationship with his family became strained.

Two court appeals later, in June 2021, Oran cleared his name, and the city refunded the €6,000 it had deducted from his benefits payments. “It feels like justice,” he says. Despite the lengthy process, he did not find out why he was selected for scrutiny, what his risk scores were, or what data contributed to the creation of his scores. So he requested it all. Five months later, in April 2021, he received his risk scores for 2018 and 2019.

While his files revealed he was not selected for investigation by the algorithm but rather part of a selection of single men, his risk score was among the top 15 percent of benefits recipients. His zip code, history of depression, and assessments by social workers contributed to his high score. “That’s not reality, that’s not me, that’s not my life, it’s just a bunch of numbers,” Oran says.

As the use of algorithmic systems grows, it could become harder for people to understand why decisions have been made and to appeal against them. Tamilla Abdul-Aliyeva, a senior policy advisor at Amnesty International in the Netherlands, says people should be told if they are being investigated based on algorithmic analysis, what data was used to train the algorithm, and what selection criteria were used. “Transparency is key for protecting human rights and also very important in the democratic society,” says Abdul-Aliyeva. De Rotte says Rotterdam plans to give people more information about “why and how they were selected” and that more details of the new model will be announced “before the summer.”

For those already caught in Rotterdam’s welfare dragnet, there is little solace. Many of them, including Oran and Ceelie, say they don’t want the city to use an algorithm to judge vulnerable people. Ceelie says it feels like she has been “stamped” with a number and that she is considering taking Rotterdam’s government to court over its use of the algorithm. Developing and using the algorithm won’t make people feel like they are being treated with care, she says. “Algorithms aren’t human. Call me up, with a human being, not a number, and talk to me. Don’t do this.”

If you or someone you know needs help, call 1-800-273-8255 for free, 24-hour support from the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. You can also text HOME to 741-741 for the Crisis Text Line. Outside the US, visit the International Association for Suicide Prevention for crisis centers around the world.

Additional reporting by Eva Constantaras, Justin-Casimir Braun, and Soizic Penicaud. Reporting was supported by the Pulitzer Center’s AI Accountability Network and the Eyebeam Center for the Future of Journalism.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

#can't believe conchita won 9 years ago#esc 2023#eurovision#eurovision song contest#esc2023#esc#eurovision 2023#i really like 2018 and 2019 and 2021 as well

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

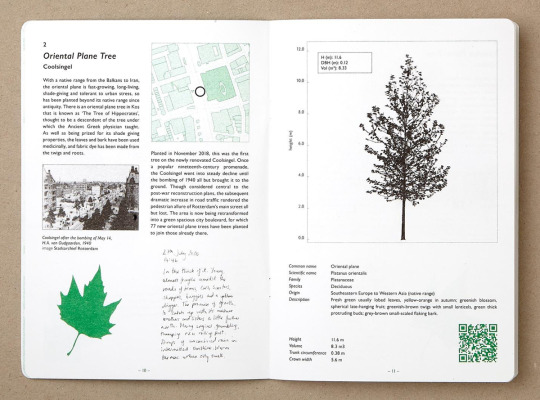

Alice Ladenburg, Fourteen Trees of Rotterdam. A Guide for City Exploration, Design by Peter Foolen and Alice Ladenburg, Peter Foolen Editions, Eindhoven / PrintRoom, Rotterdam, 2021, Riso printed, Edition of 350 [© Alice Ladenburg. Photos: © Willem Mes]

#graphic design#art#geography#urbanism#botany#history#drawing#illustration#book#cover#book cover#alice ladenburg#peter foolen#willem mes#peter foolen editions#printroom#2020s

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Måneskin: ‘People are going to talk s**t about you. It’s part of the game’

From X Factor to Eurovision to interstellar fame, the Italian rockers have turned not being cool into a superpower (posted on 21.01.2023)

Down a video link from Rome, Gen Z’s favourite rock band, Måneskin, are making enthusiastic thumbs-up gestures. “Yeah, yeah, yeah,” says guitarist Thomas Raggi, in his rich and rococo Italian accent. “We’re gonna vote for Ireland,” agrees frontman Damiano David. “Go for it.”

The Irish Times has just canvassed Måneskin’s opinion about Public Image Limited singer John Lydon’s ambition to represent Ireland at Eurovision 2023. The former Johnny Rotten wants to boldly go where no punk iconoclast has previously ventured by following in the footsteps of Dana, Johnny Logan and Dustin the Turkey.

Johnny Rotten singing for Ireland is, in theory, an absurd proposition. But so is the idea of an Italian rock band in sex-dungeon dungarees conquering Eurovision with lyrics such as “you better hold on to your balls”. Which is exactly what Måneskin achieved in Rotterdam in 2021 with the zinging Zitti e Buoni (“Shut Up and Behave”).

Indeed it is arguable Lydon might not have even considered Eurovision were it not for Måneskin. Squeezed into unforgiving leather trousers, tattoos on proud display, they gatecrashed Rotterdam with red eyes and flared nostrils. In doing so, they refashioned Europe’s pre-eminent cheesefest in their own image. Eurovision has been a lot of things in the past 20 years. It took Måneskin to make it cool.

Since then they haven’t looked back. Måneskin have won Best Rock Act at the MTV Europe Music Awards, supported The Rolling Stones in Las Vegas and covered Elvis’s I Can Dream for Baz Luhrmann’s hit Presley biopic.

Now, they are about to open the most exciting chapter of their career to date with the release on January 19th of their fantastic third album, Rush! It captures the group at their most riotous – so much so that it comes as a shock to learn it was produced by Taylor Swift/Britney Spears collaborator Max Martin. At moments they sound like Queen trapped in a Fellini movie. Elsewhere, they’re straight-ahead punk. At one point they appear to be channelling Rage Against The Machine – hardly a surprise since RATM guitarist Tom Morello guests on new single Gossip.

“We’re trying to play with our own rules. And not the rules that in the past five to 10 years have dominated the music industry,” says David (24), earrings glinting in the harsh studio light.

Måneskin don’t claim to be reinventing the wheel. Still, they are well aware of how much they stand out in a musical landscape dominated by pop.

“We go on TV shows and play rock music. Which is uncommon. We do analogue music, which is uncommon. We are a four-piece band,” says David, radiating lounge-lizard charisma. “There are a lot of things in how we create or project and how we show ourselves… I wouldn’t say it’s unique. It isn’t anything that hasn’t been done before. But it’s unique in today’s environment.”

Måneskin have come along at the perfect moment. Mainstream rock, comatose for a least a decade, is crying out for a recharge. Now the status quo has been upended by a group who make headbanging riffs and cock-a-hoop bass solos seem as fresh and daring as Harry Styles in a dress.

“A lot of people love us because we are showing them something that feels new,” says David. “For a lot of kids, rock music is new.”

It isn’t just the kids. Iggy Pop cameos on Måneskin’s 2021 single, I Wanna Be Your Slave. At Coachella last year, Jared Leto sought them out for a selfie. Chris Martin insisted David have lunch with him on that same trip. People don’t simply like Måneskin – they adore them.

“We get messages where people say, ‘my five-year-old is now obsessed with Rage Against The Machine because he listened to your song,’” says David. “Basically if you want to make it simple: we sound new for many different reasons – even though we are not new.”

Not all new fans are as welcome. After the Eurovision, French president Emmanuel Macron suggested Måneskin be disqualified because of the “fake cocaine” controversy [see below]. One of those rallying to their defence was right-wing politician Giorgia Meloni. She was subsequently appointed prime minister of Italy. The musicians weren’t aware of her intervention on their behalf before The Irish Times brings it up, and would rather Meloni keep her opinions to herself.

“I don’t want support from them,” says Raggi.

Måneskin’s music isn’t explicitly political. But they know where they stand. And it isn’t with Meloni’s populist Brothers of Italy party. Following her election, David took to Instagram to lament Italy’s drift to the right. “Today is a sad day for my country,” he wrote, linking to a story in newspaper La Repubblica.

“I would do it again. One hundred per cent,” he says, shrugging. “I don’t even know what to say. It’s hard not to say something offending [about Meloni and her supporters]. It’s clear that we’re making the same mistakes that we made in the past. Maybe we didn’t study the story well enough. Our generation is not going to make the same mistakes, hopefully. Italy has a very good taste for old-fashioned things. It doesn’t surprise me,” he continues, referring to Italy’s history of supporting right-wing politicians.

The band formed in Rome in 2016. David, Raggi and bassist Victoria De Angelis [who is under the weather and sitting out the interview] knew each other from high school. They met Ethan Torchio, from the suburb of Frosinone, after advertising for a drummer on Facebook.

De Angelis came up with their name. “Måneskin” is Danish for moonlight. The bassist suggested it, in part as tribute to her Danish mother who died when her daughter was 15. From there they had a rapid ascent. A stint busking in central Rome was followed by a tilt at X Factor Italy, where they blitzed their way to the final with molten versions of Somebody Told Me by The Killers and Take Me Out by Franz Ferdinand. Then came Eurovision and the global stage.

Måneskin are great fun. But the energy rippling through their music is interwoven with a fascination with the dark side of human nature. Gossip, for instance, interrogates the American dream and finds it wanting. “Welcome to the city of lies/ Where everything’s got a price,” they sing. They also take on Christianity. The Eurovision winner Zitti e Buoni contains the marvellously baroque lyric, “I wrote above a tombstone: ‘In my house there is no God.’”

“None of us is very Catholic. We don’t have that much influence. We have the opposite influence,” says David. “We feel the weight of the church on society, on our country. We see how late we are on many, many things because of the influence of the church. We have this hateful relationship.”

He pauses, at pains not to be misinterpreted. “I would like to make it clear that [Måneskin’s problems] are with the institution of the church. Nothing against religion. It’s a beautiful thing. The institution of the church and the money-laundering and all that… I’ll shut up.”

Eurovision was a baptism for Måneskin. However, their coming-out party threatened to turn sour amid an ersatz scandal over David supposedly taking cocaine. A photograph of the singer leaning over the table in the green room was seized on as evidence of illicit drug use.

The image was beamed around the world. There were calls – from Macron and others – for the group to be stripped of their title. Which is what prompted Meloni’s unwelcome intervention. David passed a drugs test and was cleared of any inappropriate behaviour. By then, though, Måneskin were all over the front pages and the talk of the internet. Did they fear they had blown it?

“We were laughing,” says David. “But we were pissed off. We were not worried about anything. The thing that disturbed me was that we had done something meaningful and great. We were a four-piece rock band from 20 to 22 years old who were breaking the hugest TV show in Europe. This was being overshadowed by some assholes who were not good at accepting the loss. I was pissed off that they had the power to do it. And that people were letting them do it.”

They made peace with the controversy by accepting that it was merely a downside of success. Once you achieve a certain level of celebrity, people will come after you.

“We know that being famous and winning and having a good career leads to criticism,” says David. “People are going to wait for you to make some mistake and talk s**t about you. It’s part of the game. You have to be stronger than it. If you are able to make irony about it and laugh about it… It’s kind of a superpower.”

There have been other controversies. Their performance of Supermodel from the 2022 MTV VMA Awards was heavily edited to conceal De Angelis’s exposed breast (though the cameras still caught David’s bare-bummed chap trousers).

“They have weird censorship rules,” says David of MTV and American broadcasting in general. “You can show guns and people dancing on huge dicks on stage. You cannot show a female nipple. I think it was worse for them than for us. We did our performance. They showed how it doesn’t make sense – their politics.”

Rush! copperfastens Måneskin’s status as the most exciting force in mainstream rock. It confirms, too, that they are magpies, with David drawing on everyone from Freddie Mercury to Kurt Cobain. And from Bono. U2 are adored in Italy and David says that their influence has seeped into his band.

“U2 have been so big it’s impossible not to be influenced. Indirectly, you’re influenced. The idea of the big frontman and blah blah blah. I think that indirectly it has been very strong. Also, putting the political into the music… they really changed that. Made it more common.”

The comparison goes beyond music. U2 were never much bothered about being cool. They never went out of fashion because they weren’t particularly fashionable to begin with. The same is true of Måneskin. From X Factor to Eurovision to interstellar fame, they have turned not being cool into a superpower, as David acknowledges.

“It’s a bit insecure to have this mindset [of wanting to be credible]. The idea that if you go to a pop environment, you’re not rock any more. It’s insecurity. Fortunately we were confident enough of our music and our identity to not think a stage or a TV show could change us. In fact, it didn’t happen. We brought ourselves everywhere we went. It was always the right thing to do. It is the only advice we could give to anybody. Bring yourself to the table. Don’t try to conform.”

Writer: Ed Power for The Irish Times

40 notes

·

View notes