#qiu ersao

Text

Women warriors in Chinese history - Part 2

(Part 1)

"However, court confessions, unofficial histories, and local gazetteers do reveal a host of women warriors during the Qing dynasty when patriarchal structures were supposedly most influential. Women in marginal groups were apparently not as observant of mainstream societal gender rules. Daughters and wives of “peasant rebels,” that is, autonomous or bandit stockades, were frequently skilled warriors. Miss Cai 蔡†(Ts’ai) of the Nian (Nien) “army,” for example, “fought better than a man, and she was especially fine on horseback. She was always at the front line, fighting fearlessly despite the large number of government troops.” According to a folktale, she managed to rout an invading government force of several thousand with a hundred men and one cannonball after her husband led most of the Nian off to forage for food.

Related to the female bandits were the women pirates among whom Zheng I Sao 鄭一嫂†(literally, Wife of Zheng I; 1775–1844) is the best researched. “A former prostitute … Cheng [Zheng] I Sao could truly be called the real ‘Dragon Lady’ of the South China Sea.” Consolidating her authority swiftly after the death of her husband, “she was able to win so much support that the pirates openly acclaimed her as the one person capable of holding the confederation together. As its leader she demonstrated her ability to take command by issuing orders, planning military campaigns, and proving that there were profits to be made in piracy. When the time came to dismantle the confederation, it was her negotiating skills above all that allowed her followers to cross the bridge from outlawry to officialdom.”

We know slightly more about some of the women warriors involved in sectarian revolts. Folk stories passed down orally are one of the sources. Tales that proliferated in northern Sichuan on the battle exploits of cult rebels of the White Lotus Religion uprising in Sichuan, Hunan, and Shaanxi beginning in the late eighteenth century glorify several women warriors. The tall and beautiful Big Feet Lan (Lan Dazhu 籃大足) and the smart and skillful Big Feet Xie (Xie Dazhu 謝大足) vanquished a stockade together; the young and attractive Woman He 何氏 could kill within a hundred feet by throwing daggers from horseback. The absence of bound feet in Big Feet Lan and Big Feet Xie suggests their backgrounds were either very poor, unconventional, or non-Han.

Sectarian groups accepted female membership readily, and many of these women trained in the martial arts. Qiu Ersao 邱二嫂†(ca. 1822–53), leader of a Heaven and Earth Society (Tiandihui 天地會) uprising in Guangxi, joined the sect because of poverty and perfected herself in the martial arts. Some women came to the sects with skills. Su Sanniang 蘇三娘, rebel leader of another sect of the Heaven and Earth Society, was the daughter of a martial arts instructor. Such sectarian rebel bands are frequently regarded as bandit groups. A history of the Taiping Revolutionary Movement refers to these two cult leaders as female bandit chiefs before they joined the Taipings.

Male leaders of religious rebellions frequently married women from families skilled in acrobatic, martial, and magic arts. These women tended to be both beautiful and charismatic. Wang Lun 王倫, who rebelled in 1774 in Shandong, had an “adopted daughter in name, mistress in fact,” by the name of Wu Sanniang 烏三娘 who was one of Wang’s most powerful warriors. Originally an itinerant performer highly skilled in boxing, tightrope walking, and acrobatics, she terrified the enemy with spellbinding magic. She brought a dozen associates from her old life to the sect, and they all became fearsome warriors known as “female immortals” (xiannü 仙女); three of them, including Wu Sanniang, lived with Wang Lun as “adopted wives” (ifu 義婦). A tall, white-haired woman at least sixty years old, possibly the mother of one of these acrobat-turned women warriors, wielded one sword with ease and two almost as effortlessly. Dressed in yellow astride a horse, hair loose and flying, she was feared as much for her sorcery as for her military skills. Her presence indicates that some of the women came from female-dominated itinerant performing families. Woman Zhang 張氏and Woman Zhao 趙氏, wives of Lin Zhe 林哲, another leader of the cult, were also known for being able to brandish a pair of broadswords on horseback.

Hong Xuanjiao 洪宣嬌†(mid nineteenth century), also known as Queen Xiao (xiaohou 蕭后), wife of the West King of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom (taiping tianguo 太平天國), was so stunningly beautiful and impressive in swordsmanship that she mesmerized the entire army during battles. The link between early immortality beliefs and shamanism also suggests that these women warrior “immortals” of sectarian cults may represent surviving relics of the female shamans who occupied high positions during high antiquity.

During the White Lotus Religion rebellion in Sichuan, Hunan, and Shaanxi beginning in 1796, five of the generals were at once leaders and wives of other leaders of the cult. They were Woman Qi née Wang (Qiwangshi 齊王氏; Wang Cong’er 王聰兒), Woman Zhang née Wang (Zhangwangshi 張王氏), Woman Xu née Li (Xulishi 徐李氏), Woman Fan née Zhang (Fanzhangshi 范張氏), and Woman Wang 王†née Li 李 (Wanglishi 王李氏). In the Heavenly Principle Religion (tianlijiao 天理教) rebellion that began in Beijing during 1713, the wife of its leader, Li Wencheng 李文成, led three invasions into the city. There was even a “Female Army” (niangzijun 娘子軍) within the Eight Trigrams (baguajiao 八卦教) uprising in Shandong during the Daoguang 道光† reign (1821–51). The female generals, Cheng Sijie 程四姐†and Yang Wujie 楊五姐, were particularly impressive when they wove among enemy forces in the style of “butterflies flitting among flowers,” wielding broadswords on horseback, their hairpins glittering in the light.

A number of female rebel leaders used religion and magic to buttress their power. Many claimed to be celestials and were leaders of sectarian cults (...). Chen Shuozhen 陳碩貞†(?–653) mobilized a peasants’ uprising by declaring that she had ascended to heaven and become an immortal. Tang Sai’er (ca.1403–20), a head of the White Lotus Religion (bailianjiao 白蓮教), designated herself as a “Buddhist Mother” (fuomu 佛母). The spellbinding old woman warrior in Wang Lun’s Clear Water Religion (qingshuijiao 清水教) sect was known to the rebel community as a reincarnation of the highest White Lotus deity, the Eternal Venerable Mother (wusheng laomu 無生老母). Wang Lun relied on her for performing magic and the rituals for calling on their supreme deity. Woman Wang née Liu (wangliushi 王劉氏), one of the numerous female leaders of the White Lotus Religion revolt, also titled herself the Eternal Venerable Mother. Wang Cong’er (1777–98), originally an itinerant entertainer, became the commander in chief of the rebel army she launched with her husband, a master in the White Lotus Religion.

Indeed, itinerant performers such as Wu Sanniang mentioned above were frequently trained in the martial arts since childhood and must have been skilled at performing magic tricks as well. Lin Hei’er 林黑兒†(?–1900), leader of Red Lanterns (hongdengzhao 紅燈照), the young women’s branch of the Boxer’s Movement (yihetuan 義和團), was also originally an itinerant entertainer (her husband was a boatman). Designating herself the Holy Mother of the Yellow Lotus (huanglian shengmu 黃蓮聖母), she taught her followers the skills of wielding swords and waving fans as well as magic to defeat their enemies. Wang Nangxian 王囊仙†(literally, Goddess Nang, 1778–97), an ethnic minority of the Miao tribe, was worshipped as a goddess by her tribesmen before she led them in revolt against the Chinese government."

Chinese shadow theatre: history, popular religion, and women warriors, Fan Pen Li Chen

#history#women in history#women warriors#warriors#warrior women#china#chinese history#asian history#historyblr#qing dynasty#19 century#18th century#Wang Cong’er#hong xuanjiao#su sanniang#qiu ersao#tang sai'er#asia#Zheng Yi Sao

177 notes

·

View notes

Photo

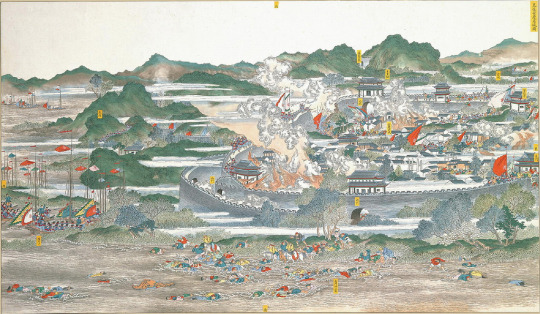

Women of the Taiping Rebellion: Qiu Ersao

This is the third article of my series about the women who fought during the Taiping Rebellion in China. For more information about the general context, the Taiping’s female soldiers and prominent female generals, you can check my articles on Hong Xuanjiao and Su Sanniang.

Qiu Ersao (c. 1822-1853), born in Guangxi Province, was the leader of an important anti-Qing rebel force.

She came from a poor family and was married as a child. Her husband became addicted to opium and she was the family’s sole breadwinner, surviving by selling sweets on the market. Qiu Ersao grew more and more indignant at the corruption of the Qing officials who made the peasants suffer. She thus decided to join a religious secret society, the Tiandihui, where she learned martial arts.

In autumn 1849, several anti-Qing uprisings broke in the province. Qiu Ersao seized the opportunity and asked the Tiandihui members to revolt. Almost a thousand of them joined her. She learnt of the Taiping Rebellion during November 1850 and led her troops to join the rebels. She was received by their leader Hong Xiuquan and was put in charge of the outer defense line in Dongxiangxu. However, the Taiping religious doctrine conflicted with the Tiandihui one. This prompted Qiu Ersao to leave the rebellion.

On June 4 1851, Qin Ersao joined forces with another Tiandihui army. They crossed the Yu river and defeated the Qing army at Tantangxu. Qiu Ersao knew how to inspire her followers. She was dressed in the garb of an archer, her hair adorned with red silk pompons, and wore a longsword. She was also an extremely gifted orator. People forgot that she was an illiterate woman when they listened to her. In Tantangxu, she executed the corrupt officials, opened the government’s warehouse and gave distributed its content to the poor. She recruited new troops who marched under her motto: “Overthrow the Qing government and save the people”.

In Autumn 1853, Qiu Ersao and her 3000 soldiers attacked Wupingli where they were defeated. Qiu Ersao went to Shilong, but was defeated again due to the local militia’s cannons. She fell from her horse and died during the fighting.

Bibliography:

Mao Jiaqi, “Qiu Ersao”, in: Lee Lily Xiao Hong, Lau Clara, Stefanowska A. D. (dir.), Biographical dictionary of Chinese women: The Qing Period, 1644-1911

#qiu ersao#China#19th century#Chinese history#Taiping rebellion#Qing dynasty#women in war#female soldiers#badass women#history#war#military history#herstory#women's history#warrior women#women warriors

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Zhou Xiuying - “Ms. Broadsword Xiu”

Zhou Xiuying (? - 1855) was born in Hangdou, present-day Shanghai, China. She was a contemporary of rebel female generals Qiu Ersao, Su Sanniang and Hong Xuanjiao.

Xiuying was born to a peasant family and her father, Zhou Lichun, was the chief of the local branch of the Tiandihui (society of heaven and earth). She learned martial arts alongside her adopted sister, Zhou Feixia. Xiuying preferred the broadsword while Feixia specialized in the spear.

In 1852, the local magistrate pressured the peasants to pay a grain tax they had been exempted from. Xiuying and her father decided to revolt and she placed herself at the rebel’s head. The peasants, armed only with iron-toothed rakes, defeated the soldiers. This exploit was celebrated in a folk song: “Songjiang soldiers with shields were no equal to folks with rakes”.

Xiuying knew that the government would retaliate. She had the peasants make weapons and prepare themselves to fight. In autumn, more than a thousand soldiers were sent to quell the rebellion. Xiuying led once again the peasants in battle and defeated the enemy. From now on, she was known as “Dadao Xiuguniang” (Ms. Broadsword Xiu). A folk song praising her courage in battle still circulates today: “True heroine Zhou Xiuying/clad in red trousers and fitted top/carries a big sword of 120 jin (60 kgs)/fighting over the Tangwan bridge with her “kai simen””.

In 1853, her father led another revolt and, with the help of other societies, occupied the county seat. Xiuying fought valiantly. The Qing government sent more troops and outnumbered the rebels. Zhou Lichun and Zhou Feixia were killed in the ensuing fight. Xiuying retreated with a part of the army to Shanghai county where she allied with the Shanghai Small sword society. She kept distinguishing herself in battle and became a renowned female general.

Xiuying encouraged the women of Shanghai to fight in the defense. Some of them answered her call and, each leading fifty men, went out of the city to engage and destroy the enemy forces. In 1854, Xiuying had iron barbs placed on the city’s walls. The enemy was lured into her trap and she led 200 rebels in a surprise attack.

Since the French had a concession in Shanghai and sent troops to support the Qing army, Xiuying and her female soldiers fought against the foreigners. Eyewitnesses said that she “kept a thousand soldiers at bay”. Foreign journalists wrote about those female fighters that they were “truly comparable to the Amazons of ancient Greece in their valor and resolution”.

When the rebel army experienced a food shortage, Xiuying and her women resolved to die rather than surrender. They collected grassroots, the bark of trees and captured mice and birds. On February 17,1855 the rebels ran out of food and retreated. The enemy followed them and a battle ensued. Xiuying fought on horseback, but her mount stumbled and she was killed.

Bibliography:

Ma Honglin, “Zhou Xiuying”, in: Lee Lily Xiao Hong, Lau Clara, Stefanowska A. D. (dir.), Biographical dictionary of Chinese women: The Qing Period, 1644-1911

#Zhou Xiuying#19th century#Chinese history#china#Qing dynasty#history#women in history#warrior women#badass women#historyblr#history edit#martial arts#war#military history#asian history#asia

51 notes

·

View notes