#pukhto nazam

Text

په اردو مې ژبه نه چلي صاحبه

په پښتو خبرې اوکړم اجازت دې؟

[pa urdu mi jaba na chali sahiba,

pa pukhto khabari ukram ijazat de?]

urdu doesn't go quite well with my tongue,

do you mind, good sir, if i speak in pashto?

—hamza baba

#pashto#pashto shayari#pashto poetry#pashto language#pashto ghazal#pashto nazam#pashto tappa#pashto tappay#pashto landai#pukhto#pukhto shayari#pukhto poetry#pukhto language#pukhto ghazal#pukhto nazam#pukhto tappa#pukhto tappay#pushto#pushto language#pushto shayari#pushto poetry#pushto ghazal#pushto nazam#pushto tappa#pushto tappay#pashto lines#pushto lines#pukhto lines#hamza baba#hamza shinwari

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Intro to Pashto

Pashto (پښتو) also known as Pushtu, Pushto, Pukhto, Afghan is a member of the southeastern Iranian branch of Indo-Iranian languages spoken in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran. There are two major dialects of Pashto: Western Pashto spoken in Afghanistan and in the capital, Kabul, and Eastern Pashto spoken in northeastern Pakistan. Most speakers of Pashto speak these two dialects. Two other dialects are also distinguished: Southern Pashto, spoken in Baluchistan (western Pakistan and eastern Iran) and in Kandahar, Afghanistan.

There are also communities of Pashto speakers in the northeast of Iran, Tajikistan and India, as well as in the UAE, Saudi Arabia and a number of other countries.

The name Pashto is thought to derive from the reconstructed proto-Iranian form, parsawā Persian language. In Northern Afghanistan speakers of Pashto are called Pakhtūn; in Southern Afghanistan they are known as Pashtūn, and as Pathān in Pakistan.

History of Pashto:

The first written records of Pashto are believed to date from the sixteenth century and consist of an account of Shekh Mali's conquest of Swat. In the seventeenth century, Khushhal Khan Khattak, considered the national poet of Afghanistan, was writing in Pashto. In this century, there has been a rapid expansion of writing in journalism and other modern genres which has forced innovation of the language and the creation of many new words.

Traces of the history of Pashto are present in its vocabulary. While the majority of words can be traced to Pashto's roots as member of the Eastern Iranian language branch, it has also borrowed words from adjacent languages for over two thousand years. The oldest borrowed words are from Greek, and date from the Greek occupation of Bactria in third century BC. There are also a few traces of contact with Zoroastrians and Buddhists. Starting in the Islamic period, Pashto borrowed many words from Arabic and Persian. Due to its close geographic proximity to languages of the Indian sub-continent, Pashto has borrowed words from Indian languages for centuries.

Pashto has long been recognized as an important language in Afghanistan. Classical Pashto was the object of study by British soldiers and administrators in the nineteenth century and the classical grammar in use today dates from that period.

In 1936, Pashto was made the national language of Afghanistan by royal decree. Today, Dari Persian and Pashto both are official national languages.

Pashto Literature :

The history of Pashto literature spreads over five thousands years having its roots in the oral tradition of tapa. However, the first recorded period begins with Bayazid Ansari, who founded his own Sufi school of thoughts and began to preach his beliefs. He gave Pashto prose and poetry a new and powerful tone with a rich literary legacy. Khair-ul-Bayan, oft-quoted and bitterly criticized thesis, is most probably the first book on Sufism in Pashto literature. Among his disciples are some of the most distinguished poets, writers, scholars and sufis, like Arzani, Mukhlis, Mirza Khan Ansari, Daulat and Wasil, whose poetic works are well preserved. Akhund Darweza, a popular religious leader and scholar gave a powerful counterblast to Bayazid's movement in the shape of Makhzanul Islam. He and his disciples have enriched the Pashto language and literature by writing several books of prose.

The second period is perhaps the most prolific and glorious one. Khushal Khan Khattak, father of Pashto, is the central figure of this period. He introduced new forms and modern trends in Pashto literature. The Persian ghazal, rubai and masnavi influenced the Pashto poets and writers of this period. The Sufism of Hafiz Shirazi found an echo in Rahman Baba's works. Similarly Abdul Qadir Khattak, Ashraf Khan Hijri, Kazim Khan Shaida, Ma`azullah Khan, Ahmad Shah Abdali and many others have left valuable treasure of literature in Pashto. This period was dominated by poetry, but prose also held an important place. Romantic stories and versified fiction gained popularity towards the end of this period and continued with some modifications throughout the second period and even into the third which reached in the evolution of Pashto literature came to a close with the death of great warrior-king and poet, Ahmad Shah Abdali.

The fourth period begins with the dawn of the twentieth century. The Khilafat and Hijrat Movements gave rise to a type of poetry that called out to soldiers of freedom. This generation of Amir Hamza Khan Shinwari and Dost Mohammed of young poets enriched the poetry of the period with new idealism.The twentieth century proved very fertile, rich and flourishing for Pashto literature because it gave new genres and literary forms like Drama, Short Story, Novel, Takl, Character-Sketch, Travelogue, Reportage, Satire, Azad Nazam and Haiku. A large number of literary organizations also took birth in this century. Qalandar Moomand compiled the first ever Pashto to Pashto dictionary (Daryab) while Hamish Khalil compiled a comprehensive directory of Pashto poets and writers (Da Qalam Khawandan) containing necessary information about more than three thousand men of letters.

The younger generation of poets carried forward the legacy of these early poets and writers with great enthusiasm. The contributions of Kabul Adabi Tolana and Pashto Academy are immense.

The Afghan scholars, researchers, linguists, historians, poets and writers namely Gul Bacha Ulfat, Adul Hai Habbibi, Adur-Rauf Benawa, Qayam -u- Din Khadim, Adul Shakoor Rashad, Sadiqullah Rashtin and many others have a major share in promoting Pashto language and literature.

It is a beautiful language, rich in culture and tradition. We hope to help you in the journey of learning Pashto and we hope you benefit from us and most importantly, enjoy learning!

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

حيـران يـم مونـځ به يې قبليـږي که نه

د چا په زړه کښي چي د چا تصوير وي

[hairaan yam munz ba ye qablegi ka na,

da cha pa zrha ki chi da cha taswir wi]

i wonder if their prayers will be accepted or not;

those who keep, in their heart, a picture of someone

—@malghalari

#pashto#pashto shayari#pashto poetry#pashto literature#pukhto#pukhto shayari#pukhto literature#pashtuns#pukhtoon#pukhto poetry#pukhto ghazal#pashto ghazal#pukhto tappa#pashto tappa#pukhto nazam#pashto nazam

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

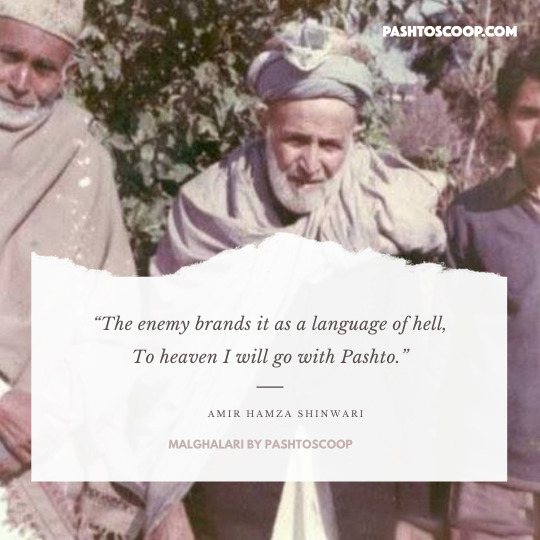

Remembering Hamza Baba

Amir Hamza Shinwari, or Hamza Baba as he is known, was born in December 1907, in the house of Malik Baz Mir Khan — the chief of the Ashraf Khel tribe of Shinwari Pashtuns.

During his early days, Hamza worked in the railways and even travelled to Mumbai to try his luck in the Bollywood film industry.

He started writing poetry in Urdu when he was only in grade five. But his spiritual guide, Syed Abdul Sattar Shah Baacha, asked him to switch to his mother tongue — Pashto.

Baba may not have been a first-rate Urdu poet, but once he started composing verses in Pashto, he perfected Pashto ghazal to the extent that Pashtun critics conferred on him the title, Baba-e-Pashto ghazal (the father of Pashto ghazal).

Refering to his title, Hamza Baba says:

[Sta pa anango ki da Hamza da wino sra di,

Ta shwe da pukhto ghazala zwan za di Baba kram!]

The crimson of color in your cheeks,

Is the color of the blood of Hamza.

You came of age, Pashto Ghazal,

But turned me into a baba (an old man)

Hamza Baba amalgamated the chivalric spirit of Khushhal Khan Khattak, the humility of Rahman Baba and the refined romanticism of Abdul Hameed Baba into Pashto verse due to which Pashto ghazal poetry attained new heights.

Hamza Baba also heralded a new era in Pashto prose and fiction. Being a prolific writer, Baba contributed to almost every literary genre in Pashto — short story, novel, drama, literary criticism, satirical essays, pen-portraits and free verse.

He, in fact, Pashtunised Pashto ghazal and nazm, consciously presenting a soft image of the Pashtun nation and keeping the Sufi trend of Rahman Baba alive with a new vision and approach.

Baba considered Islam and Pakhtunwali as flip sides of a coin and negated aggressive nationalism in his writings. He wanted Pukhtuns to maintain their true identity and uphold high social and moral values to safeguard humanity against all kinds of prejudices.

Hamza Shinwari Baba was, undoubtedly, a flowering spring of extraordinary genius, and has become an icon of universal admiration beyond the barriers of cast, language, color, or creed.

Dr. Qabel Khan comments that Hamza Baba "is a virtual stream of friends of friends, disciples, admirers, and well-wishers. Hardly there was any day in his life he was not visited by his admirers and readers…his knowledge of Pashto is simply encyclopedic."

Courtesty: Haroon Shinwari, Hidayat Khan, ThePukhtoonkhwa blog

#hamza baba#hamza shinwari#hamza baba ghazal#baba e ghazal#amir hamza shinwari#ameer hamza shinwari#pashto poet#pashto history#pashtun history#pashto ghazal#pashto poetry#pashto shayari#pashto literature#pashto nazam#pushto#pusho ghazal#pustho shayari#pushto poetry#pukhto#pukhto poetry#pukhto shayari#pukhto ghazal#pashto tappa#pashto tappay#pukhto tappa#pukhto tappay#pashto language#pashto

8 notes

·

View notes