#northern woodland white-tailed deer

Text

As climate change pushes deer north, other animals may lose out. (Washington Post)

As winters warm, white-tailed deer push ever northward in North America. A recent study in Global Change Biology suggests that climate change is driving these habitat shifts — changes that may further threaten woodland caribou in northern Canada.

The study used 300 remote cameras across the northern Alberta-Saskatchewan border, collecting nearly 80,000 images of white-tailed deer from 2017 to 2021 and using the images to estimate white-tailed deer density in the region over time.

Researchers chose the area because it contains a variety of landscapes altered by humans, providing an opportunity to tease out whether climate or human-caused habitat changes have a bigger influence on deer density.

Habitat alteration by humans affected the number of deer, but the effects of climate were stronger, the scientists said. When the winter was more severe, the researchers found, deer densities declined regardless of habitat alteration due to human activity. Warmer winters, in contrast, meant higher numbers of deer.

Because climate change is expected to reduce winter severity, the researchers predict that deer will push farther north as less severe winters make the habitat there more appealing.

That could have serious effects for the other animals that live in the deer’s new homes.

“Deer are ecosystem disruptors in the northern boreal forests,” Melanie Dickie, a doctoral student at the Wildlife Restoration Ecology Lab at the University of British Columbia’s Okanagan campus and a co-author of the study, explains in a news release. “Areas with more deer typically have more wolves, and these wolves are predators of caribou — a species under threat. Deer can handle high predation rates, but caribou cannot.”

Woodland caribou in northern Canada’s forests have long been threatened by habitat loss. According to Natural Resources Canada-Canadian Forest Service, these caribou tend to avoid areas with shrubs favored by deer. Parasites and diseases can also accompany deer expansion, the researchers note.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deercember Day Twenty-Two: Northern Woodland White-tailed Deer | Fireflies

The white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), also known commonly as the whitetail, is a medium-sized species native to North America, Central America, and South America as far south as Perú and Bolivia. The species is so named because the underside of its tail is covered with white hair, and when it runs it often holds its tail erect so that the white undersurface is visible; this behaviour, used to indicate danger, is often referred to as "flagging". In North America, the species is widely distributed east of the Rocky Mountains as well as in the southwest throughout Arizona and most of Mexico, though not within southern California. Across its distribution, the species has evolved into numerous subspecies; there are currently anywhere between twenty-six to thirty-eight subspecies, depending on the manner of classification. The largest and darkest, the northern woodland white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus borealis), is native throughout the northeastern United States and into Canada. Their phenotype follows the general rule that the further from the equator a population resides, the larger they tend to be; likewise, populations who live in a high-humidity environment, or who spend most of their time in conifer forests, tend to be darker in colouration. Spending the majority of the day concealed in the forest, these deer are crepuscular animals—most active around sunrise and sunset—with frequent nocturnal activity who, under the cover of night, venture out into more open areas to graze. More information here.

Reference: Deer, Fireflies, and Background.

#flashing#cw flashing#flashing cw#flashing lights#cw flashing lights#flashing lights cw#you know I couldn't resist another little animation#despite being rather simple‚ I managed to start this around 10p‚ faff about for an hour or so‚ and decide at 2:45a to animate this#so we're still working on that whole “sleep schedule” thing#still‚ I enjoy the still version‚ and despite the simplicity I think the animation is cute#who doesn't love fireflies#Deercember#realHum#Art#Drawing#deer#deer art#white-tailed deer#whitetailed deer#whitetail deer#whitetail#northern woodland white-tailed deer#northern woodland whitetail#Odocoileus virginianus#Odocoileus virginianus borealis

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Climate of Illinois

See Weather Forecast for Illinois today: https://weatherusa.app/illinois

The geographical position and elongated north-south axis of Illinois result in significant regional temperature variations. Throughout the state, seasonal temperature fluctuations are pronounced, characterized by cold, snowy winters and hot summers, although the influence of Lake Michigan helps temper extremes. In the northern part of the state, mean winter temperatures hover around 22 °F (-6 °C), contrasting with around 37 °F (3 °C) in the south. Similarly, summer temperatures average at approximately 74 °F (23 °C) in the north and 80 °F (27 °C) in the south. Annual precipitation also exhibits a gradient, with around 34 inches (864 mm) in the north and 46 inches (1,170 mm) in the south. The length of the growing season varies across the state, ranging from 205 days in the south to 155 days in the northernmost counties.

See more: https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-60026

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-60050

Illinois boasts distinct vegetational regions, primarily characterized by the tallgrass prairie in the northern and central areas and the oak-hickory forest in the western and southern regions. However, only small remnants of the original tallgrass prairie remain, with some areas undergoing restoration efforts. Notably, the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie, located near Joliet, stands as the largest restored prairie in the state.

Historically, before European settlers arrived in the 17th century, oak-hickory forests were prevalent even in the northern regions of Illinois. However, the settlers, driven by the need for wood for fuel, construction, and the lumbering industry, extensively cleared forests, resulting in a significant reduction of forest cover. Presently, approximately 6,200 square miles (16,000 square km) of forests remain in Illinois, with Shawnee National Forest accounting for around 1,100 square miles (2,800 square km) of them.

See more: https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-60078 https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-60139

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-60148

Due to its geographic length, Illinois exhibits a unique blend of Northern and Southern plant life. This diversity is evident in the wide array of wildflowers and trees found across the state. Species such as white pines, tamaracks, walnuts, cypresses, and tupelos thrive in Illinois, representing a rich tapestry of flora that contributes to the state's ecological heritage.

Before 1800, Illinois was teeming with abundant wildlife, populating the prairies and forests with iconic species like bison, bears, wolves, mountain lions (pumas), porcupines, and elk. However, due to human activities and habitat destruction, these once-thriving populations dwindled and disappeared. Deer, for instance, went extinct in 1910, but efforts by the state department of conservation in 1933 saw the reintroduction of small herds, leading to the establishment of a growing deer population. By the early 21st century, the number of white-tailed deer in Illinois had surged into the hundreds of thousands.

While some species have experienced successful reintroduction efforts, others, like coyotes and foxes, have adapted to survive in woodlands, natural areas, and increasingly, urban environments. Game birds such as quail and pheasant, though not as plentiful as in the past, still inhabit the region, while waterfowl populations thrive during spring and fall migrations.

However, pollution has taken its toll on aquatic life, nearly wiping out many species of fish. Despite this, bullheads, carp, catfish, white and yellow bass, and walleye continue to thrive in Illinois' waters, offering opportunities for fishing enthusiasts and serving as vital components of the state's ecosystem.

See more: https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-60163

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-60188

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-60190

The optimal times to visit Illinois are typically from April to mid-May in the spring and from September to October in the fall. During these seasons, the weather is generally more agreeable compared to the extreme heat of summer and the cold of winter.

Spring offers pleasant temperatures and vibrant blooms, making it an ideal time for outdoor activities. However, late spring and early summer can be wet, with occasional thunderstorms and the risk of flooding.

Autumn in Illinois is characterized by colorful foliage, comfortable mornings, and breezy evenings, providing a picturesque backdrop for exploration.

Conversely, late fall sees temperatures dropping rapidly, accompanied by cold and windy conditions.

Summers in Illinois are often hot and humid, with large crowds and higher prices for attractions. Thus, visitors may find spring and fall to be more budget-friendly options.

Overall, visitors can enjoy lighter crowds, pleasant weather, and scenic beauty during the spring and fall months, making them the preferred times to explore Illinois.

See more: https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-60440

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-60446

0 notes

Text

Kishwaukee Headwaters Conservation Area

Kishwaukee Headwaters Conservation Area is a 277 acre preserve located just north of Woodstock, Illinois. The preserve protects the headwaters of the Kishwaukee River and is home to a variety of plant and animal species. The Kishwaukee River is a major tributary of the Rock River and provides drinking water for over 300,000 people in northern Illinois.HistoryThe Kishwaukee Headwaters Conservation Area was established in 2004 by the Openlands Project and the City of Woodstock. The preserve is open to the public for hiking, fishing, picnicking, and bird watching. There are several miles of trails that wind through the preserve and offer views of wetlands, prairies, and woodlands.FishingThe Kishwaukee Headwaters Conservation Area is a popular spot for fishing. The Kishwaukee River is stocked with trout each spring and is also home to bass, catfish, and panfish. A valid Illinois fishing license is required to fish in the preserve.HikingThere are over five miles of trails at the Kishwaukee Headwaters Conservation Area. The trails wind through prairies, wetlands, and woodlands and offer views of wildlife and native plants. Hikers are encouraged to take only photos and leave only footprints while visiting the preserve.PicnickingPicnic tables are available on a first-come, first-served basis at the Kishwaukee Headwaters Conservation Area. Picnickers are encouraged to pack out all trash and refrain from disturbing wildlife.Bird WatchingThe Kishwaukee Headwaters Conservation Area is home to a variety of bird species including warblers, woodpeckers, and hawks. Bird watchers are encouraged to bring binoculars and a field guide to help identify the different species.WildlifeThe Kishwaukee Headwaters Conservation Area is home to a variety of plant and animal species. White-tailed deer, red foxes, and coyotes are just some of the animals that call the preserve home. The preserve is also home to over 200 species of native plants.Visiting the Kishwaukee Headwaters Conservation AreaThe Kishwaukee Headwaters Conservation Area is open daily from dawn to dusk. The preserve is located at 1215 Dean St, Woodstock, IL 60098.

Please visit on of our regular supporters

Be sure to visit other attractions too!

1 note

·

View note

Text

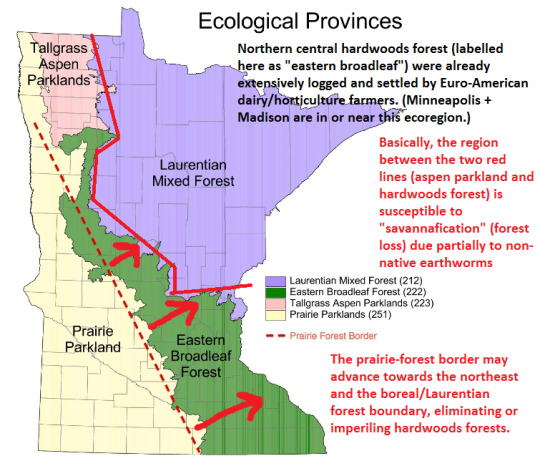

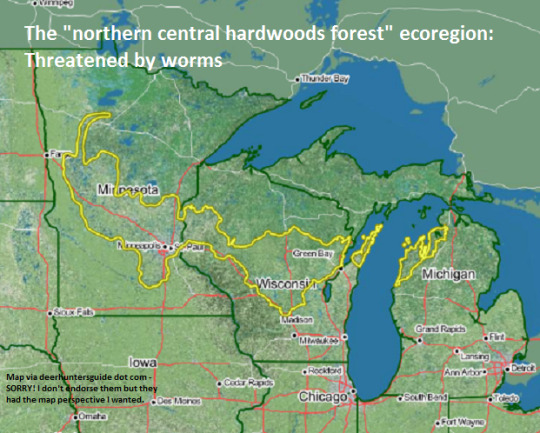

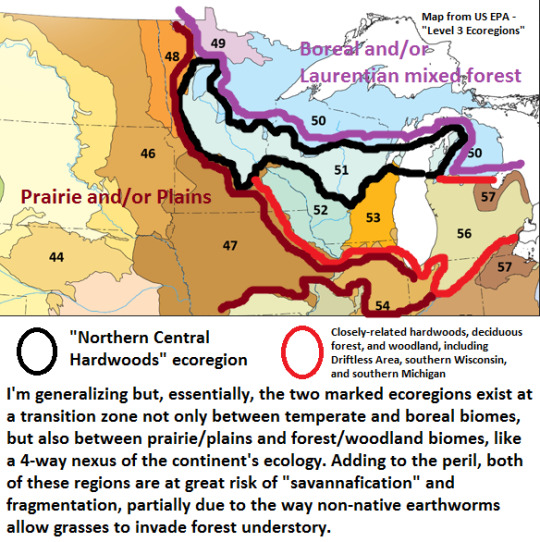

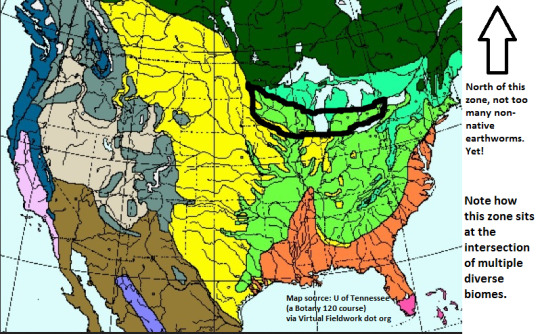

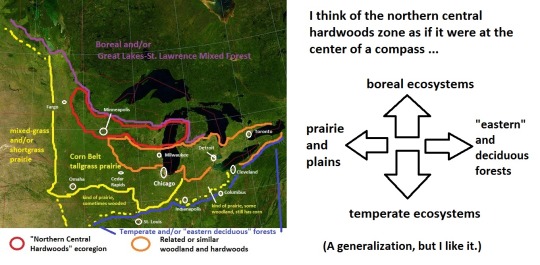

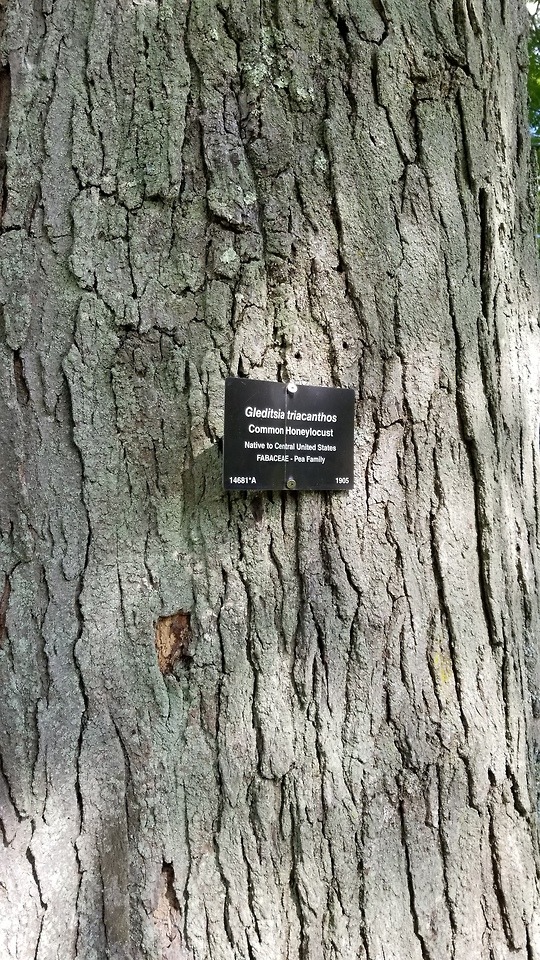

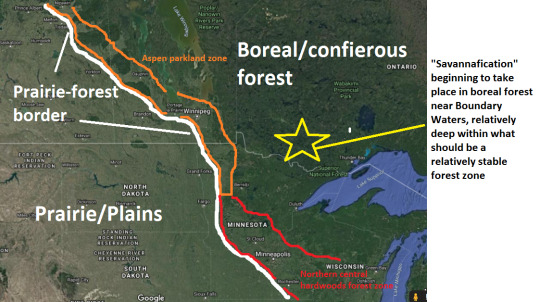

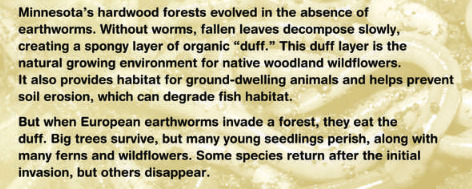

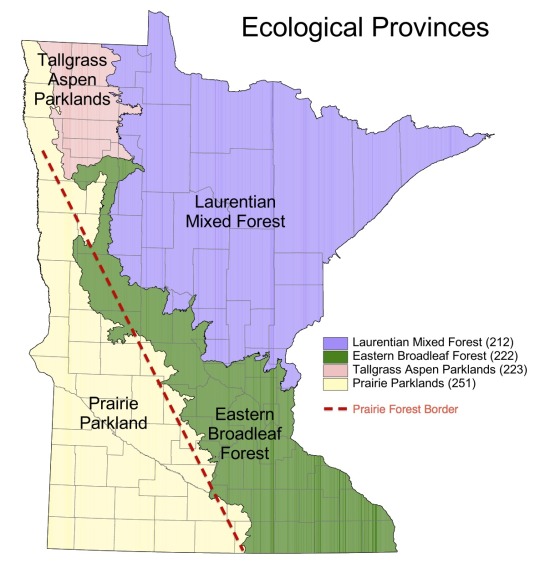

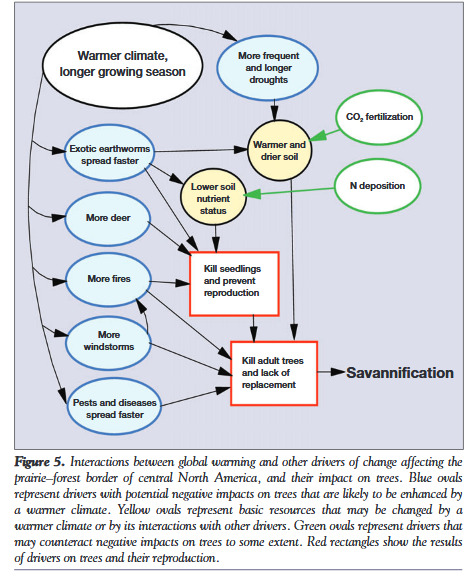

More on worm invasion, regarding “savannification” and why the transition zone between boreal forest and temperate woodlands near the “northern central hardwoods forest ecoregion” of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan is a critical region for minimizing the damage from the northward expansion of non-native earthworms: Since non-native worms have been seemingly omnipresent and well-established across temperate North America - for several centuries, in many places - it’s worth noting that there is still potential future damage that might be mitigated by human action against worm expansion. Apparently, non-native earthworms can contribute significantly to devegetation of boreal and mixed forest near Minnesota’s Boundary Waters region, and the expansion of tallgrass prairie and oak savanna into previously boreal climates and forested landscapes. There’s a good reason that so much earthworm ecology research is based at schools in Minnesota, Michigan, and Ontario. So here are some more horrible map abominations I made with the beloved program M!crosoft Paint (the working-class GIS, lol) regarding the danger of worms in Great Lakes, Midwest, and boreal ecosystems.

-----

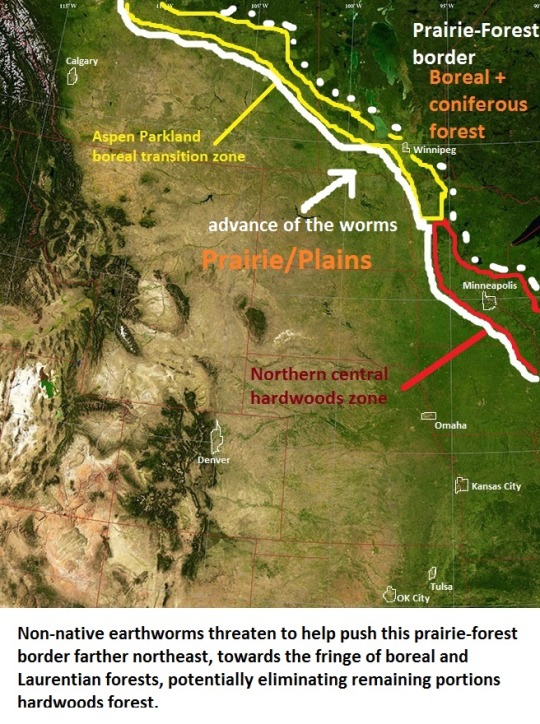

“European earthworms, principally the nightcrawler (Lumbricus terrestris), leaf worm (Lumbricus rubellus), and angleworms (Aporrectodea spp), are invading forests along the entire prairie-forest border, including boreal forests from Alberta to northern Minnesota, and hardwood forests from Minnesota to Indiana. The northern part of the prairie-forest border, from northern Wisconsin through Alberta, has no native earthworms.” [Source. An influential research paper. Lee E. Frelich and Peter B. Reich. “Will environmental changes reinforce the impact of global warming on the prairie-forest border of central North America?” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment (2009).]

From the same article:

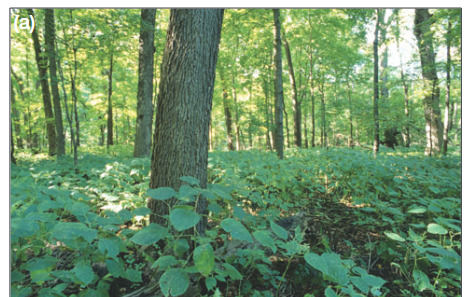

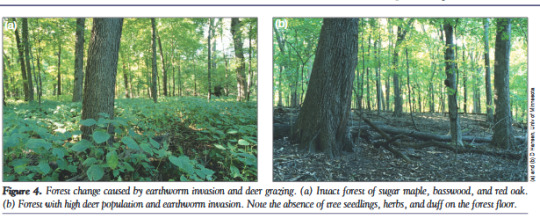

Caption, LE Frelich and PB Reich: “Forest change caused by earthworm invasion and deer grazing. (a) Intact forest of sugar maple, basswood, and red oak. (b) Forest with high deer population and earthworm invasion. Note the absence of tree seedlings, herbs, and duff on the forest floor.”

“Savannification” of North America’s northern prairie-forest border zone (in Minnesota, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta) is soon expected to increase significantly due to the combination of climate crisis; industrial monoculture; white-tailed deer overabundance and overgrazing; and introduced exotic earthworm species. In other words, aspen parkland and northern central hardwoods forest, in the region where boreal biomes meet temperate biomes near Winnipeg, could be converted into savanna.

One major reason for forest loss and the encroachment of savanna is the death of the understory and forest floor of northern central hardwoods environments in Minnesota and Wisconsin; the way the non-native earthworms destroy understory plants allows the related encroachment of grasses in their place (creating a self-sustaining cycle and advancement of prairie/woodland replacing forest).

--

Guess I’d recommend this article, which deals with the boreal-temperate border and the prairie-forest border in Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Minnesota, and Wisconsin.

The magic words you were waiting for:

[Free PDF]

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Table Rock Lake Clans - List of Prefixes by Color

An exhaustive list of all possible prefixes in the Clans of Table Rock Lake

I may make a category list soon

Black

Ani - derived from the grove-billed ani

Ant - used for small cats

Bat

Bear - used for big cats - derived from the American black bear

Beetle

Black

Bramble - refers to the ripened fruit - derived from the blackberry bramble

Cherry - refers to the fruit - derived from the black cherry

Cicada - used for tabbies

Coal

Coot - derived from the American coot

Cormorant - derived from the double-crested cormorant

Cricket - used for solids or tabbies

Crow

Dark

Duck

Eel - used for long-bodied cats

Evening

Flint

Goose - used for black and white cats

Grackle - derived from the common grackle

Hornet

Loon - used for black and white tabbies - derived from the common loon

Mink - derived from the American mink

Night

Raven

Shade

Shadow

Skunk - used for black tabbies or black and white cats - derived from the striped skunk (tabby) and the spotted skunk (bicolor)

Smoke - used for tabbies

Soot

Spider

Starling

Storm

Swift - used for black and white cats

Turtle

Vulture - derived from the turkey vulture

Wasp

Weevil

Willow - refers to the bark - used for black longhairs - derived from the black willow

Brown

Bat

Bear - used for large brown cats - derived from the grizzly bear

Beaver

Beetle

Bison - used for big cats

Bittern - used for light brown tabbies with white - derived from the American bittern

Brown

Chicken - used for light brown spotted tabbies with white - derived from the prairie chicken

Chipmunk - used for small tabbies

Cricket - used for tabbies

Cougar - used for large light brown cats

Deer - used for light brown cats - derived from the white-tailed deer

Duck

Dust

Eagle - used for brown and white cats - derived from the bald eagle

Elk - used for large cats

Frog - used for spotted tabbies

Grebe - derived from the horned grebe

Grouse - used for spotted brown cats - derived from the ruffed grouse

Harrier - used for brown and white cats - derived from the Northern harrier

Hawk - used for brown and white cats - derived from the red-tailed hawk

Honey - used for golden-brown cats

Lizard - used for tabbies

Mantis

Mink - derived from the American mink

Moth - used for tabbies

Mouse - derived from the house mouse

Mud

Nightjar - used for spotted brown tabbies - derived from the common nighthawk

Oak - refers to the bark - used for tabbies - derived from the black oak

Oat - refers to the flower - derived from the wild oat

Pecan - used for tabbies - derived from the pecan tree

Quail - used for spotted and white tabbies - derived from the bobwhite quail

Rabbit - derived from the cottontail rabbit

Rail - used for dark brown spotted tabbies - derived from the king rail

Rat - derived from the brown rat

Rock

Rush - refers to the flowers - derived from the common rush

Snail

Soil

Sparrow - used for brown and white tabbies - derived from the house sparrow

Spider

Stone

Sycamore - used for big tabbies - derived from the American sycamore

Tawny - used for light brown cats

Teal - derived from the cinnamon teal

Thrush - used for spotted light brown and white tabbies - derived from the wood thrush

Turkey - used for big cats

Turtle

Walnut - refers to the nuts - derived from the black walnut

Weasel - used for brown and white cats - derived from the long-tailed weasel

Weevil

Wigeon - derived from the American wigeon

Wren - used for brown and white tabbies

Reddish-Brown

Alder - refers to the bark - used for tabbies - derived from the hazel alder

Cardinal - refers to the female of the species

Cedar - refers to the bark - used for tabbies - derived from the red cedar

Clay

Crane - derived from the sandhill crane

Ibis - derived from the white-faced ibis

Owl - used for spotted reddish-brown tabby and white cats - derived from the screech owl

Pheasant - used for spotted tabbies - derived from the common pheasant

Gray-Brown

Armadillo - used for tabbies

Bass

Birch - refers to the bark - derived from the river birch

Boulder - used for large cats

Coyote

Dove

Elm - refers to the bark - used for tabbies - derived from the American elm

Hare - derived from the American desert hare

Hickory - refers to the bark - used for tabbies - derived from the bitternut hickory

Kinglet

Lark - used for grayish-brown and white cats - derived from the horned lark

Lynx - used for spotted tabbies - derived from the bobcat

Magnolia - refers to the bark - used for tabbies - derived from the cucumber magnolia

Mole - derived from the Eastern mole

Pike - used for spotted tabbies

Pine - refers to the bark - derived from the shortleaf pine

Sand

Shell - used for tabbies

Vole - derived from the prairie vole

Warbler

Gray

Badger - used for tabbies - derived from the American badger

Bass

Bergamot - refers to the flowers - derived from the plant

Blizzard - used for spotted light gray tabbies

Boulder - used for big cats

Burdock - derived from the greater burdock

Carp

Chickadee - used for small gray and white cats - derived from the Carolina chickadee

Cinder

Coyote

Dark - used for dark gray cats

Dawn - used for light gray cats

Dove

Dusk - used for dark gray cats

Evening

Falcon - used for gray and white cats - derived from the peregrine falcon

Fog

Goose - used for gray and white cats

Granite - used for spotted tabbies

Gray

Gull - used for gray and white cats

Hail - used for light gray cats

Halcyon - used for dark gray or blue cats with a little white - derived from the belted kingfisher

Haze

Henbit - derived from the common henbit

Heron - derived from the great blue heron

Junco - derived from the dark-eyed junco

Larkspur - derived from the delphinium

Lichen - used for light gray tabbies

Lizard - used for tabbies

Lobelia - derived from the great blue lobelia

Loon - used for gray and white tabbies - derived from the common loon

Lynx - used for spotted tabbies - derived from the bobcat

Mallow - derived from the common mallow

Minnow - used for tabbies

Mint - refers to the flowers - derived from the hoary mountain mint

Mist

Mole - derived from the eastern mole

Moth - used for tabbies

Murk - used for dark gray cats

Nettle - derived from the American stinging nettle

Nuthatch - used for gray and white cat

Opossum - derived from the North American possum

Owl - used for large gray and white tabbies - derived from the barred owl

Pale - used for light gray cats

Pebble - used for small cats

Phacelia - derived from the purple phacelia

Phlox - derived from the woodland phlox

Pigeon

Pike - used for spotted tabbies

Raccoon - used for gray tabbies - derived from the common raccoon

Rain

Rock

Sage - derived from the wood sage

Shade - used for dark gray cats

Shale

Shell - used for tabbies

Shrew - derived from the northern short-tailed shrew

Shrike - used for gray and white cats - derived from the northern shrike

Silver

Slate

Sleet - spotted gray tabby

Smoke - used for tabbies

Soot - used for dark gray cats

Squirrel - used for gray and white cats - derived from the eastern gray squirrel

Steam - used for pale gray tabbies

Stone

Storm - used for dark gray cats

Sycamore - used for big light gray tabbies - derived from the American sycamore

Thalia - used for gray and white cats - derived from the powdery thalia

Thistle - derived from the common thistle

Titmouse - derived from the tufted titmouse

Trout - used for spotted tabbies

Vervain - derived from the blue vervain

Vetch - derived from the common vetch

Violet - derived from the birdsfoot violet

Wolf - derived from the gray wolf

Blue

Aster - derived from the flower

Blue

Bunting - derived from the indigo bunting

Chicory - derived from the common chicory

Gallinule - derived from the common gallinule

Glory - derived from the morning glory

Halcyon - used for dark gray or blue cats with a little white - derived from the belted kingfisher

Indigo - derived from the blue false indigo

Jay - used for blue and white tabbies - derived from the blue jay

Swallow - used for blue and white cats - derived from the tree swallow

Ginger/Red

Apple - refers to the fruit - derived from the wild apple

Ash - refers to the leaves - derived from white ash

Bergamot - refers to the flowers - derived from the plant

Blaze

Bramble - refers to the unripe fruit - derived from the blackberry bramble

Cardinal - refers to the male of the species

Dawn

Dusk

Ember - used for small cats

Evening - used for deep red cats

Fire

Fox - derived from the red fox

Ginger

Ginseng - derived from the American ginseng

Hawthorn - refers to the fruit - derived from the red hawthorn

Hazel - refers to flowers - derived from the Ozark witch hazel

Holly - refers to the fruit - derived from the meadow holly

Ivy - used for tabbies - derived from the poison ivy

Maple - refers to the leaves - derived from the red maple

Marigold - derived from the marigold

Morning

Lily - used for spotted tabbies - derived from the leopard lily

Oak - refers to the leaves - derived from the white oak

Persimmon - derived from the American persimmon

Plum - refers to the fruit - derived from the American plum

Pumpkin - refers to the fruit

Red

Spark

Sumac - refers to the leaves or berries - derived from the fragrant sumac (leaf) and the smooth sumac (berry)

Tanger - refers to the male of the species - derived from the summer tanger

Wasp - used for tabbies

Gold/Cream

Amber

Aphid - used for small cats

Apple - refers to the fruit - derived from the wild apple

Bee - used for tabbies

Blaze

Bolt

Daffodil - derived from the narcissus

Daisy - derived from the yellow ox-eyed daisy/black-eyed Susan

Dandelion - refers to the flower - derived from the weed

Dawn

Finch - derived from the goldfinch

Golden

Honey

Hornet - used for tabbies

Lightning

Locust - refers to the leaves - derived from the honey locust

Lotus - derived from the American lotus

Marigold - derived from the marigold

Morning

Mullein - refers to the flower - derived from the great mullein

Mustard - derived from the black mustard

Persimmon - derived from the American persimmon

Poppy - derived from the celandine poppy

Primrose - derived from the common evening primrose

Sand

Spark

Tanger - refers to the female of the species - derived from the summer tanger

Tansy - derived from the common tansy ragwort

Tawny

Velvet - derived from the velvet plant

Yellow

White

Aphid - used for small cats

Apple - refers to the flowers - derived from the wild apple

Avens - derived from the white avens

Bramble - refers to the flower - derived from the blackberry bramble

Blizzard

Bolt

Bright

Cherry - refers to the flowers - derived from the black cherry

Cloud

Clover - refers to the flowers - derived from the white clover

Cohosh - derived from the black cohosh

Cotton - refers to the seeds - derived from the upland cotton

Dandelion - refers to the seeds - derived from the weed

Egret - derived from the snowy egret

Flax - derived from the bastard toadflax

Frost

Gaura - derived from the gaura flowers

Hail

Haw - refers to the flowers - derived from the blackhaw

Hawthorn - refers to the flowers - derived from the red hawthorn

Hemlock - refers to the flowers - derived from the poison hemlock

Ice

Light

Lightning

Lotus - derived from American lotus

Milkweed - refers to the seeds - derived from common milkweed

Mint - refers to the flowers - derived from the hoary mountain mint

Mistletoe - refers to the berry - derived from the American mistletoe

Onion - refers to the bulb and flowers - derived from the wild onion

Orchid - derived from the Adam and Eve orchid

Pale

Parsley - refers to the flowers - derived from garden parsley

Plum - refers to the flowers - derived from the American plum

Rose - derived from the wild rose

Sage - derived from the wood sage

Sleet

Snow

Spark

Swan

White

Willow - refers to the catkins - used for white longhairs - derived from the black willow

Yarrow - derived from the common yarrow

Patched/Bicolor

Duck - used for black and brown cats

Eagle - used for brown and white cats - derived from the bald eagle

Falcon - used for gray and white cats - derived from the peregrine falcon

Grebe - used for brown and white cats - derived from Clark’s grebe

Harrier - used for brown and white cats - derived from the Northern harrier

Hawk - used for brown and white cats - derived from the red-tailed hawk

Iris - derived from the iris flower

Jaeger - used for black and white cats - derived from various jaegers

Jay - used for gray and white tabbies - derived from the blue jay

Nuthatch - used for gray and white cat

Merganser - used for black and white cats - derived from the common merganser

Patch - general bi/tricolor

Plover - used for black, gray, or brown and white cats - derived from the various species of plover

Scaup - used for black and white cats - derived from the greater and lesser scaup

Shrike - used for gray and white cats - derived from the northern shrike

Skunk - used for black and white cats - derived from the spotted skunk

Sparrow - used for brown and white tabbies - derived from the house sparrow

Swallow - used for blue and white cats - derived from the tree swallow

Thalia - used for gray bicolors - derived from the powdery thalia

Thrush - used for spotted brown and white tabbies - derived from the wood thrush

Weasel - used for brown and white cats - derived from the long-tailed weasel

Patterned

Speckle - used for spotted tabbies

Spotted - used for spotted tabbies

There’s others but writing them down would make this section bloated...

Tortoiseshell/Calico

Brindle - used for any tortie

Clay - used for brown torties

Copper - used for dark torties

Dapple - used for any tortie

Dawn - used for dilute torties

Dusk - used for dark torties

Eagle - used for darker torties - derived from the golden eagle

Ember - used for small torties

Evening - used for dark torties

Fox - used for diluted torties - derived from the gray fox

Fritillary - used for brown torties - derived from a tribe of butterfly

Grebe - used for dark torties - derived from the eared gribe

Kestrel - used for spotted red torties or blue torties - derived from the American kestrel

Morning - used for dark or dilute torties

Mottle - used for torties with little to no white

Oriole - used for darker torties - derived from the orchard oriole

Owl - used for brown torties - derived from the great horned owl

Pansy - used for any tortie - derived from the garden pansy

Patch - used for any calico

Pheasant - used for brown torties

Robin - used for brown torties - derived from the American robin

Skipper - used for brown torties - derived from the skipper butterfly

Squirrel - used for diluted torties - derived from the fox squirrel

Tawny - used for diluted brown torties

Toad - used for diluted torties

Towhee - used for darker torties with white - derived from the eastern towhee

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“There is a patience of the wild – dogged, tireless, persistent as life itself.”

― Jack London

I grew up on the northern edge of Appalachia and though my home town seemed quiet tidy and civilized I was later to learn when I went North to college that the places I had grown up - a town named after a novel by Sir Walter Scott and another larger place, a small city in the heart of Appalachia, that was the big city for the Hatfield and McCoy clan battles - were actually on the edge of the wild but not part of the wild. Our local vision looked to farms and libraries and automobiles and B-52 bombers flying at 45,000 feet leaving the white trails of their engines over head as a constant reminder of the twentieth century and its destructive civilizing power.

Growing up I did not know about Asperger's. It had been named but the name had not reached us and was the currency of psychiatrists which we new about but never saw. I did not know that my shyness, my sense of isolation and, looking back, my inability to be social was tied to that condition. All I knew was a loneliness that I fought through reading and long walks in the farm and woodland around those two towns, one a village and one a city in a rural part of America I did not know was known for its poverty. I did not feel poor and did not know I was as emotionally isolated as I was physically isolated.

In the mid 1960′s I was an active member of a boy scout troop. That was an effort by my family to engage me in some sort of social life. Unfortunately they did not understand that part of being a boy scout was an interest of the parents - an encouragement so to speak to achieve awards and merit badges. I readily did the learning and the skills for merit badges but never took the tests, being to shy or fearful and rebellious. I was much the failure as a Boy Scout even though I did manage to eek out a first class rank. No one warned my parents that scouting is social organization and required social skills that as a boy I did not have due to what I later learned was a combined impact of whatever psychiatric social dis-ease I had and their alcoholism which created a childhood PTSD. I memorized the Boy Scout handbook but simply added it to my lonely skill set as I wandered wood, stream, “holler” and field.

At some point in the mid nineteen sixties the scout troop was on a mission to plant trees in order to earn a forestry merit badge. We were actually doing a favor for the local agricultural extension agent on a property he own miles deep into the hills. So that day I learned the back breaking work of planting what would in time become a lofty pine wood lot which was the retirement fund for the agricultural agent. At least that is what I though at the time already well experience in youthful cynicism about the motives of other people, especially adults.

When we broke for lunch we were treated by an eight point buck white tail deer and a doe jumping the long abandoned fence rows. In the afternoon the troop was loosed upon the hills. Initially I tried to blend in but there was simply too much noise. When we found an old railroad line the troop went cackling and shouting off along it and I turned and went the other way aware that I could find my way back easily when the time came.

I arrived at a turning point in my life as a passed through a tunnel much like the one pictured. Once through the tunnel there was silence and a sense of the wild that all my ramblings around my towns had never given me. No car sounds, no voices or hum of people in the distance - just the smell of pine and hardwood and grasses on a hot day and a stillness that matched the stillness inside of me and on that day I stopped feeling lonely. Like Buck In Jack London’s Call of the Wild I felt the ancient primordial.

“Deep in the forest a call was sounding, and as often as he heard this call, mysteriously thrilling and luring, he felt compelled to turn his back upon the fire and the beaten earth around it, and to plunge into the forest, and on and on, he knew not where or why; nor did he wonder where or why, the call sounding imperiously, deep in the forest.” ― Jack London, The Call of the Wild

Later they sent out the troop as a search party. It was not much of a search in that the other boys knew I headed the direction opposite them and they found me sitting on the side of a pine covered hill simply listening and breathing, for the first time in my life feeling a real part of something. And needless to say when we got back to the tree farm I was thoroughly chewed and humiliated by the adults while the boys sniggered and, I supposed, feeling quiet superior in that they were seen as my rescuers. They already had me pegged as weird and an outsider anyway and equated outsider with incompetent.

But that was the day I no longer felt broken and out of place in the world, how I felt in society was another issue. That day however, I started gaining confidence that there was a place for me. How I ended up becoming a psychotherapist instead of a game warden working in the wild is a long story and much blame lies on my efforts and my therapists efforts to domesticate and socialize me. But that is another story.

When I saw the picture of the tunnel, so much like the one I passed through that day the story came flooding back.

I have come to believe that understanding the “healing” to PTSD and Asperger's ( which is no longer called Asperger's but has been medicalized into Autism - just as the writers of the DSM have de-medicalized aberrant and self destructive emotional conditions such as transvestitism) is a struggle between the need to integrate into a society that is in direct conflict with the basic needs of some who need to leave domestication behind and live in the clarity of the wild - a place where one can live without the cynicism that civilization requires to even exist.

There are some people, men and women, that the call of the wild, the clarity of silence, tooth and claw, of the shadow of danger and he heartbeat of the planet are required for peace of mind and soul. Domesticators will never understand this about their fellow humans. We really as a species are not that far from the foot of the glacier or the open game filled savannahs of our origins.

For some of us we are only truly alive in a place where we can feel the chill of death's shadow casting over us from that primordial silence, a place where the energy of life is not muddled by the cackling of boys, cars, B-52s and the million things human monkeys create to reassure themselves they are safe from that chill shadow.

“It was an old song, old as the breed itself - one of the first songs of the younger world in a day when songs were sad. It was invested with the woe of unnumbered generations, this plaint by which Buck was so strangely stirred. When he moaned and sobbed, it was with the pain of living that was of old the pain of his wild fathers, and the fear any mystery of the cold and dark that was to them fear and mystery. And that he should be stirred by it marked the completeness with which he harked back through the ages of fire and roof to the raw beginnings of life in the howling ages.”

― Jack London

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sunrise at Otter Cliff, Acadia National Park, Maine by sunj99 // Acadia National Park is an American national park located in the state of Maine, southwest of Bar Harbor. The park preserves about half of Mount Desert Island, many adjacent smaller islands, and part of the Schoodic Peninsula on the coast of Maine. Acadia was initially designated Sieur de Monts National Monument by proclamation of President Woodrow Wilson in 1916. Sieur de Monts was renamed and redesignated Lafayette National Park by Congress in 1919—the first national park in the United States east of the Mississippi River and the only one in the Northeastern United States. The park was renamed Acadia National Park in 1929. More than 3.5 million people visited the park in 2017. Native Americans of the Algonquian nations have inhabited the area called Acadia for at least 12,000 years. They traded furs for European goods when French, English, and Dutch ships began arriving in the early 17th century. The Wabanaki Confederacy has held an annual Native American Festival in Bar Harbor since 1989. Samuel de Champlain named the island Isle des Monts Deserts (Island of Barren Mountains) in 1604. The island was granted to Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac by Louis XIV of France in 1688, then ceded to England in 1713. Summer visitors, nicknamed rusticators, arrived in 1855, followed by wealthy families, nicknamed cottagers as their large houses were quaintly called cottages. Charles Eliot is credited with the idea for the park. George B. Dorr, the "Father of Acadia National Park," along with Eliot's father Charles W. Eliot, supported the idea through donations of land, and advocacy at the state and federal levels. John D. Rockefeller Jr. financed the construction of carriage roads from 1915 to 1940. A wildfire in 1947 burned much of the park and destroyed 237 houses, including 67 of the millionaires’ cottages. The park includes mountains, an ocean coastline, coniferous and deciduous woodlands, lakes, ponds, and wetlands encompassing a total of 49,075 acres (76.7 sq mi; 198.6 km2) as of 2017. Key sites on Mount Desert Island include Cadillac Mountain—the tallest mountain on the eastern coastline and one of the first places in the United States where one can watch the sunrise—a rocky coast featuring Thunder Hole where waves crash loudly into a crevasse around high tides, a sandy swimming beach called Sand Beach, and numerous lakes and ponds. Jordan Pond features the glacially rounded North and South Bubbles (rôche moutonnées) at its northern end, while Echo Lake has the only freshwater swimming beach in the park. Somes Sound is a five-mile (8 km) long fjard formed during a glacial period that reshaped the entire island to its present form, including the U-shaped valleys containing the many ponds and lakes. The Bass Harbor Head Light is situated above a steep, rocky headland on the southwest coast—the only lighthouse on the island. The park protects the habitats of 37 mammalian species including black bears, moose and white-tailed deer, seven reptilian species including milk snakes and snapping turtles, eleven amphibian species including wood frogs and spotted salamanders, 33 fish species including rainbow smelt and brook trout, and as many as 331 birds including various species of raptors, songbirds and waterfowl. In 1991, peregrine falcons had a successful nesting in Acadia for the first time since 1956. Falcon chicks are often banded to study migration, habitat use, and longevity. Some trails may be closed in spring and early summer to avoid disturbance to falcon nesting areas. Recreational activities from spring through autumn include car and bus touring along the park's paved loop road; hiking, bicycling, and horseback riding on carriage roads (motor vehicles are prohibited); rock climbing; kayaking and canoeing on lakes and ponds; swimming at Sand Beach and Echo Lake; sea kayaking and guided boat tours on the ocean; and various ranger-led programs. Winter activities include cross-country skiing, snowshoeing, snowmobiling, and ice fishing. Two campgrounds are located on Mount Desert Island, another campground is on the Schoodic Peninsula, and five lean-to sites are on Isle au Haut. The main visitor center is at Hulls Cove, northwest of Bar Harbor

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Title: Sunset Twilight at Acadia National Park, Maine

Artist: sunj99 ( http://bit.ly/2PkNwCz )

Uploaded Date: April 20, 2019 at 07:55AM

Description:

Acadia National Park is an American national park located in the state of Maine, southwest of Bar Harbor. The park preserves about half of Mount Desert Island, many adjacent smaller islands, and part of the Schoodic Peninsula on the coast of Maine. Acadia was initially designated Sieur de Monts National Monument by proclamation of President Woodrow Wilson in 1916. Sieur de Monts was renamed and redesignated Lafayette National Park by Congress in 1919—the first national park in the United States east of the Mississippi River and the only one in the Northeastern United States. The park was renamed Acadia National Park in 1929. More than 3.5 million people visited the park in 2017. Native Americans of the Algonquian nations have inhabited the area called Acadia for at least 12,000 years. They traded furs for European goods when French, English, and Dutch ships began arriving in the early 17th century. The Wabanaki Confederacy has held an annual Native American Festival in Bar Harbor since 1989. Samuel de Champlain named the island Isle des Monts Deserts (Island of Barren Mountains) in 1604. The island was granted to Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac by Louis XIV of France in 1688, then ceded to England in 1713. Summer visitors, nicknamed rusticators, arrived in 1855, followed by wealthy families, nicknamed cottagers as their large houses were quaintly called cottages. Charles Eliot is credited with the idea for the park. George B. Dorr, the "Father of Acadia National Park," along with Eliot's father Charles W. Eliot, supported the idea through donations of land, and advocacy at the state and federal levels. John D. Rockefeller Jr. financed the construction of carriage roads from 1915 to 1940. A wildfire in 1947 burned much of the park and destroyed 237 houses, including 67 of the millionaires’ cottages. The park includes mountains, an ocean coastline, coniferous and deciduous woodlands, lakes, ponds, and wetlands encompassing a total of 49,075 acres (76.7 sq mi; 198.6 km2) as of 2017. Key sites on Mount Desert Island include Cadillac Mountain—the tallest mountain on the eastern coastline and one of the first places in the United States where one can watch the sunrise—a rocky coast featuring Thunder Hole where waves crash loudly into a crevasse around high tides, a sandy swimming beach called Sand Beach, and numerous lakes and ponds. Jordan Pond features the glacially rounded North and South Bubbles (rôche moutonnées) at its northern end, while Echo Lake has the only freshwater swimming beach in the park. Somes Sound is a five-mile (8 km) long fjard formed during a glacial period that reshaped the entire island to its present form, including the U-shaped valleys containing the many ponds and lakes. The Bass Harbor Head Light is situated above a steep, rocky headland on the southwest coast—the only lighthouse on the island. The park protects the habitats of 37 mammalian species including black bears, moose and white-tailed deer, seven reptilian species including milk snakes and snapping turtles, eleven amphibian species including wood frogs and spotted salamanders, 33 fish species including rainbow smelt and brook trout, and as many as 331 birds including various species of raptors, songbirds and waterfowl. In 1991, peregrine falcons had a successful nesting in Acadia for the first time since 1956. Falcon chicks are often banded to study migration, habitat use, and longevity. Some trails may be closed in spring and early summer to avoid disturbance to falcon nesting areas. Recreational activities from spring through autumn include car and bus touring along the park's paved loop road; hiking, bicycling, and horseback riding on carriage roads (motor vehicles are prohibited); rock climbing; kayaking and canoeing on lakes and ponds; swimming at Sand Beach and Echo Lake; sea kayaking and guided boat tours on the ocean; and various ranger-led programs. Winter activities include cross-country skiing, snowshoeing, snowmobiling, and ice fishing. Two campgrounds are located on Mount Desert Island, another campground is on the Schoodic Peninsula, and five lean-to sites are on Isle au Haut. The main visitor center is at Hulls Cove, northwest of Bar Harbor

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wellston Wildlife Area

36098 Co. Hwy. 15A

Hamden, OH 45634

Wellston Wildlife Area is a 1446-acre state wildlife area located 1 mile north of Hamden. The property is in Clinton and Richland townships, Vinton County, approximately one mile north of Hamden. Lake Rupert lies along State Route 683 one-half mile north of the intersection with State Route 93.The topography includes gently rolling, reverting old fields, and woodland. The 973 acres of uplands surrounding the lake provide a variety of habitats for wildlife. Forty-five percent of the land is covered by woodland, 25 percent by brush land, and 30 percent by open land. The lake encompasses 325 acres, 25 percent of the total area. At conservation pool the lake is about two miles long with a maximum depth of 28 feet. Shoreline cover includes rooted aquatic vegetation, overhanging brush, felled shoreline trees, and submerged brush piles.

Acquisition of the Wellston Wildlife Area began in 1918. The property was acquired using multiple state funds. Lake Rupert was built in 1969 as a cooperative effort of the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) and the city of Wellston to provide a water supply for the city and general public recreation. In 1979 the ODNR, Division of Wildlife, received ownership of the area from the city. Management work has included selective cutting and mowing of brush lands, maintenance of existing open fields, planting of shrubs, and the addition of squirrel nest boxes. In the lake many submerged fish attractors, consisting of brush piles and felled shoreline trees, have been added as fish habitat.

Lake Rupert has been stocked with and yields good catches of Northern pike, walleyes, largemouth bass, bullheads, bluegills, and channel catfish. The major game species are cottontail rabbit, ruffed grouse, fox and gray squirrels, white-tailed deer, and woodchuck. Woodcock and waterfowl appear mainly as migrant visitors, but some resident wood ducks can be found. Beaver are well established on the lake and all other furbearers common to the region occur on the area. A variety of songbirds, small mammals, reptiles, and amphibians also live on the area in association with the diverse mixture of habitat types.

0 notes

Text

How Well Do You Know British Wildlife?

Surprisingly, three out of 10 Britons do not know there is wildlife in Britain. But the larger British Isles are teeming with wildlife including land mammals, birdlife, and marine life. There is also a wonderful variety of small animals and insects including the lovable bumblebee. The good thing is that you can travel to any of the popular wildlife viewing sites in a short time seeing as it is that the UK is not a large country. The diverse landscape is a bonus attraction for the avid tourist. There are marshes, moor, cliffs and beaches to explore while looking for wildlife. All of it here in the UK.

What is some popular wildlife to see in the UK?

• Scottish wildcat

This feline is to be found in Northern England, Wales and Scotland. It is almost indistinguishable from the domestic cat and can crossbreed with it. The numbers are declining because of this diminishing breeding line.

• Pine Marten

This is a kin to weasel, and native to the Lake District. It is a nocturnal hunter and prefers to sleep in underground burrows.

• Red squirrels

This squirrel has ginger fur and taller years than the grey squirrel. The ginger fur changes to a grey shade in winter. These cute furry animals are declining in numbers as they are decimated by squirrel pox from their larger and more numerous kin, the grey squirrel. They number less than 200,000 of them.

• Skomer vole

This rodent is only found on Skomer Island in Wales. It is popular prey for the numerous predator birds on the island.

• Hedgehogs

These rodents are also on the decline due to habitat destruction and changing climates. They numbered over 30 million 50 years ago but now number about a million.

• Turtledoves

These beautiful birds have become very rare to see in the UK have declined in numbers by over 90%. The best time to see them is in the summer.

• Natterjack Toad

It has become very rare to hear this noisy amphibian, remaining only in small numbers in Norfolk and Lincolnshire.

• Slow Worm

This is a legless lizard that closely resembles a snake. It can be found in all parts of the UK.

• Bumblebees

These hairy black and yellow striped bees can be found hovering over flowering plants all over the UK. Unlike the aggressive honey bees, bumblebees make are generally harmless and their gentle buzzing will be heard in many fields, gardens and parks.

Bees in general are a particular passion of mine. I recently became a beekeeper and regularly purchase products from The Humble Bumble as they donate to various bee charities and organizations. I just received a new bee charm from them for my sister which i’m over the moon with!

What are the best places to see wildlife in the UK?

Cairngorms National Park, Scotland

The Cairngorms National Park in the Scottish Highlands is a land of rare beauty with a variety of wildlife and stunning landscapes. The varied landscape consists of forests, moorlands, mountain, and grass fields. The wildlife to be found here includes pine martens, red squirrels, Scottish wildcats, and golden eagles. There is also a variety of small mammals, rodents and innumerable insects including wasps, ants and bumblebees. Tourists can walk this place on foot in guided tours.

Blakeney Point, Norfolk

This is area is world famous for its attraction as a site to see marine bird life. It is a breeding ground for grey seals with over 2,000 grey seal pups coming to life each year from October to January. This area is part of Blakeney National Nature Reserve. An organized boat trip is the only way to get here during the breeding season.

The Isle of Mull, Scotland

The white-tailed eagle has been re-introduced in the UK on this isle. This is the biggest bird of prey native to the UK. It can be spotted swooping down on fish in the sea or soaring over the forests in search of small prey. Buzzards and golden eagles can also be sighted here. Marine attractions include porpoises and dolphins.

Falmouth, Cornwall

Pendennis point is on this location. This is one of the best spots in the UK to view marine wildlife, with breathtaking sea views as the background. There are also good views of Falmouth Bay and River Mal. It is a good spot for viewing bottlenose and common dolphins. Other marine attractions include shallow swimming sharks, grey seals and a variety of marine birds.

New Forest, Hampshire

This ancient woodland and heath is home to a herd of over 3,000 wild ponies that roam this area. Tourists can also spot all the deer species that are native to the UK. Other attractions include birds and snakes as well as insects including butterflies, dragonflies and bumblebees.

Kielder Forest, Northumberland

This is the home of the photogenic red squirrel whose numbers have dwindled dramatically. This forest is also home to bats, badgers, pipistrelle bats and other small mammals. Tourists can also see an osprey swooping down on these small prey from time to time.

Causeway Coast, Northern Ireland

This rugged coast landscape is a challenge to navigate but offers plenty to see in terms of wildlife. The cliffs are home to agile mountain hares and birds including peregrine falcons, and puffins. There are sharks, Atlantic grey seals and porpoises to be found in the sea. Bird watchers will find an interesting variety of marine birds including razorbills, auks and guillemot heading off to fish in the sea, homing in and heading to breeding grounds.

Shetland and Orkney Islands

These isles in the northernmost point of the UK offer plenty for the tourist if you can get there. The waters off the coast hold killer whales, minke whales, humpback whales, white-sided and white-beaked dolphins. There are also sea otters and a variety of marine birds. Bird watchers will especially find Skara Brae, Noss and Sumburgh areas rich with different bird species. These isles are also interesting archaeological sites.

Gilfach Nature Reserve, Wales

This is a great spot to see otters on the hunt for salmon. They come here every year from October to December to catch easy salmon prey at the waterfalls as the salmon swim upstream. These elusive water predators can also be spotted at other times of the year although it is a bit harder to do so. Early morning and sunset hours are the best for viewing.

Skomer Island

The hugely popular Atlantic Puffin is to be found in good numbers on this island off the coast of Pembrokeshire in western Wales. This is a popular destination with birders who come here for the rich bird life and photo opportunities. Seeing about 70,000 Manx Shearwaters make a landing in the dusk is a phenomenon that is one of the rarest in the world. There are also the photogenic Atlantic puffins who are happy enough to pose for photos as they are well-used to human presence.

Dorset

This is one of the most beautiful inhabited places in the UK. The meadows of Kingcombe are perfectly kept and preserved, with over 200 years of well-maintained fields, hay meadows and hedgerows. All of it is done naturally without pesticides which makes it highly attractive to insects and other small wildlife.

There is plenty to see if you take the time to stroll leisurely through the meadows. There are buzzing bumblebees, numerous scurrying insects and different birds that make a living of these small prey. The soothing landscape holds plenty to see and photograph.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

10 of my favourites nature reserves across the south of England…A post for English Tourism week

So at the weekend I had a funny little idea to do a post just saying some of my favourites places to watch nature and writing a bit about them just as something extra to post but I thought I probably already indicate to you a lot about the places when I go so didn’t do it. However yesterday I saw it was English Tourism Week and I used the hashtag on my Twitter Dans_Pictures with my pictures from a day off yesterday and it made me have the idea to do the post again as whilst in these explanations it will mostly talk about wildlife and landscapes and things from the perspective of my hobby it still celebrates different places I go to and enjoy my hobby which make me proud to be English in a year when I loved going to Scotland for the first time a wonderful wildlife and landscape country so I feel it’s what this week is all about. I will do two posts, this with 10 of my favourite nature reserves in the south of England and one this time tomorrow about 10 of my favourite places in my beloved New Forest national park. Therefore please be advised that perhaps my two favourite nature reserves Blashford Lakes and Lymington-Keyhaven feature in tomorrow’s post as they’re in the New Forest, this just helped vary that post and make room for others in this post. I would also just like to say these two posts only scratch the surface of the amazing nature reserves and New Forest walks that I know in this area and the lists aim to give something of everything with varied locations included so there are many of my favourites places to watch nature and see landscapes in this area that are not included. So below are bits of information of why I like these 10 nature reserves. This is in no particular order, the first five are in Hampshire and the others other counties, other than that just the order I thought of the places in and as always attached to this post is one of my pictures from each place which I indicate in the text for each. The explanations are designed to be pretty brief also!

Farlington Marshes

Farlington Marshes near Portsmouth shown in the 1st picture in this photoset which I took in January 2017 is a fantastic coastal nature reserve, famous for the amount of one of my favourite birds the Brent Goose that come there in the winter and things like Pintail, Bearded Tit, Short-eared Owl, Avocet and many more ducks and wading birds it’s one of the nature reserves I’ve known longest.

Hayling Island Oysterbeds

Near to Farlington the Hayling Island oysterbeds area where I took the picture of another of my favourite birds the Little Egret flying in 2015 the 2nd picture in this photoset is another area good for coastal birds, star species include Greenshank, again Brent Geese, Grey Plover and it’s a great place to see rarer birds out to sea such as Black-necked and Slavonian Grebe, Long-tailed Duck, Great Northern Diver and Velvet Scoter.

Titchfield Haven

Titchfield Haven shown in the 3rd picture in this photoset from this year was the first nature reserve I ever visited so it so important to me, it’s a lovely hide based nature reserve with things like Snipe, Lapwing, Avocet, Shelduck, Black-tailed Godwit and Oystercatcher key species, as well as Sanderling on the Hill Head sea front outside the reserve area. Many a rare bird has cropped up in this amazing reserve over the years too.

Martin Down

Martin Down on the Hampshire/Dorset/Wiltshire border is a place we discovered mostly to see butterflies in the spring and summer but is a beautiful farmland area and has some great birds too and has become synonymous of spring and summer for me. Key species include one of my favourite butterflies the Adonis Blue as photographed in the 4th picture in this photoset in 2015, Marsh Fritillary, Green Hairstreak, Yellowhammer, Skylark, Corn Bunting and Grey Partridge.

Bentley Wood

Bentley Wood is perhaps mostly a butterfly nature reserve for us with its sun kissed pathways hosting many of the woodland species, it really is a butterfly paradise for me as I’ve said before. Butterflies its good for include one of my favourites the Silver-washed Fritillary as I photographed in 2014 in the 5th picture in this photoset, Small and the normal Pearl-bordered Fritillary, White Admiral, Purple Hairstreak and of course the famous Purple Emperor which I am yet to see.

Radipole Lake

Radipole Lake in Dorset’s Weymouth for me is a world class urban location to watch wildlife hosting many great birds such as Cetti’s Warbler, one of my favourite birds the Sedge Warbler, Marsh Harrier and of course the famous Hooded Merganser which nobody knows how it got there and caused a lot of attention when it arrived. As much as that it’s just a top place to photograph birds and it’s beautiful too as shown in my picture last year of a sunlit reedbed the 6th in this photoset.

Portland Bill

Nearby Portland is also a fantastic location for many purposes, I love the coast and I grew up visiting Weymouth and Portland on our family holidays, the landscape in the 7th picture in this photoset that I took last August sums up how beautiful I think it is. I love watching four of my favourite birds the Guillemot, Razorbill, Fulmar and Gannet there as well as Little Owl and Shag.

Brownsea Island

Brownsea Island in Dorset is a brilliant tourist destination for many purposes also and I love going, its particularly famous for being a Red Squirrel refuge I got the picture of one running there in September 2013 the 8th in this photoset, Little Egrets this favourite bird of mine bred for the first time ever at Brownsea and the Spoonbills.

Durlston Country Park

Nearby Durlston is a place I see as an unsung part of the Dorest coast, its beautiful as shown in the 9th picture in this photoset which I took two years ago and hosts great flowers like Early Spider Orchid and wildlife such as Sika Deer, again seabirds Fulmar, Guillemot, Razorbill, Gannet and Shag and is a good place to see Peregrine Falcons.

Arundel WWT

This is a great reserve in West Sussex where I have enjoyed many amazing moments like photographing one of my favourite birds the Pochard in 2011 the 10th picture in this photoset. The collection birds are fantastic to photograph and the wild part of the reserve hosts Kingfisher, Water Vole, Little Grebe among other species well.

#english tourism week#new forest#south#hampshire#england#uk#wiltshire#dorset#sussex#tourism#wildlife#photography#world#beautiful

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup “is now recognized as one of the largest direct action conservation programs in Canada. ”

“Litter can have negative impacts on wildlife and ecosystems, including ingestion or entanglement, environmental toxicity due to harmful chemicals in plastics. “

The George Genereux Urban Regional Park clean up is happening Saturday September 19 when the City of Saskatoon will kindly arrange to drop off a large Loraas disposal bin at the site where it will be handy from 9:00am to 5:00pm

Clean Up Volunteers at the Richard St. Barbe Baker Afforestaton Area, Saskatoon, SK 2016 Community Clean Up

White-Tailed Deer Fawn

Robert White, 2016 Clean UP Photographer, Personal Friend of Richard St. Barbe Baker, Baha’i representative, SOS Elms, Richard St. Barbe Baker Afforestation Area, south west sector, in the City of Saskatoon, SK, CA at the Volunteer Community Clean UP 2016

George Genereux Urban Regional Park is located in the West Swale, the current name of the Pleistocene era Yorath Island Glacial Spillway. The Yorath Island Glacial Spillway or West Swale was once a river connecting the Glacial North Saskatchewan river valley and Glacial Rice Lake with -at the time- South Saskatchewan Glacial Lake. This span of land is still conducting water through above ground wetlands, and underground water springs and channels between the North Saskatchewan River and the South Saskatchewan River. Keeping this area without pollutants and litter, also keeps the City of Saskatoon water clean and fresh. Cleaning the forest also restores this naturalize site started as a tree nursery in 1972, and it is now an urban regional park, and an amazing nature viewing site.

If anyone has the wherewithal to conduct a cleanup by themselves, that is also wonderful! The Meewasin cleanup has bins around the city and people can go out to George Genereux Urban Regional Park anytime between now and September 31! The Friends of the Saskatoon Afforestation Area and Meewasin can accommodate this wonderful individual endeavour and supply bags to you! How? [email protected] or 306.380.5368

On Saturday, September 19, George Genereux Urban Regional Park is about 1/2 mile square -147.8 acres- in size, so it should be easy to social distance. We will take COVID-19 precautions, to do everything we can during phase 4 of the province’s opening to keep all volunteers safe. We are even rustling up ways to give out volunteers free facemasks on Sat. Sept. 19 in case volunteers come closer than 6 feet! ����

On Saturday Sept 19 there will be prizes to win! Free facemasks, free refreshments, free plastic gloves & free trash bags for our clean up volunteers. Please let us know your intention to come out so we have enough supplies! [email protected] or 306.380.5368 Thanks!

We look forward to your help and assistance to restore this afforestation area to its naturalized wildlife habitat and enjoy this urban regional park!

Volunteers who helped with the Richard St. Barbe Baker Afforestation Area cleanup said that it was very rewarding seeing the difference to the semi-wilderness wildlife habitat, and they would do it again!

Please share the George Genereux Urban Regional Park pamphlet with your friends and family! Thanks!

For directions as to how to drive to “George Genereux” Urban Regional Park

For directions on how to drive to Richard St. Barbe Baker Afforestation Area

For more information:

Blairmore Sector Plan Report; planning for the Richard St. Barbe Baker Afforestation Area, George Genereux Urban Regional Park and West Swale and areas around them inside of Saskatoon city limits

P4G Saskatoon North Partnership for Growth The P4G consists of the Cities of Saskatoon, Warman, and Martensville, the Town of Osler and the Rural Municipality of Corman Park; planning for areas around the afforestation area and West Swale outside of Saskatoon city limits

Richard St. Barbe Baker Afforestation Area is located in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada north of Cedar Villa Road, within city limits, in the furthest south west area of the city. 52° 06′ 106° 45′

Addresses:

Part SE 23-36-6 – Afforestation Area – 241 Township Road 362-A

Part SE 23-36-6 – SW Off-Leash Recreation Area (Richard St. Barbe Baker Afforestation Area ) – 355 Township Road 362-A

S ½ 22-36-6 Richard St. Barbe Baker Afforestation Area (West of SW OLRA) – 467 Township Road 362-A

NE 21-36-6 “George Genereux” Afforestation Area – 133 Range Road 3063

Wikimapia Map: type in Richard St. Barbe Baker Afforestation Area

Google Maps South West Off Leash area location pin at parking lot

Web page: https://stbarbebaker.wordpress.com

Where is the Richard St. Barbe Baker Afforestation Area? with map

Where is the George Genereux Urban Regional Park (Afforestation Area)? with map

Pinterest richardstbarbeb

Facebook Group Page: Users of the George Genereux Urban Regional Park

Facebook: StBarbeBaker

Facebook group page : Users of the St Barbe Baker Afforestation Area

Facebook: South West OLRA

Twitter: StBarbeBaker

Please help protect / enhance your afforestation areas, please contact the Friends of the Saskatoon Afforestation Areas Inc. (e-mail / e-transfers )

Support the afforestation areas with your donation or membership ($20.00/year). Please donate by paypal using the e-mail friendsafforestation AT gmail.com, or by using e-transfers Please and thank you! Your donation and membership is greatly appreciated. Members e-mail your contact information to be kept up to date!

Canada Helps

1./ Learn.

2./ Experience

3./ Do Something: ***

What was Richard St. Barbe Baker’s mission, that he imparted to the Watu Wa Miti, the very first forest scouts or forest guides? To protect the native forest, plant ten native trees each year, and take care of trees everywhere.

“We stand in awe and wonder at the beauty of a single tree. Tall and graceful it stands, yet robust and sinewy with spreading arms decked with foliage that changes through the seasons, hour by hour, moment by moment as shadows pass or sunshine dapples the leaves. How much more deeply are we moved as we begin to appreciate the combined operations of the assembly of trees we call a forest.”~Richard St. Barbe Baker

“St. Barbe’s unique capacity to pass on his enthusiasm to others. . . Many foresters all over the world found their vocations as a result of hearing ‘The Man of the Trees’ speak. I certainly did, but his impact has been much wider than that. Through his global lecture tours, St. Barbe has made millions of people aware of the importance of trees and forests to our planet.” Allan Grainger

“The science of forestry arose from the recognition of a universal need. It embodies the spirit of service to mankind in attempting to provide a means of supplying forever a necessity of life and, in addition, ministering to man’s aesthetic tastes and recreational interests. Besides, the spiritual side of human nature needs the refreshing inspiration which comes from trees and woodlands. If a nation saves its trees, the trees will save the nation. And nations as well as tribes may be brought together in this great movement, based on the ideal of beautifying the world by the cultivation of one of God’s loveliest creatures – the tree.” ~ Richard St. Barbe Baker.

Advertisements

Occasionally, some of your visitors may see an advertisement here,

as well as a Privacy & Cookies banner at the bottom of the page.

You can hide ads completely by upgrading to one of our paid plans.

Upgrade now Dismiss message

Share this:

Click to Press This! (Opens in new window)

Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

More

Customize buttons

Related

Traditional Naming Ceremony

In “B.T. Chappell”

Cree Word Search

In “flora”

Old Bone Trail

In “Goose Lake Trail”

Author: stbarbebaker

This website is about the Richard St. Barbe Baker Afforestation Area – an urban regional park of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada. The hosts are the stewards of the afforestation area. The afforestation area received its name in honour of the great humanitarian, Richard St. Barbe Baker. Richard St. Barbe Baker (9 October 1889 – 9 June 1982) was an English forester, environmental activist and author, who contributed greatly to worldwide reforestation efforts. As a leader, he founded an organization, Men of the Trees, still active today, whose many chapters carry out reforestation internationally. {Wikipedia} Email is StBarbeBaker AT yahoo.com to reach the Stewards of the Richard St. Barbe Baker Afforestation Area View all posts by stbarbebaker

Author stbarbebakerPosted on June 17, 2020Categories First Nation, Indigenous, June, June 21, Metis, National Indigenous Peoples Day, old bone trail, Richard St. Barbe Baker AFforestation ARea, UncategorizedTags Canadian National Railway, Canadian Northern Railway, CNoR, CNR, First Nation, GLLS, June 21, Metis, Midtown Plaza, National Indigenous Peoples Day, old bone trail, Qu’appelle Long Lake and Saskatchewan Railway, treaty 6 Edit “National Indigenous Peoples Day”

Leave a Reply

Post navigation

Previous Previous post: Traditional Naming Ceremony

Next Next post: Afforestation Areas Safety

Recent Posts

iNaturalist August 15, 2020

Tree Check Month July 31, 2020

Algae Blooms July 31, 2020

Bottle Drive in the Newspaper July 21, 2020

COVID Moth-er Event! July 21, 2020

Location

On Cedar Villar Road west of the City of Saskatoon Civic Operations Centre (Bus Barns) Richard St. Barbe Baker Afforestation Area is north of the land for Chappell Marsh Conservation Area. Wikimapia Map with afforestation area location: Google Maps with Off Leash area location pin at parking lot: Parking is at the South West Off Leash Dog Park Parking Lot (dog park is within the afforestation area). Best access is by vehicle. Coordinates 52° 06′ 106° 45′ Customizer.

Search for:

You are following Stewards of the Richard St. Barbe Baker Afforestation Area

You are following this blog, along with 367 other amazing people (manage).

Top Posts & Pages

The Saskatchewan Woodpecker

150 Happy Birthday, Canada!

What a little snow will do

Not the smallest piece of chaos

Paragon of the Beholder

A Pollinator Garden Abstract

Trembling Aspen

A Problem and Great Dilemna

Creating the Course

A Fog so Thick

Categories

Categories

Recent Posts

iNaturalist

Tree Check Month

Algae Blooms

Bottle Drive in the Newspaper

COVID Moth-er Event!

Interpretation in the forests

Survival

Safety in the Forest

Canadian Multiculturalism Day

Cree Word Search

Great Canadian Shorline Cleanup The Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup "is now recognized as one of the largest direct action conservation programs in Canada.

#clean#Clean up#Community Clean Up#Free facemasks#Free plastic gloves#Free prizes#Free refreshements#Free trash bags#Friends of the Saskatoon Afforestation Areas Inc clean up#George Genereux Urban Regional Park Clean up#Great Canadian Shoreline Clean up#Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup#Litterati app#Meewasin Clean UP#Saturday September 19#September 19

0 notes

Photo

Honey Locust; Thorny Locust (Gleditsia triacanthos)

Mature Size - (60-80′ x 60-80′) Occasionally can grow over 120′ tall.

Shape and Form - A medium to large tree with a rounded, spreading crown.

Growth Habit - Fast growth rate.

Leaves - Bipinnately compound leaves typically have many small leaflets. Leaves are 6" to 8" long, bright green and glossy. Late to leaf out in spring. Autumn foliage is a showy, clear yellow.

Flowers - Inconspicuous, greenish yellow to greenish white flowers appear in racemes in late spring (May-June in St. Louis).

Fruit/Seeds - Flowers are followed by long, twisted and flattened, dark purplish-brown seedpods (to 18” long) which mature in late summer and persist well into winter. Seedpods contain, in addition to seeds, a sweet gummy substance that gives honey locust its common name.

Bark - Trunk and branches have stout thorns (to 3” long) that are solitary or three-branched. Dark gray-brown colored bark develops elongated, smooth, plate-like patches separated by furrows. Very attractive and distinct.

Region - USA native. Native from Pennsylvania to Iowa south to Georgia and Texas. Naturalized in other areas within its hardiness range, such as New England.

Hardiness Zones - (3-8)

Habitat/Growing Conditions - Honey Locust is adapted to a variety of soils and climates. It is common in both bottomlands and uplands, in the open or in open woods. Honeylocust occurs on well-drained sites, upland woodlands and borders, old fields, fencerows, river floodplains, hammocks, rich, moist bottomlands, and rocky hillsides. It is most commonly found on moist, fertile soils near streams and lakes. Best grown in organically rich, moist, well-drained soils in full sun. Tolerant of a wide range of soils. Also tolerant of wind, high summer heat, drought and saline conditions. Highly tolerant of flooding. Very adaptable.

Plant Community - Spontaneous Urban Growth

Eco-indicator - NA

Other info - See Moraine Honey Locust (Gleditsia triacanthos ‘Moraine’)

The ability of Gleditsia to fix nitrogen is disputed.

Gleditsia triacanthos has been introduced worldwide, and has naturalized in some places to the point of being a harmful invasive. It should also be noted that over-planting of this plant in some urban areas has lead to increases in local pest populations, thus increasing the plants’ susceptibility to pests and disease.

Relatively short-live plant, averages around 100-150 years.

Honey Locust has successfully been used as a wind buffer.

Honey Locust wood is dense, hard, coarse-grained, strong, stiff, shock-resistant, takes a high polish, and is durable in contact with soil. The wood is used locally for posts, pallets, crates, general construction, furniture, interior finish, turnery, and firewood. It is useful, but is too scarce to be of economic importance.