#noah berlatsky

Text

The casual cruelty with which Columbia administrators rushed to do the bidding of their reactionary masters in Congress provides a quick lesson in who actually is the elite, and who is not. The students at the fancy college, it turns out, do not in fact run the fancy college. The university doesn’t treat them as bosses, and barely even as stakeholders. Instead, it treats them as subjects to be disciplined—and in disciplining them, it has a wide range of tools. Students are a kind of indentured employee; they are dependent on the university for housing, for health insurance, for the next steps in their career and life plans. If the university decides they are not sufficiently docile, it is trivially easy for the university to destroy their lives.

Everyone pretty much knows that young people have few resources and few levers of influence. We’re all aware that even supposedly rich kids don’t actually have control of their parent’s bank accounts and can be cut loose with nothing on a whim. We all know that young people have few connections and little influence compared to Congresspeople, administrators, and angry donors. And it is because people know that college students have little power that they become enraged when college students attempt to organize or demand some say in institutional or (god forbid) national policies.

Young people are “elites” not because they actually have power, but because the spectacle of them asserting autonomy in any way is at odds with the way things are supposed to be. They are pretentious for the same reason that women or LGBT people or Black people are considered pretentious elites when they contradict their supposed betters. When the right people have power; that’s natural; when the wrong people, marginalized people, have power—that’s an unbearable imposition.

It's easy to make light of college student activism, and to insinuate that people attending a swanky university can’t really have anything to protest about. But young people engage in activism for the same reason other marginalized people engage in activism; they have firsthand experience of inequality and injustice, and because they are treated unequally, they don’t have a lot of other ways to demand accountability or change. The vitriol directed at young people is not because young people are powerful; it’s because they aren’t, and so their assertions of autonomy are seen as a threat to established hierarchies.

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

Now 30 years after "Schindler's List" came out, I give you the worst article ever written about it.

Join me for a wallow in the depths of Extremely Online lefty pseudointellectualism and Awareness Raising.

"For all its pathos and earnestness, the movie is too glib in its handling of the Nazis. The concentration camp commandant, Amon Goeth (Ralph Fiennes), is a sadistic monster who performs cinematic and dramatic acts of brutality to signal to the viewer that he is pure evil."

Yes, the movie sure was unfair to Amon Goeth. It's not like there was historical evidence of him doing exactly what they showed.

"In real life, when Nazis and their ilk are trying to gain power, they often lie about their motives or their goals, and use dog whistles to rally support. They talk incessantly about black crime rates, or, in the Nazis’ case, about Jewish crime rates, in order to create a consensus for strong-arm law-and-order policies."

The Nazis were just a warm-up act for the REAL threat: Republicans!

And, just like with Goeth, I guess this movie doesn't actually show what Nazis were like in real life. I guess when Adolf Hitler promised in 1922 that he would exterminate all the Jews, that wasn't real life, that was a wandering variant from "Across the Hitlerverse." And speaking of superhero movies:

"But you don’t need to deconstruct Nazi ideology or understand racist dog whistles to condemn the Nazis in “Schindler’s List.” You just need to watch as Goeth takes up a sniper position and shoots anyone in the camp who happens to pause for a rest. It’s no harder than rooting against Lex Luthor or the Joker."

This drivel was published 5 years ago, so the author had to have been like 17 at the time and is just barely out of college now, right? Right??? (*checks*) NO WAY, HE'S 52, ARE YOU FOR REAL??!

"The Jewish people in the film don’t try to resist or kill their German oppressors. They don’t even express much in the way of hatred or resentment... Jewish people are always object lessons, never conscious teachers. No Jewish character criticizes or explains the evils of Nazi propaganda. These Jews never talk about how they experience prejudice, or what they would need to fight it.... the Jews around Schindler only beg him to save their relatives, or praise him for his bravery. They never insist on their rights."

Well, there was that Jewish architect in the camps who talked back to Goeth for a second about how the barracks would collapse and he immediately had her killed. The movie is about people having been ALREADY ghettoized by a for-real genocidal regime once the genocide program is under way. Where was there supposed to be a dramatic lecture? And what Jew would have given one, to which Nazi, in which fucking ACTUAL GHETTO?

Again and again, this screen-addled, zero-life-experience baby WHO IS SOMEHOW 52 YEARS OLD WTF fails to confront the horrors of true Jewish history because his only frame of reference has been Twitter arguments about how sleeping with a mattress is secretly white supremacy.

"The targets of fascism are the people best able to express what is happening to them, and what they need to fight it. But “Schindler’s List” presents victims as supplicants. It doesn’t model any way to show support for journalist Jemele Hill, who fell out with her network for saying that Trump is a white supremacist. It doesn’t push you to show solidarity when anti-racist activists demand that Confederate monuments be taken down. It doesn’t tell you that anti-fascist actions are important — even when they disrupt someone’s meal. The virtuous victims in “Schindler’s List” never protest. Because of this kind of representation, it’s easy for people to claim that protesters aren’t virtuous."

.........Or! OR! Hear me out here. Or maybe, just maybe, there could be another reason why the Holocaust doesn't look like a good match for someone being fired from ESPN, or for well-fed comfortable people protected by the rule of law yelling at a White House press secretary. Without checking - without doing even a five-second Google search - I am willing to declare as an absolute immutable fact of the universe that Noah Berlatsky considers Sarah Huckabee Sanders to be more dangerous, more fascist, and more Nazi-like than he does Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

The overall mentality is that real life must be a screenplay - according to Berlatsky's written cues. Real life must be cinematic - according to Berlatsky's direction. And anything that differs from Berlatsky's internal script - "AOC uses the Infinity Gauntlet to stop voter ID laws which are the new Nazism" - is simply not credible as real life, as real history, and must be discarded and replaced by more of what he saw on Twitter.

After a long lecture, of course.

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

But for Morrison that's not what superhero comic are about. The point isn't the resolution with the villain in jail, but rather all the loopy ideas along the way – a genius talking ape in love with a disembodied brain; a world full of talking chairs; a Satan who gets upset when you criticize his singing. Comics aren't necessarily about reinforcing the status quo or overturning the status quo, but about opening up a space to imagine somewhere else – a place where even the police get to take LSD trips and the ugly and the weird and the other don't need to be fixed. As the last line of Morrison's run says, "There is another world. There is a better world. Well, there must be."

Grant Morrison's Doom Patrol: The Craziest Superhero Story Ever Told - Noah Berlatsky

#comics#dc comics#dc#superheroes#superhero comics#comic books#grant morrison#doom patrol#Noah Berlatsky#I think about this article a lot

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://twitter.com/nberlat/status/1374226903431778306

One of the problems with talking about the power parents have over children is that people are like, “so what do you do” and the answer is… there aren’t good solutions.

Basically our whole society is set up around the nuclear family as an ideal and giving parents pretty much unquestioned power over kids. There’s some law enforcement policing of the worst abuses, sometimes… but LE is also incredibly abusive and dangerous for kids.

Really addressing these power imbalances would require sweeping social changes that would make society pretty much unrecognizable. The power disproportion between parents and children is just fundamental to our social life.

There are some things we could do! End laws allowing teachers and parents to hit kids. Abolish the voting age. Make college free. Provide no questions asked housing to young people. Provide a UBI for young people.

I think that would all help to some extent in various ways. But the fact that even surface efforts to ameliorate this problem aren’t on the table is a good sign of just how entrenched and difficult it is.

And so people are like, well not worth talking about then.

But you can’t even begin to solve a problem if you won’t admit it’s a problem.

People like the idea that parents are good and will not harm their kids, too. Even though there’s just tons of evidence that that is not true. (Anyone given huge amounts of power is likely to abuse it in some ways.)

Wrote about this at greater length here.

#repost of someone else’s content#twitter repost#article#Noah Berlatsky#adultism#youth rights#I mean the solution seems obvious to me#(guns)

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

via Garbage Day

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Comics: Growing Old with the X-Men

by Noah Berlatsky

[ed. note: a prior iteration of this article appeared as “Growing Old With the X-Men” on Patreon in 2022]

A friend lent me The Uncanny X-Men #160 (Marvel, August 1982) when I was at summer camp in the early 1980s. I wouldn’t say it’s exactly haunted me ever since. But it disturbed me at the time, and it stuck with me as a confusingly nightmarish story—a gratuitous exercise in disempowerment and decay.

Reading it again some forty years later through the power of digitization, I’m more aware of its weaknesses. Writer Chris Claremont’s endless exposition eats up text bubble after text bubble. Penciller Brent Anderson struggles with pacing the convoluted script—moments of grotesque horror (like Kitty Pride’s skeleton literally being removed from her body) are weirdly shrunken into a series of smaller panels so you can barely see them. I’d thought some of my fuzzy memories of the comic were a result of time and distance. But it turns out that a lot of scenes just aren’t drawn in a way designed to stick in memory.

At the same time, it’s, clearer to me now why I found the comic so unsettling then, and why, as an adult, it still retains some power. Claremont, in his clumsy, gauche way wrote a comic about the clumsy, gauche process of getting old. The innocuously named “Chutes and Ladders” turns out to be a story about decay, death, and failure. When I read it as a twelve-year-old, I was looking through a dimensional portal to the more jaded, (somewhat) hideously transformed me reading it now.

The plot starts out on the X-Men’s new island base. Storm, Nightcrawler, Wolverine, Kitty, and Colossus are participating in one of those Danger Room training battles with which Claremont was endlessly fascinated. Illyana, Colossus’ six-year-old sister is fascinated too; she’s watching eagerly, which positions her as a stand in for the audience. At the same time, she herself is being watched through a kind of interdimensional television by a mysterious figure with ominously long fingernails.

That obscured figure is a Satanic stand-in named Belasco, and his realm is Limbo. He’s a devilish demiurge for Claremont himself, setting the story in motion and summoning the reader deeper. He reaches into Illyana’s mind, whispering, “Tell no one, Illyana. Just follow my voice…to paradise.” The creepy child abduction connotations foreshadow the story’s obsessions with corruption, as Ilyana wanders off (clutching a Fozzie Bear doll). Kitty—the youngest member of the X-Men—notices Illyana’s gone and heads after her.

Illyana seems to vanish, and then Kitty is also zapped away. This sequence is presented as unpleasant in a way that is far out of proportion to what we see or what actually seems to be happening. Kitty is frozen in a circle of light and completely panics: “What’s happening?! I feel—No! Oh no!” She doesn’t sound like a superhero, but like a child facing her worst fear.

The older heroes figure out the kids are gone eventually; they follow and inevitably vanish. They all find themselves, or lose themselves, in an ill-defined gothic cavern-like realm—again, called Limbo, though it looks more like Hell.

The real horror here isn’t the décor, nor even the monstrous Sy’m, who talks incongruously like a 1920s gangland thug. (“So tell me boss—who do you want killed?”) The real horror is age.

The X-Men aren’t just visiting a different realm, but their future selves. Thanks to time displacement and cosmic comic book woo, our heroes learn that they were already in Belasco’s realm years or decades past, when they had been easily and gruesomely defeated. Wolverine’s adamantium skeleton lies in Belasco’s throne-room. Colossus apparently lived for some time, but he too was eventually killed; his aged corpse hangs on a wall. Or at least, Claremont says Colossus was an old man when he died. Anderson’s art doesn’t really show it, which is no doubt in part simply technical insufficiency, but which also suggests that age can’t be imagined; it’s a horror beyond visualization, even when it’s hanging there in front of you.

Worst of all is Nightcrawler. Our gallant, high-spirited Kurt didn’t die. He was instead turned into a corrupted parody of himself, a lecherous giggling monster matching his demonic appearance. When Kitty meets old, gross Kurt he gropes her, in an extremely unpleasant sequence. (Anderson’s pencils again don’t let you see clearly what’s going on, though this time it’s obviously intentional; Kurt’s hands when he gropes Kitty are off panel.) The sexual implications echo Belasco’s quasi-seduction of Ilyana at the comic’s opening; growing up here is shadowed with violence.

Elder Ororo’s fate is less grim than death or corruption. But time has still taken her on. After watching her friends die horribly, she reached some sort of détente with Belasco. As she aged, she lost her elemental powers, but studied sorcery instead. She uses her latter-day magic and her knowledge of the workings of the teleport circles to help the younger X-Men avoid the mistakes of the dead by urging them to run away.

They do so, but Belasco manages to grab Illyana’s hand. Kitty loses her grip on the girl for a second, but then gets hold of her again and pulls her back to our world—only to discover that in that blink of an eye when their hands were separated, Ilyana aged seven years, and is now thirteen.

That lost moment, in which a whole life happens between panels, is the part of the comic I remembered best. I’d sometimes over the years wonder what happened to Illyana, that same impenetrable gap fixed there as I got older, doing whatever I was doing. Time passed for me around that panel as it passed for Illyana inside it. You’re always getting older in that white gutter between then (further and further ago) and an ever more decrepit now.

The jump disturbed Colossus too. “How can I face our parents?” he wonders, and in a further internal monologue he muses on his sister’s tragic fate. “Childhood should be the happiest of times—and in a stroke, Illyana has lost that forever. Worse she has now spent half her life in Limbo […] should I welcome her, comfort her, love her…or fear her?” Belasco, though, gets the last word, cackling about Illyana’s glorious destiny while clutching her Fozzie Bear doll, a symbol of youthful innocence lost.

Contra Colossus, childhood isn’t always a happy time, as “Chutes and Ladders” is aware. Kitty’s outsized fear upon being transported into limbo, coupled with Nightcrawler’s advances, suggest that the comic is in part about sexual abuse. Belasco is grooming Illyana for his own purposes (further explicated in a Magik mini-series, which I still haven’t read). He’s an evil father, with elder Ororo, who dabbles in dark magic, as a compromised, also-abused mother figure. Colossus is grappling with the fact that aging can be imposed by adults in ugly ways; the comic is in part about how children like Kitty may be forced to contemplate their own skulls before they should have to.

The comic isn’t just about children though, which is part of what made it memorable for me when I was a child. To some degree, Claremont was writing for twelve-year-olds. But he was writing for those twelve-year-olds about what it’s like to grow up. Part of the superhero empowerment fantasy is that the characters never grow old; Colossus is still in his prime now, in 2023, just as he was in 1982. But also somehow in 1982, in that one comic, he was vaguely old, in a way difficult to visualize, and defeated and dead.

Belasco is evil, but he’s also age personified, and evil and age, intertwined, beat the X-Men, not once, but twice. They grow weak, they die. They are frozen and terrified. They betray themselves in grotesque ways and in smaller ones. They harm their friends (Sy’m uses Wolverines severed claw to pierce Colossus’ armor.) They fail to protect their loved ones. They run away. But wherever they run, time comes after them.

I vaguely understood when I was a kid that—through Anderson’s vague outlines and Claremont’s endless text—the comic was speaking to me about my own future. It was teleporting me forward in time to an older, tireder, heavier, more defeated me. And here I am, looking back. I could tell my 12-year-old self to run, I suppose, but it wouldn’t do much good. Back there, somewhere, I put the comic down and went off to swim more efficaciously than I can now. When, like Kitty recapturing Illyana’s hand, I picked the book up again, I liked it less, and, alas, understood it better.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

This 'Man' Is NOT A Hero!!!

Two weeks ago, I was horrified by the murder of a Black homeless man, Jordan Neely, by a white man on a New York subway train. But then, horror turned to rage when I saw some of the reactions, with people calling Mr. Neely’s murderer a “hero” and then when a GoFundMe account was established for his legal defense, it quickly amassed over $2 million!!! WHAT THE SAM HELL is wrong with people in…

View On WordPress

#Aaron Rupar#Daniel Penny#Jordan Neely murder#Kid Rock#New York subway murder#Noah Berlatsky#Thomas Zimmer#white supremacy

0 notes

Text

Loop Hero – why do gaming gods do bad things?

By Neil Merrett

Loop Hero, released on Nintendo Switch in 2021, Developed by Four Quarters

Loop Hero charges players to be a god-like being that does bad things in order to make a good hero. It turns out that a theological exploration of why we seek to make meaning out of traps and spider-pits can also make a pretty entertaining rogue-like adventure.

The ‘god sim’ was a term coined in the…

View On WordPress

#&039;God Sim&039;#god games#Loop Hero#Nintendo Switch#Noah Noah Berlatsky#theodicy#Thor: Love and Thunder

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Conspiracy theories undermine faith in a shared truth or a shared community. MAGA isn’t really trying to get people to believe any one story. They’re just trying to sow doubt. If nobody can be trusted, if everyone is corrupt, then Trump and his ilk are no worse than anyone else. Conspiracy theories alienate people from the democratic process. That’s good for Trump, who hates democracy.

In MAGA world, there are no accidents - by Noah Berlatsky

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

December 30, 2023

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

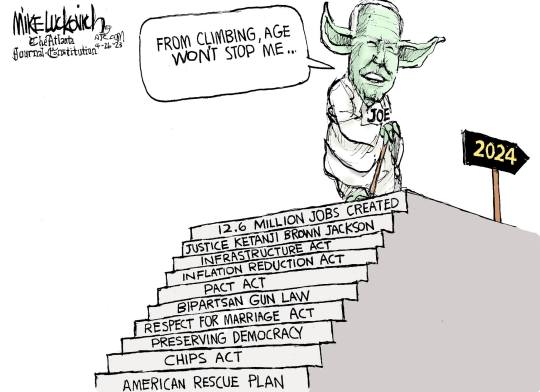

DEC 31, 2023

One day short of his first 100 days in the White House, on April 28, 2021, President Joe Biden spoke to a joint session of Congress, where he outlined an ambitious vision for the nation. In a time of rising autocrats who believed democracy was failing, he asked, could the United States demonstrate that democracy is still vital?

“Can our democracy deliver on its promise that all of us, created equal in the image of God, have a chance to lead lives of dignity, respect, and possibility? Can our democracy deliver…to the most pressing needs of our people? Can our democracy overcome the lies, anger, hate, and fears that have pulled us apart?”

America’s adversaries were betting that the U.S. was so full of anger and division that it could not. “But they are wrong,” Biden said. “You know it; I know it. But we have to prove them wrong.”

“We have to prove democracy still works—that our government still works and we can deliver for our people.”

In that speech, Biden outlined a plan to begin investing in the nation again as well as to rebuild the country’s neglected infrastructure. “Throughout our history,” he noted, “public investment and infrastructure has literally transformed America—our attitudes, as well as our opportunities.”

In the first two years of his administration, when Democrats controlled both chambers of Congress, lawmakers set out to do what Biden asked. They passed the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan to help restart the nation’s economy after the pandemic-induced crash; the $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (better known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law) to repair roads, bridges, and waterlines, extend broadband, and build infrastructure for electric vehicles; the roughly $280 billion CHIPS and Science Act to promote scientific research and manufacturing of semiconductors; and the Inflation Reduction Act, which sought to curb inflation by lowering prescription drug prices, promoting domestic renewable energy production, and investing in measures to combat climate change.

This was a dramatic shift from the previous 40 years of U.S. policy, when lawmakers maintained that slashing the government would stimulate economic growth, and pundits widely predicted that the Democrats’ policies would create a recession.

But in 2023, with the results of the investment in the United States falling into place, it is clear that those policies justified Biden’s faith in them. The U.S. economy is stronger than that of any other country in the Group of Seven (G7)—a political and economic forum consisting of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, along with the European Union—with higher growth and faster drops in inflation than any other G7 country over the past three years.

Heather Long of the Washington Post said yesterday there was only one word for the U.S. economy in 2023, and that word is “miracle.”

Rather than cooling over the course of the year, growth accelerated to an astonishing 4.9% annualized rate in the third quarter of the year while inflation cooled from 6.4% to 3.1% and the economy added more than 2.5 million jobs. The S&P 500, which is a stock market index of 500 of the largest companies listed on U.S. stock exchanges, ended this year up 24%. The Nasdaq composite index, which focuses on technology stocks, gained more than 40%. Noah Berlatsky, writing for Public Notice yesterday, pointed out that new businesses are starting up at a near-record pace, and that holiday sales this year were up 3.1%.

Unemployment has remained below 4% for 22 months in a row for the first time since the late 1960s. That low unemployment has enabled labor to make significant gains, with unionized workers in the automobile industry, UPS, Hollywood, railroads, and service industries winning higher wages and other benefits. Real wages have risen faster than inflation, especially for those at the bottom of the economy, whose wages have risen by 4.5% after inflation between 2020 and 2023.

Meanwhile, perhaps as a reflection of better economic conditions in the wake of the pandemic, the nation has had a record drop in homicides and other categories of violent crime. The only crime that has risen in 2023 is vehicle theft.

While Biden has focused on making the economy deliver for ordinary Americans, Vice President Kamala Harris has emphasized protecting the right of all Americans to be treated equally before the law.

In April 2023, when the Republican-dominated Tennessee legislature expelled two young Black legislators, Justin Jones and Justin J. Pearson, for participating in a call for gun safety legislation after a mass shooting at a school in Nashville, Harris traveled to Nashville’s historically Black Fisk University to support them and their cause.

In the wake of the 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Supreme Court decision overturning the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision that recognized the constitutional right to abortion, Harris became the administration’s most vocal advocate for abortion rights. “How dare they?” she demanded. “How dare they tell a woman what she can and cannot do with her own body?... How dare they try to stop her from determining her own future? How dare they try to deny women their rights and their freedoms?” She brought together civil rights leaders and reproductive rights advocates to work together to defend Americans’ civil and human rights.

In fall 2023, Harris traveled around the nation’s colleges to urge students to unite behind issues that disproportionately affect younger Americans: “reproductive freedom, common sense gun safety laws, climate action, voting rights, LGBTQ+ equality, and teaching America’s full history.”

“Opening doors of opportunity, guaranteeing some more fairness and justice—that’s the essence of America,” Biden said when he spoke to Congress in April 2021. “That’s democracy in action.”

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#Letters from An American#Heather Cox Richardson#Biden Administration#Biden's accomplishments#Election 2024#Mike Luckovich

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fatness began to be hated when it was connected to Blackness. Race scientists began to obsess over the supposed excessive fleshiness of Black women, especially—even though these bodily differences were largely invented out of whole cloth. “It is not that fat bodies were first stigmatized and then Black bodies became associated with fatness;” Manne explains. “Rather, Black bodies were first associated with fatness, and then fatness came to be stigmatized soon afterward.” White upper-class women were framed as thin, delicate, and worthy of protection; Black women’s (supposed) fatness made them sturdy and coarse and rationalized their exploitation.

What’s striking here is that the advance of “science” actually led to an active, and deliberate, loss of commonsense knowledge and even a loss of an ability to make straightforward observations and inferences. People knew that fat is not linked to appetite and gluttony—and then they forgot. People knew that fat people were attractive, and then they erased the knowledge.

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

There was a Shoah movie where the Jews fought back: Defiance, and everyone HATED IT because they projected some kind of judgment onto the Jews who "went quietly to their deaths" when that wasn't the message of that movie at all. So it doesn't really matter whether the Jews resist their genocidal oppression or not, it'll get criticized and problematized and thinkpiecified no matter what.

I also find it funny that Schindler's List has nothing to "teach" because it is literally a Hollywood structure of the Hero's Journey. Oskar Schindler has to learn about Jewish suffering and to value Jewish life, and use every tool in his arsenal to try to save the people he grows to care about. Several Jewish characters lecture him on their plight and he goes from dismissive to never being able to bear the psychological weight of not getting just 1 or 2 more Jews out.

It's a movie about the man who has everything to gain from exploited Jewish labor and suffering, who is barely moved by the oppression he sees, to being horrified by the dehumanization and slaughter taking place, who risks everything to rescue as many people as he can. It's a parable of what it is the average person's responsibility to do. The message is clear: If you find yourself being an Oskar Schindler in times of oppression and genocide, your duty is to become the kind of person he became.

Like sorry I won't stand for Schindler's List slander!

SL is in very rare company, if not unique, in being a Holocaust film that is historically accurate, artfully made, and - this term seems really inappropriate - "watchable." I've watched it twice and could see myself watching it a third time someday, likely when my kids are old enough. It has legitimate educational, historical value.

It also has shortcomings. It sets viewer expectations to normalize Gentile saviors, grateful Jews, quasi-happy endings. It is very, very much the exception to the rule of those years. A more fair, representative movie about the Holocaust was "The Gray Zone." Relentlessly bleak, tortuously painful, the Jews do scrape together an uprising, then they all die anyway. It's really what history classes should be watching, I'm sure most teachers wouldn't dare, and having watched it once myself I'm sure I can't sit through it again.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bloomberg hit piece against ‘Sound of Freedom’ penned by pro-pedophile advocate

"The person who wrote this Bloomberg opinion piece is leftist activist Noah Berlatsky. He was the spokesperson for M.A.P. (minor-attracted person) advocacy group, Prostasia. In 2017, he tweeted that pedophiles are a stigmatized group who get designated as deviants for hateful purposes,” freelance journalist Andy Ngo wrote on Twitter.

Berlatsky was formerly the communications director for Prostasia, which bills itself as a “child protection organization that combines our zero tolerance of child sexual abuse with our commitment to human and civil rights and sex positivity.”

The website advertises a “support group for minor-attracted people (MAPs) who are fundamentally against child sexual abuse and committed to never harming children.” The site showcases some of Berlatsky’s work including an essay from 2021 titled, “Child trafficking narratives are misleading,” where he outrageously defended the “autonomy” of child prostitutes."

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

AMAZING word just now introduced to me by noah berlatsky (getting drinks w/ him in the new year!)... great for republicans and centrists, if the shoe fits!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mariah Carey 🦋

Referred to as the "Songbird Supreme" by The Guinness Book of World Records, she is regarded as one of the greatest singers in the history of music and is noted for her songwriting, five-octave vocal range, melismatic singing style and signature use of the whistle register. An influential figure in popular music, Carey is credited with influencing vocal styles, merging hip-hop with R&B and pop through her collaborations and popularizing remixes.

youtube

Carey rose to fame in 1990 with her self-titled debut album under the guidance of Columbia Records executive Tommy Mottola, whom she later married in 1993. She is the only artist to date to have their first five singles reach number one on the Billboard Hot 100, from "Vision of Love" to "Emotions". Carey gained worldwide success with her albums Music Box (1993) and Daydream (1995)―both of which rank among the best-selling albums and spawned singles such as "Dreamlover", "Hero", "Without You", "Fantasy", "Always Be My Baby" and "One Sweet Day". The lattermost of these topped the US Billboard Hot 100 decade-end chart (1990s). After separating from Mottola, Carey adopted a new urban image and began incorporating hip-hop and R&B elements with the release of Butterfly (1997) and Rainbow (1999).

youtube

Her album Butterfly has been credited for revamping Carey's image as a pop star where she began to embrace hip hop and R&B themes and fully come into her own self, resulting in butterflies becoming a metaphorical symbol of her impact and legacy upon pop and R&B music.

By the end of the 1990s, Billboard ranked Carey as the most successful artist of the decade in the United States. She left Columbia Records in 2001 after eleven consecutive years of US number-one singles and signed a record deal with Virgin Records.

Following a highly publicized breakdown and the failure of her film Glitter and its accompanying soundtrack, Virgin bought out Carey's contract, and she signed with Island Records the following year. After a brief, mildly successful period, Carey returned to the top of the charts with The Emancipation of Mimi (2005) which became one of the best-selling albums of the 21st century. Its second single, "We Belong Together", topped the US Billboard Hot 100 decade-end chart (2000s).

youtube

In 2018 she released the album Caution. The lead single With you became Carey's highest-charting non-holiday song on the US Adult Contemporary chart since "We Belong Together" in 2005. It was followed by a second single, A No No, a R&B and hip-hop track which samples Lil' Kim's Crush on You" (1997) . Caution received universal acclaim from critics; it debuted at number five on the Billboard 200.

youtube

Her subsequent ventures included roles in the films Precious (2009), The Butler (2013), A Christmas Melody (2015), and The Lego Batman Movie (2017), being an American Idol judge, starring in the docu-series Mariah's World, performing multiple concert residencies, and publishing the memoir The Meaning of Mariah Carey (2020).

Carey has been called a pop icon and has been labeled a "diva" for her stardom and persona. She said, "I have had diva moments, and then people can't handle it. I guess it's a little intense, because I come from a true diva: My mother is an opera singer. And that's a real diva, you know—Juilliard diva. And I mean it as a compliment, or I wouldn't be the person I am without experiencing that."

Her style has often been described as "eccentric" and "over the top". Writer Noah Berlatsky noted that "Carey has always reveled in uber-feminine, girly imagery", with her album titles such as Butterfly, Rainbow, Glitter and Charmbracelet being prime examples.

Carey is one of the best-selling music artists, with over 220 million records sold worldwide and is an inductee of the Songwriters Hall of Fame, the National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress and the Long Island Music and Entertainment Hall of Fame.

#mariah carey#1990s#1990's#90s#90's#90's music#90s aesthetic#90s fashion#90s r&b#90s rnb#90s music#vintage#vintage photography#portrait#vision of love#melisma#Youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Comics: Comics Needs Jacob Lawrence, Not Crumbs of Freedom

by Noah Berlatsky

[ed. note: a prior iteration of this article appeared as “Crumbs of Freedom” on Patreon in 2019]

Canons aren’t just descriptions of the most important artists in a field. They’re a proscriptive vision of what art should be, and how you should interact with it. Brian Doherty at Reason makes that very clear in his extensive 2019 defense of R. Crumb.

The article was responding to an incident in which cartoonists at the Ignatz Award in 2018 booed Crumb (who was not attending) as a racist and a sexist. Doherty is admirably careful to point out that these boos were simply an exercise of free speech, not some sort of censorship of Crumb. But he argues that the exercise of that speech, the liberty of critique, is in fact a gift from Crumb himself. “Crumb’s attempt to open comics to a vast range of human expression was victorious,” Doherty writes. He continues:

Whether they want to acknowledge it or not, those working in the field today are his descendants. Like all children and grandchildren, they can choose whether or not to understand their patriarch, whether to emulate him or tell him to fuck off. Their choices may not always be kind or wise, but such is human freedom.

For Doherty, Crumb defines the parameters of comics possibility for all creators, “Whether they want to acknowledge it or not.” Creators can embrace Crumb, or they can reject Crumb, but it is always Crumb they are embracing or rejecting. He is the problematic father who successors must adore or kill. Creators cannot, in Doherty’s view, pick and choose their influences; they can say they reject Crumb, but their freedom to do so is just more evidence of their debt to him. “Anyone making noncorporate, nongenre, self-expressive comics occupies a space [Crumb] created,” Doherty says. He praises human and artistic freedom, but that freedom has strict limits. And the name of those limits is “Crumb.”

Doherty is correct; Crumb does occupy a unique place in comics. Crumb treated comics, not as genre adventure, but as a way to pour out his neurosis, sexual obsessions, racist fantasies, and political irritations on the page. Anything in your head could go into your comics, Crumb insisted. That’s been inspiring for autobiographical cartoonists like Art Spiegelman and Alison Bechdel. And it’s been a way to lend comics legitimacy, which is why Crumb has been so important to Gary Groth, editor of The Comics Journal, and publisher of Fantagraphics, one of the most important independent comics imprints.

But the question is: is Crumb canonical because his work is important? Or is his work important because it’s canonical? In other words, does self-expression, controversial content, and legitimacy in comics have to pass through Crumb, as a historical inevitability? Or has the critical elevation of Crumb been something of a self-fulfilling prophecy? Is Crumb what people find to open them to possibilities, or is he the possibility people are offered? To put it another way, what options are closed down, and what traditions are excluded, when all comics are said to be in conversation with this one guy?

One artist that gets excluded from a Crumb-dominated discussion of comics is Jacob Lawrence.

Lawrence is a well-known figure in visual art; he’s one of the seminal African-American painters of the twentieth century. His work isn’t generally thought of as comics for various reasons. One innocuous one is that his art generally hangs in galleries, rather than being reproduced in pamphlets. A more disturbing possibility is that comics traditions and iconography has been shaped by traditions of racist blackface caricature, and antiracist work is therefore marginalized within the comics subculture.

But whatever the reason for Lawrence’s exclusion, it’s not that difficult to recuperate him for comics if you’re willing to look at his work with fresh eyes. Lawrence’s wonderful The Legend of John Brown, for example, is a series of twenty-two 20” x 14” images with text—or pages, if you will—originally completed in 1941, but typically displayed as a series of screenprints completed in 1977. While it’s not in a mass-market pamphlet format, the work is presented as a series of prints.

Lawrence’s figures are simplified, distorted, and deliberately flat; he’s working from a mural tradition which parallels, and overlaps with, cartooning. More, The Legend of John Brown is a narrative series, and each image is accompanied by a short text description/explanation. By Scott McCloud’s definition of comics as “Juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer,” The Legend of John Brown is more comics than The Far Side.

More importantly, I think Lawrence and comics have something to offer each other. Each of the images of The Legend of John Brown is striking on its own, but the work gains in complexity and power when it is considered as a whole narrative work. Typical galleries of this work do Lawrence a disservice by not organizing the prints in sequence or by not including Lawrence’s text. Treating the work as discrete images, rather than as a single comic, undersells Lawrence’s artistry.

For example, the first page in the series (above) shows Brown contemplating a giant, crucified Christ, the cross stark against the hill and sky. It’s an image which puts us in the place of Brown, gazing upon a large, awesome, open spectacle of death, obligation, and blood (which flows copiously down Christ’s legs and onto the hillside.)

The second page is an abrupt shift; the text reads, “For 40 years, John Brown reflected on the hopeless and miserable condition of the slaves,” and the image shows him doing that, in a small house, with others praying around him. The cramped space, and the heads all bowing together, are emphasized by Brown’s own interlaced hands, a massed clump, in the center of the image. The insistent inward-turning is relieved by a skewed window at the side, through which a single bare tree reaches up to the sky—an echo of the cross on the first page. Communal resolution, between people, is undertaken in the shadow of God. Immanence takes on weight and power because of transcendence, and vice versa.

This back-and-forth between tight groupings of figures and flashes of space is an organizing theme throughout the comic. Page 6, “John Brown formed an organization among the colored people of the Adirondack woods to resist the capture of any fugitive slaves,” shows Brown in close consultation with a group of three black men, all clustered together around a pair of rifles Brown holds in both large clasped hands, their barrels making a cross. The next page, “To the people he found worthy of trust, he communicated his plans,” shows Brown at another table, a coat tree at his side (again echoing the cross), a window open behind him.

This symbolic emphasis on closing in and opening out are emphatically resolved on the final two pages. Page 21, “After John Brown’s capture, he was put on trial for his life in Charles Town, Virginia (now West Virginia),” shows Brown against a brown background as he slumps over a cross held in his clasped hands. It’s an image of cloistered intimacy; we can’t even see Brown’s face, which is bent and shrouded in his hair. The final page opens up to show Brown hanging by the neck against a deep blue sky. A cloud seems to reach out to him, forming a shadowy fist behind him, an echo of his own clasped hands, as if he’s now in fellowship with God.

If Lawrence gains from being considered as comics, I think comics also gains by including Lawrence in its canon. That’s not (just) because Lawrence is an amazing artist who would solidify comics status as a worthwhile art form. Rather, it’s because Lawrence offers formal and intellectual resources which comics artists could use.

The Legend of John Brown is especially impressive as a narrative, which (literally, one could say) draws the viewer into a political and moral community.

Political engagement in canonical comics, from editorial cartoons to Doonesbury to Crumb, often leverages cartooning’s power to ridicule in order to caricature and mock. Lawrence takes another tack. His comic is also public art, and the narrative insistently faces both inwards and outwards. On page 17, for example, we see Brown, face turned from us addressing a group of black men. The soldiers fill the panel—on both sides men’s arms are cut off by the border. This makes the image look cluttered and crowded; the group of people massing against racism can barely fit in the image. It also beckons to people off panel, like us. They’re listening to Brown, and we’re listening to Brown; we’re standing together.

The message is even more direct on the last page, which calls back to the first. Brown hanging in mid-air echoes Christ standing against the sky. And just as Brown was inspired by Christ’s body, the story calls us to be inspired by Brown’s. Lawrence’s politics are his comics. The twenty-second panel, the page which isn’t drawn, is a cluster of people which includes John Brown, God, and us.

The community that Lawrence includes us in is an antiracist one—and more, a revolutionary antiracist one. That is not a community that Crumb easily fits into.

Crumb has been widely praised for opening up artistic expression in comics, in part because of his use of racist and sexist caricatures, which are framed by fans as a daring violation of political correctness. But the truth is that racist caricatures have long been a part of comics iconography—Little Nemo, Tintin, The Spirit, Mickey Mouse, and more, all used blackface iconography. Crumb’s blackface imagery may be satirical, sometimes. But the satire, mocking Crumb’s own investment in blackface imagery by employing it, is still a far cry from a call for solidarity with black people, much less an actual demand for the violent overthrow of a racist system.

Crumb may open some possibilities for other cartoonists who are interested in autobiography, and in controversial imagery carefully disconnected from any sort of collective political program. But for cartoonists who might be influenced or inspired by Lawrence, Crumb is a barrier, not a resource. After all, if booing Crumb is an act of ignorant ingratitude, what to make of John Brown actually murdering people to try to overthrow the civilization that had given him those guns, and that Christ? Is antiracism just a perversion of a freedom given to you by a white guy? Or is it its own tradition, with its own power and its own inspirations?

This isn’t to say that comics has no radical collective tradition. On the contrary, comics includes Marxist cartoonists Art Young and Boardman Robinson, John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell’s March, Diane DiMassa’s Hothead Paisan, and for that matter the William Moulton Marston and H.G. Peter Wonder Woman. Those are all examples of consciously-political cartooning, which compliments and contextualizes Lawrence’s work. Crumb is much more canonical than any of these artists at the moment. But that’s a choice, not some sort of absolute truth.

Crumb opens certain possibilities for certain cartoonists. But those are not the only possibilities. People who reject Crumb aren't necessarily his children, and they aren’t necessarily in his debt. They may instead be trying to clear ground for alternate traditions, which have been buried and restricted—not liberated—by Crumb’s ascendance.

What would comics look like if Jacob Lawrence occupied the place of reverence and influence that Crumb has been granted? It’s impossible to know for sure. But a good guess is that they would be less white. It would also, in certain respects, be more free.

Had I so interfered on behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or on behalf of their friends […] and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference […] every man in this court would have deemed it worthy of reward rather than punishment.

—John Brown

0 notes