#mashalling yard

Text

Illinois Central Railroad freight cars at the South Water Street freight terminal in Chicago in April 1943 (credit Jack Delano)

#Illinois#Illilnois Central Railroad#South Water Street#freight terminal#mashalling yard#rail#railroad#infrastructure#logistics#Chicago#freight train

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

%news%

New Post has been published on %http://paulbenedictsgeneralstore.com%

Fox news Upset Ravens left reeling after Divisional Round loss to Titans - NFL.com

Fox news

BALTIMORE -- Mike Vrabel marched along his sideline, the meltdown initiated by his Tennessee Titans engulfing the Baltimore Ravens, a diminutive smirk -- his default expression, in fact -- on his face.

Derrick Henry had real thrown a jump-cross touchdown to place the Titans up by 22 facets and the AFC playoffs had been upended for the 2nd week in a row by a crew that is so relatively nameless reporters had to double test exactly when Dean Pees, the architect of the Titans defense that stifled the most electrifying offense of the season, had quit the Ravens and gone to work for the Titans. The reply is 2018.

It's about time to launch the shatter course on the Titans, on story of they've crashed the playoffs that had been presupposed to be dominated by the blueblood quarterbacks. Final week, they sent Tom Brady and the defending Interesting Bowl champions home and, perchance grand more pleasing, on Saturday they throttled the presumed league MVP Lamar Jackson and the AFC's high seed, forcing him into three turnovers and two failed fourth-and-1 makes an try in a 28-12 victory. They're going to play the winner of the Houston-Kansas City sport for the AFC Championship and a feature within the Interesting Bowl.

"Pro Bowl?" Jackson said, when requested about his plans for the following couple of weeks. "I desired to be within the Interesting Bowl."

That they did no longer even reach the AFC championship, and a doubtless dream matchup with the Chiefs' Patrick Mahomes, will haunt the Ravens this offseason. As will the evident quiz of: How did a 3-week relaxation for some key avid gamers, including Jackson, possess an impact on the Ravens' offense when faced with a crew that has been in must-take mode for a month. Jackson said having the closing standard season sport off, adopted by a bye, became as soon as no longer the likelihood.

"I maintain love we had been too excited," Jackson said. "We real got out of our ingredient rather too speedy, trying to beat them to the punch. We real had been unhurried this day rather bit."

But Coach John Harbaugh became as soon as no longer so adamant if the lengthy layoff may possibly well goal possess slowed his crew./p>

"I salvage no longer possess that reply," he said. "It's unanswerable. Our guys practiced in point of reality arduous and did the finest they may possibly well goal, but we didn't play a interesting soccer sport, for definite. What may possibly well goal serene you attribute that to? I speak it's doubtless you'll perchance theorize a quantity of assorted things."

In the locker room, the avid gamers had been more blunt. Designate Ingram, whose left calf became as soon as heavily wrapped at some stage within the sport and who ran for real 22 yards, said the Ravens got their butts kicked.

"This crew's identity true now may possibly well be to salvage to the playoffs and choke. It's a long way what it's. That is real the arduous truth," said cornerback Marlon Humphrey. Asked how this crew wants to be remembered, he replied: "As losers, I speak."

The Titans conducted a brutally bodily, fearless sport, dominating the lines of scrimmage. Quarterback Ryan Tannehill threw for real 88 yards, but Henry, the gargantuan working support, ran for 195, including a intestine-punch of a 66-yard bustle that feature up a third touchdown true after Jackson had been stuffed on a fourth-and-1 try. The Ravens had transformed 71 p.c of fourth down tries at some stage within the favorite-or-backyard season, but Jackson had nowhere to head in opposition to the Titans' defensive push. Jackson accounted for 508 scrimmage yards, despite the proven reality that a quantity of them got here when the sport became as soon as out of hand.

The Titans' opinion became as soon as easy in opinion and so sturdy to device that few completely different Ravens opponents had managed it. They badly desired to determine the Ravens from taking an early lead as they'd completed most of the season. And they also desired to drive Jackson to bustle laterally. They had eight or 9 avid gamers shut to the road of scrimmage to stifle Jackson and drive him to throw. On the Ravens' very first drive, a Jackson cross became as soon as tipped and intercepted, the first one he had thrown on a gap drive this 300 and sixty five days and real his seventh INT of the season. And most of all, they had been no longer awed, as completely different Ravens opponents had been, by their first explore at Jackson's dazzling dawdle.

"We seen when he became as soon as gaining yards," Vrabel said. "He became as soon as getting them between the hashes and the numbers. When we defended from quantity to quantity and made him lag laterally, they weren't substantial performs."

As quickly as they fell within the support of, the Ravens all but abandoned the bustle.

There became as soon as a odd dynamic amongst the Ravens. Some avid gamers love Ingram and Humphrey had been unsparing in their review of how the Ravens failed, with Humphrey noting that this crew is perchance no longer the same subsequent 300 and sixty five days. No longer a long way away, 13-300 and sixty five days guard Mashal Yanda declined to communicate about his future.

But Jackson became as soon as already taking a look forward. He has the back of youth to allow his two occupation playoff losses to disappear.

"This is my 2nd 300 and sixty five days within the league," he said. "Many of us are no longer in a position to bring it to the playoffs.

"We're a young crew, particularly on our offense. We're going to enhance. We handiest can enhance. It's handiest up from here."

That, obviously, is no longer essentially the case. With home-field back and the Patriots out of the list, the Ravens had an finest different to reach the Interesting Bowl. As a change, they'll likely cast off home a load of long-established season awards for Jackson and Harbaugh, and they also are going to head support to work, the next colossal thing no longer but completely arrived.

"Oh, or no longer it'll be the same reply at any time when," Jackson said. "I've started working on every thing. There's always room for enchancment."

And for that first playoff take.

Apply Judy Battista on Twitter @judybattista.

0 notes

Text

A Bad Kid

By Rahnaward Zaryab

Translated from Dari by Hamed Alipoor

From the July - December 2000 issue of Afghan Magazine | Lemar - Aftaab

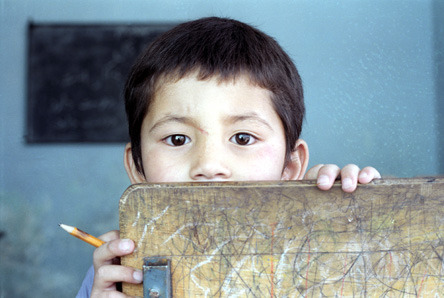

[caption: “Untitled” by Reyaz Nadi]

Rahward Zariab tells the story of a ruthless boy who terrorizes everyone in his small fiefdom, an accurate depiction of a diminutive tyrant, while unchecked from a proper upbringing, rains pain on anyone in his sight.

Now that I reflect, I know that I have always been a bad kid for my mom. Now, neither my mom is here nor my past; both have gotten woven in the long rope of life and will definitely not come back. Likewise, I will go one day and won't come back.

From the very far past, when I was very little, the most intimate image in my mind was that of my mother. What I received from this image was love and endless patience that used to give me the courage to do whatever I wanted to without any concern about its consequence.

My world was a small world, and I was its emperor, and my mom was like a gracious eagle protecting me from all its ills. Mom tolerated all my stubbornness. She could only vent her complaint and anger in one way, by saying, "You're a bad, bad kid!"

Back then, when I was still a child, I would look around and steal sweets and candy from home. When my mom would find out, she would get mad and scold me, always by saying, "You're a bad kid!"

When I grew a little older, I became more mischievous and less scared. I expanded my little world. I was a self-absorbed emperor and thought the world revolved around me. I would break my neighbor's windows and viciously beat up my playmates until they bled. Everyone would go to my mom and complain, and some would even start big quarrels with her.

My mom would apologize to them daily or sometimes would start arguing with them. When she saw me, her face would have lovely anger. And she would say, "You're a bad kid!"

One day, a man who was selling toys came to our street. Among his toys, I saw a watch that was all golden, even the hands. It had a red wristband. I really liked the watch and asked the man for its price. In a chant, he said, "It is a Japanese watch, it comes from a pretty land, look carefully, look, only two afghanis."

My heart was filled with the desire of having that watch. I thought about where I would get that kind of money. In my poor empire, there was nowhere I could get that much money.

"Want to trade it with some eggs?" I asked the man.

"If it's fresh yes, get me five of them!", he replied. "All right then, get them!" he responded.

I went home. At home, we had a hen that was getting ready to give us some chicks. My mom had put six eggs under the hen so that they would hatch; mom used to give the hen special foods to speed up the process.

When I went to the basement, the hen made lots of noise. I took her by her wings and threw her in a box. Then, I took five of the eggs; they were so warm. I cleaned them with my shirt and traded them for the watch. I got the watch and trotted towards the house, chanting, "It is made in Japan; it is so beautiful."

At home, I saw mom feeding the hen. The hen was making lots of noise. There was only one egg left. My mom was sobbing. She had a strange look in her eyes. In a sad voice she said, "In just a few more days, they would have hatched."

As I was looking at the hands on my watch, I said, "What do I care about the chicks?"

Looking at me she said, "You're a bad boy!", and added, "You're so cruel."

Later when I grew up, I was dissatisfied with everything. Everyone had made me angry. I was fighting everyone and everyone was fighting me. Using my belt, I used to beat up my sister who had a bony body. She would use her hands for protection and would cry and ask my mom for help. Mom would yell at me. I would yell back, "Go away!"

And my mom would say nervously, "Oh God! He is going to kill that girl!"

And I would yell, "Yes, I would kill, I would kill."

Everything would be a mess around our house. Our neighbors would try to see what is happening, and I would curse them. In the height of her rage, my mom would say, "You're a bad boy!"

One day I had a big fight on the street. Over what, I don't recall. But it was about someone invading my empire, and I was very angry. I came home with torn clothes, bleeding. Mom looked at me pitifully as if she was expecting me to come home looking like this. I went to my room to get my knife, but it wasn't there. I searched the entire room but couldn't find it.

"Where is my knife?", I yelled violently.

I came to the yard of our house and saw my mom standing by the well. She seemed distraught and was shivering. "If you come close, I will slash myself."

She was holding my knife.

My heart was beating really fast. I felt as if sweat and blood were running all over my skin. My clothes were stuck to my body. The blood coming from my left temple was making it difficult for me to open my eyes. I told my mom, "Give me my knife!"

She responded, "I will slash myself."

She had a violently decisive look in her eyes. But all I could think of was my own empire and its victory. Slowly, I walked towards my mom. Mom raised the knife and screamed, "I swear to God, I will slash myself."

It was a scary scream. My sister threw herself at my feet and cried, "Don't go near."

I touched my bloody temple and showed the blood to my sister. "How can you take revenge of this blood?" I asked.

And no one answered. I yelled, "Only with blood! Only with blood!"

There was a commotion in my head. I couldn't see very well. I kicked my sister hard to get her away from me. I went toward my mom. Our neighbors pulled me away from her.

I kept on yelling, "Give me my knife."

And I felt that my empire was getting smaller, and my enemies were winning.

I didn't leave home for the next few days. I looked for any excuse to get mad. I would beat up my sister with my belt. I often broke the plates of dinner that my mom brought me. Mom only would say, "You're a bad boy!" and sigh.

Later, I became more hot-tempered and did much worse things. I went to jail and got out. I became worse.

It had been years since my mom had lost her youth. Her hair was white, her face wrinkled. My sister had married and had gone to a new home with her husband. I was more hot-tempered and violent than ever. I would call my mom, who was so alone at the time, bad names. I would curse her, and she would sob and say, "God, that is all I deserved in this world, a bad kid."

The day that my mom was dying, that got me somewhere. I was drunk and was laughing. They told me, "Your mom is dying."

I responded, "So, what can be done? We all die one day."

They told me, "She has asked for you."

I responded, "What can I do? Tell me, what can I do?"

Finally, they took me to her. When she saw me, a faint smile appeared on her face. Slowly I walked toward her. Her lips moved and when I got my ears near her mouth, she whispered, "Everyone hates you, no one wanted to let you know."

Lots of things came to mind, and I couldn't hear anything else. My mouth was dry. It appeared to me that my empire was getting smaller. I felt that rage and anger again.

I got up, pulled out my knife, and yelled, "Who wouldn't come and tell me about my mom?"

There was complete silence in the room, and I yelled again, "Tell me, who?"

I leaped and got the first man who was near me by the color and yelled, "Why didn't you come?"

The man didn't say anything. I raised my knife to slash his throat. Suddenly, mom screamed with all her might and called me by the name that she hadn't called me since my childhood, "Shayruk!"

I turned my head. Her face was pale. She didn't say anything else. She couldn't. But I knew what she wanted to say. She wanted to say, "You're a bad kid!"

I felt that I had lost the very foundation of my empire. I threw myself over my mom's dead body. At that time, all I was thinking about was my endless loneliness. Yes, loneliness.

About Rahnaward Zaryab

Rahnaward Zaryab is an Afghan novelist, short story writer, journalist, and literary critic/scholar. He was born in 1944 in the Rika Khana neighborhood of Kabul, Afghanistan.

Further Reading:

Celebrated Afghan Writer Recalls Kabul Of Decades Ago NPR Audio

Writer Retreats to a Kabul That Lives Only in His Memories and Books New York Times By Mujib Mashal

0 notes

Text

As Afghan Soldier Kills 2 Americans, Peace Talks Forge Ahead

NANGARHAR, Afghanistan — President Trump stood in a misty drizzle at Dover Air Force Base as the remains of America’s latest two casualties in the long war in Afghanistan arrived home.

The somber silence was shattered by anguished cries from the young widow of Sgt. First Class Javier J. Gutierrez, who sprinted toward the plane as the metal cases holding her husband’s body and that of Sgt. First Class Antonio R. Rodriguez were being pulled out. “No!” she screamed, calling out his name over and over.

Just hours before that brief ceremony on Feb. 10, President Trump had made a momentous decision, giving his diplomats a green light for a peace deal with the Taliban that would lead to an American troop withdrawal and, possibly, the beginning of the end of the United States’ longest war.

This was once called “the good war,” “the war of necessity.” When American soldiers invaded Afghanistan in 2001 — driven by the Sept. 11 Qaeda attacks on American soil — and toppled the Taliban’s oppressive government, they were welcomed by large parts of Afghan society.

But since then, the war has become a bleeding stalemate in which even some Afghan soldiers turn their guns on American service members, viewing them as invaders instead of partners. The American sergeants mourned at Dover Air Force Base were killed by an Afghan soldier whose uniform, salary and M249 light machine gun were paid for by the United States.

Of the roughly 3,500 total American and NATO deaths in this war, American officials say, more than 150 have been killed in such “green-on-blue” attacks — assaults so destructive to the American mission that they have their own terminology to describe them. The problem has been so pervasive that soldiers are assigned to guard their American comrades who mix with Afghan forces. They have a special name, too: Guardian Angels.

When the war began, in the autumn of 2001, Sergeant Gutierrez and Sergeant Rodriguez were just boys. Sergeant Jawed, the Afghan Army soldier with a single name who would become their killer, was a toddler. By the time their paths crossed nearly two decades later in a dusty, eastern Afghan village, all three men had become old hands at war.

The army’s Seventh Special Forces Group that the two sergeants belonged to had been in Afghanistan just a few weeks. But Sergeant Gutierrez, of San Antonio, Texas, and Sergeant Rodriguez, of Las Cruces, New Mexico, had joined in 2009. Sergeant Gutierrez, a father of four, deployed to Iraq as an infantryman before heading to Afghanistan as a Green Beret. Sergeant Rodriguez had completed 10 tours in Afghanistan, first as an Army Ranger and later with the Special Forces.

Their Special Forces team was back in Afghanistan just as peace talks were reaching a peak again, along with efforts to hold the line against the Taliban in the field and pressure them to stay at the negotiating table.

In Shirzad district, in the eastern province of Nangarhar, the Afghan Army had pushed back the Taliban. But the operations were stuck. So on Feb. 8, a group of Afghan commandos accompanied by the Green Berets arrived early in the morning in helicopters to see if they could help, according to interviews with more than a dozen Afghan and American officials.

The Afghan Army battalion had taken up as their base a two-story building that resembled office space more than military barracks. It was struck by a double car-bombing last year, so the belts of security around it had expanded. American soldiers climbed the towers around the base right away, keeping guard the whole time they were there.

Among the battalion’s soldiers was Sergeant Jawed, a six-year veteran of the Afghan Army and the oldest son of a brick layer. He left school in 10th grade, faked an ID that bumped his age by two years, and joined the security forces like several other of his relatives. For $200 a month, the army sent him to fight the Taliban.

An undated photo of the shooter, Sergeant Jawed.

He got married, and he and his wife had their first child, a boy, three months ago. Sergeant Jawed had managed a transfer just an hour’s drive from home but, busy with the fighting in Shirzad, had not been able to go home to meet him yet.

By dusk that day, the work of the Afghan commandos and their American Special Forces partners was over. They had met the leaders, gone over operation plans. They walked out of the building, into the compound yard, waiting for their helicopters to take them away. The sun had just gone down.

Sergeant Jawed, his weapon in hand, emerged from the side entrance of the building just after 6 p.m., took a dozen steps toward an Afghan Army vehicle where several other Afghan soldiers were. He aimed the machine gun at the Americans and the Afghan commandos huddled on the other side of a gravel path and began spraying.

The shooting didn’t last more than a few seconds. But an M249 can tear through a 200-round ammunition belt in less than a third of a minute. There were at least 43 bullet holes on the cement wall behind the Americans, most of them at chest height, and eight more on a taller empty oil tanker truck behind the wall.

A guard from one of the towers, unclear whether Afghan or American, fired back, killing Sergeant Jawed and leaving the wall behind him riddled with holes, too. But the confusion and suspicion continued for around 10 hours, until the U.S. Special Forces — with two of them dead and six wounded — could be evacuated. At least one other Afghan soldier was killed, and three wounded.

The first scramble was to find out whether they were facing just one shooter or many. One of the first steps the Special Forces took was to disarm everyone at the base, except for the Afghan commandos accompanying them, and ask them to file out one by one. At first the orders were shouted. Then they were announced over loudspeakers. One Afghan Army soldier who resisted being disarmed was badly beaten and had knife wounds, several officials said.

“I told someone next to me this Trump guy is super serious, what if he tells the planes to bomb us?” said one Afghan security force member holed up inside, speaking on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak publicly. “We put down our weapons and came out. But the whole time, helicopters were flying overhead and we were nervous that they would be striking any moment.”

The Taliban relentlessly pressure Afghan soldiers and police to turn and fight the Americans as invaders. And the insurgents bully the soldiers’ families to force them to switch sides or quit the fight altogether.

At the same time, as U.S. forces have shrunk their presence and interaction with regular Afghan soldiers, American airstrikes have reached record numbers, often pounding areas close to where the soldiers come from and sometimes killing civilians. In an age of social media and Taliban propaganda, the news of those attacks spread quickly, and outrage against the American presence rises.

In the days that followed, Afghan and American officials struggled to establish whether Sergeant Jawed had turned and joined the Taliban. In past insider attacks, the picture often became clear right away: the Taliban would claim responsibility, and the soldier’s phone records and movements would tell the rest of the story.

But no group claimed this attack. Sergeant Jawed’s background check was clean, a security official aware of the developments said. Afghan officials said he did not fit the profile of a Taliban infiltrator, though others have questioned that assumption.

Gula Jan, 70, Sergeant Jawed’s grandfather, disputed claims that anyone in his family had ties to the Taliban, noting the group had once raided his house because several of his relatives were in the Afghan forces. They even detained him once after he could not pay the fine the insurgents demanded of him because several of his relatives served in the Army.

“If my sons had been with the Taliban, then why would the Taliban open fire on my gate, why would they hold me for three months?” Mr. Jan said.

Mr. Jan spoke at his home just after his grandson’s burial. The military had refused to hand over the body for six days. A couple hundred people, many calling him a martyr, showed up at the burial. A large Afghan flag was planted near the headstone.

The silence from the Taliban about Sergeant Jawed’s attack was matched less than a week later by a muted American response to an airstrike that struck a pickup and killed at least eight Afghan civilians who were going to a picnic, local officials said. There was no statement from the U.S. military, which Afghan officials said had carried out the strikes.

The shooting and the airstrike couldn’t have come at a more delicate time — the peace deal with the Taliban had reached Mr. Trump’s desk.

In September, the two sides had nearly reached a deal. But Mr. Trump called off the talks, citing a bombing that killed an American and a NATO soldier.

This time, with progress in the talks seeming so close — a Taliban spokesman confirmed Monday that the insurgents had agreed to the terms and that the signing would happen by month’s end — few are talking much about the violence that is still happening, perhaps unwilling to risk any deal that carried a hope of ending it.

The remains of Sergeants Gutierrez and Rodriguez arrived in the rain late on a Monday night, their coffins met by a somber president and distraught families.

“It was very emotional,” said Senator Rand Paul, Republican of Kentucky, who watched the ceremony at Dover. “I don’t know how you could go through that and be in favor of or blasé about war.”

Mujib Mashal and Zabihullah Ghazi reported from Nangarhar, Afghanistan; Katie Rogers from Dover, Del.; and Thomas Gibbons-Neff from Washington.

from WordPress https://mastcomm.com/event/as-afghan-soldier-kills-2-americans-peace-talks-forge-ahead/

0 notes

Text

Syracuse, New York

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

PBR grand central

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inman Railroad Yard, Atlanta, Georgia

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chicago's Rail Yards in the 1940s (credit Jack Delano)

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Chicago's Rail Yards in the 1940s (credit Jack Delano)

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

mashaling yard

279 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Composition

By Rahnaward Zaryab

Translated from Dari by Dr. S. Wali Ahmadi

From April-June 2000 Issue of Afghan Magazine | Lemar - Aftaab

[caption: "Bright Eyes" Qodrat, an orphan, sets in class. By Massoud Hossaini Kabul, November 12, 2002 ]

I was in the fourth year of elementary school. On one of the first days after classes began, our teacher came in and said, "Boys..."

And then, with his eyes to the ground, he began to walk to the other end of the classroom. He seemed to be counting the slates on the floor. In the meantime, he looked very short. The fact is that our teacher really was a diminutive little man.

Suddenly, he stopped by the wall. He looked up-- as if he had finished counting. His lips moved a few times and he finally spoke.

"For tomorrow, each one of you must write a composition-- about spring," he said.

This came as a surprise to us. Our eyes must have been fixed on the teacher in utter amazement, while we felt our ears ringing. "A composition?" we all wondered, "--about spring?"

The teacher must have perceived our state of shock. So he started explaining what he meant for us to do: "That is, I mean, well-- you know, a composition about spring. Write a composition about spring. That's it. Say what people do, for example, or, rather, what animals do-- in spring, that is-- and the like."

The teacher, assuming that we were all as wise as himself, thought that his explanation was sufficient. But we were still confronted with the question, "A composition about spring."

On my way home after school, I thought of nothing but the "composition" we were supposed to write.

When I got home, I asked my mother, "Do you know what a composition is?"

My mother looked at me wide-eyed and said, "No, I don't know what it is. Did you learn it today?"

"I didn't learn it," I said, "but I have to write one. I have to write a composition."

After lunch, I began to write. I mean, I wrote on the top of the sheet, but couldn't continue. I didn't know what to write. So I thought and thought, yet nothing came to my mind. Finally, I stood by the window and stared outside into the yard.

I saw sparrows on the branches of the tree in our yard. The sparrows looked yellow against the green background of leaves. I saw our hen playing in the dirt in a corner. The hen looked blue to me. A little swallow was making a nest by the log of the roof. The little swallow looked like a kite in the shape of a fish. Then I saw our cat, who hated the sun and had taken refuge in the shadow of the wall. The cat looked green to me.

I returned to my pad of paper. Again, I couldn't write a thing. Depressed and really sad, I went out of the house and sat by the wall outside in the alley. I thought.

Then I thought some more. The question was still pushing itself to the walls of my brain "--a composition about spring?"

As I was thinking, I saw our neighbor leaving his house. He was a lean man, and tall. My father used to tell us that this neighbor was a poet. When he saw me, he came to me.

"Why are you sad?" he asked.

"Our teacher has asked us to write a composition," I replied, "--about spring."

"And you can't do it, can you?" he asked.

"No," I said.

Our neighbor began to laugh. He took my arm. He looked up towards the sky and with his finger drew a large half-circle in the air.

"Look around you," he said. "Whatever you see, just write it down. This will be a composition about spring."

Suddenly, everything began to clear up in my mind. "I see!" I cried out with joy. Then I ran back home in a hurry. I stood by the window. Everything looked just like before I had left. My mother was sitting by the tree and was cleaning the rice she wanted to cook later.

I took the pen and wrote the title, "A Composition about Spring."

Then I wrote: "In spring, yellow sparrows play on the branches of trees. The blue hen plays in the dirt. The little swallow, which looks like a kite in the shape of a fish, makes a nest. The green cat hates the sun, so he sleeps by the shadow of the wall. My mother sits by the tree and cleans the rice. In spring the sky is clear. The bees fly all over. And schoolboys write compositions about spring." I couldn't write anymore, but I was quite happy with what I had.

The next day, the teacher was going over our compositions in class. My turn came. The teacher read what I had written. He then stared at me curiously for a moment. My heart was beating fast. The teacher gestured to me to approach his desk. I did.

He looked at me with a great degree of surprise and said, "Tell your Dad to take you to a doctor of some sort."

"Why, sir," I asked.

"Your eyes don't seem to be working right," he replied.

"They are quite all right sir," I said.

"Well, then you should know that a sparrow is not yellow, a hen is not blue, and no cat is evergreen. None at all. Understand?" he said.

"Yes," I answered.

The teacher handed me the paper and said, "Now go!"

I looked at the paper and saw a big red X. I felt that my eyes were full of tears. The X looked like two bloody swords.

- - -

Notes

This translated short story was first published on the Afghan journal CRITIQUE & VISION. Permission for re-publication was granted by CRITIQUE & VISION.

About Rahnaward Zaryab

Rahnaward Zaryab is an Afghan novelist, short story writer, journalist, and literary critic/scholar. He was born in 1944 in the Rika Khana neighborhood of Kabul, Afghanistan.

Further Reading:

Celebrated Afghan Writer Recalls Kabul Of Decades Ago

NPR Audio

Writer Retreats to a Kabul That Lives Only in His Memories and Books

New York Times, By Mujib Mashal

0 notes

Text

After Afghan Soldier Kills 2 Americans, Trump Approves Taliban Deal

NANGARHAR, Afghanistan — President Trump stood in a misty drizzle at Dover Air Force Base as the remains of America’s latest two casualties in the long war in Afghanistan arrived home.

The somber silence was shattered by anguished cries from the young widow of Sgt. First Class Javier J. Gutierrez, who sprinted toward the plane as the metal cases holding her husband’s body and that of Sgt. First Class Antonio R. Rodriguez were being pulled out. “No!” she screamed, calling out his name over and over.

Just hours before that brief ceremony on Feb. 10, President Trump had made a momentous decision, giving his diplomats a green light for a peace deal with the Taliban that would lead to an American troop withdrawal and, possibly, the beginning of the end of the United States’ longest war.

This was once called “the good war,” “the war of necessity.” When American soldiers invaded Afghanistan in 2001 — driven by the Sept. 11 Qaeda attacks on American soil — and toppled the Taliban’s oppressive government, they were welcomed by large parts of Afghan society.

But since then, the war has become a bleeding stalemate in which even some Afghan soldiers turn their guns on American service members, viewing them as invaders instead of partners. The American sergeants mourned at Dover Air Force Base were killed by an Afghan soldier whose uniform, salary and M249 light machine gun were paid for by the United States.

Of the roughly 3,500 total American and NATO deaths in this war, American officials say, more than 150 have been killed in such “green-on-blue” attacks — assaults so destructive to the American mission that they have their own terminology to describe them. The problem has been so pervasive that soldiers are assigned to guard their American comrades who mix with Afghan forces. They have a special name, too: Guardian Angels.

When the war began, in the autumn of 2001, Sergeant Gutierrez and Sergeant Rodriguez were just 8. Sergeant Jawed, the Afghan Army soldier with a single name who would become their killer, was a toddler. By the time their paths crossed nearly two decades later in a dusty, eastern Afghan village, all three men had become old hands at war.

The army’s Seventh Special Forces Group that the two sergeants belonged to had been in Afghanistan just a few weeks. But Sergeant Gutierrez, of San Antonio, Texas, and Sergeant Rodriguez, of Las Cruces, New Mexico, had joined in 2009. Sergeant Gutierrez, a father of four, deployed to Iraq as an infantryman before heading to Afghanistan as a Green Beret. Sergeant Rodriguez had completed 10 tours in Afghanistan, first as an Army Ranger and later with the Special Forces.

Their Special Forces team was back in Afghanistan just as peace talks were reaching a peak again, along with efforts to hold the line against the Taliban in the field and pressure them to stay at the negotiating table.

In Shirzad district, in the eastern province of Nangarhar, the Afghan Army had pushed back the Taliban. But the operations were stuck. So on Feb. 8, a group of Afghan commandos accompanied by the Green Berets arrived early in the morning in helicopters to see if they could help, according to interviews with more than a dozen Afghan and American officials.

The Afghan Army battalion had taken up as their base a two-story building that resembled office space more than military barracks. It was struck by a double car-bombing last year, so the belts of security around it had expanded. American soldiers climbed the towers around the base right away, keeping guard the whole time they were there.

Among the battalion’s soldiers was Sergeant Jawed, a six-year veteran of the Afghan Army and the oldest son of a brick layer. He left school in 10th grade, faked an ID that bumped his age by two years, and joined the security forces like several other of his relatives. For $200 a month, the army sent him to fight the Taliban.

An undated photo of the shooter, Sergeant Jawed.

He got married, and he and his wife had their first child, a boy, three months ago. Sergeant Jawed had managed a transfer just an hour’s drive from home but, busy with the fighting in Shirzad, had not been able to go home to meet him yet.

By dusk that day, the work of the Afghan commandos and their American Special Forces partners was over. They had met the leaders, gone over operation plans. They walked out of the building, into the compound yard, waiting for their helicopters to take them away. The sun had just gone down.

Sergeant Jawed, his weapon in hand, emerged from the side entrance of the building just after 6 p.m., took a dozen steps toward an Afghan Army vehicle where several other Afghan soldiers were. He aimed the machine gun at the Americans and the Afghan commandos huddled on the other side of a gravel path and began spraying.

The shooting didn’t last more than a few seconds. But an M249 can tear through a 200-round ammunition belt in less than a third of a minute. There were at least 43 bullet holes on the cement wall behind the Americans, most of them at chest height, and eight more on a taller empty oil tanker behind the wall.

A guard from one of the towers, unclear whether Afghan or American, fired back, killing Sergeant Jawed and leaving the wall behind him riddled with holes, too. But the confusion and suspicion continued for around 10 hours, until the U.S. Special Forces — with at least two of them dead and six wounded — could be evacuated. At least one other Afghan soldier was killed, and three wounded.

The first scramble was to find out whether they were facing just one shooter or many. One of the first steps the Special Forces took was to disarm everyone at the base, except for the Afghan commandos accompanying them, and ask them to file out one by one. At first the orders were shouted. Then they were announced over loudspeakers. One Afghan Army soldier who resisted being disarmed was badly beaten and had knife wounds, several officials said.

“I told someone next to me this Trump guy is super serious, what if he tells the planes to bomb us?” said one Afghan security force member holed up inside, speaking on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak publicly. “We put down our weapons and came out. But the whole time, helicopters were flying overhead and we were nervous that they would be striking any moment.”

The Taliban relentlessly pressure Afghan soldiers and police to turn and fight the Americans as invaders. And the insurgents bully the soldiers’ families to force them to switch sides or quit the fight altogether.

At the same time, as U.S. forces have shrunk their presence and interaction with regular Afghan soldiers, American airstrikes have reached record numbers, often pounding areas close to where the soldiers come from and sometimes killing civilians. In an age of social media and Taliban propaganda, the news of those attacks spread quickly, and outrage against the American presence rises.

In the days that followed, Afghan and American officials struggled to establish whether Sergeant Jawed had turned and joined the Taliban. In past insider attacks, the picture often became clear right away: the Taliban would claim responsibility, and the soldier’s phone records and movements would tell the rest of the story.

But no group claimed this attack. Sergeant Jawed’s background check was clean, a security official aware of the developments said. Afghan officials said he did not fit the profile of a Taliban infiltrator, though others have questioned that assumption.

Gula Jan, 70, Sergeant Jawed’s grandfather, disputed claims that anyone in his family had ties to the Taliban, noting the group had once raided his house because several of his relatives were in the Afghan forces. They even detained him once after he could not pay the fine the insurgents demanded of him because several of his relatives served in the Army.

“If my sons had been with the Taliban, then why would the Taliban open fire on my gate, why would they hold me for three months?” Mr. Jan said.

Mr. Jan spoke at his home just after his grandson’s burial. The military had refused to hand over the body for six days. A couple hundred people, many calling him a martyr, showed up at the burial. A large Afghan flag was planted near the headstone.

The silence from the Taliban about Sergeant Jawed’s attack was matched less than a week later by a muted American response to an airstrike that struck a pickup and killed at least eight Afghan civilians who were going to a picnic, local officials said. There was no statement from the U.S. military, which Afghan officials said had carried out the strikes.

The shooting and the airstrike couldn’t have come at a more delicate time — the peace deal with Taliban resumed had reached Mr. Trump’s desk.

In September, the two sides had nearly reached a deal. But Mr. Trump called off the talks, citing a bombing that killed an American and a NATO soldier.

This time, with progress in the talks seeming so close — a Taliban spokesman confirmed Monday that the insurgents had agreed to the terms and that the signing would happen by month’s end — few are talking much about the violence that is still happening, perhaps unwilling to risk any deal that carried a hope of ending it.

The remains of Sergeants Gutierrez and Rodriguez arrived in the rain late on a Monday night, their coffins met by a somber president and distraught families.

“It was very emotional,” said Senator Rand Paul, Republican of Kentucky, who watched the ceremony at Dover. “I don’t know how you could go through that and be in favor of or blasé about war.”

Mujib Mashal and Zabihullah Ghazi reported from Nangarhar, Afghanistan; Katie Rogers from Dover, Del.; and Thomas Gibbons-Neff from Washington.

from WordPress https://mastcomm.com/event/after-afghan-soldier-kills-2-americans-trump-approves-taliban-deal/

0 notes

Photo

Union Pacific freight rail yard, North Platte, Nebraska - largest in the United States -Bailey Yard aerial 1996

#Union Pacific#freight#rails#mashalling yard#North Platte#Nebraska#railroad#infrastructure#Baily Yard#UP#train#track

131 notes

·

View notes