#like his writing should have become obscure at the same level of his contemporaries

Text

the fact that shakespeare was a playwright is sometimes so funny to me. just the concept of the "greatest writer of the English language" being a random 450-year-old entertainer, a 16th cent pop cultural sensation (thanks in large part to puns & dirty jokes & verbiage & a long-running appeal to commoners). and his work was made to be watched not read, but in the classroom teachers just hand us his scripts and say "that's literature"

just...imagine it's 2450 A.D. and English Lit students are regularly going into 100k debt writing postdoc theses on The Simpsons screenplays. the original animation hasn't even been preserved, it's literally just scripts and the occasional SDH subtitles.txt. they've been republished more times than the Bible

#due to the Great Data Decay academics write viciously argumentative articles on which episodes aired in what order#at conferences professors have known to engage in physically violent altercations whilst debating the air date number of household viewers#90% of the couch gags have been lost and there is a billion dollar trade in counterfeit “lost copies”#serious note: i'll be honest i always assumed it was english imperialism that made shakespeare so inescapable in the 19th/20th cent#like his writing should have become obscure at the same level of his contemporaries#but british imperialists needed an ENGLISH LANGUAGE (and BRITISH) writer to venerate#and shakespeare wrote so many damn things that there was a humongous body of work just sitting there waiting to be culturally exploited...#i know it didn't happen like this but i imagine a English Parliament House Committee Member For The Education Of The Masses or something#cartoonishly stumbling over a dusty cobwebbed crate labelled the Complete Works of Shakespeare#and going 'Eureka! this shall make excellent propoganda for fabricating a national identity in a time of great social unrest.#it will be a cornerstone of our elitist educational institutions for centuries to come! long live our decaying empire!'#'what good fortune that this used to be accessible and entertaining to mainstream illiterate audience members...#..but now we can strip that away and make it a difficult & alienating foundation of a Classical Education! just like the latin language :)'#anyway maybe there's no such thing as the 'greatest writer of x language' in ANY language?#maybe there are just different styles and yes levels of expertise and skill but also a high degree of subjectivity#and variance in the way that we as individuals and members of different cultures/time periods experience any work of media#and that's okay! and should be acknowledged!!! and allow us to give ourselves permission to broaden our horizons#and explore the stories of marginalized/underappreciated creators#instead of worshiping the List of Top 10 Best (aka Most Famous) Whatevers Of All Time/A Certain Time Period#anyways things are famous for a reason and that reason has little to do with innate “value”#and much more to do with how it plays into the interests of powerful institutions motivated to influence our shared cultural narratives#so i'm not saying 'stop teaching shakespeare'. but like...maybe classrooms should stop using it as busy work that (by accident or designs)#happens to alienate a large number of students who could otherwise be engaging critically with works that feel more relevant to their world#(by merit of not being 4 centuries old or lacking necessary historical context or requiring untaught translation skills)#and yeah...MAYBE our educational institutions could spend less time/money on shakespeare critical analysis and more on...#...any of thousands of underfunded areas of literary research i literally (pun!) don't know where to begin#oh and p.s. the modern publishing world is in shambles and it would be neat if schoolwork could include modern works?#beautiful complicated socially relevant works of literature are published every year. it's not just the 'classics' that have value#and actually modern publications are probably an easier way for students to learn the basics. since lesson plans don't have to include the#important historical/cultural context many teens need for 20+ year old media (which is older than their entire lived experience fyi)

23K notes

·

View notes

Text

New Post has been published on Austen Marriage

New Post has been published on http://austenmarriage.com/fanny-burney-writer-of-her-time/

Fanny Burney: Writer of Her Time

Fanny Burney was the female writer before and during Jane Austen’s life. Both in popularity and literary regard, she stood astride the Regency era as the Colossus stood astride the harbor of Rhodes. She published her first novel, Evelina, when Jane Austen was three years old, hit her publishing peak as Jane was beginning her serious writing, and continued to live and work for another two decades after Austen’s death.

To ensure the proper level of respect, some editors insist that we call her “Frances” rather than “Fanny,” the name she used all her life. Evidently, no one will take her seriously as Fanny but Frances will garner immediate intellectual respect. You’d think her complex writing style, modeled on Dr. Johnson, would be enough for anyone to take Burney seriously. But, here, we digress. …

Austen called Burney, who married a French officer to become Madame D’Arblay, “the very best of the English novelists.” In tracking Jane’s surviving correspondence, we can see her tracking Burney’s career. At the age of twenty, Jane subscribed to the purchase of Burney’s third novel, Camilla.

Two months after its publication in July 1796, Austen references Camilla in three successive letters, including the comment that an acquaintance named Miss Fletcher had two positive traits, “she likes Camilla & drinks no cream in her Tea.” Camilla is mentioned in the discussion of novels in Northanger Abbey. Jane’s annotated copy of Camilla is now in the Library of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

More interesting is a possible indirect but personal connection between the Austens and the D’Arblays. A relative, who likely encouraged the Austens to subscribe to Burney’s novel, was Mrs. Cassandra Cooke. She was first cousin to, and a contemporary of, Jane’s mother. The Cookes lived across the road from Burney and her husband for four years and nearby for several more.

Though the two authors never met, Jocelyn Harris writes in an article that Mrs. Cooke was probably a “direct source of information” about Burney to Austen. In her book Satire, Celebrity, and Politics in Jane Austen, Harris also finds a number of connections between scenes and characters in Austen’s fiction and Burney’s novels and life. Harris proposes that Mrs. Cooke may have been the source for the biographical anecdotes about Burney.

In addition to her novels, Burney wrote plays, most of which went unproduced, and was active at court. From 1786 to 1791 she was “Second Keeper of the Robes” to Queen Charlotte, and she dedicated Camilla to her. During the Napoleonic wars she was trapped for a decade in France. Though her husband was a military man and patriotic Frenchman, the couple detested the violence of the French Revolution and the dictator that followed. She was able to slip out of France when her son was a teenager to keep him from being conscripted into Napoleon’s army.

When Napoleon returned from exile in Elba to reclaim his throne, this time her husband fought against him on the side of the allies and was wounded in battle, before Waterloo ended Napoleon’s career a final time. After the war, the D’Arblays settled in Bath near relatives. Many French emigres had settled there during the war.

Two hundred years later, Burney’s position as Literary Superstar and that of Jane the Obscure has reversed. Burney is still read, and The Burney Society exists to promote her life and works. Yet most of the interest today relates to her diaries and journals, which show us the private thoughts of a sensitive, articulate woman about her long and eventful life. They record what it was like for an intelligent, vivacious, politically aware woman of the age. The also record her personal travails, including her description of undergoing a mastectomy in France—without anesthesia.

Burney began her diaries as a teenager. In an early entry, she tells of an earnest but not very pleasant fellow who fell for her on their first meeting. She asks her family how to get him to leave her alone. They instead encourage another visit. Burney writes in her diary something right out of (write out of?) Austen: that she “had rather a thousand Times die an old maid, than be married, except from affection.”

Today, few would put Burney in the same class as Austen as a novelist. Many Burney characters are extreme, her plots at times involve wild coincidences, and her language is enormously complex. What follows is a simple but representative example in the difference of style. The first is Austen’s dedication to the Prince Regent at the beginning of Emma. The next is Burney’s dedication to Queen Charlotte at the beginning of Camilla.

Austen’s, printed in capital letters and in large type to fill the page:

“To his Royal Highness the Prince Regent, this work is, by his Royal Highness’s permission, most respectfully dedicated, by his Royal Highness’s dutiful and obedient humble servant.”

Burney’s, set in type a little larger than normal, addresses the queen directly:

“THAT Goodness inspires a confidence, which, by divesting respect of terror, excites attachment to Greatness, the presentation of this little Work, to Your Majesty must truly, however humbly, evince; and though a public manifestation of duty and regard from an obscure Individual may betray a proud ambition, it is, I trust, but a venial—I am sure it is a natural one. In those to whom Your Majesty is known but by exaltation of Rank, it may raise, perhaps, some surprise, that scenes, characters, and incidents, which have reference only to common life, should be brought into so august a presence; but the inhabitant of a retired cottage, who there receives the benign permission which at Your Majesty’s feet casts this humble offering, bears in mind recollections which must live there while ‘memory holds its seat,’ of a benevolence withheld from no condition, and delighting in all ways to speed the progress of Morality, through whatever channel it could flow, to whatever port it might steer. I blush at the inference I seem here to leave open of annexing undue importance to a production of apparently so light a kind yet if my hope, my view—however fallacious they may eventually prove, extended not beyond whiling away an idle hour, should I dare seek such patronage?”

Austen was no fan of the Prince Regent, and her publisher probably prodded her into a sufficiently proper flourish. Yet even doubled, her dedication would barely run 50 words. Burney’s dedication runs 216 words—and the excerpt does not include all of it.

This gushing pipe of words is not just an instance of royal flattery. The entire 900-page novel strains under the load of such verbiage. Burney’s first and most successful novel, Evelina, written in the epistolary style, was a contrast. The letters by Evelina are as sharp and funny as anything Elizabeth Bennet ever said. Everyone else, however, writes in a ponderous style that came to dominate Burney’s third-person novels. Wanting to be taken seriously, Burney followed the “serious” style that “real literature” of the eighteenth century required. She was a writer of her time.

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

#18th century literature#Bath#Burney's journals#Fanny Burney#Frances Burney#Jane Austen#Napoleonic war#Regency era

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

BOHREN & DER CLUB OF GORE

My Bloody Quarantine part 1

The last six months have been pretty shit, hey? It looks like there is no future anymore... global warming, COVID-19, Australia on fire, wars... shall I go on?

ANYWAY, we are not here to talk about a stupid government led by a buffoon with a mop in his head (ops!) but to praise one of the bands who kept me company during this bloody quarantine of mine: BOHREN & DER CLUB OF GORE. This German act, in fact, hung out with me during the several nights of insomnia, which, trust me, were devastating, loooooong and cold. Cigarettes after cigarettes, wine after wine, I thoroughly enjoyed the discography of the quartet and I thought it was time to write something about them.

Because of the slow-moving and nocturnal nature of their music, a doom jazz plenty of end-of-the-world ballads, or, in their words "unholy ambient mixture of slow jazz ballads, Black Sabbath doom and down-tuned Autopsy sounds", I happily matched their records to these apocalyptic months. Just like a dark noir by Leo Malet, or a Terry Gilliam dystopian movie, Bohren & Der Club of Gore managed to convey, over the last 25 years, a deep sense of ethical abandonment and claustrophobic imprisonment. There is no future in the music of the German band, no escape from reality, which is doomed and looped into an endless limbo. A not long time ago - which now seems AGES ago, to be honest - I went to the White Cube for the latest Kiefer’s exhibition. I believe that the combination of BCG music and Kiefer’s artworks pretty well.

Over the last months, while listening to them, between a Medoc and a Nebbiolo, I was picturing the band in a smoky “bar at the end of the world”, channelling some kind of Tom Hillenbrant’s dystopian political setting or a Lynde Mallison’s grey cold painting. The best description, though, comes from the band website: “Dear friends of nighttime drives, remote bridges to nowhere and empty multi-storey car parks”. Club Silencio state of mind, indeed.

youtube

The ensemble has constantly been releasing high-quality records since 1994, with the first doom jazz album called MOTEL GORE - albeit the first release was a 1992 cassette filled with post-hardcore noise published under the name of Langspielkassette. MOTEL GORE is, as someone brilliantly described it “audio pointillism”. I think this similitude is accurate: the band did draw tiny dots of obscure, eerie, music on canvases of sound. “Die Fulci Nummer” drives me mad, with its spectral adagio: it’s so good it would’ve been great in the Fulci’s masterpiece Non si Sevizia un Paperino. “Cairo Keller” is charming and evocative, reminding me of a possible soundtrack for Lovecraft The Nameless City. Extra points for the brilliant reference of the cover.

youtube

in 1997 BCG published MIDNIGHT RADIO, two hours of lynchian-LA-night-driving-without-a-destination soundtrack. if it is true that its predecessor "Gore Motel" is more song-oriented, and therefore a lot easier to listen to - it’s evident that Midnight Radio is more rewarding in its own special way: it’s a journey in the darkest corner of your mind. Yes, because the journeys BCG offers are not only external but often internal. The band has developed over the years a therapeutic dialogue between the listeners and their consciousness. Jungian jazz music anyone? LET’S DEBATE!

By the way, while writing this article, I’ve realised how difficult is to talk about BCG music without quoting several cliches - everyone always ends up referring to the same stuff:” car parks”, “night drive”, “Lynch”. But I have to admit, in this case, it’s definitely true! Listening to BCG can really inspire these topics under our skins, as trivial as it sounds! The point is: they do it better than anyone else, they have been doing this forever and they represent the top in this particular sub-genre. With the results of a cinematographic component in their music that leads to these night drive scenarios, post-modern inner state of minds. Bravo!

Let’s go back to Midnight Radio, to BGC and their discography. It’s undeniable that their music fits perfectly in the set of the SLOW TV/MUSIC/YOUTUBE movement. From The Norway train to this 1986 Canadian TV show called “NIGHT WALK” (which, by the way, looks freaking awesome), from Andy Warhol’ “SLEEP” to Kiarostami or Tarkovsky cinema, the slow movement has left an imprint to contemporary culture. Arguably, BGC, with their long holistic records, is part of the movement. Calming the listeners and bringing them into a meditative state of mind, without being mindfulness - luckily. The point is: BCG makes you think about yourselves, finding out that you are someone you should be scared of! Know yourself, fear yourself!

youtube

All that Jazz came in 2000 with the thrilling “SUNSET MISSION”, thanks to the help of saxophonist Christoph Clöser. In this record the band opened up the sound, literally letting some fresh air to enter their music, easing the claustrophobic moods of the previous albums. A hint of lounge-ness came in, due to the mellow, yet sophisticated, sax of Mr Clöser. It is still quintessential BCG, with the nihilism of the band raising up form the bass. Slow, reiterated bass lines are running through the record, giving to Sunset Mission a gloomy, hypnotic cadence. The liner notes include a quote from Matt Wagner's Grendel comic book, which reads: "Alone in the comforting darkness the creature waits. As confusion reigns on this hellish stage, the deafening grind of machinery, the odious clot of chemical waste. Still, the trail of his ultimate prey leads through this steely maze to these, the addled offspring of the modern world.

According to many people, 2002 ‘BLACK EARTH” is BCG masterpiece. I don’t know yet, as I REALLY like them all. What I can say is that Black Earth sounds a lot more accessible, with an even more developed sense of ‘lounge-ness’ which was not so evident in the previous records.

Blach Earth is a good record. Perhaps the trick here is the balanced tempo of the saxophone. Perfectly played within the songs at the right time, Christoph Clöser’ sax conveys an open jazzy sound. One of my favourite directors ever is Jean-Pierre Melville, his movies are everything I like in term of style and plot. Noir a là Dashiell Hammett, but French and without hope - give me more of this, Hollywood, please! Enough of fucking Marvel heroes, give me noir hard-boiled movies!

Black Earth could have easily been the perfect great soundtrack for Mr Melville’s movies - especially, IHMO, Bob le flambeur. Think about it: a french man, with a cigarette in his mouth, gambling his life for a young woman, in a dirty Marseille, with the BCG slow tempo doomed jazz. yasss please, give me more. Or a glacial Alain Delon killing his lover for money.

Black Earth was followed up, in 2005, by “GEISTERFAUST”, which is considered a slower than ever version of the former album. In Ghost Fist (this is the translation) Bohren & Der Club of Gore has stripped down its sound to the bone, becoming more gentle and less aggressive without any compromise. 5 songs only, named after the 5 fingers of the hand, for an hour of dark jazz. Again, excellent quality.

youtube

I have been buying BCG on CD, I think this music on vinyl does not sound perfect UNLESS you have an extremely high-quality sound system, Like some classical music issue, where you need to hear the pianissimo of the piano and single notes, BCG music deserves a very clean medium, I would say CD is the best.

youtube

Jazz de nuit again on their seventh album “DOLORES” published in 2008. This record is pure Badalamenti, pure Lynch in the night. Within the ten songs of Dolores, the core idea of slow-music is even more highlighted, with no guitars at all on the whole album and a sedated keyboard-based mood.

In 2009 the band released a 10 minute EP called “MITLEID LADY”. it is strange, because, albeit recorded just after Dolores, it sounds way more gloomy and somehow different. It is BCG but has another level of sophistication compared to the previous record. This step further in the direction of stylistic accuracy is confirmed two years after, in 2011, with another EP, this one named “BEILEID”. The cover of the record is a reference to the famous Edward Gorey, or at least I believe.

The record includes the cover of "Catch My Heart" by German heavy metal band Warlock, with vocals from Mike Patton. I believe this is the only song with a singer in the entire catalogue of the band. Beileid is a cinematic mood-changer composed of pained saxophone solos, and ghostly string sections, an album that will sweep your mind away into dreamland. A must-have IHMO.

In 2013 the ensemble released “PIANO NIGHTS” probably the warmest record of the band. The Piano obviously helps a lot in making the sound softer and brighter - candle lighted rigorously. A German Gothic feast, with a touch of Teutonic expressionism - who remembers the movie The Hands Of Orlac. BCG should definitely play the soundtracks of this movie. A twisted, dark, thriller with Gothic and expressionist elements. After many years, the band introduces the

Finally, in 2020, the band published “PATCHOULI BLUE”. A pristine, unique, summa of their work, which manages to sound similar to other releases of the band, yet unique, with something different, like a small accent. 50s noir glam, Badalamenti, German Gothic, Slow-Movement philosophy are all elements we can find in this record, but there is something else: a hint of electronic, which can possibly open new territories to the band. I am curious to see if they will become a techno ambient act in the like of Gas (joking).

Aristotle once said that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. I guess this is the whole point in BCG’s music. The synergy the band has been consistently showing over the last 3 decades, and the constant refinement of their own skills.

VIVA BOHREN!

#bohren#bohren & der club of gore#gothic#german#noir#leomalet#melville#alain delone#jazz#ambient#doom jazz#angelo badalamenti#lynch#mulholland drive#gas#grendel#nightmoves#anselm kiefer#expressionism

1 note

·

View note

Text

Dancing with Professors

by Patricia Nelson Limerick

In ordinary life, when a listener cannot understand what someone has said, this is the usual exchange:

Listener: I cannot understand what you are saying.

Speaker: Let me try to say it more clearly.

But in scholarly writing in the late 20th century, other rules apply. This is the implicit exchange:

Reader: I cannot understand what you are saying.

Academic Writer: Too bad. The problem is that you are an unsophisticated and untrained reader. If you were smarter, you would understand me.

The exchange remains implicit, because no one wants to say, "This doesn't make any sense," for fear that the response, "It would, if you were smarter," might actually be true.

While we waste our time fighting over ideological conformity in the scholarly world, horrible writing remains a far more important problem. For all their differences, most right_wing scholars and most left_wing scholars share a common allegiance to a cult of obscurity. Left, right and center all hide behind the idea that unintelligible prose indicates a sophisticated mind. The politically correct and the politically incorrect come together in the violence they commit against the English language.

University presses have certainly filled their quota every year, in dreary monographs, tangled paragraphs and impenetrable sentences. But trade publishers have also violated the trust of innocent and hopeful readers. As a prime example of unprovoked assaults on innocent words, consider the verbal behavior of Allan Bloom in "The Closing of the American Mind," published by a large mainstream press. Here is a sample:

"If openness means to go with the flow,' it is necessarily an accommodation to the present. That present is so closed to doubt about so many things impeding the progress of its principles that unqualified openness to it would mean forgetting the despised alternatives to it, knowledge of which makes us aware of what is doubtful in it."

Is there a reader so full of blind courage as to claim to know what this sentence means? Remember, the book in which this remark appeared was a lamentation over the failings of today's students, a call to arms to return to tradition and standards in education. And yet, in 20 years of paper grading, I do not recall many sentences that asked, so pathetically, to be put out of their misery.

Jump to the opposite side of the political spectrum from Allan Bloom, and literary grace makes no noticeable gains. Contemplate this breathless, indefatigable sentence from the geographer, Allan Pred, and Mr. Pred and Bloom seem, if only in literary style, to be soul mates.

"If what is at stake is an understanding of geographical and historical variations in the sexual division of productive and reproductive labor, of contemporary local and regional variations in female wage labor and women's work outside the formal economy, of on_the_ground variations in the everyday content of women's lives, inside and outside of their families, then it must be recognized that, at some nontrivial level, none of the corporal practices associated with these variations can be severed from spatially and temporally specific linguistic practices, from language that not only enable the conveyance of instructions, commands, role depictions and operating rules, but that also regulate and control, that normalize and spell out the limits of the permissible through the conveyance of disapproval, ridicule and reproach."

In this example, 124 words, along with many ideas, find themselves crammed into one sentence. In their company, one starts to get panicky. "Throw open the windows; bring in the oxygen tanks!" one wants to shout. "These words and ideas are nearly suffocated. Get them air!" And yet the condition of this desperately packed and crowded sentence is a perfectly familiar one to readers of academic writing, readers who have simply learned to suppress the panic.

Everyone knows that today's college students cannot write, but few seem willing to admit that the professors who denounce them are not doing much better. The problem is so blatant that there are signs that the students are catching on. In my American history survey course last semester, I presented a few writing rules that I intended to enforce inflexibly. The students looked more and more peevish; they looked as if they were about to run down the hall, find a telephone, place an urgent call and demand that someone from the A.C.L.U. rush up to campus to sue me for interfering with their First Amendment rights to compose unintelligible, misshapen sentences.

Finally one aggrieved student raised her hand and said, "You are telling us not to write long, dull sentences, but most of our reading is full of long, dull sentences."

As this student was beginning to recognize, when professors undertake to appraise and improve student writing, the blind are leading the blind. It is, in truth, difficult to persuade students to write well when they find so few good examples in their assigned reading.

The current social and judicial context for higher education makes this whole issue pressing. In Colorado, as in most states, the legislators re convinced that the university is neglecting students and wasting state resources on pointless research. Under those circumstances, the miserable writing habits of professors pose a direct and concrete danger to higher education. Rather than going to the state legislature, proudly presenting stacks of the faculty's compelling and engaging publications, you end up hoping that the lawmakers stay out of the library and stay away, especially, from the periodical room, with its piles of academic journals. The habits of academic writers lend powerful support to the impression that research is a waste of the writers' time and of the public's money.

Why do so many professors write bad prose?

Ten years ago, I heard a classics professor say the single most important thing_in my opinion_that anyone has said about professors. "We must remember," he declared, "that professors are the ones nobody wanted to dance with in high school."

This is an insight that lights up the universe_or at least the university. It is a proposition that every entering freshman should be told, and it is certainly a proposition that helps to explain the problem of academic writing. What one sees in professors, repeatedly, is exactly the manner that anyone would adopt after a couple of sad evenings sidelined under the crepe_paper streamers in the gym, sitting on a folding chair while everyone else danced. Dignity, for professors, perches precariously on how well they can convey this message, "I am immersed in some very important thoughts, which unsophisticated people could not even begin to understand. Thus, I would not want to dance, even if one of you unsophisticated people were to ask me."

Think of this, then, the next time you look at an unintelligible academic text. "I would not want the attention of a wide reading audience, even if a wide audience were to ask for me." Isn't that exactly what the pompous and pedantic tone of the classically academic writer conveys?

Professors are often shy, timid and fearful people, and under those circumstances, dull, difficult prose can function as a kind of protective camouflage. When you write typical academic prose, it is nearly impossible to make a strong, clear statement. The benefit here is that no one can attack your position, say you are wrong or even raise questions about the accuracy of what you have said, if they cannot tell what you have said. In those terms, awful, indecipherable prose is its own form of armor, protecting the fragile, sensitive thoughts of timid souls.

The best texts for helping us understand the academic world are, of course, Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. Just as devotees of Carroll would expect, he has provided us with the best analogy for understanding the origin and function of bad academic writing. Tweedledee and Tweedledum have quite a heated argument over a rattle. They become so angry that they decide to fight. But before they fight, they go off to gather various devices of padding and protection: "bolsters, blankets, hearthrugs, tablecloths, dish covers and coal scuttles." Then, with Alice's help in tying and fastening, they transform these household items into armor. Alice is not impressed: " Really, they'll be more like bundles of old clothes than anything else, by the time they're ready!' she said to herself, as she arranged a bolster round the neck of Tweedledee, to keep his head from being cut off,' as he said, Why this precaution?" Because, Tweedledee explains, "it's one of the most serious things that can possibly happen to one in a battle_to get one's head cut off."

Here, in the brothers' anxieties and fears, we have an exact analogy for the problems of academic writing. The next time you look at a classically professorial sentence_long, tangled, obscure, jargonized, polysyllabic_think of Tweedledum and Tweedledee dressed for battle, and see if those timid little thoughts, concealed under layers of clauses and phrases, do not remind you of those agitated but cautious brothers, arrayed in their bolsters, blankets, dish covers and coal scuttles. The motive, too, is similar. Tweedledum and Tweedledee were in terror of being hurt, and so they padded themselves so thoroughly that they could not be hurt; nor, for that matter, could they move. A properly dreary, inert sentence has exactly the same benefit; it protects its writer from sharp disagreement, while it also protects him from movement.

Why choose camouflage and insulation over clarity and directness? Tweedledee, of course, spoke for everyone, academic or not, when he confessed his fear. It is indeed, as he said, "one of the most serious things that can possibly happen to one in a battle_to get one's head cut off." Under those circumstances, logic says: tie the bolster around the neck, and add a protective hearthrug or two. Pack in another qualifying clause or two. Hide behind the passive_voice verb. Preface any assertion with a phrase like "it could be argued" or "a case could be made." Protecting one's neck does seem to be the way to keep one's head from being cut off.

Graduate school implants in many people the belief that there are terrible penalties to be paid for writing clearly, especially writing clearly in ways that challenge established thinking in the field. And yet, in academic warfare (and I speak as a veteran) your head and your neck are rarely in serious danger. You can remove the bolster and the hearthrug. Your opponents will try to whack at you, but they will seldom, if ever, land a blow_in large part because they are themselves so wrapped in protective camouflage and insulation that they lose both mobility and accuracy.

So we have a widespread pattern of professors protecting themselves from injury by wrapping their ideas in dull prose, and yet the danger they try to fend off is not a genuine danger. Express yourself clearly, and it is unlikely that either your head_or, more important, your tenure_will be cut off.

How, then, do we save professors from themselves? Fearful people are not made courageous by scolding; they need to be coaxed and encouraged. But how do we do that, especially when this particular form of fearfulness masks itself as pomposity, aloofness and an assured air of superiority?

Fortunately, we have available the world's most important and illuminating story on the difficulty of persuading people to break out of habits of timidity, caution, and unnecessary fear. I borrow this story from Larry McMurtry, one of my rivals in the interpreting of the American West, though I am putting the story to a use that Mr. McMurtry did not intend.

In a collection of his essays, In a Narrow Grave, Mr. McMurtry wrote about the weird process of watching his book Horsemen Pass By being turned into the movie Hud. He arrived in the Texas Panhandle a week or two after filming had started, and he was particularly anxious to learn how the buzzard scene had gone. In that scene, Paul Newman was supposed to ride up and discover a dead cow, look up at a tree branch lined with buzzards and, in his distress over the loss of the cow, fire his gun at one of the buzzards. At that moment, all of the other buzzards were supposed to fly away into the blue Panhandle sky.

But when Mr. McMurtry asked people how the buzzard scene had gone, all he got, he said, were "stricken looks."

The first problem, it turned out, had to do with the quality of the available local buzzards_who proved to be an excessively scruffy group. So more appealing, more photogenic buzzards had to be flown in from some distance and at considerable expense.

But then came the second problem: how to keep the buzzards sitting on the tree branch until it was time for their cue to fly.

That seemed easy. Wire their feet to the branch, and then, after Paul Newman fires his shot, pull the wire, releasing their feet, thus allowing them to take off.

But, as Mr. McMurtry said in an important and memorable phrase, the film makers had not reckoned with the "mentality of buzzards." With their feet wired, the buzzards did not have enough mobility to fly. But they did have enough mobility to pitch forward.

So that's what they did: with their feet wired, they tried to fly, pitched forward, and hung upside down from the dead branch, with their wings flapping.

I had the good fortune a couple of years ago to meet a woman who had been an extra for this movie, and she added a detail that Mr. McMurtry left out of his essay: namely, the buzzard circulatory system does not work upside down, and so, after a moment or two of flapping, the buzzards passed out.

Twelve buzzards hanging upside down from a tree branch: this was not what Hollywood wanted from the West, but that's what Hollywood had produced.

And then we get to the second stage of buzzard psychology. After six or seven episodes of pitching forward, passing out, being revived, being replaced on the branch and pitching forward again, the buzzards gave up. Now, when you pulled the wire and released their feet, they sat there, saying in clear, nonverbal terms: "We tried that before. It did not work. We are not going to try it again." Now the film makers had to fly in a high_powered animal trainer to restore buzzard self_esteem. It was all a big mess. Larry McMurtry got a wonderful story out of it; and we, in turn, get the best possible parable of the workings of habit and timidity.

How does the parable apply? In any and all disciplines, you go to graduate school to have your feet wired to the branch. There is nothing inherently wrong with that: scholars should have some common ground, share some background assumptions, hold some similar habits of mind. This gives you, quite literally, your footing. And yet, in the process of getting your feet wired, you have some awkward moments, and the intellectual equivalent of pitching forward and hanging upside down. That experience_especially if you do it in a public place like a seminar_provides no pleasure. One or two rounds of that humiliation, and the world begins to seem like a treacherous place. Under those circumstances, it does indeed seem to be the choice of wisdom to sit quietly on the branch, to sit without even the thought of flying, since even the thought might be enough to tilt the balance and set off another round of flapping, fainting and embarrassment.

Yet when scholars get out of graduate school and get Ph.D.'s, and, even more important, when scholars get tenure, the wire is truly pulled. Their feet are free. They can fly whenever and wherever they like. Yet by then the second stage of buzzard psychology has taken hold, and they refuse to fly. The wire is pulled, and yet the buzzards sit there, hunched and grumpy. If they teach in a university with a graduate program, they actively instruct young buzzards in the necessity of keeping their youthful feet on the branch.

This is a very well_established pattern, and it is the ruination of scholarly activity in the modern world. Many professors who teach graduate students think that one of their principal duties is to train students in the conventions of academic writing.

I do not believe that professors enforce a standard of dull writing on graduate students in order to be cruel. They demand dreariness because they think that dreariness is in the students' best interests. Professors believe that a dull writing style is an academic survival skill because they think that is what editors want, both editors of academic journals and editors of university presses. What we have here is a chain of misinformation and misunderstanding, where everyone thinks that the other guy is the one who demands, dull, impersonal prose.

Let me say again what is at stake here: universities and colleges are currently embattled, distrusted by the public and state funding institutions. As distressing as this situation is, it provides the perfect setting and the perfect timing for declaring an end to scholarly publication as a series of guarded conversations between professors.

The redemption of the university, especially in terms of the public's appraisal of the value of research and publication, requires all the writers who have something they want to publish to ask themselves the question: Does this have to be a closed communication, shutting out all but specialists willing to fight their way through the thickest of jargon? Or can this be an open communication, engaging specialists with new information and new thinking, but also offering an invitation to nonspecialists to learn from this study, to grasp its importance, and by extension, to find concrete reasons to see value in the work of the university?

This is a country in need of wisdom, and of clearly reasoned conviction and vision. And that, at the bedrock, is the reason behind this campaign to save professors from themselves and to detoxify academic prose. The context is a bit different, but the statement that Willy Loman made to his sons in Death of a Salesman keeps coming to mind: "The woods are burning boys, the woods are burning." In a society confronted by a faltering economy, racial and ethnic conflicts, and environmental disasters, "the woods are burning," and since we so urgently need everyone's contribution in putting some of these fires out, there is no reason to indulge professorial vanity or timidity.

Ego is, of course, the key obstacle here. As badly as most of them write, professors are nonetheless proud and sensitive writers, resistant in criticism. But even the most desperate cases can be redeemed and persuaded to think of writing as a challenging craft, not as existential trauma. A few years ago, I began to look at carpenters and other artisans as the emotional model for writers. A carpenter, let us say, makes a door for a cabinet. If the door does not hang straight, the carpenter does not say, "I will not change that door; it is an expression of my individuality; who cares if it will not close?" Instead, the carpenter removes the door and works on it until it fits. That attitude, applied to writing, could be our salvation. If we thought more like carpenters, academic writers could find a route out of the trap of ego and vanity. Escaped from that trap, we could simply work on successive drafts until what we have to say is clear.

Colleges and universities are filled with knowledgeable, thoughtful people who have been effectively silenced by an awful writing style, a style with its flaws concealed behind a smokescreen of sophistication and professionalism. A coalition of academic writers, graduate advisers. journal editors, university press editors and trade publishers can seize this moment_and pull the wire. The buzzards can be set free_free to leave that dead tree branch, free to regain to regain their confidence, free to soar.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Moggalithic antiquarian: party political broadcasts from stone circles

By Kenny Brophy (the Urban Prehistorian)

If a poll of Conservative members showed a majority of them were druids, Boris would be straight down to Stonehenge to dance naked for the seasons (Mark Steel, Independent, 28 March 2019)

Stanton Drew’s stone circles may not vibrate as wildly in the English consciousness as their easterly cousins at Stonehenge, however, they remain seriously impressive pieces of Neolithic kit. (Weird Walk, The Face 4.001)

Standing

Jacob Rees-Mogg, standing in the General Election, is standing in front of a standing stone. The parliamentary candidate (and current incumbent) for North East Somerset is asking everyone to vote Conservative in the December 2019 General Election in order to deliver Brexit. He is wearing a double-breasted great coat, almost invisible glasses, and a baby blue rosette the same size as the Nebra Sky Disk.

What was this WTF moment all about?

Was it just an innocent bit of eccentric electioneering fun that just happened to take place with a megalithic backdrop?

Or perhaps the film was an appeal to a certain kind of voter who craves the nostalgic fantasies of the English countryside, windswept standing stones, comical ‘scrumpy and western’ bands like The Wurzels, and Brexit?

Or was this short film altogether something more sinister?

I will ponder awhile on these questions during this post, but the reaction to the video was of even more interest to me.

#BrexitPrehistory

This troubling little video has garnered a good deal of attention. It initially dropped on 2nd December 2019 via Rees-Mogg’s own twitter account (with approximately 369,800 followers on the eve of the General Election ten days later). At the time of writing (13th December 2019) it has been viewed almost three quarter of a million times, and this is only on the Twitter platform.

The film is a particularly egregious example of what I have come to call #BrexitPrehistory (for it was not really about the election, it was about ‘getting Brexit done’) and it indicates the increasingly casual ways that prehistory is being used to make arguments for Brexit by leavers. However, the video also became a focal point for a lot of anti-Brexit (‘remainer’) sentiment, something I would also like to unpick here.

My contention is that we should not be using a prehistoric stone circle to make any kind of points about contemporary political and social challenges although it can be tempting to do so.

Stone circles like Stanton Drew, the one chosen by JRM as his backdrop, are neither leave or remain monuments. Yet, problematically, social media reaction to Rees-Mogg’s piece to camera suggests it might be both.

Petrified

First, let’s consider the video itself. It lasts all of 35 seconds, with a further final five seconds taken up with ‘Get Brexit Done’ and ‘Conservative Party’ branding.

JRM stands in front of one of the standing stones of Stanton Drew. The megalith is partially obscured by his torso and head, and he speaks while performing some half-hearted hand and body gestures. His stiff delivery style mimics the standing stones behind him, his petrified voters, a captive audience.

He narrates the following election message in his curious posh robot voice:

Adge Cutler sang the famous song: 'When the Common Market comes to Stanton Drew.'

I'm here by the standing stones in Stanton Drew, thought to be 4,500 years old, some of the most important stones in this country.

And I want to get the Common Market out of Stanton Drew.

We must get Brexit done. Only the Conservatives can do that - a majority Conservative Government can get out of the European Union and make Brexit happen by 31st January.

Please vote Conservative and get the Common Market out of Stanton Drew.

This little vignette was based on the title of an Adge Cutler song, performed by his band The Wurzels, on the theme of joining the Common Market and the impact it might have on Stanton Drew, the village (not the adjacent prehistoric monument of the same name). Both just happen to be in Rees-Mogg’s North East Somerset constituency for which he was, at the time, standing for re-election, and has since been re-elected with a decreased share of the vote.

The song, 'When the Common Market comes to Stanton Drew', is, depending on your perspective full of outdated, sexist, and racist, sentiments about foreigners and their stereotypical traits. Not to say geographically challenged as to the composition of Europe.

In the evenin' times I s'pose, we'll sip of our vin rose,

Just like they do in the Argentine

And we'll watch they foreign blokes, with their girt big 'ats and cloaks,

Flamingo-in down on the village green.

We'll 'ave to watch our wenches when they dark-eyed lads gets here,

And the local boys'll 'ave to form a queue,

They'll say "Ooh la la, oui oui," instead of "How's bist thee?"

Or as I have also seen it expressed, the song is a rather quaint musing on the exotic effects of becoming more closely integrated with Europe, and is in fact pro-European in sentiment, a parody of the prejudices of rural Little Englanders (oh the irony).

And the Druids Arms won't close till ver' nigh two,

And we'll all drink caviar from a girt big cider jar,

When the Common Market comes to Stanton Drew!

Wikipedia more neutrally notes that in ‘…response to opening up of trade with Europe, Adge suggests what might happen to Somerset culture when Europeans come over’.

This slice of ye olde Englande nostalgia fits well with the JRM brand, apparently au fait with what the working class oiks get up to in their pubs and barns, using deliberately anachronistic terminology, and always wearing at least one item of clothing that belongs to clown.

In reality this is all a bit attention seeking, self-promoting an eccentric film in an election campaign where, by all accounts he had been side-lined by the Conservative Party machine for being too ‘off-message’ even for the Tories. He is, as the Daily Mirror describes him, a ‘disgraced Tory toff’.

Rees-Mogg smacks of a man who likes his stone circles rural, just like WG Hoskins. After all, this was indeed a sylvan spot before all those pesky roads, factories, and voters appeared in the surrounding landscape.

‘Views of Stanton Drew AD 1784’ (source: Dymond 1877)

Note that Rees-Mogg stands in such a position that the camera can only see the rural behind him, and no telegraph polls, roads, or other modern clutter. Another angle would have revealed a different temporal dynamic. He wants you to imagine this photo could have been taken in 1819 or 1919 because his persona is all about a timelessness that stems from a fear of change, of his privilege being undermined by progress.

Memes and mocking

Responses to the film have been largely restricted to social media, with almost no mainstream news commentary. On Twitter there has been a mixed bag of bemused, amused, and angry reactions, as well as some fine memes; a lot of this commentary has come from archaeologists, unsurprisingly.

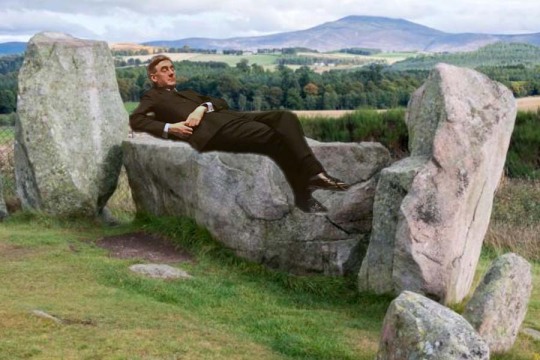

Recumbent Rees-Mogg (Jonathan Last, @johnnythin)

Voting Conservative gets more Stonehenge (me! @urbanprehisto)

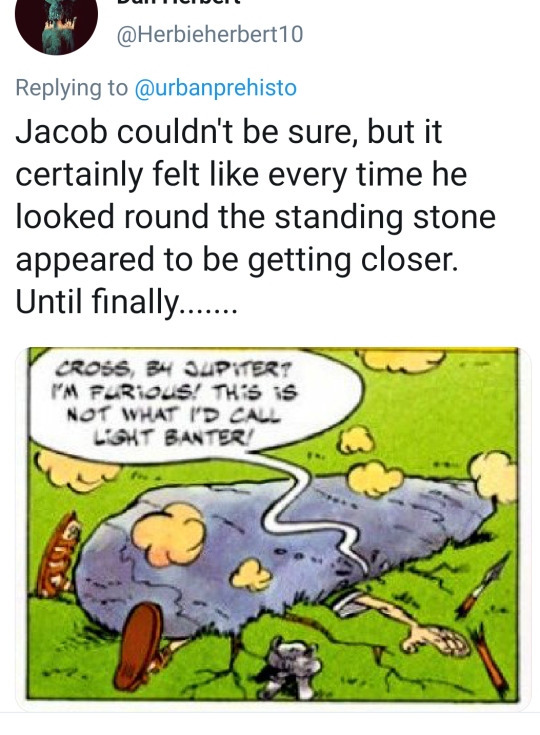

Response by @herbieherbie10 on Twitter

Others had some fun with the fact that the policy and belief system of Rees-Mogg is an anachronism, of the past, although it seems a little unfair to tar the people of the Neolithic with the same brush as this upper class twit.

Response by @snegreid on Twitter

We could be here all day having fun with this video and you can do so by looking at the many, many replies to the original tweet of the video.

‘Built by immigrants’

However, responses did not simply consist of cheap laughs at the expense of a feckless Tory MP. Some suggested that this short film was essentially a dog-whistle nod to the alt-right and far-right viewer of the video. In light of recent media coverage of far-right groups using megaliths in the south of England for rites and ceremonies (covered nicely in this blog post by Howard Williams), the choice of a stone circle could be viewed as at best naïve, or absolutely intentional, depending on your level of cynicism.

Archaeologists such as Cathy Frieman pointed out that it was important we acknowledge the tone of the video, and that it is no laughing matter.

Response by @cjfrieman on Twitter

In this respect should we be more careful about giving such tweets and political propaganda the oxygen of publicity? Certainly, it was interesting to see some responses on Twitter that we should not keep retweeting the original post (either to take the piss or offence) because this helps with the stats for the tweet and increases its visibility. When TV presenter and archaeologist Alice Roberts retweeted this, with a critique (of more below), she fired this little film into the timelines of over 200,000 of her followers. I am in a sense guilty of doing the same thing in this blog post, and it is the case that even mocking memes ensure a person, image, and message spreads across the internet like a virus.

Another theme that emerged in responses to the Rees-Mogg film was the apparent irony of using as a pro-Brexit backdrop a prehistoric monument that was ‘built by immigrants’ and which suggested we had close connections with Europe in prehistory.

Alice Roberts for instance tweeted: ‘How extraordinary that Rees-Mogg chooses to stand in front of a megalithic monument – which speaks so strongly of connections across prehistoric Europe – to make an isolationist statement!’

Charlotte Higgins, chief culture writer of The Guardian (38K followers), tweeted: ‘Get the hell out of my favourite stone circle which, by the way, was built by immigrants’.

Response by @chiggi on Twitter

I don’t want to especially pick on these commentators, as the immigrants trope was suggested by lots of respondents, coming from a place with the best of intentions. And it reminds me of Jeremy Deller’s 2019 street artwork in Glasgow, Built by immigrants, which espouses a similar sentiment.

Jeremy Deller, Stonehenge artwork, Glasgow

Prehistory it seems is a blank canvas upon which we can project whatever we want to, fit into our belief systems, and bounce around within our echo chambers. And while I much prefer a narrative that supports partnership, immigration, and communal labour, over separationist and divisive arguments, I can’t help but feel uneasy about any attempts to use the prehistoric past to support or even justify our own belief systems.

The prehistoric story of stone circles should not be used to score political points.

Arguments that stone circles such as Stonehenge and Stanton Drew were ‘built by immigrants’ and had close connections to Europe and therefore we should retain those relationships today and into the future are, to my mind, as problematic as contrary arguments that, for instance, we have a long tradition of turbulent relationships with Europe, and that Brexit-like schisms are not a new thing.

Reactions to the film suggest leave and remain arguments are both claiming a form of legitimacy deep into prehistory, in the shape of Stanton Drew, which to my mind is both illogical and inappropriate.

Such arguments have become increasingly fuelled by ancient DNA (aDNA) and stable isotope studies that suggest mobility in prehistory was commonplace especially when converted into newspaper headlines and stories. Yet our understanding of prehistory is complex and contested, and contrary views also exist. It is possible for instance to argue that at least some elements of Stanton Drew were constructed in the late Neolithic period (30th to 25th centuries BC), a time of ‘late Neolithic isolation’, even a Neolithic Brexit, according to archaeologists such as Richard Madgwick and Mike Parker Pearson. If we follow this line of argument, Rees-Mogg was correct – Stanton Drew is a leave monument. And, suggestions that stone circles are a common monument type across Europe, thus suggesting cultural connections, smacks of culture-historical thinking. No idea exists in isolation and the Brexitisation of prehistory is becoming tortuous.

The Brexit hypothesis

The use of Stanton Drew as a backdrop and theme for a political announcement about Brexit, and critical reactions to this that I have seen in social media are both symptomatic of what I have previously called the Brexit Hypothesis:

The proposition that any archaeological discovery in Europe can – and probably will – be exploited to argue in support of, or against Brexit (Brophy 2018: 1650).

Our discourse has become so entrenched in Brexit-thinking that we struggle to consider this stone circle without it becoming a synecdoche for our moral, ethical, political, beliefs. In fact, responses should have focused entirely on the wilful and inappropriate appropriation of a prehistoric megalithic enclosure for political ends as some contributors, such as Cathy Frieman, did indeed do.

Are we – the progressives, the liberal left, remainers – in danger of wanting to have our cake and eat it? At this politically dispiriting time, this is understandable.

A polarisation

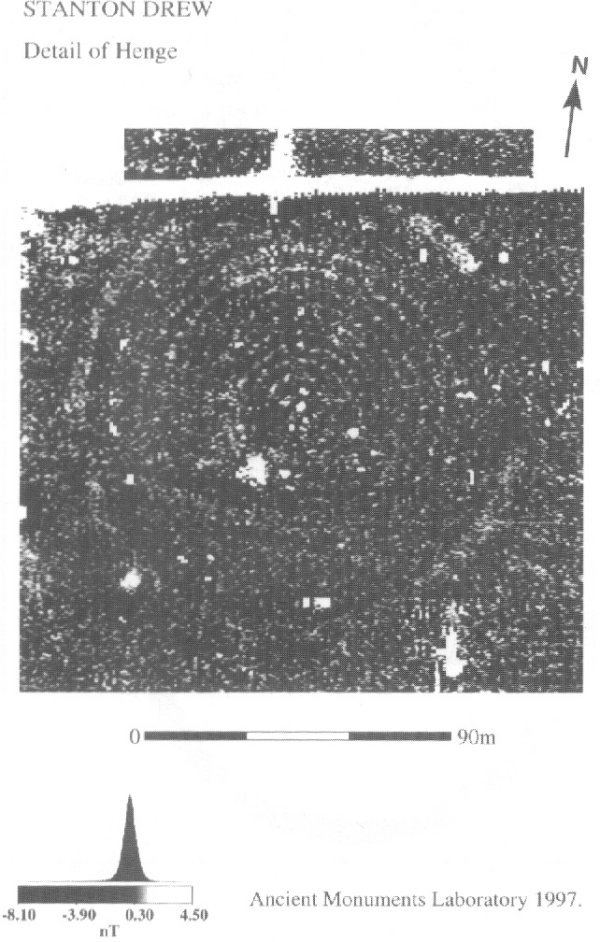

There is always a depth and complexity to such issues, and this is reflected in the invisible, complex archaeology at the Stanton Drew circle JRM chose as his megalithic pulpit. An amazing geophysical survey in 1997 revealed a collection of concentric timber circles within the stone circle, and an external henge ditch. Hundreds of oak posts stood here in the Neolithic period (Davis et al 2004).

Stanton Drew geophysics results (source: PAST)

The visible megalithic Stanton Drew must be understood in the context of the organic invisible Stanton Drew. The visible political posturing must be read within the context of the invisible underlying currents given off that can perhaps be picked up on should receptive equipment be suitably attuned. As with actual, so with metaphorical geophysics: these undercurrents can be positive and negative. Rees-Mogg is attracting and repelling at the same time. That is what populist politicians – and magnetometers – do.

His deliberately divisive message is having the desired polarising effect.

The choice of site, the words, the message, of this short video are very much in the antiquarian tradition.

He is the Moggalithic antiquarian.

JRM the antiquarian, words from Dymond 1877

This is played out through his superficial understanding of the archaeological site, and an inability and unwillingness to interpret outwith his own value system. JRM uses the stone circle to valorise his world view and force that view upon others.

Yet stone circles can and should be kept out of our Brexit battles. They are no more an indicator of what Jonathan Last, in another great response to far-right use of prehistoric monuments, has called, ‘a conservative, nostalgic narrative of a lost rural England’, than they are surviving traces of an ancient utopia of free movement and European cultural cohesion.

Stone circles should be testament to the sophistication of Neolithic people. Stone circles should continue to be a source of wonder, mystery, the otherness of the past as demonstrated in Weird Walks zine #2. Their weird walk route around Stanton Drew, documented in the pages of this zine and The Face, is a wonderful counterpoint to the weird stiffness of the Rees-Mogg polemic. The stones should be hugged, and the stone circle is to be enjoyed, as is the visit to the Druids Arms pub afterwards.

Weird Walks Stanton Drew (source: Weird Walk #2 (2019), 30-1)

Prehistoric sites cannot, and should not, be viewed through a Brexit lens, whether leave or remain.

We need to get back to seeing such ancient monuments through a camera lens and our own eyeballs.

We must take back our wonderful prehistoric monuments from the grasping hands and propaganda machines of opportunistic politicians, and avoid falling into their sinister traps.

***

Works cited:

Brophy, K. 2018. The Brexit hypothesis and prehistory. Antiquity, 92: 1650-58. DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2018.160

David, A 1998 Stanton Drew, PAST 28. (Newsletter of the Prehistoric Society). Available online https://www.ucl.ac.uk/prehistoric/past/past28.html#Stanton

Davis, A. et al 2004 A rival to Stonehenge? Geophysical survey at Stanton Drew, England. Antiquity 78, 341-58. DOI: 10.1017/S0003598X00113006

Dymond, CW The megalithic antiquities at Stanton Drew, Journal of the British Archaeological Association 33: 297-307.

***

Thanks to guest blogger Kenny Brophy. Follow Kenny on Twitter @urbanprehisto.

Read more by Kenny on his own blog, The Urban Prehistorian, and a previous guest post here.

Follow us on Twitter @AlmostArch, and pitch us your guest blog!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 assignment from 1st to 5th march

Bahadur Yaar Jung Quotes From his Speeches

‘‘Most testing or the difficult times in the life of political organisations [freedom struggle] is when seeds of dissent and misunderstandings are sowed amongst them, People considered as close associates are turned into strangers, atmosphere of distrust are rising like storm, Our nest[country] is on fire, the very leaves are fanning the fire who were our trusted allies, These are the testing times of your abilities to discern and think clearly’’.

‘’I am against British [rulers] and yet not against them, As Hindustani [Indian] I am against the imposition of British rule over India, I have the desire to free India, To get rid of their autocratic hold sooner than later, It is my birth right and I take pride in it in a similar way to any free and proud Britisher would take pride in the fact that they are free of German intrusion and force,

Will British tolerate that France or Germany would rule over them, if the answer is No! [Never] Then they should equally respect our desire for freedom as well.’’

Author writing-

Last year we faced the same situation, But, this year he was permitted to give his speech on one condition, that he would write his speech, give one copy of the same to the Residency [British authority] Bahadur Yaar Jung did not agree to the terms and rejected it.

In this regard he has revealed the secrets of many characteristics of humanity, this is a fact when someone gets to enjoy the fruit without making any efforts their potentiality and abilities gets rusted, they loses their self-worth, and dignity, which are vital to for his [identity] as responsible individuals and citizens.

Courage and self-worth are foremost, the habit of inaction or sedentary life effects these qualities the most. The person suffers from inferiority complex……

‘’You must have come crossed the stories and lives of kings and rulers, What kind of treacherous, cruel and heart hearted wolf in sheep clothing [ animal in human form] they can be.

One can witness them in histories of all countries, When provoked would not hesitate to murder their own fathers, gouged the eyes of their beloved children, poisoned their drinks, including their own brothers, nephews, nieces, uncles, aunts, son in laws, none were spared. If their pride is wounded or ego is hurt would ravish the honour of their mothers, daughters and sisters. The short, they would do things which are beyond the imagination. This is found in all countries china, Arabia, India, Iran, Rome, France, Britain, one worse than the other.’’

‘’I have step forward [lead] and unmasked their faces, my task is done, from here begins your task to discern.’’

Field of enquiry- Bahadur Yaar Jung quotes

It is Historical, political, relational, urban, social, identity, commentary, language and text.

Methodologies- Intervene, Translate, observe, Document, Repeat, Depict, illustrate, Abstract, narrate and imagine.

Outcome- Political, Critique, Time [historical] specific, translate, uncanny, and relational.

I was so busy with my side of work, forgot to ask someone to check if my work is upto mark or needs some changes, as I have tried my best to be close to the original as much as possible. I wanted to capture his sound in English. To be equally effective in the 'other' language, and in similar situation as speeches are given with future kept in perspective.

Field of enquiry - Politics of invisibility

Field- Urban, social commentary, realism, psychology, identity, public, relational, language and text.

Methodologies- Interact, imagine, observe, document, duplicate, abstract, construct, miniatuarise/scale and depict.

Outcome – critique, decorative, humour, collections mimetic, political, uncanny, optical and illusionary.

Field of enquiry - Hybridity and gaps within integration

Field of enquiry- Urban, historical, social commentary, cultural, public/private, realism, psychology, identity, and relational.

Methodology – Intervene, interact, imagine, observe, replicate, document, appropriate, construct, deconstruct, abstract, craft and narrate.

Outcome- Celebrate, critique, nostalgic, political, cultural and social commentary.

Questions-

How effectively does each work address your field of enquiry?

My works all start with nothing set as what field they are going to address, initially I look around and browse what topics, issues, pictures, art seems to resonate with me and then I start to expand some research about it, as I want to be engaged with my art pieces for very long time, it has sustain my interest for longer period so that I could really settle down in my field of enquiry.

All three fields of enquiry deals with relational, how people live, their struggles and challenges. We have to collaborate with each other in spirit of tolerance, collaborations and continues flow of dialogue to understand and appreciate each other more.

Is it too obvious or obscure, strength and weaknesses of your work?

Yes, it sits more towards being not too detail, effort has been applied from the beginning of my works that it should have more clarity and sound to my works. Yet more can be done.

As I was exploring the topic of invisibility I should have focused on the blurring of images as well rather than expanding the tiny, small as insignificant, or too small to be noticed.

Dealing with historical personalities one cannot do justice, as the material is limited, my art struggles to expand in this piece of work[ Bahadur yaar jung].

Strength and weakness-

I sort of work in similar field of enquiry and could not break from it, all my pieces share the political, social and relational aspects, Feminist, Artificial, Kitch and many other fields remain unexplored that is my weakness, My strength is that each work shares similar field of inquiry and methodology and sits closely to each other.

Does it open up to new ways of thinking in your field of inquiry or does it merely illustrate the existing knowledge?

The idea always remain that we all struggle to expand and bring a new twist to the art of expression. As there are multiple mediums, and many issues that can be tapped into, We tryTo speak our best to have an individualist mind without fear and with clarity can help in making art which would look new yet somehow familiar as well.

Contemporary art is more contextual, complex and very personal at all levels. It is important to remain in a state of restlessness and somewhat detached from consumerism, being down to earth can help in many ways.

How engaging did you find each approach[ methodology]?

There has been some common features of my three art pieces which allowed the methodology to develop all the three, like construct, imagine, observe, document, abstract, craft to name the few.

Especially the translating piece took lot of effort, reading, re reading, looking up again and again, writing, re writing, thinking, and lots of referring back to dictionary. forming sentences just like the speech, long and free flowing.

Everything had to look effortless, fluid and transparent for the audience to see.

How do the three art works operate together? do they become more interesting

Do they double up or compete with each other?

All the three art works have different field of inquiry, yet they have some of the features common, like political, relation, psychology, identity, urban to name the few.

They look quite interesting as some of the outcomes are not the same. They have many traits which are similar, They do not double up, but sits closely to each other and strengthen each other in the studio space.

There is the element of competing for attention as well

0 notes

Photo

Meg Baird Interview — 2007

Sunday interview! This one was conducted way back when via email. Dear Companion is still great! In fact, most everything Meg Baird does is great -- have you checked out the Heron Oblivion live LP?! Wow. I also hear rumors of an upcoming collab LP with harpist extraordinaire Mary Lattimore.

With her lovely-from-start-to-finish solo debut Dear Companion (Drag City), Meg Baird takes a break from her duties in the Philadelphia psych-folk collective Espers. The apple doesn't fall far from the tree, though. The ten songs here are deeply rooted in traditional song forms (from age-old British Isles ballads to Appalachian laments), as well as the 60s and 70s singer-songwriter era (from Jimmy Webb to New Riders of the Purple Sage). With a few of Baird's own originals mixed in, Dear Companion stands as one of the best all-acoustic records since Gillian Welch's Time (The Revelator). Mostly comprised of Baird's high, pure vocals and intricately picked guitar, the album conjures up the timeless and universal nature of the best folk music. We chatted with Meg about her inspirations, obscure Canadian folksingers and Bob Dylan's amphetamine-fueled ramblings.

Whether it's performed by the Everly Brothers, Bob Dylan, Norma Waterson, Michael Hurley or by you on Dear Companion, "The Cruelty of Barbary Allen" is one of those songs that always stops me in my tracks. What do you think it is about this 500+-year-old song that gives it such a powerful resonance even today? How did you come to record it for the album?

My version came from an amalgamation of Michael Hurley's version from Sweetkorn and another from a Jean Ritchie recording with a totally different melody — these are my two favorites. I learned this one just for Michael actually. About three years ago, he agreed to try and record a few songs for a few days with Espers during a stop on his spring east coast tour — just to see what happened. This was one of his top recommendations to try so of course I learned it just in case.

Perhaps the resonance of this song is a little bit cumulative? For a contemporary listener, if you've made a decision to actually forgo your healthy cynicism for all the maudlin associations genuinely attached to this sort of material, then you are listening with a pretty well primed imagination. The main storyline here is so straight — two young ones eventually killing themselves over a misunderstanding in a lover's quarrel. But the way each scene unfolds gives us all the vantage point to protest "No, don't do it, it should all work out!" just like we would in any horror film or melodrama. It's a very unifying populist pastime to hope that it will all work out, when we know that it won't. This experience can so easily become twisted into pure manipulation, but here it can feel wonderful — like a chance to just experience a feeling in a spectrum of feelings. The colors in this world seem so vibrant, the perception of history so vibrant. You've made these scenes all yourself, and they seem safe from being diminished by the elements.

Listening to Dear Companion (not to mention your work with Espers) I'm reminded of this old quote from Dylan: "What folk music is... is based on myths and the Bible and plague and famine and all kinds of things like that which are nothing but mystery and you can see it in all the songs … All these songs about roses growing out of people's brains and lovers who are really geese and swans that turn into angels … and seven years of this and eight years of that and it's all really something that nobody can touch ... (the songs) are not going to die." What do you think – is this an accurate summing up of the so-called folk tradition, or was Bob just blazing on amphetamines when he said that?

Probably your last theory about amphetamines is true, but aside from that, this is a pretty adept description of mystery in folk song. Although it is a really amped up, exceptionally urgent description, it also seems in keeping with a tone used very commonly at that time. His urgency especially makes sense with the last line, about how "(the songs) are not going to die." Maybe I agree with this very believably passionate depiction of being moved by this music, but perhaps I don't get to share in his blazing confidence in its immortality.

What/who was the album/song/artist that really turned you on to folk music? What made you think: "I want to do something like this."

I'm sure it is a really long, ongoing series of events, but one flash moment like the one you describe, particularly in relation to straight traditional music, happened when I was 19 (reasonably well-versed in the college radio canon of the time) and my sister Laura took me to a Sheila Kay Adams performance. I certainly did not ever think that I could do anything quite like that, but it literally opened up a world of possibilities of what music and performance can do, in addition to helping me see ways around some of the obstacles that can come up around identity hang-ups concerning audience, format and other limitations sometimes imposed by self-flattery. I got a chance to meet her a few years ago and tried to thank her and tell her about this experience I'd had, but all I did was burst into tears like a crazy person. Hopefully she understood something good in my maligned attempt to communicate my extreme appreciation.

The spare, uncluttered sound of Dear Companion really makes it stand out from much of the music being released today. Was making such an austere record your intention going into the recording process? Do you imagine that your subsequent recordings will continue in this vein, or do you have string sections and trumpets and backup singers in your future?

Sparsity and warmth were definitely guiding intensions. I used overdubs to add some imagination to the record and save it from being too literal. By the final mix, I thought it would be fun to think of vocal and guitar overdubs as my only allowed effects or "tricks" For this reason, I got a great kick out of selecting only one brief moment of Space Echo-drenched electric. With the rest of the record being so spare, it was a really enjoyable method to try and emphasize this effect to its maximum.

I don't know yet how I'll record the songs I'm writing for the next record. I'm sure that I will want to try something new, but seeing now just how clearly I totally over-thought the sparsity issue, I guess that new approach could really take any shape.

I'm familiar with a few of the artists whose songs you cover here – Jimmy Webb, New Riders of the Purple Sage – but Fraser & Debolt are completely new to me. What can you tell me about them and this fantastic song you've included, "The Waltze of the Tennis Players"?

I know very little about Daisy Debolt, Allan Fraser or Ian Guenther much other than that they are Canadian and they made this completely amazing record together that a good deal of people seem to truly love. (I think that the "hit" was their knockout version of "Don't Let Me Down") "Waltze" in particular must be one of the most imaginative songs on the subject of courtship that I have ever heard. The whole record is incredibly tender, raw and earthy; seemingly fueled by the same kind of human will and warmth that keeps a person alive through the winter. Despite how outwardly folky this record is, it has always reminds me a great deal of Dead Moon. A really nice, in-depth fan Web site is maintained for Fraser & Debolt.

Tell me a bit about the recording process for Dear Companion. What did your Espers band mate Greg Weeks bring to the proceedings? Were there songs that you attempted but that didn't make the final cut?

I recorded this album on a few long, spare afternoons during the recording of [Espers'] II. My plan was to prepare madly for the taping sessions and get everything on tape in very early takes. I had been playing some of these songs for years, some only for a month, but all of them required a great deal of rehearsal for these sessions.

Greg brought his incredibly adept engineering ears, great gear sensibility and some really gutsy approaches to the recording levels that wound up having a pretty interesting effect over the whole record itself. It was also great to have someone so talented to bounce tracking ideas off of and to double check on my performance quality. We work together all the time, so of course Greg was able to really help me keep to this goal of recording these songs very quickly and comfortably with little fuss or ramp up time.

I dropped the bridge from "Waltze" because the original creates a level of blasting off that I truly couldn't pull off to any good effect. Among other missed selections, my version of Peter Hammill's "(On Tuesdays She Used to Do) Yoga" will just have to remain mine for private enjoyment.

Now that the album is soon to be out in stores, what are your plans? Are you going to play any solo shows? What's next for Meg Baird!?

I have lots of plans, unfortunately none of them so well formulated to tell you anything specific. I have a very busy imagination, perhaps too busy, and Espers is quite busy at the moment as well. Despite all of this, I definitely am trying to arrange some public performances timed near the release in late May.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE: CHARACTERISTICS OF “INTERNET ENGLISH”- PART ONE: THE MEME

We would at first like to more closely observe the widespread phenomenon of the meme. The term was first coined by Richard Dawkins in his book “The Selfish Gene”:

We need a name for the new replicator, a noun that conveys the idea of a unit of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation. 'Mimeme' comes from a suitable Greek root, but I want a monosyllable that sounds a bit like 'gene'. I hope my classicist friends will forgive me if I abbreviate mimeme to meme. If it is any consolation, it could alternatively be thought of as being related to 'memory', or to the French word même. It should be pronounced to rhyme with 'cream'. [DAWKINS, 1976]

While it is highly doubtful that Dawkins intended for this term to become so popular, it is not by definition far from what the famous internet memes are. Nevertheless, it is possible that they are simply called memes due to the French word (not unlikely, given the “relatable” factor that goes into memes), and the above study has simply been connected to it due to its more academic roots.

One way or the other, one could without much effort conclude that a meme is a piece carrying cultural reference, be it old or new. It is oftentimes said that the internet meme is the Web Community’s “inside joke”. Once that thought is given consideration, the definition of a meme as an inside joke makes the most sense of all.

The understanding of memes requires understanding of context, or at least of the fact that this or that piece of culture has acquired this status. Given the internet’s fast-paced world, some memes fall into oblivion fairly quickly, while some remain strong in the internet’s subconscious. Because of that, it is fairly easier to point out which have had a long lasting effect, and are here to stay- at least online.

Interestingly enough, the ephemerons nature of the internet meme has prompted the creation of several website dedicated to keeping track of them, be it widespread or extremely obscure.