#liffey bridges

Text

Night lights as the sun sets and pink sky spreads across the evening Dublin sky.

Seen here, Dublin's Samuel Beckett Bridge partly silhouetted against the bright but darkening sky.

#ireland#vsco#vscocam#irish#photographers on tumblr#photography#travel#dublin#river liffey#samuel beckett bridge#architecture photography#evening sky#sunset

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

EVERYONE PHOTOGRAPHS THIS BRIDGE BUT USUALLY NOT WITH AN 85MM LENS

I could no think of anything new to say about this bridge so I asked Google's BARD AI why do so many people photograph the Halfpenny Bridge

THE HALFPENNY BRIDGE ACROSS THE RIVER LIFFEY

I could no think of anything new to say about this bridge so I asked Google’s BARD AI why do so many people photograph the Halfpenny Bridge and it replied as follows [it made at least one major error]:

There are many reasons why people photograph the Ha’penny Bridge. Here are a few of them:

It is a historic landmark. The bridge was built in 1816 and…

View On WordPress

#Fotonique#FX30#halfpenny bridge#historic#Infomatique#pedestrian bridge#river liffey#Sony#Sony FE 85mm Lens#Tourist Attraction#William Murphy

0 notes

Photo

Iconique #dublinbynight #Dublin #bridge #liffey https://www.instagram.com/p/CjJBI2_jswZ/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Video

Ha'penny Bridge over the River Liffey, Dublin by Jay Galvin

Via Flickr:

Arch bridge, cast iron , wood (deck),Cement (deck), 2015, Total length 43 m (141 ft) Width3.66 m (12.0 ft) Wiki

#Dublin#Ha'penny Bridge#Ireland trip#River Liffey#arch bridge#cast iron#Ireland#geo:state=dublin#camera:make=panasonic#exif:aperture=ƒ / 6.3#geo:city=dublin#camera:model=dc-gx9#exif:model=dc-gx9#geo:lat=53.346130555#geo:location=#exif:focal_length=14 mm#exif:iso_speed=200#exif:make=panasonic#geo:country=ireland#geo:lon=-6.2650472216667#exif:lens=lumix g vario 7-14/f4.0#@JayGalvin#flickr

1 note

·

View note

Photo

#dublin #ireland #liffey #river #docklands #missu #bridge #riverbank #walking #citywalk #sky #clouds (hier: Dublin, Ireland) https://www.instagram.com/p/CfE002xMM1P/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

1 note

·

View note

Text

The young rioter surveyed the scene. A bus and a car blazed on O’Connell Bridge while masked groups marauded across the city centre looting shops, attacking police and shooting fireworks, turning the air acrid.

A police helicopter hovered and officers with shields and batons were assembling at the far end of O’Connell Street but the heart of Dublin, for now, belonged to the young man in a black hoodie who started to dance in the glow of the flames.

Comrades cheered as he punched the air and jigged to a soundtrack of breaking glass, shouts and sirens. He held his arms aloft like Rocky and paused, mesmerised by the mayhem. “Beautiful,” he said. “Fuck-ing beautiful.”

For other people in Ireland and elsewhere who saw images of Thursday’s anarchy it was the night Dublin went mad. For participants it was the night the city came to its senses – that here was an overdue venting of rage, a reckoning.

Ireland, according to this narrative, has opened the floodgates to foreigners with no controls or checks, leaving rapists and murderers to prowl the streets, and no one – not the government, not opposition parties, not the media, not the police – is taking it seriously.

So when social media rumours attributed a horrific stabbing attack on three children and a creche worker to a foreigner – Algerian, Moroccan, Romanian, versions varied – groups descended on Parnell Square, the scene of the crime, and decided to unleash chaos.

“People need to fight for this country,” said Samantha, a 27-year-old mother, as masked youths clashed with police attempting to retake Eden Quay along the River Liffey. “I’m not racist; I don’t mind people coming in if they respect Irish people. But the likes of the toerags coming into this country – they’re not vetted and are causing havoc.”

The unfolding scenes, in contrast, were legitimate havoc, a corrective to a political establishment impervious to previous protests over rising numbers of asylum seekers, said Samantha. “When we do things peacefully we get ignored.” She had left her five-year-old at home without dinner in order to join the revolt, she said. “I’m out here fighting for my country. We shouldn’t have to do this.”

Others echoed the refrain: to make Ireland safe, wreck the capital.

“It’s not right but it had to be done. The government is not listening,” said one man in his 20s, a bystander rather than a looter. “This isn’t against foreigners. We were the first emigrants. Immigrants are driving our buses, cleaning our hospitals – we need them. But they need to be vetted.”

Ireland’s demography has been transformed in recent decades as a booming economy reversed the historical flow of emigration. A fifth of the 5 million people now living in Ireland were born elsewhere. A recent increase in refugees from Ukraine and other countries fuelled a backlash amid concern over a housing shortage and straining public services. The number housed by the state jumped from 7,500 in 2021 to 73,000 in 2022.

Amid the destruction on Thursday night there was some linguistic nuance, with “non-national” usually preferred to “foreigner”, and “unvetted” or “unregulated” preferred to “illegal”, and an aversion to the label “far right”.

There was nothing subtle about the targeting of police. Bottles, bricks, fireworks and other missiles rained down on officers, many of whom lacked helmets and shields. The crowd cornered and attacked isolated officers, leaving several injured. Eleven police vehicles were damaged.

Journalists too were unwelcome and photographers had to conceal cameras. “He’s with the Guardian,” a man in his 60s, holding a tricolour, shouted. Younger, hooded men formed an intimidating cluster. The worst sin was to be with RTÉ, the national broadcaster, or the liberal Irish Times, which were accused of cheering the “replacement” of Irish people by new arrivals.

Many onlookers were appalled. “It’s heartbreaking for Dublin, for Ireland, for Europe,” said Matthew Butler, 28. A 53-year-old postman who gave his name only as John expressed fury. “Just a bunch of scumbags out to wreck Dublin city. The gardaí [police] should have free rein to beat the shit out of them.”

On Friday, Leo Varadkar, the taoiseach, said the rioters had shamed themselves and Ireland. “I want to say to a nation that is unsettled and afraid: this is not who we are – this is not who we want to be – and this is not who we will ever be.” The Garda commissioner, Drew Harris, blamed the disturbances on a “lunatic, hooligan faction driven by far-right ideology”.

The mob had diverse motives. Some belonged to fringe political groups and were veterans of protests against refugee centres. Some were opportunistic gangs that seized the chance to loot sportswear and alcohol. Others came for the spectacle and the chance to post dramatic footage on social media.

All, however, scorned the idea that Ireland is a safe, stable society. The economy is at full employment and the state is flush with tax revenue but their social media feeds depict a country overrun with “non-native” predators such as Jozef Puska, a Slovak man convicted earlier this month of murdering a teacher, Ashling Murphy, in 2022. As the night wore on, an unfounded rumour spread that one of the children in the Parnell Square attack had died.

It did not seem to matter that one of the people who stopped that attack was a Brazilian Deliveroo rider, Caio Benicio, and that Dublin gangs have assaulted numerous South American couriers in recent years.

Chilling threats of assaults against immigrants were made on a WhatsApp group titled “enough is enough”. “Everyone bally [balaclava] up, tool up,” said one man. “Let’s show the fucking media that we’re not a fucking pushover, that no more fucking foreigners are allowed into this poxy country.”

However, the mob targeted property and police rather than foreign and non-white bystanders, who watched in bewilderment.

As police gradually regained control James, a 33-year-old labourer, confronted a phalanx of shields on Burgh Quay, drawing cheers from others who hurled missiles. After being sprayed in the face, James staggered back to Butt Bridge where a Brazilian man, who had experience of being teargassed in his home country, offered recovery tips.

James thanked him but in an interview said “unregulated” arrivals were ruining Ireland. “We’re rammed to the gills with foreigners doing mad shit. You can’t do this to Irish people. I’m getting out of this country, I’m burning rubber. It’s not safe to walk around here.”

Mohammed Gaber, 27, an accountant who moved to Ireland from Sudan and is now an Irish citizen, came into the city centre to check on his sister, Ebba. He lauded his adopted home but worried about what the riot might augur. “Irish people are so welcoming. I’ve never experienced any discrimination. But this is crazy. This is the first time that I feel that there is something big.”

With roads sealed off and smoke pluming over Dublin, Ebba, 33, was blunter. “This is terrifying.” She was not sure of reaching her job as an emergency doctor at a police station.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gilded decoration, bridge over the River Liffey, Dublin, Ireland, 2013.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

PUB CRAWL LOCATION #4: THE BRAZEN HEAD

Established in 1198, the gastrobar has been thoughtfully refurbished to retain the original features that tell the story of their deep history within Dublin city. As the oldest pub in Ireland, they have a colorful history that spans many years. The Brazen Head is located on Bridge Street. This is the area from where the original settlement that was to become Dublin got its name. Beside the pub is the Father Matthew Bridge crosses the river Liffey. It was at this very spot that the original crossing of the river was located. Here reed matting was positioned on the river bed which enabled travelers to cross safely at low tide.

Enjoy endless drinks and mocktails while the live music plays! A band will be there as classic Irish songs that tells a story plays while you have a jameson and ginger ale by the fireside!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in 2001 – The pedestrian Ha’penny Bridge across Dublin’s River Liffey is reopened after a multimillion pound restoration.

Dubliners have been crossing the Ha’Penny Bridge free of charge for over a century now, but they have a long memory. Although it was first named in honour of the Duke of Wellington and later rechristened Liffey Bridge, one of the city’s favourite postcard images turned 205 this year still known universally by the name that trumped the others: Ha’penny Bridge.

A ha’penny was the toll – each way –…

View On WordPress

#1916 Easter Rising#Dublin#Dublin Corporation#Duke of Wellington#Edwin Lutyens#Ha&039;penny Bridge#ha’penny#Ireland#William Butler Yeats#William Walsh

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! do you have a favorite bridge, and if so why?

Based on this question, I have to assume this anon is Hank Green, which is wild.

Yes, I have two favorite bridges. A tie for favorites, if you will.

One is the Golden Gate Bridge because I am from NorCal and The Golden Gate is the best bridge of the four main ones to cross the SF bay. It's also majestic and looks equally good in sun or fog. I've also done a race where I got to run across the Golden Gate, and that has added too my love of it.

My other favorite bridge is Ha'penny Bridge over the Liffey in Dublin. I just love how it looks, epically at night, and I spent a lot of time walking over it. Here's a picture of it with a rainbow.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

SubDublin

A wild hunt rides out tonight

Hate is sallied forth

Troubles now are here again

What did we learn up North?

Send them all underground like the Poddle

“Send them all back” its backing breaking bottles

The ill-thought glow of a public bus in flames

Tear chairs out and carry them up the Gaol

Execute the Gael, upon them seat James.

Ana Livia I live here and could more make

Of breaks spent refusing requests for change

The Green goes red, the red is green, easter egg 1916

Skyline laws and peeling frontages, Blessing basins by ton, and Burgesses

Dublin’s not one for change

The change is never spare.

To do for Dublin, to be its Blake

Garda bike the Liffey takes

Clandestine as a married man’s Fetlife username

Print it all, Ashley Madison, immortalised on Traitor’s Gate

Leon jumped into the Liffey, on its bridge the youth getting lippy

In Garda’s face, he returns the lean projecting strength

Hoping comrades will invade the scene.

The sound of Irish rebellion is a wailed air from a keening woman

The anguished wail of a beauty-leched crone

A blood-bloated battle God whose icon is a crow

The Dwarven rhythm of iron working stone

Rebellion here has a distinctive air

A smell you’d know, an old one, a vintage rare

Wolfe Tones escaping the stout-stripped cheeks of the men who’re there.

Liars light the beacon fires inciting false rebellion

Aren't your countrymen frightened inside? You are, all of you, Trevelyan

No foreign man on Irish shores will loot thy corn for thy family’s stores

Meanwhile on every wall a pale-eyed Eastern gentleman crowned in thorns

Forgiver of forgivers, Enoch that Cain built, Enoch that spoke of rivers, Gods with horns

Riots relish, the city hellish again recalling old destructions; upriver, approaching forms

Drakeprowed viking vessels and direct invited Norman settlers

Arnott’s gutted and cameras culprits spy, what you’d imagine: spides, idlers and should-be-spayeds

We have taken up our hod and spade and ensured that public transport is yonks delayed

We left behind our God and said ‘sure, let’s have something that’s worse instead’

We have always been a mongrel breed, loam bed that rejects no seed.

A country of tall tales, tale tellers talking their tones tuning and tales talling transcendentally

Tall men up north, not quite hyperborean or Pictish but a breed apart, Giant seed

At war their well whetted bodies in violent supremacy the battle ballet, at sport their breathstealing speed

An island of ancient sports and good humoured rough stuff, Tailteann games which bring earthly fames

Men who drain drams and etch out dire dreams, Doirbh agus Draiocht and Craic agus Ceoil

Men who express disbelief through their anuses: “it is in me hole.”

Out with hatemongers down Winetavern street

Into the Liffey, we’ll observe ye all sink

The river that stinks with your blood flows sweet

The soul of the nation is suffering now, I think.

A wild hunt rides out tonight

Hate is sallied forth

Troubles now are here again

What did we learn up North?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

View of Dublin's River Liffey, the Point (or 3 Arena as it is currently known) and in the distance the Samuel Beckett Bridge. Taken from the bridge of Swan Hellenic's SH Vega.

#ireland#vsco#vscocam#irish#photographers on tumblr#photography#travel#dublin#ship#river liffey#from the bridge#panoramic ireland#sh vega#swan hellenic#at sea

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE ANNA LIVIA BRIDGE IN CHAPELIZOD

The Anna Livia Bridge, formerly Chapelizod Bridge (Irish: Droichead Shéipéal Iosóid, meaning 'Isolde's Chapel Bridge'), is a road bridge spanning the River Liffey in Chapelizod, Dublin, which joins the Lucan Road to Chapelizod Road.

IT WAS BUILT IN THE 1660s AND NAMED THE CHAPELIZOD BRIDGE

The Anna Livia Bridge, formerly Chapelizod Bridge (Irish: Droichead Shéipéal Iosóid, meaning ‘Isolde’s Chapel Bridge’), is a road bridge spanning the River Liffey in Chapelizod, Dublin, which joins the Lucan Road to Chapelizod Road.

As the Liffey flows into the town of Chapelizod, a weir divides the course to form a large mill race.…

View On WordPress

#Anna Livia#Anna Livia Bridge#areas of dublin#august#Chapelizod#Droichead Shéipéal Iosóid#formerly Chapelizod Bridge#Fotonique#FX30#Infomatique#island at Chapelizod#Isolde&039;s Chapel Bridge#murphy#road bridge#Sony#spanning the River Liffey#william

0 notes

Photo

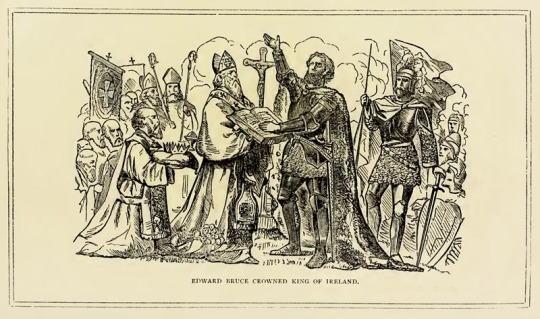

On May 2nd 1316 Edward Bruce, 6th Earl of Carrick was crowned High King of All Ireland.

Over seven hundred years ago, Edward Bruce was crowned last High King of Ireland. The English colonists in Ireland vehemently opposed him.

Edward, the brother of the King of Scotland, Robert the Bruce, led a three-year military campaign, known as the Bruce Invasion, against the Anglo-Norman lordship of Ireland.

In May 1315, a Scots army of up to six thousand soldiers landed on the Antrim coast.

All went well at first. Several chiefs declared Edward king and marched under his banner. The joint Scots-Irish force won a string of battles, causing headaches for the English king, Edward II.

But atrocious weather and food shortages crippled the campaign and led to looting. With many natives seeing little difference between Scottish and English invaders some nobles backed the latter, forming a joint Anglo-Irish force.

The invasion coincided with the Great European Famine, which brought hardship and disillusionment among Bruce’s followers. The annals ruefully commented: “falsehood and famine and homicide filled the country, and undoubtedly men ate each other in Ireland.”

In February 1317, Dublin, the capital of the English royal administration in Ireland came close to being captured Bruce’s army were encamped at Castleknock within sight of the city walls.

The panicking Dubliners burned the suburbs of the city. In order to re-fortify the city walls, they dismantled the Dominican priory north of the Liffey Bridge and tore down the bridge across the river.

Bruce's army didn’t lay siege to the city and instead moved south to Munster.

In 1318, the invasion was brought to an end when, after marching south from Ulster for one last push, Edward Bruce risked an open battle with an English army north of Dundalk at Faughart and was killed.

Annals of Ulster summed up the hostile feeling held by many among the Anglo-Irish and Irish alike of Edward de Brus:

"Edward de Brus, the destroyer of Ireland in general, both Foreigners and Gaels, was killed by the Foreigners of Ireland by dint of fighting at Dun-Delgan. And there were killed in his company Mac Ruaidhri, king of Insi-Gall Hebrides and Mac Domhnaill, king of Argyll, together with slaughter of the Men of Scotland around him. And there was not done from the beginning of the world a deed that was better for the Men of Ireland than that deed. For there came death and loss of people during his time in all Ireland in general for the space of three years and a half and people undoubtedly used to eat each other throughout Ireland."

His corpse was dismembered, and portions of it hung over the gates of various Irish towns. His decapitated head was brought to King Edward II of England by the victor, John de Bermingham, a minor Anglo-Irish baron who was elevated to the status of ‘Earl of Louth’ for bringing the Bruce Invasion of Ireland to an end.

Despite this there is a grave, at Faughart Old Graveyard, Ballymascanlan, County Louth. A small marble plaque and a large granite slab are believed to mark the resting place of the remnants of Edward Bruce’s body. A nearby stone also appears to have some significance, however. There is also a local tradition that Bruce’s body was buried there, and repeats a translation of a Gaelic account of the battle that cost him his life says that ‘a coarse unhewn stone had been set upon the grave to distinguish it as that of the king of Ireland’.

Unlike his brother Robert, who has songs, monuments, statues, poems street names and films to remember him by, there are no ceremonies or monuments or even an official wreath to remember him as the last high king of Ireland. I did notice that in some of the pics I looked through, there is often flowers and a wreath on the grave marker, so at least some people

The find a grave web page also has people leaving tributes to him, 11 in total, some state that they are “ 22nd Great Grand Father”, “22nd great uncle.”, “23 great-granduncle through my father's mother's paternal lines.” or even just “Paternal Great Grandfather”. People trying to grab a piece of their Scottish heritage no doubt.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

A St. Patrick's Day parade-goer in New York is festooned with many a shamrock but nary a four-leaf clover. Photograph By Ruth Fremson/The New York Times/Redux

Is the shamrock a Myth? The Truth Behind 5 St. Patrick’s Day Symbols

From rivers dyed green to steaming plates of corned beef and cabbage, each of the symbols we associate with St. Paddy’s Day has an origin story worth reading.

— By Erin Blakemore | March 15, 2023

Shamrocks, green beer, and leprechauns are part and parcel of any self-respecting St. Patrick’s Day celebration. But how did the traditions we associate with the March 17 holiday become associated with the feast day of a fifth-century missionary? More often than not, the story is one of cultural appropriation sprinkled with a bit of American ingenuity.

Here’s the truth behind five St. Paddy’s Day symbols.

1. Leprechauns

The leprechaun's look has changed through the years—but its image can still be found throughout Ireland like on this leprechaun crossing sign. Photograph By Bo Zaunders, Getty Images

Do you think of a diminutive green sprite with a pot of gold when you think of Ireland? You’re not alone—the leprechaun is one of the most enduring symbols associated with the nation.

But the modern idea of a leprechaun is a far cry from its origins in Irish folklore along with other tales of fictitious fairies and sprites. These supernatural beings were thought to bring good luck to humans and protect them—or tamper with their plans. The oldest written reference to the creature can be found in a medieval story about three sprites who drag the King of Ulster into the ocean.

References to the luchorpán could be found in generations of folk tales, but it took a generation of 19th-century folklorists and poets like William Butler Yeats to popularize the figure outside of Ireland. Even then, the 19th-century leprechaun was a grouchy goblin shoemaker who lived alone, wore red, and jealously guarded treasure—a far cry from the modern leprechaun who wears green, is cheerful, and lives at the end of a rainbow, where he doles out pots of gold and good luck.

This shift is largely thanks to Walt Disney, whose visit to Ireland inspired the 1960s film Darby O’Gill and the Little People, which featured a leprechaun trickster dressed in the more familiar outfit of green pants and coat, yellow waistcoat, and buckled shoes. This and other midcentury representations of leprechauns, like breakfast cereal Lucky Charms’ mascot, Lucky, promulgated Americans’ love of the small figures.

2. Shamrocks

A display entitled "Orchestra of Light" features a swarm of 500 drones animated in the night sky above the Samuel Beckett Bridge on the River Liffey for St. Patrick's Day in Dublin, Ireland. Photograph By Clodagh Kilcoyne/Reuters/Redux

Shamrocks—a three-leafed clover long associated with Ireland—are indelibly associated with St. Paddy’s day. There’s just one problem: they don’t exist in real life. “The ‘shamrock’ is a mythical plant, a symbol, something that exists as an idea, shape and color rather than a scientific species,” Smithsonian’s Bess Lovejoy explains.

Though a plant called a scoth-shemrach can be found in Irish myths, the name wasn’t linked with clover until the 16th century. Modern legend has it that St. Patrick used the three-leafed plant to explain the Holy Trinity while preaching, but despite attempts to link the real-life figure to the practice, historians agree it’s a fable.

In the 18th century, the mythical plant was taken up as a symbol of Ireland’s push for independence from Britain alongside the color green. Catholic Irish republicans’ uniforms were a green reminiscent of the isle’s grass. Their Protestant enemies adopted orange to express their identification with William of Orange, who overthrew the Catholic king during the so-called “Glorious Revolution” of 1688.

Today, Ireland’s flag contains both colors, but the shamrock in particular has come to represent the nation as a whole—and also appears on the United Kingdom’s royal coat of arms, which includes a rose for England, a thistle for Scotland, and a shamrock for Northern Ireland.

3. Green Beer and Rivers

A boat dyes the Chicago River green in celebration of St. Patrick's Day in Chicago. The process for dying the river takes two crews in two boats: One to dump dye into the river and a chaser boat to mix it all together. Photograph By Reuters/John Gress/Tedux

On St. Patrick’s Day, Ireland’s association with green extends even to beer. Like so many other St. Paddy’s Day traditions, green beer is an American invention. It is thought to have been originated by New York toastmaster and coroner’s physician Thomas H. Curtin, who in March 1914 hosted a St. Patrick’s Day bash that included green decorations and green beer.

Curtin used bluing, a laundry product imbued with blue dye that’s used to brighten up whites, to concoct the drink. These days, people make their own green beer with the help of home food coloring or beer companies who add it to kegs of brew.

Beer isn’t the only thing that turns green on St. Patrick’s Day, though. In 1961, the city of Savannah, Georgia, tried to dye its river green for the holiday. That attempt flopped, but the next year, Chicago succeeded thanks to a plumber’s discovery that a substance used to detect leaks into the Chicago River tinted it a gorgeous Irish green. It’s been turning green for the holiday ever since, thanks to 40-plus pounds of dye that lasts for about five hours.

4. Harps

Ireland's love for the harp dates back to at least the 8th century. Beyond a symbol of St. Patrick's Day, it's also the logo of the Irish government. Photograph By Karol Majek/Getty Images

When Norman chronicler Gerald of Wales traveled to Ireland in the 1180s with members of England’s royal family, he was disgusted by what he called the “barbarous” Irish. But when regaled with music by Irish harpists, he almost changed his mind.

“The only thing to which I find that this people apply a commendable industry is playing upon musical instruments, in which they are more incomparably skilful than any other nation I have ever seen,” he wrote, marveling at the “deep and unspeakable mental delight” of the Irish harp.

By then, the harp was deeply embedded in Irish culture. Stone sculptures in Ireland show harps all the way back to the 8th century, though scholars debate how much they resembled modern instruments.

“The harper was extremely well revered in Gaelic society,” said Irish musicologist Mary Louise O’Donnell in a 2015 talk and recital at the Dublin Central Library. Harpists were part of chieftains’ entourages, creating music to accompany poems about their masters’ greatness.

Over time, the harp became a symbol of national pride. Ireland’s coat of arms includes the instrument, which was also adopted by multiple nationalist and rebel movements throughout the nation’s long history. In 1862, Irish brewing juggernaut Guinness adopted it as part of the company’s logo—and when Ireland became self-governing in 1922, it had to flip the orientation of the harp on its official government logo to avoid running afoul of the brewer’s trademark.

5. Corned Beef and Cabbage

Corned beef and cabbage has become a traditional meal on St. Patrick's Day—but this custom originated in the United States with the arrival of Irish immigrants in the mid-19th century. Photograph By Grandriver, Getty Images

Hungry? You may well eat a big plate of corned beef and cabbage on March 17. But that tradition, too, is American. Beef was actually uncommon in early Ireland, where people preferred pork and beef was only accessible to the richest residents. But over time, Ireland began producing and exporting beef to wealthier England, whose elite preferred cows’ meat.

By the 1600s, beef was Ireland’s biggest export. In 1666, however, English landowners demanded a stop to imports of Irish beef, claiming it competed with their business interests. A series of laws followed, banning Ireland from exporting live cattle to its neighbor. This pushed down the price of Irish beef, so Ireland transformed its beef export industry into a beef preservation industry, using cheaply available salt to create corned beef—so named because of the corn-sized grains of salt used to make it.

Though most of the Irish could not afford their own product, eating potatoes instead of meat, the nation became known for its corned beef. When Irish immigrants flooded into the U.S. in the mid 19th century, they became more prosperous than their predecessors—and they used their newfound money to purchase salted beef brisket from Jewish butchers and deli owners. The “boiled dinner” of corned beef and cheap cabbage has been associated with Irish Americans’ celebration of their heritage ever since.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

.

Originally called the Wellington Bridge (after the Dublin-born Duke of Wellington), it was later changed to Liffey Bridge (Irish: Droichead na Life)

It is most commonly referred to as the Ha'penny Bridge.

The Ha'penny Bridge (/ˈheɪpni/ HAYP-nee; Irish: Droichead na Leathphingine, or Droichead na Life), known later for a time as the Penny Ha'penny Bridge, and officially the Liffey Bridge, is a pedestrian bridge built in May 1816 over the River Liffey in Dublin, Ireland.

Before the Ha'penny Bridge was built there were seven ferries, operated by a William Walsh, across the Liffey. The ferries were in a bad condition and Walsh was informed that he had to either fix them or build a bridge. Walsh chose the latter option and was granted the right to extract a ha'penny toll from anyone crossing it for 100 years. Initially the toll charge was based to match the charges levied by the ferries it replaced. The toll was increased for a time to a penny-ha'penny (1½ pence), but was eventually dropped in 1919. While the toll was in operation, there were turnstiles at either end of the bridge.

2 notes

·

View notes