#le mans '66

Photo

Ford GT 40 1967 (Du film Le Mans 66 / Ford v Ferrari). - source Maple Brothers Auction.

213 notes

·

View notes

Photo

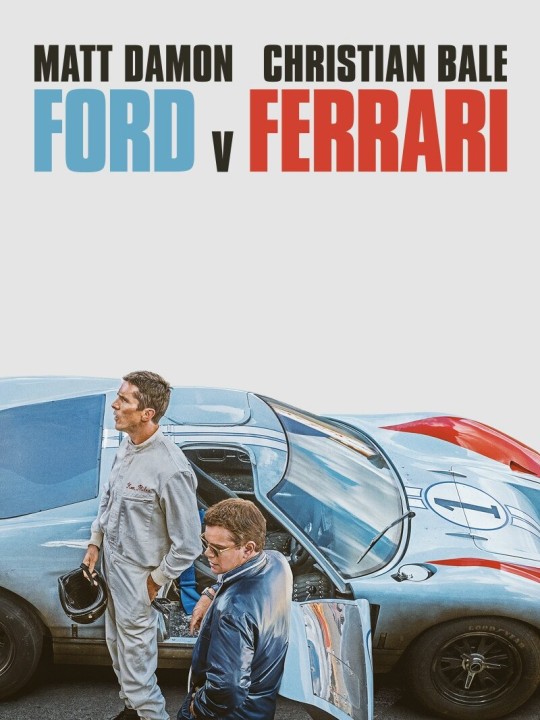

FORD V FERRARI

2019, dir. James Mangold

#*#ford v ferrari#tuserlou#usersavana#userjack#usergiu#userzo#userpayton#fyeahmovies#filmgifs#le mans 66#by el

331 notes

·

View notes

Text

#movies#polls#2010s movies#ford v ferrari#le mans 66#james mangold#christian bale#have you seen this movie poll

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

ken miles is king 🏎️🏁

#my art#ford vs ferrari#art#sketch#ooly#oolycreateyourhappy#ooly smooth doodlers#ken miles#talens sketchbook#talens art creation#sketchbook#royal talens#le mans#le man 66#le mans 24#24 heures du mans#enzo ferrari#ferrari#ford gt#road to le mans#michelin#james mangold#henry ford#ford#paint sticks#christian bale#matt damon#cars#car art#fan art

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can anyone guess who played a role in the film ‘Le Mans 66’ as the translator at Ferrari meeting… you may know her better in @station19greys as Carina Deluca …

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vanity Fair Oscars Party • 2017 • Designer: Alberta Feretti

Vanity Fair Oscars Party • 2019 • Designer: Dundas Couture

Academy Awards • 2020 • Designer: Valentino

Vanity Fair Oscars Party • 2020 • Designer: Prabal Gurung

Academy Awards • 2022 • Designer: Louis Vitton

Vanity Fair Oscars Party • 2022 • Designer: Louis Vitton

Photo: Vanity Fair Slideshow • Other Photos: Getty Images

GIF

GIF

Remember… fashion you can buy, but style you possess. The key to style is learning who you are, which takes years. There's no how-to road map to style. It's about self expression and, above all, attitude. — Iris Apfel

Seem like only 319 days ago…

#Tait rhymes with hat#Good times#Le Mans ‘66#Ford v Ferrari#Belfast#Vanity Fair Oscars Party#Wallis Annenberg Center for Performing Arts#Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences#AMPAS#Academy Awards#Oscars#Dolby Theatre#26 February 2017#24 February 2019#9 February 2020#27 March 2022#Los Angeles California USA#Getty Images#Campaign To Shorten Awards Season

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think in the lead up to Le Mans I should watch every Le Mans related film or documentary i recommended in my WEC intro

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

There are stories your read or watch, then come back. And each time, you go through this story with this totally ridiculous hope that this time it would end another way for someone.

I don't often get this feeling. The Witcher is one of those stories. Gollum's story in LOTR movies (in books, not so much, but zu haven't read them in ages).

Now I can add to this list the movie Le Mans 66 (or Ford v Ferrari, someone please explain to me, which title is the official one, because keep tripping over both online). It could end about 10 minutes before it does. I never thought I would let a story about car racing catch me so much, keep me so captivated, that I would actually go through a bunch of interviews and the making of materials. And that I would rewatch it.

Yet here I am, adding this movie to this ridiculous list that makes me hope for different ending. It's a good list.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ford vs Ferrari / Le Mans 66 (2019)

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ford v Ferrari? I only know Toyota v Ferrari

#we're being FED#I LOVE COMPETITIVE RACING!!!#WEC Liveblog#Le Mans edition#(Le Mans 66 is a great film though; can def recommend)

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Movies

Hi, Barbie.

Barbie

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse

Goncharov

Nimona

Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery

Red, White, and Royal Blue

Lord of the Rings -3

Black Panther +24

The Addams Family

The Super Mario Bros. Movie -4

Knives Out

Puss In Boots: The Last Wish

Oppenheimer

The Hunger Games

Avatar: The Way of Water

Guardians of the Galaxy

Shrek

The Little Mermaid +15

Scream -1

Top Gun: Maverick -1

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem

Everything Everywhere All At Once +7

Saw +14

Twilight -13

Wendell & Wild

Howl's Moving Castle -6

The Hobbit -3

Five Nights at Freddy's

Enola Holmes

My Policeman

Deadpool -8

How to Train Your Dragon +12

Beauty and the Beast +16

Avatar

Scream VI

Bottoms

Mean Girls +6

Megamind -4

Metalocalypse: Army of the Doomstar

Spirited Away -10

The Batman -38

Rogue One: A Star Wars Story

Venom -34

Les Misérables

Encanto -44

Iron Lung

Coraline

The Thing

John Wick

Strange Way of Life

Blue Beetle

Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny

Legally Blonde

Frozen -14

Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves

Ghosted

American Psycho -7

Princess Mononoke

Dune -49

The Princess Bride

Teen Wolf: The Movie

Star Wars: Episode III—Revenge of the Sith -21

Pacific Rim

Renfield

Shrek 2

Saw X

The Old Guard -29

Nope -47

Spider-Man: Beyond the Spider-Verse

Night at the Museum

Soul -26

The Mummy

The Nightmare Before Christmas

My Little Pony: Equestria Girls

Hellraiser

The Lost Boys

The Marvels

Emesis Blue

The Shape of Water

The Menu

My Neighbor Totoro

Shazam -40

Sonic the Hedgehog -66

Pirates of the Caribbean -48

The Hunger Games: Catching Fire

Elemental

Lilo & Stitch

Fight Club

The Dark Knight

The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds & Snakes

The Princess Diaries

The Incredibles

Halloween Ends

The Lorax

10 Things I Hate About You

Heathers

Kung Fu Panda

The Devil Wears Prada

Rise of the Guardians

Birds of Prey

The number in italics indicates how many spots a title moved up or down from the previous year. Bolded titles weren’t on the list last year.

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

What did Caitriona say about Christian Bale after working with him?!

Dear Christian Bale Anon,

I just wrote 'notoriously difficult'. I never implied she said anything along those lines herself. But your OTT reaction immediately unmasked you, dear Stan Militia Anon.

It took me exactly 30 seconds to Google find the most interesting public statements she made about working with Bale and Damon on set:

Namely, a Sarina Bellissimo podcast for the Irish radio station Spin FM, on November 19, 2019:

This statement resumes it all - but it still makes for an interesting listen (has it been posted before? I suppose it must have, her Stans will post every single shred she ever uttered):

Plus, on the very same day, an interview for Steven Weintraub's Collider (https://collider.com/caitriona-balfe-interview-ford-v-ferrari-outlander-season-5/), which reads along the same lines:

And then, you have this:

youtube

Bale is mentioned around the 0:23 mark and I have to say, the contrast with all the rest of the interview is palpable. She is tense and a bit uneasy. Body language is a bitch, I know.

That being said, remember (LOL) these are public statements. What exactly did you want or expect her to say? And, if I may add, what exactly did you want or expect me to say, too?

Ignore your submission? Lie about it - and give you the opportunity to brownnose me in public?

You probably don't know me, Anon. Also, use your logic: she sounded very enthusiastic about her experience with him, on set - I'll give you this and again, this is absolutely polite, civilized, normal, expected (insert anything you want here, really). But it takes two to tango, don't you think?

Well...How about this cast Q&A at the Toronto International Film Festival's screening (September 10, 2019)? I think the real dynamic is showing and mind you: he never mentioned C, his screen wife. Who stood almost next to him, on stage: her expression is interesting to analyze, perhaps halfway between being starstruck and keeping a brave face:

youtube

Not a single time. And barely, if at all, in all the other interviews. And I am not very sure he even looks at her while she's talking (he isn't reacting to her infectious laughing, so long for the fish). This guy presents himself as a sociopathic boor.

Sidenote: funny thing that a new bride talks about the importance of marriage teamwork and mentions Ma and Pa. I rest my case.

Back to our topic, I have to say the Irish press didn't seem to like Bale at all. Irish Central, for example, is very kind to C, but less so to Bale (https://www.irishcentral.com/opinion/caitriona-balfe-ford-v-ferrari):

I think I gave you enough attention for today. Now go take this answer elsewhere. On your own page (remember the address?) or as an Anon to the Amateur Eugenicist. She loves those slap-a-shipper, cheap gossip wares. She'll probably publish you.

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could you talk about Robespierre and Brissot??? Or maybe more about Brissot, I'm really curious about him!

1789-1792

In his memoirs (written 1793), Brissot writes the following about his activities as a law student in Paris around 1774:

Before leaving the subject of Nolleau’s chambers, […] I must recall the fact that chance gave me there, as second clerk, a man who has since played an amazing part in the Convention, but against whose future celebrity I should at that time have been prepared to bet anything. Ignorant, without knowledge of any scientific subject, incapable of conceiving or expressing an idea of any kind, he was eminently fitted for a career of dishonesty.

Though Brissot doesn’t state it outright, the second clerk and future member of the Convention mentioned here was at first identified as Robespierre. When Claude Perroud published an edition of the memoirs in 1912, he did however dismiss the idea entirely, considering the fact that in 1774, there would be another four years before Robespierre even began to study law in the first place.

If connections between Brissot and Robespierre before the revolution is something we’re in other words lacking, once we’re into it, it doesn’t take long before the former starts to mention the latter’s name. This in relation to describing interventions made by him during the sessions of the National Assembly and the Jacobin Club in his newly founded journal Le Patriote Français. Based off volume 6 of Oeuvres complètes de Maximilien Robespierre, I find Brissot to have mentioned Robespierre’s name a total of 26 times throughout 1789 and 1790, the very first being in number 17 (August 27 1789). As the journal was more concerned with giving a neutral summary of the sessions, as opposed to spreading the author’s own opinions, most of these cannot be used to determine what Brissot’s personal stance on Robespierre was. Sometimes, the overall neutral tone does however give way for a bit more colorful adjectives:

M. Roberspierre [sic] wanted us to adopt this truly noble formula: ”Louis, by the grace of God and by the will of the Nation; King of the French: To all citizens of the French Empire; People, here is the law that your representatives have made for you, and to which I have affixed the Royal seal. He wanted to develop his thoughts, but he was stopped from doing so.

Le Patriote Français, number 66 (October 10 1789)

M. de Robespierre claimed that martial law should not be imposed in the critical circumstances in which the Nation finds itself plunged, and he produced a great impression, with an idea that is imposing and sublime at first glance but which lacks accuracy.

Le Patriote Français, number 76 (October 22 1789)

MM. Roberpierre [sic], Biauzat, and Chapelier easily shattered this diplomatic erudition and proved that it was not a question of the rights of the Province of Cambrésis but of a crazy deliberation of an unconstitutional body.

Le Patriote Français, number 105 (November 21 1789)

M. de Robespierre defended good principles, he showed that the executive power had an interest in increasing the number of wars, while the interest of the legislative power laid in avoiding them. He concluded that it was dangerous to entrust the law of war to the former.

Le Patriote Français, number 184 (May 19 1790)

...There is, however, an article touched by M. Robespierre which has aroused murmurs. This ardent orator made it understood that priests must belong to society through the first of bonds, that of marriage. There is no one who has reflected a little on the cause of ecclesiastical corruption, who has witnessed the good effects of the marriage of priests among Protestant sects, who is not convinced of the necessity of this reform. But although all good minds are convinced of it, although all are convinced of the possibility of combining it with Catholic doctrine, not all also think that this is the moment to propose this idea; they are stopped by the fear of increasing the effervescency among the ignorant: it is perhaps only a false terror... In any case, we must at least prepare the minds, and that is what M. de Robespierre had not done.

Le Patriote Français, number 197 (June 1 1790)

M. Robespierre responded very well to the prepositions, by proving that the legislators of a people that succumb under the weight of taxes and debts, can not lend themselves to sentiments generous enough to leave to the prelates their immoderate powers.

Le Patriote Français, number 320 (June 14 1790)

M. Robespierre courageously defended the true principles against M. d'André.

Le Patriote Français, number 474 (November 25 1790)

In his memoirs, Brissot writes that Robespierre in July 1790 brought him a copy of a letter to Desmoulins to insert in Le Patriote Français — ”I remember on this occasion Robespierre with his fears and his scruples which he could not dissimulate. Desmoulins' thoughtlessness alarmed him; he didn't know what to think of it.” Brissot did however ”think it agreeable” to Desmoulins to insert neither this letter, nor the response the latter wrote in return and which was also given to him. In December the same year, both Robespierre and Brissot signed the wedding contract and attended the wedding ceremony of said Desmoulins, who in a letter to his father reported that everyone present had been driven to tears during it, after which they all went over to have dinner at his place. These are the earliest confirmed meetings between Brissot and Robespierre that I’m aware of, though it’s far from impossible they had had contacts prior to this as well.

Brissot continues to bring up Robespierre in his journal throughout 1791. He mentions his name or debates which he has taken part in around 50 different times, calling him things such as ”a vigorous defender of liberty” (number 525, January), ”a friend of principles” (number 571, February), ”an enlightened patriot” (number 600, March), ”a vigorous patriot” (number 608, April), ”[someone with] rigorous principles” (number 646, May), ”[someone] favored by eternal principles and sound politics” (number 659, May), and ”a good patriot, firm in principles, deaf to considerations [and] the most implacable enemy of the aristocrats” (number 676, June), and openly showing his support for his stance on topics such as the colonies/the rights of men of colour (number 646, May, number 671, June, number 777, September), the self denying decree (number 608, April), the right to bear arms (number 630, April), the dismissal of army officers (number 673, June) and other smaller affairs (number 586, March, number 591, March, number 592, March).

On April 2 1791 Mirabeau passed away, and the following day, Robespierre proposed to the Assembly that the honors of the Pantheon be given to him. In his memoirs, Brissot claims that ”Pétion reproached [Robespierre] for this the same day, he reproached him for it in my presence.”

On June 18 1791, Adrien Duquesnoy attacks both Brissot and Robespierre in number 30 of his journal Ami des Patriotes — ”We are, moreover, on the eve of reaping the fruits of the infernal spirit of system which torments MM. Robespierre, Brissot, etc. They have shouted so much against the distinction of active citizens.” In number 682 of Patriote Français, Brissot responds to his charges and at the same time clarifies that he and Robespierre don’t have any private contacts:

What more will I say about the connections you tie between me and M. Robespierre, and about this infernal spirit that you attribute to us both, about this party over which you make us preside? I have always liked to pay tribute to the inflexible patriotism of M. Robespierre, but I do not share all his opinions; but I don't see him; more than a month has passed since I last had the pleasure of servicing him (de l’entretenir). Party leaders who form a coalition see each other, I believe, a little more frequently.

The number was released on June 21 1791, the same day Paris woke up to the discovery that the royal family had fled the capital during the night. In her memoirs (1793) Madame Roland claimed to in the afternoon have seen both Robespierre and Brissot at Pétion’s house discussing these most recent events:

I was struck by the terror with which [Robespierre] seemed to be overcome on the day of the king's flight to Varennes; I found him in the afternoon at Pétion’s; where he said with concern that the royal family would not have taken this course without having a coalition in Paris which would order a Saint-Barthélemy for the patriots, and that he expected to be dead within twenty-four hours. Pétion and Brissot said, on the contrary, that the flight of the king was his loss, and that it was necessary to take advantage of it; that the dispositions of the people were excellent; that it would be better enlightened on the perfidy of the court by this approach than it would have been by the wisest of writings; that it was obvious to everyone, by this fact alone, that the king did not want the constitution he had sworn to; that it was time to ensure a more homogeneous one, and that it was necessary to prepare minds for the Republic. Robespierre, sneering as usual and biting his nails, asked what a Republic was!

One month later, July 16 1791, both Brissot and Robespierre are found signing the same adress as two of 24 members of the Jacobin Club’s Committee of correspondence. This is the third time Brissot is listed as taking an active part at the club as far as I can see, and the first time he and Robespierre are mentioned during the same session. The day right after, in number 707 (17 July) of Le Patriote Français, Brissot is found agreeing with Robespierre in the big discussion regarding what’s to be done with the king following his capture at Varennes and return to Paris the month before:

…It is very true that to have the king judged by the legislative body would be to violate principles. Also their defenders, Robespierre and Buzot, constantly asked that this great trial be referred to the nation. In that way, we don’t make one power dependent on the other.

The same day this number was released, the massacre on the Champ de Mars took place. Three days later Brissot defends Robespierre against allegations he would be responsible for what had just happened in number 710 of his journal:

Let patriots in all parties stop accusing each other of being the authors of this terrible catastrophe. How did one have the audacity to suspect even the purest virtue? How did one have the audacity to suspect and circulate that MM. Buzot, Pétion, Robespierre were at the head of this uprising? How did one try to raise the national guards and the people against them? Have we therefore already arrived at the unfortunate times of demagoguery, when Socrates and the Phocians [sic] were made to drink the hemlock?

Unlike many other journalists who had to quit their journals in the wake of the massacre due to arrest or going underground, Brissot managed to avoid any repercussions and could stay in Paris and keep his running. In number 774 (September 23 1791), he does however make it clear that, following his election to the Legislative Assembly on September 14 (a place which he surely had the by Robespierre proposed self denying decree much to thank for), he will have to occupy himself much less with Le Patriote Français and leave most of the editing other hands, but nevertheless continue to give it his ”full attention.” If it would thus appear his role in the editing continued to be considerate, I don’t know how to measure just how much responsibility Brissot is to take for the things that appeared in the journal following this moment…

A week after Brissot’s announcement, the National Assembly was closed down, and yet another week later, October 16, both Robespierre and Brissot are listed as two of twelve jacobins appointed to take part in ”conferances on moral and constitution.” The former did however soon thereafter leave Paris for a visit back to his hometown. He was back in the capital in late November, after which it didn’t take long before a wrench was driven between him and Brissot.

It all started on December 16, when Brissot, after a two month long absence from the Jacobins, showed up and there delivered his first speech in favor of France going to war against German princes (Discours sur la nécessité de déclarer la guerre aux princes allemands qui protègent les émigrés). After the speech was finished, Robespierre, who had shown his opposition towards the idea of war already on December 9, 11 and 12, when brought up by Carra or Réal, suggested the printing of it be adjourned. Two days later, December 18, he responded to Brissot with a speech of his own (Discours de Maximilien Robespierre sur le parti que l'Assemblée Nationale doit prendre relativement à la proposition de guerre, annoncée par le pouvoir exécutif…). After he had finished reading it, Sillery rose to support Robespierre’s position, while Brissot asked to obtain the floor to speak against him during the next session. On December 21 and 25, Carra, Machenaud and Simonne all spoke in favor of going to war, while Desmoulins on December 26 instead took Robespierre’s side with a speech against it. Four days later, Brissot held his second speech in favor of the idea (Second discours de J.-P. Brissot, député, sur la nécessité de faire la guerre aux princes allemands). Journal des Débats de la Société des Amis de la Constitution reported the following in regards to the session:

M. Brissot reads a very long speech, frequently interrupted by applause, on the necessity of an offensive war. He ends with an exhortation to true patriots to submit to the law and never allow themselves to attack the constitution in any way. This exhortation appears to MM. Robespierre and Danton a criticism and an indictment made to the speakers and writers of the Society, because of the kind of affectation which appears to them to be there. They rise to demand the change of this passage in the printing made of this speech. The greatest warmth spread throughout the Society during this discussion, in the midst of which M. Brissot, giving the most striking testimony of the attachment the Societies and M. Robespierre have for the constitution, undertakes to correct the end of his speech in a way so that it won’t leave any doubt regarding his intentions. The sitting is ended at eleven o’clock.

Three days later, January 2 1792, Robespierre held his second long speech on the subject. Unlike his first one, where he had just spoken against going to war in general, here he rather chose to mainly speak against the arguments Brissot had used for it in his speech on the 30th.

…I will try to fulfill this purpose by responding mainly to the opinion of M. Brissot. If general features, if the brilliant and prophetic portrayal of the successes of a war ending with all the peoples of Europe fraternally embracing one another, are sufficient reasons to decide such a serious question, I will say that M. Brissot has perfectly resolved it; but his speech seemed to me to present a vice which is nothing in an academic discourse, and which is of some importance in the greatest of all political discussions; it is because he has constantly avoided the fundamental point of the question, to raise his entire system on an absolutely ruinous basis.

According to Journal général de France, there were however still no hard feelings between Robespierre and Brissot, who ended up embracing each other after the speech:

A great split has just taken place among the Jacobins. M. Robertspierre [sic] has always maintained that we should not wage war: it places in the hands of the executive power means that it could use against the constitution. M. Robertspierre's [sic] obstinacy in maintaining his opinion had made him quarrel with M. Brissot; but they solemnly reconciled, and the club applauded with enthusiasm the embraces they lavished upon each other. Today, M. Robertspierre [sic] is fighting against MM. Brissot, Guadet, Vergniaud, Grangeneuve. The ascendancy of Mr. Robertspierre [sic] still makes success uncertain.

Robespierre had ended his speech promising he would come with further clarifications a few days later, which he also did on January 11. A week after that, January 18, he and Brissot got into a controversy regarding a letter that would have praised Lafayette and expressed doubt over the patriotism of the inhabitants of Metz, printed in number 891 of Le Patriote Français, that had been released the very same day:

Robespierre […] was surprised to have seen a patriotic newspaper, Le Patriote français, expressing doubts about the patriotism of the inhabitants of Metz, and praising La Fayette.

A member asks to make a point of order, and observes that this letter had been inserted the day before in the Moniteur.

Several voices: You’re attacking the patriotism of M. Brissot.

M. Brissot: I declare to the assembly that I was unaware of the letter which was inserted in Le Patriote français by my collaborator. M. Robespierre seemed to cast doubt on the authenticity of this letter. I just saw M. Roederer, who assured me that he had seen the original, and who guarantees it to be genuine. Mr. Robespierre seemed to attack my silence. The painful task that I have imposed on myself prevents me from contributing to the journal assiduously; yesterday I once again spoke for an hour at the National Assembly, and the people can judge whether I am abandoning their cause.

M. Rouyer: Messieurs, I render justice to the patriotism of M. Robespierre and M. Brissot; I am angry that we discuss people when the public good needs us. I am guarantor of both; I ask the Society to move on with the agenda.

M. Robespierre: I declare, in particular, that I am very pleased that M. Brissot was unaware that this letter had been inserted in his journal; I am far from thinking that he wrote it, since the title states that it was inserted in the Moniteur: it is because it is in a newspaper which enjoys a great reputation that I thought it necessary to speak; I have never attacked M. Brissot, our principles are the same; I only refuted his opinion. I come back to my point: I say that the National Assembly must display great character, that it must bring order to the kingdom, that it must never protect the impunity of ministers, that it must exhaust all the good that legislators can do, and then it can declare war.

M. Rouyer climbs to the rostrum and makes some observations in favor of war.

M. Louvet reproaches Robespierre for not seeing the danger where it is, for denying it elsewhere, and thereby incurring a very great responsibility.

The sitting ends at ten o’clock.

In number 893 (January 20) of Patriote Français, Brissot’s collaborator Girey-Dupré responded to Robespierre’s charges, writing that the letter, which had been printed not only in Patriote Français but other ”patriotic journals” as well, had only been an extract from the Moniteur and did not contain any praise of Lafayette. ”As for the suspicions that M. Robespierre tried to spread against this paper,” Girey-Dupré adds, ”I have disregarded the slanders of the aristocrats and the ministers, I can well endure the bad mood of a patriot.”

At the session of the Jacobins held the very same day, Brissot held his third speech in favor of war, where he chose to mainly respond to the arguments laid out by Robespierre most recently, just like the latter had done with him on January 2:

I’m now arriving at the arguments Robespierre made against me at this tribune that I still haven’t answered. […] It is very strange to today see M. Robespierre walking on the same line as the ministry, nevertheless maintaining that he is on the opposite side, and claiming that those who support him are actually against him. […] Certainly, we will not accuse, despite these connections, M. Robespierre of being in concert with the minister; but he should at least believe that this concert does not exist between this minister and those who openly fight him, who vigorously denounce the vices and abuses of his administration. This idea brings me back to some insinuations on the purity of my intentions, which distort Mr. Robespierre's speeches. They are foreign to him, I like to believe; for I have seen him, I have known his soul, and wickedness never came near him. If there are disguised poisons in his speeches, I will only attribute them to the suggestions of men against whom he is not sufficiently armed with distrust.

When the speech was over, Brissot and Robespierre were made to embrace each other yet again:

M. Brissot justifies himself in response to the insinuations thrown at him by Robespierre in a previous session, and implores him to put an end to a dispute which can only be agreeable to the enemies of the public good.

M. Dusaulx: All the patriots of this club have long been suspended in the course of a discussion which seemed to compromise two good patriots who must love and esteem each other; something would be missing after what M. Brissot said before leaving this assembly, it is the duty of these two generous men to embrace each other.

No sooner had he finished than MM. Robespierre and Brissot were in each other's arms, amid the unanimous applause of the Society, moved by this touching spectacle.

M. Robespierre: By yielding to M. Dusaulx's invitation, I only gave myself up to the impulse of my heart, I gave what I owed to the confession and to the fraternity and to the feeling depth that I have of a man who enjoys the greatest consideration and who must render the greatest services to the fatherland; I will prove to M. Brissot how much I am attached to him. This should in no way change the opinion that every man should have of the public good; it is to do all that will be in me, and what I believe necessary for the public safety, that I will ask to answer in another session to the speech of M. Brissot. (speech 3?)

M. Rœderer: I ask for the floor to point out an oversight which, no doubt, escaped M. Robespierre, and that is to request the printing of M. Brissot's speech. I ask for it in his name.

Robespierre did however think this gesture had been a stupid one, as revealed through a letter he wrote to Antoine-Joseph Gorsas, author of the journal Courrier des 83 départements, eight days later. He also safeguarded his own position on the war (that he by then had already held a third speech against on January 25), which he meant Gorsas had gotten wrong when describing the session on the 20th in the latest number of his journal:

I noticed in your number from today an error which deserves to be corrected. When summarizing the latest session at the Friends of the Constitution, the article of which I’m speaking supposes that I have renounced my principles on the important questioned which today agitates all the spirits, since one feels it holds onto public safety and the maintenance of liberty. I would consider myself little deserving of the esteem of good citizens had I played the role this article ascribes to me. What is true in this recital, is that, after a speech held by M. Brissot, on the pathetic invitation of M. Duseaux, the two of us cordially embraced, applauded by the entire club. It is also true that I went through with this action with much pleasure, that the important discussion where we had embraced holding different opinions, had not left any bitterness in my soul; that I am far from viewing as particular quarrels debates that interest the fate of the people, and where I have never held any passion other than that for the public good. Also, far from thinking that neither the fate of the big question which occupies all of France, nor my particular opinion could in any way be subordinated to my sensibility and my personal affection for M. Brissot, I immediately mounted the tribune in order to manifest this sentiment in the following way: ”I just fulfilled a duty consisting of fraternity and of satisfying my heart; I still have an even more sacred debt to pay to my homeland. The profound sentiment which ties me to it, neccessarily supposes love for my fellow citizens and for those with which I have the closest of bonds: but all individual affections must give way to the sacred interest of liberty and of humanity: I could easily reconcile it here with the attachment, with the respect that I have promised to all those who have served the homeland well, and who will continue to serve it well. I embraced M. Brissot with this sentiment, and I will continue to combat his opinion on the points where it differs from my principles, by indicating where I agree with him. May our union rest on the sacred base of patriotism and virtue, let us fight like free men, even with energy if it’s needed, but with respect, with friendship.”

Robespierre.

Robespierre didn’t hold more speeches purely about being against war following January 25, but continued to show his opposition at the Jacobins regardless throughout the following months. On February 10, he held a speech with the title On the Means to save the State and Liberty, ”that is to say, (he underlined) to stifle civil war and foreign war, by confusing all the projects of our internal enemies.”On February 24 he spoke out against the club’s committee of correspondence for having stated that the club was in favor of the war, and that those who had supported the opposite party had changed their mind — ”As for me, it remains for me to prove that I have not renounced my opinion in favor of a party that I consider to be the most dangerous for the homeland and for liberty.” Two days later, he demanded that a circular meant to be sent to the sister clubs in the provinces regarding the question include a table containing the reasons put forward by different speakers for or against war, as opposed to stating the majority of the society was for it. Brissot on the other hand retreated back to the Legislative Assembly to continue pushing his agenda there instead, supported by people such as Louvet, Gensonné, Vergniaud, Isnard, Guadet, Manuel, Roederer, Bangal, and Cloots. Number 963 (March 30 1792) of Le Patriote Français contained an article titled ”On the new tactic of the enemies of liberty” and, while not naming Robespierre by name, suggested that those that were against war had ulterior motives for doing so — “any opinion against the war can only be very disastrous, and we understand that it must be used by this Austrian committee, which wants to give its friends time to prepare to attack us.” The article is not signed by Brissot and as mentioned above, he had by this point in large part handed over the editing to others. Regardless, it can probably be concluded that such an article appearing in what was technically still his journal did no miracles for his and Robespierre’s relationship.

In February, Desmoulins released the 60 page long and influential pamphlet Jean [sic] Pierre Brissot démasqué, which acted both as a denounciation of Brissot, treated, if not yet as a full blown traitor and counterrevolutionary, at the very least as a fool and an object of ridicule, but also as a defence of ”my college friend” Robespierre. In Choosing Terror (2014), Marisa Linton writes that Robespierre ”may well have been involved in [the pamphlet’s] production,” probably basing this on the fact that we know he had had a hand in other of Desmoulins’ works. If we’re lacking any tangible evidence for this in the case of Jean-Pierre Brissot démasque, Desmoulins did himself nevertheless claim that ”[Robespierre] sees me as invulnurable after the proof of incorruptibility that I produced in my latest writing to Brissot” in a letter inserted in Journal de M. Suleau not long thereafter.

On April 20 1792, Brissot and his allies finally had their way as France declared war on Austria. The very same day Robespierre spoke at the Jacobin club, saying that, now that the dice had been rolled, he too was in favor of ”conquering Brabant, the Netherlands, Liège, Flanders, etc” while also stating that ”now is above all the time where we must supervise the executive and the constituted authorities.” Three days later, April 23, he asked the Jacobins to for the opportunity to share his thoughts on “a civil war plan presented to the National Assembly by one of its members” during an upcoming session. But before that could happen, on April 25, Brissot showed up at the Jacobins for the first time since January 20, when Dusaulx had made him and Robespierre embrace, and delivered a long speech where he defended himself against accusations that he would have nominated ministers, been allied with Lafayette and Condorcet and dined together with Narbonne and Madame de Staël, and, while not naming Robespierre by name, warned of ”agitators” seeking to divide the society in the time of war:

Their (aristocrats and agitators) conduct is the same; like the friends of the court, the agitators denounce and seek to divide the patriots; like the friends of the court, they cry out against war, when war is wanted by the majority of the patriots. [applauds]. Certainly, I will not imitate my adversaries' ease of slander, I will not rely on rumors that they are paid by the civil list; I will not denounce based on rumors that they have a secret committee to influence this Society; but I will say that they follow the same path as the supporters of civil war. I will say that, without a doubt, they do more harm to patriots. At what point do they come to divide this Society? At the moment when external war and internal war threatens us. Ah! Gentlemen, why, for several months, have one been trying to hijack the agenda here? The most important questions demand your attention. When all the Societies of the kingdom expect you to solicit a host of decrees favorable to the people, the sanction of which is easy in the present state of the ministry, you let slip an opportunity which perhaps will never arise again; It is time to occupy yourself with the discussion of the objects which interest the National Assembly, and which we want to make you lose sight of. I ask the Society to give explanations on this, and I conclude that, denouncing the denunciations that I have refuted, we move on to the agenda.

Right after this, Robespierre tried to take the floor for a point of order, but this request was refused and instead obtained by Guadet, who started denouncing Robespierre, calling him an ”imperial speaker” who would only talk about himself — ”M. Robespierre had promised to denounce a civil war plan formed within the National Assembly itself, I summon him to do so. I denounce a man who constantly puts his pride before public affairs, the position to which he was called. I denounce a man who, whether ambition or misfortune, has become the idol of the people.” Robespierre then took to the floor, declaring that ”my most ardent adversaries are not MM. Brissot and Guadet” but nevertheless requesting time to properly respond to them, something which he was given. Two days later, April 27 1792, he could deliver a speech by the name of Réponse de M. Robespierre, aux discours de MM. Brissot & Guadet du 25 avril 1792. Robespierre criticized both of the in the title named men, before nevertheless asking for peace — ”I only want to give you proof of moderation. I offer you peace on the only conditions that the friends of the homeland can accept. On these conditions I gladly forgive you for all your slanders.”

But just three days later, April 30, Robespierre complained to the Jacobins that the printed versions of the speeches Brissot and Guadet had held on the 25th matched badly with what they had actually said. His objection did however not gain any support from the president Lasource. A little more than a week later, in number 1003 (May 9 1792) of Patriote Français, we find an article titled ”On the war of M. Robespierre,” signed by Brissot and with the following content:

M. Robespierre continues to wage war against me, to denounce me, and to have me denounced to the Jacobins. I won't bother to answer him; this war is a scandal, and can become a source of calamity for liberty. Despite all the advantage that my adversaries give me over them, I consider it a real crime to continue it. The pain of true patriots, the joy of feuillans, and the interest of liberty, command my silence. Moreover, this war will fall by itself, I like to hope, because it is only about absurdities, and the people do not pay for absurdities for long. The trial between M. Robespierre and me will be judged by our common conduct. He deserted his post (as public prosecutor), without being able to give a single good reason; I am and will be faithful to mine. It is by faithfully fulfilling my duties, and not by eternally denouncing that I will respond to him. I expect him at the end of the legislature; I will produce my actions, we will examine his, and the public will be the judge of our patriotism. Agendo non dicendo was Cato's motto, and it is also mine.

A week after that, May 17, the first number of Robespierre’s new journal Le Defenseur de la Constutition was released. Just six pages in he takes a dig at Brissot and Condorcet, questioning their conduct in the aftermath of the Flight to Varennes and Massacre on Champ de Mars the year before. He remarks how these two men ”up until then known for your connections to La Fayette, and for your great moderation; long-time spectators of a semi-aristocratic club (the Society of 1789)” suddenly started waving the word ”republic” around, Condorcet by publishing the treatise De la République, ou Un roi est-il nécessaire à la conservation de la liberté ?, Brissot by founding a journal by the name of Le Républicain, while their friend Duchatêlet put up posters preaching the same ideals on all the walls of Paris. Robespierre considers the timing for this to have been counterproductive at best:

With all the spirits fermented; just as much as the word republic caused division among the patriots, gave the enemies of liberty the pretext they were looking for, to publish that there existed in France a party which conspired against the monarchy and the constitution. They hastened to attribute to this argument the firmness with which we defended in the Constituent Assembly the rights of national sovereignty against the monster of inviolability. It was with this word [republic] that they misled the majority of the Constituent Assembly; it is this word which was the signal for the carnage of peaceful citizens, slaughtered on the altar of the homeland, their whole crime having been to legally exercise the right of petition, enshrined by constitutional laws. Through this name the true friends of liberty were disguised as factious by perverse or ignorant citizens; and the revolution regressed by perhaps half a century.

He also brings up the fact that it was Brissot who had been the author behind the petition that asked for the the removal of the king ”at a time when the faction was only waiting for this pretext to slander the defenders of liberty” which was then presented on the Champ-de-Mars. While Robespierre is quick to underline he doesn’t think the intentions of Brissot or Condorcet were ”as guilty as the events were disastrous,” dismissing the thoughts of other ”patriots” who have suggested the two were secret allies of Lafayette, he also writes that ”I only want to see in their past conduct anything but impolitic sovereignity and profound ineptitude” and warns them that ”anyone who bases ambitious projects on new errors of the monarch, who dares to start civil war, at a time when foreign war is being provoked, would be the greatest enemy of the homeland.” The number also contained a copy of Robespierre’s Réponse to Brissot and Guadet from the month before.

In number 3 of Le Defenseur de la Constitution, which can be dated May 31, Robespierre also published an article by the name of Considerations regarding one of the main causes of our ills, where he attacked Brissot once again, designating him and Condorcet as the most famous leaders of a faction that also included ”other deputies of Bordeaux, such as MM. Guadet, Vergniaux, Gensonné...”(he justified going against his former stance to not focus on individuals by rhetorically asking ”how to reveal the factions, without naming Claudius, or Piso, or Caesar? How to fight the Triumpirs [sic], without attacking Octave, or Antoine or Lepidus?”). For 22 pages, Robespierre examined Brissot’s ”faction,” listing several charges and taking from it three truths:

The first [truth] is that, as members of the legislature, they have violated the rights of the nation, and labored mightily to imperil liberty; the second, that they have employed pernicious maneuvers to deprave the public spirit, and make it deviate towards the principles of despotism and aristocracy; the third, that they have done everything in their way to corrupt patriotic societies, and to make of these necessary channels of public education, instruments of intrigue and faction. […] Justice, common sense, civil and political liberty, you have sacrificed everything to the interest of your ambition and to cowardly vengeance; you had to complain about one of the denounced writings; and you were not ashamed to be accusers, judges and parties at the same time. With your heart full of cruel and vile passions, you invoked the public good and the sacred name of the laws.

Robespierre ends by declaring:

…it seems to me that it has now been proven that your patriotism was neither sustained nor true; that the scattered features, by which it seemed to announce itself, can well fool the eyes of unreflecting men, but not redeem the great faults that you have committed against the nation: that in general they do not relate to the public good and to the cause of the people; but to a system of intrigues, and to the interest of a party. I don't need to know whether it's the court or some other faction you serve; it is enough to see that it is not liberty. It is even clear that your conduct can only promote the triumph of the court; and that it is up to it to take advantage of it. If you are strangers to it, you are not so to any other party. However, any party is harmful to public affairs, and it is in the interest of the nation to stifle it, as it is the duty of each citizen to reveal it.

In the aftermath of the publication of both these numbers, sections with the title Why? (Pourquoi ?) appeared in Le Patriote François, the first in in number 1014 (May 20), the second in number 1032 (June 6). Each paragraph of these sections began with the mantra ”Why do M. Robespierre and his partisans [do this/that]. We don’t know, but [something that implies Robespierre has ulterior motives for doing it].” None of these articles are however signed, so there’s no way to know if Brissot was the author (I have my doubts that would be the case for at least the second article, since Brissot in that case would be referring to himself in third person). Throughout June 1792 we also find other numbers of Patriote Français where Robespierre gets mentioned in hostile terms (number 1035 (June 10), number 1036 (June 11), number 1042 (June 17)).

But on June 28 1792, Brissot and Robespierre were shortly reunited after the former had held a speech at the Jacobins denouncing Lafayette, who on the 16th had written an open letter to the Legislative Assembly where he had suggested shutting down all political clubs in order to retain order.

M. Robespierre: When the danger to liberty is certain, when the enemy of liberty is well known, it is superfluous to speak of a reunion, because this feeling is in all hearts. As for me, I felt that it was in mine from the pleasure that the speech given this morning to the National Assembly by M. Guadet gave me, and from that which I have just experienced by hearing M. Brissot. (Applause.)

The journal La Rocambole des journaux, even claims Robespierre wanted to embrace Brissot once again:

I agree to this with all my heart, replies Robespierrot [sic], and to prove it to you: come here Brissot, let me embrace you; let us think only of crushing Lafayette, and of having him indicted; but first, each citizen must denigrate, tear apart, defame this conspirator with all his power so that before being judged by the national high tribunal, he is condemned in public opinion.

Of course, the reunion didn’t last for long, already a month later, July 29, Robespierre did for the first time openly show his support for overthrowing the king and the Legislative Assembly and replacing them with a convention tasked with carrying out major changes. He also argued that the selfdenying decree he had put forward a year earlier be used again, barring the members of the Legislative Assembly (obviously including Brissot) from sitting in the Convention. The next day, July 30, Le Courrier du Midi reported the following:

The club of 300 legislators was held today, in the former Jacobin barracks, near the club of friends of the constitution. Mr. Isnard has just caused a major split there, by declaring that he was going to denounce MM. Antoine and Roberspierre [sic], former constituent deputies. The latter had declared on the 30th [sic] that the current legislature was incapable of saving national sovereignty, and in the hands of intriguing legislators. Roberspierre [sic] spoke with rare energy; and the club ordered the printing of his speech, fortunately improvised. Mr. Isnard is therefore awaiting this civic harangue, to make his denunciation, tending to send the two constituents to the high court of Orléans: his motion was supported by the tartuffe Brissot, who showed the same commitment. Patriotic deputies left the insidious session and tore up their cards; they came to reveal this cowardly plot to the Jacobins; and the publicity of this uncivil act will undoubtedly cause Isnard and Brissot's project to fail.

During his trial a year later, Brissot claimed to not remember this incident. Regardless, the day right after it, August 1 1792, it was spoken of at length at the Jacobins, with energic attacks being made against Brissot. Robespierre was present at the session but chose not to mention Brissot or Isnard, confining himself to repeating his wish of convening a national convention meant to last for a year. ”This effective way to keep all intriguers away from this constituent assembly seems to this speaker sufficient to save the homeland from the dangers that it owes only to weakness and intrigue.”

The very same day, news of the Brunswick Manifesto begun to sweep through Paris, and before the Brissot and Isnard controversy could get any too drastic follow-ups, it was overshadowed by the Insurrection of August 10 which brought and end to the Legislative Assembly. Two days after the insurrection, August 12, Robespierre began to serve on the Paris Commune. On September 2, during the end of which the so called September massacres began, he is recorded to have done the following during the evening session of said commune:

MM. Billaud-Varenne and Robespierre, developing their civic feelings, paint the deep pain they feel over the current state of France. They denounce to the General Council a plot in favor of the Duke of Brunswick, whom a powerful party wants to bring to the throne of the French.

The next day, Brissot could report the following:

Yesterday, Sunday, I, as well as parts of the deputies of the Gironde, and other equally virtuous men, was denounced at the Paris Commune. We were accused of wishing to hand over France to the Duke of Brunswick, of having received millions from them, and of having concerted ourselves to go to England to save ourselves. Citizens, I was denounced at ten o'clock in the evening, and at the same time they were slaughtering in the prisons… This morning, around seven o'clock, three commissioners of the Commune came to my house… for three hours, they examined, with all possible care, all my papers.

If this had been a naked attempt to get Brissot murdered in prison is hard to know for sure. Historians willing to give Robespierre the benefit of the doubt have suggested he may not have learned of the massacres yet when denouncing Brissot. Though I wouldn’t say his case is much helped by the fact that, when explaining his actions during and attitude towards the massacres in a speech held November 5 1792, he denied he had even been present at the Commune the days before and during them (which is obviously false) as opposed to admitting he had been there and said what he’d said, while asseverating he had not had any evil intentions…

In his Discours de Jérôme Pétion sur l’accusation intentée contre Maximilien Robespierre (November 5 1792) Pétion recounts the following conversation between him and Robespierre which took place just one day after Brissot’s house was searched, and where Robespierre confirms his suspicions regarding Brissot having connections to Brunswick. Like Brissot one year earlier, Pétion too underlines that no personal relationship existed between the latter and Robespierre:

The surveillance Committee launched an arrest warrant against Minister Roland; it was the 4th (September), and the massacres were still going on. Danton was informed of it, he came to the town hall, he was with Robespierre. […] I had an explanation with Robespierre, it was very lively. I still made him face the reproaches that friendship tempered in his absence, I told him: ”Robespierre, you are doing a lot of harm; your denunciations, your alarms, your hatreds, your suspicions, they agitate the people; explain yourself; do you have any facts? do you have proof? I fight with you; I only love the truth; I only want liberty.

”You allow yourself to be surrounded,” [he replied], ”you allow yourself to be warned. You are disposed against me, you see my enemies every day; you see Brissot and his party.”

”You are mistaken, Robespierre; no one is more on guard than I against prejudices, and judges with more coolness, men and things. You’re right, I see Brissot, however rarely, but you don’t know him, and I know him since his childhood. I have seen him in those moments when the whole soul shows itself; where one abandons oneself without reservation to friendship, to trust: I know his disinterestedness; I know these principles, I assure you that they are pure; those who make him a party leader do not have the slightest idea of his character; he has lights and knowledge; but he has neither the reserve, nor the dissimulation, nor these catchy forms, nor this spirit of consistency which constitutes a party leader, and what will surprise you is that, far from leading others, he is very easy to abuse.”

Robespierre insisted, but confined himself to generalities.

”Allow us to explain ourselves, I told him, tell me frankly what’s on your mind, what it is you know.”

”Well!” he replied, ”I believe that Brissot is with Brunswick.”

”What mistake is yours!” I exclaimed. ”It is truly madness; this is how your imagination leads you astray: wouldn't Brunswick be the first to cut his head off? Brissot is not mad enough to doubt it: which of us can seriously capitulate! which of us does not risk his life! Let us banish unjust mistrust.”

Danton became entangled in the colloquy, saying that this was not the time for arguments; that it was necessary to have all these explanations after the expulsion of the enemies; that this decisive object alone should occupy all good citizens.

A little more than two weeks later, September 21, the first session of the National Convention was held. Robespierre and Brissot had both been elected deputies, the former representing Paris, the latter Eure-et-Loi. In the pamphlet J. P. Brissot, député à la Convention nationale, à tous les républicains de France; sur la société des Jacobins de Paris, released less than a month later, Brissot writes that before the opening of said Convention, Danton, in the hopes of sorting out their differences, organized a meeting between the three. But as might be expected, it didn’t bear any fruit…

Before the opening of the National Convention, Danton, trying to bring together what he called the parties, sought me out, and I did not refuse explanations, because I have always had a horror of divisions. I attested to the consideration that I for a long time had held for Robespierre and his faction, although constantly harassed by them. Danton asked me some questions about my republican doctrine; he feared, he said with Robespierre, that I wanted to establish a federative republic, that this was the opinion of Gironde. I reassured him. Robespierre was informed of this, and Robespierre continued to spread the word that I wanted a federal republic.

Just two days after the opening of the Convention, September 23 Chabot came to the Jacobins and announced that in number 1140 of Patriote Français, released the very same day, ”Brissot or his croupier said […] that the Convention appeared to be divided into two distinct parties; one of which is a disorganizing party. This seems to me to be one of the intrigues that people play to keep the deputies sent from the departments to the Convention away from the Jacobins: they will be told that it is in this Society that this disorganizing party resides. […] I therefore denounce this intrigue that seems to me to have been made in order to depopularize Danton, Robespierre and Collot, and I say that, if Brissot does not explain this article in his journal, he is the biggest of scoundrels.” When Brissot hadn’t yet appeared to give an explanation on October 10, the jacobins struck him from their list of members, and other ”girondins” followed suit the very same month.

On September 25, a stormy session played out between girondins and montagnards within the newly opened Convention (as would be the case for almost every session the following time as well), that among other things included Osselin claiming that ”a party of Robespierre” existed within the Convention, Robespierre denying this to be true, saying that ”it was when I loudly demanded the dismissal of Lafayette before the war, that it was said, in these public journals, that I had had conferences with the queen, with Lamballe, and that my resignation as public prosecutor was the result of this infamous transaction; and it was at the same time that a patriotic but inconsiderate writer (Brissot) accused me of aspiring to dictatorship: and it was at the moment when the National Convention was about to begin its work that these miserable imputations were reproduced,” Brissot asking what right there is for issuing arrest warrants against deputies, and Verguiaux developing on this by accusing Robespierre of having implicated him, Brissot, Ducos, Guadet, Condorcet and Lasource in the complot favorable to the duke of Brunswick denounced at the commune on September 2.

On October 29 1792 Brissot released the pamphlet J. P. Brissot, député à la Convention nationale, à tous les républicains de France ; sur la société des Jacobins de Paris where he, after having accused Robespierre of secretly working with the Austrian committee during the Legislative Assembly and hiding out during the Insurrection of August 10, once again came back to what the latter had been up to during September 2:

Robespierre accused me, at the rostrum of the Paris Commune, of having sold France to Brunswick. He had, he said, proof, striking documents. He promised to show them. Readers, do you want to know this striking evidence? Here it is: I got it from Pétion and Danton, to whom Robespierre did not blush to entrust it. Brunswick, he said, would not have entered France if he had not had a deal with the Gironde faction and me to deliver Paris to him. And where was this deal? In Robespierre's head. Without doubt I could refute, with a thousand arguments, this profoundly stupid accusation, were it not profoundly atrocious. I could retort, with advantage, against Robespierre, this pleasant logic, and prove to him, perhaps, with more plausibility that he himself and his accomplices were in concert with the Prussians; but disdaining such an easy victory, I move on to other considerations. And, I ask my readers, what idea should one form of a man who, on a hypothesis, on a reverie, publicly dishonors representatives of the nation, already surrounded by slander and daggers; who delivers them to the people. What will I say to the brigards who took on the name of the people; to the brigards ready to strike, at the sole signal of the first slanderer who presented himself. And it was on September 2 that Robespierre resounded with this slander! It was the day when the surveillance committee, dripping with blood, issued arrest warrants, or rather massacre warrants, against the deputies of Gironde and against me! It was the day when the scoundrels, who triumphed in Paris, piled up their victims at the Abbaye prison, because they had made the Abbaye a butchery, a tomb for their victims...! Yes, Robespierre was obviously either a monster, or the imbecile instrument of monsters. He was accused of aspiring to dictatorship, to the tribunate. His conduct would seem to prove it, if the mediocrity of his means, if the terror of death, which constantly surrounds him, did not keep him from this perilous post: a dictator must include among his risks that of a violent death; and to brave death, you need some courage. Whatever his secret intentions, when I remember all the circumstances which preceded, accompanied or followed the awful day of September 2 [he then spends two pages listing these circumstances] I cannot help but believe that this tragedy was divided into two very different acts; that the massacre of the prisoners was only an accessory to the grand plan; that it covered and was to bring about the execution of a conspiracy formed against the National Assembly, the ministry and the most intrepid defenders of liberty; that its authors lacked only the courage to execute it, and to mount the tribunate on the corpses of Rolland, Guadet, Vergniaux, Gensonné, etc. and on mine... […] ”I know it,” said Robespierre naively one day to a deputy from Gironde who accused him of having ordered the assassinations. ”I know, that neither you nor your friends would have had an aristocrat assassinated.” This trait paints the spirit of the band.

The next part in the reblog.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

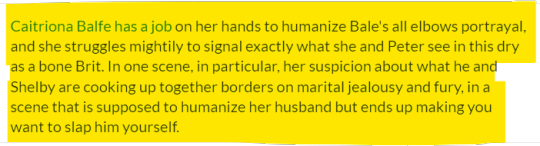

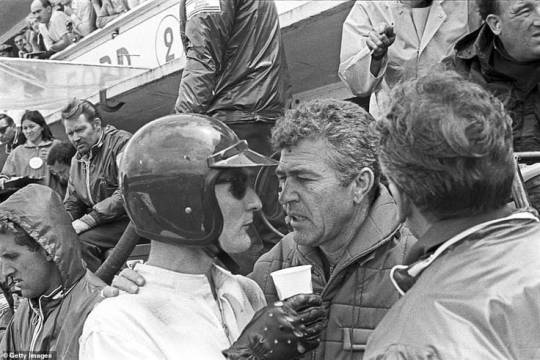

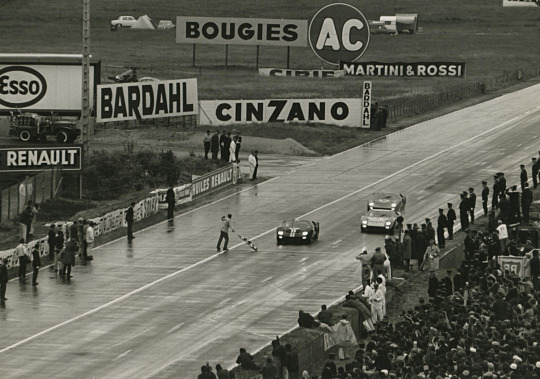

Ken Miles and Carroll Shelby

Pre-grid of the 1966 Le Mans 24-Hour race displays no fewer than eight GT40 Mk II’s primed and prepared to defeat the then-dominant Ferraris, which had won the event nine previous times. Ken Miles’ #1 Ford Shelby GT40 (light blue) is in the foreground.

Ford CEO Henry Ford II and his wife stroll the Le Mans paddock lane before the official start of the 1966 24-Hours of Le Mans. History in the making minute-by-minute, with the seeds of controversy quietly brewing.

Ken Miles shown here leading the 1966 24-Hours of Le Mans in late race wet conditions. He did so definitively in varied conditions, overcoming repeated setbacks. Scorers and mechanics in his paddock report that he was one full lap ahead by the final hour of the race.

Driver Ken Miles (sunglasses) gives an assuring eye to Phil Remington, his legendary co-crew chief, before his final stint in the 1966 24-hours of Le Mans.

Bruce McLaren, shown here trailing Ken Miles on a rainy track in the ’66 Le Mans 24-hour race, is sadly no longer alive to describe his view of how events unfolded.

An historic moment captured. Three Ford GT40 Mk Il’s are orchestrated by Ford to cross the finish line in unison, with Bruce McLaren slightly ahead, notwithstanding that in the final hours of the race the car of Ken Miles/Denny Hulme was leading dominantly — yet obediently slowed in order to achieve the Ford competition director’s order that the three cars cross the finish-line together. With McLaren marginally in the lead, he was awarded the win that rages with controversy to this day.

#carroll shelby#ken miles#Ford GT40 Mk Il#car#cars#ford#ford gt40#gt40#bruce mclaren#Le Mans 24-hour race#le mans#racing#motorsport#24-hour race#Henry Ford II

339 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caitriona Balfe attends the "Le Mans '66" Premiere during the 63rd BFI London Film Festival at the Odeon Luxe Leicester Square on October 10, 2019 in London, England.

59 notes

·

View notes