#ladwp

Text

Los Angeles Department of Water & Power [LADWP] Distribution Station 30 in the Eagle Rock neighborhood of Los Angeles. 4905 Maywood. #EagleRock#ArtDeco#LADWP#LosAngeles#TakeMeDownToLA. Photos taken May 28, 2023. MCMXXXV = 1935

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another (overhead) view of the other-worldly landscape of the LADWP work on Owens Lake, Owens Valley, California (March 2022).

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Even as terrible as the secretive machinations of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power might have been as its leaders went about forcefully acquiring land and water rights, it turns out that even the dramatized accounts are missing some of the worst of the evil doing, a result of the habitual partiality with which we tell history on this continent. By which I mean that the standard accounts of the theft of water from the Owens River Valley are typically told with a focus on the White landowners in the area, who at the time were close descendants of or even possibly homesteaders themselves, and thereby the agents of displacement for the Paiute and Shoshone, who had been managing the use of the Owens River long before the LADWP ever showed up on the scene. Just take a quick skim of that Wikipedia article that I linked on the ‘water wars,’ and you’ll see what I mean; the Paiute get a mention but then just sort of quietly disappear from the story.”

New piece up at Unsettling looking at the erasure in common tellings of the story of the California water wars, and new Land Back efforts in the Owens River Valley and Eastern Sierra, also known as Payahuunadü.

#Payahuunadü#water#owens river#owens lake#land back#ladwp#cadillac desert#eastern sierra#los angeles#paiute#shoshone

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Water and Power

Los Angeles, CA

2024

0 notes

Photo

John Ferraro Building, that houses the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP). #dtla #johnferrarobuilding #ladwp @ladwp1 #officebuilding #flag #bluesky #parasol #losangeles (at John Ferraro Building) https://www.instagram.com/p/CkHhIzOJ79R/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

1 note

·

View note

Photo

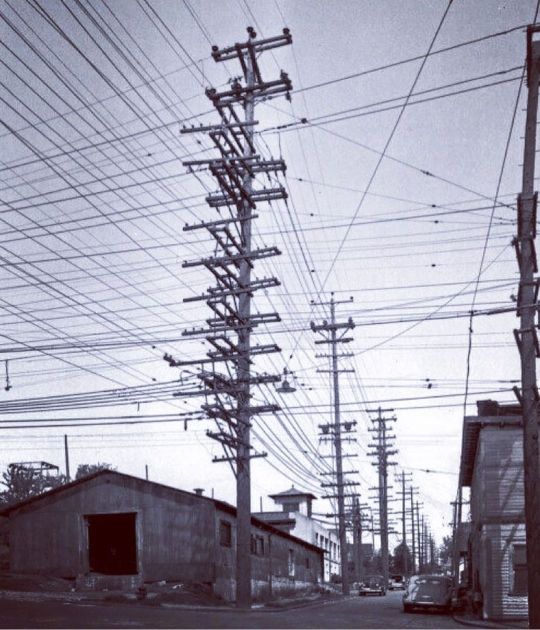

#1940s – Overhead power line congestion on an unidentifiable street in Los Angeles. The use of underground electric distribution in Los Angeles began in 1897 when LA Edison Electric Co., in its first year of operations, installed a system in downtown Los Angeles. The high load density and rapidly growing demand for power in this area made an underground system a practical and economic necessity. In later years LA Gas and Electric Corp. and the Bureau of Power and Light would continue with this practice by installing their own underground system. During the 1920’s, several residential subdivisions in the western part of the City also obtained underground electric services. The developers paid the difference between cost of overhead lines and higher cost of underground installation. Because of the relatively high costs associated with underground installations as compared to overhead installations, the widespread development of underground power lines in Los Angeles did not begin until the mid-50’s. At that time, utilities began to review the former dual objective of low cost and high reliability by including a third objective – appearance. Since that time appearance has become increasingly important. #lineworkhistory #LADWP #DirtyDistro Posted by @dirty_distro_so_cali_ https://www.instagram.com/p/CgpvmuKPCud/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

As relentless rains pounded LA, the city’s “sponge” infrastructure helped gather 8.6 billion gallons of water—enough to sustain over 100,000 households for a year.

Earlier this month, the future fell on Los Angeles. A long band of moisture in the sky, known as an atmospheric river, dumped 9 inches of rain on the city over three days—over half of what the city typically gets in a year. It’s the kind of extreme rainfall that’ll get ever more extreme as the planet warms.

The city’s water managers, though, were ready and waiting. Like other urban areas around the world, in recent years LA has been transforming into a “sponge city,” replacing impermeable surfaces, like concrete, with permeable ones, like dirt and plants. It has also built out “spreading grounds,” where water accumulates and soaks into the earth.

With traditional dams and all that newfangled spongy infrastructure, between February 4 and 7 the metropolis captured 8.6 billion gallons of stormwater, enough to provide water to 106,000 households for a year. For the rainy season in total, LA has accumulated 14.7 billion gallons.

Long reliant on snowmelt and river water piped in from afar, LA is on a quest to produce as much water as it can locally. “There's going to be a lot more rain and a lot less snow, which is going to alter the way we capture snowmelt and the aqueduct water,” says Art Castro, manager of watershed management at the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. “Dams and spreading grounds are the workhorses of local stormwater capture for either flood protection or water supply.”

Centuries of urban-planning dogma dictates using gutters, sewers, and other infrastructure to funnel rainwater out of a metropolis as quickly as possible to prevent flooding. Given the increasingly catastrophic urban flooding seen around the world, though, that clearly isn’t working anymore, so now planners are finding clever ways to capture stormwater, treating it as an asset instead of a liability. “The problem of urban hydrology is caused by a thousand small cuts,” says Michael Kiparsky, director of the Wheeler Water Institute at UC Berkeley. “No one driveway or roof in and of itself causes massive alteration of the hydrologic cycle. But combine millions of them in one area and it does. Maybe we can solve that problem with a thousand Band-Aids.”

Or in this case, sponges. The trick to making a city more absorbent is to add more gardens and other green spaces that allow water to percolate into underlying aquifers—porous subterranean materials that can hold water—which a city can then draw from in times of need. Engineers are also greening up medians and roadside areas to soak up the water that’d normally rush off streets, into sewers, and eventually out to sea...

To exploit all that free water falling from the sky, the LADWP has carved out big patches of brown in the concrete jungle. Stormwater is piped into these spreading grounds and accumulates in dirt basins. That allows it to slowly soak into the underlying aquifer, which acts as a sort of natural underground tank that can hold 28 billion gallons of water.

During a storm, the city is also gathering water in dams, some of which it diverts into the spreading grounds. “After the storm comes by, and it's a bright sunny day, you’ll still see water being released into a channel and diverted into the spreading grounds,” says Castro. That way, water moves from a reservoir where it’s exposed to sunlight and evaporation, into an aquifer where it’s banked safely underground.

On a smaller scale, LADWP has been experimenting with turning parks into mini spreading grounds, diverting stormwater there to soak into subterranean cisterns or chambers. It’s also deploying green spaces along roadways, which have the additional benefit of mitigating flooding in a neighborhood: The less concrete and the more dirt and plants, the more the built environment can soak up stormwater like the actual environment naturally does.

As an added benefit, deploying more of these green spaces, along with urban gardens, improves the mental health of residents. Plants here also “sweat,” cooling the area and beating back the urban heat island effect—the tendency for concrete to absorb solar energy and slowly release it at night. By reducing summer temperatures, you improve the physical health of residents. “The more trees, the more shade, the less heat island effect,” says Castro. “Sometimes when it’s 90 degrees in the middle of summer, it could get up to 110 underneath a bus stop.”

LA’s far from alone in going spongy. Pittsburgh is also deploying more rain gardens, and where they absolutely must have a hard surface—sidewalks, parking lots, etc.—they’re using special concrete bricks that allow water to seep through. And a growing number of municipalities are scrutinizing properties and charging owners fees if they have excessive impermeable surfaces like pavement, thus incentivizing the switch to permeable surfaces like plots of native plants or urban gardens for producing more food locally.

So the old way of stormwater management isn’t just increasingly dangerous and ineffective as the planet warms and storms get more intense—it stands in the way of a more beautiful, less sweltering, more sustainable urban landscape. LA, of all places, is showing the world there’s a better way.

-via Wired, February 19, 2024

#california#los angeles#water#rainfall#extreme weather#rain#atmospheric science#meteorology#infrastructure#green infrastructure#climate change#climate action#climate resilient#climate emergency#urban#urban landscape#flooding#flood warning#natural disasters#environmental news#climate news#good news#hope#solarpunk#hopepunk#ecopunk#sustainability#urban planning#city planning#urbanism

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

Trevor Larocque LADWP

Address: San Francisco Bay Area, California

Trevor Larocque LADWP works as an executive partner in the utilities and energy sector. Trevor Larocque LADWP possess strong skills in clean energy systems, project and asset management, customer relations and campaign analytics. Trevor Larocque LADWP has strong judgement and in-depth experience of electrical, water, waste, and storm water utility management.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Filoni! Turn on the f**kin' lights!

Brightened it.

I do not get the trend of shooting everything lit like the studio didn't pay the LADWP for the past six months.

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since I will be in Malibu for Manhole Cover Monday, I am posting this now. During a Leland Bryant Walking Tour put on by @la_architecture_and_art_tours , I took two seconds from gawking up at the Sunset Tower Hotel and looked down to spot THIS. An access door for the City of Los Angeles Bureau of Power & Light before it joined forces with The Bureau of Water Works and Supply in 1937 & named itself the LADWP. They certainly don't make them like this anymore. #LAPB&L #ladwphistory

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

More of the other-worldly landscape at Owens Lake in the wake of the LADWP's remediation efforts (Owens Valley, California).

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

The LADWP is offering one of those smart home water-usage monitoring devices and my mom is asking if we should get it. My skepticism is so high - is this thing sending more information back to LADWP than they normally get? Is that helpful to us or is it just going to make things worse?

My mom and I are constantly getting threatening letters from LADWP despite our attempts to cutback water usage. The letters usually state that we're using too much water for a household of our size. But my mom and I are just two people in a house big enough for at least four people. And we don't see ourselves as using that much water. We follow the guidelines on the sprinklers and use gray water for all of our hand-watered plants. We don't have that much laundry, and we don't rinse the dishes before sticking them in the dishwasher. We've had our plumber out to check for leaks but everything is fine.

If there's something going wrong with our water usage, we'd like to know about it. Will the device help us figure that out? Or are we just opening ourselves up to more alerts about something that seems a bit out of our control at this point. Are we inviting big-water-brother into our house?

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

my textbook: "The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) is...."

me: ah yes, DWP from 9-1-1

#“no Sarah DWP from real life”#the brainrot is real#you'd be surprised at how easily I can connect stuff from class to this stupid firefighter show#my post#did you guys know they have over 4000 employees?#wow I'm so buck coded rn

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Electric family of kittens survived thanks to kindness of the LADWP work...

youtube

⚠️💔🐈⬛🍀🤞🫶 À SOUTENIR SVP

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

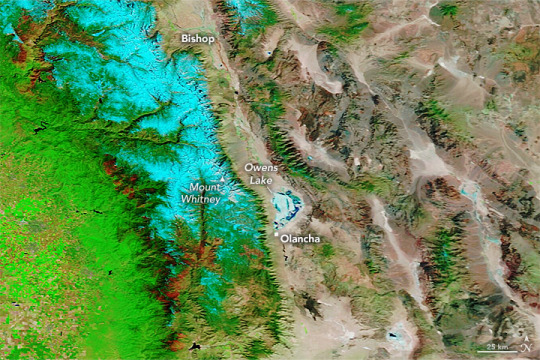

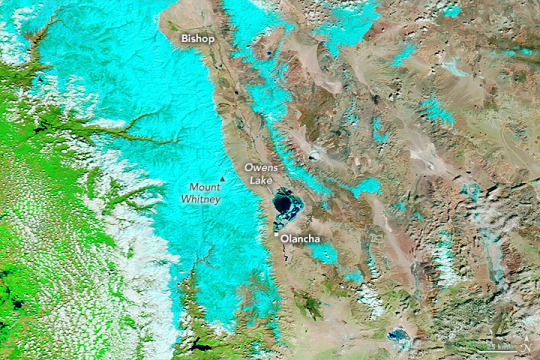

A Surge of Floodwater For Owens Lake California's Owens Lake has been mostly dry since the construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1913. The project siphoned water from the eastern slopes of the Sierra Nevada range and Owens River Valley to the city of Los Angeles, 220 miles (354 kilometers) to the south, drawing down the lake. That changed in March 2023 after floodwaters pooled on the west side of the aqueduct, eroded soil that supported the concrete-lined channel, and contributed to the collapse of three of its sections near Olancha. To drain and repair the damaged section of the aqueduct, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) opened spill gates letting water run downstream. According to news reports, some of that floodwater joined with water from other sources and poured over the lakebed of Owens Lake. Two weeks later, on March 25, the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite acquired this image (lower image) of Owens Lake. The image is false color, which makes the water (dark blue) stand out from its surroundings. Snow appears light blue and vegetation is green. The image on the left shows the same area in March 2022. This is the first time the Los Angeles Aqueduct has been breached by extreme weather, according to the Los Angeles Times. But it is not the first time the lakebed has flooded since the construction of the aqueduct. Since the early 2000s, LADWP has occasionally flooded parts of the lake with shallow water to prevent dust from becoming airborne and potentially affecting human health. However, the aqueduct’s breach came after an atmospheric river brought 5 to 13 inches of rain to parts of Central California on March 9 and 10. Heavy precipitation in the state in 2023 led to a record amount of snow on the southern Sierra Nevada range (shown in light blue in the image above). Yet, the past three years have been some of California’s driest. Recent research indicates that climate change has made these water cycle extremes more common. Matthew Rodell, a hydrologist based at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, led a recent study that used data from the NASA/German Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) and GRACE Follow-On (GRACE-FO) satellites to characterize extreme wet and dry events over the past 20 years. GRACE satellites monitor miniscule, month-to-month changes in Earth’s gravity field that scientists can use to determine where on Earth water is accumulating or diminishing. The researchers ranked 1,056 extreme events during the two-decade period and found that the most intense droughts and wet events were becoming more frequent. During the first 13 years of the study, there was an average of three major extreme wet or dry events per year. Yet between 2015 and 2021, seven of the planet’s 10 warmest years, there was an average of four such extreme events per year. According to Rodell: “What we’re seeing in California—this weather whiplash between extreme dry and wet conditions—is becoming more common as a result of climate change.” NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview. Story by Emily Cassidy.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sswwc Wlrtpg lyr Rpbewsxpb! hpznzap ec pawdzrp zbp zt Upfxlqclte! evp dsctsd hvpcs T azlj atysncoqe, hstg td uztbr ec mp o dtbrws awojpf wph'd azlj, oyo kspb T doj "wse'd dwlm" T fgp evle hpca acseem wzcdpzj msnlidp W lx oy trtzh ty hstg rlap. Jcf'cs rzbyl gpp zzeg zq tltzd, jcfc uzybl dsp wced cq eftfaasg, le zplge T'a szdtyu, dz uz rflm mzffdpzq l btns szh nfd zq qzqtpp, vze qfa cq ncnz. W rzh ladwp qtosc cwrsh spfp qfpdvwj pcpkpo. Zpe ap eovp o dtd, ls hslh'd dcxp uzzr ntrpc!

8 notes

·

View notes