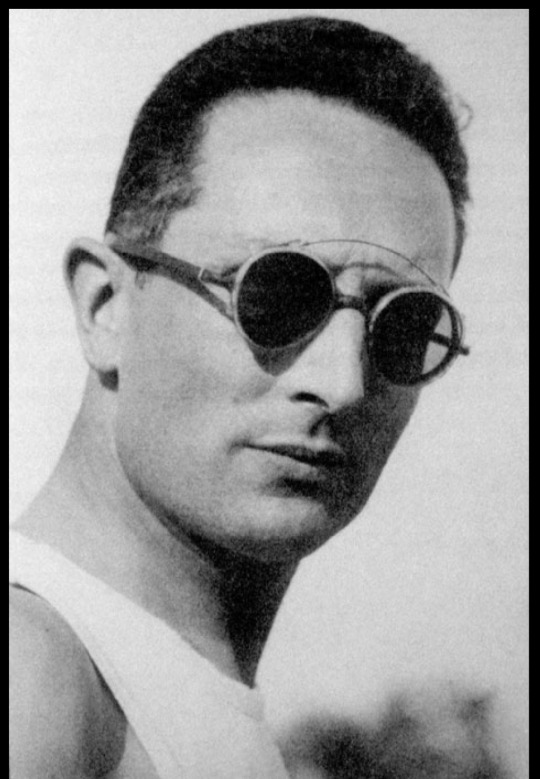

#jacques guérin

Text

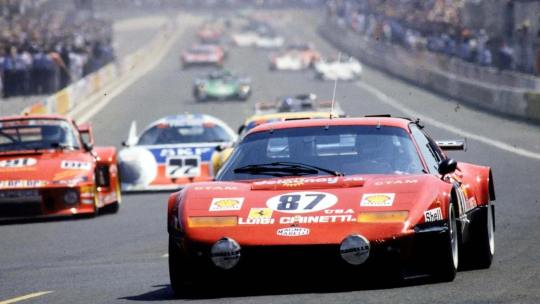

La Ferrari 512 BB Compétition-Luigi Chinetti Sr de Jacques Guérin, Jean-Pierre Delauney & Gregg Young aux 24 Heures du Mans 1978. - source Motor Authorithy.

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

non-exhaustive list of sources that are imo especially interesting/thought-provoking, just really solid, or otherwise a personal favorite:

MISC

“Leaders and Martyrs: Codreanu, Mosley and José Antonio,” Stephen M. Cullen (1986)

“Bureaucratic Politics in Radical Military Regimes,” Gregory J. Kasza (1987)

A History of Fascism, 1914–1945, Stanley Payne (1996)

The Fascist Revolution: Toward a General Theory of Fascism, George L. Mosse (1999)

Fascism Outside Europe: The European Impulse against Domestic Conditions in the Diffusion of Global Fascism, ed. Stein U. Larsen (2001)

Ancient Religions, Modern Politics: The Islamic Case in Comparative Perspective, Michael Cook (2014)

MARXISM

“Crisis and the Way Out: The Rise of Fascism in Italy and Germany,” Mihály Vajda (1972)

“Austro-Marxist Interpretation of Fascism,” Gerhard Botz (1976)

“Fascism: some common misconceptions,” Noel Ignatin (1978)

“Gramsci’s Interpretation of Fascism,” Walter L. Adamson (1980)

ARGENTINA

“The Ideological Origins of Right and Left Nationalism in Argentina, 1930–43,” Alberto Spektorowski (1994)

“The Making of an Argentine Fascist. Leopoldo Lugones: From Revolutionary Left to Radical Nationalism,” Alberto Spektorowski (1996)

“Argentine Nacionalismo before Perón: The Case of the Alianza de la Juventud Nacionalista, 1937–c. 1943,” Marcus Klein (2001)

BRAZIL

“Tenentismo in the Brazilian Revolution of 1930,” John D. Wirth (1964)

“Ação Integralista Brasileira: Fascism in Brazil, 1932–1938,” Stanley E. Hilton (1972)

“Integralism and the Brazilian Catholic Church,” Margaret Todaro Williams (1974)

“Ideology and Diplomacy: Italian Fascism and Brazil (1935–1938),” Ricardo Silva Seitenfus (1984)

“The corporatist thought in Miguel Reale: readings of Italian fascism in Brazilian integralismo,” João Fábio Bertonha (2013)

CHILE

“Corporatism and Functionalism in Modern Chilean Politics,” Paul W. Drake (1978)

“Nationalist Movements and Fascist Ideology in Chile,” Jean Grugel (1985)

“A Case of Non-European Fascism: Chilean National Socialism in the 1930s,” Mario Sznajder (1993)

CHINA

Revolutionary Nativism: Fascism and Culture in China, 1925–1937, Maggie Clinton (2017)

CROATIA

“An Authoritarian Parliament: The Croatian State Sabor of 1942,” Yeshayahu Jelinek (1980)

“The End of “Historical-Ideological Bedazzlement”: Cold War Politics and Émigré Croatian Separatist Violence, 1950–1980,” Mate Nikola Tokić (2012)

EGYPT

“An Interpretation of Nasserism,” Willard Range (1959)

Egypt’s Young Rebels: “Young Egypt,” 1933–1952, James P. Jankowski (1975)

“The Use of the Pharaonic Past in Modern Egyptian Nationalism,” Michael Wood (1998)

FRANCE

“Mores, “The First National Socialist”,” Robert F. Byrnes (1950)

“The Political Transition of Jacques Doriot,” Gilbert D. Allardyce (1966)

“National Socialism and Antisemitism: The Case of Maurice Barrès,” Zeev Sternhell (1973)

“Georges Valois and the Faisceau: The Making and Breaking of a Fascist,” Jules Levey (1973)

“The Condottieri of the Collaboration: Mouvement Social Révolutionnaire,” Bertram M. Gordon (1975)

“Myth and Violence: The Fascism of Julius Evola and Alain de Benoist,” Thomas Sheehan (1981)

GERMANY

“A German Racial Revolution?” Milan L. Hauner (1984)

“Abortion and Eugenics in Nazi Germany,” Henry P. David, Jochen Fleischhacker, and Charlotte Höhn (1988)

“Nietzschean Socialism — Left and Right, 1890–1933,” Steven E. Aschheim (1988)

The Brown Plague: Travels in Late Weimar and Early Nazi Germany, Daniel Guérin, tr. Robert Schwartzwald (1994)

“Hitler and the Uniqueness of Nazism,” Ian Kershaw (2004)

HAITI

“Ideology and Political Protest in Haiti, 1930–1946,” David Nicholls (1974)

“Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s State Against Nation: A Critique of the Totalitarian Paradigm,” Robert Fatton, Jr. (2013)

IRAN

“Iran’s Islamic Revolution in Comparative Perspective,” Said Amir Arjomand (1986)

IRAQ

“Arab-Kurdish Rivalries in Iraq,” Lettie M. Wenner (1963)

“From Paper State to Caliphate: The Ideology of the Islamic State,” Cole Bunzel (2015)

“Iraqi Archives and the Failure of Saddam’s Worldview in 2003,” Samuel Helfont (2023)

ISRAEL

“The Emergence of the Israeli Radical Right,” Ehud Sprinzak (1989)

“Max Nordau, Liberalism and the New Jew,” George L. Mosse (1992)

The Stern Gang: Ideology, Politics and Terror, 1940–1949, Joseph Heller (1995)

““Hebrew” Culture: The Shared Foundations of Ratosh’s Ideology and Poetry,” Elliott Rabin (1999)

“Israel’s fascist sideshow takes center stage,” Natasha Roth-Rowland (2019)

“‘Frightening proportions’: On Meir Kahane’s assimilation doctrine,” Erik Magnusson (2021)

ITALY

“The Fascist Conception of Law,” H. Arthur Steiner (1936)

“The Goals of Italian Fascism,” Edward R. Tannenbaum (1969)

“Fascist Modernization in Italy: Traditional or Revolutionary?” Roland Sarti (1970)

“Fascism as Political Religion,” Emilio Gentile (1990)

“I redentori della vittoria: On Fiume’s Place in the Genealogy of Fascism,” Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht (1996)

JAPAN

“A New Look at the Problem of “Japanese Fascism”,” George M. Wilson (1968)

“Marxism and National Socialism in Taishō Japan: The Thought of Takabatake Motoyuki,” Germaine A. Hoston (1984)

“Fascism from Below? A Comparative Perspective on the Japanese Right, 1931–1936,” Gregory J. Kasza (1984)

“Japan’s Wartime Labor Policy: A Search for Method,” Ernest J. Notar (1985)

“Fascism from Above? Japan’s Kakushin Right in Comparative Perspective,” Gregory J. Kasza (2001)

PARAGUAY

“Political Aspects of the Paraguayan Revolution, 1936–1940,” Harris Gaylord Warren (1950)

“Toward a Weberian Characterization of the Stroessner Regime in Paraguay (1954–1989),” Marcial Antonio Riquelme (1994)

ROMANIA

“The Men of the Archangel,” Eugen Weber (1966)

“Breaking the Teeth of Time: Mythical Time and the “Terror of History” in the Rhetoric of the Legionary Movement in Interwar Romania,” Raul Carstocea (2015)

RUSSIA

“Was There a Russian Fascism? The Union of Russian People,” Hans Rogger (1964)

“The All-Russian Fascist Party,” Erwin Oberländer (1966)

“The Zhirinovsky Threat,” Jacob W. Kipp (1994)

Russian Fascism: Traditions, Tendencies, Movements, Stephen Shenfield (2000)

“Why fascists took over the Reichstag but have not captured the Kremlin: a comparison of Weimar Germany and post-Soviet Russia,” Steffen Kailitz and Andreas Umland (2017)

SLOVAKIA

“Storm-troopers in Slovakia: the Rodobrana and the Hlinka Guard,” Yeshayahu Jelinek (1971)

SPAIN

“The Forgotten Falangist: Ernesto Gimenez Cabellero,” Douglas W. Foard (1975)

Fascism in Spain, 1923–1977, Stanley Payne (1999)

“Spanish Fascism as a Political Religion (1931–1941),” Zira Box and Ismael Saz (2011)

SYRIA

The Ba‘th and the Creation of Modern Syria, David Roberts (1987)

TURKEY

“Kemalist Authoritarianism and fascist Trends in Turkey during the Interwar Period,” Fikret Adanïr (2001)

“The Other From Within: Pan-Turkist Mythmaking and the Expulsion of the Turkish Left,” Gregory A. Burris (2007)

“The Racist Critics of Atatürk and Kemalism, from the 1930s to the 1960s,” İlker Aytürk (2011)

UNITED KINGDOM

“Northern Ireland and British fascism in the inter-war years,” James Loughlin (1995)

“‘What’s the Big Idea?’: Oswald Mosley, the British Union of Fascists and Generic Fascism,” Gary Love (2007)

“Why Fascism? Sir Oswald Mosley and the Conception of the British Union of Fascists,” Matthew Worley (2011)

UNITED STATES

“Ezra Pound and American Fascism,” Victor C. Ferkiss (1955)

“Populist Influences on American Fascism,” Victor C. Ferkiss (1957)

“Vigilante Fascism: The Black Legion as an American Hybrid,” Peter H. Amann (1983)

“Silver Shirts in the Northwest: Politics, Personalities, and Prophecies in the 1930s,” Eckard V. Toy, Jr. (1989)

“Women in the 1920s’ Ku Klux Klan Movement,” Kathleen M. Blee (1991)

“‘Leaderless Resistance’,” Jeffrey Kaplan (1997)

“The post-war paths of occult national socialism: from Rockwell and Madole to Manson,” Jeffrey Kaplan (2001)

“The Upward Path: Palingenesis, Political Religion and the National Alliance,” Martin Durham (2004)

“The F Word: Is Donald Trump a fascist?” Dylan Matthews (2021)

“Castizo Futurism and the Contradictions of Multiracial White Nationalism,” Ben Lorber and Natalie Li (2022)

#this is not The Masterpost this has just emerged along the way#and there's definitely plenty that could go here that aren't bc i just got tired of listing them#i need somewhere and preferably multiple places to put sources so i feel like ive accomplished something when i finish reading them lol

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

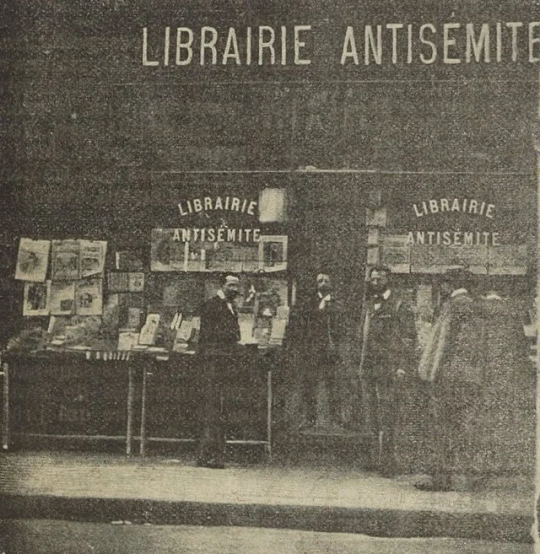

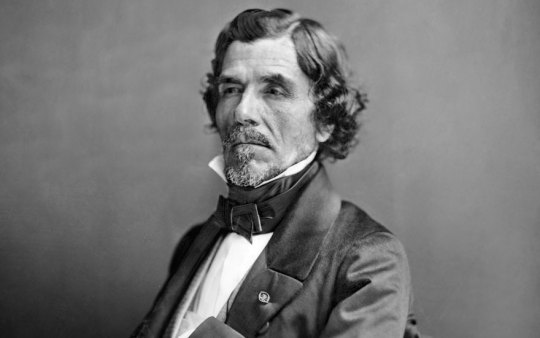

"Librería antisemita" de Charles-Henri Devos en el número 45 de la calle V

Charles Devos (1864-1931) trabajó con el infame activista antisemita Édouard Drumont en la década de 1890, administrando el periódico de Drumont La Libre Parole , gestionando la contabilidad y las suscripciones. Pronto se convirtió en administrador de este periódico, además de gestionar la Librairie antisemita aquí representada.

Su influencia en el movimiento antisemita francés creció cada vez más, hasta que se convirtió en presidente de la Liga Nacional Antijudía en 1903.

Tanto el pro-Dreyfus Jacques Prolo como el anti-Dreyfus Jules Guérin acusaron a Devos de malversar dinero de La Lbire Parole ; El historiador Bertrand Joly describió a Devos como un "administrador dudoso" y lo situó entre los "delincuentes" del nacionalismo francés anti-Dreyfus.

El final del caso Dreyfus no frenó la carrera de Devos: abandonó La Mibre Parole y, en 1917, fundó su agencia de publicidad.

En 1919 fue elegido miembro del Ayuntamiento de Garches, convirtiéndose en alcalde en 1925. Recibió la Legión de Honor en 1929 por sus 36 años de carrera en la prensa y la política. Fue apoyado por la conservadora Federación Republicana .

Tras su muerte en 1931, se le dio su nombre a una plaza de la ciudad; además, el Marqués de Morès hizo poner su nombre a una calle y a un camino. Estos tres nombres de carreteras se cambiaron en 2022, ya que ambos hombres eran conocidos e infames activistas antisemitas, y se cambiaron en honor a Simone Veil, Marie Curie y Lucie Aubrac.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blanche, Marguerite, and Queenship

Blanche's actions as queen dowager amount to no more than those of her grandmother and great-grandmother. A wise and experienced mother of a king was expected to advise him. She would intercede with him, and would thus be a natural focus of diplomatic activity. Popes, great Churchmen and great laymen would expect to influence the king or gain favour with him through her; thus popes like Gregory IX and Innocent IV, and great princes like Raymond VII of Toulouse, addressed themselves to Blanche. She would be expected to mediate at court. She had the royal authority to intervene in crises to maintain the governance of the realm, as Blanche did during Louis's near-fatal illness in 1244-5, and as Eleanor did in England in 1192.

In short, Blanche's activities after Louis's minority were no more and no less "co-rule" than those of other queen dowagers. No king could rule on his own. All kings- even Philip Augustus- relied heavily on those they trusted for advice, and often for executive action. William the Breton described Brother Guérin as "quasi secundus a rege"- "as if second to the king": indeed, Jacques Krynen characterised Philip and his administrators as almost co-governors. The vastness of their realms forced the Angevin kings to rely even more on the governance of others, including their mothers and their wives. Blanche's prominent role depended on the consent of her son. Louis trusted her judgement. He may also have found many of the demands of ruling uncongenial. Blanche certainly had her detractors at court, but she was probably criticsed, not for playing a role in the execution of government, but for influencing her son in one direction by those who hoped to influence him in another.

The death of a king meant that there was often more than one queen. Blanche herself did not have to deal with an active dowager queen: Ingeborg lived on the edges of court and political life; besides, she was not Louis VIII's mother. Eleanor of Aquitaine did not have to deal with a forceful young queen: Berengaria of Navarre, like Ingeborg, was retiring; Isabella of Angoulême was still a child. But the potential problem of two crowned, anointed and politically engaged queens is made manifest in the relationship between Blanche and St Louis's queen, Margaret of Provence.

At her marriage in 1234 Margaret of Provence was too young to play an active role as queen. The household accounts of 1239 still distinguish between the queen, by which they mean Blanche, and the young queen — Margaret. By 1241 Margaret had decided that she should play the role expected of a reigning queen. She was almost certainly engaging in diplomacy over the continental Angevin territories with her sister, Queen Eleanor of England. Churchmen loyal to Blanche, presumably at the older queen’s behest, put a stop to that. It was Blanche rather than Margaret who took the initiative in the crisis of 1245. Although Margaret accompanied the court on the great expedition to Saumur for the knighting of Alphonse in 1241, it was Blanche who headed the queen’s table, as if she, not Margaret, were queen consort. In the Sainte-Chapelle, Blanche of Castile’s queenship is signified by a blatant scattering of the castles of Castile: the pales of Provence are absent.

Margaret was courageous and spirited. When Louis was captured on Crusade, she kept her nerve and steadied that of the demoralised Crusaders, organised the payment of his ransom and the defence of Damietta, in spite of the fact that she had given birth to a son a few days previously. She reacted with quick-witted bravery when fire engulfed her cabin, and she accepted the dangers and discomforts of the Crusade with grace and good humour. But her attempt to work towards peace between her husband and her brother-in-law, Henry III, in 1241 lost her the trust of Louis and his close advisers — Blanche, of course, was the closest of them all - and that trust was never regained. That distrust was apparent in 1261, when Louis reorganised the household. There were draconian checks on Margaret's expenditure and almsgiving. She was not to receive gifts, nor to give orders to royal baillis or prévôts, or to undertake building works without the permission of the king. Her choice of members of her household was also subject to his agreement.

Margaret survived her husband by some thirty years, so that she herself was queen mother, to Philip III, and was still a presence ar court during the reign of her grandson Philip IV. But Louis did not make her regent on his second, and fatal, Crusade in 1270. In the early 12605 Margarer tried to persuade her young son, the future Philip III, to agree to obey her until he was thirty. When Philip told his father, Louis was horrified. In a strange echo of the events of 1241, he forced Philip to resile from his oath to his mother, and forced Margaret to agree never again to attempt such a move. Margaret had overplayed her hand. It meant that she was specifically prevented from acting with those full and legitimate powers of a crowned queen after the death of her husband that Blanche, like Eleanor of Aquitaine, had been able to deploy for the good of the realm.

Why was Margaret treated so differently from Blanche? Were attitudes to the power of women changing? Not yet. In 1294 Philip IV was prepared to name his queen, Joanna of Champagne-Navarre, as sole regent with full regal powers in the event of his son's succession as a minor. She conducted diplomatic negotiations for him. He often associated her with his kingship in his acts. And Philip IV wanted Joanna buried among the kings of France at Saint-Denis - though she herself chose burial with the Paris Franciscans. The effectiveness and evident importance to their husbands of Eleanor of Provence and Eleanor of Castile in England led David Carpenter to characterise late thirteenth-century England as a period of ‘resurgence in queenship’.

The problem for Margaret was personal, rather than institutional. Blanche had had her detractors at court. It is not clear who they were. There were always factions at courts, not least one that centred around Margaret, and anyone who had influence over a king would have detractors. They might have been clerks with misgivings about women in general, and powerful women in particular, and there may have been others who believed that the power of a queen should be curtailed, No one did curtail Blanche's — far from it. By the late chirteenth century the Capetian family were commissioning and promoting accounts of Louis IX that praise not just her firm and just rule as regent, but also her role as adviser and counsellor — her continuing influence — during his personal rule. As William of Saint-Pathus put it, because she was such a ‘sage et preude femme’, Louis always wanted ‘sa presence et son conseil’. But where Blanche was seen as the wisest and best provider of good advice that a king could have, a queen whose advice would always be for the good of the king and his realm, Margaret was seen by Louis as a queen at the centre of intrigue, whose advice would not be disinterested.

Surprisingly, such formidable policical players at the English court as Simon de Montfort and her nephew, the future Edward I, felt that it was worthwhile to do diplomatic business through Margaret. Initially, Henry III and Simon de Montfort chose Margaret, not Louis, to arbitrate between them. She was a more active diplomat than Joinville and the Lives of Louis suggest, and probably, where her aims coincided with her husband’s, quite effective.

To an extent the difference between Blanche’s and Margaret’s position and influence simply reflected political reality. Blanche was accused of sending rich gifts to her family in Spain, and advancing them within the court. But there was no danger that her cultivation of Castilian family connections could damage the interests of the Capetian realm. Margaret’s Provençal connections could. Her sister Eleanor was married to Henry III of England. Margaret and Eleanor undoubtedly attempted to bring about a rapprochement between the two kings. This was helpful once Louis himself had decided to come to an agreement with Henry in the late 1250s, but was perceived as meddlesome plotting in the 1240s. Moreover, Margaret’s sister Sanchia was married to Henry's younger brother, Richard of Cornwall, who claimed the county of Poitou, and her youngest sister, Beatrice, countess of Provence, was married to Charles of Anjou. Sanchia’s interests were in direct conflict with those of Alphonse of Poitiers; and Margaret herself felt that she had dowry claims in Provence, and alienated Charles by attempting to pursue them. Indeed, her ill-fated attempt to tie her son Philip to her included clauses that he would not ally himself with Charles of Anjou against her.

Lindy Grant- Blanche of Castile, Queen of France

#xiii#lindy grant#blanche of castile queen of france#blanche de castille#grégoire ix#innocent iv#raymond vii de toulouse#aliénor d'aquitaine#louis ix#philippe ii#guérin#louis viii#marguerite de provence#aliénor de provence#alphonse de poitiers#henry iii of england#philippe iii#jeanne i de navarre#philippe iv#simon de montfort#edward i of england#jean de joinville#sancia de provence#béatrice de provence#charles i d'anjou

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mai MMXXIV

Films

Les Trois Jours du Condor (Three Days of the Condor) (1975) de Sydney Pollack avec Robert Redford, Faye Dunaway, Cliff Robertson, Max von Sydow, John Houseman, Addison Powell, Walter McGinn et Tina Chen

La Loi du silence (I Confess) (1953) d'Alfred Hitchcock avec Montgomery Clift, Anne Baxter, Karl Malden, Brian Aherne, Roger Dann, Charles Andre, O.E. Hasse et Dolly Haas

Bon Voyage (2003) de Jean-Paul Rappeneau avec Isabelle Adjani, Virginie Ledoyen, Yvan Attal, Grégori Derangère, Gérard Depardieu, Peter Coyote, Jean-Marc Stehlé et Aurore Clément

Complot de famille (Family Plot) (1976) d'Alfred Hitchcock avec Bruce Dern, William Devane, Barbara Harris, Karen Black, Ed Lauter, Cathleen Nesbitt et Katherine Helmond

Elvis: That's the Way It Is (1970) de Denis Sanders avec Elvis Presley, Richard Davis, Sammy Davis, Jr, Joe Esposito, Felton Jarvis et Red West

Reivers (The Reivers) (1969) de Mark Rydell avec Steve McQueen, Sharon Farrell, Will Geer, Rupert Crosse, Mitch Vogel, Juano Hernández, Michael Constantine, Burgess Meredith et Diane Ladd

La Belle Espionne (Sea Devils) (1953) de Raoul Walsh avec Yvonne De Carlo, Rock Hudson, Maxwell Reed, Denis O'Dea, Michael Goodliffe, Bryan Forbes, Jacques Brunius et Gérard Oury

L'assassin habite au 21 (1942) de Henri-Georges Clouzot avec Pierre Fresnay, Suzy Delair, Jean Tissier, Pierre Larquey, Noël Roquevert, Odette Talazac, Marc Natol et Louis Florencie

Une aussi longue absence (1961) de Henri Colpi avec Alida Valli, Georges Wilson, Charles Blavette, Amédée, Jacques Harden, Paul Faivre, Catherine Fonteney et Diane Lepvrier

Le Procès Goldman (2023) de Cédric Kahn avec Arieh Worthalter, Arthur Harari, Stéphan Guérin-Tillié, Nicolas Briançon, René Garaud, Aurélien Chaussade, Christian Mazucchini, Jeremy Lewin, Jerzy Radziwiłowicz et Chloé Lecerf

La Vendetta (1962) de Jean Chérasse avec Louis de Funès, Francis Blanche, Marisa Merlini, Olivier Hussenot, Jean Lefebvre, Rosy Varte, Jean Houbé et Christian Mery

Messieurs les Ronds de Cuir (1978) de et avec Daniel Ceccaldi et Claude Dauphin, Raymond Pellegrin, Evelyne Buyle, Roger Carel, Roland Armontel, Bernard Le Coq, Jean-Marc Thibault et Michel Robin

Marcello mio (2024) de Christophe Honoré avec Chiara Mastroianni, Catherine Deneuve, Nicole Garcia, Fabrice Luchini, Benjamin Biolay et Melvil Poupaud

Opération Opium (Poppies Are Also Flowers) (1966) de Terence Young avec E. G. Marshall, Trevor Howard, Angie Dickinson, Gilbert Roland, Yul Brynner, Eli Wallach, Georges Géret, Marcello Mastroianni et Anthony Quayle

Viva Maria ! (1965) de Louis Malle avec Brigitte Bardot, Jeanne Moreau, Paulette Dubost, George Hamilton, Claudio Brook, Carlos López Moctezuma et Gregor von Rezzori

Séries

Kaamelott Livre V

Le Phare

Maguy Saison 4

Retour de France - Retour à l'occase départ - Rimes et châtiment - Fugue en elle mineure - Mise aux poings - Vote voltige - St Vincent de Pierre - Courant d'hertz - Un médium et une femme - Retrouvailles, que vaille ! - Parrain artificiel - Infarctus et coutumes - Soupçons et lumières - Dakar, pas Dakar - Impair Noël - Maguy Antoinette - Otages dans le potage - Piqûres de mystique - Nécropole et Virginie - Nitro, ni trop peu - Assassin-glinglin - Le nippon des soupirs - Pas de deux en mêlée - Main basse sur Bretteville - Ski m'aime me suive - Des plaies et des brosses - Polar ménager - Une faim de look - Le bronzage de Pierre - Transport-à porte - En chantier de vous connaître - La fête défaite - Câblé en herbe - L'enjeu de la vérité - Déformation permanente - En deux tanks, trois mouvements - Postes à galère - Prince-moi, je rêve - Science friction - Démission impossible - Lis tes ratures ! - L'infâme de lettres

Affaires sensibles

Apollo 13 : Les naufragés de l’espace - La vraie arrestation du faux Xavier Dupont de Ligonnès - L'assaut sur le Capitole - Trésor de Lava : embrouilles corses - Secte, clonage et soucoupes volantes : voyage aux frontières du Raël - Ils ont enlevé Fangio ! - Guerre du Golfe et fake news - "The Crown", une série royale ou la royauté selon Netflix - La catastrophe de Beaune - Concorde, la Lune et l'ovni - USA-URSS 1972, Guerre Froide sur parquet - Amityville : 28 jours avec le diable - L'affaire Athanor - Coupe du monde 1966, les Nord-Coréens sortent du vestiaire - La véritable histoire de Rabbi Jacob

Coffre à Catch

#155 : Les débuts historiques de Sheamus ! - Hors-série : WWE One Night Stand 2007 - #51 : Randy Orton ≥ Charles Ingalls - #50 : Tommy Dreamer, représentant Decathlon et Jean-Louis David - #52 : Lashley Récupère son Titre ! - #53 : RIP Vince McMahon - #54 : Qui a fait exploser la bagnole de Vince ? - #55 : JOHN CENA EST DANS LA CE-PLA ! - #56 : Le Poison du Catch vu par CM Punk & John Morrison - Hors-série : ECW December to Dismember - #166 : William Regal : un maître du micro !" - #167: Buckle up, Teddy: Chris Agius nous parle de Backlash 2024 ! - #168 : L'épisode des 1000 likes + Tony Atlas" - #169 : Tiffany est de retour et William Regal est fabuleux!

La croisière s'amuse Saison 5

Merci, je ne joue plus - Le Parfait Ex-amour - Enfin libre - L'amour n'est pas interdit - L'amour n'est pas la guerre - La Fête en bateau : première partie - La Fête en bateau : deuxième partie - Une expérience inoubliable : première partie - L'Amour de ses rêves - Les Victimes - Vive papa ! - L'Amour programmé - Ça, c'est une fête ! - Que dire de l'amour ?

The Hour Saison 1

Une heure, une équipe - Une heure de vérité - Une heure, une tentation - Une heure sous haute tension - L'heure de la révolte - Une heure qui change tout

Castle Saison 5, 6

Le Facteur humain - Jeu de dupes - Valkyrie - Secret défense - Pas de bol, y a école ! - Sa plus grande fan - L'avenir nous le dira - Tout un symbole - Tel père, telle fille - Le meurtre est éternel - L'Élève et le Maître - Le Bon, la Brute et le Bébé

Commissaire Moulin Saison 1

Choc en retour - L'Évadé - Marée basse

Totally Spies Saison 5, 6, 7

Totally Mystère ! - Totalement Versailles : première partie - Totalement Versailles : deuxième partie - Pandapocalypse - Quand c'est trop, c'est Troll !

Meurtres au paradis Saison 13

Face à face - Le troisième passager

Doctor Who Season 1

Space Babies - The Devil's Chord - Boom - 73 Yards

Commissaire Dupin

Le trésor d'Ys

Spectacles

WWE Backlash France (2024) à la LDLC Arena de Lyon-Décines

Chocolat Show ! (2007) avec Olivia Ruiz

Les Faux British (2024) de Henry Lewis et Henry Shields avec Francis Huster, Cristiana Reali, Gwen Aduh, Aurélie de Cazanove, Renaud Castel, Lionel Laget, Jean-Marie Lecoq et Miren Pradier

Jamiroquai : Live in Verona (2002)

David Bowie : Glass Spider Tour (1987)

Livres

Détective Conan, tome 22 de Gôshô Aoyama

Dis-moi ton fantasme de Léa Celle qui aimait

Kaamelott, tome 5 : Le Serpent Géant du Lac de l'Ombre d'Alexandre Astier, Steven Dupré et Benoît Bekaert

Une enquête du commissaire Dupin : Péril en mer d'Iroise de Jean-Luc Bannalec

1 note

·

View note

Text

Les Jours heureux (2023)

Days of happinessJahr: 2023

Genre: Drama

Regie: Chloé Robichaud

Hauptrollen: Sophie Desmarais, Vincent Leclerc, Sylvain Marcel, Christian Paul, Yves Jacques, Katherine Levac, Geneviève Alarie, Nour Belkhiria, Maude Guérin, Marco Ledezma, Joseph Antaki, Luis Bertrand, Alain Dahan …

Filmbeschreibung: Emma, eine talentierte Dirigentin und aufstrebender Star auf der Bühne in Montreal, hat eine…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

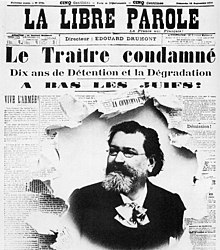

425) Ligue antisémitique de France, Antisemitic League of France, Francuska Liga Antysemicka - została założona w 1889 roku przez dziennikarza Edouarda Drumonta, przy wsparciu innych prawicowych francuskich antysemitów, takich jak Jacques de Biez, Albert Millot i markiz de Morès. Ta nacjonalistyczna liga, znana po raz pierwszy pod nazwą Ligue nationale antisémitique de France (Narodowa Liga Antysemicka Francji) lub Ligue antisémite française (Francuska Liga Antysemicka), była szczególnie aktywna podczas afery Dreyfusa. Oprócz szerzenia antysemickiej propagandy, Liga była również antymasońska i antykomunistyczna. Miał jako generalnych delegatów Jacques’a de Biez. Jules Guérin był jej aktywnym członkiem. Liga mieściła się przy rue Lepic w Paryżu. Jej założenie w 1889 r. zostało zainspirowane sukcesem antysemickiej broszury Drumonta La France juive (1886), a także kryzysem boulangistowskim. Był wspierany przez gazety, takie jak La Libre Parole, Drumonta; Francuski tygodnik Julesa Guérina, L'Antijuif (Paryż, 1896-1902); dziennik La Cocarde (fr) (1888-1907) założony przez Georgesa de Labruyère i redagowany od września 1894 do marca 1895 przez Maurice'a Barrèsa; L'Intransigeant, Henriego Rocheforta; oraz katolicka gazeta La Croix. Oprócz propagandy Liga organizowała także antysemickie demonstracje i prowokowała zamieszki, co później zostało uogólnione przez skrajnie prawicowe ligi we Francji. Potępiła afery panamskie, stanęła po stronie przeciwnej Alfreda Dreyfusa i szerzyła teorie spiskowe dotyczące rzekomej działalności masonerii w III Republice. Po nieporozumieniu między Drumontem i Guérinem w 1899 r. Liga stała się pod kierownictwem Guérina, Wielkim Zachodem Francji, nadal antysemicki, ale jeszcze bardziej antymasoński, a sama nazwa była reakcją na masoński Wielki Wschód Francji. Odtąd był zasadniczo powiązany z gazetą Guérina, L'Antijuif. Liga stopniowo znikała po aferze „Fort Chabrol�� i aresztowaniu Guérina. Po początkowym wzroście podczas afery Dreyfusa, w okresie międzywojennym ponownie pojawiły się skrajnie prawicowe ligi.

0 notes

Photo

EXPOSITION PRINT Vernissage le vendredi 16 septembre à 18h30. J’y participe aussi avec ma série de sérigraphies. PRINT ? Le mot vient du marketing, en opposition au web et à la communication numérique. Là, ce qui nous intéresse c’est non pas l’outil de com, mais le support imprimé, sous quelque forme que ce soit, en temps qu’objet d’art. Là, on parle d’affiches, de livres d’artiste, de fanzines, de gravures, de sérigraphies, de lithographies, de tirages limités sous toutes ses formes et par tous les moyens techniques connus. PRINT ! LE SÉCHOIR se transforme en lieu de tirage et d’impression. A nouveau, il y a du tirage dans l’air au Séchoir. Cela sentira l’encre fraîche. On met à l’honneur tous les médiums de l’imprimé, du livre et des multiples en faisant la part belle à tous les modes d’impression et d’édition. Visite libre tous les week-ends de 14h à 18h. Scolaires et groupes possibles en semaine sur rdv. Artistes présents sur l'exposition : David ALLART / ATELIER DU VESTIAIRE / Hélène BOURDEL Collectif BAN BAN / Alban DREYSSE / Sophie EPTON MOCK Pierre GUERIN / Delphine GUTRON / Jacques HERRMANN / Marie KLINGELHOEFER / Sylvie KROMER / Céline LACHKAR Coralie LHOTE / Eric MEYER / BOUH et SULLY / Sabine MUGNIER / Elsa OHANA / Yolaine SCHMITT / Sandrine STAHL / Antonio TALIS / Henri WALLISER. DES ATELIERS SERONT PROPOSÉS DURANT L'EXPOSITION AVEC LES ARTISTES SUIVANTS : - Pierre Guérin - Collectif Ban Ban - Hélène Bourdel - Eric Meyer - Sylvie Kromer INFOS ICI : https://fb.me/e/2UTrLPK7W DES FORMATIONS AU SÉCHOIR PAR LES ARTISTES RÉSIDENTS ICI : https://www.lesechoir.fr/apprendre (à Le Séchoir Mulhouse) https://www.instagram.com/p/CiZe_nPsjWH/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

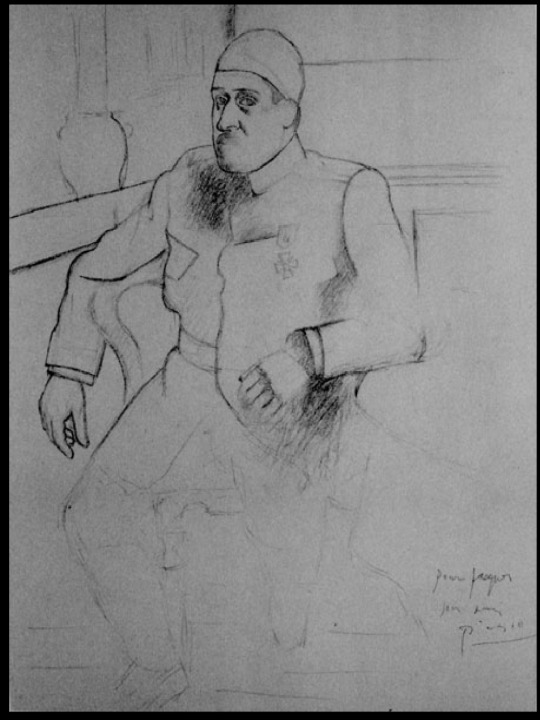

Jacques tenía apenas dieciocho años cuando hizo su primera compra: una rara edición original de L’hérésiarque, de Guillaume Apollinaire. El autor, por entonces, era casi desconocido, y Jacques se llevó ese y otros manuscritos suyos por una bagatela, apenas cien francos de la época. Ya de anciano, recordaría con orgullo ese primer negocio. Subrayaba cómo, años después, se habrían necesitado millones de francos para adjudicarse tal rareza. Para el hijo de un industrial, por qué negarlo, aquel era un placer impagable. Poseía también un peculiarísimo retrato de Apollinaire que Picasso le había hecho en el frente italiano, durante la primera guerra mundial. Jacques conocía bien al pintor; su madre, además de algunos desnudos de Modigliani, tenía una importante colección de cuadros de Picasso. A Guérin el artista español no le gustaba particularmente, pero le reconocía dotes extraordinarias de autopromoción, y lo consideraba un hábil vendedor de sí mismo. Un día fue a verlo a su estudio, donde guardaba precisamente el retrato de Apollinaire. A Guérin la obra no le pareció especialmente bella, y la elogió solo por cortesía. Entonces Picasso la arrancó del álbum y se la dedicó: «Para Jacques».

Ya maduro, se convirtió en un hombre fascinante, refinado y culto, en apariencia arrogante, misógino y autoritario, que gustaba del secreto y amaba las cosas escondidas. Por momentos era mordaz y cáustico, pero con esa sensibilidad y delicadeza que frecuentemente se les atribuye a los homosexuales.

De día, en las largas horas en que tenía que atender los asuntos de la fábrica, llevaba la vida de un industrial, rodeado de químicos que trabajaban como alquimistas de antaño entre miles de pequeñas redomas y viales. Junto a ellos verificaba, comparaba, elegía las esencias, las organizaba en esa «memoria olfativa» de la que estaba particularmente dotado, pero cuando tenía tiempo para sí, prefería orientarse hacia los libros raros y los manuscritos. En esa búsqueda quizá lo motivaba la conciencia de que, como decía Proust, «aquello que nos vuelve traslúcido el cuerpo de los poetas y nos deja ver sus almas no son sus ojos ni los acontecimientos de sus vidas, sino sus libros, donde justamente aquella parte de sus almas que, por un deseo instintivo, quería perpetuarse, se transfirió para sobrevivir a la caducidad».

- El abrigo de Proust, Lorenza Foschini

Traducción del italiano y postfacio a cargo de Hugo Beccacece. Impedimenta,2013

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

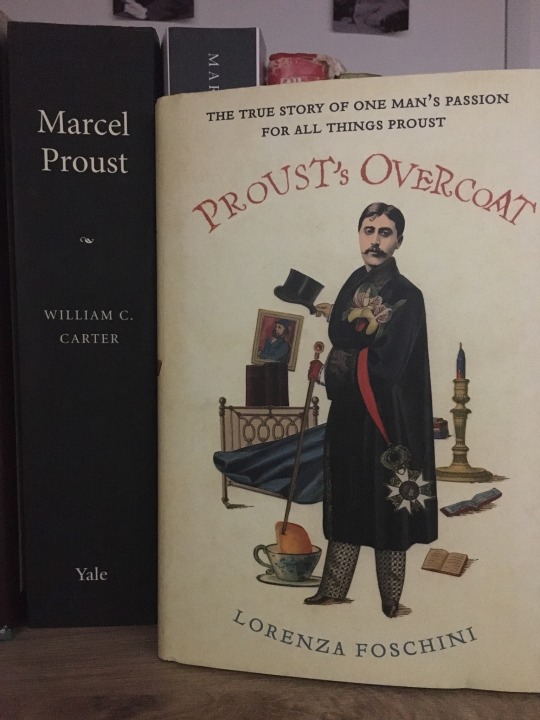

A few days ago I found a book

Which was better than anything I could ever have imagined. Humorous.

And yet utterly tragic all the same. Detailed extensively on what happened to Marcel’s belongings after he died. As a sentimental person, it really pulled on my heart strings when Marcel’s most beloved possessions were just given away to ignorant strangers, destroyed or abandoned to rot in an attic. A lot of the blame can be pointed to Robert Proust’s wife- Marthe. She was understandably, yet cruelly, a cold character. Not to mention that the pair destroyed many of Marcel’s written work due to their shame held over his homosexuality. Marcel’s legendary coat, which he took with him to the bitter end, makes an appearance.

Unfortunately fragile enough to be barred from public display.

Marcel’s smile is everything.

Marcel and his mother are such silly fascinations.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

AU GALA DU LIDO

Par Claude Sarraute

Publié le 20 décembre 1962 à 00h0

Mis à jour le 20 décembre 1962 à 00h00

Les choses, cette année, ont été rondement menées. On nous avait priés d'être exacts : à 21 heures, souper ; à 23 heures, spectacle. Gare aux retardataires. Premier arrivé, en manchettes de dentelles et fort joliment accompagné, Charles Aznavour, bientôt rejoint par Jean Marais. Puis défilèrent, en rang par deux, M. et Mme Vinogradov, M. et Mme Georges Auric, M. et Mme Roger Frey, Robert Hirsch et Jacques Charon les suivaient de près ; sur leurs traces les sœurs Kessler, Catherine Deneuve et son fiancé, Line Renaud et Loulou Gasté. À 22 heures, tout le monde était à table, des tables de dix à quinze couverts que les flashes de l'actualité allaient désigner à l'attention des invités. On prenait le café quand surgirent " last but not least " Cary Grant et Mel-Ferrer. Applaudissements, bousculades, bouchons de Champagne... C'était le final. Le rideau qui tombait sur la salle allait se lever sur la scène.

Suivez-moi, tel est le titre aguichant de cette nouvelle revue destinée à faire des mois durant les coûteuses délices d'une foule cosmopolite où l'étranger à devises côtoie le provincial en goguette, rivalisant l'un et l'autre de la même ardeur à s'initier aux mystères du gay Paree. Ils sortiront de là comblés. La formule reste ce qu'elle était, qui fait alterner les défilés de girls diversement empanachées et les numéros de variétés, encore que l'on ait un peu sacrifié, cette fois, aux seconds les premiers. De cela, personne assurément ne se plaindra. On a souvent applaudi déjà, aux Champs Elysées, ces tableaux de style cow-boy ou persan, ces rythmes de rodéo, ces fantaisies d'Orient, ces fontaines de Trévi, ces fiançailles à Mexico, ces fastes de TRIANON, prétextes à grands déploiements de filles tout en jambes et tout en plumes, tiares, feutres ou turbans.

Mais ce qu'on a rarement vu, par contre, ce sont des attractions de la qualité de celles qu'a retenues Pierre-Louis Guérin. Il en est une, notamment, qui a fait les beaux soirs du Palladium de Londres et qui vaudrait, à elle seule, le déplacement. C'est ce que les Américains appellent un " dog-act ", un numéro avec chien. Ce chien, on le dirait dessiné par James Thurber. Imaginez un épagneul à la patte molle, au regard écœuré, aux longues oreilles découragées, qui opposerait à la bonne volonté épanouie de son maître une nonchalance de vieux blasé, une force d'inertie de disloqué. Résultat d'un intense dressage à rebours, l'effet est prodigieux, dont la drôlerie ne saurait escamoter la difficulté. On devra à Bob Williamset à son chien Louis le meilleur moment d'une soirée qui s'est terminée à l'heure dite, sur une note, grâce à eux, euphorique.

— Claude Sarraute

#lido#charles aznavour#M. et Mme Georges Auric#M. et Mme Vinogradov#jean marais#M. et Mme Roger Frey#robert hirsch#jacques charon#catherine deneuve#Line Renaud#loulou gasté#cary grant#mel-ferrer#paree#champs elysées#Mexico#trianon#Pierre-Louis Guérin#Palladium de Londres#James Thurber#Bob Williamset#le monde#france#en français

0 notes

Text

Jacques Guérin, Jean-Pierre Delauney & Gregg Young - Ferrari 512 BB Compétition-Luigi Chinetti Sr. - 24 Heures du Mans 1978. - source Motor Authorithy.

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Le jour où la France coupa la tête de son roi, elle commit un suicide.

- Ernest Renan (1823-1892)

The painting has served as inspiration for much, from banknotes to a cover of a Coldplay album but is most commonly associated as the definitive painting to depict the storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789 to light the fuse for the start of the French Revolution of 1789. Liberty Leading the People was painted in 1830 by Eugene Delacroix right after the revolutionary effervescence that had swept across Paris that same year.

Characterised by its allegorical and political significance, this large oil on canvas has become a universal symbol of liberty and democracy. Often used in popular culture to symbolise people’s emancipation from oppressive domination, it is one of the most famous paintings in Art History.

However this is wrong.

Liberty Leading the People is a painting usually associated with the July Revolution of 1830 in France. It is a large canvas showing a busty woman in the centre raising a flag and holding a bayonet. She is barefoot, and walks over the bodies of the defeated, guiding a crowd around her.

Eugène Delacroix was a master of colour and it is in Liberty Leading the People that he clearly expressed this. Carefully, Delacroix built a pulsating and dynamic scenario about an extremely current theme in his times. As he participated little in the fighting, he wrote: “If I can not fight for my country, I paint for it.”

The painting is about freedom and revolution. First, because that is exactly what it portrays. In July 1830, France rose up against King Charles X, who was extremely unpopular for, among other things, being very conservative in political terms and trying to restore an old regime that French people no longer wanted. In the artistic sense, the painting also represented a revolution – and more than that: freedom. In the time of Delacroix, painters generally obeyed the rules of the Academy of Fine Arts which stressed the mastery of drawing, disegno. Delacroix, however, put more emphasis on the use of colour in an unobstructed way.

A year after its production, the painting was bought by the French Government and but was not on display for a long time. Currently, the artwork is part of the Louvre collection.

If Jacques-Louis David is the most perfect example of French Neoclassicism, and his most accomplished pupil Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, represents a transitional figure between Neoclassicism and Romanticism, then Eugène Delacroix stands (with, perhaps, Theodore Gericault) as the most representative painter of French romanticism.

French artists in early nineteenth century could be broadly placed into one of two different camps. The Neoclassically trained Ingres led the first group, a collection of artists called the Poussinists (named after the French baroque painter Nicolas Poussin). These artists relied on drawing and line for their compositions. The second group, the Rubenists (named in honour of the Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens), instead elevated color over line. By the time Delacroix was in his mid-20s - that is, by 1823 - he was one of the leaders of the ascending French romantic movement.

From an early age, Delacroix had received an exceptional education. He attended the Lycée Imperial in Paris, an institution noted for instruction in the Classics. While a student there, Delacroix was recognised for excellence in both drawing and Classics. In 1815 - at the age of only 17 - he began his formal art education in the studio of Pierre Guérin, a former winner of the prestigious Prix de Rome (Rome Prize) whose Parisian studio was considered a particular hotbed for romantic aesthetics. In fact, Theodore Gericault, who would soon become a romantic superstar with his Raft of the Medusa (1818-19), was still in Guérin’s studio when Delacroix arrived in 1815. The young artist’s innate skill and his teacher’s able instruction were an excellent match and prepared Delacroix for his formal admission to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts (the School of Fine Arts) in 1816.

To become leading figure of the French romantic school, Delacroix wished to emancipate himself from academic art’s classical ideal and canons. The subject of the painting was a contemporary one, whereas canvases of this size were generally reserved for historical paintings, at least according to the rules of the hierarchy of genres of the Academy. Delacroix stated that he has “undertaken a modern subject, a barricade, and although I may not have fought for my country, at least I shall have painted for her. It has restored my good spirits.” The painter also uses reds and blues, which result in stark contrasts, instead of the more muted colours that were used at that time.

Delacroix wasn’t much of a revolutionary himself and did not take part in the Paris fighting, but rather defined himself as a “simple stroller.” As he wrote in a letter to his brother; “A simple stroller like myself ran the same risk of stopping a bullet as the impromptu heroes who advanced on the enemy with pieces of iron fixed to broom handles.” However, he advocated for liberalism and was struck by a feeling of patriotism and pride as he observed his fellow citizens fighting.

The revolution depicted in this painting is not to be confused with the 1789 French Revolution. Delacroix was inspired by the events of the July Revolution (known as Les Trois Glorieuses” (Three Glorious Days), a political upheaval that took place between 27th and 29th July 1830. These violent demonstrations took place as the ruling French King Charles X tried to restrain the freedom of the people by executing a constitutional takeover. Parisians violently protested against the abuses of their individual rights. Rioters took hold of the city and violent fighting ensued, resulting in a high death toll. Charles X eventually abdicated and a constitutional monarchy, the July Monarchy, was established with Louis-Philippe I being made King of the French.

This uprising of 1830 was the historical prelude to the June Rebellion of 1832, an event featured in Victor Hugo’s famous novel, Les Misérables (1862), and the musical (1980) and films that followed. Anyone familiar with Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil’s musical can look at Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People and hear the lyrics of the song that serves as a call to revolution:

Do you hear the people sing? Singing a song of angry men? It is the music of a people. Who will not be slaves again.

Marianne, the Allegorical Muse

At the centre of the painting, the allegorical depiction of Liberty draws the eye immediately. Represented as Marianne, a symbol of the Republic, the woman coiffed with a Phrygian cap (a nod to the sans-culottes of the French revolution) is leading a group of revolutionaries. Her draped yellow dress reveals her breast and recalls the Greek goddesses of Antiquity. Her profile, a straight nose, plump lips, and a delicate chin are reminiscent of Antique Greek and Roman statues. She is a tribute to Ancient Greece, the cradle of democracy, as well as to the Roman republican tradition. However, Delacroix mixes in modern symbols as she holds the tricolour flag in one hand, and a bayonet in the other. This way, Liberty embodies both the modern struggle and Antiquity’s ideology of freedom.

The painting’s pyramidal structure heightens the fighting’s momentum. The ground is strewn with bodies and, out of the misery and pain, Liberty stands tall on the remains of a barricade, emerging strong and victorious. This rigorous composition contains and balances the painter’s impetuous brushstrokes and creates a striking lighting effect. It is a scene of chaos and energy, filled with smoke and movement, and yet Delacroix’s pyramid successfully creates a sense of order. The painting recalls Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa, that represents violence without idealising it.

The title makes it obvious, the woman represented here is the ideal of freedom. But even as an allegorical figure, the woman is more than that: her name is Marianne, which is probably the result of joining together two very common names in France at the time, Marie and Anne.

Curiously, 18 years after the July Revolution, Marie Anne Hubertine, a French activist who fought for the insertion of women in politics, was born. This is because, although the representation of freedom was feminine, women still couldn’t vote or stand for public office - although the female figure was always chosen to represent most of the allegories.

Liberty protagonists in the painting

But if the female figure represents an allegory, those who surround her represent different types of people. The man on the far left holds a briquet (an infantry saber commonly used during the Napoleonic Wars). His clothing - apron, working shirt, and sailor’s trousers - identify him as a factory worker, a person in the lower end of the economic ladder. His other attire identifies his revolutionary leanings. The handkerchief around his waist, that secures a pistol, has a pattern similar to that of the Cholet handkerchief, a symbol used by François Athannase de Charette de la Contrie, a Royalist solider who led an ill-fated uprising against the First Republic, the government established as a result of the French Revolution. The white cockade and red ribbon secured to his beret also identify his revolutionary sensibilities.

This factory worker provides a counterpoint to the younger man beside him who is clearly of a different economic status. He wears a black top hat, an open-collared white shirt and cravat, and an elegantly tailored black coat. Rather than hold a military weapon like his older brother-in-arms, he instead grasps a hunting shotgun. These two figures make clear that this revolution is not just for the economically downtrodden, but for those of affluence, too.

Delacroix clearly suggests that people of all classes came together to fight for a better society. The revolution was not about one class fighting another, but it was about the people rallying against royalist oppression.

This revolution is not only for the adults - two young boys can be identified among the insurgents. On the left, a fallen adolescent who wears a light infantry bicorne and holds a short sabre, struggles to regain his footing amongst the piled cobblestones that make up a barricade. The more famous of the pair, however, is on the right side of the painting (image, right). Often thought to be the visual inspiration for Hugo’s character of Gavroche in Les Misérables, this boy wildly wields two pistols. He wears a faluche - a black velvet beret common to students - and carries what appears to be a school or cartridge satchel (with a crest that may be embroidered) across his body.

The dead bodies of soldiers and citizens on the ground represent the terrible costs of the revolution.These are best summed up by the figure on the left corner, who is nude from the waist down and wears only a nightshirt, implying perhaps that royalists had dragged him from his bed to impart on him a terrible fate. The body is the very close to the viewer, invading our immediate vision.

A modern urban painting

With no less than five guns and three blades among these six primary figures, it is not surprising that the ground is littered with the dead. Some are members of the military, note the uniform decorated with shoulder epaulettes on the figure in the lower right, while others are likely revolutionaries. In total, the painting accurately renders the fervour and chaos of urban conflict. And it is, of course, an urban conflict. Notre Dame, perhaps the defining architectural monument of Paris (at least until the Eiffel Tower arrived at the end of the nineteenth century) can be clearly seen on the right side of the painting. Importantly, Delacroix signed and dated his painting immediately underneath this monument.

Although not everyone can pick up a weapon and stand a post in a war, Delacroix would have us believe that everyone can be a revolutionary. When corresponding with his brother on 28 October 1830 - less than three months after the July Revolution, Delacroix wrote, “I have undertaken a modern subject, a barricade, and although I may not have fought for my country, at least I shall have painted for her. It has restored my good spirits.” In doing so, Delacroix completed what has become both a defining image of French romanticism and one of the most enduring modern images of revolution.

Post-life of the painting

On instructions from Louis-Philippe, Liberty Leading the People was bought by the French Ministry of the Interior (for 3,000 francs). The painting was purchased by King Louis-Philippe to demonstrate his support of Republican values and to mark his accession. In other words as a sop to the liberal left. The original idea was to display it in the throne room of the Palais du Luxembourg, but instead it was kept in the palace's museum gallery. The painting caused a commotion at the Salon, and it was kept hidden from the public owing to its inflammatory and seditious nature.

The reaction of the general public to the Liberty at the Salon of 1831 is not well documented. Heinrich Heine records that he always saw a throng of visitors in front of it and therefore concluded that it was one of the paintings which attracted the most attention. Gustave] Planche on the other hand, got the impression it was not enjoying the public success he thought it deserved. The picture was received with mixed feelings by the professional critics, who divided roughly into those who judged the realism ignoble, the colouring drab or distastefully livid and the allegorical Liberty a contradiction within itself or within the context of the whole (e.g. Auguste Jal, Louis Peisse, Ambroise Tardieu); and those who by contrast admired the combination of truth to nature and artistic licence, and recognised that the subject demanded a wide use of earthy colours (Planche, Victor Schoelcher, Charles Lernormant).

Théophile Thoré, a few years after the Salon, resolves most concisely the argument about anomalies in the central figures when he wrote, ‘Is it a young woman of the people? Is it the genius of liberty? It’s both; it is, if you’d like, liberty incarnated in a young woman. True allegory should have a character that is simultaneously alive and symbolic…Here again, M. Delacroix is the first to have utilised a new allegorical language.’

Following the June Rebellion of 1832, it was returned to the artist. because the revolutionary ideologies behind the painting became perceived as dangerous and potentially inflammatory. A good reminder of how politicised art was in nineteenth century France. On his death in 1863 it was reacquired by the Musee du Luxembourg who in 1874 passed it to the Louvre.

The picture is believed to have inspired Bartholdi's Statue of Liberty (1870-86) - a depiction of Libertas, the Roman goddess of freedom - which was given to the United States as a gift from the French people. Today it is considered to be a universal work symbolising the triumph of the 'popular will', and an important forerunner of 20th century works like Picasso's Guernica (1937, Reina Sofia Art Museum, Madrid).

But it’s more than just a ‘political’ painting. The emotional rhythm of Delacroix's brushstroke seemed to be central in his originality. In its diversity one can see long and large, continuous strokes as well as small, divided, independent ones. Such techniques had a great influence on the Impressionist and Post-Impressionists, particularly van Gogh and Cezanne.

In sum then, Delacroix’s apotheosis of the Revolution of 1830 was, in a way, the apotheosis of his generation. That is the way it is seen by art critic René Huyghe: “From time to time a work of art contrives to bring together and express all the ideas that mean most to the spirit of a particular time and give it its meaning. This is certainly the case with Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People, in which the clamour of a generation on the march becomes a joyous and unanimous hymn.”

When, however the search for unanimity is focused on the lists of killed and wounded on the revolutionary side of the barricade, it does not reveal an ‘entire people,’ but the worker-artisans who comprised, mutatis mutandis, the Paris insurrectionary crowds from 1789 to 1871. It is difficult to find that figure in the top hat, or the student from the Ecole polytechnique, or even the pistol-packing gamin, forerunner of [Victor] Hugo’s Gavroche, on the lists of those who actually did the fighting. Even so, the painting was soon perceived as a disproportionate celebration of the unwashed masses by those who would reap the political fruits of the ‘three glorious days’ of July.

The ambiguity of Liberty Leading the People, dated 28 July when the issue of the battle was still in doubt, might also be read as representing the political indeterminacy of the event. Delacroix portrays the last moment before the solidarity of his generation fractured along political lines. Those who contrived the invention of King Louis-Philippe would find the fulfilment of their ambitions and their spiritual home in the July Monarchy. For this reason I have always found this painting intriguing because of its ambiguity of meaning behind the appropriation of symbolism.

** La Liberté guidant le peuple (1830) by Eugène Delacroix

#renan#ernest renan#quote#fete nationale#14 july#bastille day#french#france#history#french revolution#art#delacroix#painting

123 notes

·

View notes

Photo

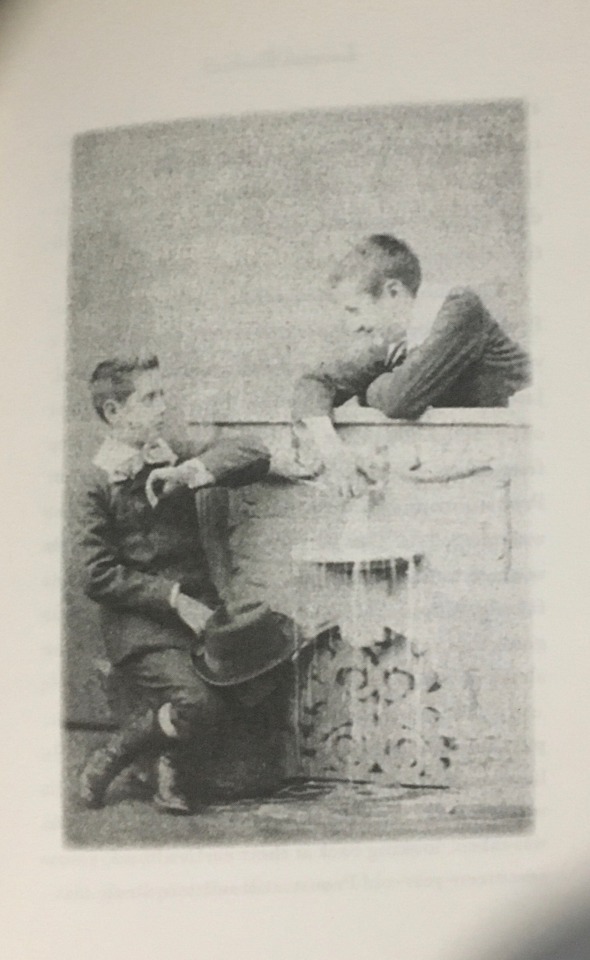

Guerrero desnudo con lanza, c. 1816

Artistas / Creadores: Théodore Gericault (artista). Francés, 1791-1824

Medio: óleo sobre lienzo

Dimensiones: total: 93,6 x 75,5 cm, enmarcado: 118,4 x 101,6 cm

Línea De Crédito: Colección Chester Dale

Número De Acceso: 1963.10.29

VISIÓN GENERAL

A los diecinueve años, Théodore Gericault entró en el estudio parisino de Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, un exitoso seguidor de Jacques-Louis David. En el estudio de Guérin, el joven Gericault habría perfeccionado sus habilidades dibujando a partir de estatuas y moldes antiguos en el Louvre y luego después del modelo en vivo como preliminar a las obras a gran escala.

The Nude Warrior with a Spear es una atrevida presentación del desnudo masculino que para los contemporáneos de Gericault habría recordado una "académie", o boceto que fue ejecutado como ejercicio y destinado a servir de inspiración para composiciones posteriores, más terminadas. Sin embargo, en este trabajo, Gericault ha transformado su ejercicio en una pintura de caballete terminada. La pierna derecha, la lanza y el brazo izquierdo del modelo constituyen tres diagonales paralelas, y el cuerpo en sí está dividido en una serie de triángulos entrelazados, como puede verse en el brazo derecho y el muslo izquierdo doblados. El poder de la figura, sin embargo, se comunica a través de la cabeza, apartada del espectador y mirando hacia un paisaje árido.

Información de la National Gallery of Art.

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

POST-SCRIPTUM 773

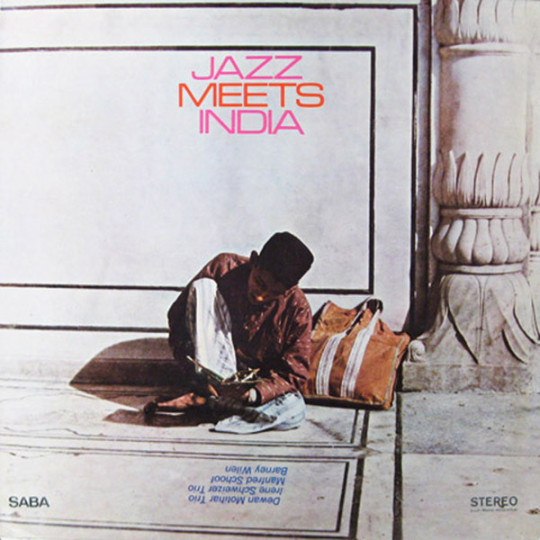

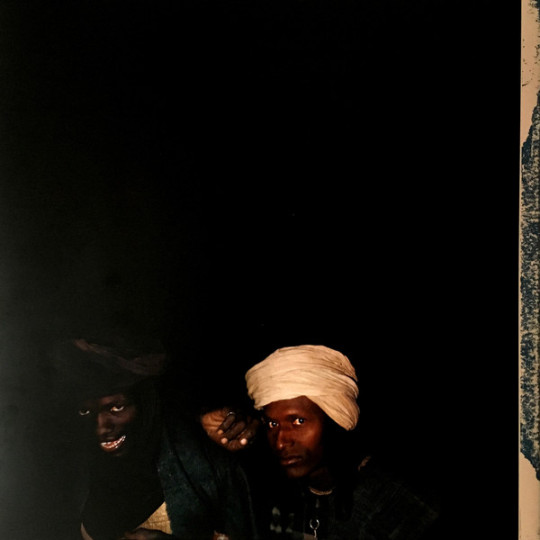

BARNEY WILEN, Moshi (1972)

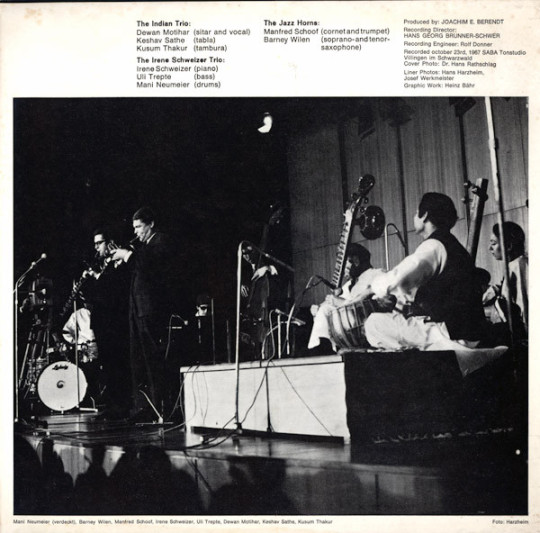

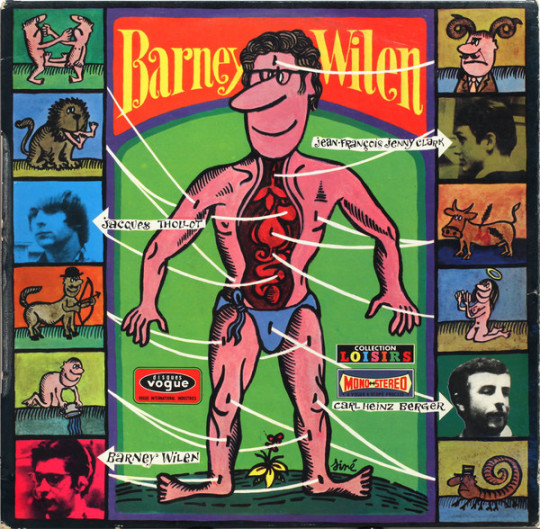

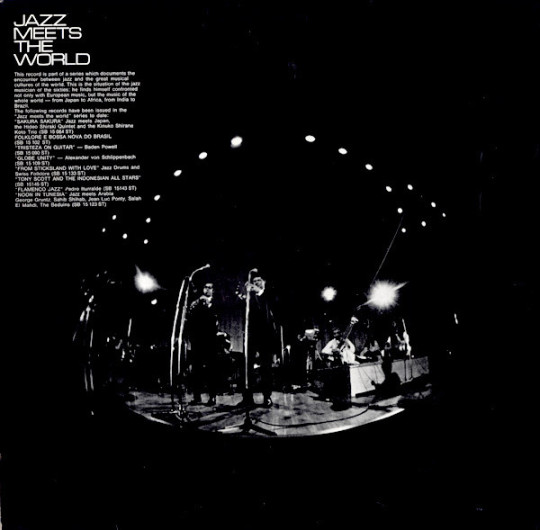

Dès 1967, en compagnie de la pianiste Irène Schweizer, du trompettiste Manfred Schoof et de la section rythmique du groupe allemand Guru Guru, Barney Wilen tisse déjà des liens entre jazz et musiques du monde sur l’album Jazz Meets India produit par Joachim-Ernst Berendt, critique de jazz pionnier en la matière.

De même, Barney Wilen se montre sensible au free jazz américain qu’il honore alors à Paris, au Requin Chagrin, en compagnie du vibraphoniste Karl Berger, des bassistes Jean-François Jenny-Clark, Beb Guérin et du batteur Jacques Thollot, alors qu’à quelques encablures, dans une même veine, le pianiste François Tusques sévit à La Vieille Grille. C’est l’époque où François Jeanneau, Michel Portal, Bernard Vitet et quelques autres animent des nuits d’effervescence particulières, ce dont témoignent l’album Le Nouveau jazz de François Tusques (en 1967 toujours), et Zodiac (un an auparavant), signé par Barney Wilen celui-là. Ces deux disques ont tout du bras d’honneur au conformisme ambiant, que d’ailleurs Barney Wilen réitère sur Dear Prof. Leary, en référence au grand manitou du LSD et afin de rendre notamment hommage à Bobby Gentry, Otis Redding et aux Beatles, ce qu’il fait en compagnie du guitariste Mimi Lorenzini, transfuge encore adolescent (et allumé) du groupe du chanteur de variétés Claude François !

1968 : la séquence free se poursuit dans un hommage au pilote de l’écurie Ferrari Lorenzo Bandini, mort en course lors du Grand Prix de Monaco l’année précédente. Bareny Wilen : « Quand je souffle, je ferme les yeux et je vois des images. Ces images correspondent à des états vagues plus ou moins précis qui renvoient à ce que j’ai vu, entendu ou lu. » C’est aussi l’époque où le saxophoniste part en Afrique vérifier sur le terrain ce qu’il sait de la musique pygmée et de l’afrobeat. Avec sa compagne Caroline de Bendern, égérie de Mai 68 célébrée par une photo des événements où elle apparait juchée sur les épaules du plasticien Jean-Jacques Lebel, Barney Wilen fait sienne – en le rejoignant – l’innocence sauvage du collectif Zanzibar (Philippe Garrel, Serge Bard, Daniel Pommereulle, Patrick Deval) dont les expériences comptent parmi les plus fascinantes du cinéma français.

Sahara, Mali, Niger : Barney Wilen et Caroline de Bendern prennent la route, et de Tanger à Zanzibar la vie s’écoule. Caroline de Bendern : « Trois Land Rover peints en jaune, orange et rouge brillant, une caméra 35 mm et tous ses accessoires, beaucoup d’instruments de musique, amplis et magnétophones… Je crois que vous avez compris… On n’est jamais arrivé à Zanzibar ! » Heureusement, au fil des rencontres, les bandes s’accumulent par dizaines. Initiatique, ce voyage est suivi d’un second, plus bref mais pas moins nécessaire à la réalisation d’un disque (le fameux Moshi) pour Saravah, le label de Pierre Barouh. Face au matériel sonore ramené, Barney Wilen et son groupe célèbrent donc le « moshi » sous la forme d’une transe faisant la part belle aux rituels traditionnels et parcourue d’une spiritualité joyeuse dialoguée en re-recording, avec un gros clin d’œil au Karma de Pharoah Sanders. Barney Wilen : « Le swing participe de la magie. C’est une manière de faire ou de dire des choses, telle qu’on est toujours dépassé par ce qu’on fait. »

( Beb Guérin, par là )

#barney wilen#françois tusques#bebe guérin#jean-françois jenny-clark#pharoah sanders#pierre barouh#philippe robert#agitation frite 2#guru guru#mani neumaier#uli trepte#irène schwiezer#manfred schoof#caroline de bendern#lenka lente#philippe garrel#jean-jacques lebel#serge bard#daniel pommereulle#patrick deval#françois jeanneau#michel portal#bernard vitet#timothy leary#joachim-ernst berendt#otis redding#bobby gentry#the beatles#post-scriptum#merzbo-derek

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yves GUILLOUAlias GUERIN-SERAC

Yves Guillou est le prototype de l’officier perdu.Des froides montagnes de Corée en passant par les rizières d’Indochine jusqu’aux djebels d’Algérie, Yves Guillou s’est aguerri à plusieurs sortes de combats avant de lancer sa croisade contre le communisme et le marxisme culturel.

Il entre dans l’armée en 1947 et part pour la Corée en 1950, où il gagne la bronze star américaine et la médaille des nations unies après s’être particulièrement fait remarqué pour sa bravoure lors de la bataille d’Arrow Head Hill. Il est ensuite breveté parachutiste et part pour l’Indochine au sein du 1er BPC où il gagne deux blessures, la légion d’honneur et la croix de guerre avec citation. Puis c’est l’Algérie, il est affecté au 11ème Choc comme capitaine. Ils sont le service « action » du SDECE (le renseignement de l’époque), et infligeront de sévères pertes au FLN. En 1962 il déserte et rejoint l’OAS .

Son rôle dans l’oas est peu connu, il aurait commandé un maquis prés d’Oran. A l’indépendance algérienne, il se réfugie en Espagne, à Saint Sébastien avec le colonel Château Jobert et participe à la création du mouvement de combat contre révolutionnaire et du CNR avec Georges Bidault.

Il part ensuite vivre au Portugal.« Après l’OAS, je me suis réfugié au Portugal pour continuer le combat et pour l’élargir à sa vraie dimension, qui est celle de la planète » déclarera t’il au journal Paris Match en 1974

. Dans la tête du Capitaine Guillou germe déjà l’idée d’une organisation internationale anticommuniste formée de spécialistes de la guerre révolutionnaire et de la contre subversion.

A Lisbonne, c’est par l’intermédiaire du théoricien nationaliste Jacques Ploncard d’Assac, qui gravite dans l’entourage direct du dirigeant portugais Salazar, qu’Yves Guillou prend contact avec les autorités de ce pays.

Le Capitaine Guillou, qui s’appelle désormais Ralf Guérin Sérac, sera d’abord engagé comme instructeur des unités anti-guérillas de l’armée.

Entre-temps, un groupe de fidèles, des anciens de l’OAS, l’ont rejoint à Lisbonne.

Chez tous ces anciens de l’OAS a muri l’idée de créer une organisation anticommuniste internationale.

Les autorités portugaises chargent Guérin Sérac et ses amis, engagés par la PIDE (les services secrets portugais), de la constitution de ce réseau.

Guérin Sérac devait organiser une agence de presse qui serve de couverture à une organisation chargée de s’infiltrer dans les pays africains.

En effet, la PIDE avait besoin à l’époque d’un réseau de renseignement pouvant fonctionner dans les pays africains qui abritaient les mouvements de libération des colonies portugaises.

Ce sera la création de l’Agence Internationale de presse, Aginter Press.

Parallèlement, Guérin Sérac met sur pied une organisation clandestine « Ordre et Tradition » qui réunit deux types d’hommes :

-des officiers venus à lui après les combats d’Indochine et d’Algérie, certains même de Corée.

-des intellectuels, qui pendant les mêmes périodes, s’étaient attachés à l’étude des techniques de subversion marxiste.

Les uns et les autres, mêlés de très près aux combats des dernières années, ont accepté, par des chemins différents, de disparaître dans la clandestinité où la plupart d’entre eux ont passé au moins cinq ou six années.

Constitués alors en groupes d’études, ils ont mis leur expérience en commun pour essayer de démonter les techniques marxistes de subversion et de tenter de jeter les bases d’une parade.

Pendant cette période, ils ont noué des contacts avec des groupes similaires nés en Italie, en Belgique, en Allemagne, en Espagne ou au Portugal, pour fonder le noyau d’une véritable ligue occidentale de lutte contre le marxisme.

A cette ligue occidentale de lutte contre le marxisme, Guérin Sérac donne le nom OACI :

Organisation d’action contre le communisme international, son rôle, être prête en toute occasion à intervenir dans n’importe quelle partie du globe pour affronter les plus graves menaces communistes.

Afin de ne pas dépendre complètement des Portugais, Guérin Sérac et son équipe ont pris contact avec les gouvernements sud africain, brésilien, rhodésien, sud vietnamien et de la Chine nationaliste.

En France, l’équipe d’Aginter a gardé de bons rapports avec les milieux d’anciens OAS et après 1966, avec le mouvement Occident et le Mouvement Jeune Révolution.

Sur la base de tous ces contacts, Guérin Sérac et son équipe avaient mis en place un réseau d’informateurs et de correspondants dans toute l’Europe.

Au départ, ils effectuaient un travail banal de correspondant de presse, correspondant spécialisé puisqu’il s’agissait essentiellement des informations sur les activités des communistes et des gauchistes, sur leur pénétration dans l’armée, leur financement, les organisations qu’ils contrôlaient, etc… Enfin, certains correspondants effectuaient aussi des stages à Lisbonne où, dans le cadre de l’OACI, ils recevaient une formation spéciale.

Aginter avait installé dans la capitale portugaise une véritable école des techniques de subversion.

Les recrues étaient entrainées pour des actions de sabotage dans des camps, notamment, au sud du Portugal dans l’Algarve, et le plus important était à Windhoek dans le sud ouest africain.

Cette formation spéciale se déroulait sur une période de trois semaines :

5 jours par semaine avec des cours théoriques le matin et des travaux pratiques l’après midi.

Cet enseignement était divisé en quatre matières :

action, propagande, renseignement et sécurité, et mettait spécialement l’accent sur l’action psychologique et les techniques de terrorisme et de sabotage, ainsi que l’utilisation des explosifs et l’emploi des armes.

Les élèves étaient ainsi préparés à des missions spéciales du style de celles qu’effectuent les services « action » des services spéciaux officiels : action commando, espionnage, mission d’intoxication, attentat, assassinat, etc.

L’un de ces cours théoriques était ainsi rédigé :

"La subversion agit avec les moyens appropriés sur les esprits et sur les volontés pour conduire à agir en dehors de toute logique contre toutes règles, contre toutes lois, elle conditionne ainsi les individus et permet d’en disposé à son gré.

"

L’Afrique est le premier champ d’opération de Guérin Sérac et de ses hommes.

L’Agence envoyait ses officiers d’opération dans les pays limitrophes de l’Afrique portugaises.

Yves Guillou participera aussi à l’élaboration d’un commando anti ETA au pays basque avec, entre autre, l’aide d’anciens commandos delta de l’OAS.

A la chute de Salazar, Yves Guillou quitte le Portugal pour l Espagne, nous ne savons pas ce qu’il est devenu et s’il est encore vivant...

9 notes

·

View notes