#its one of my favourite possible ways of looking at the canon because it's hysterical

Text

controversial post but i think i'm just too much of an actual adult to be into hlvrai shipping. none of them are kissing on the mouth. none of em.

especially not gordon and benrey. they are however the world's worst roommate. worsties, if you will. gordon gets a notification every time he looks at that uncanny shitass gamer and it says "newsflash: the worst person you know is hysterically funny sometimes" and the funny aspect is just endearing enough that it prevents him from going entirely looney tunes insane

likewise benrey looks at him through the lens of like "man my new friend I found at the end of the world alien event is fucking mean to me sometimes for no reason. this surely has nothing to do with me, benrey, because I am normal and excellent at making friends on PSN." but also he mutually just finds him fun enough that he's genuinely distraught when it turns out gordon actually fucking hates him and isn't picking up on any of his (incomprehensible) bullshit about not wanting to be an antagonist

literally tldr: why would you ever want to make their relationship into anything else when the "wow everyone else here is so strange (mildly lovingly and also with a fair amount of dread and frustration). glad I'm the only normal person here" dynamic is there and 10x funnier than any possible outcome in which neurotic gordon freeman makes out with low res security guard

and also there are literally 3 other deranged individuals ripe for you people's enjoyment. go get them.

#listen i do genuinely like the idea that benrey is nowhere near as antagonistic in his own mind as he comes across#its one of my favourite possible ways of looking at the canon because it's hysterical#i also have a chronic case of “need this to be deeper than it is” disease#i too am guilty of looking at a comedy series and trying to pull Lore and Development out of it in swathes#but goddamn. if we're gonna make a compelling narrative out of half life funny can we explore other options#im not going to like hit you with a sledgehammer for objectively harmless fandom content but i want to see other shit#hlvrai#benrey#tagging him too the bitch is relevant to this#gordon hlvrai

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

thea gushes over kate's "alex vs the school for good" fanfic

i've reread this fanfic twice before it was finished but now it's finished, therefore i will read this beautiful work of art a third time and i have no regrets because this is the best fanfic in the entire fandom and i love kate so let's go (u never asked for it but here it is @pumpkinpaperweight)

i love how alex's close relationship with her parents, especially tedros, is already established within the first scene

alex is so witty and her mind is so sharp i've missed her so much :')

alex ribbin on tedros and agatha laughin as a sign of encouragement is my favorite thing

chapter 3: hooray for teenage angst

I STILL CAN'T GET OVER THE FACT THAT TEDROS NAMED HIS DOG CHICKEN THAT IS SUCH A TEDROS THING TO DO

will there be a one shot on the multiple ooty ambassor incidents????? i am Excited

"...and the author of this tale had lost their copy of The School for Good and Evil, and therefore could not remember exactly what the School for Good was meant to look like. They were running entirely off memory, and not doing a bad job, all things considered." KATE AKSKSJDKLFJ

get this: what if the camelot years were just a fever dream and alex vs is canon. what if.

chapter 10: these dogs are still alive for plot devices and comic relief don't @ me

marcy girl chill out

omg dean cromwell vs alex wearing the boys' uniform scene - iconic and sora-approved

oh my god i actually thought sophie stopping thorne was a scene in the actual books instead of in alex vs skdjkdfs

i love kate's adult! sophie - very realistic and in character

chapter 13: HA! GAY!

talib and sora my babies my precious my lovelies

"talib grinned, looking back in the direction of the classroom - sora kept looking at him and missed a step on the stairs" gay

chapter 15: my gran could do better, and she killed a warlock with a cheesecake - I LOVE THE CHAPTER TITLES SO MUCH

alex is so precious why are people being so mean to her :'( sora and i will happily burn them alive

"chaddick and lancelot always smacked her with the butt of the sword to signify a hit, but tedros had tended to sort of half-heartedly shove her off of the mat, unwilling to hurt her" tedros being a good and caring soft dad :')

"alex, what does your dad have?" "low self-esteem?" JESUS ALEX SKDFJLSDJFLJFSLDJ

"alex's temper was utterly uncontrollable, and hort didn't know how he'd forgotten- now it was all rushing back to him in one big, rather traumatic, wave" I'M LAUGHING

omg four year old alex defending her father i'm heart eyes

#i don't like this cromwell bat bring dovey back

"sora's brain was still trying to work out which panic he should prioritise more -the super deadly predators trotting at his feet, or the fact that talib was holding his hand?" Gay

seeing alex cry is like seeing a friend crying - it makes you sad and murderous

"we have been in so many fights.” said alex tiredly. “i wish our author would think of something else. but she won’t, it’s the Trial by Tale next, and that’s all fighting” KATE

chapter 21: EMMA, THEY'RE HOMOSEXUALS

"sora had snatched nadiya’s handkerchief and thrown it to talib like a maid watching her favourite knight" [crying] i would kill a small child for them

sora and alex trying to hide behind each other at the same time is makin me burst into hysterics

oooo sora bout to murder a bitch

sophie acting like an actual dean :')

nadiya's such a queen we stan

june being friends with talib and fondly calling him an idiot is my new religion

alex saying she's the "loser daughter" and me knowing that tedros and agatha are watching her right now hurts. thanks a lot kate

june and thorne???? ship????

omg sora laying it on thick and pretending to be unconscious so talib could carry him sldjsdlkfjdslf

SORA COMPLIMENTING TALIB ON HOW BEAUTIFUL HE LOOKS IN FRONT OF THEIR CLASSMATES

"my darling angel prince" that's Gay "sora fiddled with talib's collar" GAYYYYY

"gentle marital dispute" i adore kate's humor

TALIB PUNCHING THORNE TO PROTECT SORA

"wow,” said sora dreamily.

“he just punched someone in the face, sora,” sighed marcy.

“i’m dying, not blind. that was hot--”

im going to have a heart attack

sora dragging tedros is my new favorite thing

"sora smiled in a very self-satisfied sort of way, almost as if he knew the annoyance he’d caused several hundred miles away" this is sora's true talent

i love how alex breaks the 4th wall

sora: i don't know whether you've noticed, alex, but i can be really rude?

alex: ur not that rude to me

sora: because i thought it might make u cry

:') i love their friendship so much

yes alex! call him out! sora IS emotionally constipated!

omg im curious as to what color alex's fingerglow is

OMG ALEX'S TALENT IS RELATED TO AGATHA'S I LOVE IT

newsflash cromwell! we don't care about ur reputation OR you

alex clutching onto her aunt's arm :'(

awwwwhhh alex w curly hair!! <3

talib is the sweetest boy ever oh my goodness

OH MY GOD HE'S A PISCES OF COURSE KSJFSDJF SOFT BOY

sora is an aquarius HAHA suits him

alex's dramatic entrances are clearly from sophie's influence :')

talib gifting sora roses that's Gay

sora foreshadowing how ros and raiden will get along >:)

sora is a grumpy old man in a 16 year old body but WILL eat his friend's questionably edible birthday cake made for him don’t test him

TALIB AND SORA KISSING QUEEN KATE REALLY DELIVERS

SORA MAKING THE FIRST MOVE I AM SCREECHING I AM GOING TO BITE MY ARM OFF

oh my go d talib don't go ohmygod kate why

OMG ROSALINE POV I'M EXCITED

agatha planning a wrestling match with her and tedros vs cromwell and agatha confirming that the coven have spilled blood over june and will not hesitate to do it again is my favorite thing

if u look closely or if u look at all, ros is clearly a never

tedros: i don't have favorites

agatha: i do. you're my least favorite

tedros: i'm ur husband

agatha: so?

omg alex is tedros' favorite and marcus is agatha's favorite so does that mean ros is sophie's favorite

and now we're in marcus' POV? kate just keeps delivering

omg the famous camelot family scene i've been waiting for is finally coming to fruition

it's official: we stan emi

whenever i hear somebody call agatha the queen of camelot, i get this tight ache of pride in my chest

i love how marcus just looks at his father and tedros knows exactly what he's asking :')

raiden and the twins, marcus and ros? my Body is Ready for ros vs

WHAT IS IT WITH PEOPLE SLAMMING THE DOOR OPEN IN THIS FANFIC KSHFDJFSLJLJ

anemone campaigning for a ranking board that says who has the hots for who is something i can get behind

"there was a brief scuffle whilst both tedros and agatha fought to hug alex at the same time, which she didn't look in the least bothered about" ALEX FAMILY TIME YAY <3

alex introducing agatha, her famous mother, to her roommates is one of my favorite things

"alex stuck her tongue out at her and went back to rifling in her mother's cloak pockets for food" if this isn’t me -

alex being a wingwoman to make her mom sign marcy's copy of the tale of sophie and agatha is my favorite thing #1972934794

talib not recoginizing tedros as the king of camelot but as alex's dad :')

THE COLD SHOULDER SMOULDER

i love how ros could tell how much a fashion piece costs and what material it is just by looking at it

"there was a resounding crash, and another blade caught his, halfway" i love how tedros entered into this chapter kate is such a good writer

im lovin these marcus and ros descriptions

"rosalind and marcus looked at each other, then, slowly, back at jimmy. both of them suddenly looked a lot older than they were. raiden wondered how much damage they could do as a team. probably quite a lot" "raiden resisted the urge to squish marcus's cheeks" ROS VS HERE I COME

sophie rushing bc she senses drama is a big mood

omg i love these camelot year references

"...whilst tedros tried to pretend he hadn't just tried to shove agatha behind him, and awkwardly returned Excalibur to its sheath" his instincts :')

people mentioning that alex is a big sister makes me feel warm inside

the image of tedros braiding rosalind's hair gives me heart eyes

OMG GIN MILLS AND THE GOODS REFERENCE HAHA I SEE WHAT YOU DID THERE KATE

im glad they're talking about alex and the reverse mogrification incident! i am also Intrigued

wait i thought ros and marcus were 10 years old? but agatha mentions how ros is 13? did i miss something

alex and hester aunt and niece relationship :')

this unspoken understanding between the pendragons is everything bless u kate

"i love it when Evers act like Nevers," emi told her grandsons from under her tree. “it’s good for the liver.”

EMI KNOWS ROS IS A NEVER SHE CALLED IT

oh alex u sweet darling child of course sora and talib are boyfriends even thorne could see it

this alex and thorne thing? gotta say,,,,,, i see the ship possibilities

SORA YOU EMOTIONALLY CONSTIPATED BUFFOON JUST TALK TO YOUR BOYFRIEND TALIB OH MY GOD

omg the everboys sitting in the beautification lesson im excited

emma,,,,... darling,,,,.........,,, they're Gay

i support alex's plan to look hot for the snow ball and single-handedly destroy the buffet

i love how tyler and marcy are in the squad now :')

anemone: WHO

talib: i'm not telling u!

anemone: WHICH GIRL

talib: not a - not a. uh, girl

anemone: I RESPECT THAT ALSO

tyler, nadiya, and marcy quietly discussing alex's type LKSDJFLSJFK

sora im bout to body slam u talk to ur bf u idiot donkey don't be like teenage tedros and agatha

"akiyama sora is a dead man," muttered nadiya" i bow to one (1) queen

SORA'S GAY PANIC

chapter 29: fellas is it gay to protect roses from winter damage

"poor thing,” she added as an afterthought. alex was forcibly reminded of her aunt’s 100% Evil status"

i love these scenes with sophie <3

"er. it's okay, professor," said sora's mouth. alex for the love of christ help me you useless git, said sora's eyes"

FINALLY SORA YOUR TWO BRAIN CELLS KISSED AND EXPERIENCED COMMON SENSE

alex saying marcy has horrible taste in men but swearing to take tyler's kidneys if he doesn't go for marcy - true friendship

AWWWWHHHHHH ALEX CAME UP WITH THE IDEA FOR THE EVERGIRLS WHO DON'T WANT DATES TO GO TO THE SNOW BALL WITH ANEMONE <333333

anemone just said the f word is this legal

the amount of times i've screamed over sora nd talib is too much to count - sometimes in excitement and sometimes in pain

"he was cut off when talib seized his collar and kissed him, much harder than sora had kissed him the first time" my lungs are exploding

ANEMONE IS ME I AM ANEMONE

"sora exercised all the curse words he knew in her native language. alex grinned. "you sound like ros. except ros knows more words" oh??????????

i've smiled more reading chapter 29 than i have this whole year

sora: weren't u listening to the announcement yesterday

alex: who was doing the announcing?

sora: pollux

alex: nope

love that tedros deemed his wedding outfit a Sacred Object

i love how tedros and rosalind bond over fashion

alex has a daily ritual of high-fiving the statue of king arthur, her grandfather. i love her.

omg tedros adopting a pseudo father figure role over tyler love that

i said love so many times but i can't help it this fic is just too good

it's official: sora is alex's partner in crime

so just to catch up, the squad consists of alex, nadiya, sora, talib, tyler, marcy, and june - and out of this chaos rises a mom friend: nadi

i never knew how much i wanted to see the teachers gossiping until i got it

of course agatha never hired a nanny for her children she loves them too much to ever not raise them herself >:((((((

magazine with a pic of talib: major hottie alert!

sora: finally, some high-end journalism

kate ur mind is amazing

omg i love this curses! the musical plot point im excited

ros? as the queen of camelot? Sign Me Up

SORA ND ALEX WROTE THE SCRIPT KSJFSDLJFSLD HERE WE GO

alex is drawing a six pack on her stomach with a pen to prepare for her role as tedros somebody please help me my lungs have ruptured

title reference on a crop top!! impressive!!

"MORE PANACHE !" sophie bellowed at the stage" did soman write this or did u kate

is marcus on the autism spectrum???? it would be great if he was

"alex said a quick prayer to rosalind, patron saint of spinning half-truths to people and getting away with it"

im grinning so hard at agatha possibly dying of laughter during alex's rendition of curses! the musical

"tedros made a sound like an animal in pain and sank down so low in his seat that he was barely visible. agatha burst into hysterical cackles, reminding ros, not for the first time, that she had been raised by an actual witch" "'tedros' and 'hort' had a rap battle that ended up getting too personal and devolved into a fistfight" AGATHA AND I ARE BOTH GOING TO DIE

"she turned around, saw tedros stood behind her, and screamed. tedros held up the programme, open on the page which said rewritten by akiyama sora and alex pendragon. alex screamed louder."

i adore the news' headlines

what's on the school master's mind??????????

omg is it about marcus and ros??

YES IT IS SKFDSJFL

chinhae is ros' friend and both of their names were circled in red bc the school master has a plan for them. whoaaaaaa

"slowly, she turned back to look up at the school master's tower. and got the distinct feeling someone was meeting her gaze" chills

finished 1:06 AM june 14, 2020

#this is so LONG sorry!!!#but i just love alex vs so much#i don't read fanfics at all so this is all yall are gonna get#i mean besides kate's fanfics ofc#alex vs#sge fanfic#kate#thea reads

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

ASOIAF Fic Recs

Had an anon ask for some recs and um... yeah, I decided to post it separately because, I may have, um, gone a little overboard. Lots of different pairings involved below.

Yeah.

Born-a-Girl Fics

I have an enormous love for these stories, as it's so much fun to see how the various dynamics of the Starks, and indeed, all of Westeros change when the one thing Rhaegar was wrong about in canon becomes something he was right about after all.

All of Madrigal-in-Training's stories on AO3, her profile being located here. I'd read a few born-a-girl!Jon stories before I started reading her work and had enjoyed the genre, but after I read her stuff, I damn near became obsessed. (Did I say ‘near’? I lied, there’s no ‘near’ about it - I did become obsessed. I admit it.) Most of her fics are WiPs, but she updates fairly frequently, so her stories are definitely worth following.

The Acquaint the Flesh series, by Author376.

In a Westeros where Soulmates are bound and Marked by the Gods to bind Houses together and pay blood debts, Lyarra Snow and Oberyn Martell are about to get a shock.

The born-a-girl!Jon story to end all born-a-girl!Jon stories. I have re-read this series at least a hundred times and I still squee my head off every single time. The gods throwing together two complete opposites, an OFC who is so much fun, a Frey we can actually like, and that's barely scratching the surface! The series is also a WiP, but don't let that put you off.

And I'm calling for my mother as I pull the pillars down, by dwellingondreams.

Elia Martell becomes the Lady of Casterly Rock due to her mother's machinations. Robarra Baratheon becomes a princess due to the Mad King's obsession with finding a bride of Targaryen blood. The seeds of rebellion are planted all the same.

JFC, who knew that Elia/Tywin could be possible? Well, in a world where Robert Baratheon is born Robarra Baratheon and is quickly snatched up to be Rhaegar's wife, it seems that it is. Of course, this switch up does not prevent Aerys and Rhaegar from setting the world on fire because they're either insane or obsessed with prophecy or both. Still, the affects of this change-up are really fun.

empire (i'm building it with all i know), by willowoftheriver.

Fem!Jon Snow is discovered to be a Targaryen as a chld, triggering an unfortunate marriage.

Femslash ahoy! Viserys is still a nutjob, though. Words cannot express how much I love this two-shot series.

Oh, mercy, I implore, by SecondStarOnTheLeft.

She collects friends with the same ease she conceives healthy babes - so her goodmother tells her, something soft and wistful in her sad eyes, and Berta cannot disagree. A different crown princess, and a different world.

Jeez, but I do love these gender-flipped fics. This one is fun too. Girl!Robert isn’t taking any crap from Rhaegar, no sir.

Time-Travel or Fix-It stories

Three Tully Daughters, by ProcrastinationIsMyCrime.

Conflicts for the Iron Throne before the darkest hour led to the defeat of the living on Westeros. Jon must have known the fate of men for he’d drugged and snuck his sisters onto a ship set for Braavos. That had been the last time either Stark daughter had seen Jon. Upon Arya's death, Sansa encounters a Dornish bachelor in Braavos who by all rights should be dead. Armed with knowledge held by no other, she would sail for Westeros and save her home; for she was in the reign of Aerys II Targaryen. There would be less chaos for Littlefinger this time. Joffrey would never be born if she could help it. Cersei would never sit the Iron Throne.

A time-travel story that actually doesn't solve the insertion process by having the character in question (Sansa, in this case) be reborn into a new family. A very ASOIAF twist! I was a bit wary of the Sansa/Jaime pairing at first, but in this story it works, OMG it works. Sheer brilliance. WiP.

Valar Botis (All Men Must Serve), by sanva.

“But you, Lord Snow, you’ll be fighting their battles forever.” Ser Alliser Thorne Every time he died his last in that life he awoke again in another at the exact moment of Ghost's birth.

Jon Snow is the King of Groundhog Day. What more needs to be said? ;)

Aegon the Unlikely-era Fics

You and I conspire and split the ground, by SecondStarOnTheLeft.

Grandfather's boots are next, soft and worn where Father's are always polished to gleaming, and then Grandfather's hands, and then his face. He looks tired, under his beard, under his crown, but he is smiling when he reaches under the bed to her. "My sister Daella used hide under her bed with her dollies, when we were small," he says, his voice very quiet and very gentle. "Will you come out, poppet? Your grandmother and I would like to speak with you a little, if we may."

Wherein Aegon the Unlikely actually doesn't wash his hands of his kids and their obsession with prophecies, wherein Rhaella Targaryen is the ultimate sweetheart who deserves Nice Things, and wherein Rhaelle Targaryen is a total badass. I have a huge love of the family of Aegon the Unlikely and their antics, and this fic is a favorite of mine.

Behind the Ballads, by Ramzes.

Jenny of Oldstones and her prince were a favourite theme for singers, their romance making them larger than life. What were they like in life?

I absolutely love this behind-the-songs look into the life of Duncan the Small, and seeing just WTF he was thinking. Utterly brilliant. I'd also recommend you look at Ramzes' other work. She has at least two series about Rhaelle Targaryen, one that covers the same time frame as this one (but is not connected to this story), and one that is a series of AUs featuring what might have happened if Rhaelle had lived to the era of Robert's Rebellion. Definitely worth a look.

Coins, by ariel2me.

QUOTE SWAP: Rhaelle Targaryen + “What sort of father uses his own flesh and blood to pay his debts?”

Oh, the heart. It breaks.

Crack Fics

Ned Stark Adopts His Way Through Westeros, by witchbreaker.

"This isn't my fault." And other lies Eddard Stark tells himself.

A short fic inspired in the comments of Acquaint the Flesh, it is probably one of the funniest stories ever, not to mention adorable. Also, read the comments, as there is a hysterical little extra piece in there dreamed up by a responder and the author. The best.

A Helpful FAQ, by Siamesa.

In a world where Renly Baratheon accidentally spent the War of Four Kings on vacation in Dorne, surviving King Stannis's small council meetings takes a clear understanding of people and politics. Luckily, he's here to provide both... or so he thinks.

Ohdearlord, this one still makes me LMAO, even after having practically memorized it. Hilarious.

The Dragon and the Maiden, by modbelle.

Viserys brings the Stark girl Joffrey's head. He's surprised by her reaction to this. He'd expected her to be upset, but she seems quite delighted by this. What a strangely charming creature she is, even if she is a Stark.

Yeah, this one came out of left field for me, but holy crap who knew such a thing could somehow work?

AU Fics

Desert Wolves, by bluegoldrose.

"But Ashara’s daughter had been stillborn, and his fair lady had thrown herself from a tower soon after..." ~Ser Barristan Selmy What if Ashara's daughter lived? What if Ashara Dayne raised Jon Snow alongside her own bastard? What if Ned Stark never stopped loving Ashara even when he fell in love with Catelyn? The bastards of Lord Eddard Stark are the Desert Wolves. The true born children of Lord Eddard Stark are the Winter Wolves. Their lives are lived apart until the tides of war see fit to bring them together.

Ashara/Ned is a ship that I cling to, and one that I am always on the lookout for in regards to fics. This one is one of my favorites, particularly since neither Catelyn nor Ashara is demonized. It's a WiP, and hasn't been updated in a while, but I'm still hopeful that the last few chapters will eventually be posted.

Winter's Crown, by orphan_account.

What if Rickard Stark had other ambitions? Or, a history of the Starks, from Torrhen to Rickard, in a world where they spent two and a half centuries building up their wealth and waiting for the perfect moment to declare their independence.

A twist/expansion on all that we learned from World of Ice and Fire. Very interesting.

Lightning (Struck Before Me), by sanva.

“Send the letters,” her voice came out clear, unwavering, resolute, “request House Stark, Arryn, and Tully send representatives to treat and bend the knee.”

Wherein Jon discovers something long hidden deep in the crypts of Winterfell and everything changes. This fic is part of a series, and I'm not sure if any more will be posted for it, but this is still fun to read on its own. A mix of book and show.

Dragonstone, by Danivat.

After the death of his brother, Robert Baratheon needs a loyalist Lord on Dragonstone. He also really wants back in Ned's good graces. Or, the Game goes on after the Rebellions. The Starks still won't play, but everyone is playing the Game all around them, and Jon Sand has somehow become an important piece. Robert Baratheon, unknowingly, is the Targaryens' greatest asset.

This one could fall under either the category of AU or Crack, or perhaps both. There are quite a few divergent points, and they are listed in the notes at the start of the story so you will not be hopelessly lost. Very fun.

One Day (Is Now and Forever), by SimplexityJane.

Rhaegar takes Lyanna to Dragonstone, not Dorne.

This story had the potential to be a complete and utter epic, but it also stands wonderfully as it is.

Kingdoms at War, by deathwalker.

What if Ned Stark wasn't executed at the Great Sept of Baelor? Instead, what if, he had been removed from Kingslanding before Joffrey could give the order for his head? What impact would this have had on the Game of Thrones?

I've called this fic a "small step to the left" in the past, and it is so much fun, particularly since it’s based on a question we have all asked ourselves. Though, be prepared - this is a long one.

The Duel, by Aiur.

The duel between Robb and Joffrey goes differently than anyone predicts.

Be prepared to shed a few tears here. That’s all I’m sayin’.

The Dragon’s Queen, by orphan_account.

Aerys married his eldest son off to Elia Martell immediately after Viserys's birth instead of sending his cousin to Essos, and she bore Rhaegar three children before dying in labor with the last. Rhaegar is therefore a young widower when he crowns Lyanna Stark the Queen of Love and Beauty during the tourney at Harrenhal, and Aerys decides that his son will marry the lady. Here are seven letters Lyanna Stark sent in another world.

I really love epistolary stories, and this one is so interesting. I wish there was more of it, because it hints at so much more. Very fun.

But you are of the North, by LuminaCarina.

Ned Stark doesn’t visit from the Eyrie. Brandon, Lyanna and Benjen adjust.

Very interesting idea.

The Squire of Dragonstone, by EmynIthilien.

Instead of joining the Night's Watch, Jon travels south to squire for Stannis on Dragonstone. Roughly spanning the events of A Game of Thrones through A Storm of Swords, Stannis and Jon investigate the royal incest mess, fight battles in and out of the courtroom, attend a joyous wedding, and come to rely on each other more than they ever expected.

I call this one “Sherlock!Stannis and Watson!Jon”. A great trilogy of stories where things are actually taken care of, and in a legal-ish way!

The Lady of Storm’s End, by Sarah_Black.

Sansa was supposed to marry someone brave, gentle and strong. Lord Stannis Baratheon was not what she had in mind. Or: The one where Sansa is never betrothed to Joffrey, never loses Lady, and only comes to King's Landing to attend King Robert's wedding feast. The king is marrying Margaery Tyrell as Cersei's treason has been exposed and dealt with. But things are never simple when the Iron Throne is in desperate need of heirs and wildlings threaten the peace...

Another pairing that is a bit weird, but the author makes it work beautifully! The story is also inspired by The Squire of Dragonstone listed above, though it is not necessary to read it. The author explains anything you need to know in the opening notes.

broken lovers series, by soapboxblues.

wherein rhaegar wins the war, and jaime manages to keep his head by taking a stark for a wife

I never knew Lyanna/Jaime could somehow be possible, but this series proved it to me. There are so many wonderful things about this series, I can’t even.

Kindness, Not Fear, by SecondStarOnTheLeft.

In the wake of Daenerys' triumph, Sansa comes to King's Landing. Multi-POV post-series short fic.

An older story, but one that I still love to pieces.

The Lion Queen, by Laine.

I am the first of my kind, and the bards will sing of me for centuries after I'm gone. Ned Stark takes the Iron Throne, and he intends to share it with his Queen.

Yeah, pretty sure I was going to hell for liking this pairing, but nonetheless, I do love it. Plus, a non-crazy Cersei. How often do we see her?

I Fear No Fate (For You Are My Fate, My Sweet), by vixleonard.

Myrcella Baratheon always knew she would be married to a man for a political alliance. What she did not know was that she was going to be left in the North at 8-years-old to one day become the wife of Robb Stark and just how much it would change her life.

I think this was one of the first ASOIAF fics that I bookmarked, and I still come back to it from time to time. A classic.

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey you can make some recommendations of snarry with time travel?

Oh, I love asks like this! Thank you, luv!I have read countless genres, and time travel is always a favourite of mine. I don’t know if these are classics or anything, or if they’ve been mentioned a million times already, but these are the ones I’ve read time and again and love more and more every time. I hope you enjoy!

Also, sorry I talked so much. I’m just really passionate about the fics I love, I suppose, haha!

The Care of Infants by Perfica (13k+ words | complete)

A curse from Voldemort regresses Harry to infancy. Snape must protect him while the Order tries to find a way to reverse the spell.

This isn’t exactly time travel, but I use every excuse I can to talk about this story because it was one of my firsts and still one of my favourites to this day. It’s an age-regression piece, so it’s time travel-esque because Harry’s a different age, maybe? It’s just so good and such a beautiful story between these two. Sorry, haha, I’ll get to the legitimate time travel ones after this, don’t worry.

A Place Between Sleep and Waking by r_grayjoy (28k+ words | complete)

More than a year after Voldemort’s defeat, Harry is still having nightmares about Snape’s death. When his dreams gradually begin to change, so do his perceptions. Ultimately, Harry discovers that when one lives in both the past and the future, it’s difficult to find one’s present.

This is a strange twist on ‘time travel’ as it begins with Harry travelling somewhere in his dreams and slowly becoming more corporal and such. It’s a fascinating, powerful, and beautiful love story between him and a younger, impressionable, and lonely Severus. I highly recommend it. One of my favs!

Rapture by mia_ugly (48k+ words | complete)

Snape sees the man, for the first time, on his twenty-fifth birthday.

Now, this is a classic. At least, I think it is. This seems like such a famous one for me, and it’s well-deserved. It’s a very beautiful story (I’m probably going to say that for all of them). It’s a tad confusing, with the shifts in time and the back-and-forth, but it’s so worth it. Their love is so intense, and the physics of it is so intriguing. I read it all in one sitting, which is not something I usually do for a fic this long. Great, great read, a must in this community.

Between the Lines by Dementordelta (22k+ words | complete)

Harry discovers a secret in his Potions text and a friend in the Half-Blood Prince.

Okay, I’m really excited because I just found this in the depths of my bookmarked works, and I remembered just how good it was! This is another iffy one because it’s not technically time travel, but present-age Harry is communicating with a younger Severus, so it still counts to me. Give this one a chance for sure, because it’s so sweet. It’s very angsty, since it’s set just before and during the battle, so just be warned. Something to note with me, though, all of my recs will have a happy ending of some sort. I don’t like unsatisfying or sad ones.

This Time of Ours by emynn (35k+ words | complete)

Severus Snape wasn’t supposed to die. Neither was Harry Potter.

Oh my god, this one. This is absolutely incredible. One of the best. It’s such a unique and imaginative story, and their love is so precious. You can literally feel it with every word, it’s so obvious that they cherish each other. The story itself, like, aside from the romance is also fascinating. There’s a very cool mystery that has a lot of twists and turns to figure out, and the story is written so whenever you think you have the answer, you’re just as mistaken as the characters themselves. Fabulous read.

Escaping the Paradox by Meri (35k+ words | complete)

After Harry is thrown back in time to 1971, he has several choices to make.

This is another brilliant piece. It’s quintessential Snarry time travel. I always have a soft spot for younger Severus and Older Harry, it’s just such a strange and fun dynamic. And trust me, this Severus is still the same ol’ Sev. It’s so full of humour, canon story references, and sweet love. It’s a very satisfying read, I have nothing bad to say about it.

Perfect Shapes by Ashii Black, littleblackbow (49k+ words | complete)

When Harry is accidentally sent back to Hogwarts 1982, he discovers a more bitter and angrier Snape than he knew in his school years. Tasked by Dumbledore with teaching Defense Against the Dark Arts and befriending Snape, as well as finding out how to get back, Harry knows he is in store for a difficult year. Despite their arguing, Harry can’t help but find himself drawn to Snape. If Harry and Snape can get over their past and learn to be just a little selfish, their relationship may stand a chance.

This. This. THIS. God, this one has such a special place in my heart. These four chapters ripped my soft little heart apart. It was so good. The boys really struggle in this one, but the more intensely they fight, the more intensely they love. They are meant for each other in every way here, and it’s leaves you with such a good feeling. Couldn’t recommend this more, it’s, well…perfect.

My Name is Cameron Sage by thesewarmstars (41k+ words | complete)

Things are going poorly for the side of the light, and in a last-ditch effort to fulfill his destiny, Harry goes back in time to try again.

This is one I’ve admittedly only read through once. I really need to read it again and experience this delightful story once more. This was is definitely fluffier than the others. The ending, oh, it makes me just melt. The boys are absolute fools in love, and it’s just too good. I love this story, and it looks a lot longer than it is. Nineteen chapters went by in an instant for me.

Original Sin by Dementordelta (14k+ words | complete)

Leave it to Harry Potter to interfere with every aspect of Severus Snape’s life–and death.

This is completely not at all as morbid as it might sound! It’s not exactly time travel, but Severus and Harry both died and are in an Eden-esque setting, which is good enough for me. This one is way happier than a lot of this lot, despite its summary. It’s actually quite fun, and Death (yes, Death is a character) is absolutely hysterical. This fic is worth the read just for him, if I’m honest. It’s all good, but I love a smutty, comedic fic that doesn’t take itself so seriously. Not cracky, though, just funny.

Back In Time by Snarry5evr (26k+ words | complete)

After Nagini’s attack Severus wakes to find himself in an impossible future. Married to The Boy Who Lived, Severus sets out to discover a way to keep himself from making the same mistake twice, because surely no sane version of Severus Snape would EVER fall in love with the arrogant brat.

Another hidden gem I had forgotten about until just now. This one was always so intriguing! The slightly confusing angst still tugs at my heartstrings on the beginning, but seriously, the love story here is so beautiful. Severus relearning just why he fell in love with Harry Potter is just… There’s nothing better. Very, very touching story.

Time and Time Again by Mottlemoth (41k+ words | complete)

It’s eleven days since the fall of The Dark Lord - and Harry still can’t look away.Canon-compliant Snarry slash. (No, really.)

Luv, I really have to thank you for this ask because it’s reminding me of so many lovely stories I haven’t read in ages! This one is definitely a strange one, but in a good way. Like the summary states, it’s canon-compliant Snarry. Stuff like that just butters my eggroll, it really does. The writing is absolutely incredible, and I can’t dany that I’m so, so, so in love with this love story. It’s some good slow-burn, and it’s worth every second of reading and waiting.

Decade by gryffindorJ (27k+ words | complete)

Harry told him. Harry simultaneously felt the burden of his secret lift and the weight of what this would mean for Severus collapsed in on him. Severus certainly would be able to help and, at the same time, he was sure to feel betrayed that Harry was only telling him now.

This is a new one in my collection, so again, I’ve only read it once. However, it was fan-tas-tic. Literally, I couldn’t stop reading. I was so fascinated by Harry’s grief and mourning process. Every character was so developed and so well-written, I loved every second of it. Bittersweet, but very hopeful ending as well, which is all I need. As long as they’re together, anything is possible for these two lovebirds.

And finally, one of my most beloved, most cherished, most reread fanfictions ever…

Waiting to Divide by emynn (22k+ words | complete)

Harry always thought soul mates were the domain of overly-soppy romantics. What he didn’t realise was that they were very real, very dangerous, and very inconvenient…especially when your soul mate is the very dead Severus Snape. Fortunately, with the help of his friends and a Time Portal, he’s able to get past that pesky obstacle…and finds his life completely changed.

I’m not going to go super in depth about this one because you’ll never shut me up if I do that. Let me just say: read this one. If you read nothing else on this list, please, please read this one. It is so worth it. Soulmates and time travel? Ugh, it’s so good. Their love is so powerful and so beautiful, I cannot get enough of the two of them. It also follows the canon storyline (obviously, from the ‘very dead Severus Snape’ line), so the angst is strong in the one. But stick with it, it’s such a satisfying read.

Okay, well…oops. I didn’t mean to go super crazy here, but I just got inspired and wanted to give you (and anybody seeing this) lots of options. I hope you find ones you love, and thank you so, so much for this ask! I really appreciate the opportunity to give my two cents to this lovely community. xx

393 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maybe One Day - Part 3

A collection of one-shots of Jay Halstead as a dad. Because we all need that in our lives. Co-written with @halsteadpd

When canon gives you lemons, you make fluff…

In case you missed it: Part 1, Part 2

Christmas had been Jay’s favourite holiday for as long as he could remember, and he had always hoped to instill that same joy in his own children one day. Erin didn’t have the happiest holiday memories, but she wanted to give her children the childhood she hadn’t been lucky enough to have herself. Together, Jay and Erin were determined to create the perfect Christmas for their own family.

They had trudged through the heavy December snow to cut down a tree, and Jay had a childlike gleam in his own eyes as he and Ben decorated it together. Technically it was their firstborn’s second Christmas, but it was the first that he would truly remember; they wanted to make it special. At fifteen months old, Ben was just starting to show excitement at stories of Santa Claus and talk of opening presents.

Erin was curled up on the couch with newborn Zachary William Halstead nestled against her chest, beaming with pride as she watched Jay and Ben interact. She honestly couldn’t tell who was more excited, father or son.

“Okay buddy, time for the finishing touch,” Jay announced, pulling the last decoration from the box and lifting Ben up onto his shoulders. He placed it in his son’s hand and helped him to guide the twinkling star to its rightful place at the top of their tree. “Awesome job little man! Now remember, just like I showed you,” he made a fist and held it to Ben. The toddler mimicked his father’s action and giggled when Jay pushed his large fist against Ben’s smaller one. Hearing the little boy’s laughter had Jay grinning from ear to ear.

“Wait! Before you put him down I want to take a picture,” Erin exclaimed from her perch on the couch as she grabbed her phone from the coffee table. Jay turned to face her, he and Ben with matching smiles etched on their faces.

Jay pulled Ben down from his shoulders and perched him on his hip. “Well little man, we should probably get you to bed! You’ve got a big day tomorrow—are we going to see Santa?” Jay’s smile grew as he spoke; he and Erin had been trying to build their older son’s excitement for Santa for weeks in anticipation.

“Jay, let me put him to bed? I feel like I haven’t been spending enough time with him now that the new baby is here,” Erin bit her lower lip, clearly feeling guilty.

“Sure thing babe, gives me some time with my littlest dude!” Jay and Erin effortlessly exchanged children. Going from one child to two had been overwhelming at first, but they had really found their groove in the last couple of days. Erin started toward Ben’s bedroom when Jay spoke again, “Hey Er? Ben is so happy and he loves you so much. You have absolutely nothing to feel bad about babe.”

Jay had read her like a book, as usual. His words reassured her, and a smile appeared across Erin’s face. “You’re amazing.”

“Oh yeah,” He winked as Erin moved back into the room to kiss him before taking Ben to bed.

Jay sunk down into the couch with baby Zachary in his arms. At only two weeks old, he was so tiny—Jay had forgotten how small newborns were. “Hey Zach-man, it’s just you and me for a little bit,” he cooed, smiling with pride as ran his finger along the baby’s cheek. “Mommy and Daddy and Ben love you so much, we’re so happy you’re finally here with us. Just in time for Christmas. I know you’ll probably sleep through most of it, but it’s going to be so much fun to all be together as a family.” Jay leaned down to place a soft kiss on the newborn’s forehead; he couldn’t believe how lucky he was.

As Erin made her way back into the living room, she paused and leaned against the doorway, completely entranced by Jay holding and talking to their new baby. Her heart swelled at the sight; seeing her big strong husband be so gentle with their babies made her love him even more than she ever thought possible. It was mesmerizing.

The next day was the unit’s Christmas celebration. From the way Jay and Erin had loaded up, you’d think they were leaving for a month, not just heading down to the district for the afternoon. “Hey babe, do you think we’re bringing enough stuff?” Jay asked sarcastically, smirking as he surveyed the mountain of Christmas gifts and baby and toddler gear that had filled their vehicle.

Erin just laughed in response, playfully swatting at Jay as she moved to buckle Ben in; Zach was already fast asleep in his own car seat.

They enjoyed a comfortable silence for the first few minutes of the ride. The boys were both sleeping in the back, and Jay held Erin’s hand in his as he drove his family toward the district.

As they pulled into the parking lot, Erin broke the silence: “Do you think Ben will be scared?”

“Of Santa? No way! Honestly I think we should be more worried that he’ll recognize that it’s Adam under that beard and hat—now that would be enough to scare anyone.” Jay was trying to ease his wife’s worries, but secretly he too was feeling anxious about their older son’s reaction to his first visit with Santa. Ben was still shy around new people.

Zach’s stirring in the backseat pulled his parents from their thoughts.

“Oh, he probably needs to be changed,” Erin murmured, unbuckling her seatbelt and reaching for the door.

“I’ve got it babe,” Jay offered with a smile. “Why don’t you and Ben take some of these presents inside? The little guy and I will join you in a minute?”

Not only did this plan give Erin some extra time with Ben, Jay was excited at the prospect of being the one to show the new baby off to everyone. Voight had been at the hospital when Erin delivered, and several of their colleagues had visited in the last two weeks, but this was Zach’s first visit to the district, his first time meeting their entire District 21 family.

“Ho, ho, ho Merry Christmas!” Adam’s fake Santa voice caught the attention of everyone in the room. The guys were all trying their best not to burst out laughing—Adam looked even more ridiculous than usual.

Some of the children seemed excited, while others were completely terrified. Emily, Kim and Adam’s eight-month-old daughter, immediately recoiled into the safety of her mother’s arms, and away from the strange bearded man approaching her. Adam looked down at his daughter with concern before glancing around the room. Jay had a smirk on his face and Adam just knew that if the kids weren’t around, Jay would absolutely be calling him out for scaring his own child.

“Who wants to sit on Santa’s lap?” Adam asked as he sat down in the chair at the front on the room. A chorus of “Me!” was cheered.

After the older children had all taken their turn, Kim approached Adam with their daughter. Emily had been calm, but the moment she realized where they were headed, she started fussing all over again; she kicked and screamed as her mother handed her off to the strange man. “Aw, what’s got you so upset Ems?” Adam bounced his daughter on his knee as he held her little waist. Upon recognizing her father’s voice, the little girl’s tears stopped. She gazed up at him and cooed. “There’s that smile. I know exactly what you want for Christmas.” Kim snapped a photo on her phone while their baby was still smiling and happy. He nuzzled her nose with his and placed a kiss on her forehead before handing her back to Kim.

“You ready little man?” Jay walked towards Adam with Ben in his arms. He watched his son take in the man decked out in red and white. Ben held his father’s shirt tighter in his little fists as they got closer.

“No! Dada, no!” Tears had pooled in his blue eyes, clouding his vision. He burrowed his face into Jay’s neck hoping that his father wouldn’t let the strange man get any closer.

“It’s okay, it’s just Santa. He wants to say hello and find out what you want for Christmas.”

“Dada no.” Ben whined.

“Don’t you want Santa to bring you any presents?” Jay asked desperately.

Ben’s cries grew louder. “No, no, no!”

Jay glanced over at Erin who was standing by, ready to photograph the moment. Her face was full of concern as she eventually shrugged at her husband. Neither of them wanted to traumatize Ben; it looked like a visit with Santa might have to wait until next year.

But Jay was determined; he pulled Ben closer to his chest and started moving even faster to where Adam was sitting. “It’s okay buddy, Daddy’s here, it’s going to be okay little man.” Before he could give it another moment’s hesitation, Jay sat right down on Adam’s lap. “Don’t say a damn word Ruzek,” Jay hissed out of the corner of his mouth.

“There’s like a million things I could say right now,” Adam muttered as he wrapped his arm around Jay, trying to ignore the irritation radiating from his friend.

Ben was noticeably calmer with his father there, but Adam could still sense his discomfort; he tickled Ben’s arm to get his attention. When the little boy’s eyes were on him, Adam tugged his beard down a little, revealing his true identity with a wink.

With Ben finally looking cheerier, Jay plastered a smile on his face and motioned for Erin to take the picture. He rose from Adam’s lap the instant she had finished.

Erin was laughing hysterically when Jay reached her side.

“I hope it’s a damn good picture. I swear to God if I sat on Ruzek’s lap for nothing—”

“Oh babe, this is the best gift ever,” Erin laughed even louder as she reached to swipe at the tears forming in her eyes.

“Let me see!” Jay demanded, reaching to try to snatch the phone from Erin’s hand as she continued to giggle at him. He grabbed the phone and looked down at the screen, his eyes scanned the picture; Jay was the only one looking at the camera as he sat perched on Adam's knee. Ruzek was looking over at Ben, his fake beard hanging haphazardly and a smile plastered on his face. Ben was in the middle of a deep belly laugh, his eyes squinted from excitement as he reached one of his little hands over to his Uncle Adam. Jay smiled at the photo; although his son wasn’t looking directly at the camera as he had hoped, Ben was still happy. And that’s all Jay could ask for.

Voight approached Jay and Erin, rocking their sleeping baby in his arms. “Hey Halstead, isn’t it Zachary’s turn?” He chuckled as he walked off with the newborn, shaking his head at the look on Jay’s face. Even after all these years he still loved messing with his son-in-law.

“I’m not sitting on Adam’s lap again. Never again Erin,” Jay had a serious look on his face.

“Oh please, you would do it again in a heartbeat to make your babies happy,” Erin smiled at Jay as she reached up to run her hand along his chest, giving his pec a little squeeze. “Besides,” she leaned closer to whisper in his ear, “I’ll sit on your lap later.”

Jay’s eyes darkened and his jaw went slack, “You just gave birth, Erin, don’t tease me.”

“True,” Erin shot Jay a pointed a look before continuing, “but that doesn’t mean I can’t find other ways to make it worth your while.” She smiled at him before bending to pick up Ben, walking away from him with a little extra sway in her hips.

As he watched her walk away with their son, he couldn’t help but think that this was going to be his best Christmas yet. Jay had never thought it would be possible to love Erin more than he already did, but seeing her as a mother to their children? She was absolutely incredible.

Jay’s thoughts drifted to his own mother, and how she was surely watching over him and the life he had created, the amazing family he was building. He reminisced about holidays cuddled up by the fireplace under a warm blanket, drinking hot chocolate, and telling Christmas stories. His smile grew larger as he thought about sharing those same magical moments with his own children one day.

We have a list of ideas for this story, but if there is anything specific you would like to see, please let us know and we’ll add it to the list! We will be jumping all over time writing these little snippets of Jay Halstead as a father.

Please let us know what you think! ❤

#writing: maybe one day#linstead fanfiction#linstead#linstead au#chicago pd#cpd fanfiction#erin x jay#jay x erin#jay halstead#erin lindsay#maybe one day#halsteadpd#mine#ours#fluffy#daddy jay#christmas in september#because we can#fanon over canon#burzek#adam ruzek#kim burgess#hank voight#my writing

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

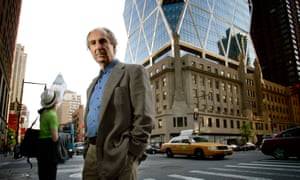

'Savagely funny and bitingly honest' – 14 writers on their favourite Philip Roth novels

New Post has been published on https://funnythingshere.xyz/savagely-funny-and-bitingly-honest-14-writers-on-their-favourite-philip-roth-novels/

'Savagely funny and bitingly honest' – 14 writers on their favourite Philip Roth novels

Emma Brockes on Goodbye, Columbus (1959)

I fell in love with Neil Klugman, forerunner to Portnoy and hero of Goodbye, Columbus, Philip Roth’s first novel, in my early 20s – 40 years after the novel was written. Descriptions of Roth’s writing often err towards violence; he is savagely funny, bitingly honest, filled with rage and thwarted desire. But although his first novel rehearses all the themes he would spend 60 years mining – sexual vanity, lower-middle-class consciousness (“for an instant Brenda reminded me of the pug-nosed little bastards from Montclair”), the crushing weight of family and, of course, American Jewish identity – what I loved about his first novel was its tenderness.

Goodbye, Columbus is steeped in the nostalgia only available to a 26-year-old man writing of himself in his earlier 20s, a greater psychological leap perhaps than between decades as they pass in later life. Neil is smart, inadequate, needy, competitive. He longs for Brenda and fears her rejection, tempering his desire with pre-emptive attack. All the things one recognises and does.

My mother told me that the first time she read Portnoy’s Complaint she wept and, at the time, I couldn’t understand why. It’s not a sad novel. But, of course, as I got older I understood. One cries not because it is sad but because it is true, and no matter how funny he is, reading Roth always leaves one a little devastated.

I picked up Goodbye, Columbus this morning and went back to Aunt Gladys, one of the most put-upon women in fiction, who didn’t serve pepper in her household because she had heard it was not absorbed by the body, and – the perfect Rothian line, wry, affectionate, with a nod to the infinite – “it was disturbing to Aunt Gladys to think that anything she served might pass through a gullet, stomach and bowel just for the pleasure of the trip”. How we’ll miss him.

Emma Brockes is a novelist and Guardian columnist

James Schamus on Goodbye, Columbus (1959)

Philip Roth was more than capable of the kind of formal patterning and closure that preoccupied the work of Henry James, with whom he now stands shoulder-to-shoulder in the American literary firmament. So yes, one can always choose a singular favourite – mine is the early story Goodbye, Columbus, though I know the capacious greatness of American Pastoral probably warrants favourite status. But celebrating a single Roth piece poses its own challenges, in that his life’s work was a kind of never-ending battle against the idea that the great work of fiction was anything but, well, work – work as action, creation; work not as noun but as verb; work as glorious as the glove-making so lovingly described in Pastoral, and as ludicrous as the fevered toil of imagination that subtends the masturbatory repetitions of Portnoy’s Complaint. Factual human beings are fiction workers – it’s the only way they can make actual sense of themselves and the people around them, by, as Roth put it in Pastoral, always “getting them wrong” – and Roth was to be among the most dedicated of all wrong-getters, his life’s work thus paradoxically a fight against the formal closure that gave shape to the many masterpieces he wrote. Hence the spillage of self, of characters real and imagined, of characters really imagining and of selves fictionally enacting, from work to work to work. So, here, Philip Roth, is to a job well done.

James Schamus is a film-maker who directed an adaptation of Indignation in 2016

I read it when I was about 18 – an off-piste literary choice in my sobersided studenty world. I had been earnestly dealing with the Cambridge English Faculty reading list and picked up Portnoy having frowned my way through George Eliot’s Romola. The bravura monologue of Alex Portnoy wasn’t just the most outrageously, continuously funny thing I had ever read; it was the nearest thing a novel has come to making me feel very drunk.

And this world-famously Jewish book spoke intensely to my timid home counties Wasp inexperience because, with magnificent candour, it crashed into the one and only subject – which Casanova, talking about sex, called the “subject of subjects” – jerking off. The description of everyone in the audience, young and old, wanking at a burlesque show, including an old man masturbating into his hat (“Ven der putz shteht! Ven der putz shteht! Into the hat that he wears on his head!”) was just mind-boggling. A vision of hell that was also insanely funny. Then there is his agonised epiphany at understanding the word longing in his thwarted desire for a blonde “shikse”. (Was I, a Wasp reader, entitled to admit I shared that stricken swoon of yearning? Only it was a Jewish girl I was in love with.) Portnoy’s Complaint had me in a cross between a chokehold and a tender embrace: this is what a great book does.

Peter Bradshaw is the Guardian’s film critic

William Boyd on Zuckerman Unbound (1981)

Looking back at Philip Roth’s long bibliography, I realise I’m a true fan of early- and middle-Roth. I read everything that appeared from Goodbye, Columbus (I was led to Roth by the excellent film) but then kind of fell by the wayside in the mid 1980s with The Counterlife. As with Anthony Burgess and John Updike, Roth’s astonishing prolixity exhausted even his most loyal readers.

But I always loved the Zuckerman novels, in which “Nathan Zuckerman” leads a parallel existence to that of his creator. Zuckerman Unbound (1981) is the second in the sequence, following The Ghost Writer, and provides a terrifying analysis of what it must have been like for Roth to deal with the overwhelming fame and hysterical contumely that Portnoy’s Complaint provoked, as well as looking at the famous Quiz Show scandals of the 1950s. Zuckerman’s “obscene” novel is called Carnovsky, but the disguise is flimsy. Zuckerman is Roth by any other name, despite the author’s regular denials and prevarications.

Maybe, in the end, the Zuckerman novels are novels for writers, or for readers who dream of being writers. They are very funny and very true and they join a rich genre of writers’ alter ego novels. Anthony Burgess’s Enderby, Updike’s Bech, Fernando Pessoa’s Bernardo Soares, Ernest Hemingway’s Nick Adams, Edward St Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose and so on – the list is surprisingly long. One of the secret joys of writing fictionally is writing about yourself through the lens of fiction. Not every writer does it, but I bet you every writer yearns to. And Roth did it, possibly more thoroughly than anyone else – hence the enduring allure of the Zuckerman novels. Is this what Roth really felt and did – or is it a fiction? Zuckerman remains endlessly tantalising.

William Boyd is a novelist and screenwriter

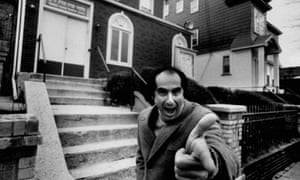

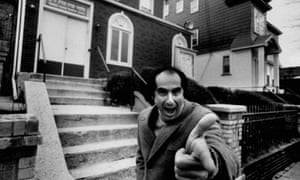

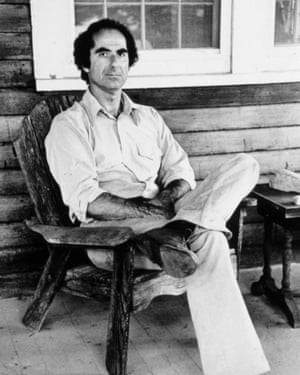

Roth outside the Hebrew school he probably attended as a boy. Photograph: Bob Peterson/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

David Baddiel on Sabbath’s Theater (1995)

Philip Roth is not my favourite writer; that would be John Updike. However, sometimes, on the back of Updike’s – and many other literary giants – books, one reads the word “funny”. In fact, often the words “hilarious”, “rip-roaring”, “hysterical”. This is never true. The only writer in the entire canon of very, very high literature – I’m talking should’ve-got-the-Nobel-prize high – who is properly funny, laugh-out-loud funny, Peep Show funny, is Philip Roth.

As such my choice should perhaps be Portnoy’s Complaint, his most stand-uppy comic rant, which is gut-bustingly funny, even if you might never eat liver again. However – and not just because someone else will already have chosen that – I’m going for Sabbath’s Theater, his crazed outpouring on behalf of addled puppeteer Mickey Sabbath, an old man in mainly sexual mourning for his mistress Drenka, which could anyway be titled Portnoy’s Still Complaining But Now With Added Mortality. It has the same turbocharged furious-with-life comic energy as Portnoy, but a three-decades-older Roth has no choice now but to mix in, with his usual obsessions of sex and Jewishness, death: and as such it becomes – even as we watch, appalled, as Mickey masturbates on Drenka’s grave – his raging-against-the-dying-of-the-light masterpiece.

David Baddiel is a writer and comedian

Hadley Freeman on American Pastoral (1997)

American Pastoral bagged the Pulitzer – at last – for Philip Roth, but it is not, I suspect, his best-loved book with readers. Aside from his usual alter ego Nathan Zuckerman, the characters themselves aren’t as memorable as in, say, Portnoy’s Complaint, or even Sabbath’s Theater, which Roth wrote two years earlier. And yet, of all his books, American Pastoral probably lays the strongest claim that Roth was the great novelist of modern America.

Zuckerman, who is now living somewhere in the countryside, his body decaying in front of him, remembers a friend from high school, Seymour Levov, known as “the Swede”, who seemed to have everything: perfect body, perfect soul, perfect family. But then the Swede’s life is shattered when his daughter, Merry, literally blows up all of her father’s dreams, by setting off a bomb during the Vietnam protests and killing someone. The postwar generation has rejected all that their parents built for them, and while Roth uses the Levov families as symbols for America’s turmoil, they are far more subtly realised than that. And in a terrible way, now that school shootings – almost invariably done by young people – are an all-too-common occurrence in America, the bafflement the Swede feels about Merry seems all too relevant. “You wanted Miss America? Well, you’ve got her, with a vengeance, she’s your daughter!” the Swede’s brother famously shouts at him. In today’s America, more divided and gun-strewn than ever, it’s a line that still chills.

Hadley Freeman is an author and Guardian columnist

Hannah Beckerman on American Pastoral (1997)

By the time I read American Pastoral I was a 22-year-old diehard Roth fan. But no book of his that I had read previously – not the black humour of Portnoy’s Complaint, nor the blistering rage of Sabbath’s Theater – had prepared me for this raw and visceral dismantling of the American dream. With Seymour “Swede” Levov – legendary high school baseball player and inheritor of his father’s profitable glove factory – Roth presents us with the classic all-American hero, before unpicking his life, stitch by painful stitch. Swede’s relationship with his teenage daughter, Merry – once the apple of his eye, now an anti-Vietnam revolutionary who detonates Swede’s comfortable life – is undoubtedly one of the most powerful portrayals of father-daughter relationships anywhere in literature. But this is Roth, and his lens is never satisfied looking in a single direction. Through the downfall of Swede Levov, Roth portrays the effects of the grand narratives of history on the individual, and questions our notions of identity, family, ambition, nostalgia and love. Muscular and impassioned, American Pastoral oscillates seamlessly between rage and regret, all in Roth’s incisive, fearless prose. It is not just Roth’s best book: it is one of the finest American novels of the 20th century.

Hannah Beckerman is a novelist, journalist and producer of the BBC documentary Philip Roth’s America.

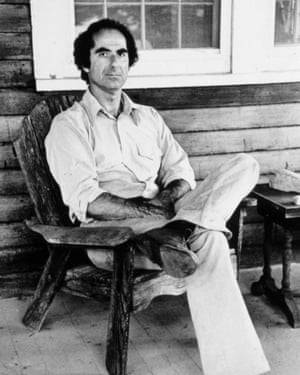

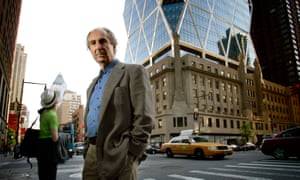

Roth in 1977. Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

Xan Brooks on I Married a Communist (1998)

Great novels hit you differently each time you revisit them, but a second reading of I Married a Communist felt like being flattened by a steamroller. For decades I had cast this as the brawling bantamweight of Roth’s American trilogy; bookended by the more polished American Pastoral and The Human Stain, and bent out of shape by the author’s personal animus towards ex-wife Claire Bloom (thinly veiled as Eve Frame, a self-loathing Jewish actor). These days, I think it may well be his best.

I Married a Communist charts the rise and fall of Ira Ringold, a leftist radio star who finds himself broken on the wheel of the 1950s red scare. Fuelled by righteous fury, it’s one of the great political novels of our age; a card-carrying Shakespearean tragedy with New Jersey dirt beneath its fingernails. And while the tale is primarily set during the McCarthy era, it tellingly bows out with a nightmarish account of Nixon’s 1994 funeral in which all the old monsters have been remade as respected elder statesmen. “And had Ira been alive to hear them, he would have gone nuts all over again at the world getting everything wrong.”

Xan Brooks is a novelist and journalist

Arifa Akbar on The Human Stain (2000)

I read The Human Stain when it was published in 2000. I was in a book club comprised of gender studies academics, gay women, women of colour. No men allowed. We had been reading bell hooks, Jamaica Kincaid and along came Philip Roth. I expected it to be savaged. I expected to do the savaging, having never read Roth before, precisely because of his much-disputed misogyny.

Then I read it, this tender, shocking and incendiary story on the failure of the American dream refracted through the prism of race, blackness and the alleged racism of Coleman Silk, a 71-year-old classics professor who embarks on an affair with a cleaner half his age, as if by way of consolation.

Here we go, I thought, and raised an eyebrow when she danced for this priapic old fool. But The Human Stain is much more than that single scene. Here was a Jewish American writer, taking on black American masculinity, filling it with its legacy of oppression, the perniciousness of the internalised white gaze, the “shame” that Silk feels that leads him to his lifetime’s masquerade. In less masterful hands, it could have read as dreadful appropriation.

I have re-read it since and it feels just as contemporary, like all great works of literature. It sums up so much about desire and ageing, but also institutionalised racism, the dangers of political correctness and colourism that we are increasingly talking about again.

Yes, we spoke of that dancing scene at our book club, but forgave it. There is something profoundly honest in the sexual dynamic between The Human Stain’s lovers. Roth caught male desire so viscerally and entwined it within the nexus of vulnerability, fear and the fragile male ego. I read the other Nathan Zuckerman novels afterwards and realised that you don’t go to Roth to explore female desire, but you read him for so much else.

Arifa Akbar is a critic and journalist

Jonathan Freedland on The Plot Against America (2004)

Rarely can a four-word note scribbled in the margin have born such precious fruit. In the early 2000s, Roth read an account of the Republican convention of 1940, where there had been talk of drafting in a celebrity non-politician – the superstar aviator and avowed isolationist Charles Lindbergh – to be the party’s presidential nominee. “What if they had?” Roth asked himself. The result was The Plot Against America, a novel that imagined Lindbergh in the White House, ousting Franklin Roosevelt by promising to keep the US out of the European war with Hitler and to put “America First”.

The result is a polite and gradual slide into an authentic American fascism, as observed by the narrator “Philip Roth”, then a nine-year-old boy who watches as his suburban Jewish New Jersey family is shattered by an upending of everything they believed they could take for granted about their country.

The book is riveting – perhaps the closest Roth wrote to a page-turning political thriller – but also haunting. Long after I read it, I can still feel the anguish of the Roth family as they travel as tourists to Washington, DC and feel the chill of their fellow citizens; eventually they are turned away from the hotel where they had booked a room, clearly – if not explicitly – because they are Jews. Like Margaret Atwood’s Gilead, the America of this novel stays in the mind because of the plausible, bureaucratic detail. Philip’s older brother is packed off to Kentucky under a programme known as Homestead 42, run by “the Office of American Absorption”, whose mission is to smooth off the Jews’ supposed rough edges, so that they might dissolve into the American mainstream, or perhaps disappear altogether.

It is not a perfect novel. The final stretch becomes tangled in a rush of frenetic speculations and imaginings. But it has an enduring power, which helps explain why the election of Donald Trump – who has often repeated, without irony or even apparent awareness, the slogan “America First” – had readers turning back to The Plot Against America, to reflect on how a celebrity president blessed with a mastery of the modern media might turn on a marginalised minority to cement his bond with the American heartland. Nearly 70 years after Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here, Roth insisted that it could – and he detailed precisely how it would feel if it did.

Jonathan Freedland is an author and a Guardian columnist

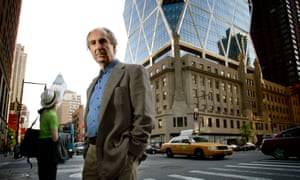

Roth in New York City. Photograph: Orjan F. Ellingvag#51SY ED/Getty Images

Linda Grant on Nemesis (2010)

After Philip Roth published The Plot Against America in 2004 and came to the end of the great sequence of long, state-of-the-USA novels beginning with Sabbath’s Theater, which were his brilliant, late, but not last period, he published a number of short novels that felt like a coda to the main body of work. They centred round the ageing, dying male, the declining libido, old age all alone. Then, with a final surprising flick of his fingers, he wrote Nemesis, returning to his youth in postwar Jewish Newark where it all starts. He uncovered one last story, the forgotten epidemic of polio that affected mainly children and young adults and whose malevolent transmission was the subject of conspiracy theories, a population blaming, as ever, the Jews.

It is the story of aspiring heroes and their moral failure, the lifelong consequences of striving to do the right thing and disastrously doing something so wrong you become trapped in a carapace of guilt. With his protagonist Bucky Cantor, Roth encapsulates his fascination with the heroic generation of Jewish kids destined for great things, and the ones who failed. Though I’ve read all of Roth, it’s the novel I’m most likely to recommend to absolute beginners to his work. It’s him in miniature, yet perfectly whole.

Linda Grant is a novelist

Alex Ross Perry on The Professor of Desire (1977)

I discovered the novels of Philip Roth as I have most literature during my 15 years in New York: on the subway. The experience of pouring over the sexual nuance of The Professor of Desire while surrounded by children and the elderly created a perplexing dichotomy between brown paper bag smut and totemic American fiction. This was both transformative and inspiring, illuminating for me the possibility of couching perversion, sexuality, anger and humour into a piece of work rightly perceived as serious and intellectual. Each transgressive element became less shocking as I made my way through Roth’s novels on F trains and Q trains, the feelings of shock replaced with the intended understanding of what these “amoral” acts said about the characters and the novels they inhabited.

I’m not sure if I would call The Professor of Desire my favorite of Roth’s novels (an honor I generally bestow upon Sabbath’s Theater, which I have learned seems to be the low key favourite of those in the know) but it was certainly the first to announce itself to me as massively influential. The Kepesh books introduced me to a view of improper, quasi-abusive relationships within academia that gave me the professor character in my film The Color Wheel.

When I began writing The Color Wheel in 2010, Roth was my north star. I intended to reverse engineer a narrative with the same youthful arrogance flaunting sexual taboos that excited, then inspired, me in his work. Depicting the story of an incestuous sibling relationship, but presenting it in the guise of a black and white independent art film, felt like a genuine way to honor the work of this titan; those books bound in the finest jacket design the twentieth century had to offer, elegantly concealing without so much as a hint the delightful perversions contained within.

Alex Ross Perry is an actor and filmmaker

Amy Rigby on The Ghost Writer

I refuse to accept the assertion that misogyny in Philip Roth’s novels makes it impossible for a woman to find herself in his characters. I want to – have a right to – identify with the great man or the schmuck.

I started reading The Ghost Writer looking for a road map to a stunning middle-career but found myself in a house of mirrors. The 46-year-old author looks back at himself as an accomplished beginner who visits an older giant of letters. Parents, wives, lovers – even Anne Frank – weigh in. It’s funny and moving and compact.

I picked it up again today, touched that anyone would ask for my thoughts on this genius whose work ethic and output made his greatness undeniable, whether you believe in him or not, and found this passage contained in Judge Wapter’s letter to young Nathan Zuckerman, who recounts it to us with such scorn and hope I couldn’t help but feel like a schmuck myself, or at least a poser: “I would like to think that if and when the day should dawn that you receive your invitation to Stockholm to accept a Nobel Prize, we will have had some small share in awakening your conscience to the responsibilities of your calling.’” You really were robbed, Phil.

Amy Rigby is a singer and songwriter. Her songs include From Philip Roth to R Zimmerman

Joyce Carol Oates on Roth’s legacy

Philip Roth was a slightly older contemporary of mine. We had come of age in more or less the same repressive 50s era in America – formalist, ironic, “Jamesian”, a time of literary indirection and understatement, above all impersonality – as the high priest TS Eliot had preached: “Poetry is an escape from personality.”

Boldly, brilliantly, at times furiously, and with an unsparing sense of the ridiculous, Philip repudiated all that. He did revere Kafka – but Lenny Bruce as well. (In fact, the essential Roth is just that anomaly: Kafka riotously interpreted by Bruce.) But there was much more to Philip than furious rebellion. For at heart he was a true moralist, fired to root out hypocrisy and mendacity in public life as well as private. Few saw The Plot Against America as actual prophecy, but here we are. He will abide.

Joyce Carol Oates is a novelist

0 notes

Text

'Savagely funny and bitingly honest' – 10 writers on their favourite Philip Roth novels

New Post has been published on https://funnythingshere.xyz/savagely-funny-and-bitingly-honest-10-writers-on-their-favourite-philip-roth-novels/

'Savagely funny and bitingly honest' – 10 writers on their favourite Philip Roth novels

Emma Brockes on Goodbye, Columbus (1959)

I fell in love with Neil Klugman, forerunner to Portnoy and hero of Goodbye, Columbus, Philip Roth’s first novel, in my early 20s – 40 years after the novel was written. Descriptions of Roth’s writing often err towards violence; he is savagely funny, bitingly honest, filled with rage and thwarted desire. But although his first novel rehearses all the themes he would spend 60 years mining – sexual vanity, lower-middle-class consciousness (“for an instant Brenda reminded me of the pug-nosed little bastards from Montclair”), the crushing weight of family and, of course, American Jewish identity – what I loved about his first novel was its tenderness.

Goodbye, Columbus is steeped in the nostalgia only available to a 26-year-old man writing of himself in his earlier 20s, a greater psychological leap perhaps than between decades as they pass in later life. Neil is smart, inadequate, needy, competitive. He longs for Brenda and fears her rejection, tempering his desire with pre-emptive attack. All the things one recognises and does.

My mother told me that the first time she read Portnoy’s Complaint she wept and, at the time, I couldn’t understand why. It’s not a sad novel. But, of course, as I got older I understood. One cries not because it is sad but because it is true, and no matter how funny he is, reading Roth always leaves one a little devastated.

I picked up Goodbye, Columbus this morning and went back to Aunt Gladys, one of the most put-upon women in fiction, who didn’t serve pepper in her household because she had heard it was not absorbed by the body, and – the perfect Rothian line, wry, affectionate, with a nod to the infinite – “it was disturbing to Aunt Gladys to think that anything she served might pass through a gullet, stomach and bowel just for the pleasure of the trip”. How we’ll miss him.

Emma Brockes is a novelist and Guardian columnist

James Schamus on Goodbye, Columbus (1959)