#its just granny squares on a black border

Text

i was looking thru boxes at my grandma’s and i found an afghan that i got in a care package from the JCC when i was 8 and in the hospital for a week. i assumed it got thrown out like most of my stuff after my parents died :( its so much smaller than i remember lol

#ill post a pic of it when its washed#its just granny squares on a black border#i loveddd it it was my favorite blanket from that point on#i remember that hospital visit very vividly#they brought me a care package with the blanket and art supplies and stickers and stuff to do while i was in bed#i also remember the tvs in the hospital only had VHS#and the only tapes they had were classic disney stuff#so i watched all dogs go to heaven and it scared the shit out of me#n they had a bunch of jerky boys tapes so i watched those

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quarantine Blanket #7: Corner-to-corner (3)

Aaand here we have it! The scrap c2c that was in my first two “WIP blankets” posts, in its final form!!! I could not get a good photo of the whole thing laid out flat on the floor, unfortunately, but I am really happy with how this turned out. It gave me a good way to use up a lot of scraps that are in colors I don’t use often (like the different teal variegateds, one with green and blue and brown and the other with cream and light green), plus browns and blues! And that giant stripe of bright green across the middle was another yarn I inherited when my boss cleaned out his props storage at work back in 2019, as was the kelly green I used between stripes of other colors, so it was great to finally get (some) of that out of my stash. What’s left of those two yarns is going into my scrap pile for my friend’s ripple blanket, as are the other browns and greens left over from this blanket! Since it was a lot of scraps, I’m not really sure what a lot of the yarn was, but here’s what I can remember off the top of my head:

Variegated brown/teal/green/blue/tan and cream/light green/teal are both Loops and Threads Impeccable

Royal blue, bright blue (near the bright green in the middle), and one of the tans are also Loops and Threads Impeccable

A lot of the tans/creams/browns were from a Bernat self-striping cake that my grandmother had in her stash for a while and passed on to me last summer. I had nothing else to do with it, so I wound each color into its own ball and threw them in with the scraps for this blanket.

Kelly green is a Caron One Pound (inherited from work) and bright purple is a Red Heart Super Saver... whatever their big skeins are called (inherited from my mom during my junior year of college, after she bought too much for a blanket for my brother). Cream is also a Caron One Pound.

Navy blue is Red Heart Super Saver (leftover from Quarantine Blanket #3!)

There are a few others in here, but I can’t remember what they are or where they came from!

I think my favorite part of this whole blanket, though, is the black fun fur border. It really pulls the whole thing together and I just think it looks so cool! When I did the white fur border on my second granny square blanket (the pink, blue, and purple granny square), I really loved it, even though I wasn’t thrilled with the blanket as a whole. Since I was already happy with the finished version of this blanket, the border just put it over the top and made it one of my favorite finished objects from the past year!!! The border is super simple—I held black fun fur (bought off Amazon) and some light-worsted black yarn (the Hobby Lobby version of Caron Simply Soft that I can’t think of the name of) and treble crocheted around the entire edge of the blanket. It took just over three skeins of the fun fur, and about 4/5 of the other yarn!

This yarn is a gift for a friend, and I can’t wait to be able to send it to them!!! I hope they love it as much as I do—and as much as Bunchy does!

#quarantine blanket#quarantine blankets#original#original post#c2c#c2c blanket#c2c crochet#crochet#blanket#afghan#stripes#scrap blanket#finished object

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Garden Variety, part i : other people’s patterns + group shots

[Image description: a mess of 14 crocheted flowers. Many of them are granny squares, but 2 are hexagons, 1 is a pentagon, and 1 is a septagon. Many use either a dark blue yarn or a green yarn with foil which sparkles faintly in the natural lighting. Descriptions of the individual flowers are included in their personal portraits in this post and the next. End image description.]

These flowers are presented as a uquiz, but all the pictures are divided between this post and the next post so there is space for additional pictures. I’ve done my best with photo descriptions, but some of them might be a little, ahem, flowery. Some of the uquiz descriptions will be included, others omitted.

African Flowers - blue and pink

[image description: Top image contains two “African flower” style crocheted hexagons. The one in the upper left is predominantly blue with brown border and center. In the lower right is a predominantly pink flower with a yellow center and white border. In the second picture is just the pink hexagonal flower with a yellow center and pink/purple/white petal edges. The border is white, and the flower rests on a black background which makes the colors more vibrant. End image description]

Pink uquiz description: “There are so many "African flower" patterns it's hard to say where I learned this one initially. Do you remember when Maude asks Harold what flower he would be, and he says "One of these, because they're all the same." But they're not all the same at all, and Maude points this out to him and shows him how some droop to the left or are missing petals, etc. The pink/purple/white yarn at the edges of your petals align with the white border in one place, bringing the border into your heart. Two petals clockwise (at 9 o’clock) from this is the spot you can tell the rows all started, because yellow cotton filaments break from one another and you can tell one of them is a row of chains rather than a true double crochet.”

“Crochet Bobble Drops Flower Granny Square” comes to us from crochetforyourblog.com and, will you look at that? it’s on some joker’s blog! (mine, i’m not making fun of the pattern maker, thank you for this lovely pattern)

[image description: First image: blue square. A dark blue flower with 16 bulging, teardrop shaped petals. Every 4th petal cuts up through a pale blue to the think dark blue border. It sits on a black background. Second image: a crocheted square with a blue border. The same blue yarn makes a 16-pointed flower. Every 4th point or petal reaches through a sparkly green space toward the border. An errant strand of foil sparkles on the blue flower. The square is sitting on a black background. End ID]

I made two because I really loved how the first (the top, all-blue) one turned out, and because it had a wintry vibe, I used a yarn bought from a Xmas display for a Yule mask last year.

Nick’s Series - original pattern

[image description: a small brown and blue speckled square held in a white hand. One corner is gently nudged forward at the top by my index finger. In the middle of the square is a blue flower with six petals. They cast a blue shadow on the flower's circular center. end ID]

Blue uquiz description: “I made you, and Nick said he liked you, which resulted in 3 more in rapid succession before I lost the impromptu pattern. It's since lost, but you remain. A hand-sized square intended initially as a way to explore pulling yarn through lower rows, or through the center over other layers, hiding them deep inside you, you would have made it difficult to be written, anyway. This one remains my favorite out of the four flowers in Nick's Series, and it is the only of the flowers photographed in my hand for this quiz.”

This is, in fact, the result the series’ namesake got when I had him test the quiz, so I think the quiz is rather accurate for that reason alone. In the quiz, you can also get the white flower, or Nick’s favorites (which we might call sherbet and purple to distinguish them) as options.

[image description: a green square arranged as a diamond on a black background. There is a white flower in the middle with 6 petals like squiggles. end description]

[image description: 2 squares matching in construction but not color. They're arranged vertically on a black background. The flowers have 6 petals each. The top has a purple/pink/white flower on a brown background with pale blue speckles. Its corners are more defined than the slightly rounder one below which has a green background and a blue/green/pink/orange/red flower.]

[image description: all 4 of the previous flowers arranged in a square on a black background with the blue and sherbet flowers on top and white and purple on the bottom. End ID.]

To be honest, they look best together where you can see that half are solid flowers, and half are speckled borders, and these halves overlap. If the pattern was to be duplicated, there had to be 4 in the end, not 2 or 3. What I loved about the first one of these was honestly how the back looks:

[image description: the backs of two crocheted squares: sherbet with its green border on the right and blue with its brown and blue border on the left. From behind, you can see that the sherbet or blue “flower” is a circle of tightly packed stitches surrounding a circular hole against the black background. End ID.]

Sherbet and Blue are my favorites, if you were wondering.

#crochet#uquiz#just for fun#squares#not all squares#you are only obligated to reblog the post with your quiz result flower

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another Logince post? On my blog??

It’s more likely than you’d think.

High school AU, Theater AU, Logince, 2038 words, no warnings

Roman smiled at his work, admiring his hand-made costume in the mirror. A simple white peasant shirt, a brown vest and matching jacket, a red scarf that he’d purposefully faded from its original ruby color, tan pants, brown shoes, and a newsboy hat. A chef’s hat and apron sat to the side for different scenes. Personally, he thought he’d done a pretty good job at making himself the baker.

He’d almost lost his mind when he heard that the school was doing Into The Woods for their Spring musical. There were so many parts that he wanted to play. Jack, the baker, either of the princes, the wolf, the narrator, the witch, Cinderella… He’d assumed that he would be assigned to play either Jack or Cinderella’s prince and the one senior boy they had would be the lead as the baker.

That changed when the senior moved away the week before auditions and Roman was awarded the lead.

Opening night was coming up fast. It always comes up faster than Roman likes. Sure, he loves the thrill of performing in front of an audience, but opening night also meant the beginning of the end for the production, the cast, the inside jokes, the after rehearsal trips to Cookout and Steak and Shake, the homework sessions in between scenes…

“Roman.” A head poked through the door of the dressing room. Patton still had on his headset on and a clipboard in hand. He’d always acted as the dad of the theater, even in his Freshman year when people said he didn’t know what he was doing, so stage manager was a natural role for him. He and Virgil have been holding up the tech end of the theater since their arrival, and it helped that everyone listened to them and did what they said.

“What’s up, Padre?”

“Joan needs you, there’s a problem.” Roman’s grin faded as he followed Patton from the dressing room.

Passing through a hallway of other actors adjusting their costumes and black-clad techies working on final touches for set pieces and props, Patton led Roman to the stage. Music flooded the auditorium as the pianist helped the witch run through her rap again, trying to help her not get tongue-tied. On the opposite side of the apron, the director was pinching the bridge of their nose, the chorus teacher running his hands through his faded purple hair in frustration.

“Joan, Thomas,” Roman called out to the teachers. Joan looked up from where they were pinching their nose, their dark eyes lighting up with hope when they saw Roman. Roman couldn’t remember when exactly he started calling his teachers by their first names, but they were close enough at that point that it wasn’t weird.

“Roman, thank God,” Joan sighed. “We’ve got a bit of a problem. Dexter’s gone.” Roman’s eyes blew wide and his jaw dropped. Dexter had been playing the roles of the narrator, the wolf, and the mysterious man. They were all minor roles, but Dexter was a good enough actor to pull them off. Now, Joan was just saying he’s gone?

“What do you mean ‘gone’? What happened?”

“He moved away, parents had to leave out of the blue, I don’t know the details, but now we’re out one actor and three characters and we have no idea who else can do it and we’re just a few weeks away from opening night-”

“Do you know anyone else who could fill in,” Thomas filled in Joan’s babbling with a more to-the-point question, resting a stabilizing hand on their shoulder to help them calm down. Roman opened his mouth to ask about the understudies, but remembered that there had only been enough actors that auditioned to fill out the cast. Covering his mouth with his hand, Roman thought on who could possibly fit. Faces of other people he’d seen in theater classes, techies trying their hand at acting or singing.

The piano music stopped for an instant for the pianist to tell the actress playing the witch something, and memories flashed through Roman’s mind.

“LOGAN!” Roman just about tripped over himself running off the stage to the piano. Logan jumped out of his skin at the shout of his name, going stiff and wide-eyed as Roman halfway fell against the piano, grabbing Logan by the elbow and pulling him up onto the stage.

“Roman, what’re you-”

“Logan can do it! He can take Dexter’s place!”

“What?” Roman smiled at Logan, trying to reassure him only to find his onyx eyes swimming with the kind of uncertainty that bordered on terror. Joan and Thomas looked Logan over.

“Are you sure,” Joan asked, raising an eyebrow at Roman.

“Yeah, I mean,” Thomas tilted his head to the side, “no offense, Logan, you’re great in choir, but I don’t know if-”

“Believe me, he’s good.” Roman could barely contain his excitement. He’d caught Logan helping actors with all sorts of roles over the years, running lines with them and getting into the part with everything he had. He was a good actor, Roman knew it. “Just give him a test run, I promise he won’t disappoint.”

“Roman, I really think you need to stop,” Logan straightened his glasses, trying desperately to remain collected. “Besides, if by some stretch of the imagination I do end up taking Dexter’s place, who will do the accompaniment?”

“We can find another, there are plenty of accompanists who’ll take the job, and if all else fails we use the recording. You’ve been pushing us to its speed, anyway, so it shouldn’t be too big a deal. Please, just,” Roman’s head whipped back and forth between Logan and Thomas and Joan, “just give him a shot, I know you can do this, please just give it a try.” Thomas and Joan gave each other a look, exchanging a silent conversation, and Roman felt every muscle in Logan’s body tense. Thomas shrugged, and Joan sighed.

“Roman,” they decided, “you’re Little Red. Logan, you’re the wolf. Run through Hello, Little Girl from the top of the scene. Logan, do you need a script?” Roman started bouncing as Logan just barely shook his head. He looked almost catatonic, like Roman could barely push him with one finger and he’d fall straight back. Thomas and Joan made their way out into the audience to watch.

Pulling at his hair and pacing away, Logan seemed extremely distressed. Roman could almost feel him shaking as he moved to the opposite side of the stage. He might have felt guilty if he didn’t already know that Logan would be great.

“From the top,” Joan ordered. “Whenever you’re ready.” Logan took a deep breath at the direction, turning to meet eyes with Roman, nodding. Understanding the cue, Roman started skipping. It was a matter of seconds before Logan slid in front of him.

“Good day, young lady,” Logan purred at Roman, a sly smirk appearing from what seemed like nowhere.

“Good day, Mr. Wolf,” Roman replied cheerfully, keeping himself in character as best he could. He tried to skip away, but Logan blocked his path again. Perfect.

“Whither away so hurriedly?” Roman continued with his lines, but in his head he couldn’t help but wonder at how Logan was doing so far. He’d seen him act, but never as something like the wolf. He’d lowered his voice to a growl that somehow still projected, and smoothed into something akin to molasses.

Their speaking lines finished, and Roman started skipping in place, glancing upstage every now and then to watch Logan as he started singing. Roman already knew that Logan had a wide range, going from the low baritone to mid alto when he stretched himself, but other than his baritone role in choir, he tended to keep his speaking voice in the tenor range. His voice singing the part rumbled through Roman’s chest like thunder on the darker part, smoothing out when the mood changed when he started smiling and singing to Roman about the flowers.

“Mother said,” Roman sang his part right on cue, “straight ahead, not to delay or be mislead.”

“But slow little girl,” Roman yelped in the middle of Logan’s line, not expecting him to grab his wrist and pull him into a low dip. “Hark and hush. The birds are singing sweetly.” Roman tried desperately to ignore the pounding of his heart as Logan purred down at him. “You’ll miss the birds completely. You’re travelling so fleetly.” On the last word, Logan picked Roman up and twirled him away.

Landing just outside the stage right curtain, Roman tried to stay in character, but couldn’t help but watch as Logan hunched his shoulders, rolling them like he was an animal on the prowl as he sang the darker part of the song. Roman hadn’t expected Logan to get the dark creepiness of the role down so easily, and was admittedly impressed.

“Mother said, come what may,” Roman just barely snapped himself out of his trance, “follow the path and never stray.”

“Just so, little girl,” Logan grabbed his hand, bending at his waist like he was going to kiss Roman’s knuckles only to pull Roman along, maintaining an eye contact that Roman knew was making him flush, “any path. So many worth exploring.” Roman snatched his hand back, trying to move away, but Logan pursued. “Just one would be so boring,” he gripped Roman around his shoulders, pulling him close and motioning at the ground, “and look what you’re ignoring!”

Again, Roman tried to remain in character as he bent down to pick the imaginary flowers, but his mind and eyes were distracted by Logan’s incredible crescendo. Straightening out and looking at Logan’s falsely innocent smirk, Roman almost forgot to say his line.

“Mother said not to stray,” Roman’s voice was a bit too soft, but he perked himself up quickly, “still I suppose a small delay… Granny might like a fresh bouquet! Goodbye, Mr. Wolf!”

“Goodbye, little girl,” Logan called after Roman as he exited, “and hello…” Logan’s final howl echoed through the theater as he threw his head back, arching his back to puff out his chest. He ended the howl by turning to smirk maliciously at Roman offstage, a slight growl on his lips.

It was mere seconds before Logan straightened himself out, squaring his shoulders and straightening his glasses as he moved toward the steps that led from the stage to the house. He froze when applause erupted from the wings, the entire cast having heard him and gathered to watch. Virgil whistled from up in the light booth. Joan and Thomas applauded from the audience, making their way from the center of the house to the apron of the stage. Roman just about bounced from the wings, his applause only ending when he threw his arms around Logan.

“See,” Roman exclaimed to Joan and Thomas. “Didn’t I tell you! He’s fantastic!”

“You looked just as shocked as us, Roman,” Joan chuckled.

“Well, yeah, I’ve never seen him do something like that, but didn’t I tell you he’s great?” Roman kept one arm around Logan’s tense shoulders. The pianist felt like he was going to spontaneously combust.

“Logan,” Thomas looked like he was about to cry, “I knew you had a powerful voice, but you never told me it was that powerful!”

“Why didn’t you audition in the first place? Dexter would’ve been an understudy, you might’ve had one of the larger parts.” Joan’s question sent Logan into a fit of sputtering like a car refusing to start.

“I- I don’t… I- I don’t- I just don’t-”

“Never mind,” Joan raised a hand, “will you please do this for us?” Logan took a deep breath, swallowing hard in an attempt to force himself to speak properly.

“If I am truly your only option, and you truly want me to do this, then I will do as you ask.” Thomas started clapping again, giggling to himself in excitement. Joan mentioned something about “can’t wait to hear you two do No More.” Logan could barely hear for the muffled state of his ears and heavy heat in his head as Roman threw his arms around him again. Logan felt as though he’d just signed his soul away.

Roman felt as though he’d just won the lottery.

#logince#logince au#thomas sanders#logan sanders#roman sanders#patton sanders#virgil sanders#high school au#thatsthat24#logan#roman#patton#virgil#fanfic#might continue with this#not sure#probably though since i've already got more

155 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arplis - News: I had known him almost all my life, Beniek

He lived around the corner from us, in our neighborhood in Wrocław, composed of rounded streets and three-story apartment buildings that from the air formed a giant eagle, the symbol of our nation. There were hedges and wide courtyards with a little garden for each flat, and cool, damp cellars and dusty attics. It hadn’t even been twenty years since any of our families had come to live there. Our postboxes still said ‘Briefe’ in German. Everyone – the people who’d lived here before and the people who replaced them – had been forced to leave their home. From one day to the next, the continent’s borders had shifted, redrawn like the chalk lines of the hopscotch we played on the pavement. At the end of the war, the east of Germany became Poland and the east of Poland became the Soviet Union. Granny’s family were forced to leave their land. The Soviets took their house and hauled them on the same cattle trains that had brought the Jews to the camps a year or two earlier. They ended up in Wrocław, a city inhabited by the Germans for hundreds of years, in a flat only just deserted by some family we’d never know, their dishes still in the sink, their breadcrumbs on the table. This is where I grew up.

It was on the wide pavements, lined with trees and benches, where all the children of the neighborhood played together. We would play catch and skip ropes with the girls, and run around the courtyards, screaming, jumping on to the double bars that looked like rugby posts and on which the women would hang and beat their carpets. We’d get told off by adults and run away. We were dusty children. We’d race through the streets in summer in our shorts and knee-high socks and suspenders, and in flimsy wool coats when the ground was covered in leaves in autumn, and we’d continue running after frost invaded the ground and the air scratched our lungs and our breath turned to clouds before our eyes. In spring, on Śmigus-Dyngus day, we’d throw bucketloads of water over any girl who wasn’t quick enough to escape, and then we’d chase and soak each other, returning home drenched to the bone. On Sundays, we’d throw pebbles at the milk bottles standing on the windowsills higher up where no one could steal them, and we’d run away in genuine fear when a bottle broke and the milk ran slowly down the building, white streams trickling down the sooty facade like tears.

Everyone – the people who’d lived here before and the people who replaced them – had been forced to leave their home.

Beniek was part of that band of kids, part of the bolder ones. I don’t think we ever talked back then, but I was aware of him. He was taller than most of us, and somehow darker, with long eyelashes and a rebellious stare. And he was kind. Once, when we were running from an adult after some mischief now long forgotten, I stumbled and fell on to the sharp gravel. The others overtook me, dust gathering, and I tried to stand. My knee was bleeding.

“You alright?”

Beniek was standing over me with his hand outstretched. I reached for it and felt the strength of his body raise me to my feet.

“Thank you,” I murmured, and he smiled encouragingly before running off. I followed him as fast as I could, happy, forgetting the pain in my knee.

Later, Beniek went off to a different school, and I stopped seeing him. But we met again for our First Communion.

The community’s church was a short walk from our street, beyond the little park where we never played because of the drunkards, and beyond the graveyard where Mother would be buried years later. We’d go every Sunday, to church. Granny said there were families that only went for the holidays, or never, and I was jealous of the children who didn’t have to go as often as me.

When the lessons for the First Communion started, we’d all meet twice a week in the crypt. The classes were run by Father Klaszewski, a priest who was small and old but quick, and whose blue eyes had almost lost their color. He was patient, most of the time, resting his hands on his black robe while he spoke, one holding the other, and taking us in with his small, washed-out eyes. But sometimes, at some minor stupidity, like when we chatted or made faces at each other, he would explode, and grab one of us by the ear, seemingly at random, his warm thumb and index finger tightly around the lobe, tearing, until we saw black and stars. This rarely happened for the worst behavior. It was like an arbitrary weapon, scarier for its randomness and unpredictability, like the wrath of some unreasonable god.

This is where I saw Beniek again. I was surprised that he was there, because I had never seen him at church. He had changed. The skinny child I remembered was turning into a man – or so I thought – and even though we were only nine you could already see manhood budding within him: a strong neck with a place made out for his Adam’s apple; long, strong legs that would stick out of his shorts as we sat in a circle in the priest’s room; muscles visible beneath the skin; fine hair appearing above his knees. He still had the same unruly hair, curly and black; and the same eyes, dark and softly mischievous. I think we both recognized the other, though we didn’t acknowledge it. But after the first couple of meetings we started to talk. I don’t remember what about. How does one bond with another child, as a child? Maybe it’s simply through common interests. Or maybe it’s something that lies deeper, for which everything you say and do is an unwitting code. But the point is, we did get on. Naturally. And after Bible study, which was on Tuesday or Thursday afternoons, we’d take the tram all the way to the city centre, riding past the zoo and its neon lion perched on top of the entrance gate, past the domed Centennial Hall the Germans had built to mark the anniversary of something no one cared to remember. We rode across the iron bridges over the calm, brown Oder river. There were many empty lots along the way, the city like a mouth with missing teeth. Some blocks only had one lonely, sooty building standing there all by itself, like a dirty island in a black sea.

We didn’t tell anyone about our escapes – our parents would not have allowed it. Mother would have worried: about the red-faced veterans who sold trinkets in the market square with their cut-off limbs exposed, about ‘perverts’ – the word falling from her lips like a two-limbed snake, dangerous and exciting. So we’d sneak away without a word and imagine we were pirates riding through the city on our own. I felt both free and protected in his company. We’d go to the kiosks and run our fingers over the large smooth pages of the expensive magazines, pointing out things we could hardly comprehend – Asian monks, African tribesmen, cliff divers from Mexico – and marveling at the sheer immensity of the world and the colors that glowed just underneath the black and white of the pages.

This is where I saw Beniek again. I was surprised that he was there, because I had never seen him at church. He had changed.

We started meeting on other days too, after school. Mostly we went to my flat. We’d play cards on the floor of my tiny room, the width of a radiator, while Mother was out working, and Granny came to bring us milk and bread sprinkled with sugar. We only went to his place once. The staircase of the building was the same as ours, damp and dark, but somehow it seemed colder and dirtier. Inside, the flat was different – there were more books, and no crosses anywhere. We sat in Beniek’s room, the same size as mine, and listened to records that he’d been sent by relatives from abroad. It was there that I heard the Beatles for the first time, singing “Help!” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand”, instantly hurling me into a world I loved. His father sat on the couch in the living room reading a book, his white shirt the brightest thing I’d ever seen. He was quiet and soft-spoken, and I envied Beniek. I envied him because I had never had a real father, because mine had left when I was still a child and hadn’t cared to see me much since. His mother I remember only vaguely. She made us grilled fish and we sat together at the table in the kitchen, the fish salty and dry, its bones pinching the insides of my cheeks. She had black hair too, and although her eyes were the same as Beniek’s, they looked strangely absent when she smiled. Even then, I found it odd that I, a child, should feel pity for an adult.

One evening, when my mother came home from work, I asked her if Beniek could come and live with us. I wanted him to be like my brother, to be around me always. My mother took off her long coat and hung it on the hook by the door. I could tell from her face that she wasn’t in a good mood.

“You know, Beniek is different from us,” she said with a sneer. “He couldn’t really be part of the family.”

“What do you mean?” I asked, puzzled. Granny appeared by the kitchen door, holding a rag.

“Drop it, Gosia. Beniek is a good boy, and he is going to Communion. Now come, both of you, the food is getting cold.”

*

One Saturday afternoon, Beniek and I were playing catch on the strip outside our building with some other children from the neighborhood. I remember it was a warm and humid day, with the sun only peeking through the clouds. We played and ran, driven by the rising heat in the air, feeling protected under the roof of the chestnut trees. We were so caught up in our game that we hardly noticed the sky growing dark and the rain beginning to fall. The pavement turned black with moisture, and we enjoyed the wetness after a scorching day, our hair glued to our faces like seaweed. I remember Beniek vividly like this, running, aware of nothing but the game, joyous, utterly free. When we were exhausted and the rain had soaked through our clothes, we hurried back to my apartment. Granny was at the window, calling us home, exclaiming that we’d catch a cold. Inside, she led us to the bathroom and made us strip off all our clothes and dry ourselves. I was aware of wanting to see Beniek naked, surprised by the swiftness of this wish, and my heart leapt when he undressed. His body was solid and full of mysteries, white and flat and strong, like a man’s (or so I thought). His nipples were larger and darker than mine; his penis was bigger, longer. But most confusingly, it was naked at the tip, like the acorns we played with in autumn. I had never really seen anyone else’s, and wondered whether there was something wrong with mine, whether this is what Mother had meant when she’d said Beniek was different. Either way, this difference excited me. After we had rubbed ourselves dry, Granny wrapped us in large blankets and it felt like we had returned from a journey to a wondrous land. “Come to the kitchen!” she called with atypical joy. We sat at the table and had hot black tea and waffles. I cannot remember anything ever tasting so good. I was intoxicated, something tingling inside me like soft pain.

Our Communion excursion arrived. We went up north, towards Sopot. It was the sort of early summer that erases any memory of other seasons, one where light and warmth clasp and feed you to the absolute. We drove by bus, forty children or so, to a cordoned-off leisure centre near a forest, beyond which lay the sea. I shared a room with Beniek and two other boys, sleeping on bunk beds, me on top of him. We went on walks and sang and prayed. We played Bible games, organized by Father Klaszewski. We visited an old wooden chapel in the forest, hidden between groves of pine trees, and prayed with rosaries like an army of obedient angels.

In the afternoons we were free. Beniek and I and some other boys would go to the beach and swim in the cold and turbulent Baltic. Afterwards, he and I would dry off and leave the others. We’d climb the dunes of the beach and wade through its lunar landscape until we found a perfect crest: high and hidden like the crater of a dormant volcano. There we’d curl up like tired storks after a sea crossing and fall asleep with the kind summer wind on our backs.

On the last night of our stay, the supervisors organized a dance for us, a celebration of our upcoming ceremony. The centre’s canteen was turned into a sort of disco. There was sugary fruit kompot and salt sticks and music played from a radio. At first we were all shy, feeling pushed into adulthood. Boys stood on one side of the room in shorts and knee-high socks, and girls on the other with their skirts and white blouses. After one boy was asked to dance with his sister, we all started to move on to the dance floor, some in couples, others in groups, swaying and jumping, excited by the drink and the music and the realization that all this was really for us.

Beniek and I were dancing in a loose group with the boys from our room when, without warning, the lights went off. Night had already fallen outside and now it rushed into the room. The girls shrieked and the music continued. I felt elated, suddenly high on the possibilities of the dark, and some unknown barrier receded in my mind. I could see Beniek’s outline near me, and the need to kiss him crept out of the night like a wolf. It was the first time I had consciously wanted to pull anyone towards me. The desire reached me like a distinct message from deep within, a place I had never sensed before but recognized immediately. I moved towards him in a trance. His body showed no resistance when I pulled it against mine and embraced him, feeling the hardness of his bones, my face against his, and the warmth of his breath. This is when the lights turned back on. We looked at each other with eyes full of fright, aware of the people standing around us, looking at us. We pulled apart. And though we continued to dance, I no longer heard the music. I was transported into a vision of my life that made me so dizzy my head began to spin. Shame, heavy and alive, had materialized, built from buried fears and desires.

That evening, I lay in the dark in my bed, above Beniek, and tried to examine this shame. It was like a newly grown organ, monstrous and pulsating and suddenly part of me. It didn’t cross my mind that Beniek might be thinking the same. I would have found it impossible to believe that anyone else could be in my position. Over and over I replayed that moment in my head, watched myself pull him in to me, my head turning on the pillow, wishing it away. It was almost dawn when sleep finally relieved me.

The next morning we stripped the sheets off our beds and packed our things. The boys were excited, talking about the disco, about the prettiest girls, about home and real food.

“I can’t wait for a four-egg omelette,” said one pudgy boy.

Someone else made a face at him. “You voracious hedgehog!”

Everyone laughed, including Beniek, his mouth wide open, all his teeth showing. I could see right in to his tonsils, dangling at the back of his throat, moving with the rhythm of his laughter. And despite the sweeping wave of communal cheer, I couldn’t join in. It was as if there were a wall separating me from the other boys, one I hadn’t seen before but which was now clear and irreversible. Beniek tried to catch my eye and I turned away in shame. When we arrived in Wrocław and our parents picked us up, I felt like I was returning as a different, putrid person, and could never go back to who I had been before.

We had no more Bible class the following week, and Mother and Granny finished sewing my white gown for the ceremony. Soon, they started cooking and preparing for our relatives to visit. There was excitement in the house, and I shared none of it. Beniek was a reminder that I had unleashed something terrible into the world, something precious and dangerous. Yet I still wanted to see him. I couldn’t bring myself to go to his house, but I listened for a knock on the door, hoping he would come. He didn’t. Instead, the day of the Communion arrived. I could hardly sleep the night before, knowing that I would see him again. In the morning, I got up and washed my face with cold water. It was a sunny day in that one week of summer when fluffy white balls of seeds fly through the streets and cover the pavements, and the morning light is brilliant, almost blinding. I pulled on the white high-collared robe, which reached all the way to my ankles. It was hard to move in. I had to hold myself evenly and seriously like a monk. We got to the church early and I stood on the steps overlooking the street. Families hurried past me, girls in their white lace robes and with flower wreaths on their heads. Father Klaszewski was there, in a long robe with red sleeves and gold threads, talking to excited parents. Everyone was there, except for Beniek. I stood and looked for him in the crowd. The church bells started to ring, announcing the beginning of the ceremony, and my stomach felt hollow.

“Come in, dear,” said Granny, taking me by the shoulder. “It’s about to begin.”

“But Beniek–”

“He must be inside,” she said, her voice grave. I knew she was lying. She dragged me by the hand and I let her.

The church was cool and the organ started playing as Granny led me to Halina, a stolid girl with lacy gloves and thick braids, and we moved down the aisle hand in hand, a procession of couples, little boys and little girls in pairs, dressed all in white. Father Klaszewski stood at the front and spoke of our souls, our innocence and the beginning of a journey with God. The thick, heavy incense made my head turn. From the corner of my eye I saw the benches filled with families and spotted Granny and her sisters and Mother, looking at me with tense pride. Halina’s hand was hot and sweaty in mine, like a little animal. And still, no Beniek. Father Klaszewski opened the tabernacle and took out a silver bowl filled with wafers. The music became like thunder, the organ loud and plaintive, and one by one boy and girl stepped up to him and he placed the wafer into our mouths, on our tongues, and one by one we got on our knees in front of him, then walked off and out of the church. The queue ahead of me diminished and diminished, and soon it was my turn. I knelt on the red carpet. His old fingers set the flake on to my tongue, dry meeting wet. I stood and walked out into the blinding sunlight, confused and afraid, swallowing the bitter mixture in my mouth.

The next day I went to Beniek’s house and knocked on his door with a trembling hand, my palms sweating beyond my control. A moment later I heard steps on the other side, then the door opened, revealing a woman I had never seen before.

“What?” she said roughly. She was large and her face was like grey creased paper. A cigarette dangled from her mouth.

I was taken aback, and asked, my voice aware of its own futility, whether Beniek was there. She took the cigarette out of her mouth.

“Can’t you see the name on the door?” She tapped on the little square by the doorbell. “Kowalski”, it said in capital letters. “Those Jews don’t live here any more. Understood?” It sounded as if she were telling off a dog. “Now don’t ever bother us again, or else my husband will give you a beating you won’t forget.” She shut the door in my face.

I stood there, dumbfounded. Then I ran up and down the stairs, looking for the Eisenszteins on the neighboring doors, ringing the other bells, wondering whether I was in the wrong building.

“They left,” whispered a voice through a half-opened door. It was a lady I knew from church.

“Where to?” I asked, my despair suspended for an instant.

She looked around the landing as if to see whether someone was listening. “Israel.” The word was a whisper and meant nothing to me, though its ominous rolled sound was still unsettling.

“When are they coming back?”

Her hands were wrapped around the door, and she shook her head slowly. “You better find someone else to play with, little one.” She nodded and closed the door.

I stood in the silent stairwell and felt terror travel from my navel, tying my throat, pinching my eyes. Tears started to slide down my cheeks like melted butter. For a long time I felt nothing but their heat.

Did you ever have someone like that, someone that you loved in vain when you were younger? Did you ever feel something like my shame? I always assumed that you must have, that you can’t possibly have gone through life as carelessly as you made out. But then I begin to think that not everyone suffers in the same way; that not everyone, in fact, suffers. Not from the same things, at any rate. And in a way this is what made us possible, you and me.

__________________________________

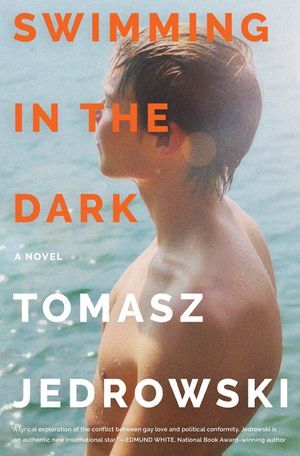

From Swimming in the Dark by Tomasz Jedrowski. Copyright © 2020 by Tomasz Jedrowski.Reprinted with permission of the publisher, William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

#FromTheNovel #WilliamMorrow #SwimmingInTheDark #FictionAndPoetry #Novel

Arplis - News

source https://arplis.com/blogs/news/i-had-known-him-almost-all-my-life-beniek

0 notes

Text

My Heart’s in the Highlands - Chapter 16

Fandom: OUAT, Hamish Macbeth

Pairing: Bellish, Swanfire, Snowing

Rating: T

Summary: With Rumplestiltskin gone, Belle can't face going back to the Enchanted Forest without him. She leaves Storybrooke forever, travels the world, and ends up in a small village in Scotland, where she meets a constable with a very familiar face.

AO3

Chapter 16 - A Small Thing - Hamish gets his first taste of Storybrooke.

“Belle? Belle! Belle!”

Walking away from the town line with Hamish’s shouts ringing in her ears was the most difficult thing she had ever had to do. Tears coursed down her face as she heard him run, heard him shout, heard him roar with rage. There was nothing to do but keep walking forward, she knew, for she could not make him believe, and without belief he could never enter Storybrooke. Fighting the urge to look back, Belle clutched her pack with trembling fingers. She hoped that he would go to the hotel, that he would wait for her and not go immediately back to Scotland where women didn’t disappear into thin air.

“Belle, wait! Wait!”

His voice sounded closer and clearer, and she froze, her heart pounding, and then turned, hardly able to believe her senses. Hamish stood just over the town line, his eyes wide and his face pale. The sound of her breath was loud in her ears and slowly she raised one hand. His fingers visibly trembling, he waved back. Belle dropped her pack and ran, her eyes fixed on his face, until she could throw herself into his arms. He clutched her in return, squeezing her until she could scarcely breathe, and she knew she was holding him just as tightly.

“There, darlin’,” he murmured. “It’s alright, love, I’m here.”

“How?” she gasped. “How?”

“Well...I guess I decided tae trust you,” he whispered back. “And believe you.”

She nearly laughed with relief as she pulled away. “I thought...I was so afraid you would leave.”

“Never,” he said solemnly, brushing a lock of hair out of her face.

Belle sighed and hugged him again, more gently this time, and then stepped back. “We can take the car now, thank goodness.”

Hamish laughed shakily, “Aye, that we can.”

They collected their packs and turned to walk back to the car. When they were nearly at the line, a gruff voice shouted into the night.

“Halt!” They froze and turned toward the voice. A short, stout figure stomped out from the shadows of the trees and raised its arm. “Who are you?” the voice demanded. There was a click, and a flashlight’s beam shone directly into their faces. “What are you doing out...Belle?”

Belle felt Hamish’s arm wrap around her protectively. She squinted into the light, trying to make out the face of their questioner.

“Gods, what are you...how did you…”

“Who are you?” Belle asked. “I can’t see anything.”

“Oh, right, sorry.” The flashlight dropped from her face and she blinked rapidly, the man’s face coming into focus. She grinned when she saw the thick black beard and dark scowling eyes.

“Dreamy!” She pulled away from Hamish and hugged her friend, warmth rushing through her when he returned the gesture with one arm.

“It’s Grumpy now, remember?” he groused. “That or Leroy. Where the hell have you been, sister?”

“Everywhere, more or less,” she said. “What are you doing out here?”

“Patrolling, obviously. What else would Snow White’s royal guard do?”

“Of course, I’m sorry. Does that mean the others are nearby?”

“I always get stuck with Sleepy,” Leroy grumbled, “and he can never last a full shift, so I just prop him up next to a tree and go it alone. Doc and Sneezy are at the west border of town, Happy and Bashful are up north, and Tiny and Dopey watch over the docks.”

“So you’re all okay. You’re all here?”

“So far.” Leroy looked grim. “Things’ve been…” He looked over her shoulder and noticed Hamish for the first time. “Seven hells,” he whispered. He raised his axe and Hamish took a hasty step back, his hands up. “How did you...you really are a demon, aren’t you?”

“Leroy, no,” Belle said, stepping quickly in front of him. “It’s not him. I know what it looks like, really I do, but it’s not him. Rumple is gone.”

“Then who is this guy? I don’t like his face.”

Hamish looked outraged, and Belle almost laughed. “This is Hamish Macbeth.”

Leroy snorted. “Nice name.”

“Same tae you, Grumpy,” Hamish retorted.

“Boys, stop,” Belle said. “Leroy, where is Emma staying? I need to see her.”

“She’s at Snow’s place.” Leroy continued to eye Hamish with mistrust. “I don’t think he should go with you.”

“Hamish is my friend,” Belle said firmly. “He came here with me, and I’m not going to let you bully him.” There was a squawk of protest from beside her, but Belle ignored him. “I’ll vouch for him.”

Leroy glared at Hamish for a few more seconds and then lowered his axe. “Fine,” he grunted. “No funny business though.” He shouldered his axe and nodded at Belle. “It’s great to have ya back, sister. See ya around.” As he sauntered back into the woods, he began to whistle, and Belle smiled when she recognized the tune.

“Is he...is he whistling ‘Heigh-Ho’?” Hamish asked faintly.

“Yep.”

“So that was…”

“Grumpy. Head of Snow White’s guard and unofficial town crier.”

“Right. Okay. Of course.” Hamish looked very pale. “Let’s just...go, eh?”

They had been driving in the dark for a few moments when he spoke up again.

“Tiny?”

“What?”

“I thought there were only seven dwarfs, and I’ve never heard of one named Tiny. Who’s Tiny?”

“He’s a giant. I mean...he was a giant. Or...I guess he’s technically still a giant, he’s just not giant-sized anymore. He’s the last of his kind - the dwarfs sort of adopted him as their eighth brother.”

“Ah.”

Belle smiled and let him process that information in silence. As they drove down the main street, Hamish visibly relaxed. Belle supposed that the unassuming New England buildings and quiet dark streets grounded him, and when she parked on a curb near Granny’s Bed and Breakfast he looked almost calm.

“Not so bad, is it?” she teased.

“Reminds me of Lochdubh,” he said.

As they approached the building in which the royals lived and climbed the stairs to Snow White’s loft, Belle stood a little straighter, her head held high and her shoulders squared. She’d always felt a little defensive around Snow White and Prince David; their distaste for Rumplestiltskin had led to more than one uncomfortable encounter, and she highly doubted they would be thrilled to see her returned. She reminded herself that she didn’t care what they thought. She was here to help Emma and Neal.

Her hand trembling just a little, she knocked on the door.

Hamish had been trying his level best not to look as out of his depth as he felt. Encountering one of the seven dwarfs immediately after being admitted into a secret magical town was a shock that would rattle anyone, he knew, but Belle looked nervous enough without having to worry about his state of mind. She knocked firmly on the door and stood with ramrod-straight posture as she waited, and he had a sudden flash of realization: in that moment, she was every inch a noblewoman. A fairytale princess who had walked right out of childhood stories and into his life.

No wonder she’d always seemed out of his league.

The door swung open and Hamish felt as if the breath had been knocked out of him. With her milky white complexion, sleek black hair, and flawless elfin features, there was no way the woman in front of him could be anyone but Snow White.

The fairest of them all, the stories said.

Not quite, as far as Hamish was concerned. She was beautiful, but no one could hold a candle to Belle. Snow White’s eyes widened and he saw a flicker of fear cross her face before she focused on Belle. “Belle,” she breathed. “You came.”

“Of course I came,” Belle said. “Is Emma here?”

“Yes. I’m sorry, please come in.” Her eyes swept over Hamish once more as he followed Belle into the tiny studio apartment. “You must be Hamish. Emma mentioned you.”

Belle turned to face the princess and her jaw dropped. “You’re…”

“Pregnant,” Snow White beamed, placing one hand on her stomach. “I know. It was the strangest thing - one minute we were standing at the town line watching you all drive away, and the next I was back in this apartment and very pregnant.”

“And you don’t remember anything?” Belle asked. “You’ve been gone more than two years.”

“No. Mother Superior is trying to find a way to restore our memories, but if it has anything to do with the Dark Curse she might not be able to…”

“Belle? What the hell are you doing here?” Another stunning woman - this one blonde and fierce-looking, appeared on the stairs. “I told you…”

“I know, Emma, but...I couldn’t stay in Lochdubh, and I want to help.”

Emma pursed her lips and nodded. “Hey, Hamish,” she said tightly. “Neal told me about you. You’re gonna get a lot of weird looks around here, so be warned.”

“We met Leroy on the way in,” Belle said.

“I was lucky to get away with my head still on my shoulders,” Hamish groused.

Emma folded her arms and smirked. “He’s pretty protective. Of Mom at least.”

Mom.

“Besides being Neal’s girlfriend, Emma is the daughter of Snow White and Prince David,” Belle informed him helpfully.

But she was…

Right. Magic. He had to remember that.

“My kid has a storybook that can explain everything,” Emma said, her voice softening. “You should talk to him in the morning.”

“For now, tell us what you know.” Hamish folded his arms. “Is anyone missing besides Neal and...who else was it?”

“Regina,” Snow White said. She gestured at the kitchen table and sank into a chair, her hands folded protectively over her belly. “She’s my stepmother and Henry’s adopted mother.”

“You would know her better as the evil queen,” Belle said. “She’s not really evil anymore, but...are you sure the Curse wasn’t her doing?”

“We can’t be sure of anything, obviously,” Emma said. She sat next to her mother and Hamish noticed that they had the same rounded, dimpled chin. “But she hasn’t tried to contact Henry, and that makes no sense at all. It’s not like her.”

“As far as whether anyone else is missing, we can’t be sure of that either.”

“Has there been a roll call of any kind? A census?” Hamish felt a muscle ticking in his jaw at the princess’s wide-eyed, confused silence. “A show of hands, even?”

“I...no, we…”

“Well, that’s our first step, then,” he said. “First thing tomorrow. Do you have a police force here?”

“I’m it,” Emma said. “Besides my dad, of course. He’s on the night shift.”

“You’ve got your guard, your - your majesty,” he said to Snow White, stumbling a little over the words. “Can we utilize them?”

“Yes, they’d be glad to help.” She sat up a little straighter and looked thoughtful. “The fairies, too. Blue knows nearly everyone in the Enchanted Forest.”

“Do you have a map of the city somewhere? We’ll divide it into sections and send pairs of census takers to each section, every house. Make a record of the names of all individuals, ask if they’re missing anyone. They’ll report back and we’ll make a masterlist, and we can move on from there.” All three women were staring at him and he raised his eyebrows. “What?”

“Anything else?” Belle asked.

“Tell them to keep an eye out for anyone they don’t recognize. Whoever did this is still in the area. You don’t remember the last few years...maybe there’s a reason for that. This person doesn’t want you to recognize them.”

“Okay. Good plan,” Emma sighed and rubbed at her forehead. “I didn’t want you to come here and put yourself in danger, Belle, but I’m glad you did. Are you gonna stay at Granny’s? We can meet at the station first thing in the morning.”

Belle nodded, then stepped forward slowly. Carefully she wrapped her arms around Emma’s shoulders, and Hamish hid a smile at the other woman’s stunned expression.

“We’ll find them, Emma. I swear it.”

“Thank you,” Emma whispered, her eyes closing briefly. She looked at Hamish. “You, too. I’ll have Henry meet with you tomorrow.”

Hamish nodded, looking back once over his shoulder as they left the loft. Two pairs of green eyes watched him speculatively as he followed Belle, and a shiver ran up his spine. This was easily the strangest thing ever to happen to him.

“That was…” Belle sighed and took his hand when they were out of the apartment building. “You are a really good police officer, did you know that?”

“Aye.” Hamish grinned down at her. “Glad I came along, now, eh?”

Chuckling, Belle leaned her head against his shoulder and led him back to the large, rambling inn they’d parked in front of. The bell above the door jingled merrily and there was a clatter of footsteps on the stairs; the next instant a tall dark-haired woman had tackled Belle in a fierce hug.

“Snow called and said you were back,” the woman squealed. “I can’t believe it!” She pulled back, her large dark eyes sparkling with tears.

“It’s good to see you, Ruby,” Belle smiled, squeezing the woman’s hands. “This is Hamish.”

The woman nodded at him, not a trace of fear or suspicion in her eyes. “Hey, I’m Ruby. Or Red. Either works for me.”

Hamish eyed the red streak in her hair and she smiled, stroking one hand over it. “No, that’s not it. I used to wear a red hooded cape.”

“Ah.” This was the strangest revelation of all. He had definitely never heard of a grown-up Red Riding Hood. “Survived the wolf, did you?”

“Not exactly.” She grinned a sudden feral grin, and her eyes flashed. “I don’t know why everyone’s so freaked out,” she said to Belle. “He might look like Rumplestiltskin, but it obviously isn’t him.”

“Not everyone has your superior senses,” Belle pointed out.

“True. So,” she put her hands on her hips. “You guys need a room?”

“Two rooms,” Belle corrected her.

Ruby smiled slyly and glanced at their linked hands. “You sure about that?”

“Yes, I’m sure.”

She rolled her eyes and flounced to the desk. “Would you play along if I told you that we only had one room available?”

“No.”

“You’re no fun.” Ruby pouted and held out two keys. “Here. Right up the stairs.”

“Thank you.” As she took the keys, Belle reached out to hug the woman again. “It’s so good to see you again.”

“I missed you,” Ruby whispered.

“As far as you know I’ve only been gone two weeks.”

“Know-it-all.”

Belle giggled and led Hamish up the stairs, handing him a key at the top so that he could let himself into the room. He smiled faintly back, and she put a hand on his arm. “Are you okay?” she asked.

“Yeah, just…” He rubbed the back of his neck and let himself into the room, hoping she would follow him. She did, closing the door behind her, and he tossed the key onto the desk before turning to look at her. “You told me you didnae have anyone, Belle. That no one cared for you, no one loved you. That’s no’ what I’m seein’.”

She was silent, staring at the floor between them.

“Grumpy, at the town line - he was thrilled tae see you. And Red down there...I thought she was gonna cry. These people cared about you. Why did you really leave?”

“Leroy and Ruby were my friends, that’s true, but…” Belle sighed and leaned against the desk. “I was the girlfriend - or mistress, or lover, or whatever - of the Dark One. I told you Rumple had a bad reputation, but it was more than that. He was cursed with a terrible dark magic, and he wasn’t always kind. Everyone feared him, and they kept me at a distance. Except when I could be useful, of course. Leroy and Ruby were the kindest to me, but they had their own lives to live and their own battles to fight. Besides, Rumple...Rumple and I were True Love.”

He tried to understand why that should matter, but in the end he shrugged helplessly.

“True Love is the most powerful magic there is,” Belle explained. “True Love’s Kiss can break any curse, defeat any evil. In our realm nothing is more treasured, and only a very lucky few find it. The thought of going back there without him - I couldn’t face it. I wasn’t brave enough.”

Folding his arms, Hamish nodded, staring at the ground. He could not, would not ask what he was to her if Gold had been her true love. He might not know much about fairytales, but he knew enough to know that true love could not be trumped. Even if she could love him, he would always be second to Gold, and that knowledge cut him much more deeply than he’d expected.

“Hey. What are you thinking?”

He looked up at her worried face and gave her a small smile. “That it’s late, and we have a long day tomorrow. We should get some sleep.” She didn’t look convinced, but he walked over and took her hand, leaning in to brush a kiss across her lips. “Good night, Belle.”

“Good night,” she said cautiously, still searching his face for something. She looked doubtful and unsatisfied as she left, and he closed the door and leaned against it, drawing a shuddering breath. Grumbling under his breath, he pulled a small notebook and a pen out of his pack and began scribbling down notes. There was no way he’d be able to sleep tonight, and if he wasn't going to sleep, he might as well work.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

12 crazy (but fabulous) garden ideas from Spain

Garden ideas picked up from holidays abroad have inspired garden designers for years.

Every year, there are several award-winning RHS show gardens based on places we visit, from Provence to the Yorkshire moors.

Some garden ideas will travel better than others. There will be a few that are like that bottle of retsina – so delicious in the taverna on the beach, but tasting of paint-stripper once you get it home.

‘Do you really think that’s a good idea?’ These stray kittens adopted Hugo and Anna. They’re clearly astonished to find someone up and taking photos at dawn, when most people are sensibly in bed. And I like the idea behind them – hanging an ornamental window grille on a blank wall rather than over the window.

But I recently had a short break with my brother, Hugo, and sister-in-law Anna in their house in El Canuelo, a small mountain village, near Periana in Spain. I spotted lots of ideas that I loved for their sheer exuberance and use of materials.

Some were crazy (at least for Northern hemisphere gardens). Some were perfectly sensible garden ideas.

I leave it to you to decide which is which.

Crochet your own sun awning…

There is a street in Alhama, Andalucia, which creates shade by hanging crocheted mats between the houses.

A variation on the tasteful cream sail – hang an all-weather crochet mat out to shade your terrace for the summer. And it’s great recycling – you can crochet old plastic bags!

I asked crochet blogger Emma Varnam whether this would be easy. ‘Essentially, they’re using the granny square technique, so it wouldn’t be difficult. I haven’t tried crocheting with recycled plastic bags yet myself, but plan to give it a go. You could also use recycled t-shirt yarn.’

I googled ‘crocheting with plastic’, and discovered a whole world of crocheting with recycled strips of plastic bags. It’s known as ‘plarn’ and is easy to make yourself.

There are lots of YouTube videos about crocheting with plarn, many of which are about making bedroll mats for the homeless.

I couldn’t find ‘crochet your own sun awning’ anywhere, but you may be handier than me and be able to work it out for yourself.

Or hang brightly coloured parasols…

The same street last year. They used brightly coloured umbrellas/parasols in netting to create shade. Not the most resilient of treatments – this was taken towards the end of the season, when quite a few umbrellas had clearly blown away.

Brightly coloured umbrellas strung together to create a shade awning in a street in Alhama, Spain. Photo by Jane Campbell

There are quite a few pictures on Pinterest showing streets in Portugal with this treatment.

Edge your border with car tyres…

Recycle car tyres as border edging… I particularly love this one, because the car tyres have been painted in pretty pastels. That seems so counter-intuitive, but it’s great.

Car tyres, sliced in half and buried in the ground as border edging (the border itself had just been cleared). They are painted duck egg blue and green, a soft pale pink and cream.

You can see the colours a bit better here.

This treatment could be good in an allotment and it also gives the plants lots of support.

Improve pot drainage with a pretty stand…

Pot stands improve drainage. Sometimes they are too effective, and the pots dry out. But if you have plants like pelargoniums or succulents, then a pretty pot stand will be prevent their roots from sitting in water. And so much more attractive than pot feet.

I also like the way the colours of this pot echoes the floor tiles. I think it would be great to see a return to patterned pots – but they do need to be good quality.

Paint a ‘skirting board’ outside your house as well as inside…

This is the sort of idea that might not work so well in a Northern hemisphere, but I do love the use of colour outside in Spanish houses. It’s both exuberant and controlled – colour is part of the architecture.

A yellow paint ‘skirting board’ harmonises with the tiles and really makes this terrace area at the Bar El Canuelo work. Note that the step risers are painted in the same yellow.

More painted walls at Bar El Canuelo. I love the painted frame around just half the window.

Spray paint your solar lights…

Hugo doesn’t like the blue-ish tinge to the solar lights he bought for his new cactus and succulents bed. So he has spray-painted the lights yellow. He also reduce the height of the spike – when he bought these solar lights they were supposed to stick up above the ground.

Change the colour of your solar lighting by spraying it with paint.

Line your garden path with architectural plants…

This has to be one of my favourite garden ideas from Spain. I just love the idea of someone staggering down the path (see photo below) when they’ve had a few….especially as there is no handrail – possibly another quite Spanish touch.

I think this looks beautiful, but it is quite definitely prickly.

A front garden path and steps, lined with agaves. Striking but prickly!

Pots on walls – don’t forget safety and drainage!

If you have a pot on a high wall, it may be blown off (onto someone’s head).

One solution is to cement the pot onto the wall, but that will prevent it from draining. Here at Bar El Canuelo, they have drilled a hole in the side of the pot, and added a small drain.

Pot cemented onto a wall, with a drainage channel made of a piece of local roof tile.

Pots on walls instead of pictures…

I love the Spanish use of pots on walls, especially as the pots themselves are often so beautiful. I think this is something that could work elsewhere, especially as ‘indoor gardens’ and houseplants are now gaining such popularity.

The Bar El Canuelo with its traditional Spanish wall pots. So pretty!

I love this pot. Be aware of watering issues when you hang pots on walls – you don’t want water trickling down the wall. Also hanging pots dry out more quickly than pots on the ground, so choose plants, such as pelargoniums, that are happy with drought.

Hang a curtain over your front door…

Now you may think that this is a ‘hot countries’ only idea.

But our front door in Kent gets baked by the morning sun, and the paint cracks within months of re-painting. We can see that there are fittings for a curtain rail just above the front door (on the outside of the house). I believe these were probably common in Victorian times, but I’ve never seen a photo of an English door protected by a curtain.

The curtain hung over this front door protects the paint on the door from hot sun and wind. It also insulates the house – a good idea for Northern climates?

It’s a great idea, but I’m not quite sure….it would probably get quite muddy in winter.

Effective garden ideas: a screen with large holes in it….

Hugo and Anna’s house has one next-door neighbour, and they share a continuous terrace.

Thick walls and climbing plants – but this privacy screen has large ‘windows’. But you can’t see the washing line on the other side, can you? I promise you – there was washing hanging up just on the other side when I took this.

The garden screen is a thick white wall with large window holes cut in it. Once again, this seems quite counter-intuitive as garden ideas go – isn’t the point of a screen to prevent you from seeing anything?

But holes mean that wind is broken up, and it also lets light in. Somehow this terrace feels completely private – it must be something about the thickness of the wall and the lavish planting.

Paint fencing and gates in contrasting colours…

Paint gates and railings in contrasting colours. This leads to ‘casitas’ (flats or apartments) to rent overlooking the pool at Bar El Canuelo.

I think the Spanish are much bolder about exterior paint colours. We’d be much more likely to paint gates and fencing like this all one colour, often either black or white.

I think I probably wouldn’t choose to tile my house orange, but I like the way the gate, the stone steps and the orange tiling harmonise, and with the roof tiles too.

Eating outside – secure the tablecloth with weights

Clip on weights to secure the tablecloth. The tablecloth is on Hugo and Anna’s terrace, which is quite sheltered. But there is an occasional gust of wind, which can whip your supper away. with a smile and a flourish…

Do everything with a smile and a flourish…

This delightful Spaniard was on her way to work, but found the time to exchange a few words, a smile and suggest a pose for the camera.

On her way to work at the Bar El Canuelo…

Hugo and Anna’s house Los Alamos , at Le Canuelo, is available to rent from Sawdays.

The view from Hugo and Anna’s terrace just as dawn is breaking.

And the El Canuelo shared pool, taken early in the day, before the sun got too hot.

Next week’s garden ideas come from the amazing Jardin Agapanthe in Normandy, France. It’s one of the most exceptional gardens I’ve ever visited, and is a mix of French classicism and exotic fantasy.

To get the Middlesized Garden into your inbox every Sunday morning, enter your email address at the top of this page.

Pin for later:

The post 12 crazy (but fabulous) garden ideas from Spain appeared first on The Middle-Sized Garden.

from The Middle-Sized Garden http://www.themiddlesizedgarden.co.uk/12-crazy-fabulous-garden-ideas-spain/

0 notes

Text

And so it was that, a week later, Granny locked the cottage door and hung the key on its nail in the privy. The goats had been sent to stay with a sister witch further along the hills, who had also promised to keep an Eye on the cottage. Bad Ass would just have to manage without a witch for a while.

Granny was vaguely aware that you didn't find the Unseen University unless it wanted you to, and the only place to start looking was the town of Ohulan Cutash, a sprawl of a hundred or so houses about fifteen miles away. It was where you went to once or twice a year if you were a really cosmopolitan Bad Assian: Granny had only been once before in her entire life and hadn't approved of it at all. It had smelt all wrong, she'd got lost, and she distrusted city folk with their flashy ways.

They got a lift on the cart that came out periodically with metal for the smithy. It was gritty, but better than walking, especially since Granny had packed their few possessions in a large sack. She sat on it for safety.

Esk sat cradling the staff and watching the woods go by. When they were several miles outside the village she said, “I thought you told me plants were different in forn parts.”

“So they are.”

“These trees look just the same.”

Granny regarded them disdainfully.

“Nothing like as good,” she said.

In fact she was already feeling slightly panicky. Her promise to accompany Esk to Unseen University had been made without thinking, and Granny, who picked up what little she knew of the rest of the Disc from rumour and the pages of her Almanack, was convinced that they were heading into earthquakes, tidal waves, plagues and massacres, many of them diverse or even worse. But she was determined to see it through. A witch relied too much on words ever to go back on them.

She was wearing serviceable black, and concealed about her person were a number of hatpins and a breadknife. She had hidden their small store of money, grudgingly advanced by Smith, in the mysterious strata of her underwear. Her skirt pockets jingled with lucky charms, and a freshly-forged horseshoe, always a potent preventative in time of trouble, weighed down her handbag. She felt about as ready as she ever would be to face the world.

The track wound down between the mountains. For once the sky was clear, the high Ramtops standing out crisp and white like the brides of the sky (with their trousseaux stuffed with thunderstorms) and the many little streams that bordered or crossed the path flowed sluggishly through strands of meadowsweet and go-fasterroot.

By lunchtime they reached the suburb of Ohulan (it was too small to have more than one, which was just an inn and a handful of cottages belonging to people who couldn't stand the pressures of urban life) and a few minutes later the cart deposited them in the town's main, indeed its only, square.

It turned out to be market day.

Granny Weatherwax stood uncertainly on the cobbles, holding tightly to Esk's shoulder as the crowd swirled around them. She had heard that lewd things could happen to country women who were freshly arrived in big cities, and she gripped her handbag until her knuckles whitened. If any male stranger had happened to so much as nod at her it would have gone very hard indeed for him.

Esk's eyes were sparkling. The square was a jigsaw of noise and colour and smell. On one side of it were the temples of the Disc's more demanding deities, and weird perfumes drifted out to join with the reeks of commerce in a complex ragrug of fragrances. There were stalls filled with enticing curiosities that she itched to investigate.

Granny let the both of them drift with the crowd. The stalls were puzzling her as well. She peered among them, although never for one minute relaxing her vigilance against pickpockets, earthquakes and traffickers in the erotic, until she spied something vaguely familiar.

There was a small covered stall, black draped and musty, that had been wedged into a narrow space between two houses. Inconspicuous though it was, it nevertheless seemed to be doing a very busy trade. Its customers were mainly women, of all ages, although she did notice a few men. They all had one thing in common, though. No one approached it directly. They all sort of strolled almost past it, then suddenly ducked under its shady canopy. A moment later and they would be back again, hand just darting away from bag or pocket, competing for the world's Most Nonchalant Walk title so effectively that a watcher might actually doubt what he or she had just seen.

It was quite amazing that a stall so many people didn't know was there should be quite so popular.

“What's in there?” said Esk. “What's everyone buying?”

“Medicines,” said Granny firmly.

“There must be a lot of very sick people in towns,” said Esk gravely.

Inside, the stall was a mass of velvet shadows and the herbal scent was thick enough to bottle. Granny poked a few bundles of dry leaves with an expert finger. Esk pulled away from her and tried to read the scrawled labels on the bottles in front of her. She was expert at most of Granny's preparations, but she didn't recognise anything here. The names were quite amusing, like Tiger Oil, Maiden's Prayer and Husband's Helper, and one or two of the stoppers smelled like Granny's scullery after she had done some of her secret distillations.

A shape moved in the stall's dim recesses and a brown wrinkled hand slid lightly on to hers.

“Can I assist you, missy?” said a cracked voice, in tones of syrup of figs, “Is it your fortune you want telling, or is it your future you want changing, maybe?”

“She's with me,” snapped Granny, spinning around, “and your eyes are betraying you, Hilta Goatfounder, if you can't tell her age.”

The shape in front of Esk bent forward.

“Esme Weatherwax?” it asked.

“The very same,” said Granny. “Still selling thunder drops and penny wishes, Hilta? How goes it?”

“All the better for seeing you,” said the shape. “What brings you down from the mountains, Esme? And this child - your assistant, perhaps?”

“What's it you're selling, please?” asked Esk. The shape laughed.

“Oh, things to stop things that shouldn't be and help things that should, love,” it said. “Let me just close up, my dears, and I will be right with you.”

The shape bustled past Esk in a nasal kaleidoscope of fragrances and buttoned up the curtains at the front of the stall. Then the drapes at the back were thrown up, letting in the afternoon sunlight.

“Can't stand the dark and fug myself,” said Hilta Goatfounder, “but the customers expect it. You know how it is.”

“Yes,” Esk nodded sagely. “Headology.”

Hilts, a small fat woman wearing an enormous hat with fruit on it, glanced from her to Granny and grinned.

“That's the way of it,” she agreed. “Will you take some tea?”

They sat on bales of unknown herbs in the private corner made by the stall between the angled walls of the houses, and drank something fragrant and green out of surprisingly delicate cups. Unlike Granny, who dressed like a very respectable raven, Hilts Goatfounder was all lace and shawls and colours and earrings and so many bangles that a mere movement of her arms sounded like a percussion section falling off a cliff. But Esk could see the likeness.

It was hard to describe. You couldn't imagine them curtseying to anyone.

“So,” said Granny, “how goes the life?”

The other witch shrugged, causing the drummers to lose their grip again, just when they had nearly climbed back up.

“Like the hurried lover, it comes and goe-” she began, and stopped at Granny's meaningful glance at Esk.

“Not bad, not bad,” she amended hurriedly. “The council have tried to run me out once or twice, you know, but they all have wives and somehow it never quite happens. They say I'm not the right sort, but I say there'd be many a family in this town a good deal bigger and poorer if it wasn't for Madame Goatfounder's Pennyroyal Preventives. I know who comes into my shop, I do. I remember who buys buckeroo drops and ShoNuff Ointment, I do. Life isn't bad. And how is it up in your village with the funny name?”

“Bad Ass,” said Esk helpfully. She picked a small clay pot off the counter and sniffed at its contents.

“It is well enough,” conceded Granny. “The handmaidens of nature are ever in demand.”

Esk sniffed again at the powder, which seemed to be pennyroyal with a base she couldn't quite identify, and carefully replaced the lid. While the two women exchanged gossip in a kind of feminine code, full of eye contact and unspoken adjectives, she examined the other exotic potions on display. Or rather, not on display. In some strange way they appeared to be artfully half-hidden, as if Hilts wasn't entirely keen to sell.

“I don't recognise any of these,” she said, half to herself. “What do they give to people?”