#it's both a game and an opportunity to refine my theory by exploring why others think the Book is real

Text

I don't think the Book in Bungou Stray Dogs is real, at least not insofar as there is a skill-created item that bends reality when alternative realities are written into its pages. Fyodor has convinced both the meta audience and the characters that the Book exists, just like he manipulated Ace into killing himself and for similar reasons. That being said, by claiming that such a thing exists, ensuring that there are "rules" to such a thing that obfuscate the most glaring limitations and contradictions likely to cultivate doubt, and leveraging the resources available to them, Fyodor and the Decay of Angels are able to influence others' actions and amplify their psychological and material impact, thus effectuating the reality they wanted.

(It's why visualization is an effective tool for accomplishing goals, by the way. Envisioning the reality you want for yourself vividly and emotionally stimulates your brain chemistry into experiencing and recording that reality as if were a memory or sensory perception, influencing your subconscious understanding of its attainability— which then lends you the motivation, confidence, and self-efficacy to make it so.)

It's not only Fyodor who rewrites reality by convincing others that it's possible. Natsume Sōseki rips out the pages of the third volume in the series that Odasaku is reading, informing him that there was an ending, but it was atrocious, so Odasaku should write his own. Odasaku was in a state of inertia, suffering his reality on belief it was immutable. His encounter with Natsume made him realize that the future he saw remained the same only if everything preceding it did too. Just because there was a certain outcome to his choices didn't mean he had to accept it— he could make different choices. While he did not get the outcome he wanted for himself, he nevertheless shaped his outcome with his choices. He couldn't change the choices of others, but he chose how he responded to them.

That's what he imparts on Dazai too. Perhaps much of his suffering isn't within his ability to change. But where he could choose wonder and goodness, he should.

It's a recurring theme for most of the characters since the uncertainty of existence and the subjective nature of reality framed much of their namesakes' works, but to name a few:

Yosano thought she couldn't live because her skill was too cruel. So Ranpo offered her a reality where her skill's exploitation wasn't inevitable, but a choice that was hers to make.

Ranpo thought he was alone and surrounded by monsters, rendering his world terrifying and colorless. Fukuzawa rewrote Ranpo's reality by reframing the predatory malice Ranpo perceived in others as clueless ignorance. He gave Ranpo means to channel and celebrate his perceived differences, but impressed on him that he and others had inherent value worth protecting. Because Ranpo believes him, he's surrounded by people instead of monsters. Further, the glasses Fukuzawa gave Ranpo were a cheap trinket, but because Ranpo confers on them his acquiescence to Fukuzawa's narrative, they facilitate Ranpo's remarkable powers of deduction.

N revealed to Chuuya that self-contradicting singularities can become stable in lifeforms if sealed by human will, which can be imparted on inorganic lifeforms as coded patterns since will is manifested so long as the lifeform believes itself capable of will. He needed Chuuya dead before Verlaine came for him but didn't want Arahabaki to die with him if it were possible instead to separate it from Chuuya and weaponize it by other means. Chuuya wasn't willing to donate his singularity to N's military research, so N attempted to bypass Chuuya's will by (i) convincing Chuuya that he wasn't human and (ii) torturing him into speaking a code phrase that N claimed would separate Chuuya from his singularity. It was important that Chuuya believed himself to be nonhuman because if he thought he was preprogrammed to accept the code phrase, he was more likely to cede his will to the code phrase on belief he wasn't capable of resisting. N also needed Chuuya to say the code phrase because if Chuuya chose to say it on the belief that saying it would end the torture by releasing Arahabaki, then he'd manifest the will to break the seal (even if subsconsciously). Chuuya wouldn't relinquish Arahabaki on his own, so N had to craft a reality where Chuuya didn't have a choice by convincing him of the same. Chuuya decided he did have a choice, so that was the reality that became realized.

If there is no objective, preordained reality, then reality becomes malleable and subject to revision. Not because of any preternatural superpower, but because people operate within the limits they perceive to exist. The Book doesn't need to exist to influence the characters; they think it exists, so they behave as though it does, functionally altering their realities around its existence.

But, for each situation I can recall that is attributed to the Decay of Angel's possession of the Page, there is another explanation that is more plausible and very much feasible based on the Decay of Angels' evidenced resources and modus operandi. They don't need the Page to orchestrate what they did, but convincing the Agency that they have the Page inflated their ability to inflict terror and amplified their influence over the variables molding the Agency's perception and behavior.

Anyway. If you give me any instance of the Book bending reality, I'll tell you why I disagree and what I think actually happened.*

*Don't cite to Beast. I haven't read Beast yet, so I won't speak to it.

#bungou stray dogs#bsd#it's both a game and an opportunity to refine my theory by exploring why others think the Book is real

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carl as a half-human Headcanons/Backstory

So I kinda wondered why Carl wasn't like the other 3 robots. Obviously, he's not a cyclops, his voice is much more humanly compared to the others, and his actual structure resembles more of a human than a robot in a way. So I came up with the theory that he's half human!

He could just be a more refined robot, but that's boring!

Let's begin!

• Dynamike, the holy creator of all robots, found a way to incorporate real human brains into robotic bodies (I may or may not have been just a little inspired by Alita)

• Carl's brain belonged to a young and arguably nerdy high school student who had a bright future ahead of him, he had an amazing track record with straight As and stellar test scores alongside a passion to learn all above that.

• But one day, he vanished. And nobody knows why. Some say it was the pressure put upon him to succeed, and some say he was kidnapped.

*TW: death/corpse*

• The police investigated the case, with his family hoping he was alive, however before the police could, Dynamike found his lifeless body somewhere in a creek near the woods--a somewhat distance away from Brawl Town.

• He saw this as his golden opportunity to test his newfound science, and already had a robot body prepared for this occasion.

• He extracted the brain from Carl's body and wired it on to the robot mold, the dual light eyes on the construction helmet lit up, while the bot flashed a metallic smile.

• "I'm detecting seismic activity!" were his first words. Dynamike didn't know what to name him, in fact, there was nothing on the body to help identify the brain's owner post-mortem.

• Dynamike decided to name him after what he would have named his first-born son.

• "Carl is my name, geology is my game!" said the newly named humanoid, while preserving the diction he learned from his desired college major in his past life.

• Unfortunately, Dynamike saw Carl as a perfect opportunity for him to make more money, rather than a thing that he can call his own.

• Dynamike sent Carl to mine in the deep rocks of Brawl Town, bringing home gems and riches to follow, but because of his human brain, Carl sought for more.

• He didn't necessarily feel human emotion, like sympathy at this point, the only prominent humanly trait Carl possesses is his geniusness. But at the same time, he was as curious as a cat, and wanted to experience life out of solitude.

• Carl didnt know anybody outside of Dynamike, but one day while Dynamike was asleep, Carl decided to sneak out and try to meet new people, even in the dead of night.

• He didn't know what he would expect, he was hoping for friendly people to come and talk to him, not being aware of the social norms of the universe--he didn't know everybody would be asleep.

• Carl ecountered danger amongst the darkness, that of which being the evil robots (that everyone brawls against). He tried his best to flee, but he realized that fleeing would only prolong his inevitable destruction. He blindly, yet tactfully threw his pickaxe in such an angle that would hit the robot attacking him while it would come back to him like a boomerang would.

• The robot stopped chasing him and fell to the floor. Carl let out a sigh of relief and preceeded to try to find his way back to Dynamike's house.

• After that event, he felt all types of human emotions: bravery, strength, fear, and pride. But he couldn't find his way back home, and at that point, the clock had just struck 3 in the morning and if Carl didn't hide, there would be more bots out there to get him.

• Knowing where he was, Dynamike found Carl and took him back home, where he demanded him clearly not to sneak out during the wee hours of the morning.

• That night, the humanoid couldn't stop thinking about what had happened. He was almost giddy and jumpy for the rest of the day--it was the first time, in both of his lives, that he ever felt that brave or strong.

• One day, he told Dynamike how confident he was--to finally Brawl like the rest of his robots do. Dynamike was very hesitant to agree. He told Carl that he was his prized possession, and that even though it seems like he's just using him for free labor, it's ultimately because he wanted to keep him around.

• Dynamike was aware of how Carl felt with his human brain. He was aware that he felt restricted and isolated from the rest of the world.

• "You know, Mister, I am unfinished. I don't have real arms, I don't have real legs, I don't have real eyes, but most of all I don't have a real heart, but I learned that I can make one myself. It's physically impossible, but I don't mean it literally for that matter. But I can explore the world and make one from scratch, and I can make friends too and be a part of a whole! I-I just need your permission to do that." (He also loved reading fiction in his past life)

• Dynamike then told him to go out and live his life. "Stop usin' big ol' crappy words I ain't understand, you do it err'y day. You got me! You're super diff'nt Carl! You're like the son I ne'er had! I'd be a sad ol' man if you turn out to be one too!"

• Carl knew he's growing his own heart since realizing his full potential. He started to train to Brawl, and at that point he had already mastered the physics behind his pickaxe-boomerang type attack--he just needed to test it out.

• The other brawlers started seeing Carl out, wondering who he was--even the full-robots didn't know of his existence.

• "He's not like us isn't he?" Barley asked Rico. "No. Sawwwwwryyyy." Rico replied. Barley then questioned once again: "He's-he's quite humanly, isn't he?"

• Carl conversed and thought like a human, had humanly mannerisms, and now felt emotions like a human--it's just that he doesn't look like a human.

• He felt very ostracized in many ways because of his differences, even before talking to other brawlers. For some odd reason one day, Carl felt thirsty, and unsure of how to satisfy it, he tried to buy a drink from Barley's bar.

• "I don't think that would be much of help," said Barley, "but I drink this all the time!" He handed the newcomer a glass of oil--and he knew exactly what it was from the get-go.

• "Is this oil, sir?" said Carl. Barley nodded and encouraged him to try it. From the first sip, Carl already accustomed to the taste, and vowed to drink it as a part of his daily fuel.

• From that point on, Barley and him became allies--but Carl wanted to make a human friend.

• One day, he encountered the local red-headed girl, Jessie, outside of a practice area.

• "I see we have a newcomer in town, I'm Jessie, and your name is?" Carl responded with his name, with his very humanly voice.

• Jessie was very confused while hearing his voice, "you don't sound like you should"

• Carl was disappointed hearing this, he felt even more different, and it showed in his expression.

• "But I don't judge! You seem pretty cool! What's your weapon? Maybe we can team later if you want!"

• Jessie became Carl's first ever human friend, and they warmed up to one another, which lead Jessie to introduce him to a large number of human brawlers that made him feel more humanly than he had ever felt.

• "It appears that I have a crisis every day. My superior has a brain but my inferior is just metal. I'm not one or the other, but an ugly mix of both." he told his human friends. And Carl realized he had discovered more human emotions--pity, insecurity and jealousy.

• But his new friends remind him every day about his potential, and that if his mind allowed him to, he can eventually complete his heart.

• Carl eventually gains the skill and confidence to brawl successfully, with his powerful human brain and resilient metal exterior--he even incorporated his minecart into the mix!

• Meanwhile, back at home, his family still doesn't know where Carl (or if that's REALLY his name) is. His body vanished and there was absolutely no trace of him--not even a sign of whether he was alive or not.

• Carl gets weird dreams of his family back at home, not knowing who they are--he gets them so frequently that he even asked Dynamike what they meant--he frantically told him not to worry about it.

• Despite this, Carl still faces the challenges of fitting in, and whether or not he can be considered truly human--or at least human enough. But with his new skills, intelligence, and his developing heart, now he is reminded of what makes him human to other people.

That's all! I hope you enjoyed! Let me know what other headcanons you'd like to see!!

#carl#brawl stars#brawl stars carl#brawl stars headcanons#brawlstars#dynamike#brawl stars dynamike#brawl stars barley#barley#brawl stars jessie#jessie#alita#i was inspired by alita#half human#headcanon#robot#human#long post#carlita: brawler angel

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seasonally Appropriate, part I: A Long Look at Castlevania: Symphony of the Night

So it's Halloween season, and I thought maybe it would be interesting/entertaining for me to tackle some themed content. So here we go.

Castlevania: Symphony of the Night.

There are few video game series that so clearly fit the season as Castlevania. A series that usually has Dracula as its final boss, with any number of mummies, werewolves, and Frankenstein's monsters prior to the ultimate showdown with Bram Stoker's Wallachian sensation, there are few that are perhaps a better fit for the season. And this is just a small sample of the horror and horror-adjacent enemies (we've also got your standard zombies, ambulatory skeletons of varying sizes, gargoyles, giant bats, and giant spiders, gorgon heads, Medusa herself, and even the grim reaper).

But despite the parade of classic horror monsters, Castlevania has never really been scary. It's really always been more of a sort of horror fantasy than anything.

Most installments prior to Symphony of the Night featured you playing as a muscular hero who is the latest scion of the Belmont clan, a powerful, nearly barbarian folk whose sole heirloom appears to be an enchanted chain whip (with a spiked morning star on the end) which is consecrated for killing vampires and other creatures of the night. It's a good thing they have it, because Dracula, in life an evil sorcerer, and in death the king of vampires, seems to come back to life every century. Sometimes this happens on its own, sometimes he's resurrected by various disciples.

Listen, the lore here is neither deep, complex, nor consistent. Anyway, Symphony of the Night marked an interesting fork in the series development.

Let's look back for a minute at the mid-90s.

More below the cut.

It was the dawn of the fifth generation of video game consoles. Sony's PlayStation, Sega's Saturn, and Nintendo's N64 (the three consoles of this generation that mattered, and that are worth remembering as more than a footnote) were collectively the vanguard of 3D graphics in game design. Blocky and pixellated as a lot of those games look, believe it or not, it was an exciting time to be into video gaming. Boundaries were being pushed. New genres (such as survival horror) were being invented. And many developers were struggling mightily to find ways to translate their existing franchises into three dimensions.

TV Tropes refers to this phenomenon as the Polygon Ceiling. Some series, such as Final Fantasy, had a relatively easy, painless transition into 3D. In fact, RPGs broadly speaking weathered the change with few growing pains, if any. The main reason for this, I think, is simply that the mechanics that defined an RPG had very little to do with how those kinds of games were presented, in terms of graphics. The switch from 2D to 3D didn't really change anything about the essence of an RPG, and in most cases was actually beneficial.

The same was not true of more action-oriented titles, such as Mega Man, or Contra, or Ninja Gaiden, or... well, Castlevania. For an RPG, the way a player and the player's character(s) interacted with the world was fairly rudimentary, and the specifics were largely (in most cases) inconsequential. But in an action game, the player's interaction with the game's world is everything. Running, jumping, shooting, slashing, exploring, commandeering vehicles... The feel of these things was every bit as important as how they looked. And the specific details of the mechanics were important. Does the character have a life bar, or do they die in one hit? Can they control their jump mid-air, or are they committed once they launch themselves? Is the game a side-scroller, or a top-down action game? Is there a lot of jumping and verticality to the environments, or is it largely a horizontal affair? And so on, and so forth.

The transition to 3D presents a couple of problems, then.

Problem one is a pet theory of mine: 3D gaming compels a certain adherence to reality, at least notionally. I think that, subconsciously, players are better able to accept the more abstracted characters and environments of a 2D game because its nature as a 2D game means it is not operating in a space the player can recognize as real. So the abstractions – things like floating platforms, massive leaps, double-jumping, etc. – don't really seem troubling. But 3D environments have to look, if not realistic, then at least plausible given the restrictions or abilities of the setting. Platforms hanging in mid-air are an abstract thing that's du rigeur in a 2D game, but they look really weird in a 3D game without some kind of justification.

Problem two is less theoretical: 3D gaming requires a from-the-ground-up re-think of level design. Part of the reason the level layouts of a 2D side-scrolling game work at all is that the player has that side-on perspective that lets them see what's over the next rise, and react or plan their movements accordingly. 3D games generally don't allow for that, unless they're going for what's referred to as 2.5D – 3D graphics, but levels laid out and played the same as if they were in 2D. The reason this is a problem is the domino effect it causes. If you're re-designing the levels, you also have to re-design the way the player interacts with them. The player character's moveset has to change to accommodate this new setting. And then you have related problems to solve, which were never an issue in 2D games, such as camera control.

In essence, taking an established series from 2D into 3D changes everything. The environments, the way the player character interacts with said environments, the character's moveset, and the pacing. Meanwhile, franchises tended to be built on a certain consistency. You tend to buy a Contra or Castlevania or Mega Man game because you know what those games are like. The name indicates a certain kind of experience. So, the dilemma: How do you change literally everything recognizable about your game while preserving the essence of the experience so as to maintain continuity with what the franchise is all about?

Outside of Nintendo's major first-party franchises at the time, most of the heavily action-oriented series that were already big when the 3D revolution either:

Stayed 2D, and saw diminished exposure and popularity as a result (some went portable)

Went 3D, failed (sometimes after multiple tries), and died out in a console generation or two

Which brings us to Castlevania, and the fork in the road.

So, like most developers in the mid- to late 90s, Konami was trying to find ways to make their existing franchises work in 3D. This was at some point before Metal Gear Solid became their major cash-cow franchise.

Castlevania was a proven money-maker for them in the U.S. About the only entry they'd left in Japan had been Dracula X: Rondo of Blood, mainly because it was a game for the TurboGrafx-CD, which was doing almost nonexistent business in the States, and had been from its beginning. Which is a shame, really, because Rondo of Blood was damn near perfect. The Super NES conversion, Castlevania: Dracula X was good in general, but paled in comparison. But we'll come to that.

So naturally, the thing to do with their big franchises was to make them over in 3D. Which is exactly what they were doing with Castlevania on the N64. The result, Castlevania 64, was to be the the definitive statement of the series on modern consoles.

It... didn't work out that way.

Castlevania 64 went on to become one of the defining examples of what it meant to hit the Polygon Ceiling. Later that same year (1999), Konami brought out Castlevania: Legacy of Darkness, which expanded on its ideas and made some improvements, but still wasn't all that well received. But there was this other game that came first...

Koji Igarashi, a programmer at Konami, had put together a B team and gotten permission to make his own spin-off Castlevania game for the PlayStation, titled Castlevania: Symphony of the Night. It was going to be a 2D game, so Konami didn't put much effort into marketing or advertising it, at least not in the U.S. I don't know about elsewhere in the world, but in the U.S. at least, there was a certain drive to leave 2D gaming behind in favor of 3D. A certain amount of this (it's difficult to say how much) was admittedly driven by the console manufacturers and software publishers themselves, in an effort to sell more games by making said games look as cutting-edge as possible.

But gaming in 3D was in a transitional state. And most transitions are ugly and awkward. Two-dimensional games like Symphony of the Night or Rayman or Silhouette Mirage lacked a lot of the immediate wow factor that 3D games possessed; they were an iteration on what had come before in a generation when everyone was fixated on what was new and shiny. But at the same time, they had the benefit of established technique. Developers had at least two console generations' worth of history to draw upon when it came to designing a 2D game, to help them understand what worked or didn't work, and why. Many conventions of game design had been pioneered in the 8-bit days – the third console generation – and had been refined in the fourth generation. This fifth generation and its newer technologies offered the opportunity to refine it further still.

Time has been unkind to many of these early 3D efforts. However impressive most of these games looked upon release, many of them have aged poorly. With controls that are often both clumsy and awkward, and with graphics that frequently looked rudimentary even one console generation removed, they can be hard to go back to. And I say this despite all my intense personal nostalgia for games in this period. Two-dimensional games, meanwhile, have frequently aged much better.

Symphony of the Night, for example, which went on to become the face of the Castlevania franchise.

It's a little strange to think about Symphony of the Night being the odd one out, nowadays. It, and all the portable games that chased after its success and were to varying degrees crafted in its image, became what the franchise was known for in the end. There's a reason the genre is called "Metroidvania". But this was where all that began, and as a non-linear exploration-based side-scrolling game with RPG elements, Symphony of the Night seemed like a weird fit for the series at the time it came out.

There was some precedent for this in the series prior. Castlevania II: Simon's Quest had seen the player character traversing the Transylvanian countryside looking for bits of Dracula in order to unite and destroy them, and thus break the curse upon him. It was also a non-linear and exploration-based side-scrolling game. However, it was bad at communicating with the player and providing the necessary clues to make sense of its challenges. Castlevania III: Dracula's Curse, meanwhile, featured multiple routes through its levels by the simple expedient of giving the player a discrete choice at the end of most stages leading up to Dracula's castle. Rondo of Blood featured multiple paths, but presented them more organically, by having branching pathways and hidden routes in the levels themselves, which often led to different subsequent levels when pursued.

But all of these were mere flirtations with the idea of exploration compared to the sprawling, open mass of content that was Symphony of the Night.

Likewise, the series typically featured physically imposing, practically barbarian heroes before. Symphony's immediate predecessor, Dracula X: Rondo of Blood, had about the most characterization the series had seen in any of its heroes with Richter Belmont, who went on his adventure not only because Dracula was a bad, bad man, but also because he had kidnapped Richter's fiancee (along with a few other village girls, and a young lady named Maria Renard, who could also be played once rescued).

In place of the usual pseudo-barbarian hero, Symphony instead features a new playable character, Alucard, Dracula's half-vampire son. His true name, according to the manual, is Adrian Farenheits Tepes (yes, really), which... I can't decide whether that's awesome or ridiculous. Anyway, he goes by Alucard, which of course is his father's name spelled backward, to symbolize his opposition to his father.

Alucard first appeared back in Castlevania III: Dracula's Curse, which Igarashi has stated was his favorite game in the series. There, Alucard was one of three possible partner spirits the main character could recruit, after first facing him as a boss enemy. In that game, Alucard had a weaker version of his father's trademark triple-fireball attack, and the ability to turn into a bat and fly to locations other characters couldn't reach (at the cost of a constant expenditure of special weapon ammo). There, he was probably the least useful of the three partner spirits. His bat transformation was really helpful in only a small number of situations, and his attack was weak even when powered up to the three-shot version, unless you could make all three shots hit the same target. And like all the partner spirits, he was more fragile than the main character.

He's appeared elsewhere in the series since. In addition to an appearance prior to Symphony in one of the old-school Gameboy entries, he also shows up (under the alias Genya Arikado) in Castlevania: Aria of Sorrow for the Gameboy Advance, as well as in Castlevania: Dawn of Sorrow for the original DS. His appearance in Symhony of the Night led to a change in how its heroes looked. Character designer Ayami Kojima has a far more shoujo design sensibility, and as a result the franchise's leads have tended toward being more slender and androgynous ever since, even in the games she didn't design characters for.

But getting back to Symphony of the Night, Alucard was the perfect character for what Igarashi had in mind for the game. Both in his personal identity and in the kind of character he was, he represented something altogether different from the series norm: a slender, impeccably dressed nobleman in place of a broad-shouldered, leather-clad warrior; a cold, remote swordsman over a muscle-bound whip-swinger. He served as much as anything else to communicate that Symphony of the Night was headed in a different direction from the rest of the games up to that point.

Most games in the series were fairly typical for side-scrolling action games. Enemies tended to be weak defensively, but packed a punch, and were intended to soften you up for the bosses. You had your standard layouts of platforms to navigate between, with spike traps and instant-death falls into bottomless pits as punishment for bad timing of your jumps. Your player character did not grow as the game progressed: You had a single weapon with which to attack the enemies, though Castlevania allowed you to supplement this with sub-weapons, which you could find scattered throughout the game's stages, and which required ammunition to use. The game, meanwhile, grew in difficulty as you progressed, requiring you to hone your skills as you went. What was unique about Castlevania was its difficulty (its particular mechanics put it on the high end of fair, for the standards of the day) and its medieval/gothic horror setting.

Symphony of the Night is still a side-scrolling game, but that's essentially where the similarities end. Igarashi took a page out of the Metroid playbook, and crafted a non-linear, exploration-based action game. Then, for good measure, he bolted on some basic RPG elements. So rather than a linear march to the endgame, the player is allowed – encouraged, even required! – to explore every nook and cranny, gradually acquiring new weapons and abilities as they go, and to revisit old locations with their new-found powers and abilities in order to open up new pathways.

Yet for all the ways it's different from the series that sired it, Symphony of the Night leaned more heavily on the (admittedly somewhat anemic) series lore than any game had previously.

Rondo never saw release in the U.S., which is a goddamned crime, even as I understand perfectly why Konami passed on localizing it. What we got instead was Castlevania: Dracula X for the Super NES (known as Vampire's Kiss in Europe). This version of the game has some interesting trade-offs going on. The graphics are somewhat better, since it's a Super NES game. However, the music, while nice, doesn't hold a candle to the CD soundtrack featured in the original game. It also loses out on the multiple routes that were perhaps the defining feature of the TurboGrafx-CD version, which seems more questionable. The result is something that feels very much like a bright, shiny consolation prize.

Symphony of the Night is set in the 1790s, about five years after the events of Rondo of Blood. Alucard himself first appeared in the fifteenth century during the events of Castlevania III, so he's been around a while already; Symphony is therefore tied to two different games in the series. But as much as there was a shared continuity between installments, their taking place a century apart meant that none of them really required you to have played the previous installments to appreciate the current one. It isn't the first game in the series to revisit a particular point in time and set of characters – the very first sequel did it, after all – but it is the first to show real growth of any kind in those characters. Richter returns in a startling reversal of his original role as vampire hunter, and Maria Renard is all grown up and looking to take care of things on her own. And while it's true that you still really don't need to have played Rondo of Blood to enjoy Symphony of the Night, there was that added layer of interest for fans of the previous game.

Among the many other things Symphony gets right is its gameplay. Overall, the game is a little on the easy side, but that's easy to forgive. One of the things that makes it easy is simply its design. As an exploration-based game rather than a linear side-scroller, a lot of the traditional instant-death traps (such as bottomless pits) really don't make a lot of sense from the standpoint of environmental design. Punishing the player's bad timing is basically antithetical to the design of a game like this. The challenge lies far more in figuring out the correct path to the end, instead. Instant-death scenarios would be deeply unfair in that context. Instead of running a gauntlet, the player is navigating a labyrinth.

As befits a game that takes up as much geographical space as Symphony of the Night does, the enemies show wide variation in shape, size, strength, and tactics. Their placement is likewise well-considered. Enemies of the same type only rarely occupy more than one region of the game's map, giving each region its own ecosystem. Many of them pose little threat, playing into the relative easiness of the game. They're there because fighting them gives you something to do as you traverse the castle. The real challenge is finding your way through... and, of course, fighting off the bosses.

While many of the bosses pose only a middling challenge, a few encounters are genuinely harrowing, and many of them – Olrox, Granfaloon, and Galamoth, just to name a few – make for fantastic setpiece fights.

In addition to its gorgeous and varied environments, Symphony also offers the player several different powers and abilities. Over the course of the game, Alucard gains access to powers that allow him the classic vampire transformations (into a wolf, bat, or mist) which are essential for navigating the environment. This is in addition to abilities such as double-jumping and being able to walk underwater. There's also a multitude of weapons the player can find, with a variety of abilities and drawbacks, as well as several with hidden moves.

The only place the game really falls apart is in its second half. After uncovering enough of the castle to find a particular item, then player can then face off against the seemingly final boss, only to discover that this boss isn't so final as previously believed. In fact, it's just the halfway point. The game then reveals that there is an entire second castle to explore, where the real final boss is hiding. This is great in theory.

In practice, it’s somewhat less great. The second castle is a mirror image of the first; take the castle, rotate it 180 degrees, and you have the second half of the game. The problems here are manifold.

It's not as interesting to explore, because you've seen all this before. The color palettes are altered in much of the reverse castle, but the layouts are otherwise exactly as they were in the first castle, right down to all of the secrets. But at the same time...

It's disorienting, because while essentially familiar, it's also upside-down. It constantly messes with your ability to navigate without constant reference to the map. And while it would be nice to praise clever level design that works both right side-up and upside-down, the fact that you can double-jump, high-jump, and fly means that pathfinding is trivially easy no matter which way the environment is pointed. And since you already have all the essential expansions to your moveset...

There's less to get excited about. Part of the appeal of any good Metroidvania game is the player character's slowly evolving moveset, which allows increased exploration of the game's environment. There's a small thrill at the "Ah-ha!" moment when you realize that your double-jump or ability to fly or turn into mist will allow you to access an area you couldn't reach previously, either granting access to new areas or to yet another new power-up, expanding your moveset further. But that sense of excitement goes away since you already have all the essential maneuvering capabilities. It also means...

Since you've already acquired all your essential abilities, there is no direction suggested by limitations upon your movements, as there would usually be in a game like this. Most Metroidvanias are structured so that there are initially only a few places you can go, with tantalizing hints of what might lie beyond currently accessible regions. Thus, while you're free to explore in the reverse castle, the lack of growing capabilities means every direction is arbitrary. You spend the whole latter half of the game just going wherever, because one direction is as good as another.

While the game still never gets really hard, the difficulty does spike in the inverted castle. Unfortunately, it does this mainly by just making the enemies give and take more punishment. Monsters who served as minor bosses in the first castle now show up as basic enemies. As a result, the game slows down as you slog your way forward.

The thing is, this doesn't make Symphony of the Night a bad game. It does mean the latter half falls apart a bit, and is somewhat disapointing as a result. Most of the time, when I play through it these days, I tend to stop once I reach the inverted castle. The level of novelty adn inventiveness on display throughout the first half tapers off pretty abruptly in the second half. But it's still overall a vastly entertaining game, and one that I love. It’s worth playing through by basically anybody.

Inverted castle aside, Castlevania: Symphony of the Night was a smash hit. It was one of the first PlayStation games I ever bought, somewhere in the spring of 1999.

I remember suddenly recalling, out of the blue one day, that I'd read about a Castlevania game for the PlayStation that was a little different from the rest of the series. That was it. I knew it existed. So renting it seemed like the safest bet.

The problem with rentals, of course, is that after the end of the rental period, they actually do expect you to give it back. And that was a problem, because after just about half an hour spent playing the game, I decided that this was one of the most phenomenal games I'd ever played. It went without saying that I wanted to own it. In fact I wound up picking up a copy that night (technically, it was after midnight, so that would really make it the following morning) for $20 at a Wal-Mart that was open 24 hours. I returned the rental the next day, since I wouldn't be needing it any more.

Really, I think I knew I wanted to own this game the moment I got into the Alchemy Laboratory, the second main area, and the first that really allowed for some exploration at the very beginning. It was perhaps the first area where everything I loved about the game came together perfectly: the graphics (lushly detailed and lovingly animated), the environments (big, eclectic in theme, and interesting to look at), and the music (as eclectic as the environments, beautifully orchestrated and arranged).

I still wind up digging into it for at least a little while every year – and, yes, it's usually around Halloween that I do. I don't usually go through the inverted castle, as I mentioned before. I have stuff to do, and my enthusiasm usually wanes around that point. But I did it this year, for old times’ sake.

It’s always a pleasure playing Symphony for the little details here and there throughout the game. But I especially took notice playing through it earlier this month, since I was playing it to finish it, and to take a more critical look at it.

For all that the PlayStation is routinely (and, let's be honest, correctly) assessed as a system with anemic 2D capabilities, Symphony of the Night is a 2D powerhouse for the standards of its day. And as pixellated as it looks when viewed on HD TVs or monitors today, it still looks fairly amazing.

There are all sorts of tiny details that work to sell the environments of the game as places with their own distinct identities. Birds nest in the belfries of the Cathedral. The frozen-over sections of the underground caverns have a thin skin of ice on the pools of water there, which will break off, a bit at a time, as you collide with them. Then you have the rats doing their rat business in the little inaccessible nooks and crannies of the Outer Wall. For that matter, the Outer Wall's weather will randomly change whenever you enter it: It can be clear, foggy, or raining. There's no effect on the gameplay; it's purely for effect. Then there's the way many enemies (not just bosses) have unique and involved death animations. This is on top of them being already highly detailed as it stands. And these enemies are rarely repeated throughout the game. Each area has its own unique ecosystem of enemies which aren’t often found elsewhere in the game. Seeing the full range of the game’s bestiary is in fact one of the few real joys of exploring the inverted castle.

The only part of the game that’s aged somewhat less gracefully is its 3D graphics, which thankfully don’t matter too much. There’s actually very little 3D in the game proper, and what’s there is used either as background elements (rushing clouds in the Cathedral and Clock Tower areas, and the clock tower itself), or as a supplement to the 2D graphics (the ice crystals that the Ice Maiden enemies use to shield themselves or shoot at you, the pulsing lake of lava, etc.). About the only instance of 3D where I cry foul is the wings of the giant bat. Those are honestly kind of embarrassing. Everything else is fine, if a bit low-fi. But I find myself getting pretty nostalgic for that, honestly.

Still, as easy as it is to get wrapped up in extolling the virtues of Symphony of the Night’s technical mastery, what should be kept in mind is that buried under all the flash is a solid game. Like the best Metroidvania titles, it challenges you not through your steel-trap reflexes but by your ability to navigate the world, to find the correct way ahead, to ferret out the secrets necessary to success. Unlike its predecessors, it presents not a gauntlet to be run, but a puzzle to be solved.

Because it amuses me, let’s take a look at some of the localization oddities of Symphony of the Night.

Someone at Konami – I'm about 80 percent sure this was someone on the localization team, not the original Japanese development team – was hell-bent on inserting fantasy and sci-fi literature references into the game.

The boss Granfaloon takes its name from a word invented by Kurt Vonnegut in his book Cat's Cradle. It's used to describe a collective of people whose commonalities might seem to be significant factors in their association, but which are in fact meaningless in the grand divine plan. This boss shows up in at least one later game (Aria of Sorrow), and is renamed to the more-appropriate Legion.

There's a handful of references to The Wizard of Oz, of all things. These come in the form of three different enemies: a scarecrow who jumps around fairly brainlessly, an enemy called Tin Man which is essentially a steam-powered machine full of blades, and an enemy called simply Lion which is described as being cowardly.

And then there are the references to J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Silmarillion...

This will be easier as a list:

The Nauglamir: In-game, it’s a necklace that raises the player’s defense. In The Silmarillion it’s a necklace made by the Dwarves for the Elvish king Thingol, which among other gemstones contained one of the Silmarils – a gem (out of a set of three) containing vast but frustratingly vague magical powers.

The Sword of Hador: In-game, it’s described as belonging to the House of Hador. This is a reference to The Children of Hurin, which is one of the main tales of The Silmarillion, and more recently was expanded into a book in its own right. The House of Hador is more famous for its dragon-crested helmet, but the game has a dragon helm as a major piece of Alucard’s equipment already, and the developers probably didn’t want to name one of the more important items after something in an intellectual property they didn’t own.

The Fists of Tulkas: In-game, they’re a set of gauntlets to be equipped for punching enemies. Tulkas in The Silmarillion is a god-like being whose area of divine responsibility is war.

The Mormegil: In-game, it’s described as a black-bladed sword, and by its statistics, it’s especially powerful against holy-aligned enemies. In The Silmarillion, it’s a sword used by Turin Turambar, of the House of Hador (though it’s not an heirloom of said House), which does indeed have a black blade, and a sinister past.

The Ring of Varda: In-game, it’s a ring that gives stat bonuses to the player. In The Silmarillion, Varda is a goddess of sorts – the queen of the highest tier of divine beings, just below the creator – who is associated with the stars.

Azaghal: In-game, a unique enemy who appears in exactly one location (the inverted version of Olrox’s quarters, for the curious). He is an enormous glowing phantom who swings a sword that’s at least twice the size of the player’s character. In The Silmarillion, he’s a Dwarvish king slain in battle by a dragon. He has a dragon-crested helm which is given to one of the Elvish princes after his death, which is the same helm that ultimately becomes the heirloom of House Hador, after changing hands a few times.

The Crissaegrim: In-game, it’s the most game-breakingly powerful sword the player can find, being a sword that strikes four times in the amount of time most other swords take to strike once, strikes diagonally upward and downward on two of its strikes, and has the best reach of any of the game’s other swords’ standard attacks. And you don’t have to stop moving to swing it. In The Silmarillion, it’s a mountain range where the Eagles dwelt. By the time of The Lord of the Rings, it no longer exists, having sunk into the sea along with much of the land where The Silmarillion takes place.

Castlevania has always borrowed from pop culture to some extent. The original game borrowed its boss monsters from classic horror movies and literature (Dracula, Frankenstein's monster, and the mummy), and its sequels up to this point borrowed still more. But the specific things being borrowed in Symphony of the Night have always struck me as weird. There's something a bit more... universal? (pun unintended) about Dracula or the mummy or the wolf-man or Medusa or... The list goes on. The Silmarillion and Cat's Cradle and The Wizard of Oz are more puzzling, at least to me. Maybe it's just that they're not in the public domain (well, The Wizard of Oz is; the book, at any rate). Maybe it's because they're not as firmly in the horror genre themselves, or even horror-adjacent.

The success of Symphony of the Night helped propel Koji Igarashi to the position of de facto steward of the franchise. After Konami's double failure to craft a worthy Castlevania in 3D on the N64, they decided to go smaller-scale for the series, at least for a few years. The next game, Castlevania: Circle of the Moon was released in 2001 for the Gameboy Advance. While it wasn't directed by Igarashi, it clearly aped Symphony of the Night in most respects. Regrettably, its overall quality wasn't one of them. Igarashi returned to the director's seat for the next several games in the series. He got his band back together (Michiru Yamane on music, Ayami Kojima on character designs) for Castlevania: Harmony of Dissonance, which has a somewhat divisive reputation among the fanbase. The follow-up, Castlevania: Aria of Sorrow, is often considered to be the first truly worthy successor to Symphony. The following games on the DS – Dawn of Sorrow, Portrait of Ruin, and Order of Ecclesia – saw diminishing returns.

Igarashi's success with his Metroidvania titles in the series eventually saw him put in charge of a new attempt to make Castlevania in 3D. The results, Castlevania: Lament of Innocence and Castlevania: Curse of Darkness on the PlayStation 2, were... competent, at least. I’ll probably talk more about those another time.

The Castlevania franchise ultimately got farmed out to Mercury Steam, a Spanish developer, who took the series in a different direction (though one of their games is at least to some extent a Metroidvania in Igarashi’s mold).

More recently, Igarashi's gotten back in the saddle. While he's no longer with Konami, he's been toiling away on a Kickstarter project called Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night, which follows aggressively in the footsteps of his Metroidvania games. His initial Kickstarter pitch leaned heavily into his success with the Castlevania franchise. While Ritual of the Night has yet to be released, his team put together a faux-8-bit homage to Castlevania III titled Bloodstained: Curse of the Moon, which seems to be positioned as a prequel to Ritual of the Night. It's fantastic, and is available for PC and all current consoles.

I’ve spent a lot of time talking about Symphony of the Night; I should probably discuss its availability for whoever is curious. I’ll break this down by systems.

Sony: By far, Sony’s systems have the widest availability for this game. The original PlayStation disc can be played on a PlayStation, PlayStation 2, or PlayStation 3, or via any halfway decent PlayStation emulator on PC. Almost any computer you can buy today will run PlayStation games just fine with emulation. In addition, this same version is available digitally as a PS One Classic on PSN, so you can download it version for the PlayStation 3, PlayStation Portable, PS Vita, or PS TV. Like most single-disc PlayStation games on PSN, it runs about five dollars. Then there’s Castlevania: The Dracula X Chronicles. This is a PSP release whose main purpose was to be a shiny new 2.5D remake of Dracula X: Rondo of Blood, a.k.a. Castlevania: The One That Got Away for many years in the U.S. However, you can easily unlock Symphony of the Night in it (as well as the original TurboGrafx-CD version of Rondo of Blood). This version of Symphony features a new voice cast and a rewritten script, which may or may not recommend it. The original game was never going to be High Drama even in some theoretical ideal form, and the original script and hamtastic acting at least gave it a kind of B-grade charm. As it stands, the newer version’s acting is more professional, but loses some of that overwrought but undersold charm. However, it's completely serviceable, and the fact is that all three games in the collection make it well worth a purchase. It's available physically (for PSP only) or digitally (for the PSP, PS Vita, and PS TV). Finally, there’s Castlevania: Requiem, a combo pack for the PS4 which contains both Symphony of the Night and the TurboGrafx version of Rondo of Blood, with the English translations and voice work from the PSP release. These updated versions of the game feature a new song that plays over the ending credits (more on that below). Castlevania Requiem also allows you to enable filters to soften the sharpness of the image, or to play it stretched fullscreen as well as in the original 4:3 aspect ratio with a variety of frames for vertical letterboxing.

Microsoft: An HD remaster of Symphony of the Night came out early in the Xbox 360's lifespan for Xbox Live Arcade. It offers a smoothing filter for the graphics, and a frame for the vertical letterboxing (the game itself is still presented in 4:3 aspect ratio with no option to stretch the image). The script and voice acting are the same as the original version. There are two brief CGI cutscenes in the original version of the game which were cut from this version to save disk space (originally, Xbox Live Arcade titles had to come in under a certain size limit), but nothing of value here is lost. The music for the ending credits has also changed from the original version. The original song, "I Am the Wind", was replaced with a new piece due to licensing issues. Again, personally, I think nothing of value was lost. "I Am the Wind" sounded tremendously out of place, tonally, compared to the rest of the game. In addition to the Xbox 360, this version of the game is also playable on the Xbox One via backward compatibility.

Nintendo: Nothing, sadly. The closest Nintendo ever got to this game was having a near-perfect port of the Japanese version of Rondo of Blood on the Virtual Console, but the VC's basically shut down at this point. You can still download games you've already purchased, but new purchases are no longer possible.

PC: No official release of Symphony of the Night has occurred on PC, despite it being an excellent candidate for Steam, because Konami is a shit company run by shit people, and they've decided to leverage all their intellectual properties for pachinko machines these days, which is a very shit thing for them to be doing. Your best bet for PC is to get the PlayStation disc and download an emulator.

#castlevania#symphony of the night#halloween#effortpost#deep dive#video games#video gaming#gaming#castlevania symphony of the night#castlevania sotn

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leveraging Player Motivation Models to Increase App Engagement – Part 1

Paula Neves is a Product Manager at Square Enix and describes herself as a gamer turned psychologist turned marketer working in mobile free-to-play games. Prior to joining Square Enix based in Montreal, Paula was the Chief Mobile Officer at Gazeus Games in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where she headed up user acquisition and product management. Paula is a proud member of the UA Society and a frequent speaker at industry events and conferences, where she eagerly shares her knowledge and experience from her 10+ years in the mobile app marketing industry.

Learn more about Paula from her Mobile Hero profile.

As an undergraduate in Psychology, a graduate in Marketing and a professional in the gaming industry, I’ve always tried to combine what I learned in college with what I do at work. Psychology and marketing go hand in hand, especially when it comes to designing games, and even more so when they’re Free-to-play.

In Free-to-play games, most systems and mechanics are built on the principles of behavioral psychology and we hear a lot about theories like risk aversion, reciprocity, endowment, and the like. But when it comes to planning your next game, for a long time I felt that our industry was missing a good game design framework that is built on science and psychology. That was until six years ago when I first heard of Scott Rigby and his work at Immersyve, and the guys at Quantic Foundry. I started going down the rabbit hole, coming across several interesting player motivation models that all have a recognizable psychology framework as a foundation, like the work done by Jason Vandenberghe and his Domains of Play and Ethan Levy and his Tower of Want.

This is the first part of a three-part blog series intended to explain what motivates players into picking up a game and continuing to play it. It’s a combination of psychology models transposed into gaming and its characteristics. This blog hopes to educate product managers, marketers and game designers on player psychology and how we can all leverage it to make a game that more people will play. Thankfully, this work is already being done by the people I mentioned earlier, so my intention here is to put it all together so that the knowledge is accessible to others.

Self Determination Theory and Long-term Satisfaction

The Self Determination Theory (SDT) is a psychological theory of human motivation that addresses three basic psychological needs including:

Competence: the need to experience mastery, growth and learning, and to feel successful and effective.

Autonomy: the need to feel that you’re in control of your choices and in harmony with your decision. In games, it translates to choice, customization and agency.

Relatedness: the need to be cared for and to care for, to be connected with others, knowing that you belong and matter.

According to the theory, these needs are innate, universal to everyone, and if met, will lead to self-motivation and growth. The theory also makes a clear distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic motivations: The former being caused by external factors, such as being paid to do your job or being made to feel guilty about not doing something. When said guilt — an external factor — motivates you to do something, that behavior is not self-determined. Intrinsic motivation, on the other hand, is when one feels inwardly motivated to achieve something in order to satisfy things like autonomy and competence.

For quite some time extrinsic motivation was judged as bad and intrinsic as good, but it isn’t so black and white. It’s almost impossible to have something — like a game — that will only motivate players intrinsically. As a game designer you must try to kindle more intrinsic than extrinsic motivations, but some extrinsic motivations, like giving rewards for completing actions, are unavoidable and not always bad. If you have an external goal that you identify with, you’ll feel motivated to complete tasks in order to fulfill said goal. That’s a good type of extrinsic motivation.

Self Determination Theory and Video Games

Scott Rigby and the people of Immersyve used SDT as a foundation for their own model: The Player Experience of Need Satisfaction (PENS). The team studied over 7,500 players and their motivations to continue a game for a prolonged period of time and found that PENS had a strong correlation with what compelled players to not only play a game for months and years on end but to identify as a [insert game name] player. I’m a DOTA player.

The basic needs as described by SDT can translate into gaming as such:

Competence

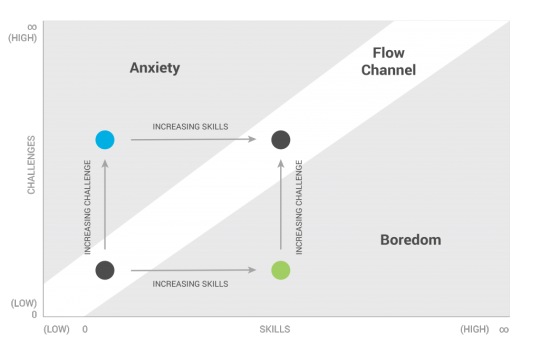

A game is easy to learn, but difficult to master. First Person Shooters and skill-based games like Super Meat Boy are big on competence need satisfaction.Rigby proposed that in order to satisfy competence, game designers should try to create the optimal level of challenge for the player. He refined this idea through Polish psychologist Csikszentmihalyi’s concept of “Flow” –– a psychological state where one is completely immersed in a task. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi defined “Flow” as:

“…the state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience itself is so enjoyable that people will do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it.”

According to Csikszentmihalyi, Flow happens when challenges are appropriately matched to one’s ability. If the task at hand is too simple, people will get bored and not experience Flow. If it’s too challenging, people will get anxious, frustrated, and similarly won’t reach the state of Flow.

Making adjustments to Csikszentmihalyi’s concept of Flow, Rigby believed focusing only on the optimal challenge wasn’t enough. Game designers should concentrate on creating a balanced mastery curve (or difficulty curve) for their games. The curve should be so that challenges presented are slowly more conquerable — because the player is getting better at the game — and provide gamers the possibility to express their mastery. While the optimal challenge was an important element, if the player doesn’t get a chance to progress and convey their mastery in action, then their competence need won’t be satisfied.

In line with player progression, whenever one expresses this mastery, they should receive clear and immediate feedback on their accomplishment. This dictates the importance of over the top animation and feedback design in the user experience.

Autonomy

A game that satisfies players’ needs for autonomy gives them choices, customization and agency. Role-playing games (RPGs) and massively multiplayer online games (MMOs) are usually great at satisfying the autonomy need by maximizing the player’s opportunities for action and giving them an entire open world to explore and character sheets to customize.

Choices that are forced upon us, like invisible walls in a game world, feel weird and are demotivating. Scott Rigby states that it isn’t exactly the act of — for instance — customizing your character that will satisfy autonomy, but rather coming back to your character later and having a feeling that “I created this and it’s awesome.” According to PENS, autonomy is particularly important for titles that achieve a perennial value for players, those that are played for years and define their players’ identities. In his research he found that first-person shooter (FPS) titles — more commonly known for creating competence need satisfaction — also satisfy the need for autonomy.

Relatedness

Satisfying the need for relatedness is possible through features such as social grouping and status feedback systems. MMOs and multiplayer online battle arenas (MOBAs) are big on relatedness need satisfaction because they provide a strong sense of belonging through parties and guilds. In these games, you’re always looking after your party and you are looked after by them.

Relatedness is commonly thought of as “the social need” and often, mistakenly, thought of as pertaining only to multiplayer titles. However, non-player characters (NPCs) can be a big driver of relatedness where, when scripted properly, players end up having an emotional connection to that character. Anyone who played Fallout 4 probably related to Dogmeat, the NPC dog that accompanies you in your travels through the wasteland.

Conclusion

By focusing on the three basic psychological needs that the SDT model proposes, game developers are creating psychological experiences that form the building blocks of fun and not only fun itself. According to the scientists at Immersyve, this is a preferable approach because fun is “only” the outcome of the experience and therefore an intangible construct.

As game designers and product managers we have to ask ourselves: Does this feature promote competence, autonomy, or relatedness? I found out the practical way (read: the hard way), that game mechanics and systems can either promote or, if not done properly, thwart these three basic needs.

Remember that you don’t have to design all three needs into every little microfeature of your game, but when you look at the macro of that feature — the overarching, big feature — it does have to address the three needs. Maybe a couple of micro-features will address relatedness and another five will have both a combination of competence and autonomy, but when you look at the big picture of the (to use scrum language) Epic feature all three needs should be well represented for that Epic to be successful in the long-term.

This framework helps answer how to keep players engaged and create long-term satisfaction, but does it also explain the motivation behind users’ install and purchase decisions? Why did players install your game to begin with? In part two of this series, we’ll dive into Jason Vandenberghe’s framework, the Domains of Play, and how it helps explain what drives users to install or purchase your game.

The post Leveraging Player Motivation Models to Increase App Engagement – Part 1 appeared first on Liftoff.

Leveraging Player Motivation Models to Increase App Engagement – Part 1 published first on https://leolarsonblog.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Video

youtube

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland is a weird and wonderful story, full of odd surreal encounters and wacky nonsense. Despite it's strangeness though, I promise that drugs were not involved in it's production.

To read all of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass as a PDF: http://www.gasl.org/refbib/Carroll__Alice_1st.pdf

Full text version of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/11/11-h/11-h.htm

Full text version of Through the Looking Glass: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/12/12-h/12-h.htm

Closed Captioning coming soon

Transcript below

Alice in Wonderland isn’t about drugs.

Now, I know that may come as a surprise to some people. It’s pretty standard internet fair to point at Alice, with all the trippy visuals and the mushrooms and the Hookah caterpillar, and declare that it was REALLY all about drugs this whole time, oh ho ho, and Disney made a movie about it!

But it’s not. It’s not about drugs.

I want to talk about Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass a little bit today, what they are really about, where this idea of them being about drugs came from, and why I find it to kind of be bullshit.

So, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is an 1865 novel written by English novelist Charles Lutwidge Dodgson under the pseudonym Lewis Carrol. The sequel, Through the Looking Glass, was published in 1871. I’m going to focus mainly on these two original books, and not the dozens and dozens and dozens of adaptations and remakes that exist. For the record, both books are in the public domain, so it's very easy to find pdf copies of them on the internet.

Almost every movie version of Alice, including the Disney one, splices together elements and plot points from both of the books, rather than simply adapting one story or the other. It’s not particularly important to know which characters and events happen in each, since they are very often published as a pair anyway. But we’re going to have a quick overview.

-

In Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Alice is a young girl who is in the garden of her home playing with her cat Dinah when she sees a white rabbit in a waistcoat run past, apparently late to an appointment. She follows the rabbit down the rabbit hole and thus into wonderland. What follows is a quintessential example of literary nonsense, filled with word play, puns, and absurdity as Alice works her way through Wonderland.

She eats an odd bite of cake and drinks a potion which change her size. She cries so hard she creates a sea. She recites some poetry she had to memorize for school buts gets it all wrong. She meets a mouse that won’t answer her call in English, so she tries talking to it in French. She wonders if this assumed French mouse came over with William the Conqueror, because Alice doesn’t know much about when things in history happened. They reach the shore where other animals are. The mouse then gives a lecture on william the conqueror and the animals agree to a Caucus race to dry off (Because Alice doesn’t know what a caucus actually is.)

Alice meets the Caterpillar, who seems to speak in riddles, correcting her grammar and not making sense. She meets the Duchess, who yells a lot and seems to ignore her baby. She meets the Cheshire Cat, who again, doesn’t make a lot of sense, and then the Mad Hatter and March Hare. More and more riddles. She plays a VERY silly game of croquet with the Queen of Hearts where the rules don’t make sense and the Queen cheats a lot. She meets a Mock Turtle (a pun on Mock Turtle soup, apparently Alice thought Mock Turtles were an animal). Then the world’s silliest court scene, where everything is unfair and doesn’t make sense, and then Alice goes back home, waking up as if from a dream.

Set presumably about half a year later, in Through the Looking Glass, Alice is playing inside the house with two cats, Dinah’s kittens, when she contemplates the mirror in the room. She finds that she is able to walk through the mirror and back into Wonderland. She discovers a mostly nonsense poem, Jabberwocky, which can only be read if you hold it up to a mirror. She also finds that the chess pieces in the room have come to life. What follows is another adventure in mostly absurdity, though if you know how, you can actually use Looking Glass as a step by step guide for a real chess game. Alice plays the part of one of the white pawns.

She wanders through the garden of living flowers, meets Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum, talks to Humpty Dumpty, and eventually makes all the way across the “board” and becomes a queen herself. The Red and White queens throw her a party, and then confuse her with riddles and wordplay. This actually results in Alice physically confronting the Red Queen and “Capturing her”, putting the Red King into “Checkmate” unintentionally, and thus, she wakes up in her arm chair back home having won the game.

Quick recommendation, if you want to get all of the little wordplay and puns and references in Alice and Looking Glass, I recommend the Annotated Alice by Martin Gardner. It’s awesome.

-

These books are pretty strange. So, if not a psychedelic reflection about a weird acid trip, or whatever, what’s up with these books? Why are they so weird?

Well, Carrol said he wrote the book after he and a friend spent a day on a river trip with the 3 young daughters of Henry Liddell in 1862. During their journey, Carrol entertained the girls with a made up nonsense story about a girl named Alice. Alice Liddell was so entranced that she told Carrol he should publish it. And so he did. He spent a few years refining the story before it was finally published, and the real Alice got her copy.

So on the surface, it’s just that- a silly story meant to amuse children, a celebration of imagination and childhood silliness.

But there are some underlying themes in these books. The encounters Alice has have a sort of pattern to them- Adults in the books, whether they are the Queen of Hearts or the White Queen, the Duchess or the Hatter, often speak in riddles. They make up rules that don’t make sense and refuse to explain them. The white rabbit is obsessed with never being late, and much of the word play or silliness comes from Alice not understanding adult or unfamiliar concepts (like the Mock Turtle or a Caucus race.)

And so the books become a very silly exploration of how a child, viewing the adult world, might feel confused and lost. Wonderland is Adulthood cloaked in familiar childhood clothes. Nursery Rhymes and game board pieces doing a fumbling pantomime of adulthood, discussing mathematical concepts and latin grammar, through the eyes of a child who doesn’t understand it.

There are many things that can be pulled from Alice- ideas of innocence, of escapism, of identity and sense of self, of intentionally bucking order in favor of disorder. But none of those things are drugs.

(Sidenote: There is a whole other issue about Carrol’s….relationship with the Liddell daughters, and his...fondness for young girls in general. This is a whole separate debate, and it gets kinda messy with contemporary views of childhood and adulthood and whether there was anything...untoward about his fondness for them. But that’s really not what we’re talking about today. )

-

So, why do people think this is a story about drugs? Carrol wasn’t known for opium use, or even heavy drinking. He had no exposure to psychedelics (magic mushrooms wouldn't be discovered by Europeans until 1955) So why?

I think the easiest answer is that people want stories to make sense. I want stories to make sense. I spent a lot of money going to college to get a degree in “Making stories make sense.” We want there to be a reason that things happen in stories, and so when a story feels as random and silly and surreal as Alice, we want to figure out what it’s REALLY about.

This is kind of the underlying idea behind surrealism in general- creating art and meaning out of the absurd and random images of dreams and unreality. [Side note, there is an edition of Alice with illustrations by Salvador Dali, which is...amazing.]

And thanks to the culture of the 1960s and 1970s, there is a heavy association between reality-bending images and drug use, especially hallucinogens. And depending on which adaptation you are looking at, some movies really play up this trippy psychedelic aesthetic for Alice.

But I think there’s another level to this one, and one that I find much more grating. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is a story for children, especially for girls. And there is a certain segment of the population, especially among young adults on the internet, who really seem to enjoy taking things aimed at children and declaring NO, this thing isn’t for kids, it’s actually FOR ME, and slapping an edgy dark interpretation on top of it, however sloppily.

Fan theories like...Ash is in a coma all along, or all the Rugrats are dead and Angelica is just imagining them, and...yeah, a huge slice of the Brony fandom declaring that adult men are the real audience, they aim at appropriating and co-opting child media for adult consumption

And there’s something about that which leaves a sour taste in my mouth over all.

-

I don’t think there’s anything inherently bad about reimagining child stories in more adult ways. But I do think it somewhat misses the point when people begin to insist that these mature reimaginings are the CORRECT or more valid interpretation, especially if they lead to the exclusion of children from that media space.

With Alice in particular, I think the story gives adult readers a chance to empathize with children, not as dolls or objects of cuteness, but as people interacting with a confusing and strange world as they grow up. It is an opportunity to revisit childhood, with all it’s familiar characters and uncertainty and wonder, and rather than corrupt that story, I think it should be embraced.

I’m going to leave you with the end of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Alice’s adult sister, having heard her story, lays back, and herself begins to dream, of Wonderland and of her sister Alice. And This is what it says, “Lastly, she pictured to herself how this same little sister of hers would, in the after-time, be herself a grown woman; and how she would keep, through all her riper years, the simple and loving heart of her childhood: and how she would gather about her other little children, and make their eyes bright and eager with many a strange tale, perhaps even with the dream of Wonderland of long ago: and how she would feel with all their simple sorrows, and find a pleasure in all their simple joys, remembering her own child-life, and the happy summer days.”

And that is what Wonderland is about.

Thanks for watching this video! I’ll see yall down in the comments, so if you have any questions, feedback, or suggestions, head on over. If you enjoyed listening to this queer millennial feminist with a BA in English ramble on for a while, feel free to subscribe.

431 notes

·

View notes