#im just sick of anyone who ever says they like deh following it up with an ‘even though it sucks’

Text

i will never justify why i like deh bc i don’t have to actually. i can just like it no qualifier needed

#this is inspired by a post but by no means a direct response#im just sick of anyone who ever says they like deh following it up with an ‘even though it sucks’#u can just say u like it#also it doesn’t suck okay it’s not problematic bc that doesn’t#doesn’t mean anything#the story isn’t trying to tell people to lie about knowing dead kids it’s not a moral lesson#the music slaps#have ur issues with it whatever but stawp with the shame#no media is without flaws#deh is not objectively bad as much as people want to believe that#honestly no one gets to clown on deh when dark romance is insanely popular on tiktok#by which I mean clearly we can understand that media doesn’t have to reflect real life morals#it doesn’t have to be pure and clean#im literally so cold rn#that’s unrelated#let people enjoy deh guilt free#let the tiktok girlies enjoy mafia stalker fiction#live and let live!#do i main tag this#dear evan hansen#deh#dear evan hansen (2021)

106 notes

·

View notes

Photo

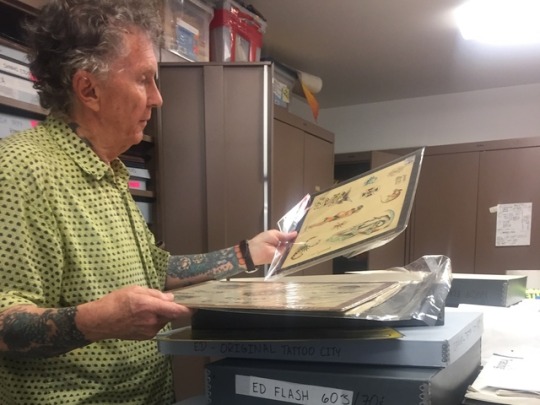

Don Ed Hardy on The Evolution of Tattooing

SFAI’s Alumni Exhibition, In A Flash, is opening this month and the illustrious tattoo artist and SFAI Alum Don Ed Hardy (BFA 1967) has agreed to participate! Last week SFAI’s Exhibitions Manager, Kat Trataris, and Librarian, Jeff Gunderson, headed to Hardy’s North Beach studio to talk Flash and select works for the show. (Im)Material tagged along, and we were lucky enough to get a real education in the history of tattooing in the West from one of the original masters of custom tattoo art in the United States.

After exploring decades of highly organized early flash and custom designs, Hardy settled in among a tidy spread of artwork, books, and CDs to answer a few questions for (Im)Material. Read the interview below, and don’t forget to come see In A Flash at SFAI’s Diego Rivera Gallery, opening at 5pm on July 4!

SFAI: Thank you so much for agreeing to do this!

Don Ed Hardy: It’s no problem. How’s this?

SFAI: This is perfect. Alright, so my first question is, How would you say that tattooing has evolved since you first got started?

DEH: It’s... it’s reached the potential that I think it always had. I got into it because I believed in it and it was my destiny and I just… I was obsessed with it. When I was a little kid I was like ten years old and I started drawing tattoos and I was drawing on people. And when I was getting ready to finish my undergraduate degree and was set to go to graduate school in Printmaking and probably teach and I reconnected with tattooing. And I met a guy that was another, the first—my favorite term—“renegate intellectual” that had been in tattooing. He was a published author, really intelligent guy and good tattooer, and the first day in his shop he showed me a book of Japanese tattoos.

Actually Donald Richie, he was the one who brought Japanese cinema to the west in the late 1940s, he along with a lot of conscientious objectors/pacifist people worked on merchant marine ships so that they had joined the military. He got to Japan and he fell in love with it there. He was a closeted guy and in Japan you could—especially in those days you could function as a gay person I think easier than you could in America. There’s a great tradition of it there, you know a different outlook of gender. So anyway, Donald was one of the people who brought Japanese cinema to the west because he went over there in the occupation forces after Japan lost the war and fell in love with the country and then became obsessed with the cinema, became fluent in Japanese and then he really brought that whole culture to the awareness of Western people. And he was fascinated with the whole tattoo thing and he had written a book about tattooing in Japan with photos of contemporary tattoo artists in the 60s.

So this guy Phil Sparrow that I met who was working in Oakland showed me that book that first day in his shop and when I saw it—because I was teetering and I was supposed to go to Yale and I was going to teach printmaking and you know, do that—and when I saw that I just immediately thought, if you can make tattoos look like that, you can...I can make, you can make them into anything. And I just abruptly decided I was going to take up tattooing. I thought it had great potential as just human expression. And I knew it was way deeper and way beyond people’s perceptions, you know. When I was younger when you had a tattoo it was like, “well were you drunk or were you in the military?”—it was like those two things, otherwise, why would you ever have one of these things? And mark yourself? And I just thought it was better to see if we could develop this as a medium. So that’s what I did. Obviously, you know I had to meet a lot of influential people and a lot of great artists and get their confidence and, you know, just open it up in the West. Mind you I just hated the fact that you couldn’t have a tattoo without it having that reputation, it just didn’t seem right. It was sort of the last thing in the liberation of… being able to live your own life.

Don Ed Hardy answering our questions in his studio.

SFAI: Why do you think tattooing got that reputation? And how do you think it got away from it?

DEH: I think it got that reputation basically because of the suffocating judeo-christian power structure that ran everything in the world. You know, shame and this is wrong and you shouldn’t mark this body that God gave you and all this bullshit — I mean I was force-marched through, you know, Christianity as a kid. My mother meant well but I wasn’t meant for it — and I think it was just looked down on. They thought it was like this savage, barbaric thing. But it really flowered in the West, which we’re going to talk about tomorrow—are you coming to that thing at the Asian Museum?

Jeff Gunderson: I’m hoping to, yeah...

DEH: Because it’s gonna be really a really good panel. We’re gonna get there early enough to see the show. It’s a show of ukiyo-e wood block prints on loan from the Boston Museum which is a fantastic collection of asian art from all the cutters and they’ve loaned all these really pristine prints that feature people in the mid-19th century. I think Japan got opened up maybe early 1860s/late 1850s and then people started going in there and seeing it and some of the things they saw were, you know, tattoos on all of these people. And there was no kind of [western] tradition of it then it was just with whalers and just seafaring types and they just had these spot tattoos, but in Japan it was a really highly developed art form. So... that had a big impact and that followed through to the 20th century. Some of the tattooists, the few tattooists who were really interested in and capable of doing unique work and had inherent art talent wanted to expand it and were trying to offer people more than just, you know, the recipe of imagery and sentiments and stuff that existed in American Flash.

Among them was Sailor Jerry in Honolulu who was one of my primary mentors. He’d been tattooing a long time, since the, probably the 30s, but in the 60s he really got known for doing these large Japanese-inspired designs but with subject matter and more polychromatic treatment and… you know, he opened up the field as far as the kind of things you could do with the machines. But that’s when it started really was the 60s there were a few people that were pretty interested in that.

I was able to go to Japan and work with a tattoo master and when I came back here I opened up the first private studio and the whole deal was to get—I would only do absolutely unique tattoos. So people would come in with their concepts and I could draw, so I could draw the concept, and that’s what started it more. And I began to get tattooers from all over the world as clients and they saw what I was doing and thought “well maybe I have the interest and the drawing ability to do that myself,” so that just kind of put the ripples right out.

JG: I’m always interested in that History of Tattooing lecture you gave in Richard Shaw’s class at the Art Institute.

SFAI: On that note, how would you say your experience at SFAI impacted your art career and art practice?

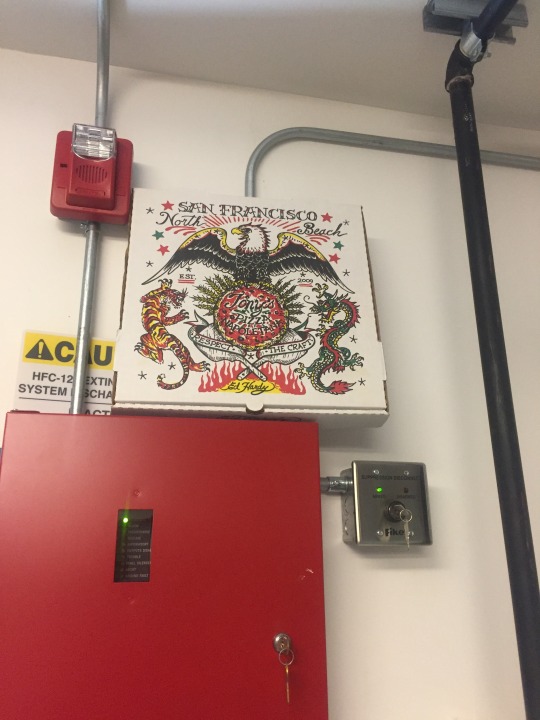

Drawing on a pizza box spotted in Ed Hardy’s studio.

DEH: The experience was really good there because of the openness of it but the key thing really was the instructors I got to have which primarily were Joan Brown and Gordon Cook and… some other people I can’t remember some of their names but um… But the openness of it and of course just the setup of the school you know, because I was raised in this totally right-wing Orange County town in Southern California and the first time I came up with a buddy and we flew—I think it was the first time we’d flown as conscious adults—BANG we came up (it was like 11 bucks for a one way ticket) and we came up for the weekend because Richard Shaw and Martha Hall, who became his wife, and another guy had come up, Reggie Daniker. And they’d come up from Orange County. And I just couldn’t believe it, it was like… the city, the whole thing… I was very aware of beat culture and, you know, I was pretty well-steeped in alternative consciousnesses as had been exhibited earlier in the century. Anyway, I was here and I was like, “Oh I’ve found mecca!” And the school, even the setup of it was fantastic. But really, I think the people that affected me the most were really the people who didn’t teach here that long and they were able to just get away with their take on the whatever the current… I mean, maybe the primary intent of the school is to have different voices and so it was good for that. It was definitely good for that.

And then I was on a career track and working in the library and it was going well and I figured I was going to go to grad school because I was accepted to Yale. In those days you either figured out the… the question we always posed ourselves was: Would it be better… if we want to keep making our personal art, would it be better to have a job that doesn’t involve art at all and then do your art, or is it okay if you’re connected, teaching or doing something, is that going to leach away your energy that you would otherwise put into your personal work. You know, it’s all a psycho-drama and anyone that’s cursed with like a, you know, an “intention to make art” you’re like, how will I do this and make it fit into your life. Not even as a financial thing, just as a thing that… so you can live with yourself. So… and for me it really worked out well that I chose the tattoo thing. I’m so glad I did… because right then too the primary flavors that were popular in the world not only were the economic thing about art as a big money commodity which was sick enough in the 1960s now it’s through the roof, but the fact that you could be made totally independent of the institution. That’s what I was after. My buddy Mike Malone, who was from here too—he became a tattooer, he was a fine artist—and he basically just summed it up, he said,

“We joined the pirates. We just decided we’re not going to be part of any kind of groups. We’re just… we’re gonna try this.”

... Which in those days... it was very transgressive.

But yeah, I’m glad to see that tattooing has gotten popular. I mean, I didn’t try to proselytize it but for people that try to get them now there are all these incredibly talented tattooers with great careers and they’re free agents and they just go around the world and tattoo and they have people… they’re appreciated. It’s really, it’s great to have—it’s beyond anything we could have dreamed of. It’s very cool. I’m stoked that the museum is—or the school gonna do a show there. It’s natural ... it was a nice surprise to hear. There are probably way more people that I know that I didn’t realize existed that became tattoo artists that came out of there, so… it’s good! It’s a good career. It can be a positive career option. I’m glad I didn’t have to get into it today with the competition, I never would have been able to do it.

Don’t miss Don Ed Hardy’s work on view in In A Flash opening July 4 in SFAI’s Diego Rivera Gallery!

0 notes