#illiterate britain

Text

Arthur, the Wizard-king

Since King Arthur is a bard (albeit a frivolous one) in Welsh Myth, that technically means Arthur is a magician in some capacity.

Bards/Poets in Celtic Culture and Myth are combo of newscaster, historian, genealogist, prophet and entertainer. They are essentially lore keepers - Walking libraries for a mostly illiterate society. Which is why they are placed in an esteemed social status. They not only entertain but can prophesize the future, rouse one's companions to action and curse people with satires, on top of preserving knowledge through poetic forms.

Taliesin and Myrddin Wyllt are examples of from welsh lore. In Irish myth, there's Laidcenn, Niall (of the nine hostages)'s poet, and I remember some poet-warrior threatened to lampoon Cu Chulainn.

I think evidence that points to Arthur's magic is in the story Gwyn, Gwythyr and Creiddylad:

If you interpret Gwyn and Gwythyr as mortal men, Arthur magically oath-bound two men to fight each other until judgement day, granting them immortality in the process.

If you interpret Gwyn and Gwythyr are divine beings, then Arthur cursed two gods to fight each other annually and organized the seasons.

No matter how you cut it, Arthur is pretty magically strong. Other magical facts about Arthur include:

Welsh Triads saying Arthur had the ability to render the land infertile for seven years wherever he walks.

Arthur having an invisibility cloak, like Harry Potter. It was called "Gwenn", apparently.

Oral Folklore that says that Arthur can shapeshift into a raven or chough. Which is why it's bad luck to kill one.

Uther, Arthur's dad, being the creator of one of the "Three great enchantments of Britain", which was then taught to Menw ap Teirgwaedd, an enchanter knight of Arthur's. In his death-song, Uther even boasts about being a "great enchanter". (unless I'm mistaken)

#uther pendragon#king arthur#gwyn ap nudd#gwythyr ap greidawl#creiddylad#arthuriana#arthurian legend#arthurian legends#arthurian mythology#welsh triads#welsh mythology#celtic mythology#menw ap teirgwaedd#bardism

62 notes

·

View notes

Note

nothing pisses me off like brits pretending they get to complain about "american centrism". american centrism exists because the US is the current imperial core, which is because the root of imperialism and its first core, england, made it its pet project. criticism of and resistance to american centrism is a subset of resistance against imperialism. for british "people" to pretend they can be lumped in with all Non USA Countries as if the US's treatment of britain is in literally any way comparable with namibia or even other european countries like croatia is fucking absurd and just the kind of imperialist appropriation of the struggle of oppressed peoples that you'd expect from their worthless people. this isn't to say the US can't be criticized on its own(it can) or that it doesn't have significantly more political power than britain now(it does). it's just to say that the only people more politically illiterate, cruel, ignorant, bigoted and sheltered than the US are the british. britain deserve the same fate as the US-- to be dissolved and given back to its rightful owners. long live ireland long live scotland and long live wales, short live the king i hope that fuck falls down a long flight of stairs into a sewer and drowns tomorrow.

255 notes

·

View notes

Text

coastalcurmudgeon asked: Hi, would you mind pointing me towards any articles, books, video essays etc that make reasonable modern pro-monarchist arguments? When queen Elizabeth passed a few months ago it got me wondering why not just the British but several other wealthy democratic nations hang on to their monarchs. I'm from the US so it's a little difficult to understand the monarchies perspective off the bat and you seemed a good person to ask about where to find good arguments for it. Thanks and have a nice day

I want to thank you for asking such a simple question but one that many of us don’t really give a thought to. We get sucked into the tittle tattle of court intrigue or the tawdry gossip of the latest royal scandal made public, partly because it’s a visceral pleasure to see those above us squirm in discomfort, and partly to see them bleed - perhaps to remind us that they are as mortal and as fallen as we all are.

In the wake of Queen Elizabeth II’s death, the question of monarchy is brought sharply into focus. The sombre and reflective tone of the tributes to the late Queen Elizabeth II suggests the esteem in which she was held, as well as the apparent popularity of Britain’s constitutional monarchy. But it was not always so, as the queen herself was fully aware. She might have remained more or less beyond reproach, but her family-members have not. Often the Windsors seemed like a bad soap opera, attracting derision and resentment in equal measure. Yet, like their ancestors, they have slogged on regardless. Other monarchies have been toppled, or cut down to size, all over Europe and beyond.

We focus on the institution and its rituals and trappings without asking the underlying question of why? Why do we believe in the institution? It’s a question that even ardent monarchists find hard to answer properly.

The hard leftists of course do know why they want to get rid of a monarchy in the name of some vague and unrealised ideal of equality and freedom from tyranny as well in the name of democracy. They do so out of historical ignorance given that the constitutional monarchy does exactly that and has been paradoxically a guarantor of these ideals through custom, heritage, and the rule of common law. For them it’s better to destroy than it is to build as Roger Scruton once said. Being historically illiterate, they don’t fully understand the folly on pulling one thread runs the danger pulling the entire tapestry of a nation apart.

I don’t want to caricature all them with one brush because not all leftists believe in the destruction of the monarchy in Britain. Some understand its value and even harmonise it within their leftist beliefs.

Stephen Fry, a socialist in his political beliefs but still widely considered (and righty so) as a national treasure, came out in his support of the monarchy in Britain. The beloved British actor, writer and presenter admitted in a podcast with Jordan Peterson that the Royal Family in interviews that “on the face of it is of course preposterous”. But he went on to explain how they can play a key role in society. The author referred to the Queen’s weekly Audience with the Prime Minister and suggested that the US could benefit from having a Monarch. He explained how his thoughts stemmed from his belief in “ceremony, ritual and symbolism”.

Fry told the podcast: “I look at America and I think if only Donald Trump and now Biden, if every week they had to walk up the hill and go into a mansion in Washington and there was uncle Sam in a top hat and striped trousers.” He explained how “uncle Sam” might be the US equivalent of a Monarch and described him as “a living embodiment of their nation”.

Stephen Fry added: “More important than they were that’s the key. He [uncle Sam] is America, the President is a fly-by-night politician voted for by less than half the population and he has to bow in front of this personification of his country every week. And that personification, uncle Sam can’t tell him what to do, uncle Sam can’t say ‘pass this Act and don’t pass that Act and free these people, give them a pardon’. All he can do is say ‘tell me young fella what you done this week’ and he’ll bow and say ‘well uncle Sam’.”

He suggested how uncle Sam might reply “oh you think that’s the right thing for my country”. Fry concluded: “Well that’s what a constitutional monarchy is and of course it’s absurd but the fact that Churchill and Thatcher and everyone had to bow every week in front of this something.”

The author went on to claim that “empirically look at the happiest countries in the world that’s all you need do and they happen to be constitutional monarchies”. Fry finished up by listing Norway, Sweden, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Japan as some of those "happiest" places who have monarchies.: “They’re always right up there on the list. Now it may be that we can’t find the causal link between the constitutional monarchy but it might just be something to do with that.”

I happen to think Stephen Fry is right. For these reasons yes, but there are much better ones too.

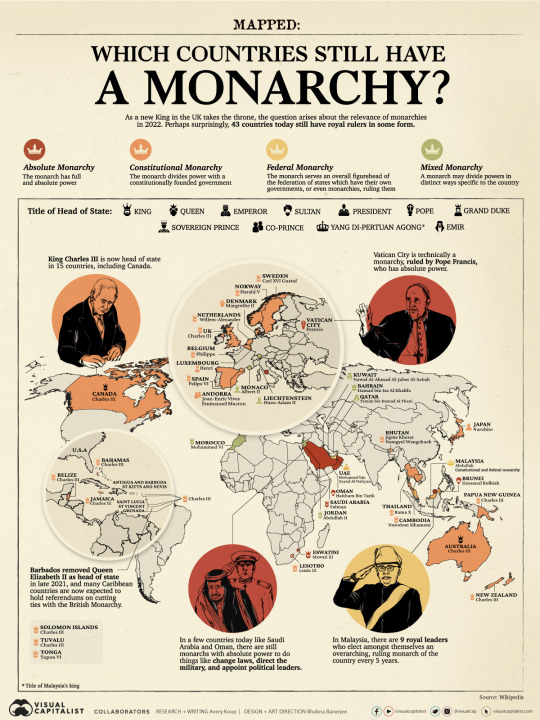

It’s first worth stating it helps to understand what kind of monarchy are we talking about? A surprising number of countries have ruling monarchs but not the same role or power. It’s important to break down the distinctions between the types of monarchies that exist today. Generally, there are four kinds.

In the constitutional monarchy, the monarch divides power with a constitutionally founded government. In this situation, the monarch, while having ceremonial duties and certain responsibilities, does not have any political power. For example, the UK’s monarch must sign all laws to make them official, but has no power to change or reject new laws. Example of countries that follow this are United Kingdom, Japan, and Denmark.

In the absolutist monarchy the monarch has full and absolute political power. They can amend, reject, or create laws, represent the country’s interests abroad, appoint political leaders, and so on. Such countries Said Arabia and Eswatini and even arguably the Vatican (the Papal office is like an absolutist monarch but of the church).

In the federal monarchy the monarch serves an overall figurehead of the federation of states which have their own governments, or even monarchies, ruling them. These countries include UAE and Malaysia.

In the mixed monarchy there is an unusual situation wherein an absolute monarch may divide powers in distinct ways specific to the country. Here Jordan, Liechtenstein, and Morocco are stand out examples.

To many contemporary critics and political progressives, monarchies seem to be purposeless antiquated relics, anachronisms that ought to eventually give way to republics.

On the contrary, nothing can be farther from the truth. Monarchies have an extremely valuable role to play, even in the 21st century and beyond. If anything their number should be added to rather than subtracted from. To understand why, it is important to consider the merits of monarchy objectively without resorting to the tautology that countries ought to be democracies because they ought to be democracies.

There are several advantages in having a monarchy in the 21st century. First, monarchs can rise above politics in the way an elected head of state cannot. Monarchs represent the whole country in a way democratically elected leaders cannot and do not. The choice for the highest political position in a monarchy cannot be influenced by and in a sense beholden to money, the media, or a political party.

Secondly and closely related to the previous point is that in factitious countries like Thailand, the existence of a monarch is often the only thing holding the country back from the edge of civil war. Monarchs are especially important in multiethnic countries such as Belgium because the institution of monarchy unites diverse and often hostile ethnic groups under shared loyalty to the monarch instead of to an ethnic or tribal group. The Habsburg dynasty held together a large, prosperous country that quickly balkanised into almost a dozen states of no power without it. If the restoration of the erstwhile king of Afghanistan, Zahir Shah, widely respected by all Afghans, went through after the overthrow of the Taliban in 2001, perhaps Afghanistan would have more quickly risen above the factionalism and rivalry between various warlords.

Third, monarchies prevent the emergence of extreme forms of government in their countries by fixing the form of government. All political leaders must serve as prime ministers or ministers of the ruler. Even if actual power lies with these individuals, the existence of a monarch makes it difficult to radically or totally alter a country’s politics. The presence of kings in Cambodia, Jordan, and Morocco holds back the worst and more extreme tendencies of political leaders or factions in their countries. Monarchy also stabilises countries by encouraging slow, incremental change instead of extreme swings in the nature of regimes. The monarchies of the Arab states have established much more stable societies than non-monarchic Arab states, many of which have gone through such seismic shifts over the course of the Arab Spring.

Fourth, monarchies have the gravitas and prestige to make last-resort, hard, and necessary decisions - decisions that nobody else can make. For example, Juan Carlos of Spain - now in disgrace but not in the beginning of his reign - personally ensured his country’s transition to a constitutional monarchy with parliamentary institutions and stood down an attempted military coup. At the end of the Second World War, the Japanese Emperor Hirohito defied his military’s wish to fight on and saved countless of his people’s lives by advocating for Japan’s surrender.

Fifth, monarchies are repositories of tradition and continuity in ever changing times. They remind a country of what it represents and where it came from, facts that can often be forgotten in the swiftly changing currents of politics.

Finally, rather counterintuitively, monarchies can serve up a head of state in a more democratic and diverse way than actual democratic politics. Since anyone, regardless of their personality or interests, can by accident of birth become a monarch, all types of people may become rulers in such a system. The head of state may thus promote causes or stir interest in issues and topics that would otherwise not be significant, as King Charles’ views on architecture and climate change proved. Politicians on the other hand, tend to have a certain personality - they are generally extroverted, can make or raise money, and have a tendency to pander or at least publicly hold to pre-defined mainstream views. The presence of a head of state with a psychological profile different from a politician can be refreshing.

Most of the criticisms of monarchy are no longer valid today, if they were ever valid. These criticisms are usually some variation of two ideas. Firstly, the monarch may wield absolute power arbitrarily without any sort of check, thus ruling as a tyrant. However, in present era, most monarchies rule within some sort of constitutional or traditional framework which constrains and institutionalises their powers. Even prior to this, monarchs faced significant constraints from various groups including religious institutions, aristocracies, the wealthy, and even commoners. Customs, which always shape social interactions, also served to restrain. Even monarchies that were absolute in theory were almost always constrained in practice.

A second criticism is that even a good monarch may have an unworthy successor. However, today’s heirs are educated from birth for their future role and live in the full glare of the media their entire lives. This constrains bad behaviour. More importantly, because they have literally been born to rule, they have constant, hands-on training on how to interact with people, politicians, and the media.

In light of the all the advantages of monarchy, it is clear why many citizens of democracies today have an understandable nostalgia for monarchy. As in previous centuries, monarchy will continue to show itself to be an important and beneficial political institution wherever it still survives.

Constitutional monarchies are undoubtedly the most popular form of royal leadership in the modern era, making up close to 70% of all monarchies. This situation allows for democratically elected governments to rule the country, while the monarch performs ceremonial duties. Most monarchs are hereditary, inheriting their position by luck of their birth, but interestingly, the French president, Emmanuel Macron, technically serves as a Co-Prince of Andorra - a fact I enjoy making my good French republican friends squirm in discomfort. But France remains resolutely a republic despite many other European countries being a constitutional monarchy.

Monarchy has a long history in Europe, being the predominant form of government from the Middle Ages until the First World War. At the turn of the twentieth century every country in Europe was a monarchy with just three exceptions: France, Switzerland and San Marino. But by the start of the twenty-first century, most European countries had ceased to be monarchies, and three quarters of the member states of the European Union are now republics. That has led to a teleological assumption that in time most advanced democracies will become republics, as the highest form of democratic government.

But there still remains a stubborn group of countries in Western Europe which defy that assumption, and they include some of the most advanced democracies in the world. In the most recent Democracy Index compiled by the Economist Intelligence Unit, six out of the top ten democracies - and nine of the top 15 - in the world were monarchies. They include six European monarchies: Norway, Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and the UK.

It remains a historical paradox. These monarchies have survived partly for geopolitical reasons, most of the other European monarchies having disappeared at the end of the First or Second World Wars. Their continuance has been accompanied by a steady diminution in their political power, which has shrunk almost to zero, and developing roles that support liberal democracy. What modern monarchies offer is non-partisan state headship set apart from the daily political struggle of executive government; the continuity of a family whose different generations attract the interest of all age groups; and disinterested support for civil society that is beyond the reach of partisan politics. These roles have evolved because monarchy depends ultimately on the support of the public, and is more accountable than people might think.

Understanding this paradox of an ancient hereditary institution surviving as a central part of modern democracies is a key part of understanding why monarchies persist and will continue to exist.

I’m going to confine answering your question to constitutional monarchy because it’s what the United Kingdom and the rest of Europe is. This is partly to narrow the wide question to something more manageable but also reflective of the fact that each country is different with its own unique history of customs, traditions, and heritage, and practices of governance, that make up the unique quality of the monarchy in question.

I’m just going to give you a general recommendation list rather than a deep academic dive into political theory. But then theory is no good without practice. History is the best place to start to understand some of the things I’ve already highlighted.

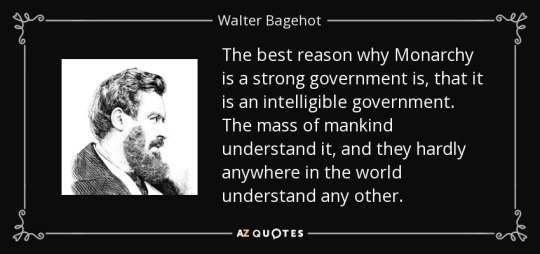

1. The English Constitution by Walter Bagehot

I know I said to start with history and here I’m recommending you begin with reading a book on constitutional theory and practice. But hear me out.

First published in 1867, this remains the indispensable guide to the role and purpose of the British sovereign. The text by Walter Bagehot (who was editor of The Economist for 17 years) is often mistaken for an official account of constitutional monarchy. In fact, it is a lively argument on how Britain’s old institutions should cope with the coming of mass-democracy. It was in this spirit that Bagehot contrasted the “dignified” parts of the constitution - the monarchy and the House of Lords - with the merely “efficient”, the Cabinet, MPs and the like. In the new age of mass-politics, he considered that the role of the monarchy was to “excite and preserve the reverence of the population” for the country’s institutions and government. Although monarchs might not have executive power anymore, they maintained three rights over “efficient” politicians - “to be consulted, to encourage and to warn”.

That the British monarchy survived while many of Europe’s were overthrown is in no small measure to the Windsors’ scrupulousness in following Bagehot’s advice. And, prophetically, he cautioned that the whole royal conjuring trick could only work if its dignity was preserved: “If you begin to poke about it, you cannot reverence it…its mystery is its life. We must not let in daylight upon the magic.”

The great thing is you don’t even have to buy it. Free copies exist online to download. I have my own copy because it really is a sort of bible for me when I have to think soberly and stay grounded as the latest royal scandal erupts and everyone is losing their heads.

2. Crown and Country: A history of England through the Monarchy by David Starkey (2010)

David Starkey is one of Britain’s finest medieval historians and fine prose stylist. A Cambridge historian whose lectures I used to sneak off to listen to - I did Classics - because the man was so charismatic, provocative, and damn clever. From one of our finest historians comes an outstanding exploration of the British monarchy, from the retreat of the Romans up until the modern day.

Crown and Country is a spin off from his TV series on the same subject. However the book is a great introduction to monarchy in Britain. In it he provides the reader with enough intellectual rigour to impart context, before livening the page with pithy tales of treachery or cruelty, of double-dealing or disaster. His delight at their shock value is tangible as he takes us from England's earliest status, as a barbarous outpost of the Roman empire, through to a rather uncomfortable attempt to second-guess how history will one day judge the contemporary members of the Windsor family (going up to the marriage of William and Kate).

Academic historians often complain that Starkey writes with the snappy zest of an unrepentant telly-don, but I doubt anybody else minds very much. He has a lovely eye for a good story – William the Conqueror being so fat that he could not fit in his sarcophagus, so that “the swollen bowels burst and an intolerable stench assailed the nostrils of the bystanders”, for example, or Henry II having such a tantrum that he fell out of bed and “threshed around the floor, cramming his mouth with the stuffing of his mattress”.

He also has a nice line in snarky humour. Academics have recently been trying to rehabilitate King John as a good administrator, he notes, but to praise him “for being a royal filing clerk shows historians looking after their own with a vengeance”.

Starkey’s great skill is to weave big themes quietly into a rollicking narrative, so that you absorb them almost without noticing they are there.

From the beginning, he argues, England’s monarchy has been unlike any other, divorced from imperial Roman traditions and based on an unspoken contract between king and people, and so reflecting a deep sense of patriotic exceptionalism. From Alfred, who effectively invented the idea of an English nation, to George III, who became the incarnation of bluff, beef-eating John Bull during the Napoleonic Wars, and on to George VI, the personification of quiet determination during Britain’s darkest and finest hours, successful kings have come to embody a wider spirit of national defiance. Perhaps that explains why, for all his faults, we remain fascinated with Henry VIII: he may have been a monster, but he was proudly, unapologetically, our monster.

Since it is evidently raw power that turns Starkey on, perhaps it is not surprising that once we are past the Glorious Revolution and the rule of dour, cunning, competent William of Orange, his narrative begins to flag. The House of Hanover, he says, was a “national joke” and although he clearly relishes the amorous misadventures of George IV and Edward VII, he spends barely 20 pages on the House of Windsor.

Compared with the blood-soaked warrior kings of his opening chapters, our recent monarchs have been personally colourless and politically irrelevant. But Starkey is not ready to give up on the monarchy. Just like his forebears, he points out, the current Prince of Wales has become the symbol of something bigger than himself, the cause of the environment and the spirit of voluntary service.

Nobody else could have set up such a vast empire of charitable endeavour: “Only he has the necessary combination of social and economic power and imagination to pull it off.” And here, Starkey argues, lies a formula for survival: “A new kingdom of the mind, spirit, culture and values,” which would appeal even to Oliver Cromwell.

Starkey is particularly good at explaining the shifting tone of monarchical power. After the straightforward Anglo-Saxon model, English kings had to incorporate the Norman way of doing things, with its "chivalric virus"; we then see the Tudors appear with their imperialist vision, followed by the disastrous Stuart belief in the divine right of kings, which James I subscribed to intellectually, and which Charles I paid for with his head. After that we see Hanoverian mediocrity, followed by Victorian pomp, and Windsor flexibility – changing nationality and name as wars with Germany, their ancestral home, demanded.

Crown & Country is a masterpiece of accessible history, underscored with profound scholarship: it takes the essential structure of hereditary monarchy, chronicles the struggles and triumphs of a rich panoply of carefully crafted characters and lays out the story of a nation. Above all, the author's passion for his subject, the royal tale of England, which is the backbone of this nation's story, explodes from every page. I defy anybody not to enjoy this book.

3. Blood Royal: Dynastic Politics in Medieval Europe by Robert Bartlett (2020)

Throughout medieval Europe, for hundreds of years, monarchy was the way that politics worked in most countries. This meant power was in the hands of a family - a dynasty; that politics was family politics; and political life was shaped by the births, marriages and deaths of the ruling family. How did the dynastic system cope with female rule, or pretenders to the throne? How did dynasties use names, the numbering of rulers and the visual display of heraldry to express their identity? And why did some royal families survive and thrive, while others did not? Robert Bartlett’s engaging Blood Royal tries to answer these questions by focusing on both the role of family dynamics and family consciousness in the politics of medieval European monarchical systems circa 500 to 1500 CE.

He creates an authoritative historical survey of dynastic power in Latin Christendom in western and central Europe and the Byzantine Empire (or former Eastern Roman Empire), providing an impressive level of depth while putting aspects of royalty and kingship in perspective. Each chapter brings the reader into this political world and aspects of medieval politics’ ties to family politics. Bartlett transitions seamlessly from example to example, but this apparent ease and vast knowledge reflects years of research and underscores his area expertise.

Blood Royal is an excellent book for anyone who has ever had a question about medieval European monarchy. If you’ve ever wondered how medieval marriages worked, the politics of dynastic succession, or even something as simple as what happened when the current monarch died then Bartlett’s book probably has an answer for you. Blood Royal is split into two sections, the first focusing on the specific lives of medieval royals, with chapters on medieval marriage, children, paternal relationships, as well as female rulers and mistresses. The second section covers dynasties rather than individuals. It is in this latter section that you’ll find discussions of names and numbers, pretenders, as well as heraldry and even the role of prophecy and astrology in medieval dynastic politics.

The scope of Blood Royal is immense. Bartlett includes early medieval dynasties like the Merovingians and Carolingians alongside later examples like the Plantagenets and the Hohenstaufen. Bartlett also incorporates an impressive range of dynasties from across medieval Europe, not limiting himself to just the French, English, and German royal families. Overall, it makes for a very impressive piece of scholarship from a senior historian, but one that is written in a very approachable and engaging fashion. The breadth of the coverage means that no matter where your interest in medieval Europe lies there’s probably something relevant to it in Blood Royal.

4. On Power: The Natural History of Its Growth by Bertrand De Jouvenel (1945)

Bertrand de Jouvenal is one of the most under-read political theorists in Europe today and it’s only in the last couple of decades his works have been translated into English. He wrote two seminal books pertinent to the state and how politics and monarchy mixed. I would thoroughly recommend his book ‘Sovereignty’ (1957) in that regard. How he treats sovereignty is clear and insightful and better than any academic I know. He describes how sovereignty in the modern sense can be traced back to the eleventh century, when absolutism was developed under such rulers as Philip the Fair. Before absolutism, it was acknowledged that every man had his seigniory, the king just as much as a simple farmer. The seigniory of the king was far greater, of course, but only as inviolable as that of every other person (as exemplified in the anecdote of Frederick the Great and the miller). The idea of a sovereignty that flows down from the sovereign to all his subjects was taken from the ancient Romans, and formed the basis of absolutism. One consequence of this was that democracy as we know it became possible in the first place. Before absolutism, there simply was no sovereignty that could be removed from the king and given to the people.

However I’m going to recommend his other book, ‘On Power’, as it’s book that defines the role of power and its relationship to sovereignty and where it came from. It goes into the role of sovereign or dux, and his or her shared responsibility with the larger group. This book explains how absolute monarchy is a recent concept, and as a result of the Enlightenment. It points out the hazards of absolute power within any form of government. It then goes into change v.s. distrust of initiative, and emerging liberalism. One of the best political treatises I have ever read. Bertrand de Jouvenel is unconventional, creative, very thorough and stringent. It's not easy to sum up, as the book is rather suggestive in nature. It doesn't so much tell you the solutions as make you think for them yourself. It gives you tools with which to overthink and analyse political problems, but doesn't force a solution on you.

Bertrand de Jouvenel (1903-1987) was a French journalist and political theorist. During World War II, he participated in the French resistance movement and finally took refuge in Switzerland, where he finished his masterpiece, On Power.

Jouvenel was troubled by the savagery of the war. Such a total war, Jouvenel realised, could not happen without the power of the modern centralised state. Jouvenel called this state, “Power” or “the Minotaur.” The question he set out to analyse was how this monster had grown so large. As indicated by the subtitle of the book, The Natural History of Its Growth, the analysis is meant to be positive political science, as opposed to normative political philosophy. When he wrote On Power, Jouvenel obviously knew little of the libertarian or classical liberal tradition. He has been labelled a “conservative liberal” à la Alexis de Tocqueville (whom Friedrich Hayek, it is worth recalling, does recognise as a full member of the classical liberal tradition).

The modern state has acquired a crushing power that includes war and conscription, an “inquisitorial mechanism of taxation,” and a police more effective than at any time in history. “Even the police regime, that most insupportable attribute of tyranny, has grown in the shadow of democracy,” Jouvenel observes. “No absolute monarch ever had at his disposal a police force comparable to those of modern democracies.” Power has continued and continues to grow.

Power is “command that lives for its sake and for its fruits.” State rulers want power and the perks that come with it. But, Jouvenel explained, in the very process of being self-interested, Power also benefits its subjects compared to what would be their situation in the anarchic state of nature. To gain their support and to make them more productive and taxable, Power provides its subjects with security, order, and other public goods. This is an old philosophical idea dear to defenders of absolutism, but it carries an analytical value of its own.

From Antiquity until the 16th or 17th century, Jouvenel argues, three ways existed to limit Power: divine law, fixed customary law, and powerful social authorities such as the ancient or the medieval aristocracy. All these were overcome. Divine law was brushed away by modern rationalism. Fixed customary law was replaced by changing laws made by absolute monarchs and, even more, by democratic parliaments. The aristocracy was stripped of any power.

Sovereignty, Jouvenel explains, is “the idea… that somewhere there is a right to which all other rights must yield.” The king claimed sovereignty against the aristocracy. Once the aristocracy was defeated, “the people” invoked it against the king. The king was simply replaced by the people or, in practice, by its representatives.

Jouvenel conceives liberty as “the direct, immediate, and concrete sovereignty of man over himself.” It is not participation in government, which is “absurdly called ‘political liberty’.” He forcefully argues that no regime other than aristocracy is “equally allergic to the expansion of Power.” Between the fall of the Roman empire and the modern nation-state, kings had to negotiate grants in aid from the aristocrats in order, for example, to fight wars, which were limited for this very reason. General conscription was unknown and impossible.

Jouvenel argues that liberty has aristocratic roots for it came from aristocrats who had the means and the will to defend their own liberty against Power. Liberty “is a subjective right which belongs to those, and to those only, who are capable of defending it.” It was certainly “a system based on class,” with all the drawbacks that this implies. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a modern prophet of democracy, suggested that slavery might even be the necessary counterpart of free and independent citizens voluntarily devoting their time to public affairs.

To eliminate the independent social power that the aristocrats represented, kings allied themselves with powerless individuals such as the common people and the new capitalist bourgeoisie. Aristocrats were replaced by “statocrats,” individuals who derived their authority only from their position in the service of the state. The new democratic citizens would soon fall under a Power much more encompassing than that of the local lord.

A crucial idea of On Power, which can also be found in Tocqueville, is that instead of restraining Power, popular sovereignty reinforced it. Democracy was conceived by its early theorists as liberty and the rule of law. But another conception, which won the day, identified democracy with the sovereignty of the people. In this conception, democracy replaces the rule of law by the people’s good pleasure, which in practice means the good pleasure of its elected representatives and the government bureaucracy.

The popular sovereign became the new king, but without the restraints that law and aristocracy previously imposed. Liberty diminished since “[e]very increase of state authority must involve an immediate diminution of the liberty of each citizen.” Like ancient philosophers, Jouvenel sees aristocracy, democracy, and tyranny as the only feasible regimes.

5. The Role of Modern Monarchy: European Monarchies Compared edited by Robert Hazell and Bob Morris (2020)

No new political theory on this topic has been developed since Walter Bagehot wrote about the monarchy in The English Constitution (1867). The same is true of the other European monarchies. So this is a welcome update in terms of what’s happened in the last 150 years or so across Europe. It’s actually the brainchild of a project coming out of the Constitutional Unit at University College London. The book is excellent and is written by experts from Belgium, Denmark, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden and the UK. It considers the constitutional and political role of monarchy, its powers and functions, how it is defined and regulated, the laws of succession and royal finances, relations with the media, the popularity of the monarchy and why it endures. This collections of essays written by academics is the first comparative study of its kind and broadly asks with their formal powers greatly reduced, how has this ancient, hereditary institution managed to survive and what is a modern monarch’s role? What theory can be derived about the role of monarchy in advanced democracies, and what lessons can the different European monarchies learn from each other?

The public look to the monarchy to represent continuity, stability and tradition, but also want it to be modern, to reflect modern values and be a focus for national identity. The whole institution is shot through with contradictions, myths and misunderstandings. This book should lead to a more realistic debate about our expectations of the monarchy, its role and its future. As a whole these twenty contributors notes several factors to the continued survival of the constitutional monarchy in Europe today.

Firstly, remain politically neutral. Monarchs who are too interventionist will encounter resistance and lose their reputation for neutrality. Secondly, avoid scandals, or any hint of corruption. Thirdly, keep the team small. The greater the size of the royal family, the greater the risk that one of its members may get into trouble and cause reputational damage; and the greater the risk of criticism about excessive cost, and too many hangers-on. Fourthly, Understand better the plight of the minor royals, allow them a means of escape and equip them to enter careers commensurate with their abilities. They lead lives of great privilege, but lack fundamental freedoms: the right to privacy and family life which ordinary citizens take for granted, free choice of careers, freedom to marry whom they like. Fifthly, keep in your lane. Although hereditary, the monarchy is accountable, just like any other public institution. The most high profile example is King Juan Carlos of Spain, now in exile and the subject of prosecutorial investigations. But he is not alone: other monarchs who stepped out of line have also lost their thrones.

Arguably the biggest factor of all is how accountable the monarchy is to its subjects - as paradoxical as that sounds. Accountability of the monarchy in a democracy is vital and necessary. Individual monarchs can be forced to abdicate; and support for the institution as a whole can be tested in a referendum. During the twentieth century there were 18 referendums held on the monarchy in nine European countries. It was through referendums that the monarchy came to an end in Italy and Greece, and was restored in Spain; and through referendums that the future of the monarchy was endorsed in Belgium, Denmark, Luxembourg and Norway. The monarchy may seem the very antithesis of a democratic or accountable institution; but ultimately continuation of the monarchy depends on the continuing support of the people for the roles it is seen to undertake. And people can be equally fickle with emotions as they can be reasonable and grounded in common sense.

I would also recommend two videos you can watch online which basically saves your from reading the above - or watching it may inspire you to go and read the books (which would be my intention).

1. Monarchy by David Starkey (TV documentary series)

Monarchy was originally made by Channel 4 as a British TV series that ran from 2004–2007. It was written and presented by the historian David Starkey charting the political and ideological history of the English monarchy from the Saxon period to modern times. The show also aired on PBS stations throughout the United States. You can watch the series on YouTube.

youtube

The first episode looks at discusses the early history of England and the birth of the Monarchy. It looks migration of the Anglo-Saxons into Britain and discusses some early rulers including. It looks at the roles of Aethelbert and his Frankish wife Bertha in the Christianisation of Britain. It examines the dominant reign of King Offa of Mercia. Finally, it looks at Alfred the Great and how he united England against Viking invasion.

2. The Role of Modern Monarchy: European Monarchies Compared: book launch discussion

This is an online discussion hosted by BBC’s David Dimbleby amongst some of the main contributors of the book and the conclusions they reached. It’s very good discussion both wide ranging and insightful how modern monarchies operate across Europe.

youtube

On the face of it, the British monarchy runs against the spirit of the times. Deference is dead, but royalty is built on a pantomime of archaic honourifics and frock-coated footmen. In an age of meritocracy, monarchy is rooted in the unjustifiable privilege of birth. Populism means that elites are out, but the most conspicuous elite of all remains. Identity politics means that narratives are in, but the queen kept her feelings under her collection of unfashionable hats. By rights, support for the crown should have crumbled under Elizabeth has sometimes imagined it might. Instead, the monarchy thrived. And it continues to thrive and thus maddening the bourgeois woke elites and perplexing trendy decolonisation academics.

Writing in the 1860s, Walter Bagehot, The Economist’s greatest editor, noted that under Britain’s constitutional monarchy “A republic has insinuated itself beneath the folds of a monarchy.” The executive and legislative powers of government belonged to the cabinet and Parliament. The crown was the “dignified” part of the state, devoted to ceremony and myth-making. In an elitist age, Bagehot saw this as a disguise, a device to keep the masses happy while the select few got on with the job.

You do not need a monarchy to pull off the separation, obviously. Countries like Ireland rub along with a ceremonial president instead. He or she comes from the people and has, in theory, earned the honour. A dud or a rogue can be kicked out or prosecuted. To a degree, history lays down the choice - it would be comic to invent a monarchy from scratch.

However, constitutional monarchy has one advantage over figurehead presidencies that is the final reason behind Elizabeth’s surprising success: its mix of continuity and tradition, which even today is tinged with mystical vestiges of the healing royal touch. All political systems need to manage change and resolve conflicting interests peacefully and constructively. Systems that stagnate end up erupting; systems that race away leave large parts of society left behind and they erupt, too.

Under Elizabeth, Britain changed unrecognisably. Not only has it undergone social and technological change, like other Western democracies, but it was also eclipsed as a great power. More than once, most recently over Brexit, politics choked. During all this upheaval, the continuity that monarchy displays has been a moderating influence. George Orwell, no establishment stooge, called it an “escape-valve for dangerous emotions”, drawing patriotism away from politics, where love of country can rot into bigotry. Decaying empires are dangerous. Britain’s decline has been a lot less traumatic than it might have been.

Elizabeth’s sleight of hand was to renew the monarchy quietly all the while, and King Charles’s hardest task will be to renew it further. The prospect is daunting, but entirely possible. My money is on the monarchy.

Anyway, this is by no means a definitive listing of books or other kinds of resources such as online resources. But I hope I can give you the flavour of the terrain of how and why monarchies continue to persist but also thrive in today's democratic environment.

Thanks for your question.

#ask#question#monarchy#united kingdom#britain#europe#constitutional monarchy#democracy#the state#society#politics#aristocracy#governance#constitutional#elizabeth II#king charles III#walter bagehot#david starkey

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is going around so let's just... fact-check this for a second and see what this would mean for Ed. So, some questions we should ask ourselves when presented with new information:

"What's the source?"

This comes from the book "X-Marks: Native Signatures of Assent" A summary of the book is this:

"Is OP representing the work accurately?"

I haven't read the book, although I did download a copy to look through. I don't think OP is presenting it accurately. The book isn't about X-marks as a signature exactly but uses it as a metaphor to discuss Indigenous American identity, assimilation, and traditionalism.

X-marks were chosen because of the connotation they carried. When signing treaties, tribes would use an X since they often weren't English literate. Because of the history of coercion, colonialism, and resistance, the author is using the term "X-mark" as a way of discussing a multitude of actions and situations. X-mark is being utilized as a metaphor by the author.

"Is this applicable to the Māori?"

Honestly, most likely not. The book is about Indigenous Americans and explores their cultural identity. Although Ed is Indigenous, he isn't Indigenous American and we should really not conflate these histories.

Especially because the Māori have their own history of colonialism and treaties that is specific to them. It's important to not erase this because it's still relevant today within the conversation of decolonization since the main point of contention with the treaty is that the English version and Māori version are different. If you want to read more about this here ya go!

"Is this applicable to Ed?"

Honestly, no because why would he know any of this? He's from Britain and it's likely that the only other person who's Māori he knows is his mother who probably didn't teach him much about their culture.

"What would this mean for Ed if it was true?"

Still not much honestly? I don't see how X-marks existence would mean he's literate. X-marks were used because the signer didn't know how to sign their names. It seems odd to use this as reasoning for why he would be literate.

"Is it racist to say Ed is illiterate? (Since this is where people are already jumping to)"

Nah. There's proof either way for Ed being literate/illiterate. We won't know until it's confirmed by canon or someone on the show.

Saying it's racist to assume Ed is illiterate doesn't make sense when, for the time period, his class position, and his canon backstory, it's extremely likely that he can't read. Like canonly most of the crew can't read too? There's mixed signals in the show's text for if Ed can or not? I don't know why this is even a conversation tbh fkd bgdfjkbgd

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is "The Rabbit Queen"?

Via rabbitqueenmusical.com:

Once upon a time…

The world was hoodwinked by a poor illiterate woman named Mary Toft. The year was 1726 and over the course of several months, Mary managed to fool the finest doctors, scientists, and nobles into believing she could give birth to rabbits.

Delivering on that promise, Mary performed the mesmerizing spectacle 17 times over, securing her place in history as "The Rabbit Queen”. That is, until one fateful day when she was brought down by a single kernel of evidence.

The story of Mary’s viral hoax and subsequent cancellation is one that touches on themes of bodily autonomy, women’s reproductive freedom, gender and class roles, and the dangers of blindly trusting authority figures and the media.

The musical is based on a true historical hoax in 1726 Britain, with book written by Ilana Gordon, music by Laura Watkins, and lyrics by Jaime Lyn Beatty and Laura Watkins.

The musical is currently being developed and workshopped in association with New Musicals Inc. An informal reading was held on July 31st, 2023, featuring cast members such as Jeff Blim, Corey Dorris, and Angela Giarratana.

#the rabbit queen: a new musical#the rabbit queen#rabbit queen musical#jaime lyn beatty#jeff blim#corey dorris#angela giarratana

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

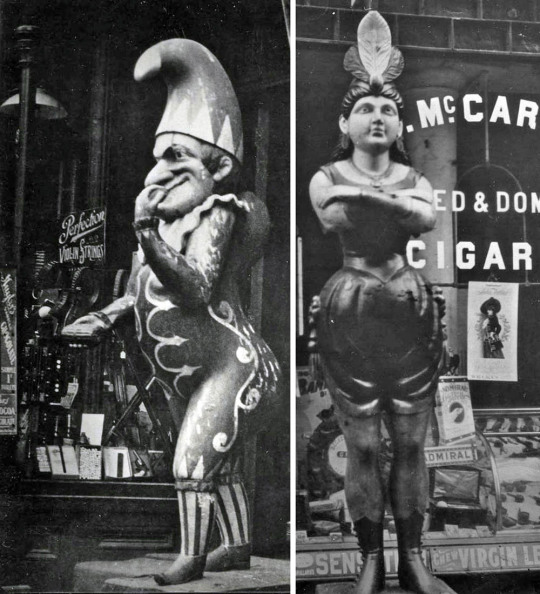

Life-sized wooden statues outside cigar stores, 1926.

Shops in the 18th and 19th centuries often had signs or figures outside to indicate to an illiterate or non-English speaking population the type of goods or services provided. Wooden carvings of people indicated that tobacco was for sale inside. Statues of Indians were common, for it was the native people who had introduced European settlers to the stuff. In Britain, carvers had never seen a real Indian, so they had to use their imagination, and the result was far from reality.

Cigar store Indians came to the U.S. in the late 18th century. In time, carvers expanded their repertoire to include other kinds of figures—Turks with turbans, soldiers, fashionable ladies. Many of the carvers, who began by creating figures for ships, were located in New York. By the end of the 19th century, however, cities began passing zoning ordinances about the width of streets, and these figures began to disappear. But, as Hoppé's photos testify, there were still some being used in 1926. Today they are collectors' items.

Photos: E.O. Hoppé via the Bruce Silverstein Gallery

#New York#NYC#vintage New York#1920s#E.O. Hoppé#cigar stores#cigar store Indians#statues#wooden statues#carvings#advertising#tobbacconist#tobacco#tobacco stores

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The UN’s special rapporteur to Britain, Philip Alston, remarked in 2018: “British compassion for those who are suffering has been replaced by a punitive, mean-spirited, and often callous approach.” Policies such as the benefit cap, the two-child limit on child benefits, the bedroom tax and the extensive use of sanctions to punish those already in need of financial support are the embodiment of that approach. One would expect that a party seeking its first electoral victory in 18 years would seek to distance itself from the pain and hardship that has been experienced by so many for too long.”

#austerity#public services#uk politics#keir starmer#the 14th 15th 16th and 17th years of starving the public sector

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

A British writer penned the best description of Donald Trump I’ve ever read:

“Why do some British people not like Donald Trump?”

A few things spring to mind. Trump lacks certain qualities which the British traditionally esteem. For instance, he has no class, no charm, no coolness, no credibility, no compassion, no wit, no warmth, no wisdom, no subtlety, no sensitivity, no self-awareness, no humility, no honour and no grace – all qualities, funnily enough, with which his predecessor Mr. Obama was generously blessed. So for us, the stark contrast does rather throw Trump’s limitations into embarrassingly sharp relief.

Plus, we like a laugh. And while Trump may be laughable, he has never once said anything wry, witty or even faintly amusing – not once, ever. I don’t say that rhetorically, I mean it quite literally: not once, not ever. And that fact is particularly disturbing to the British sensibility – for us, to lack humour is almost inhuman. But with Trump, it’s a fact. He doesn’t even seem to understand what a joke is – his idea of a joke is a crass comment, an illiterate insult, a casual act of cruelty.

Trump is a troll. And like all trolls, he is never funny and he never laughs; he only crows or jeers. And scarily, he doesn’t just talk in crude, witless insults – he actually thinks in them. His mind is a simple bot-like algorithm of petty prejudices and knee-jerk nastiness.

There is never any under-layer of irony, complexity, nuance or depth. It’s all surface. Some Americans might see this as refreshingly upfront. Well, we don’t. We see it as having no inner world, no soul. And in Britain we traditionally side with David, not Goliath. All our heroes are plucky underdogs: Robin Hood, Dick Whittington, Oliver Twist. Trump is neither plucky, nor an underdog. He is the exact opposite of that. He’s not even a spoiled rich-boy, or a greedy fat-cat. He’s more a fat white slug. A Jabba the Hutt of privilege.

And worse, he is that most unforgivable of all things to the British: a bully. That is, except when he is among bullies; then he suddenly transforms into a snivelling sidekick instead. There are unspoken rules to this stuff – the Queensberry rules of basic decency – and he breaks them all. He punches downwards – which a gentleman should, would, could never do – and every blow he aims is below the belt. He particularly likes to kick the vulnerable or voiceless – and he kicks them when they are down.

So the fact that a significant minority – perhaps a third – of Americans look at what he does, listen to what he says, and then think ‘Yeah, he seems like my kind of guy’ is a matter of some confusion and no little distress to British people, given that:

• Americans are supposed to be nicer than us, and mostly are.

• You don’t need a particularly keen eye for detail to spot a few flaws in the man.

This last point is what especially confuses and dismays British people, and many other people too; his faults seem pretty bloody hard to miss. After all, it’s impossible to read a single tweet, or hear him speak a sentence or two, without staring deep into the abyss. He turns being artless into an art form; he is a Picasso of pettiness; a Shakespeare of shit. His faults are fractal: even his flaws have flaws, and so on ad infinitum. God knows there have always been stupid people in the world, and plenty of nasty people too. But rarely has stupidity been so nasty, or nastiness so stupid. He makes Nixon look trustworthy and George W look smart. In fact, if Frankenstein decided to make a monster assembled entirely from human flaws – he would make a Trump.

And a remorseful Doctor Frankenstein would clutch out big clumpfuls of hair and scream in anguish: ‘My God… what… have… I… created?' If being a twat was a TV show, Trump would be the boxed set.”

-Nate White

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

A British writer penned the best description of Donald Trump I’ve ever read:

A British writer penned the best description of Donald Trump I’ve ever read:

“Why do some British people not like Donald Trump?”

A few things spring to mind. Trump lacks certain qualities which the British traditionally esteem. For instance, he has no class, no charm, no coolness, no credibility, no compassion, no wit, no warmth, no wisdom, no subtlety, no sensitivity, no self-awareness, no humility, no honour and no grace – all qualities, funnily enough, with which his predecessor Mr. Obama was generously blessed. So for us, the stark contrast does rather throw Trump’s limitations into embarrassingly sharp relief.

Plus, we like a laugh. And while Trump may be laughable, he has never once said anything wry, witty or even faintly amusing – not once, ever. I don’t say that rhetorically, I mean it quite literally: not once, not ever. And that fact is particularly disturbing to the British sensibility – for us, to lack humour is almost inhuman. But with Trump, it’s a fact. He doesn’t even seem to understand what a joke is – his idea of a joke is a crass comment, an illiterate insult, a casual act of cruelty.

Trump is a troll. And like all trolls, he is never funny and he never laughs; he only crows or jeers. And scarily, he doesn’t just talk in crude, witless insults – he actually thinks in them. His mind is a simple bot-like algorithm of petty prejudices and knee-jerk nastiness.

There is never any under-layer of irony, complexity, nuance or depth. It’s all surface. Some Americans might see this as refreshingly upfront. Well, we don’t. We see it as having no inner world, no soul. And in Britain we traditionally side with David, not Goliath. All our heroes are plucky underdogs: Robin Hood, Dick Whittington, Oliver Twist. Trump is neither plucky, nor an underdog. He is the exact opposite of that. He’s not even a spoiled rich-boy, or a greedy fat-cat. He’s more a fat white slug. A Jabba the Hutt of privilege.

And worse, he is that most unforgivable of all things to the British: a bully. That is, except when he is among bullies; then he suddenly transforms into a snivelling sidekick instead. There are unspoken rules to this stuff – the Queensberry rules of basic decency – and he breaks them all. He punches downwards – which a gentleman should, would, could never do – and every blow he aims is below the belt. He particularly likes to kick the vulnerable or voiceless – and he kicks them when they are down.

So the fact that a significant minority – perhaps a third – of Americans look at what he does, listen to what he says, and then think ‘Yeah, he seems like my kind of guy’ is a matter of some confusion and no little distress to British people, given that:

• Americans are supposed to be nicer than us, and mostly are.

• You don’t need a particularly keen eye for detail to spot a few flaws in the man.

This last point is what especially confuses and dismays British people, and many other people too; his faults seem pretty bloody hard to miss. After all, it’s impossible to read a single tweet, or hear him speak a sentence or two, without staring deep into the abyss. He turns being artless into an art form; he is a Picasso of pettiness; a Shakespeare of shit. His faults are fractal: even his flaws have flaws, and so on ad infinitum.

God knows there have always been stupid people in the world, and plenty of nasty people too. But rarely has stupidity been so nasty, or nastiness so stupid. He makes Nixon look trustworthy and George W look smart. In fact, if Frankenstein decided to make a monster assembled entirely from human flaws – he would make a Trump.

And a remorseful Doctor Frankenstein would clutch out big clumpfuls of hair and scream in anguish: ‘My God… what… have… I… created?' If being a twat was a TV show, Trump would be the boxed set.”

-Nate White

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not a new academic journal article about Paul Gavarni, but newly found by me: "Parisian Social Statistics: Gavarni, 'Le Diable à Paris,' and Early Realism" by Aaron Sheon (Google Drive link). I think this will be of interest to many of my friends here—

Le Diable à Paris is important to art historians because it included a series of illustrations by Guillaume Sulpice Chevallier, known as Gavarni, the popular Parisian illustrator who was one of the city's most colorful personalities—a bohemian and flaneur. His entire series of illustrations showing types of Parisians, particularly the poorest ones, was popular enough to be later assembled as Les gens de Paris in a separate book. Each illustration was captioned by Gavarni himself, who took pride in writing a touching or witty description for each image.

Gavarni's illustrations in Le Diable à Paris included some of the cruelest scenes of waifs, paupers, beggars, and les misérables that had yet been done. It is surprising that they have been overlooked in recent studies of the politicization of French artists in the 1840s. The curious neglect of his imagery of the destitute, unemployed Parisians in Les gens de Paris appears to be due to the general neglect of Gavarni's oeuvre. When considered at all, Gavarni has been viewed by most historians as a conservative artist, a gay blade who lived only for carnavals and bohemian self-indulgence. This assumption may be incorrect.

This is a really, really, really good article about Gavarni's world, probably the best source I've found next to his biography by Jules and Edmond de Goncourt (which is in French). There is some fascinating background on the gathering of social data and the development of the modern statistical bureau in early 19th century France; and the content of Le Diable à Paris is a LOT darker and more socially conscious than I imagined. I had thought that it was a more light-hearted work before Masques et Visages but definitely not. (Which makes it even more inexplicable that people in 1840s Britain thought that Gavarni was just a dandy who made elegant fashion drawings, only to be disappointed by his more complicated reality).

Very interesting information about provincial peasants flocking to 19th century Paris, where they lived in slums and faced discrimination and mockery for their regional dress and accents: "In the 1840s a number of pejorative words began to appear in novels and articles describing the immigrants: misérables, wretches, barbarians, savages, indigents, illiterates, nomads, vagabonds, and vagrants. Some writers described them as the 'mob' and a 'nation within the nation.'"

Special to @sanguinarysanguinity: I have FINALLY found some of Gavarni's mathematical work, thanks to this article! "Des fonctions curvitales" in Comptes Rendus des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences (1865). It's in French but maybe the equations will give you some idea?

Gavarni's publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel was a lot younger than I imagined! I had no idea Hetzel was a political activist in the 1830s and 1840s (and opposed to the regime of Louis Philippe). He signed Honoré de Balzac to a publishing contract, too! Note to self for the upteenth time: I have to start reading Honoré de Balzac, who is constantly being brought up in association with/compared with Gavarni.

Sheon puts a pretty good case together that Gavarni should be regarded as more politically progressive and less shallow, although it makes me ponder how little I know about him. Gavarni is still enigmatic to me, and I have so many questions.

#paul gavarni#french history#1840s#les misérables#but not the novel#july monarchy#early victorian era#sheon gets bonus points for getting gavarni's birth name correct#(i wish that was less rare)#why are my favourite historical figures always obscure and neglected#also mister gavarni i'm sorry i am so bad at reading french i don't properly appreciate your touching and witty captions :(

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

I don't suppose you've already done the research on what Kinging entails when your country is largely illiterate and can share it with me can you. Because my ass desperately wants something other than Paperwork for the house of eorl to be doing all the time but I haven't even started looking that shit up yet.

I don't know about that in general, but I do know about Anglo-saxons, which is the culture that Tolkien drew the most inspiration from for the Rohirrim. (Bear in mind this information is sort of old, as I lost all my books on the matter shortly after graduating college and have only intermittently pursued it since, but it should give you some starting points at least.)

Tolkien drew a lot of inspiration from Beowulf, as well as other ancient Anglo-saxon documents, but Beowulf is probably the most accessible to the modern reader, and certainly the most complete story we have from that culture. If you're interested there's a copy you can read for free online here. This is, however, rather an old translation and kind of dense so you might consider picking up a more recent one from the library (or a retelling instead of a translation). Another good resource for the culture in general is Time Team, a British TV show about an archeological team that do digs in Great Britain. There are a ton of different time periods they cover, but the ones of interest to this discussion would actually be some of the oldest ones, Iron Age and then basically anything pre-Roman occupation. There are a lot of full episodes available on YouTube. (Do bear in mind that this show has been running for multiple decades, and some information in the older episodes is out of date.)

The Anglo-saxon king had three basic duties. The first, and the one that figures most prominently in stories like Beowulf, was throwing huge fucking parties every night. Maybe not every night, but part of their job was to entertain their subjects and reward them for their loyalty -- and this seems to have often taken the form of huge fucking parties, as well as the giving of gifts.

The second was to manage their household -- in early Britain the king's household was for a long time really just another household. They had fields and herds that were theirs and from which they drew most of their own food and supplies, and which were cared for and maintained by members of the king's household (or by slaves, but that's obviously not relevant to LotR fanfiction in particular). 'King' seems to be a sort of glorified term that Tolkien used to describe what the modern reader would think of more as a chieftain of sorts -- the person who calls the shots and has a bigger house, but still living a fairly similar life to the rest of their people, with similar problems to manage.

(Indeed, the Rohirrim are probably closer to Iron Age Briton cultures than the traditional 12th century medieval culture most fantasy borrows from in most respects.)

And the third was to maintain a group of warriors, so that if their people were ever in danger, they could take care of it. There was also a certain amount of cultural glory ascribed to victory on the battlefield, which definitely led to some unnecessary warfare, though we have so little actual history from that period that I can't give any real details on that.

Although I don't really know much about it, I would add a fourth duty onto that: to resolve disputes among their people, whether by hearing them directly and passing judgement, appointing someone else to do that if necessary, or by making and enforcing laws to minimize these disputes. (And the legal system wouldn't necessarily be more rudimentary than in a literate society -- the king might assign members of his household or hire people to memorize all of the laws. Longform poems like Beowulf were also memorized which is how they were passed down until they came to someone who wrote them down. It seems that people in illiterate cultures have an amazing capacity for memory, most likely taking advantage of some tricks that those of us in literate societies have forgotten. Ironically.) This would also encompass the punishment of criminals -- unfortunately I know basically nothing about actual Anglo-saxon law and what crimes might have invited what sort of punishments.

Another thing that comes up in Beowulf but also in writings as late as the twelfth century is the concept of the king as the giver of gifts (which, in my opinion, ties into the first and the third duties). The king bought the loyalty of their people, especially their warriors, by giving them gifts. Most notably these were often gifts of treasure, valuable practical items, food and drink, (sometimes slaves, but again not relevant in this context), or jewelry. Indeed, in Beowulf the king is often referred to as "the ring-giver," since rings were a popular gift for this purpose, being both extremely portable and extremely valuable. Obviously Tolkien borrowed the concept of people having received rings as gifts owing loyalty to the one who gave them for other parts of his legendarium. With that in mind you may or may not want to incorporate that detail into your interpretation of Rohirric culture (though personally I love the idea of what Sauron did being a corruption of a perfectly respectable exchange). But there should certainly be gifts. Probably Big Fucking Parties.

I can't say much more without getting into my personal interpretation of things, but there are hints in the text about certain responsibilities the king. Before Gandalf talked some sense back into him, Theoden wasn't being a very good king. Although there was a standing army, Wormtongue was urging him to send them off on wild goose chases and he was listening, so honestly there may as well not have been. He rewarded Eomer's loyalty with imprisonment, he was letting Wormtongue handle anyone who came into the hall looking for him (and therefore not resolving disputes fairly), and he wasn't offering gifts of any sort to anyone. But as soon as Gandalf talked him around, he immediately turned around and started being a good king. He offered hospitality and food to his guests (and then weapons and armor later), he defended his people at Helm's Deep and then went out to confront Saruman and take care of the threat for good, and he resolved the dispute between Wormtongue and Everybody Else in a reasonably fair manner. Although we don't really see a lot of the royal household and therefore don't have a clear idea of how it was being maintained, he also started at least trying to do right by his niece and nephew as well.

This turned out a lot longer than I expected. Hopefully it gives you some ideas, and at least a few ideas of where to look next!

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why do British people not like Donald Trump?

Someone asked "Why do British people not like Donald Trump?"

Nate White, an articulate and witty writer from England, wrote this magnificent response:

"A few things spring to mind.

Trump lacks certain qualities which the British traditionally esteem.

For instance, he has no class, no charm, no coolness, no credibility, no compassion, no wit, no warmth, no wisdom, no subtlety, no sensitivity, no self-awareness, no humility, no honour and no grace - all qualities, funnily enough, with which his predecessor Mr Obama was generously blessed.

So for us, the stark contrast does rather throw Trump’s limitations into embarrassingly sharp relief.

Plus, we like a laugh. And while Trump may be laughable, he has never once said anything wry, witty or even faintly amusing - not once, ever.

I don’t say that rhetorically, I mean it quite literally: not once, not ever. And that fact is particularly disturbing to the British sensibility - for us, to lack humour is almost inhuman.

But with Trump, it’s a fact. He doesn’t even seem to understand what a joke is - his idea of a joke is a crass comment, an illiterate insult, a casual act of cruelty.

Trump is a troll. And like all trolls, he is never funny and he never laughs; he only crows or jeers.

And scarily, he doesn’t just talk in crude, witless insults - he actually thinks in them. His mind is a simple bot-like algorithm of petty prejudices and knee-jerk nastiness.

There is never any under-layer of irony, complexity, nuance or depth. It’s all surface.

Some Americans might see this as refreshingly upfront.

Well, we don’t. We see it as having no inner world, no soul.

And in Britain we traditionally side with David, not Goliath. All our heroes are plucky underdogs: Robin Hood, Dick Whittington, Oliver Twist.

Trump is neither plucky, nor an underdog. He is the exact opposite of that.

He’s not even a spoiled rich-boy, or a greedy fat-cat.

He’s more a fat white slug. A Jabba the Hutt of privilege.

And worse, he is that most unforgivable of all things to the British: a bully.

That is, except when he is among bullies; then he suddenly transforms into a snivelling sidekick instead.

There are unspoken rules to this stuff - the Queensberry rules of basic decency - and he breaks them all. He punches downwards - which a gentleman should, would, could never do - and every blow he aims is below the belt. He particularly likes to kick the vulnerable or voiceless - and he kicks them when they are down.

So the fact that a significant minority - perhaps a third - of Americans look at what he does, listen to what he says, and then think 'Yeah, he seems like my kind of guy’ is a matter of some confusion and no little distress to British people, given that:

* Americans are supposed to be nicer than us, and mostly are.

* You don't need a particularly keen eye for detail to spot a few flaws in the man.

This last point is what especially confuses and dismays British people, and many other people too; his faults seem pretty bloody hard to miss.

After all, it’s impossible to read a single tweet, or hear him speak a sentence or two, without staring deep into the abyss. He turns being artless into an art form; he is a Picasso of pettiness; a Shakespeare of shit. His faults are fractal: even his flaws have flaws, and so on ad infinitum.

God knows there have always been stupid people in the world, and plenty of nasty people too. But rarely has stupidity been so nasty, or nastiness so stupid.

He makes Nixon look trustworthy and George W look smart.

In fact, if Frankenstein decided to make a monster assembled entirely from human flaws - he would make a Trump.

And a remorseful Doctor Frankenstein would clutch out big clumpfuls of hair and scream in anguish:

'My God… what… have… I… created?

If being a twat was a TV show, Trump would be the boxed set."

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love England's reaction to what has overall been a pretty fuckin tame and nonpartisan visit to this shithole by Joe Biden.

A lot of the anger from Tories is, as it often is with Tories, an attempt to export blame for Britain's slow and crippling demise to anyone but them.

The central tory argument boils down to "the United States is not willing to play ball with the UK economically. Not because of a list of palpable and identifiable factors (The UKs economic crisis mainly being owed to Brexit, an absolute refusal by the UK government to solve the crisis that Northern Ireland is facing due to Brexit, the UKs lack of world power under a Tory government) but, instead, as some dark and vindictive hatred Biden has towards the British for being British.

The fact of the matter is that the modern UK is a money sink, not due to outside factors like war or natural disaster, but due to a case of terminal hatred of foreigners that has underlined the entire existence of country, empire to now.

On the other hand, Ireland now boasts an amazing standard of living in comparison (even taking into account an unprecedented housing and cost of living crisis), a much more welcome and progressive attitude towards immigration, and what seems to be a general openness to diplomacy at large.

The Tories hate this idea, because British nationalism dictates that the Irish are an illiterate backwater; and once you throw immigrant groups from Brazil, India, and other places that British nationalism naturally prescribes inferiority to into the mix, Tory logic should dictate that the situation will worsen.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from a reddit comment:

I was making a broader point about how the (classic) show's perceived cultural ''Britishness'' is oversimplistic considering its origins (& values which are inherently Humanist ergo non-nationalist). If you contrast [Doctor] Who with S[tar] T[rek], a right-wing American techno-dystopian wet-dream (& ultra-nationalist bordering blatantly Fascist) Who comes across as considerably less flag-waving, Jingoistic or nationalist and in many stories characters with overtly insular or nationalistic worldviews (Chinn in Axos, the fascist Britain in Inferno, Richard, who never even visited England for any real length of time & his court in The Crusades, Trenchard in The Sea Devils, Baker in The Silurians) or paternalistic worldviews (I.e. Barbara's White Saviour Complex in The Aztecs) are portrayed as buffoonish, obliviously blinkered to reality or utterly unhinged.

Imagine what it must be like to be so media illiterate that you try to claim that Star Trek was:

Right-wing

Techno-dystopian

Ultra-nationalist

Boarding on fascist (???)

(Not to mention that Star Trek did a fascist mirror universe years before before Doctor Who had the same idea in Inferno...)

Like, Doctor Who and Star Trek are two peas in a pod when it comes to politics? I don't understand how someone could compare Classic Who and Star Trek TOS and conclude they have starkly different politics.

They also replied:

Star Trek's complete lack of democracy & overt emphasis on overwhelming military force makes it overtly Fascistic in practice if not ideologically (I didn't comment or even imply ST is racist btw, fascism & racism are distinct concepts, its inclusion of Black characters does nothing to counter its rapacious militarism & Manifest Destiny, so it's also hypocritical; Trek follows on from the US Techno-Fascism Space Empire 1776 x 2.0 tradition of US SF see ''Starship Stormtroopers'' by Michael Moorcock). The Dr supports UNIT as a last resort, often critically & under protest whilst always trying to find a more peaceful or at least less violent solution, btw featuring the Military & promoting Militarism aren't the same, many Who stories feature irregulars, volunteers or guerrillas more frequently, and sometimes in a more positive light, than regular forces who are often seen as too inflexible to deal with (non) non-conventional threats (& often the Regs in Who, other than UNIT, are on the wrong side; the only story where they're neutral is probably Androzani). OTOH fair point on the Silurians. More broadly the Dr's used by the Timelords as a literal One-Man-Army (the Celestial Intervention Agency).

Just... What???

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Medieval Europe and SW Asia in One Post

Fun fact for those outside the US: Americans are mostly taught the history of our own country in K-12 schools. (In some states, badly.) We get 9-10 years of US history, 1 year that’s divided up between Civics (how the US government works) and the history of the individual state you’re in, and 1-2 years of World History that does NOT cover anything in Europe or SW Asia after the fall of Rome. Which means that to learn that stuff, you either have to take those history courses in college/university, or do a lot of independent reading.

I did a lot of independent reading.