#i.a.l. diamond

Photo

The Apartment (1960)

written by I.A.L. Diamond and Billy Wilder

directed by Billy Wilder

cinematography by Joseph LaShelle

When Harry Met Sally... (1989)

written by Nora Ephron

directed by Rob Reiner

cinematography by Barry Sonnenfeld

#the apartment#when harry met sally...#when harry met sally#billy wilder#i.a.l. diamond#nora ephron#rob reiner#barry sonnenfeld#joseph lashelle#shirley maclaine#billy crystal#auld lang syne

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

.

It's a whole different business now. The kids with beards have taken over. They don't need scripts, just give 'em a hand-held camera with a zoom lens.

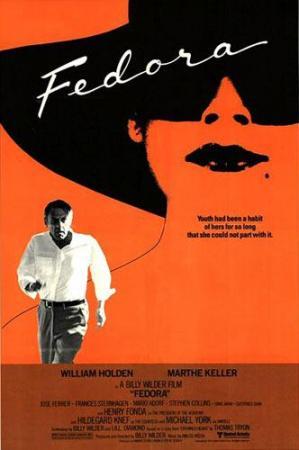

Fedora, Billy Wilder (1978)

#Billy Wilder#I.A.L. Diamond#William Holden#Marthe Keller#Hildegard Knef#José Ferrer#Frances Sternhagen#Mario Adorf#Stephen Collins#Henry Fonda#Michael York#Hans Jaray#Gottfried John#Gerry Fisher#Miklós Rózsa#Stefan Arnsten#Fredric Steinkamp#1978

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

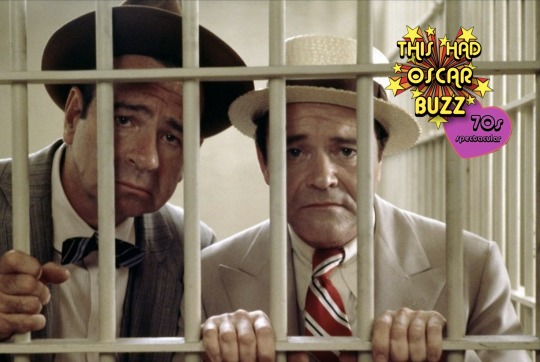

290 - The Front Page (w/ Roxana Hadadi) (70s Spectacular - 1974)

1974 brings us to one of the final films of Billy Wilder, which also reunited a screen duo beloved by both Oscar and audiences, Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau. Vulture writer Roxana Hadadi is back to the show to talk about The Front Page, an oft-adapted farce about newspapermen getting wrapped up in the case of an escaped convict. Most famously retold in a gender swapped version in His Girl Friday, this version stumbles to deliver the best of this director-star trio and missed Oscar's good graces despite multiple nominations in the decade for Mathau and Lemmon, including Lemmon's win the previous year.

This episode, we talk about the victory lap made by Francis Ford Coppola with The Godfather Part II and The Conversation both earning Oscar love. We also talk about the film's apoliticism was atypical of the moment, our love for Ingrid Bergman's Supporting Actress speech, and the hubbub over the acceptance speech for Best Documentary Feature Hearts and Minds.

Topics also include disaster movies becoming the splashy Hollywood product, The Godfather Part II Supporting Actor nominations, and Anderson Cooper talking about his mom hooking up with Marlon Brando.

The 1974 Academy Awards

Subscribe:

Patreon

Spotify

Apple Podcasts

youtube

#Billy Wilder#Jack Lemmon#Walter Mathau#Austin Pendleton#susan sarandon#Carol Burnett#Vincent Gardenia#Charles Durning#David Wayne#Allen Garfield#Paul Benedict#I.A.L. Diamond#The Front Page#Academy Awards#Best Actor#Best Supporting Actor#The Godfather Part II#Oscars#1970s#movies#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birthday remembrance - screenwriter I. A. L. Diamond #botd, best known for his collaborations with Billy Wilder.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

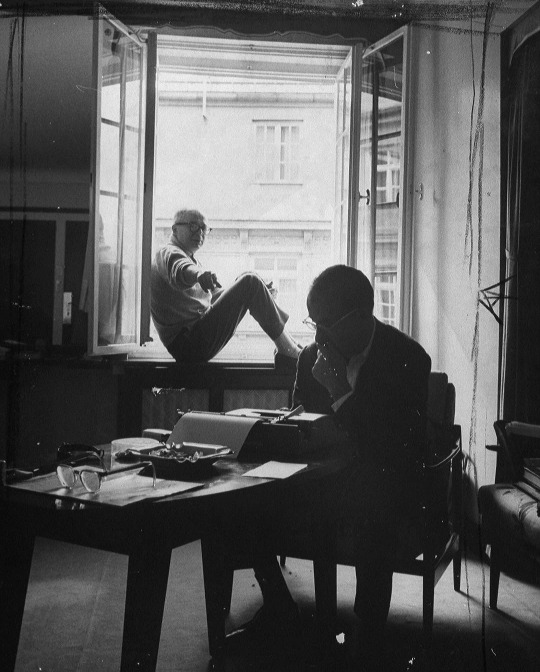

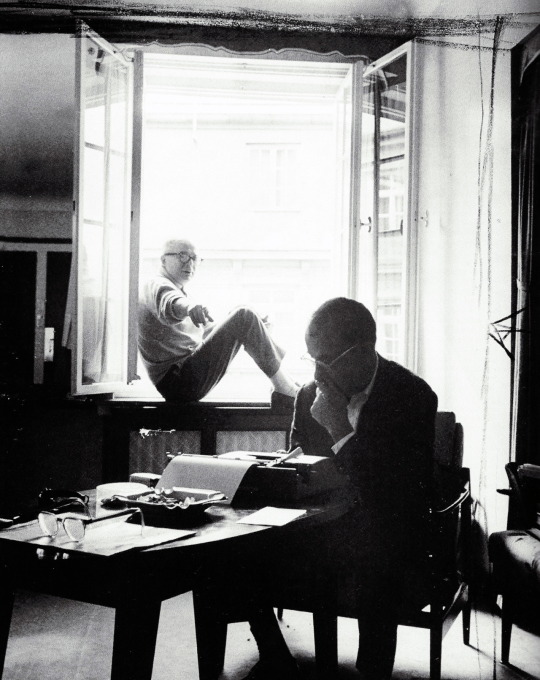

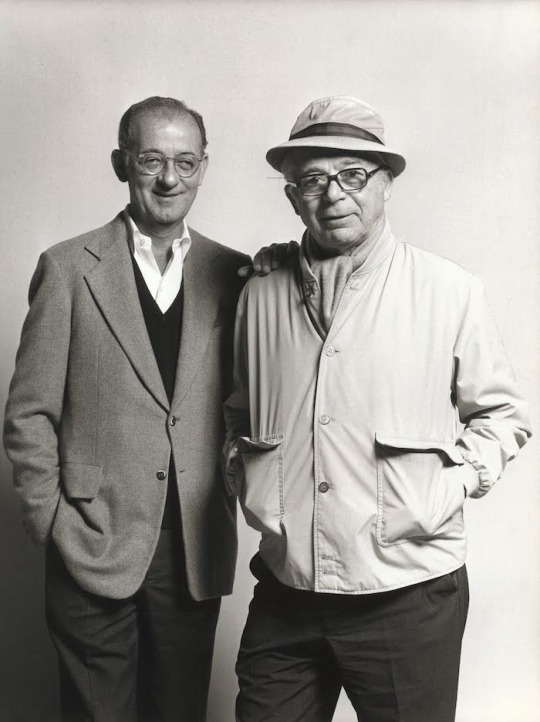

I. A. L. Diamond, June 27, 1920 – April 21, 1988.

At work on One, Two, Three (1961) with Billy Wilder.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Like It Hot (12): "Ba-dee-dly-dee-dly-dee-dly-dum! Boop-boop-a-doop!"

#onemannsmovies review of "Some Like It Hot" (1959). A comedy classic back on the big screen thanks to #EverymanCinema. Near perfect. 4.5/5.

A One Mann’s Movies review of “Some Like It Hot” (1959).

On my Flickering Dreams podcast, we recently talked about our favorite movies by director Billy Wilder. Emma Sewell chose “Some Like It Hot,” which she had watched in a movie theater. I mentioned that it would be wonderful to watch it on the big screen again. As if by magic, Everyman included it in their “Throwback” series this week, and…

View On WordPress

#EverymanCinema#SomeLikeItHot#Billy Wilder#bob-the-movie-man#Cary Grant#Cinema#Everyman#Film#film review#George E. Stone#George Raft#I.A.L. Diamond#Jack Lemmon#Joe E. Brown#Marilyn Monroe#Michael Logan#Movie#Movie Review#Netflix#One Man&039;s Movies#One Mann&039;s Movies#onemannsmovies#onemansmovies#Pat O&039;Brien#Robert Thoeren#Some Like It Hot#Tony Curtis

1 note

·

View note

Photo

I.A.L. "Izzy" Diamond, author of 𝑺𝒐𝒎𝒆 𝑳𝒊𝒌𝒆 𝒊𝒕 𝑯𝒐𝒕 (1959), and 𝑻𝒉𝒆 𝑨𝒑𝒂𝒓𝒕𝒎𝒆𝒏𝒕 (1960). Seen here brainstorming with director Billy Wilder.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jack Lemmon and Marilyn Monroe in Some Like It Hot (Billy Wilder, 1959)

Cast: Marilyn Monroe, Tony Curtis, Jack Lemmon, Joe E. Brown, George Raft, Pat O'Brien, Nehemiah Persoff, Joan Shawlee. Screenplay: Billy Wilder, I.A.L. Diamond, suggested by a story by Robert Thoeren and Michael Logan. Cinematography: Charles Lang. Art direction: Ted Haworth. Film editing: Arthur P. Schmidt. Music: Adolph Deutsch.

Some Like It Hot is a hilarious farce and one of the sweetest natured of Billy Wilder's usually acerbic comedies, thanks to skillful performances by Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis and Marilyn Monroe's breath-taking luminosity. And it would be easy enough to leave it at that. But after all we've learned about sexual orientation and identity, after many feminist critiques of Hollywood's depiction of women, and after many explorations of Monroe's tragic history, it's a little naive to do so. Plumb beneath the surface of what seems to be blithe entertainment and you'll find disturbance in the depths. Take the celebrated ending of the film, for example. Sugar (Monroe) gets Jerry (Curtis), but at what price? As he warns her, he's exactly the kind of guy she knows is bad for her. And Osgood's (Joe E. Brown) shrugging off the fact that Daphne (Lemmon) is a man is one of the funniest moments on film, but in fact, the two men have the kind of chemistry together (as in the tango scene) that works, whereas Curtis and Monroe have no real chemistry. Is the film making a case, well in advance of its time, for same-sex attraction? Probably not Wilder's conscious intention, but what does that matter? As for the difficulties of working with Monroe that Wilder and her co-stars later complained about -- though Curtis eventually retracted the much-quoted statement that kissing her was "like kissing Hitler" -- this remains perhaps her best film and best performance. Imagine the movie with Mitzi Gaynor (originally considered for the part and on standby in case Monroe bailed on it) and you have nothing like the one we now know. In lesser hands than Wilder's the clichés (men in drag on run from gangsters) would have resulted in a second-rate comedy. The real marvel is that Wilder produced something enduring out of clichéd material. Curtis and Lemmon are great, even though their roles are the traditional comic teaming of a bully (Curtis) and a patsy (Lemmon), the formula already worked over by Laurel and Hardy, Abbott and Costello, Bing Crosby and Bob Hope, and Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis. Sometimes what you have to do is take the formula and transcend it.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another new episode! Maybe the weirdest movie I've talked about yet?

Script below the break

Hello and welcome back to the Rewatch Rewind, the podcast where I count down my top 40 most rewatched movies over a 20-year period. My name is Jane, and today I will be discussing number 30 on my list: Twentieth Century Fox’s 1952 science fiction comedy Monkey Business, directed by Howard Hawks, written by Ben Hecht, Charles Lederer, and I.A.L. Diamond, and starring Cary Grant, Ginger Rogers, Charles Coburn, and Marilyn Monroe.

Dr. Barnaby Fulton (Cary Grant) is a chemist developing a formula to reverse some of the symptoms of aging. His boss, Mr. Oxley (Charles Coburn) believes this could become a fountain of youth drug, but Barnaby is more realistic, and merely hopes it could cure his bursitis. He’s been experimenting on chimpanzees but decides to try the newest version on himself – and soon after begins behaving like a frivolous college boy. However, unbeknownst to Barnaby, or anybody else, one of his chimpanzees has mixed a separate formula and poured it into his water cooler, so it’s actually the drink of water he used to wash down his formula that he’s reacting to. After a wild day, much of which he spends with Oxley’s sexy secretary Miss Laurel (Marilyn Monroe), the formula finally wears off and Barnaby is back to his more mature self. He’s eager to try it again, but after hearing about his day, his wife Edwina (Ginger Rogers) drinks his second dose before he has a chance to – and, crucially, also takes a drink of tainted water. And hijinks continue to ensue.

The first time I saw this movie was when it happened to come on TV. It must have been summertime because my sister was away at camp and I distinctly remember writing her a postcard about how I had just watched the funniest movie ever. Thus began a phase when I was kind of obsessed with this movie: I watched it three times in 2003, three times in 2004, and twice in 2005. Then I got a little tired of it and took a break, but I returned to it in 2009 and again in 2010, then twice in 2012, and then once each in 2014, 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2022. There are certain things about this movie that really bother me, which is why I don’t rewatch it as frequently anymore, but there are also things about it that I absolutely love, so I don’t think I will ever abandon Monkey Business completely.

This is the second appearance of both Cary Grant and Ginger Rogers on this podcast, so I’ve already mentioned that they’re two of my faves. To people who have vaguely heard of them, a movie like this might sound out of character for these stars. Cary Grant seems to generally be remembered as a debonair leading man, and Ginger Rogers is generally remembered as Fred Astaire’s frequent dance partner. While those aren’t exactly inaccurate perceptions, they are definitely incomplete. People don’t talk nearly enough about how funny both of them were. Like, no offense to the writers, but with the wrong stars this movie could have been absolute garbage. I mean, I think we can all agree that the story is completely ridiculous. But Grant and Rogers were both comedic geniuses, and basically the only reason I keep revisiting this movie is because of how fun they are to watch in it. By 1952, they were both at least two decades into their film careers, and while they did sometimes play serious dramatic roles, much of their work was in comedy, so they’d had plenty of time to hone their comedic skills, and it shows.

I love that Monkey Business gives them so many opportunities to show off different facets of their comedic talents. The silly tone of the movie is set at the beginning of the opening credits, which Grant keeps interrupting by opening the door, and we hear director Howard Hawks’ voice offscreen saying, “Not yet, Cary.” Then in the first scene, Barnaby and Edwina are at home, preparing to go out for the evening, but Barnaby is distracted thinking about the formula and keeps failing at getting ready properly, until Edwina gives up. They both have such perfect timing and excellent chemistry that this dynamic feels entirely believable and natural, and is also incredibly funny. The first time Barnaby takes the formula, Edwina isn’t around, so we get to see Cary being a goofball by himself, and then with Marilyn Monroe as his “straight man”. But then Edwina takes the formula, and it’s Ginger’s turn to be silly, and Cary’s turn as the straight man. And then later both Barnaby and Edwina drink a bunch of coffee in his office, using the water from the cooler, so they both start acting like children, which means they get to act goofy together for a bit. These changing dynamics are all handled flawlessly. Even when they’re under the influence of the formula and acting silly, they’re still somehow believable. While I’m not convinced that feeling younger would really make people behave quite the way they do, the actors sell it so well that it’s easy to just accept it.

The aspect of their behavior that I have the hardest time accepting is that while under the influence of the formula, both Barnaby and Edwina seem to have the instinct to cheat on each other, in ways consistent with stereotypes about their respective sexes. Younger man Barnaby finds himself drawn to sexy Miss Laurel – I know I mentioned in a previous episode that as an asexual I don’t really understand what “sexy” means, but there seems to be a general consensus that Marilyn Monroe was it. Her character is a fairly basic ditzy blonde who was clearly hired for her looks and not her secretarial skills and isn’t particularly interesting, although she does get to say one of the funniest lines in the movie: “Mr. Oxley’s been complaining about my punctuation, so I’m careful to get here before 9:00.” The first time Barnaby takes the formula, he leaves work in the middle of the day, so Miss Laurel is sent to find him, and they end up going out on an extended date. At one point, Miss Laurel kisses him on the cheek, but then he mentions his wife and she backs off disappointedly. So it’s relatively innocent “cheating,” if it can even be considered cheating at all, but that doesn’t stop Edwina from getting jealous – a feeling that is significantly heightened when she takes the formula, to the point that she tries to start a fight with Miss Laurel. Then younger Edwina seems to think she and Barnaby are on their honeymoon, but they end up having a weird fight that doesn’t really make any sense and she locks him out of their hotel room, at which point she calls their lawyer, Hank Entwhistle, played by Hugh Marlowe, who, it was revealed in their fight, kissed Edwina once, presumably years ago. We don’t get to see exactly what happens next, but the following morning Hank seems to think Barnaby is physically abusive based on what Edwina told him. So to summarize: men who feel young want to go out with pretty women, and women who feel young want to pick fights with their husbands and turn to a “friendzoned” man waiting in the wings. And this is reiterated when they take the formula again and act like actual children instead of young adults. Even then, Barnaby is drawn to Miss Laurel and Edwina is jealous of them, and after a fight with Barnaby, Edwina calls on Hank again. I’m not going to claim the way they portray this isn’t funny, because it is, but I don’t love that message, and that’s part of why I don’t love this movie as much as I used to anymore. There are a few scenes between “normal” Barnaby and Edwina where they talk things out that I think are actually pretty good, and it seems like they’re trying to show that a certain level of maturity is necessary for a healthy long-term relationship, which I think does make the message better, albeit amatonormative. I still think they could have made that point without being quite so sexist about it. Although it was 1952, so… maybe they couldn’t have.

There is also some blatant racism in this movie that I realize was common for the time, but that doesn’t make it okay. Child Barnaby overhears child Edwina calling Hank to come over, so he grabs a pair of pruning shears and rallies a group of (all white) neighbor children playing “Cowboys and Indians” to help him tie up and scalp Hank when he arrives. One of the kids informs Barnaby that they have to do a war dance first, and sing, so Barnaby organizes the kids into an “Indian choir” of sorts, and listeners… it is so painfully bad. On the one hand, from a historical perspective, it’s interesting to see how white American kids used to play in that era, but on the other hand, it’s just… no. I get that it’s supposed to be silly, but there are so many ways to be silly that don’t involve mocking Native Americans. A less serious complaint I have about that part is the next time we see Hank after he’s been tied up, part of his head has been shaved all the way to the skin, and there is no way the clippers Barnaby had could have cut anywhere near that close. And while I can easily suspend disbelief enough to accept a chimpanzee unlocking the secret of youth with a mixture of random chemicals, asking me to believe that pruning shears could shave a man’s head that closely is going way too far!

I also had a know-it-all phase when it bothered me that people often refer to chimpanzees as “monkeys” when they’re actually apes, but now I’m more in the “all words are made up to begin with and classifications of animals are especially made up, so who cares” camp. I guess that’s one way I can tell I’ve grown up and matured since the first time I watched this movie, without trying to use the ability to maintain healthy romantic relationships as a metric. But the more I learn about how animals – particularly apes – have historically been treated by the entertainment industry, the less I can enjoy seeing them in older movies. I haven’t heard any specific stories about Monkey Business in particular, but I doubt the chimps featured in it had very good lives, and that is yet another thing that makes it harder to enjoy this movie.

But despite all its problematic aspects and its relentless amatonormativity, overall I do think Monkey Business has a pretty good message about our society’s obsession with trying to stay young. After he and Edwina have both tried the formula, Barnaby has this to say about youth: “We remember it as a time of nightingales and valentines. But what are the facts? Maladjustment, near idiocy, and a series of low comedy disasters. That's what youth is. I don't see how anyone survives it.” And in the final scene, Barnaby concludes: “You’re old only when you forget you’re young.” The movie points out the importance of learning from experience to keep people from acting like fools who don’t understand consequences their whole lives. But it also shows that you can embrace getting older without completely abandoning the youthful joy that people and things you love brought you when you were younger. So the way I feel about this movie is remarkably consistent with its message. As I’ve grown and matured and learned more about the world, I’ve become more aware of its negative aspects, but that doesn’t negate the delight it brought me when I was younger, and having some problematic elements doesn’t make the movie all bad. Monkey Business reveals that life is more complicated than we think it is when we’re young, and youth is more complicated than we think it is when we’re old. Basically, life is messy, and there are no quick fixes, so let’s stop wasting time seeking perpetual youth and instead make the most of the life we have.

This does feel like a bit of a hypocritical message coming from Hollywood, which is famous for its obsession with youth and beauty. I do appreciate that this movie’s two main stars were both in their 40s – positively ancient by Hollywood standards, at least for an actress. In fact, at 41 years old (possibly only 40 at the time of filming), Rogers was the oldest leading lady to ever star in a Howard Hawks movie, which is incredibly upsetting. Grant would continue to play leading men for over another decade, and by this point in his career he’d already begun starring opposite women who were closer to Marilyn Monroe’s age than to his own (he was 22 years older than her), so it’s a bit refreshing to see him mostly paired with Rogers, who was only 7 years younger than him, with his attraction to Monroe portrayed as youthful infatuation that we’re not really supposed to take seriously. Marilyn Monroe herself perfectly embodied Hollywood’s ideal of youthful glamor, and it literally destroyed her well before she could make it to her 40s, so her presence in this movie really draws attention to the hypocrisy of its message. It would be great if the entertainment industry would actually take the movie’s advice and value age and experience rather than constantly worshipping (and thereby often ruining) youthful beauty, but as is so often the case, Hollywood released a movie with a decent message and then proceeded to ignore it.

Thank you for listening to my conflicted thoughts and feelings about this movie. I truly don’t know if anything I said made any sense to those of you who haven’t watched it, which I assume is most people, but I greatly appreciate you sticking with me anyway. Remember to subscribe or follow if you want to hear more, and rate or leave a review to let me know how you’ve been enjoying this podcast so far. Next week I will talk about the third and longest movie I watched 17 times, which is another fun, silly, obscure older movie, so I hope you’re enjoying these. And if you’re not, I hope you will continue listening anyway, I promise there are more recent and more well-known films coming up too. As always, I will leave you with a quote from the next movie: “How do you say in English ‘parachute’?”

8 notes

·

View notes

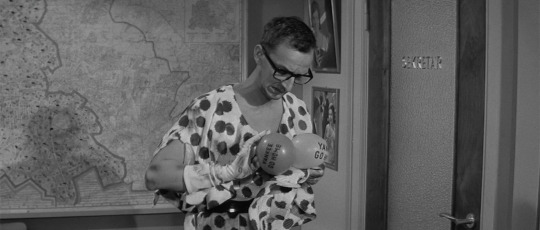

Photo

“So you just tell Daddy I'm on my way to the U.S.S.R. That's short for Russia.”

One, Two, Three, 1961.

Dir. Billy Wilder | Writ. Billy Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond | DOP Daniel L. Fapp

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fedora

Película tardía de Billy Wilder con I.A.L. Diamond de coguionista. Retoma el tema de la decadencia tan bien tratado en “Sunset Boulevard” en una historia y con unas formas que tienen todo el encanto y la redondez del mejor cine clásico.

Filmaffinity

0 notes

Text

Birthdays 6.27

Beer Birthdays

Charles von Buddenbrock (1878)

Ben Spencer (1974)

Five Favorite Birthdays

J.J. Abrams; screenwriter (1966)

I.A.L. Diamond; screenwriter (1920)

Emma Goldman; Russian anarchist, writer (1869)

Helen Keller; writer, lecturer (1880)

Willie Mosconi; billiard player (1913)

Famous Birthdays

Isabelle Adjani; French actor (1955)

Grace Lee Boggs; social activist (1915)

Charles Bronfman; Canadian billionaire, Seagrams owner (1931)

Audrey Christie; actor (1912)

Augustus de Morgan; English mathematician (1806)

Julia Duffy; actor (1951)

Lisa Germano; pop singer, songwriter (1958)

Bruce Johnston; rock musician (1942)

Khloe Kapri; adult actress (1997)

Bob Keeshan; "Captain Kangaroo" (1927)

Loretta Lynn; country singer (1959)

Tobey Maguire; actor (1975)

Frank Mills; pianist (1942)

H. Ross Perot; businessman, presidential candidate (1930)

Rico Petrocelli; Boston Red Sox 3B/SS (1943)

Frank Rattray Lillie; zoologist (1870)

Raul; Spanish soccer player (1977)

Kirkpatrick Sale; writer, historian (1937)

Vera Wang; fashion designer (1949)

0 notes

Text

Fedora

Billy Wilder’s FEDROA (1978) opens poorly. The scene of the title character’s (Martha Keller) death seems rather perfunctory, and the newscast describing her life feels phony, both as a dramatic device and in its staging. Then William Holden, as an aging Hollywood producer, arrives for the funeral and starts his off-screen narration, a cynical reminiscence in the vein of SUNSET BOULEVARD (1950) although this time he’s alive, and the film starts to take on a certain cachet. As a whole, the picture has the same mixed effect. Holden’s attempts to get reclusive former star Fedora to sign on for his next picture work dramatically. There’s a great gothic spin to her seeming captivity in a Greek island villa, where she lives with an aging countess (Hildegarde Knef), a forbidding companion (Frances Sternhagen) and her resident plastic surgeon (Jose Ferrer). And Wilder and co-writer I.A.L. Diamond have done a solid job of dramatizing the theme of being trapped within one’s assumed identity. Near the end, Holden suggests that the film would have made a better picture than the one he was peddling, and Fedora says, “But who would play me?” Therein lies the film’s greatest flaw. Fedora is an amalgam of Garbo, Dietrich and other exotic Hollywood stars, and though she could be a capable actress in other films, Keller just doesn’t have the charisma to convince as a star who remained an object of fascination even in retirement. She also has some mad scenes that are, shall we say, unfortunate. It’s a pity Wilder’s cynicism about all things Hollywood didn’t extend to the Hollywood version of insanity.

0 notes

Text

The Apartment (1960)

"Where will we go, my place or yours?"

"Might as well go to mine. Everybody else does."

#the apartment#billy wilder#1960#american cinema#films i done watched#I.A.L. Diamond#Jack Lemmon#Shirley MacLaine#Fred MacMurray#Ray Walston#Jack Kruschen#David Lewis#Hope Holiday#Joan Shawlee#Naomi Stevens#Johnny Seven#Joyce Jameson#Edie Adams#David White#Willard Waterman#Ooooof. I've been watching a lot of horror films lately (more even than my usual glut) and I was starting to feel like I needed a change#A palette cleanser if you will. And what better than a charming 1960 romantic comedy starring Lemmon and MacLaine??#Rarely do I find I've so badly misjudged a film. Not that this isn't good (it's brilliant) and not that it isn't funny (it's frequently#Very funny indeed) but it's just... The darkness. I wasn't expecting the darkness. There's this thick cloying sense of bleakness that hangs#Heavy over everything. Adultery bribery and suicide attempts. Full of glum asides and minor characters who go mostly unexplored but whose#Brief appearances all hint at larger and even sadder lives and stories. It ends beautifully and the two leads are very charming in a flawed#And very human kind of way and the rest of the cast are all great too (Kruschen in particular steals his every scene as perhaps the only#Decent person in the whole film) but yeah. Phew. A sometimes draining and emotionally complex experience

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Screenwriter I. A. L. Diamond was born on this day in 1920.

Pictured with collaborator Billy Wilder

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Apartment (1960)

"Some people take, some people get took. And they know they're getting took and there's nothing they can do about it."

Billy Wilder, the director who left Germany to build a career in Hollywood during the 1930s, had just scored a massive hit when he made The Apartment. Some Like It Hot, a transvestite comedy starring Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon, had broken records and is still considered one of the greatest comedies of all time. A much sadder and perhaps more relevant project, The Apartment is sometimes claimed to be one of the greatest films of all time.

Lemmon once again worked with Wilder to play C.C. Baxter, a lonely office clerk who spends his days on a huge office floor full of identical desks, stretching as far as the eye of the camera can see. We meet Baxter for the first time on that floor, anonymously among all the others, a nobody.

Hoping for a promotion, however, he rents out his flat to his bosses so they can take their “sweethearts” there. Baxter waits outside in the cold, a cigarette in his hands, until he can go back inside to clean up the empty bottles and the rest of the debris from other people's entertainment. He's probably one of the loneliest men we've ever seen in a movie (not considering the average Scorsese / De Niro movie), and this unfortunate soul doesn't even have the luxury of entering his own apartment to be lonely.

Baxter has a soft spot for elevator attendant Fran Kubelick, played by a young Shirley MacLaine, but he doesn’t know that she has long had a forbidden romance with the big boss, Mr. Sheldrake (Fred MacMurray). That affair has now arrived at an end - just as Baxter's manipulative superiors keep him hanging on with eternal promises of promotion, Sheldrake does so with Kubelick by assuring her that he will divorce his wife. But not yet, now isn’t a good time.

It’s striking how Wilder's filmography begins with two clearly divergent tendencies: in the 1940s he made either full on comedies or full on dramatic films (the fantastic film noir Double Indemnity or the alcoholism drama The Lost Weekend).

However, as he progressed further in his career, those two tendencies became intertwined. His comedies grew increasingly bitter, his dramas more witty, in a cynical way, until the two were barely distinguishable. The Apartment is an important film in that regard - it’s the first time that these humorous and tragic elements have merged so clearly and so seamlessly. The film would set the standard for all attempts in the genre that followed.

This is primarily due to a truly brilliant scenario by Wilder and his permanent collaborator I.A.L. Diamond. We never get the feeling that The Apartment suffers from sudden tonal changes between humor and drama, as each scene is designed to have an indispensable place in the structure of the film. It's an immense achievement to incorporate themes like the pursuit of success at all costs, adultery and even suicide into one and the same story, and still earn the title of comedy.

Jack Lemmon portrays one of the best roles of his career as C.C. Baxter, a somewhat naive, well-meaning man who is only too eager to believe that the woman he loves is the only one who hasn’t yet succumbed to the corruption he sees around the office. When he discovers that this is the case, his mentality towards her changes to one of disapproval, if not aversion.

Notice the way Lemmon plays that: a man who put his dream woman on a pedestal and now finds out that she isn’t perfect after all. Baxter is disgusted by the sneaky adventures his superiors experience in his own bed, but he takes part in it, because promotion is the only way he sees to change his situation. In order to not be lonely anymore, to stop being a loser who spends his evenings - when he is at home - alone in front of the TV with a bite-sized meal.

The reason why this kind of film doesn't seem to age, at all, is because the screenplay deals with universal themes: we still have pathetic office men walking around who dream of becoming more than what they are, and in order to achieve that unwillingly play in other people’s games. And of course we still have despicable bosses who treat the women in their lives as objects they don't want to be bothered with once they’ve had their fun.

Wilder decided to shoot the film in black and white widescreen. Black and white, especially as the story takes place over the holiday season (nothing as depressing as being alone on New Year’s), and the film's grey tones effectively strip this time of year of all the true joy that would lie behind it. And widescreen, to emphasize how cold and emotionless the world of Baxter is. We see him roaming long corridors, huge offices and huge streets as a little man, anonymously. It’s only when the action moves to the titular apartment that some life comes into the sets, and even then a certain gloom lingers.

For example, pay attention to small observations throughout the film. Lemmon using a tennis racket to drain water from spaghetti - that's a funny scene, but it also serves a purpose. This is a man who uses a racket to prepare food; ladies and gentlemen, this isn’t a man that often receives guests. Also pay attention to the way Lemmon, MacLaine and MacMurray great each other with their last names throughout the film, and very often with “Mr.” or "Mrs.". Apparently the straitjacket of the office stays in place, under all circumstances. It's that kind of detail that says a lot about the care that was put into this film.

A description of the plot and themes might suggest a depressing drama, but The Apartment is a film with many faces, and of the many things it is, it’s also a very witty film, with fun running gags, puns and one-liners. My favourite: Baxter's neighbour who is convinced that Baxter is a sex machine going by the sounds coming through the wall and asks him to donate his body to science should he die.

The Apartment was seen as a satire on the American dream at its initial release, and to some extent it certainly is. Wilder was one of the greatest satirists the film world has ever seen, with a healthy suspicion of all forms of authority. The Apartment is one of his very best films.

@idasessions @missdubois @mad-prophet-of-the-airwaves @purecinema

#had always wanted to see this one#and was able to watch it by surprise a couple of days ago#didn’t dissapoint#also have some reviews of a couple more recently released films planned#the apartment#the apartment 1960#60’s cinema#classic cinema#billy wilder#i.a.l. diamond#shirley mcclaine#jack lemmon#fred macmurray#comedy#drama#romance#movies#films#movie reviews#movie review#film review#movie analysis#cinema#filmista

46 notes

·

View notes