#i will admit to liking marryat

Text

It’s Frederick Marryat’s birthday very soon (10 July 1792), and I’ve been thinking a lot about the effect he’s had on my life: and just what is the nature of my fascination with this man. I think a huge part of being interested in Marryat is being drawn to the man himself, not just his stories and travel writing. You have to have some kind of personal investment in this bitchy, lecherous, sarcastic, self-righteous, frequently infuriating and problematic man; you have to care about him on some level. He feels extremely present in his writing.

I think Virginia Woolf expressed it well when she wrote in her essay on Marryat, “The Captain’s Death Bed”:

Often in a shallow book, when we wake, we wake to nothing at all; but here when we wake, we wake to the presence of a personage—a retired naval officer with an active mind and a caustic tongue, who as he trundles his wife and family across the Continent in the year 1835 is forced to give expression to his opinions in a diary.

Sometimes I wonder about what Marryat would think of me as his reader. In response to criticism in Fraser’s Magazine, Marryat wrote a long letter defending his work in cheap weekly newspapers which would be read by the lower classes (reproduced in The Life and Letters of Captain Frederick Marryat, edited by his daughter Florence Marryat). He starts out strong, attacking elitist attitudes about literature, and then shows his ass with smug pronouncements about how he’s writing wholesome fare to educate the lower classes, unlike trashy weeklies filled with “immorality and crime” that also teach people to criticize the government or read Chartists! (Marryat was a complex person whose views can’t be pinned down with modern political labels, but he wasn’t very progressive, not even in his own time.)

Marryat was my introduction to the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812, which have become major interests, he was my first real exposure to Regency-period fashion and manners, and he has increased my general nautical knowledge a hundredfold. I feel a kinship with him across time and space as he offers his opinions on the world of the 1830s and 40s, a bit jaded in middle age but still keenly observant and very confident in his opinions.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#shaun talks#he's one of those 'i wish i could study him in a jar' types (and i'd shake the jar too)#but i feel bad for him#this man was at war for a billion years starting from childhood#and it definitely messed him up#and he can be a genuinely good storyteller#complicated feelings for a complicated man#i will admit to liking marryat

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Patrick Brantlinger's book Rule of Darkness: British Literature and Imperialism, 1830–1914 has been a great asset to me in examining themes of imperialism, racism, and colonialism in Captain Marryat's works, as well as placing him in his context of Victorian cultural and literary history. It's slightly dated at this point (originally published in 1988), but still very relevant.

But Brantlinger unfortunately treats Marryat as primarily a writer for children, and he also just hates the guy. He tends to read him without nuance, flattens the moral ambiguity of his stories, and at one point he refers to Marryat's literary colleagues who were also ex-Royal Navy (Frederick Chamier, William Nugent Glascock, William Johnson Neale, etc.) as his SEAGOING CRONIES. (I put the book down and started laughing, at that point.)

There is a light-hearted anecdote in The Life and Letters of Captain Frederick Marryat about Marryat having some improperly cured animal hides on display in his home, which then attracted insects, as told by his daughter Florence—who clearly loved her father but was not above making fun of him. (After angrily insisting that nothing was wrong, Captain Marryat finally admitted the problem and sent the infested hides to be treated).

Brantlinger assumes that it is "perhaps some satisfaction for the modern reader" to learn about this incident, which also cracks me up. Like, there was no need to include this in a literary analysis, but he is just filled with glee to think of some embarrassment happening to Marryat.

#tbh brantlinger seething over marryat probably increases his importance in this book#...so a win for the captain marryat fandom after all?#reading marryat#frederick marryat#captain marryat#patrick brantlinger#rule of darkness#literature#every so often i find a good academic paper about marryat but nothing of this scope (alas)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I followed my new friend down the ladder, under the half-deck, where sat a woman, selling bread and butter and red herrings to the sailors; she had also cherries and clotted cream, and a cask of strong beer, which seemed to be in great demand. We passed her, and descended another ladder, which brought us to the ’tween decks, and into the steerage, in the forepart of which, on the larboard side, abreast of the mainmast, was my future residence—a small hole which they called a berth; it was ten feet long by six, and about five feet four inches high; a small aperture, about nine inches square, admitted a very scanty portion of that which we most needed, namely, fresh air and daylight. A deal table occupied a very considerable extent of this small apartment, and on it stood a brass candlestick, with a dip candle, and a wick like a full-blown carnation. The table-cloth was spread, and the stains of port wine and gravy too visibly indicated, like the midshipman’s dirty shirt, the near approach of Sunday. The black servant was preparing for dinner, and I was shown the seat I was to occupy."

(Frank Mildmay, or, The naval officer, Marryat)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Founding the Noah’s Ark Society To Save Physical Mediumship

http://ift.tt/2eGTFEY

It was back in 1990 (nearly 30 years ago now) that I personally founded the Noah’s Ark Society in order to help save Physical Mediumship which – at that time – actually looked set to potentially become totally or partially extinct.

One of the prime reasons for this was that many of the few remaining physical mediums who were demonstrating in public at that time were elderly; mostly deteriorating in health and therefore undertaking less and less work as their mediumships ‘wound down’. For instance: within the next four years, two of the best known physical mediums – Gordon Higginson and Leslie Flint both passed to Spirit. Several other well-known physical mediums, such as Maud Gunning and Geoffrey Jacobs had already passed to Spirit a little earlier as well. Some genuine physical mediums such as Rita Goold (who was working in a different energy-based way) had been forced to discontinue their mediumship due to alarming threats (including death threats) from anonymous ‘Arch Sceptics’ who – without any proof – accused them of fraud. Some excellent physical mediums like John Squires of Romford simply gave up because of health issues.

With the public’s increased general lack of access to séances and demonstrations of physical mediumship, therefore, and the lack of any exciting reports regarding encouraging contemporary results in this unique field of mediumship, it was perhaps inevitable that public interest in the subject would fade away. Instead of witnessing available demonstrations of physical mediumship (the publicity of which, naturally, would have generated considerable interest from scientists and the public), anyone seeking more knowledge and information (and since practical experience was sadly lacking), was forced to go to the history books for answers! I remember more than one person at that time remarking to me: “Physical Mediumship – isn’t that something that happened way back in time – but is no longer being practised?”

In 1989, my wife Sandra and I moved into a rented Church of England Rectory at Postwick – just a few miles East of Norwich. For many years, we had run our own home circles for the development of physical phenomena in the Romford area and had – in fact – actually met in a physical circle at Romford where the medium – John Squires – went on to develop the Independent Voice phenomenon (of an excellent quality) to almost rival that of Leslie Flint. My own interest as a researcher of physical mediumship goes back to 1972.

Once at Postwick, it was not long before I began to miss the home circles we had run and, although we did ask around the area, we never discovered any physical home circles locally who were looking for sitters at that time. Consequentially, a little later, we did once again start our own home circle at Postwick – but that is another story.

However – in the meantime – in March 1989, an advert for sitters in a physical circle at Ilkeston, Derbyshire appeared in the ‘Psychic News’. I replied, and agreed to meet the trance medium of that circle – Stuart Hellen and his wife Valarie for a chat. Although the circle was 130 miles away from Postwick, they had been asked by their Spirit Team to start a physical circle, running just once per month on the Saturday closest to the new moon. The travelling was therefore not too frequent and when asked – I was happy to join the circle.

In April 1989, I was present at their first proper physical phenomena sitting. Several raps occurred, together with psychic breezes, and ‘whistling’ was clearly heard over the singing of the group. Later in the year, after a few more sittings, I was able to arrange for the circle members to visit Leslie Flint, who I had known for several years. Through his Independent Voice mediumship, the group received confirmation of the work they were doing to develop physical mediumship, and much evidence concerning the circle. The well-known Victorian Novelist and Spiritualist Florence Marryat also became a regular communicator in the Ilkeston Group. Her book ‘There Is No Death’ is one I can highly recommend!

Stuart Hellen’s mediumistic development continued apace and – early in 1990 – at the request of the Spirit Team, Stuart’s chair was moved into a cabinet and, during this first ‘cabinet’ sitting, the circle were taken unawares when the initial attempt at Independent Voice took place. This phenomena continued to develop during the further sittings in 1990.

In late 1989, another advert had appeared in the ‘Psychic News’: for sitters to attend another physical circle – this time in Hove, near Brighton. Again (and I shall never know quite why!) I replied, despite the fact that this circle was actually 140 miles away from our home – in a totally different direction. This group was run by John Austin – a veteran Spiritualist – and his wife Gerry. They too knew Leslie Flint well. Although this was a weekly circle, I joined this group too. After sitting with the circle for a number of months, John and Gerry decided that they needed a new carpet for the lounge in which their sittings took place.

The manager of a local carpet warehouse called to measure up the room, and instinctively made the comment that he knew what that room was used for. ‘Seances!!’ There was no way he could have known this by normal means, so John and Gerry chatted to him about their interest. The result was that the young man – Colin Fry – was asked to join the circle. He agreed, and history was born!! It was not long before Colin’s physical mediumship took off, and he started to go into deep trance. In terms of physical phenomena, his development was quite rapid. Within months, advanced examples of physical phenomena were taking place and – by mid 1990 – it was apparent that he was going to be an excellent physical medium. I personally witnessed one of the first instances of his phenomena, when a coin was suddenly apported into the centre of the circle from the medium’s solar plexus. Later, when levitation of the medium became commonplace, he was once levitated – complete with chair – through a wall into the next room!

Meanwhile, back at the Ilkeston Circle in May 1990, it was on the anniversary of the inaugural meeting of the ‘Link of Home Circles’ (held in 1931 and attended by its founder – Mr Noah Zerdin) that a spirit personality communicated with us in the Independent Direct Voice. This was no less than Noah Zerdin himself, who had been a mentor to Leslie Flint in his early days, and many other mediums besides. He specifically asked us to “Start a Society which would educate the public about physical mediumship – ensuring its safe development, demonstration and practice – as well as generally promoting physical mediumship and its phenomena to the public”.

This, for us, was a very exciting development, and we quickly realised the significance of such a message, and the importance of actually implementing Noah Zerdin’s request. After the sitting, we sat round discussing the possibility of starting such a society. Since I had more experience in this specialist type of mediumship and its phenomena than the others, I agreed to take over the responsibilities and practicalities of putting the Society together, and badgered the other circle members to join me on the initial committee to help with the basic work (which involved an awful lot of diplomatic persuasion!!)

At that time, I was in a reasonable position financially and was able, therefore, to fund the society in its early days out of my own pocket. I came up with the name myself – The Noah’s Ark Society (I guess with a little help from Spirit), and commissioned an art studio in Norwich to produce a suitable logo. The name was suitable for three reasons:

1) The ‘Noah’ referred to Noah Zerdin, who had been the spirit communicator who asked us to start the Society.

2) Biblically speaking, ‘Noah’s Ark’ was a vessel that saved many species of animals

from their ultimate extinction. The Noah’s Ark Society aimed to save a particular formnof mediumship – physical mediumship – from extinction too.

3) The ‘Ark of the Covenant’ – biblically speaking – was a repository for psychic power and spiritual knowledge. That seemed particularly appropriate here too!

Over the next few weeks, I placed adverts regularly throughout the psychic press to notify the public of the new organisation. We sent out information sheets to interested people, detailing the aims and objects of the new Society, and inviting them to join the NAS. There was to be a monthly newsletter starting in August 1990 with issue number 1 and, although much preparatory work had been done before that date (including the rapid recruitment of members), it was generally accepted that the Society would be officially formed in that month.

The very first member – number 001 – was Stewart Alexander. He agreed to join the committee, and to be the ‘Archive Officer’. However, it was to be quite some time before he actually admitted to me that he was a physical medium himself! I started the Newsletter as planned, and edited it. In those early days it was produced by me on a photocopier (initially at my workplace, starting at 5.50am!!)

The first committee consisted of just the members of the Ilkeston Circle, together with Stewart Alexander. I did not want to take on the mantle of ‘President’ myself, preferring instead to remain as ‘General Secretary’, which allowed me to quietly get on with the building, expansion and running of the Society. It was agreed by all that the first ‘President’ would be the medium – Stuart Hellen. The first ‘Treasurer’ was Denise Lacey, another Ilkeston sitter. Apart from Stewart as ‘Archive Officer’, the rest of the committee was made up by: Stuart’s wife Valarie Hellen; Michelle Hackett; Mark Stanley and Jaquie Turner.

The psychic press reported and trumpeted the details of the new Society. Because of that; our adverts, and ‘word of mouth’ generally, the NAS membership grew rapidly over the first few months. Physical Circles from all over the world joined as well, together with dozens of individual interested people and researchers. We quickly surpassed the significant benchmark of 100 members, and approached 200. All of a sudden, it became clear that as well as the committed physical circles and researchers already involved in our specialist subject, there was also – amongst those who had never come across physical mediumship themselves before the advent of the NAS – a new, and massive interest in physical mediumship and its phenomena from the general public, many of whom were totally lacking ANY knowledge of the reality of physical phenomena. The NAS, therefore, provided a rallying point for interested people. We set out a programme of education so that everyone could learn the basic facts – and so that members who had not previously done so could witness demonstrations of physical mediumship themselves on a regular basis.

I wrote an NAS teaching guide on the ‘Development of Physical Mediumship and its Phenomena’, based on the traditional use of ‘ectoplasm’ (at that early stage, nobody knew that excellent phenomena could be produced using only ‘energy’. The ‘Scole Experiment’ and its work came later!!) This, like the Newsletter, was produced in large numbers by me on my works copier machine, with a copy of this teaching booklet being sent out free to all members – together with Newsletter number 2 in September, 1990.

Over the next few months, the NAS continued to grow at a rapid rate, and the contacts that we made through the Society proved to be most useful. At a general meeting in January 1991, veteran medium and researcher Alan Crossley was elected as the new ‘President’, and I became ‘Chairman’ of the Noah’s Ark Society – a position I held until Sandra and I withdrew from the NAS in September 1994 (at the specific request of our Scole Spirit Team), to concentrate on our work with the Scole Experimental Group, which was producing some really amazing and exclusive Physical Phenomena – working in a brand new ‘energy-based’ way.

At a residential Seminar in Leicester in May (with almost 100 people present), the very first NAS demonstration of Physical Mediumship took place, using medium Colin Fry (at that time identified simply as ‘Lincoln’). It was a huge success and – Stewart Alexander (who was present) recognised the importance and full impact of such a public demonstration. He was immediately motivated to offer to undertake similar public demonstrations for the NAS in the future so – for many years, members were able to witness demonstrations of physical mediumship by these two superb mediums.

Stewart Alexander later took over as ‘President’ of the Noah’s Ark Society. The last ‘President’ – the late George Cranley – engineered the closing of the NAS in 2004. The ‘Vice-President’ at that time was the late Colin Fry – a really superb Physical Medium.

It is quite clear today that there is now a massive interest in Physical Mediumship and its Phenomena all over the world. Newer (and often younger) physical mediums are developing and coming on to the scene in so many different countries. I have no doubt personally that the work of the Noah’s Ark Society and the later work of the Scole Experimental Group have contributed tremendously to that interest, and motivated a large number of those emerging physical mediums to develop their own mediumship and phenomena.

In conclusion, therefore, I think I can justly claim that the ‘Noah’s Ark Society’, which set out to ‘save’ Physical Mediumship and its Phenomena achieved (in part) exactly what it set out to do. The subject (and practice) of PM today is thriving; continuing to expand constantly. Therefore it is far more commonplace (and available to the public) than it used to be. Interest in this specialised subject indeed continues to grow at a rapid rate.

Author information

Robin Foy

Robin Foy is best known for his work with the Scole Experiment and is considered one of the original pioneers in physical mediumship using new energy based methodology. He is the author of several books on physical mediumship and is a true expert.

|

from The Otherside Press http://ift.tt/2pO76J8

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

A lawyer walks into a bar

Q: My question, should you care to consider it, is which came first—the “bar” where attorneys work or the “bar” those attorneys may frequent after work?

A: We briefly mentioned the connection between one “bar” and the other in 2014, but we didn’t go into detail. To make a long story short, the “bar” at which you practice law came before the “bar” at which you drink.

Etymologically, however, they’re the same word. So here’s the longer story.

The noun “bar” (first spelled “barre”) came into Middle English in the 1100s from the Old French barre, which acquired it from the late Latin barra (“bar” or “barrier”).

In English, the word’s original meaning was “a stake or rod of iron or wood used to fasten a gate, door, hatch, etc.,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary. All other senses of the word are derived from that.

Today the noun “bar” has three overall meanings, roughly having to do with its physical shape, its purpose, and the area it defines.

So broadly speaking, the uses of “bar” fall into these categories: (1) something, like a rod or band, that’s longer than it is thick or wide; (2) something that obstructs or confines, like the related word “barrier”; and (3) a place defined by a rail or barrier.

That third group of meanings explains the use of “bar” in reference to the courtroom as well as the saloon. Various legal meanings date from the early 1300s, the OED says, and the drinking sense from around 250 years later.

The earliest known “bar” in the courtroom sense indicated “the barrier or wooden rail” separating the judge’s seat from the rest of the court, the dictionary says. This was where the barristers, litigants, prisoners, and others stood to address the judge.

In the reign of Edward I, when French was still spoken in English courts, the term “a la barre” was recorded in two legal documents dated 1306, according to the online Middle English Dictionary. Soon afterward the term was Anglicized, “at (or to) the bar.”

In the first recorded English use, this “bar” was “the place at which all the business of the court was transacted,” and the term soon became synonymous with “court,” according to the OED. So “at the bar” meant “in court.”

The dictionary’s earliest quotation is a reference to “countours in benche that stondeth at the barre.” (In Middle English, “countours” meant “pleaders.” The source here is a 1327 collection of political songs.)

In the sense of “bar” as the place where a prisoner stands for arraignment, trial, or sentence, Oxford‘s earliest example is from an indefinite time in the 1300s:

“Brynge forthe to the barre that arn to be dempt.” (The word “dempt” meant “condemned.” This is from a cycle of medieval mystery plays, Ludus Coventriae.)

Quite early on, the word was used figuratively to mean any kind of tribunal, as in this OED citation from the Wycliffite Sermons (circa 1375):

“Ech man mote nedis stonde at þe barre bifore Crist” (“Each man must needs stand at the bar before Christ”).

In the mid-1500s, “to be called to the bar” first meant “to be admitted a barrister,” the OED says. (A “barrister,” first spelled “barrester,” was a person called to the “barre.”)

Originally, however, this particular “bar” was in the classroom, not the courtroom. Here Oxford explains what “bar” meant to law students at the Inns of Court in the 1540s:

“A barrier or partition separating the seats of the benchers or readers from the rest of the hall, to which students, after they had attained a certain standing, were ‘called’ from the body of the hall, for the purpose of taking a principal part in the mootings or exercises of the house.”

After 1600, this was “popularly assumed to mean the bar in a court of justice.” In an OED citation from 1650, “call’d to the Barre six yeares agoe” means qualified to practice law six years ago.

“The bar” also began to mean barristers as a group in the mid-1500s, and within a century it was used for the profession itself. The term “bar association” originated in the US in 1824, the OED says; the American Bar Association was formed in 1878.

All this has made us thirsty, so let’s move on.

The “bar” meaning the place where one goes to drink came along in the late 1500s, and here again it originally implied some sort of barrier.

This is the OED‘s definition: “A barrier or counter, over which drink (or food) is served out to customers, in an inn, hotel, or tavern, and hence, in a coffee-house, at a railway-station, etc.”

This “bar” also means “the space behind this barrier, and sometimes the whole apartment containing it,” according to the dictionary.

The earliest Oxford citation is from Robert Greene’s “The Third and Last Part of Conny-Catching,” a 1592 pamphlet in defense of cheating and petty theft:

“He was well acquainted with one of the seruants … of whom he could haue two pennyworth of Rose-water for a peny … wherefore he would step to the barre vnto him.”

Here’s a handful of later examples:

“[I] laid down my Penny at the Barr … and made the best of my way to Cheapside.” (Joseph Addison, the Spectator, 1712.)

“He sees the girl in the bar.” (Frederick Marryat’s novel Jacob Faithful, 1834.)

“A bottle of champagne quaffed at the bar.” (From the American notebooks of Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1837.)

We mentioned above that “bar” can be traced to the Late Latin barra, but nobody seems to know where barra came from. The OED says it’s “of unknown origin.” And with that, unfortunately, the trail goes cold.

It may be true, as some have suggested, that the ultimate source is Aramaic, a wide family of related Semitic languages and dialects.

An Aramaic preposition pronounced “bar min” (transliterated as br mn), means “except for,” “aside from,” or “outside of.” But we haven’t found any evidence of a connection.

Help support the Grammarphobia Blog with your donation.

And check out our books about the English language.

from Blog – Grammarphobia http://www.grammarphobia.com/blog/2017/04/bar-2.html

0 notes

Text

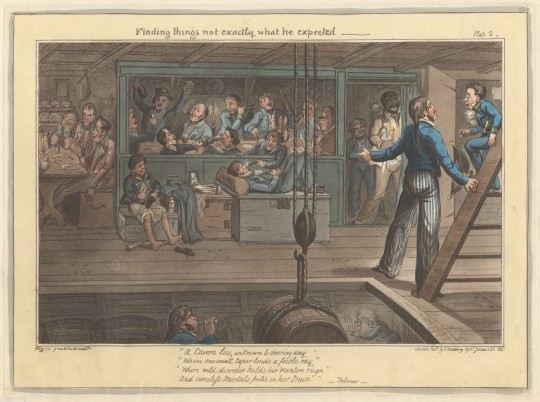

'Finding things not exactly what he expected', the second plate of The Progress of a Midshipman Exemplified in the Career of Master Blockhead in Seven Plates & Frontispiece, engraved by George Cruikshank after sketches by Captain Frederick Marryat. These 1820 caricatures are like an early version of Frank Mildmay's introduction to the midshipmen's berth, in Marryat's 1829 novel:

I followed my new friend down the ladder, under the half deck, where sat a woman, selling bread and butter and red herrings to the sailors; she had also cherries and clotted cream, and a cask of strong beer, which seemed to be in great demand. We passed her, and descended another ladder, which brought us to the 'tween-decks, and into the steerage, in the forepart of which, on the larboard side, abreast of the mainmast, was my future residence—a small hole, which they called a berth; it was ten feet long by six, and about five feet four inches high; a small aperture, about nine inches square, admitted a very scanty portion of that which we most needed, namely fresh air and daylight.

— Frederick Marryat, The Naval Officer (Frank Mildmay)

The new midshipman is horrified by the smoky, dark, foul-smelling steerage of the ship: "all conspired to oppress my spirits, and render me the most miserable dog that ever lived."

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#age of sail#royal navy#midshipmen's berth#frank mildmay#george cruikshank#midshipman monday#naval history#midshipman#art#the progress of a midshipman

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In a novel, sir, killing’s no murder"

A portrait of Captain Marryat circa 1830, and what he might have looked like when fielding some harsh questions about his last novel, The King's Own, which he describes in the opening chapter of Newton Forster.

The unbought critics have some complaints familiar to writers of today. Marryat is too lurid and violent for their tastes, and does he condone the behaviour of his fictional characters?

One gentleman doesn't like the violence in particular:

“I don’t like your plot, sir,” brawls out in a stentorian voice an elderly gentleman; “I don’t like your plot, sir,” repeated he with an air of authority, which he had long assumed, from supposing because people would not be at the trouble of contradicting his opinions, that they were incontrovertible— “there is nothing but death.”

“Death, my dear sir,” replied I, as if I was hailing the look-out man at the mast-head, and hoping to soften him with my intentional bull; “is not death, sir, a true picture of human life?”

“Ay, ay,” growled he, either not hearing or not taking; “it’s all very well, but — there’s too much killing in it.”

“In a novel, sir, killing’s no murder, you surely will admit; and you must also allow something for professional feeling—’’Tis my occupation;’ and after five-and-twenty years of constant practice, whether I wield the sword or the pen, the force of habit—”

“It won’t do, sir,” interrupted he; “the public don’t like it.”

Although Captain Marryat was employed to suppress smuggling in the English Channel, his sympathetic depictions of smugglers are another target of attack:

“If I might presume upon my long-standing in the service, Captain — ,” said a pompous general officer, — whose back appeared to have been fished with the kitchen poker— “If I might venture to offer you advice,” continued he, leading me paternally by the arm a little on one side, “it would be, not again to attempt a defence of smuggling: I consider, sir, that as an officer in his Majesty’s service, you have strangely committed yourself.”

“It is not my defence, sir: they are the arguments of a smuggler.”

“You wrote the book, sir,” replied he, sharply; “I can assure you, that I should not be surprised if the Admiralty took notice of it.”

“Indeed, sir,” replied I, with assumed alarm.

I received no answer, except a most significant nod of the head, as he walked away.

— Frederick Marryat, Newton Forster

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#1830s#english literature#british literature#newton forster#the king's own#criticism#ngl marryat getting yelled at over 'the king's own' is satisfying to read#yeah fred you DID kill too many people off

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

With today being USA Thanksgiving, and I am American and home for the day, I have been combing through Captain Marryat's Diary in America for appropriate anecdotes.

Although the Thanksgiving holiday was celebrated in the US in the late 18th century, according to several minutes of online research, it wasn't officially a national holiday until the late 19th century, and only in the 1940s did it move to its current fixed date of the fourth Thursday in November. So it's not surprising that Marryat missed attending a Thanksgiving feast, despite spending almost two years in the USA and parts of Canada.

Although Marryat wrote that at urban American markets, "the wild turkey is excellent", he added that "the great delicacies in America are the terrapin, and the canvas-back ducks." A turkey was on the menu during part of his travels, however:

When I was on board one of the steam-boats, an American asked one of the ladies to what she would like to be helped. She replied, to some turkey, which was within reach, and off of which a passenger had just cut the wing and transferred it to his own plate. The American who had received the lady’s wishes, immediately pounced with his fork upon the wing of the turkey and carried it off to the young lady’s plate; the only explanation given, “a lady, Sir!” was immediately admitted as sufficient.

— Frederick Marryat, Diary in America (published 1839)

I wouldn't recommend trying this at the family table, even if "a lady" wishes to be served first.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#diary in america#thanksgiving#american thanksgiving#turkey#food#foodways#what is with 19th century people and their obsession with eating turtles#1830s#the time period is relevant#but the book holds up as a mirror of america even 180 years later

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

🗣️ for Marryat and/or 🌟 for Le Vesconte?

🗣️: for a quote about them

🌟: for the “best of” / best moments

Maybe I am misinterpreting this, but I have the option to do these for both of them?

Quote about: Frederick Marryat. I will never get over this passage from Oliver Warner, who I think had a great understanding of him:

Marryat was anything but a saint, as might have been expected in one who was encountering his country’s enemies in bloody hand-to-hand fights at an age when, today, he would only just have left his preparatory school. He cannot, in fact, be judged by contemporary standards, though there are passages in his life which admit of no praise, judged by any other. But he was a man, with the imperfections to which men are heir, and he was quite unlike anyone else, either of his own or of a later time. Greatly gifted, largely uncontrolled, once he had left the sea for the perils of life ashore he sometimes ran amok.

Quote about: Henry T.D. Le Vesconte. Those of us who have read William Battersby’s Fitzjames biography, does it get any better than, “The 1st Lt, Le Vesconte, is just the man for me and I don’t think we are in bad order.”

Another favourite quote about Henry Le Vesconte is also from James Fitzjames, in his journal-letter entry for 6th July 1845 (as printed later in the Naval Chronicle): “Le Vesconte and I on the island since six in the morning, surveying. It is very satisfactory to me that he takes to surveying, as I said he would. Sir John is much pleased with him.” I love how Fitzjames feels his confidence in Le Vesconte is rewarded: he knows this guy is a big nerd, detail-oriented and mathematically gifted, of course he’s going to get along with a theodolite and do a great job surveying. And Sir John Franklin praising his competence as well!

Best of moments: Frederick Marryat. I’m going to say his creation of Frank Mildmay, the novel and the character. There’s a whole lot of Frederick in Frank, in case the name alone wasn’t obvious, but he transcends his creator and he’s a bonafide Byronic hero. He’s a victim and a perpetrator, a compelling character, a heartbreaker and flirt, he’s a fascinating and awful person who would have a prestige TV miniseries if there was any justice in the world.

Best of moments: Henry T.D. Le Vesconte. I’m going to interpret this in two ways. Highlights of his life? Definitely the time he was Fitzjames’ second on Clio. He clearly enjoyed the exotic travel aspect of it, liked Fitzjames, and really liked being the first lieutenant (specifically mentioning it in letters to his father). Best of moments: from my transcriptions of Henry’s letters. That time he cursed out an old shipmate with the amazing oath, “may his potatoes never be meaty or his pigs get fat” (from a letter to his father from HMS Excellent dated Dec 24 1836, the whole thing is solid gold).

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#henry le vesconte#henry td le vesconte#henry thomas dundas le vesconte#franklin expedition#historical figure emoji meme#ask#asks#lmk if you want the finding references for the le vesconte letters!#this is the provincial archives stuff in newfoundland#biography

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

My personal knowledge of the 19th century British historian, writer, and public intellectual Thomas Carlyle is limited to an attempt to read Sartor Resartus when I was about 12, for unknown reasons. I was already deep into Victorian weirdness at that age, and somehow I heard of Carlyle and decided to read that of all books. (I don't think I got very far, Carlyle was no Charles Dickens).

But there's an anecdote about Carlyle reading Frederick Marryat that I can't stop thinking about.

When Carlyle's housemaid accidentally burned part of the manuscript he was writing, he dealt with the blow by taking time off, distracting himself by reading favourite authors. (Oliver Warner, Captain Marryat: A Rediscovery p. 192) Carlyle described these books as something like, "Captain Marryat and other trash" in his correspondence.

A modern biography of Thomas Carlyle (Moral Desperado by Simon Heffer) tells it this way:

Instead, Carlyle sought other forms of relief, still reading what he called 'the trashiest heap of novels', including some by Captain Marryat.

On the one hand it's a withering slam of Marryat's literary quality, literally calling him trash; but on the other hand, it makes him look like a very tempting kind of junk food. Even if Marryat isn't very respectable, this leading intellectual admits to indulging in his books for comfort.

I really empathise with Carlyle here—I constantly try to read Serious books about my interests, only to return to re-reading Marryat. (It doesn’t help that my phone is full of Marryat’s writing, a click away at all times).

He was a pioneer of serialised fiction published in magazines (according to Louis J. Parascandola); and his habit of intruding in his narratives with personal anecdotes and opinions can sometimes make Marryat read like cliche fanfiction. (I don't think most fanfic authors are as chatty with the reader or as melodramatic as Captain Marryat). I try to approach Marryat critically, but he’s still a guilty pleasure.

#thomas carlyle#frederick marryat#literature#19th century#british literature#reading marryat#captain marryat#oliver warner#louis j. parascandola

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Thus it is with proud man. He struggles to conceal effects arising from feelings which do honour to his nature; but feels no shame when he disgraces himself by allowing his passions to get the better of his reason—and all because he would not be thought womanish! I'm particularly fond of crying myself.]

I would like to dig into this quote from The King's Own, so typical of that novel in the way it mixes events in the book with Frederick Marryat breaking the fourth wall. The context in the story is the smuggler M'Elvina surrendering young Willy Seymour, whom he has cared for like his own son, to the captain of an English frigate. It's a better life for Willy, but M'Elvina is heartbroken and attempts to hide his tears.

The "I" is Marryat himself— he is the one who admits to enjoying a good cry. I admit that I was surprised to read that, because despite the copious evidence of Marryat being a highly emotional person, I didn't expect him to freely confess that he often cried. (And then I felt bad for making an assumption based on the same kind of toxic masculinity tropes that Marryat railed against.)

I don't think it's generally appreciated how much Marryat writes caring, nurturing male characters.

#captain marryat#frederick marryat#masculinity#the king's own#i have so many thoughts on this book in general!!#reading marryat#eta: text transcription

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frank Mildmay, the wrap up

My schedule makes it difficult for me to do any kind of writing; but in this case a few days of reflection and cross-referencing things in Marryat's biography was helpful.

Pretty much everyone who has read Captain Marryat's novels for adults has assumed that they are autobiographical, although Marryat always denied it. His Victorian biographer David Hannay even makes assumptions about Marryat's childhood and his relationship with his father based on Frank Mildmay in particular.

Not only does Frank Mildmay have life experiences that track closely with those of the real-life Frederick Marryat, but like Jack Easy, he shares a physical resemblance to his author: tall and manly with curly dark hair. (Marryat's wavy hair may not have had a very defined curl, but he was clearly proud of it.)

As I detailed in an earlier post, I found out that Marryat was at the Battle of the Basque Roads thanks to Frank Mildmay. But I also I saw the error in reading Mildmay as a Marryat expy all the way. In one memorable chapter, young Mildmay is devastated by the news that his mother has died and he travels home to his family in despair, determined to leave the Royal Navy. It’s a jarring change of scene when he arrives home to find his siblings dancing to piano music and playing with friends; even his father is happy. His family has had six months to process his mother’s death before the post reached Mildmay.

I immediately wondered if Marryat’s mother had died young when he was at sea, but she outlived her famous son and died of old age. There are many parts of the book that appear to be Marryat writing of his own experiences, but it’s not like the man can’t come up with purely fictional drama.

I’ve seen complaints that this book doesn’t have enough Napoleonic wars content, but tbh young Mildmay’s impression of his warship is an invaluable first-hand account of the living conditions and what it looked like and smelled like. Like most Marryat novels it’s full of Age of Sail action with the verisimilitude that only a real sailor of the period can write; and I don’t see anything wrong with the diversions in the plot that people also complain about. I think that if the books were confined to the ships and naval warfare they would be a lot less fun and exciting.

Marryat goes into vivid detail about what he knows from direct experience and doesn’t pretend to have had a grand overview of battles where he only saw death and chaos as a young teen. In Frank Mildmay he writes of the Battle of Trafalgar, “The history of that important day has been so often and so circumstantially related, that I cannot add much more to the stock on hand. I am only astonished, seeing the confusion and invariable variableness of a sea-fight, how so much could be known.”

If my heart broke over anything in particular in this book, it’s the part where Mildmay confesses after the death of several siblings that he has been fucked up by his war experiences and no longer processes grief or sees death like a normal person. It rang true in a raw kind of way. But he’s not unfeeling, and I was gratified that he became close to his surviving sister and repaired his relationship with his father.

David Hannay seems to think that Marryat was distant from his father because of how he sees the relationship between Frank Mildmay and his dad, but I actually thought that Frank had a rich and complex relationship with his father, and overall not a bad one despite some rocky moments. At the end of the book it seemed like Frank and his dad were completely reconciled and happy to be in each other’s lives. (I liked that part a lot-- that and Lieutenant Talbot surviving.)

Frank Mildmay started off strong, some truly sparkling writing and very funny jokes, but it lost steam towards the end. Not coincidentally the title character has to start his moral arc upwards and repent from his scandalous ways. I know that Frank Mildmay is not Frederick Marryat: but at this point I definitely suspect that Captain Marryat had several hundred dozen illegitimate children. I mean Mildmay fucks, a lot. Marryat has to use some evasive period language to describe this; but the language is not that evasive and I’m more than a little scandalized by fuckboy Mildmay.

Poor, tragic Eugenia has to die with her curly-haired illegitimate son (which was sad but I expected it.) But what about poor Carlotta? Welp, “As for Carlotta, I learned afterwards that she went on board every ship that arrived, to gain intelligence of me, who seldom or ever gave her a thought.” Mildmay loses respect for any woman who has sex with him, and while he admits that he’s wrong it’s no less shocking.

Overall I loved this book a lot. Even if it reflects some problematic attitudes it has, somehow, more moral clarity than Mr. Midshipman Easy and its anti-equality message. (And way less racist language although some slurs and racist language are still used.)

4 notes

·

View notes