#holstein gate

Text

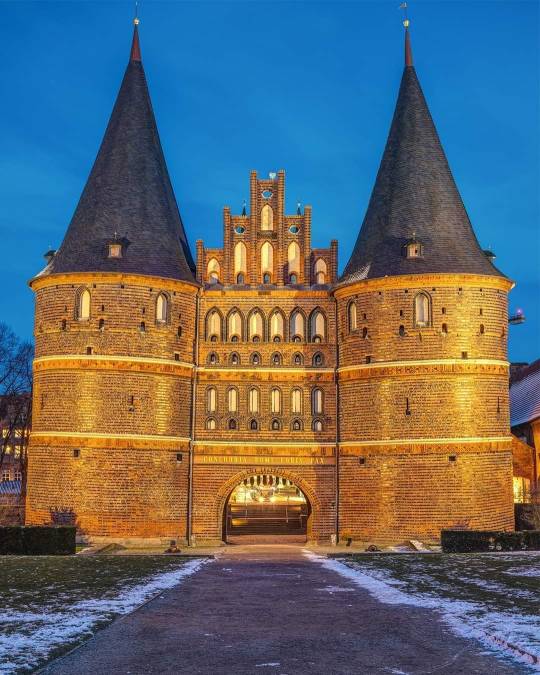

Museum Holstentor in Lubeck, GERMANY

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tor in der Stadtmauer, Lübeck, Schleswig-Holstein, 1972

#cityscape#wall#gate#brick#people#automobile#lübeck#schleswig-holstein#deutschland#1972#photographers on tumblr

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lubecca (2) (3) (4) (5) by Claudio e Lucia Images around the world

#towers#gates#buildings#gothic architecture#brick gothic#churches#statues#houses#cobblestones#germany#lübeck#schleswig holstein

0 notes

Note

Followed your blog a few years back even though it wasn't active because I absolutely love it and have gone through it more than once. It was an awesome surprise to see you posting again! In celebration I now have a personal breeding story to tell you.

Some background is that when I got back into horses in 2019 turns out I made the wrong choice on who to go to, but I fell in love with a horse there and now can't leave her, so to cope I like to tell anyone who might be interested about the shit show I am experiencing.

The owner/trainer of the barn was given a horse that had originated from some hunter/jumper barn where they had ridden her over huge jumps at 4 years old and very clearly handled her harshly. When she didn't stay sound and developed behavioral problems they dumped her at a YMCA camp and some people who work there then gave her to the trainer. She tried to put her back in work but she was eventually deemed "unridable". She has behavior problems both in and out of saddle, she would be very difficult to lead, and just bomb through gates and in and out of stalls, she will also be fine for a long time then one day suddenly bite very hard. I'm absolutely sure most of this is due to pain or past pain. Besides having been ridden hard as a youngster she also has a tragic back end. I'm hoping I'm describing this correctly but she basically has no croup. Her topline is just flat from the end of her withers to her tail. Because of this she almost always cross canters behind.

So, my trainer has a youngish, unridable, horse with big movement but problematic conformation, behavioral problems, and some kind of pain that prevents her from being truly sound. So what does she decide to do? Breed her of course!

For you see, although she has no paperwork, she *supposedly* has warmblood in her! Actual warmblood, perhaps holsteiner or something similar. She apparently is registered with the "american warmblood association" which I know you know means nothing. The horse I ride could also be called an """american warmblood"" and I love her with all my heart but she is literally just a draft cross. So this means she must be a great sperm receptacle, because that's all mares are right? They aren't literally half the DNA of the foal right?

Luckily the first year she tried it didn't take, if only the story ended there.

Now, this was something that my trainer "always wanted to do" and I am relatively understanding to someone who in their whole horse career wants to have one home bred foal, the market is insane and it is a unique experience and sometimes they are very attached to the mare etc etc. Not something I encourage but I don't think you are the absolute worst if you do this. This is not actuall what my trainers ambition wound up being though.

Fast forward to 2022 and the trainer's friend has decided she wants to breed her completely average thoroughbred mare, with no accomplishments to speak of, and picks out a different stallion than the one my trainer had already tried. He is a Westphalian stallion and he is Cremello! Because she wants a buckskin! So trainer's horse and friend's horse get sent down to this guy.

In the meantime, trainer's riding horse, an OTTB, is having training problems (doesn't like jumping down into water, which is required in the higher eventing levels) and is not staying sound. So what does she decide to do with her? Breed her as well! Because soundness issues can never be genetic.

So this person who has never worked with baby horses has decided to have two for their very first time.

AI doesn't take with OTTB so she gets sent down to the Westphalian too. All three horses do get successfully pregnant.

Keep in mind this is a small barn that is already wildly overcrowded, with generally unsafe conditions and no proper unused area for babies and moms to live.

Fast forward again almost a year and babies are born a couple months apart, trainer goes out of town both times literally as the mares are about to pop. "Warmblood" mare waits until she gets back but OTTB gives birth literally the day she goes out of the country for two weeks with a tween watching her farm. I also happened to be there when she gave birth which was a very cool experience but still ridiculous.

"Warmblood" mare is a good mother, but as you may remember is not actually that easy to handle, which can make it also difficult to handle the baby. OTTB is good with people but aggressive towards the baby especially around food. (Just of a side note both came out Palamino)

So since, completely unpredictably, they are having trouble working with the "Warmblood"'s baby because of the mom they decide to wean him at THREE MONTHS. Even the industry standard of 4-6 months has come into question lately because of the evidence of how bad it is for horses. OTTB weans at between 4-5 months because of the aggression towards the baby.

"Warmblood" gets sent back to the same stallion almost as soon as the foal is weaned, and OTTB is given AI while the foal is still with her because apparently we have decided we are a breeder now and need to have foals every year! Luckily, neither of them take ( and we get to hear about "Wasted money" ) probably partially because the mares aren't in amazing condition, as they have not been getting unlimited food and even often run out of water because the owner and the kids feeding just forget to fill up buckets. 😊

Now Westphalian is not as strict as other warmblood registries, but they are an actual breed and they do have one, which means inspection. Somehow, it winds up actually being hosted at our barn. When I tell you how ridiculously embarrassing it is to have someone come all the way from Germany to this absolute hole of a barn.

When the "Warmblood" mare gets inspected they mention her unfortunate hip anatomy, and also ask why the hell the foal was weaned already. Everyone passes though, not the highest grade but still registered and the foals get their brands and everyone gets their DNA tested. While this is happening the American from the registry actually says something to my trainer about how the "Warmblood's" conformation is going to be a problem in future breeding.

After they have left trainer asks "Wait were they saying not to breed "warmblood"? But why if her foal was fine?" First yes, yes that is exactly what they were saying, second it is only by pure chance her foal didn't inherit that butt, you can't pick a choose what the foal gets no matter how fancy of sperm you buy. They proceed to say they were a little snobby even though they were way nicer than they needed to be. Also they wouldn't brand the wood in the barn which I thought was hilarious. Trainer decides AFTER the inspection to finally actually get "warmblood"'s papers?

So now both mare's are just sitting and foals go out together with one halflinger in a tiny mud pit. "Warmblood's" foal has started showing some behavioral problems. I haven't had trouble, he basically just has a constant grumpy face, but he has bitten and tried kicking other people. This obviously could never have been predicted when you knew his mother had problems and then weaned him incredibly early emotionally stunting him! He's going to be a big fucker too. OTTB's foal is an angel but loose with those back legs lol. There is someone who really wants her who used to ride at this barn and rode her mother, then moved to a better barn and I hope she gets to have her because she will spoil her and give her a good life.

They both have big ole worm bellies too! Because the manure management is non existent in the pastures and they didn't get wormed at all until this week (maybe). I'm attaching pictures of the "warmblood" mare so you can see what I mean about her hind end. I actually like her a lot and wish I could help her.

I hope you "enjoyed" this story, it has been painful for me to live through. I just thought it exemplified so many things this blog is all about.

Good to see you back and I hope you're doing well!!!

Oh I was not prepared for the pictures. That's... not good. Thank you for being sensible and reporting back from hell on earth.

#roach back#so much sympathy for those poor germans#something freaky going on with her hip too i'm not surprised her back end movement is weird#toplines so bad they're arguably deformities. this should be a pasture pet absolutely not breeding stock

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

act four.

Romanov/Crown Prince later(Tsar)!Timothee Chalamet x Princess!Reader

main masterlist

let others wage war masterlist

act i,ii,iii

previous

summary: now engaged, you begin to prepare for the life that awaits you, while realizing and processing the loss of a sister to the same fate - marriage.

word count: 2.4k words

note: I know marriage is a common theme if not the main theme in this story, not only because of romance but because of how significant it was to women's lives. I wanted to tell their stories and what it would have been like to give up everything for love, for duty and your country.

not only did things have consequences on who you would marry, it would influence global politics and create a domino effect like no other especially for a royal dynasty like theirs. enjoy!

“Mere existence had always been too little for him; he had always wanted more."

Crime and Punishment (1866), Fyodor Dostoyevsky

"Do you think Alix is angry with me?" Minnie walks arm in arm with her statuesque father, strolling without rush in the lush green garden.

The smell of freshly watered grass stuck to their hems, as father and daughter enjoyed the whiffs of chilly autumn breeze brushing against their skin even under the cloudless sun.

As war waged on in your nation, the Second and Third Schleswig Wars waged on in Denmark and into the outskirts of Germany as the Schleswig-Holsteins threatened to steal at least two thirds of your country’s land mass. Seeing the tired, hollow shadows underneath your father’s eyes, you contain your anger and hatred for the Germans for what they had done to little, old Denmark.

They took advantage of your nation’s fledgling status, the political and constitutional uncertainty that came with succession crises. Leaving your dear Alix alone in the company of Germanophiles scares you, how she would be left alone and forced to renounce her country, her tongue, her identity for the man she is marrying and the country she will become queen to.

"She would never be angry with you, Minnie. Not for long, at least. "

"She hasn't talked to me, and we've started sleeping apart as I had to share a room with Thyra and she gets her own." You wonder inquisitively, tilting your head.

"Alix is to marry in less than a month, my pearl. This is the busiest time she will ever have in her life and no event will come that close to what she is about to overcome and prepare for." Christian explains sympathetically at his doe eyed daughter, understanding her innocuous reasoning that was still untainted by age and experience.

You stride around a rounded corner, feeling a brush of dried leaves falling from their branches.

"Well, have you taken the time to talk to her alone?"

"No?" Dagmar asks hesitantly, conflicted on whether she should have consulted her father on the matter at all.

"Then there lies the problem, my dear. It is life changing for a young woman to prepare to be legally wedded in matrimony. For any lady. What yet for our family? We had never been accustomed to such formalities, having been satisfied with next to nothing, but she is to give up her country and language for the man she loves, for her people, and for the great of all." He pinches her cheek adoringly, as she places her own soft hands against his bony, slender own against her cheeks.

Alexandra has always had so many words to say, even when it was best to say nothing, only when it came to you. She was ridiculously shy and nearly isolationist against others who were not in her intimate circle, yet if she had shut the gates to you- what else was there to do?

…

Under the ground floor staircase, a dark, shadowy room with bare candles that were overdue for replacement, barely cleaned by the meager maids you would have come in the palace, still covered in dust and cobwebs, yet this was the only time you could find time with her without any interruption.

As both of you snuck downstairs to retrieve some intricately hidden heirloom laces and few penchant jewelry to sneak in for Alexandra's regimented 'English' only wedding. Both with candlesticks in hand as you scourged through the bottom celar.

A glimpse of a smile appears on her graceful features when she recognizes a familiar portrait hidden underneath a scarlet velvet cloth.

“Minnie, do you remember the day we posed for this portrait? We barely knew how to pose for such things due to how costly they were to the household, but Papa managed to save half his yearly salary for this.” She longingly admires the portrait in front of her, lauding the coarse brushes of the oil painting, the lush colours in shades of pastels and creams.

Standing beside her apprehensively, you shift the weight between your feet restlessly, yet manage a bona fide chuckle at the joys and memories of your simple childhood, hours spent running in the grass, riding horses, picking flowers and playing with the worn out dolls you had shared in your attic in the Yellow Palace.

“Will we ever be like this again, Alix? This happy?” Dagmar asks hopefully, longing with a distant expression before looking down and releasing a long held sigh.

Alix reaches forward, holding your hands close to her chest as she envelopes your fingers in her bony palms. With a hushed urgency as her eyes bled into yours passionately, directly with such intensity you could not look away.

“I already know by the look in your eyes that you may assume that I have ignored you on purpose, that you have vexed me, upset me but it is nearly the opposite. I am fearful of the roads I am to approach alone, sister. Roads even you cannot follow and I am afraid you will no longer be by my side, because this is our fate.” In muted yet agonized whispers, her tears hit your hands under the shadows, as you nod along and sooth her before you reach forward with a tight embrace.

“Alix, you will always have my trust, my confidence. No matter how far apart we may be, you will always be my sister. You must promise to write to me as often as you can. You must swear on your life that no empires, no dynastic ambitions, no grand war plans will tear us apart.” Closing your eyes shut before you pull away from her arms, nodding along as you slightly tremble and catch a knot in your throat. Grasping at her fingers desperately like she’d fade away from you any second, you beg almost fearfully for her to silence your pleas, your worries, your fears.

“I promise.”

…

You enter the dressing room hand in hand, giggling and smiling coyly yet also sheepishly as if you were as high in the clouds in the sky. Hand in hand with your fiance, your future husband, the love of your life. Timothee. You can’t stop saying his name like a prayer, a furtive whisper, and the grin that blossoms on his handsome face is as beautiful as ever.

His mother the Tsarina awaits you both with a scarce yet open smile, her pearly white teeth on display as her prayers have been answered, seeing the woman she had wanted for her son happily betrothed to him.

“I cannot congratulate you both more than I already have. This is everything I have wanted and more. To see my son happily engaged to the woman he has loved for so long. I could die happy right now. “

“Mother, please stop saying that. You have so much longer to live, even with your illness.” He corrects his mother insistently, refusing outright at the thought of his dear mother passing anytime soon, or god forbid before he makes his way to the altar or even become Tsar of Imperial Russia.

Maria Alexandrovna approaches her dresser, covered in velvet and protected by a cloth she unravels, revealing a drawer full of diamonds, pearls, finest silks and furs, hitting the light of the late afternoon sun. You cannot help but gasp with a gawking, open mouth in shock in the splendour and elegance in front of you.

“As per tradition, a future Romanov bride is presented with gifts only deserving of a future Empress, a future Tsarina upon her betrothal.”

Timothee carefully picks up a set of diamonds on the upper corner of the oak table, carrying them in his hands cautiously as he looks up in excitement to see your reaction.

“A Romanov groom grants his future bride these diamonds, as we have for the past two hundred years. Yet as Tsesarevich, I give you these heirlooms that have been set aside for this occasion long before my birth. These diamonds come from the parure set of Empress Catherine the Great, deep in her jewelry vault and from the Ural Mountains.” He presents them to you proudly underneath lush velvet to protect the fine jewels in front of you, that you inquisitively touch with your hands to feel them against your warm skin, cold to the touch.

“These are too much. You cannot expect me to accept such gifts.” You shake your head but both mother and son insist.

“You must take them, my dear. This is only a glimpse of what you deserve, of what you are entering. The world you will become part of. This is only the beginning.”

What your eyes are glued to are, however, a string of the finest sea pearls presented in a blue velvet necklace box, that both Timothee and his mother move towards.

“If the diamonds are from your future husband, I, as your future mother-in-law, as Tsarina to her successor, every Romanov bride is presented with this pearl necklace. That you are to give to your future son’s future wife and furthermore.” Your cheeks warm up at the mention of any future children, or your hypothetical children marrying, but you know it is an eventual event you are expecting sooner than later.

You feel Timothee’s warmth behind you, his arms on either side of you as he places the pearl necklace in front of your neck, brushing his coarse fingers against your nape as he scrupulously clasps it shut.

In your low, trimmed off the shoulder dress, the cold of the pearl hit against your warm skin, and his velvety touch gave you goosebumps along your arms. As he looks into the mirror on how it shines against your skin, you feel the warmth of his breath against your clavicle, and nearly feel the ghost of his lips so close yet so far to your neck. You nearly feel himself gasp in admiration as his eyes darken, pupils dilated in your image yet he restrains himself, especially as his mother was in the audience.

Seeing yourself stand so naturally with those pearls like they were created and stringed with you in mind, you take a deep breath as you take upon the future life you are meant to live. You are no longer approaching it step by step, but at full speed ahead.

An unfamiliar longing washes over you, uncontrollable and a primal urge you are a stranger too but you want to dive deep into this warmth, this longing, this lust you have for your future husband.

“One more thing.” You drag him along with you as he willingly trails behind you with a confused, yet amused expression, his chuckles filling the halls.

Standing in front of the glass window, gilded with gold around, its immaculate, cold touch to the feeling is engraved with scribbles and signatures of past lovers in the Danish royal family before they were to wed.

Taking the diamond he gave you from your pocket, you etch the sharp bottom of the triangular shaped stone against the window, scarifying your name among the many others as it stands out as the fresh incision.

“W-What are you doing, Minnie?”

“Here we will immaculate our love, our union so that it may stand the test of time. The Danish tradition here in the palace is that spouses to be, lovers, are to engrave their name on this window, so that future generations may remember that we were once here, fully in love.”

You smile at him with hearts in your eyes, taking his larger, coarse hands in yours, pressing his fingertips gently before you place the diamond he has given you back to him.

Chuckling lightheartedly, Timothee engraved his name beside yours, immortalizing your love and future union forever.

…

“Do you have to leave so soon?” Minnie aimlessly watches Timothee gather the last of his belongings, accompanied by his chief of staff and a swad of butlers and maids at his beck and call. Holding the indigo hued fine scarf close to her chest, she feels the chills of the upcoming autumn approaching, especially by the coastal city of Copenhagen.

Everyone is frantic and unnerved, yet even among the sea of worry and scrambling, he is an oasis of calm and ease as he makes his way to the carriage, warmly dressed in his fine velvet cot, a dark scarlet bow his newly minted fiance had chosen and put on for him.

As he comforts your worries with his warm hands in your cold, gloved own, he looks into your eyes with a loving softness he only reserves for you.

“Minnie, as much as this pains me- I have to complete my duties and complete another tour before I return to Saint Petersburg. "

You are a stranger to the odd feeling you never got used to. This anxiety, this yearning for him that never went away, that if you spent any moment away from him would make you spiral into insanity. In the days leading up to his departure, you spent restless nights tossing and turning in your mattress, sweaty sheets sticking to your skin as you feared the inevitable.

Despite how he could be his most scornful critic, Timothee always knew his duty. No matter how much he would hesitate and think he would never do enough, he would give more than enough, giving himself entirely for his nation, his country.

"Yes, yes, but can you not delay it until the beginning of autumn-"

He cuts you off with a gentle palm cupping your cheeks, wiping the tears beginning to fall from your eyes.

"I have delayed this long enough, my dove. My brothers and my mother have been long gone while I have still lingered here, spending every waking second with you, but I must leave now. If only you knew how much it pains me that we shall be apart, but the sooner I leave, the sooner we will meet in Saint Petersburg at last."

Timothee leans forward for a passionate yet still proper kiss, his warm lips sucking in your upper lip, tongue slightly exploring into your cavern, before he pulls away with pained longing.

"Promise you will write to me daily, Tim?"

As he boards his carriage and its hinged door is shut by his servants, he pulls down its window.

"Every day, I will not miss a single one, my love. Every day."

You tearily watch his carriage and his surrounding escorts depart from the cobblestone area, iron gates swung open as the fine stallions depart for a long, landlocked voyage across the peninsula.

What he has awoken you is a complete stranger to what you have experienced in your short life, yet it excites you and you only long to become acquainted with this sensation.

…

#timothee chalamet imagines#timothee chalamet x reader#timothee chalamet scenarios#timothee chalamet

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

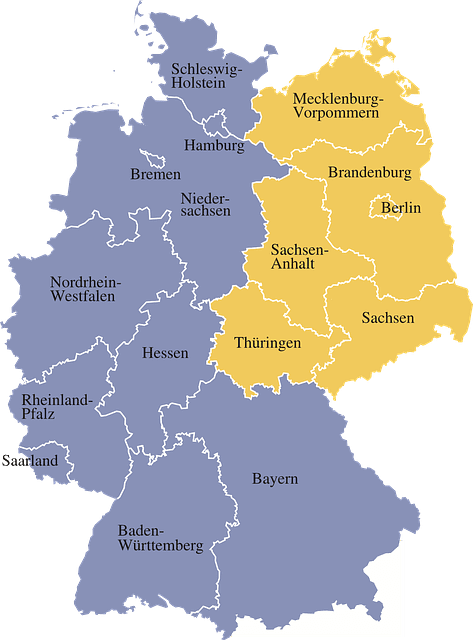

The 16 States of Germany: Exploring the Diversity and Unity

Germany, renowned for its rich history, cultural heritage, and economic prowess, is a country that consists of 16 distinct states, each with its own unique character and charm. From the bustling metropolitan areas to the serene countryside landscapes, Germany showcases a harmonious blend of modernity and tradition. Let's embark on a journey to discover the 16 states that contribute to the vibrant tapestry of this remarkable nation.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Schleswig-Holstein: Where Land Meets Sea

- Bavaria: A Tale of Traditions

- Berlin: The Heart of Modernity

- Baden-Württemberg: Innovation and Greenery

- Saxony: Where History and Culture Converge

- Hamburg: Gateway to the World

- North Rhine-Westphalia: Industrious and Dynamic

- Lower Saxony: Nature's Abode

- Hesse: Where Urbanity Meets Heritage

- Rhineland-Palatinate: Vineyards and Beyond

- Brandenburg: Castles and Lakes

- Thuringia: Enchanting Landscapes

- Mecklenburg-Vorpommern: Coastal Beauty

- Saxony-Anhalt: Of Art and Architecture

- Saarland: Small yet Significant

- Bremen: A Tale of Two Cities

- Conclusion

- FAQs

- What is the significance of Germany's division into states?

- Which state is known for its Oktoberfest celebrations?

- What makes Berlin a unique capital city?

- Which state is famous for its automotive industry?

- Are the states of Germany culturally diverse?

Introduction

Germany's federal structure comprises 16 states, often referred to as Bundesländer. This decentralized system empowers each state to have its own constitution, government, and educational policies while collaborating on national matters.

Schleswig-Holstein: Where Land Meets Sea

Nestled between the North Sea and the Baltic Sea, Schleswig-Holstein is renowned for its stunning coastline, charming villages, and maritime heritage. Visitors are drawn to its pristine beaches, and the iconic port city of Kiel hosts the renowned Kiel Week sailing event.

Bavaria: A Tale of Traditions

Bavaria, famous worldwide for its traditional culture, picturesque landscapes, and iconic Oktoberfest, embraces both its history and innovation. The state boasts fairytale castles like Neuschwanstein and a thriving technology sector.

Berlin: The Heart of Modernity

The capital city, Berlin, stands as a symbol of unity and progress. Rich in history, it houses iconic landmarks like the Brandenburg Gate, while also being a haven for artists, entrepreneurs, and diverse cultures.

Baden-Württemberg: Innovation and Greenery

Known for its high standard of living, Baden-Württemberg combines technological innovation with natural beauty. It's home to global automobile companies and the enchanting Black Forest region.

Saxony: Where History and Culture Converge

Saxony's historic cities like Dresden and Leipzig are cultural treasures. With a legacy of classical music, ornate architecture, and cutting-edge research, Saxony is a dynamic hub of art and innovation.

Hamburg: Gateway to the World

Hamburg, a bustling port city, has a maritime legacy that extends to its modernity. Its famous harbor, impressive architecture, and vibrant nightlife make it a global hub of trade and culture.

North Rhine-Westphalia: Industrious and Dynamic

This economic powerhouse, known as NRW, encompasses major cities like Cologne and Düsseldorf. With a rich industrial history, it's a melting pot of creativity, business, and diverse communities.

Lower Saxony: Nature's Abode

Lower Saxony is blessed with natural beauty, boasting the Wadden Sea National Park and serene landscapes. Hannover, its capital, seamlessly blends urban amenities with a tranquil environment.

Hesse: Where Urbanity Meets Heritage

In Hesse, the metropolis of Frankfurt contrasts with charming historic towns like Heidelberg. It's a financial center with a touch of tradition, offering a balanced urban and rural experience.

Rhineland-Palatinate: Vineyards and Beyond

This wine-producing region showcases medieval architecture, particularly in its capital, Mainz. Rhineland-Palatinate's rolling vineyards, combined with cultural heritage, make it a visual and culinary delight.

Brandenburg: Castles and Lakes

Surrounding Berlin, Brandenburg is a nature lover's paradise. Its serene lakes, picturesque countryside, and a plethora of castles create an idyllic escape from the urban bustle.

Thuringia: Enchanting Landscapes

Thuringia's dense forests and charming towns inspired poets like Goethe and Schiller. Erfurt and Weimar are cultural hotspots, offering insights into Germany's intellectual history.

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern: Coastal Beauty

The Baltic Sea coastline defines this state, where seaside resorts and historic towns abound. Mecklenburg-Vorpommern is a haven for water sports enthusiasts and those seeking tranquility.

Saxony-Anhalt: Of Art and Architecture

Home to the Bauhaus movement, this state celebrates modern art and design. Saxony-Anhalt's cultural offerings extend to historic Magdeburg and the scenic Harz mountains.

Saarland: Small yet Significant

Saarland's picturesque landscapes and unique blend of French and German influences make it an intriguing destination. Its industrial heritage and natural beauty create a distinctive identity.

Bremen: A Tale of Two Cities

Bremen and Bremerhaven, two cities within this smallest state, offer maritime history and modern innovation. Bremen's UNESCO-listed market square and the German Emigration Center in Bremerhaven provide diverse experiences.

Conclusion

Germany's 16 states showcase a harmonious blend of traditions, innovation, nature, and culture. Each state contributes to the nation's identity, reminding us of the diversity that unites this remarkable country.

FAQs

- What is the significance of Germany's division into states? Germany's federal structure empowers states with autonomy while fostering unity on a national level.

- Which state is known for its Oktoberfest celebrations? Bavaria is renowned for hosting the world-famous Oktoberfest, a celebration of Bavarian culture.

- What makes Berlin a unique capital city? Berlin is a melting pot of art, history, and modernity, reflecting Germany's complex history and contemporary vitality.

- Which state is famous for its automotive industry? Baden-Württemberg, with cities like Stuttgart, is a hub of automobile manufacturing and technological innovation.

- Are the states of Germany culturally diverse? Yes, each state has its own distinct culture, traditions, and characteristics, contributing to Germany's rich diversity.

Read the full article

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some impressions of Lübeck

I visited Lübeck for 2 days.

Lübeck itself is a very pretty city, also it has huge historical value. I will try to show and explain some of the stuff I have seen in this little post :D

First of all, Lübeck was part of the Hanseatic League. It existed even prior to Hamburg and was one of the first cities that traded by ship with faraway places such as Russia and Kiew. Because of its huge influence it was also called “Queen of the Hanse”. Due to the extreme riches the merchants were able to make of the trade the houses were soon made of red bricks, which were very expensive at the time. Also Cathedral and churches were built.

But when you enter the city the first thing you will see is the famous Holsten Gate.

The Holsten Gate was part of the huge citywall, which doesnt exist anymore today but protected the city towards Holstein. The walls were 3 meters strong on this side, this insides are very spacious and housed several guards and weapons. You can see on the picture that the towers are slightly lopsided. This is because the ground sank down in the 13th century already. Still, the protection was so good that Lübeck was never attacked in the middleages.

Here you can see Lübeck in miniature with all the citywalls. The Holsten Gate is the smaller pointy building left in front of the Trave (the river). At the Holsten Gate taxes were collected for entering the city. 5 Pennies if your were barefoot, 20 pennies if you had shoes! XD

The next thing you’ll see as you go on are houses. But not any houses! These were the salt storehouses. Salt was brought in by ship and directly transported into these houses. It was then used to salt Herrings. One of the most important trading goods since Christians weren’t allowed to eat meat during lent, therefore fish was the next best thing.

The houses right at the Trave were mostly owned by the merchants. Merchants owned the ships and dealt with the trade, however as history went on they didnt need to go to places themselves anymore but sent their men and did their own business at home. In safety.

Also the people of Lübeck LOVE roses. There are roses everywhere. There even is a whole street called “Rosestreet”. And if you look closely at the miniature again you will see that the houses are build in a certain way. They all have little gardens tucked away behind them! You can reach those when you go through small corridors. Some are so small you have to bend over or else you cannot fit through.

When you have managed to squeeze through you’ll reach little paradise! Like this:

And this is Rosestreet :D

Also interesting are the many churches and the Cathedral. They are all not as golden as the ones in Erfurt, but you can see a lot of the original colors and drawings. Many mechants were buried here, as well as important rulers. I won’t show that many pictures here, just the ones I thought most impressive.

Now what’s the deal with the broken bells?

Easy. In WW2 Lübeck was bombed after Germany bombed Britain. It was a revenge act and most of St. Mary Magdalene church was destroyed. These bells fell down and they still lie there today. In the Hanseatic Museum you can also see the only remaining intact parts of a colored window from this church.

Since we are already speaking about windows. The most impressive, most beautiful thing I have seen in all of Lübeck was also a window. This one!

It is located in the very first hospital Lübeck built in 1268, the “hospital of the holy ghost”. It was hospital and nursing home for the poor and old. It had its own chapel too.

That’s it from the outside. It’s a huge complex of buildings, right next to the Jacobichurch. A lot of the walldecoration is still visible inside.

Another important place is the townhall with the market behind. All the very important merchants in the Hanseatic League came from all over to have so called “Hansetage” which could last up to a month, where all important things were discussed and later published to the common people on the market. As you can see the townhall itself is HUGE.

that’s the front.

And that’s part (!) of the back. In total this building is at least as big as one of the churches. If not bigger. Also the scribes had their own building right next to the townhall on top so they did not waste space inside the townhall. I’ve never seen this before.

The last thing I will show you is a monastery. Today it is part of the Hanseatic Museum. When they built the museum they found remaining wallparts from medieval times which are now included in the museum. The museum itself is very awesome and informative and if you ever visit Lübeck- please go visit there :D

However, even more interesting for me was the monastery itself. It was once used by Dominican monks, and was later used as a prison and a court building. You can go trough the chapter house and the winterrefectorium. The ladder is especially interesting because parts of the heating system were found beneath the ground!

All in all, Lübeck was lovely. I’d recommend at least 2 to 3 days or else you will miss a lot. If you are tired after all that walking you can chill at the Trave in many many places like here at the historical part of the harbour.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Schleswig-Holstein gegen Microsoft

"Nutzung von Microsoft Office 365 rechtswidrig"

Zumindest sei die Nutzung von Microsoft Office 365 durch die EU-Kommission rechtswidrig, das hatte der EU-Datenschutzbeauftragte im März entschieden. Als Grund für seine Feststellung hatte er angegeben, dass das CLOUD-Gesetz der USA US-Konzerne verpflichtet, den Geheimdiensten auf Verlangen alle Daten auf ihren Servern zugänglich zu machen, auch wenn diese auf Servern in Europa sind.

Der hessische Datenschutzbeauftragte hatte aus diesem Grund auch das Microsoft Office 365 Paket für die Schulen in seinem Bundesland verboten. Auch Schleswig-Holstein zieht nun endlich Konsequenzen. Das dortige schwarz-grüne Kabinett hat laut Kieler Nachrichten beschlossen, die Lizenzen für Microsoft-Standardanwendungen wie Word im Herbst 2025 auslaufen zu lassen und alle Bediensteten zur Nutzung freier Linux-Alternativen wie Libre Office zu verpflichten.

Leider ist der Herbst 2025 noch weit entfernt und aus München kennen wir das Hin und Her zwischen Microsoft Windows und Linux zum Schaden der Nutzer aus mehreren Akten (Balmer und Gates in München , Schwarz-Rot in München will zurück zu Windows , Rot-Grün für Offene Software in München ).

Warum kann die EU, die schon vor Jahren festgelegt hat, dass das Open Document Format (ODF) das einheitliche Austauschformat in Europa ist, nicht endlich gegen Software-Konzerne vorgehen, die dieses Format aus unternehmerischen Gründen nicht unterstützen wollen? Uns ist natürlich klar, dass selbst ein Umschwenken in der Frage der Datenformate den "Datenabfluss in Drittländer", wie zu den US Geheimdiensten nicht verhindern würde ...

Mehr dazu bei https://norberthaering.de/new/schleswig-holstein-microsoft/

Kategorie[21]: Unsere Themen in der Presse Short-Link dieser Seite: a-fsa.de/d/3A9

Link zu dieser Seite: https://www.aktion-freiheitstattangst.org/de/articles/8750-20240419-schleswig-holstein-gegen-microsoft.html

#Linux#CDU#Grüne#Schleswig-Holstein#Hessen#Transparenz#Informationsfreiheit#Anonymisierung#Netzneutralität#OpenSource#Verbraucherdatenschutz#Datenschutz#Datensicherheit#Microsoft#Windows#ODF#EU#DSB

1 note

·

View note

Text

By Sam Knight

On a hot, pollen-dazed morning this summer, I stopped by the house of Gareth John, a retired agricultural ecologist, who lives on a quiet lane above a river in Oxfordshire, to take a look at his bees. In British beekeeping circles, John, who has a white beard and a sprightly, didactic manner, is well known as a “natural beekeeper,” although he acknowledged right off the bat that this was a problematic term. “It’s an oxymoron, right?” he said. John cares for perhaps half a million bees, but he does not think of himself as keeping anything. “I wouldn’t call myself a dog-keeper,” he said. “But I have a dog.” Natural beekeepers are the radical dissenters of apiculture. They believe that mainstream beekeeping—like most human-centered interactions with the natural world—has lost its way. There is another path, but it requires the unlearning and dismantling of almost two centuries of bee husbandry and its related institutions. During my visit, John asked me not to disclose his exact location, because his hives fell off the radar of the National Bee Unit, a government agency that monitors honeybee health, about a decade ago, and he prefers it that way.

John grew up in the English countryside in the sixties and seventies, when beekeeping was—as he remembers it—a gentle, live-and-let-live pastime: men in veils pottering around a few hives under the apple trees, jars of honey for sale at the garden gate. “It was very, very leave-alone,” he said. “Natural.” When John returned to the craft, in the early two-thousands, he was shocked by what it had become. In 1992, an ectoparasitic mite called Varroa destructor, which had jumped from an Asian honeybee to the Western one sometime in the fifties, emerged in Britain and killed untold millions of bees. Thousands of hobbyist beekeepers gave up. (Varroa reached the U.S. in 1987, and wrought similar devastation.) There was an atmosphere of vigilance and doom. Bee researchers talked about the “Four P’s”—parasites, pathogens, poor nutrition, and pesticides—as if they were the horsemen of the Apocalypse. The British Beekeeping Association, which has served as the custodian of the craft since the late nineteenth century, ran courses on pest control. “Fear,” John said. “Disease. Disease. Disease.” He watched fellow-beekeepers treat their bees with miticides, to control varroa; import more prolific queens, and other non-native bees from southern Europe, to boost honey production; and feed their hives syrup to get them through the winter. “It had become this agro-industrial monster, where you were supposed to behave as if you had a high-yielding Holstein dairy cow,” he recalled.

It didn’t feel right. As a species, the Western honeybee (Apis mellifera) is millions of years old. (It was introduced to North America by European settlers in the sixteen-twenties.) Although people have harvested its honey and wax—sweetness and light—for thousands of years, the honeybee has not been tamed. “Wheat is domesticated. Cows are domesticated. Dogs are domesticated,” John said. “Domestication is a mutual process. You could never domesticate a robin. Bees are the same as robins. They will quite happily live in a nest box that you give them. But they’re not dependent on you. They don’t need you.”

John did not believe that beekeeping’s intensive turn was helping the bees. He looked around for other skeptics and came across “The Principles of Beekeeping Backwards,” a quasi-mystical tract published in Bee Culture, in the summer of 2001. The text was by Charles Martin Simon, a.k.a. Charlie Nothing, an artist and an experimental-rock musician who invented the dingulator, a guitar-like instrument made from car parts.

Simon, who was based outside Santa Cruz, California, was also an organic farmer and a beekeeper. He had developed his own kind of bee frame. (In the fall of 1851, the Reverend Lorenzo L. Langstroth, a Congregationalist pastor from Philadelphia, created the world’s first commercially viable beehive with removable frames and, thus, modern beekeeping.) “Beekeeping Backwards” was Simon’s disavowal of the craft that he’d practiced for forty years. He rejected chemicals for treating varroa; synthetic foundation frames, to make bees construct neat honeycombs; and the removal of male drones, which don’t contribute to honey-making. “Our industry is directed by madmen,” Simon wrote. “They have been driven mad by the fear of death and simultaneously compelled irresistibly toward it. Death of our beloved bees. Death of our beloved industry. Death of ourselves.”

The better part of two centuries after Langstroth’s hive went on sale, natural beekeepers liken much conventional beekeeping to industrial agriculture—permeated by chemicals and the delusion of human control. They dwell on the differences between the lives of wild, or free-living, bees and those which are kept in apiaries. Managed bees are typically kept in a drafty box low to the ground, as opposed to a snug nest high in a hollow tree. Most beekeepers’ colonies are much larger than those which occur in the wild, and rival colonies might be separated by only a few yards, rather than by half a mile. Much of the bees’ honey, which is supposed to get them through the winter, is taken before they have a chance to eat it. A queen bee goes on a spree of mating flights early in her life, and then lays the fertilized eggs until her death. In apiaries, queens often have their wings clipped, to interrupt swarming (a colony’s natural form of reproduction), and are routinely inspected, and replaced by newcomers, sometimes imported from the other side of the world. Propolis—a wonderful, sticky substance that bees make from tree resin and that has antibacterial qualities—is typically scraped out of hives by beekeepers because it is annoying and hard to get off their hands.

These are all dire interventions in the fabric of the colony. No wonder the bees keep dying. In a normal year, perhaps ten or fifteen per cent of bee colonies die in the winter. Last winter, America’s bees suffered colony losses of close to forty per cent, with varroa, “queen issues,” and starvation among the leading causes. High death rates tend to lead to more bee imports, more bee medication, more bee supplements, more bee-breeding programs, and the whole unwieldy cycle continues.

Natural beekeepers leave their bees alone. They seldom treat for disease—allowing the weaker colonies to fail—and they raise the survivors in conditions that are as close as possible to tree cavities. They fill their hives with swarms that come in on the wing, rather than those which come from dealers who trade on the Internet. They treasure the bees for their own sake—like a goldfinch that nests in the yard—and have an evangelical spirit, as if they have stumbled on a great secret. They are disdainful of conventional beekeepers. “They’ve completely lost sight of the creature,” John told me.

Honey is a touchy subject. John said that he harvests only an absolute excess—after the bees have enough for two winters and a wet summer—and even then he won’t take money for it. “It’s not my honey to sell,” he explained. Another natural beekeeper, who abstains from taking honey altogether, referenced “When Harry Met Sally” to explain his position: “There was this line, ‘Sex always gets in the way of friendship.’ I think honey always gets in the way of us appreciating bees.”

Bees were long held to be prophetic—messengers from another realm. The name of Deborah, the prophetess and judge of the Old Testament, translates as “bee.” The priestesses who tended the oracle at Delphi were known as Melissae. Melissa means “bee,” too. For a quarter century, anxiety about the fate of honeybees has been a manifestation of our unease about the state of pollinators and our biomes in general. But that doesn’t mean we have been interpreting the problems correctly, or that humans are the best placed to find solutions. Natural beekeepers think of themselves as deferring to the bees for guidance. “If I go to a hive and I put my hand on the hive . . . I can actually feel their presence, and that balance and that skill and that beauty that only nature can provide,” Jonathan Powell, of Britain’s Natural Beekeeping Trust, told me. “And yet if I think of a bee flying up to the window of my house, putting their antennae on my house, I’m frankly embarrassed by the way I live, and how clumsy and how stupid I am.”

In Oxfordshire, John led the way to his apiary, which was on a small pasture at the back of his property, bounded by high hedgerows. There was a lock on the gate and a small workshop, where he makes and maintains fifteen or so hives. A honeybee colony is a female commonwealth—a biological marvel of social decision-making by a queen and her thousands of female workers. (Beekeeping, by contrast, was for a long time a patriarchy. The monks of Mt. Athos, in Greece, were allowed to keep bees because the insects were assumed to be all male.)

“Hello, sweethearts,” John said, as he revealed the glass inspection wall of a Warré hive, first developed by a French priest in the nineteen-thirties, that he had reimagined. The rest of John’s apiary was like a real-estate showcase for honeybees. There was a log hive on stilts, and woven skeps, basketlike hives that were popular among the Vikings. Conventional beehives tend to be portable, so they can be moved around farms, and easy to access, to help beekeepers inspect and manipulate their bees. John’s hives were homes, for the bees to make their own. Approaching a skep, he opened his palms, in a submissive pose modelled on wall paintings of ancient Egyptian beekeepers, and asked me to step out of the bees’ path as they flew in and out of the entrance.

John visits his apiary most days, to watch and listen to his bees. “There is communication going on,” he said. “And it’s a two-way communication, if you allow it to be.” His modifications to the Warré hive incorporated new dimensions, inspired by the golden ratio of the Fibonacci sequence.

Inside, the colony looked like a train station at rush hour. John pointed out bees fanning their wings, to keep the temperature and carbon-dioxide levels under control, and guards stationed at the entrance, apparently checking the bright-yellow beads of pollen that arrived on their fellow-bees’ knees, like bag searchers at a museum. In the forties, a German beekeeper named Johann Thür used the term Nestduftwärmebindung—literally, nest-scent-heat-binding—to convey the heady fug of warmth, humidity, pheromones, and other mysterious signals that is essential to a healthy bees’ nest. Natural beekeepers often speak of the hive in somewhat spiritual tones, as a single, sentient organism that has evolved in parallel to mammals like us. “This creature is not like any other creature we ever interact with,” John said. I touched the glass. The hive thrummed. The smell of honey rolled across the pasture.

On the afternoon of August 20, 2002, Thomas Seeley, a biology professor at Cornell, arrived at a clearing on the edge of the Arnot Forest, in upstate New York, with a wooden bee box that held a piece of old honeycomb filled with syrup. Seeley is the world’s leading authority on the lives of wild honeybees. He had come to the same clearing twenty-four years earlier, in August, 1978, as part of a survey of the forest, during which he found nine wild colonies, living in the trees.

Seeley was curious, and somewhat fearful, about what had happened to the forest’s bees since the arrival of Varroa destructor. He had lost nine of his ten research hives to the mites. In the clearing, Seeley roamed with the bee box. For ten minutes, he wondered if all the wild bees were gone. Finally, he spotted a honeybee feeding from a goldenrod flower. After she fed from the syrup in the box, Seeley took a compass reading of her path—her beeline—as she flew back into the trees. When bees find something good to eat, they inform their fellow-foragers by means of the waggle dance—a representation of direction and distance that takes its bearing from the sun—which the other bees interpret, in the darkness of the nest, mostly by touch. More bees arrived in the clearing. By the end of the afternoon, Seeley had two solid beelines—one heading north, one heading south—indicating at least two nests in the forest.

During the next twenty-seven days, Seeley found eight bee colonies in the Arnot Forest, but in a smaller area and in less time than he had in 1978—suggesting that the wild population was just as healthy as it had been before varroa. “How can this be . . . . ?” he asked in Bee Culture, the following year. Seeley aired three possibilities: the bees in the forest had been sufficiently isolated to escape infection; they had been infected, and were about to die; or—his hope—the bees had been exposed to varroa and had developed some form of resistance.

“None of us knew at the time how strong the selection would be in the wild,” Seeley told me recently. “It turned out that the bees had the variation needed to develop the traits to resist the mites.” While beekeepers were experimenting with chemical treatments and hive designs, the bees in the forest were changing genetically. Their life styles helped them, too. “Colonies living in the wild have many things going for them,” Seeley said. The bees lived in smaller groups, relatively far apart, which made it harder for varroa to spread. They swarmed every year, which broke the reproductive cycle of the mites. (If a colony swarms, the nest is left without bee larvae, which is where varroa mites take hold.) Wild nests were hygienic and coated in propolis. Their Nestduftwärmebindung was on point. Seeley shared his findings in books and papers, but they weren’t what most beekeepers wanted to hear. “My phone didn’t ring off the hook,” he said. Seeley is gentle and plainspoken, but his conclusions were totalizing. “As I see it, most of the problems of honey bee health are rooted in the standard practices of beekeeping,” he told me in an e-mail, “which are used by nearly all beekeepers.”

In March, 2017, Seeley proposed what he called Darwinian Beekeeping. “Solutions to the problems of beekeeping and bee health may come most rapidly if we are as attuned to the biologist Charles R. Darwin as we are to the Reverend Lorenzo L. Langstroth,” he wrote in the American Bee Journal. Seeley listed twenty differences between the lives of wild bees and those kept in conventional hives. He observed that the most routine beekeeping activities—taking wax, preventing swarming, even looking inside a hive—constituted profound disturbances for bees.

“I don’t think anybody contests that free-living bees have a better, easier life,” Seeley told me. “What is contested is whether that’s realistic.” Seeley acknowledged that there will always be commercial bee operations, for honey production and for crop pollination. But these constitute the minority: around ninety per cent of American beekeepers are hobbyists, with twenty-five colonies or fewer. Seeley compared intensively managed bee colonies to racehorses. “They live a short, hard life,” he said. “My whole aim has been to present that there is an alternative. In the United States, beekeepers are taught only what we might call the industrial form of beekeeping. And that’s where I would say, ‘No . . . there is a choice here between how you want to relate to an organism whose life, in a way, you have under your control.’ ”

Natural beekeeping has arisen alongside a broadening sense of bee intelligence. People have always known that the creatures are remarkable. “The discovery of a sign of true intellect outside ourselves procures us something of the emotion Robinson Crusoe felt when he saw the imprint of a human foot on the sandy beach of his island,” Maurice Maeterlinck, a Belgian playwright and bee scholar, wrote of bees in 1901. “We seem less solitary than we had believed.”

The Mayans worshipped Ah-Muzen-Cab, the god of bees and honey. In Lithuanian, a verb meaning “to die” is reserved for humans and bees. Like us, bees practice architecture and their own, presumably less debased, form of democracy. In 1927, Karl von Frisch, an Austrian zoologist, explained the waggle dance, for which he later won the Nobel Prize. “The bee’s life is like a magic well: the more you draw from it, the more it fills with water,” he wrote. And the water has only kept rising. In 2018, researchers showed that bees understood the concept of zero—an ability previously thought to be limited to parrots, dolphins, primates, and recent humans. (Fibonacci introduced zero to Western mathematics around the year 1200.) When I spoke to Seeley, he was running an experiment on the importance of bee sleep at a research station in the Adirondacks. “It’s not just an energy-saving process,” he explained. “It really improves their cognitive abilities.” A bee’s brain is the size of a sesame seed.

In the early nineties, when Lars Chittka, a German zoologist, was a graduate student in Berlin, he was not sure that bees could feel pain. In 2008, he co-authored a paper suggesting that bumblebees could suffer from anxiety. Last year, Chittka published the book “The Mind of a Bee,” which argues that the most plausible explanation for bees’ ability to perform so many different tasks, and to learn so well, is that they possess a form of general intelligence, or bee consciousness. “Bees qualify as conscious agents with no less certainty than dogs or cats,” he wrote.

Chittka based his conclusion on work in his own lab and on hundreds of years of bee study, including that of Charles Turner, a Black American scientist, who was denied a university-based research career and instead worked as a high-school teacher in St. Louis. Starting in the eighteen-nineties, Turner observed variations in problem-solving among individual spiders, “outcome awareness” in ants, and the ability, in bees, to steer by visual landmarks—“memory pictures”—rather than by instinct. Turner posited ideas of general invertebrate intelligence which were almost entirely ignored. “He was really a century ahead,” Chittka said. Last year, the U.K. passed legislation that recognized animals as sentient beings, capable of feeling pain and joy. So far, the bill dignifies vertebrates, decapod crustaceans (crabs and lobsters), and cephalopods (squids and octopuses), but not a single conscious bee.

The more we know about bees, the more complicated beekeeping becomes. When I visited Chittka’s lab, he flipped open a laptop to show me a sequence from “More Than Honey,” a Swiss documentary from 2012, which included footage from the pollination of California’s five-billion-dollar almond crop—an annual agro-industrial pilgrimage that involves an estimated seventy per cent of America’s commercial beekeepers. On the screen, a mechanical arm scraped tumbling bees and honeycomb from the edge of a plastic hive, before loading it onto a truck. “It’s disgusting,” Chittka said. “But the absurd thing is that these people then complain that their bees are dying.”

Like many entomologists, he does not see honeybee health as primarily an ecological problem. “Where they are under threat, it’s because of poor beekeeping practices,” Chittka said. In the scientific literature, the Western honeybee is sometimes referred to as a “massively introduced managed species” (MIMS), whose population is increasing on almost every continent, often to the detriment of other wild pollinators. In 2020, researchers concluded that the thirty-three hundred wild bee species of the Mediterranean basin were being “gradually replaced” by a single species of managed Apis mellifera. The same year, a report from the Royal Botanic Gardens, at Kew, warned that parts of London had too many honeybee colonies, whose foraging was displacing the city’s wild bee species. “Beekeeping to save bees could actually be having the opposite effect,” the report found.

“I often get asked, ‘So, is this true, that all the bees are dying?’ ” Chittka said. “And any nuanced message—‘Well, it’s not the honeybees. It’s the other wild bees’—is often misinterpreted. ‘You’re saying there’s not a problem?’ And, actually, there is a problem. It’s just a slightly different one.” For a long time, the honeybee was characterized as a canary in the coal mine, an omen of catastrophe for the rest of the world’s pollinators. In recent years, some scientists have begun to question this analogy and to challenge the conditions of industrial agriculture and conventional beekeeping instead. “We see the canary, we know it is unwell,” Maggie Shanahan, a bee researcher who recently completed a Ph.D. at the University of Minnesota, wrote, last year, in the Journal of Insect Science. “But focusing solely on individual aspects of canary health actually keeps us from asking more fundamental questions: Why are we keeping canaries in coal mines in the first place? Why are we still building coal mines at all?”

The first meeting of the British Beekeepers Association took place on May 16, 1874, at a town house on Camden Street, in North London. It was a self-consciously modern project, which aimed to replace the homemade skeps and uncontrolled swarms of the rural working classes with honesty, sobriety, and the latest beekeeping technology. Beekeeping exams began in 1882. Members took part in “bee-driving” competitions inside a large mesh tent, in which they raced to find a colony’s queen. (The first winner was C. N. Abbott, the founder of the British Bee Journal, with fourteen minutes and thirty-five seconds.)

There have been times, during its century and a half of existence, that the B.B.K.A. has more or less merged with the British state, in the causes of pollination and honey production. In 1898, the Postmaster General allowed live bees to be sent in the mail. The National hive, Britain’s version of the Langstroth, was introduced in the twenties. During the Second World War, beekeepers were allowed extra sugar rations. The B.B.K.A. now has around twenty-seven thousand members. You can become a Master Beekeeper if you pass ten of the association’s exams, in such fields as biology, honeybee management, and queen rearing. B.B.K.A. members are encouraged to use their harvests to bake Majestic & Moist Honey Cake.

When I read about the B.B.K.A., the first thing it reminded me of was a bee colony. Powell, of the Natural Beekeeping Trust, compared it to a church of conventional beekeeping, complete with its own liturgy and rituals, such as the National Honey Show. “Every year, that syllabus is pounded into them,” Powell said. “We have hymns and chanting in religion because the message is always the same.”

The president of the B.B.K.A., Anne Rowberry, was hard to reach. (Last October, she travelled to London to give the King a jar of honey.) But I met Margaret Murdin, a former chair and president of the B.B.K.A., for a coffee in Chipping Norton, a market town in the Cotswolds. Murdin is one of around ninety holders of the National Diploma in Beekeeping, the U.K.’s highest qualification. Her day job, before she retired, was advising the government on special-needs education. “I should have been an entomologist,” she said. Murdin said that neither she nor the B.B.K.A. had any quarrel with natural beekeepers. (The association discourages the importing of queens and supports local bee breeding.) From Murdin’s point of view, any animosity came from the other side. “How you keep your bees is entirely up to you,” she said. “If they don’t like it, they will leave.”

Murdin admired Seeley’s bee research and agreed with almost all of it. “They certainly prefer not to be interfered with,” she said. “That goes without saying. So do I.” But she drew the line at two of the basic tenets of natural beekeeping: allowing bees to swarm and not treating them for disease. Swarms, she said, bother the public. (They also usually mean a significant hit to the honey harvest that year.) “If I had cows, I wouldn’t want them jumping out of their field and annoying my neighbors,” Murdin said. “I don’t want my bees doing it, either.” At heart, Darwinian beekeeping offended her sense of responsibility as a beekeeper. “You can let the bees get on with it, if you hadn’t interfered so much in the first place,” she said. It was humans who brought in varroa and pesticides and agricultural monocultures. “You can’t say, ‘We’ve got a pandemic and we’re not going to intervene. We’re going to let everybody die of Covid,’ ” she added. If we have broken the bees, then it is our job to fix them.

Beekeepers often joke about how much they disagree with one another: “If you ask four beekeepers, you will get five opinions.” Their collective noun, they say, should be an argument of beekeepers. I wonder if this has to do with each being the sole authority in his apiary, of being a “strange god,” in Maeterlinck’s phrase, to the bees. When natural and conventional beekeepers do clash, it is normally online. (On beekeeping forums, natural beekeepers sometimes signify themselves as “TF,” or treatment-free.) When I visited Gareth John’s garden, Paul Honigmann, from the Oxford Natural Beekeeping Group, joined us. There were a hundred and nineteen beekeepers on his e-mail list, compared with three hundred and fifty-four members of the Oxford branch of the B.B.K.A., and many belonged to both. According to the B.B.K.A., about a third of British beekeepers did not treat their bees for varroa last year. “There’s a phenomenon in sociology where, when you’ve got a very small out-group, nobody cares,” Honigmann said. “When that immigrant population or whatever hits a certain threshold, they are perceived as a threat.”

There is rarely an occasion for beekeepers to fight in the open. (One bee conservationist told me that he left the B.B.K.A. after a physical confrontation at a meeting.) But Andrew Brough, a conventional beekeeper from Oxford, says that, in the fall of 2020, he was asked to move a dozen hives into the orchards of Waterperry Gardens, a set of ornamental gardens to the east of the city, to help with the pollination season the following spring. Unbeknownst to him, Gareth John had also been looking after bees on the property, with another natural beekeeper, for several years. Brough secures his hives with pallet strapping and metal fasteners. As the weeks went by, he began to suspect that someone was tampering with the hives. “They were progressively being opened up on a Friday,” he said.

Brough imports queens from Denmark. When he introduced a new queen to one of his hives, it disappeared. One day, Brough found John and two other natural beekeepers standing outside his hives. “They were trying to kill my queens,” he said. (John described Brough’s account as “slander” and said that he had stumbled across Brough’s hives, unaware of his presence in the orchard.) Brough says that he offered the natural beekeepers a jar of honey, to show that there were no hard feelings, but they declined. (Eventually, both Brough and John stopped working at the gardens.) Brough dismissed natural beekeeping as an image thing. “It’s new, green, rock and roll,” he said. “Beards and sandals.” He thought for a moment. “Quite a lot of ordinary beekeepers also have beards and sandals,” he conceded. Brough told me that he makes a subsistence living from selling queens and the honey that he harvests each year. “Why they want to keep honeybees, I do not know,” he said.

I wanted to find a beekeeper who was respected on all sides. Eventually, I heard about Roger Patterson, who maintains dave-cushman.net—a Web site built by a fellow-beekeeper who died in 2011—which is regarded as one of the world’s best sources of apiculture information. Patterson started keeping bees sixty summers ago. He served for eight years as a trustee of the B.B.K.A., but he is better known as the president of the Bee Improvement and Bee Breeders Association, a more radical outfit that has long opposed the importing of foreign bees. Patterson has a reputation of being somewhat ornery. He is critical of exams and isn’t scientifically trained. But his views command attention. “I would very much believe what he’s telling you,” Seeley said. “He’s a straight shooter.”

Patterson runs a teaching apiary for his local beekeeping association in a small wood in West Sussex. When I arrived, he was in a clearing, clipping queens. I waited on the path with his dogs. Patterson wore jeans that were held up with green suspenders. He pulled a pair of plastic chairs out of a shipping container and we sat down to talk by his car. He was despondent about the state of beekeeping generally, whether natural, conventional, or on commercial bee farms. “When I first started keeping bees, at least fifty per cent of our members worked on the land in some way. They were practical people. They were cowmen, or foresters or gardeners,” Patterson said. “If they had a problem, they knew enough that they could get out of it for having a bit of gumption.” Modern beekeepers preferred simple answers. “There’s a lot of narrow thinking going on,” he said.

Patterson was sympathetic to the ideas of natural beekeepers, although he suspected that many of them were misguided novices. “ ‘Oh, wouldn’t it be lovely?’ You know,” he said. During the pandemic, Patterson experimented with not treating his bees for varroa and lost sixteen out of nineteen hives. He was fine with that. But he needed to have bees to teach with, so he had to start treating again.

What really worried him were the bees. Something was up. “Very up,” Patterson said. Since the early nineties, he had noticed that his queens could not lead their colonies for as long as they used to. In the past, Patterson’s queens had lived for five or six years. Now they were being superseded—deposed by the colony—within a year or two. Patterson hadn’t changed his beekeeping techniques much since 1963. “It is a massive problem,” he said. Some of the queens seemed fine. Others had misshapen wings. Patterson’s theory was that something was interfering with the bees’ pheromones in the hive, their Nestduftwärmebindung. But he didn’t know what.

“Lots of things are changing,” he said. “People are changing. The bees are changing. The environment’s changing.” Patterson wondered whether natural beekeeping was just another human vanity that was being foisted on the bees. At the same time, he had come to doubt the health of the creatures whose lives he was managing from season to season. “I reckon that the bees in trees are healthier than bees raised in hives,” he told me. But Patterson was a beekeeper. “Throughout my beekeeping life, I have always tried to improve the bees,” he said. Patterson explained that when he said this most people thought he meant improving the bees to make more honey. “I think you can improve bees from the point of view of bees as well,” he said. Patterson was not ready to admit that this task might be beyond him, or any beekeeper. He had inspected nine colonies that morning. After I left, he was going to place new queens into the hives that he feared would not last the winter.

1 note

·

View note

Text

By Sam Knight

On a hot, pollen-dazed morning this summer, I stopped by the house of Gareth John, a retired agricultural ecologist, who lives on a quiet lane above a river in Oxfordshire, to take a look at his bees. In British beekeeping circles, John, who has a white beard and a sprightly, didactic manner, is well known as a “natural beekeeper,” although he acknowledged right off the bat that this was a problematic term. “It’s an oxymoron, right?” he said. John cares for perhaps half a million bees, but he does not think of himself as keeping anything. “I wouldn’t call myself a dog-keeper,” he said. “But I have a dog.” Natural beekeepers are the radical dissenters of apiculture. They believe that mainstream beekeeping—like most human-centered interactions with the natural world—has lost its way. There is another path, but it requires the unlearning and dismantling of almost two centuries of bee husbandry and its related institutions. During my visit, John asked me not to disclose his exact location, because his hives fell off the radar of the National Bee Unit, a government agency that monitors honeybee health, about a decade ago, and he prefers it that way.

John grew up in the English countryside in the sixties and seventies, when beekeeping was—as he remembers it—a gentle, live-and-let-live pastime: men in veils pottering around a few hives under the apple trees, jars of honey for sale at the garden gate. “It was very, very leave-alone,” he said. “Natural.” When John returned to the craft, in the early two-thousands, he was shocked by what it had become. In 1992, an ectoparasitic mite called Varroa destructor, which had jumped from an Asian honeybee to the Western one sometime in the fifties, emerged in Britain and killed untold millions of bees. Thousands of hobbyist beekeepers gave up. (Varroa reached the U.S. in 1987, and wrought similar devastation.) There was an atmosphere of vigilance and doom. Bee researchers talked about the “Four P’s”—parasites, pathogens, poor nutrition, and pesticides—as if they were the horsemen of the Apocalypse. The British Beekeeping Association, which has served as the custodian of the craft since the late nineteenth century, ran courses on pest control. “Fear,” John said. “Disease. Disease. Disease.” He watched fellow-beekeepers treat their bees with miticides, to control varroa; import more prolific queens, and other non-native bees from southern Europe, to boost honey production; and feed their hives syrup to get them through the winter. “It had become this agro-industrial monster, where you were supposed to behave as if you had a high-yielding Holstein dairy cow,” he recalled.

It didn’t feel right. As a species, the Western honeybee (Apis mellifera) is millions of years old. (It was introduced to North America by European settlers in the sixteen-twenties.) Although people have harvested its honey and wax—sweetness and light—for thousands of years, the honeybee has not been tamed. “Wheat is domesticated. Cows are domesticated. Dogs are domesticated,” John said. “Domestication is a mutual process. You could never domesticate a robin. Bees are the same as robins. They will quite happily live in a nest box that you give them. But they’re not dependent on you. They don’t need you.”

John did not believe that beekeeping’s intensive turn was helping the bees. He looked around for other skeptics and came across “The Principles of Beekeeping Backwards,” a quasi-mystical tract published in Bee Culture, in the summer of 2001. The text was by Charles Martin Simon, a.k.a. Charlie Nothing, an artist and an experimental-rock musician who invented the dingulator, a guitar-like instrument made from car parts.

Simon, who was based outside Santa Cruz, California, was also an organic farmer and a beekeeper. He had developed his own kind of bee frame. (In the fall of 1851, the Reverend Lorenzo L. Langstroth, a Congregationalist pastor from Philadelphia, created the world’s first commercially viable beehive with removable frames and, thus, modern beekeeping.) “Beekeeping Backwards” was Simon’s disavowal of the craft that he’d practiced for forty years. He rejected chemicals for treating varroa; synthetic foundation frames, to make bees construct neat honeycombs; and the removal of male drones, which don’t contribute to honey-making. “Our industry is directed by madmen,” Simon wrote. “They have been driven mad by the fear of death and simultaneously compelled irresistibly toward it. Death of our beloved bees. Death of our beloved industry. Death of ourselves.”

The better part of two centuries after Langstroth’s hive went on sale, natural beekeepers liken much conventional beekeeping to industrial agriculture—permeated by chemicals and the delusion of human control. They dwell on the differences between the lives of wild, or free-living, bees and those which are kept in apiaries. Managed bees are typically kept in a drafty box low to the ground, as opposed to a snug nest high in a hollow tree. Most beekeepers’ colonies are much larger than those which occur in the wild, and rival colonies might be separated by only a few yards, rather than by half a mile. Much of the bees’ honey, which is supposed to get them through the winter, is taken before they have a chance to eat it. A queen bee goes on a spree of mating flights early in her life, and then lays the fertilized eggs until her death. In apiaries, queens often have their wings clipped, to interrupt swarming (a colony’s natural form of reproduction), and are routinely inspected, and replaced by newcomers, sometimes imported from the other side of the world. Propolis—a wonderful, sticky substance that bees make from tree resin and that has antibacterial qualities—is typically scraped out of hives by beekeepers because it is annoying and hard to get off their hands.

These are all dire interventions in the fabric of the colony. No wonder the bees keep dying. In a normal year, perhaps ten or fifteen per cent of bee colonies die in the winter. Last winter, America’s bees suffered colony losses of close to forty per cent, with varroa, “queen issues,” and starvation among the leading causes. High death rates tend to lead to more bee imports, more bee medication, more bee supplements, more bee-breeding programs, and the whole unwieldy cycle continues.

Natural beekeepers leave their bees alone. They seldom treat for disease—allowing the weaker colonies to fail—and they raise the survivors in conditions that are as close as possible to tree cavities. They fill their hives with swarms that come in on the wing, rather than those which come from dealers who trade on the Internet. They treasure the bees for their own sake—like a goldfinch that nests in the yard—and have an evangelical spirit, as if they have stumbled on a great secret. They are disdainful of conventional beekeepers. “They’ve completely lost sight of the creature,” John told me.

Honey is a touchy subject. John said that he harvests only an absolute excess—after the bees have enough for two winters and a wet summer—and even then he won’t take money for it. “It’s not my honey to sell,” he explained. Another natural beekeeper, who abstains from taking honey altogether, referenced “When Harry Met Sally” to explain his position: “There was this line, ‘Sex always gets in the way of friendship.’ I think honey always gets in the way of us appreciating bees.”

Bees were long held to be prophetic—messengers from another realm. The name of Deborah, the prophetess and judge of the Old Testament, translates as “bee.” The priestesses who tended the oracle at Delphi were known as Melissae. Melissa means “bee,” too. For a quarter century, anxiety about the fate of honeybees has been a manifestation of our unease about the state of pollinators and our biomes in general. But that doesn’t mean we have been interpreting the problems correctly, or that humans are the best placed to find solutions. Natural beekeepers think of themselves as deferring to the bees for guidance. “If I go to a hive and I put my hand on the hive . . . I can actually feel their presence, and that balance and that skill and that beauty that only nature can provide,” Jonathan Powell, of Britain’s Natural Beekeeping Trust, told me. “And yet if I think of a bee flying up to the window of my house, putting their antennae on my house, I’m frankly embarrassed by the way I live, and how clumsy and how stupid I am.”

In Oxfordshire, John led the way to his apiary, which was on a small pasture at the back of his property, bounded by high hedgerows. There was a lock on the gate and a small workshop, where he makes and maintains fifteen or so hives. A honeybee colony is a female commonwealth—a biological marvel of social decision-making by a queen and her thousands of female workers. (Beekeeping, by contrast, was for a long time a patriarchy. The monks of Mt. Athos, in Greece, were allowed to keep bees because the insects were assumed to be all male.)