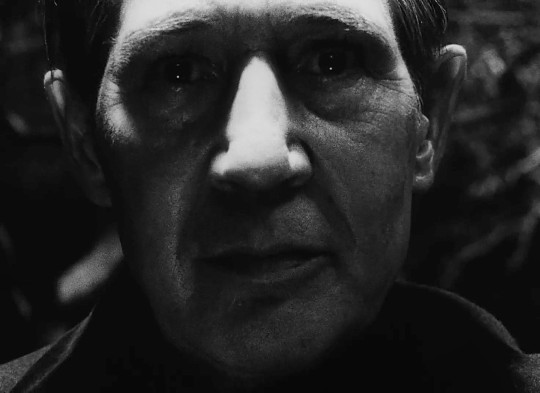

#georg rydeberg

Text

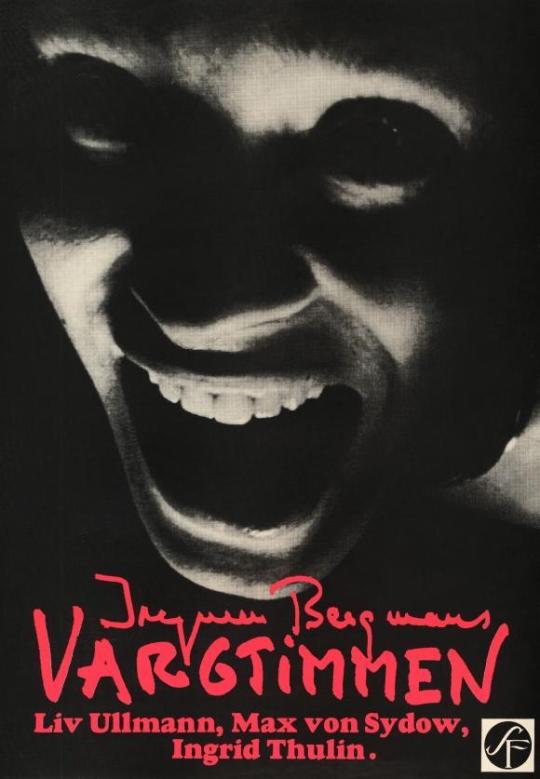

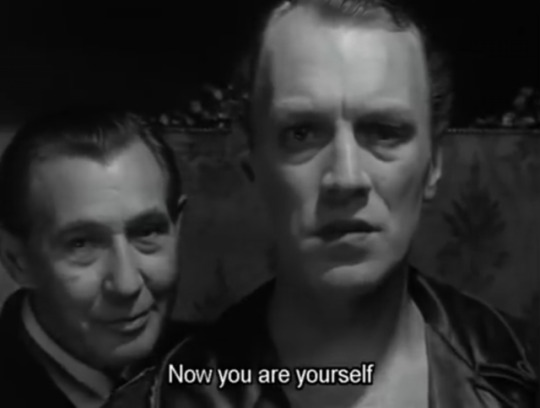

"Vargtimmen" (1968) - Ingmar Bergman

(Eng. title: "Hour of the Wolf")

Films I've watched in 2024 (12/?)

#films watched in 2024#Vargtimmen#Liv Ullmann#Max von Sydow#Naima Wifstrand#Erland Josephson#Gertrud Fridh#Georg Rydeberg#Ulf Johanson#Gudrun Brost#Bertil Anderberg#Ingmar Bergman#Sven Nykvist#Swedish film#Swedish cinema#black-and-white film#1960s film#1960s cinema#film GIFs#movie GIFs#film recommendations#movie recommendation#motionpicturelover's gifs

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

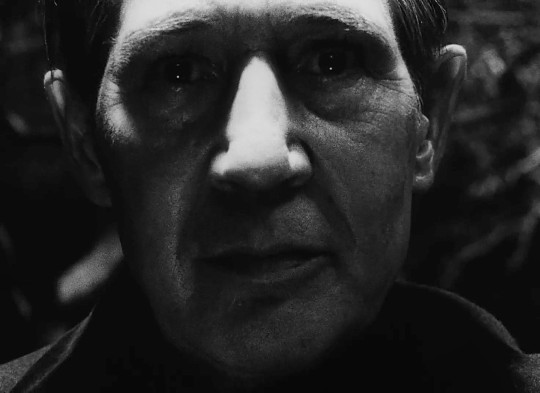

Georg Rydeberg could have been - and is in my head - Dracula.

#georg rydeberg#Dracula#vampire#vampiric#ingmar bergman#swedish cinema#Sweden#cinematography#hour of the wolf#vargtimmen

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hour of the Wolf (Ingmar Bergman, 1968)

Cast: Max von Sydow, Liv Ullmann, Gertrud Fridh, Georg Rydeberg, Erland Josephson, Naima Wilfstrand, Ulf Johansson, Gudrun Brost, Bertil Anderberg, Ingrid Thulin. Screenplay: Ingmar Bergman. Cinematography: Sven Sykvist. Production design: Marik Vos-Lundh. Film editing: Ulla Ryghe. Music: Lars Johan Werle.

Ingmar Bergman's Hour of the Wolf is unquestionably a "horror movie" -- i.e., one filled with incidents and images and narrative details aimed at shocking the viewer. It takes place on a remote island with a mysterious castle. Figures appear who may be either humans or demons. There's a scene in which a man walks up the wall and across the ceiling and one in which a woman peels off first her wig and then her face. The protagonist either murders or imagines that he has murdered a small boy. That protagonist is Johan Borg (Max von Sydow), an artist, who has come to the island with his wife, Alma (Liv Ullmann), to recover after an illness -- physical or mental, we're not told. Johan can't sleep, and Alma sits up with him at night while he tells her about the demons whose images he has sketched, so no wonder that her own mental state becomes fragile. One day, she meets an old woman who tells her that she should read Johan's diary, which he keeps under his bed. She does so, rather like Bluebeard's wife persisting in opening his castle's doors, uncovering some disturbing entries regarding his continued obsession with an old love, Veronica Vogler (Ingrid Thulin). They're invited to a dinner party at the castle by the baron (Erland Josephson), where they meet a variety of unlovely sophisticates and are entertained by a rather bizarre puppet show excerpt from Mozart's The Magic Flute (an opera that Bergman would film, in a less bizarre manner, seven years later). But the climax of the evening comes when the baroness (Gertrud Fridh) takes the Borgs to her bedroom to show off her prized possession: Johan's portrait of Veronica Vogler. From then on, it's a deep descent into madness for Johan and a desperate attempt by Alma to save both of them from self-destruction. The "creep factor" in Bergman's movies is never entirely missing, but Hour of the Wolf cranks it up higher than ever. The problem is that the creepiness is sustained almost to the point of tedium, and with a concomitant loss of credibility. The remote island setting prevents the film from grounding itself in normality, so that the action plays out on one sustained note of oppressive isolation. Hour of the Wolf has many admirers, who rightly point out that Bergman, with the considerable help of his actors and his cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, has crafted a nightmare of erotic obsession with the utmost skill. But I like to compare Hour of the Wolf to another horror movie released the same year, Roman Polanski's Rosemary's Baby, a "commercial" product aimed at a general audience, which suggests evil things going on beneath the surface of a commonplace urban setting, and ask which is the more successful: the sustained psychological oppressiveness of the Bergman film or the sinister mixture of comedy and shock of the Polanski movie?

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

georg rydeberg is like budget humphrey bogart

0 notes

Text

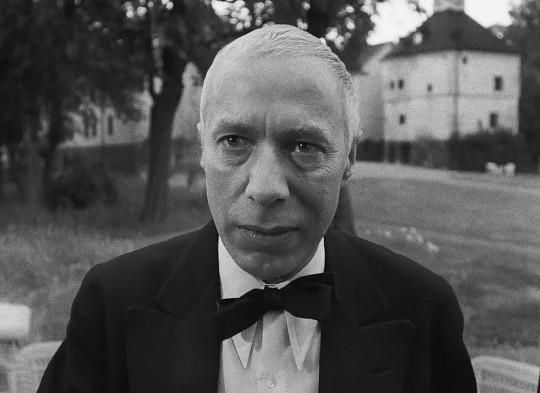

Två manniskor (Carl Th. Dreyer, 1944/5)

Film maldito de la entera aunque poco numerosa obra de Dreyer, no sólo rodado en plena guerra – en Suecia en lugar de la Dinamarca ocupada –, con medios visiblemente exiguos y actores no elegidos por el realizador (aunque no creo que tuviese queja de Wanda Rothgardt), de breve duración (pero enorme y claustrofóbica intensidad, tensión y giros), sino condenado por una mala reputación generada, cuando apenas nadie la había visto, por el mismísimo Dreyer, y ya se sabe que cuando ni el propio autor tiene nada bueno que decir, no van a molestarse en encontrarlo los críticos, ni van a atreverse a contradecir a uno de los maestros del cine. Y así ha sucedido, en general, pese a que a algunos – creo que conmigo sé de otros dos – encontramos que Två manniskor, sin ser tan grande como Gertrud (1964), Ordet (1954/5), Vredens Dag (1943), cosa no al alcance de muchas otras, no es inferior a Vampyr (1931/2) ni a las restantes de sus mejores películas, a menudo más célebres y apreciadas por su autor.

Si se piensa un poco, es raro que los cineastas sean buenos críticos, y más aún de su propia obra. En general, han imaginado o soñado unas imágenes, un ritmo, una fascinación, una fluidez, unos rostros que a menudo, por los más diversos motivos, no han logrado o podido conseguir. De ahí que a menudo se sientan insatisfechos hasta de sus mejores logros. Años después de Vertigo (1958), Hitchcock lamentaba haber tenido que usar a Kim Novak en lugar de Vera Miles, que puede ser mejor actriz pero mucho menos fascinante y misteriosa. De modo que, si uno se olvida de los reproches poco elocuentes de Dreyer, y la contempla sin prejuicios, con atención e interés, es posible encontrar en Två manniskor motivos sobrados para admirarla.

Comprimidas en poco más de hora y diez ejemplarmente tensa, Dreyer nos cuenta, en realidad, no dos sino tres vidas: la de Marianne (Wanda Rothgardt), su marido el científico Arne Lundell (Georg Rydeberg) y – muy elípticamente, pues sólo entrevemos su silueta sombreada, en un plano que recuerda Vampyr – su rival Sander. No se nos cuentan en orden ni sucesivamente, sino que se van desvelando a través de gestos y movimientos – a veces anticipados por un desplazamiento revelador de la cámara – de dos actores y del diálogo cambiante, de interrogatorio, de complicidad, de temor, de sorpresa, de confesión, de indignación, de desprecio, de arrepentimiento, de irrealista esperanza, de fatalismo, de la pareja, que a lo largo de esas diversas actitudes y tonalidades pasa revista a su relación de cuatro años, con sorpresas constantes de uno y otro, y del espectador. Nunca una casa – casi una habitación – se ha movido y agitado tanto internamente como lo hace el hogar-laboratorio de Arne y Marianne.

Es una película que puede hacer pensar en algunas de Alfred Hitchcock – Rebecca (1940), Suspicion (1941), e incluso que estaban todavía por hacer, como Notorious (1946), The Paradine Case (1947), Rope (1948), Under Capricorn (1949), Stage Fright (1950), Strangers on a Train (1951) y I Confess (1953) – o de Ingmar Bergman – Till glädje (1949/50), Sommarlek (1950/1), Sommaren med Monika (1952/3) o Kvinnodröm (1955) –, y que a mí me recuerda, en el cine más reciente, las películas de adultos (sin tema infantil o adolescente) del danés Nils Malmros. Es decir, que es fundamentalmente una película de suspense – cosa, si se me permite, nada nueva en Dreyer, desde Præsidenten (1919) hasta Gertrud -, y dramáticamente basada en el progresivo desvelamiento de la verdad oculta tras las apariencias, como Vampyr o Vredens Dag.

No se trata, por tanto, de una obra ajena ni a las preocupaciones de Dreyer ni a su más bien cambiante estilo – sobre todo, los saltos de La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1927/8) a Vampyr, y de Vampyr a Vredens Dag –, que invita al espectador a mirar muy atentamente cada mirada, cada gesto, cada detalle, cada movimiento, e incluso a sospechar o desconfiar de las apariencias – la celeridad con que Marianne quema el pañuelo manchado de sangre de Arne –, pendiente al mismo tiempo, como ellos, de los sonidos que llegan del exterior – ladridos, sirenas, frenos de coches, campanadas – y de los que proporciona la radio, música o noticias. A estas se agregan las que traen los periódicos, alguna llamada telefónica o un cartero. Pues resulta que Sander primero parece haberse suicidado, después resulta que ha sido asesinado, y que hay factores que convierten a Arne en sospechoso.

Y es un curioso detalle, que hoy sospecho impracticable en un guión, que todo estalle cuando, tras citar un poema y discrepar acerca de la literalidad de un verso, aparece en el libro que coge Arne para demostrar que él tenía razón una carta dirigida a Marianne, que él se empeña en leer pese a la resistencia de ella, y que resulta ser de Sander, el científico que ocupa un puesto superior al de Arne, que ha acusado a éste de haberle plagiado…y que resulta haber sido amante de Marianne, hasta que ella conoció a Arne. Esta revelación desmorona la confianza de Arne en su mujer, a la que insulta y expulsa de la casa. Hace así aparición el tema recurrente de Dreyer, la intolerancia, la sospecha, la súbita desconfianza, los interrogatorios implacables. Pero antes de que ella salga, Arne se echa a llorar y al final la perdona. Y es entonces cuando Marianne revela que fue ella quien mató a Sander, con la pistola y los guantes de Arne, que en realidad fue Sander quien copió el trabajo de Arne, facilitado bajo chantaje por Marianne, y que Sander pretendía que ella dejase a Arne y se casase con él. Planean entonces, totalmente ilusorios, huir juntos, pero Marianne se ha tomado un veneno, así que Arne se toma el resto y ambos se suicidan juntos, en un doble suicidio entre japonés y romántico, pero matizado críticamente por la petición de Arne de que Marianne le cante una nana en italiano, lo que a mi entender siembra dudas acerca de la madurez emocional del científico, que por otra parte parecía incapaz de sacar conclusiones de los abundantes indicios que permitían sospechar de la culpabilidad de Marianne. Un final que, por tanto, añade al clímax un signo de interrogación. Tras la compresión en poco más de 70 minutos de todo un melodrama argumental, pero tratado con sobria y escueta frialdad quirúrgica por Dreyer, surge la duda y se revela la debilidad de los personajes. Pienso que el cineasta no ha querido sublimar un final desesperanzado y un tanto inverosímil sin manifestar un cierto grado de reserva y escepticismo.

Miguel Marías

Escrito en 2010.

#miguel marías#Två manniskor#carl theodor dreyer#dreyer#1945#cine sueco#swedish cinema#artículo inédito

0 notes

Photo

La hora del lobo (Vargtimmen, Ingmar Bergman, 1968) / Carretera perdida (Lost Highway, David Lynch, 1997)

#la hora del lobo#vargtimmen#ingmar bergman#carretera perdida#lost highway#david lynch#robert blake#georg rydeberg#horror#horror movies#terror#cine de terror

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

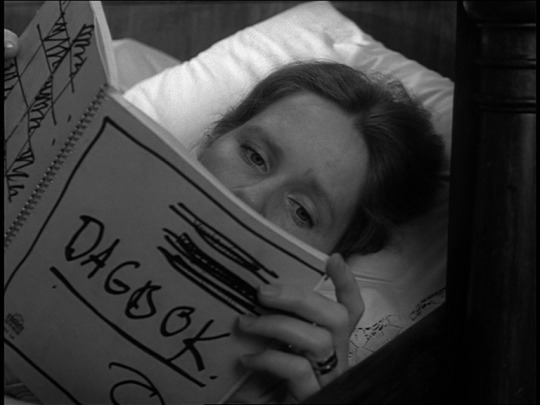

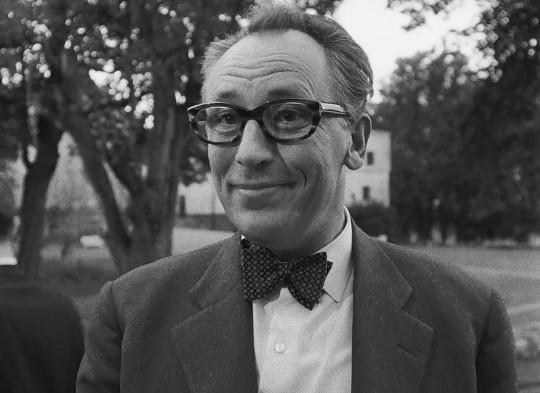

Hour of the Wolf / Vargtimmen (1968, Ingmar Bergman)

8/2/18

#60s#Hour of the Wolf#Ingmar Bergman#Max von Sydow#Liv Ullmann#Erland Josephson#Georg Rydeberg#Ingrid Thulin#drama#horror#Swedish#European Art House#island#artists#castle#flashbacks#gothic#surreal#rich people#old flame#black and white#mystery#murder#demons

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Two People (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1945)

#two people#quote#love#kiss#carl theodor dreyer#dreyer#1945#black and white#Tva manniskor#Två människor#Wanda Rothgardt#Georg Rydeberg#lies

532 notes

·

View notes

Text

4.27.19

#letterboxd#watched#film#hour of the wolf#ingmar bergman#ingrid thulin#gudrun brost#ulf johansson#naima wifstrand#erland josephson#georg rydeberg#gertrud fridh#liv ullmann#max von sydow

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hour of the Wolf (1968), dir. Ingmar Bergman

31 notes

·

View notes

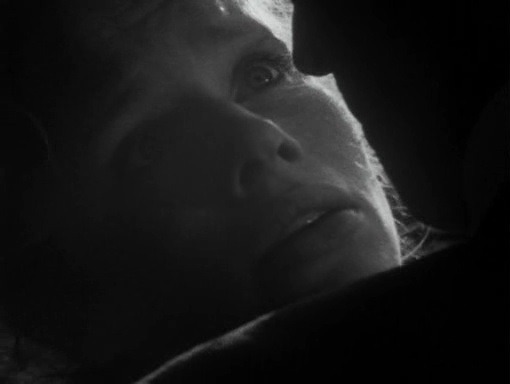

Photo

Vargtimmen (Hour of the Wolf) | Ingmar Bergman | 1968

Georg Rydeberg, Liv Ullmann, Folke Sundquist

#Georg Rydeberg#Liv Ullmann#Folke Sundquist#Ingmar Bergman#Bergman#Vargtimmen#Hour of the Wolf#1968#BF2018

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Vargtimmen" (1968) - Ingmar Bergman

Films I've watched in 2022 (131/210)

#films watched in 2022#Vargtimmen#Liv Ullmann#Max von Sydow#Naima Wifstrand#Georg Rydeberg#Gertrud Fridh#Erland Josephson#Ingmar Bergman#Sven Nykvist#film#Swedish cinema#Swedish film#black and white film#The Hour of the Wolf#motionpicturelover's screencaps

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Två människor (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1945)

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I shall remember this moment: the silence, the twilight, the bowl of strawberries, the bowl of milk. Your faces in the evening light. Mikael asleep, Jof with his lyre. I shall try to remember our talk. I shall carry this memory carefully in my hands as if it were a bowl brimful of fresh milk. It will be a sign to me, and a great sufficiency.

Born Carl Adolf von Sydow, Swedish actor Max von Sydow passed away yesterday at his home in southern France. With a career spanning eight decades, the towering and lanky von Sydow distinguished himself in Hollywood, usually seen playing villains through the 1970s and ‘80s. But he was perhaps most widely acclaimed for his work in Swedish films with directors Ingmar Bergman and Jan Troell – the former, shortly before his death in 2007, described the actor thusly: “Max, you have been the first and the best Stradivarius that I have ever had in my hands.” The role that catapulted von Sydow to international fame was as Antonius Block, a returning Crusader who plays chess with Death (often parodied and referenced), in Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. In recent years, von Sydow described himself as an actor without a home nation, in due part due to his globetrotting film career and his sons attending American universities.

An actor of incredible gravitas and often embodying existential angst and resolve simultaneously, von Sydow fulfilled a lifelong passion that began when he saw a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream as a schoolboy in his hometown of Lund. Younger viewers and gamers may know him best as Three-eyed Raven from Game of Thrones and the voice actor of Esbern in The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, respectively. In life, one of the greatest screen actors of the last century touched audiences in countless ways that few non-Americans and non-British actors could, no matter the project.

Nine of the films Max von Sydow appeared in are shown above, and are listed below (left-right, descending):

The Virgin Spring (1960, Sweden) – directed by Ingmar Bergman; also starring Birgitta Valberg, Gunnel Lindblom, and Birgitta Pettersson

The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965) – directed by George Stevens; also starring Dorothy McGuire, Charlton Heston, José Ferrer, and Telly Savalas

Hour of the Wolf (1968, Sweden) – directed by Ingmar Bergman; also starring Liv Ullmann, Gertrud Fridh, Georg Rydeberg, Erland Josephson, and Ingrid Thulin

The Emigrants (1971, Sweden) – directed by Jan Troell; also starring Liv Ullmann, Eddie Axberg, and Monica Zetterlund

The Exorcist (1973) – directed by William Friedkin; also starring Ellen Burstyn, Lee J. Cobb, Kitty Winn, Jack MacGowran, Jason Miller, and Linda Blair

Pelle the Conqueror (1987, Denmark/Sweden) – directed by Bille August; also starring Pelle Hvenegaard, Erik Paaske, and Bjørn Granath

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (2007, France) – directed by Julian Schnabel; also starring Mathieu Amalric, Emmanuelle Seigner, Marie-Josée Croze, and Anne Consigny

Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015) – directed by J.J. Abrams; also starring Harrison Ford, Mark Hamill, Carrie Fisher, Adam Driver, Daisy Ridley, John Boyega, and Oscar Isaac

The Seventh Seal (1957, Sweden) – directed by Ingmar Bergman; also starring Gunnar Björnstrand, Bengt Ekerot, Nils Poppe, Bibi Andersson, Inga Landgré, and Åke Fridell

#Max von Sydow#The Seventh Seal#The Force Awakens#The Exorcist#Ingmar Bergman#The Virgin Spring#The Greatest Story Ever Told#Hour of the Wolf#Pelle the Conqueror#The Diving Bell and the Butterfly#Star Wars#in memoriam

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hour of the Wolf (1968)

An artist in crisis is haunted by nightmares from the past in Ingmar Bergman's only horror film, which takes place on a windy island... (imdb)

Genres: Drama, Horror

AKA: Vargtimmen

Country: Sweden

Directed By: Ingmar Bergman

Written By: Ingmar Bergman

Starring: Max von Sydow, Erland Josephson, Liv Ullmann, Ingrid Thulin, Gertrud Fridh, Georg Rydeberg, Naima Wifstrand, Gudrun Brost, Bertil Anderberg, Ulf Johansson

0 notes

Photo

La hora del lobo (Vargtimmen, Ingmar Bergman, 1968)

#la hora del lobo#vargtimmen#ingmar bergman#horror#horror movies#1960s#60s#60s movies#1960s movies#swedish movies#swedish cinema#max von sydow#erland josephson#liv ullman#ingrid thulin#georg rydeberg#naima wifstrand#ulf johansson#gudrun brost#bertil anderberg

7 notes

·

View notes