#ftc act section 5

Text

Tesla's Dieselgate

Elon Musk lies a lot. He lies about being a “utopian socialist.” He lies about being a “free speech absolutist.” He lies about which companies he founded:

https://www.businessinsider.com/tesla-cofounder-martin-eberhard-interview-history-elon-musk-ev-market-2023-2

He lies about being the “chief engineer” of those companies:

https://www.quora.com/Was-Elon-Musk-the-actual-engineer-behind-SpaceX-and-Tesla

He lies about really stupid stuff, like claiming that comsats that share the same spectrum will deliver steady broadband speeds as they add more users who each get a narrower slice of that spectrum:

https://www.eff.org/wp/case-fiber-home-today-why-fiber-superior-medium-21st-century-broadband

The fundamental laws of physics don’t care about this bullshit, but people do. The comsat lie convinced a bunch of people that pulling fiber to all our homes is literally impossible — as though the electrical and phone lines that come to our homes now were installed by an ancient, lost civilization. Pulling new cabling isn’t a mysterious art, like embalming pharaohs. We do it all the time. One of the poorest places in America installed universal fiber with a mule named “Ole Bub”:

https://www.newyorker.com/tech/annals-of-technology/the-one-traffic-light-town-with-some-of-the-fastest-internet-in-the-us

Previous tech barons had “reality distortion fields,” but Musk just blithely contradicts himself and pretends he isn’t doing so, like a budget Steve Jobs. There’s an entire site devoted to cataloging Musk’s public lies:

https://elonmusk.today/

But while Musk lacks the charm of earlier Silicon Valley grifters, he’s much better than they ever were at running a long con. For years, he’s been promising “full self driving…next year.”

https://pluralistic.net/2022/10/09/herbies-revenge/#100-billion-here-100-billion-there-pretty-soon-youre-talking-real-money

He’s hasn’t delivered, but he keeps claiming he has, making Teslas some of the deadliest cars on the road:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/06/10/tesla-autopilot-crashes-elon-musk/

Tesla is a giant shell-game masquerading as a car company. The important thing about Tesla isn’t its cars, it’s Tesla’s business arrangement, the Tesla-Financial Complex:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/11/24/no-puedo-pagar-no-pagara/#Rat

Once you start unpacking Tesla’s balance sheets, you start to realize how much the company depends on government subsidies and tax-breaks, combined with selling carbon credits that make huge, planet-destroying SUVs possible, under the pretense that this is somehow good for the environment:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/04/14/for-sale-green-indulgences/#killer-analogy

But even with all those financial shenanigans, Tesla’s got an absurdly high valuation, soaring at times to 1600x its profitability:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/01/15/hoover-calling/#intangibles

That valuation represents a bet on Tesla’s ability to extract ever-higher rents from its customers. Take Tesla’s batteries: you pay for the battery when you buy your car, but you don’t own that battery. You have to rent the right to use its full capacity, with Tesla reserving the right to reduce how far you go on a charge based on your willingness to pay:

https://memex.craphound.com/2017/09/10/teslas-demon-haunted-cars-in-irmas-path-get-a-temporary-battery-life-boost/

That’s just one of the many rent-a-features that Tesla drivers have to shell out for. You don’t own your car at all: when you sell it as a used vehicle, Tesla strips out these features you paid for and makes the next driver pay again, reducing the value of your used car and transfering it to Tesla’s shareholders:

https://www.theverge.com/2020/2/6/21127243/tesla-model-s-autopilot-disabled-remotely-used-car-update

To maintain this rent-extraction racket, Tesla uses DRM that makes it a felony to alter your own car’s software without Tesla’s permission. This is the root of all autoenshittification:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/07/24/rent-to-pwn/#kitt-is-a-demon

This is technofeudalism. Whereas capitalists seek profits (income from selling things), feudalists seek rents (income from owning the things other people use). If Telsa were a capitalist enterprise, then entrepreneurs could enter the market and sell mods that let you unlock the functionality in your own car:

https://pluralistic.net/2020/06/11/1-in-3/#boost-50

But because Tesla is a feudal enterprise, capitalists must first secure permission from the fief, Elon Musk, who decides which companies are allowed to compete with him, and how.

Once a company owns the right to decide which software you can run, there’s no limit to the ways it can extract rent from you. Blocking you from changing your device’s software lets a company run overt scams on you. For example, they can block you from getting your car independently repaired with third-party parts.

But they can also screw you in sneaky ways. Once a device has DRM on it, Section 1201 of the DMCA makes it a felony to bypass that DRM, even for legitimate purposes. That means that your DRM-locked device can spy on you, and because no one is allowed to explore how that surveillance works, the manufacturer can be incredibly sloppy with all the personal info they gather:

https://www.cnbc.com/2019/03/29/tesla-model-3-keeps-data-like-crash-videos-location-phone-contacts.html

All kinds of hidden anti-features can lurk in your DRM-locked car, protected from discovery, analysis and criticism by the illegality of bypassing the DRM. For example, Teslas have a hidden feature that lets them lock out their owners and summon a repo man to drive them away if you have a dispute about a late payment:

https://tiremeetsroad.com/2021/03/18/tesla-allegedly-remotely-unlocks-model-3-owners-car-uses-smart-summon-to-help-repo-agent/

DRM is a gun on the mantlepiece in Act I, and by Act III, it goes off, revealing some kind of ugly and often dangerous scam. Remember Dieselgate? Volkswagen created a line of demon-haunted cars: if they thought they were being scrutinized (by regulators measuring their emissions), they switched into a mode that traded performance for low emissions. But when they believed themselves to be unobserved, they reversed this, emitting deadly levels of NOX but delivering superior mileage.

The conversion of the VW diesel fleet into mobile gas-chambers wouldn’t have been possible without DRM. DRM adds a layer of serious criminal jeopardy to anyone attempting to reverse-engineer and study any device, from a phone to a car. DRM let Apple claim to be a champion of its users’ privacy even as it spied on them from asshole to appetite:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/11/14/luxury-surveillance/#liar-liar

Now, Tesla is having its own Dieselgate scandal. A stunning investigation by Steve Stecklow and Norihiko Shirouzu for Reuters reveals how Tesla was able to create its own demon-haunted car, which systematically deceived drivers about its driving range, and the increasingly desperate measures the company turned to as customers discovered the ruse:

https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/tesla-batteries-range/

The root of the deception is very simple: Tesla mis-sells its cars by falsely claiming ranges that those cars can’t attain. Every person who ever bought a Tesla was defrauded.

But this fraud would be easy to detect. If you bought a Tesla rated for 353 miles on a charge, but the dashboard range predictor told you that your fully charged car could only go 150 miles, you’d immediately figure something was up. So your Telsa tells another lie: the range predictor tells you that you can go 353 miles.

But again, if the car continued to tell you it has 203 miles of range when it was about to run out of charge, you’d figure something was up pretty quick — like, the first time your car ran out of battery while the dashboard cheerily informed you that you had 203 miles of range left.

So Teslas tell a third lie: when the battery charge reached about 50%, the fake range is replaced with the real one. That way, drivers aren’t getting mass-stranded by the roadside, and the scam can continue.

But there’s a new problem: drivers whose cars are rated for 353 miles but can’t go anything like that far on a full charge naturally assume that something is wrong with their cars, so they start calling Tesla service and asking to have the car checked over.

This creates a problem for Tesla: those service calls can cost the company $1,000, and of course, there’s nothing wrong with the car. It’s performing exactly as designed. So Tesla created its boldest fraud yet: a boiler-room full of anti-salespeople charged with convincing people that their cars weren’t broken.

This new unit — the “diversion team” — was headquartered in a Nevada satellite office, which was equipped with a metal xylophone that would be rung in triumph every time a Tesla owner was successfully conned into thinking that their car wasn’t defrauding them.

When a Tesla owner called this boiler room, the diverter would run remote diagnostics on their car, then pronounce it fine, and chide the driver for having energy-hungry driving habits (shades of Steve Jobs’s “You’re holding it wrong”):

https://www.wired.com/2010/06/iphone-4-holding-it-wrong/

The drivers who called the Diversion Team weren’t just lied to, they were also punished. The Tesla app was silently altered so that anyone who filed a complaint about their car’s range was no longer able to book a service appointment for any reason. If their car malfunctioned, they’d have to request a callback, which could take several days.

Meanwhile, the diverters on the diversion team were instructed not to inform drivers if the remote diagnostics they performed detected any other defects in the cars.

The diversion team had a 750 complaint/week quota: to juke this stat, diverters would close the case for any driver who failed to answer the phone when they were eventually called back. The center received 2,000+ calls every week. Diverters were ordered to keep calls to five minutes or less.

Eventually, diverters were ordered to cease performing any remote diagnostics on drivers’ cars: a source told Reuters that “Thousands of customers were told there is nothing wrong with their car” without any diagnostics being performed.

Predicting EV range is an inexact science as many factors can affect battery life, notably whether a journey is uphill or downhill. Every EV automaker has to come up with a figure that represents some kind of best guess under a mix of conditions. But while other manufacturers err on the side of caution, Tesla has the most inaccurate mileage estimates in the industry, double the industry average.

Other countries’ regulators have taken note. In Korea, Tesla was fined millions and Elon Musk was personally required to state that he had deceived Tesla buyers. The Korean regulator found that the true range of Teslas under normal winter conditions was less than half of the claimed range.

Now, many companies have been run by malignant narcissists who lied compulsively — think of Thomas Edison, archnemesis of Nikola Tesla himself. The difference here isn’t merely that Musk is a deeply unfit monster of a human being — but rather, that DRM allows him to defraud his customers behind a state-enforced opaque veil. The digital computers at the heart of a Tesla aren’t just demons haunting the car, changing its performance based on whether it believes it is being observed — they also allow Musk to invoke the power of the US government to felonize anyone who tries to peer into the black box where he commits his frauds.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/07/28/edison-not-tesla/#demon-haunted-world

This Sunday (July 30) at 1530h, I’m appearing on a panel at Midsummer Scream in Long Beach, CA, to discuss the wonderful, award-winning “Ghost Post” Haunted Mansion project I worked on for Disney Imagineering.

Image ID [A scene out of an 11th century tome on demon-summoning called 'Compendium rarissimum totius Artis Magicae sistematisatae per celeberrimos Artis hujus Magistros. Anno 1057. Noli me tangere.' It depicts a demon tormenting two unlucky would-be demon-summoners who have dug up a grave in a graveyard. One summoner is held aloft by his hair, screaming; the other screams from inside the grave he is digging up. The scene has been altered to remove the demon's prominent, urinating penis, to add in a Tesla supercharger, and a red Tesla Model S nosing into the scene.]

Image:

Steve Jurvetson (modified)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tesla_Model_S_Indoors.jpg

CC BY 2.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#steve stecklow#autoenshittification#norihiko shirouzu#reuters#you're holding it wrong#r2r#right to repair#range rage#range anxiety#grifters#demon-haunted world#drm#tpms#1201#dmca 1201#tesla#evs#electric vehicles#ftc act section 5#unfair and deceptive practices#automotive#enshittification#elon musk

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

Last week, Mashable reported that on X (formerly Twitter), users were noticing a new type of advertisement: Minus a regular handle or username, the ad’s headline looks like a normal tweet, with the avatar a miniature of whatever featured image appears in the body of the post. There is no notification in the upper right-hand corner saying “Ad,” and users can’t click on the ad to see more about who paid for it.

“Dude what the fuck is this I can’t click on it there’s no account name there’s no username I’m screaming what the hell it’s not even an ad,” one user tweeted. But Twitter’s new ad interface may be more than just annoying—it may be illegal.

Under Section 5(a) of the US Federal Trade Commission Act, companies are banned from using deceptive ad practices, meaning consumers must know that ads are, well, ads. For social platforms, this means that any native advertising, or advertising designed to look like content on the platform, needs to be clearly labeled.

“There’s really no doubt to us that X’s lack of disclosure here misleads consumers,” says Sarah Kay Wiley, policy and partnerships director at Check My Ads, an ad industry watchdog group. “Consumers are simply not able to differentiate what is content and what is not paid content. Even I’ve been duped, and I work in this space.”

X did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

X has two feeds, a Following feed that is meant to show users content from accounts they follow and a For You feed that includes algorithmically recommended content from across the platform. Wiley says she has seen examples of this unlabeled ad content in both feeds. What’s more confusing is the fact that some other content is still labeled as ads. “It’s really egregious because some ads are still marked as ads,” says Wiley. “It really provides opportunities for fraudulent marketers to reach consumers.”

An FTC staff attorney with the agency’s ad practices division, who spoke to WIRED on condition of anonymity, says that the agency encourages platforms to use a consistent format for advertising disclosures in order to avoid confusing customers.

And Wiley says that if advertisers think X is doing the work of labeling their content when it’s not, they could also face compliance issues for not properly disclosing that their posts are ads. “The advertisers themselves are also victims,” she says.

It’s no secret that X has been scrambling to bring in ad revenue. After Elon Musk took ownership of the company, he publicly declared that it would roll back content moderation efforts and fired much of the staff responsible for this work. Brands, worried that their ads would appear next to disinformation or hateful content, began abandoning the platform. Musk has tried to turn the ship around, bringing in CEO Linda Yaccarino, an experienced advertising executive (who Musk has repeatedly undermined, acting in ways that go against her promises to make the platform safe for advertisers). But recent data shows that the platform has seen a 42 percent drop in ad revenue since Musk’s takeover. X has also begun selling ads via Google Ad Manager and InMobi, a marked shift from its historical practice of dealing with advertisers directly.

And it gets even more complicated—and thorny—for X. In 2011, then-Twitter was issued a consent decree, which would allow the government to take legal action against the company for not safeguarding user data, thereby making it vulnerable to hackers. As part of the settlement with the FTC, “Twitter will be barred for 20 years from misleading consumers about the extent to which it protects the security, privacy, and confidentiality of nonpublic consumer information,” the FTC stated at the time.

Showing users ads that they don’t know are ads would likely put the company in violation of this agreement, says Christopher Terry, associate professor of media law at the University of Minnesota.

“The whole point of putting native advertising is to slap a cookie on your computer that then makes you subject to all kinds of horrific other advertising,” says Terry. If X collects data from clicks on content that users don’t know are ads, that’s likely a violation of the company’s agreement to protect user data—and the consent decree, he says.

While it’s likely that the FTC could have grounds to come after X, Terry says he’s not sure the agency will prioritize the platform, noting the agency’s current focus on antitrust actions against Google and Amazon. In May, however, the agency ordered several social media companies, including X, to disclose how they were keeping fraudulent ads off their platforms. And Terry says that if the FTC decides to pursue X, Musk and his company could be in real trouble.

“You can screw with all these people. You can put up all this white supremacist content you want, but you really don’t want to mess with the FTC,” says Terry. “Because if they come knocking, you’re going to be really sorry you bought this company.”

0 notes

Text

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Files a Complaint Against Amazon Inc.

By Summer Lee, University of Colorado Boulder Class of 2023

October 4, 2023

Each year, Amazon generates billions of dollars in revenue from sales on its online e-commerce platform. In 2022, Statista estimated that Amazon’s net worth is over $1.1 trillion, ranking among one of the top three companies globally. However, as Amazon maintains its status as one of the largest companies in the world, there are increased concerns regarding how other online retailers and businesses can compete and participate in the e-commerce market.

On September 26, 2023, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and seventeen states filed a lawsuit against Amazon Inc. for engaging in monopolistic behavior and anti-competition tactics which pose a negative impact towards other online consumers and sellers. The plaintiff parties also appealed to Section 5(a) of the FTC Act, 15 U.S.C. § 45(a) to argue how Amazon’s business practices exemplify acts of unfair competition in the e-commerce market. In response to these allegations, Amazon argued the contrary, claiming that its company’s business model does in fact support competitive market practices. Both the plaintiff’s and defendant parties’ allegations referred to Amazon’s treatment of its sellers along with the implications of the conditional contracts poised towards potential Amazon sellers.

For full article please visit

An Overview of the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) Anti-Trust Lawsuit Against Amazon

at

Colorado PreLaw Land

0 notes

Text

An Overview of the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) Anti-Trust Lawsuit Against Amazon

By Summer Lee, University of Colorado Boulder Class of 2023

October 2, 2023

On September 26, 2023, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and seventeen states filed a lawsuit against Amazon.com, Inc. for engaging in monopolistic marketing practices and preventing other companies from competing in the market. The FTC claimed that Amazon has employed several anti-competition strategies to maintain its influence in the market, such as anti-discounting tactics, seller punishments and conditional contracts, along with the use of a price tracking and adjusting algorithm [1].

Appealing to Section 2 of the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. § 2, the FTC asserted that Amazon’s use of anti-discounting tactics is detrimental to other online retailers because it prevents them from offering goods at lower prices. By using marketing algorithms to track product discounts on the internet, Amazon penalizes its sellers that offer the same product at a higher price. When affiliated sellers sell their products for a lower price outside of Amazon.com, Amazon removes the “Buy Box” box display, which allows consumers to add a product to their shopping cart or purchase it right away. In addition, Amazon can also place sellers at the very bottom of the website’s search results to prevent consumers from viewing their products. The FTC stated how Amazon’s tactics of removing the “Buy Box” and placing sellers at the bottom of Amazon’s search results is detrimental to the seller because it causes their sales to significantly decrease. The FTC also argued that since the anti-discounting tactics set Amazon’s inflated prices as the new price floor for online shopping, consumers are paying higher prices for online goods and services offered by Amazon or other online retailers than they usually would [1].

The FTC also emphasized how Amazon’s use of coercive conditional contracts affects sellers’ competitiveness on the online market. In order to have orders fulfilled by Amazon, Amazon requires sellers’ products to be eligible for Amazon Prime shipping. The FTC commented on how Amazon implements this policy to accommodate Amazon Prime members, who make up a majority of the company’s customer base. The FTC also referred to the antitrust investigations that were conducted by European and U.S. regulators in 2022 and 2019 to emphasize on Amazon’s past anti-competition policies [1].

The FTC also claimed that Amazon’s use of an algorithm called Project Nessie does not comply with Section 5(a) of the FTC Act, 15 U.S.C. § 45(a), which prohibits acts of unfair competition [1]. Although the FTC has not publicly released additional information yet, author and journalist Jason Del Rey stipulates that Project Nessie could be an algorithm that collects data on prices from a variety of different online retailers and lowers the prices of goods on Amazon to match with its competitors [2].

In response to the FTC’s allegations, Amazon asserted that its business practices do support consumers and sellers alike. On Amazon’s news website, the company alleges that sellers can set their prices independently and that the company offers educational tools and resources to help them provide competitive prices [3]. Amazon then appeals to its relationships with its customers, arguing that the company only displays a list of sellers that can offer competitive prices to “maintain customer trust”. In response to the FTC’s complaints, Amazon also emphasized how advertising and Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) services are completely optional [3].

Although the estimated settlement date for the case is unknown, George Washington University law professor William E. Kovacic states that the FTC’s ability to win the case will depend on how long it will take to go on trial [4].

______________________________________________________________

[1] Graham, V. (2023, September 26). FTC sues Amazon for illegally maintaining monopoly power. Federal Trade Commission. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2023/09/ftc-sues-amazon-illegally-maintaining-monopoly-power

[2] Bishop, T. (2023, September 26). FTC Targets Alleged Secret Amazon Pricing Algorithm “Project Nessie” in Antitrust Complaint. GeekWire. https://www.geekwire.com/2023/ftc-targets-alleged-secret-amazon-pricing-algorithm-project-nessie-in-antitrust-complaint/

[3] David Zapolsky, S. V. P. (2023, September 26). The FTC’s Lawsuit Against Amazon Would Lead to Higher Prices and Slower Deliveries for Consumers-and Hurt Businesses. Amazon Company News. https://www.aboutamazon.com/news/company-news/amazon-ftc-antitrust-lawsuit-full-response.

[4] Zakrzewski, C., Oremus, W., & Thadani, T. (2023, September 26). U.S., 17 States Sue Amazon Alleging Monopolistic Practices Led to Higher Prices. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/09/26/amazon-antitrust-lawsuit-ftc/

0 notes

Text

GPT-4 poses too many risks and releases should be halted, AI group tells FTC

Getty Images | VCG

A nonprofit AI research group wants the Federal Trade Commission to investigate OpenAI, Inc. and halt releases of GPT-4.

OpenAI "has released a product GPT-4 for the consumer market that is biased, deceptive, and a risk to privacy and public safety. The outputs cannot be proven or replicated. No independent assessment was undertaken prior to deployment," said a complaint to the FTC submitted today by the Center for Artificial Intelligence and Digital Policy (CAIDP).

Calling for "independent oversight and evaluation of commercial AI products offered in the United States," CAIDP asked the FTC to "open an investigation into OpenAI, enjoin further commercial releases of GPT-4, and ensure the establishment of necessary guardrails to protect consumers, businesses, and the commercial marketplace."

Noting that the FTC "has declared that the use of AI should be 'transparent, explainable, fair, and empirically sound while fostering accountability,'" the nonprofit group argued that "OpenAI's product GPT-4 satisfies none of these requirements."

GPT-4 was unveiled by OpenAI on March 14 and is available to subscribers of ChatGPT Plus. Microsoft's Bing is already using GPT-4. OpenAI called GPT-4 a major advance, saying it "passes a simulated bar exam with a score around the top 10 percent of test takers," compared to the bottom 10 percent of test takers for GPT-3.5.

Though OpenAI said it had external experts assess potential risks posed by GPT-4, CAIDP isn't the first group to raise concerns about the AI field moving too fast. As we reported yesterday, the Future of Life Institute published an open letter urging AI labs to "immediately pause for at least 6 months the training of AI systems more powerful than GPT-4." The letter's long list of signers included many professors alongside some notable tech-industry names like Elon Musk and Steve Wozniak.

Group claims GPT-4 violates the FTC Act

CAIDP said the FTC should probe OpenAI using its authority under Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act to investigate, prosecute, and prohibit "unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce." The group claims that "the commercial release of GPT-4 violates Section 5 of the FTC Act, the FTC's well-established guidance to businesses on the use and advertising of AI products, as well as the emerging norms for the governance of AI that the United States government has formally endorsed and the Universal Guidelines for AI that leading experts and scientific societies have recommended."

The FTC should "halt further commercial deployment of GPT by OpenAI," require independent assessment of GPT products prior to deployment and "throughout the GPT AI lifecycle," "require compliance with FTC AI Guidance" before future deployments, and "establish a publicly accessible incident reporting mechanism for GPT-4 similar to the FTC's mechanisms to report consumer fraud," the group said.

More broadly, CAIDP urged the FTC to issue rules requiring "baseline standards for products in the Generative AI market sector."

We contacted OpenAI and will update this article if we get a response.

“OpenAI has not disclosed details”

CAIDP's president and founder is Marc Rotenberg, who previously co-founded and led the Electronic Privacy Information Center. Rotenberg is also an adjunct professor at Georgetown Law and served on the Expert Group on AI run by the international Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

CAIDP's chair and research director is Merve Hickok, who is also a data ethics lecturer at the University of Michigan. She testified in a congressional hearing about AI on March 8. CAIDP's list of team members includes many other people involved in technology, academia, privacy, law, and research fields.

The FTC last month warned companies to analyze "the reasonably foreseeable risks and impact of your AI product before putting it on the market." The agency also raised various concerns about "AI harms such as inaccuracy, bias, discrimination, and commercial surveillance creep" in a report to Congress last year.

GPT-4 poses many types of risks, and its underlying technology hasn't been adequately explained, CAIDP told the FTC. "OpenAI has not disclosed details about the architecture, model size, hardware, computing resources, training techniques, dataset construction, or training methods," the CAIDP complaint said. "The practice of the research community has been to document training data and training techniques for Large Language Models, but OpenAI chose not to do this for GPT-4."

"Generative AI models are unusual consumer products because they exhibit behaviors that may not have been previously identified by the company that released them for sale," the group also said.

0 notes

Text

FTC Expands its Scope of “Unfair Methods of Competition”

FTC Expands its Scope of “Unfair Methods of Competition”

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) released a new Policy Statement that widens what the commission considers “unfair methods of competition” under Section 5 of the FTC Act. This new statement is intended to increase enforcement of policing unfair practices, but some legal analysts see it as a way for the commission to decide on what constitutes “unfair” regardless of whether the conduct violates…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

In 2015, however, the Commission issued a statement declaring that it would apply Section 5 using the Sherman Act “rule of reason” test, which asks whether a given restraint of trade is “reasonable” in economic terms. The new statement replaces that policy and explains that limiting Section 5 to the rule of reason contradicted the text of the statute and Congress’s clear desire for it to go beyond the Sherman Act.

"in the case of law, the application of a norm is in no way contained within the norm and cannot be derived from it (...) Just as between language and world, so between the norm and its application there is no internal nexus that allows one to be derived immediately from the other" —Giorgio Agamben, State of Exception

0 notes

Text

Remotely created checks

In the supplementary information, the FTC states that it deleted the signature reference from the final rule’s definition due to concerns about the use of signature images to circumvent the prohibition.) (The FTC’s proposal defined both terms to only include “unsigned” payment orders or checks. In the supplementary information accompanying the final rule, the FTC states that it found the banned payment methods to be “abusive” because their use met the test for an “unfair” act or practice in Section 5 of the FTC Act.Īs defined by the final rule, a “remotely created payment order” means “any payment instruction or order drawn on a person’s account that is (a) created by the payee or the payee’s agent and (b) deposited into or cleared through the check clearing system.” While the FTC’s proposal separately defined the term “remotely created check,” the final rule provides that a “remotely created payment order” includes a “remotely created check” as defined in Regulation CC (which implements the Expedited Funds Availability Act), but does not include a payment order cleared through the Automated Clearinghouse (ACH) Network or that is subject to the Truth in Lending Act (TILA). The TSR implements the Telemarketing and Consumer Fraud and Abuse Prevention Act, which authorizes the FTC to prescribe rules prohibiting deceptive and “other abusive” telemarketing acts or practices. The new prohibitions will be effective 180 days after the final rule's publication in the Federal Register while other TSR changes made by the final rule will be effective 60 days after publication. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has finalized changes to its telemarketing sales rule (TSR) that will prohibit sellers and telemarketers from creating or accepting remotely created payment orders or checks, cash-to-cash money transfers, and cash reload mechanisms as payment in inbound and outbound telemarketing transactions.

0 notes

Text

Big Tech’s “attention rents”

Tomorrow (Nov 4), I'm keynoting the Hackaday Supercon in Pasadena, CA.

The thing is, any feed or search result is "algorithmic." "Just show me the things posted by people I follow in reverse-chronological order" is an algorithm. "Just show me products that have this SKU" is an algorithm. "Alphabetical sort" is an algorithm. "Random sort" is an algorithm.

Any process that involves more information than you can take in at a glance or digest in a moment needs some kind of sense-making. It needs to be put in some kind of order. There's always gonna be an algorithm.

But that's not what we mean by "the algorithm" (TM). When we talk about "the algorithm," we mean a system for ordering information that uses complex criteria that are not precisely known to us, and than can't be easily divined through an examination of the ordering.

There's an idea that a "good" algorithm is one that does not seek to deceive or harm us. When you search for a specific part number, you want exact matches for that search at the top of the results. It's fine if those results include third-party parts that are compatible with the part you're searching for, so long as they're clearly labeled. There's room for argument about how to order those results – do highly rated third-party parts go above the OEM part? How should the algorithm trade off price and quality?

It's hard to come up with an objective standard to resolve these fine-grained differences, but search technologists have tried. Think of Google: they have a patent on "long clicks." A "long click" is when you search for something and then don't search for it again for quite some time, the implication being that you've found what you were looking for. Google Search ads operate a "pay per click" model, and there's an argument that this aligns Google's ad division's interests with search quality: if the ad division only gets paid when you click a link, they will militate for placing ads that users want to click on.

Platforms are inextricably bound up in this algorithmic information sorting business. Platforms have emerged as the endemic form of internet-based business, which is ironic, because a platform is just an intermediary – a company that connects different groups to each other. The internet's great promise was "disintermediation" – getting rid of intermediaries. We did that, and then we got a whole bunch of new intermediaries.

Usually, those groups can be sorted into two buckets: "business customers" (drivers, merchants, advertisers, publishers, creative workers, etc) and "end users" (riders, shoppers, consumers, audiences, etc). Platforms also sometimes connect end users to each other: think of dating sites, or interest-based forums on Reddit. Either way, a platform's job is to make these connections, and that means platforms are always in the algorithm business.

Whether that's matching a driver and a rider, or an advertiser and a consumer, or a reader and a mix of content from social feeds they're subscribed to and other sources of information on the service, the platform has to make a call as to what you're going to see or do.

These choices are enormously consequential. In the theory of Surveillance Capitalism, these choices take on an almost supernatural quality, where "Big Data" can be used to guess your response to all the different ways of pitching an idea or product to you, in order to select the optimal pitch that bypasses your critical faculties and actually controls your actions, robbing you of "the right to a future tense."

I don't think much of this hypothesis. Every claim to mind control – from Rasputin to MK Ultra to neurolinguistic programming to pick-up artists – has turned out to be bullshit. Besides, you don't need to believe in mind control to explain the ways that algorithms shape our beliefs and actions. When a single company dominates the information landscape – say, when Google controls 90% of your searches – then Google's sorting can deprive you of access to information without you knowing it.

If every "locksmith" listed on Google Maps is a fake referral business, you might conclude that there are no more reputable storefront locksmiths in existence. What's more, this belief is a form of self-fulfilling prophecy: if Google Maps never shows anyone a real locksmith, all the real locksmiths will eventually go bust.

If you never see a social media update from a news source you follow, you might forget that the source exists, or assume they've gone under. If you see a flood of viral videos of smash-and-grab shoplifter gangs and never see a news story about wage theft, you might assume that the former is common and the latter is rare (in reality, shoplifting hasn't risen appreciably, while wage-theft is off the charts).

In the theory of Surveillance Capitalism, the algorithm was invented to make advertisers richer, and then went on to pervert the news (by incentivizing "clickbait") and finally destroyed our politics when its persuasive powers were hijacked by Steve Bannon, Cambridge Analytica, and QAnon grifters to turn millions of vulnerable people into swivel-eyed loons, racists and conspiratorialists.

As I've written, I think this theory gives the ad-tech sector both too much and too little credit, and draws an artificial line between ad-tech and other platform businesses that obscures the connection between all forms of platform decay, from Uber to HBO to Google Search to Twitter to Apple and beyond:

https://pluralistic.net/HowToDestroySurveillanceCapitalism

As a counter to Surveillance Capitalism, I've proposed a theory of platform decay called enshittification, which identifies how the market power of monopoly platforms, combined with the flexibility of digital tools, combined with regulatory capture, allows platforms to abuse both business-customers and end-users, by depriving them of alternatives, then "twiddling" the knobs that determine the rules of the platform without fearing sanction under privacy, labor or consumer protection law, and finally, blocking digital self-help measures like ad-blockers, alternative clients, scrapers, reverse engineering, jailbreaking, and other tech guerrilla warfare tactics:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/01/21/potemkin-ai/#hey-guys

One important distinction between Surveillance Capitalism and enshittification is that enshittification posits that the platform is bad for everyone. Surveillance Capitalism starts from the assumption that surveillance advertising is devastatingly effective (which explains how your racist Facebook uncles got turned into Jan 6 QAnons), and concludes that advertisers must be well-served by the surveillance system.

But advertisers – and other business customers – are very poorly served by platforms. Procter and Gamble reduced its annual surveillance advertising budget from $100m//year to $0/year and saw a 0% reduction in sales. The supposed laser-focused targeting and superhuman message refinement just don't work very well – first, because the tech companies are run by bullshitters whose marketing copy is nonsense, and second because these companies are monopolies who can abuse their customers without losing money.

The point of enshittification is to lock end-users to the platform, then use those locked-in users as bait for business customers, who will also become locked to the platform. Once everyone is holding everyone else hostage, the platform uses the flexibility of digital services to play a variety of algorithmic games to shift value from everyone to the business's shareholders. This flexibility is supercharged by the failure of regulators to enforce privacy, labor and consumer protection standards against the companies, and by these companies' ability to insist that regulators punish end-users, competitors, tinkerers and other third parties to mod, reverse, hack or jailbreak their products and services to block their abuse.

Enshittification needs The Algorithm. When Uber wants to steal from its drivers, it can just do an old-fashioned wage theft, but eventually it will face the music for that kind of scam:

https://apnews.com/article/uber-lyft-new-york-city-wage-theft-9ae3f629cf32d3f2fb6c39b8ffcc6cc6

The best way to steal from drivers is with algorithmic wage discrimination. That's when Uber offers occassional, selective drivers higher rates than it gives to drivers who are fully locked to its platform and take every ride the app offers. The less selective a driver becomes, the lower the premium the app offers goes, but if a driver starts refusing rides, the wage offer climbs again. This isn't the mind-control of Surveillance Capitalism, it's just fraud, shaving fractional pennies off your paycheck in the hopes that you won't notice. The goal is to get drivers to abandon the other side-hustles that allow them to be so choosy about when they drive Uber, and then, once the driver is fully committed, to crank the wage-dial down to the lowest possible setting:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/12/algorithmic-wage-discrimination/#fishers-of-men

This is the same game that Facebook played with publishers on the way to its enshittification: when Facebook began aggressively courting publishers, any short snippet republished from the publisher's website to a Facebook feed was likely to be recommended to large numbers of readers. Facebook offered publishers a vast traffic funnel that drove millions of readers to their sites.

But as publishers became more dependent on that traffic, Facebook's algorithm started downranking short excerpts in favor of medium-length ones, building slowly to fulltext Facebook posts that were fully substitutive for the publisher's own web offerings. Like Uber's wage algorithm, Facebook's recommendation engine played its targets like fish on a line.

When publishers responded to declining reach for short excerpts by stepping back from Facebook, Facebook goosed the traffic for their existing posts, sending fresh floods of readers to the publisher's site. When the publisher returned to Facebook, the algorithm once again set to coaxing the publishers into posting ever-larger fractions of their work to Facebook, until, finally, the publisher was totally locked into Facebook. Facebook then started charging publishers for "boosting" – not just to be included in algorithmic recommendations, but to reach their own subscribers.

Enshittification is modern, high-tech enabled, monopolistic form of rent seeking. Rent-seeking is a subtle and important idea from economics, one that is increasingly relevant to our modern economy. For economists, a "rent" is income you get from owning a "factor of production" – something that someone else needs to make or do something.

Rents are not "profits." Profit is income you get from making or doing something. Rent is income you get from owning something needed to make a profit. People who earn their income from rents are called rentiers. If you make your income from profits, you're a "capitalist."

Capitalists and rentiers are in irreconcilable combat with each other. A capitalist wants access to their factors of production at the lowest possible price, whereas rentiers want those prices to be as high as possible. A phone manufacturer wants to be able to make phones as cheaply as possible, while a patent-troll wants to own a patent that the phone manufacturer needs to license in order to make phones. The manufacturer is a capitalism, the troll is a rentier.

The troll might even decide that the best strategy for maximizing their rents is to exclusively license their patents to a single manufacturer and try to eliminate all other phones from the market. This will allow the chosen manufacturer to charge more and also allow the troll to get higher rents. Every capitalist except the chosen manufacturer loses. So do people who want to buy phones. Eventually, even the chosen manufacturer will lose, because the rentier can demand an ever-greater share of their profits in rent.

Digital technology enables all kinds of rent extraction. The more digitized an industry is, the more rent-seeking it becomes. Think of cars, which harvest your data, block third-party repair and parts, and force you to buy everything from acceleration to seat-heaters as a monthly subscription:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/07/24/rent-to-pwn/#kitt-is-a-demon

The cloud is especially prone to rent-seeking, as Yanis Varoufakis writes in his new book, Technofeudalism, where he explains how "cloudalists" have found ways to lock all kinds of productive enterprise into using cloud-based resources from which ever-increasing rents can be extracted:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/09/28/cloudalists/#cloud-capital

The endless malleability of digitization makes for endless variety in rent-seeking, and cataloging all the different forms of digital rent-extraction is a major project in this Age of Enshittification. "Algorithmic Attention Rents: A theory of digital platform market power," a new UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose paper by Tim O'Reilly, Ilan Strauss and Mariana Mazzucato, pins down one of these forms:

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/publications/2023/nov/algorithmic-attention-rents-theory-digital-platform-market-power

The "attention rents" referenced in the paper's title are bait-and-switch scams in which a platform deliberately enshittifies its recommendations, search results or feeds to show you things that are not the thing you asked to see, expect to see, or want to see. They don't do this out of sadism! The point is to extract rent – from you (wasted time, suboptimal outcomes) and from business customers (extracting rents for "boosting," jumbling good results in among scammy or low-quality results).

The authors cite several examples of these attention rents. Much of the paper is given over to Amazon's so-called "advertising" product, a $31b/year program that charges sellers to have their products placed above the items that Amazon's own search engine predicts you will want to buy:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/11/28/enshittification/#relentless-payola

This is a form of gladiatorial combat that pits sellers against each other, forcing them to surrender an ever-larger share of their profits in rent to Amazon for pride of place. Amazon uses a variety of deceptive labels ("Highly Rated – Sponsored") to get you to click on these products, but most of all, they rely two factors. First, Amazon has a long history of surfacing good results in response to queries, which makes buying whatever's at the top of a list a good bet. Second, there's just so many possible results that it takes a lot of work to sift through the probably-adequate stuff at the top of the listings and get to the actually-good stuff down below.

Amazon spent decades subsidizing its sellers' goods – an illegal practice known as "predatory pricing" that enforcers have increasingly turned a blind eye to since the Reagan administration. This has left it with few competitors:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/05/19/fake-it-till-you-make-it/#millennial-lifestyle-subsidy

The lack of competing retail outlets lets Amazon impose other rent-seeking conditions on its sellers. For example, Amazon has a "most favored nation" requirement that forces companies that raise their prices on Amazon to raise their prices everywhere else, which makes everything you buy more expensive, whether that's a Walmart, Target, a mom-and-pop store, or direct from the manufacturer:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/25/greedflation/#commissar-bezos

But everyone loses in this "two-sided market." Amazon used "junk ads" to juice its ad-revenue: these are ads that are objectively bad matches for your search, like showing you a Seattle Seahawks jersey in response to a search for LA Lakers merch:

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-11-02/amazon-boosted-junk-ads-hid-messages-with-signal-ftc-says

The more of these junk ads Amazon showed, the more revenue it got from sellers – and the more the person selling a Lakers jersey had to pay to show up at the top of your search, and the more they had to charge you to cover those ad expenses, and the more they had to charge for it everywhere else, too.

The authors describe this process as a transformation between "attention rents" (misdirecting your attention) to "pecuniary rents" (making money). That's important: despite decades of rhetoric about the "attention economy," attention isn't money. As I wrote in my enshittification essay:

You can't use attention as a medium of exchange. You can't use it as a store of value. You can't use it as a unit of account. Attention is like cryptocurrency: a worthless token that is only valuable to the extent that you can trick or coerce someone into parting with "fiat" currency in exchange for it. You have to "monetize" it – that is, you have to exchange the fake money for real money.

The authors come up with some clever techniques for quantifying the ways that this scam harms users. For example, they count the number of places that an advertised product rises in search results, relative to where it would show up in an "organic" search. These quantifications are instructive, but they're also a kind of subtweet at the judiciary.

In 2018, SCOTUS's ruling in American Express v Ohio changed antitrust law for two-sided markets by insisting that so long as one side of a two-sided market was better off as the result of anticompetitive actions, there was no antitrust violation:

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3346776

For platforms, that means that it's OK to screw over sellers, advertisers, performers and other business customers, so long as the end-users are better off: "Go ahead, cheat the Uber drivers, so long as you split the booty with Uber riders."

But in the absence of competition, regulation or self-help measures, platforms cheat everyone – that's the point of enshittification. The attention rents that Amazon's payola scheme extract from shoppers translate into higher prices, worse goods, and lower profits for platform sellers. In other words, Amazon's conduct is so sleazy that it even threads the infinitesimal needle that the Supremes created in American Express.

Here's another algorithmic pecuniary rent: Amazon figured out which of its major rivals used an automated price-matching algorithm, and then cataloged which products they had in common with those sellers. Then, under a program called Project Nessie, Amazon jacked up the prices of those products, knowing that as soon as they raised the prices on Amazon, the prices would go up everywhere else, so Amazon wouldn't lose customers to cheaper alternatives. That scam made Amazon at least a billion dollars:

https://gizmodo.com/ftc-alleges-amazon-used-price-gouging-algorithm-1850986303

This is a great example of how enshittification – rent-seeking on digital platforms – is different from analog rent-seeking. The speed and flexibility with which Amazon and its rivals altered their prices requires digitization. Digitization also let Amazon crank the price-gouging dial to zero whenever they worried that regulators were investigating the program.

So what do we do about it? After years of being made to look like fumblers and clowns by Big Tech, regulators and enforcers – and even lawmakers – have decided to get serious.

The neoliberal narrative of government helplessness and incompetence would have you believe that this will go nowhere. Governments aren't as powerful as giant corporations, and regulators aren't as smart as the supergeniuses of Big Tech. They don't stand a chance.

But that's a counsel of despair and a cheap trick. Weaker US governments have taken on stronger oligarchies and won – think of the defeat of JD Rockefeller and the breakup of Standard Oil in 1911. The people who pulled that off weren't wizards. They were just determined public servants, with political will behind them. There is a growing, forceful public will to end the rein of Big Tech, and there are some determined public servants surfing that will.

In this paper, the authors try to give those enforcers ammo to bring to court and to the public. For example, Amazon claims that its algorithm surfaces the products that make the public happy, without the need for competitive pressure to keep it sharp. But as the paper points out, the only successful new rival ecommerce platform – Tiktok – has found an audience for an entirely new category of goods: dupes, "lower-cost products that have the same or better features than higher cost branded products."

The authors also identify "dark patterns" that platforms use to trick users into consuming feeds that have a higher volume of things that the company profits from, and a lower volume of things that users want to see. For example, platforms routinely switch users from a "following" feed – consisting of things posted by people the user asked to hear from – with an algorithmic "For You" feed, filled with the things the company's shareholders wish the users had asked to see.

Calling this a "dark pattern" reveals just how hollow and self-aggrandizing that term is. "Dark pattern" usually means "fraud." If I ask to see posts from people I like, and you show me posts from people who'll pay you for my attention instead, that's not a sophisticated sleight of hand – it's just a scam. It's the social media equivalent of the eBay seller who sends you an iPhone box with a bunch of gravel inside it instead of an iPhone. Tech bros came up with "dark pattern" as a way of flattering themselves by draping themselves in the mantle of dopamine-hacking wizards, rather than unimaginative con-artists who use a computer to rip people off.

These For You algorithmic feeds aren't just a way to increase the load of sponsored posts in a feed – they're also part of the multi-sided ripoff of enshittified platforms. A For You feed allows platforms to trick publishers and performers into thinking that they are "good at the platform," which both convinces to optimize their production for that platform, and also turns them into Judas Goats who conspicuously brag about how great the platform is for people like them, which brings their peers in, too.

In Veena Dubal's essential paper on algorithmic wage discrimination, she describes how Uber drivers whom the algorithm has favored with (temporary) high per-ride rates brag on driver forums about their skill with the app, bringing in other drivers who blame their lower wages on their failure to "use the app right":

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4331080

As I wrote in my enshittification essay:

If you go down to the midway at your county fair, you'll spot some poor sucker walking around all day with a giant teddy bear that they won by throwing three balls in a peach basket.

The peach-basket is a rigged game. The carny can use a hidden switch to force the balls to bounce out of the basket. No one wins a giant teddy bear unless the carny wants them to win it. Why did the carny let the sucker win the giant teddy bear? So that he'd carry it around all day, convincing other suckers to put down five bucks for their chance to win one:

https://boingboing.net/2006/08/27/rigged-carny-game.html

The carny allocated a giant teddy bear to that poor sucker the way that platforms allocate surpluses to key performers – as a convincer in a "Big Store" con, a way to rope in other suckers who'll make content for the platform, anchoring themselves and their audiences to it.

Platform can't run the giant teddy-bear con unless there's a For You feed. Some platforms – like Tiktok – tempt users into a For You feed by making it as useful as possible, then salting it with doses of enshittification:

https://www.forbes.com/sites/emilybaker-white/2023/01/20/tiktoks-secret-heating-button-can-make-anyone-go-viral/

Other platforms use the (ugh) "dark pattern" of simply flipping your preference from a "following" feed to a "For You" feed. Either way, the platform can't let anyone keep the giant teddy-bear. Once you've tempted, say, sports bros into piling into the platform with the promise of millions of free eyeballs, you need to withdraw the algorithm's favor for their content so you can give it to, say, astrologers. Of course, the more locked-in the users are, the more shit you can pile into that feed without worrying about them going elsewhere, and the more giant teddy-bears you can give away to more business users so you can lock them in and start extracting rent.

For regulators, the possibility of a "good" algorithmic feed presents a serious challenge: when a feed is bad, how can a regulator tell if its low quality is due to the platform's incompetence at blocking spammers or guessing what users want, or whether it's because the platform is extracting rents?

The paper includes a suite of recommendations, including one that I really liked:

Regulators, working with cooperative industry players, would define reportable metrics based on those that are actually used by the platforms themselves to manage search, social media, e-commerce, and other algorithmic relevancy and recommendation engines.

In other words: find out how the companies themselves measure their performance. Find out what KPIs executives have to hit in order to earn their annual bonuses and use those to figure out what the company's performance is – ad load, ratio of organic clicks to ad clicks, average click-through on the first organic result, etc.

They also recommend some hard rules, like reserving a portion of the top of the screen for "organic" search results, and requiring exact matches to show up as the top result.

I've proposed something similar, applicable across multiple kinds of digital businesses: an end-to-end principle for online services. The end-to-end principle is as old as the internet, and it decrees that the role of an intermediary should be to deliver data from willing senders to willing receivers as quickly and reliably as possible. When we apply this principle to your ISP, we call it Net Neutrality. For services, E2E would mean that if I subscribed to your feed, the service would have a duty to deliver it to me. If I hoisted your email out of my spam folder, none of your future emails should land there. If I search for your product and there's an exact match, that should be the top result:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/04/platforms-decay-lets-put-users-first

One interesting wrinkle to framing platform degradation as a failure to connect willing senders and receivers is that it places a whole host of conduct within the regulatory remit of the FTC. Section 5 of the FTC Act contains a broad prohibition against "unfair and deceptive" practices:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/01/10/the-courage-to-govern/#whos-in-charge

That means that the FTC doesn't need any further authorization from Congress to enforce an end to end rule: they can simply propose and pass that rule, on the grounds that telling someone that you'll show them the feeds that they ask for and then not doing so is "unfair and deceptive."

Some of the other proposals in the paper also fit neatly into Section 5 powers, like a "sticky" feed preference. If I tell a service to show me a feed of the people I follow and they switch it to a For You feed, that's plainly unfair and deceptive.

All of this raises the question of what a post-Big-Tech feed would look like. In "How To Break Up Amazon" for The Sling, Peter Carstensen and Darren Bush sketch out some visions for this:

https://www.thesling.org/how-to-break-up-amazon/

They imagine a "condo" model for Amazon, where the sellers collectively own the Amazon storefront, a model similar to capacity rights on natural gas pipelines, or to patent pools. They see two different ways that search-result order could be determined in such a system:

"specific premium placement could go to those vendors that value the placement the most [with revenue] shared among the owners of the condo"

or

"leave it to owners themselves to create joint ventures to promote products"

Note that both of these proposals are compatible with an end-to-end rule and the other regulatory proposals in the paper. Indeed, all these policies are easier to enforce against weaker companies that can't afford to maintain the pretense that they are headquartered in some distant regulatory haven, or pay massive salaries to ex-regulators to work the refs on their behalf:

https://www.thesling.org/in-public-discourse-and-congress-revolvers-defend-amazons-monopoly/

The re-emergence of intermediaries on the internet after its initial rush of disintermediation tells us something important about how we relate to one another. Some authors might be up for directly selling books to their audiences, and some drivers might be up for creating their own taxi service, and some merchants might want to run their own storefronts, but there's plenty of people with something they want to offer us who don't have the will or skill to do it all. Not everyone wants to be a sysadmin, a security auditor, a payment processor, a software engineer, a CFO, a tax-preparer and everything else that goes into running a business. Some people just want to sell you a book. Or find a date. Or teach an online class.

Intermediation isn't intrinsically wicked. Intermediaries fall into pits of enshitffication and other forms of rent-seeking when they aren't disciplined by competitors, by regulators, or by their own users' ability to block their bad conduct (with ad-blockers, say, or other self-help measures). We need intermediaries, and intermediaries don't have to turn into rent-seeking feudal warlords. That only happens if we let it happen.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/11/03/subprime-attention-rent-crisis/#euthanize-rentiers

Image:

Cryteria (modified)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HAL9000.svg

CC BY 3.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#rentiers#euthanize rentiers#subprime attention crisis#Mariana Mazzucato#tim oreilly#Ilan Strauss#scholarship#economics#two-sided markets#platform decay#algorithmic feeds#the algorithm tm#enshittification#monopoly#antitrust#section 5#ftc act#ftc#amazon. google#big tech#attention economy#attention rents#pecuniary rents#consumer welfare#end-to-end principle#remedyfest#giant teddy bears#project nessie#end-to-end

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

.sucks domain

ICANN has received more than $60 million from gTLD auctions, and has accepted the controversial domain name ".sucks" (referring to the primarily US slang for being inferior or objectionable). .sucks domains are owned and controlled by the Vox Populi Registry which won the rights for .sucks gTLD in November 2014.

The .sucks domain registrar has been described as "predatory, exploitive and coercive" by the Intellectual Property Constituency that advises the ICANN board. When the .sucks registry announced their pricing model, "most brand owners were upset and felt like they were being penalized by having to pay more to protect their brands." Because of the low utility of the ".sucks" domain, most fees come from "Brand Protection" customers registering their trademarks to prevent domains being registered.

Canadian brands had complained that they were being charged "exorbitant" prices to register their trademarks as premium names. FTC chair Edith Ramirez has written to ICANN to say the agency will take action against the .sucks owner if "we have reason to believe an entity has engaged in deceptive or unfair practices in violation of Section 5 of the FTC Act". The Register reported that intellectual property lawyers are infuriated that "the dot-sucks registry was charging trademark holders $2,500 for .sucks domains and everyone else $10."

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

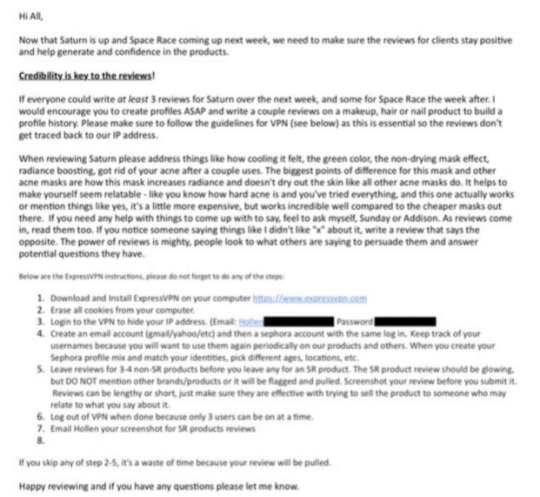

Sunday Riley: Wrote Fake Sephora Reviews for Almost Two Years - says FTC

By Celine Soto

SUMMARY: Sunday Riley is a Texas-based, high performance skincare brand, powered by science and balanced by nature that launched in 2009. Its products are sold at Ulta Beauty and Sephora. They are praised for their use of green technology, meaning that its commitment to produce a clean formula and recipe for its products such as using flower and plant extract oils, rather than artificial fragrances, all while producing products in small batches makes it stand out from its competitors (Sunday Riley, 2019).

In October 2018, about one year ago, a Reddit user who claimed to be a former employee at Sunday Riley disclosed emails that showed employees were requested by the Sunday Riley company to create Sephora accounts and write fake reviews leaving positive comments about the company’s products. The email was as extensive as giving instructions to the employees on how to install a Viral Private Network (VPN), which makes reviews untraceable to the company’s IP address.

The leak was initially posted on Instagram and Sunday Riley fired back in defense of its scheme. The comment wrote, "The simple and official answer to this Reddit post is that yes, this email was sent by a former employee to several members of our company, at one point, we did encourage people to post positive reviews at the launch of this product, consistent with their experiences” (Elassar, p. 18, 2019). Also stating that the company believes competitors would “often post negative reviews” in order to defeat the brand.

Eventually, this triggered an investigation by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to file a complaint against the company. This was an ongoing process, but as of Monday, October 21 2019, the skin care brand finally settled with the FTC. The consent agreement form in the settlement read that “this matter settles alleged violations of federal law prohibiting unfair or deceptive acts or practices” (FTC, p. 1, 2019). According to the FTC, “The complaint alleges that the respondents violated Section 5(a) of the FTC Act by misrepresenting that certain reviews of Sunday Riley brand products on the Sephora website reflected the independent experiences or opinions of impartial ordinary users of the products, when they were written by Ms. Riley and her employees” (FTC, p. 15, 2019).

After almost two years (2015-2017) of violating Section 5(a) of the FTC Act by creating fake reviews on its retailer’s websites in order to boost sales, Sunday Riley agreed to not post any more fake reviews. “False Advertising and Fake Review Fraud distort the markets by harming honest companies” said FTC commissioners Rohit Chopra and Rebecca Kelly Slaughter. The verdict of this settlement was that the FTC ordered that Sunday Riley will not and can not break the law again.

REACTION & PAGE PRINCIPLES:

Even after the FTC found the alleged accusation of Sunday Riley’s scheme to be true by the ex-employee that leaked the emails, the Sunday Riley cosmetic/skincare brand is still not admitting to any wrongdoings. An article in The New York Times wrote, “The settlement does not provide consumers with refunds, and it does not force Sunday Riley to admit any wrongdoing: The company simply agreed to not break the law in the future” (Garcia, p. 3. 2019). The company was only charged with making false or misleading claims of the products and deceived the public by not disclosing that the reviews were written by the CEO and her employees. I am sure that this has happened before with other companies, but not to this extent. Not to the extent of registering Sephora accounts under different identities and lying to potential customers who take product reviews into account when making purchase decisions. In 2016, a study showed that a one-star rating increase on Yelp could mean a 5 to 9 percent increase in revenue; therefore, statistics prove that online reviews affect customers. (Garcia, p. 11, 2019).

Tell the Truth: According to Arthur W. Page, tell the truth means to let the public know what’s happening with honest and good intention; provide an ethically accurate picture of the enterprise’s character, values, ideals and actions. Telling the truth is a principle that did not align with Sunday Riley’s settlement. Posting deceptive and inaccurate comments to a well-known website such as Sephora, can not only skew consumers choices, but also there will be a lack in confidence that the reviews are truthful. Not only were the customer reviews biased and fake, but Sunday Riley did not have to disclose that the reviews were written by employees and the CEO herself. After reviewing this incident, myself, I noticed that Sunday Riley did not make any announcements via social media. Its Instagram and Twitter were completely free of any PSAs from the CEO or a higher-up. Its content showed regular promotion of its products and links to its “Sunday Riley Edit” blog attached to its website. The only space that they spoke out on was the Instagram account “Esteé Laundry” which is an anonymous beauty collective blog. I have attached the announce in the comments by Sunday Riley back in October of 2018, but has since had no further comment. The FTC did tweet about this incident, along with many upset customers of Sephora.

Realize an Enterprise’s True Character is Expressed by its People: Every employee – active or retired – is involved with public relations. It is the responsibility of corporate communications to advocate for respect in the workforce and to support each employee’s capability and desire to be an honest and knowledgeable ambassador to customers. I believe that this principle is the exact opposite of how Sunday Riley handled the law-breaking incident. First, the CEO, higher-ups and employees that abided by the rules that were given to them all showed their true character. The people involved knew that they were breaking the law and were not being honest ambassadors to Sunday Riley customers.

Prove It with Action: When this was exploited by former customer “whistleblower” a year ago in October 2018, Sunday Riley did not admit to any wrongdoing, instead stated that was an email sent by a former employee. A year later after its settlement with the FTC, although it is fresh, Sunday Riley has yet to come clean about the incident publicly. Personally, I will give the company the benefit of the doubt that this all just happened on Monday, October 21 and it is only two days passed the release of the settlement. The company still has a chance to prove it with action by maybe just releasing a personal statement apologizing to its customers.

SOURCES:

Chopra, R. Slaughter, R. (2019, October 21). “Statement of Commisioner Rohit Chopra Joined by Commissioner Rebecca Kelly Slaughter.” Federal Trade Commission. Retrieved from https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_statements/1550127/192_3008_final_rc_statement_on_sunday_riley.pdf

Elassar, A. (2019, October 23). “Skin care brand Sunday Riley wrote fake Sephora reviews for almost two years, FTC says.” CNN. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2019/10/22/us/sunday-riley-fake-reviews-trnd/index.html

Federal Trade Commission. (n.d.). Sunday Riley Modern Skincare, LLC; Analysis to Aid Public Comment. Retrieved from https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/federal_register_notices/2019/10/192_3008_sunday_riley_skincare_-_analysis_frn.pdf

Garcia, S. (2019, October 22). “Sunday Riley Settles Complaint That It Faked Product Reviews.” The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/22/us/sunday-riley-fake-reviews.html

The Page Principles. (n.d.). Arthur W. Page Society. Retrieved from https://page.org/site/the-page-principles

1 note

·

View note

Text

Facebook’s reason for banning researchers doesn’t hold up

Facebook’s reason for banning researchers doesn’t hold up

https://theministerofcapitalism.com/blog/facebooks-reason-for-banning-researchers-doesnt-hold-up/

When Facebook said On Tuesday, suspending the accounts of a team of researchers at New York University made it appear that the company’s hands were tied. The team had crowdsourced data on political ad targeting using a browser extension Facebook he had warned them repeatedly that it was not allowed.

“For months, we’ve been trying to work with New York University to provide three of its researchers with the accurate access they’ve asked for in a privacy-protected way,” wrote Mike Clark, Facebook’s director of product management. in a blog post. “We took these actions to stop unauthorized scratching and protect the privacy of people in accordance with our privacy program. [Federal Trade Commission] Order “.

Clark was referring to the consent decree imposed by FTC in 2019, along with a $ 5 billion fine for privacy violations. You can understand the situation of the company. If researchers want one thing, but a powerful federal regulator requires something else, the regulator will win.

Except that Facebook was not in this difficult situation, because the consent decree does not prohibit what the researchers have been doing. Perhaps the company didn’t act to stay in the good graces of the government, but because it doesn’t want the public to learn one of the best-kept secrets: who the ads are shown to and why.

The FTC’s punishment arose from the Cambridge Analytica scandal. In this case, the nominally academic researchers had access to Facebook user data and data about their friends directly from Facebook. These data ended up in the infamous hands of Cambridge Analytica, which used them to microcenter on behalf of Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign.

The NYU project, the Ad Observer, works very differently. He has no direct access to Facebook data. Rather, it is a browser extension. When a user downloads the extension, they agree to submit the ads they see, including the information in “Why do I see this ad?” widget, to researchers. The researchers then deduce which policy ads are targeted to which user groups, data that Facebook does not disseminate.

Does this agreement violate the consent decree? Two sections of the order can be applied. Section 2 requires Facebook to obtain a user’s consent before sharing their data with another person. Since the ad viewer relies on users agreeing to share data, not on Facebook, this is not relevant.

When Facebook shares data with outsiders, “it has certain obligations to the police in this relationship to share data,” says Jonathan Mayer, a professor of computer science and public affairs at Princeton. “But there’s nothing in order about whether a user wants to go out and tell a third party what they’ve seen on Facebook.”

Joe Osborne, a Facebook spokesman, acknowledges that the consent decree did not force Facebook to suspend the investigators ’accounts. Rather, according to him, section 7 of the decree requires Facebook to implement a “comprehensive privacy program” that “protects the privacy, confidentiality and integrity” of users ’data. Facebook’s privacy program, not the consent decree itself, prohibits what the ad watch team has been doing. Specifically, Osborne says, investigators repeatedly violated a section of Facebook terms of service which provides: “You may not access or collect data from our products by automated means (without our prior permission).” In the blog post announcing the account bans the scratch is mentioned 10 times.

Laura Edelson, PhD candidate at New York University and co-creator of the ad observer, rejects the suggestion that the tool be automated scraper Absolutely not.

“Scratching is when I write a program to automatically scroll through a website and make the computer drive the browser work and what is downloaded,” he says. “This is not how our extension works. Our extension is included with the user, and we only collect data from ads that are shown to the user. “

Facebook’s claims about privacy issues “simply don’t contain water.”

Marshall Erwin, head of security at Mozilla

Bennett Cyphers, a technologist at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, agrees. “There really isn’t a good consistent definition of scratching,” he says, but the term is very rare when users choose to document and share their personal experiences on a platform. “It looks like this is not capable of making Facebook control. Unless they are saying it is against the terms of service for the user to take notes on their interactions with Facebook in some way.”

Ultimately, if the extension is really “automated” it’s a bit useless, because Facebook could always change its own policy or, depending on the existing policy, it could just give researchers permission. So the most important question is whether the ad viewer is actually violating anyone’s privacy. Osborne, the Facebook spokesman, says that when the extension passes over an ad, it could be exposing information about other users who did not consent to share their data. If I have the extension installed, for example, I could share the identity of my friends who liked or commented on an ad.

Source link

0 notes

Text

Worker misclassification is a competition issue

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/02/02/upward-redistribution/#bedoya