#firas abou fakher

Text

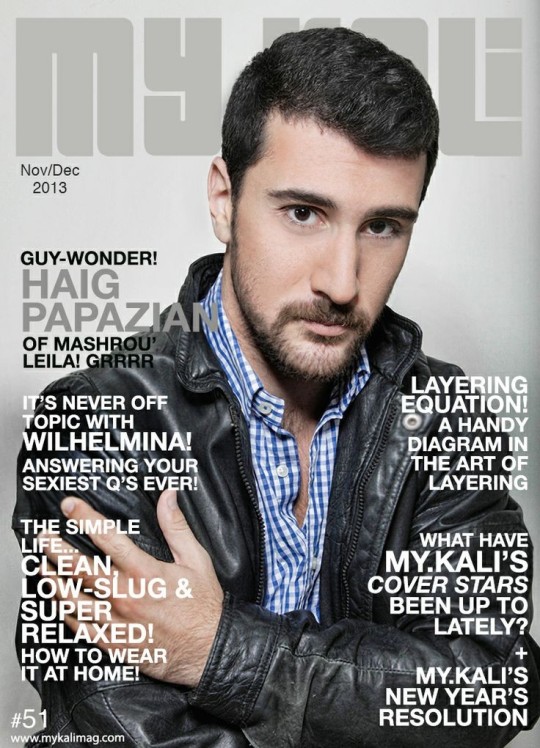

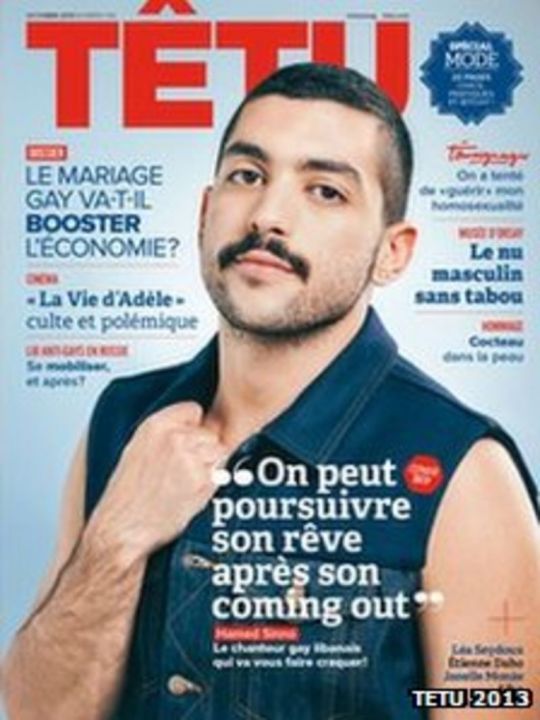

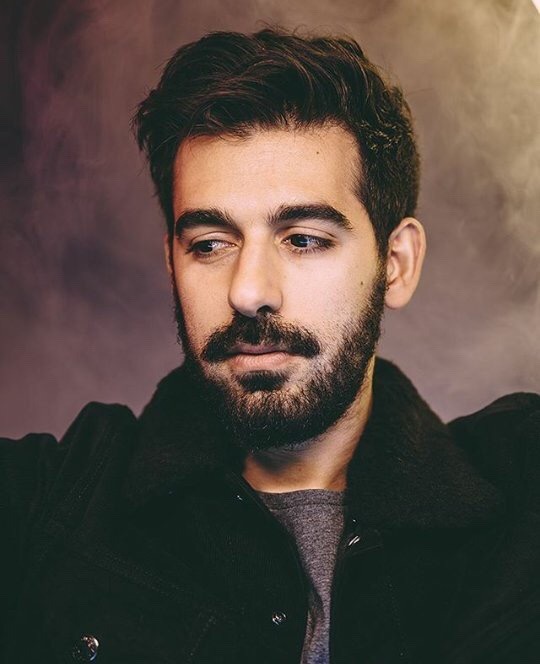

#went down a Pinterest rabbit hole but here's mashrou'leila and hames sinno on magazine covers#hamed sinno#mashrou' leila#haig papazian#carl gerges#firas abou fakher#ibrahim badr#magazine covers

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

17 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Cavalry by Mashrou' Leila from the album The Beirut School [English Version] - Directed by Jessy Moussallem

#music#mashrou' leila#mashrou leila#hamed sinno#firas abou fakher#haig papazian#carl gerges#joe goddard#video#ibrahim badr#music video#jessy moussallem#sofian el fani#tianès montasser#rawad hobeika#carlo kassabian#ola achkar#wissam smayra#marlene jaber#hady dahrouj#مشروع ليلى#حامد سنّو#هايغ بابازيان#فراس أبو فخر

47 notes

·

View notes

Video

this is arguably the best concert video I've ever taken

#mashrou' leila#mashrou leila#haig papazian#hamed sinno#lebanon#lebanese#washington dc#U Street#lmao#carl gerges#firas abou fakher#beirut#concert#arab#armenian#music#arab music

70 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Romans" by Mashrou Leila Equality. Solidarity. Intersectionality. #charge "The video self-consciously toys with the intersection of gender with race by celebrating and championing a coalition of Arab and Muslim women, styled to over-articulate their ethnic background, in a manner more typically employed by Western media to victimise them. This seeks to disturb the dominant global narrative of hyper-secularised (white) feminism, which increasingly positions itself as incompatible with Islam and the Arab world, celebrating the various modalities of middle-eastern feminism. The video purposefully attempts to revert the position of the (male) musicians as the heroes of the narrative, not only by subjecting them to the (female) gaze of the director, but also by representing them as individuals who (literally) take the backseat as the coalition moves forward. So while the lyrics of the verses discuss betrayal, struggle, and conflict, the video revolves around the lyrical pivot in the chorus: ‘aleihum (charge!) treating oppression, not as a source of victimhood, but as the fertile ground from which resistance can be weaponised."

#mashrou leila#romans#music video#gifset#arabic music#gifs#middle east#hamed sinno#haig papazian#carl gerges#firas abou fakher

240 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mashrou’ Leila Concert

By Annika Schafer

On one of the first crisp fall mornings of my time at Wellesley, I escaped from the chill into my 8:30 introductory Arabic class. My professor handed me a sheet bursting with Arabic text—what looks like a poem. But it’s not a poem, it turns out to be a song.

The music video opens on a man in a car wearing a black graphic tee with an outline of a tuxedo on it. The vocals begin immediately, a rousing, lilting rhythm punctuated by a clear, charged quality to lead singer, Hamed Sinno’s voice. As the camera view zooms out, Mashrou’ Leila’s distinctive violinist, Haig Papazian begins to play and we see that the car isn’t actually moving at all but is on the bed of a tow truck. The drums kick in, and the truck drives away, the car riding off screen along with it.

There are almost boundless layers of symbolism to the video—the façade of masculinity on the ‘tuxedo’ tee, the semblance of control when he’s driving the car, and so many other things past the first shot in the video.

And when I saw it in that Arabic class, that was the extent of the nuance and meaning that I could access. However, their sound and their socially revolutionary message transcends language barriers and drew me to them. In just the few months from October to the end of the calendar year, Mashrou’ Leila had become my #1 played artist on Spotify.

I was a fast fan, and as I picked up more Arabic, I was able to appreciate bits and pieces of the content of the songs’ lyrics more and more; I watched their Tiny Desk performance (link), watched and read interviews, and gained some context.

The band was born in 2008 in Beirut, Lebanon, formed by five young Beiruti college students dissatisfied by the status quo and uninterested in indulging societal expectations. Mashrou’ Leila is a name of dual meanings; one possible translation--Project of the Night--reflects the time at which music is often created and enjoyed. Another possible translation--Leila’s Project--plays on the very popular Arabic name, Leila. Their lyrics speak to everything from police brutality, corrupt politics, and gay night club shootings to the innate gendering of the Arabic language, gender constructions, and sexual freedom to getting really drunk at a club. The band orients themselves towards speaking truth to power, and this—as well as lead singer Sinno being openly gay—has made them the target of attacks, condemnation, bans, and threats. Their concerts often leave protests in their wake, and after a concert of theirs in Jordan was cancelled by the Jordanian government, they were informed that they were not going to be allowed to play in the country again due to their “political and religious beliefs and endorsement of gender equality and sexual freedom” (link). In 2010, several audience members attending Mashrou’ Leila’s concert in Cairo, Egypt were arrested for flying rainbow flags (link). The band has been unflinching in the face of such attacks, stating in the wake of being banned in Jordan that:

We denounce the systemic prosecution of voices of political dissent.

We denounce the systemic prosecution of advocates of sexual and religious freedom.

We denounce the censorship of artists anywhere in the world. (link)

Mashrou’ Leila is the voice of a generation’s revolution—a catalyst of change. Their September 30 concert in Boston was exactly as poignant, rousing, and stunning as you would envisage.

The music of Mashrou’ Leila departs from classical Arab motifs in many ways--I can’t identify any maqams or microtones--but Sinno’s vocalic style assumes the precision and style and artistry of some of the foundational Arab lyricists and vocalists that came before him.

The strength in his voice, the way he extends the pronunciation of certain words, and the way he deftly undulates his pitch are unparalleled in Western music.

I’ve listened to the recorded versions so many times that the sum of musical choices that make up the songs no longer feel ephemeral and human and subjective, but infinite and immutable. However, hearing the songs live, five feet from the humans creating them, gave me the space from the versions I know so well to enjoy the fundamental humanity in this music.

The filler music in the venue dies down, and Hamed Sinno’s charged, powerful voice fills up the room. The lights go red, and violinist Haig Papazian widens his stance and raises his bow—ready to accentuate the melody as the drums drop in. The crowd is in it. We are in it. It is an Arab space. A queer space. Filled with love, filled with light, and filling everyone in that space with light and love as well. They open with a song that they haven’t released yet. Without an introduction, and without a translation, I don’t have a real sense of what the content of the song is, but you don’t have to know a word of Arabic to fall into Sinno’s enigmatically textured vocals, Firas Abou Fakher’s richly-layered instrumentals, the imploring sound of Papazaian’s violin, and the meditative beat of Carl Gerges’ drums.

Sinno introduces each song in between pouring himself more hot tea from the kettle that is set up on stage in front of the microphone.

The first song of the set that was off of a released album was Roman, and everything slowed down. Nothing but a light synth backed up Sinno’s strong and emphatic vocals as they filled up the room. Sinno took his time here, enunciating every syllable, lingering on each note, using the space that this stripped-down version affords him to play with the notes, riffing and drawing them out. Sinno’s voice carries the song as the drums build, and right when the build peaks, Haig’s violin drives the chorus. The next song they played was Kalaam (S/he) off of their 2017 album Ibn El Leil (trans. Child of the Night), which comments on the way that the Arabic language necessarily genders all nouns. Some of the lyrics go: “They wrote the country's borders upon my body, upon your body / In flesh-ligatured word / My word upon your word, as my body upon your body / Flesh-conjugated words.” The treatment of this song was authentic and anthemic, opening space for all to participate.

They continued playing songs off of Ibn El Leil and their 2019 album The Beirut School: Asnam (Idols), Radio Romance, Aeode, and Bint Elkhandaq. Then, they played Djin. This was my first favorite song of theirs. It is a veritable bop. Inspired by Joseph Campbell’s work on analyzing archetypes across mythologies, the song takes from the Arabic mythical Djinn as well as elements of Christian mythology, but it’s also “just about getting really messed up at a bar” (link), playing off of the alcoholic “gin”. This is the song that the entire audience knows the words to. We all sing together. Sinno tells us at the beginning to sing the refrain when the lyrics show up on the screen; “if you can’t read Arabic, learn Arabic. Or just look around, find an Arab, and copy them.” Most people already know the song though. We yell out the lyrics and Sinno draws energy from the crowd, breaking from our pace to play with the melody with flair and mastery.

After one last song, Cavalry, they exit the stage. We cheer and a chant breaks out that I can’t identify. For the encore, Sinno sits down on elevated part of the stage. We hear the opening bars of Fasateen, and the crowd is silenced. It is fitting for me, I think, that this concert ends with the first Mashrou’ Leila song that I ever heard.

I have since listened to the album enough that I know all the lyrics even if I don’t understand them all, and we are all singing along with Sinno as we dance.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mashrou' Leila: the Lebanese indie band championing Arab gay rights | Music | The Guardian

Mashrou’ Leila are giants in Lebanon. Walking through Beirut with the band on a warm afternoon, it feels like everyone is staring. We squeeze into a retro diner in the city’s bustling Hamra neighbourhood, and have hardly started talking before two women interrupt for a selfie.

As they celebrate their 10th anniversary, the four-piece are already the Arab world’s biggest indie group. They’re also probably the most successful Arabic-language band internationally, with a European tour lined up and a new compilation featuring collaborations with Róisín Murphy and Hot Chip’s Joe Goddard.

They met in 2008 at the nearby American University of Beirut, a leafy hillside campus tumbling down towards the glittering Mediterranean. They first came to this spot – where today they’re picking over greasy burgers and congealed coleslaw – to drink and calm their nerves before early gigs.

Facebook Twitter Pinterest

“We didn’t have expectations,” says drummer Carl Gerges in French-accented English. “The band wasn’t meant to last forever.” This was reflected in their name, which means “overnight project”. Yet their early songs, such as Shim El Yasmine (Smell the Jasmine), a tender ballad about abandoning a gay lover for a prescribed marriage, and the Balkan jazz-style hoedown of Raksit Leila, shot them to unexpected stardom.

It can’t be absurd to the western imagination that many liberal Arabs are inclined towards gender and sexual diversity

Their surprise was partly down to the fact that few independent Lebanese musicians had made it big before. There was no national infrastructure to support them. Everything in Mashrou’ Leila’s early years was improvised: they won the opportunity to record their debut album in a radio competition and promoted concerts by spraying graffiti in the alleyways of Beirut. When they were invited to be the first Lebanese band to headline the local Byblos festival, they had to hastily write six new songs to fill their set.

Mashrou' Leila: the Lebanese band changing the tune of Arab politics

Read more

Their appeal is particularly obvious live. Lead singer Hamed Sinno is a flamboyant performer with an electric stage presence, his formidable voice as comfortable soaring as it is flirting with Haig Papazian’s keening violin. As their sound matured into superbly sleek electropop on 2015’s Ibn El Leil, their international profile steadily grew. Yet because of their outspoken support for LGBTQ rights (Sinno is a rare out gay figure in Arab media) they have received more press for their politics than their music.

Sinno finds himself saddled with being a voice for Arabs, Muslims and the Middle Eastern LGBTQ community. What bothers him most is when western media treat the band’s progressive politics as exceptional. “It can’t be that absurd to the western imagination that there are many liberal Arabs inclined towards gender and sexual diversity,” he says hotly. “To write them off because of the oppression of free speech in their countries does everyone an extreme injustice.”

Facebook Twitter Pinterest

The band’s politics saw them banned – twice – from playing in Jordan. “They said the band is immoral, that we incite a revolutionary feeling in people,” says instrumentalist and composer Firas Abou Fakher. At their biggest concert ever, to 35,000 people in Cairo, the appearance of two rainbow flags in the crowd scandalised the Egyptian press. Rumours spread that the gig had actually been a giant orgy and that the band were in prison. The Egyptian government arrested 75 people that they suspected of being gay in the ensuing crackdown.

Sign up for the Sleeve Notes email: music news, bold reviews and unexpected extras

Read more

The band watched this happen from abroad, powerless. “Our inboxes were constantly littered with death threats and the most hateful remarks possible,” says Sinno, his eyes widening. He becomes uncharacteristically quiet. “It was fucking traumatising.” They also incurred the financial loss of being blocked from performing for their two biggest fanbases. Now looking to a western audience, they have started writing lyrics in English, but Sinno rejects the idea that this makes him less authentic. “There’s something to be said for a band from the Arab world to make it, regardless of language,” he says.

Still, the band won’t abandon their Arabic hits. At gigs abroad they see fans who don’t speak Arabic attempt to sing along with eyes closed and no idea what they’re saying. “In the current political climate, the fact that people could relate Arabic not to Islamic fundamentalism and terror, but to learning phonetics and going to a concert, it’s a kind of political victory,” says Sinno, smiling. “And it’s moving.”

This content was originally published here.

0 notes

Video

youtube

When we invited the band Mashrou' Leila to come play at the Tiny Desk, we couldn't have foreseen the timing.

The group arrived at our office the morning after the horrific June 12 shootings in Orlando at the gay nightclub Pulse. We were all collectively reeling from the news, and for this rock band from Beirut, Lebanon, the attack hung very heavily.

Mashrou' Leila is fronted by singer and lyricist Hamed Sinno, along with violinist Haig Papazian, keyboardist and guitarist Firas Abou Fakher, Ibrahim Badr on bass and drummer Carl Gerges: five young Beirutis whose family backgrounds reflect Lebanon's religious diversity.

Sinno is openly gay, and Mashrou' Leila is well acquainted with the targeting of LGBT people. The band has faced condemnation, bans and threats in its home region, including some from both Christian and Muslim sources, for what it calls "our political and religious beliefs and endorsement of gender equality and sexual freedom." And yet, when Mashrou' Leila performs in the U.S., its members are often tasked with representing the Middle East as a whole, being still one of the few Arab rock bands to book a North American tour.

After the attack on Pulse, the members of Mashrou' Leila decided to open their Tiny Desk set with "Maghawir" (Commandos), a song Sinno wrote in response to two nightclub shootings in Beirut — a tragic parallel to what happened in Orlando. In the Beirut incidents, which took place within a week of each other, two of the young victims were out celebrating their respective birthdays. "Maghawir" is a checklist of sorts about how to spend a birthday clubbing in the band's home city, but also a running commentary about machismo and the idea that big guns make big men.

"All the boys become men / Soldiers in the capital of the night," Sinno sings. "Shoop, shoop, shot you down ... We were just all together, painting the town / Where'd you disappear?" It was a terrible, and terribly fitting, response to the Florida shootings.

In all of its songs, Mashrou' Leila creates densely knotted wordplay; even the band's name has layers of meaning and resonance. The most common translation of "Mashrou' Leila" is "The Night Project," which tips to the group's beginnings back in 2008 in sessions at the American University of Beirut. But Leila is also the name of the protagonist in one of Arabic literature's most famous tales, the tragic love story of Leila and Majnun, a couple somewhat akin to Romeo and Juliet. Considering Mashrou' Leila's hyper-literary bent, it's hard not to hear that evocation.

In the second song, "Kalaam" (S/He), Sinno dives deep into the relationships between language and gender, and how language shapes perception and identity: "They wrote the country's borders upon my body, upon your body / In flesh-ligatured word / My word upon your word, as my body upon your body / Flesh-conjugated words." (The band has posted its own full English translations of these songs online.)

The title of the third song in Mashrou' Leila's set, "Djin," is a perfect distillation of that linguistic playfulness. In pre-Islamic Arabia and later in Islamic theology and texts, a djin (or jinn) is a supernatural creature; but here, Sinno also means gin, as in the alcoholic drink. "Liver baptized in gin," Sinno sings, "I dance to ward off the djin."

But you don't have to speak a word of Arabic, or get Mashrou' Leila's cerebral references, to appreciate its songs: deeply layered, darkly textured and sonically innovative. And sometimes, as Sinno says, the band's songs "are just about getting really messed up at a bar."

Ibn El Leil (Son Of The Night) is available now:

iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/ibn...

Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B01...

Set List:

"Maghawir" (Commandos)

"Kalaam" (S/He)

"Djin"

Credits:

Producers: Anastasia Tsioulcas, Niki Walker; Audio Engineer: Josh Rogosin; Videographers: Niki Walker, Claire Hannah Collins, Kara Frame; Production Assistant: Sophie Kemp; Photo: Ruby Wallau/NPR.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pictures by Charlelie Marange ©

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes