#during which time he most fully embodied the aspect of rage. like.

Text

I have a draft saved somewhere talking about my classpect headcanons for everyone, I really need to finish that sometime so people can see where I'm coming from when I say "fidds is a mage of rage". I have Ford down as a prince of light, stan as a thief of time, and bill as a lord of hope, but I think those are a liiittle bit more self explanatory

#classpecting#<-a homestuck personality/narrative role classification system for those who dont know#godsrambles#rage is the aspect of doubt. meaninglessness. of tearing things down when they arent working.#do you see my thinking here. fidds as thr opposing force to bill. doubting the project. trying to stop it.#inventing a device that literally takes away memories. things that give context and meaning to ones life#and then being stuck with narrative meaninglessness for decades#during which time he most fully embodied the aspect of rage. like.#even the clown/jester themes of rage sort of apply during most of the show. bc of his role as a joke character for so long#idk how to sum it all up in a post. but yeah#and then with bill. hope is about endless possibilities. imagination. feeling like you can do Anything with no restrictions#which fits really well with his whole deal. like inspiring ford. 'lie until youre not lying anymore.' wanting there to be no rules.#never growing up in all his milennia of existence. playing pretend to trick people. literally existing inside dreams. being whimsical#and the 'lord' class is the most powerful destructive one of all.#so yknow. wielding the hope aspect and everything it represents. as a destructive force. it fits him so well#when i write a full post i'll go over my thoughts on all the classpects. i just know itll take longer than i'd like#to write it all out and then make it concise enough to be readable

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fierce Mergence

An idea that came to me involving the Fierce Deity mask. We all know that there is some kind of entity inside the powerful item which during Majora's Mask and Hyrule Warriors cause the wearer to take its form. However in Breath of the Wild, it was just a mild powerup. (Reminder that it's a Amiibo based item and not actually canon.)

I can only suspect that after sometime between Hyrule Warriors and Breath of the Wild, the Fierce Deity entered a catatonic state or hibernation. Here's some important info to know about complete sensory deprivation. It can be used as a form of therapy but only for short amount of time. Too much will cause serious psychological effects on someone such as dementia (which can explain any possible memory loss).

You see the brain breaks down rational thought structures to minimize stress which however results in a psychotic breakdown afterwards. Imagine being trapped for so long without those vital senses? God or not, that is true hell to even the Fierce Deity.

Hence the catatonic state, his power locking his conscience away cause I'm pretty sure no one wants to see what happens when a god has a psychotic breakdown. That's my theory for why the mask doesn't act the same.

Now for to the actual topic here. What if the Fierce Deity fully fused with the current wearer? I don't mean like possessive type fusion but a purer version. Where two people fully become one: mind, body and soul. The entity wanting to escape their hellish imprisonment at any cost.

Two characters that come to mind is Breath of the Wild Link (Wild in Linked Universe terms) and Majora's Mask Link (Mask/Time in Linked Universe terms). Now if you guys are fans of the Fierce Dadity trope... here's a way to make it sad.

Fierce (or Valion as I prefer to call him) performing such a fusion to save his current wielder especially if that Link is a son in the god's eyes. Most of Link's being is front and center but everything that is Valion becomes consumed. Godhood's already a tough pill to swallow but when it costs your father...

Yeah, neither Mask/Time or Wild are gonna be okay for awhile especially the latter when you look at BOTW. If you don't want to go for the Fierce Dadity route like this but still want to use such an idea then here's a fun twist.

Mask/Time becoming the Fierce Deity thanks to over usage of the mask. It becomes harder and harder to take it off. Whenever it is removed, there are lasting changes such as increase in height, hair beginning to whiten and eyes losing their natural features.

For Wild, this comes from the constant upgrades given by the Great Fairies. The Fierce Deity Mask subtle gaining enough power alongside Valion gaining just a bit of conscious to perform a fusion. An unexpected change as Wild just wanted to wear his new outfit more, not become a God of Battle.

The Fierce Deity does want a chance to live again even if he's just an echo or hidden conscious. Reason why he does this to these Links is because of who they are as a person. Neither of them would use such power for personal gain but to genuinely help others.

Some folks in the fandom see Fierce Deity as a war god so there are important aspects that must be known. War isn't always started just for the hell of it. It is often for the sake of others whether the intentions are good or bad. War has its own heroes: soldiers, medics, to even the citizens themselves.

Hope, pain, sorrow, faith, joy, grief and rage are also emotions connected to this very concept. Both Links embody nearly all of this so they are perfect candidates in Valion's eyes. The Deity's seat is now empty so someone should take his place. And if that successor takes on a child, it just makes things better cause they now have a reason to avoid the same fate.

That's all I have for now. Until next time folks, I'll see you back in Hyrule.

Edit: I forgot to add that you guys can try your hand at this concept! I don't really mind at all as I'm curious about what people can come up with. 😀

#tales of sonicasura#sonicasura#fierce deity#fierce deity link#fierce deity mask#fierce dadity#loz#loz mm#loz botw#loz link#legend of zelda#legend of zelda link#legend of zelda majora's mask#legend of zelda breath of the wild#idea#linked universe related#linked universe#lu mask#lu time#lu wild

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

RWBY Character Analysis: Pietro and Penny Polendina

Up until now I’ve been keeping quiet about my opinions on the newest volume, in no small part because my personal life has been one absurd setback after another, and I haven’t had the energy to engage in fandom meta. If you do want to know what my current opinion of RWBY is, go over to @itsclydebitches blog, search through her #rwby-recaps tag, and read every single one. At this point, her metas are basically an itemized list of all my grievances with the show. I highly recommend you check ’em out.

Or, if you don’t feel like reading several hours’ worth of recaps, then go find a sheet of paper, give yourself a papercut, and then squeeze a lemon into it. That should give you an accurate impression of my feelings.

In truth, I have a lot to say about the show, particularly how I think CRWBY has mishandled the plot, characters, tone, and intended message of their series. And while I enjoy dissecting RWBY with what amounts to mad scientist levels of glee, I think plenty of other folks have already discussed V7′s and V8′s various issues in greater depth and with far more eloquence. Any contribution I could theoretically make at this point would be somewhat redundant.

That being said, I’d like to talk about something that’s been bothering me for a while, which (to my knowledge) no one else in the fandom has brought up. (And feel free to correct me if I’m wrong.)

Today’s topic of concern is Pietro Polendina, and his relationship with Penny.

And because I’m absolutely certain this post is going to be controversial and summon anonymous armchair critics to fill my inbox with sweary claptrap, I may as well just come out and say it:

Pietro Polendina, as he’s currently portrayed in the show, is an inherently abusive parental figure.

Let me take a second to clarify that I don’t think it was RWBY’s intention to portray Pietro that way. Much like other aspects of the show, a lot of nuance is often lost when discussing the difference between intention versus implementation, or telling versus showing. It’s what happens when a writer tries to characterize a person one way, but in execution portrays them in an entirely different light. Compounding this problem is what feels like a series of rather myopic writing decisions that started as early as Volume 2, concerning Penny’s sense of agency, and how the canon would bear out the implications of an autonomous being grappling with her identity. It’s infuriating that the show has spent seven seasons staunchly refusing to ask any sort of ethical questions surrounding her existence, only to then—with minimal setup—give us Pietro’s “heartfelt” emotional breakdown when he has to choose between “saving” Penny or “sacrificing” her for the greater good.

Yeah, no thanks.

If we want to talk about why this moment read as hollow and insincere, we need to first make sure everyone’s on the same page.

Spoilers for V8.E5 - “Amity.” Let’s not waste any time.

In light of the newest episode and its—shall we say—questionable implications, I figured now was the best time to bring it up while the thoughts were still fresh in my mind. (Because nothing generates momentum quite like frothing-at-the-mouth rage.)

The first time we’re told anything about Pietro, it comes from an exchange between Penny and Ruby. From V2.E2 - “A Minor Hiccup.”

Penny: I've never been to another kingdom before. My father asked me not to venture out too far, but... You have to understand, my father loves me very much. He just worries a lot.

Ruby: Believe me, I know the feeling. But why not let us know you were okay?

Penny: I…was asked not to talk to you. Or Weiss. Or Blake. Or Yang. Anybody, really.

Ruby: Was your dad that upset?

Penny: No, it wasn’t my father.

The scene immediately diverts our attention to a public unveiling of the AK-200. A hologram of James Ironwood is presenting this newest model of Atlesian Knight to a crowd of enthusiastic spectators, along with the Atlesian Paladin, a piloted mech. During the demonstration, James informs his audience that Atlas’ military created them with the intent of removing people from the battlefield and mitigating casualties (presumably against Grimm).

Penny is quickly spotted by several soldiers, and flees. Ruby follows, and in the process the two are nearly hit by a truck. Penny’s display of strength draws a crowd and prompts her to retreat into an alley, where Ruby learns that Penny isn’t “a real girl.”

This scene continues in the next episode, “Painting the Town…”

Penny: Most girls are born, but I was made. I’m the world’s first synthetic person capable of generating an Aura. [Averts her gaze.] I’m not real…

After Ruby assures her that no, you don’t have to be organic in order to have personhood, Penny proceeds to hug her with slightly more force than necessary.

Ruby: [Muffled noise of pain.] I can see why your father would want to protect such a delicate flower!

Penny: [Releases Ruby.] Oh, he’s very sweet! My father’s the one that built me! I’m sure you would love him.

Ruby: Wow. He built you all by himself?

Penny: Well, almost! He had some help from Mr. Ironwood.

Ruby: The general? Wait, is that why those soldiers were after you?

Penny: They like to protect me, too!

Ruby: They don't think you can protect yourself?

Penny: They're not sure if I'm ready yet. One day, it will be my job to save the world, but I still have a lot left to learn. That's why my father let me come to the Vytal Festival. I want to see what it's like in the rest of the world, and test myself in the Tournament.

Their conversation is interrupted by the sound of the approaching soldiers from earlier. Despite Ruby’s protests, Penny proceeds to yeet her into the nearby dumpster, all while reassuring her that it’s to keep Ruby out of trouble, not her. When the soldiers arrive, they ask her if she’s okay, then proceed to lightly scold her for causing a scene. Penny’s told that her father “isn’t going to be happy about this,” and is then politely asked (not ordered; asked) to let them escort her back.

Let’s take a second to break down these events.

When these two episodes first aired, the wording and visuals (“No, it wasn’t my father,” followed by the cutaway to James unveiling the automatons) implied that James was the one forbidding her from interacting with other people. It’s supposed to make you think that James is being restrictive and harsh, while Pietro is meant as a foil—the sweet, but cautious father figure. But here’s the thing: both of these depictions are inaccurate, and frankly, Penny’s the one at fault here. Penny blew her cover within minutes of interacting with Ruby—a scenario that Penny was responsible for because she was sneaking off without permission. Penny is a classified, top-secret military project, as made clear by the fact that she begs Ruby to not say anything to anyone. Penny is in full acknowledgement that her existence, if made public, could cause massive issues for her (something that she’s clearly experienced before, if her line, “You’re taking this extraordinarily well,” is anything to go by).

But here’s the thing—keeping Penny on a short leash wasn’t a unilateral decision made by James. That was Pietro’s choice as well. “My father asked me not to venture out too far,” “Your father isn’t going to be happy about this”—as much as this scene is desperately trying to put the onus on James for Penny’s truant behavior, Pietro canonically shares that blame. And Penny (to some extent) is in recognition of the fact that she did something wrong.

Back in Volumes 1 – 3, before the series butchered James’ characterization, these moments were meant as pretty clever examples of foreshadowing and subverting the controlling-military-general trope. This scene is meant to illustrate that yes, Penny is craving social interaction outside of military personnel as a consequence of being hidden, but that hiding her is also a necessity. It’s a complicated situation with no easy answer, but it’s also something of a necessary evil (as Penny’s close call with the truck and her disclosing that intel to Ruby are anything to go by).

Let’s skip ahead to Volume 7, shortly after Watts tampered with the drone footage and framed her for several deaths. In V7.E7 - “Worst Case Scenario,” a newscaster informs us that people in Atlas and Mantle want Penny to be deactivated, despite James’ insistence that the footage was doctored and Penny didn’t go on a killing spree. The public’s unfavorable opinion of Penny—a sentiment that Jacques of all people embodies when he brings it up in V7.E8—reinforces V2’s assessment of why keeping her secret was necessary. Not only is her existence controversial because Aura research is still taboo, but people are afraid that a mechanical person with military-grade hardware could be hacked and weaponized against them. (Something which Volume 8 actually validates when James has Watts take control of her in the most recent episode.)

But I digress.

We’re taken to Pietro’s lab, where Penny is hooked up to some sort of recharge/docking station. Ruby, Weiss, and Maria look on in concern while the machine is uploading the visual data from her systems. There’s one part of their conversation I want to focus on in particular:

Pietro: When the general first challenged us to find the next breakthrough in defense technology, most of my colleagues pursued more obvious choices. I was one of the few who believed in looking inward for inspiration.

Ruby: You wanted a protector with a soul.

Pietro: I did. And when General Ironwood saw her, he did too. Much to my surprise, the Penny Project was chosen over all the other proposals.

Allow me to break down their conversation so we can fully appreciate what he’s actually saying.

The Penny Project was picked as the candidate for the next breakthrough in defense technology.

Pietro wanted a protector with a SOUL.

In RWBY, Aura and souls are one of the defining characteristics of personhood. Personhood is central to Penny’s identity and internal conflict (particularly when we consider that she’s based on Pinocchio). That’s why Penny accepts Ruby’s reassurances that she’s a real person. That’s why she wants to have emotional connections with others.

What makes that revelation disturbing is when you realize that Pietro knowingly created a child soldier.

Look, there’s no getting around this. Pietro fully admits that he wanted to create a person—a human being—a fucking child—as a "defense technology” to throw at the Grimm (and by extension, Salem). Everything, from the language he uses, to the mere fact that he entered Penny in the Vytal Tournament as a proving ground where she could “test [her]self,” tells us that he either didn’t consider or didn’t care about the implications behind his proposal.

When you break it all down, this is what we end up with:

“Hey, I have an idea: Why don’t we make a person, cram as many weapons as we can fit into that person, and then inform her every day for the rest of her life that she was built for the sole purpose of fighting monsters, just so we don’t have to risk the lives of others. Let’s then take away anything remotely resembling autonomy, minimize her interactions with people, and basically indoctrinate her into thinking that this is something she wants for herself. Oh, and in case she starts to raise objections, remind her that I donated part of my soul to her. If we make her feel guilty about this generous sacrifice I made so she could have the privilege of existing, she won’t question our motives. Next, let’s give her a taste of freedom by having her fight in a gladiatorial blood sport so that we can prove our child soldier is an effective killer. And then, after she’s brutally murdered on international television, we can rebuild her and assign her to protecting an entire city that’s inherently prejudiced against her, all while I brood in my lab about how sad I am.”

Holy fuck. Watts might be a morally bankrupt asshole, but at least his proposal didn’t hinge on manufacturing state-of-the-art living weapons. They should have just gone with his idea.

(Which, hilariously enough, they did. Watts is the inventor of the Paladins—Paladins which, I’ll remind you, were invented so the army could remove people from the battlefield. You know, people. Kind of like what Penny is.)

Do you see why this entire scene might have pissed me off? Even if the show didn’t intend for any of this to be the case, when you think critically about the circumstances there’s no denying the tacit implications.

To reiterate, V8.E5 is the episode where Pietro says, and I quote:

“I don’t care about the big picture! I care about my daughter! I lost you before. Are you asking me to go through that again? No. I want the chance to watch you live your life.”

Oh, yeah? And what life is that? The one where she’s supposed to kill Grimm and literally nothing else? You do realize that she died specifically because you made her for the purpose of fighting, right?

No one, literally no one, was holding a gun to Pietro’s head and telling him that he had to build a living weapon. That was his idea. He chose to do that.

Remember when Cinder said, “I don’t serve anyone! And you wouldn’t either, if you weren’t built that way.” She…basically has a point. Penny has never been given the option to explore the world in a capacity where she wasn’t charged with defending it by her father. We know she doesn’t have many friends, courtesy of Ironwood dissuading her against it in V7. But I’m left with the troubling realization that the show (and the fandom), in their crusade to vilify James, are ignoring the fact that Pietro is also complicit in this behavior by virtue of being her creator. If we condemn the man that prevents Penny from having relationships, then what will we do to the man who forced her into that existence in the first place?

Being her “father” has given him a free pass to overlook the ethics of having a child who was created with a pre-planned purpose. How the hell did the show intend for Pietro to reconcile “I want you to live your life” with “I created you so you’d spend your life defending the world”? It viscerally reminds me of the sort of narcissistic parents who have kids because they want to pass on the family name, or continue their bloodline, or have live-in caregivers when they get older, only on a larger and much more horrific scale. And that’s fucked up.

Now, I’m not saying I’m against having a conflict like this in the show. In fact, I’d love to have a character who has to grapple with her own humanity while questioning the environment she grew up in. Penny is a character who is extremely fascinating because of all the potential she represents—a young woman who through a chance encounter befriends a group of strangers, and over time, is exposed to freedoms and friendships she was previously denied. Slowly, she begins to unlearn the mindset she was indoctrinated with, and starts to petition for agency and autonomy. Pietro is forced to confront the fact that what he did was traumatic and cruel, and that his love for her doesn’t erase the harm he unintentionally subjected her to, nor does it change the fact that he knowingly burdened a person with a responsibility she never consented to. There’s a wealth of character growth and narrative payoff buried here, but like most things in RWBY, it was either underdeveloped or not thought through all the way.

The wholesome father-daughter relationship the show wants Pietro and Penny to have is fundamentally contradicted by the nature of her existence, and the fact that no one (besides the villains) calls attention to it. I’d love for them to have that sort of dynamic, but the show had to do more to earn it. Instead, it’ll forever be another item on RWBY’s ever-growing list of disappointments—

Because Pietro’s remorse is more artificial than Penny could ever hope to be.

#rwby#rwby volume 8#rwby spoilers#rwby thought dump#my posts#i speak#rwby meta#pietro polendina#penny polendina#james ironwood#arthur watts#ruby rose#rwby worldbuilding#rwde

53 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Why don’t any of you pay attention when you always have the privilege to see?

Orange without his big toothy grin looks really off to me, though that’s just because he doesn’t drop it often in front of people.

I literally…can’t stop thinking about this guy… So I’m gonna talk about him in some more depth for fun! (And also so I can get it outta my system o///o) I drew him a couple times before this, but just to be clear, he’s a personal version of the Orange side I made. Though it’s not really a theory, since I am 100% sure I am incorrect, this is just purely for my own enjoyment because I ended up?? Really liking him as a character??? W h o o p s. >///<

So yeah, don’t mind me as I just talk about him a bit... It’s just some random scattered notes about him I really want to put down somewhere...

He does have a name, but I’m not gonna talk about it for now.

He represents a bunch of things, but his main embodiment is that of anger, mostly in the form of blind rage. He is 100% blind most of the time and possesses dull brown-orange eyes. The only circumstance in which he can see is when he wears Logan’s glasses, and his eyes turn blue within that duration of time. Due to his disability, he tends to jokingly ask people to do him favors, but he actually kind of despises the fact that he’s blind. Not because he can’t see though, it’s because he thinks everyone else is taking their own sight for granted. His eyesight is actually scarily clear when he can actually see, and it makes him think other people are wasting it. (He’s actually more perceptive because he can’t see normally)

It’s incredibly important to remember that Orange is in fact, another aspect of Logic. He is based on the real life phenomena in which anger can sharpen one’s critical thinking and concentration in small doses. Wearing Logan’s glasses gives him the clarity he needs to rip people’s arguments apart, and he is particularly efficient at bringing up things people often overlook as evidence for his case. He’s sharp, but also incredibly blunt and straight to the point, as funny as that sounds. He’s who takes the reigns when regular logical reasoning fails, and he’s no where near as nice or understanding. If he goes too far however, Logan’s glasses will break and he’ll turn blind again and lash out. If it goes farther than that he’ll actually also start to lose hearing. Which makes him really destructive in the long term, and while Orange is fully aware of that, he can’t help but get carried away sometimes. Which is why he only ever gets to do anything if Logan is out of commission.

Now that’s him when he’s serious, but most of the time he’s actually kind of a big goof. He’s got this really blasé and laid back attitude to him, which mostly stems from the fact that he doesn’t have much to do. I describe him as a rat bastard because I love depicting him as a gremlin, and he most certainly can be. He is also 100% the type of guy to take threats seriously for fun, and will throw down with you if you suggest it. He’s awfully perceptive and knows when chaos is happening but will still be that guy who says he “can’t see” the problem and laugh. Honestly not one above causing trouble just for the fun of it. He’s sly, often coy, and acts like he doesn’t take anything seriously, which is why when he does, he really does. He tends to think that things would be much easier if he was allowed to look at the issue, but his impatience when dealing with things is probably why he’s not the one usually in the driver’s seat.

Another important thing to note that alongside anger, he actually partially represents self respect. Similar to how Janus is self preservation alongside deceit. Orange is completely focused on the self, and will argue things accordingly to benefit that. He’s that voice that tells you that you don’t deserve to be treated that way or that wanting to be treated better isn’t an unreasonable request and pushes you to actively fight for and demand it. That attitude is where his relationship with Logan kind of fits into the puzzle, and while I find their dynamic interesting I think it’d take too long to actually get into and this is already plenty self indulgent as it is fajkfbeg. Note that he’s not ego, he is very different from self esteem. He’s more like the embodiment of “Being garbage still doesn’t mean that I get to take shit from you”.

He habitually chews things, which is why the collar of his shirt is absolutely destroyed. When he’s really antsy, he also bites his nails. He likes to call people by color because it’s the most identifiable thing about them from what he remembers during his short periods of sight. Except Patton, who he probably calls “Pops”, in a more sarcastic way if anything. Since they probably disagree a ton.

There’s a funky mafia? AU I imagined with him in it, but thaaaat’s not gonna be elaborated on any time soon. I also semi-made a playlist for him for fun.

Thanks for reading my rambles? If you’re here?? Honestly I just like him a lot for some reason, hhhh- >///< I have fun imagining stuff for him, but I can’t really say how much I’ll actually use him. I just like talking about things way too much akjfbakegt. See ya around! u///u

#I got back from a loooong walk with friends and I'm exhausted#so here's some barely coherent rambling#mockdoodles#sanders sides doodles#orange side#scars#Marcus

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

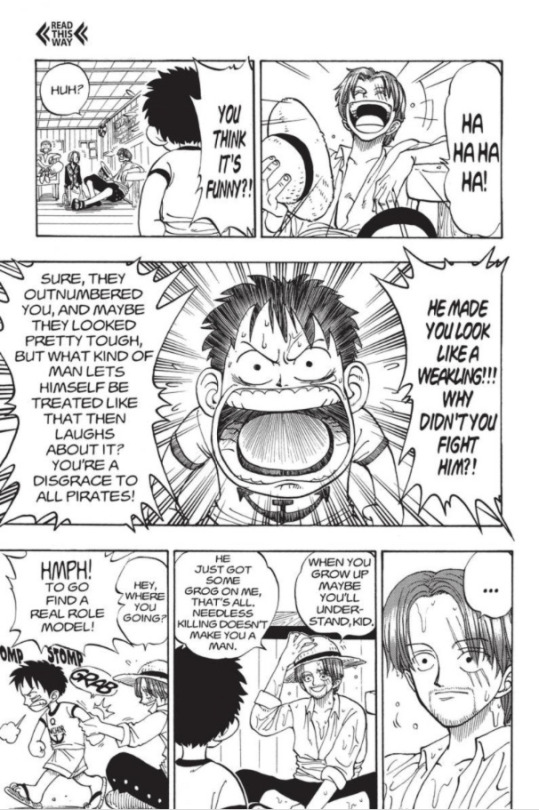

Absurd Person #1 - Monkey D. Luffy (kid)

Let’s start with not only the main protagonist of One Piece but also the first character to give Luffy any sort of injury...

...his dumb, seven-year-old self...

*Disclaimer: I don’t own this image - screenshot from Episode of East Blue

The last time I wrote this, I forgot to hit save and my browser just reloaded the page and lost everything. After that I just went “I’m done” and rage quit Tumblr for the night (which I normally don’t do). That’s how my Sundays usually go😒🥴

Now Onward!

Basic Classifications

Real World Ethnicity/Nationality: Brazilian

Class: farm / country / lower class

Culture (the one he grew up around): Dawn Island - Sea-side village

Fishing community

Farming / Ranching community

Hard work ethic

Small and close community members; relatively friendly; little to non-existent conflict

Selective mix of being open towards strangers (especially with merchant vessels for better trading opportunities) and weariness towards those they expect to be harmful (likes Pirates; I’d imagine the people of Windmill Village were understandably unnerved with the Red-Haired Pirates first showing up).

Core values (personal to Luffy): pride, physical strength, adventures on and outside his home village,

Relation to authority: neutral - shifting slightly towards negative (no clear basis of opinion; can only go off on Luffy’s fascination with pirates as the main viewpoint)

(The added information feels a little scatter-shot but figured I give it a try based on little information from the manga panels and how it lines up with real-world similarities. Most information is based on logical speculation and could change with new information in later chapters.)

I know that the Romance Dawn arc consists of the chapters up until he meets Coby and Alvida (I think...), but the depiction of Luffy’s character in the first chapter seems different from when he is seventeen and setting out to sea. So, I’ll treat kid Luffy as a separate character for the first analysis.

First Impressions and Introduction

Now, I am an anime watcher, first and foremost, so my first impression of this character stems from the Anime. My introduction towards this ball of chaos was when he popped out of a barrel, that he put himself into after realizing that a whirlpool suddenly appeared (how he missed it? - It’s Luffy), and then inexplicably took a nap in. That was the absurd reason I was able to stick with One Piece in the first few arcs (until Baratie became one of the major reasons I stuck with it - I’ll explain why when we get there).

And since the first chapter was used for episode four in the anime, I was already somewhat familiar with how the story started and who Luffy was as a kid. However, reading the first chapter felt....different than what I would’ve expected. And because the anime cut out a few details from the chapter, there definitely are some things to take from kid Luffy at that point.

So my first impression was, as follows:

The kid is unhinged...That explains some things...

Complete wild child of a backwater village from Day 1.

LIKE-- The anime episode DID NOT explain how he got that scar and the guy didn’t bring it up ever. To be fair, that wasn’t a big focus because the anime didn’t make it a focus. Reading that part though did more for his character and a little of his upbringing, through speculation, making it a rather slow-building but also fascinating introduction into this series.

Just a bit of an add-on, but if the manga introduced Luffy in the same level of neutrality as what the Anime did, It may not have fully made it clear if Luffy was going to be the main protagonist. Then again, it’s a shounen manga, maybe it was rather obvious to everyone else. Regardless, his introduction served to

(1) Make his entrance memorable

(2) Establish his character that could either compare or set him apart from his teen self.

(3) Act as a sort of precursor towards the introduction of Luffy’s world and upbringing (which isn’t completely established until the last few arcs of Pre-Time Skip)

Personality

The best way I could describe Luffy at this point is a stereotypical kid...

Energetic, short-tempered, adventure-seeking, easily impressed, and ignorant...

That last description is actually something I brought up in a separate post about the “Fluid themes” of One Piece. Because I found that a small but overarching part in many (almost all) themes and world issues that One Piece reflects has some level of unawareness or apathy. Jimbe put it best during the Fishman Island Flashback when they found Koala (paraphrasing)

“They are afraid of us because they don’t know us.”

Know us referring to acknowledging them as people on the same level as humans.

Because of that and plenty of other instances from the East Blue, it can be a potential center for many characters who go up against or wish to explore the world and find that they are a frog in a well.

And that’s what kid Luffy represents. A rather aggressive frog in a well that wants out.

Granted, he is a seven-year-old, whose schooling has a closer equivalent to the 16th and 17th centuries of our world, living in what appears to be a farming community, so I’d imagine his education only focuses on at least the basic levels of reading/writing, mathematics, etc. A small, unexciting farming village probably has more concerns over their melon crops rather than what the world has going on. Adding in Luffy, you get a kid who dreams about being a pirate and adventuring outside the isolated village, making him avidly interested in a world he has no experience with. Or in a world he thinks is all fun and games.

That’s pretty standard for any child that has a mild and peaceful life. No doubt Shanks and his crew would tell him stories about their adventures. Not as a sort of attempt to make him a pirate, but because he was easily entertained by it, building up this expectation with stereotypical pirate personas. And whether he has his “destructive” tendencies before they became a fixture in Windmill Village, they definitely seemed to amp it up enough for Luffy to try and prove he was “man enough” to be a pirate at seven years old.

Then when you add in this idealistic expectation with the selfishness of a young child, it creates an opportunity to learn. Because, as any kid may go through, will find that their fantasy of the world won’t be what they expected, and will often react negatively. Luffy’s expectation of Shanks is that he is the strongest man worthy enough to be a pirate.

Now, Luffy’s view of a “real man” stems a lot from this stereotype of men solving their problems through fighting only. Which also embodies this rather damaging philosophy of never running away or backing down from a fight (which I refer to as stupid bravery - something that comes up in a certain other character).

The amazing thing about all the combined aspects of this kid is the ability to create a learning lesson for Luffy. Which can become a motivational factor in his pursuit as a pirate.

His easily impressed nature makes it known both when the Red-Haired Pirates talk positively about piracy adventures and when Shanks leaves the village. The difference between the moments can be showcased by the difference in determination and will to make an effort to achieve his dream. As he declared he wants to be King of The Pirates, he sets himself to work at it, rather than try and go with others.

How He Shapes the Story / World Around Them

I don’t know if anybody else made a similar connection (I wanna say someone DID but I can’t remember where) but in combination with Luffy’s general enthusiasm growing up hearing wild stories, his narrative reminds me so much of Don Quixote De La Mancha.

It’s been a while since I last read that story-- and by read I mean translate some paragraphs from Spanish to English during my Spanish I class in freshman year of high school. Nonetheless, I thoroughly enjoyed the story. Part I entails an old man who, after indulging himself with various stories of knights and valor, decides he wants to partake in his own adventures. Under various delusions and misadventures, his story becomes a rather well-known one.

Don Quixote was called the first “modern book”. That was something my Spanish teacher mentioned regarding its acknowledgment by the world and always stuck with me. It was one of the first stories of the early medieval period to focus on a regular man. Other stories before this tended to be about legends, gods, demigods-- individuals who often were referred to as legends because they were born into high status (often above humans). Either through original texts (often for religious purposes) and then through varying interpretations (such as the Arthurian Legends), these tales were a part of the status quo.

Kid Luffy is a person that reflects so much of the Don Quixote story (And not just because his village has windmills-- the most iconic scene about the knight’s story). He is that simple, normal boy that longs for his own adventures when there seemingly is already a well-talked-about story about someone who achieved infamy. In place of that is a man named Gold Roger whose execution we see in the manga’s opening. At this point, we don’t have much understanding about how it impacts the world as of yet, we just know it is setting up for something significant to the story.

Luffy becomes that “regular” person from a small-town with big expectations for a grand adventure.

That perspective can slowly build into the story by starting in a simple setting with a character going through one of the first dynamic changes in his life. Luffy’s experience with Shanks’s sacrifice sets a course in his own adventure. A story that trails into a rather bonkers adventure at the end of chapter 1.

His development is what shaped his world. It’s the way he learns when as it stems from the consequences of his actions. Especially ones where the smaller ones turn out to be very costly, making it a hard lesson that ingrains into the young kid. His actions created by his old ideologies sparked an intense reaction in the people around him. Especially Shanks, who felt he was worth losing an arm towards.

How The WORLD Shapes HIM

So, for the sake of the fact that kid Luffy’s “World” in Chapter 1 mostly consists of Windmill Village, I’m adding in Shank’s and his crew’s influence to extend and further give credence to his influence. Because, as of this point, Shanks represents a glimpse into the life of a pirate that Luffy strives for.

With Luffy being in a quiet environment all seven years of life, there is growth through basic schooling and healthy child development (theoretically since Makino seems to be the most likely one acting as his guardian), instead of doing things outside that norm. Now Shanks is the odd factor that creates new development into Luffy’s dreams and future ambitions.

The crew’s stories, charisma, and connection towards the kid actively (and probably unintentionally) created a positive expectation if he chose to pursue his dream. While that sounds inspiring, there were also negative aspects. Such as driving his ignorance and impatient nature to seek it out too early in his life.

Shanks then became a mediator. Luffy often has mixed feelings with Shanks as the man begets a level of encouragement while verbally making fun of Luffy for being a kid constantly. Despite that, it doesn’t completely deter Luffy’s ambitions. All it does is slowly drop his high expectations in Shanks after the first bar incident. This is again done by his childish outlook of physical strength and bravery equating to his ideal of a real man.

With Higama, Luffy learns about real-world dangers, and how bravery won’t always be enough to win battles. The same can be said for physical strength but at that moment it doesn’t apply to Luffy.

Shanks’ and the crew’s involvement helped Luffy’s views change. His expectations are fulfilled, which in turn reveal that he was wrong about them.

Finally, seeing Shanks’ sacrifice unfold drove Luffy into a pang of newfound guilt. By then, he was able to change one part of his world views from a childish fantasy into the beginnings of a mature way of thinking.

He gains some level of patience. Along with a set goal to work with. Attributes which are identifiable with Luffy in the chapters last few panels.

Patience = Luffy took time to train and learn to set sail at age seventeen.

Set goal = Be King of the Pirates

Add-Ons

When I say that kid Luffy, after Shanks’ sacrifice, gained a level of patience, it is meant as a deduction during that chapter. By no means am I insinuating that it became a permanent trait for his character. Because as of chapter 1, all of Luffy’s personality has yet to be revealed.

And this will apply to other posts for various characters. They may behave in ways during or in response to a particular event but it doesn’t necessarily equate to that becoming a whole personality trait. Calling Luffy patient, with having full acknowledgment of his personality during the bulk of One Piece, is completely off. But, there can and will be moments where Luffy will act patient when he deems it necessary.

This is a little hard to articulate but I hope it makes enough sense.

🏴☠️🐒

After-Notes

Here’s my first attempt at this analysis. It felt scattered even after editing everything. Breaking down characters sounds easy (and most times it is) but articulating and connecting things takes a lot of work.

Here's to hoping it gets easier with the next character. And maybe shorter paragraphs.

Up Next: Shanks (East Blue)

#OPA#One Piece#East Blue Saga#Romance Dawn Arc#Monkey D. Luffy#Chapter 1#One Piece Characters#Worldbuilding#Analysis

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

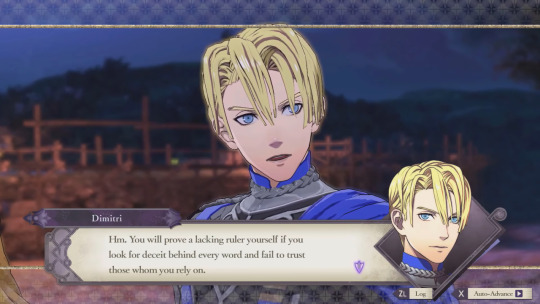

Dimitri and mental illness

**Warnings for Blue Lions spoilers and armchair psychology

Depending on who you ask, Dimitri is an innocent sweetheart whose actions are entirely excusable and justified or an unforgivable war criminal and overall terrible character. Arguments for both sides have been exhausted, usually in the form of the popular Edelgard versus Dimitri debate, but I feel that both statements are heavily flawed and, truthfully, I think I take more issue with the former. Does it strike anyone else as rather patronizing that the audience (and the game, to an extent) treats Dimitri like an innocent, broken uwu soft boy both before the time skip and once he begins his recovery arc? Of course, a lot of this can be blamed on the awful pacing and poor writing of said recovery (which is the most valid structural critique of his character imo), but there’s a lot to be said about the fan depiction of Dimitri and the way people treat his mental illness. I think the reason this gets me is because I see it as an extension of the problems I have with the romanticization of male-specific mental illness. In this case, “all depressed boys are emasculated, soft, sad bois” and “anger is an accessory that is vanished once the cute boy takes it off” with the related sentiment of “the only two real mental illnesses are depression and anxiety, with a splash of PTSD for argument's sake”. And, speaking of arguments, while many people bring up mental illness in regards to the discussion around Three Houses characters, it is often supplementary to support their points rather than the main point unto itself. Dimitri’s mental illness (aka, the thing his entire arc is predicated upon) is mostly given only a passing recognition in the discussion of his actions. Even then, it’s often used as a justification to defend or lambaste him.

TL;DR Dimitri is a flawed person with a debilitating and incredibly well written mental illness that, while not excusing his actions, allows for further exploration of his character and a well-deserved shot at a recovery arc that is not usually awarded to people with the “non-traditional” mental illnesses. Furthermore, the game offers a wealth of insight as to what they intended his mental illness to be, the symptoms that manifested, and a plausible background to match up with it all and I have the receipts to prove it. Let’s go~

“Me? Oh. Um. Please forgive me... It's difficult to open up on the spot, don't you think? I'm afraid my story has not been a pleasant one... I do hope that doesn't color your view of me, but I understand if that can't be helped.”

I know that mental illness can be singularly caused by a traumatic event or events. That is, generally, how I see people framing Dimitri’s mental illness. My argument, however, is that the Tragedy of Duscur was not the genesis, but the trigger for issues that would exist otherwise. Perhaps it’s due to my own personal experience with mental illness, but I’m almost always more inclined to believe that issues stem from an unlucky combination of many things.

Regardless, my evidence to entertain the idea that he would be naturally predisposed to mental illness is slim. Aside from arguing that it wouldn’t be out of the question for his mother to have been unwell while she was pregnant with him considering she would later die of plague (a cause that in and of itself is subject to skepticism), I would bring up his Crest. In-game there is clear proof that Crests have wide-reaching effects on the person, there are actually a few analysis posts that hypothesize that Crests could be the reason for certain character motivations. In ng+, the Crest of Blaiddyd is called the Grim Dragon Sign. There’s no definitive proof to point to here, but if his Crest was one of the reasons for his mental deterioration it would follow other rules set in-game. Rather than inherited human genetics creating the blueprint for mental issues and the writers having to face that issue on its own terms, it was the Crest’s influence. This goes along with the fact that the game never overtly references Dimitri’s illness, essentially using “the dead” as a blanket symptom of his problems. Both these things are cool ways to imply a possible way to read more deeply without having to use anachronistic medical terms.

Side note: There’s something uncomfortable about the idea of a Crest that gives the individual inhuman strength and mental issues. Grim Dragon indeed.

My next point is one that I don’t see being brought up too often in regards to how it might have affected Dimitri, likely because the events that came later in his life far overshadow it, but Dimitri lost his mom when he was young. The date is not given, but I think it’d be when he was about six-ish. Admittedly, the timeline is strange and non-specific around here but if that were true, it would mean that the plague, Dimitri’s mother’s death, and Lambert and Rodrigue’s war campaign to subjugate the southern half of Sreng would all have happened around the same time. Dimitri says he doesn’t remember it, but that doesn’t necessarily matter. At six years old he had lost one parent and the other one left him to go on a battle march, leaving this child without any sort of parent figure to console him in a country that is culturally opposed to expressing emotion. Lambert will probably always remain a mystery, but I think it could be fair to say he was a poor father. Or at the very least a distant one. Dimitri was undoubtedly a sensitive child (if we’re to judge by the sensitive person he grew up to be) and during the years where he was actually becoming old enough to remember, he had nobody to teach him how to properly navigate and manage his emotions. Emotional neglect in a child who is predisposed to being emotional and empathetic can leave them suffering from a sense of isolation, an inability to ask for help, and a predisposition to having break downs as they get older.

But three-ish years later, possibly one of the best things that ever would happen to Dimitri came to pass and Lambert married Patricia. Dimitri adored her.

“I share no blood with my stepmother, but to hear you say that... It pleases me greatly. She was the one who raised me. I suppose it makes sense that we would share certain mannerisms.” (Dimitri’s B support with Hapi)

I don’t think Dimitri’s feelings about Patricia can be overstated, as I feel it’s one of the most defining aspects of his reactions to things that happen later on. Dimitri talks about Patricia more lovingly than he talks about Lambert. She was in his life for around four to five years but had such an impact on him that even his mannerisms are similar.

Soon after, a ten-year-old Dimitri made his first friend that wasn’t knightly, who didn’t embody those Faerghus ideals of stifling emotions and swinging swords.

People point out the Faerghus crew as Dimitri’s best friends, and yet Edelgard is the one associated with his best memories. It’s just my own assumptions, but I think that it’s because both Edelgard and Patricia gave Dimitri space to be an emotional child, to not have to be the knightly prince who had no emotions and engaged only in the most masculine of activities. And, I mean, look at them. He’s learning to dance and she’s bossing him around, absolutely no regard for propriety.

It’s pretty clear that Dimitri doesn’t feel romantic feelings towards Edelgard in the academy phase, but I think it would be fair to say she was his first love when they were young. He essentially says this was the best year of his life and establishes Edelgard as someone very precious to him (as well as the daughter of one of the most precious people to him). Strong feelings beget strong feelings, do they not?

Google says that eleven to fourteen is the general age of male puberty. It’s the time that kids begin to more fully define how they’re going to emotionally interact with people and the world at large. Meeting Edelgard was at the cusp of this period of Dimitri’s life, and the Tragedy of Duscur was right in the midst of it.

And we all know what that turned out.

Dimitri’s accounts of what happened during the Tragedy are... conflicting. This CG of an unharmed Dimitri in a field of corpses is... conflicting.

“My father...was the strongest man I knew. Someone I loved and admired deeply. That said, he was killed before my eyes. His head severed clean off. My stepmother, the kindest person I had ever known, left me behind and disappeared into the infernal flames.”

I’ve seen people create a plausible scenario in which Dimitri’s recollection is entirely accurate, where he saw Lambert call for revenge and get beheaded, saw Glenn’s ruined body and face twisted in pain, saw his step-mother disappear into the flames, and all despite the raging chaos of the battle and how people would undoubtedly be targeting the prince, but I think it makes more sense that his memories are unreliable. Dimitri suffered a severe head injury (very important to keep in mind) at Duscur. Maybe that happened early on, after seeing who attacked Lambert but before he was an actual target himself, which merely made him look dead. Maybe he saw a version of the events he described, but through the filter of confused head trauma, smoke inhalation, and intense terror. To think that his recollection isn’t exactly entirely reliable sets a precedent for his later skewed take on reality.

Regardless of opinion, though, the facts are that Dimitri left Duscur with a traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder.

After that, from thirteen to seventeen, Dimitri was pretty isolated. Most of the people he cared about were dead. His entire emotional support system (Patricia) was gone. He saved Dedue (although they were definitely not on even terms, that relationship is unbalanced to the extreme) and occasionally saw Rodrigue (who I have no reason to believe was emotionally accommodating in any way considering the way he sees Dimitri as an extension of Lambert to his dying breath). Again, it’s strange. People act like Dimitri was super close friends with the Faerghus crew, that he was surrounded by people who loved him (although it is clear there is a lot of love there), but he never presents things in a way to imply that’s the case. In fact, he highlights his isolation:

“In Duscur, I lost my father, stepmother, and closest friends. I didn't have many allies at the castle after that. In truth, I had only Dedue for companionship.”... “I once had people I could confide in. Family, friends, instructors, even the royal soldiers. But they were all taken away from me four years ago.” (Dimitri’s C support with Byleth.)

Two years passed before the next time Dimitri saw his friends and it was a war campaign, putting down the rebellion in western Faerghus. Dimitri speaks about those battles from a place of deeply affected emotion, expressing empathy, pain, and disgust with his actions and the killing.

“I recall coming across a dead soldier's body. He was clutching a locket. Inside was a lock of golden hair. I don't know to whom it belonged. His wife, his daughter...mother, lover... I'll never know.... in that moment, I realized he was also a real person, just like the rest of us… Killing is part of the job, but even so... There are times when I'm chilled to the bone by the depravity of my own actions.” (Dimitri’s B Support with Byleth)

I love this support, honestly. It’s so very telling about the destructive quality of empathy. Although caring can be a good thing, it’s also arguably one of the most destructive of Dimitri’s qualities. His empathy is what presents him with situations he cannot accept, the thing that pushes him to disassociate from reality so he can be rid of it and fight without remorse like he was taught to do by his father and other soldiers. Dimitri is a man of extremes. Either total control or none, without any room for error. This dialogue is also the first time Dimitri brings up reconciling himself with reality and hints to the fact that he has been unable to do so. This is contrasted perfectly in this line from Felix,

“The way you suppressed that rebellion... It was ruthless slaughter and you loved every second. I remember the way you killed your victims. How you watched them suffer. And your face...that expression. All the world's evil packed into it...” (Dimitri’s C Support with Felix)

Dimitri doesn’t deny this. Just like all of the other terrible things Felix says, he takes it without protesting in an act of what I think is stilted contrition. Although, it’s not just in supports that Dimitri’s contrasting behavior is brought up. The Remire incident probably works as a good reference for what Felix saw all those years back.

This is the first time we see Dimitri’s darker side in full. The similarities in the situation to what is shown to have happened in the Tragedy of Duscur are interesting. The fire, the utter chaos, strange figures watching it all from above. This is another case of a perfect disaster. I wonder if his ultimate snap would have been so destructive if not for Remire.

Anyway, this draws parallels to his and Felix’s separate recall of the rebellion because later Dimitri apologizes.

“Professor... I...I'm sorry you saw that side of me in the village… When I saw the chaos and violence there...my mind just went completely dark.”

Dimitri is unreliable. A lack of control, a separation of self, and becoming consumed by a dark rage only to come to his senses later, full of shame and a sense of confusion about why. From my own experience, it’s not unnatural to come out of an episode like this without being able to explain what was happening and being baffled by your behavior. This firmly establishes Dimitri’s uncomfortably fast mood shifts in relation to his trauma from the Tragedy and confirms all of the warnings Felix had given. When Dimitri was faced with a reality he could not accept, he lost control of his emotions and his mental state shifted to adapt accordingly.

This is when I’d also like to note something interesting about how Dimitri discusses his trauma. He is very honest and open about his experiences, explaining exactly what happened to him to Byleth. However, he uses the truth to hide. In recounting the events of the Tragedy of Duscur, in talking about how his family died and saying how badly it hurt him, he does not make himself vulnerable. When he admits weakness, he does so in the past tense or apologetically, vowing to be stronger. “Stronger”, aka, he’ll be better in suppressing his emotions.

“I always strive to keep my emotions at bay, but... Sometimes the darkness takes hold and...it's impossible to suppress. It just shows you how lacking I am... I have much to learn.”

Dimitri lies by using the truth, shoving down his feelings, and blaming himself rather than attempting to figure out how to handle his emotions. In his own words:

“Everyone has something that is unacceptable within them. I certainly do, and I'd wager you do as well. I wonder which is best, Professor... To cut away that which is unacceptable, or to find a way to accept it anyway...”

Good advice Dimitri. Might want to keep that in mind.

It is at this point is when I’m going to get into my personal thoughts and armchair psychiatry nonsense.

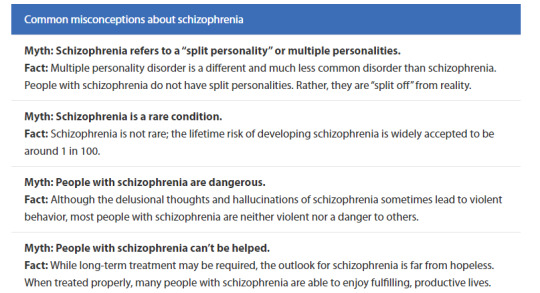

First off, when I mentioned earlier about “non-traditional” mental illness, I did not mean abnormal or rare. Although people mostly just point to Dimitri having PTSD (and depression) as the source of his issues, I’m going to use all of my above information to make the (decently common) argument that Dimitri is schizophrenic, which is, contrary to popular belief, not too unusual. I state that with the caveat that I understand that there’s a lot to be said about schizophrenia and the tumultuous relationship between mental health and fiction. However, now is not really the time to go into mental health politics and representation or the many lies spread about the illness so instead, I recommend that you read into the topic if you’re personally interested (This has some good information).

At the very least be aware that this IS sensationalized.

That said, Dimitri does not, to my understanding using grossly simplified terms, meet the qualifications generally (very generally) used to diagnose schizophrenia through the majority of the White Clouds chapters. These qualifying symptoms include, but are not limited to, the duration of the psychotic episode, the concurrent presence of hallucinations and delusions, and a greatly lowered ability to keep up with basic quality-of-life tasks. You only see these symptoms in the final chapter of White Clouds and the first few of Azure Moon. This isn’t unusual, however, because schizophrenia manifesting fully in younger individuals is extremely uncommon, sometimes taking years to trigger during a person’s late teens. And since the diagnosis generally relies on the occurrence of a psychotic episode, it can be mistaken as other mood disorders. Actually, the idea of him having a mood disorder was one of the things that caught my eye originally. Prodromal symptoms such as depression, irritability, headaches, sleep disruption, and mood swings are common in bipolar disorder (and, of course, schizophrenia).

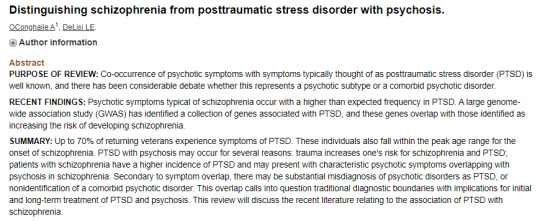

Still, I don't deny that Dimitri has PTSD and depression, only that I don’t think PTSD is his main (or only) issue. In reality, PTSD and schizophrenia are closely tied. They share many symptoms, even the symptom of psychosis. There’s also evidence that those with genetic precedent to develop PTSD overlap with those at risk for schizophrenia, and that the nature of PTSD triggers can act as a severe stressor to aggravate a schizophrenic episode.

(From here)

This falls into the realm of being uncertain where one ends the other begins, highlighting the lack of concrete understanding about schizophrenia and the dependency of diagnosis and treatment to rely entirely on the individual experience, but that’s not a conversation I’m actually qualified to have.

The study that truly caught my eye and while researching for this was one called “Psychiatric disorders and traumatic brain injury”. As I mentioned, at some point during the Tragedy, Dimitri sustained severe head trauma. We know this because of his development of the rare inability to taste called ageusia. I was originally interested in following this narrative thread because, as you might know if you follow true crime cases, there are many murderers who recall having sustained a head injury as children. Not that Dimitri shares similar psychology to people that kill and eat their victim's feet... Although his body count is higher. Besides that, head trauma, in general, is known to be linked to mental illness and altering a person’s behavior. There is even a correlation between TBI (traumatic brain injury) and schizophrenia.

From the study I linked above:

To put it more simply, patients in the study who had suffered TBI and developed schizophrenia reported that their most common symptoms were delusions of persecution, auditory hallucinations, and aggressive behaviors. The auditory hallucinations were often voices. Many of the subjects experienced psychotic episodes two or more years after the initial incident (although, as I mentioned, Dimitri’s age could also have something to do with the timing as children rarely have fully developed schizophrenic episodes). Furthermore, the behaviors classified as an absence of normal behaviors called “negative symptoms” (which include apathy and disordered speech) were rare in this testing group.

Dimitri exclusively displays “positive” symptoms of schizophrenia (“positive” meaning the presence of symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions). He also clearly suffers from delusions of persecution in his belief that Edelgard is the sole instigator of Duscur and the war and that he immediately accuses Byleth of being an Imperial spy upon meeting them post time skip. I think it’s pretty fascinating how closely Dimitri’s symptoms follow the outline of the study, especially with the aggressive behaviors, as those aren’t actually very common in schizophrenics.

In very, very simplistic terms, if I’m right and Dimitri was born with the genetic blueprint for schizophrenia/PTSD (through Crests, inheritance, or environmental causes) and later suffered severe head trauma in an event that also gave him PTSD in combination with his pre-existing parental issues and stilted emotional development, then this could definitely create the type of person who loses all sense of reality, can’t control his emotions, and is prone to episodes of murderous rage when being reminded of the trigger (however tangentially) of losing everything he loved.

However, I’ll add real quick that the study I mentioned should be taken with a grain of salt.

I use it mainly because I thought the similarities were interesting and it shows that there was more thought put into Dimitri than maybe people appreciate.

This brings us to my final point; Some kind of twisted joke.

A major point I saw being made as proof of how terrible Dimitri is as a character was that he blamed Edelgard for the Tragedy of Duscur (a time where she would have been twelve). More accurately, he blamed her for everything that had happened and the thing is, I don’t disagree with that critique entirely. However, this is a case of him being a bad person, not a bad character. This might seem like an odd distinction, but I think it changes the scope of deserved criticism.

As I’ve been trying so desperately to illustrate, Dimitri snapping wasn’t just because of Edelgard being revealed as the Flame Emperor. Rather, it was an unlucky combination of many things. His grasp and interpretation of reality were already hazy at best by the time she was unmasked, slowly falling apart as his prodromal symptoms worsened. Going into the fight, he believed the Flame Emperor to be responsible in whole or in part for the worst thing that had ever happened to him, guessed at Arundel’s involvement, had found (and lied about) the dagger, and was rapidly mentally deteriorating. While Dimitri suspected Edelgard’s involvement to some degree, he did his best to act like it wasn’t true.

Dimitri didn’t want it to be true. To the extent that he was willing to lie to Byleth (and to himself) to avoid reality. He cared deeply about Edelgard. The best year of his life was spent with her, she was his first love, and she was the daughter of the step-mother he adored. Strong feelings beget strong feelings, do they not? This reveal confronted Dimitri with something that he could not accept, so his mind sidestepped the issue altogether. Delusion convinced him that all of the fears and worries he had beforehand were related, all into one larger delusion that Edelgard had sole responsibility. It’s not right and maybe not even excusable, but it falls in line with everything else.

Edelgard and Dimitri. Bound by some twisted fate but forever doomed to be separated, unable to understand the other’s chosen path.

I do recognize the flaws of Dimitri’s character and arc. There are some pretty major flaws. I have parts of a post typed out about his shoddy recovery and how I’d fix it that, hopefully, one day will see the light of day as well as many complaints about the way the story is hindered by the need for flexibility to accommodate gameplay and a happy ending.

But, despite that, this has all been a very long-winded way of praising Dimitri’s writing. His mental illness has a surprising amount of depth and I loved studying it as intently as I did. I learned a lot about his character as well as about mental illness in general.

Ultimately, Dimitri is neither an innocent sweetheart whose actions are entirely excusable and justified or an unforgivable war criminal and overall terrible character. You can feel bad for his pain and his struggle with his illness and understand that as a reason for his actions, but you shouldn’t use it as justification. He had the opportunity to seek help before things got too bad. He was selfish with the mismanagement of his emotions and goals. However, he also was a victim. Dimitri worked to recover and mend the mistakes he made while he was unwell, which is a side of this mental illness that is rarely shown in media.

I wholeheartedly believe that, love him or hate him, Dimitri is the most well-written of the Three Houses characters,

#dimitri#fe dimitri#dimitri alexandre blaiddyd#fire emblem 16#fire emblem#FE3H#fire emblem three houses#i spent an ungodly amount of time on this feel free to share your thoughts

174 notes

·

View notes

Text

Michael in the Mainstream: The Chris Columbus Harry Potter Films

Here’s a bold stance to take these days: I actually still really love the Harry Potter franchise.

Yes, this series hasn’t had a huge impact on my own writing; my stories I’m working on draw far more from JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure and the Percy Jackson series than they do Harry Potter. And yes, the author of the franchise has outed herself as a transphobic scumbag whose every post-script addition to her franchise has been an unprecedented bad move (save, perhaps, for allowing Johnny Depp the opportunity to work during a very trying time in his life). But while the author is a horrendous person and the story hasn’t exactly given me as much to work with as other stories have, there are so many great themes, ideas, and characters that even now I’d still say this is one of my favorite series of all time. The world of Harry Potter is just so fascinating, the usage of folklore is interesting, and it has one of the most menacing and disturbing villains in young adult literature and manages to play the whole “love prevails over evil” cliché in such a way that it actually works.

And, of course, then we get into what I’m really here to talk about: the adaptations. The movies are not entirely better than the books; while I do think most of the films are on par with their novel counterparts, and they certainly do a good job of scrubbing out some of the iffier elements in Rowling’s writing, I still think there’s a certain, ahem, magic that the books have that gives them a slight edge. But, look, I’m a movie reviewer, and these films are some of my favorites of all time, and as much as I love the books I’m not going to sit around and say the books surpass them in every single way. There’s a lot to love in these films, and hopefully I’ll be able to convey that as I review the series.

Of course, the only place to truly start is the Chris Columbus duology. Columbus is not the most impressive director out there – this is the man who gave us Rent, Pixels, and that abominable adaptation of Percy Jackson after all – but early on in his career he made a name for himself directing whimsical classics such as the first two Home Alone movies and Mrs. Doubtfire. Those films are wonderfully cast and have a lot of charm, and thankfully this is the Columbus we got to bring us the first two entries in Harry’s story.

One of the greatest strengths of the first two Harry Potter movies is just the sheer, unrelenting magic and wonder they invoke. They’re so whimsical, so enchanting, so fun; they fully suck you into the world Rowling created and utilize every tool they can to keep you believing. Everything in these films serves to heighten the magic; practical effects and CGI come together with fantastic costuming and set design to make the world of wizards and Hogwarts school feel oh so real. And of course, none of this would be even remotely as effective if not for the legendary score by John Williams, who crafted some of the most iconic and memorable compositions of the 21st century for these films. In short: the tone of these films is pretty perfect for what they are, and every element in them works to make sure you are buying into this tone at every moment.

The other massively important element is the casting, and by god, the casting in these films is simply perfect. Of course, the title characters and his peers have to be unknowns, and thankfully they managed to pluck out some brilliant talent. I don’t need to tell you how good Daniel Radcliffe and Emma Watson are, even back in these films, but I do feel the need to say that Rupert Grint is vastly underappreciated; I really don’t think the films would work quite as well without his presence, because he does bring that goofy charm Harry’s friend group needs to balance it out. Matthew Lewis is the adorable coward Neville Longbottom and Tom Felton is the snotty brat Draco Malfoy, and though both of their roles are fairly minor in the first two films they manage to make their mark. The second movie pulls in Bonnie Wright as Ginny, and again, I’m gonna say she’s rather underrated; I think she did quite a fine job in her role.

But of course, the real draw of these films is the sheer amount of star power they have in terms of U.K. actors. You’ve got Maggie Smith (McGonagall), Robbie Coltrane (Hagrid), Warwick Davis (Flitwick and, bafflingly, only the voice of Griphook, who was played by the American Verne Troyer in the first film for… some reason), John Hurt (Ollivander), Toby Jones (Dobby), John Cleese (Nearly Headless Nick)… and this is only the first two films. The movies would continue pulling in stars like it was Smash Ultimate, determined to tell you that “EVERYONE IS HERE” and be the ultimate culmination of U.K. culture.

Of course, even in the first few movies there are those who truly stand out as perfect. Smith and Coltrane are most certainly the perfect embodiment of their characters, but I think a great deal of praise should be given to Richard Griffiths as Uncle Vernon; the man is a volatile, raging bastard the likes of which you rarely see, and he is at once repulsive and comical. He’s pretty much the British answer to J.K. Simmons as J. Jonah Jameson. Then we have Jason Isaacs as Lucius Malfoy in the second film, and he is just delightfully, deliciously devilish and dastardly. Isaacs actually came up with a lot of Mr. Malfoy’s quirks himself, such as the long blonde hair, the cane wand, and the part where he tries to murder a small child in cold blood for releasing his house elf (which came about because he forgot literally every other spell and had just read Goblet of Fire, so...). Then of course there is Kenneth Branagh as Gilderoy Lockhart, and… well, it’s Kenneth Branagh as Gilderoy Lockhart. I don’t think you could find a more perfect casting choice (except perhaps Hugh Grant, who was originally cast but had to drop out). He just really hams it up as the obnoxious blowhard and helps make him much more tolerable than his book counterpart, though he does unfortunately have the lack of plot relevance Lockhart did in the book, which is a problem unique to Lockhart. Fun fact, he is the ONLY Defence Against the Dark Arts teacher in the series to not ultimately matter in regards to the main story.

Of course, the greatest casting choice of them all is most certainly The late, great Alan Rickman as everyone’s favorite greasy potions professor, Severus Snape. I think Rickman goes a long way towards helping make Snape one of the greatest characters of all time, with everything about his performance just being perfect, and what makes it even better is how it would ultimately subvert his typical roles (though that’s a story for a different review). I don’t think either of the first films is really his best outing, butt he first one definitely sets him up splendidly. Snape barely has a role in the second film – something that greatly irritated Rickman during the movie’s production apparently – but he still does a good job with what limited screentime he has. Then we have Richard Harris as Dumbledore. Due to his untimely death, he only played Dumbledore in the first two films, but he really did give a wonderful performance that had all the charm, whimsy, and wonder the Dumbledore of the first few books was full of. The thing is, I don’t know if he would have been able to make the transition into the more serious and darker aspects of Dumbledore that popped up in the later books. I guess we’ll never know, which is truly a shame, but at the very least he gave us a good showing with what little time he had.

My only problems with the first two films are extremely minor, though there is at least one somewhat big issue I have. You see, while I do like everything about these films, I feel like they’re a bit too loyal to the books, not doing enough to distinguish themselves as their own thing like films such as Prisoner of Azkaban would do. But if I’m being honest, this is seriously nitpicky; it’s not like this really makes me think less of the films, because they have way more going for than against them. Stuff like this and the cornier early performances from the kid actors are to be expected when a franchise is still finding its legs. It really is more of a personal thing for me; I prefer when creators allow their own vision to affect an adaptation so that I can see how they perceive and interpret the work, but at the same time the first two Harry Potter books are all about setting up and the main plot doesn’t really kick off until the third and fourth books, so… I guess everything balances out?

It is a bit odd looking back at these first two films and noting how relatively self-contained they are compared to the denser films that were to come; you could much more easily jump into either one of these films and really get what’s going on compared to later movies, where you would almost definitely be lost if you tried to leap in without an inkling of the plot. But that is something I do like, since the first two films have really strong plots that focus more on the magical worldbuilding and developing the characters, setting up an incredibly strong foundation for the series to come. There are a few trims of the plot here and there, but it’s not nearly as major as some things that would end up cut later.

But, really, what’s there to cut? Like I said, these movies are more about the worldbuilding and setting up for later plotlines. They’re relatively simple stories here, and I think that’s kind of their big strengths, because it lets the characters and world shine through. The first film honestly is just Harry experiencing the wizarding world for the first time, with him going from scene to scene and just taking in all of the magical sights. Most of the big plot stuff really happens towards the end, when they make the journey down to the Philosopher’s Stone. The second movie is where things get a lot more plot-heavy, with the film focusing on the mystery of the Chamber of Secrets and all of the troubles that the basilisk within causes. Despite how grim the stories can get, especially the second one, these films never really lose that whimsical, adventurous tone, which is incredibly impressive all things considered.

It’s not really criticisms, but there are a few things that make me a bit sad didn’t happen in the first couple of films, or at the very least offer up some interesting “what could have been” scenarios. I think the most notable missed opportunity is the decision to axe Peeves, despite him being planned and having Rik Mayall film scenes with him only to have said scenes left on the cutting room floor, never to see the light of day; Mayall had some rather colorful words to say about the film after it came out. Sean Connery passing up on playing Dumbledore is another missed opportunity, but Connery has always been awful at picking roles and hates fantasy, so this isn’t shocking to me in the slightest. Terry Gilliam being straight-up told by Rowling she didn’t want him directing is another sad but necessary decision, as was Spielberg dropping out; neither guy would have been a very good fit for the franchise, honestly. Alan Cumming turning down the role of Lockhart because Grint and Watson were going to be paid more than him is a bit… lame, but also I don’t think he’d have been as good as Branagh in the role; as much as I love Cumming, Branagh has this grandiose stage actor hamminess that Lockhart desperately needs. There’s a lot of fascinating trivia facts I learned writing this review, and a lot of it paints some pretty weird pictures of how this franchise could have turned out in another world.