#divchato z lisa

Text

Efficiently Reading, Researching, and Approaching Academia

❈ Making Academic Texts Less Daunting ❈

One of the largest issues regarding accessibility in academic spaces is the daunting nature of a lot of academic works, whether they're books, dissertations, or articles. This is usually caused by academic jargon, nightmarishly long run-on sentences, and sometimes the writing is just plain dense.

This first lesson will be some tips and tricks for making reading academic texts more digestible!

First and foremost, getting to the point matters, understanding the theme, argument, thesis, what-have-you will make everything else make sense. In order to do this, you will want to read three things, that are usually signposted or labelled within a text: the abstract, the introduction, and the conclusion. This is also a good trick to get the gist of a text if you have to read in a rush and don't need to use citations.

What Do These Components Tell You?

❈ The Abstract - An abstract is basically a summary of the entire paper or text, this will tell you the thesis, maybe some points of data, and the conclusion reached by the author

❈ The Introduction - The introduction will provide a more detailed thesis and will detail what theories or interpretations are being used in the paper. In some cases they may also provide historic or cultural contexts for an argument or point.

❈ The Conclusion - The conclusion will provide the finishing points of the text, it will touch on key points of information or debate, explain what this thesis or proven point means for the understanding of the event, item, site, etc. that is being written about.

All in all, these three points in a text will give you an overview of the purpose of the text, and typically these sections don't get too heavily muddled down in academic lingo, which makes them more accessible to a broader base of readers. You don't always need a detailed understanding, sometimes just getting the point is enough.

Taking Notes

Whether you're reading something for applying it to your own writings or just to consume information, annotate the shit out of it. It doesn't matter if you're writing on a digital copy of the text, writing as you read on a separate notepad, or if you print out an article and write your notes on that. Just! Take! Notes!

The purpose of this is to help you process your thoughts, make note of what interests or confuses you, and, in the case that you are writing something that needs citations, prevents plagiarism. Use whatever format (color coding, highlighting, etc.) that works for you, what matters is the act of taking notes will encourage you to be an active reader rather than eventually falling into passive reading (if you notice yourself falling into this, take a break! Your brain needs rest.)

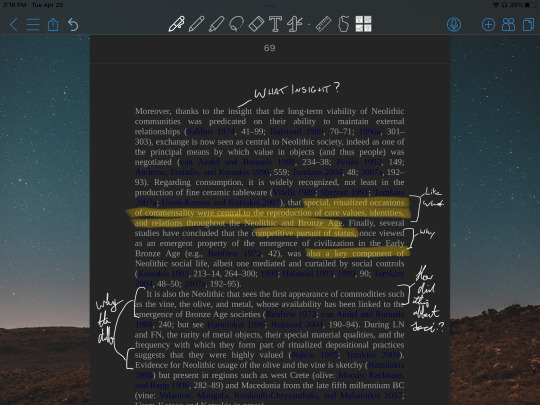

Here are two examples of how I take notes, one is for a chapter I had to read for a discussion, the other is how I take notes for papers and publications:

Discussion-focused notes in The Oxford Handbook for The Bronze Age Aegean

Information gathering notes for a paper on the Temple of Poseidon at Sounion, text used written in print at top

Finding Sources

There are many ways to find sources on a topic no matter the level of obscurity:

❈ Wikipedia - you really don't want to cite Wikipedia as a source, scrolling down to the sources/bibliography section at the bottom can give you a jumping off point. Usually full citations are given and sometimes the text/article in question is linked

❈ Google Scholar - I generally don't consider this the strongest search engine because it's difficult to narrow down by topic, discipline, etc. but it works in a pinch!

❈ JSTOR - A step above Google Scholar and it does allow stuff with a free membership, but you can also get further access with a paid membership or institutional access

❈ EBSCO - definitely has a learning curve but it has a large pool of information to pull from. The biggest downside is you usually can't download content. It has a different site for free content and content available for purchase or via institutional access.

❈ WorldCat - while it usually doesn't have the source itself accessible on the site, WorldCat will tell you where you can find what you're looking for and sometimes offers the ability to contact whoever is nearest to you that has the text

❈ Public Libraries - while public libraries are generally focused on non-research-based use, librarians are trained in research assistance and public libraries generally have access to inter-library loans (ILL) and can likely get books for you without needing you to travel far to get them

❈ Research Libraries - the biggest downside to many academic libraries is that you need to pay to access, however, if you can access them, they are typically more research-oriented than a public library and will often have specialists in certain subjects available to assist. An exception to the "paid" rule are usually state or federal libraries, such as the Library of Congress.

❈ Reaching Out To The Author Directly - with most journal publications, authors don't see a dime. If you can't pay for access, you can usually find the email of the author on an institution website and you can reach out to them there! It never hurts to ask.

Organizing Your Sources

Whether you have a stack of physical books, a long list of downloads, or links to sources, you’re going to want a way to organize them. Here are some ideas:

❈ Zotero - Zotero is a free app and browser extension that can file, organize, and even provide details about the sources you use. I really recommend this if you’re in an academic environment or need to cite sources a lot because one of its functions is that it will automatically cite sources and create bibliography in any format you choose. It functions both in the cloud and on a desktop/hard drive.

❈Google Drive - straightforward and simple to set up, all you have to do is upload files, organize them into as many folders as you please and go. However there are two downsides to Google Drive: They have a limit to the amount of storage you can use before you have to pay & if your sources are from a questionable site or may violate copyright, Google has the ability to remove those files permanently.

❈ CollaNote - CollaNote is a great, free app for storing notes and PDFs that also allows you to write on/annotate said files. It’s biggest downside is that it is iOS only and it’s cloud feature is kind of finicky.

❈ Discord - if you’re a professional Giant Nerd like me, having a personal discord server to sort and upload your sources is great! However, similar to Google Drive, there are file upload limits and Discord has the ability to remove material that violates copyright.

❈ OneNote - similar to CollaNote, OneNote allows you to upload PDFs so you can take notes on them and it is supported across devices. However, Microsoft office can be expensive to pay for.

❈ Your Trusty Computer/Flashdrive - There’s always the old fashioned route of storing your sources in folders on your hard or flash drive. Downside is flash drives are expensive and if your computer goes kaput, you will likely lose work. Make sure to have a cloud backup if you use this method!

Source Vetting

Sometimes vetting sources can be easy, other times it can be a massive pain for a range of reasons.

A good, general test to abide by is the CRAAP test:

Currency

Relevance

Authority

Accuracy

Purpose

A more detailed set of prompts to apply with the CRAAP test is available here: https://researchguides.njit.edu/evaluate/CRAAP

What If The CRAAP Test Doesn’t Work or I Don’t Know Have Enough Context for It To Work?

❈ Use Common Sense - does the information sound plausible? Does it make sense?

❈ Triangulate your Sources look at other sources regarding the topic. Do they say something similar? Do they acknowledge the information presented by the source you’re using?

❈ Investigate Credentials just having “PhD” at the end of a name does not a good source make. See what the author(s) credentials are. Are their credentials openly listed? Did they receive them from an accredited institution? Consider what group published the source. Was it a blog site or was it an academic publisher? Is the source peer reviewed or sent out as is?

❈ Look For Citations does the author or creator cite their information? Do they describe a body of work that they either gathered themselves or did research into? Are they transparent about their sources? Are they able to admit to gaps in their knowledge or accessible data or do they just fill it in?

8 notes

·

View notes