#corporate lobbying

Text

Been digging into things on Canadian/British, United States/British and South American/Spanish history recently and the notable thing that has come up on both - in all three cases, the European settlers were the ones actively engaging in genocide of the indigenous population. It was not the active policy of the European government.

In all three cases the European government actually passed protective legislation for the rights of indigenous subjects at the request of either indigenous people themselves travelling to Europe to make these representations, or not-entirely-awful Europeans passing on what was happening to them. They weren’t *incredible* protections in any of the three cases, but they at least recognised that indigenous people were *people* with actual basic rights. Like “not being automatically murdered or enslaved”.

But then European settlers went *batshit* at this legislation. The entire idea of “No Genocide” policies provoked enormous settler backlashes in all three cases. It was even a material, if not enormous, factor in why the US declared independence.

And the European governments in question just…rolled over. Made no real attempt to enforce this protective legislation. And it *certainly* was *not* why Britain sent in troops when the US declared independence. The Founding Fathers just viewed even the fact they had been *asked* to not murder indigenous people as an outrage.

None of this is to excuse European colonial states today of our responsibility to pay reparations and lobby for protections for indigenous people (and BIPOC in general) in our ex-colonial states. We’ve benefitted so much, especially on mass resource plundering, that reparations are a responsibility we cannot shirk.

(I just finished a biography of Charles Hapsburg and how he frittered away *massive* silver imports stolen from South America on European wars. That huge resource injection was pretty vital to the beginning of European international capitalism in the 16th-17th centuries. Before that, states just kept coming up against insufficient metals for currency, especially ones with the intermediate value of silver that let a critical mass of lower-level transactions happen.)

What it is, however, is an examination of the different ways states can be responsible for genocide, eugenics, and other crimes.

It does not need to be active policy for a state to be responsible. Even passing protective legislation doesn’t prevent a state’s responsibility if they don’t take measures to enforce that legislation, and, particularly, *if they give in to loud backlash from privileged parties who see it as an infringement of their privilege for people they are oppressing to be given some basic rights.*

I am not a proponent of “history repeats itself”. Context *always* matters, and every different situation has a different context. However, history itself provides an incredibly important and *necessary* context for situations we face now. And these facts are *incredibly* relevant to *many* situations we are currently facing.

#early modern history#colonialism#colonialist legacy#canadian history#us history#south american history#capitalist history#indigenous rights#indigenous people#spanish history#british history#nonenforcement of legislation makes it worse than useless#genocide#canadian genocide#south american genocide#american genocide#eugenics#corporate lobbying#privilege#settler colonialism#settler states#european history#european reparations#reparations

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

May 10th is the anniversary of the Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad Company Supreme Court decision of 1886. The case first established under the 14th Amendment that corporations are considered “persons.” The 14th Amendment granted citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the U.S, included former enslaved human beings, and provided all citizens with “equal protection” and other rights under the law. It was not intended to apply to corporations.

The Supreme Court granted corporations other constitutional rights since then, including the 4th Amendment search and seizure rights, 5th Amendment takings rights and 1st Amendment free speech rights to spend money corrupting politics. The 2010 Citizens United decision expanded corporate 1st Amendment free speech rights.

It’s a common belief that the corporations first acquired corporate constitutional rights (“corporate personhood”) in the Citizen United decision. They did not. Corporate power to hijack democracy precedes Citizens United and corporate spending money in elections by nearly a century.

Armed with constitutional rights, corporations have “railroaded” people, communities and elected officials – overturning democratically-passed laws ensuring safe food and products, protecting workers and workplaces, and ensuring a livable world – in ways that have nothing to do with Citizens United or corporate “free speech” rights.

Ending ALL corporate constitutional rights – not just overturning Citizens United and corporate “free speech” rights – is what makes Move to Amend unique. It is why we call for enactment of the We the People Amendment. And it is why May 10 is such a very important date.

#us politics#citizens united#Santa Clara County v Southern Pacific Railroad Company#14th amendment#corporate lobbying#corporate greed#Corporate personhood#may 10th

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

For many cooks, waiters and bartenders, it is an annoying entrance fee to the food-service business: Before starting a new job, they pay around $15 to a company called ServSafe for an online class in food safety.

That course is basic, with lessons like “bathe daily” and “strawberries aren’t supposed to be white and fuzzy, that’s mold.” In four of the largest states, this kind of training is required by law, and it is taken by workers nationwide.

But in taking the class, the workers — largely unbeknown to them — are also helping to fund a nationwide lobbying campaign to keep their own wages from increasing.

The company they are paying, ServSafe, doubles as a fund-raising arm of the National Restaurant Association — the largest lobbying group for the food-service industry, claiming to represent more than 500,000 restaurant businesses. The association has spent decades fighting increases to the minimum wage at the federal and state levels, as well as the subminimum wage paid to tipped workers like waiters.

The federal minimum wage has risen just once since 1996, to $7.25 from $5.15, while the minimum hourly wage for tipped workers has been $2.13 since 1991. Minimums are higher in many states, but still below what labor groups consider a living wage.

For years, the restaurant association and its affiliates have used ServSafe to create an arrangement with few parallels in Washington, where labor unwittingly helps to pay for management’s lobbying. First, in 2007, the restaurant owners took control of a training business. Then they helped lobby states to mandate the kind of training they already provided — producing a flood of paying customers.

More than 3.6 million workers have taken this training, providing about $25 million in revenue to the restaurant industry’s lobbying arm since 2010. That was more than the National Restaurant Association spent on lobbying in the same period, according to filings with the Internal Revenue Service.

That $25 million represented about 2% of the National Restaurant Association’s total revenues over that same period, but more than half of the amount its members paid in dues. Most industry groups are much more reliant on big-dollar donors or membership support to meet their expenses. Most of the association’s revenues come from trade shows and other classes.

Tax-law experts say this arrangement, which has helped fuel a resurgence in the political influence of restaurants, appears legal.

But activists for raising minimum wages — and even some restaurant owners — say the arrangement is hidden from the workers it relies on.

“I’m sitting up here working hard, paying this money so that I can work this job, so I can provide for my family,” said Mysheka Ronquillo, 40, a line cook who works at a Carl’s Jr. hamburger restaurant and at a private school cafeteria in Westchester, Calif. “And I’m giving y’all money so y’all can go against me?”

Ms. Ronquillo is also a labor organizer in California. She said that she had taken the class every three years, as required, and that she never knew ServSafe funded the other side of that fight.

As workers have become more aware of how their payments to ServSafe are used, something of a backlash is developing. Looking ahead to coming battles over minimum wages in as many as nine states run by Democrats, including New York, Saru Jayaraman of the labor-advocacy group One Fair Wage said she was encouraging workers to avoid ServSafe.

“We’ll be telling them to use any possible alternatives,” Ms. Jayaraman said.

The kind of class that these workers pay for, called “food handler” training, is offered by ServSafe or its affiliates in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. But an online database maintained by the National Restaurant Association show the vast majority of its classes are taken in four large states where food-handler classes are mandatory for most workers: Texas, California, Illinois and Florida.

Other companies also offer this training. But restaurant industry veterans say that ServSafe is the dominant force in the market — to the point that some restaurant owners said they did not realize there were alternatives.

“ServSafe is very much the Kleenex” of the industry — a brand that defines the business, said Nick Eastwood, who runs a competitor called Always Food Safe. “We believe they’ve got at least 70%+ of the market. Maybe higher.”

The president of the National Restaurant Association, Michelle Korsmo, declined to be interviewed. In a written statement, she said the group had sought to protect both public health and the financial health of the industry.

“The association’s advocacy work keeps restaurants open; it keeps workers employed, it finds pathways for worker opportunity, and it keeps our communities healthy,” Ms. Korsmo wrote. Her group declined to say how much of the training market it captures.

As money flowed in from the National Restaurant Association’s training programs, its overall spending on politics and lobbying more than doubled from 2007 to 2021, tax filings show. The national association donated to Democrats, Republicans and conservative-leaning think tanks, and sent hundreds of thousands of dollars to state restaurant associations to beef up their lobbying.

During the Clinton and Obama administrations, the association was a major force in limiting employer-provided health care benefits. And though pressure from liberal groups has grown and workers’ wages have fallen for decades when adjusted for inflation, the group helped assemble enough bipartisan opposition to scuttle a bill in 2021 to raise the federal minimum wage for all workers to $15 per hour over five years.

The association had also won a series of battles over state-level wage minimums, though its fortunes reversed last year. Both the District of Columbia and Michigan moved to eliminate the “tip credit” system — where restaurants are allowed to pay waiters a salary below the minimum wage, on the expectation that tips from customers will make up the rest. That was the first time any state had eliminated the tip-credit system in more than 10 years.

Legally, the National Restaurant Association and its state-level affiliates are a species of nonprofit called a “business league,” with more freedom to lobby than a traditional charity.

Since the 1960s, their lobbying has focused heavily on the minimum wage — arguing that labor-intensive operations like restaurants, which employ more workers at or near the minimum wage than any other industry, could be put out of business by any significant increase in employee costs.

Fifteen years ago, they had just lost a battle in that fight.

Over the association’s objections, Congress had raised the minimum wage to $7.25 an hour. Former board members said they were searching for a new source of revenue — without asking members to pay more in dues.

“That’s when the decision was contemplated, of buying the ServSafe program,” said Burton “Skip” Sack, a former chairman of the association’s board. “Because it was profitable.”

At the time, the ServSafe program was run by a charity affiliated with the restaurant association. The association bought the operation, transforming it into an indirect fund-raising vehicle.

After that, state restaurant associations in California, Texas and Illinois lobbied for changes in state law.

Previously, those states had required food-safety training for restaurant managers, which typically was paid for by restaurants themselves. After the association’s takeover of ServSafe, lobbying records show, the state affiliates pushed for a broader and less-common type of mandate, covering all food “handlers” like cooks, waiters, bartenders and those who bus tables.

The three state legislatures agreed, in lopsided votes.

In written statements, the state restaurant associations said they were not trying to raise money. Instead, they said they worked with other groups seeking to reduce food-borne disease.

“This law was happening with or without our participation in the process,” said the president of the California Restaurant Association, Jot Condie. California legislative records show his association was the sponsor of the bill that imposed the mandate.

ServSafe soon had waves of new customers, which in turn generated more money for the association and its lobbying efforts. Today, Florida, California, Texas, Illinois and Utah all have similar requirements. John Bluemke, a senior vice president for sales at ServSafe from 2002 to 2010, said there was little need to pursue mandates in smaller states: “Once you did the big states, who cares about Nebraska?”

“If you’ve got a million people going through that thing, do the math,” Mr. Bluemke said. The National Restaurant Association does not release figures about the cost of offering food-handler classes, but Mr. Bluemke said that — because they are generally offered online — the costs are low and the profits high.

“We always said the first course costs you a million dollars,” Mr. Bluemke said, for making the video. “And the rest are free.”

When managers take mandatory training, restaurant veterans say, the employer usually pays. But state websites say that restaurant employees should expect to pay for these classes themselves, and restaurant workers interviewed by The New York Times said that was their experience.

The restaurant association notes that some employers have covered the costs of getting certified and that employees are given lower rates in certain circumstances. So not all 3.6 million workers paid $15 each.

“The N.R.A. is different from most traditional trade associations in our business model,” Dawn Sweeney, the National Restaurant Association’s chief executive at the time, wrote to members in 2014 — reminding them of what a good deal they had.

Business leagues, which are tax-exempt, are generally allowed to run a for-profit business, as long as it advances the common interest of their broader trade. The National Restaurant Association contends that its business cleanly fits this standard.

“The rules the I.R.S. has passed are not always clear as to what is and is not allowed,” said Anna Massoglia, an investigations manager at OpenSecrets, a nonpartisan group that tracks the flow of money in politics. “This makes it easier for groups to exploit that lack of clarity. I’m not familiar with another group that has done it to this scale.”

The Internal Revenue Service declined to comment, citing taxpayer-privacy rules.

For restaurant workers, there is little clue that money paid to ServSafe supports lobbying — much less lobbying that tries to keep workers’ pay low. The only hint is a line on ServSafe’s website, saying it “reinvests proceeds from programs back into the industry.”

Even some members of the restaurant association — the beneficiaries of this arrangement — said they did not know how it worked.

Johnny Martinez, a Georgia restaurateur, said he supports a $15 minimum wage and pays at least that much in a state where it is still $7.25 per hour. And he describes his association membership as “the price of entry” for navigating the industry, “even though I disagree with them on a lot of things.”

But he expressed frustration upon discovering the connections between ServSafe and lobbying efforts, saying “it feels very wrong” to him.

“This is a certification that’s also wrapped up inside of a lobbyist,” Mr. Martinez said. “It is weird that the tests that they require the workers to pay for are being run by the same company that’s fighting to make sure those people don’t make more money.”

#us politics#news#2023#the new york times#food service industry#worker's rights#workers#working class#ServSafe#National Restaurant Association#lobbyists#corporate lobbying#corporate lobbyists#wages#raise the minimum wage#poverty wages#minimum wage#living wage#One Fair Wage#internal revenue service#texas#California#Florida#illinois#Always Food Safe#utah#California Restaurant Association#Business leagues

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

More than 600 communities across the U.S. have decided to build their own broadband networks after decades of predatory behavior, slow speeds, and high prices by regional telecom monopolies.

That includes the city of Bountiful, Utah, which earlier this year voted to build a $48 million fiber network to deliver affordable, gigabit broadband to every business and residence in the city. The network is to be open access, meaning that multiple competitors can come in and compete on shared central infrastructure, driving down prices for locals (see our recent Copia study on this concept).

As you might expect, regional telecom monopolies hate this sort of thing. But because these networks are so popular among consumers, they’re generally afraid to speak out against them directly. So they usually employ the help of dodgy proxy lobbying and policy middlemen, who’ll then set upon any town or city contemplating such a network using a bunch of scary, misleading rhetoric.

Like in Bountiful, where the “Utah Taxpayers Association” (which has direct financial and even obvious managerial tethers to regional telecom giants CenturyLink (now Lumen) and Comcast) launched a petition trying to force a public vote on the $48 million in revenue bonds authorized for the project under the pretense that such a project would be an unmitigated disaster for the town. (Their effort didn’t work).

Big ISPs like to pretend they’re suddenly concerned about taxpayers and force entirely new votes on these kinds of projects because they know that with unlimited marketing budgets, they can usually flood less well funded towns or cities with misleading PR to sour the public on the idea.

But after the experience most Americans had with their existing broadband options during the peak COVID home education boom, it’s been much harder for telecom giants to bullshit the public. And the stone cold fact remains: these locally owned networks that wouldn’t even be considered if locals were happy with existing options.

You’ll notice these “taxpayer groups” exploited by big ISPs never criticize the untold billions federal and local governments throw at giant telecom monopolies for half-completed networks. Or the routine taxpayer fraud companies like AT&T, Frontier, CenturyLink (now Lumen) and others routinely engage in.

And it’s because such taxpayer protection groups are effectively industry-funded performance art; perhaps well intentioned at one point, but routinely hijacked, paid, and used as a prop by telecom monopolies looking to protect market dominance.

Gigi Sohn (who you’ll recall just had her nomination to the FCC scuttled by a sleazy telecom monopoly smear campaign) has shifted her focus heavily toward advocating for locally-owned, creative alternatives to telecom monopoly power. And in an op-ed to local Utah residents in the Salt Lake Tribune, she notes how telecom giants want to have their cake and eat it too.

They don’t want to provide affordable, evenly available next-generation broadband. But they don’t want long-neglected locals to, either:

Two huge cable and broadband companies, Comcast and CenturyLink/Lumen, have been members of UTA and have sponsored the UTA annual conference. They have been vocally opposed to community-owned broadband for decades and are well-known for providing organizations like the UTA with significant financial support in exchange for pushing policies that help maintain their market dominance. Yet when given the opportunity in 2020, before anyone else, to provide Bountiful City with affordable and robust broadband, the companies balked. So the dominant cable companies not only don’t want to provide the service Bountiful City needs, they also want to block others from doing so.

Big telecom giants like AT&T and Comcast (and all the consultants, think tankers, and academics they hire to defend their monopoly power) love to claim that community owned broadband networks are some kind of inherent boondoggle. But they’re just another business plan, dependent on the quality of the proposal and the individuals involved.

Even then, data consistently shows that community-owned broadband networks (whether municipal, cooperative, or built on the back of the city-owned utility) provide better, faster, cheaper service than regional monopolies. Such networks routinely not only provide the fastest service in the country, they do so while being immensely popular among consumers. They’re locally-owned and staffed, so they’re more accountable to locals. And they’re just looking to break even, not make a killing.

If I was a lumbering, apathetic, telecom monopoly solely fixated on cutting corners and raising rates to please myopic Wall Street investors, I’d be worried too.

#article#telecommunications#AT&T#comcast#monopoly#internet#municipal governments#municipal internet#CenturyLink#corporate lobbying#wall street

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

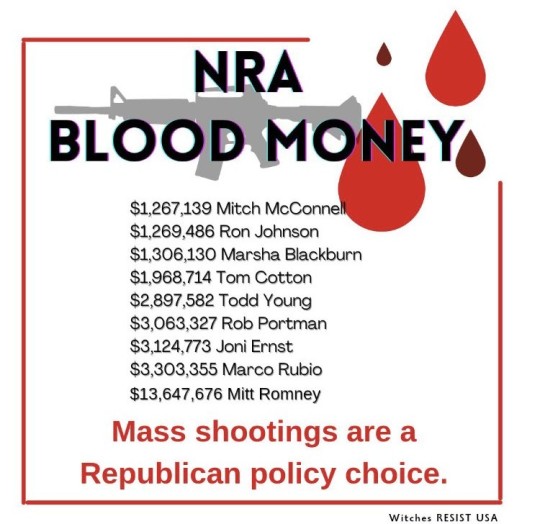

#us politics#nra#national rifle association#blood money#corporate lobbying#lobbyists#get money out of politics#sen. mitch mcconnell#sen. ron johnson#sen. marsha blackburn#sen. tom cotton#Sen. rob Portman#sen. joni ernst#sen. marco rubio#sen. mitt romney#gop#conservatives#Republicans#2022

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

100,000 dollars is not a lot of money.

it is also a lot more money than i will ever have. my student loans make up half of that - they're coming back, i'm told, like we all bounced back recently. the other day while paying for gas to go to work, i overdrew my account without knowing it.

i sat in the car and looked at the charge and tried to do the math. where the fuck is the money even going? i don't live extravagantly. i live in a hole in the ground, in an apartment the size of a sneeze; covered in ants. yes, i wanted to live close to a population center. maybe that's my fault. i've downloaded the apps and i've spoken to the experts and i've cut back on excess. i can't help the pharmacy bills or the medical debt.

i have a good, well-paying job. when i googled it to see if i was getting a fair salary, i found out i'd be making "upper middle class" money. which doesn't make sense - is "upper middle class" now just "able to afford a one-bedroom without a roommate". when i was younger, upper-middle meant a nice big house and a backyard and vacations and not flinching about eating at a resturant.

i was talking to my friend who is a realtor. he said 100,000 dollars is extremely cheap for housing. he's not wrong. 100,000 dollars would change my life. 100,000 dollars also won't really buy you anything. it could get you out of debt, potentially, if you were lucky and had a certain amount of scholarships to tack onto your degree. you could pay off the car and then have enough left over for "spending" money. how fucking amazing. one vacation, maybe two if you're thrifty. and then - like magic - the money would evaporate into nothing. people would sigh and tell you see, you should have put it into savings! like "upper middle class" people can't afford to value "actually living" over squirrelling wealth. you should spend your life only in scarcity. like that is what made the rich people all their real "actually a lot of money".

100,000 dollars would literally set me free. it also would just set me back to "earning normally" instead of paying down debt into infinity. god, do you know how many of us just want that? that our first thought is we could stop scrambling and just be free of debt if we won the lottery? that we don't even necessarily need to stop working - we just wouldn't have to worry about failing or falling?

and. at the same time. 100,000 dollars is next to fucking nothing.

#writeblr#me paying my taxes this year:#haha good to know im literally doing more for my community out of my tiny apartment#than most corporations will do in their entire scope! :) these motherfuckers will NEVER pay taxes!!!#bc they lobby others to be sure we CHOKE :) !!!#i hope this is clear like. this isn't someone being like ''haha if i got 100k it wouldn't be a big deal''#it's more like. the gap between corporations and the ppl WORKING in those corporations#has become HORRIFIC. 100k to the company i work for is like. pocket change to them.#and it is LIFE CHANGING for me.#they could cut me a check for 100k tomorrow and not even budge their margin of error

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Eva Menz: Inception, Corporate Lobby (2017) Located: Geneva, Switzerland

#Eva Menz#Inception#Corporate Lobby#sculpture#stairs#interior design#interiors#Geneva#switzerland#2017

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

It's been a long day at work...

(Hi Chip enjoyers come get your food.)

#toontown#corporate clash#ttcc#chainsaw consultant#chip revvington#fanart#art tag#toonblr#toon tag#i imagine the context for this is everyone else has gone home from work#chip's just hanging in the lobby. contemplating his life choices

345 notes

·

View notes

Text

#mass shootings#school shootings#the nra is a terrorist organization#assault weapons ban#2nd amendment assholes#gun lobby bribes#nra bribes#gun control#gun violence#republican assholes#traitor trump#crooked donald#republican party#corporate greed#Republican greed#never trump#greed before children

194 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

How the Corporate Takeover of American Politics Began

The corporate takeover of American politics started with a man and a memo you've probably never heard of.

In 1971, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce asked Lewis Powell, a corporate attorney who would go on to become a Supreme Court justice, to draft a memo on the state of the country.

Powell’s memo argued that the American economic system was “under broad attack” from consumer, labor, and environmental groups.

In reality, these groups were doing nothing more than enforcing the implicit social contract that had emerged at the end of the Second World War. They wanted to ensure corporations were responsive to all their stakeholders — workers, consumers, and the environment — not just their shareholders.

But Powell and the Chamber saw it differently. In his memo, Powell urged businesses to mobilize for political combat, and stressed that the critical ingredients for success were joint organizing and funding.

The Chamber distributed the memo to leading CEOs, large businesses, and trade associations — hoping to persuade them that Big Business could dominate American politics in ways not seen since the Gilded Age.

It worked.

The Chamber’s call for a business crusade birthed a new corporate-political industry practically overnight. Tens of thousands of corporate lobbyists and political operatives descended on Washington and state capitals across the country.

I should know — I saw it happen with my own eyes.

In 1976, I worked at the Federal Trade Commission. Jimmy Carter had appointed consumer advocates to battle big corporations that for years had been deluding or injuring consumers.

Yet almost everything we initiated at the FTC was met by unexpectedly fierce political resistance from Congress. At one point, when we began examining advertising directed at children, Congress stopped funding the agency altogether, shutting it down for weeks.

I was dumbfounded. What had happened?

In three words, The Powell Memo.

Lobbyists and their allies in Congress, and eventually the Reagan administration, worked to defang agencies like the FTC — and to staff them with officials who would overlook corporate misbehavior.

Their influence led the FTC to stop seriously enforcing antitrust laws — among other things — allowing massive corporations to merge and concentrate their power even further.

Washington was transformed from a sleepy government town into a glittering center of corporate America — replete with elegant office buildings, fancy restaurants, and five-star hotels.

Meanwhile, Justice Lewis Powell used the Court to chip away at restrictions on corporate power in politics. His opinions in the 1970s and 80s laid the foundation for corporations to claim free speech rights in the form of financial contributions to political campaigns.

Put another way — without Lewis Powell, there would probably be no Citizens United — the case that threw out limits on corporate campaign spending as a violation of the “free speech” of corporations.

These actions have transformed our political system. Corporate money supports platoons of lawyers, often outgunning any state or federal attorneys who dare to stand in their way. Lobbying has become a $3.7 billion dollar industry.

Corporations regularly outspend labor unions and public interest groups during election years. And too many politicians in Washington represent the interests of corporations — not their constituents. As a result, corporate taxes have been cut, loopholes widened, and regulations gutted.

Corporate consolidation has also given companies unprecedented market power, allowing them to raise prices on everything from baby formula to gasoline. Their profits have jumped into the stratosphere — the highest in 70 years.

But despite the success of the Powell Memo, Big Business has not yet won. The people are beginning to fight back.

First, antitrust is making a comeback. Both at the Federal Trade Commission and the Justice Department we’re seeing a new willingness to take on corporate power.

Second, working people are standing up. Across the country workers are unionizing at a faster rate than we’ve seen in decades — including at some of the biggest corporations in the world — and they’re winning.

Third, campaign finance reform is within reach. Millions of Americans are intent on limiting corporate money in politics – and politicians are starting to listen.

All of these tell me that now is our best opportunity in decades to take on corporate power — at the ballot box, in the workplace, and in Washington.

Let’s get it done.

#youtube#videos#video#powell memo#corporations#wall street#finance#corruption#politics#lobbying#government

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Merry Christmas TTCC nerds!! 🎄✨️💕

#i know this is late... i posted these on Christmas on twitter tho!#whats a good silly holiday pic without POG?#the secretary bird cog is and OC of mine named Ter Byrd#hes a secretary for a paper + office supply company#he and Benjamin are friends and met when Benjamin was accidentally trapped in a meeting of office men in a hotel lobby#ttcc#toontown corporate clash#toontown#toontown: corporate clash#oc#au#ttcc au#pacesetter#graham ness payser#benjamin biggs#bellringer#kilo kidd#scapegoat

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Becoming increasingly convinced that high-speed rail might be the only economically viable (megacorp and politicapitalism friendly…) thing that can drastically lower the cost of living for everyone while additionally massively increasing general economic gains and aide in scientific and knowledge seeking innovations.

Between high speed rail, nuclear energy, and hydrogen development, we would could seriously launch this planet into the future at breakneck speeds.

#not that it took much convincing#politicapitalism#(is that a word? it should be#the cross between corporate lobbying and politics)#high speed rail#trains#megacorp#nuclear energy#hydrogen#mine#that it#it would solve so many social issues by spreading and connecting the populace over large areas

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

A beef industry group is running a campaign to influence science teachers and other educators in the US. Over the past eight years, the American Farm Bureau Foundation for Agriculture (AFBFA) has produced industry-backed lesson plans, learning resources, in-person events, and webinars as part of a program to boost the cattle industry’s reputation.

Beef has one of the highest carbon footprints of any food, but AFBFA funding documents reveal that the industry fears that science teachers are exposed to “misinformation,” “propaganda,” and “one-sided or inaccurate” information. The campaign from the AFBFA—a farming-industry-backed group that "educates" Americans about agriculture—is an attempt to fight back and leave school teachers with a “more positive perception” of the beef industry, the funding documents reveal.

According to survey data included in these documents, educators who attended at least one of the AFBFA’s programs were 8 percent more likely to trust positive statements about the beef industry. Some 82 percent of educators who participated in a program had a positive perception of how cattle are raised, and 85 percent believed that the beef industry is “very important” to society.

The beef industry “knows it has a trust issue,” says Jennifer Jacquet, a professor of environmental science and policy at the University of Miami. The industry is attempting to influence public opinion by starting with children, says Jan Dutkiewicz at the Pratt Institute’s Department of Social Science and Cultural Studies. Dutkiewicz points out that one of the AFBFA’s objectives outlined in its most recent funding document is to run events that “engage educators and students … to increase their understanding and positive perceptions of the beef industry.”

...

The AFBFA is a contractor to Beef Checkoff, a US-wide program in which beef producers and importers pay a per-animal fee that funds programs to boost beef demand in the US and abroad. In 2024, Beef Checkoff has approximately $42 million to disperse across its initiatives, and a funding request reveals that the AFBFA’s campaign for 2024 is projected to cost $800,000. The allocation of Beef Checkoff funding to programs like this is approved by members of the Cattlemen’s Beef Board and the Federation of State Beef Councils, two groups that represent the cattle industry in the US.

One lesson plan provided as part of the program directs students to beef industry resources to help devise a school menu. In another lesson plan students are directed to create a presentation for a conservation agency regarding the introduction of cattle into their ecological preserve. A worksheet aimed at younger students has them practice their sums by adding up the acreage of cow pastures. Another worksheet based around a bingo game aimed at 8- to 11-year-olds asks teachers to “remind students that lean beef is a nutritions source of protein that can be incorporated in daily meals.”

Science teachers in many states are currently updating their lessons to incorporate the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS)—a set of teaching guidelines that encourage educators to place more emphasis on how science is used in the real world. AFBFA funding documents show that the foundation intends to use the adoption of the NGSS as an opportunity to provide teachers with learning materials that relate to the beef industry.

“Furthermore, NGSS requires teachers to approach challenging topics such as climate change and sustainability,” reads an AFBFA funding authorization request for its education program. It continues: “Teachers and students are receiving information from educationally trusted sources that do not represent agriculture accurately or in a balanced way, and beef production is often the target of "misinformation". To achieve balance and to ensure the accuracy of information, a concerted effort must be made to engage teachers in the conversation around these topics.”

Dutkiewicz says that food production should be taught in US schools but that industry-funded material is unlikely to provide objective information about the impact of beef production. “I worry that clearly partial resources that are strategically designed to achieve a corporate messaging are being provided by a Checkoff program,” he says.

#enviromentalism#ecology#Beef industry#cattle#livestock industry#meat industry#livestock#lobbyists#corporate lobbying#American farm Bureau Foundation for agriculture#AFBFA#Cattle industry#Cattlemen Beef Board#Beef lobby

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why is a billionaire-funded super PAC aligned with Republican Rep. Kevin McCarthy playing a role in talks over who will become the next Speaker of the House?

Democratic lawmakers and campaign finance watchdogs raised that question Wednesday after the Congressional Leadership Fund (CLF) and the Club for Growth—another right-wing organization bankrolled by billionaires—announced a deal under which CLF won't spend any money on "open-seat primaries in safe Republican districts," a key demand of McCarthy opponents who felt their preferred candidates have been snubbed by the deep-pocketed super PAC.

As Fortune reported Wednesday, "far-right lawmakers have complained that their preferred candidates for the House were being treated unfairly as the campaign fund put its resources elsewhere."

CLF spent nearly $260 million during the 2022 election cycle, including millions to help reelect Republicans who are trying to tank his speakership bid. The super PAC's top donors in the midterm cycle were banking scion Timothy Mellon, Blackstone CEO Stephen Schwarzman, and Citadel CEO Kenneth Griffin—all billionaires.

The deal between CLF and Club for Growth came as McCarthy continued his frantic efforts to cobble together the necessary 218 votes, offering a number of concessions to Republicans who have rejected the California lawmaker in six consecutive votes—and possibly more on Thursday.

Sen. Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) was among those who raised concerns over CLF and Club for Growth's role in the ongoing Speakership debacle.

"It is creepy that dark money super PACs are explicitly part of the negotiation regarding who becomes Speaker of the United States House," the Senator wrote on Twitter.

Federal law prohibits candidates from coordinating with super PACs, though the independence mandate is often flouted in practice. In a press release, CLF and Club for Growth insisted that "no one in Congress or their staff has directed or suggested CLF take any action here."

"Interesting that an independent super PAC that isn't supposed to coordinate with members of Congress comes to an agreement to benefit a specific member of Congress," responded Adam Smith, action fund director of End Citizens United.

Club for Growth, which bills itself as a "leading free-enterprise advocacy group" that promotes tax cuts and deregulation, originally opposed McCarthy's run for Speaker, pushing him to agree to a number of concessions backed by far-right House Republicans.

But the organization, which has received funding from the Koch network and other right-wing forces, suggested Wednesday that it will support McCarthy if he upholds the concessions he has offered thus far.

"This agreement on super PACs fulfills a major concern we have pressed for," Club for Growth president David McIntosh said in a statement.

While the CLF-Club for Growth agreement was seen as a major victory for the anti-McCarthy faction, it's not clear whether it will be enough to end the impasse. The House is set to convene again Thursday at noon.

Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.), a member of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, argued in a tweet Wednesday that "these types of shady, backroom deals—which indebt our lawmakers to corporations and special interests—are corrupting our democracy."

"This is why I started the bipartisan Congressional No PAC caucus and have never taken PAC money, and refuse to start," Khanna added.

#us politics#news#common dreams#2023#118th congress#us house of representatives#speaker of the house#super pacs#Congressional Leadership Fund#Club for Growth#corporate lobbying#lobbying#Timothy Mellon#Stephen Schwarzman#Kenneth Griffin#billionaires#fuck billionaires#Sen. Brian Schatz#dark money#Adam Smith#end citizens united#David McIntosh#Rep. Ro Khanna#Congressional No PAC caucus#congressional progressive caucus#punchbowl news#Jacqueline Alemany

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

I knew High Roller was capable of a lot of unexplainable stuff.. but this is a new one.

- 🦝

#toontown#toontown corporate clash#ttcc#toonblr#corporate clash#cogs#toontastic toons#sparrowatheartoc#sparrowatheartgames#High Roller#jj trickyfluff#Into the Void apparently?#Just tried to sit on the couch in the lobby

41 notes

·

View notes

Video

Corporate takeover of the US

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lewis_F._Powell_Jr.

#tiktok#Lewis f powell#powell memo#citizen's united#us supreme court#capitalism is a scam#labor movements#labor movement#advertising#reagan was a terrible president#ronald reagan#reagan#FTC#anti-trust laws#corporate greed#corporate welfare#us political lobbying#us political financing#robert reich#us elections#workers rights#workers vs capital#union workers#price gouging#taxes#history#american history

299 notes

·

View notes