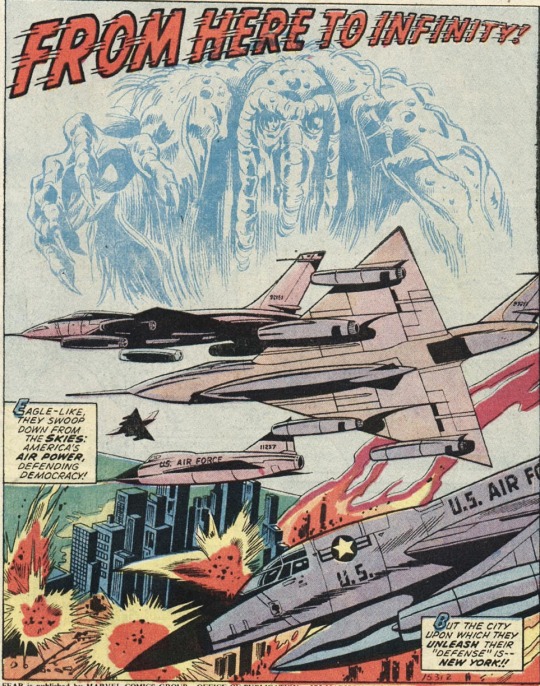

#considering how anti-military industrial complex the first story with Man-Thing is this isn’t what I expected when I opened the issue haha

Text

“From Here to Infinity!” Fear (Vol. 1/1970), #15.

Writer: Steve Gerber; Penciler: Val Mayerik; Inker: Frank McLaughlin; Colorist: Petra Goldberg; Letterer: Artie Simek

#Marvel#Marvel comics#Marvel 616#Man-Thing#Ted Sallis#considering how anti-military industrial complex the first story with Man-Thing is this isn’t what I expected when I opened the issue haha#I mean I guess this still tracks as this indicative of how in a world gone mad (as is the case with this issue)#one of the first things a government will use its fancy new tech for is attacking its own citizens but STILL#wasn’t expecting uuuuuuh *squints* the wings say F-15 but the nose says MiG-23??? I mean this issue’s a little early for the F-16#forgive me unfortunately late 20th century materiel is not my forte

0 notes

Link

Piers Morgan is a bully. From beefing with Lady Gaga over the veracity of her trauma to attacking gender-neutral clothing as a concept, Morgan has a reputation. That's why it might be no surprise that he got called out (again) on a live broadcast of Good Morning Britainfeaturing a panel discussing protests against President Donald Trump in the United Kingdom.

Ash Sarkar, a senior editor at Novara Media, was on that panel and ended up in an argument with Morgan that went viral. Morgan challenged her over her willingness to protest Trump by accusing her of not protesting former president Barack Obama. That sparked a shouting match heard 'round the Internet.

Challenged about deportation figures under the Obama administration, Sarkar said she did have a problem with the 44th president's immigration polices. But Morgan wasn't hearing any of it. Morgan repeatedly asked Sarkar where her Obama protests had taken place, speaking over Sarkar's efforts to answer. After Morgan's cohost, Susanna Reid, pointed out that you don't have to take to the streets over every issue, Morgan again refused to let Sarkar explain the work she had done to protest Obama's policies, calling Obama her "hero."

"He's not my hero," Sarkar replied. "I'm a communist, you idiot."

"Have you ever considered chairing a debate without straw-manning your guests, Piers, to make up for your own incompetence?" Sarkar continued after Morgan claimed there were zero protests against Obama's U.K. visits. (Morgan was wrong about that.) When Morgan again labeled her "pro-Obama," Sarkar responded, "I'm not pro-Obama. I've been critic of Obama. I'm a critic of the Democratic Party because I'm literally a communist."

Sarkar spoke with Teen Vogue about that moment with Morgan and what being a literal communist means when you're talking about U.S. presidents past and future.

Teen Vogue:

You were on Good Morning Britain to discuss Trump protests in the U.K. How did those demonstrations go?

Ash Sarkar:

There were at least 250,000 [people] at the Together Against Trump March yesterday, which makes it the biggest weekday protest in British history, and the biggest protest since the one in 2003 against the Iraq War.

It was a real mix of people. It was lots of young people, which might have been their first protest. Others were recognizable activists from anti-arms trade campaigns or Palestinian solidarity campaigns, so it put together a diverse range of political experiences.

Teen Vogue:

Have you seen an increase in youth activism in the U.K.?

Ash Sarkar:

Yes, certainly. I think that since 2010 especially, when there was a revived student movement, there has been a sense that street protest belongs to the young, and that's a really productive avenue of political expression.

I would think that when you put [on] something like an anti-Trump march, it's about a statement of values, right? And trying to define who you are through a rejection of the values that you find completely abhorrent. It's about defining yourself as the anti-Trump: being welcoming, outward-looking, and anti-racist.

Teen Vogue:

So can we talk about Piers a little bit?

Ash Sarkar:

Oh, yeah. A bellicose walrus himself.

Teen Vogue:

He accused you of being pro-Obama by virtue of being anti-Trump; why do you think that people make that assumption?

Ash Sarkar:

I think that the reason why he made that connection is because he really knew that if [he] got pulled into talking about Trump's policy platform, it would be completely indefensible. So then he had to do a bit of sleight of hand and set up what he thought the only anti-Trump person could be, which was a pro-Obama one.

What we know is that lots of the people who have protested Trump in the U.S. — for example, all the people of Black Lives Matter — were leading protests when Obama was president, too. And what they've done is highlighted a lot of the consistency of the kind of problems and issues that they've identified with Trump's presidency. So I don't think that it is a simple category error or accident that someone has made that conflation. It's a deliberate attempt to discredit opposition to ruling-class interests. That's all it is.

Teen Vogue:

How does being a communist impact your view of the U.S. presidency, whether it's Obama or Trump?

Ash Sarkar:

If you've got politics which are left of social democracy, it implies that you've got an understanding that the economic platform used by Obama, which was [also] advocated by Clinton, did dispossess a great many Americans, and this isn't just the "white working class" everyone loves to talk about in relation to Trump.

Those who have suffered the most are working-class Americans of color. To me, having those politics means that you can look at economic problems without making it identity politics in the way that Trump has. Also, being a communist means being a fierce critic of the prison industrial complex and the military industrial complex. The expanded use of drone warfare and the expansive use of deportation under Obama. You can be a vocal critic of all those things, while also looking at how Trump [has done them] because, quite simply, he was able to build on a lot of Obama's legacy, particularly in terms of executive overreach. He's been able to pursue extreme, draconian forms of state violence.

I also think that Obama represented a possibility of change, of weakened forces of racism in America — pretty meaningful. I'm not going to be someone who's going to discredit his legacy entirely.

(Continue Reading)

#politics#the left#teen vogue#ash sakar#communism#progressive#progressive movement#socialism#uk politics

198 notes

·

View notes

Text

Star Wars Episode VIII: The Last Jedi (2017)

Call me a Star Wars nerd: my childhood was literally me speeding to the library every week to borrow the Jedi Apprentice novels, before I graduated to the Expanded Universe (now called Legends) of the Thrawn Trilogy and the New Jedi Order, to name a few. Not just novels, but comics too! Unsurprisingly, games that have a special place in my heart include both Knights of the Old Republic games (not The Old Republic MMORPG) and years on, I still write fic about that era and get emotional over a 13 year old game.

But I couldn't love The Last Jedi (TLJ) no matter how hard I tried. Sure, there's space battles and blowing-things-up that's iconically Star Wars, but one thing (amongst others) ruined it for me. Despite the franchise crowing “diversity” and being “progressive”, TLJ falls back on tropes that should belong in the Stone Age. If I listed everything skeevy about TLJ like the lore and plot inconsistencies, I’d be writing a thesis, so here’s four points to consider. Spoilers abound.

1) For Some Reason, The Narrative Now Centers On Kylo.

This was my absolute biggest issue with TLJ. Here, we see Kylo being woobified and treated like a boy in the narrative despite him being a grown-ass 29 year old adult. In numerous instances, Kylo’s Tragic Backstory™ is emphasised: being neglected by his parents, his Uncle Luke wanting to murder him, Snoke grooming him to join the Dark Side, him struggling with his insecurities ft. his explosive tantrums - all of which subtly nudging us to empathise with him. Aka, highlight that despite him being involved in the Star Wars equivalent of a militaristic fascist organisation carrying out genocide and literal slavery AND being the one responsible for murdering Jedi students at Luke’s Jedi Academy, we must feel sorry for him. That he just needs to be understood. So he can be redeemed.

Seriously. If Luke “There Is Still Good In [Vader]” Skywalker thinks Kylo is irredeemable, I’m tempted to believe him.

But back to my point. Kylo’s story is suddenly the crux in TLJ moreso because other characters have been mangled - character-wise - simply to prop him up. Most damning is how Rey, of all people, suddenly decides that Kylo is worth saving despite him murdering the first father figure she had and ever wanted (Han), mortally wounding the first person who saw her worth coming back for (Finn), and mind-raping her in their first interaction in a torture room - in the span of, what, two weeks? Fine, perhaps this is Rey being flawed - tying in to how we shouldn’t hold representations to perfect standards, especially for marginalised identities. But really? Even with all such instances imply? Because to me, this simply reinforces that stereotype where a “Virtuous But Naive (White) Woman Saves Angsty (White) Boi From Himself”; a norm that reflects real-world instances of women doing tons of unpaid emotional labour while absolving men of the responsibility to improve themselves or even take responsibility for their own actions. So yes, it’s misogynistic. In TLJ, Rey exists solely to redeem Kylo. And that doesn’t sound like the Rey from The Force Awakens (TFA): you know, the Rey with an arc not revolving around a man? (I don’t want to discuss the implications of the Reylo pairing and what it normalises - there’s too much, and this isn’t the place). In that, Rey stops being angry; an essential character trait she displays when faced with danger and the unknown, because women can’t be angry, right? Otherwise, “they’re dangerous”. Hence, Rey’s character is watered-down for Kylo’s benefit.

As if mischaracterising Rey wasn’t enough, they had to brutalise Luke’s character too. Luke Skywalker, the compassionate pacifist who believed that even the vilest of individuals could be redeemed, suddenly decides that the best way to deal at all with Kylo is to kill him? Seriously????? (It’s not just canon that disputes this characterisation of Luke - even the Legends books dispute this. And Luke changing his mind last minute doesn’t count). Sure, the bitter, jaded, and depressed Luke we see in TLJ is believable, given recent events and him self-flagellating over such events - but his decisions prior? Inconsistent. Or, just to fuel Kylo’s Tragic Backstory™ (which wasn’t even elaborated much. How did he fall? How was Snoke responsible? Where did Snoke come from? Just marvel at the wealth of lore that could’ve been explored). In the process, the Luke who used love and forgiveness instead of violence (i.e. toxic masculinity) to be a compelling hero, was sacrificed.

But hey, all’s fair in propping up white male characters and their manpain, right?

2) Fake (White) Feminism

What riles me up more is hypocrisy. Because once you peel off TLJ’s supposed “progressivism”, you realise that diversity is actually horrible representation built on racism galore. So feminism here is just performative.

Generally, Vice-Admiral Holdo’s scene with Poe is seen as a case of a Strong Woman™ shutting down Mansplaining directed at her, where Poe is supposed to learn how to trust his superiors and become more “level-headed”. (Star Wars advocating for “blindly trusting authority”? Gosh. Wonder what the Rebellion was doing in the Original Trilogy then). Plot hole aside, it works, if you can ignore how Poe is mischaracterised using racist tropes of the irrational, hotheaded, misogynistic Latino; which, incidentally, is not the Poe depicted in the comics and TFA. (Same thing with the Leia scene at TLJ’s beginning - TFA Poe wouldn’t blatantly ignore orders and kill off most of his squadron just to destroy a capital ship; TFA Poe would be deathly afraid of sending his squadron to their deaths.) On the other hand, if we consider how Poe wasn’t mischaracterised, then this scene is a case of how people of colour tend not to believe white women in positions of authority due to a history of racism, or how Poe wouldn’t easily trust someone he was unfamiliar with. So, what’s going on here? Simple - A male character of colour is demonised just to prop up a white woman. “Feminism”, y’all.

Okay, you might think: as his commanding officer, Holdo’s not obligated to tell Poe anything. But if Poe manages to mutiny with a number of Resistance personnel, then perhaps this is a case of Holdo not leading effectively? Hm? Anyway, miscommunication without sufficient buildup as a plot device is contrived and does a disservice to the characters involved. It’s not representation when it’s done at the expense of someone else, especially another marginalised identity. (Holdo deserved so much better).

Also, you’ll notice how most - if not all - of the leading ladies in TLJ are white. Pretty intersectional film, don’t you think? This is compounded by how TLJ barely passes the most basic of feminist tests - like Bechdel and Mako Mori - despite the quantity of non-white male characters and calefare abound. Ladies only ever talk about male characters, save that brief conversation between Leia and Holdo when they weren’t being condescending about Poe, and unfortunately exist just to further another male character’s arc (Rose, Rey, Holdo, Phasma…).

Plus, notice how Luke’s Caretaker aliens on Ahch-To are femme-coded...a la cis-heteronormative gender roles, thus assuming that aliens conform to a gender binary, or even have genders. I’m not lying - it was intended. How...colonial.

3) Just. Racist. Bullshit.

As mentioned, TLJ’s progressivism masks a deluge of racism. Though I’m neither Latinx nor Black, watching certain TLJ scenes left me thoroughly uncomfortable.

Did Hux and Leia really need to slap Finn and Poe respectively? Did TLJ really need to make their male characters of colour (MoC) comic relief and recipients of violence - with Leia stunning and slapping Poe, Rose tazing Finn, Phasma/Hux wanting to behead Rose and Finn (with Phasma and Hux being literal space nazis)? All of that despite Poe and Finn having recently recovered from either torture or mortal injuries? And Finn himself dealing with the trauma of being a First Order stormtrooper, emotional abuse being one such after-effect? Clearly, the pain of non-white characters is acceptable fodder for jokes, but not that of white characters - Kylo’s scenes certainly weren’t. Some of them actually had plot. Interesting contrast.

Furthermore, did TLJ have to sideline their PoC characters, least of all their MoC leads? As mentioned, Poe was mischaracterised to prop up a white woman and Finn used as comedic relief and generally denied narrative attention despite being a lead...because Kylo apparently deserved more screen time. Yeah, Finn went with Rose to Canto Bight to find Maz’s master codebreaker, which, if I’m not wrong, are called slicers. Personally, I liked the subplot - it’s a nice allegory to reality, where the military industrial complex, capitalism, and the rich go hand in hand in slowly destroying the world, aside the message of how rebelling isn’t just about fighting baddies, but fighting for people. Like inspiring the “little people”; civilians and those uninvolved in the fighting. And in the process, exploring how war affects them. (One thing though: freeing/focusing on the Fathiers instead of the child slaves on Canto Bight?)

Then you realise that apparently, Rose Tico was created not because they needed a Rose Tico in TLJ - rather, having Finn and Poe pull a buddy-cop act on Canto Bight didn’t have the conflict that introducing a female character would. Sigh. Rose Tico, plot device. Just like Paige Tico - her death, albeit heroic, used to drive Rose into Finn’s path. Therein lies the anti-Blackness and anti-Asian aspects of the Canto Bight arc. Arguably, through their detour, Finn learns who exactly the Resistance fights for and moves past his “selfishness” of looking out only for himself and Rey - thanks to Rose’s guidance throughout their trip, which, as TLJ panned out, was eventually unnecessary and contributed little to the overall plot of “Will Kylo Finally Forsake The Dark Side?”. It’s Rose’s educating of Finn that simultaneously makes her a racist portrayal and a plot device as a Wise Asian Walking Encyclopedia to help teach a Naive Black Character about the Grim Realities of Life that Finn survived and escaped from - was he not a former stormtrooper captured by the First Order when he was a child? Perhaps Finn wasn’t adequately socialised to civilian life, thus his wide-eyed reaction to Canto’s glitz, but why wouldn’t Finn, who grew up in a traumatic and manipulative environment and recognised it for what it is, not see through Canto’s facade? Plus, Finn’s supposed development isn’t about himself; it’s about making him prioritise the needs of others over himself as if he hasn’t been doing that an entire movie ago.

Don’t know ‘bout you, but that sounds like bad writing. Bad, racist writing.

4) Centrist Reasoning

Finally! One last section to discuss. Hope everyone’s still here.

In keeping with the times, one of TLJ’s messages that stuck out was cynicism, moral ambiguity and that absolutes don’t exist. I agree, because life is never so clear-cut - but TLJ somehow simplistically portrays that. On Canto Bight, Rose tells us to “save what you love, not fight what you hate” (...despite saying she wanted to “put a fist through [the town]” just a while ago). When DJ mentions how weapons merchants sold to both the First Order and the Resistance, it’s said in a manner to somehow excuse them, or even give them a pat on the back; as if playing both sides somehow cancels the obvious self-interest driving their business decisions - but that’s assuming it’s a valid comparison in the first place. How is the Resistance, in any way, comparable to the First Order? Personally, this is just shoddy reasoning that conjures up nonexistent ambiguity. A reasoning that, when extrapolated to today’s socio-political climate, fails to clarify the power disparities between various groups in society by assuming a false equivalence. In other words, an erroneous comparison. Because however appealing it sounds, we can’t equate a fascist military organisation responsible for genocide and other inhumane practices with an organisation dedicated to thwarting it, for the sake of everyone.

You know what’s a better idea? Using Canto Bight or the First Order, through Finn’s past, to contrast between righteous anger versus mindlessly lashing out, often via violence (which, incidentally, adds nuance to the Light vs Dark Side of the Force debate). Because righteous anger, given its origins in a history of marginalisation and trauma, would be a way of ‘righting’ such wrongs despite the ‘wrongness’ associated with violence as a method. It’ll introduce moral complexity and gray-area dilemmas that TLJ craves without disregarding the sociopolitical implications of social movements and resistance. (Like, they could’ve explored the fact that the Resistance was essentially killing brainwashed First Order soldiers forced into fighting, but oh well).

So, four points to consider. But honestly? I'm only just scratching the surface. There's more nitpicking/meta online if you wish to delve. But honestly, TLJ could’ve been so much more. They had rich source material and endless ways to spin off the buildup that TFA created. And yet.

That’s why I’ll remain bitter about TLJ, and what it could’ve been.

tl;dr if you’re looking for a film that isn’t fake-deep on diversity, doesn’t contain senseless cynicism, or fulfills its narrative potential by avoiding copious plot holes and general bad writing, TLJ is not it. (psst, Rogue One did it better).

Further Reading

#tlj#star wars#media#articles#reviews#representation#colonialism#racism#misogyny#tw: rape mention#fake feminism

1 note

·

View note

Link

Who is Captain Marvel an allegory for? Is she a “Zionist Superhero,” as The Forward asks, emphasizing her final-act effort to find a home for a dispossessed people? Are the Skrulls a metaphor for the Jews, their ability to “sim” a metaphor for anti-semitic fears of Jewish assimilation (as the Times of Israel wonders)? Or maybe the Kree are Israel, publicly declaring the Palestinian Skrulls to be “terrorists,” always firing missiles at geography, and mounting commando raids against refugee camps (all to protect their borders from the families they call “infiltrators”)? Then again, perhaps the Kree Empire is the United States, or the EU: the Skrulls are misunderstood (and wrongfully maligned) refugees that — though portrayed by the empire as a threat to the body politic — turn out to be nothing more than families, so the Kree could as easily be Trump’s America (or Fortress Europe) as Nazi Germany. But since the movie also doubles as a commercial for the Air Force, it may also be that our heroine is simply The United States — as it sees itself — her superpowers being “The Superpower”’s use of military force to protect the weak from the predatory strong (which is why America has a military, right?).

And yet, despite some loosely organized chatter here and there, it’s been interesting to see how little discussion there’s actually been of the movie’s political subtext. Perhaps no one wants to touch it, or it’s gotten lost amidst other issues, like the misogynist boycott (and, secondarily, the movie’s obvious imbrication in the military industrial cultural complex). Maybe the MCU juggernaut has just gotten too exhaustingly vast to be interesting. And the parallels aren’t that exact: the Skrulls can’t be Zionists, per se, because they are not trying to return to their ancestral home (their planet was destroyed by the Kree); they aren’t persecuted Jews trying to make their way in an antisemitic world, because they literally only infiltrate, and only want to escape, not assimilate; and the Skrulls are not exactly the Palestinians, since — again — their home world was destroyed in retribution, not settled; what the Kree want is Skrull submission, not their land.

As for American allegories, well, if the Kree are comparable to the American empire in general respects — in that they are both empires — then the Skrulls are also comparable to refugees in that broadly general sense, and what we end up with are very general generalities. You can make this a Zionist movie or a pro-Palestinian movie if you cherry pick the points of comparison; you can make it pro-American or anti-American in the same way. What you can’t do is make this a pro-empire movie, or avoid the way it portrays refugees as the oppressed protagonists of history; if it’s Zionist, it’s because the Skrulls are refugees (like the Jewish diaspora) who need a home, and if it’s anti-Israel, it’s because the Zionist state denies a home to others (like Palestinians and African migrants). If it’s pro-American, it’s because you believed Donald Rumsfeld’s “we don’t do empire,” and if it’s anti-American, it’s because you know how full of shit he was.

In other words, the movie’s politics are actually constant; the variable is what reality we inhabit. Do you live in a world where the US is an empire and Israel is an oppressive, expansionist ethnostate? Or do you live in a world where the US is a helpful non-Empire that protects the weak (and Israel is a refuge for a people who have long been oppressed by empires, and now only survive with the aid of a super-power)? Reality — as mediated by very different ideological lenses — can provide you with either backdrop for this movie’s politics.

¤

Who is Carol Danvers? For me, the basic problem with Captain Marvel is that its protagonist doesn’t have a real arc, that her superpowers drain away her character. She ably inhabits a reflexive set of knee-jerk postures — she is cocky and confident as a Kree super soldier, briefly hesitant and reflective as she learns she isn’t a Kree super soldier, and then, finally, she becomes cocky and confident again as a kind of super-powered rogue Air Force pilot. But how satisfying is this arc? I think the movie itself is too easily satisfied with “fighter pilot” as a personality and with a photo album of cliches and a falling-down-and-getting-up montage (while doing “boy” things) as a substitute for backstory. The amnesia plot could have been more interesting; in The Long Kiss Good Night or The Bourne Identity, obvious points of reference, amnesia is a device to alienate a person from themselves, to place the person she was and the person she has become into conflict. But Vers’s recovered past only confirms who she is, only negates her six years as a faux-Kree. And so, instead of of working out the dilemma of a past the character no longer wants, the memory she has lost could be summed up in an Air Force recruiting commercial — apparently has been — and she simply returns to being the person she had been before; her conflict is external, but because she is endowed with so much power, she solves it with ease.

She was a soldier before; then she became a soldier; now she is, again, a soldier.

Whether this is a problem depends on what you want from Captain Marvel. In one sense, the story of how a Kree super-soldier learns that she is really a human being and that the Kree are, to quote Mitchell and Webb, the baddies, is basic MCU stuff. As she she comes to realize that she and Jude Law are the baddies, the movie becomes the story of how she learns to be the good kind of super-soldier — the US Air Force kind, instead of the Nazi kind — and how she unlocks her powers to save refugee families instead of killing them all; in this sense, it is an MCU story, which are so often plots about how a super-soldier realizes that there is something off about American Empire and has to fight to purify it, reform it, or save it (and does). Thor’s Asgard is a little like this — with two different movies just about learning Asgard’s original sins — but the best examples are Captain America signing up to punch Nazis and discovering, in Winter Soldier, that S.H.I.E.L.D. has been infiltrated by Hydra, and Iron Man building weapons for the government only to realize that war begets war begets war. If this is what you want from Captain Marvel — if what you want is an MCU story — then this is what you’ll get: she learns that being human sometimes means breaking the rules, and when threatened by the army that claims to have made her — that will take away her powers and leave her “only human” — it turns out that she has even more power, alone.

In the MCU, the answer is always to privatize your power and do it yourself, and this, in Captain Marvel, is also the answer. In MCU movies, the good guys always turn out to be the baddies because there are two different realities which define American politics: in one, the US are the good guys, punching Nazis and protecting democracy and human rights, the world’s policeman that keeps the peace; in the other, we are the settler state whose reservations were a model for Hitler’s genocide, a cop who spends his day being ready to shoot non-white people and evicting the homeless.

In Captain Marvel, then, the Kree become a scapegoat, an oppressive empire that oppresses the oppressed. And while the Air Force could easily be shown to be the same kind of genocidal imperial force as the Kree, they are not; when we see Carol Danvers longing to be a fighter pilot, it’s the first Gulf War that she would have — had not events interceded — wanted to take part in, the good gulf war where bombing Iraqi cities only resulted in hundreds of thousands of dead civilians and only set the stage for the decades of suffering that have followed. If the long gulf war against Iraq isn’t considered a holocaust, after all — three decades of warfare that began, in 1991, when those bombing campaigns that Carol Danvers longed to take part in produced “near apocalyptic” conditions — it’s because Iraqi lives and deaths have never been part of the reality where the US Air Force is good.

The Kree give us an excuse to stay in that reality. Carol Danvers doesn’t become a US Air Force pilot, and doesn’t fire missiles at populations of civilians; instead, we see the Kree do those things, at the beginning and end of this movie, absorbing all of villainy that might otherwise have accrued to the movie’s other imperial slaughter machine. Carol misses the first gulf war and avoids being indoctrinated into an Islamophobic slaughter-machine because instead of being the soldier she had wanted to be, she gets kidnapped and brainwashed and enlisted into the Kree army, against her will; after the reptilian shapeshifters turn out to be families, she has an occasion to save them, flying away from Earth and the United States and never has to choose whether to take part in our never-ending forever war against Iraq and the Middle East. Because it’s the Kree Starforce she repudiates, she never has to take a position on whether the US Air Force are the baddies or not.

The space where she would have had to make a choice — were it not for those interceding events — is the space where her character’s internal conflict and growth might otherwise have been. But because this movie cannot allow us to ask or answer whether the Kree are the Nazis or whether the Skrulls are the Palestinians — can gesture towards empire being good and refugees being bad — it can’t quite allow her to have a character arc defined by that internal conflict; she remains a collection of Top Gun clichés, updated for the era when women can play those roles too, but essentially consistent in its vision of cowboy pilots fighting for the good.

What we’re left with is an “origin story.” Even the Air Force commercial before the movie — “What Will Your Origin Story Be?” — knows that what we’re really doing here is establishing the prequel to the character who will, in Avengers: Endgame, show up to save the day. But this is why this movie isn’t really about Carol Danvers, why the first female-driven MCU movie doesn’t get anything like the space and time to build a growth arc to match all the boys. Iron Man and Thor had multiple movies before the characters started to really achieve depth and complexity — which only totally pays off in the Avengers movies — while the first two Guardians of the Galaxy and Captain America movies are essentially two-parters. Captain Marvel gets one movie; unlike Captain America, she doesn’t get multiple movies to learn how not to be the soldier she had always wanted to be, and unlike Thor, she doesn’t get four films to learn how to earn the inheritance she was given. Each of the boys struggles with the inadequacy of what they initially wanted, and learn to want more, but Captain Marvel is mainly a movie about the origins of S.H.I.E.L.D., filling in random details that no one really needed to have filled in — like the origin of Nick Fury’s eye patch — and answering one big character question: how did Nick Fury come to decide that Earth needed help against aliens? What made one person — and only one person — decide that a super-secret organization was needed to develop a super-powered human to defend against an armada of alien spaceships that attack, out of nowhere, for no reason? This movie explains why Nick Fury did all that, by showing him experiencing it for the first time. These questions it answers, repeating the events of The Avengers (2012) by placing that repetition in the past. But the story of Carol Danvers gets left on the cutting floor, source text for an empowerment montage, not otherwise shown.

As a result, the movie poses questions it can’t answer. When we see her show up in the present — played by the same actor who is the same age — do we ask what Captain Marvel has been doing for the last twenty-four years? What she has done and learned? How she has grown and changed? If she approves of Nick Fury’s “Avengers Initiative,” and of S.H.I.E.L.D.? Did she watch Captain America: The Winter Soldier where an American super-soldier with the name “Captain” discovered that the good guys had been secretly infiltrated by the bad guys since the beginning? There are obvious and inescapable political allegories here, but what is her position on the two-state solution, the right of return, and does she have any thoughts on Ilhan Omar? Who, precisely, are the Skrulls and the Kree meant to be?

If these are ridiculous questions, it’s because this is a Marvel movie, whose episodes always gesture at resolutions that the big team-up movies will cannibalize. Thor: Ragnarak ended with the population of Asgard become a rootless diaspora searching for a new home — an extremely resonant image — but when Avengers: Infinity War began, five minutes later, Thanos had already killed half of them, offscreen, and the MCU seemed to have completely lost interest in that story, as comprehensively as it does when Black Panther’s triumphantly concluding Afrocentrism becomes Infinity War’s “sure, we’ll sacrifice Wakanda, why not.” The ending of Captain Marvel gives us the same feeling of closure — she has stopped being a soldier who kills civilians and become the kind of soldier who saves them — but the MCU’s narrative engine will never sustain this transition; the real amnesia of this franchise is how single-character episodes discover things about their protagonists that have to be forgotten.

In a month, Carol Danvers will show up on earth again, to help the Avengers fight Thanos; as the post-credits scene indicates, she will not have aged in the interim, a nicely symbolic figure for her general character stasis. Growth is not what she’s for. She is, as a throwaway line in the movie briefly acknowledges, a weapon.

¤

And yet, there is one thing that does seem worth saying, that this movie does clearly says: the thing Carol Danvers learns from Nick Fury is that “being human” means disobeying orders and following your conscience, specifically, in this case, disobeying the orders given by the army and command structure that claims to have made you who you are, to have given you your powers, and to have been your origin story. This is too implicit to be in open rebellion with the Air Force commercial, but it’s there: that isn’t, the movie whispers, your origin story. And so, when Jude Law tells her that without what the Kree have given her, she’d be “only human,” this is the point: to be human is to be without what they have given her. To be human is to quit the military, we might conclude; to be human is to know — and not to have to ask whose side you’re on — when you see a flesh-and-blood human being attacked by her natural enemy, the military.

After all, what makes Carol Danvers who she is, what makes her human? It’s not the Air Force, or if it is, it’s not the part of the montage where the men jeer and laugh; it’s the part of the Air Force where she and Maria Rambeau are kept out of the Air Force, and the sisterhood they form from that experience. It’s her re-connection with her friend, through two stunning monologues — about loss and pain and love — delivered by the character who grounds her as a character (and without which she wouldn’t be one).

What do we want from this movie? Carol and Maria are never going to be given an explicit love story, any more than Marvel Studios could do without the money the US Armed Forces gives them to make these movies; Captain Marvel is not explicitly queer and Captain Marvel is, explicitly, extremely pro-Military. But that’s how movies work; the good stuff lives in the little moments, the gestures, and the things that aren’t explicit enough to be nailed down. And there’s one detail that does seem important to me: Carol Danvers never gets the chance to, but it seems clear that Maria Rambeau quit the Air Force, a long time ago.

The post Who’s the Baddie? Captain Marvel in the Age of American Empire appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2OhpbwK

via IFTTT

0 notes